Introduction

Palliative care is an approach to care that can be delivered by primary care and/or specialist-level (e.g., oncology) providers to support patients and their families facing chronic illness across the disease continuum (Breitbart and Alici Reference Breitbart and Alici2014). Patients receiving palliative care can be seen for outpatient services, need not to homebound, and can receive curative treatment. Globally, every year, close to 40 million people need palliative care, and yet only about 3 million can access the palliative care they need (Connor and Gwyther Reference Connor and Gwyther2018; Knaul et al. Reference Knaul, Farmer and Krakauer2018). Consequently, on average, 18 million people die with avoidable pain and suffering. The discrepancy between need and actual access to palliative care is due to a myriad of issues that include (a) lack of access or late referral to palliative care, (b) lack of health professionals trained in palliative care, and (c) limited knowledge about palliative care by those in the general public and patients (Connor and Sepulveda Bermedo Reference Connor and Sepulveda Bermedo2018). To this latter point, a growing number of studies explore the value and need for patients to be aware of palliative care and what it can offer them while living with serious, life-limiting illness (Check et al. Reference Check, Kaufman and Kamal2020; Langan et al. Reference Langan, Kamal and Miller2021).

In recent years, there has been significant growth of palliative care both as a medical specialty and as an important approach to care delivered by multiple provider types. Despite increased awareness of palliative care within certain health-care settings like oncology, those living with serious illness often lack knowledge about what palliative care is and what its care can offer to improve their quality of life. There is also poor awareness in the general public about palliative care, which can lead to missed opportunities in seeking this beneficial service when it becomes needed or useful to receive (Huo et al. Reference Huo, Hong and Grewal2019). Consequently, lack of knowledge and even misconceptions (e.g., equating palliative care only with end-of-life care, in the last days or weeks of life) can have negative impacts on how patients and their families access needed care to improve quality of life (Bakitas et al. Reference Bakitas, Tosteson and Li2015; Bookbinder et al. Reference Bookbinder, Blank and Arney2005; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Webster and Bowers2016; Lo et al. Reference Lo, Chan and Chan2009; Temel et al. Reference Temel, Greer and Muzikansky2010).

Independent of which type of provider offers palliative care to their patients, there has also been growing momentum to advocate for and provide early engagement with palliative care in oncology settings. In fact, integration of palliative care in the treatment of patients with cancer has resulted in more effective symptom management, improved patient understanding of their disease and prognosis, more timely transitions to hospice, decreased chemotherapy use near the end of life, higher levels of patient and family satisfaction, and even improved survival (Kavalieratos et al. Reference Kavalieratos, Corbelli and Zhang2016; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Stukel and Stall2020, Reference Quinn, Wegier and Stukel2021).

However, while the integration of palliative care with oncology services progresses, disparities in access to palliative care remain for individuals with non-cancerous chronic disease (Kavalieratos et al. Reference Kavalieratos, Corbelli and Zhang2016; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Stukel and Stall2020). Inaccurate knowledge, negative beliefs, and misperceptions about palliative care among people living with non-cancerous chronic diseases may inhibit early interest in, communication about, and integration of palliative care following illness diagnosis. Combined, these factors can present as a potential barrier to care that can make a difference in the quality of life of chronically ill patients who may experience high physical and psychological needs that could be effectively addressed by palliative care.

There is limited evidence investigating how knowledge, misconceptions, and beliefs about palliative care vary from those with cancer compared to those with non-cancerous chronic disease such as heart failure and non-cancerous lung disease and even among the general public without serious or chronic illness. In this study, we chose to examine heart failure and non-cancerous lung disease as they are among the top 5 chronic diseases that account for two-thirds of all deaths in the United States (Raghupathi and Raghupathi Reference Raghupathi and Raghupathi2018).

The overall aim of the study was to examine knowledge of and misconceptions about palliative care. We had 2 objectives to address our aim. Our primary objective was to examine knowledge about palliative care across groups with serious, life-limiting illness (i.e., people with cancer compared to non-cancerous chronic disease). In addition, in these 2 groups, we addressed whether among those who were aware of the term “palliative care,” misconceptions exist regarding the goals and beliefs about palliative care (e.g., frequently conflate palliative care with hospice or end-of-life care). Our secondary objective was to explore palliative care knowledge among those with cancer and non-cancerous chronic disease compared to those in the general public without life-limiting illness.

Methods

Using free and publicly available survey responses by the National Cancer Institute in the U.S. (https://hints.cancer.gov/), we analyzed data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). HINTS is a nationally representative dataset (collected biennially since 2003) about cancer-related information (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Kreps and Hesse2004). There are 14 iterations of the HINTS dataset. The survey was submitted to the National Institute of Health’s Office of Human Subjects Research and was considered exempt from institutional review board. This exemption extends to all 14 iterations of the data from 2003 to 2020. For this specific study, we used the HINTS 5, Cycle 2 survey in (2018), which included a battery of questions specifically about palliative care, designed to highlight knowledge, attitudes, and health information about cancer.

Of 3,504 survey respondents, 59 were excluded due to incomplete outcome information. A total of 585 respondents reported a history of cancer (e.g., breast, lung, and colorectal cancer). Other than cancer, a total of 543 respondents reported having a specific non-cancerous chronic disease health condition such as heart failure or lung disease (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder). Of the total survey respondents, those with neither cancer nor chronic disease were included in the regression model as the referent group (n = 1696).

Demographics and disease characteristics

HINTS (via mailed questionnaire) also collect respondent background on the following demographic characteristics: gender, marital status, census region, age, race/ethnicity, health status, education, insurance type and income. Their disease type, chronic illness or cancer, was also reported. Rural respondents were identified using the 2013 Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties (>5).

Knowledge of palliative care

The main outcome was self-rated palliative care knowledge. Respondents were asked the question, “How would you describe your level of knowledge about palliative care?” with the response options being, “I’ve never heard of palliative care,” “I know a little bit about palliative care,” and “I know what palliative care is and could explain it.” Knowledge of palliative care was dichotomized; responses of “I know what palliative care is and could explain it” were allocated a value of 1, while the other responses were grouped together and allocated a value of 0.

Goals of palliative care

Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with 4 different potential goals of palliative care: (1) “Help friends and family to cope with a patient’s illness,” (2) “Offer social and emotional support,” (3) “Manage pain and other physical symptoms,” and (4) “Give patients more time at the end of life.” They rated their agreement with each item on a four-point Likert scale, which included the options “Strongly Agree,” “Somewhat Agree,” “Somewhat Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree,” or could select an option of “Don’t Know.” Higher scores indicated greater respondent agreement.

Beliefs/misconceptions about palliative care

Prevalence of misconceptions regarding palliative care was assessed only among respondents reporting knowledge of palliative care. Respondents reported their level of agreement with several beliefs about palliative care on the same 4-point Likert scale (or the option of selecting “Don’t Know”) that they ranked goals of palliative care. They indicated their level of agreement with 5 beliefs, including “Accepting palliative care means giving up,” “It’s a doctor’s obligation to inform all patients with cancer about the option for palliative care,” “If you accept palliative care, you must stop other treatments,” “Palliative care is the same as hospice care,” and “When I think of palliative care, I automatically think of death.” Misconception was defined as a response of “somewhat agree/strongly agree” to each of the following 4 items: (1) “Accepting palliative care means giving up,” (2) “If you accept palliative care, you must stop other treatments,” (3) “Palliative care is the same as hospice care,” and (4) “When I think of ‘palliative care,’ I automatically think of death.” The outcome “Any misconceptions” indicated the presence of any one of the 4 misconceptions about palliative care evaluated in the survey.

Statistical analysis

We accounted for complex sample designs in variance estimation using repeated sampling with 50 jackknife replicate weights that was developed and recommended for HINTS analytics (HINTS 5, 2018). Equivalence of group characteristics was tested using the Wald test of observed weighted counts.

We estimated the association between non-metro/non-urban dweller status and knowledge of palliative care using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for respondent characteristics. We used complete case analysis and excluded respondents missing information on covariates (N = 680). Characteristics with high missingness were excluded from regression analysis due to small numbers of respondents in non-metro/non-urban dweller areas (English proficiency, sources of medical information, health status, and insurance status) as well as variables with high multicollinearity (income). Models controlled for geographic variation using fixed effects for census division.

Results

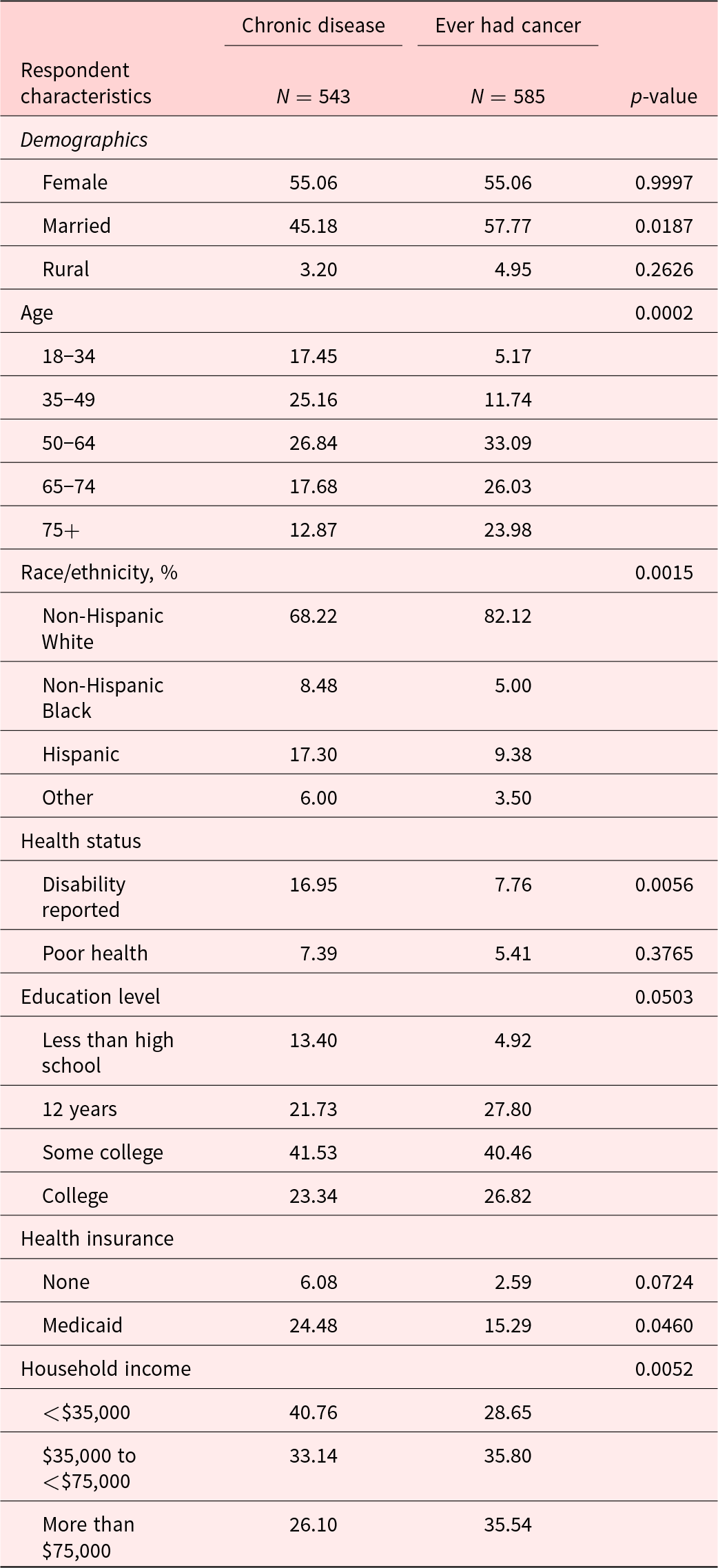

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of respondents in the cancer and non-cancerous chronic disease groups (n = 1,128). Across both samples, there was an even split across gender (55.1% females and 44.9% males). Compared to those with cancer, those with non-cancerous chronic disease were less likely to be married, more likely to be under age 50, more likely to be non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic, and more likely to report a disability. Those with non-cancerous chronic disease were also more likely to have lower socioeconomic status as measured by education, access to health insurance, and household income.

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents ever diagnosed with cancer compared to other non-cancerous chronic disease

Notes: Survey weights were applied to reflect national estimates for responses. Percentages are among nonmissing responses for each variable.

Knowledge about palliative care

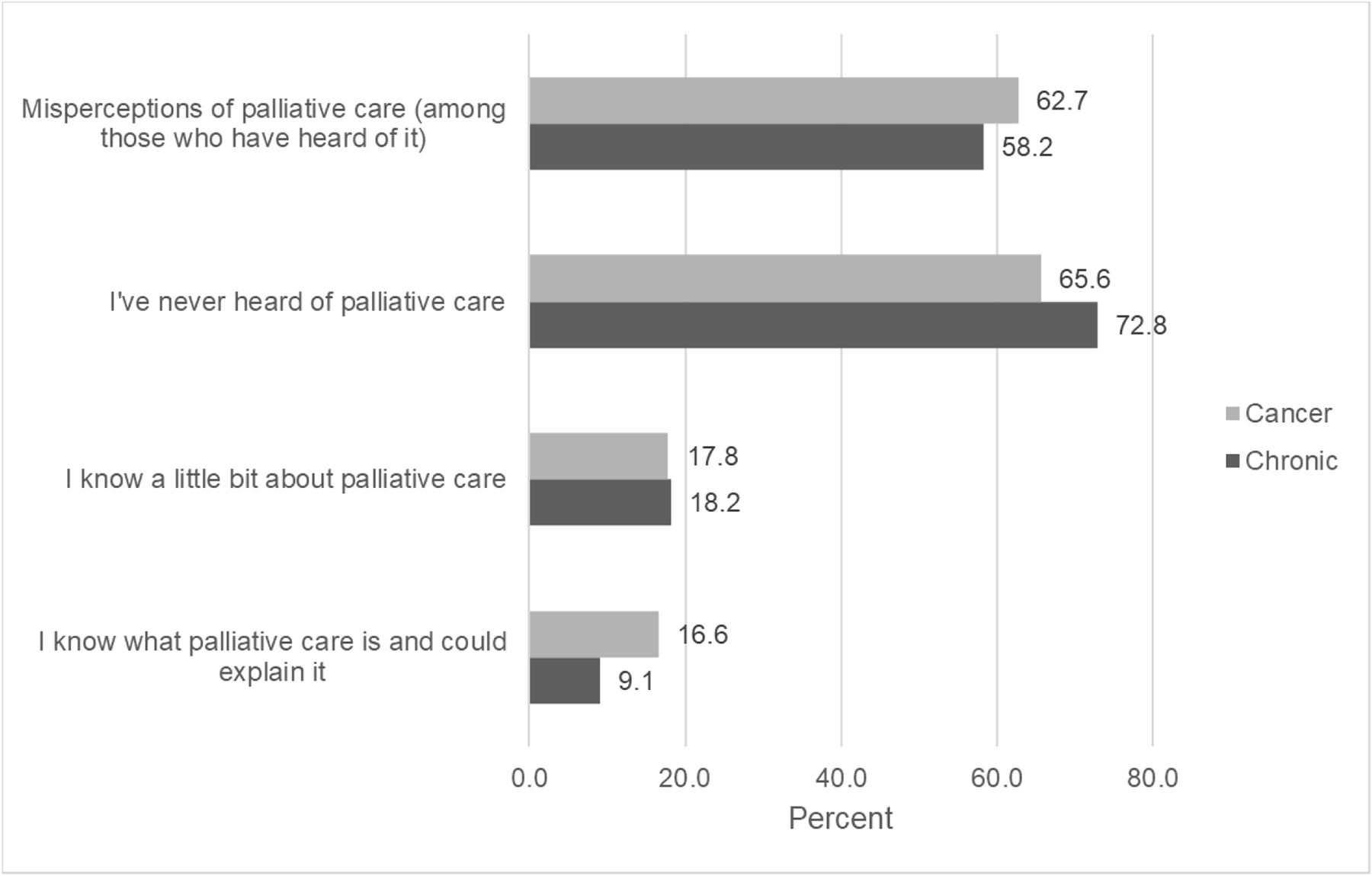

Respondents answered 3 items to describe their level of knowledge about palliative care. Most respondents reported they had never heard of palliative care, 65.6% among cancer and 72.8% among chronic conditions respondents (see Fig. 1). Respondents in the non-cancerous chronic disease group (n = 543) were significantly less likely to report a high level of palliative care knowledge (e.g., knowing what palliative care is and being able to explain it) than respondents in the cancer group (n = 585), (9.1% non-cancerous chronic disease group vs. 16.6% cancer group, p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Knowledge of palliative care for respondents with non-cancerous chronic disease or ever had a cancer diagnosis.

Note. Misperceptions and beliefs are evaluated among 371 respondents with any knowledge of palliative care (and endorsed “agree” or “strongly agree” to survey items). Respondents in the non-cancerous chronic disease group were significantly less likely to report a high level of palliative care knowledge (e.g., knowing what palliative care is and being able to explain it) than respondents in the cancer group.

Goals about palliative care

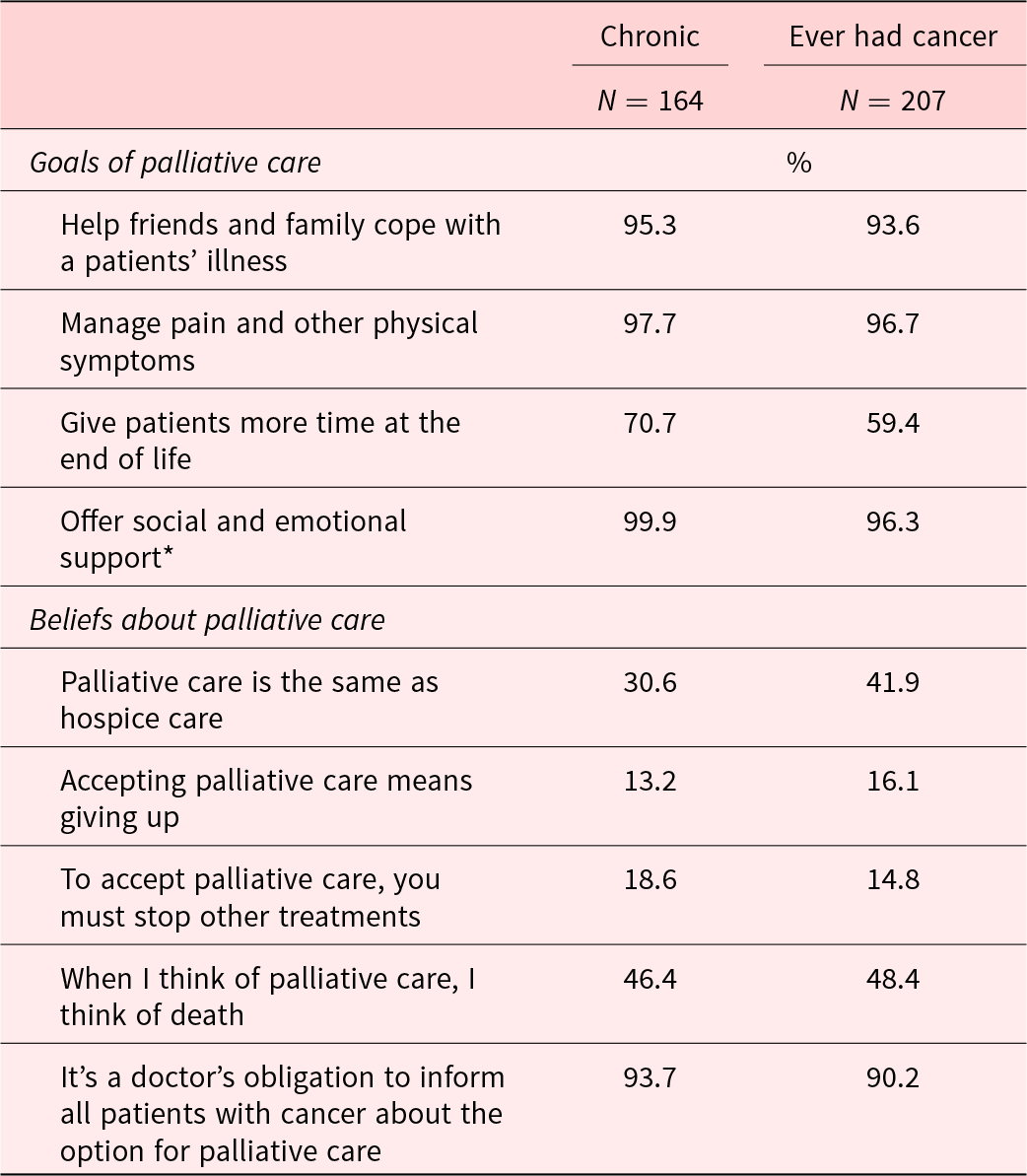

The majority of respondents in both groups similarly agreed about the goals of palliative care, except for the goal “To give patients more time at the end of life.” This goal was endorsed by 70.7% of respondents with non-cancerous chronic disease compared to 59.4% of respondents with cancer (Table 2).

Table 2. Goals and beliefs about palliative care among respondents with any knowledge by condition

Notes: Percentages are weighted to reflect national estimates for responses, while N reflects number of respondents. Goals of Palliative Care and Belief/Misconceptions were assessed using Likert Scaling. Misconception about Palliative Care was defined as a response of “somewhat agree/strongly agree” to the first 4 of the 5 listed items under Beliefs about Palliative Care.

Beliefs about palliative care

We also assessed misconceptions about palliative care among respondents (N = 371) who endorsed having any knowledge of palliative care (i.e., endorsed either item of “I know a little bit about palliative care” or “I know what palliative care is and could explain it to someone else”). A total of 62.7% of respondents in the cancer group compared to 58.2% of respondents in the non-cancerous chronic disease group endorsed greater misconceptions; however, this difference was not significant (Fig. 1).

Regression results

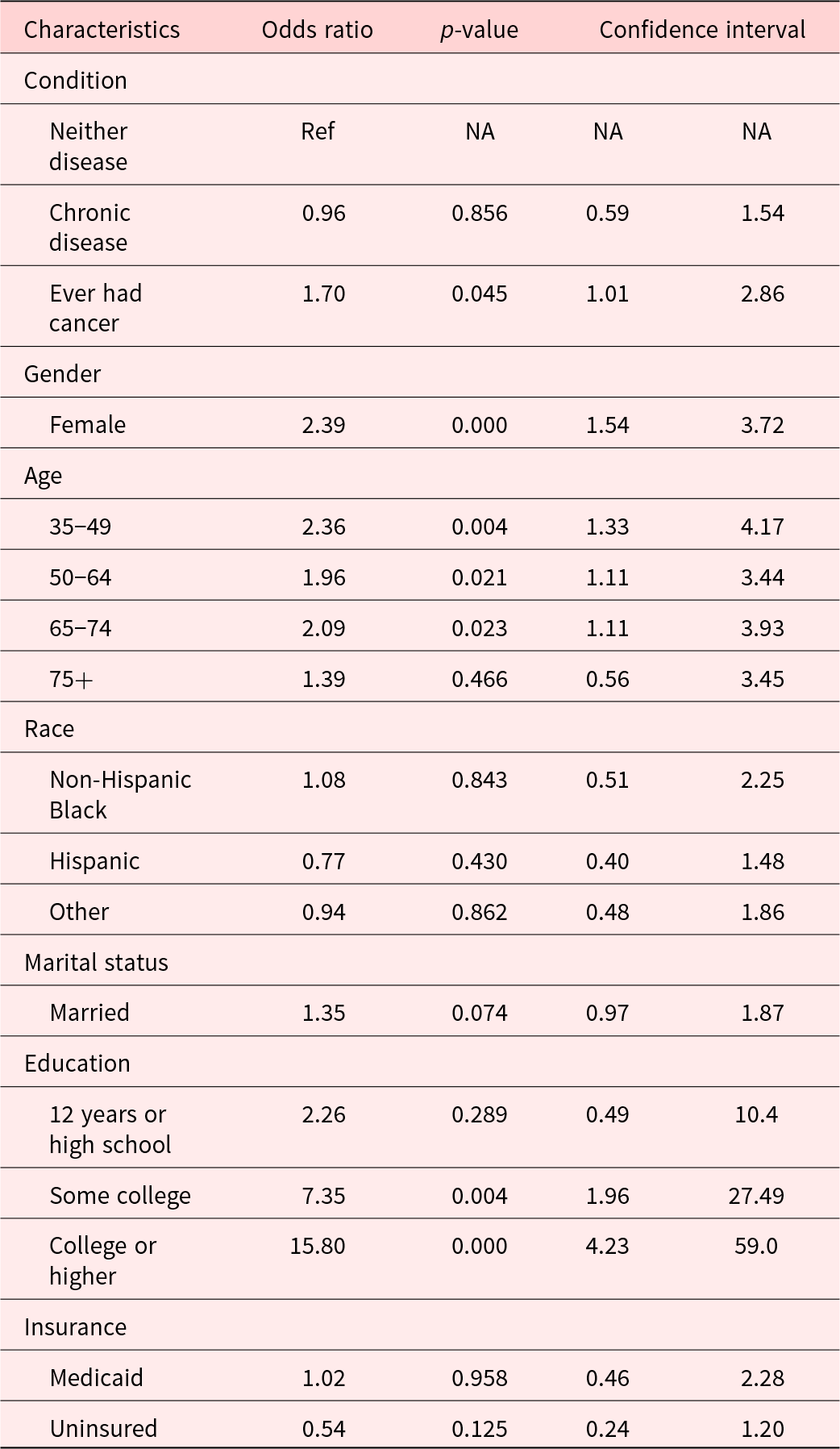

Our secondary objective was to compare the 2 groups with cancer or chronic disease to persons with neither cancer nor chronic disease. Results of regression analyses indicated that, after controlling for available respondent characteristics (e.g., age, race, health status marital status, health insurance, and socioeconomic status), the differences in palliative care knowledge between groups was significant (see Table 3). Compared to respondents with neither cancer nor chronic disease, respondents with a history of cancer had greater odds of high palliative care knowledge (odd ratio [OR] 1.70; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01, 2.86). However, odds of palliative care knowledge in the non-cancerous chronic disease groups were similar to respondents without chronic disease or cancer (OR = 0.96; CI = 0.59, 1.54).

Table 3. Odds ratios of respondent characteristics associated with a high level of palliative care knowledge

Survey weights were applied to 2,824 respondents with nonmissing characteristics to reflect national estimates for responses. High level of palliative care was defined as a response of “I know what palliative care is and could explain it.”

Discussion

Overall, results from our study using a nationally representative sample suggest that knowledge of palliative care was quite low across all respondents, including those with cancer, those with other non-cancerous chronic diseases, and those with neither. In addition, differences and disparities in palliative care knowledge were seen among those with non-cancerous chronic disease compared to individuals with cancer. Specifically, compared to people with cancer, people with non-cancerous chronic disease were less likely to report knowledge of palliative care. Moreover, after adjusting for socioeconomic and other factors, respondents with chronic non-cancerous disease were no more likely to know about palliative care than people without cancer or other non-cancerous chronic disease. These findings have significant implications for health-care systems not just within the United States but also more globally as chronic disease is the leading cause of death and disability and a cost driver in annual health-care spending (Daniels et al. Reference Daniels, Donilon and Bollyky2014; Hoover et al. Reference Hoover, Crystal and Kumar2002; Patel et al. Reference Patel, Galsky and Chagpar2011).

More fact-finding as to the reasons why these differences in knowledge exist is important. One potential reason for the lack of knowledge about palliative care found in this study is that this approach to care is not being discussed as an option in chronic care management for serious illnesses like heart failure and lung diseases (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder). Yet, poor knowledge about palliative care was also seen among patients with cancer. Knowing little about palliative care means that those who would benefit from this approach to care will continue to needlessly suffer from the pain associated with serious, life-limiting illness. In fact, research suggests that 75% of patients living and coping with any type of serious, life-limiting illness can benefit from palliative care, and yet only a minority, as low as 14%, receive this specialty type of care (Etkind et al. Reference Etkind, Bone and Gomes2017; McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Rosenwax and Holman2006).

These results also suggest that those living with non-cancerous chronic disease might be facing several social disadvantages that place them at risk for worsened health-care outcomes and poor quality of life. It is well known that those with multiple and diverse intersecting identities (e.g., across race, ethnicity, ability status, education attainment, and income) are often marginalized and experience health-care inequalities (Iannacone Reference Iannacone2017; Love and Liversage Reference Love and Liversage2014). Individuals who are underprivileged are known to underuse palliative care, often because the existing structural systems that exist in health care are too large to overcome (Belisomo Reference Belisomo2018; Hlubocky Reference Hlubocky2014; Iannacone Reference Iannacone2017). Not surprisingly, historical mistreatment of individuals who identify as a person of color and those from underserved backgrounds is a health-care system’s problem that influence mistrust and disillusionment. As a result, receiving this approach to care may not be welcomed by patients and families, so system’s solutions will be needed to illustrate the benefit of palliative care and decrease inequitable palliative care use (Johnson Reference Johnson2013).

In addition to assessing level of knowledge about palliative care, we assessed goals and misconceptions about palliative care among respondents who endorsed knowing at least a little about palliative care. For the most part, non-cancerous chronic disease and cancer respondents highly agreed that palliative care offers opportunities to help friends and families cope with illness, offer social and emotional support, and provide pain and symptom management. However, we found that, compared to respondents with cancer, those with non-cancerous chronic disease were more likely to agree that a goal of palliative care is to “give patients more time at the end of life.” This finding is intriguing as palliative care is often and inaccurately viewed as synonymous with end of life. A plausible explanation for this latter finding may be attributed to a general misunderstanding that any medical care treatment received by a patient is intended to extend their life versus focus on their quality of life.

Notably, cancer respondents also highly endorsed this palliative care goal. It may be that the fixed ordering of the goals of palliative care items in the HINTS questionnaire resulted in a halo effect as the first 3 items were highly rated overall across both groups (Bogner and Landrock Reference Bogner and Landrock2016). Additionally, high agreement of this item may represent a positive yet inaccurate belief about palliative care (Taber et al. Reference Taber, Ellis and Reblin2019). Lastly, regression results showed that respondents with cancer were more likely (i.e., have higher odds) of having palliative care knowledge compared to those with chronic disease and those without. This finding is not too surprising given the large push to integrate palliative care in parallel with oncology to improve patient outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

The use of national survey data is a major strength of this study. This rich data source provides generalizable information from respondents across diverse demographics. There are limitations that include the cross-sectional nature of this study, limitations to sampling strategies including the survey being available in only 2 languages (i.e., English and Spanish). Moreover, cancer stage and progression of chronic disease is not captured in HINTS survey data. This missing information may have influenced survey responses (e.g., those with advanced cancer or disease may have more knowledge of palliative care compared to those earlier in the disease trajectory). As with any survey, some respondents may have answered this survey in a socially desirable manner and/or interpret individual survey items differently, which may influence the results. Nonetheless, given that participant responses were entirely anonymized and no incentives (in exchange of survey completion) were offered, we anticipate social desirability to be low in our study.

Conclusion

Despite the known benefits of palliative care and the growing availability of this approach to care across hospital care systems, referrals and follow-up for palliative care remain low (Humphreys and Harman Reference Humphreys and Harman2014). Overall, across respondents, we found significant gaps in knowledge as well as misunderstandings about palliative care and what it offers. Particularly, most respondents in both cancer and non-cancerous chronic disease groups in this United States-based study had “never heard of” palliative care. Well-documented contributors to poor knowledge about palliative care include poor accessibility and availability of educational content, referrer reluctance, and poor communication about the benefits of palliative care (e.g., evidence that palliative care may extend life) from inadequately trained health-care providers.

Gaps in knowledge were especially evidenced among those who identified as racial/ethnic and sexual/gender minorities, were from a lower socioeconomic status, and resided in rural areas. Improving awareness and access to palliative care among chronic disease groups is critical for promoting equity in health care and end-of-life care. More research is clearly needed to elucidate contributors to misperceptions for individuals with chronic diseases who may inadvertently go without accessing care that can enhance their quality of life. Educational efforts and outreach across multiple levels (e.g., patient, family, and provider) to target awareness, knowledge, and beliefs about palliative care for underserved and socially disadvantaged people living with chronic illness are important next step. Systems solutions are needed. To this point, and as an example, it may be of critical interest for non-palliative care providers (e.g., in primary care) to consider their own understanding and role in referring their patients early to palliative care. Ideally, these efforts could also increase awareness about accessing palliative care elsewhere (e.g., via telehealth) if such types of care are unavailable locally.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who took part in the HINTS survey. We would like to thank 2 student members from our wider team, Daniel Lee and Lauren Howard, for their timely support. Portions of this work paper were presented at the 2022 State of the Science Meeting with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM).

Author contributions

All authors made a substantial contribution to the concept or design of the work, acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. Ramos drafted the article, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and approved the version to be published.

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Cancer Institute (KR, K08CA258947; LP, R01CA201179). This work was also supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Durham VA Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (CIN 13-410).

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.