Like all wars, the Vietnam War joined economies, not just armies. The American War, as Vietnamese know it, pitted the world’s greatest industrial economy against a small agrarian society grasping for a postcolonial future. The United States in 1955 produced a quarter of the world’s economic output; Vietnam, around 0.3 percent.Footnote 1 If material capabilities determine the outcomes of wars, this one should have been inevitable.

It was not, and the scale of the mismatch only compounded American frustration. What the Vietnam War demonstrated, historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., mulled, was not the omnipotence of American power but “the inability of the most powerful nation on earth to subdue bands of guerrillas in black pajamas.”Footnote 2 Conversely, for Vietnam’s communists the dismantling of South Vietnam constituted an asymmetric triumph, a victory that has enshrined Võ Nguyên Giáp, North Vietnam’s defense minister and military mastermind, among the twentieth century’s greatest military strategists.Footnote 3 Few have won so much with so little.

And yet, narrating the Vietnam War as a David-and-Goliath encounter risks succumbing to an alternative overdetermination, in which the hubris and myopia of US elites make defeat inevitable. We should be mindful of the political constraints that inhibit the translation of economic capability into coercive military power. And verdicts may, in any case, be premature.

The United States fought in Indochina to secure the frontiers of containment, including for liberal globalization. Today, the United States is Vietnam’s largest trading partner, and Vietnam is a vital locus in an Asia–Pacific globalization system. The US Navy is back in Cam Ranh Bay, and surveys of Vietnamese opinion reveal stunning levels of enthusiasm for the United States. In the most recent Pew survey, 84 percent of Vietnamese affirmed a favorable view of the United States, which made them the world’s most pro-American respondents: even more enthusiastic than Israelis (81 percent) and almost as positive as Americans themselves (85 percent).Footnote 4

None of this is to say that the long view reveals the United States to have been the war’s true victor, only that the adjudication of winners and losers may be a perilous task for historians. This chapter, for its part, undertakes three distinct tasks. It begins with an analysis of the war’s political economy. The war, it argues, showcased a distinctive model of Cold War imperialism that was not extractive, as European colonialism had been, but based upon the outward dissemination of resources. The chapter turns next to the war’s costs, benefits, and consequences for the United States. It turns, finally, to the war’s costs and consequences for its Asian protagonists, ending with Vietnam’s assumption into the market-capitalist system whose frontiers in Southeast Asia the United States squandered blood and treasure to defend.

The Political Economy of the War

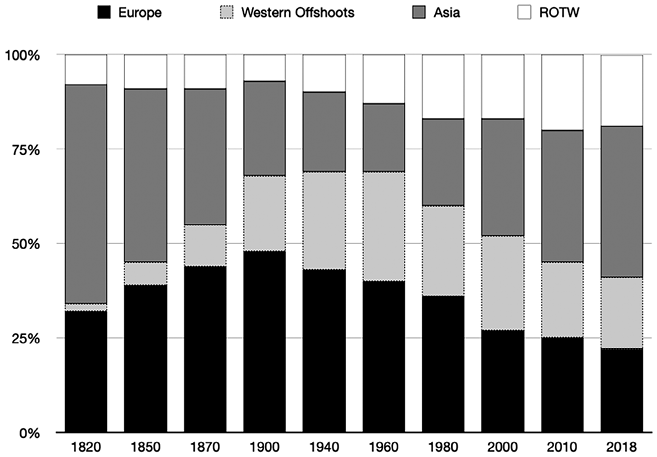

In one important respect, the global economy that Vietnam rejoined at the end of the twentieth century resembled the world economy of the precolonial era. Then, as now, East Asia was central. Figure 29.1 sketches the panorama. What accounted for Asia’s fleeting eclipse in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was of course the uneven diffusion of the Industrial Revolution. Fossil fuels and mechanical industry propelled the societies of the North Atlantic to a transient ascendancy. In 1960, Europe and its offshoots, including the United States, produced around 68 percent of the world’s output. This was the context in which the Vietnam War was fought: at the precise moment when the East–West developmental chasm was broadest.

Europeans at the dawn of the industrial era were familiar with Asia’s wealth: they had preyed on it for centuries. Since Vasco da Gama’s journey to the Indian Ocean in 1497–8, European mariners had improvised trading monopolies, created maritime protection rackets, and seized control of strategic ports, such as Malacca. But Europeans before the Industrial Revolution had not, for the most part, established colonies or territorial control over the interior hinterlands whose dense populations and artisanal production were the source of Asia’s wealth.Footnote 5

To grasp the difference the Industrial Revolution made, contemplate the changes in Anglo-Chinese relations over half a century. When the diplomat George McCartney undertook his famous mission to the court of the Qianlong Emperor in 1793, China remained impenetrable. Fifty years later, the world had changed. Steam-powered gunships enabled Great Britain to defeat China, in Chinese waters, in the First Opium War. Thereafter, the British wrested significant concessions, including Hong Kong, in the Treaty of Nanking of 1842. These gains gave Great Britain significant advantages over the other European powers, which strived after 1842 to extract from China concessions of their own.

Figure 29.1 The balance of global production, 1820–2018.

France under the Second Empire of Louis Napoleon exemplified the dynamics of colonial envy. Conscious of how far French wealth and power lagged behind Britain’s, Louis Napoleon sought to expand French influence into Mexico, North Africa, and Southeast Asia. Mexico proved a fleeting preoccupation: here, French ambition ran up against an ascendant rival with imperial designs of its own. But in Southeast Asia France encountered an empire in the throes of decomposition. For sure, the Vietnamese state that had consolidated power under Gia Long in the early nineteenth century still paid formal tribute to China. But the independence that Vietnam had already achieved showcased the fragmentation of a Chinese order in Southeast Asia – and opened opportunities for outsiders. France acted, establishing in 1867 the colonial foothold of French Cochinchina, the first in a series of French encroachments into Southeast Asia.

During the 1880s, French officials mashed their conquered territories into a colony, the Indochinese Union, that would be integrated into a capitalist–industrial system centered on Europe. To this end, France invested, and France extracted.Footnote 6 French firms built infrastructure, including canals, roads, and railroads, but such investments were intended to facilitate extraction, especially of agricultural commodities. Rice became a crucial export; between 1873 and 1920, the area devoted to its cultivation increased sixfold.Footnote 7 Over time, French firms learned to extract other commodities, including coal and rubber. Such extraction served a core–periphery logic, in which Southeast Asia’s wealth would be harnessed to support development elsewhere.

France was not the only colonial latecomer to covet Asian resources. Japan’s quest for regional empire in East Asia resulted from a breakdown of liberal globalization in the era of the Great Depression. As the global economy fragmented after 1929, the great powers sought to forge regional zones of economic control and exploitation. Japan’s extractive project focused first on Manchuria. But in 1937 Japan launched an audacious bid to conquer the rest of China. The early successes were startling, but Chinese forces steeled themselves for resistance, and Japan’s offensive ground to a halt. Frustrated, Japan turned toward Southeast Asia in a maritime thrust, which Japanese strategists hoped would secure access to raw materials such as rubber and oil.

The Asian war became a world war in December 1941 as the result of an audacious Japanese move. Calculating that their empire of extraction would be secure only so long as the US Navy could be held at bay, Japanese leaders launched an aerial assault on the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawai’i alongside invasions of the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), the Philippines, Burma, Thailand, and Malaya. Unfortunately for Japan, the US Navy survived Pearl Harbor with sufficient capital ships intact to launch a slow fight-back across the Pacific.

Victory came in 1945. Over the next five years, US decision-makers grappled with the geopolitical stakes of France’s efforts to retake Indochina from a communist-tinged resistance movement. In June 1950, the United States acted, dispatching the first planeloads of materiel to French colonial forces in Vietnam. Over the next four years, Washington assumed financial responsibility for France’s effort to secure the Associated States of Indochina, a neocolonial construction, against the Việt Minh. By 1952, the United States was funding about 40 percent of France’s military campaigns in Indochina; by 1954, the American share approached 80 percent.Footnote 8

How to explain the assumption of such burdens? US decision-makers grasped Indochina’s importance “as a source of raw materials” for the capitalist world, and they understood the region’s economic importance to Cold War allies.Footnote 9 And, yet, the choice for intervention did not spring from the kind of acquisitive logic that had animated French and Japanese colonialism. France clung to empire after 1945 because its leaders adjudged Indochina a source of wealth, the access to which would determine France’s standing among the great powers. Only after military defeat at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954 confirmed that empire’s burdens now outweighed its benefits did French leaders decide to cut their losses and dissolve their empire’s sunk costs. American embroilment in Southeast Asia followed a quite different logic. Confident in their own geopolitical primacy, American decision-makers opted for embroilment not because they sought to exploit Indochina’s material resources but because they presumed that global responsibility was the destiny of the greatest of the powers.

The year 1954 was a fateful one. Điện Biên Phủ exploded the strategy of Harry Truman’s administration for securing Vietnam through France. In the battle’s aftermath, President Dwight Eisenhower adopted an alternative approach: to contain communism through collaboration with Vietnamese nationalism. The approach aligned with broader US approaches to the Cold War, in which Washington sought to defeat communism through the cultivation of modernizing nation-states under American tutelage and protection. This was not a colonial strategy, at least not in the extractive sense of nineteenth-century colonialism, but its implications were hierarchical and hegemonic. To contain communism in Indochina and elsewhere, the United States would foster leagues of anticommunist states, situated in subordinate relationships to American power. To these clients, the United States would offer military security, development assistance, and the aspirational model of its own modernity.

To these ends, the United States supported Ngô Đình Diệm’s consolidation of power in South Vietnam with abundant resources. The Department of Agriculture provided food aid; the International Cooperation Administration, development capital; the Defense Department, military support and materiel. To monitor these flows, Washington dispatched agronomists, economists, engineers, and military advisors. Their mission was to build a state capable of exercising control within borders, a state that could function, like West Berlin, Taiwan, and South Korea, as a Cold War bulwark. Unfortunately for Washington, the foundations for this fortress state on the Cold War’s fluid frontiers were being laid in quicksand.

As elsewhere, the Cold War in Southeast Asia was more a social war than an interstate conflict, especially at the outset.Footnote 10 Communists and anticommunists alike waged brutal ideological war. The major difference was the sheer effectiveness of the communist campaign to undermine South Vietnam from within, a campaign that escalated sharply in 1959–60. The result was to transform South Vietnam from a bastion of containment into an area of struggle, into which both superpowers poured resources. US involvement was direct. Washington built South Vietnam while escalating a military crusade that spilled blood across Indochina. China and the Soviet Union opted for more indirect roles. Both aided the insurgency through North Vietnam, whose land border with China offered an easy conduit.

The flows of military and economic resources that resulted made South Vietnam the crucible of a cataclysmic form of globalization. Animated by fear and ambition, the superpowers channeled materiel from Michigan, Manchuria, and Magnitogorsk into South Vietnam, a territory smaller than the state of Oklahoma. The consequences for the Vietnamese people, and for other Indochinese peoples into whose lands the wars for South Vietnam spilled, were both predictable and near-apocalyptic. Whatever the underlying intentions, the impacts that the Cold War’s empires of dissemination produced were no more benign, and were in some ways even more atrocious, than those that nineteenth-century empires of colonial extraction had caused.

Vietnam and the Crisis of Pax Americana

The narrative of US intervention follows a familiar arc: escalation, frustration, retreat. President John F. Kennedy expanded the US military assistance mission to South Vietnam, but it was President Lyndon Johnson who took the most fateful steps: he intensified the air war against communist positions and supply lines; he launched the strategic bombing campaign against North Vietnam; he dispatched the first US ground troops in March 1965, then ratcheted force levels upward.

Unlike in the Korean War, the United States could not persuade its European allies to share the burdens of containment in Vietnam. Great Britain refused to dispatch even a symbolic force. France offered only declarative statements about peace that undermined the US war effort. Allies in the Asia–Pacific region proved more responsive. New Zealand, Taiwan, and the Philippines sent token forces, Australia and Thailand more substantial contributions. But it was South Korea, itself a Cold War frontier state, that made the greatest contributions. South Korea suffered heavy military casualties, losing more men than any US state except California. But South Korea also reaped significant benefits from its role in Vietnam. Along with Japan, which did not participate in the warfighting, South Korea would emerge, in the war’s aftermath, as one of the key economic beneficiaries of the Vietnam War.Footnote 11

Having paid limited attention to the war’s escalation, Americans began in 1967–8 to interrogate the costs and benefits. Hereafter, the arc of US involvement bent toward deescalation. From 1969, President Richard Nixon worked to “Vietnamize” the war, an approach that combined US troop withdrawals with increased military and financial assistance to South Vietnam. Nixon’s strategy aimed to substitute guns and dollars for blood, but neither the flows of military assistance he directed to Saigon nor the ruthless tactical escalations he initiated made South Vietnam secure. Instead, Congress confirmed that retreat really meant defeat when it acted during 1973 to cut off remaining funds for war operations in Indochina. Thereafter, the predicament of South Vietnam resembled that of the French fortress at Điện Biên Phủ in the early months of 1954: the frontier state stood alone, ringed by enemy forces and dependent on a thread of supplies that was insufficient to break the siege. And then, predictably, it fell.

The slow-motion denouement of America’s Vietnam War contrasted with the brutal volte-face that France had enacted in 1954–5. The Americans had persisted for two decades in their effort to secure South Vietnam, and then they withdrew, divided and defeated. But what had the effort cost them, and what would be its economic consequences?

The Vietnam War claimed its most basic toll in human lives. This cost is readily calculable, at least for the American side. The names of the 58,221 Americans who perished are inscribed in the granite of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. More detail can be found in the Pentagon’s Defense Casualty Analysis System.Footnote 12 This dataset tells us that the average US casualty was a man of approximately 23.1 years of age, most likely from California.

Parsing the statistics reveals an uneven age distribution. More than 5,500 Americans were over thirty when they died in Vietnam. The longevity of this cohort creates a statistical tail that obscures just how young the war’s typical American victim really was. Substitute a modal average for the mean, and the age of the representative fatality falls to just 20.44 years: the difference between a college sophomore and a college senior. Almost 11,500 American casualties were nineteen or younger. Nearly 12.5 percent were African American, compared to 11.1 percent of the US population.Footnote 13 Contrary to popular impression, nearly 70 percent of the Americans who perished were volunteers, not conscripts. Virtually all were men; the military casualties included just eight women, all military nurses.

Another hundred thousand soldiers, sailors, and airmen suffered severe disabilities. Here, calculation of the war’s costs becomes murkier. Expenses associated with medical care for wounded veterans vary depending on the nature of the injuries and the lifespan of the survivor. The costs of caring for wounded veterans, moreover, situate with the Veterans’ Administration, not the Department of Defense, and are thus disentangled from the costs of waging war.

Accounting for veteran care also requires judgment calls. Some 8.8 million Americans served in Vietnam; almost all became eligible for free healthcare from the Veterans’ Administration system because of their service. Should estimates of the war’s costs include this entitlement? Given the perplexities, perhaps it will suffice to say that caring for veterans remains a major public obligation: allocations to the Department of Veterans Affairs claimed 2.4 percent of the federal budget in the 1990s, 2.7 percent in the 2000s, and 4 percent in the 2010s.Footnote 14 (Compare this to the Department of Education, which received 2 percent in the 1990s, 2.6 percent in the 2000s, and 1.8 percent in the 2010s.) Even if the United States were to disengage from the world tomorrow, the costs of the nation’s twentieth-century wars would weigh upon the federal budget for decades.

Turn to other budgetary items, and calculation of the Vietnam War’s costs becomes even more vexing. Crudely, the expenditures the United States incurred in Vietnam can be divided into two categories: those associated with state-building and those associated with warfighting. Estimating the costs of state-building is relatively straightforward. Over two decades, economic assistance to South Vietnam flowed via three main channels. The first was the Commercial Import Program, which provided Saigon with dollars to purchase US-made goods. The second was the PL 480 or “Food for Peace” program. The third was Project Aid, a catchall that enveloped a multitude of initiatives, from infrastructural development to administrative reform. To these three channels, the economist Douglas Dacy has added a fourth, which was the “piaster support” that US agencies (and personnel) provided when they purchased the South Vietnamese currency at the official rate and thereby helped to sustain an overvalued exchange rate.Footnote 15

To these expenditures should be added the weapons, supplies, and military training the United States provided to South Vietnam. Military assistance surged during the Kennedy years and continued at high levels through the mid-1960s, even as the United States deployed its own armed forces. As Table 29.1 shows, military assistance reached its highest levels under Nixon, who hoped to offset US troop drawdowns with sharp increases in aid. Table 29.1 shows the pattern.

Table 29.1 US assistance to South Vietnam

| Economic Aid ($ mln) | Military Aid ($ mln) | Total US Aid ($ mln) | % of US GDP | % of South Vietnam GDP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955 | 322.4 | 322.4 | 0.08 | 35.43 | |

| 1956 | 210.0 | 176.5 | 386.5 | 0.09 | 39.44 |

| 1957 | 282.2 | 119.8 | 402.0 | 0.08 | 41.88 |

| 1958 | 189.0 | 79.3 | 268.3 | 0.06 | 26.30 |

| 1959 | 207.4 | 52.4 | 259.8 | 0.05 | 22.79 |

| 1960 | 181.8 | 72.7 | 254.5 | 0.05 | 21.75 |

| 1961 | 152.0 | 71.0 | 223.0 | 0.04 | 18.43 |

| 1962 | 156.0 | 237.2 | 393.2 | 0.07 | 32.77 |

| 1963 | 195.9 | 275.9 | 471.8 | 0.07 | 36.57 |

| 1964 | 230.6 | 190.9 | 421.5 | 0.06 | 30.99 |

| 1965 | 290.3 | 318.6 | 608.9 | 0.08 | 39.54 |

| 1966 | 793.9 | 686.2 | 1,480.1 | 0.18 | 90.80 |

| 1967 | 666.6 | 662.5 | 1,329.1 | 0.15 | 70.32 |

| 1968 | 651.1 | 1,243.4 | 1,894.5 | 0.20 | 98.67 |

| 1969 | 560.5 | 1,534.0 | 2,094.5 | 0.21 | 85.84 |

| 1970 | 655.4 | 1,577.3 | 2,232.7 | 0.21 | 90.03 |

| 1971 | 778.0 | 1,945.6 | 2,723.6 | 0.23 | 107.65 |

| 1972 | 587.7 | 2,602.6 | 3,190.3 | 0.25 | 110.39 |

| 1973 | 531.2 | 3,349.4 | 3,880.6 | 0.27 | 132.90 |

| 1974 | 657.4 | 941.9 | 1,599.3 | 0.10 | 45.96 |

| 1975 | 240.9 | 625.1 | 866.0 | 0.06 | N/A |

Table 29.1 prices US assistance in historical US dollars, but what was this assistance worth? How we answer may be a matter of perspective. Start by situating South Vietnam among the beneficiaries of US assistance worldwide. At the peak in the early 1970s, around one-third of the entire US foreign aid budget went to Saigon, an impressive total.Footnote 16 But situate that aid in relation to the overall US economy, and the sums transmitted appear unimpressive. Only in 1973 did aid to South Vietnam surpass 0.25 percent of US GDP. Under LBJ, annual aid flows averaged just 0.13 percent of GDP. Adopt a South Vietnamese perspective, though, and the economic umbilical cord stretching across the Pacific explodes in significance. Between 1955 and 1965, US assistance approached one-third of South Vietnam’s GDP. During the 1971–3 phase, the value of US assistance surpassed South Vietnam’s entire economic output. This radical asymmetry reminds us that South Vietnam was an economic vassal: a Cold War frontier state whose GDP, averaged over the 1955–75 phase, was about 1/475th that of the United States. An insignificant trickle from a US standpoint, the transpacific flows of resources that Washington sustained from 1955 through 1975 were South Vietnam’s lifeblood.

More significant for the United States were direct expenditures associated with warfighting operations. Calculating these costs is more challenging. The technical obstacles include the difficulties of disentangling the costs of the Vietnam War from the overall Pentagon budget; the challenges of accounting for hardware purchased before the war; the unpredictability of public obligations to military veterans in the aftermath of war; and the unavailability of budgetary data from the CIA, which played a sizable role in the US military effort.

Methodological choices also bear upon our sense of the war’s costs. Pentagon data provides alternative costings of US war expenditures: one based on the war’s “incremental costs,” the other on a “full cost basis.” The first set of figures derives total war expenditures from a counterfactual projection of what the Pentagon’s budget would have been without the war. The second tallies all warfighting expenses. Pentagon estimates put the war’s price tag around $111 billion (nominal) on an incremental cost basis and $140 billion on a full cost basis.

Convert the Pentagon estimates into 2020 dollars, and the digits surge. Even the low-end estimate ranges from $527 billion to $1.4 trillion, depending upon what method of historical price conversion is favored. (The high-end estimate may be the most appropriate: it bases the conversion on the expenditure’s share of GDP to calculate the “economy cost” to society.) These are big numbers, but for a yardstick compare the Vietnam War’s costs to those of the Apollo Project. NASA admitted spending $21 billion on the moonshot; others have estimated $30 billion.Footnote 17 Adopt the low-end estimates for both projects, and the Vietnam War cost the United States four times as much as the moon landing.

Thus far, our calculations have included only direct outlays. These are the most tangible expression of the war’s costs, but they are not the whole story. Comprehensive reckoning should include future budgetary costs: transfers to war veterans; extrabudgetary costs, such as the civilian earnings that soldiers and sailors forwent; and even the costs of macroeconomic setbacks associated with the war, such as recession or inflation.

Two book-length studies have attempted such comprehensive estimates. In one, the economist Robert Stevens put the war’s costs in the $882–925 billion range.Footnote 18 In the other, the economist Anthony Campagna proposes a more conservative $515 billion.Footnote 19 The lower-end estimate still yields startling conclusions. Convert Campagna’s estimate of the overall costs into 2020 prices on an economy-cost basis, and the United States spent around $6.55 trillion (2020) on the Vietnam War. This sum doubles Linda Bilmes and Joseph Stiglitz’s comprehensive estimate of the Iraq War’s costs.Footnote 20 Alternatively, the costs of the Vietnam War exceed the combined stock market capitalizations of Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon as of mid-2021. Such numbers confirm that the Vietnam War was a major fiscal undertaking, the macroeconomic implications of which warranted careful management.

Unfortunately, political leaders managed the war’s economic consequences carelessly. Responsibility attaches, once again, to LBJ and his closest advisors. Until the escalation of the war in 1965, the costs of US state-building efforts in South Vietnam were low enough to be inconsequential from a macroeconomic standpoint. The adverse economic effects began with the war’s Americanization in 1965.

To understand the war’s economic consequences, the context is vital. Unlike World War II, the escalation of the Vietnam War coincided with the apex phase in a long economic expansion, which the Democratic Party’s embrace of fiscal stimulus policies had bolstered. The zenith in this expansionary phase was the Revenue Act of 1964, a huge tax cut that aimed to put money back in pockets, expand aggregate demand, and promote economic growth. The law achieved all these purposes. Between 1964 and 1966, GDP growth averaged 6.3 percent per year, which made the mid-1960s the strongest three-year phase for the US economy since the Korean War. In 1966, the unemployment rate slipped below 4 percent.

Despite the general boom, the endurance of poverty amid plenty prompted new fiscal commitments in the mid-1960s: Johnson’s $1 billion War on Poverty, declared in 1964; the Medicare and Medicaid programs, enacted in 1965 and 1966; and a generous reform of the Social Security Act in 1967. These were worthy initiatives, befitting Johnson’s self-conception as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s political heir. But the difference was that LBJ did not pivot from nation-building at home to warfighting abroad, as FDR had done in the late 1930s; LBJ attempted to do both at the same time, which compounded the Vietnam War’s effects.

As the data in Table 29.2 indicates, federal spending on the war approached 3 percent of GDP in 1966, rose to 3.5 percent of GDP in 1967–8, and then receded in the early 1970s. By comparison with recent wars, these were not vast sums. During World War II, military spending had peaked at 37 percent of national GDP in 1944. During the Korean War, defense spending surged to almost 14 percent of GDP in 1952. During the Vietnam War, total US defense spending never surpassed 9.1 percent of GDP, of which barely a third was devoted to the war effort. Yet Vietnam War spending generated adverse economic effects that the Korean War had not because Vietnam coincided with a long secular expansion of the US economy.

Table 29.2 Vietnam War annual spending, 1964–1973

| US National Accounts | Vietnam War Expenditures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US GDP ($ mln) | Federal Spending ($ mln) | Federal Spending as % GDP | Federal Surplus / Deficit (% GDP) | State-Building | Warfighting | Total | Total (% GDP) | |

| 1964 | 629,200 | 118,400 | 18.8 | −0.3 | 421.50 | 0.10 | 421.60 | 0.07 |

| 1965 | 672,600 | 119,900 | 17.8 | 0.2 | 608.90 | 5,812.00 | 6,420.90 | 0.95 |

| 1966 | 739,000 | 134,300 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 1,480.10 | 20,133.00 | 21,613.10 | 2.92 |

| 1967 | 794,600 | 156,700 | 19.7 | −1.1 | 1,329.10 | 26,547.00 | 27,876.10 | 3.51 |

| 1968 | 849,400 | 174,400 | 20.5 | −1.4 | 1,894.50 | 28,805.00 | 30,699.50 | 3.61 |

| 1969 | 929,500 | 187,300 | 20.2 | 0.6 | 2,094.50 | 23,052.00 | 25,146.50 | 2.71 |

| 1970 | 990,200 | 198,700 | 20.1 | −0.1 | 2,232.70 | 14,719.00 | 16,951.70 | 1.71 |

| 1971 | 1,055,900 | 216,800 | 20.5 | −2.0 | 2,723.60 | 9,261.00 | 11,984.60 | 1.14 |

| 1972 | 1,153,100 | 237,100 | 20.6 | −1.7 | 3,190.30 | 7,500.00 | 10,690.30 | 0.93 |

| 1973 | 1,281,400 | 260,400 | 20.3 | −1.2 | 3,880.60 | 3,800.00 | 7,680.60 | 0.60 |

LBJ might have mitigated the consequences by seeking a tax hike to offset the war’s costs, much as President Truman had done during the Korean War. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara recommended that Johnson pursue a tax surcharge in July 1965; other advisors, including the economist Walter Heller, reiterated McNamara’s suggestion. But LBJ worried about how a tax hike might affect both the Great Society programs that he cherished and his party’s prospects in the 1966 midterms. He instead obfuscated, funding the war through supplemental appropriations.

McNamara, while he grasped the war’s real costs, played an infamous part in the Johnson administration’s fiscal subterfuge. The most notorious episode occurred in January 1966, when he presented to Congress a budgetary proposal for 1967 that predicated the Pentagon’s budget upon the dubious assumption that the Vietnam War would be over by June 30, 1967. This gambit enabled McNamara’s budget to meet (more or less) the president’s informal ceiling of $110 billion on US defense expenditures for the fiscal year. But the predictable consequence was a rapid return to Congress to pursue supplemental appropriations – and widening federal deficits in 1966 and 1967.

Specifying the economic effects of LBJ’s furtive escalation is a speculative exercise. The economist who has devoted the most careful attention to the question concludes that the war’s “ultimate economic consequences” will “never be known with any degree of precision.”Footnote 21 But even contemporary analysts believed that spending on the war effort, which approached 3 percent of GDP during 1966, contributed to a widening federal deficit, an overheating US economy, and surging price inflation. Increasingly tangible during 1966, these downside costs nudged the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary conditions. The Fed’s efforts ended up precipitating a dramatic credit crunch in late 1966 that interrupted, but did not end, the postwar boom. But the episode portended challenges ahead.

During 1967, the Fed eased interest rates, and LBJ opted to pursue a temporary tax surcharge. “The spurt of demand that followed the step-up of our Vietnam effort in mid-1965,” Johnson conceded, “simply exceeded the speed limits on the economy’s ability to adjust.”Footnote 22 Overdue, the president’s appeal for a tax hike did not win over fiscal hawks in Congress, who demanded spending cuts as a precondition for raising taxes. In Wilbur Mills, Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, the president found an implacable foe. Mills’s resistance forced Johnson to do what he had not previously done and redefine the Vietnam War as a solemn national obligation, in which all Americans should share. But LBJ would not accept cuts to his social programs, and a standoff with Mills persisted through 1967.

The conflict over war funding came to a head in the winter of 1967–8, as the costs of the Vietnam War weighed upon the US international balance of payments. A sterling crisis in November 1967 prefigured a wave of dollar sales in the winter of 1967–8. Investors swapped dollars for gold, gambling that the United States would be next to devalue. Committed to sustaining the dollar’s fixed exchange rate at $35 per gold ounce, LBJ doubled down on the prophylactic measures that he and his immediate predecessors had adopted to shore up the international balance of payments. New controls on overseas investments by US corporations were imposed, and overseas travel by US officials and even private citizens was restricted in a bid to stem the outflow of dollars.Footnote 23

The Tet Offensive at the end of January 1968 created new questions, including whether LBJ would send more troops to Vietnam. The uncertainty exploded the long-feared dollar crisis. In early March, the Treasury began to hemorrhage gold, as hordes of dollar-holders demanded conversion of paper dollars into gold. Rather than devalue the dollar, the Johnson administration opted to suspend gold–dollar conversions (except when requested by foreign central banks) and to accelerate preexisting plans to reform the international monetary system through the creation of an artificial reserve asset, the IMF-sponsored Special Drawing Rights. The crisis also proved a macroeconomic turning point. To bolster the dollar and curb inflation, the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates, which reached 8 percent at the year’s end. And Lyndon Johnson at last accepted Wilbur Mills’s position: to pay for the Vietnam War and to buttress the dollar, he would accept both a tax surcharge and cuts in federal spending.

The crises of early 1968 ended the long era of postwar growth and shattered what had in the 1960s become a working consensus within Washington around the desirability of fiscal stimulus. During 1968, macroeconomic policy turned toward retrenchment, a shift that Richard Nixon’s election confirmed. Vietnam was not the only cause of this economic reckoning, but the war’s costs and, more important, LBJ’s failure to plan for the war’s costs hastened the unraveling. Tragically, the war upended the grand ambition of LBJ’s Great Society and redirected resources toward a distant, misbegotten war. Martin Luther King, Jr., was right to lament the tradeoffs. “I knew,” King mulled, “that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in the rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube.”Footnote 24

Vietnam hastened the demise not only of progressive domestic priorities but also of an international monetary order centered on the dollar. Johnson’s turn toward retrenchment in 1968 bought time, and high interest rates attracted an influx of dollars from overseas that buoyed the balance of payments. But the crisis of the dollar-centered monetary order could not be forestalled forever. The Fed’s turn toward a more expansionary monetary policy in 1971 precipitated another major dollar crisis, in response to which President Nixon in August 1971 severed the last connection between the dollar and gold. Nixon’s tactical goal in 1971 was to secure a dollar devaluation, but his strategic purpose was to reverse what he saw as national decline.

The Vietnam War was not the cause of the relative decline that Nixon hoped to reverse. But Vietnam had exposed the hubris of Lyndon Johnson’s gambit that the United States was so rich that it could afford to wage a major war without enacting policies to offset the war’s costs. By adding to the deficits and the inflationary pressures that roiled the US economy in the late 1960s, the Vietnam War hastened the reckoning. And what the war ultimately exposed, perhaps, was the underlying unfitness of American political institutions for sustaining the burdens of empire that successive presidents had assumed in Vietnam.

While the Vietnam War never cost more than a small fraction of the nation’s GDP, the war never commanded the kind of political consensus that had enabled the United States to sustain a vigorous national mobilization in World War II. Tolerated so long as it was fought offstage, the Vietnam War divided Americans as soon as it began to exact meaningful costs. The rancor that followed exposed the unwillingness of American politicians to shoulder the burdens of singular responsibility in a prolonged global struggle with Soviet communism. With the Vietnam War’s twilight, an era of Cold War optimism, in which presidents had presumed their nation’s capacity to “bear any burden” on the world’s behalf, ended, and an era of limits began.

The War and the Resurgence of East Asia

What, though, of the war’s costs for its Vietnamese protagonists? While the paucity of data precludes the kind of accounting this chapter has attempted for the American side, we can nonetheless ponder the differences between the American and Vietnamese experiences of war.

Start with the death tolls. The imprecision of even the most careful estimates indicates the Vietnam War’s appalling costs. Various authorities have compiled numbers: from the US Senate and Defense Department, which have generated separate estimates; to the government of Vietnam, which released its figures only in 1995; to demographers who have attempted to deduce war deaths from pre- and postwar population data.Footnote 25 Taken as a whole, these exercises have affirmed the contemporary assumption that the war’s Vietnamese death toll is situated in the 2–3 million range. Of these, up to 1 million deaths may be counted as combatant fatalities on the communist side, with maybe a quarter of a million combatant fatalities on the South Vietnamese side. The balance can be measured in civilian lives, although the distinction between combatant and civilian is no easier to comprehend today than it was for US soldiers during the war.

Nor can the war’s economic impacts be estimated with much precision. The Defense Department’s Theater History of Operations Records (THOR) dataset specifies the sheer quantities of ordnance the United States dropped on Vietnam: more than 7.5 million tons of bombs, double the quantity the United States deployed worldwide during World War II.Footnote 26 But this data does not indicate the damage that US ordnance caused, nor the destruction inflicted by mortars, napalm, and small arms. Once again, the contrast between the clinical precision of the American data and the abject imprecision of the war’s deadly effects upon the people of Vietnam offers further evidence, as if any were needed, of the war’s terrible asymmetries.

Comparisons may be more illuminating. North Vietnam, which suffered the brunt of the US bombing, experienced aerial bombardment akin to what Germany and Japan suffered in 1944–5. South Vietnam experienced the ravages of countrywide insurgency and counterinsurgency warfare. Contrasting the American and Vietnamese experiences involves comparison between an offshore military effort that never consumed more than 4 percent of GDP with a conflict that approached the intensity of total war, for both Vietnamese protagonists.

South Vietnam and North Vietnam waged different wars, but the economic mobilizations that the two Vietnamese states undertook reveal certain structural similarities. Both Vietnams were developmental states. Both strived to overcome the legacies of colonial exploitation, including through land reform. Both were Cold War frontier states that depended upon inflows of assistance from their superpower patrons.

Start with South Vietnam, a state whose creation resulted from the hope that US-sponsored economic and political development might forestall communism’s advance. Development aid was the principal form of US assistance to South Vietnam in the early years, and South Vietnam depended on it. Between 1955 and 1960, US assistance comprised more than 31 percent of South Vietnam’s GDP. Over the course of the 1960s, an expanding share of US aid flowed to military purposes. By the late 1960s, the annual value of US assistance was approaching 100 percent of South Vietnam’s GDP, the preponderance of which flowed toward the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), not the civilian economy. What all this meant, the economist Douglas Dacy surmises, is that South Vietnam “was foremost an aid economy,” dependent on US assistance, which functioned as “the glue used to hold the country together.”Footnote 27

Ironically, the vast scale of US assistance, coupled with the deleterious effects of the war, asphyxiated the economic growth that US policymakers hoped to cultivate. South Vietnam’s agricultural economy illustrates the point. Developed under French colonial rule, South Vietnam’s agricultural sector was at the war’s outset configured to produce regular surpluses for the world market. In 1963, South Vietnam had exported 323,000 metric tons of rice, which made the country the world’s fourth-largest exporter. But the war exerted a heavy toll on production, and what filled the gap was American aid. In 1967, South Vietnam imported more than 777,000 tons of rice.Footnote 28 The reversal showcases not only the war’s devastating economic effects but also how South Vietnam’s relationship to the world economy shifted in the era of the Vietnam War. Formerly an arena of extraction from which the French pulled commodities, South Vietnam became under US tutelage a receptacle for American economic inputs, an inversion of transnational flows that produced its own deleterious consequences.

The politics did not help. Perhaps a tight authoritarian grip or a robust democratic mandate would have empowered the enactment of effective economic reforms, but Ngô Đình Diệm commanded neither. Saigon thus lacked the political tools necessary to transform an unequal agrarian economy into a modern and productive industrial society. South Vietnam’s limited forays into land reform reveal the constraints. Concerned not to alienate landowners, Diệm at first reversed the land reforms that the Việt Minh had enacted during 1953–4, restoring titles to landlords. He then introduced a modest land reform of his own that left a sizable portion of South Vietnam’s peasants landless, to the consternation of American advisors who understood the catalytic role that land reforms had played in Japan’s and Taiwan’s postwar booms. But the preservation of political stability required the conciliation of social elites, and Diệm lacked the capacity, and perhaps the will, to ride roughshod over powerful domestic opponents.

Saigon’s preoccupation with the preservation of social peace outlived Diệm and led, over the course of the 1960s, to the diversion of significant US aid toward consumer subsidies. Cheaper goods gratified consumers, but subsidies squandered resources that might have sustained longer-range development goals. The regime’s fledgling legitimacy thus precluded, once again, the hard choices necessary to prioritize strategic purposes. Saigon, it turned out, could neither coerce nor persuade its citizens to sacrifice for a more prosperous future. The boldest reforms, ironically, came late. From 1970, the government of Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu enacted a land reform initiative that transferred holdings to almost 1 million landless peasants. Unfortunately for South Vietnam, the window of opportunity for boldness was already closing.

North Vietnam was a different story. Similar in size and population, the crucial distinction between the two Vietnamese states was the dominance in the North of a disciplined Communist Party whose cadres subscribed to a rigid ideology of modernization. For sure, Hanoi did not achieve socialism’s mooted breakthrough to modernity during the war decades. When the Americans ceased bombing, North Vietnam remained pitifully poor, much as it had been at the war’s beginning. Rather, what the party–state’s rigid grip provided was an authoritative basis for war mobilization that contrasted with the experiences of both South Vietnam and the United States.

The contrasting aptitude of the two Vietnams for economic coercion was evident well before Hanoi opted to channel assistance to the South’s communists. Land reform illustrates the differences: where Saigon dithered, Hanoi acted. Initiated before the eviction of the French, land reform efforts in the North intensified after Geneva. During 1956, the Communist Party completed an ambitious program that stripped land titles from wealthy peasants and redistributed land to tillers. Enacted by teams of party cadres, the campaign was violent and coercive; the death toll, historians estimate, numbered in the thousands.Footnote 29 Next came the campaign for agricultural collectivization, which strived to consolidate private holdings into state-owned enterprises. These two policy thrusts revealed the strengths and the weaknesses of communist methods. Land reform broadened individual property ownership, incentivized work, and boosted productivity: rice production in the North doubled between 1954 and 1959. Collectivization halted the progress: Vietnamese peasants were less eager to work for the state than for themselves; agricultural productivity plateaued after its implementation.Footnote 30

After land reform and collectivization, North Vietnam confronted a strategic dilemma: what should the goal of its economic development be? Moderates wanted to consolidate the party’s agricultural achievements through the pursuit of an industrial development strategy that would transform North Vietnam into an exemplary socialist economy. Militants, who grouped around Lê Duẩn, prioritized national reunification, which is to say war against South Vietnam.Footnote 31 The dilemma resembled the old Stalinist/Trotskyite debate: having seized power, should Marxist-Leninists spread their revolution or strive to create a beacon of socialist progress? The difference was that North Vietnam after Geneva was half of a divided society, not a continental empire. This reality made the offensive irresistible, and the Politburo opted at the 3rd Congress of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) to wage war in the South.

What resulted was, in some ways, a synthesis of moderate and militant approaches. Conscious of the need to balance factions within the VCP, Hồ Chí Minh argued for socialist construction in the North to sustain the war in the South. Development would be harnessed for warfighting purposes. The whole project depended upon infusions of economic and military effort from the Soviet Union and China, whose grants, loans, and materiel sustained Hanoi’s war. Grasping North Vietnam’s dependence on its communist patrons, Hồ Chí Minh strived to balance between Beijing and Moscow. Hồ Chí Minh’s faltering health empowered the militant faction, but Lê Duẩn continued balancing between Beijing and Moscow to extract resources from both. The intensification of the US war, including the unleashing of Operation Rolling Thunder in 1965, only sharpened North Vietnam’s dependence on its Soviet and Chinese patrons. By 1965–7, North Vietnam depended on external assistance for as much as 60 percent of its annual budget.Footnote 32 This made the North a Cold War welfare state not so different from the South.

The crucial difference was the unity of purpose the VCP was able to impose. Whereas Saigon squandered US aid on consumer subsidies, Hanoi was able to compress civilian consumption and impress civilians into military service. The differences showed. Much as the Russian and Chinese civil wars had done, the Vietnam War affirmed the utility of disciplined and ideological party cadres during times of severe trial. War communism, for all its cruelties, showed itself to be an effective system of social control and economic mobilization, and not for the first time in the twentieth century.

However, war communism proved less adept as a framework for peacetime development. Vietnam’s post-1945 struggle for postcolonial succession came to an overdue end in early 1975 when North Vietnam invaded and conquered the South, completing the coercive reintegration that the United States had fought to prevent. After 1975, the Communist Party exerted itself to impose upon South Vietnam the systems of control refined in the North during the war. Southerners, especially those of Chinese descent, suffered. And, yet, the conquered South’s relative prosperity contrasted with the austere poverty of the North, providing a window into capitalist modernity that would encourage economic reformers within the VCP.

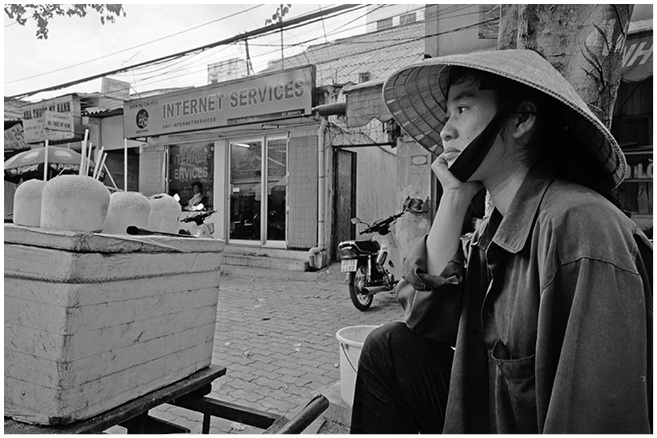

Figure 29.2 A Vietnamese woman sells coconuts and waits for business outside an internet center in Hồ Chí Minh City (November 19, 2000).

Lê Duẩn’s death in 1986 created an opportunity, which reformers seized. Nguyễn Vӑn Linh, who had led the Communist Party in the South during the war, now emerged as the architect of a new economic strategy, known as đổi mới (renovation). Increasingly, a Southern perspective guided national strategy. Nguyễn Vӑn Linh’s reform agenda loosened controls on foreign direct investment, abandoned price controls in agriculture, and liberalized Vietnam’s financial sector. By the end of the 1980s, Vietnam was no longer a socialist economy in the Marxist-Leninist sense; rather, the choice for reform remade Vietnam’s economic order and its relationship to the larger global economy. Hanoi’s pragmatic choice benefited the Vietnamese people, whose per capita income quadrupled, in real terms, between 1990 and 2020.Footnote 33

Conclusion

Hanoi’s choice for globalization remade Vietnam’s relations with the larger world and with the United States, which normalized relations with Vietnam in the mid-1990s. Trade boomed: twenty years later, the United States was Vietnam’s largest export market, absorbing more Vietnamese exports than China and Japan combined.Footnote 34 By the 2010s, even the geopolitical relationship between Vietnam and the United States was tightening, a consequence, to some degree, of the fears that China engendered in both Hanoi and Washington. The result, half a century after the war, was a bilateral relationship more balanced and reciprocal than the one that had existed between Washington and Saigon, which had engaged only as patron and client.

But if the Vietnam War came to appear, as the decades passed, an awful detour in a longer, and increasingly productive, US engagement with Vietnam, the passage of time would not vindicate those American leaders who had escalated the war in the 1960s so much as it called into question their judgment, their patience, and their sense of history. Had the self-avowed champions of the “Free World” been more confident in the prospects of their own system, perhaps less blood would have been shed in Vietnam. In this sense, the long view and the rapprochement it envelops offer no exculpation; the irony merely compounds the tragedy.