The Vulnerable fishing cat Prionailurus viverrinus may be approaching extinction in South-east Asia (Duckworth, Reference Duckworth, Appel and Duckworth2016). There are few recent records from across the region (Mukherjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Appel, Duckworth, Sanderson, Dahal and Willcox2016). Although this may be a result of low survey effort, it does suggest that populations in these countries are either very small, plausibly extinct (e.g. Vietnam; Willcox et al., Reference Willcox, Phuong, Duc and An2014) or entirely absent (e.g. Lao PDR; Mukherjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Appel, Duckworth, Sanderson, Dahal and Willcox2016). A single camera-trap photograph of a fishing cat taken in 2003 in Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary (Rainey & Kong, Reference Rainey and Kong2010) may be Cambodia's only previously confirmed record. Although there have been numerous unconfirmed claims (e.g. Royan, Reference Royan2009), and captive fishing cats have been held in Phnom Tamao Zoo (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Poole, Tizard, Walston and Timmins2005), their presence in other parts of the country cannot be verified. Cambodia retains large areas of potentially suitable wetland habitats similar to those used by fishing cats in other countries (e.g. Adhya, Reference Adhya2011; Cutter, Reference Cutter2015). These include marshes, swamps, tidal creeks, rice paddies and mangroves. Cambodia's coastal mangrove forests have not been exploited as heavily as in neighbouring countries (Marschke & Nong, Reference Marschke and Nong2003), and mangroves are known to provide habitat for fishing cats in India (Mukherjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Adhya, Thatte and Ramakrishnan2012). With the aim of detecting fishing cats in Cambodia we deployed camera traps at four wetland sites covering a wide area in the south of the country, three within and adjacent to coastal mangroves and one in Botum Sakor National Park.

The four sites were chosen based on preliminary investigations and interviews with local people that indicated they may support fishing cats. All sites are either nationally or privately protected for conservation. Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary (246 km2) is located near the Thai border in Koh Kong Province (Fig. 1) and overlaps the Koh Kapik and Associated Islets Ramsar Site (Marschke & Nong, Reference Marschke and Nong2003). It is part of one of the best conserved mangrove forests in the Gulf of Thailand (Marschke & Nong, Reference Marschke and Nong2003). The Sanctuary is adjacent to Botum Sakor National Park (1,826 km2), which is located on a peninsula along the south-west coast (Fig. 1), and comprises lowland evergreen and semi-evergreen broad-leaved forest, melaleuca forest, grassland, mangrove and patches of Oncosperma tigillarium palm. Botum Sakor National Park was the site of a suspected (Mukherjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Appel, Duckworth, Sanderson, Dahal and Willcox2016) fishing cat record from 2008 (Royan, Reference Royan2009). Ream National Park (147 km2) has extensive mangroves, with adjacent forests, mudflats and freshwater marshes (IUCN, 2003), and is bordered by Prey Nup to the south. At Prey Nup we surveyed a 10 km2 privately protected mangrove forest that runs along the Kampong Smatj River, backed by rice paddies.

Fig. 1 Camera-trap locations in Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary, Botum Sakor National Park, Ream National Park, and Prey Nup, in southern Cambodia.

During January–May 2015 we deployed 16 8-megapixel Trophy Cam HD Hybrid Trail infra-red flash cameras (Bushnell Corporation, Overland Park, Kansas) in mangroves and adjacent freshwater wetlands and waterholes (known locally as trapeangs) at the four sites (Table 1). Camera-trap stations were selected following the advice of local people and park rangers. Fresh fish baits were staked in front of each camera trap. When a camera's motion sensor was activated three photographs were taken consecutively, followed by a 60-second video. The minimum gap between photograph/video captures was 1 hour. A capture therefore comprised any number of photographs and videos of the same individual, or individuals, taken within 1 hour of each other. Data on large and medium-sized mammals, birds and reptiles, including date, time and behaviour, were collated from camera-trap photographs and videos. Capture frequency was calculated as the number of captures per 100 trap-nights.

Table 1 Details of camera-trap stations deployed at Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary, Ream National Park, Prey Nup and Botum Sakor National Park in southern Cambodia (Fig. 1), with the number of trap-nights and a description of the habitat for each station.

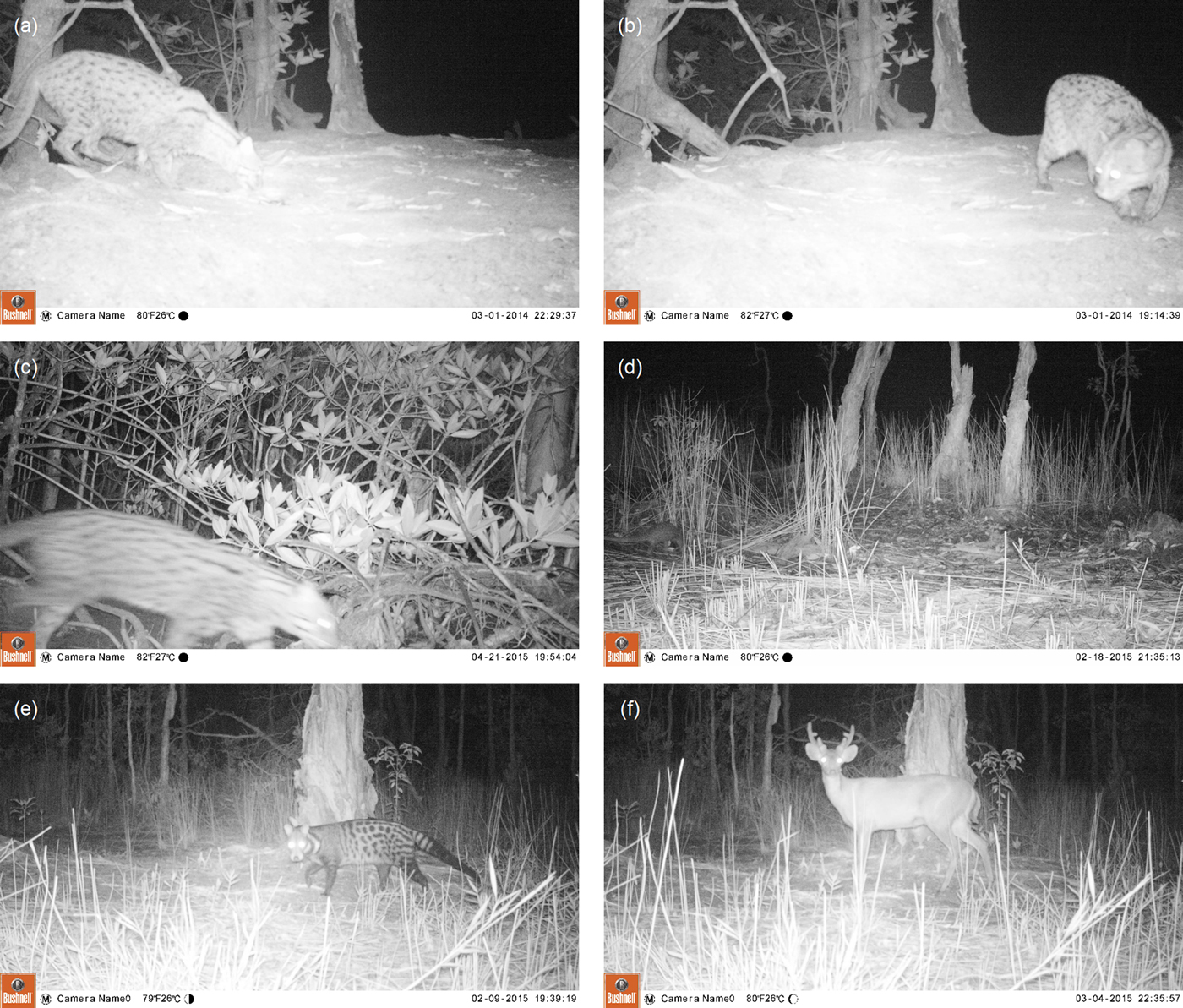

We recovered 13 cameras, deployed for a total of 1,077 trap-nights. Twenty-five species (14 mammals, 10 birds and one reptile), eight of which are categorized as threatened on the IUCN Red List (Table 2; Plate 1), were recorded from the four sites. Humans were the most frequently recorded, followed by the common palm civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus and the little egret Egretta garzetta (Table 2). The largest number and greatest abundance of threatened species were recorded from Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary, which also had the highest recorded species richness and total number of photograph captures. However, sites were not directly comparable because of differences in sampling effort, of which Peam Krasop had the highest (Table 1). Most of the people photographed were setting and collecting crab traps, fishing or collecting non-timber forest products, and many of them were accompanied by domestic dogs. Photographs/videos of fishing cats were recorded at station 1 in the Sanctuary on eight separate occasions (Plate 1). In the videos, cats were observed sniffing, licking and marking the ground (Supplementary Video S1) and defecating (Supplementary Video S2). One video showed a wet cat, apparently having emerged from the water (Supplementary Video S3). A fishing cat was photographed at station 9 in Ream National Park (Plate 1). There were no records of fishing cats from either Prey Nup or Botum Sakor. Both trap stations that recorded the fishing cats were located in mangrove forests. The station at Peam Krasop was also visited by smooth-coated otters Lutrogale perspicillata, common water monitors Varanus salvator, long-tailed macaques Macaca fascicularis, and people and their domestic dogs (Table 2). The station at Ream National Park was also visited by a leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis, common palm civets, Javan mongooses Herpestes javanicus and people.

Plate 1 Camera-trap photographs of (a, b) fishing cat Prionailurus viverrinus, Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary, (c) fishing cat, Ream National Park, and (d) Sunda pangolin Manis javanica, (e) large-spotted civet Viverra megaspila, and (f) hog deer Axis porcinus, in coastal mangroves of southern Cambodia.

Table 2 Medium–large bodied species recorded by camera traps in Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary (six sites (two failed), 500 trap-nights), Ream National Park (five sites (one failed), 284 trap-nights), Prey Nup (two sites (one failed), 71 trap-nights) and Botum Sakor National Park (two sites, 222 trap-nights), in southern Cambodia (Fig. 1). Species are grouped according to their status on the IUCN Red List.

As has occurred elsewhere (e.g. Mukherjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Adhya, Thatte and Ramakrishnan2012; Cutter, Reference Cutter2015), hunting and persecution are potential threats to fishing cats in coastal Cambodia. In July 2015 we received a report of an alleged fishing cat having been killed in Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary by a local fisher in retaliation for raiding his nets. Although we could not confirm that the animal killed was a fishing cat, this indicates that mammalian predators are persecuted at this site. Local people at all sites reported that fishing cats, or morphologically similar species, have been persecuted and also captured for the wildlife trade.

Our photographs/videos confirm that fishing cats are still present in Cambodia, at two mangrove sites where they were previously unrecorded. In addition to the discovery of fishing cats we also recorded five other threatened species at Peam Krasop, highlighting the Sanctuary's importance for threatened species conservation. However, the Sanctuary was subjected to a much greater survey effort than the other sites, which were all home to a diversity of species and are thus also worthy of further conservation effort. Despite the threat posed by hunting and persecution our findings are encouraging, as our relatively modest survey effort yielded records of fishing cats and a number of other threatened species. Extensive surveys of Cambodia's mangroves are warranted, as they may be a stronghold for fishing cats and other threatened species.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Minister and the Head of General Administration of Nature Conservation and Protection from the Ministry of Environment, and the Department of Fisheries Administration of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries for permitting this research. We thank Rob Overtoom for allowing access to Prey Nup, and local rangers and authorities who assisted in the field. Chhin Sophea and Frederic Goes assisted with bird identification. Funding was generously provided to the Centre for Biodiversity Conservation at the Royal University of Phnom Penh by the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study design, analysed camera-trap data and wrote the article. TR, VHM and JH undertook field work. TR, VHM and NJS summarized the camera-trap data. TR and NJS managed the programme, NJS obtained the funding.

Biographical sketches

Ret Thaung is a graduate of Fauna & Flora International (FFI)’s MSc in Biodiversity Conservation at the Royal University of Phnom Penh. She is currently conducting applied conservation research on Asian elephants in Cambodia. Vanessa Herranz Muñoz is studying Cambodia's fishing cats. Jeremy Holden specializes in camera trapping rare and cryptic animals in South-east Asia. Daniel Willcox has reviewed the status of fishing cats in Vietnam and has conducted field surveys of small carnivores in South-east Asia. Nicholas Souter specializes in research on threatened species, and managed FFI's University Capacity Building Project during 2013–2016.