Introduction

Estimates of the prevalence in the United Kingdom (UK) of non-malignant life-threatening illness in childhood may be as high as 1.2:1000 children, four times higher than previous estimates (Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Stallard, Lewis and Mastroyannopoulou2001). Further estimates suggest that in an average sized community with a population of 80 000 children and young people up to the age of 18 years, around 7800 will have a long-term condition and 4000 will have a physical disability (Department of Health (DH), 2009). Although often considered to predominantly be an issue of ageing, in the UK 15% of children under five years of age and 20% of the 5 to 15-year age group are reported to have a complex long-term condition, with the likelihood of this increasing according to socio-economic circumstances (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Buck and Ham2005). Lenton et al. (Reference Lenton, Stallard, Lewis and Mastroyannopoulou2001), DH (2009) and Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Buck and Ham2005) show that individuals in these categories require the services of more than one organisation. At the time of this study, the Department for Children's Schools and Families (DCSF), (2008) – now the Department of Education – posited that children with discrete needs caused by a condition that is usually lifelong and who require additional support from more than one agency are categorised as children with complex needs. Thus, there is no agreed definition of complex needs/conditions. This article adopts the DCSF's position of the definition of children with complex needs/conditions.

Studies have highlighted that in families with a child with complex conditions there is an association between the severity of the condition/technology dependence of the child (ie, children who use more than one medical device to compensate for the partial failure or loss of a vital body function) and greater strain on family functioning (Kirk and Glendinning, Reference Kirk and Glendinning2004; Mulvihill et al., Reference Mulvihill, Wingate, Altara, Mulvihill, Redden, Telfair, Pass and Ellis2005). Among such families, there is also reported higher unmet needs in provider relationship outcomes, especially in relation to the families’ needs for effective coordination of services (Kirk and Glendinning, Reference Kirk and Glendinning2004; Mulvihill et al., Reference Mulvihill, Wingate, Altara, Mulvihill, Redden, Telfair, Pass and Ellis2005). Families caring for a child with complex needs have been found to have to negotiate inflexible and cumbersome organisational systems in order to access respite care (Doig et al., Reference Doig, McLennan and Urichuk2009) or even information (Kirk and Glendinning, Reference Kirk and Glendinning2004), often with detrimental consequences to their own health and well-being (Wang and Barnard, Reference Wang and Barnard2004; Kirk et al., Reference Kirk, Glendinning and Callery2005; MacDonald and Callery, Reference MacDonald and Callery2008). Poor support for families to manage their child's care needs, coupled with ineffective communication systems and discharge planning, has also been associated over the past decade with children with complex conditions spending longer than necessary in healthcare settings (Stalker et al., Reference Stalker, Carpenter, Phillips, Connors, MacDonald, Eyre, Noyes, Chaplin and Place2003).

Most children with long-term or life-threatening conditions receive care from specialists such as community children's nurses. International evidence suggests that community-based nursing interventions, which address the family's stressors, tasks and concerns and which focus on the family's unique set of coping strategies, may decrease distress and improve child and family functioning (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Handley-Derry, Costello, Kauffmann and Dillon1997), although work in the UK suggests that nurses can be limited in the degree to which their care is actually individualised and recognises the input of parental expertise (Kirk and Glendinning, Reference Kirk and Glendinning2004; Kirk et al., Reference Kirk, Glendinning and Callery2005).

In the UK in recent years several key policy initiatives have provided foundations for the configuration of services to more effectively address the needs of children and their families with complex conditions. The white paper Every Child Matters (ECM; Department for Education and Skills (DfES), 2004) sets out the national and local frameworks for services for all children with the aim of building services around the child and to improve the life chances of all. Coordination of services has been recognised by the government as a long-standing problem across all children's services. This recognition has been heavily influenced by key failures in child protection systems (Laming, 2003; Santry, Reference Santry2009). The National Service Framework for Young People and Maternity Services (NSF; DH and DfES, 2004) and Aiming High for Disabled Children (DfES, 2007) are examples of two policy documents that specifically address the needs of children with complex needs, focusing on access to and availability of key services, and the provision of seamless high-quality services in responding to the needs of these children.

Under the Children Act 2004, providers and commissioners of children's services (Children's Trusts) have the responsibility to improve the quality of services for young people and children with complex needs by implementing multi-agency working. Initiatives such as the ‘Team Around the Child’, which should be built around the development of an integrated model of service delivery, involves the appointment of a ‘Lead Professional’ who has the principal organisational and liaison role between all agencies involved in the team. The Strategy for Children and Young People's Health (DH, 2009) also established some funding for services for children and young people with complex needs, including short breaks, equipment and wheelchair services, although any additional financial resources have not been ring-fenced (Every Disabled Child Matters, 2009).

Consequently, in the light of these policy developments how far might the care and support for children with complex conditions have developed at the local level of service provision? Moreover, has the experience of families qualitatively improved from the embattled position highlighted in previous studies? How are specialist professionals functioning to support the needs of children and their families? This paper reports on an evaluation that aimed to map and characterise the way in which services for children with complex needs were provided in one large UK, National Health Service (NHS) Trust in the light of a changed policy context.

The aims of the study were to:

i) Identify and descriptively map the key characteristics of the model of service delivery in operation; and

ii) Explore the user, carer and professional experience of service provision. This included an exploration of congruity and mismatch between the different stakeholder groups.

Methods

A single exploratory case study methodology was employed for this evaluative study in which the unit of analysis is the service provision for children with complex long-term conditions and needs in one NHS Trust. Case study research is particularly appropriate when a holistic understanding of ‘cultural systems of action’ (ie, interrelated sets of activities engaged in by actors in a given social situation) is required (Snow, Reference Snow1991). Yin (Reference Yin2004) identifies the exploratory case study as a means of increasing understanding of organisational phenomenon, of which little is previously known.

The evidence collected in this case study research came from a range of sources in an attempt to increase construct validity. Yin (Reference Yin2004) outlines documentary and archival evidence and interviewing as key sources for case study research. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews and focus groups with service users and a range of health professionals who were involved in providing services. In addition, data were collected through the analysis of local policy documents. Excluded from the study were children and their families who were the subject of either current or ongoing child protection proceedings or complaint proceedings against the NHS.

Participants and recruitment

The Lead Nurse for Children's Services of the Trust was a member of the steering group and had access to all the families with chronically ill children. In order to preserve confidentiality, the decision was made by members of the steering group that the Lead Nurse write to each family that met the inclusion criteria of the study. Included in the letter were the study information sheet, consent forms and researcher contact details. Letters were sent to 50 families who met the inclusion criteria. Families who agreed to take part in the study contacted a member of the research team to arrange an interview. Families with terminally and chronically ill children who attended a weekly support group at the hospital were contacted directly by the research team to inform them about the study. The local support group is a body of people who meet with health professionals and contribute to emerging and ongoing issues within the community about caring for chronically ill children with complex needs.

Professionals were recruited via the Lead Nurse for Children's Services of the Trust. These included speech and language therapists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, community nurses, school nurses, health visitors and community paediatricians.

Procedures

Parent and child interviews were arranged by direct contact between the interviewer and parent. These interviews were mostly conducted in the family home and one at the parent's place of work. Parents who were recruited from the support group preferred to be interviewed as a focus group. A member of the research team attended a group meeting to present the research and to answer questions that arose from the presentation as well as from the study information sheets. A focus group was arranged for the following week.

Interviews with stakeholders and key professionals were arranged by the interviewer and took place at the professionals’ place of work or by telephone if this was more convenient. A focus group was conducted with community nurses in preference to individual interviews because of their own time constraints and work commitments.

A semi-structured interview schedule was used for both the focus groups and individual interviews. The interview questions in both the focus groups and individual interviews reflected the aim of the study, that is, to map and characterise the way in which services for children with complex needs were provided in the light of a changed policy context. Interviews with parents and children started by asking them to describe a typical day of the child, to talk about their understanding of their child's condition and the impact these have on their lives.

The interview schedule was pilot tested and did not change substantially as a result. Interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and was audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Documentary review

The documents chosen for this review included national and local policy documents concerned with the implementation of policy, which provided contextual information on relevant initiatives such as the implementation of Children's Trusts: the Common Assessment Framework and Team Around the Child. This review also informed the development of the analysis and was triangulated with the results of the interviews in order to set the experiences of service users and health professionals within the policy context.

Ethics

Approval from Central Office for Research Ethics Committees (COREC) was sought and the research team was advised that the study was deemed to be service evaluation and did not require full Research Ethics Committee review. Publication of results was permitted. The research team applied British Sociological Association and British Psychological Society guidelines for ethical research and standard COREC informed consent procedures, including the right to withdraw.

Analysis

In-depth thematic analysis was undertaken of the verbatim-transcribed qualitative data. This employed open coding and subsequent thematic development and refinement, including the search for disconfirming evidence (Boyatizis, Reference Boyatizis1998). The transcripts were each coded by two researchers to allow for critical discussion and reframing and refinement of the coding frames, thus meeting the criterion of trustworthiness. Connections and links were sought between the developing themes, thus resulting in a map or story around the participants’ accounts from the interviews.

Findings

Sample

Seven parents of children with complex needs were interviewed via one-to-one in-depth interviews or in focus groups, six of those with the mother and one father. The age range of children was from three years to ten years and their conditions included cystic fibrosis, spina bifida, microcephaly, biliary atresia and tuberous sclerosis. Two young girls with complex health needs took part: one aged six years was interviewed with her mother and the other aged ten years was interviewed independently. The parents of both children were also part of the study. These two young children were capable of making independent decision to participate in the study.

Seven parents from the support group took part in a focus group. The children represented had a range of complex needs and their ages ranged from 1 to 16 years of age. No child took part in the focus group.

Eighteen individual in-depth interviews were undertaken with relevant stakeholders and key professionals across the multidisciplinary teams. Recorded interviews included exploration of the professional perspective on the current model of service delivery, how decisions are made regarding allocation of care pathways, discharge and admission planning. Data were also collected from a wide range of individuals, for example, community paediatricians, nurses, therapists and teachers. Selection criteria required that the professionals have significant input into children's and families’ care within the study locality. Four community nurses took part in the focus group.

Major theme: communication

This paper is focused in terms of an exploration of the user and professional experience of service provision. A number of other themes that are not central to the analysis presented in this paper were also raised during the interviews; in particular, parents felt they encountered difficulties in coping with their child's illness, the stress incurred and the need for respite care.

The major theme that emerged from the data was that of communication. Communication among various entities was described and clarified and examples are presented below. The practitioners’ perspectives on the quality of communication and the areas for improvement underlie and pervade their views on the quality, organisation and structure of the service (Figure 1). Parental experiences relating to the quality of communication was an important factor in how the family perceived the overall quality of care (Figure 2). A ‘communication gap’ was highly likely to result in parents becoming critical of services and disappointed overall. Perspectives around communication focused on two aspects: (i) coordination between services, and (ii) professional communication to parents and young people with regard to family participation in decision making. These two aspects are explained below.

Figure 1 Practitioners’ perspective about communication

Figure 2 Parental experiences of communication

(i) Communication and coordination between services

The effectiveness of communication between different professionals, agencies and service sectors was recognised in the professional accounts as being the key challenge facing the organisation of services. A significant determinant of ineffective communication identified by many professionals concerned the overall coordination of services. The concept of a Lead Professional (It is recognised that in some settings the lead professional is referred to as a case manager. However, in this study's setting, the individuals are referred to as lead professionals.) was seen to be essential in helping families navigate the range of services provided by different organisations because of the complexity of relationships and liaison across organisations:

I think each child has to have a lead professional, a key worker, but again, it's identifying who that lead professional is and how many cases can a lead professional manage… But depending on the size of the packages you can't manage a service and be a lead professional for numerous families and liaise with all the other agencies (Community Paediatrician 1).

Parents also consistently highlighted the need for a designated case worker or lead professional who could effectively navigate a healthcare and social care system that often seemed more daunting and complex to manage than their child's condition:

Yes it would be nice to have a case worker or somebody that says ‘oh yes I know, we need to go and talk to somebody over there’. Rather than me scratching my head and thinking ‘oh we'll try over there’ and they go ‘oh no you need to talk to somebody over there’ (Parent 3).

Conflicting professional advice and an absence of a holistic, ‘whole family’ approach to care planning was illustrated by one parent who felt she was caught between the dietician who wanted her son to consume more calories and the speech therapist who insisted that he should eat more textured food irrespective of the food's caloric value:

You can't satisfy both… and there's this constant battle the whole time between different specialists who are just looking at their own narrow aspect and nobody looks at the whole thing (Parent 1).

Professionals often reported reduced continuity of care because of an ‘information gap’ whereby communication between the community services and the hospital was not felt to be functioning in a coordinated manner and the effectiveness of follow-up was hampered as a result. Comments were particularly focused around lack of communication about children's admission and discharge leading to disjointed care, ineffective use of time endeavouring to obtain information about the child, leading in some cases to interruption in treatment:

When children have been admitted to hospital who have a community paediatric consultant, the information doesn't always flow back the other way, so when a child is discharged the community paediatrician might not even know they've been in hospital and not have any details of the admission (Community Paediatrician 2).

Community nursing staff reported similar problems about the lack of information on discharge from some hospitals. They argue that lucid information is required for effective follow-up of patients. In some cases, they received poor responses to direct requests for information:

….although our paediatricians may make referrals to tertiary centres, for example orthopaedic input or gastroenterology or something like that, very often we're not getting letters coming back to tell us what went on and what is needed, even when we phone to find out (Community nurse 2).

Problems with communication between services were also illustrated by parents’ experiences with the Direct Admission System, introduced for children with complex health needs to bypass assessment in Accident and Emergency (A&E) as per the recommendation for immediate access in the NSF (DH and DfES, 2004). However, parental experience indicated that the process was no more efficient than going through the normal A & E procedures for triage:

…I can't remember a single time that we've been in A&E when they have had our file. We had to go through the same routine and wait just as long (Parent 5).

(ii) Professional communication and family participation in decision making

The majority of parents’ views were that the services they experienced had left them poorly informed both about their child's condition and how the available services might support families. The ability to learn how to communicate effectively with professionals was perceived by some parents to be key in getting heard and their needs met. Parents perceived that an assertive communication style and a demand for services rather than a supportive dialogue were more likely to achieve results:

Unfortunately, I suppose those who shout get heard. And if you're fairly articulate you do get what you want, but there must be a lot of people out there sitting around waiting for something and it doesn't happen or it takes longer (Parent 4).

Many professionals recognised the embattled position of parents and felt their role should encompass assisting parents to develop the communication skills and levels of understanding about the health system that are necessary to manage and navigate services effectively:

I feel the parents have a huge fight on their hands and it's actually to try and empower the parents, give them the information, be quite proactive in knowing what it is they're going to want just through our experience and through working as a team (Community Paediatrician 2).

Parents reported that they actively sought out sources of information on their child's condition and that over time parents acquired a considerable knowledge base about their child's condition. Sources external to the health service such as support groups and other media including the Internet were the most valued in terms of improving the parents’ knowledge base. One point of tension between parents and professionals concerned how health service professionals responded to their situated knowledge base. Parents tended to feel that their ‘expert parent’ status was often not respected by professionals or responded to defensively:

I think sometimes doctors don't realise that we know so much about our children; we've not got any medical training but we've had so much input over the years that we often can, and do, know what's wrong with our child. You have to go and tell the doctor what's wrong and it doesn't always go down very well (Parent 5).

Moreover, because their pivotal role in caring and their knowledge base was not sufficiently acknowledged by professionals, parents felt that they were not always included in the decision-making process relating to their child's care, for example parents reported that they were often not informed when changes were made to the care regime, particularly when their child was hospitalised:

You're expecting X to happen and it doesn't and it's ‘Oh no, oh we've changed that on the round this morning’ (Parent 3).

On the other hand, one child participant had a different experience with hospital staff. She explained thus:

Yeah, they were really nice. I had to go there because of my operation – it's called a colostomy – it helps you to poo, they were gonna swab it ‘cos I got gunge there so they had to use this stuff to get it so it goes away… they tell me what they're gonna do and then they say right and it's gonna include this and that then at the end they tell me what I have to do and they teach me (female child 1).

Discussion

The findings have characterised the ways in which services for children with complex needs were provided in one large UK, NHS Trust by identifying key issues of the current service delivery and exploring the views of service users and professionals. The findings also indicate that the levels of discontent experienced by service users are in direct contrast to the policy goal of promoting an enabling service for people with complex needs (DH, 2004; 2009). The goal draws upon existing approaches to practice in which health professionals work in partnership with patients, carers and families, with the intention of increasing self-management skills. This discussion will focus on two issues. First, a proposed enabling service model, and second an explanation of how the systems and the hierarchy within which professionals and service users must operate impact on them. These two issues relate to the findings.

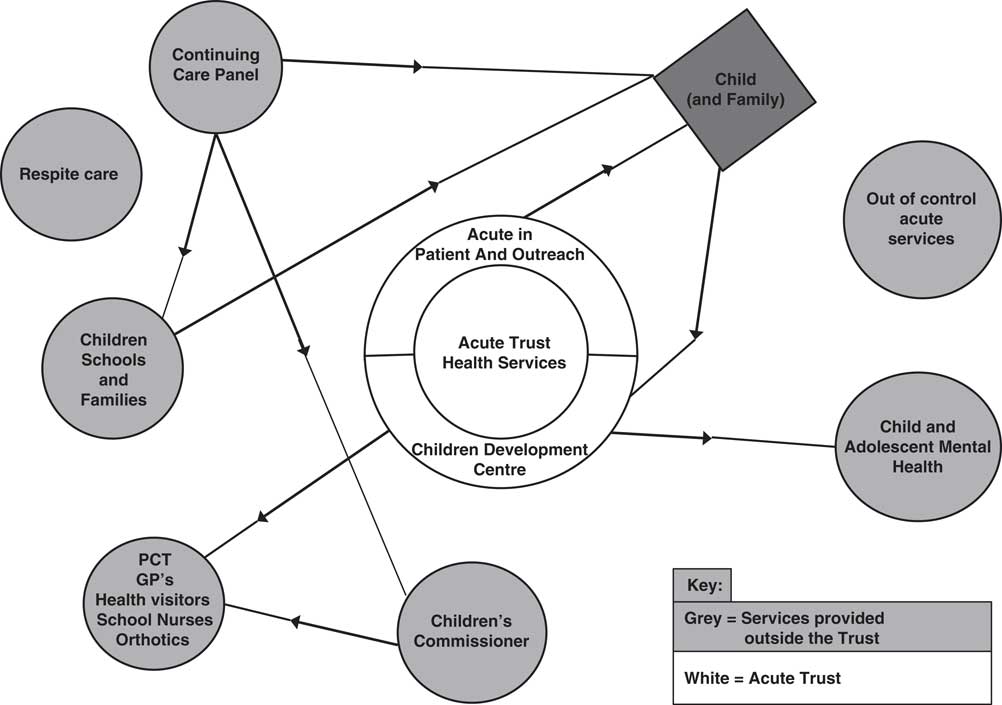

We argue that there is pressing need for a model that empowers parents and patients with knowledge of how to navigate the healthcare system. Health professionals also need to work in a way that produces a positive therapeutic relationship that enables parents to make informed decisions about care by working with families to identify individual needs from the latter's perspective. Thus, the proposed enabling service model (Figure 3) would place the child and family at the centre of care delivery to facilitate pathways to meet their needs while encouraging parents to make informed decisions that best suits their circumstances. The proposed service model would be one where practitioners and parents can work across the system according to the needs of their child. Appropriate access to mainstream universal services, including a flexible range of social care provision, would be a key feature of the model. This would require economic investment strategies, which focused on this client group. The proposed service model needs to be equipped with appropriate communication systems to manage the care of young people with complex needs returning from local inpatient and out-of-area admissions.

Figure 3 Representation of an enabling system

The stark reality of caring for a young person with complex needs as portrayed by parents in this study concurs with other studies (Yantzi et al., Reference Yantzi, Rosenberg, Burke and Harrison2001; Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Noyes, Sloper and Shah2005). However, the findings have led to broader considerations of how systems and hierarchy impact on professionals and service users. In order to appreciate such complexity, a general systems theory (Bertalanffy, 1968) approach is used to facilitate greater understanding of how systems interact, interrelate, impact each other and contribute to outcomes. Moreover, systems theory has an established reputation relevance in health care (Sturmberg, Reference Sturmberg2004; Dooris, Reference Dooris2005), particularly in complex service delivery (Keating, Reference Keating2000). Briefly, the basic premise of general systems theory is that all systems share certain characteristics, such as communication, internal and external influences on, say, health, that allow them to function as systems (see Bertalanffy, 1968 for full discussion). Systems are also hierarchically organised (Bertalanffy, 1968; Benkö and Sarvimäki, Reference Benkö and Sarvimäki2000) as they are composed of different levels; in this study, these were individual (the user/carer), local (eg, local clinical care) and national (eg, out-of-area specialist hospitals). The service user in this study can be seen as a system interacting with other systems, such as doctor, nurse and therapist, in a clinical hierarchy context, which are interdependent and influence each other, culminating in an outcome. An important feature of systems theory, which is relevant for this study, is the focus on communication.

Cross-cutting issues were evident in the communication and coordination between services and in professional communication and family participation in decision making. Previous evaluations elsewhere have found professionals to be entrenched in professional silos unwilling to function as multidisciplinary team members (Hall and Weaver, Reference Hall and Weaver2001; Cava, Reference Cava2008). In contrast, the central findings presented in this paper relate to the function and character of the systems that support effective team working. In particular, the problems encountered by families were generated by an absence of a whole system-level model of care, rather than resistance or failings by individual professionals. Families frequently reported that individual professionals were personally committed to delivering a good service.

The current findings show that families not only need to navigate the labyrinth of the healthcare and social care system, but also be adept at distinguishing the responsibilities and expertise held by practitioners of different professions. Following diagnosis, families reported ambiguities and tensions in communication between professionals, particularly with their continuing needs. Tensions were further emphasised between both professionals and service users, especially if the child was under the care of specialist consultant located outside the local health authority. Mutual respect and recognition of knowledge and expertise were identified as key factors in family–practitioner relationships and where service users experienced professionals to focus on their specialised service delivery, thus compartmentalising care, a fragmented view of services was perceived. This supports both a systems and hierarchical approach to service delivery, as well as concurring with Sloper et al. (Reference Sloper, Jones, Triggs, Howarth and Barton2003) that coordination of services, assessments and appointments through multi-agency care planning and a single key worker to liaise with and assist the family should be consistently available. According to the current policy, all children with complex needs should have access to the ‘Team around the Child’ and be allocated a ‘Lead Professional’ as a basic entitlement; however, in this study these key services have not been universally implemented. The concept of a lead individual to provide a single point of contact has been promulgated in policy documents from the 1970s (eg, Court Report, 1976; Warnock Report, 1978, as well as those policy documents mentioned in this paper). Furthermore, a resource pack for developing key worker services for families with a disabled child has been developed by Mukerjee et al. (Reference Mukherjee, Sloper, Beresford, Lund and Greco2006). These authors’ work on key worker services was positively evaluated in 1999 (Mukerjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Beresford and Sloper1999).

Edmond and Eaton (Reference Edmond and Eaton2004) confirm the lack of evidence surrounding information provision and staff competence in children with complex healthcare needs. Communication, a basic principle of systems approach, is essential to allow parents and young people to be part of the decision-making process and to express their concerns and exercise their own autonomy, in a situation where they otherwise may have little control. Further examples of systems and hierarchical approaches to care were the inequities felt by parents that in order to negotiate the system of care they required assertiveness and a willingness to complain, positions that many parents reported feeling uncomfortable having to develop.

Two implications for policy and practice emerge from this research. The first is for services to be coordinated in a way that assists parents and young people in understanding the services available to them and for a key worker to be allocated to each family – a family-centred approach to the provision of services. Although there is national and international evidence that supports the positive contribution of service provision, which incorporates the principles of family-centred services (Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, King, Law, King and Evans1998; DH, 2004), this is not universally implemented in the UK. The second implication is the availability of more support for the caregiver. The value of time for oneself or with the family is of crucial importance to the mental and physical well-being of the caregiver and the family as a whole.

These findings must be interpreted within the scope of the present study's limitations. One limitation is the lack of ethnic and cultural diversity within the study population. It is unclear from this study how ethnicity impacts on individuals and families with long-term conditions and complex needs. Another is that primary care relationships for those with long-term conditions are long lasting and patients may feel they do not wish to jeopardise the relationship they have with their health professional because of the former's vulnerability.

Conclusions

In summary, parents experienced both health and social service communication challenges when seeking care for their child. These challenges can be located within a general systems theory and hierarchy approaches to understand the complexity of service provision. Although their expertise in caring for their child provided them with some deft in navigating the healthcare and social care system within which they must operate, lack of clarity about provision criteria proved to be a constant barrier for obtaining assistance. From this study, the drivers for an enabling service would involve social and economic strategies that focus on coordinated, dedicated services for children and their families with complex needs. This would provide a care culture, which is patient centred rather than determined by existing structures and professional hierarchies within health systems. Emphasis should also be placed on the accessibility of sources of information and provision of practical help in order to alleviate crisis. On the basis of knowledge of these dimensions, services for those with complex needs could be targeted more effectively.