“A strict representation of facts [Tatsachen],” Leopold Ranke held, “be it ever so narrow and unpoetical, is beyond doubt, the first law.”Footnote 1 Why are historians supposed to restrict themselves to an impartial engagement with the mundane world? In this article I begin to suggest a genealogy of this notion of historiography that takes us to the beginnings of the modern historical discipline, namely Ranke's dictum that it was history's office, and thus the historian's task, to “say how it actually was” (bloß sagen, wie es eigentlich gewesen).Footnote 2 In the historical discipline, this understanding of historical work was a matter of what later would be referred to as historical objectivity, a word Ranke himself was hesitant to use.Footnote 3 When he spelled it out, objectivity, to him, equaled impartiality: “objectivity equals impartiality.”Footnote 4

In Ranke's case, although he was not alone in this, objectivity involved a stance towards not only this epistemic virtue of impartial objectivity, but also the afterlife of religious notions. In this respect I follow some lines of inquiry suggested by Wolfgang Hardtwig's seminal article on history's religion.Footnote 5 Furthermore, I show how historical work was a practice as well as a notion that reflected what historians did and how they did it. Ranke's understanding of universal history did not allow the historian to take a privileged place of judgment. What mattered to him was to develop a particular rationality of history; that is, to present facts in a coherent narrative and find a novel language of history. Religion played an important role in the emergence of this Rankean rationality of history. The fragments from the work on his two unfinished book projects—a study of Martin Luther he was pursuing in 1817 and a theory of history that was supposed to follow his universal history but never materialized because of his death—help to understand how, for Ranke, a particular religious experience provided a sense of orientation within his spontaneous philosophy of history. Ranke found orientation in both everyday experience and signs of God which can be understood within a philosophy of symbolic forms.Footnote 6 They provided orientation not because they were self-evident but because they referred to a spontaneous philosophy that deferred to a vague notion of the unity of history. Ultimate questions—such as theodicy, teleology, or contingency—were not history's concern for Ranke. But they entered the historical narrative between the lines and informed the thinking about history in everyday practice. As his son recalled, Ranke would recognize signs of God everywhere—be it a lost book that resurfaced or the failed revolution of 1848. This genealogy of Ranke's rationality of history thus poses a problem: how to reconcile the strict representation of historical facts with the thinking of a historian who saw signs of God everywhere.

World citizen of Berlin

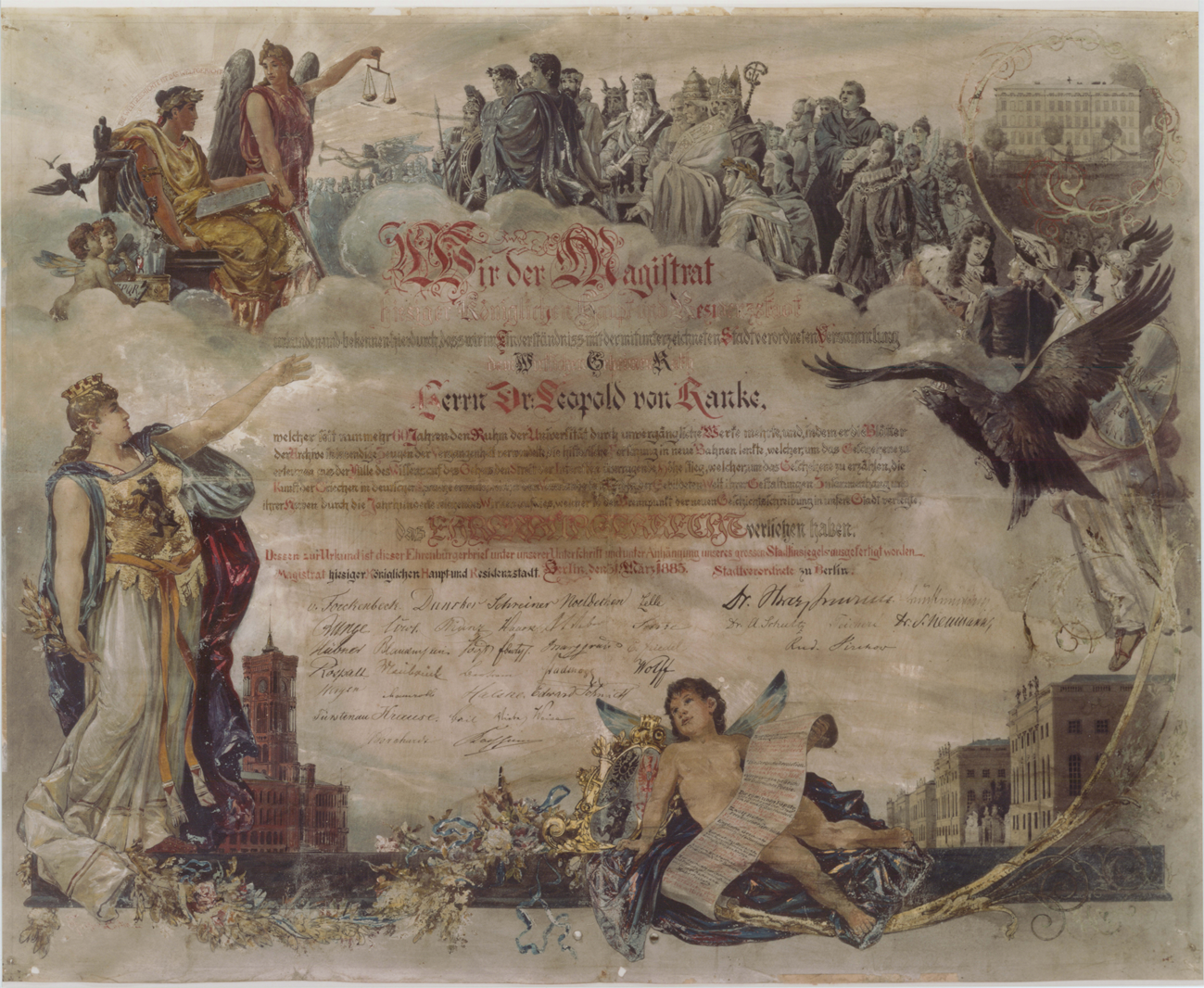

In early August 1885, the lord mayor visited Leopold Ranke to present him with a vellum document declaring the historian an honorary citizen of Berlin (see Fig. 1). The vellum was carried by three men up the stairs to Ranke's apartment. He was “astonished” by the gift.

Fig. 1. The vellum document Ranke received on the occasion of his honorary citizenship of Berlin (1885) was illuminated by Ernst Albert Fischer-Cörlin, one of the many painters of the historicist genre. Today it is part of the Ranke library acquired by Syracuse University in 1888. Credit: certificate, “Seiner Hochwohlgeboren Herrn Wirklichen Geheimrath Leopold von Ranke in Berlin,” Leopold von Ranke Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries, original acquisition series, Box 1, bookplate no. 26727. For the history of the Ranke collection see N.N., “Von Ranke's Library: A Prize Secured for the Syracuse University,” New York Times, 11 March 1888, 2. Edward Muir, The Leopold von Ranke Manuscript Collection of Syracuse University: The Complete Catalogue (Syracuse, 1983); Muir, “Leopold von Ranke, His Library, and the Shaping of Historical Evidence,” The Courier 22/1 (1987), 3–10; Jeremy C. Jackson, “Leopold von Ranke and the Von Ranke Library,” The Courier 9/4 and 10/1 (1972), 38–55; Siegfried Baur, “Franz Leopold Ranke, the Ranke Library at Syracuse and the Open Future of Scientific History,” The Courier 33 (2001), 4–43.

What does the vellum document show? Ranke's notes in his diary tell us, “The personification [Ranke used the German Bild—image] of History holds the scale of justice in her hand in front of her”—in fact in the upper left-hand corner of the vellum there are two personifications, Clio and Justice, that constitute History in Ranke's understanding—“then appear the historical heroes and great dignitaries of the world in their magnificence, from Caesar to Napoleon. To do them justice can only mean to recognize their very nature [sie in ihrem Wesen erkennen].”Footnote 7 Ranke was intrigued enough by this honor to interrupt his work for two hours and engage in a conversation with the lord mayor.

The document recognized Ranke for his contributions to the historical discipline and for making Berlin “a center of modern historiography simply by doing his silent work.”Footnote 8 Ranke was indeed immersed in his work: he had recently grown a beard, and, on the occasion of his ninetieth birthday, had fashioned himself as a seer and prophet of the unknown land of historiography.Footnote 9 This carefully illuminated letter offers an interesting perspective on the historian and his work. It reflects the common conception at that time regarding the historian's relation to objectivity and impartiality. Yet it runs against Ranke's understanding of history's task: “History has had assigned to it the office of judging the past and of instructing the present for the benefit of the future ages. To such high offices the present work does not presume: it seeks only to say how it actually was.”Footnote 10

The German of the inscription on the vellum mimics Latin syntax and would have sounded outmoded even by late nineteenth-century standards. The document stresses that Ranke directed historical research towards new horizons, “by transforming the pages in the archives into living witnesses of the past.”Footnote 11 He is praised for “renewing the Greek art of historiography in the German language” in such a way as to demonstrate the importance of the deeds and actions of the heroes throughout the centuries.Footnote 12 In order to “distinguish significant occurrences from the plethora of knowledge, he had to rise to the level of the seer on sublime height above the struggle of interests.”Footnote 13 Ranke, the inscription concludes, made Berlin the center of nineteenth-century historiography.

As our gaze is further drawn into the background of the illumination, we see into the Greek origins of Western culture. Trumpets provide the sound for the dramatic eclipse in the left upper corner. There, between a seated Clio and the upright Justice, with sword and scale, an arched inscription—resembling a halo hovering over Clio's head—reads, “DIE WELTGESCHICHTE IST DAS WELTGERICHT” (“World History Is the Last Judgment”). Like Lady Justice, Clio, in the depiction at hand, was not blindfolded. Her role, however, was to observe, not to judge. The public sense of Ranke's historiography as it became visible in the illuminated vellum was thus based on a misconception of Ranke's thinking: as a historian he did not believe in an instance that would allow for a position of ultimate judgment. Yet he was convinced of the existence of a realm of Fortleben (“living on”); that is to say, Ranke believed in neither historical afterlife nor the resurrection of the past, but in the living on of phenomena of the past in the present. This transcendental space was a necessary prerequisite for transforming great individuals from the past into historical figures larger than life. The contingent historical process itself would decide who was deemed worthy to enter the procession of historical figures. Even though this process was following a certain trajectory, it was not oriented towards a determinate end. In similar fashion, past occurrences created an undercurrent that directed the flow of events one could not escape.

Although Ranke would only sit down to write a history of the world six years before his death, his entire oeuvre, from his earliest notes about Luther to the editing work on his Sämmtliche Werke (Complete Works), attests to the emergence of an understanding of history as a universal world-historical process. However, the historian's perspective could never rise to the divine observer position of an impartial view: world history, as he maintained, was only known by God. Nonetheless, Ranke aspired to an impartial position that would allow him to see everything from nowhere. As a historian he found himself in a position to know parts of the historical process while believing that these parts could only be integrated into a universal knowledge of world history by reference to God. This tense combination of sacred and secular—foundational for Ranke's understanding of both history and the underlying world-historical process—was already present at the beginning, in Ranke's earliest readings of Luther.

From the shifting memories of becoming a historian to finding orientation in a spontaneous philosophy of history

Already during his lifetime Ranke's name was invoked as that of a “celestial deity” by the members of an academic discipline that assembled around a cult of positivist historiography, or what later would be called the Ranke school of critical history.Footnote 14 Indeed, it is striking how many elements of what, to this day, are considered good practice and normal science within the historical discipline seem indebted to Ranke's example, from his “archival turn” to the aesthetics of a scientific historical narrative.Footnote 15 Yet, on closer examination, it shows that many of these innovations were already common as anonymous practices well before Ranke rose to the rank of the doyen and master of historiography. As scholars have shown, what came to be considered Ranke's original contribution to historical method he had in fact learned from his teachers in Classics and theology, in particular Barthold Georg Niebuhr and Gottfried Hermann. Less familiar is that Ranke learned the critique of historical sources from his friend the historian Gustav Adolf Stenzel. All three practiced a craft as it had been performed for generations. It might be too strong to say that Ranke stole from his friend, but he certainly appropriated what Stenzel had taught him and did not shy from taking intellectual credit for it.Footnote 16 After all, there is a great deal to be said for being the last to invent a method.

The young Ranke did not yet understand himself to be a historian, however. He was trained as a classicist. The first historian he studied was Thucydides, the subject of his dissertation.Footnote 17 The first German-language book by a historian that left an impression on him was his teacher Barthold Georg Niebuhr's (1776–1831) Roman History, published in three volumes from 1811 to 1832. As Ranke shifted from reading authors from the classical tradition to engaging with more recent writers, most importantly Luther, his research interest moved from Classics to history. With this in mind, Ranke's becoming a historian presents as the story of a conversion, from a true believer in God to a historian who believed in the truth of history.

Later in life, he would give diverging versions of his intellectual formation: in his autobiographical dictations from 1863, in his reflections on his student years on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of receiving his doctorate in 1868, and again in 1885 on his ninetieth birthday. However, his early writings—as presented in the 1973 edition of his unpublished notes by Walther Peter Fuchs—provide us with a quite different account than any of Ranke's later, shifting memories of how he became a historian.

The editorial history of these early writings has contributed to the confusion, not least because the editors used Ranke's late recollections as guides for the organization of the materials. Already Paul Joachimsen's assistant, Ernst Bock, started to rearrange materials as part of the 1920s Akademie project of editing Ranke's unpublished writings. Later, Walter Peter Fuchs, yet again, presented the materials against the organization of the Akademie edition.Footnote 18 In his 1973 edition of the same papers Fuchs regrouped all surviving Luther materialsFootnote 19—following Ranke's autobiographical recollections—against their original organization, rearranging the original papers and ironically violating the archival principle of provenance. Even after Siegfried Baur's meticulous attempts at a reconstruction of their original order, too much context information has been lost to tell how they were actually organized.

What we do know, at this point, is that Fuchs and the other editors separated the notes on Luther from their original context, and gave a sequence of fragmentary writings the coherence of a common theme, namely Luther. In fact, the resulting image of Ranke provided both by the author and by his posthumous editors emphasized the impact of Luther and disconnected the notes on Luther from their original context. Yet they originally were individual entries in the very same notebooks in which one can find notes on Kant, Fichte, and other authors and their texts. While the young Ranke may well have tinkered with the idea of writing a book on Luther, his notes can hardly be understood as fragments of a book manuscript. They have the character of excerpts, with little to suggest the authorship of Ranke. As a consequence, the so-called “Luther fragment,” which portrays Ranke's notes as pieces of an unfinished book, only came into existence with the posthumous editorial work of Fuchs and his fellow editors. Scholarship today agrees that a manuscript on Luther from Ranke's hand never existed.Footnote 20 Furthermore, it remains unclear to what extent the project was conceived by Ranke at the time as a book rather than just an early infatuation with the idea of biography. After all, the scattered notes are in line with Ranke's self-understanding during the early stages of his career: “We are yet all fragmentists. Me in particular.”Footnote 21

Ranke's editors’ disagreement as to how to organize his papers, and consequently his legacy, leaves us with an interesting problem: where can we situate the moments of transformation that illuminate the relation between Ranke's religious belief and his decision to become a historian? Even though the young Ranke read other authors important for his intellectual development, the engagement with Luther's writings left a significant mark on him and his writing of history. Based on this, I will maintain that Ranke's work on Luther shaped his thinking as a historian by providing an intellectual religious experience that provided orientation within his “spontaneous philosophy” of history.Footnote 22 This spontaneous philosophy emerges from, and implicitly reflects on, practice and can even extend to and thus shape everyday conduct and religious views. However, life and work do not simply map onto each other. Rather, for the intellectual historian, life only becomes relevant insofar as it facilitates thinking and leaves a mark on the intellectual work. I thus prefer to pay attention to the ways in which intellectual activity invariably draws on everyday experience. According to Louis Althusser's theoretical practice, spontaneous philosophy was “the representation that scientists have of their own practice, and of their relationship to their own practice.”Footnote 23 This sense that they have of their own activities remains implicit, since “what seems to happen before their eyes happens, in reality, behind their back,” and thus manifests unconsciously.Footnote 24

In the case under discussion, the spontaneous philosophy not only reflects historiographical practice but also mobilizes religious notions. Accordingly, I understand religious experience as a means of orientation within a spontaneous philosophy of history that emerges from practice. Ranke, like so many other historians after him, was not in need of an elaborate philosophy of history. Although religious experiences did not provide a systematic philosophy of history, they nonetheless organized deep-seated sensibilities about the historical process. In other words, a certain form of religious experience is essential to the emergent rationality of Ranke's work as a historian.

Ranke's vision of his projected book on Luther was formative in his process of becoming a historian. As he would later remember, “In the year of 1817 I actually made an attempt at compiling a comprehensive history of Luther in his own language.”Footnote 25 In this, he followed Luther's own advice for reading his work: “The benefit in it would be that people could learn and grasp the histories and stories as I was able to grasp the word of our dear Lord,” Ranke wrote, copying Luther's words to his notebook.Footnote 26 Ultimately, Ranke was “searching for an older linguistic form that was lying rooted even deeper in the nation. I grasped Luther, at first to just learn German from him and to acquire the fundamentals of the modern written German; but at the same time, I was carried away by the enormous amount of materials and by the historical figure itself.”Footnote 27 Here Ranke used the German Erscheinung to refer to the historical figure, a term that can be translated as “appearance,” “apparition,” “phenomenon,” or “figure.” This is a peculiar word choice that defers the Kantian notion of the historical sign and refers to the Hegelian reinterpretation of Kant's historical sign: with Hegel and Ranke the appearances themselves can be read as signs.Footnote 28 Ranke's early fragmentary writings, I will argue, were an attempt at thinking about Luther as a historical figure, an apparition. Ranke's notes on Luther attest to the formation of an intellectual device that would shape the historian's work and lead to a reformation of the historical discipline.

From reading Luther to Ranke's historical figures

The twenty-two-year-old Ranke found himself disappointed with the popular writings published on the occasion of the Luther anniversary of 1817. “The weak popular accounts that surfaced caused me to study the original documents in an attempt at a biography.”Footnote 29 Instead of reading historians, he decided to study original sources. As a student, Ranke had first engaged with the writings of Luther—at that point as a good Protestant. We know that the young Ranke owned a copy of a ten-volume Altenburg edition of Luther's writings.Footnote 30 Occasionally, he also consulted the more recent Jena and Halle editions as well as editions of Luther's letters and colloquia. He also studied Immanuel Niethammer's edition and seems to have appreciated his presentation of Luther's work. In his preface to Luther's exegetical writings, Niethammer claimed, “In this time, we have to think, more than ever, of Luther as an author to do justice to him and to judge him based on his own writings, which without doubt bear witness against the groundless accusations, the malevolent allegations and the thoughtless criticism against him.”Footnote 31 This was advice the young Ranke was glad to follow, advice that also echoed Luther's stance on the problem: he too argued that the man and his deeds would show in the text and this was all there was to know. Ranke's turn to the original text was clearly in line with Niethammer's position. Reading Luther's writings, he mostly ignored the scholarship. More important was the formative effect that direct exposure to the original has on the reader. “You studied all of Luther,” wrote Ranke's brother Heinrich in 1820, “and believed.”Footnote 32

The Reformation, wrote Ranke's critic Lord Acton, “is the age to which [Ranke's] whole character is suited and his style of writing perfectly corresponds to a part of the character of these times.”Footnote 33 This observation is important and needs to be spelled out: Ranke's interest in Luther and the Reformation period, indeed, became part of his habitus. First, for Ranke, being a historian meant donning the robes of a priest, not a judge. Second, the Rankean language of history was structured in analogy to Luther's writing and intellectual practice, especially his work of translating the Bible into German for an audience no longer in need of priestly exegesis.

In order to arrive at a better understanding of Ranke's language of history, then, I turn to Luther's reading and translation of the biblical text. Rejecting the medieval quatuor sensus scripturae—i.e. the fourfold method—Luther instead insisted on a literal reading that became the prerequisite of rendering the Bible in German prose. Ranke would follow Luther in dismissing allegoric, moral or anagogic exegesis. Historical figures, he agreed with Luther, manifested themselves in writing. As Ranke puts it in one of his excerpts referring to Luther's Table Talk: “Since I was a monk, I was a master of spiritual interpretation, read everything as allegory: later, however, when I, while reading the epistle on the Romans, had begun to know Christ, I saw that with allegories and spiritual interpretations nothing could be nothing.”Footnote 34 There is no doubt that Ranke's fascination with Luther was driven by religious interest. However, unlike his brother Heinrich—a theologian and pastor—Ranke did not pursue theological reflections. He sought a specifically historical perspective on Luther. His attempt at reading Luther as historical figure, however, was informed by the argumentative figures he found in Luther. A biographical account of Luther's work, Ranke claimed, would only need to pay attention to his life insofar as it became manifest in his writings; whatever did not leave a trace in the text was irrelevant to his intellectual biography.

In his notes on Luther, Ranke stated that he does not have to distinguish between his subject's life and teaching: “we touch nothing but his life since he lives in his teaching and his teaching lives within him so that both coincide.”Footnote 35 Ranke did without lengthy summaries of Luther's dogmatic opinions and refrained from historical contextualization. Instead, he was aiming at the “core of his life” in order to “see what he wanted, was striving for, searched for and also found.”Footnote 36 It was there that Ranke hoped to find his “fundamental opinion, his secret.”Footnote 37 Luther's secret, as Ranke called it, was to be found “in his life, where one is confronted with the innermost of Scripture: and from there it leads out to life; where he then undividedly is, what he is … for evermore does he live on in the idea, a pure, most blessed human being.”Footnote 38 Not only Scripture but also Luther's writings were “calling from the past” as a historically given.Footnote 39

Luther, for Ranke, was one of the “few heroes” who had grasped the truth in “word and deed,” those being nothing but appearances that could be read as symptoms of something “invisible.”Footnote 40 What remained invisible yet manifested itself in the historical process was precisely divine spirit and God's invisible hand. “Word is an appearance, deed is an appearance, they would be irrelevant if there was not something showing through them,” namely spirit.Footnote 41 However, spirit does not exist in a pure form; “each appearance follows its own principle.”Footnote 42 In the individual figure, like Luther himself, an “ethical principle” was at work that realized its potential within the unfolding historical process.Footnote 43 The Rankean historical category of the “real-spiritual” merged the contingent and idiosyncratic logic of the appearance with absolute spirit. This made it possible to “reconstruct the internal from the external,” i.e. the real was shaped by the spiritual. Accordingly, past life—as both real and spiritual in as far as it lived on—figured in the text and thus transformed in a particular mode of historical existence, namely what Ranke called Fortleben (“living on”).Footnote 44

In other words, in Ranke's reading of Luther, work and life merged into the “historical figure.” This notion resembles what has been referred to as a personnage conceptuel, a conceptual figure or character.Footnote 45 Such conceptual figures are semi-fictional, in much the way that Ranke spoke of the “real-spiritual” character of historical appearances. What was real in the past could only become historical in the present through its spiritual quality of living on. Ranke's writing of history relied on translating what he called (real) past individualities into a (spiritual) rhetorical and argumentative device. In Ranke, the positivist reference to the past (the “wie es eigentlich gewesen”) figures both in the language of the historian and in his sources, in particular through the individual characters of great men. They do the work of philosophical concepts. “The fabric of individual actions can only be explained by the mind-sets [Gemüther] of the individuals,” Ranke maintained, “from the influence of those close to each other who have an effect on each other, from the formation of the spirit of the time in each individual; and therefore, the psychological development of the characters of history is as necessary as the development of concepts in philosophy.”Footnote 46

Along these lines, Ranke's historical figures took on the function that concepts played in Hegel's philosophical world history. For Hegel, the concept embodied the difference between things. True philosophy was to understand the very nature of opposites and differences, which had to be understood in their dialectic unity. Since the concept was the realization of this movement, the historical process for Hegel was plastic, but not elastic.Footnote 47 Historical time was thus irreversible and therefore the individualities could not return to their original form. In that spirit, Ranke, like so many of his nineteenth-century colleagues, also exercised the art of biography.Footnote 48 If the historicist obsession with biography is viewed this way, then historical work on the lives of great men turns out to be a necessary exercise in shaping the new conceptual language of historiography. Ranke's attempt at avoiding philosophical speculation forced him into this process of abstraction from historical materials to a language of history that could translate from the past to a general public in the present. Just as Protestants after Luther could read the biblical text individually, readers of Ranke's historical writings could engage with the past and its Fortleben (living on) in the present.

Translating between past and present

Requiring materials from the past in order to craft figures, Ranke turned to the archives.Footnote 49 Ranke's archival trips lasted for weeks and months, and he did much besides visit the reading rooms. On his first archival voyage, as is well known, he described himself as a Captain Cook of historical scholarship, who discovered princesses in the archives.Footnote 50 Less familiar is how he liked to visit Vienna's St Stephen's Cathedral on his extended walks through the city. In a letter from his time there he reflects on his day's work as a historian both in the archives and beyond. Attending the Catholic service in the cathedral one evening, he reported, made him see his work as a historian as “religious service” (Gottesdienst). We need to be careful not to read too much into this. Ranke was particularly apt to characterize his work in religious terms when writing to his pastor brother, and their correspondence has been, at times, too uncritically used to explore Ranke's religious views. Whatever Ranke's views of God might have been, however, he was certainly a believer in historical truth.

It is important to note that Ranke only turned to the archives after his engagement with Luther, indeed well after authoring his first book. As his early engagement with Luther's writings demonstrates, Ranke's fascination with historical sources preceded his turn towards the archives. As a student he had been intrigued by the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott and the atmosphere that their language conveyed. In conversation with the translator of his first book, Ranke said as follows:

Great as is the respect and veneration in which I hold Sir Walter Scott, I cannot help regretting that he was not more available for the purposes of a historian than he is. If fiction must be built upon facts, facts should never be contorted to meet the ends of the novelist. What valuable lessons were not to be drawn from facts to which the great English novelist had the key; yet, by reason of the fault to which I have referred, I have been unable to illustrate many of my assertions by reference to him.Footnote 51

When Ranke found out that these stories were fiction, not history, he made his way to the sources. Soon he would prefer texts from the past to any received account, let alone historical fiction. This was also true for his interest Luther's life. “He was reading sources and nothing but sources. It is absolutely erroneous to search for models that his presentation would have followed.”Footnote 52 Perhaps this is an exaggeration, but nonetheless Ranke dedicated a full year of his life to the study of Luther's writings, making careful excerpts from what he considered historical sources. These excerpts and notes are evidence of the historian's fascination with Luther and his time. How can we read them in order that they might speak to the problem of history's religion more broadly?

To begin with, reading Luther prompted an interest in the modern German language that ran against the early nineteenth-century aesthetic preference for Goethe. At first sight, this seems to have little to do with the afterlife of religion in Ranke's historiography. Yet it will become clear that it is relevant. Reading, commenting, and rephrasing, Ranke the trained classicist used Luther's texts to leave Greek behind and come to terms with German as a language of historiography. What is equally evident is Ranke's fascination with Luther's language. In a note Ranke paraphrases Luther to describe his own situation as aspiring intellectual in search for his characteristic way of writing: “I do not have a particular German of my own, but I use the common German language.”Footnote 53 Especially evident is Ranke's admiration for Luther's use of German, his talent for introducing German neologisms and phrases. Like Luther, Ranke hoped to find nothing less than a novel language to speak about the past.

Most of Ranke's notes on Luther are full of arresting connections without clear references, spontaneous thoughts and ad hoc paraphrases and approximate translations. He took notice of Luther's understanding of his translation from Hebrew, for example: “Who wants to speak German, must avoid Hebrew syntax but he grasps the sense and thus can think! … When he now finally has the German words … so he should let go the Hebrew and speak out freely their sense.”Footnote 54 Following Luther's example, Ranke did not read word-for-word, nor was his attention tied to the literal sense of the material. Rather, he believed in immediate understanding. Language to him was transparent rather than opaque. He based his spontaneous intuitions and interpretations both on a hermeneutic universalism—after all, we are all God's children—and on the fact that he considered himself the equal of the historical figures about whom he spoke.

Ranke thus understood Luther's contribution as a particular form of translation. The work of translating Scripture followed two trajectories: (a) it was an attempt at rendering the biblical text in the German language in order to make it accessible to the community of Protestants; (b) in turn, the German translation served a particular function: it was supposed to suspend the institutional framework and put the believer into immediate contact with the Word. Everyone should be able to read (or at least understand while listening to) Holy Scripture. This experience was in turn supposed to inform individual religious development, altering both the church's function and the priest's position. The promise of Luther, in Ranke's view, was immediacy: no more intermediaries between the written word and the believer, a direct experience of divine presence.

This relation between text and reader became a model for Ranke's historiography. He too believed in the powers of historical sources. The writing of history should serve as a translation between past and present; the work of translation should provide the reader with access to what actually happened. This is why Ranke made it a habit to add original sources, so-called analects, to most of his publications. They were supposed to expose the reader to the language from the past. The reader was invited to share the experience of covering the distance to language from long ago in order to get a deeper understanding of the language of the past, i.e. history.

In this way too Ranke finally imagined his audience—admittedly a future projection since at this stage he had not yet published a single line. This audience was no longer the Republic of Letters. He did not address the intellectual community of scholarship. He did not see himself as a historian among historians but instead as one figure of greatness in the Olympus of world history. He gained recognition as the founding father of the modern historical discipline, but in his eyes this understated his importance. By the end of his career, when looking at the procession of world-historical figures in the illumination of the vellum in his honor, he understood himself in proximity to those rulers of the world and pictured himself, after his death, in conversation with the one great mind he considered his equal: Plato.

Very much like Luther translating the biblical text into German, Ranke did not read historical sources as holy texts or with philological accuracy. His engagement with the past through language was meant to produce a peculiar anachronic effect and historical affect, i.e. a particular sense of the past. As mentioned, Ranke preferred reading the language of sources. Operating simultaneously in different registers, he aimed at more than writing history. His ultimate goal was to suspend the emphatic author position—to extinguish himself, as he once put it, and let things speak for themselves. In other words, he wanted to efface the historian in order to enable his readers to get a sense of the past that resembled religious experience. The audience should be able to engage with the past through the medium of writing, like the Lutheran community was to experience God through the biblical text—without unnecessary exegesis or commentary. Ranke therefore refrained from introducing analytic terminology while carefully crafting argumentative and narrative figures from the materials. The language of his writing of history meant to convey an instantaneous sense of the past in the present. This explains his affirmation that the medium of an absolute metaphor for history was Scripture.

In conclusion, when young Ranke set out in search of his voice as an author, he found both a language of history and an audience, namely all educated Germans. While at the beginning of the nineteenth century these were relatively few, by 1860 literacy campaigns had reached a turning point. By the end of his life, almost every German citizen had been taught to read. Ranke could thus see himself at the center of a discursive network that potentially allowed him to speak to the everyman. Granted not everyone was interested in his writings, yet Ranke himself was interested in reaching out to the entire nation. Indeed, when, in 1881, he started to publish the volumes of his universal history, he made it a habit to present each volume, year after year, as a gift to the German nation on Christmas Day.

World history as Last Judgment?

As Ranke knew, Luther had been waiting for the Last Judgement. In his table talk Luther articulates “down-to-earth apocalyptic expectations” and asks for “a delay and prophesizes and longs for the arrival of the Last Judgment,” as Reinhart Koselleck put it.Footnote 55 He too was concerned about questions of the Last Judgment, yet in historiographical and theoretical perspective. With the transformation of the notion of history towards the end of the eighteenth century, he argued, the issue of the morality of history was transferred to history itself and was introduced to the historical process, an argument that Hans Blumenberg reiterated from a different perspective.Footnote 56 The notion of history-as-process in German implies the double meaning of process and trial. Once history was thought of as the judging instance, the individual historian no longer occupied the office of the judge. Weltgericht designated both secular jurisdiction and divine judgment over the mundane world, better known in English as “Last Judgment.”

By the end of the eighteenth century, world history had turned into a site of universalist judgment about bygone occurrences and past deeds. For some, it had become the ultimate judgment: “World history is the Last Judgment,” as Schiller put it in his poem Resignation: A Phantasy, first published in 1786. In its original—before it appeared as a proverb on Ranke's vellum—the poem questions the eschatological understanding according to which God is the mover of world history, presiding over a permanent judgment of human actions. Schiller's poem establishes a first-person speaker who finds himself on the “dark bridge” of eternity at the end of his life. He is hoping to be rewarded for all the things he renounced as a youth. The answer “a genius” gives to his question about the payoff for his privation and self-denial takes him by surprise: there are two flowers, “hope and joy.” One has to choose. It is an impossible choice between religious belief and enjoyment. Life has to be lived in this world, not postponed and supplemented as hope in a reward in the afterlife.

With the end of religious certainty about what happens after death, the modern subject became caught up in the contingencies of a mundane existence. By the late eighteenth century, a multilayered discourse about the finitude of the human existence and the end of life had emerged. The specter of suspended animation appeared in different, often unexpected, places. Physicians studied the vita reducta, writers started to tell stories about suspended animation, and the figure of the vampire began its literary career.Footnote 57 The anxiety about being buried alive tormented historians too, most famously Ranke's French colleague and acquaintance Jules Michelet, who was obsessed with the apparent death of those close to him.Footnote 58 For both Ranke and Michelet, death became a concern of their historiographical reflections. When death became mundane, the afterlife did not disappear—rather, it lived on, albeit in a different language. Ranke preferred to speak of Fortleben (living on) in both his spontaneous theory of history and his private life. In his historiographical writings all sorts of historical figures live on and have an effect on the present understanding of the past. After the death of his brother Heinrich Ranke, he wrote in a letter to his niece, “My brother will, of course, not only live on on the other side but will also live on eternally in this world. The present and future generations will find delight in his memory.”Footnote 59

What remains?

Was it the cunning of reason or a trick of nature that Ranke died before he could realize his plan to complete his life's work with a philosophy of history? According to his brother Ernst, Ranke wanted to outline a theory of history after the completion of his universal history. In this unrealized project Ranke had been hoping to deliver a systematic reflection on the guiding ideas of the world-historical process. The essay was meant to transcend the particularities of Ranke's multivolume World History and finally provide his audience with a concise theory of history in Rankean terms.

In his Last Things before the Last, Siegfried Kracauer claimed that history “belongs to an intermediary area” between a scientific approach and a metaphysical obsession with last things.Footnote 60 His suggestion was to “establish the intermediary area of history as an area in its own right.”Footnote 61 I believe that efforts to define this intermediary area date much further back. Kracauer's claim is merely a highly original afterthought about a moment in the formation of the modern historical discipline; however, one cannot but agree that the writing of history, indeed, used to be an attempt at “provisional insight into the last things before the last.”Footnote 62

Ranke's spontaneous philosophy of history was based on religious experience and often expressed in theological terms. Ranke called his historiographical work a “service to God” and his students and colleagues emphasized the “religious mission” he was pursuing as a historian. Furthermore, he made it very clear that the historian should not assume the office of a judge. According to Lutheran belief, on Judgment Day the dead will be resurrected, and their bodies and souls reunited. The good and righteous will enter into an eternal state of heavenly glory, while the bodies of the damned will remain in everlasting torment and shame. With this final resurrection, all human beings of all nations will assemble before God, and Christ will distinguish between the righteous and the wicked. Ranke the historian did not believe in resurrection. He insisted on the living on of historical individualities. Death may turn living bodies into corpses, but spirits lived on. No matter whether or not Ranke the believer might hope for Judgment Day, Ranke the historian rejected the notion that world history was the Last Judgment. History was supposed to refrain from any judgment.

This stance left the historian in a particular subject position: musing over ultimate questions could be suspended, and individual methodological decisions were delegated to a disciplinary framework. The historian thus found himself at a transitional stage between past and present. This required great effort in the translation of the language of the past to the historiographical discourse of the present, but that seemed no longer to matter—at least to Ranke, who was blind to such philosophical concerns.

The young Ranke's skepticism concerning the dichotomy of philosophical and historical explanation was echoed in the late Ranke's commitment to the historical science: “This way we come to understand the historical pathways also as the task of philosophy. If philosophy were what it is supposed to be; if the concept of History were entirely clear and perfect, then they would completely converge. With philosophical spirit the historical discipline would fulfil its office.”Footnote 63 In an ideal world, each philosopher would be a historian in the same way every historian would be a philosopher.

How could he know and, more importantly, how could he “say how it actually was”? Ranke's knowledge about the past was based on reading original sources. The almost blind Ranke revised the language of his most famous dictum, in fact, to “show” instead of to “say”—while “God's finger” disappeared throughout the 1874 revised version of his first book and the name of God was mostly avoided and rephrased. To refrain from any judgment and to focus the historian's task on showing as it actually happened was both an epistemological and an aesthetic choice. To borrow the words Ranke used when receiving his honorary Berlin citizenship, “the historian does not need to belong to a particular confession; he believes in truth.”Footnote 64 In his later, i.e. scientific, understanding of history, God was no longer considered the movens of the historical process but only surfaced as a phenomenon of culture. For Ranke, the historian, this God remained external to the historical process.

In consequence, the sources, for Ranke, conveyed a more reliable testimony and provided a language of the past that appealed to the historian's sense of elegance. Engaging with sources, Ranke believed, had the power to inform and transform the reader, in the sense of the German Bildung as education and subject formation. The structural homology between the formation of individual subjects (or institutions, for that matter) and the historical process can be perceived with the model of Bildung-as-development. Indeed, in this perspective, their capacity for Bildung allowed individuals, be they human like Ranke or institutional like the nation-state, to realize their historical potential and thereby partake in the liberating forces of history. This, in turn, meant the exclusion of anyone, or anything, not free to participate in the state as the most advanced form of organization. Ranke's language of history was thus organized around those historical figures that, as individualities, took part in the “fundamental concept of the human species of history,”Footnote 65 as Droysen had it, and thus existed and lived on in historical time.

According to Ranke, universal hermeneutic understanding was possible because the world was pervaded by spirit and thus creates an intelligible universe of “real-spiritual” individualities caught up in a process of development. That the historian shared this fate with the historical figures from the past was the fundamental prerequisite to mutual understanding. That he considered all peoples equidistant from God did not, of course, imply that everyone would be included in the way that everyone could be rescued on Judgment Day. Historical existence was a mode reserved for members of the peoples with history, and within that civilized world to those who manifested individual greatness. After all, historical perspective was also a matter of scale. In that sense, Ranke's understanding of world history was anything but universal, or, to put it differently, his understanding of world history was exclusive. For him, the world-historical process was a struggle of what he called the “great powers” and great men. Although he did not deny that lesser individualities had existed in the past, he did deny that they had historical existence. They did not live on in the cultural memory of the civilized world. In the Rankean world of history, they did not live on and so it was as though they had never seen the light of the day.

The historical figures Ranke crafted from materials from the past, however, did live on. They took on a symbolic and intellectual form that allowed them to populate the historical imagination.Footnote 66 These figurative abstractions from what Ranke liked to call “past life” would serve as foundational theoretical notions in the early phase of the modern historical discipline, and, I believe, keep the potential of a theoretical challenge to this day.