“Our border problem,” a recent policy report quotes an Algerian border official, “can be summarized quite simply as a problem of tomatoes and terrorists. Terrorists groups can use the same techniques and routes as smugglers of tomatoes do” (Hanlon and Herbert Reference Hanlon and Herbert2015). The quote reflects a common narrative in contemporary writing on smuggling: the invocation of a general, unregulated porosity of “ungoverned spaces” (Miles Reference Miles, Walther and Miles2018, 201) in global borderlands through which small-scale informal traders of food or textiles move alongside drug smugglers, terrorists, and other “global outlaws” (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom2007). “A culture of low-level corruption engendered by generations of smugglers makes it easy for terrorist groups to move people and supplies throughout the region,” the same report concludes (Hanlon and Herbert Reference Hanlon and Herbert2015, 6). As a result, policy documents commonly call for either an improvement in the state’s radar, through added surveillance infrastructure, a crackdown on corrupt bureaucrats, or a stringent limitation of the border’s porosity in general, through the construction of border fortifications (World Bank 2017; Timmis Reference Timmis2017).

This conception of smuggling rests on the assumption that illegal cross-border trade exists due to low state capacity, and directly subverts state regulatory efforts. More recently, however, an expanding literature in political science has argued that low state capacity does not necessarily follow from non-enforcement, as states often choose to practice “forbearance,” intentionally tolerating illegal activities for their distributional consequences (Tendler Reference Tendler2002; Holland Reference Holland2015, Reference Holland2016). It also rests on the assumption that illegal economies, even if they are tolerated, are not themselves actively regulated by states. In mainstream political science, the regulation of informal and illicit economies, if at all existent, is the domain of informal institutions, which are characterised as personalistic, and lacking third-party enforcement.

I argue that this conceptualisation of informal institutions is not only empirically inaccurate, but also limits any analysis of the real politics of informal institutions. I show that informal institutions, even in the context of illegal economies, can provide impersonal regulatory structures, and are not necessarily “stateless,” but can contain third-party enforcement by state agencies. I argue that the features of informal institutions should not be assumed a priori, but analysed as conditional on their political environment. From this, I lay out key questions for the analysis of the politics of informal institutions: who benefits from regulatory informality, what political relationships emerge from it, and how they change.

In order to demonstrate my arguments, I provide a detailed analysis of informal institutions that regulate smuggling in North Africa, based on fourteen months of in-depth fieldwork in the region. I argue that contrary to its common conception as operating in an ungoverned space under the radar of the state, the majority of the region’s smuggling activities take place through nodes of informal regulation that are capable of determining the quantity and price of goods that cross the border illegally. I find that these institutions are capable of distinguishing between different forms of illegal trade, particularly between the smuggling of licit and illicit goods—they recognise the difference between tomatoes and terrorists. I also demonstrate that these informal institutions are in fact capable of establishing impersonal regulatory structures as well as third-party enforcement.

Consequently, I suggest that the role of “lawless spaces” and individualised corruption have been overstated as explanations for the high levels of illegal trade in North Africa, and do not provide a constructive starting point for an analysis of the politics of smuggling. While states tolerate certain smuggling activities in order to maintain social peace in their borderlands, they do not do so by mere forbearance or turning a blind eye, but by carefully regulating different smuggling activities. This requires a new analysis of the politics of informal regulation.

The rest of this paper is made up of five sections. The first briefly reviews some of the current political economy literature on the regulation of illegal economies and informal institutions. The second provides information on the methodology and data collection for this study. The third maps institutions that regulate the smuggling of different goods in three different, and diverse, borderlands across north Africa. The fourth draws on these observations to challenge common conceptions of informal institutions and makes a case for “bringing the state back” into their analysis. The final section concludes and highlights avenues for future research.

Informal Institutions and the Regulation of Illegal Economies

In the words of the people interviewed for this study, its main subject has many names. Some call it tijāra muāziyya, “parallel trade,” or tijāra bainiyya, “intra-border trade,” while others use the Spanish trabando, or the Arabic tahrīb, meaning “smuggling.” It is a sensitive subject, and people pick their words carefully—a trend mirrored in academic writing on the subject. I use “smuggling” interchangeably with “illegal trade” to describe all forms of cross-border trade that violate the law applicable at the respective border. I differentiate between the trade of licit and illicit goods,Footnote 1 where licit goods refer to the goods for which a legal trade corridor exists that is not subject to additional security clearance. Prominent examples of illicit goods are narcotics, expired medicine, firearms, endangered animals, or historical artefacts.

For much of the literature on illegal economies, a project that is interested in their regulation, especially with state involvement, must appear to be a contradiction in terms. This part of the economy is commonly conceived as ungoverned, as “underground” (Witte, Eakin, and Simon Reference Witte, Eakin and Simon1982), “shadow” (Schneider and Enste Reference Schneider and Enste2000), “hidden” and “under the radar of the state” (Oviedo, Thomas, and Karakurum-Özdemir Reference Oviedo, Roland Thomas and Karakurum-Özdemir2009). Both mainstream institutional economics and critical institutionalists argue that illegal economies are, if at all, regulated by informal institutions. There are, however, crucial differences in how these two streams of literature characterize informal institutions.

New Institutional Economics (NIE), representative of mainstream institutional scholarship, defines institutions as “humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (North Reference North1990), and draws a clear boundary between two types of institutions. Formal institutions are mainly encapsulated in state structures (constitutions, laws) and enforced by state entities, such as courts and policemen. In contrast, informal institutions are considered to be lacking third-party enforcement; they are self-enforcing (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2005, North Reference North1990, 67), “through mechanisms of obligation, such as in patron-client relationships or clan networks, or simply because following the rules is in the best interests of individuals who may find themselves in a situation in which everyone is better off through co-operation” (Jütting et al. Reference Jütting, Drechsler, Bartsch and de Soysa2007, 31). Their conception as self-enforcing is logically connected to their characterisation in this literature as unwritten, small-scale, and personalised, as self-enforcing institutions are difficult to maintain at large scale or high levels of complexity (La Porta and Shleifer Reference La Porta and Shleifer2014; Soto Reference Soto1989, 180). For mainstream political economy perspectives,Footnote 2 illegal economies are exclusively regulated through informal institutions, and for this reason are assumed to take on the features of the institutions themselves: small-scale organisational units,Footnote 3 little third-party enforcement, and personalised relationships of exchange (La Porta and Shleifer Reference La Porta and Shleifer2014). As illegal economies are assumed to fall outside of the protection of property rights provided by the state, they are assumed to be characterized by insecurity, creating a market for clientelistic relationships with security forces (Varese Reference Varese2001; Gambetta Reference Gambetta1996). In a 2007 article, Bratton (2007, 97) explicitly defines informal institutions as “patterns of patron-client relations.”

While mainstream institutionalism draws a clear line between different spheres of institutional regulation, this divide does not hold up empirically. Numerous studies of illegal economies show that most economic activities straddle multiple levels of regulation.Footnote 4 Scholars of Hybrid Governance have challenged both the separation and the functional differentiation between formal and informal institutions that characterizes the NIE approach. Exploring the variety of informal institutional structures and experiences, critical institutionalist scholars have highlighted that the inferiority of informal institutions with respect to their efficiency (Assaad Reference Assaad1993; Meagher Reference Meagher2008; Roitman Reference Roitman1990), scope (Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980; Ledeneva Reference Ledeneva2008), and complexity (Meagher Reference Meagher2018), should be taken as an empirical question.

In their seminal paper, Helmke and Levitsky (Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004) call for a re-examination of the interaction between formal and informal institutions. Tendler (Reference Tendler2002) and Holland (Reference Holland2015, Reference Holland2016) have provided practical examples of these relationships, analysing how politicians purposefully tolerate illegal economies as a result of distributive and electoral considerations. These studies highlight that informal institutional regulation in illegal economies does not necessarily have to occur in competition with states, or under their radar. This paper follows Helmke and Levitsky in defining formal institutions as “rules that are openly codified, in the sense that they are established and communicated through channels that are widely accepted as official,” contrasted with informal institutions as “socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels” (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004, 37).

I aim to extend their research agenda on the relationship between formal and informal institutions by engaging more directly with the question of what substantive features should feature in our characterisation of informal institutions, and the consequences that this will have for our understanding of the politics of informal institutions and the regulation of illegal economies. In addition, I aim to contribute to the study of illicit trade within political science. Despite some notable interest from within the discipline (Andreas Reference Andreas2009; Ahmad Reference Ahmad2017; Goodhand Reference Goodhand2009; Scott Reference Scott2009), given its relevance not only for the study of institutions, but also state capacity, political settlements, and business-state relationships, there is a surprising scarcity of political science research into this domain. This is closely related to difficulties in generating empirical data on smuggling.

Methodology and Data

Researching smuggling comes with unique methodological challenges. While scholars of illegal trade have employed a variety of methodologies, I have found that for the study of its regulation, ethnographic methods are particularly well suited. Deep contextual knowledge is imperative to trace and understand informal institutions that are commonly unwritten and embedded in everyday social practices. Understanding how local participants contextualise these practices is crucial to building relationships that allow the conducting of interviews on such sensitive topics, and to contextualise their content. Through prolonged engagement and combining different forms of data, ethnographic methods are also well suited to addressing the challenges of triangulation that are common in the study of illegal economies.

I follow a number of scholars that have advocated for the use of ethnographic methods in political science (Wedeen Reference Wedeen2010; Schatz Reference Schatz2009; Simmons and Smith Reference Simmons and Smith2017). Wedeen (Reference Wedeen1999) argues that ethnography can be particularly useful to fill in the gaps between official demonstrations of obedience and ordinary experiences of unbelief and resistance—in a sense, this study attempts the reverse, tracing structures of regulation in the seemingly disobedient. Recent work on process tracing has informed the way this study has combined data to triangulate information (Bennett Reference Bennett, Box-Steffensmeier, Brady and Collier2008; Fairfield and Charman Reference Fairfield and Charman2017).

Because of the time needed to generate credible data on informal institutions, the study of smuggling has been dominated by single case studies. Analyzing the regulation of smuggling across multiple cases in North Africa, I contribute to the comparative analysis of smuggling. It is situated in two regions of North Africa— Northern Morocco and Southern Tunisia—with large volumes of smuggling in the same types of licit and illicit goods, which have in recent years seen changes in their border security infrastructure. They contain three different borderlands, their diversity ensuring that the patterns discussed here are not particular to one type of border within the region. While most of the paper describes institutions that regulate licit goods, this is not due to a disinterest in illicit goods, but due to their absence in these nodes of institutional regulation, which will be discussed further in the final sections.

The data for this paper were collected through fourteen months of fieldwork between 2014 and 2017. It consists of over 200 in-depth interviews with smugglers from a variety of networks including gasoline, textiles, foodstuffs, as well as illicit commodities; bureaucrats and politicians, civil society activists and researchers. It builds on extensive ethnographic research in both countries, focussing on the cities of Medenine and Ben Guerdane in Tunisia, and Oujda and Nador in Morocco, observing local markets and border crossings.

In order to protect informants, many interviews cited below are anonymized. The use of anonymous sources, while obligatory in the study of illegal economies, presents unique challenges in the presentation and use of data (Saunders, Kitzinger, and Kitzinger Reference Saunders, Kitzinger and Kitzinger2015). While I cite anonymized interviews in order to illustrate my argument, none of the details of the institutions described in this paper are reliant on single anonymized interviews, but have instead been triangulated through multiple interviews as well as participant observation. Extensive information on triangulation, anonymization, the process of data collection and its wider ethical and methodological implications are presented in online appendix 1.

Regulating Smuggling in North Africa

There are good reasons to situate this analysis in North Africa. The region contains a wealth of smuggling networks, variation in its borderlands, and relative poverty of academic research on them.Footnote 5 Due to the global occupation with terrorism, migration, and the conflict in Libya, North Africa has been the focus of increasing concern around border porosity. Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria all have increased border fortifications, commonly financed by the international community. And yet smuggling remains widespread.

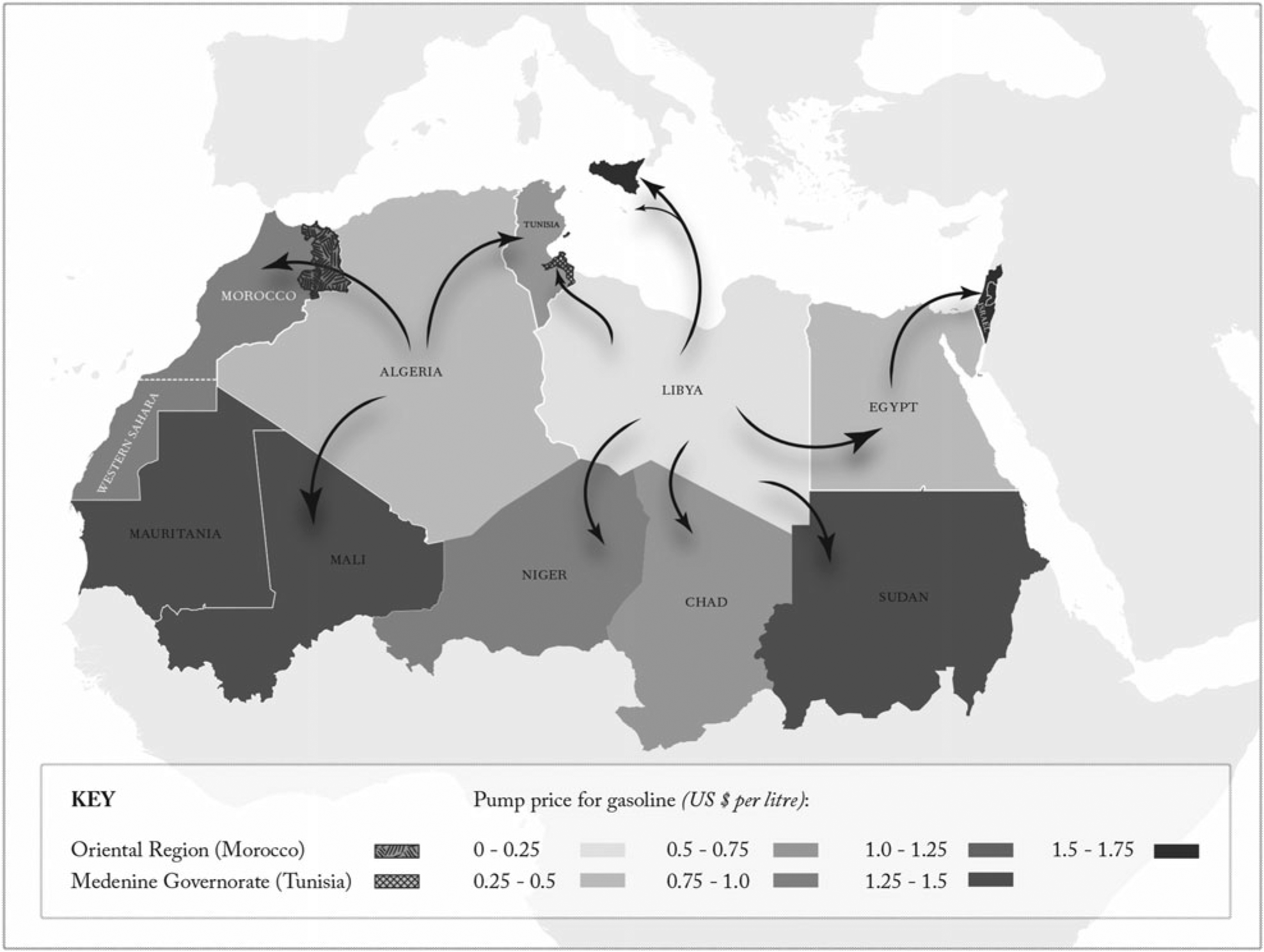

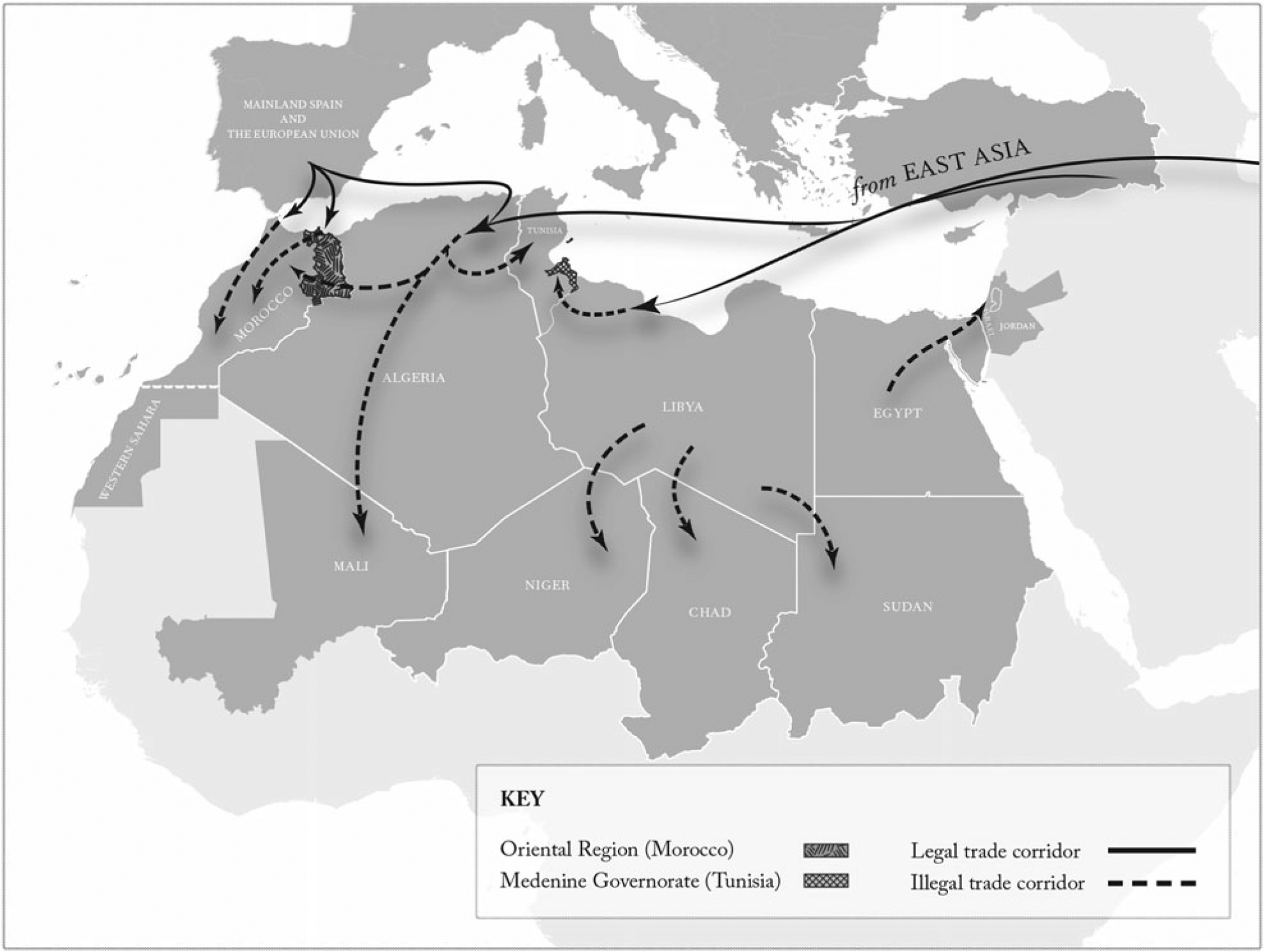

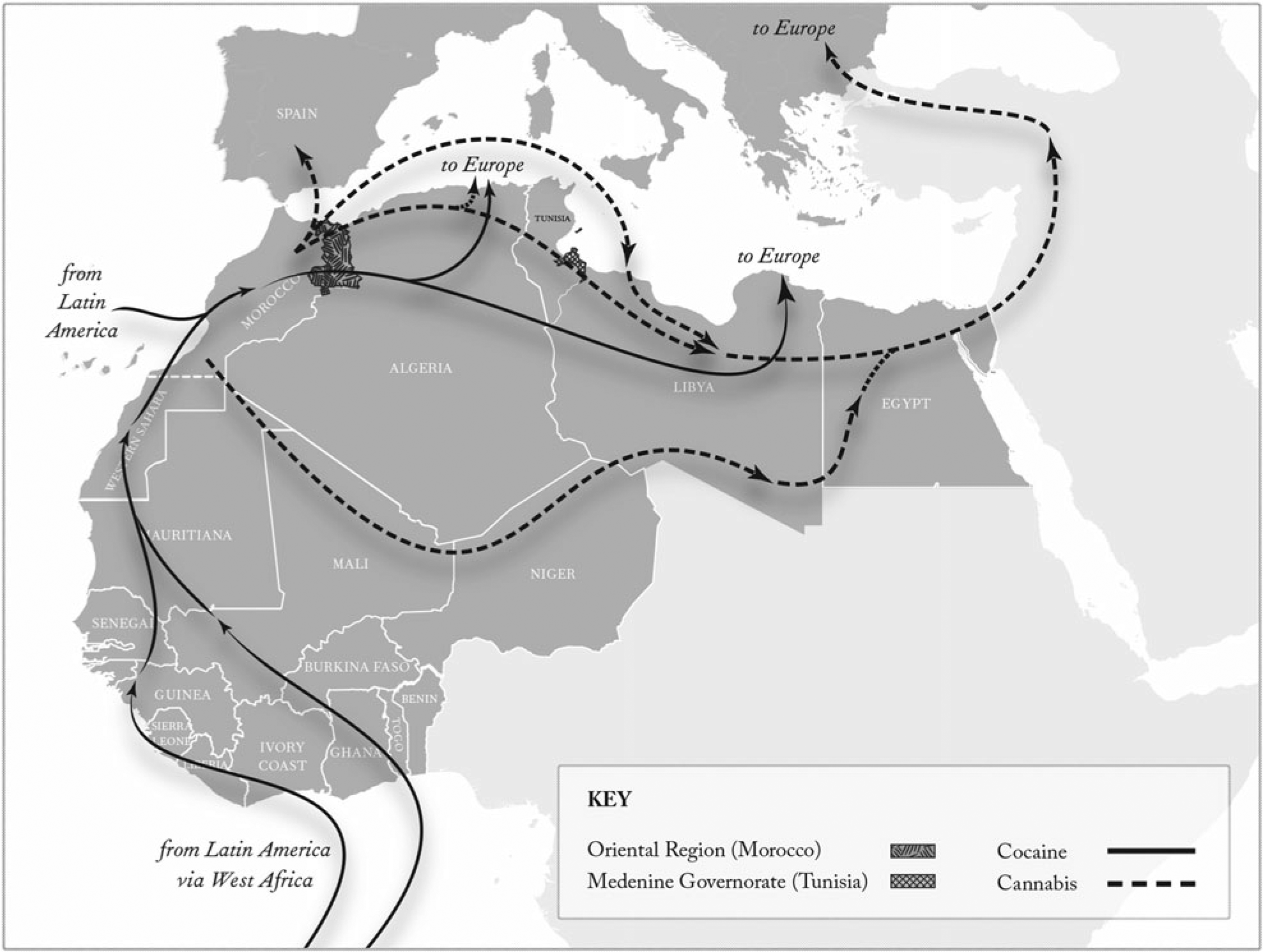

Figures 1, 2, and 3 outline some of the main smuggling corridors in North Africa. They highlight two crucial features about smuggling networks in the region: their embeddedness in global commodity chains stretching beyond North Africa, and the heterogeneous patterns that emerge when examining the smuggling corridors for different goods. As the maps demonstrate, all key smuggling corridors intersect the two regions studied here. Both have developed large networks for the import of contraband gasoline, driven by price differences due to subsidy regimes in the neighbouring oil-rich Algeria and Libya (figure 1). Both regions have also developed large networks for the import of foreign-produced non-gasoline consumer goods including foodstuffs and textiles, driven by tariff-related price differences in the neighbouring Libya, Algeria, and Melilla, a Spanish enclave in Northern Morocco. Both regions have been in the focus of networks trading in illicit goods. Moroccan smugglers exports cannabis, while importing amphetamines and other prescription narcotics, and functioning as a transit route for the cocaine trade. Tunisian smugglers have functioned as facilitators for the cocaine and cannabis trade.

Figure 1 Main corridors for the smuggling of gasoline in North Africa

Figure 2 Main corridors for the smuggling of non-gasoline consumer goods in North Africa

Figure 3 Main corridors for the smuggling of narcotics in North Africa

Smuggling in the region has existed for centuries, pre-dating the borders that now make it cross-border trade, and the laws that now make it illegal cross-border trade (Scheele Reference Scheele2012). However, it has not remained constant, adapting to changing economic and political structures. The region’s current macro-structure of illegal trade has its origins in the 1980s and 2010s. Many of the smuggling networks built on price differences and arbitrage have established their current direction of trade in the 1980s, following expansive subsidy provisions, soaring oil prices, and diverging tariff regimes, and have expanded into the early 2000s (Ayadi et al. 2013). Many of the illicit trades have operated for decades, but changed their direction of trade more recently. While cannabis grown in Morocco, alongside cocaine imported via West Africa has traditionally been smuggled directly north to Europe, changes in the enforcement environment in recent years have increasingly created a west/east route through Algeria (Hanlon and Herbert Reference Hanlon and Herbert2015, 25). At the same time, the conflict in Libya has restructured the regional trade in arms towards the North African country (Kartas Reference Kartas2013). For the most part, what is presented here is the most recent and the detailed account of these networks and the institutions that regulate them that I am able to provide. However, with the gasoline trade having largely collapsed, I present the institutions that govern it as they have existed in 2014 (Morocco) and early 2017 (Tunisia) respectively.Footnote 6

The remainder of this section presents a detailed mapping of the institutions that regulate smuggling across three borders in North Africa. Their description here seeks to highlight that the features of these institutions clash with common assumptions in mainstream institutional scholarship, as

• they are largely impersonal,

• they contain third-party enforcement, and

• they are capable of regulating the quantity and type of goods that crosses illegally, segmenting between licit and illicit goods.

The three different cases serve to demonstrate that this holds in different borderlands irrespective of their legal status or geographic context, as it includes two open and one closed border, two rural and one urban border, two east-west and one north-south border.

Tunisia-Libya: Regulating an Open, Rural Border

The Ras Jedir border crossing lies at the northern tip of the border between Tunisia and Libya. The vast majority of the smuggling trade between Tunisia and Libya operates through this border crossing, and has done so for the last three decades. A variety of internationally produced consumer goods are shipped from Turkey or East Asia to the ports of Western Libya, packed on smaller cars, and brought into Tunisia through the crossing. Here, the goods are completely undeclared or mis-declared, with the avoidance of the full import tariff making up a significant section of the profit margins of local traders. The trade is routinized, and occurs in broad daylight. Hundreds of young men earn their livings as drivers between Western Libya and Southern Tunisia. As this usually occurs alongside a payment to the customs agents at the border, media reporting connects the procedure to corruption, painting the region as a “lawless, Wild-West-like town” (Prentis Reference Prentis2018).

Closer observation, however, reveals a fundamental regularity in the procedures at Ras Jedir. For decades, the trade at the border crossing, while officially illegal, has been regulated through an informal agreement between local traders, customs officers, and both the Tunisian and Libyan state apparatuses. This agreement regulates the types of goods that may pass informally through the crossing, their quantity, the means of transport, and the cost of this informal trade—meaning both the practice of under-reporting and the side payments made to border agents. This agreement has not stayed fixed—many of its terms have varied over recent years, based on shifting power balances between the respective actors. However, while the details of the agreement have fluctuated, its claim over the regulation of these features of the trade, has, with the exception of a few months after the 2011 revolution,Footnote 7 remained constant.

In order to illustrate, this is the agreement as it existed in April 2017:

• Traders who were transporting goods with a value of less than 2000 Libyan dinar (USD 1507)Footnote 8 plus 150 litres of Libyan gasoline were not required to pay anything at the border crossing, neither the official tariff nor any standardised bribe or other informal fee.Footnote 9

• Traders who were transporting goods with a value of over 2000 Libyan dinar (USD 1507) would pay 1500 Libyan dinar (USD 1130) to an intermediary on the Libyan side, while 300 Tunisian dinar (USD 125) would be paid to the Tunisian customs officials.Footnote 10 While the money on the Libyan side would be divided between multiple groups that exercised some control over the border crossing, including the municipality of Zuwara, the money on the Tunisian side would partly go towards the tariff income of the state, while some would go directly to the private income of the customs agents.

• Weapons and narcotics were excluded from the deal, and not allowed to be imported through the border crossing. Medicine is only allowed to be imported informally if paperwork by a doctor can be provided. All goods that were brought through had to pass through a scanner at the border crossing to ensure that they are in accordance with this rule.Footnote 11

It is worth noting that this agreement represented one of the more “deregulated” versions of this institution. Its immediate predecessor, in effect from January until April, had set an upper limit per car of goods with the total value of 4000 Libyan dinar (USD 3013) plus 150 litres of gasoline,Footnote 12 and a later iteration again introduced a maximum limit of 5000 Libyan dinar (USD 3767).Footnote 13 While this agreement only prohibited the informal import of illicit products alongside medicine, agreements that had been in place before had placed additional restrictions on the types of goods that could be brought through the crossing without paying the formal tariffs, mainly to protect goods that politically connected businessmen in Tunis had an interest in protecting from competition through informal trade. This included almonds, pistachios, high-value electronics, and bananas.Footnote 14 Earlier agreements had also included restrictions as to the type of cars that could be used for informal trade through the border crossing—this boiled down to a prohibition against the use of large transporters, as the use of smaller cars helped to employ young men from the region, and made the practice less accessible for traders based in Tunis.

The agreement described here is unwritten, but knowledge of its details is widespread—a wide variety of traders in different locations and networks were able to recite it to me. However, an earlier version of this agreement was even written down—between January and April 2017, a text existed that had been produced through negotiations including municipalities from Western Libya, local smugglers from Tunisia, militias, security forces, and one member of the Tunisian National Assembly. A translation of the agreement and list of its signatories can be found in online appendix 2.

Morocco–Melilla: Regulating an Open, Urban Border

Smuggling in North Africa is not limited to the rural periphery. The Spanish enclave of Melilla is highly urbanised, covering less than five square miles of territory, bordering the Mediterranean in the North, and Morocco in the South. Due to concerns about migration, its 6.8-mile border has been heavily securitised in recent years. And yet it is estimated that at least half of the goods that arrive in the port of Melilla, virtually tax-free, are brought into Morocco informally, bypassing any official trade or tariff regulations (Castro and Alonso 2014). The most common goods traded this way are textiles and foodstuffs, as well as a variety of European consumer goods. While some scholars have described the procedures around Melilla as “a space of lawlessness” (McMurray Reference McMurray2001, 123), the situation is in fact similar to that in Ben Guerdane—upon closer observations, clear rules and regulations emerge.

The Beni Ensar crossing is named after the Moroccan suburb that borders it. It contains three lanes going into Morocco: one for cars, one for normal walking traffic, and one for smugglers on foot. Late at night, Moroccan drivers start lining up in a long queue of cars in the Moroccan town of Beni Ensar, to be let into Melilla early in the morning, and drive to one of the countless warehouses just on the other side of the border crossing. They fill their cars with clothes, tires, foodstuffs, or other imported products, and return to Morocco, where the goods are being sold on markets across the country. As the cars pass back into Morocco, their imports are let through unregistered and untaxed in exchange for a bribe to the Moroccan customs officers. Here, too, bribes are relatively standardised—they are dependent on the value of the goods, and typically range between 50 and 200 Moroccan dirham (USD 5 –20). The cars are inspected by Moroccan customs officers, allowing some estimation of the goods value (and hence the level of the bribe), but also the enforcement of some restrictions on goods that are not allowed to be traded this way—alcohol, for example, or medicine cannot be traded in this fashion. While there is no official restriction on how many cars can engage in this trade, they are limited through standardised times during which the trade may occur—usually between 6:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m., after which the trade shuts down and the traders load off their goods and get in line for the next day.

Trading on foot is even more common. Two lanes are open for foot traffic. One is for tourists and visitors, and can also be used by small-time traders carrying one bag—their crossing with a small number of goods is legal. For all other traders, there is a special lane. A member of the Spanish guarda civil directs people into the correct lane. The specialised lane for traders is significantly busier, and around half a dozen members of the Spanish police are typically involved in getting traders to line up, and walk through the narrow fenced-off path, through an iron turnstile, and then past the Moroccan customs officers and into Morocco. The payments to Moroccan customs officers, in exchange for not applying the law with respect to the goods being imported, can be differentiated into three categories.

The first group are independent smugglers with very small amounts of goods, often elderly women from the Oriental region who are selling their products to local stores. While they used to pay small bribes to Moroccan customs officials in order to pass, custom officials stopped systematically demanding bribes from them in 2010 and 2011, and have not done so ever since. There are still occasions in which bribes are demanded or goods are confiscated, especially when they are carrying enough to fall into the second category, but the systematic taking of bribes from very small-scale traders seems to have stopped—I will return to this point shortly.

The second group are smugglers who also work independently but are carrying larger amounts of goods. They typically pay a bribe to the Moroccan customs officers, which, similar to trade in cars, is very roughly proportional to the quantity and value of their goods, and usually ranges between 50 and 100 Moroccan dirham (USD 5–10).

The third group are smugglers who work for a wholesaler, a “boss,” and are usually supplied with a “ticket,” which carries their name, the name of their boss, and the goods that they are transporting. As they pass the Moroccan customs officers, they use the ticket to identify themselves as employees of a particular wholesaler. They would hence not have to pay a bribe, as the bribe to the customs officers would be part of a larger, regular arrangement between the wholesaler and the customs officials. The traders would then deliver their goods to a transporter working for the same boss on the other side of the border, with their ticket again identifying them as employees of a certain wholesaler, and specifying the goods that they have to deliver, as well as the payment that they are entitled to receive. For the goods carried by hand, similar restrictions apply as to the ones transported by cars—medicine and alcohol, even sanitary wipes that contain alcohol, are not let through. After Morocco imposed restrictions on the use of plastic bags in convenience stores for environmental reasons, traders reported that these bags also became prohibited.Footnote 15 Similar to the trade via cars, trade on foot is typically restricted to the time between 6:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m. Although they receive no payments from the traders, much of the organisation of the trade is done by the Spanish police at the border, which is primarily made up of riot police from mainland Spain, which are brought into Melilla in two-week rotations. If conflicts break out at the Beni Ensar crossing, policemen draw on the mediation of an informal cross-border trader, whom they have given a police pin to mark her status, and preferential treatment at the border crossing as payment.

The routinisation of this process is even more striking at the Barrio Chino crossing in the southwest of the city, used almost exclusively by large-scale networks traders and their transporters. Barrio Chino has three lanes that lead into Morocco, all of them for foot traffic. Nothing signifies their purpose for illegal trade more clearly than the signs over the entrances to the border crossing: on top of the entrance there are two silhouettes depicting ‘portadores’: one man, and one woman, carrying a large bundle of goods.

Here, too, there are time restrictions for informal trade, typically between 7:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m.Footnote 16 Transporters, so-called “portadores” or “hamala,” wait in lines, under sheet-metal shelters on a large space near the crossing. Trucks then bring goods from the nearby warehouses, pre-packed in bundles wrapped in plastic sheets, and painted with numbers marking them as the property of a particular owner. Organised by the Spanish police, transporters pick up the bundles and carry, push, and roll them up the small passageway to the border crossing. Three metal turnstiles present the key bottleneck of the border—the police let traders approach them in small groups, and local intermediaries, employed by the larger traders,Footnote 17 stand at the turnstiles to facilitate a smooth flow of carriers through them. Similar to the Beni Ensar crossing, there are payments to the Moroccan customs officials, although traders who work for one of the bigger wholesalers do not pay bribes, which are organised centrally by the wholesaler.

On the Moroccan side, transporters are ushered to larger vans, in which the bundles are stacked and transported across Morocco. Contrary to Beni Ensar, there seems to be less scrutiny of the content of the bundles at the moment they cross the border. This likely relates to the absence of small independent traders—the traders operating here, as well as their goods, are well known to Moroccan customs and security services. Still, it appears that some goods that cannot be brought through Beni Ensar, such as alcohol, are being traded in Barrio Chino. As in Tunisia, large elements of the regulation observed here are impersonal: anyone with a Nador residency card (that allows the free movement to Melilla without a passport) can work as a transporter, and no particular connections to customs officers are required. Even for people outside Nador, a residency card is easily acquired—transporters from outside the area told me they were able to purchase them for around 2500Dh (USD 250)—many of the “hamala” are not originally from Morocco’s northeast.

Morocco—Algeria: Regulating a Closed Border

The land border between Morocco and Algeria has been closed since 1994, leading to the absence of border crossings as natural points of regulated smuggling as in the two cases described earlier. And yet in the decades following the closure, a variety of points were established along the border that fulfilled the same function. The trade in gasoline, which for many years dominated the informal cross-border trade, is instructive. Gasoline would be collected at Algerian gas stations and then re-filled into jerry-cans in rural farms near the border. They would then be brought by Algerian traders to pre-agreed meeting points along the border. There would usually be a set of about ten potential locations, the one that would be used would be pre-arranged on a day-to-day basis. At these points, the gasoline would be sold wholesale to Moroccan “first buyers” who would transfer it to depots in rural Morocco where it would typically be re-sold to “second buyers” who would transport the gasoline across the country. Both Moroccan and Algerian soldiers were involved in the organisation of these exchanges, with the Algerian soldiers usually playing the dominant role. The soldiers would not only observe the procedure, but also act as mediators in the case of conflict between the traders, and as enforcers of a quiet and orderly exchange. Both Moroccan and Algerian soldiers would receive a payment from the traders. The level of these payments would typically be fixed; for example, Moroccan soldiers would receive 5 dirham for every 30-litre canister that a trader was buying that night.

Another crucial fixed-point within the trade were gates in the border fence on the Moroccan side that the Moroccan military operated in order to organise and regulate cross-border informal trade. A variety of these points existed around the border near Oujda, along with specific times during which they were opened. One gate was opened every night between 7:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., another one between 8:00 p.m. and midnight. During this time, Moroccan soldiers would let traders pass across the border and back into Morocco. These crossings did not appear to be operated in coordination with the Algerian soldiers, and continued to operate even when Algeria started to crack down on the trade and increase its own border security. Moroccan soldiers would screen and inspect traded goods as they entered back into the country—at least in the case of new traders. It appears that illicit goods were not traded through these gates; dominant goods here were gasoline, cigarettes, fabrics, and household items. Prior to 2010-2011, soldiers would collect bribes from traders of all goods. In 2010-2011, in parallel to similar changes at the Melilla border crossings, this procedure appears to have changed: small scale-traders, especially small-scale traders of gasoline, were not asked to pay bribes anymore by the Moroccan soldiers, and could pass through the gates for free. Bribes for larger quantities and higher profit margins remained.

Regulation Outside the Nodes

The previous sections have outlined crucial nodes along the borders of North Africa that regulate their porosity, even for illegal trade. However, while the majority of illegally traded goods in the region pass through these nodes, smuggling also exists outside of them. Opting out of trading through the channels mentioned here usually involves less predictability, and requires larger capital, usually in the form of more powerful off-road vehicles or the ability to bribe higher officers in the military. Operating outside of the institutional structures I have described above hence is primarily attractive to those trading in illicit goods that are excluded from the institutionalised smuggling through the nodes discussed earlier, and those trading in large quantities of goods with a high profit margin, who can either negotiate a better deal outside of these nodes, or who are operating profitably enough to be able to finance the risks involved. Between Tunisia and Libya, traders move goods—high-value licit goods, as well as cigarettes, arms, alcohol, and narcotics across the difficult territory along the border, in what locals call the “contra route.” Similarly, on the border between Algeria and Morocco, smugglers try their luck outside the “doors”—many of them moving cannabis-based products grown in Morocco. Regulation along these routes, clearly, is much less visible than along the nodes discussed earlier. Still, there are strong indications that even here, regulation is not entirely absent.

First, the existence of nodes that provide more attractive regulatory conditions for the illegal trade of certain goods influences the type of goods that are traded on the contra route. Microwaves, carpets, or children’s clothes would not be traded illegally outside of the more normalised nodes, which would offer a vastly superior cost-risk trade-off, especially for small-scale smugglers.

Second, in some regions outside of these nodes, relations between smugglers and security forces approximate a cat-and-mouse game, which still contains rules that structure, control, and regulate interactions. Traders, security forces and politicians across these case studies report the existence of “security arrangements” in which smugglers, even as they are trying to evade security forces as they are crossing the border, will still report suspicious activities along the border and the presence of unknown individuals back to the security forces. While some of these agreements seem to have developed out of clientalist relationships with security forces, others seem to have grown historically out of similar agreements with pastoral communities in the borderlands. There is an incentive for smugglers to engage in these activities: increased perception by security forces that the part of the border that they operate in is unmonitored might lead to higher security-force presence there, increasing the cost of smuggling. Even beyond these arrangements, there appears to be a routinisation to these “border games” (Andreas Reference Andreas2009) that defies common characterisations of their interaction as unstructured or “under the radar of the state.” An anecdote serves to illustrate this.

In March of 2017 I was sitting in a roadside café in a small village near the border in Southern Tunisia. I was talking to the only two other customers: a friend who was working nearby, and a local smuggling boss, who has around ten young men working for him. On most nights, they drive across the desert to Libya, and return with a variety of goods, some licit, and some illicit. Most of the traders do not own their own cars, they lease expensive SUVs for one principal purpose: to outrun the local customs agents. “Our cars are much faster than theirs,” the man brags. It is easy for us to verify this from the little café: while many of the smugglers cars are parked next to the café, the customs agents’ cars are parked next to their small headquarter on the other side of the street. While smugglers and customs agents play cat-and-mouse at night, they are sitting right across the street from each other during the day. They know each other. “It’s like a game.”Footnote 18 If they get caught, they negotiate a bribe. If they make it through uncaught, they are home free. Once they are home, as the sun rises, their goods are no longer up for scrutiny. The likelihood and price of getting caught is a part of the calculations of the smugglers. Their expected income is subject to a repeatedly played game that every player understands. When one of the customs agents refuses to take bribes, the smuggler recounts, they know his superior and can arrange for him to be transferred elsewhere. And the game continues.

Analysis: Segmented Porosity and Informal Institutions in Political Science

The previous sections have provided a mapping of the procedures of illegal cross-border trade in North Africa, highlighting the nodes of informal institutional regulation through which much of this trade passes. The remainder of the paper discusses conclusions that emerge from these observations, regarding: 1) border porosity in North Africa, 2) the characterisation of informal institutions in political science, and 3) the politics of informal institutions.

Segmented Porosity

What has emerged from this mapping is that smuggling in North Africa is a densely regulated activity. Informal institutions at border crossings, meeting points along the border, police checkpoints, and markets serve to structure, normalize, and control the trade. They are able to affect the number of goods that come into the country illegally through physical bottlenecks like turn-styles, through regulations on the size of the vessels in which goods may be transported, and time limits on when goods can be traded. Most smugglers trading through Ras Jedir and Melilla are not spending their days evading their police—they are spending their days standing in line. These institutions are able to affect the cost of the illegal import of these goods, through institutionalised bribery arrangements. Crucially, they can differentiate between different types of goods. As the earlier sections have demonstrated, across all cases studied here, different regulatory nodes exist for different goods. A pattern emerges that separates most licit goods from illicit goods: the path that contraband tomatoes—or textiles, or TV sets for that matter—would take across the region’s borders is not available to terrorists aiming to smuggle weapons, or to networks smuggling narcotics. Returning foreign fighters or those on travel blacklists would have serious difficulties passing through these nodes—and even face difficulties outside of them. This is not to say that the smuggling of illicit goods does not occur in the region—it does, and poses serious problems. But its origins do not lie in a general, unregulated porosity of the region’s borderlands, which can be used by smugglers of gasoline and guns alike. Instead, we must note that the porosity of North Africa’s borders, even where illegal trade occurs, is regulated and, in its regulation, segmented.

Observations in the global literature on smuggling suggest that in the prevalence of routinized informal regulatory structures, North Africa does not represent an unusual case. Scholars of smuggling in Sub-Saharan Africa have long conceptualised its interaction with state authority as a process of rule-making and re-making, describing complex arrangements of informal and hybrid regulations (Nugent Reference Nugent2003; Titeca and De Herdt 2010,; Raeymaekers Reference Raeymaekers2012,; Meagher Reference Meagher2014). In her study of the relationship between the Taliban and local business communities in Afghanistan, Ahmad (Reference Ahmad2017) notes how simple and predictable informal tax arrangements contributed to smuggling networks’ support for the movement. Herbert (Reference Herbert2018) highlights the crucial role that informal regulatory arrangements played in organising Mexico’s narcotics trade, and traces the eruption of violence as the power dynamics underlying these arrangements shifted. Tagliacozzo (Reference Tagliacozzo2009) in South East Asia, and Van Schendel (Reference Schendel1993) on the border between India and Pakistan, observe structured informal regulatory institutions with the participation of local state agents.

Characterising Informal Institutions

Despite their normalisation and visibility, these institutions regulating illegal cross-border trade must be classified as informal, as they remain in direct contradiction to the formal law—communicated through the “officially sanctioned channels.” While state actors play a crucial role in their maintenance, they do not do so in an official capacity. At the same time, their systematisation differentiates them from individualised instances of corruption, as the interaction is based upon commonly understood and coordinated rules of the game. This brief survey of informal institutions in the regulation of smuggling in North Africa highlights some contrasts between the informal institutions described here and common characterisations of informal institutions in modern mainstream institutional scholarship. Two points in particular stand out.

First, informal institutions can provide impersonal regulation. As discussed earlier, one of the traditional theoretical distinctions between formal and informal institutions in mainstream political economy rests on the assumption that informal institutions are inherently personalistic. The classic characterisations of informal institutions as small-scale, inefficient, and unwritten ultimately follow from this primary assumption. The analysis presented here does not support this assumption. The informal regulation of smuggling at the Ras Jedir border crossing, at the Melilla border crossings, and at the gates alongside the Algerian border with Morocco are all largely impersonal. They require certain characteristics of the people involved in them, such as Tunisian passports or a residency card for Nador, but this is typical for impersonal institutions. They are not tied to particular personal identities—surely, family connections help in the smuggling business, but they also do in the formal sector.

Second, informal institutions can provide regulation that contains third-party enforcement. Some of the logic behind the assumption that informal institutions are incapable of operating impersonally lies in the expectation that they lack third-party enforcement, that they are self-enforcing, and that those adhering to them are required to avoid persecution when they stand in opposition to the formal law, hence requiring them to operate on a basis of trust. It is worth noting that once more, in the context of the institutions observed here, these expectations do not hold: police, customs agents, and soldiers, albeit unofficially and illegally, systematically act as enforcement agents for these institutions and tolerate illegal activities within the realm of these institutions. While in some cases they appear as corrupt patrons of individual smugglers, in others we observe them enforcing informal rules, either collecting no bribe at all, or collecting a fixed bribe level that has been agreed as part of the institution itself. Crucially, they create interactions that are predictable, and necessitate neither trust nor evasion.

Given that they are impersonal and contain third- party enforcement, it is unsurprising that we also find some of these informal institutions are not necessarily always unwritten: both the institutions at the Ras Jedir crossing and those in Melilla at times included documents that were not only written, but also stamped and signed. It is hence also unsurprising that these institutions are able to operate on a large scale, regulating the activities of thousands of traders, involving values worth millions of dinars and dirham every day. They affect networks that operate not just across borders, but globally—it is common to find young traders in Southern Tunisia or Northern Morocco who have visited China, and remain in close contact with their suppliers there.

The set of informal institutions in political science is wide and diverse, and shifting an argument from one group of informal institutions to the whole set is not always appropriate. However, where personalisation and lack of third-party enforcement have been assumed as characterising features of all informal institutions, these empirical contradictions provide a serious challenge. The observations that informal institutions can operate impersonally and with third-party enforcement can be extended to noting that informal institutions do not necessarily need to be “stateless” in order to be informal. Even when they are in direct contradiction to the rules communicated through the “officially sanctioned channels,” they can still be supported and enforced, informally, by these same channels. While this will not surprise most observers of the politics of regulation, this has been under-appreciated as a systematic starting point in modern institutionalism. This extends the argument of the literature on forbearance on the purposeful non-enforcement of formal institutional regulation to the purposeful enforcement of informal institutional regulation.

None of this is to say that the two categories collapse into each other, even if distinctions such as personalisation and third-party enforcement are removed. The fact that they are created, communicated, and enforced outside the officially sanctioned channels still remains analytically meaningful, and should be retained as the primary substantive feature of informal institutions. All further features, however, cannot be deduced from the institutional type alone, or even the relationship between formal and informal institutions. This is because they are conditional upon the political environment: an analysis of the politics of informal institutions is needed.

The Politics of Informal Institutions

Understanding informal institutions necessarily requires an analysis of the power structures that produce and sustain informality. This includes the motivation, organisation, and power of those affected by the institutional environment as well as the relationship of the state to both levels of institutional regulation, and whether it is directly engaged in non-formal regulation, either through forbearance or through actively shaping informal regulation. Three central questions should be at the heart of a political analysis of informal institutions: How do regulatory actors benefit from the regulation’s informality? What political relationships emerge from this? And how do they remain in equilibrium? In the following, I will discuss these questions, drawing on the empirical context of this paper to demonstrate the insight they can generate into informal institutions and the regulation of illegal economies.

First, why do states participate in informal regulation instead of either repressing or formalising it? And why do members of the security forces participate in the maintenance of informal regulatory institutions rather than maximising bribe levels or crack down at will? Theoretically, a variety of mechanisms could be involved in keeping this power in check, including fear of retribution, capacity constraints, political settlements, or a shared moral economy of appropriateness. These cannot be assumed to have uniform effects on the politics of the institutional regulation, and should form the starting point of a political analysis of informal regulation.

According to interviews with politicians, bureaucrats, and enforcement agents in both countries, concerns about social unrest appear to be a crucial factor in the empirical context described here. “It absorbs the anger and the unemployment,” a high-level bureaucrat in Oujda summarises, “we are buying social peace.”Footnote 19 The toleration of some smuggling is framed as an informal subsidy to the borderlands, which have historically seen little formal state investment. This provides a good framework for thinking about the exclusion of illicit goods from these regulatory institutions, as well as the way in which many of these institutions impose maximum quantities that can be smuggled at any crossing at one time, thereby increasing its labour-intensity.

And yet it would be technically feasible for states to set up formal regulations that mimic the informal ones: free trade zones, or geographically limited special trade permits. While the literature on forbearance has highlighted the advantages for politicians in the non-enforcement of certain laws, thinking about the power relations and rents created through informal regulation is equally productive. Informal regulation of illegal activities typically shifts regulatory power towards states’ executive and security apparatuses, often mapping upon the relative power of the latter, especially under authoritarianism. In the cases studied here, security services are able to extract significant revenues from the trade, and bureaucrats interviewed for this project in both countries have identified security services as obstacles to formalisation.

State involvement in informal regulation also facilitates the practice of forbearance in a sector that is security sensitive, such as smuggling, allowing the toleration of certain illegal activities alongside their close monitoring. In other cases, it allows for the toleration and regulation of commercial activities that the state has an interest in maintaining, but would be seen as violating national, cultural, or international norms. It can create a merchant class that is excluded from formal markets that have been captured by politically connected business networks and create barriers to entry that restrict informal rent streams to local networks or survivalist activities. In the context presented here, the restriction against large trucks at the Ras Jedir crossing presents such a barrier. Equally, if rules are unwritten, their communication can restrict access to selected social networks, even if they are impersonal. While changes in the institutions discussed here are usually communicated quickly through word of mouth and social media, the speed of access to new information would still present a barrier to actors entirely unfamiliar with the local context. Finally, there is good reason to believe that informal regulation is also easier and quicker to reverse, thereby creating a relationship of dependency between the beneficiaries of this economy and its regulators.

This suggests a second question: what forms of political relationships emerge from this kind of regulation? As discussed earlier, the classical characterisation of informal institutions as personalistic suggests clientelism as the principal form of interaction with the state (Bratton Reference Bratton2007). While clientelistic relationships are widespread, this analysis suggests that it is neither the only nor the natural political relationship to emerge out of informal institutional regulation. While the literature on forbearance has already widened the space for different forms of political relationships, the empirical cases here support the argument that no forms of political relationships observed in the context of formal regulation should be ruled out in an informal context.

The institutions I describe contain instances of individual corruption, but also of systematic and coordinated strategies across different organs and agencies of the state. The agreement on the procedures at Ras Jedir provides an example: its negotiation included the regional leadership of the Tunisian customs service, a member of parliament, and a civil society organisation founded by local smugglers that has met and negotiated with a variety of government officials, including cabinet ministers and the country’s president.Footnote 20 Coordinated procedures for the regulation of small-scale illegal trade across the cases discussed here that do not necessitate the payment of bribes point to a similar dynamic.

The toleration and informal regulation of much of North Africa’s smuggling economies trading in licit goods are best conceptualised as a club goodFootnote 21 distributed among the population of the periphery in order to secure their acquiescence in the context of a development model that has concentrated formal rent streams in the political centre. For many smugglers interviewed in this project, the politics of their activity are not embedded in relationships of patronage with politicians or members of the security services, but wider agreements that have been negotiated with state representatives and interest groups, and through which smuggling is being framed as a local public good, if not a right. In Tunisia, Morocco, and Melilla, recent years have seen the emergence of formally recognised civil society organisations representing groups of smugglers in negotiations around informal regulatory institutions. In light of these considerations, it is unsurprising that the earlier sections have described cases where policemen and soldiers oversee the smuggling of some goods without collecting any bribes at all,Footnote 22 as their participation is not driven by corruption, but by their role in a larger strategy of informal regulation by the state.

At the same time, it is worth noting that the political relationships observed here are not normally distributed over different classes of goods. In parallel with the exclusion of illicit goods from impersonally regulated nodes, the club-good clientelism through impersonal informal regulation does not extend to illicit goods, which appear to be significantly more embedded in individual patron-client linkages. However, rather than assigning features to these goods, this pattern is best examined through the politics of this trade. Here, the networks trading in licit goods are more closely connected to labour-intensive survivalist activities and more palatable to local moral economies, making them more natural candidates for toleration and impersonal regulation by a state intending to utilise them as informal subsidies to borderland communities.

Instances when the informal regulation of smuggling activities in the region has broken down also highlight how deeply embedded it has become in the region’s wider distributional politics. In 2010, 2016, and 2018, disagreements over the procedure at Ras Jedir led to the crossing’s closure by Libyan authorities, crippling the local smuggling economy. In every case, large-scale protests, strikes, and riots broke out, as locals called upon the Tunisian state to either negotiate with the relevant actors to reach a new agreement over the regulation of smuggling, or provide alternative income streams to the region through development projects (Gallien Reference Gallien2018). Every instance ended with the reopening of the border crossing.

This leads directly to a third question: how do informal institutional arrangements remain in equilibrium, and how do they change? More recent works in institutional theory describe how changes in the overall balance of power between groups affected by the regulation impact institutional design and performance (Khan Reference Khan2010). An analysis of institutional change needs to begin with considering the interests and “holding power” of formal and informal actors. However, based on the characterisation of informal institutions discussed here, this is not enough: it also needs to be extended to their informality itself, as different actors may have heterogeneous preferences over how impersonal, for example, an informal institution is.

The institutions I describe offer multiple examples of changing informal institutions. As described earlier, Moroccan soldiers on the border with Algeria stopped collecting bribes from smugglers operating in very low quantities at roughly the same time as customs officers at the border crossing with Melilla did the same. This occurred in late 2010, at a time when the Moroccan government had good reason to be concerned about protests and social pressure, and was framed locally as a subsidy to the poorest traders. Even more significant changes in 2011 occurred at the Ras Jedir border crossing in Southern Tunisia. As the capacity of security forces was weakened in the context of the 2011 revolution, bribe levels at the border crossing dropped to zero, before increasing again from 2014 onwards. It is noteworthy that informal traders, who had financially benefitted from the absence of bribes, formed an association and lobbied state representatives for the return to a fixed bribe level. Anticipating the power of security forces to rebound and fearing a crackdown, there was an interest in re-establishing stable and predictable, albeit costly, regulatory institutions which were in line with the overall balance of power (Gallien Reference Gallien2015). Similarly, a leading official in a relevant ministry described the arrests of multiple smugglers in the summer of 2017 not as an attempt to enforce the law, but to reinstate a “certain equilibrium:” “we need to get back to an acceptable level of smuggling for both the state, and the social peace. That is not an official goal, but that is the goal.”Footnote 23

Similarly, we see examples of the characteristics of informal institutions changing as a result of changes in the balance of power. With the 2011 revolution in Tunisia, the influence of the Trabelsi family, which had used their connection to the presidency in the country to monopolise both formal and informal rent streams, collapsed (Freund, Nucifora, and Rijkers Reference Freund, Nucifora and Rijkers2014). As a result, the trade in selected licit goods that had previously been organised through patronage relationships, such as sport clothing, became regulated impersonally under the wider agreements for the Ras Jedir border crossing. With shifting preferences and shifting levels of trust among Libyan actors involved in the negotiation, we also see the agreement at the Ras Jedir crossing changing from being unwritten prior to 2017, to being written in the winter of 2017, and then unwritten again. Both cases also illustrate the importance of detailed analyses into the preferences and organisational structures of actors involved in informal trade networks—I will return to this point later.

Considering negotiations around the informal regulation of illegal economies provides an insightful perspective on the concept of state capacity. The literature on the distributive politics of enforcement already suggests that the non-enforcement of formal rules does not necessarily reflect on state capacity, identifying the inelasticity of enforcement to increased resources as an indicator of forbearance (Holland Reference Holland2016). Observing the negotiation of informal regulation can help to break down this relationship into its components, including the organisational structure on both sides and their respective motivations, and analyse the regulatory consequences of additional investments in enforcement.

In the context of smuggling networks, such an analysis is particularly relevant in considering the effects of new security infrastructure. Typically, these are imagined as “enhancements of state capacity,” through new institutions in a context of no regulation, or as a new formal institution in a context where they are competing with “subversive” informal institutions. However, if we recognise the real regulatory role of informal institutions in this context, new border security infrastructures are in fact interacting with pre-existing regulatory frameworks. Often, these are not immediately obvious to policy makers, especially from the perspective of the international community, and they risk disrupting informal regulatory arrangements, being bypassed through them, or subsumed into them. As informal trade with Morocco has been profitable for the Spanish enclave of Melilla, the construction of expensive new border fortifications, primarily aimed at deterring migration, have remained porous for smugglers. The effect of new interventions on illegal trade flows hence cannot be predicted without careful consideration of pre-existing regulations, as well as the political economy superstructure that creates and sustains them.

Concluding Remarks

As I have argued, explanations of the vast scope of smuggling in North Africa that focus on “a lack of security infrastructure” (Timmis Reference Timmis2017), poor surveillance, and corruption, are at best incomplete. The region’s “border problem” is not one of “tomatoes and terrorists,” passing along the same routes, across generally porous borders, far from the eye of the state. Instead, the search for its origin needs to begin with the interrelations between informal institutions, formal security infrastructure, and the political economy superstructure from which they both emanate. The state needs to be brought back into the study of illegal trade, not through its absence or corruption, but through an analysis of its regulatory role and its distributional consequences.

This applies beyond the context of North Africa. The dynamics I discussed have served as an empirical challenge to traditional conceptions of informal regulatory institutions in political economy scholarship. The observations that informal institutions can operate impersonally can be written down, and can contain third-party enforcement all support a case for the elimination of a priori assumptions about informal institutions, beyond their creation and communication outside of officially sanctioned channels. Instead, their status with respect to personalisation and enforcement, but also with the necessity of social trust, their size and their efficiency should be understood as conditional upon the political environment in which they are embedded.

I have presented questions to provide the starting point for analyses into the political environment that conditions how and why states engage in informal regulation, asking how different actors can benefit from regulatory informality, what kind of political relationships can emerge from it, and how it remains in equilibrium. There are significant opportunities for further research in every one of these questions—giving a complete account of them even for the local context discussed here goes far beyond the scope of this article. This is not limited to the study of illegal economies, but applies to the wider set of scholarship in political science that builds on the assumptions of mainstream institutional theory such as scholarship on political settlements, non-state governance, or business-state relationships.

In order to unpack these issues, institutional scholarship would benefit from additional research into organisational forms at the intersection between states and informal regulation, looking beyond patronage and clientelist relationships, analysing how information is spread and managed, and expanding on the work done on forbearance in recent years. The question of how to analyse state capacity in a sense that distinguishes between formal and informal regulatory capacity also requires further conceptual discussion. In these endeavours, political science scholarship will benefit from methodological innovations that combine deep contextual knowledge generated through ethnographic methods with the opportunities for inference offered by comparative or quantitative research designs. However, as a precondition for these analyses, research on informal institutions needs to shed misleading misconceptions about their key features. Instead, the nature of these features and which factors shape them should be taken as the empirical questions and as opportunities for new inquiry. That is the research agenda that this paper has aimed to contribute to.

Supplemental Materials

Appendix 1: Methodological Notes on “Informal Institutions and the Regulation of Smuggling in North Africa”

Appendix 2: Translation of the Memorandum of Understanding for the Procedures at the Ras Jedir Border Crossing in January 2017

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719001026