Introduction

This paper extends our understanding of gendered rural ageing by examining the diverse reasons why some mid-life women in rural Ireland want to work in older age. Whilst existing social gerontology literature deals well with the manifest (Jahoda, Reference Jahoda1981) financial implications of work and pensions, and negative consequences of the extended working life for women (Ni Leime et al., Reference Ni Leime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017), it has less to say around the latent (Jahoda, Reference Jahoda1981) functions of work for mid-life rural women, a sector that is highly heterogeneous, dynamic and deserving of exploration.

The world's population is ageing (Eurostat, Reference Eurostat2019), particularly so in rural areas (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Winterton, Walsh, Skinner, Winterton and Walsh2021), of which women comprise a high proportion. Furthermore, there are ever-increasing numbers of women participating in European Union labour markets (European Union, 2017), especially at mid-life (Ní Léime and Ogg, Reference Ní Léime and Ogg2019), and this is also the case in Ireland where mid-life women are working beyond the traditional base of 65 years in order to reach a revised pension age of 66, and ultimately, 68 years in 2028 (Ní Léime and Street, Reference Ní Léime and Street2019).

Mid-life is still relatively under-researched despite its critical position (Elder, Reference Elder1998; Lachman et al., Reference Lachman, Teshale and Agrigoroaei2015) as a unique window to old age. Defined in this study as 45–65 years of age, mid-life is a time of review, reflection and action (Biggs, Reference Biggs1999), something which is increasingly influencing some government policies, e.g. that of the United Kingdom (UK) (HM Government, Department for Work and Pensions, nd). From a lifecourse perspective, as adopted in this study, mid-life is the most likely stage in which women assess their lives to date and take decisions that may impact the quality of their future old age (Dittmann-Kohli and Jopp, Reference Dittmann-Kohli, Jopp, Bond, Peace, Dittmann-Kohli and Westerhof2007; Wiggs, Reference Wiggs2010; Lachman et al., Reference Lachman, Teshale and Agrigoroaei2015). Crucial mid-lifecourse transitions such as divorce, widowhood, redundancy and retirement from work, particularly within the context of a recessionary economy as experienced by Ireland from the period of 2008 to its current post-crisis state (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2018), may significantly influence the quality of the ageing process.

Research location

Employment opportunities in rural regions such as Connemara generally do not attract the diversity of work to be found in urban cities. Employment opportunities tend to be more limited, seasonal, casual or even precarious (Standing, Reference Standing2011). Typical employment for older women in Connemara is reflected in the jobs held down by the seven participants cited in this paper, and also amongst the additional participants of the larger study. Of the participants cited in this paper, one was unemployed, two worked in hospitality, two in administration, one in health care and one was self-employed. Other forms of employment found within the larger study included domestic work, organic farming and teaching. Most participants of this study worked full-time, and only one or two reported their work as casual in nature. Whilst retail is another common form of employment in Connemara, none from this study worked in that sector.

Rural Ireland missed out on the types of economic investment enjoyed by cities, particularly Dublin, the capital, and experienced little or no inward investment, even during the ‘Celtic Tiger’ boom years, spanning the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s (McAleese, Reference McAleese2000; FitzGerald, Reference FitzGerald2007), a period of strong economic growth. In addition, many mid-life women in Connemara have become the main income earners, a legacy of high male unemployment resulting from Ireland's most recent recession, beginning 2008, which impacted the construction industry particularly hard; economically, many parts of rural Ireland have never fully recovered. A legacy of economic rural neglect, such as that found in regions like Connemara impacts all age groups, but older women, who comprise a high proportion of rural Ireland, may be disproportionately impacted.

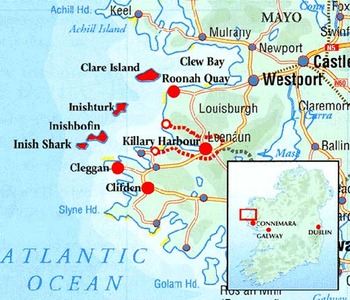

The region of Connemara in the West of Ireland was chosen as the research area for a number of reasons, including ease of access (Figure 1). Being in close proximity to Galway City, population 80,000 persons, some 80 kilometres (km) away, Connemara comprises 38,500 persons (Central Statistics Office (CSO), 2016) spread over 1,800 km2, giving it a low population density of almost 17 per km2. Around 5,500 mid-life women, aged 45–65, live in Connemara. Clifden town, the ‘capital’ of Connemara, has a population of just over 2,000 persons. Connemara is considered to be geographically rural in terms of population size and density; this article, however, examines rural from a social representation model as place with attached meanings (Halfacree, Reference Halfacree1995; Mahon, Reference Mahon2007) as this best accommodates participants’ own narrative on rural.

Figure 1. Map of Ireland and the Connemara region.

Literature review

Gendered nature of work

Paid employment is critically linked to the wellbeing of both genders, something that job losses in the UK resulting from the current global pandemic has highlighted (Centre for Ageing Better, 2020b). However, the concept of work has been found to be strongly gendered across the lifecourse due to divergence in employment histories, career interruptions, nature of occupations, levels of earnings and savings, and retirement circumstances, all of which contribute to older women's higher risk of poverty (Hooyman and Kiyak, Reference Hooyman and Kiyak2011; Ni Leime et al., Reference Léime Á and Street2017). The ‘typical’ male career (pre-COVID-19 pandemic) is defined and uninterrupted, usually lasting 40 years. The ‘typical’ female career, usually lasting just 34 years (Miley, Reference Miley2020), may be broken on account of domestic work and caring duties (Ní Léime and Street, Reference Léime Á and Street2017). Whilst the availability and nature of work can be problematic for men and women at mid-life, almost 70 per cent of part-time workers in Ireland are female and are likely to be paid at lower rates than those in full-time work, which further hinders savings and pension contributions (Ní Léime and Street, Reference Léime Á and Street2017). Those widowed, divorced, separated or acting as lone parent may encounter additional disadvantage from the possible lost support of a second income (Arber and Ginn, Reference Arber and Ginn2004) and from the difficulties of combining work with raising children on one's own.

Why women work

Despite the financial disadvantage of low work rates and pension contributions, women continue to work; however, the general increase in employment of older rural women may not necessarily equate with increased economic security (Duvvury et al., Reference Duvvury, Ní Léime, Watson, Skinner, Winterton and Walsh2021). To understand the non-monetary reasons why women want to work, we turn our attention to Jahoda's (Reference Jahoda1981) latent deprivation model of employment. Although neither gender- nor age-specific, Jahoda argues that work provides more than just monetary income or access to pensions. Specifically, Jahoda describes five latent functions of work that augment the manifest one of earning income, functions that help to sustain good physical and mental wellbeing (Paul and Batinic, Reference Paul and Batinic2009; Stiglbauer and Batinic, Reference Stiglbauer and Batinic2012). Although originally developed as a psychological framework on unemployment, Jahoda's model may be more widely utilised. Jahoda argues that employment provides more access to latent functions than are to be found in any other category, including unemployment and retirement. Furthermore, she asserts that employment's latent functions are actually more important to mental health than its manifest function of income. These latent functions of work include: time structure, collective purpose, social contact, social status and activity. Unpacking these and other latent functions provides a clearer understanding of what work has to offer older rural women, such as a sense of structured purpose that competes with the often perceived emptiness of retirement. Whilst work may produce its own stresses around time management and work–life balance, its absence may produce an even greater imbalance. Feelings of being useful and needed are linked to the latent function of collective purpose. Even within low-paid, low-skilled employment, the feeling of being a part of something bigger than oneself offers some purpose to life. Social contacts outside the family unit can provide a platform to increased self-esteem and self-worth gained from external judgement and rational appraisal. Social status resulting from the value system one inhabits is essential to the construction of self-identity, and active, rather than passive engagement with society has been shown to be essential to wellbeing (Paul and Batinic, Reference Paul and Batinic2009). Thus, work of all types is capable of offering a coterie of cognitive, social and psychological safeguards that may support health and longevity (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2002; Newton et al., Reference Newton, Chauhan, Spirling and Stewart2018).

In Ireland, literature posits that rural women work for both pecuniary and non-financial reasons (McNerney and Gillmor, Reference McNerney and Gillmor2005). Work allows women to contribute to under-resourced rural economies, offers some financial independence, and through increased connectivity may reduce the risk of social isolation and possible social exclusion from essential resources (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea and Scharf2020). Work can offer women in particular an alternative identity (Biggs, Reference Biggs1999; Berkman, Reference Berkman2014) to that of wife or mother, and many women feel more valued, competent and appreciated for their role within the workplace than for their unpaid work of child rearing and domestic duties within the home (Herbert, Reference Herbert2017).

Jahoda's (Reference Jahoda1981) model of employment cites latent and manifest features. Its manifest function relates directly to financial gain, but argues that this alone is insufficient to produce wellbeing. Globally, older women are increasingly engaged in the workforce. In Ireland, as in many developed societies, changing demographics show an increase in the numbers of women who have never married, have divorced or who are childless. ‘Blended’ multi-generational families and single parents (Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado, Reference Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado2018) have also increased in numbers. Many such women will both have to and want to work to support both themselves and dependants. Such socio-economically disadvantaged women as lone parents (Society of St Vincent de Paul, 2019), carers, those with a disability, the unemployed, the under-employed and the single may be the least likely to have accumulated sufficient financial income or pension in later life. Although this manifest outcome of work may be a driver of the extended working life, a fuller understanding of gendered rural employment cannot be gained without examining the desire to work and the multiple latent functions that work provides: structure, purpose, increased work-related and social networks, the creation of an alternative personal identity, additional skills-sets, and increased confidence and self-esteem.

The increasing global trend away from permanent, secure work towards casual, temporary, precarious work (Standing, Reference Standing2011) may also be the experience of older women in rural areas such as Connemara. Self-employment may be considered precarious (Standing, Reference Standing2014), but may still meet the financial and non-financial needs of some older women in rural Ireland. The self-employment rate for women in Ireland currently stands at 7.1 per cent (https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-lfs/labourforcesurveyquarter22021/tables). Self-employed women in Ireland comprise less than one-third of their male counterparts (CSO, 2016: https://data.cso.ie/table/EB001. (CSO, 2016). For those who do choose self-employment, the attractions at mid-life include flexibility and a new work identity (Tomlinson and Colgan, Reference Tomlinson and Colgan2014). Some older rural women choose self-employment in response to a lack of other types of work, or to achieve control over their work arrangements and domestic commitments. Although sometimes volatile work with irregular income, self-employment may suit the needs of certain types of workers, enabling, for example, artists to work in their own specialist field (Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, McGrath, OLaoire and Collins2018). However, temporal commitments associated with self-employment may lead to a diminished work–life balance for women with dependants (McLellan and Uys, Reference McLellan and Uys2009). Some research shows that self-employment that is chosen voluntarily tends to enhance wellbeing and quality of life, whereas that which is taken up to escape unemployment does not (Binder and Coad, Reference Binder and Coad2016). Although casual types of employment may be considered unreliable, these may also be viewed positively by some older workers seeking lifestyle flexibility, particularly those who are already financially secure (Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Crawford, Loretto, Phillipson, Robinson, Shepherd, Vickerstaff and Weyman2019). Precarious or ‘non-standard employment’ (Niesel et al., Reference Niesel, Buys, Nili and Millerin press) for rural women around retirement age could allow the freedom to work at a long-held passion or interest, even if such work does not sustain healthy financial outcomes.

Extended working life and retirement

The manifest (Jahoda, Reference Jahoda1981) consequence of employment is income, but decisions around employment and retirement are influenced by multiple socio-economic factors, including personal health, family dynamics and social welfare supports (Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Corna, Price and Karen2018; Ní Léime et al., Reference Ní Léime, Ogg, Rašticová, Street, Krekula, Bédiová and Madero-Cabib2020). Women's fractured employment histories contribute to gendered pay inequality: Ireland's pay gap currently stands at 14.4 per cent (Miley, Reference Miley2020). However, such inequity only partly drives the decision to extend the working life.

Mid-life women nearing retirement age may find it difficult to envisage a post-work phase of life or may actively fear retirement (Kojola and Moen, Reference Kojola and Moen2016; Hayley et al., Reference Hayley, Price and Buffel2020). Work can help to combat perceived societal and institutional ageism, and even perceived cognitive decline (Berkman, Reference Berkman2014). For some, retirement may mean the end of employment and the beginning of a new role in society; for others, it means the start of an old age that requires a new identity to replace their professional one (Price, Reference Price2000). Self-identity is socio-cultural context-dependent, and in contrast to other identities such as gender, race, ethnicity or nationality, changes with age over the lifecourse. In the absence of work, people may feel marginalised, and older people in particular may feel non-productive and burdensome in societies framed by ‘active ageing’ norms (Foster, Reference Foster2018). The void that opens up once work disappears may be filled with temporal dread and an old-age identity (Manor, Reference Manor2017) of emptiness.

Retirement may mean for some a release from stressful or unsatisfying work; but it may also be viewed as an unwelcome intrusion into a valued part of one's life (Sarabia-Cobo et al., Reference Sarabia-Cobo, Pérez, Hermosilla and De Lorena2020). Mid-life women may wish to be seen as ‘productive’ and thus ‘ageless’ (Timonen, Reference Timonen2016). Being able and appearing able to continue working helps to deflect the economic double jeopardy of sexism and ageism or ‘middle-ageism’: a master narrative of decline that prepares individuals to expect their own economic decline, and to scapegoat ‘ageing’ when their work services are dispensed with or denied access (Gullette, Reference Gullette1997). Gullette argues that whilst women at mid-life may not be considered old, they may still be deemed too old to work and thus unproductive. Social ageing bias of what is deemed ‘normal’ helps to create negative perceptions in which older female workers may be considered less efficient and more expensive to retain (Privalko et al., Reference Privalko, Russell and Maitre2019). Such negative perceptions are at odds with the views of some older female workers who want to work into older age. This is supported by studies that show older workers to have better customer service skills, and greater empathy and work ethic than their younger counterparts (Edge et al., Reference Edge, Coffey, Cook and Weinbergin press). Negative stereotyping in the workplace may be addressed to some degree by employment law, but a large body of research shows that legislation does not in itself eradicate cultures of discrimination and ageism (Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Firzly, Zhang and Luszczynska2020). Older workers are routinely portrayed as being more resistant to change, especially in information technologies, and less productive than younger workers (Dixon, Reference Dixon2020: chap. 4). Characteristics including empathy and loyalty, sometimes referred to as ‘soft skills’, may be valued by older workers but not by younger management, and cause older workers to be overlooked at recruitment, training and promotional stages. Whilst such workplace inequities affect both genders, older women may also have to contend with sexism, which doubly disadvantages them (Sontag, Reference Sontag1972; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Grant, Meadows and Cook2007). Sexism and ageism, whether clearly identified or perceived, may prevent some older female workers from fulfilling their desire to keep working, depriving them of an important work identity (Berkman, Reference Berkman2014) and society of a valuable resource. However, despite obstacles, others persevere in the face of the workplace ageism (Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Crawford, Loretto, Phillipson, Robinson, Shepherd, Vickerstaff and Weyman2019).

Working beyond retirement is not without challenges, but just as older women need to achieve work–life balance during their working years (Antai et al., Reference Antai, Oke, Braithwaite and Anthony2015), they are also aware that later in life there is a need to attend to ‘life-balance’ between committed and discretionary time in order to maintain wellbeing (Principi et al., Reference Principi, Santini, Socci, Smeaton, Cahill, Vegeris and Barnes2018). Nonetheless, the many latent benefits accrued from employment may be more than sufficient to redress any such imbalance.

Methods

Drawing on an arguably under-used theoretical framework from organisational psychology, Jahoda's (Reference Jahoda1981) latent deprivation model of unemployment, this paper focuses on the latent or non-financial benefits of paid employment by inter-connecting it with gender, rural, age and empirical data from mid-life (45–65 years of age) women in the rural Connemara region of Ireland. Data were gathered from the employed, self-employed and unemployed. Of the 25 participants utilised in the original wider study on ageing, the narrative offered during interview by seven are selected for use in this paper as pertinent illustrations of the critical latent benefits from paid employment. All data were collected and analysed solely by the author. The relationship between this selected group of seven participants and the remaining 18 showed both similarity and divergence. None of the other working participants did so solely for financial benefits. Of the entire study's participants, all reported latent benefits as well as financial benefits from working, although these reasons differed in width and depth. In the larger study, the two participants with intellectual disabilities, for example, were engaged in a work environment solely for latent benefits. Both had, with the help of their Centres, engaged in some supervised paid work in the past and reported great latent benefits from doing so, including raising self-esteem. The seven participants chosen for this paper best illustrate the balance of latent and manifest mediators of employment.

A lifecourse perspective was adopted from the start of this study. Women at mid-life have a lifetime of lived experiences that impact their decision-making process. Arising from the confluence of several major theoretical streams of research that emphasise both social structure and individual agency, the lifecourse framework (Elder, Reference Elder1998) seeks to consider the social surroundings of the individual and offers a dynamic approach to the stories of people's lives over time in an ever-changing society (Hunt, Reference Hunt2005). People need time and space to review adequately the influences that have brought them to the mid-lifecourse stage. Understanding older women's narrative on the important role of work over the lifecourse allows us to appreciate the interconnections between the life phases.

The chosen methodological approach for recruitment, data collection and analysis was informed by constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006) as it allowed for exploratory participant reflection, helping to facilitate the discovery of fresh perspectives and emerging theory on gendered rural ageing. This research paradigm utilises purposive theoretical sampling and abductive reasoning (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Hoare and Gott2015). Although theory does not always arise from data that have been analysed using a constructivist grounded theory approach, validity, rather than the ability to replicate, is achieved. Constructivist grounded theory was considered to be an ideal method for exploratory work such as this about which little was known. Whilst the concept of gendered work benefits from a large body of study, it leans heavily on financial issues such as income and pensions. Unpacking the nuances around the concepts of mid-life, gender, work and rural ageing required a methodological research process that could be validated through an iterative analysis of data within its various contexts and meanings.

Recruitment of participants was achieved by utilising personal networks, stakeholders, snowball sampling, and by deploying print and broadcast media to raise awareness. None of the participants was known to me. However, I briefed a few personal contacts who worked with or knew of mid-life women who met my research criteria of socio-economic–demographic–geographic diversity. These contacts understood my research criteria fully and I trusted their judgement. To help secure impartiality I exercised further controls by questioning potential participants on their backgrounds in advance of interviews. The seven participants chosen from the full study of 25 for this paper were recruited through briefings with stakeholders from the public sector, voluntary organisations and community groups. The substantial 20-year age range employed in this study of rural women aged 45–65 years allows for intra-sector comparison and ensures that this lifecourse stage is examined from the diverse perspectives of those in both early and late mid-life. Participants with diverse socio-economic backgrounds were selected on the conceptual basis that they might add something different to data already collected. This study is qualitative in nature and no quantitative income or class classifications were sought regarding participants. Participants did, however, proffer their educational levels: 12 of the 25 participants had attained secondary-level education only, eight third level, three fourth level, and the two participants with intellectual disabilities primary level only. Of the seven participants selected for this paper, three had third-level qualifications and four had second-level. Diversity was sought amongst those who were partnered, lived alone, with and without children, employed and unemployed, living in a variety of rural environments and who reflected the 20-year age range. Two women in the larger study had undefined intellectual disabilities that prevented them from engaging in the workplace without help. Their disability had been identified through the Health Service Executive system in Ireland. All 25 participants were white as it did not prove possible to secure those of a different ethnicity. However, a number of non-Irish, European women were secured.

Data were collected during the most recent period of socio-economic austerity in Ireland (2008–2013 and beyond). Sampling of 25 participants by semi-structured one-to-one interviews, all living in the region of rural Connemara took place over three timelines. The entire process of data gathering and analysis was at all times informed by reference to constructivist grounded theory methodology. In practice, this meant that one-to-one interviews were deliberately open-ended in nature. Topics of conversation were only introduced by me as interviewer; the participant led the narrative. This methodology supports exploratory study, does not set out to prove or disprove any theory, and allows for the introduction of any topic by the participant. If the participant feels that their narrative is relevant to the overall topic, then it becomes so. The analysis and interpretation of this narrative may at times prove challenging for the researcher, but that is part of the process.

Interviews generally were around 90 minutes to two hours in length. Participants decided on interview location, and around half of all interviews took place in participants’ own homes, half in a neutral venue. Of the seven participants selected for this paper, five were interviewed in their own homes and two in a neutral venue (hotel).

In the fuller study, an initial pilot phase of three participants tested interview technique. Questions were simplified as a result in order to gain more unambiguous answers. This was followed by phase two, during which ten new participants were recruited who helped to fill conceptual gaps, including class and education, missing from the pilot phase. Phase three of the sampling took place after a six-month period during which further conceptual gaps, including disability and geographic location, were addressed. Data analysis of participant transcripts was informed by constructivist grounded theory guidelines (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006) through coding in an iterative fashion and constantly comparing codes both within and between transcripts to uncover categories or themes, and any emerging theory. Transcripts were analysed to explain both content and context, examining not just what was said, but what was sensed through keen observation and interaction. For example, a participant may laugh at her own comment on how she wished her husband would disappear, but clearly did not mean this literally; this was her way of ‘softening’ her comments on her desire for an easier life. When non-verbal language contradicted verbal language I would note this in memos and field notes.

Memos can detail anything from the meaning and use of codes, concepts and categories, to data and ‘defining moments’, and can act as a vehicle to explain why initial codes are subsumed into focused codes and theoretical categories, ultimately explaining any substantive theory reached. Thus, memos can be written iteratively over the entire time period of analysis. In addition, memo-ing can help untangle complex or contradictory data gathered within interviews, such as those involving participants who had suffered bereavements. For each transcript I constantly compared data, along with possible conceptual and theoretical categories, in order to help me explain and justify what was happening within participant discourse. Memos also helped me to identify gaps in analysis that needed addressing, and allowed me to record personal reflections on how effective I felt the interview had been, commenting on context, setting, place and non-verbal communication. Memos allowed me to highlight which questions worked well and which did not, noting topics raised, avoided or missed by participants.

Open codes, using gerunds, were the first step employed to describe participants’ words. This was followed by more abstract focused coding and theoretical coding, which allowed for the development of categories and the emergence of possible substantive theory. This reflexive and flexible approach to analysis allowed for the constant comparison of data, codes, concepts, patterns and gaps until it became clear that the properties around the concept of gendered, rural work had become saturated. The seven participants cited in this paper were selected on the basis of their individual criteria that speak to the complex drivers of work beyond financial remuneration, and explore the personal latent outcomes acquired.

Ethical issues

In keeping with the nature of qualitative research, ethical considerations underpinned the entire research process of this study, particularly during data planning, data collection and data analysis. Thus, participants were guaranteed anonymity of names and locations, and pseudonyms are used throughout the study. These points were outlined to the National University of Ireland Galway Ethics Committee and ethical approval was granted in 2013. Participants were issued with an information sheet outlining the study's purpose and university Ethics Committee contact details, as well as a consent form to sign. It was made clear that participants could leave the study at any point and that their data would be destroyed.

Findings

At mid-life, participants of this study had largely not yet retired from employment and most were not planning to. This study shows ambivalence towards retirement, deriving from a belief that employment can augment not just the manifest benefit of money, but latent benefits, such as those cited by Jahoda (Reference Jahoda1981), and additionally protect against cognitive decline in older age. Benefits that participants believed paid work offered included extended social networks, increased income, sustained self-esteem and positive mental health.

Table 1 contains demographic details of participants cited in this paper.

Table 1. Demographic details of the participants

Of the 25 participants interviewed as part of the wider study on gendered ageing, narrative from the seven cited in this paper best illustrate the critical intersections of work, gender, ageing and rural place. These participants are selected to address this study's research issue around the non-financial, latent drivers of work for older rural women. Participants are arranged largely in pairs for the purpose of contrasting latent benefits to paid employment, benefits which both extend and explore those cited in Jahoda's theoretical framework.

A number of participants had partners who were largely unemployed, in part due to the collapse of the construction industry during the last recession in Ireland (2008–2013 and beyond). As a result, these participants had become the main income providers, and the manifest benefit of employment income was a prime driver to wanting to work. Whilst this most recent economic recession negatively impacted almost everyone, older men, and particularly those in construction, were particularly vulnerable (Ni Leime et al., Reference Ni Leime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017). The only alternative income for such men was from social welfare supports or from casual, irregular forms of employment such as fishing or ‘handy-work’, which has partly brought them more into line with work patterns for their female counterparts, who historically are used to casual part-time working.

The manifest benefit of employment income may be a strong driver for older rural women, but may still not provide enough benefit for financial security in later life. Whilst some participants alluded to the wisdom of financial planning at mid-life, most did not feel in a position to do so. Two-thirds of women in Ireland are reliant upon the lower non-contributory state pension (Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection, 2019) as a result of fractured employment histories and lower rates of pay, something which is reflected in the findings of this study. Only around one-third of participants were employed in work that offered a contributory pension, leaving two-thirds of participants responsible for their own private pensions or dependent on the non-contributory state pension. Many of the participants of this study had learned to live on low incomes over their lifecourse, which appeared to offer them some confidence to budget in older age, but financial exposure still posed a threat to wellbeing. There was a degree of reluctance amongst many participants to discuss finance in later life, perhaps from feelings of lack of control, and a general attitude that leaned towards a ‘present bias’ (Hayley et al., Reference Hayley, Price and Buffel2020) of ‘living for today’ and hoping things would turn out alright.

That people work for both monetary and non-financial reasons is as true in small rural communities as it is in large cities, as true for men as it is for women, and also mainly true for all ages across the lifecourse. However, significant variances exist in the intersections between work, gender, rural place and age. Work largely offered the mid-life rural women of this study the safety of an income and some financial independence, but also an expanded social network, a sense of life purpose, a feeling of usefulness and desired ‘busyness’, and an alternative identity outside the home (Berkman, Reference Berkman2014; Damaske, Reference Damaske2020), all of which were highly valued. It is to these latent, non-financial outcomes of work that we now turn.

Denise and Christine: self-employed for passion and generativity

Denise was single, in her late fifties, had worked as a visual artist all her life, and her unique installations were her personal identity. She re-located to a dispersed rural part of Connemara in order to find the environmental landscape best suited to nurturing her ‘self’ and her work. Denise was passionate about her work, irrespective of precarious levels of financial return:

Look at that mountain there – it's sacred. I am work obsessed. I am a bit of a workaholic but you kind of have to be if you want to continue to be an artist in the art world, as it's very demanding, especially as you get older. I sometimes think should I take a year off, but then I'm not sure I could afford to. And then you think what is this all about? And only recently did I realise that there is a money aspect to my life, and I wouldn't have thought there was before. I sometimes struggle to pay the mortgage. I have it for another ten years and I wish I didn't, but I am managing to pay it on my own without any help, and I think as a woman that's great. The way I lived was like there is never a salary or a regular job, not ever, and I'm half proud of it, but it's also half nuts. The market for my work is narrow. I don't perform for market – that is secondary. You do the work and hope there is a market, especially during a recession. I've never done anything for market – you'll find difficulty surviving in the commercial world if you do. (Denise, 57 years)

Self-employed participants mostly expected to work beyond the state pension age of 66 years, and none from this study reported contributing to a private pension scheme.

Although 50-year-old Christine worked to make money, generative reasons were also a prime driver. Christine and her husband ran two businesses in the education and hospitality sectors: renting out holiday homes and running a summer English language school. They reported a preference for self- rather than hired employment, believing it offered more excitement and opportunity. Recognising the few employment opportunities in Connemara for young people, Christine and her husband planned to use their own businesses to provide work for their six children, but work also provided Christine with an additional identity to that of mother and housewife:

I'm not just a mother and a housewife … me and my husband work together in the business. I suppose it is a bit more than money [why we work] and if we could build up a proper business we could leave something for our children as there is not much employment around here. Being self-employed is hard going but I'd hate to have to get up every morning and have to work in the stress and hassle at a desk 9 to 5. I can't see retirement like a public servant would, you know finishing at 65, even if the kids are working. Like the kids will be going to college and they will all need support through college, so we'll need to keep working for the kids to have an income till we are at least 75 I think. Also, it's quite remote here – once your family is grown up and if you weren't working it could get quite lonely. (Christine, 50 years)

All participants were anxious to be engaged at mid-life, feel productive, be of service or feel connected with others. Working outside the home offered vital socio-psychological as well as economic benefits including improved self-esteem, expanded social connections and an additional source of self-identity (Berkman, Reference Berkman2014). These two participants recognised the financial necessity to work to pay the mortgage, extend the business and support children, but both also reported clear latent benefits that work fulfilled. In Denise's case, her creative work matched her life's passion, whilst Christine wanted to showcase her own talents to create business and be perceived as more than a mother and wife.

Tina and Hilary: principal earners in household; work providing identity and purpose

Tina had moved from the UK to Connemara, her husband's home. In her mid-forties Tina had a full-time pensionable job in the public sector and had recently refused a package to retire early, feeling that at her age she should be working, a concept that is supported in literature on temporal ageing (Krekula, Reference Krekula2019) and the ‘age-graded normative organisation of society’ (Holman and Walker, Reference Holman and Walker2020). In addition, her husband was one of the many construction sub-contractors who had become unemployed during Ireland's most recent recession, and was unlikely to find replacement work for some time, making Tina the main earner. Tina was highly conscious of her identity, both in and out of the workplace, and strongly linked work with producing higher self-esteem. Work also provided a valued feeling of busyness, which influenced her perspective on future retirement:

There just never seems to be enough hours in the day. But saying that if you were to lose your job, I'd rather be too busy than too quiet. I suppose it's for more than just the money I work, definitely I prefer to be working. We have good craic at work. I mix with one or two outside of work occasionally. The interaction is good, being at work gives you. When you move back to an area like this, you're either somebody's mother or somebody's wife. It was lovely to go in to where I was me. If you work in the workplace and make judgement calls you feel you have earned that right a little bit. If you are making right decisions at work, then why shouldn't you be making them at home as well? Whereas if you didn't have work, and your child challenged you, you might start to doubt yourself a little bit. Make sure you're not defined as just the woman picking up the kids from school, or the person who has the dinner on the table. You need something back for yourself, that's very, very important. (Tina, 46 years)

As the principal earner in her household of husband and adult children, Hilary had a strong work ethic. Although feeling over-stretched, Hilary, in her early sixties, still planned to work until she was no longer able. This participant worked shift-systems in the caring profession, looking after clients with Alzheimer's disease. Despite the heavy physical and emotional work involved, she was loathe to consider retirement (Sherry et al., Reference Sherry, Tomlinson, Loe, Johnston and Feeney2017). Her husband had been made unemployed as a result of the collapsed construction industry during Ireland's most recent recession, and he, along with her adult children, were all back living at home for economic reasons, reliant upon state benefits for income. Despite being over-burdened with domestic responsibilities and challenging employment, Hilary both needed the money and the escape from domesticity that work provided, and strongly believed that her quality of life would suffer if she retired and had to spend more time at home:

I'm busy, very busy. By the time I get home from work and clean the house, get dinners, throw the dishes in the dishwasher it's time to go back to work again, and then when I finish work … putting the Alzheimer's woman to bed … but I love it, there’ something about helping people with Alzheimer's. By the time I get home I'm flattened and it's time to go to bed. We're finding it difficult at times to make ends meet, with me getting a few bob working, and him getting a couple of euros on the pension – a non-contributory pension. I don't like anything about getting older to be honest with you, and I hate the day when I have to finish work and go on the pension. If I'm still able to drive and walk, I'll continue on working. Jesus, what would I do at home? (Hilary, 61 years)

Retirement from work, like mid-life itself, marks a pivotal point in the lifecourse (Lachman et al., Reference Lachman, Teshale and Agrigoroaei2015). Some participants regarded retirement from work as the start of a new chapter in their lives; others viewed retirement as the start of old age (Manor, Reference Manor2017). Most participants wanted to continue working for both financial and non-financial reasons whilst concurrently looked forward to a time of new opportunities post-retirement. This paradox is not so unusual; in their assessment of older, age participants understood that the lifecourse allowed for ‘overlap’ between a late period of work and an even later period of non-work. Most felt that the mid-sixties was too young to retire, some, like Hilary, wanted to work forever, whilst others foresaw a time, perhaps in their seventies, when they might enjoy retirement. Most participants felt anxious about retirement at mid-life; it felt temporally too early (Krekula, Reference Krekula2019), and produced negative feelings of disengagement (Coward and Krout, Reference Coward and Krout1998), inactivity and unproductivity. Concern over ageist stereotypes, accelerated physical and cognitive ageing, and a loss of identity may become a problem without work-related activity (Reference Niesel, Buys, Nili and MillerNiesel et al., in press).

Margaret and Mary: work as a lifestyle choice

Margaret was married to a farmer (Balaine, Reference Balaine2019), who akin to most part-time farmers in Ireland, had a second waged job. Margaret, as well as helping out on the farm, represented one of the 34 per cent of spouses in Ireland who worked off-farm (Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Moran, Lennon and Donnelllan2017). Margaret wanted an income of her own, but also wanted to work for social reasons, which offered her a non-domestic outlet, boosted her self-esteem, and provided purpose and social connections that she felt protected her cognitive functioning:

I work three days in a little coffee shop – I love it. I kind of like my free time now, and to be able to play my golf. I kind of have got to this stage now, my life isn't about work anymore. Now it is for my husband – he has to work, but I don't. As long as I have a bit of pocket money I'm ok. Work – like it's money, but meeting people keeps you going. When you're working you have to kind of put yourself out there a bit and I think that's good, sometimes you need a little bit of pressure to make you do stuff as well, and that kind of keeps the wheels in motion. (Margaret, 50 years)

The desire to feel productive was common to all participants. Whilst retirement can potentially be as busy and productive as the lifecourse stage prior to it, for a number of participants of this study, it was considered to be a negative lifecourse phase with little to offer (Manor, Reference Manor2017). Mary and her husband had both officially retired from regular paid employment, yet did not feel retired as they both engaged in regular volunteering and some casual paid work. For Mary, feeling productive and busy were essential to her identity, and of all participants of this study, she held the strongest views on visible physical ageing (Bordone et al., Reference Bordone, Arpino and Rosina2020). Concurring with literature, a number of participants, like Mar,y adhered to the ‘use it or lose it’ credo or ‘disuse hypothesis’, and believed that work protected the brain from cognitive decline (Sarabia-Cobo et al., Reference Sarabia-Cobo, Pérez, Hermosilla and De Lorena2020). Continuing to be active helped to make her (and her husband) feel younger physically and mentally:

Neither of us talks about retiring, we just go from day to day and do what we can. We wouldn't consider retirement unless forced, and if we did we'd be out doing something else, like the Heritage [voluntary]. I couldn't stay here sweeping the kitchen floor. (Mary, 62 years)

May: involuntarily unemployed

Three participants from the larger study were involuntarily unemployed. One was undertaking some voluntary work to compensate; another was still raising her children but hoped to be able to secure work in the near future. The third, May, cited in this study, felt physically unable to undertake work, living with severe chronic pain. She had run the local post office until its closure, which has caused her a great deal of anxiety. A number of rural post offices continue to close across Ireland as part of government austerity and An Post restructuring measures (Power, Reference Power2018). In addition, May had experienced a number of family deaths, including her husband, a son and a close friend, all adding to her feelings of isolation and loneliness. This participant had engaged in some volunteerism but wanted part-time paid work in order to feel more valued and to provide badly needed income to supplement her widow's pension. Critically, May needed paid work for reasons of connectivity, purpose and identity: to feel a ‘somebody’. Through widowhood and retirement, May felt cast into a position of solitude (Vasara, Reference Vasara2020), but ideally wanted to engage with the world through some form of paid employment:

I'm really not able to work. If I had to sit for two hours, I'd hardly be able to walk when I stood up. I had to give up the post office as it wasn't automated – If they only left me with it for two days I would have done it for half nothing, but no, they just wanted to be rid. No matter what your troubles were, people came in and told you all sorts of stories. It was a reason every day to get up. I think to be getting a little bit of pay for something, like a job, that's good. I think going out to do something for a day even, working, I'd become somebody again. I've always known what recession was. Even this extension I got on to the house after my husband died … I got a loan from the County Council, and I'll be paying that back till the day I die, but I don't mind, as long as they keep giving me the Widows Pension. (May, 65 years)

May owned a car but had only a provisional licence and did not anticipate gaining a full licence in the near future. Thus, her desire to work was negated by her poor physical and mental health and her rather remote rural location that required the use of private transport Shergold Ian; Parkhurst Graham; Musselwhite, Charles, Reference Shergold, Parkhurst and Musselwhite2012 It was easy to empathise with May's feelings of hopelessness brought about in part by unemployment.

These seven narratives underpin the inter-sectional nature of work, rural, gender and ageing (Holman and Walker, Reference Holman and Walker2020), illustrating how paid work affords latent benefits beyond mere income.

Conclusions and discussion

Findings from this study not just support, but extend Jahoda's (Reference Jahoda1981) model of employment by examining the latent consequences of employment within a gendered Irish rural context and within the mid-life phase of the lifecourse. This study also challenges some of the narrative around the negative impacts of the extended working life advanced by critical gerontology. Empirical evidence in this study shows that paid employment is critical to wellbeing and that many older rural women choose to work into later life, irrespective of levels of manifest reward, in order to benefit from perceptions of improved social status, sense of purpose, personal identity, social connectivity, time structure and productivity. This is not in any way to diminish the importance of finance to older rural women's quality of life, but instead to demonstrate that work in later life is about more than money alone. This helps speak to the ‘push–pull framework’ around retirement, the extended working life and the factor of choice (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Chauhan, Spirling and Stewart2018). From a lifecourse perspective women's decisions to retire or to continue working (Ní Léime and Ogg, Reference Ní Léime and Ogg2019) are based not just upon manifest or latent benefits of employment, but are influenced by factors such as the nature of work, health, family demographics and geographical place.

In examining why many mid-life rural women want to keep working into older age and why this matters, we need to consider the complexities around rurality and the gendered nature of work and ageing. Sustainable paid employment is rarely the norm for older rural women; nonetheless, work in all its forms is a strong influencing factor in shaping quality of life (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Gibson, Greasley-Adams, McCall, Gibson, Mason-Duff and Pengellyin press). The latent consequences of work, as defined by Jahoda (Reference Jahoda1981) – time structure, collective purpose, social contact, social status and activity – concur with the findings of this study. However, this study extends Jahoda's model by examining the nuances within each of these elements within a gendered, rural context at the mid-life stage of the lifecourse, as well as highlighting additional latent benefits not discussed in Jahoda's model. In general, participants of this study recognised that paid work offered them the opportunity for improved connectivity (Herbert, Reference Herbert2018), augmented personal identity (Biggs, Reference Biggs2005) and financial agency (Bowling, Reference Bowling and Walker2018). Specifically, individual latent benefits of employment reported by participants included: self-esteem, self-confidence, antidote to loneliness, life purpose, economic contribution and constructive use of time. The principal latent benefit of employment for artist Denise was an outlet for her creative passion; for Christine, generativity and self-improvement. For Tina, the principal latent benefit of work was self-validation and for Hilary straightforward productivity and ‘busyness’. Whilst Margaret used part-time work as a social outlet, for Mary, work helped to combat societal ageism and helped her feel younger. May mirrored Jahoda's negative model of unemployment through feelings of ‘invisibility’ and worthlessness; only paid employment could make her feel like a ‘somebody’ again. Such findings are underpinned by a wide body of literature that recognises paid work as providing a primary role in society (Berkman, Reference Berkman2014), which once removed through unemployment or retirement may have far-reaching detrimental consequences to health and wellbeing. Notably, Berkman (Reference Berkman2014: 1518) states that ‘Good jobs can provide dignity and meaning in life, but even jobs with harsher working conditions permit workers to take care of themselves and their loved ones’.

Self-employment may seem like a viable option for older women in rural areas with a narrow choice of work (Hodges, Reference Hodges2012), and indeed one-third of this larger study's participants followed this work. However, temporal control sometimes came at the expense of precarious income levels and an unhealthy work–life balance of discretionary time. Additionally, it should be noted that feeling forced into self-employment to escape unemployment may confer few latent benefits (Binder and Coad, Reference Binder and Coad2016) if the trade-off is too great.

No participant wanted to be unemployed, and of the 25 participants only three were. However, volunteerism was not viewed as a viable alternative to paid work (Warburton and McLaughlin, Reference Warburton and McLaughlin2006). Whilst much of the literature links volunteerism to life satisfaction amongst older people (Warburton and McLaughlin, Reference Warburton and McLaughlin2006), some question its ethical implications and its association with the model of healthy ageing (Martinson and Halpern, Reference Martinson and Halpern2011). Healthy ageing for participants of this study involved paid employment, not volunteerism, not just for reasons of finance, but for feelings of worth and identity. Those unemployed reported a lack of purpose and identity in life, which had negatively impacted their mental and physical health, and increased their risk of social isolation (Drydakis, Reference Drydakis2015; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea and Scharf2020). Undoubtedly, the latent benefits of work have been shown to contribute to good mental health (Payne and Doyal, Reference Payne and Doyal2010), suggesting that working at both mid-life and beyond should embrace a new paradigm that speaks to quality not quantity: not a longer, but ‘fuller working life’ (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2018; Ní Léime et al., Reference Ní Léime, Ogg, Rašticová, Street, Krekula, Bédiová and Madero-Cabib2020).

Embedded in the desire to work in later life was the temporal concept of ageing: no participant of this study felt old enough to retire (Krekula, Reference Krekula2019), even though some were close to the current official retirement age of 66 years. The key issue regarding the concept of retirement and subsequent quality of life is that of choice (Ní Léime and Ogg, Reference Ní Léime and Ogg2019; Sarabia-Cobo et al., Reference Sarabia-Cobo, Pérez, Hermosilla and De Lorena2020). This study showed ambivalence towards the concepts of both retirement and the extended working life. Mid-life proved to be a time of change, a time to review the past and plan a new future (Biggs, Reference Biggs1999; Lachman et al., Reference Lachman, Teshale and Agrigoroaei2015).

Some participants, particularly the self-employed, planned to continue working for the rest of their lives, health permitting. For the others, there was still a desire for an ‘active, positive, successful ageing’ (Rubinstein and de Medeiros, Reference Rubinstein and de Medeiros2015), however these concepts are defined.

Current issues around gendered, rural ageing and work are likely to be amplified by the current COVID-19 pandemic. Mid-life women have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to job loss and worsening work contracts, but one possible ‘upside’ of the current pandemic is the increasing numbers working from home, which reduces commuting time and allows greater working flexibility. This may offer wider female participation and greater workforce diversity among those living in remote rural areas, and those who are house-bound and caring for dependants (Couch et al., Reference Couch, O'Sullivan and Malatzky2020). However, a number of ‘gender-typical’ employment sectors do not lend themselves to remote working, including health care, hospitality and retail (Henriques, Reference Henriques2020). Furthermore, remote working from home or from a work-hub may require dependable internet access, and this is still a challenge in many rural areas. Thirty per cent of households in highly rural or remote areas had no internet access at the time of Ireland's most recent 2016 Census (Government of Ireland, 2021). For those living on Ireland's islands, access to computers and broadband is considerably less than on the mainland (Government of Ireland, 2021). Furthermore, some older age categories, typically found on islands, have been shown to be slow to adopt digital skills. To this end, the Government of Ireland has pledged to expand the provision of free-to-use internet connectivity in rural areas and to increase its digital skills for citizens scheme. Certainly, remote working has found overwhelming favour amongst 95 per cent of university staff in Ireland (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bohle-Carbonell, Ó Síocháin and Frost2020), where despite perceptions of loneliness, isolation and child-care issues, there are perceptions of improved quality of life. Nonetheless, studies are also highlighting problems of longer working hours, always being on call and a poorer work–life balance than was experienced in pre-pandemic working life (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bohle-Carbonell, Ó Síocháin and Frost2020). Remote working may or may not prove to be a short-term measure; either way, the socio-economic outcomes are uncertain (Blundell et al., Reference Blundell, Costa Dias, Joyce and Xu2020). More time working at home with the family may remove the critical latent work benefit of real-time social connectivity.

Policy recommendations

Drawing on the findings of this empirical study, it can be argued that there is scope at policy level for the enhancement of gendered rural ageing in later life through measures that support the medium of paid work.

Many older rural women gain a positive identity from paid work and do not want to be, or seen to be, unemployed or retired. Thus, support measures for older rural women that make working later in life easier for them to access may result in positive social, psychological and economic outcomes. Ageism and stereotyping, both perceived and real, proves to be an ongoing dilemma in society, including in the workplace, and needs to be addressed beyond just legislation. The impact of age stereotypes and ‘lookism’ on employment opportunities disadvantages all older people, but especially older women, who are generally judged more harshly on visual appearance than men are (Biggs, Reference Biggs1999; Bordone et al., Reference Bordone, Arpino and Rosina2020).

Population demographics are changing and so too the make-up of workforces, which are set to become more unpredictable and fragmented as people live and work longer (Gratton and Scott, Reference Gratton and Scott2016). If older rural women are not allowed to work or cannot find suitable work they will have to live on less in later life, or to rely, where appropriate, on a partner's or dependant's resources. They may have to rely on below poverty-line social welfare payments for extended periods, especially in the years leading up to state pension eligibility, currently at 66 years. This is neither good for the Irish rural economy nor individual wellbeing. With rural-sensitive support, some may be able to re-train and up-skill (Centre for Ageing Better, 2019) in order to exit casual work or to compensate for work that may be lost to technology (Deloitte, Reference Deloitte2019). There is a need to lay a foundation that caters for the increasing numbers of older rural women who want or need to work into later life, but one that recognises the processes of cumulative advantage and disadvantage over the lifecourse (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2003), and of how lived experiences at all lifestages may impact the risk in old age of poverty and social exclusion (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea and Scharf2020).

Rural development initiatives that are relevant to older women, as outlined in recent government plans (Government of Ireland, 2016), need to be extended and implemented by more creative forms of rural education and training that are spread over an entire career (Gratton and Scott, Reference Gratton and Scott2016). Additional measures could include workplace training and supports for all age groups (Reference Edge, Coffey, Cook and WeinbergEdge et al., in press), a greater diversity of rural jobs, increased supports for the self-employed (Tomlinson and Colgan, Reference Tomlinson and Colgan2014), and more flexible gendered employment and pension conditions. Imaginative gendered rural employment policies could help to release the untapped potential of thousands of women who are out of the workforce or under-employed within it, but could be attracted back under the right conditions. This may have particular relevance in the current pandemic recessionary climate (Centre for Ageing Better, 2020a).

Research implications and limitations

Future research on rural women and work could extend the findings of this study from an intersectionality perspective (Holman and Walker, Reference Holman and Walker2020) by examining how multiple socio-economic characteristics such as gender, rural and age may contribute towards unequal ageing. Literature and policy could benefit from focusing on the intersections of work and ageing amongst the rural waged and unwaged, the coupled and those living alone, and those living in different types of rural environment. Critically, new perspectives among mid-life rural women on work and retirement, perhaps informed by the COVID-19 pandemic, may be particularly useful in supporting narrative around gendered ageing. Although not rural-specific, a recent UK report on changing work patterns (Crawford et al., Reference Crawford, Cribb, Karjalainen and O'Brien2021) finds that women in their fifties and sixties are likely to have difficulty finding work after the pandemic. This poses a considerable challenge for those who want to work into older age.

A limitation of this study may be the small sample size of seven participants, but this should be considered within the context of the much larger study of 25 participants from which this sample was selected. The rich data gained from this sample of seven participants reflects the breadth and depth of the original larger study.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was granted in 2013 by the National University of Ireland Galway Ethics Committee.