Global African Diaspora communities experience overlapping forms of systemic oppression, economic exploitation, and marginalization such as physical and social segregation (Harris [1982] Reference Harris1993; Hamilton Reference Hamilton1988, Reference Hamilton2007). The seemingly penetrating reach of plantation domination seems to have prevented scholarly exploration of the social world of enslaved people in Saint-Domingue, perhaps because they were considered “socially dead” – personae non-grata – in most social, economic, and political terms (Patterson Reference Patterson1982). The Code Noir intended to restrict enslaved people’s everyday movements and activities, while the hierarchy of commandeurs and plantation managers readily used torture as punishment aimed to prevent rebellious behaviors. However, as agents of their own humanity, resistance, and social change, African Diaspora members formed social networks that used cultural and ideological tools in their collective liberation efforts (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2007: 31–33). Enslaved people had one free day per week; and the population imbalance between them and plantation personnel inadvertently created social environments that were under the direction and control of blacks themselves, wherein they shared space and time without much European surveillance. Africans’ ritual gatherings at burial sites, in churches, and at nighttime calenda assemblies served as free spaces where they could re-produce aspects of their religious cultures away from the observation of whites. Free spaces, or other monikers like communities of consciousness, safe havens, sequestered sites, or spatial reserves, are “small-scale settings within a community or movement that are removed from the direct control of dominant groups, are voluntarily participated in, and generate the cultural challenge that precedes or accompanies political mobilization” (Polletta Reference Polletta1999: 1). These liberated sites allowed African descendants to transform existing social institutions into sites for collective struggle and social change, where they could freely articulate their understandings of self and cultivate shared oppositional consciousness, collective identities, cultural formations, and political agendas (Evans and Boyte Reference Evans and Boyte1986; Couto Reference Couto1993; Fantasia and Hirsch Reference Fantasia, Hirsch, Johnston and Klandermans1995; Morris and Braine Reference Morris, Braine, Mansbridge and Morris2001). Various manifestations of African Diaspora communities’ free spaces have been crucibles for participants to assert declarations of freedom and liberty (Evans and Boyte Reference Evans and Boyte1986); heighten awareness of unequal social conditions and invoke historical memory of past resistance strategies (Covin Reference Covin1997); stake political claims for racial justice (Hayes Reference Hayes, Marable and Agard-Jones2008); and take part in civic activism, mutual aid, and community uplift (Hounmenou Reference Hounmenou2012).

This chapter argues that ritual free spaces in Saint-Domingue had several functions beyond cultivating an environment for cultural and spiritual expression, and that these gatherings allowed participants to: procure and employ sacred technologies to correct the imbalances of enslavement and reclaim personal and collective power; enhance oppositional consciousness through seditious speech; mobilize and establish social networks between enslaved people and maroons; revere women as important figures in ritual life; and build racial solidarity between African ethnic groups and enslaved and free blacks by binding each other to secrecy. Africa-inspired rituals flourished in free spaces over the course of two centuries, despite consistent repression from French Caribbean planters and failed attempts to Christianize newly arrived Africans (Peabody Reference Peabody2002). Africa-inspired rituals both reproduced and were the products of collective consciousness, identity construction, and participants’ respective cultural and religious homeland practices (Durkheim Reference Durkheim1912). Rituals are an often-repeated pattern of behavior set apart from other ways of acting, in such a way that aligns one with ultimate sources of power (Sewell Reference Sewell1996b: 252; Kane Reference Kane2011: 10–12). Participants are aware that the focus of the activities concern ultimate power, and therefore feel solidarity through mutual connection to the power source and its symbolic representations. Symbolic meanings involve pre-existing concepts in the mind that are communicated via historical memory, images, and materials objects. They are historically constituted and transformed through intergenerational usage (Kane Reference Kane2011: 10–12) – or, in the case of Saint-Domingue, through the constant replenishing of the Africa-born population through the transAtlantic slave trade. Though rituals are largely everyday occurrences, they can also punctuate major historical events and be incited by the collective excitement of revolutionary processes (Sewell Reference Sewell1996b), for example the Bwa Kayman ceremony that took place in August 1791 (see Chapter 8). In a non-sacred sense, rituals can be the hubs of forging political and cultural alliances that function as counterhegemonic structures. Through micro-level struggles common in colonial contact zones, disparate identity groups come together through identification with shared symbols, ideas, or goals that have a wider appeal to facilitate coordination and the exchange of ideas, strategies, and political goals, commitment to a cause, and identity development (Pratt Reference Pratt1992; Ansell Reference Ansell1997; Harris Reference Harris, Mansbridge and Morris2001; Kane Reference Kane2011).

Cultural activities such as rituals use material artifacts, and participants perform symbolic representations that give actors access to shared knowledge, values, and power, and enhance solidarity and mutual connection (Johnston Reference Johnston and Johnston2009; Kane Reference Kane2011: 10–12). Africa-inspired ritual gatherings in Saint-Domingue may have been strictly coordinated on ethnic lines in the early eighteenth century,1 but there was more than likely inter-ethnic collaboration and exchange to meet the needs of Africans who were not part of the dominant Bight of Benin or West Central African ethnic groups. Africans and African descendants from varying backgrounds or statuses were aware of free space ritual gatherings and sought to participate in them to connect to something culturally familiar that affirmed their humanity. Though they were outlawed by the Code Noir, planters largely ignored secret night-time dances, burials, and all-black church services and thus they happened frequently. These were opportunities for people to perform the sacred rites associated with their religious and cultural background, encounter and network with maroons or other enslaved people from nearby parishes, buy and sell ritual artifacts, and be audience to lay-preachers, priests, and prophets to further comprehend the state of their collective existence and ways of seeking retribution. Therefore, I argue that participation in free space ritual gatherings and/or using individualized sacred technologies produced and exchanged within those spaces not only helped mediate everyday issues, provide healing, and facilitate relationships with spirit beings, but also cultivated a growing oppositional consciousness aimed toward resisting enslavement and enacting collective rebellion.

Death was one of if not the leading everyday occurrence with which enslaved people contended using sacred means. Ritualists who had proficiency in healing, prophecy, assembling spiritual objects, and either inflicting death upon wrongdoers or protecting others from death were prominent figures within the enslaved community. Those believed to have supernatural powers traveled between plantations performing rituals and were mainly consulted by the enslaved, but in some instances even free people of color and whites utilized their services. These charismatic leaders claimed power from the non-material world, which in turn reinforced their power and influence within the plantation system. Similarly, African notions of political power and leadership, particularly in regions like the Bight of Benin and West Central Africa, were deeply connected to the spiritual realm. Rulers were ultimate sacred authorities with access to knowledge and power from the non-material world. As Chapter 1 discussed, kings and queens from the Bight of Benin and West Central Africa were keenly aware of their ability to wield spiritual power for political purposes. This provides a context for how enslaved people in Saint-Domingue would have conceptualized sacred ritual leaders like Pierre “Dom Pedro” or Jérôme Pôteau as fulfilling political roles that were of equal significance.

While most of the ritual leaders discussed in this chapter were men, it is important to note that women figured prominently in free space ritual practices as sacred authorities in keeping with West and West Central African gender roles. In the Dahomey Kingdom, women held important spiritual, political, and military positions as vodun ancestral deities, kpojito queen mothers who counseled kings, and “Amazon” soldiers who composed all-female regiments.2 West Central African women like Queen Njinga and Dona Beatriz wielded political and spiritual power to marshal defenses against the slave trade and civil war.3 On the other side of the Atlantic, gendered, racial, and class hierarchy relegated black women, especially those who were Africa-born, to the most labor-intensive work in the slavery-based political economy. Therefore, black women were marginally represented in spaces of formally recognized power in pre-revolutionary Saint-Domingue. However, ideas from Black/African Diaspora Studies, Sociology, and Anthropology help frame black women’s social positionality as the springboard for “bridge” leadership activism that is most potent in culturally-driven free spaces, such as ritual gatherings, and that connects rank-and-file grassroots efforts to larger movement organizing (Terborg-Penn Reference Terborg-Penn, Terborg-Penn, Harley and Rushing1996; Robnett Reference Robnett1997; Kuumba Reference Kuumba2002; Kuumba Reference Kuumba2006; Perry Reference Perry2009; Hounmenou Reference Hounmenou2012).

Bridge leaders occupy roles that defy components of traditionally recognized forms of leadership, such as holding titled positions within formal organizations. Instead, black women bridge leaders have mobility within non-hierarchical spaces and employ individualized interactive styles of mobilization and recruitment (Robnett Reference Robnett1997: 17–20). In the context of enslavement, women created social networks among themselves and others to ensure their survival (Terborg-Penn Reference Terborg-Penn, Terborg-Penn, Harley and Rushing1996: 223) and to coordinate liberatory actions. As Chapter 4 will show, adult women maroons in Saint-Domingue were more likely than men to have escaped with the assistance of a free person of color, a family member, or a relationship tie to another plantation, further indicating that women activated and maintained social networks beyond their immediate vicinity. This chapter will introduce readers to women like Brigitte Mackandal and Marie Catherine Kingué, whose skills with administering or healing poisonings made them highly regarded spiritual figures among enslaved people across several plantations. Later chapters of this book will highlight how enslaved women served as vaudoux queens, poison couriers, spies, protectors of sacred knowledge and secrets held by rebels, and mobilizers during the early Haitian Revolution insurgency. For example, Cécile Fatiman led the sacralizing ceremony for the August 1791 mass revolt, “Princess” Amethyste galvanized women fighters under the symbolism of vaudoux to help Boukman Dutty attack Le Cap, and other vaudoux queens discovered by Colonel Malenfant refused to identify their male rebel counterparts. Through the lens of black women’s bridge leadership, we might think of Africa-inspired sacred rituals as a collection of localized idioms and practices that formed cultural resistance against the imposition of Western Christian values and were a vehicle for organizing mobilization networks (Kuumba and Ajanaku Reference Kuumba and Ajanaku1998).

This chapter follows the thesis put forward in previous chapters, that the insurrectionary activities of the enslaved that gave birth to the Black Radical Tradition were ontologically grounded in the non-physical, sacred realm and exemplified aspects of the non-material world that were beyond the reach of racial capitalism’s early plantocractic manifestation. However, while Robinson argues that the violence that characterized the Black Radical Tradition was largely contained within enslaved black communities as a form of internal regulation – and this appears to be the case with some poisoning cases to be discussed below – much of the symbolic and physical violence perpetrated by enslaved people in Saint-Domingue targeted the owners and means of plantation production. More specifically, ritual practices helped to mediate and undermine the racialized subjugation of enslavement. African Diasporans’ re-creation of rituals was rooted in their sacred understandings of the world, and they included participants and leaders from varying backgrounds and statuses: Africa-born, colony-born creole, mixed-race, free, enslaved, and runaways. Further, the Africa-inspired sacred ritual practitioners incorporated symbols, performances, and artifacts from diverse cultural groups to cultivate shared meanings, solidarity, and oppositional consciousness. For example, herbalist and poisoner François Mackandal used calenda gatherings as spaces to invoke the history of racial domination in Saint-Domingue and to prophesy the formation of a future black-led state. As we will see in Chapter 8, Boukman Dutty employed religious symbols from various ethnic groups in organizing the Bwa Kayman ceremony in the days before leading the August 1791 insurrection. Other ritualists escaped enslavement, used herbal packets as poison and for healing purposes, organized underground networks and cultivated large followings, and advocated for rebellion and independence. Over time, African Diasporans’ collective consciousness became increasingly politicized and hostile toward their social conditions.

Poison

As Chapter 1 explains, many Africans in Saint-Domingue originated from societies in which imbalances, disharmonies, and disruptions in political, economic, and social spheres were managed and mediated through spiritual means. Conversely, the spiritual realm had the responsibility to serve as a check and balance against, and at times protector from, malevolent political and economic forces. African royal figures had the social and moral responsibility to rule with fairness, which their engagement in the slave trade directly countered. Especially in the Kongo lands, unethical behavior or the abuse of power could result in accusations of witchcraft, prompting ritualists to use nkisis as self-armaments and to conduct poison ordeals on order of the king. By the time African captives disembarked at Saint-Domingue’s ports, they had already lost the social, spiritual, and military battles against the encroachments of the transAtlantic slave trade; they had not, however, lost the battle to gain their freedom from enslavement itself. While they did not have the necessary structures, such as shrines, to fully re-create their religious systems, African Diasporans relied on free space gatherings to piece together and exchange elements of their rituals such as the affinities to spirit beings and sacred technologies. These spaces, and the rituals themselves, then reinforced a sense of opposition to enslavement by enacting inter- and intra-racial justice against those deemed as witches or slave trade participants (Thornton Reference Thompson2003; Paton Reference Paton2012). Poison was one tactic within enslaved people’s repertoire of contention, a collection of resistance actions that also included marronnage, that was useful in the struggle against slavery. Repertoire tactics can change over time, or be discarded or appropriated, according to how participants assess its effectiveness (Tilly Reference Tilly and Traugott1995; Traugott Reference Traugott1995; Taylor and Van Dyke Reference Taylor, Van Dyke, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004; Tilly Reference Tilly2006; Biggs Reference Biggs2013; della Porta Reference della Porta and Snow2013; Ring-Ramirez, Reynolds-Stenson, and Earl Reference Ring-Ramirez, Reynolds-Stenson and Earl2014). On the African continent, poison ordeals were associated with those in power, while in the Americas, the powerless adopted the poisoning tactic as a means of challenging inequality.

Enslaved ritualists used poison to disempower evildoers – members of the plantocracy and enslaved people suspected of cooperating with planters. When understood through the worldview of the enslaved population, spiritual activities like poisoning were not merely supernatural phenomena, they were critiques against the slave trade and racial slavery. The Atlantic slave trade was perhaps the most destructive force against African social, economic, and political formations (Rodney Reference Rodney1982); and enslavement in the Americas was deadliest in the sugar colonies, most prominently Saint-Domingue. One of the first recorded acts of using poison in Ayiti/Española against a slave owner was in 1530 when an enslaved woman was burned at the stake for attempting to kill her female enslaver.4 In 1723, a runaway leader named Colas Jambes Coupées and several of his accomplices were arrested in Limonade and executed as “sorcerers” who poisoned other blacks, terrorized white planters, and conspired to abolish the colony.5 Jambes Coupées, whose name suggests that one of his legs had been chopped off as punishment for repeated marronnage, was a predecessor to François Mackandal and other fugitive ritualists who cultivated a following of maroons and enslaved people. Chapter 7 will further explore the case of Jambes Coupées and marronnage in the early eighteenth century, an understudied period of Saint-Domingue’s history. But as this chapter will show, marronnage, the convergence of spiritual and political leadership, and the fear of white death due to poison and slave rebellion in the late eighteenth century came to be synonymous with only one name: Mackandal.

The Mackandal Affair

Mackandal was formerly enslaved on a northern plantation owned by Sieur Tellier and he often worked for Lenormand de Mezy in the Limbé district.6 Though one source identifies Mackandal as a Mesurade from the Windward Coast, an often-cited account from 1787, Extrait du Mercure de France: Makandal, Histoire Véritable, explains that Mackandal was brought to the colony at age 12 from the Upper Guinea region of West Africa, and that he was a “Mahommed,” or a Muslim, who had at least some Arabic linguistic competency.7 He was a distinctive character, with acquired skills and gifts in music, painting, sculpting, and herbal medicine. He attempted escape from enslavement several times before his final retreat into the mountains after losing a hand in a sugar mill and later tending to animals. Mackandal’s 18-year escape into the Limbé mountains is where he developed a strong following as a charismatic leader. He claimed himself to be immortal and was considered a prophet who secretly traversed plantations spanning the northern plain, from Fort Dauphin to Port-de-Paix, to speak during night-time assemblies or in an “open school,” as Moreau Saint-Méry described it. Early descriptions claim that Mackandal foretold the overthrow of enslavement, using different colored scarves as a metaphor to illustrate that the island once belonged to the “yellow” indigenous Americans, was under domination by white Europeans, but would soon be under the control of black Africans. Legend states that he aimed to rid the colony of whites by producing and distributing packets of poisonous mixtures that slaves could use to kill their owners and other enslaved people who were perceived as being in solidarity with whites.8 Mackandal infiltrated plantation systems by recruiting an underground network of people who were willing to transport packets of poisons, potions, or remedies. The goal of this campaign, as he communicated at the evening religious gatherings, was to overthrow enslavement by poisoning the white colonials.

Court documents from the Mackandal case associated the macandal packets with gris-gris from the “langue mennade” – a direct reference to the Mende linguistic origins of gris-gris amulets produced by Muslim marabouts in the Upper Guinea region, which Pierre Du Simitière also observed in Léogâne (Figure 2.5). These amulets were leather pouches that contained written scriptures from the Qur’an for protective purposes. Clients ported gris-gris underneath head wraps; around their necks, arms, waists, ankles or knees; they could be mounted over doors or placed under beds.9 In François’ case, he wore his gris-gris or macandal under a hat. He combined other artifacts and prayed over the materials with what seemed to be an Islamic incantation of “Alla[h], Alla[h],” which he claimed invoked the power and blessing of Jesus. These sacks were composed of human bones, nails, roots, communion bread, small crucifixes, and incense that were bound together in holy-water soaked cloth and twine.10 Individuals who had the expertise to compose the macandals and to invoke the spirits embedded in the sacks were considered to be of the first order, or the highest leadership rank among the community of ritualists. Each macandal was named after an individual who occupied a rank, which was delineated by knowing secret phrases or names of macandal producers. Those who gave the name of “Charlot” were of the first order, indicating women played indispensable roles within the network.11 The macandals could be used for strength, to attract love, to protect a person from a slave owner’s whip for committing marronnage, or to make the slave owner confused or the target of misfortune. After granting supplicants’ requests, the macandals had to be “re-charged” with food left for them to eat, an antecedent to the ways that contemporary Haitian Vodou practitioners sacrificially “feed” the lwa, or spirits.

The anonymous letter Relation d’une Conspiration Tramée par les Nègres estimates that as many as 30–40 whites, including women and children, and about 200–300 other enslaved people and animals were killed in the Mackandal conspiracy. A man named l’Éveillé agreed to poison his first owner, an upholsterer named Labadie, as well as the wife of a slave owner, and a surgeon from Limonade. In Le Cap, a merchant named Mongoubert and Mme. Lespes were both poisoned by black women who were convicted and condemned to death. Several other cases emerged: Marianne, the “chief poisoner” at Le Cap was connected to Mackandal through his wife Brigitte. Marianne, Jolicoeur, and Michel poisoned a hairdresser named Vatin, because he would not allow them to partake in a Sabbath dinner in his kitchen. A woman who previously lived with Jolicoeur poisoned the wife of Rodet and wanted to kill Jolicoeur’s enslaver, Millet. Henriette was accused and convicted of poisoning her female enslaver, Faveroles. Cupidon allegedly poisoned another black man named Apollon, as well as two Decourt women, and the owner himself. The following were also suspected of poison: black men and women belonging to M. Hiert, M. de la Cassaigne, Lady Paparet, Sieur Delan, and M. le Prieur. Thélémaque was condemned for poisoning with “vert-de-gris,” or the green leaf that was the container for poison and synonymous with macandals, that he hid in a dish of sprouts, resulting in nearly all the houseguests becoming sick.12 On April 8, 1758, three people, Samba, Colas, and Lafleur, were sentenced to death for their part in the poisonings that occurred in the northern department, and six slaves on a Limbé plantation were executed as punishment for allegations of poison.13

African-Atlantic Ethnic Solidarities

People associated with François Mackandal’s poison network represented various ethnicities originating from Senegambia, the Bight of Benin, and West Central Africa, suggesting his prophesy of black rule was not merely rhetoric but was based on the lived experience of building a diverse network of Africans and creoles – even free people of color – who collaborated based on shared principles and common practices. Mackandal’s speeches about restoring racial justice to the colony were particularly important in cultivating a sense of collective consciousness and solidarity among enslaved Africans of varying backgrounds. Solidarity can be thought of as a sense of loyalty, shared interest, and identification with a collective that enhances cohesion, and advances the idea that the well-being of a group is of such great importance that it will yield widespread participation in collective action (Fantasia Reference Fantasia1988; Gamson Reference Gamson, Morris and Mueller1992; Taylor and Whittier Reference Taylor, Whittier, Morris and Mueller1992; Hunt and Benford Reference Hunt, Benford, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004). François Mackandal was probably indeed a Mende-speaker of Senegambian or Sierra Leonean origin from the widespread Guinea region, as early sources have suggested, and had some familiarity with Islam – which had been the driving force of the Futa Jallon and Futa Tooro anti-slavery movements in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.14 Given the dire circumstances of enslavement, he collaborated with Africans of different ethnicities, such as his Kongolese associates Mayombé and Teyselo, whose fundamental worldviews were probably not incompatible with his own, particularly since Africans generally did not restrict their religious beliefs to fixed orthodoxies.15

Inter-cultural exchange within the sacred realm is a window through which we can begin to understand how collective consciousness and solidarity were forged within African descendants’ ritual life, Mackandal’s actions, and his network of Senegambian, Bight of Benin, and West Central African poisoners. The calenda, vaudoux, and other sects with which Mackandal was familiar shared commonalities of (1) levels of initiation, (2) herbal medicine practices, (3) spiritually charged objects, (4) divination and prophecy, and (5) anti-slavery sentiments. We might think of François Mackandal as an African-Atlantic “creole” from the Upper Guinea region whose early exposure to Islam in Africa, and later to West Central African practices in Saint-Domingue, provided him with socio-cultural and linguistic flexibility (Landers Reference Laguerre2010) to interact with Africans of varying backgrounds and assert a racially themed prophesy of impending upheaval. Sugar plantations in the northern plain tended to have more ethnic diversity than coffee plantations, which West Central Africans increasingly dominated midway through the eighteenth century.16 Some individuals, like Mackandal, would have participated in foreign rituals and had flexibility with sacred symbols from varying cultural groups, contributing to a wider appeal to the masses. Mackandal’s main associates, Teyselo and Mayombé, like him, originated from a region that was dominated by or had ongoing contact with monotheistic, Abrahamic religions – Christianity in the Kongo Kingdom and Islam in the Senegambia region. For example, Mackandal incorporated small crucifixes into his gris-gris artifacts to invoke blessings from Jesus, which would have appealed to Africans from the Kongo Kingdom who either were already baptized before their arrival in Saint-Domingue or who later embraced Christianity.

Enslaved women who worked within the domestic sphere acted as bridge leaders, constituting the main poison transporters.17 François Mackandal’s wife Brigitte seems to have been his main courier and was knowledgeable in the ritual process involved in creating macandals, stating “God knows what I do, God opens the eyes to those who ask for eyes.” Brigitte transported macandals between François and Marianne, a woman who was the “chief of the poisoners of Le Cap.” A Poulard woman named Assam, a domestic on the LaPlaine plantation in Acul, admitted to witnessing a Bambara man named Jean transport poison between several plantations using other women as couriers. The two women, Marie-Jeanne and Madeleine, were Niamba and Nagô, respectively. In Petit Anse, a Yoruba man named Hauron was accused of giving poison to other slaves. Assam’s testimony – combined with a spontaneous confession by an enslaved man named Medor in Fort Dauphin who admitted that the goal of the conspiracy was to collaborate with free people of color in destroying the colony so the enslaved could escape and be free – was what eventually exposed the network and led to François Mackandal’s arrest in November 1757.18 A number of women and three free people of color were among the 140 arrested for allegedly following Mackandal and providing arsenic to poison slave owners in support of slaves gaining manumission.

The Politics of Death

Those arrested in connection with the Mackandal affair were noted to have sung a song in Kreyol: “ouaïe, ouaïe, Mayangangué, zamis moir mourir, moi aller mourir, [… my friends are dying, I will die …] ouaïe, ouaïe, Mayangangué.”19 The words of the song reveal a sense of shared fate, and perhaps hopelessness, in response to the overwhelming volume of deaths among enslaved people. It might be argued, however, that death was not necessarily viewed as a condemnation, but as a path to freedom from bondage, a return to the homeland “Guinea,” and an entry into the spirit world where there was an opportunity to further influence the natural world. Mackandal’s wife, Brigitte, may have transitioned into the world of the lwa as Maman Brigitte, who has authority over cemeteries.20 Mackandal’s claim that he was immortal, and the imminence of death reflected in the song were possibly more than spiritual messages – they could have been threats to unleash the power of the dead on the living. If we consider that Mackandal was a Mende speaker, as his familiarity with gris-gris would suggest, it appears that aspects of Mende cosmology fit Mackandal’s profile. Within the Mende were decentralized structures, including societies based on ritual knowledge and the principles of justice, retribution, and secrecy. Mende leaders held the power of life and death and inflicted punishments on intruders or those who committed offenses against individuals or the whole community. Moreover, women were indispensable in Mende societies – even those that were male dominated – and were needed to mediate the human and spirit realm, which helps explain women’s centrality in Mackandal’s inner circle.21

After his initial arrest in November 1757, Mackandal escaped jail and was again free until he was later seized at a calenda ritual dance gathering at the Dufresne plantation in Limbé, then burned at the stake in Cap Français on January 20, 1758. Witnesses claimed that Mackandal’s body evaporated before the flames engulfed him and converted him into a mosquito, a plague of which he had earlier prophesied would bring destruction to the whites. Several African belief systems include notions of an afterlife, the transmigration of spirits from one physical entity to another, or the elevation of a human into a pantheon of revered spirits.22 Enslaved Africans’ reaction to Mackandal’s death, and the “ouaïe, ouaïe, Mayangangué” chant, can be considered part of a larger mortuary political stance, the “profound social meaning from the beliefs and practices associated with death … employed … [and] charged with cosmic importance – in struggles toward particular ends” (Brown Reference Brown2008: 5). Death was ubiquitous in Saint-Domingue – nearly half of incoming Africans perished within five years – as were attempts to prevent it, symbolize and commemorate it, or inflict it. African Diasporans’ belief in Mackandal’s immortality was not merely a sense of mourning and reverence, but one that connected private emotions and conceptions of death and the afterlife with wider concerns about enslavement and freedom. Moreover, the macandal packets that he and others assembled and sold contained fragments of human bones, suggesting the dead carried sacred powers that were important and effective for navigating the natural world.

Mackandal’s death supports the notion that funeral rituals involve both grieving and burying the dead, and provide time and space to address social, economic, and political issues (Tamason Reference Tamason1980). In pre-colonial African societies, especially those of the Bight of Benin and West Central Africa, spiritual leaders were revered and often held important political positions. Vincent Brown has argued that since enslaved ritualists “drew their most impressive power from the management of spirits and death, the prohibition [of ritual practices] amounted to a strategy to limit the prestige the enslaved could derive from association with the spirits of the dead, while maximizing the power of the colonial government’s ‘magic’” (Brown Reference Brown2008: 151). The ability to communicate with or marshal the spiritual energy of the dead, to protect oneself or others from death, or to inflict death translated to a type of community-endorsed political power that transcended colonial authority and therefore was a threat to the social order. Mackandal – and as we will see with several poisoners who followed him, organizers and participants of calenda ritual gatherings, and later the midwife Marie Catherine Kingué – negotiated matters of life and death and at times relayed messages condemning racial slavery, which elevated them to the level of political significance. Mackandal’s message regarding racial stratification, power, and control over land and resources infused into Africa-inspired rituals a politicized awareness of and oppositional attitude toward the oppressive colonial situation. This melding of the sacred and material worlds would not have been foreign to the bondspeople of Saint-Domingue, especially those of African origin from places like the Bight of Benin or the Loango Coast, where religion informed political and economic shifts and vice versa. The enslaved population likely would have welcomed such an articulation to facilitate comprehension of the new world into which they had been violently thrust, and as such revered Mackandal and his legacy.

Poison Post-Mackandal: 1760s–1780s

Mackandal’s case inspired fear among the colonists and was a watershed event that altered the structures of the colonial order as the courts developed ordinances and divisions of police to further control and repress the enslaved population (Sewell Reference Sewell and McDonald1996a). On April 7, 1758, the Council of Cap Français issued an ordinance regarding the policing of enslaved people in response to the Mackandal affair. Articles banned affranchis and enslaved people from making, selling, or distributing garde-corps or macandals, and issued a fine of 300 livres for any planter who allowed drumming or night gatherings on their property.23 Yet, these codes were not fully enforced and therefore did not stop people from using Africa-inspired technologies to empower themselves to solve personal and public problems associated with their oppression. Enslaved people in the northern plain viewed poisoning as a successful repertoire tactic, given the political impact of the François Mackandal affair on the colonial order and on witnesses to his execution, and they adopted the tactic for themselves. After the execution, Mackandal’s name became synonymous with certain religious leaders, dances, medicinal blends, and poisons most specifically.24 Poisoning allegations continued in the wake of Mackandal’s death, especially in northern Saint-Domingue, setting off a heightened repression of social and religious activities that were not explicitly Christian, such as using poisonous herbal blends and the calenda gatherings. Both enslaved and free black people were banned from practicing medicine in April 1764, which indicated a fear that free blacks with skills in medicinal practice and access to materials like arsenic used it to distribute to the enslaved and facilitate the poisoning of whites.25 Repression did not hinder Africans and African descendants from partaking in sacred ritual artifacts or attending ritual gatherings. However, rather than hand over poisoners to the courts as in the Mackandal case, political authorities relinquished the responsibility for punishing poisoners to slave owners themselves. As poisoning accusations continued in the 1760s and 1780s, enslavers increasingly used torturous means to obtain confessions, while the colonial government abdicated its protection of the enslaved.26

Across the northern plain, enslaved people and maroons were implicated as poisoners between the 1760s and 1780s, suggesting a diffusion of collective consciousness about Mackandal, the acts of marronnage and poison, and solidarity with the political ideas he represented. On April 2, 1766, a Kongolese man named Eustache was reported missing from Mr. Boyveau’s plantation in Dondon.27 Not only had Eustache escaped, he had begun to assume the name “Makandal” in recent years, which can be attributed to a sense of connection, solidarity, or shared identity the former felt toward François Mackandal. Perhaps Eustache “Makandal” had been initiated in François Mackandal’s network and was given his name before he escaped the Dondon plantation. Even if Eustache was not an initiate, he was more than likely aware of François Mackandal’s life and influence given the proximity of Dondon to Limbé, less than 50 kilometers, where Mackandal was formerly enslaved.

In May 1771, a group of enslaved people went to Cap Français to complain that their owner was torturing accused poisoners, burning five women and men alive and killing two of them.28 Another enslaved woman living with a white man, M. Beaufort, was accused of wanting to poison her owner, Madame Raulin, and going off as a maroon.29 In 1774, a young man was arrested and arsenic was found in his bag; a black pharmacist was implicated but was dead by the time of the judgment.30 Three enslaved domestics poisoned the manager at the Fleuriau plantation in Cul-de-Sac in 1776. A young boy warned the Fleuriau manager that his soup was poisoned, so they gave the soup to a dog and it died immediately. The three perpetrators admitted their actions and that they also poisoned M. Rasseteau, a former attorney; they were imprisoned and later burned alive.31 In 1777, near Cul-de-Sac, a man named Jacques was arrested and burned alive for poisoning one hundred of his owner Corbieres’ animals with arsenic over an eight-month span.32 That same year, another police ruling was issued prohibiting enslaved people from meeting during the day or at night under the pretense of weddings or funerals. The ruling expressly forbade drumming and singing, and, in 1780, African descendants were again banned from making or selling any medicinal substances.33 Colonists saw a connection between the ritual gatherings and poison, since these packets were often sold and distributed at the assemblies.

An alleged poisoner from Limonade, 33-year-old Marc Antoine Avalle, nicknamed “Kangal,” was questioned on June 30, 1780, and jailed in Le Cap. Among other vices, Antoine and his accomplices Bayome, Palidore, and Pierre were accused of poisoning 25 black people and 49 animals, including mules, cattle, and horses in 1776, and were imprisoned in Le Cap.34 Despite the 1780 ban on selling medicinal substances, a black apothecary was arrested in 1781 for selling a lethal drug to an enslaved person who used it to commit suicide – a common individualized response to the trauma of enslavement.35 An overseer at Cul-de-Sac caught a washerwoman attempting to dump a poisonous powder into his water in 1782.36 In 1784, a woman named Elizabeth “Zabeau” attempted to poison her owner with substances in his food and drink.37 On May 8, 1781, an advertisement was placed for a griffe creole named Jean-Baptiste, born in Ouanaminthe. Fifteen days before the advertisement was placed, Jean-Baptiste escaped a plantation owned by M. Lejeune in Plaisance, a parish near Limbé, and was reported as a “thief” and a macandal.38 In contrast to Eustache, the 1766 absconder who deliberately took the surname “Makandal,” Lejeune described Jean-Baptiste as a macandal to indicate the more general crime of poisoning. Perhaps Jean-Baptiste had killed or attempted to kill someone on the Lejeune plantation, then escaped to avoid inevitable punishment. The advertisement details could have indicated the beginning of a real conspiracy, because two enslaved people on Lejeune’s property allegedly killed his nephew later in 1783.39 The advertisement also implies a long-standing paranoia about poison on the Lejeune property. Jean-Baptiste likely escaped from the same coffee plantation that became the center of controversy in March 1788, when the plantation owner’s son, Nicolas Lejeune, nearly tortured to death two enslaved women named Zabeth and Marie Rose and executed four others. Lejeune accused the victims of poisoning nearly 500 bondspeople on the Plaisance plantation over the course of 25 years. Lejeune so brutally tortured the two women that 14 other enslaved Africans strategically used provisions of the 1784 Code Noir to file charges against him in Le Cap.40 Laws to prevent assemblies and to keep black people from possessing medicinal and other ritual items were an ineffective means of repression against poisonings, however the torture of Zabeth and Marie Rose may have signaled to ritualists that poison as an individualized act of resistance was no longer an effective repertoire tactic. Enslaved and maroon ritualists continued to utilize sacred technologies for individual usage, but they also relied on organizing networks to inspire broader forms of insurgency.

Communities of Rebellion

In addition to Mackandal, rebels like Pierre “Dom Pedro,” Télémaque, and Jérôme dit Pôteau communicated to their followers the injustice of enslavement and promoted ideas about freedom and independence. Ritual participants and leaders, suspected poisoners, and midwives escaped enslavement and used marronnage to organize other enslaved people. They preached liberation to audiences on plantation outskirts to address the unethical conventions of enslavement in Saint-Domingue, especially since West Central Africans and those who took part in their ritual technologies were keenly averse to exploitative, abusive practices, which they would have viewed as witchcraft. Seditious speech to incite or inspire rebellion against Saint-Domingue’s racial conditions occurred within free spaces and served as a discourse of contention. It raised oppositional consciousness – which arises from a group’s experiences with systems of domination, overlapping institutions, values, and ideas that support the exploitation and powerless of one group in favor of another – and enhanced critical comprehension about the social conditions enslaved people faced in order to develop the tools to combat those conditions while taking part in free space activities (Morris Reference Morris, Morris and Mueller1992; Morris and Braine Reference Morris, Braine, Mansbridge and Morris2001). As several cases will show, ritual rebels expressed sedition by encouraging other slaves to resist, challenging white authority, and even threatening whites – all verbal acts that disrupted the prevailing social interaction order that demanded black subservience (Tyler Reference Tyler2018) and that would have been met with dire punishments.

“Dom Pedro”

The contemporary petwo pantheon of spirits in Haitian Vodou is typically attributed to the petro dances observed by Moreau de Saint-Méry, who distinguished the petro from the vaudoux ritual dance, stating that the former was more dangerous, powerful, and had the potential to foment rebellion among the enslaved population. Nearly two centuries later, Haitian anthropologist Jean Price-Mars (Reference Price-Mars1938) witnessed a petwo ceremony and linked it to the Lemba society of West Central Africa. Recently uncovered archival material about Pierre “Dom Pedro,” the originator of the petro dance, seem to support Price-Mars’ thesis that Dom Pedro and members of this spiritual sect were connected to the Lemba of the eighteenth century. The Lemba society was a closed but vast network of initiates and family members who regulated local markets in the region and practiced healing rituals to counterbalance the negative effects that the slave trade inflicted upon West Central African communities. The Lemba emphasized fairness and justice, and imposed harsh punishments on those who violated their peacekeeping code of ethics. As the transAtlantic slave trade weakened the power of coastal kingdoms and their justice systems, public nkisi shrines became increasingly “concerned with adjudicatory and retaliatory functions” to mediate societal imbalances.41 In Saint-Domingue’s colonial period, the petro sect was associated with thievery and other malevolent acts, which may have been the result of deported Lemba affiliates attempting to rectify the extreme level of exploitation and injustice they experienced as enslaved people.

Pierre “Dom Pedro” emerged as a leader among enslaved blacks living in and around Petit-Goâve by introducing them to a new dance, one that was similar to the established vaudoux dance but adhered to a faster and more intense drumbeat. Participants added crushed gunpowder to their rum to induce a highly intoxicated, frenzied state that was said to have killed some who drank it. As Chapter 1 indicated, items like rum and gunpowder were traded for African captives on the coasts of the continent and were assumed to hold the essence of slave trade victims, thus enhancing spiritual power of ritualists in Saint-Domingue. Pedro’s followers quickly gained the reputation of being the most powerful and dangerous ritual community in the colony; members had the ability to see beyond the physical realm and used herbalism, poison, and secrecy to exact revenge on whites, uninitiated blacks, and animals. An account from an initiate describes a series of tests he had to undergo to prove loyalty to the group. Of importance was his ability to demonstrate strength under torture, discretion in keeping secrets, and willingness to do such oppositional acts as lying, stealing, or inflicting harm on humans or animals.42 Another member was asked to hold a piece of hot coal in his hand, seemingly to test if his spirit was capable of absorbing rage, symbolized by the heat, until an appropriate time for it to be released was reached.43 These acts required of initiates might also be seen as examples of Lemba ritual purifications to alleviate symptoms of the human-inflicted evils of slavery.44 Authorities arrested 42 people, including some mulâtres and women, in connection with the Dom Pedro campaign. By 1773, several of them were still imprisoned in the jails of Petit Goâve, although it is possible that some escaped after an earthquake on June 3, 1770 destroyed much of the town and Port-au-Prince. In his wake, Dom Pedro became a title applied to any person who was known as a ritual leader who used sorcery to inflict harm and often carried a large stick and a whip.45

It was previously believed that Pierre had taken the name Don Pedro, suggesting he was a runaway from Spanish Santo Domingo, but recently discovered documents name him as Dom Pedro, a more common name from the Portuguese-influenced Kongo Kingdom. Between 1768 and 1769, Judge Joseph Ferrand de Beaudiere investigated Dom Pedro for traveling to several plantations in Petit Goâve, Jacmel, and Léogâne and spreading messages of freedom, rebellion, and independence from slave owners. Pedro’s campaign for liberation would have amounted to sedition according to the high courts, and seems aligned with Lemba ethics that deemed slavery and the slave trade as a societal ill. Pedro’s ritual performances, thought of as crude tricks by investigators, would have denoted spiritual efficacy that contributed to his growing following. De Beaudiere’s notes indicate a small uprising of sorts, wherein Pedro subverted plantation power structures by assuring the enslaved that they would soon be free and encouraging them to turn the whip on commandeurs who attempted to uphold plantation violence. He then instructed the commandeurs to stop using the whip on the other enslaved people under their supervision and assured them that there would be no punishment from their owners. In advocating the use of the whip against commandeurs as retribution for their treatment of the enslaved, Pedro promoted a sense of reciprocal or “horizontal” justice and the exercise of force – these were hallmark principles of Lemba society. This type of contestation against existing power relations openly vocalized a sense of discontentment with the violent punishments associated with slavery that bondspeople typically could only have shared in private spaces. In exchange for spiritual and physical protection from slavers’ retribution, Pedro imposed financial charges on his initiates. Similarly, clients customarily paid fees to Lemba priests for their ritual services of initiation, healing, or spiritual consecration.46

Pierre Dom Pedro, and his followers, would have understood enslavement in Saint-Domingue within the realm of greed, evil, and witchcraft – issues that needed to be rectified with both spiritual and material actions.47 His Kongolese understanding of slavery could not abide the unjust practices that were so regular in Saint-Domingue. Dom Pedro’s seditious resistance to the whip was both a literal repudiation of the non-ethical use of violence in slavery and served as symbol to instigate bondspeople’s reclamation of power from those who sought to maintain slavery. Further, Pierre Dom Pedro’s declarations of himself as “free” were probably not just in relation to slavery in Saint-Domingue; he may have been a freeborn Lemba priest or market trader who, in keeping with local custom, should have been protected from the slave trade. Indeed, in Portuguese Angola the honorific title “Dom” was usually reserved for the political elite, but was also used for freeborn commoners to indicate their status.48 Pierre Dom Pedro’s stance against slavery may indicate an association with longstanding Kongolese efforts to protect the local population from the encroaching transAtlantic slave trade and balanced practices related to enslaved laborers. These contributions were important antecedents to the early Haitian Revolution negotiations, when rebels sought more humane work conditions such as the abolition of the whip and modified work schedules.49

The Dom Pedro sect arrived in Saint-Domingue not long after the King of Kongo, Pedro V, failed to seize power from Alvaro XI, whose allegiance with local leaders who had large slave armies helps to explain the likely enslavement of Pedro V’s supporters.50 Though there is not yet clarity on Pedro V’s relationship with the Lemba network, or his political and philosophical stances on the slave trade, further evidence from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean might shed light on the political implications of Pedro V’s short reign. The actions of Pierre Dom Pedro and his followers critiqued the nature of enslavement and advocated for others to overturn the power imbalances embedded in everyday colonial life. Although these enslaved rebels could no longer alter social, economic, or political realities in their homelands, they attempted to affect change in Saint-Domingue by enacting their own brand of justice against the French colonial plantocracy through poisonings, theft, spiritual prophecy of impending revolt, and retributive violence. The Dom Pedro campaign may be a small window into the nature of the Kongo civil wars, as well as a new way to understand how African events and consciousness shaped anti-slavery positions and activities in the Atlantic world.

In December 1781, three months after Pedro V’s remaining allies were driven out of São Salvador and the slave trade from West Central Africa increased, another “Dom Pedro” surfaced in Saint-Domingue and gained the attention of local authorities; this man was referred to as Sim dit Dompete.51 Sim’s name may indicate association with the Kongolese simbi nature spirits that controlled rain, and fertility, and that are recognized contemporarily as part of the Haitian petwo rite. In West Central Africa, the simbi spirits protected rocks, rivers, pools, and waterfalls, and were ruled by the mother spirit, Bunzi. The Bunzi priest had the critical responsibility for the spiritual installation of the King of Loango.52 Sim Dompete was a runaway from Cayes and an alleged animal poisoner, perhaps using his ritual knowledge to enact poison ordeals. He was so well known in Nippes, southwest of Port-au-Prince, that members of the maréchaussée targeted him for capture as they were eager to demonstrate their disdain for Africans and African-based culture. During the expedition, the freemen hid in the woods for days until they saw Sim pass by carrying a sword, a white hat under his arm, and a macoute. Along the Loango coastlands, the makute was made of a piece of palm raffia cloth about the size of a large handkerchief; it was traded as currency and often used for ritual healing purposes.53 As Sim appeared, the hunters attacked and they all fought for hours while Sim attempted to reach into the macoute to open its contents. The hunters believed he had a gun, and eventually shot and beheaded Sim then took his sword and bag. The macoute contained several small packets covered with red, blue, and white cloth and animal skin, with feathers, bones, and glass sticking from the bags. There were also black tree seeds and a small piece of white wax.54 These contents match the description of the garde-corps, or “bodyguards” that Mackandal and ritualists in Marmelade created and distributed.55 During the Haitian Revolution, Colonel Charles Malenfant also reported discovering macoute bags on the bodies of the few rebels he killed. The sacks contained writings in Arabic, which were probably Qur’anic prayers used in protective gris-gris amulets.56

West and West Central African ritualists like Mackandal, Dom Pedro, and Sim Dompete used their status as spiritual authorities to exercise political power among Saint-Domingue’s enslaved communities and utilized a range of sacred practices, including poison, to bring about change in their immediate social world. Enslaved blacks and maroons produced and exchanged ritual artifacts clandestinely while people performed their work-related tasks – such as the female domestic laborers who delivered macandals – as well as in free spaces to arm and empower themselves against the everyday forms of violence embedded in the slave society. Gris-gris, macandals, ouangas, which were charms categorically close to nkisis, and macoutes were all small sacks containing varying materials that were prayed over and charged with comporting the spirits of non-human entities to grant the user’s requests. These requests usually sought to alter slave owners’ behavior – most commonly to prevent punishment for marronnage and for owners to grant emancipation after death from poison. Pouches of poison and other spiritual assemblages aided enslaved people, no matter their ethnicity of origin, in redressing power differentials in their everyday lives.

Not only did ritual leaders leverage sacred objects for individual usage, they also used marronnage to organize calendas, which were simultaneously spiritual and militaristic gatherings, and to propagate notions of liberation. Mayombo sticks empowered carriers, mostly men, to fight with enhanced spiritual power. Higher-ranking calenda fighters and organizers held more sacred power and were most associated with insubordination. The sacred packets, fighting sticks, and garde-corps were “popular” culture artifacts that represented the “raw materials” for free space ritual performances. Used by most enslaved people in the colony, sacred artifacts and those who produced them derived meaning from their African origins to shape individuals’ responses to the colonial situation and guide social actions (Harris Reference Harris, Mansbridge and Morris2001; Johnston Reference Johnston and Johnston2009).57 Songs such as those sung by François Mackandal “ouaïe, ouaïe, Mayangangué” and the KiKongo “Eh! Eh! Bomba, hen! hen!” chant were other forms of cultural artifacts that operated as discourses of contention, or ways of communicating collective understandings and visions for social transformation through dialogue (Hall Reference Hall, Howard and Becker1990; Steinberg Reference Steinberg1999; Kane Reference Kane2000; Pettinger Reference Pettinger, Paton and Forde2012). The ritual songs and chants helped build solidarity by encoding information about the power of spirits to end slavery and, later, were part of the unfolding of the revolutionary process itself (Sewell Reference Sewell1996b; Johnston Reference Johnston and Johnston2009).

Calendas

Enslaved Africans’ collective and oppositional consciousness was already shaped and politicized by their experiences of war, capture, and commodification in Africa and during the Middle Passage. Rebels leveraged free spaces, such as calenda dances, designated for cultural and political practices as organizational structures to enhance the meanings enslaved people assigned to their conditions in a racially organized society and further develop insurgent potential. Maroons were central figures in cultivating these spaces and in recruiting participants from various plantations. Ritual gatherings were among the only social spaces under the control of enslaved people, making them what social movement scholars call indigenous organizational resources that draw on collective consciousness and do the micromobilization work of insurgency (McAdam [1982] Reference McAdam1999; Morris Reference Morris1984; Morris and Mueller Reference Morris, Morris and Mueller1992). These free spaces were appropriated and politicized not merely due to the overlap of religion and politics in various African societies, but because of the powerful symbols invoked by connecting sacred understandings to wider issues (Harris Reference Harris, Mansbridge and Morris2001). Moments of acute social, economic, or political crisis, for example the Kongo civil wars in the case of Dom Pedro, can influence those affected and transform existing structures, cultural and religious practices, and identities into vehicles for change (Fantasia and Hirsch Reference Fantasia, Hirsch, Johnston and Klandermans1995). Saint-Domingue’s black cultural “toolkit” included ritual objects, spirit embodiment, song, dance, and martial arts that were both sacred and political, and animated mobilization (Pattillo-McCoy Reference Pattillo-McCoy1998).

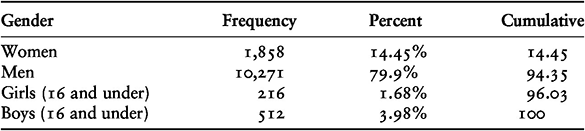

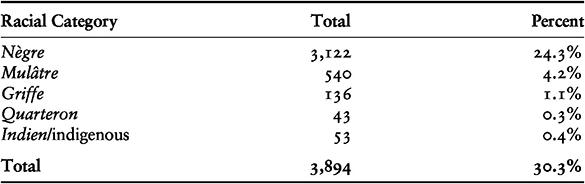

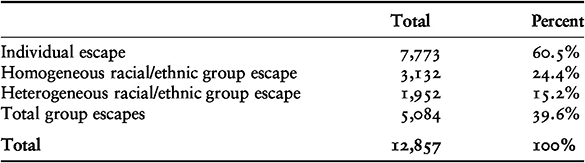

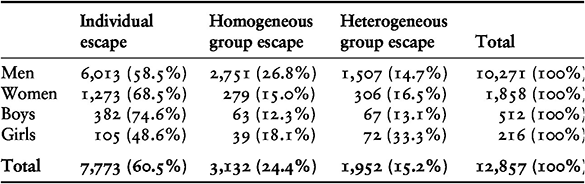

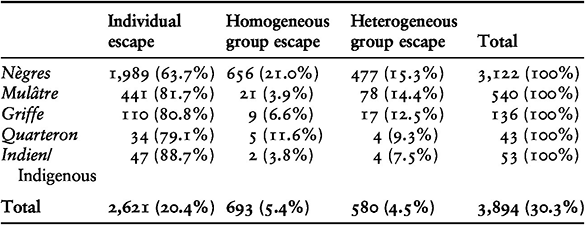

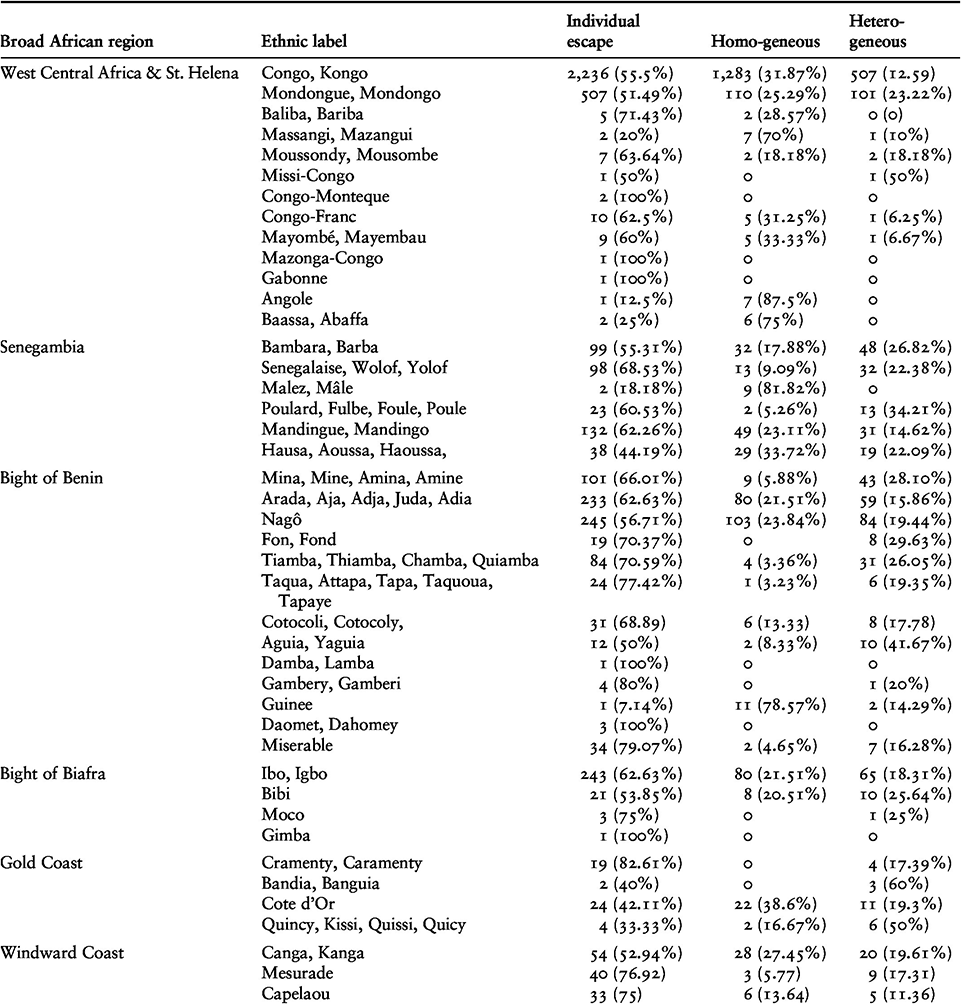

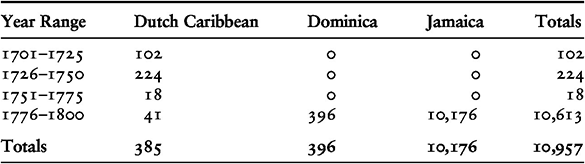

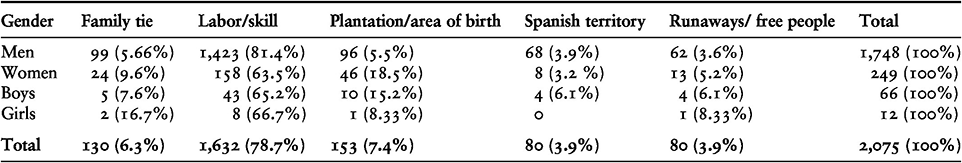

Calenda ritual gatherings held in the 1760s and 1780s were likely the product of an influx in the number of West Central Africans brought to Saint-Domingue’s ports, which nearly doubled between 1781 and 1790 (Table 1.2) due to resumed fighting in the Kongo Kingdom between Pedro V, who attempted a coup in the early 1760s, and forces supporting his opponent Alvaro XI. Prisoners of war were sold through the Loango ports that were most used by the French. Former soldiers would have been trained in the sacred martial art tradition using mayombo sticks that Moreau de Saint-Méry described and which were seen in Cap Français in 1785. Kongolese fighters often preferred these types of personal weapons to larger bayonets for closer combat, which stood in contrast to European fighting styles. Calendas might then be considered training grounds that reinforced spiritual and military organizational knowledge that former Kongo civil war soldiers brought with them to Saint-Domingue.58 Participants in the calendas imbued material culture artifacts with spiritual power to enhance their effectiveness as self-protective armaments. Further, training in combat combined with declarations of liberation and the power of Africans and African descendants indicated their anticipation of and preparation for events that would eventually lead to the dismantling of the enslavement system.

Sacred Martial Arts

In northern Saint-Domingue and other French Caribbean colonies, kalendas, or calendas, were not just ritual dances of enslaved people, they also included African martial art-styled stick fighting practices similar to West Central African kilundus or kilombos.59 Stick and machete fighting traditions existed in the Bight of Biafra, West Central Africa, and the Bight of Benin, and they were used as mechanisms for warfare training, rites of passage, and, in the case of Dahomey, to train “Amazon” women fighters.60 Enslaved women were not known to have participated in stick fighting, but T. J. Desch-Obi claims that “unarmed pugilism and head butts … were gendered female in Saint-Domingue.”61 African kings and high-ranking soldiers commanded kilombos, militaristic communities that spread throughout West Central Africa in the seventeenth century, particularly in preparation for warfare. These fighters relied on hand-to-hand combat, and constantly performed mock battles, drills and other training exercises, and war dances to prepare for impending conflict. The war dances, as well as the movements associated with fighting styles during non-combative ritualistic gatherings, invoked spiritual meanings and reflected West Central African sacred understandings of the cosmos. Ancient ritual specialists performed specific movements like inverted kicks to invoke the power of ancestors who resided on the opposite side of the kalunga, the body of water that separated the worlds of the living and the dead.62 With sacred power imbued in physical movements, the martial arts could be used to heal the living as well as “helping bondsmen’s souls make return journeys across the kalunga.” For example, the Mounsoundi (Musundi or Mousombe) of Kongo were noted for their association with stick fighting, as well as the belief in Africans’ ability to fly away from enslavement back to their homeland.63 A song that likely originates from the revolutionary era indicates the legacy of militaristic cultures of this West Central African ethnic group in Saint-Domingue:

Overlap between sacred knowledge and military skills continued across the Atlantic via the collective memory of slave trade captives and resulted in similar practices emerging in pre-revolutionary Saint-Domingue.

Moreau de Saint-Méry described calenda stick fighting as serious conflicts, usually occurring over jealousy or an offense to one’s sense of honor, self-image, or self-worth. It was not uncommon for combatants to strike each other with forceful head blows that drew blood. The fights began with a salute and an oath, wherein both participants wet their fingers with saliva then touched the ground, bringing their fingers back to their mouths, then pounding their chests while looking toward the skies. Saint-Méry was both impressed and entertained by the dexterity with which fighters handled their “murderous sticks,” likening the fighting contest to fencing. Each delivered their blows quickly, using their sticks to defend against the other’s and to issue offensive strikes. Possession of a fighting stick was a symbol of honor among participants, and the more decorated sticks were highly valued because of their spiritual power. The fighting sticks, called mayombo, were filled with a limestone-based powder, maman-bila, and were sold along with red and black seeds called poto. Nails inserted into the blunt end of the stick for additional force indicated one’s position of leadership within the closed network of fighters. These materials match the description of elements used in West Central African nkisi bags and they were used to imbue the sticks with sacred power that would protect users against opponents who were not similarly armed.65 In addition to mayombo sticks, other weapons, such as machetes and blunt metal-headed clubs, were used during the calenda gatherings. While Moreau de Saint-Méry described armed conflicts at calenda events as legitimate fights, he simultaneously dismissed them as a form of play associated with slave dances, void of any necessary training or potential usefulness in military combat.66 The assemblies were not merely ritual performance activities; the sacred influence on expertise in hand-to-hand combat and non-firearm weapons gleaned from calendas was a significant contribution to success during the early phases of the Haitian Revolution uprisings.67

Police rulings prohibited assemblies of enslaved people during the day or night, and drum playing and singing were forbidden in the wake of the Mackandal affair, but calendas were continually held in the north especially around the dates of Catholic celebrations.68 On August 5, 1758, a plantation manager in Bois l’Anse, a section of Limonade, was fined 300 livres for allowing a calenda to take place at Habitation Carbon on July 23.69 This calenda was held three days before the Catholic recognition of Sainte Anne and Saint James the Greater on July 25–26 in Limonade. These dates correspond to a contemporary popular pilgrimage for Sèn Jak (Saint James), the Haitian Vodou-Catholic manifestation of Ogou Feray, in Plaine du Nord just east of Limonade.70 While Ogou (or Ogun) is the Yoruba god of war and iron, Saint James was the de facto patron saint of the Kongo Kingdom. Saint James celebrations in sixteenth-century Kongo included offerings and petitions to the saints, dancing and spirit embodiment, and decoration of the pilgrimage space. Ritual martial art performances were also witnessed in eighteenth-century Central Africa, and were often held to initiate newcomers on the Saint James feast day or prior to war.71 We might then presume that activities at the 1758 calenda were militaristic in nature, revering spirits that presided over war – Ogou and Saint James – and creating solidarity among the participants by combining the spirits of the Nagô/Yorubas and the Kongolese.

A 1785 report from the Chamber of Agriculture described the calenda and mayombo sticks as a pervasive problem that encouraged the growing hostility among the enslaved population. Cap Français was deemed to be a troublesome environment where blacks openly displayed acts of insubordination and outright animosity toward whites:

many negroes in Le Cap never go out without a large stick, and on holidays you find 2,000 of them gathered at La Providence, La Fossette, and Petit Carénage all armed with sticks, drinking rum, and doing the kalinda. The police do nothing to prevent these parties and they never end without quarrels and fighting.72

That same source made several claims of acts of aggression – a group of blacks blocked a white couple from the sidewalk along Rue Espagnole, telling them “Motherfucker, if it was one hour later, you wouldn’t dare say anything. You’d step aside yourself.” Another man chastised a group of blacks for making too much noise in front of his home and was met with the response that “the streets belonged to the king” accompanied by a large rock being thrown at him, barely missing his face.73 This verbal and potential physical assault against a white person was a clear violation of colonial codes and could have resulted in the execution of the agitator. Based on these reports and what is known about the nature of calendas, we can speculate that the calendas reinforced an awareness among enslaved people that they had the capability – politically, spiritually, and militarily – to overturn Saint-Domingue’s racialized power dynamics at will. This account indicates that the open contempt toward whites from enslaved blacks in Le Cap stemmed from a sense that the city belonged to them given the population imbalance between blacks and whites, and especially at night and on the weekends when enslaved people from throughout the northern plain descended there for celebrations and to trade food at the weekly market. The diverse population of Le Cap, including the growing community of well-to-do affranchis, gens du couleur, as well as runaways from other parishes, may have signified to the enslaved that freedom, status, and power were fluid categories that could and did change quickly. The ability to congregate among themselves somewhat freely provided space to enhance oppositional consciousness and act on that consciousness in ways that countered common mores, behavioral expectations, and power structures. The ethos of these calenda gatherings involved sacred understandings of fighting and weaponry, which connected enslaved people to a range of African cultural symbols and emboldened them to disrupt the colonial order that rendered them powerless.

Maroons Mobilizing the Calenda

While most calenda participants were enslaved people, several were runaway maroons. Fugitive slaves could move about with more latitude than most enslaved laborers, which allowed them to visit different plantations or parishes and effectively recruit and mobilize participants for ritual gatherings. In 1765, a special division of the rural police was established with specific orders to eradicate marronnage and calendas, indicating authorities had some sense that the two forms of enslaved Africans’ agency were interrelated, yet the implementation of this structural constraint on ritual life did not stymie their activities.74 Several calenda attendees, dancers, and musicians appeared in Les Affiches américaines (LAA) runaway advertisements, exemplifying an intersection between ritualism and efforts to self-liberate. In April 1766, a 25-year-old mulâtre who claimed to be free, but was owned by the Pailleterie plantation, was witnessed going from plantation to plantation in Trou under the pretense of being invited to (or inviting people to) a calenda.75 Though the advertisement does not provide enough information about the specific conversations and actions taken by this escapee during his eight days of marronnage, it is likely that he was engaging in some form of seditious speech against slavery given his proclamations of freedom and the political, spiritual, and militaristic nature of the calendas. While most of Saint-Domingue’s mixed-race population were part of the landed gens du couleur, some were indeed enslaved, but used skin color to attempt to elevate their status in society. Conversely, this runaway used his skin color to pass as free, not to advance the political and economic interests of the gens du couleur, but to attempt to organize the bondspeople in his immediate vicinity. On September 16, 1767, an advertisement appeared for a 20–22-year-old Nagô male named Auguste with the branding “Lebon.” Auguste was described as a merchant from Le Cap who enjoyed calendas, and who used his ability to travel as a merchant to his advantage in escaping.76 Nagôs originated from the Bight of Benin region, so this example further counters accounts by early writers that African ethnic groups intentionally segregated themselves and antagonized each other. A Kongo man named Jolicoeur was described in a June 1768 advertisement after escaping Cassaigne Lanusse’s plantation in Limbé. He was described as a good enough drummer, possibly meaning he was a key musician in ritual gatherings.77 Another musician, named Pompée, who played the banza very well, escaped in November 1772 from Fort Dauphin and was seen near Ouanaminthe claiming to be free.78

In April 1782, an unnamed commandeur was accused of holding night-time assemblies and spreading superstition, for which he was condemned to a public whipping before being returned to his owner:

Declaration of the Council of Le Cap, confirming a Sentence of the Criminal Judge of the same Town, declaring a Negro, Commander, duly accomplished and convicted of having held nocturnal assemblies, and of having used superstitions and prestige to abuse the credulity of the other negroes, and to try to draw from them money; For the reparation of which he would have been condemned to the whip on the Place du Marche of Clugny; Then handed over to his master.

Commandeurs were responsible for maintaining productivity and order among the atelier work gangs. They also, at times, had to bear the weight of executing punishments for transgressions, which put them in a position of authority above the enslaved laborers. The announcement described the meetings as indulgent of the superstitions of the blacks, and as providing a way for this commandeur to use his position to swindle money from believers.79 However, this is just one of several examples of commandeurs and other relatively privileged slaves operating in collusion with the field workers. Commandeurs like the one above had two faces, one for whites and one for blacks, and likely used their relative privilege among enslaved workers to invite people from different plantations and to organize rebellious activities.

In December 1784, an advertisement was published for an escaped coachman, who may have been a calenda organizer:

Cahouet, Mesurade, coachman, age 24 to 26 years, height of 5 feet 1 inch, fat face, stocky and hunched, great player of the bansa, singer, and coaxer of the blacks, always at each of the dances on the plantations belonging to M. Roquefort. Those who have knowledge give notice to M. Linas of Le Cap, to whom [the runaway] belongs, or to M. Phillippe. There is one portugaise for compensation.80

Like the unnamed commandeur who held night-time gatherings in 1782, Cahouet used his relative privilege within the slave community, and his role as a coachman, to contact people on several plantations and disseminate the word about the calendas. Cahouet’s rank in the labor hierarchy may not have protected him from the typical ravages of slavery, meaning he may have sought freedom for the same reasons as other absconders. Alternatively, perhaps he felt he could be a more effective organizer if he were “underground” or off the plantation. Being of the Mesurade nation did not preclude Cahouet from taking part and having a leadership role in calendas. The evidence of ritual calenda gatherings persisted despite the May 1772 judgment banning free people of color from holding calendas, and the reiteration of this ordinance in March 1785.81 A Kongolese cook named Zamore, who escaped in July 1789, was described as a full-time drummer for the dances since he was last seen in Port-de-Paix.82 Jean-Pierre, a mulâtre drummer, was also a shoemaker in Le Cap used his French skills to pass as a free person of color in May 1790.83

These examples demonstrate that African descendants of varying statuses (free or enslaved), race (mulâtre or black creole), occupations within the slave hierarchy (merchants, commandeurs, cooks, and coachmen), and African ethnicities (Nagô/Yoruba, Mesurade, Kongo, Mondongue) participated in what were labeled as calendas. Calenda participants, and often the leaders of those gatherings, embodied a liberation ethos by liberating themselves from enslavement. Ritual work within spaces like calenda dance gatherings built racial solidarity through identification with several African symbols that were expressions of several cultural identities. Combined with the racial boundaries of colonial structures, Africa-inspired ritual participation, and other forms of collective action like marronnage, a collective racial identity began to emerge. Runaway advertisements indicate that calendas and other Africa-inspired ritual gatherings were a constant presence in the colony and provide piecemeal data that demonstrate ritualists were among the many who escaped enslavement and acted as micromobilizers, linking enslaved people from various plantations to free space ritual gatherings. We do not have a fully accurate account of how many calendas took place in Saint-Domingue, their exact locations, exactly how many people participated, or their identities. However, accounts of calendas in the few years leading to the Haitian Revolution might be a window through which we can understand ritual gatherings as politicized free spaces.

Ritual Rebels

Maroon-organized calenda ritual gatherings spread oppositional consciousness, through the invocation of orishas, saints, and the ancestral dead; the propagation of liberatory ideas; physical preparation for armed combat; and the inclusion of various enslaved people of varying ethnic groups and rank within the plantation regime. Colonists’ fears that antagonistic sentiments among blacks would spread from cities like Le Cap into the rural areas came to fruition in 1786. On June 3, the Superior Council of Cap Français banned blacks and free people of color from participating in “mesmerism,” a pseudo-scientific trend that had taken hold in Saint-Domingue. This ban was in response to several reports of calendas occurring in banana groves at the Tremais plantation in Marmelade, a northern district dominated by enslaved Kongolese Africans on newly formed coffee plantations. Four men: Jérôme dit, or “the so-called,” Pôteau and Télémaque from M. Bellier’s plantation at l’Ilet-à-Corne near Marmelade; Jean Lodot of Sieur Mollié’s Souffriere plantation in Marmelade; and Julien, a Kongolese of the Lalanne plantation also in Marmelade, were charged with orchestrating secret assemblies that frequently drew as many as 200 participants. In addition to facing charges for organizing the outlawed gatherings, several witness testimonies asserted that the men were known for selling nkisis and performing other sacred rituals at meetings insiders called mayombo or bila.84

Jean Lodot was known as a runaway who frequented the Souffriere plantation work gangs in Marmelade, carrying a small sack containing a crucifix, pepper, garlic, gunpowder, and pebbles. Witnesses saw him leading at least two ceremonies, including one when an overseer saw him in his hut among a small gathering kneeling in front of a table covered with a cloth and holding two candles. Jean held up “fetishes,” or unspecified ritual objects, in front of the table, which was an altar. Two machetes, crossed over each other, were laid on the ground in front of Jean. In a second meeting, participants drank a rum concoction containing pepper and garlic, which induced a sedative state from which Jean would raise them with the flat end of a machete, symbolizing participants’ death and rebirth, and connecting machetes to Africans and African descendants’ sacred world. Finally, a third witness, an enslaved man named Scipion, stated that Jean and his followers covered themselves with cane liquor, put gunpowder in their hands and lit themselves aflame.85