In April 1913, the management of the Austrian Berg- und Hüttenwerksgesellschaft settled in Vienna applied for tax exemptions on five workers’ houses in Mariánské Hory (Marienberg)—an industrial village in Northern Moravia near Ostrava—the fastest growing city of the Habsburg Monarchy. In each of the newly built houses, there were eight apartments. The apartments were 35.6 m2 large and consisted of one room and a kitchen. Apartments were rented to company's employees. In structural, health and moral respects, the houses met the conditions laid down by the act on concessions for buildings containing healthy and affordable workers’ flats (the Concessions Act). However, authorities exempted houses only under certain conditions.Footnote 2

The provincial governate (Statthalterei)—the political body representing the imperial government in MoraviaFootnote 3 and the Land Financial Directorate in the Moravian capital Brno (Brünn), which was in charge of financial and tax issues—called on the company to adjust the corridors on the first floor according to the regulations. In addition, a laundry room was to be set up where residents could do laundry. The common central laundry for all houses had not proven its worth and workers had to wash their clothes in the house courtyard. Eventually, a drain for slurry waste from the barns for domestic animals that belonged to the houses was to be built. Authorities also feared overcrowding, which was connected with a lack of morality, health, and hygiene. They ordered that the house rules were to guarantee that a maximum of seven persons could live in one apartment. To prevent the entry of strangers, the main door to the building was to be equipped with a lock. After they met the conditions, the ministry of finance and the ministry of public works confirmed tax exemptions to the houses for twenty-four years.Footnote 4

The workers’ houses in Mariánské Hory were exempted in line with the application of the act on concessions for buildings containing healthy and affordable workers’ flats. The Concessions Act was passed by the imperial parliament (Reichsrat) in July 1902, after several decades of ongoing discussions about housing issues.Footnote 5 The Concessions Act had a total of twenty-six sections that covered various aspects of the tax exemption. There were sections that dealt with workers’ family houses and defined who could be considered a worker. Other sections allowed exemptions for welfare amenities (kindergartens, reading rooms, washrooms, laundries) that were part of the residential buildings. Sections also established that buildings should ensure “personal security, health, and morality.” Moreover, they dealt with the calculation of rent, rent ceilings, and landlord-tenant relations. They prescribed official procedures for granting and denying tax exemptions and confirmed the validity of earlier exemption provisions.Footnote 6

According to statistics, 4,165 applications for tax exemptions were filed in Cisleithania—in the western part of the Habsburg Monarchy—between 1902 and 1913, of which 2,237 were approved (i.e., the Berg- und Hüttenwerksgesellschaft's application). The application success rate was thus 53.7 percent. Due to the initially high number of rejected applications, after 1908, the authorities adopted a “liberal” approach to the law. The more benevolent approach thus allowed tax exemptions to be granted for more buildings.

The greatest number of exemptions were granted in the Bohemian lands, which accounted for 75.5 percent of the total. Subjects based in the monarchy's other crown lands often applied for tax exemptions in Bohemia, Moravia, or Silesia (i.e., the Berg- und Hüttenwerkgesellschaft). Tax-exempt buildings provided accommodation for a total of 101,476 people. Industrial enterprises and firms benefited the most from this law. They owned 86.5 percent of tax-exempt buildings, which housed 81,472 workers and their family members.Footnote 7 By means of the Concessions Act the state and private sectors were involved in the construction of workers’ housing.

The involvement of private enterprises and at the same time state authorities in the construction of workers’ housing is the starting point of this study. The study asks, what role did state and public authorities play in welfare capitalism in general and housing policy in particular? Were they merely a catalyst, as the classical definitions suggest that welfare capitalism emerged when authorities began to intervene in labor and social issues? How did state and public authorities regulate everyday places and separate spaces for people of workers’ background, male and female workers, single workers, and workers’ families? Did they enforce the appropriate lifestyle and the demanded improvements of moral, social, and health standards?

Welfare capitalism refers to a complex of social, housing, health, safety, and leisure policies and facilities that were connected to the workplace and established by the private companies. In contrast to individual policies, welfare capitalism is considered to be a system-forming phenomenon.Footnote 8 It points to a socioeconomic order that existed at a certain place and time. Welfare capitalism emerged along with the boom of industrial enterprises, the construction of factories, and an influx of labor forces. It could be a corporate strategy for heading off the demands of organized working-class movements. Through it, entrepreneurs sought to eliminate strike actions, subdue the power of trade unions, ensure social reconciliation, and effectively manage the working population. Welfare capitalism is also interpreted as an attempt to assume the responsibility for workers’ well-being before the welfare state massively took over these obligations.Footnote 9

Map 1.

The rise of economic liberalism and industrial capitalism in the Habsburg Monarchy in the nineteenth century was accompanied by state efforts to moderate consequences that arose from the development of free-market relations in the world of work. Combining older domestic patterns and examples from other European countries, state and public authorities focused on worker protection in industrial enterprises. They started to supervise the working, health, and hygienic conditions and to regulate working hours and to deal with the social security of the workforce.Footnote 10 In the 1880s, the conservative government initiated major welfare policies.Footnote 11 It adjusted poverty relief that was based on legal residence status.Footnote 12 State and public authorities advocated for the protection of children, adolescents, and women working in factories. Following the international conventions, a ban on women's night work in factories was approved.Footnote 13 Health and accident insurance for workers was introduced, even though the insurance substantially differed according to region, gender, and occupation.Footnote 14

Nevertheless, the mentioned policies were very particular and targeted at selected groups. They did not contain the principle of equality and did not include a number of characteristics usually associated with the welfare state, such as unemployment compensation, pension and disability insurance, free education, etc. Local municipalities could provide minimal welfare provision, but it was determined for persons with legal or long-term residence status. In many cases, social care was limited to the establishment of communal kitchens, workhouses, and labor exchanges. Its minimal nature and scope exacerbated permanent tensions.Footnote 15 Thus, the term “welfare states” should be used very carefully. A certain differentiation between welfare capitalism and the welfare state, vis-à-vis to the fact that both terms are sometimes understood as synonymous, could be fruitful for historical research.

The main archival sources of this study constitute reports produced by state and public authorities, especially by provincial governorates and the financial directorates. These reports served as background materials for ministerial decisions in Vienna. The Ministry of Finance consulted on tax exemptions with the ministry of the interior, and later the ministry of public works, which after being established in 1908 took over responsibility for workers’ housing. From the analytical point of view, these reports provide information on social and housing policy, to which previous historians have paid considerable attention. Whenever the ministry issued a decision to an industrial enterprise, it always included a brief justification. Nonetheless, officials still had to deal with many unclear cases. The study investigates such cases because not only can they tell us much about ministerial policies, but they also reveal a great deal about the places of workers’ daily lives.Footnote 16

First, the study introduces the history of welfare capitalism and housing policy in the West and in the Habsburg Monarchy. It combines a chronological and thematic approach. Second, the study tries to integrate the housing policy of the Vienna government into the general story of welfare capitalism. Arguments that emerged in the context of welfare capitalism are completed with empirical examples from the Bohemian lands. Most studies researched welfare capitalism from the perspective of entrepreneurs, businessmen, managers, intellectuals, workers.Footnote 17 They did not pay enough attention to the view of state and public authorities on this phenomenon. Much attention has been devoted to this phenomenon in the Western world, but it has been studied much less in the Habsburg Monarchy and in the Bohemian lands. By examining how the Act of 1902 was applied, the study explores the tax exemptions for company housing that state, provincial, and regional authorities pursued.

Welfare Capitalism and Housing Policy in the West and in the Habsburg Monarchy

It is impossible to determine when exactly welfare capitalism originated. At least in the construction of workers’ housing, there was a strong continuity between the pre-industrial and industrial periods. But already in ancient times, the owners of large craft workshops or agricultural yards had to deal with the accommodation of many people. While in China, India, or Persia there were large enterprises with many workers during the Middle Ages, in Europe and America they also reappear in the early modern period.Footnote 18

In the first half of the eighteenth century, large new workshops and factories were established in the countryside, where their operators tried to escape guild regulation. Very often, a high number of workers gathered around them, for whom it was necessary to provide accommodation. The mining authorities established the first “mining colonies,” in which miners received houses and flats under certain conditions.Footnote 19 Later, “industrial villages” and “company towns” offered a dense concentration of infrastructure for workers and housing. Industrialists defined a space that was controlled by them. They provided employees not only with accommodation, but also with other social and cultural facilities.Footnote 20

From the beginning, housing was associated with moral, social, and utopian meaning. In the earlier period, the principle prevailed that the master provided shelter for his journeymen. The Enlightenment idea that human individuals are influenced by the environment in which they grow up and in which they behave during their lives inspired factory entrepreneurs as well as social reformists.Footnote 21 The construction of workers’ housing was also initiated by the religious and social beliefs of entrepreneurs who sought to create model workers’ communities.Footnote 22

The demands of the Napoleonic Wars caused the Habsburg Empire to go bankrupt. State debt and military spending grew rapidly. The end of the continental blockade protecting domestic markets from the competition from British goods inflicted a heavy blow to industrial production. This caused new challenges to the governance, particularly with regard to public health and welfare. Fiscal limitations made it harder to realize generous economic and social policies. The Habsburgs’ fiscally strapped rulers tolerated activities that worked to solve expensive social issues. They even occasionally encouraged bureaucrats to initiate administrative practices in order to deal with local social problems. Dependence on access to loans to cover its recurring deficits meant that large banking houses influenced the government's budgetary priorities.Footnote 23

In 1820, the Vienna government was struggling to secure finances and introduced several new taxes. One was the building tax (Gebäudesteuer), which was levied as a rental tax (Zinssteuer) or as class tax (Klassensteuer) based on housing type. The rental tax was paid by the property owner and was applied to all properties situated in districts where at least half of the residential units were rented. The tax was paid on net rental income. Buildings not subject to rental tax, that is mainly private houses in smaller towns and villages, were subject to the so-called class tax. There were sixteen tax classes, which were based on the number of rooms the house had. It was a flat tax; the more rooms a house had, the higher the tax was.Footnote 24

A circular focused on taxation outlined many exemptions, which could be granted under certain conditions. The exact nature of these conditions, though, was vague, and those applying for them could never be sure whether they were in compliance or not. Not only churches, barracks, hospitals, poorhouses, and other community buildings, but also structures containing apartments for teachers and officials were exempt from the tax. Over the next decades, the building tax was modified, and the competences of the authorities in charge of granting tax exemptions were clarified. Very soon, the tax exemptions also included the construction of housing for a wider swathe of population. Footnote 25

By the middle of and into the second half of the nineteenth century, the Habsburg Monarchy societally and economically boomed. New highway projects, canals, river regulation, and mountain pass systems expanded transport and quickened communications across the empire. Towns and cities exploded. Increasing numbers of people left their place of origin and moved to other parts. Inhabitants of the rural countryside flocked to industrial centers to find employment in business, trade, and manufacturing. Entrepreneurs, bankers, and industrialists founded and built model welfare amenities and company housing. The old gabled rooftops were replaced by full-scale second stories. The interiors of the houses received more attractive and comfortable furnishings. Workers and peasants actively sought and gained a degree of social and geographic mobility. They influenced the authorities in changing the function, responsibility, and meaning of the state from schooling to military service to welfare benefits.Footnote 26

The state and public authorities took a much more active role than before 1848, in dealing with the social problems of an increasingly urbanized, industrial society.Footnote 27 They began to support the construction of workers’ housing. For example, in 1849, they established housing for several mining families in an industrial building during the construction of pits in the North Moravian villages around Ostrava. A decree of the ministry of finance was the further important act, as in August 1852, it approved the construction of a mining house near pit No. 10 (later Jindřich), where the miners moved in.Footnote 28 In 1878, two one-story houses with sixteen apartments in the Westend colony in Ostrava were exempt from the class and house taxes.Footnote 29

As in Britain, France, and Germany, social reformists and liberal politicians in the Habsburg Monarchy also initiated proposals for housing tax benefits for low-income populations.Footnote 30 In March 1880, the act concerning the tax exemption for the conversion, extension, and construction of various buildings was passed. Old buildings that were rebuilt and extended or newly constructed buildings could be exempted from rental and class taxes for a period of twelve years. Although the purpose of tax exemptions was to improve housing conditions and to support the construction of new flats for the low-income sector, the construction entrepreneurs and the owners of the buildings benefitted the most from this act.Footnote 31

Two years later, in February 1882, the Reichsrat passed another act, unifying the still-fragmented rules for the collection of building taxes in Cisleithania (the Western part of the Habsburg Monarchy, see Map 1).Footnote 32 Exemptions from these taxes, however, could be granted under certain conditions. The exact nature of these conditions, though, was vague, and those applying for them could never be sure whether they were in compliance or not. In November 1883, the director of the norther Moravian Vítkovice Ironworks, Paul Kupelwieser, applied to the ministry of finance and the ministry of the interior for a tax waiver for company apartments that featured high sanitary standards. The ministry of finance rejected the application as unfounded.Footnote 33

In the following years, several bills were introduced in the Reichsrat to establish tax incentives that would spur the construction of workers’ housing. In 1883, the Reichsrat's deputies submitted a bill that would make dwellings for low-income people, especially workers, tax exempt.Footnote 34 However, this proposal was never discussed in the plenum. In 1885, the deputies made another attempt to pass a modified version of the same law, but again there were no visible results.Footnote 35 Success would only come seven years later, when in February 1892, the act exempting buildings containing workers’ flats from rental tax was adopted.Footnote 36 Workers’ housing was also exempted from all state and district surcharges on the above-mentioned state taxes and municipal surcharges were also reduced.Footnote 37

From February 1892, the Habsburg Monarchy followed the example set by Britain and Belgium, where similar laws were already in force. In particular, the law established a low rent ceiling that did not reflect market prices or construction costs.Footnote 38 Contemporary commentators pointed out that the act set strict conditions for tax exemptions and noted that most potential candidates had no chance of gaining one.Footnote 39 By the end of 1897, taxes had been waived for only 174 buildings in the whole monarchy. From this number, 88 houses with 607 flats were built by private entrepreneurs. During the ten-year period that this law was in effect, a total of 400 buildings in the monarchy were granted exemptions.Footnote 40

The ambiguities of this law, which caused problems for both authorities and industrialists alike, are illustrated by repeated attempts to gain a tax exemption for four company buildings erected in the North Bohemian village of Loučná (Lautschnei) in 1900. Pursuant to the act from February 1892, these buildings should have been tax exempt. However, because they were not used in accordance with the law, in November 1904 the district captaincy (Bezirkshauptmanschaft)—the district political body—abolished their tax-exempt status. The ministry's rejection letter later stated that the rent consistently exceeded the maximum amount allowed by regulations. One of the apartments ceased to be occupied by the original tenant of worker origin and was subsequently transferred to a third party who paid more than the maximum rent established in the law. The ministry also informed the company that it was impossible to exempt houses simultaneously from both rental tax and class tax, as had been requested.Footnote 41

Welfare Capitalism in the Bohemian Lands: Concessions Act No. 144/1902 and Its Impact

Despite imperial regulations, including amendments to construction laws and tax incentives intended to mitigate the housing shortage, the situation improved only slightly. In July 1902, the mentioned act on concessions for buildings containing healthy and affordable workers’ flats was passed. Unlike the preceding law from 1892, the new act was more comprehensive and precise. The act further extended existing tax exemptions for workers’ dwellings. In addition, buildings were exempted from taxes and related surcharges for twenty-four years. The act did not enter into force until it was approved by the provincial assemblies: in 1903, in Lower and Upper Austria, Styria, Vorarlberg, Silesia, and Galicia; in 1904, in Tyrol and Moravia; in 1906, in Carniola and Bohemia; and finally, in 1910 in Dalmatia.Footnote 42

In the company housing, historians distinguished two basic types. First, the barracks type, which prevailed in German industrial centers, and was characterized by large buildings with many apartments. The second type—the cottage, which was common mostly in the British Isles, included a small detached house with a garden. In the Bohemian lands, the so-called mixed (“Mulhouse” after the Elsassian town) type, which combined the characteristics of barracks and cottages, became more common. At least for workers of rural origin, the mixed type had a sociopsychological advantage: it created the appearance of a detached house with its own backyard, garden, and sheds.Footnote 43

In the Ostrava region, a mixed type was based on four-apartment houses. Their construction, operation and subsequent rental were more economically advantageous than the classic cottage type. Workers’ houses of the mixed type were also economically advantageous thanks to tax exemptions. In May 1914, the ministry of finance granted a tax exemption for thirteen buildings that had been built in Petřvald (Peterswald). Although the barns for small domestic animals that were part of these buildings were not erected in accordance with the regulations in force, the ministry made an exception under a related section of the Concessions Act with regard to “the free location of the colony.”Footnote 44

The company housing was originally not differentiated by workers’ social and professional backgrounds. Industrialists often lived in or around the factory with their colleagues and communicated with workers face to face. White-collar and blue-collar workers could live under one roof in the same buildings. But with the rise of large enterprises, these patriarchal relationships changed. The labor division had deepened, social distinctions increased, and the distance between different professions had widened. New lifestyles and housing standards emerged. Managers’ and masters’ apartments were larger and better equipped than workers’ flats.Footnote 45

Map 2.

As in Western industrial centers, entrepreneurs in Moravian and Silesian towns also built housing for different categories of employees. Houses and multibedroom apartments were reserved for executives and company officials. Senior married officials with tenure were entitled to a service apartment, lighting costs, and heating.Footnote 46 For example, in December 1907, a mining company requested tax-exempt status for the house with five flats it built in the North Bohemian village of Ohníč (Wohontch). The company manager Oskar Sládek and the mining inspector Feuereisen lived with their families in the house. The Sládeks’ annual income was 4,476 crowns, while the Feuerreisens’ income was 11,904 crowns a year. The ministry of finance turned down the request. Tenants of the house did not legally classify as workers because they were not “low-income people who carried out production activities manually.”Footnote 47

Large businesses rented houses to workers at widely varying rates. In view of the tax exemptions favored by the state authorities for the construction of workers’ buildings, the rent could have been symbolic. Workers with large families or those who reached retirement age were preferred. In this way, companies appreciated the loyalty of their employees.Footnote 48 Small firms also constructed houses for retired workers. Pursuant to the Concession Act, tax-exempt workers’ residences could also house nonactive workers as long as three-quarters of the inhabitants were workers. However, the income of these nonactive persons could not exceed the amount legally defined for workers. If they did make more money, officials could request their eviction.Footnote 49 An official's widow residing in worker's flat in the East Bohemian town of Náchod was probably such a case, because the ministry of public works warned her in May 1913 that if her annual pension rose above the permitted threshold (1,200 crowns a year), she would have to leave the house at the earliest opportunity.Footnote 50

According to the ministries, a worker was a person whose annual income, whether in the form of a fixed salary or an hourly wage, did not exceed a fixed amount. The annual income of a family with five or more members living in a tax-exempted workers’ flat could be a maximum of 2,400 crowns a year each. Ministries took into account the income of the entire household, wage levels in individual cities, temporary interruption of employment, or incapacity for work. There were doubts whether two company houses constructed in the small South-Moravian town of Koryčany (Korytschan) did meet the requirements of the law. An assistant accountant, Adolf Wutschek, who had a salary of 2,400 crowns a year lived in one house. A production supervisor, Ludwig Doležal, with the salary of 3,120 crowns a year lived in the other. Both paid a rent of 312 crowns a year. Neither of them met the legal definition of a worker.

Thus, the Financial Directorate in Brno, in agreement with the Governate of Moravia, rejected the company's application for the tax exemption of the houses in November 1911. Exceptionally, however, the ministry of finance, liberally interpreting the law, acknowledged the company's request for tax-exempt status. It took into account the fact that the assistant accountant's salary did not exceed the statutory limit. And, although the supervisor's salary was significantly higher than the law allowed, the ministry deemed his qualifications and activities to be close in nature to the “characteristics of the worker.”Footnote 51

The dividing line between low-level clerks and workers was a recurrent problem at the time. The Act of 1902 considered as workers persons employed in agricultural, trade, or otherwise profit-making enterprises, or working in public and private institutions for fixed or variable wages, whose annual income did not exceed a specified maximum. Thus, the legal definition of a worker was very general and “characteristics” of the worker were not clear. The authorities seem to have often decided, based on their own judgment, and determined themselves who was a worker. They could take into account education and type of work other than the above-mentioned income and form of payment. Some officials interpreted the law in a liberal manner. Others were stricter and understood workers only as persons who carry out production activities manually.

An important criterion according to which workers’ housing can be examined was the layout of the workers’ houses. These could be part of a workers’ colony or a workers’ “housing settlement.” Although historical sources often mention a single designation (“Arbeiterkolonie”), workers’ settlements differed from the colony itself. The colony consisted of great numbers of workers’ houses concentrated within the smallest space possible—just as many cottages as were necessary to pack together workers and their families. In operations involving draining, brick making, lime-burning, or railway construction, entrepreneurs provided their workers with improvised camps and wooden huts.

A settlement was much more complex: It included a dense concentration of infrastructure for workers and company housing. The settlement was systematically planned by a company in a certain area. It included houses for company agents, and nonprofit facilities such as schools, churches, parsonages, co-op stores, etc.Footnote 52 In the Bohemian lands, state authorities also granted tax exemptions for welfare amenities in the vicinity of workers’ settlements such as an administrative building of the workers’ settlement in the West Bohemian town of Pilsen. The building's ground floor contained eleven rooms that were used by the company's cooperative shop. In addition, there was a washroom, a guardhouse, and a newsagent.

When assessing the application for the tax exemption, the ministry of finance appreciated that the workers had the opportunity to buy groceries, including the tobacco products. While smoking became an indispensable workers’ habit, the sale of spirits was strictly prohibited in tax-exempt buildings as the ministry of finance confirmed several years later when it granted a tax exemption for a similar workers’ co-op in North Bohemia on the grounds that it would not sell spirits.Footnote 53

In West Bohemia, the ministry of finance intensively dealt with a three-room cooperative manager's apartment that was placed together with a workers’ reading room on the first floor of the building. The manager could not be classified as a worker as defined in the law, but the ministry stated that according to the rules, buildings with flats reserved for authorities that performed building management or supervision duties were in some situation granted exemptions. Moreover, the manager's annual salary was 1618.20 crowns and thus it did not reach the approved maximum. Therefore, the ministry approved the application. Footnote 54

The construction of workers’ housing could be connected to moral and social regeneration. Company settlements, houses, and flats were to create a peaceful home in which workers drew energy for the next working day. Leisure behavior allegedly affected work performance and through housing, companies tried to supervise staff. Some categories of dwellings had very small kitchens and rooms so that workers living in them would not waste time.Footnote 55 In the Habsburg Monarchy, authorities tried to prevent overcrowding, which was considered detrimental to workers’ health and rest. They focused on checking the size of flats, the dimensions of rooms, the maximum number of persons occupying buildings and flats, the presence of mandatory equipment in rooms, and so forth.

If flats were smaller than the standard, the authorities warned against hygiene problems. If the size of dwellings exceeded the norm, officials suspected that they housed more tenants or accommodated overnight (one-night) lodgers, random tenants, and pub buddies. Authorities set that a one-room flat must be between 16–25 m2; a two-room flat between 20–35 m2; and one with three or more rooms between 30–80 m2. In the application for a tax waiver, the maximum number of inhabitants of each apartment had to be explicitly stated, such as in the worker’ houses that a glassworks builT in the small North Bohemian village of Hostomice (Hostomitz) in January 1908.

Moreover, the glassworks had to build cesspools for four workers’ buildings. The floor had to be raised in one building because the ground floor was below ground level and therefore the flats were not sufficiently protected from mildew. Stoves were removed from the attic because they posed a fire risk, but in apartments on the first and second floors, stoves were built even in the smallest rooms because they were cold.Footnote 56

According to the ministries, houses without a sewer connection had to have cesspools. The base and the walls of the cesspools were to be made watertight. They were to be kept at least half a meter away from the masonry of the building. Ministries stipulated that the ground floor should be at least 1.6 meters above the groundwater level. Last, but not least, there must be a stove in living and bedrooms without central heating.

When regulating workers’ housing built by industrial enterprises thanks to the tax exemption, imperial authorities paid close attention to hygienic conditions such as ensuring low humidity and sufficient light, air, and heat in workers’ dwellings. The rooms had to have windows that were openable and directed into a free space. The total area of the windows should be one tenth of the floor area of the room. When establishing sanitary requirements, authorities considered the health risks prevalent in different industrial sectors. For example, in November 1912, the ministry of public works dealt with the dormitory in the East Bohemian village of Ruprechtice (Ruppersdorf) that belonged to a fireclay factory. Workers here were exposed to particularly harmful and dusty environments, but the dormitory lacked shower rooms. The ministry was willing to forgive this shortcoming only on the condition that adequate washing and changing rooms would be established in the factory.Footnote 57

In line with social morals, authorities warned against crowded, unsanitary, and unhealthy lodgings, which mixed people of different ages and sexes living together. These aspects were investigated in the case of the workers’ house of an engineering company in the small East Bohemian town of Hostinné (Arnau). The building contained eight apartments consisting of one small living room and a kitchenette. The design of these flats made it impossible to comply with the law's stipulation that children of the opposite sex over six years of age sleep in separate rooms. The ministry of public works granted an exemption in this case, recognizing that multiple families living in this building would otherwise have to leave their apartments and had no money to procure a multiroom apartment.Footnote 58

In the Western world, moral expectations were associated with housing: The provision of a house or apartment was to turn the “uprooted proletarians” into permanent employees, responsible fathers of families, good Christians, and conscious citizens.Footnote 59 In the Habsburg Monarchy, ministries did not always reach a consensus when it came to defining satisfactory moral conditions. In many cases, vague and conflicting definitions resulted in appeals and long-term procedures. Ministries discussed whether tax-exempt housing in which there were flats for working families and at the same time flats for single people could be exempted. Ministries diverged in their interpretations of the law.

Moreover, it was not possible to overlook societal differences, or the paternalistic approach to workers. For example, in December 1906, the ministry of finance issued a ruling on a six-flat residential building for security guards at the railways in the West Moravian town of Moravská Třebová (Mährisch-Trübau). The ministry of finance initially granted a twenty-four-year tax exemption. However, the ministry of the interior refused the exemption because it found that two one-room apartments were to be rented to single workers, arguing that this was unacceptable for a family building.

The ministry of finance disagreed with the ministry of the interior's approach because the law did not stipulate any such condition. The ministry of finance expressly stated that in the case of “middle class and wealthy class apartments nobody cares about whether single or married parties live in family houses.” The Central Union of Industrialists of Austria, supported by the ministry of finance, even filed a complaint against the ministry of the interior's “oppressive interpretation of the law.”Footnote 60

The ministry of the interior, however, refused to recognize the complaint and insisted that only families could occupy a family house. It referred to several analogous cases in which applications for tax-exempt status for attic apartments for servants were rejected. The ministry of finance complained that this would draw the public's ire because people would blame it for being more concerned about money than workers’ welfare. In reality, though the ministry of the interior's moralistic demands were behind the decision.Footnote 61

The interpretation at issue was based on the section of the Concessions Act that dealt with accommodating single workers in buildings in which workers’ families also lived. The article prescribed that the dwellings of working-class families be separated from those of single workers. It also ordered separate housing for unmarried people of different sexes. Because the wording of this provision was ambiguous, the ministry of finance requested that the ministry of the interior take a liberal approach and approve the exemption.Footnote 62

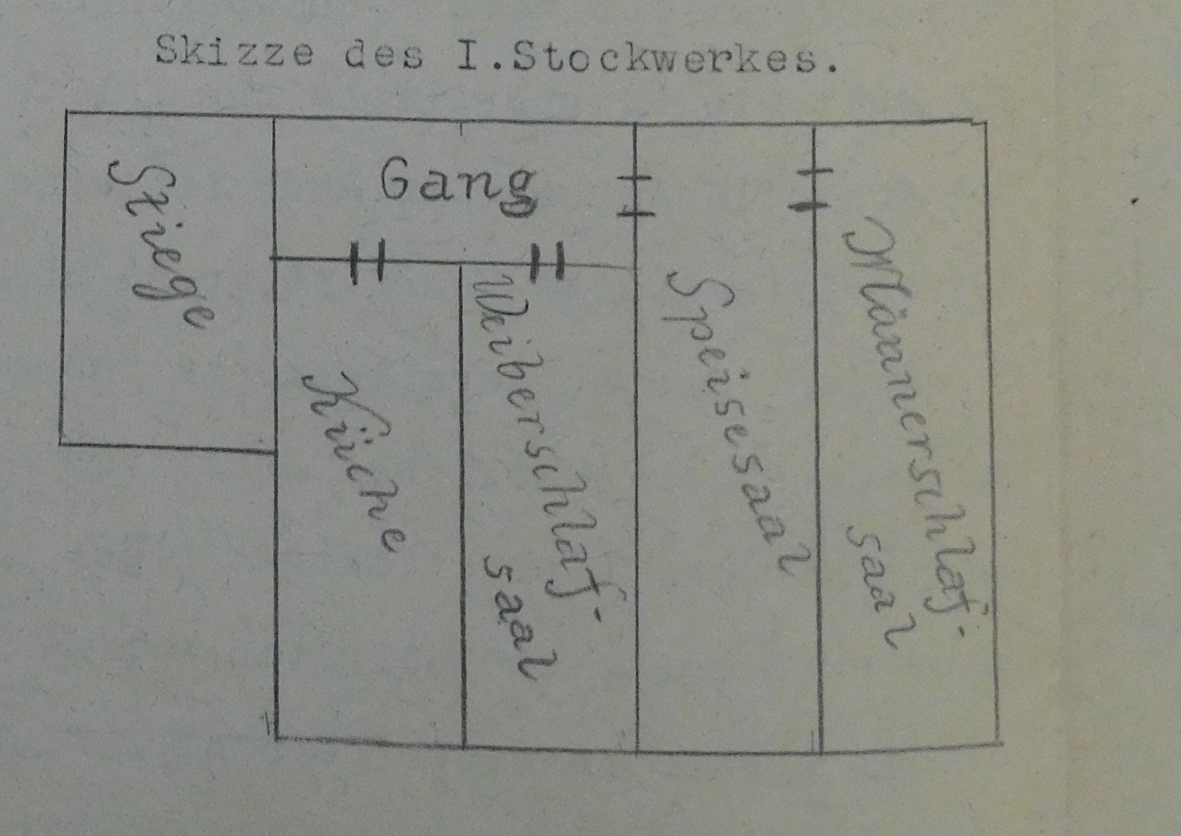

It is obvious that some middle-class officials connected workers with moral threats. They feared an undisciplined and migrating workforce who did not dutifully remain at one job all their lives. This played a key role in a family house built in the East Bohemian village of Holohlavy (Holochau) in 1911. On the ground floor of the house there were four one-room apartments for the families of permanent workers. On the first floor, two bedrooms with a kitchen and a dining room were set up for eight male and six female seasonal workers (Picture 1). The minor problem was the connection of the family house with the dormitory. For moral and hygienic reasons, the authorities took care that such a combination did not occur. The ministry of public works explicitly stated that it was necessary to “protect the inhabitants of family houses from the harmful effects of fluctuating classes.” In this case, the regulations were fulfilled because authorities ordered the building of separated entrances: one for working-class families and the other for unmarried workers.Footnote 63

In addition, a laundry room and cloakroom were to be set up so that seasonal workers could wash up dusty outer clothing and put away muddy shoes without going to the bedroom. The ministry of public works demanded that several more toilets be added to the five brick toilets in the yard. The toilets were to be separated into those for men and those for women. The ministry of finance relaxed the request. Workers worked all day outside of the dormitory where they slept only a few months a year. In winter, the dormitory was empty. Therefore, the number of toilets was sufficient in this respect.Footnote 64

Authorities’ demands about what counted as the appropriate lifestyle differed markedly not only between stable and seasonable workforces, but also between the sexes. The judgment of women was often sexualized. This clearly illustrated the problem of the common dining room for men and women at the Holohlavy's dormitory and the placing of male and female bedrooms in one “dark” corridor. The authorities strictly distinguished between men and women and insisted that they live separately. In its statement on the application for tax exemption, the ministry of finance wrote that there is the dining room between the female and male bedrooms, which prevents direct contact between the sexes (Picture 1). With a narrowed eye, it was certainly possible to tolerate. However, the ministry of public works opposed this arrangement and recommended building modifications with regard to the (moral) “quality of seasonal workers.” A second separate staircase and a new window were to be installed at the kitchen site so that female workers in the corridor would not meet their male counterparts.Footnote 65

Map 3.

No less an important problem of welfare capitalism and housing policy was the gender of the inhabitants. The owners and tenants of workers’ houses and dwellings were mainly men. Companies apparently rented housing largely to male workers. Unmarried female workers lived with their families or with guest families that could not be connected to the company.Footnote 66 For young unmarried women recruited from rural areas, industrialists built dormitories and boardinghouses. Parents allowed daughters to work in factories if they were assured of their safety and well-being. The companies established a system “moral police” and elaborate rules for life in dormitories. Women were accustomed to hard work and being subservient to male authority.Footnote 67 In the small Silesian town Zlaté Hory (Zuckmantel), the owner of the silk weaving mill, Josef Adensamer, who built a female dormitory thanks to a tax exemption in 1909, reserved the right to inspect workers “day and night.”Footnote 68

Housing could also have been an advantage offered by the company to privileged groups of workers so as to prevent them from going to competing firms. Housing was a management strategy that encouraged employees to identify with business plans and perform well.Footnote 69 An interesting example of this is the mentioned Adensamer's dormitory. It operated for a relatively short time: after five years, in early 1914, Adensamer asked for it to be converted into an apartment building. Rooms for single women were abolished and replaced by flats for two storekeepers, one consignee, an auxiliary worker, a machinist, and a foreman. The authorities considered all tenants to be workers.Footnote 70 The meaning of the decision was obvious: privileged male workers moved into the rooms of female workers. The dormitory with common bedrooms was replaced by a house with three-room and two-room apartments. The ministry recommended several small technical modifications and approved the change.Footnote 71

The Adensamer's request was one of the last tax-exemptions before the Great War broke out. As in other areas of social, economic, and cultural life, the war was a watershed for the construction of workers’ housing.Footnote 72 During the war, building permits were still being issued, and tax exemptions were granted for more buildings than recorded in official statistics. According to contemporary comments, industrial enterprises had to make greater “sacrifices” to increase the housing stock during the war than in the pre-war period. Increased construction costs were counterbalanced by extending tax exemptions and introducing new types of tax rebates and direct state support. State intervention in construction activities continued in the postwar period. The tax exemption was further extended. Construction costs could be written off. Laws were adopted to support the construction industry. Falling prices of construction material and wages of construction workers reduced the cost of constructing residential buildings.Footnote 73

Conclusion

The reasons that the Habsburg Monarchy was excluded from the family of modern industrial and welfare states are still in question. More than thirty years ago, David S. Good revised the persistent view of the Habsburg economic failure.Footnote 74 Other historians have pointed out how imperial authorities responded to pressure “from below,” supported the development of civil society, and were forced to expand the space for political and public activities.Footnote 75 Austria's bureaucratic elites contributed to the modernization of empire, which created a dense network of trade and economic ties around the world.Footnote 76 Imperial elites were not responsible for the industrial development of the individual lands, but they initiated many administrative and social reforms that transformed agrarian and rural regions into a modern industrial society.Footnote 77 Historians also stated that decades before the Great War the authorities remained passive and kept the social legislation of the 1880s unchanged. They displayed considerable political sterility to the workers’ question and did not even try to alleviate the difficulties involved. Unlike the middle-class activists, entrepreneurs, and industrialists, the authorities were not interested in social reform.Footnote 78

This study has shown that the state concessions for buildings containing healthy and affordable workers’ flats were one of the reforms. It has been noted that the acts of concessions did not improve living conditions for the neediest people.Footnote 79 This observation certainly also holds true for ambitious projects such as communal housing developments in early-twentieth-century Budapest and interwar Vienna.Footnote 80 A certain problem is the “wisdom of hindsight.” At the time these acts were passed, it was far from clear what their effects would be. Through these acts, authorities tried to galvanize industrialists to build not only apartments for directors, bookkeepers, and masters, but also houses for workers. Their impact would only become apparent several years later after ministerial officials calculated how many tax exemptions had been granted and how many apartments were built.

Historians have noted that since the 1880s, imperial authorities were deeply engaged with “family protection” and their interest substantially contributed to the enlargement of labor protection for women. Housing policy could be seen as a part of this interest as well. The authorities intervened against lifestyles deemed inappropriate and not respectable.Footnote 81 This did not only affect the Roma population in the Hungarian part of the monarchy, but it also concerned young unmarried male and female workers in the Bohemian lands.

As the study demonstrated, through a tax exemption, the authorities sought to divide “moral” places for married workers with children on the one hand and single and childless workers on the other; to differentiate “hygienic” sites for men and women; to construct locations for people of working age and unproductive retirees. The appropriate lifestyle of the working-class should be affected by supporting the construction of welfare amenities in workers’ settlements. The tax exemptions of amenities enabled workers to a greater extend to use co-op stores, libraries, canteens, nurseries, or laundry rooms. An imperial aspiration for the lifestyle of workers was so far-fetched that the authorities respected smoking as an indispensable workers’ habit, in contrast to the sale of alcohol, which was strictly prohibited in the tax-exempted houses.

Although, there is skepticism about the homogeneity of workers’ housing and privacy, and no typical working-class neighborhoods and streets in some Moravian cities were found, this study demonstrates that in other, especially Bohemian and Silesian towns, working-class areas were often built with official approval.Footnote 82 Through state concessions for the construction of workers’ housing, the authorities contributed to the formation of the working class and to its separation from other societal groups. The authorities tried to fix workers’ status and defined workers as low-income people who carried out production activities manually. They separated white-collar and blue-collar workers not only economically and socially but also spatially through tax exempted houses.

However, due to the initially high number of rejected applications, the imperial authorities had to revise their strict approach and adopt a more “liberal” one. As a consequence, tax exemptions for more buildings were granted, including middle-class tenants. Entrepreneurs’ and directors’ houses were not further tax-exempted, but accountants, supervisors, and officials’ widows were, due to their low salary and the nature of their work or even their “character,” considered to be working-class and their housing got state concessions.

Compared to the United States, which originally had in some respects similar economic parameters, state and public authorities in the Habsburg Monarchy tried to govern welfare capitalism.Footnote 83 Through the Concessions Act, the authorities sought to influence the decisions of industrial enterprises and regulate the construction of company housing. In this manner, they aimed to bring about social welfare and more liberation to workers. Regulations that ensured rent ceilings, healthy flats, and stable long-term housing, should mitigate the unequal relations between industrial landlords and working-class tenants.

The Empire's social policy should relieve maladies of modern society and reconstruct moral order where industrial anomy emerged. In the Bohemian lands, where industrialization took place rapidly, the authorities improved the lives of many workers’ families and revitalized places of daily routines. State concessions and tax exemptions were not only meant to stimulate the mass construction of workers’ housing, but they prescribed relatively high social and hygienic standards. Like most modernity projects, this revitalization was accompanied by contradictions between the promises of freedom and the increase of discipline. Bohemian, Moravian, or Silesian workers who brought their original habits to tax exempted houses and flats, were put under the scrutiny of the imperial officials and company managers. The breeding of domestic animals and the cultivation of vegetables in small gardens were not possible to forbid because of the workers’ livelihoods. But these activities should be clearly separated from the workers’ homes to avoid unhygienic conditions and harmful soil to avoid infections and diseases.

The maintenance of these standards could surely be a byproduct of the strict application of implementing regulations. Industrialists were forced to adjust to the planned changes in company housing in order to submit a successful application for tax exemption. They responded to legal changes in various ways, which did not have to conform to social improvements and workers’ interests. They wanted to save money on any construction regardless of whether it was workers’ flats or managers’ houses. Certainly, without business finance, most workers’ houses would not have been built. But it should not be forgotten that many houses were built thanks to the state concessions that the tax exemptions for the construction of workers’ buildings provided. Some houses were even erected only due to the decisions of the imperial government because companies saved money and could build more houses than originally planned.