Although texts dealing with death and the immediate fate of the soul had existed for centuries, related images appear only in the Middle Byzantine period, after many – even if not all – aspects of the afterlife had been solidified. Thus the visual imagination takes over as theological interest wanes, while it remains heavily indebted to it. Images of the soul’s separation from the body, the provisional judgment, and Hades and paradise, all of which constitute the focus of this chapter, are patently influenced by the pertinent texts. The many variations on one theme – such as Hades – reflect to a large extent the divergent imaginings of the texts. Yet, as I shall argue, the relationship between the two is more complex than the mere illustration of the written word. A composition involves a process of inclusion and omission; what is depicted and what is left out is of great significance.

The Separation of the Soul from the Body

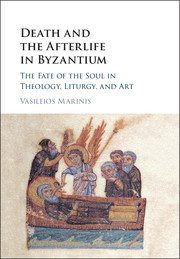

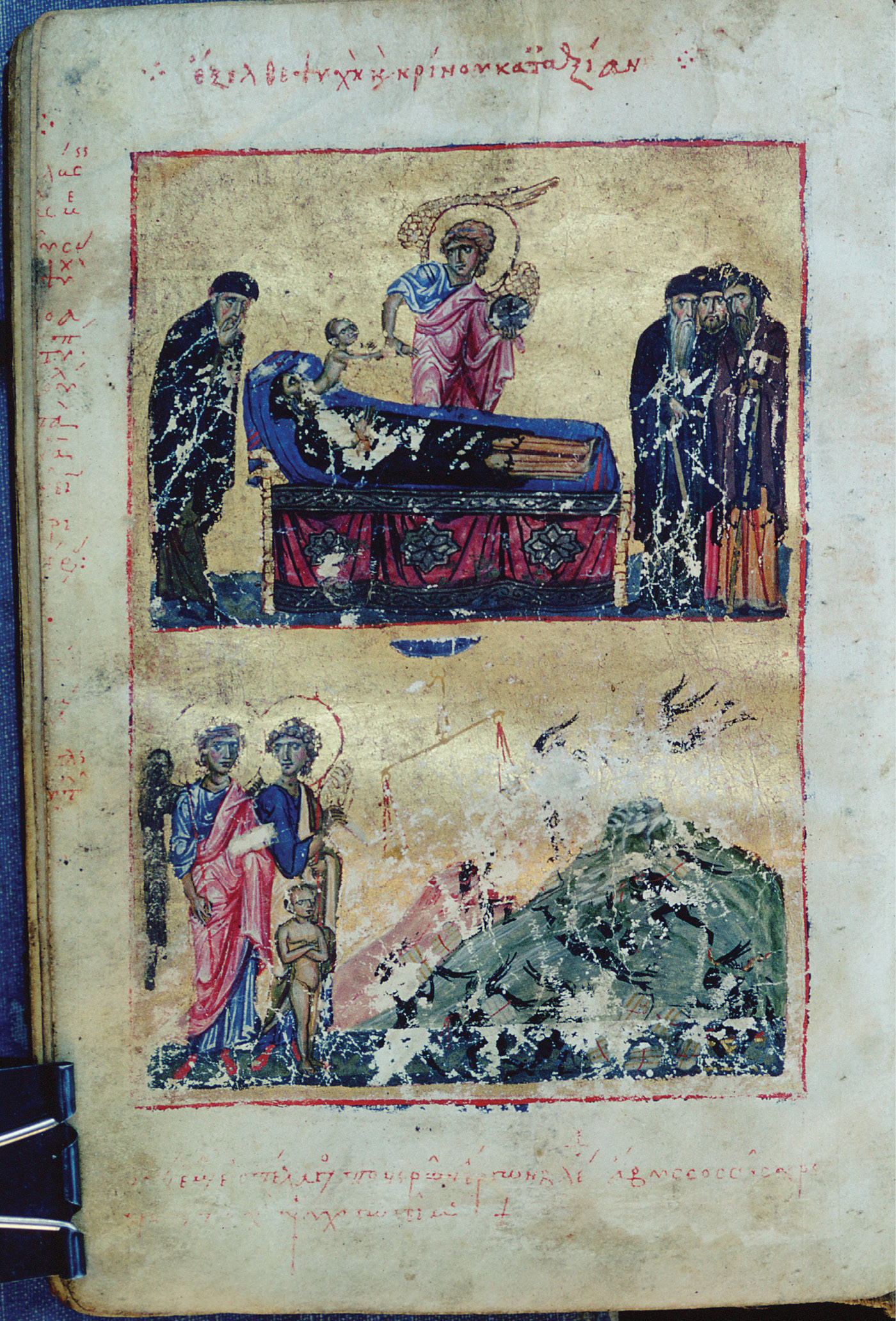

Many sources, including Cyril of Alexandria and the Life of Basil the Younger, describe the terribleness of death, including the apparition of unsympathetic heavenly beings, and the pain and agony of the separation of the soul. Quite appropriately, an image of the separation of the soul from the body decorates the beginning of the chapter of the Heavenly Ladder dedicated to the memory of death, in fol. 63v of Princ. Garrett 16, which dates to 1081 (Figure 1).1 There an elderly monk lies on a straw mat and an angel tears away with his right hand the monk’s soul, shown as a naked child.2 To the right of the dying monk is a group of lamenting monastics; next to his head another monk is preparing a censer.3 The basic compositional elements of the image – the dying person on his or her deathbed surrounded by friends and relatives – hark back to the earliest surviving deathbed scenes in the sixth-century Vienna Genesis (Vindob. theol. gr. 31),4 and were greatly popularized through depictions of the Koimesis (Dormition) of the Theotokos.5 However, what sets this image apart is the involvement of supernatural beings in the actual process of the separation, an essential element in virtually all written accounts of the afterlife.6 The miniature in Garrett 16 is a succinct depiction of the moment of death, different from the more common image of lying in state.7 According to John Martin, this image combines two different scenes, that of the anchorite dying surrounded by other monks, as found in menologia,8 and of angels receiving a man’s soul, found in marginal psalters.9 This, however, is not entirely correct. The closest parallel from a marginal psalter is on fol. 137r of the Theodore Psalter (Lond. Add. 19352), dated 1066 (Figure 2). Yet, in this case the angel is receiving the soul rather than dragging it from the mouth. Dragging and receiving convey significantly distinct meanings.

Images in which an angel pulls the soul away underscore the effort put into this task. This is especially evident in the angel’s raised right shoulder and wing, and his posture in the upper register of fol. 11v in psalter Athon. Dionysiou 65, which dates to the early twelfth century (Figure 3).10 Such details accord well with one of the topoi of death descriptions: The soul, realizing that the end is near and that it will soon face judgment, is unwilling to leave the body and asks the angels for some more time. For example, in the Dioptra the soul addresses the angels as follows: “Leave me, angels, so that I can repent. Be merciful and allow [me] one more year to live and escape the fear of death.” The angels, however, remain unfazed: “Your time has been fulfilled; exit your flesh.”11 According to the first lines of the chapter on the memory of death in the Heavenly Ladder, which the miniature in Garrett 16 illustrates, cowardice in the face of death is a property of human nature after the Fall from paradise. But terror of death indicates the existence of unrepented sins.12 The action of the angel emphasizes the unwillingness of the sinful soul to leave the body, as well as the violence of death.

The related image in the Theodore Psalter illustrates verse 16 of Psalm 102 (103): “Because a breath passed through it, and it will be gone, and it will no longer recognize its place” (see Figure 2).13 This verse stresses the transient nature of human life. However, the tone of the whole psalm is optimistic, expressing hope and trust in the Lord’s compassion and mercy. The psalmist is sure that the Lord will not repay punishment in accordance with one’s sins (see, especially, vv. 8–14). Thus, the image in the margin illustrates the death of someone who has no fear of what comes next. It is a depiction of the death of a righteous person. Other comparable examples make this point more clearly. In a twelfth-century fresco in the refectory of the Patmos monasteryin Greece, the dying man, lying on a mat and wearing a simple tunic, is surrounded by a group of angels, two of whom are receiving his soul (Figure 4).14 To the right stands David playing a lyre. Rainer Stichel has connected this image with a story from the Apophthegmata (surviving only in Latin) that recounts how a monk attends the death of a hopeless foreigner. The archangels Michael and Gabriel appear, but the soul does not want to leave the body. Then God sends David with his lyre and all those who praise God in (the Heavenly) Jerusalem. Subsequently the soul exits the body happily.15 The story implies that the stranger will join the righteous in the Heavenly Jerusalem.16 Finally, the motif of the soul leaving the body by itself was applied to images of the Dormition of the Theotokos – again somebody whose salvation was not in doubt – as in the chapel of Saint Nicholas in the village of Sušica, FYROM (late thirteenth or early fourteenth century), and Saint Nicholas in Prilep, FYROM (late thirteenth century).17

The Provisional Judgment

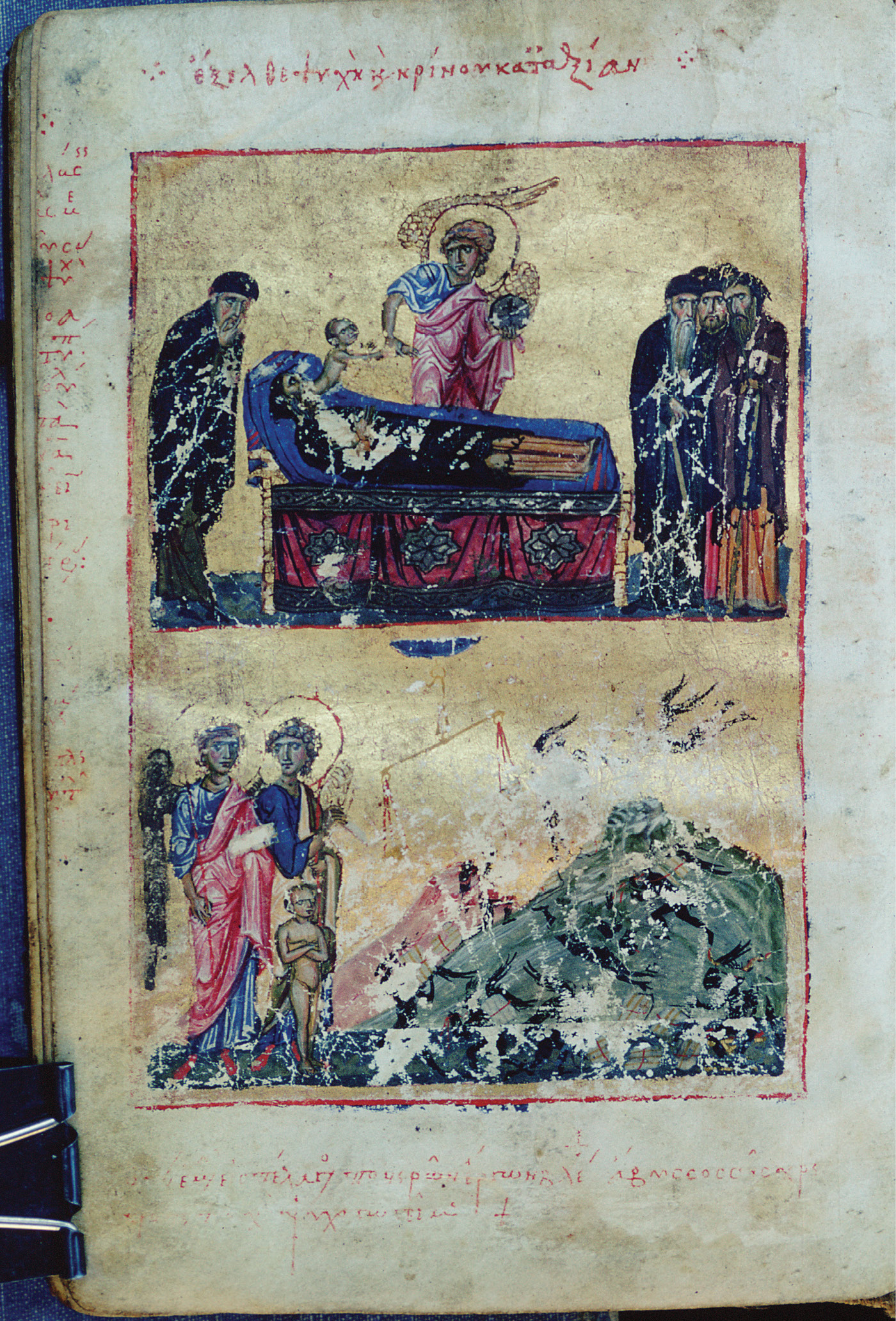

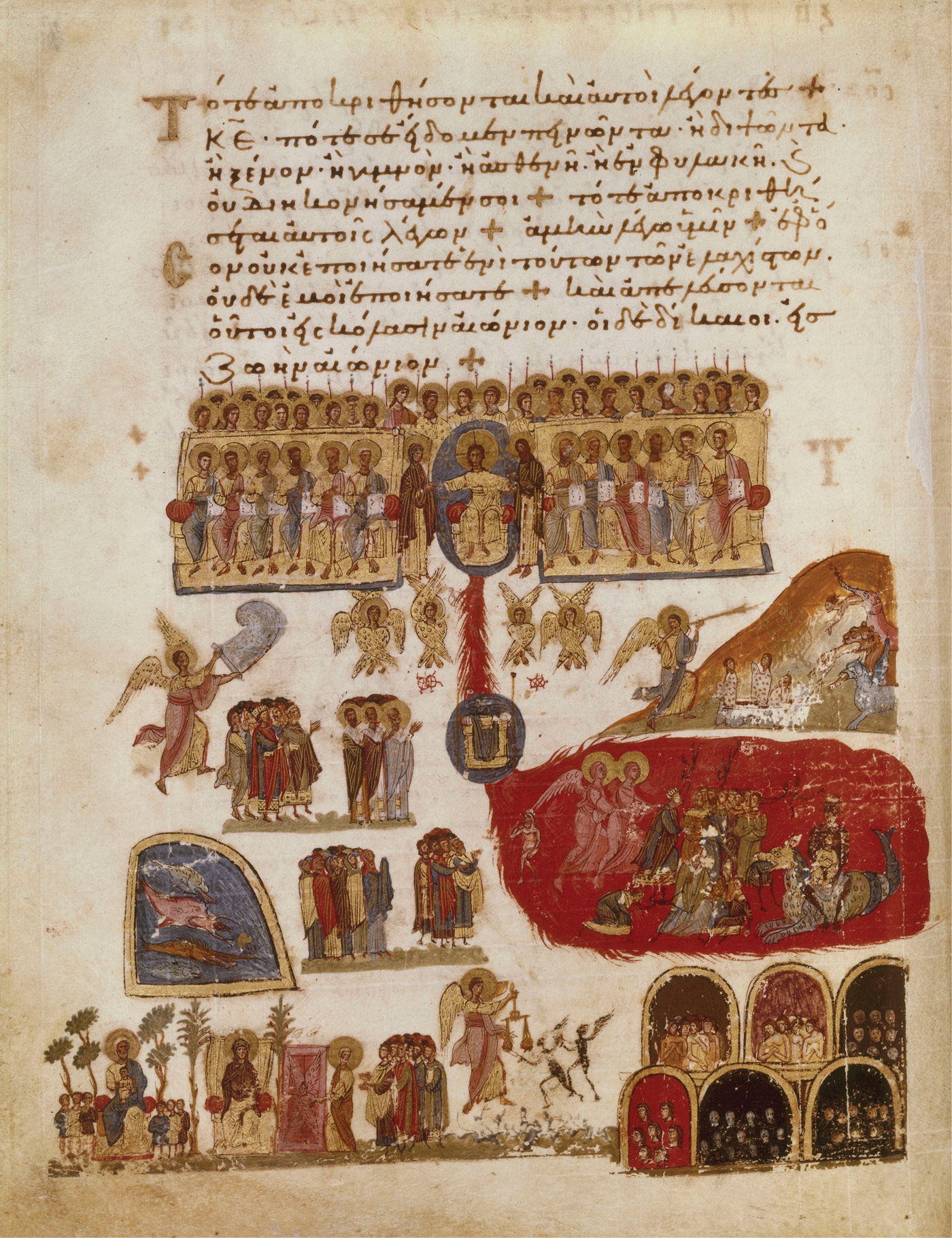

In Dionysiou 65 the separation of the soul from the body is visually associated with the provisional judgment, which is depicted in the lower register of folio 11v (see Figure 3). The title of the page, “Come out, soul, and be judged according to your worth,”18 further underscores the connection between the two. The centerpiece of the composition is a balance hanging from the blue semicircle of heaven. On the left, two angels, with the soul of the monk standing in front of them, place scrolls – the monk’s good deeds – on one scale of the balance. Several winged black demons, against a mountainous background, also carry scrolls, these containing the monk’s sins, and place them on the other scale. The balance tips toward the angels though there are visibly more scrolls on the demons’ side.

In texts, the weighing of good and bad deeds is virtually always associated with the provisional judgment that takes place at one’s deathbed; very rarely, as in the Life of Basil the Younger (II.24.6), it becomes part of the passage through the aerial tollhouses.19 However, the image in the Dionysiou psalter is evidently not a judgment at one’s deathbed, nor is it a stop at one of the numerous tollhouses; it is the whole process distilled in a single image,20 whose clarity and immediacy contrasts with the sometimes baroque elaborations of the soul’s adventures in texts. The message here is plain: After death, one is judged fairly according to one’s deeds.21

Although in texts the weighing of deeds is almost exclusively associated with the provisional judgment, in art it appears first and most often as part of Last Judgment scenes, as in the tenth-century church of Saint Stephen in Kastoria22 and Yılanlı Kilise at Belisırma in Cappadocia (Figure 5).23 This continues to be the case throughout the Byzantine period in various media.24 In fact, isolated images of the weighing of deeds, as in the Dionysiou psalter, are rare.25 This led Marcello Angheben to theorize that, at least in some early examples of the Last Judgment, such as Paris. gr. 74 (Figure 6) and the mosaics in the Cathedral of S. Maria Assunta in Torcello (Figure 7), the weighing represents the intermediate judgment that evidently precedes Christ’s final acts of condemnation or salvation.26 He noted that the weighing of the deeds is rarely mentioned explicitly in texts on which the Last Judgment iconography is based, such as Greek Ephraim. Angheben also found the presence of demons at the weighing illogical and incongruous with the Last Judgment, because at the end of times the demons would be condemned and thrown into the fire.27

This theory necessitates a brief digression into the territories of the Last Judgment. In contrast to Angheben, I posit that in the context of Last Judgment compositions the weighing of deeds depicts not the intermediate but the personal judgment that precedes the general one.

Last Judgment scenes are based on a synthesis of Scripture, homiletic literature, hagiographic accounts, and liturgical poetry.28 Because of the multiplicity of sources, early compositions often appear spatially and temporally incoherent, an assemblage of visual motifs lacking an overall narrative unity.29 As such, it is difficult to apply logic, as Angheben does, as an argument for the identification of a particular visual element. The presence of demons in the weighing of deeds is indeed illogical but identical demons drag the damned into the river of fire in Paris. gr. 74, fol. 51v (see Figure 6).30 The demons, far from being destroyed, seem excited to welcome the damned to their abode.

What, then, does the weighing of deeds represent in scenes of the Last Judgment? The most important biblical source for the whole composition is Matthew 25:31–46. In this passage the judgment is a universal rather than a singular affair, with Christ separating humankind into two groups of people, those who did the works of charity and those who did not. A personal, individual judgment is alluded to in Revelation 20:12, which recounts the opening of the books, in which each one’s works had been recorded.31 Subsequent retellings of the story combine the universal and the personal judgment into a chronological sequence. Greek Ephraim, for example, writes that in the tribunal of Christ “each one beholds his own works in front of him, both the good and the bad,”32 and that “each one’s works will be read aloud and made known in front of angels and men.”33 After this examination the Lord separates “the sheep from the goats.”34 Within the context of the Last Judgment the personal one, based on one’s deeds, becomes particularly important. First, it elucidates the mechanics of the process; second, because the “works” remain unspecified, the implication is that they include everything that a person has done, in contrast to the more restrictive, charity-based criteria for salvation or damnation in Matthew 25:31–46. Although Greek Ephraim does not explicitly connect the opening of the books with the weighing, others do. Especially important is a story widely read in the Middle Ages, Barlaam and Ioasaph.35 The hermit Barlaam, in his attempt to convert the Indian prince Ioasaph, describes the Last Judgment at length. Barlaam mentions the opening of the books that contain one’s “deeds, words, ideas,” which he associates with the weighing: “The impartial and true judge, by employing the balance of justice, will distinguish everything: deed, word, and thought.”36

The personal judgment also becomes a necessary element in images of Last Judgment, although there, unlike the pertinent texts, it is the responsibility of angels.37 In an early-tenth-century example from Ayvalı kilise in Cappadocia, one that preserves several archaic elements, angels are shown bringing closed scrolls to the throne of Christ (Figure 8).38 The scene is evidently inspired by Revelation 20:12 and texts such as Greek Ephraim, but it is neither particularly effective nor sufficiently dramatic; indeed, it was never repeated. In contrast, the weighing of scrolls, which is essentially a depiction of a personal judgment based on deeds, provides a powerful point of entry for the average viewer. While the river of fire might have been spectacularly exotic and the bosom of Abraham a rather high goal to attain, the weighing of things on a scale, by contrast, was an everyday image to which virtually all could relate. The symmetrical balance used by the angels was a standard and omnipresent weighing instrument for small commodities found in markets throughout the empire.39 Moreover, textual evidence suggests that cheating on the scales was a common occurrence.40 The image thus mined the viewer’s experience to drive home a point: everybody who looked at it would have easily recognized the act of weighing using scales and the demons who attempt to cheat. It is likely due to these considerations that the weighing of deeds became the most popular visualization of personalized judgment and was inserted in images of the Last Judgment.

Thus, the imagery of the weighing of deeds can exist in two contexts. When isolated, it depicts the provisional judgment but in the context of the Last Judgment it illustrates the process by which one’s final fate is decided. This ambiguity is noticed by Joseph Bryennios (d. ca. 1430/1), a monk and court preacher, in one of his homilies on the Last Judgment. Bryennios asks whether at the Last Judgment there will also be demons (whom he calls, among other things, telonia) examining the souls. He answers that in the presence of the Judge, that is, Christ, everything else is superfluous. “However,” he adds, “if the weighing [of deeds] and scrolls are painted in icons bearing the inscription ‘the Second Coming of Christ,’ this is not strange at all. Many things in many places are painted by the painters for the sake of zeal or in order to demonstrate something.”41 Bryennios acknowledges that the weighing is, primarily, an image of a provisional judgment. Yet he takes no issue with it being part of the Last Judgment, because painters often do things for the sake of demonstration.42 Bryennios touches upon an important point in the relationship between texts and images: The latter might be inspired by the former but they can and do operate in different contexts and levels of meaning.

But what, then, is the image of weighing supposed to “demonstrate”? Like its textual counterpart, the opening of the books containing the records of one’s deeds, it offers a crucial step in the process, the judgment of each person. Each is judged individually. Depending on the outcome, he or she joins one of the two groups, either those thrown into the river of fire or those received in Abraham’s bosom. Yet the illustrations of the Last Judgment differ from the written accounts in one subtle but important way. Whereas in Matthew and Greek Ephraim Christ is an agent of judgment, in images he is almost invariably depicted in the process of enforcing the decision by condemning or saving, as indicated by his gestures: His right hand is raised in approval, his left lowered in condemnation. In art, therefore, the actual judgment takes place at the weighing. This differentiation is not obvious in the early and rather disjointed compositions, where artists were likely still experimenting. However, it is clear in later examples, such as the funerary chapel of the katholikon of the Chora monastery (now Kariye Müzesi) in Istanbul (Figure 9).43 Under the majestic assemblage of Christ and his retinue, this early-fourteenth-century fresco depicts the weighing of an individual’s deeds as he looks on from under the balance. In contrast to earlier examples in which angels hold the balance, in Chora it is hung from the hetoimasia (the empty throne that, in this case, signals Christ’s Second Coming),44 thus creating an explicit link between Christ and the weighing and also satisfying an oft-repeated detail in the texts that the judgment takes place in front of Christ’s throne. The Last Judgment in Chora is a most sophisticated version of the composition, one in which virtually all of the disparate elements have become part of a whole.

The weighing of the good and bad deeds constitutes the quintessential image of judgment in Byzantine art. Regardless of its context, the message it conveys remains the same, that each person’s works will be assessed justly and that it is the works that will save or condemn. More often than not, the balance hangs from heaven – something that also guarantees the fairness of the proceeding. The demons that attempt to cheat the scales – a motif clearly coming from written descriptions of provisional judgments – are there for dramatic effect. In most cases, the balance remains unaffected by their efforts, or leans toward the side of the angels, as in Dionysiou 65.

Hades

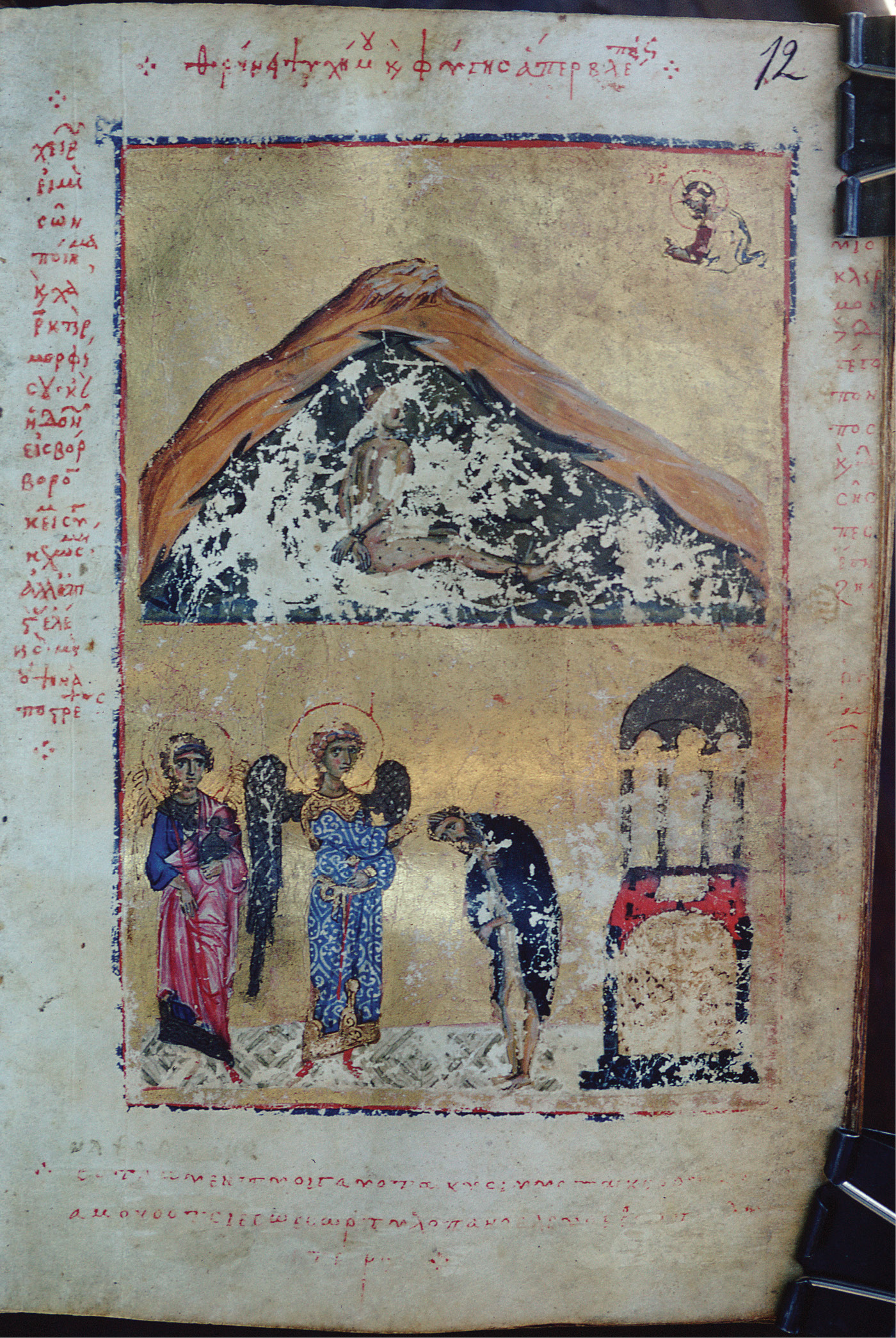

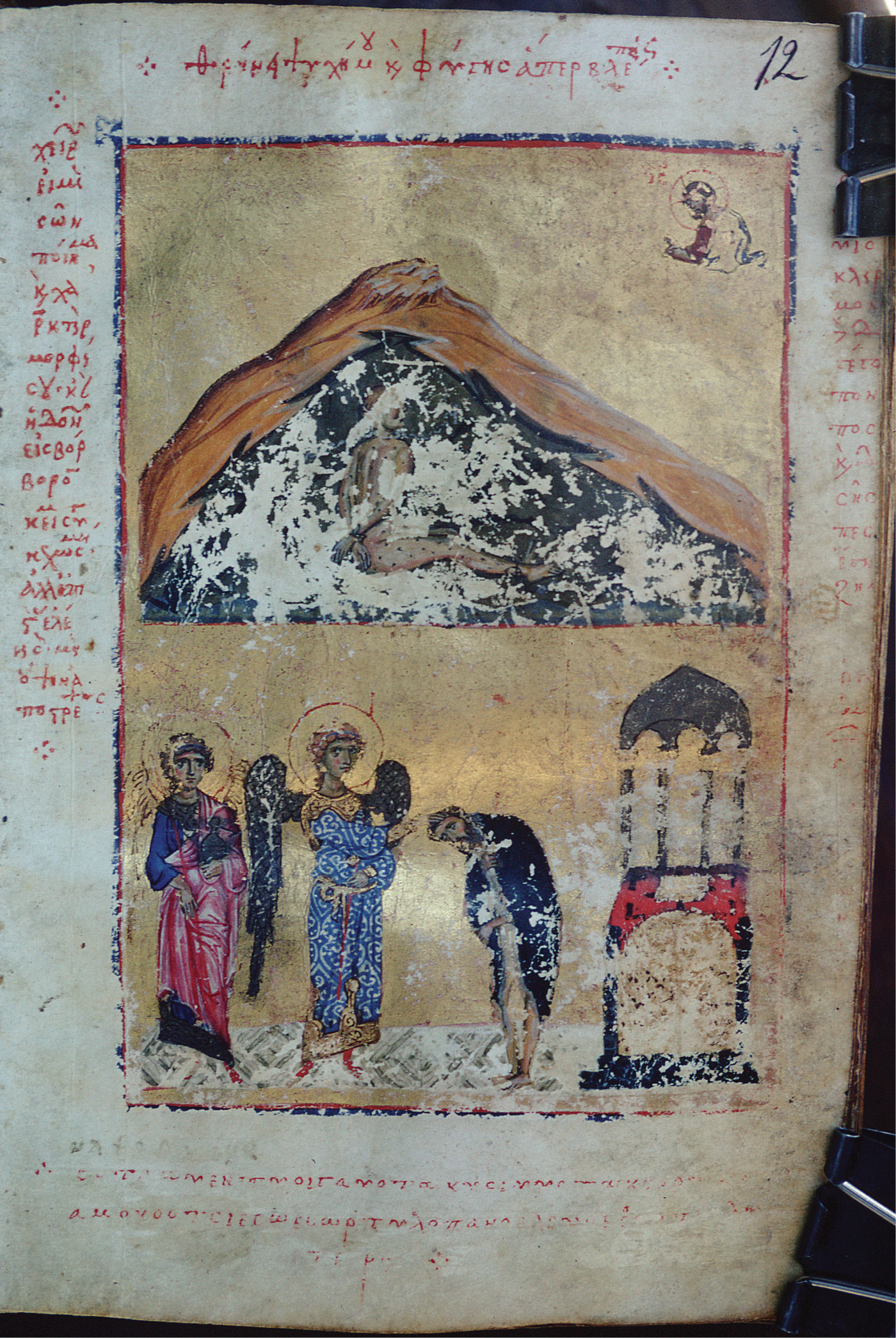

In most texts, Hades is described as a dismally dark and gloomy place (or state of being) where the souls of the damned remain and often receive punishment until the general resurrection and the Last Judgment. Images of Hades equally foreground its desolation and the despair of its inhabitants. For example, in fol. 93r of the Theodore Psalter, the naked soul of a wicked man, its hands and feet bound, is shown inside a dark cave, floating next to a fire, while an angel peers into the cave (Figure 10).45 This is part of a larger composition that accompanies Psalm 72 (73):4.46 A similar (but not identical) scene occupies the upper register of fol. 12r in Dionysiou 65 (Figure 11). There the soul also sits inside a dark cave with its hands and feet bound. Sores (or wounds) throughout its body accentuate its affliction.

The sense of despondency that these scenes convey is even stronger when one considers their iconographic progenitors. Such images combine formal elements of two others: of the rich man in Hades from illustrations of Luke 16:19–31 and of Job. The rich man is often depicted naked, surrounded by a fire reminiscent of a cave, as in fol. 145v of Paris. gr. 74 (Figure 12).47 In the Job manuscripts, the protagonist is shown naked or almost naked, his whole body covered with sores, sitting on a dung heap outside the city. Although not a cave, the dung heap often surrounds Job, creating a visual effect that isidentical to the miniature in the Theodore Psalter and related images.48 The similarities between these two compositions and the soul in Hades are more than formal. The rich man is in a place similar (although, as we shall see, not always identical) to that of the soul; Job’s desolation could be an apt metaphor for the condition of the soul in Hades.49

It is also easy to detect the textual sources of the naked, beaten, and bound soul, that has been thrown in a dark, cell-like place. For example, the homily on the exit of the soul attributed to Cyril of Alexandria describes vividly the result of an unsuccessful passing through the demonic tollhouses:

The holy angels of God leave it [the soul], and [it] is received by those Ethiopian demons, who, beating it without mercy, bring it down to the earth. And after separating it, they throw it tied in indissoluble bonds to a place dark and gloomy, to the lower parts ... a land of eternal darkness where the light does not shine nor the life of mortals [exist], but eternal pain and sorrow without end and incessant wailing and gnashing of teeth that is never silent and sleepless sighs.50

The similarities between text and image are many, but, unsurprisingly, there is not a one-to-one correspondence. On the contrary, each such scene makes subtle but consequential theological statements that are not always evident in the texts from which they draw inspiration. For example, in the Theodore Psalter (see Figure 10), the soul sits near but not inside the fire, as is the case with the damned souls in Last Judgment scenes. The fire does not immediately torture the soul but rather serves as a constant reminder of what awaits it in the end times. This is a true image of the intermediate state as pseudo-Athanasios conceived it, one of only partial punishment, one that offers only a foretaste of what is to come. The temporariness of the situation is also evident in the image in Dionysiou 65 (see Figure 11), where the soul sits waiting and unable to move. But here there is a twist: The soul turns its face toward Christ, who appears blessing in the upper right corner. An inscription on the left margin of the page, taken from a penitential poem by Nikephoros Ouranos (d. after 1007), explains this odd pairing.51 It reads: “I am the work of your hands and the likeness of your image, even though I lie covered in the filth of pleasures; but come and have mercy, and do not turn away [your] face.”52 The poem gives voice to a sinner who realizes the vastness of his wickedness and impending condemnation. He puts his trust, however, in Christ’s unfathomable goodness and hopes that Christ will wait patiently for his repentance before his death so that he can be saved. Through the quotation of this excerpt and the understated interaction between Christ and the soul Dionysiou 65 seems to imply that even in Hades there might be hope for salvation.53

A striking aspect of such illustrations is that they focus intensely on the individual, rather than on the group. The implication is that in the dark cave of Hades not only is one forced to contemplate continuously the punishments to come, but also that one has to do so alone. In part this is also due to the function of some of these images. For example, Georgi R. Parpulov has convincingly argued that some of the miniatures in Dionysiou 65, including the depiction of Hades, served as the focus of private, devotional contemplation of posthumous judgment and the fate of the soul.54 The depiction of a single soul in Hades facilitates the viewer’s immediate identification with that soul.

Hades had, of course, a pagan lineage – the ancient god was brother to Zeus and Poseidon – a characteristic that it maintained as is evident in its depiction as a personification. Hades is most commonly represented as a stout, seminude man with an enormous body, a balding head, and a beard – all resembling Silenos, the companion and tutor to Dionysos.55 For example, in fol. 8v of the ninth-century Chludov Psalter (Mosq. 129) a seated Hades pulls toward himself one soul from a group of many, all represented as naked adults (Figure 13).56 In the same scene from the eleventh-century Bristol Psalter (Lond. Add. 40731, fol. 18r), Hades, this time not as corpulent as in Chludov, emerges from a dark cave, very similar to that of Dionysiou 65 (Figure 14).57 Hades is also present in images of the Raising of Lazaros, which sometimes accompanies Psalm 29 (30):4.58 In fol. 31v of the Theodore Psalter, the soul of Lazaros is escaping from Hades through a ray of light that leads to Christ (Figure 15). Hades clutches the souls that are in his bosom.

Emma Maayan Fanar has explained the particulars of his appearance, especially the importance of Hades’s corporeality and his accentuated belly, which indicate his sinful nature and his function as a container of souls.59 These features accord with textual descriptions of Hades as swallowing the dead60 and having an “all-devouring belly.”61 Byzantine artists, however, chose to illustrate Hades not as swallowing the souls but as holding them tightly, a detail that is of great importance. Hades as a terrifying figure clutching the souls in his bosom provides a great contrast to the venerable Abraham, who, in depictions of paradise, is peacefully surrounded by the souls of the saved.62 Furthermore, Hades’s forceful movements as he seizes or keeps hold of the souls underscore the notion that he is an utterly unpleasant place of involuntary confinement. Finally, the appearance of Hades would have triggered the well-attested Byzantine mistrust of pagan images.63

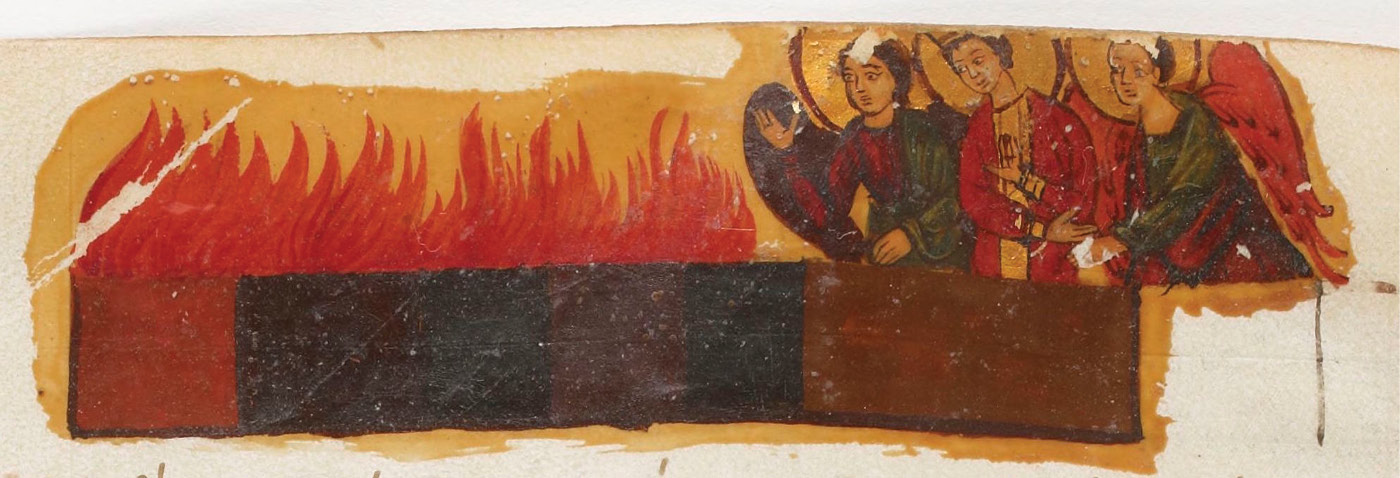

Depictions of Hades were never standardized, even when they were based on the same text.64 For example, Barlaam and Ioasaph describes a vision in which two angels show Prince Ioasaph paradise and Hades. The latter is a dark, odious, and gloomy place, filled with sorrow and tumult (θλίψεως δὲ καὶ ταραχῆς τὸ πᾶν ἐπεπλήρωτο). There is a fiery furnace and punishing worms. Vengeful demons stand nearby, and one can see some sinners burning pitiably in the fire.65 Miniatures depicting this scene again help visualize Hades’s desolation but they do so in differing ways.66 For example, in fol. 101r of the eleventh-century Athon. Iveron 463, Hades has three compartments filled with flames, skulls, bones, and worms (Figure 16).67 The stillness of the image emphasizes the sorrow rather than the din of the description. In other versions of this scene, such as in the fourteenth-century Paris. gr. 1128, fol. 156v, Ioasaph, flanked by the two angels, contemplates the flames coming up from a uniform rectangular space (Figure 17).

The variety of ways Hades is visualized in Byzantine art reflects the multiplicity of the textual accounts and indicates that no single version became ubiquitous. What unites all these depictions, however, is their emphasis on the dreadfulness of Hades. This is most evident in images of group punishments such as those in the Barlaam and Ioasaph manuscripts. It is conveyed in a subtler way in those where Hades becomes a menacing pagan figure, eager to smother the souls with his embrace. But it is the images of the dark cave where one sits bound and isolated, with only his or her thoughts, that were likely the most terrifying and the most potent.

Paradise

Like Hades, the visualization of paradise is never truly standardized.68 In some instances, the image is inspired by a specific text. In Barlaam and Ioasaph, for example, the prince Ioasaph visits the place of the “repose of the righteous,” which consists of a plain with exquisite vegetation, streams of water, couches prepared for the elect, and a brilliant city inhabited by singing angelic powers.69 In the illuminated versions of the story, the miniatures follow the text somewhat closely.70 For example, in fol. 100r of Iveron 463 Ioasaph and the two angels stand in the middle of lush vegetation (Figure 18). Behind them, an elaborate fountain covered with a ciborium stands in for the translucent waters. Ioasaph’s vision is directed at a couch flanked by two seraphim. The brilliant walled city of the description is absent, likely due to the lack of space.71 Such images, however, remain tied to the text they illustrate and never find wider distribution.

A rather unique image of paradise is found in the lower register of fol. 12r in Dionysiou 65 (see Figure 11). A monk bows in front of a luxuriously dressed angel who touches the monk’s head with his right hand. To the left of the angel stands another, holding a vessel. On the corresponding side to the right is an altar, covered by a ciborium, on which a book lays open. An inscription in the lower margin clarifies that the angel is anointing the monk: “oil of redemption in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”72 This image evidently depicts the monk’s admission to paradise but what is the exact meaning of the monk’s chrismation? Parpulov has connected it with a dream recounted in the Life of Antony the Younger (d. 865) in which the saint sees himself raised in the air. Two white-clad angels hold a golden vessel filled with water that a woman pours over Antony’s head three times.73 Stichel has suggested a parallel with the Life of Basil the Younger. Before Theodora begins her journey through the tollhouses, she is covered, at the instruction of Basil, with oil from jars (II.11).74 In neither case, however, is the anointed person received into heaven. Antony’s vision leads to a healing; Theodora is led by the angels to the first tollhouse.

Anointing the body with oil before burial is an ancient Christian custom derived from pagan and Jewish practices.75 Pseudo-Dionysios offers an elegant explanation of this custom by associating it with the baptismal chrismation.76 In the medieval period, the chrismation of the dead body, while it retained the connection with baptism, came to be associated with the forgiveness of sins. In a twelfth-century euchologion, the prayer that accompanies the rite asks God “to sanctify this oil, so that it becomes for those anointed by it a means for the remission of sins and deliverance from trespasses.”77 Oil that cleanses sins is a frequent element in the Life of Basil the Younger. In a vision, Gregory, the purported author of the vita, is taken by the protomartyr Stephen to the heavenly courtyard of Basil, where he sees “innumerable stone jars” containing spiritual oil that have been given to Basil by God as a reward for his toils. Basil uses it to purify sinners from the filth of their sins and to render them children of God (I.55).78 Theodora, whose sins would have led her to damnation were it not for Basil’s spiritual gold, appears in heaven as “anointed with divine oil and perfume” (II.47). Later in the vita, during his vision of the Last Judgment, Gregory sees a large group of people who were granted admission to the heavenly city. They used to be sinners, Gregory explains, but had repented sincerely. Gregory notices that their heads are “anointed with pure and gleaming oil” (V.34). This interpretation accords well with the accompanying inscription in Dionysiou 65 – “oil of redemption” – voiced, as it were, by the chrismating angel.

Another interesting detail in this image is that the monk appears to have just covered himself with the cloak. This is another indication of his new status. Already in the New Testament the paradisiacal existence is understood in terms of new clothing. For example, Paul asserts in 1 Corinthians 15:53 that “this perishable body must put on (ἐνδύσασθαι) imperishability, and this mortal body must put on immortality.” In 2 Corinthians 5:2, Paul again says: “For in this [earthly] tent we groan, longing to be clothed (ἐπενδύσασθαι) with our heavenly dwelling – if indeed, when we have taken it off we will not be found naked.” Thus the monk has been cleansed from his sins with oil, has put on imperishability, and is ready to participate in the heavenly feast.79

Images like that in Dionysiou 65 are, however, exceptional. The closest the Byzantines came to a universal image of paradise is Abraham’s bosom, either isolated or as part of the parable of the rich man and Lazaros in Luke 16:19–31.80 In the first category belongs fol. 24v of the Theodore Psalter (Figure 19). There Abraham sits on a throne with a soul, depicted as a child, on his lap. With his left hand Abraham points to a large tree with red fruit. On the other side of the tree there is a personification of a river.81 This image accompanies Psalm 22 (23):2, which has been interpreted as referring to paradise.82 The verdant nature, a significant aspect of the Garden of Eden as described in Genesis and of paradise in Byzantine reimaginations of it, often forms the background behind Abraham, as does the fire behind the rich man. In fol. 145v of Paris. gr. 74, Abraham, with Lazaros’s soul on his lap and others around him, again depicted as small children, sits surrounded by exotic trees (some of which bear fruit) and flowers. By contrast, the naked rich man is inside a fierce fire, next to which is a barren outcrop, a contrast that enhances the effect of the lushness of paradise (see Figure 12).83 Another interesting detail of this image is the empty throne, the so-called hetoimasia, which stands between Abraham and the rich man. In this instance the throne, devoid of the instruments of passion or any other objects, symbolizes the mystical presence of God in paradise and hints at the temporary nature of this state: After the Last Judgment, those in paradise will actually be able to see and commune with God.84

Starting in the eleventh century, however, Abraham’s bosom and the rich man are absorbed into depictions of the Last Judgment.85 They both appear in the earliest surviving examples, such as the two icons from Sinai, Paris. gr. 74, and Torcello (see Figures 6, 7, and 20). In one of the Sinai icons, Abraham occupies the lower of a two-story paradise; in the upper sits the Theotokos with angels and the Good Thief (Figure 21).86 This is a self-contained space, whose entrance is barred by a fiery seraph. The rich man, recognizable as such because he points to his mouth, finds himself on the opposite side of the icon, occupying the lowest left of the six compartments in hell. Thus, both Abraham’s bosom and the rich man become parts of larger compositions.

21. Paradise, detail of Figure 20, eleventh century, icon, Monastery of Saint Catherine’s, Sinai, Egypt

Angheben has again argued that these images and the weighing of the deeds, all of which are usually located in the lower registers of the compositions, depict not the final destination of the elect and the damned but rather the intermediate state.87 Taken literally, the parable of the rich man and Lazaros does refer to the intermediate state of souls. It states clearly that they both died and were buried. In vv. 27 and 28 the rich man seeks from Abraham to send Lazaros to his five brothers so that they might repent and avoid a punishment like his. Because the rich man’s brothers are still alive, it follows that the Last Judgment has not yet happened. However, the rich man recognizes both Abraham and Lazaros, and asks the former to “send Lazaros to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am in agony in these flames” (Luke 16:24), something that indicates a corporeal, postresurrection existence. To avoid this conundrum, some commentators, such as Gregory of Nyssa, suggest that the soul retains some characteristics of its body after death.88 But from early on, the parable was also connected to the aftermath of the Last Judgment. Epiphanios, bishop of Salamis (d. 403), considers the somatic references to be “a sign of the resurrection of the bodies.”89 Anastasios of Sinai, who also believes that the parable describes the final state, claims that Jesus told the story “symbolically” but “not as in actual fact.”90 Several other Late Antique and medieval authors argue that the parable describes the aftereffects of the Second Coming, some citing it as a proof that the resurrected will be able to recognize each other.91

This interpretive ambiguity, which far predates the appearance of the image, allows Abraham’s bosom to be multivalent and accounts for its appearance as part of Last Judgment compositions. Another factor is, once more, the relative absence of biblical information on the topic. The New or Heavenly Jerusalem, the ultimate destination of the saved, is described in Revelation 21:9–22:5 (see also Hebrews 12:22), but the Byzantines did not produce a definite iconographic type of it.92 Although the New Testament mentions the Kingdom numerous times and Jesus describes it in several parables, none of these literary images was picked by artists as a constant, universal illustration of post–Last Judgment heavenly bliss. It is likely that none had the immediacy and clarity of Abraham’s bosom, nor contrasted so easily with Hades. And while in Revelation the Kingdom is a social phenomenon, Abraham’s bosom is an individual, personal experience, one with which the viewer could identify.93 It is indicative of the image’s power that in Last Judgment scenes, when Abraham is joined by Isaac and Jacob, the two other patriarchs are also shown with souls in their bosom, although the pertinent biblical reference mentions the elect joining a feast with the patriarchs in the Kingdom (Matthew 8:11).94

The transposition of Abraham’s bosom and the rich man into scenes of Last Judgment is not a mere cut-and-paste affair. The fine balance of the original composition, as seen, for example, in Laur. Plut. VI.23, fol. 144r, is necessarily broken, although this was likely intentional (Figure 22). The dissociation of the two parts of the scene is meant to convey a new status of existence, one following Christ’s Second Coming. Whereas in most illustrations of the parable the interaction between Abraham and the rich man is evident in their gestures, in Last Judgment scenes, Abraham is utterly indifferent toward the rich man. Tellingly, in the Sinai icon, he turns his attention to his right, away from the general direction of the rich man, who is left floating, still asking for some respite from his torments, a fool who has yet to understand that hell is forever (see Figure 21).

However, the ambivalence makes Abraham’s bosom a liminal image in the context of the Last Judgment. This is evident in that almost invariably Abraham is surrounded by souls of the saved, while outside paradise’s door, the elect, this time clothed (and therefore embodied), are about to enter. This image, like the center of an endless cycle, depicts both the before and the after of the Last Judgment. Very much like the funeral hymns and some theological texts, Abraham’s bosom indicates that post–Last Judgment paradise is not ontologically different from the intermediate state, but rather the ultimate fulfillment of what the elect are already enjoying. In this instance they are also bringing along their physical bodies, something indicated by the group of those about to enter (they are usually headed by Peter). The idea is not novel. Anastasios of Sinai already, albeit talking about Hades, has claimed that the sinners residing in Hades sould arise to receive their bodies but return there once more.95

Conclusions

On the most basic level, images provide visualizations of the soul’s fate. Like texts, they use conventions – a garden, a cave, scales and balances – that would have been familiar to their viewers. Yet, even though they are nourished by the imagination of the texts, they are not mere illustrations. Rather, they often impart subtle theological points that require a serious engagement from the viewer. A miniature, such as that in fol. 93r of the Theodore Psalter, can operate simply as a depiction of Hades as a dark and gloomy space (see Figure 10). But the addition of the fire to the right of the soul invokes, as I have argued, an intermediate state in which the punishments have not yet been realized – an understanding that requires considerable theological sophistication. Furthermore, images can be clear and immediate, and, we assume, easier to understand and relate to than a lengthy written description. They also simplify and, at the same time, make more effective the message: The dizzying number of provisional judgment alternatives is replaced by the weighing of deeds, a simple and just process – although the figures of the black flying demons who carry scrolls make it no less terrifying than the textual descriptions.

Images of the afterlife also exist in multiple contexts. For example, the bosom of Abraham can signify both the intermediate state and the Kingdom, the paradisiacal glory after the Last Judgment. This is certainly due to the ambiguity of the texts, in which what the Kingdom looks like is, most often, not specified or even mentioned. But it also is a conscious choice meant to reflect continuity from the intermediate to the final state. What the righteous got a foretaste of, they enjoy fully with their bodies after the Last Judgment.96 Hades too is often represented in the same way. The pagan figure that grasps the souls greedily in the margins of psalters reappears in scenes of the Last Judgment receiving the damned (see Figure 20). But Hades, that is, the intermediate state, was also conceived as a personal and isolating experience. Abraham is surrounded by souls, but the rich man remains by himself, as do the souls in the Theodore Psalter and Dionysiou 65 (see Figures 10 and 11). Here the image seeks an immediate connection with the viewer, who can identify himself with the distressed soul, but the isolation enhances the idea of the terrible suffering. In contrast with paradise, where the joy is shared, Hades does not afford any such comfort.

And yet, despite the variations and the peculiarities, these images do tell a common story, one representative of what the Byzantines – or at least some of them – thought happened after death. Paradise can take many forms, but it is, in the end, the place of divine contentment, whose inhabitants receive a foretaste of the blessings to come. Hades, be it a furnace or a cave, is a place of terrible punishment. The Byzantines never quite agreed on the details, but then the details, however divergent, amount to essentially the same concepts.