The First Presbyterian Church of Port Gibson rests along the residential tree-lined Highway 61 in the center of Port Gibson, Mississippi. Constructed in 1859, the salmon-colored building remains the largest house of worship in the small town, with six impressive stained-glass windows on each side. The current pastor Michael Herrin attributes the building's size to architectural rivalry among churches in Port Gibson during the years just before the Civil War. According to local legend, the Roman Catholic church triggered this competition in 1857 when it rebuilt its church with four windows on each side, followed by the Methodists who constructed a church the length of five windows, who were then surpassed by the Presbyterian church with six windows down the sanctuary. The striking German gothic structure also contains one of the most unique steeples in the United States, topped not with a cruciform but instead a twelve-foot hand, gilded in gold leaf and pointing upward toward the sky (see Figure 1). The hand was originally carved out of wood and lore credits its inspiration to both a church elder who spotted a carved hand in a local shop window and the pastor of the church at the time the new building was erected, who often gestured to heaven during his emphatic sermons. It has been recognized since its first appearance on top of the church as “a reverent sign from a people who know and love their God.”Footnote 1

Figure 1. Steeple of the First Presbyterian Church of Port Gibson, which is topped with a gold-leaf hand pointing upward rather than a cross. Ben May Charitable Trust Collection of Mississippi Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The grand Port Gibson Presbyterian church, complete with a pointing hand that reminded antebellum passersby of the hierarchical order of Christian faith, was built during a time of rapid social change. Established as a frontier community by Samuel Gibson in the early nineteenth century, by the mid-1830s Port Gibson had become one of the most important cotton production hubs in the entire state. One traveler to the town observed that “many of the owners of neighboring plantations have their residences here, which gives the place an air of wealth and grandeur.”Footnote 2 These residences matched the aesthetic of First Presbyterian and other churches in Port Gibson, which were built during a time when the elite planter class was rapidly converting to evangelical religion and membership at the largest or wealthiest church in a community verified high social status.Footnote 3 The gilded hand atop the steeple of First Presbyterian Church of Port Gibson was an imposing symbol of wealth and power on display for slaveholders who enjoyed the suggestion that God was on their side and sanctioned their supposed power in a rigidly hierarchical slave society. Elaborate architecture was not the only aesthetic influence that served the planter ideal of social hierarchy. Inside the church was a less visible but no less powerful force: Music.

This article examines the politics of race in southern antebellum hymnody and the music pedagogy methods used by slaveholders in the religious instruction of the enslaved. White evangelical church leaders in the antebellum South utilized sacred music to project and maintain social order. Racial politics refers to the ways in which Black and white evangelicals sang hymns, listened to each other, and responded to these performances, often in ways that promoted or resisted racial hierarchy and white hegemony. Beginning in the 1830s, as the planter class converted to evangelicalism, white missionaries who were interested in proselytizing to both Black and white people were also forced to confront the issue of slavery and its place in southern religion. Although slaveholding families accounted for only 30 percent of white southerners, the wealth and political power attached to the planter class ensured that evangelical clerics (many of whom also owned slaves) continued to support the institution.Footnote 4 Intent on appealing to slaveowners, these clerics found ways to combine the egalitarian evangelical missionary vision—conversion available to all regardless of race—with the planter imperative of enslaved submission. Preaching paternalism and the importance of a divine hierarchical order in the household became central to the white missionaries’ message to the enslaved. Although the conditions of enslavement varied widely between southern households and plantations, hymns nonetheless represented a white social power at work within the soundscape of evangelical religion. Hymns served a useful purpose not only in upholding proslavery theology, but also by educating Black singers in white musical practices. Singing hymns became another way for slaveholders to regulate the lives of the enslaved. Planters and overseers forced the enslaved to sing hymns during working hours, expected a joyful sound in the multiracial church, and discouraged African Americans from singing their own spirituals during discreet slave worship meetings. Mark M. Smith refers to these political musical dynamics as the “plantation orchestra” that slaveowners meticulously conducted.Footnote 5 This article identifies evangelical hymnody as a quotidian repertoire of this metaphorical orchestra. I argue that cultivating a hymnic landscape across the South was an act of sonic domination that the planter class designed to secure and enhance its power, much like building grandiose churches and placing visual markers of spatial domination on the top of steeples.Footnote 6

Sonic domination provided a method of control that allowed white southerners to uphold white supremacy and prevent slave rebellion.Footnote 7 Enslaved African Americans met these efforts with resistance, operating against but within the framework of sonic domination.Footnote 8 By mandating the kind of hymns that were allowed in slave worship and the method in which they were sung, the planter class attempted to discipline the lives of those whom they enslaved and the complex relationship between Black and white people in the South. Jennifer Lynn Stoever explains how in the United States of the nineteenth century “sound both defined and performed the tightening barrier whites drew between themselves and black people,” and the music of African Americans was “marked by whites as ‘black’ and therefore of lesser value and potentially dangerous to whiteness and the power structures upholding it.”Footnote 9 The sonic dominance of regulated hymnody provided the soundtrack for a false reality of the wholesome plantation that planters wished to establish and acted as a form of cultural erasure in the lives of African Americans, who were forced to replace their own varied musical traditions with those of European, namely English, origin. Slaveholders attempted to fashion a homogeneity across diverse Black religious soundscapes by introducing English hymns.Footnote 10

Sonic domination was an all-encompassing force in the antebellum South. It pervaded every aspect of southern life, although its effects were not always generative to the power and success of the planter elite. Evangelical hymnody served as merely one template among many to promote white dominance. What makes this brand of domination sonic, rather than solely hymnic, is the saturation of hymnody in everyday evangelical life. Hymns were sung in a variety of worship services, recited in Sunday schools and other educational settings, published in primers and catechisms, and prayed in domestic spaces. Analyzing how such hymns were utilized in churches and on plantations highlights the presence of sonic politics in evangelical culture. Several scholars have emphasized the influence of cultural ideologies and individual perception in the racialization of sound.Footnote 11 White slaveholders attempted to use sonic domination to impose social order informed by these racial sonic identities. Thus, sonic domination was more than just a weapon or tool. It was a dynamic mode by which power was asserted in highly imbalanced settings and a hierarchal system of ordering entire societies. The sonic cannot be reduced to a sound event but is instead an ideological construction dependent on systems of power and resistance.

I. Singing the Right Thing the Right Way

Many evangelical ministers across the South, particularly in the Old School Presbyterian Church, worked hard to reinforce the social hierarchy of the planter class in their religious institutions. Clergy in Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist churches were most active in proselytizing the enslaved for the benefit of slaveholders; however, some Episcopal, Lutheran, and Roman Catholic churches also promoted a proslavery Christianity. Denomination mattered little compared to location, and churches in areas with a larger plantation economy and wealthy elites tended to be more involved with missions to the enslaved. By the time evangelicalism became a popular elite movement in the 1830s, several of the most successful pastors involved in that undertaking had significant ties to the plantation economy; many owned their own plantations and slaves, and others married into plantation families.

One of the founding clergymen of the Port Gibson church, James Smylie, amassed a 1000-acre plantation in Amite County that he named “Myrtle Heath.” Smylie was one of the first people in Mississippi to offer a biblical defense of slavery.Footnote 12 Written and published in 1836, Smylie's justification of the institution argued that the proper family structure was both hierarchal and patriarchal, placing emphasis on paternalism and the responsibilities of the slaveowner to instruct and discipline those that they enslaved. This perspective grew in popularity over the next decade until most evangelical denominations in Mississippi and the broader South were teaching similar doctrine within their Sunday schools and from their pulpits. Over time, as more planters viewed it as their Christian duty to instruct the enslaved in the evangelical tradition, this religious proslavery explanation was also reinforced on the plantation. Between the years of 1848 and 1851, James Smylie was recognized by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of the United States as a “missionary to slaves.”Footnote 13 This title was not uncommon for evangelical ministers beginning at mid-century, and slave missions served an important social function in the South prior to the Civil War.

Slave missions were not a new interest for white Protestants. The Anglican Church had been sending missionaries to the West Indies and America through the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel since the early eighteenth century. As Katharine Gerbner demonstrates in Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World, the church had modest success in converting enslaved Africans during the latter half of the century.Footnote 14 White evangelical missionaries pleaded to slaveholders to convert those that they held in bondage, proclaiming it their Christian duty and moral responsibility as “masters” to attend to the religious instruction of the people that they enslaved. Under the guise of paternalism, slaveholders fashioned a façade of benevolence to mask the exploitation of the enslaved.Footnote 15 In the nineteenth century, the planter elite and missionaries used paternalist rhetoric to justify the institution of slavery; in short, slavery produced more Christians. Such is the sentiment of one stanza of a hymn included in English missionary Joshua Marsden's 1810 hymnal composed specifically for Black slaves in Bermuda:

Written in part to quell theories among the planter class that evangelicalism could not coexist with slavery, Marsden's verse makes it clear that by the early-nineteenth century white evangelicals increasingly viewed slavery as “ordained of God.”Footnote 17 In the South during the decades leading to the Civil War, slave conversion and religious instruction became of central importance to slaveowners and evangelical clergy alike.Footnote 18

There were several non-religious benefits that came from slave conversion for the planter class, and many times slave missions were inspired by secular motives. Religious instruction offered slaveholders the opportunity to “acclimate” enslaved people to the specific social customs of the South, rooted in white hierarchy and the Christian tradition. To these slaveholders, an acclimated slave was aware of the basic tenets of Christianity, able to communicate effectively in the English language, and disciplined in both their labor and obedience. The term served as a polite stand-in for the cultural submission that the planter class desired to cultivate. Many slave advertisements in antebellum newspapers mentioned the importance of an acclimated slave. One advertisement in a Mississippi newspaper explained that “the difference between acclimated and unacclimated Negroes will constitute a sufficient inducement for one to put himself to some trouble to examine.”Footnote 19 One method of acclimation that slaveowners pursued was religious instruction, which occurred both in church and on the plantation.

Slaveowners and missionaries used the sonic environment of religious instruction as one method of managing the “noise” of slave worship practices.Footnote 20 Slave catechisms became a popular pedagogical device in the mid-nineteenth century South, and evangelical missionaries devoted an increasing amount of time to proselyting the enslaved.Footnote 21 These catechisms were generally designed for oral instruction and featured short question and answer sections, prayers, and hymns that were easy to memorize. E.T. Winkler, a Baptist minister who led congregations in Alabama and South Carolina, viewed hymns as moralizing agents and “a source of enjoyment and improvement which scarcely anything else can supply.”Footnote 22 Other southerners, mostly musicians and physicians, believed that music had the power to civilize; however, in the case of sacred music, evangelical ministers like Winkler were highly selective about what qualified as appropriate hymnody.Footnote 23

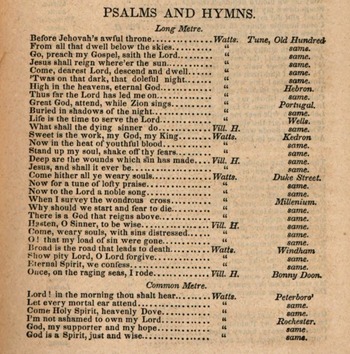

Both text and tune mattered to white evangelical clergy when selecting hymns for inclusion in their slave catechisms. Charles Colcock Jones, a prominent Presbyterian minister and one of the first advocates for the religious instruction of enslaved African Americans in the South, encouraged white missionaries “to teach the scholars hymns and psalms, and how to sing them.”Footnote 24 Jones provided an extensive list of hymns appropriate for slave worship in his 1837 catechism (see Figure 2). The majority of hymn texts included in Jones's catechism were derived from Isaac Watts—an English dissenting poet and cleric who had gained immense popularity among evangelicals throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—although a few come from U.S. sources, such as Asahel Nettleton's 1824 collection Village Hymns for Social Worship.Footnote 25 Most texts were popular in the English and U.S. evangelical traditions, and titles such as “Alas! and did my Saviour bleed,” “Jesus, lover of my soul,” and “Rock of ages, cleft for me” suggest that Jones compiled the list with white hymn preferences in mind. Most of the included hymn texts did not relate specifically to slavery or plantation life, but instead offered a variety of hymns pertaining to conversion and Christian duty.Footnote 26

Figure 2. A list of hymns suggested by Charles Colcock Jones for the religious instruction of enslaved people. Popular eighteenth-century English tunes such as Old Hundred, Hebron, and Duke Street are prominent. Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

One text that Jones included, written by English cleric John Newton, uses the word “plantation.” Newton's eighteenth-century text was likely written without the nineteenth-century slave societies of the U.S. South in mind and instead recalled British colonies or farming communities. Still, Jones specifically selected “Saviour, visit thy Plantation,” and his ownership of a 941-acre plantation and 120 enslaved people suggests that he thought of the nineteenth-century southern plantation when choosing it.Footnote 27 The hymn calls for a revival of religion across the plantation—a metaphor for the Christian world at large and, in Jones's case, a specific southern plantation setting—praying for “mutual love” among all Christians:

Hymns included in slave catechisms were almost exclusively English in origin, and with the exception in Jones's catechism, none of them referred to the plantation or the institution of slavery. However, the paternalism that served as a common defense of slavery was prevalent in many hymns through reference to the household and larger Christian community. Through religious instruction and conversion, slaves became members of the “Christian family,” and, according to Baptist minister E.T. Winkler, there was no sound sweeter to a slaveholder's ears than the “harmony of a pious household.”Footnote 29 In a literal sense, this harmony often included Black singers because enslaved people who worked in the plantation house were often drawn into the intimate sacred rituals of the slaveholding family. Winkler cited the fifth commandment in his slave catechism, pairing the lesson regarding “honor to superiors” with a popular nineteenth-century hymn titled “How blest the sacred tie that binds”:

In the context of the lesson, this hymn highlights the importance of religious paternalism to evangelical missionaries who were trying to appeal to southern slaveholders. Although some lines such as “to each the soul of each how dear” make ambiguous reference to Christian individuality, an emphasis on “kindred minds” throughout the hymn underscores slave obedience in the process of religious instruction. Slaveowners “whose hearts, whose faith, whose hopes are one” with those that they enslaved became the ideal because this ideology of paternalistic unity promoted religious subordination that prevented slave rebellion. Giving enslaved people “something profitable to sing,” as Charles Jones put it, meant restricting their song to English hymnody that both appealed to the planter elite and coincided with tunes that sounded in harmony with the social and religious order to which they subscribed.Footnote 31

Hymn tunes were as important as texts to the authors of slave catechisms. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, hymn tunes were not fixed to specific texts as they are in modern evangelical worship. Instead, most hymnals included lyrics only; hymn tunes from designated tune books or a song leader's memory were paired with these texts based on their meter. Jones took great interest in the tunes that were paired with English hymns, listing appropriate ones next to each text and defending the little musical variety in his introduction: “The tunes affixed to them are few in number, and of the plainest kind, though they are among the best in use in the churches.”Footnote 32 In his manual for white missionaries, he also noted that “the tunes should not be intricate but plain and awakening,” reflecting his interest in the devotional character of the hymns alongside a preoccupation with English worship practices that was present across many catechisms.Footnote 33 Tunes presented in slave catechisms were straightforward, generally set in three- or four-part homophony with a strophic structure; harmony more complex than the occasional secondary dominant was rare and refrains rarer still. Simple tunes made focusing on the text easier for congregants, a form of ritual discipline that promoted the memorization of lyrics and subscription to a specific theology. Many well-loved English tunes were included in Jones's list of hymns, including “Old Hundred” and “Duke Street.” Traditional Scottish tunes like “Bonny Doon” and “Auld Lang Syne” appear on the list as well, reflecting not only the Scottish roots of Presbyterianism in the United States, but also the growing interest in folk hymnody across the country during the Second Great Awakening. Some hymn tunes included in slave catechisms were taken from the “scientific tradition” that valued European musical aesthetics and sought to reform U.S. church music to a more refined state. Scientific hymnody was established during the first decade of the nineteenth century in New England, and the influence of this tradition across the southern hymnic landscape was a rare occurrence of national unity during an increasingly sectarian time in U.S. social consciousness.Footnote 34 The most common of these tunes was “Hebron,” which was composed by northern composer Lowell Mason and included in his 1832 hymnal Spiritual Songs for Social Worship. Jones paired the tune with the text “High in the heavens, eternal God” and Winkler included it with “How blest the sacred tie that binds” in a hymnal that he compiled titled The Sacred Lute.Footnote 35 All of these—English hymns, folk hymns, and “scientific” hymns—represent a European hymn tradition that was popular in the United States and endorsed by the planter elite as appropriate for both plantation slave worship and multiracial worship in antebellum churches.

Some southern evangelical ministers wrote hymns that reflected their understanding of the white social order and published them for congregational use. Unsurprisingly, these texts were not included in slave catechisms, but did gain popularity in Sunday school hymn collections and congregational hymnals published for predominately white usage. One example was written by Winkler and published in his 1855 hymnal. “Our land, with mercies crowned” contemplates the divine provenance of the United States and the God-given authority of those in power:

Although these hymns were published for predominately white usage to mark white authority to Black Christians singing on the plantation, they also revealed that authority to multiracial congregations during Sunday morning worship. Slaveholders often brought enslaved Christian women and men to church with them, and although these services were intended to provide a model of civilization for the enslaved, evidence suggests that Black and white members did experience a small amount of genuine fellowship.Footnote 37 As a crucial element of this fellowship, hymn singing highlighted Christian unity while continuing to emphasize the unequal power dynamic within southern antebellum churches.

Hymnals served a political function in the church—one of the most important institutions in southern social life before the Civil War. These books were one medium through which sonic domination was maintained by white evangelical clerics. As tensions between abolitionists and proslavery advocates rose during the 1850s, the issue of slavery became one of the popular discussions in the church, including during committee meetings for the creation of new hymnals. For instance, one 1861 Presbyterian proslavery pamphlet explained that “in the preparation of the Hymn book…a single verse of a certain hymn containing anti-slavery sentiments was omitted. It was charged that the omission was made under the influence of pro-slaveryism,” the author noted, criticizing one minister who denied that such accusations had abolitionist tendencies.Footnote 38 In the nineteenth-century South, planter interest in the institution of slavery grew larger than the church itself and therefore infiltrated Black, white, and multiracial communities of faith. King Cotton had usurped “King Jesus” in his own house.

II. Southern Religious Expression and the Racialized Church

Comparing Black and white religious expression, particularly musical expression, was a critical method through which white people constructed sonic racial identities during the antebellum period.Footnote 39 White evangelicals across the South used English hymns and African American spirituals from the multiracial church to form the racialized Church—capital c—that was fashioned on difference, exclusion, and white supremacy. In Christian theology the “capital c” Church delineates the religious body outside of a specific building or denomination and the entire Christian community that transcends time and place. This institution did not meet exclusively on Sundays, but instead was a constant presence in the everyday life of the enslaved as an institution that imposed control and cultural submission. The racialized Church enabled sonic domination to become a totalizing presence in the antebellum South, resisting confinement within the walls of a church building. Its rigid and hierarchal position was diametrically opposed to the “invisible institution” that enslaved Christians subscribed to—an organization that was “both institutional and noninstitutional, visible and invisible, formally organized and spontaneously adapted.”Footnote 40 Slaveholders policed slave singing during multiracial church services, labor in the fields, and private religious gatherings on the plantation. Hymns became a significant aspect of the “sound [that] was sliced into discreet packets and parceled out as masters saw and heard fit.”Footnote 41 Furthermore, the planters’ own devotional singing informed and reinforced a proslavery version of Christianity that was important to the structure of southern society that valued church and slavery above all else.

White evangelicals developed their ideas regarding appropriate slave worship practices first and foremost in the church services that they shared together. These services included slaveholding evangelicals alongside African Americans and members of the white working class. During the antebellum period, it was common for enslaved people to join their “masters” on Sunday morning, usually from a slave gallery in the rear of the sanctuary. White commentary on congregational singing during Sunday morning services demonstrates what varieties of hymns were being sung and how the singing of Black members weighed on the minds of white congregants. One witness of a Charleston Presbyterian service later noted, “you have doubtless heard sublime music in the house of God; but if you never heard Old Hundred, Mear, and Coronation, sung by two thousand blacks, you have yet to learn what an engine music can be made for lifting the soul above this earth on which we stand.”Footnote 42 This account suggests that white evangelicals were keenly aware of the musical contribution that Black voices provided and that the tunes so enthusiastically sung held special meaning in a multiracial worship setting. The support of slave voices made it clear to this spectator that “there was no need of an organ in Zion Church that evening,” which was indicative of just how much the sound stood out to this specific spectator.Footnote 43 The emphasis on Black voices together with no word on white voices reflects a preoccupation with the vocality of Black singers and the status quo privilege that white singers maintained.

Occasionally, Black congregants were given permission to lead singing in multiracial services. This leadership, although supervised by white authorities and offered to an exclusive few in the enslaved community, demonstrated a ritual inclusivity among evangelical churches that was true to their revival roots and allowed African Americans some leadership positions. One Methodist minister reflected on services that his grandmother attended: “At these services the negroes were allowed to attend and to participate. She had one old man who was mighty in prayer and occasionally he was called on to lead, and he did it with fervor. They all joined in the singing, and I have never heard such Church music since that day.”Footnote 44 Slaveholders were known to designate a select few Black congregants to lead for them to exemplify “proper” church etiquette and hymn singing practices for other Black people in attendance. Even though independent Black churches did exist in the South, and some dated to the eighteenth century, most enslaved people only experienced institutionalized corporate worship from slave galleries in predominately white evangelical churches.Footnote 45

After the planter elite converted to evangelical denominations at the end of the Second Great Awakening, religious enthusiasm that took on an emotional display waned considerably in southern churches. The genteel culture that the planter elite and the developing middle class subscribed to emphasized stoicism and restrained emotion. Formal liturgies with a seasoned choir took place inside grand churches and many of these evangelical churches were in alignment with the planter class and their proslavery brand of Christianity.Footnote 46 Black religious expression continued some of these earlier revival practices blended with West African traditions; as Randy Sparks notes, “in their ritual and practice, black Christians emphasized a more expressive and participating worship where music and ecstatic behavior expressed different religious expectations.”Footnote 47 White evangelicals showcased their preference for unemotional worship practices and demonstrated how obedience might be rewarded to the enslaved in the pews by rewarding compliant African Americans with the opportunity to lead singing in multiracial worship services.Footnote 48 Slaveholders enjoyed and even promoted the religious expression of enslaved worshippers’ singing as long as it was the “right” thing sung the “right” way.

Regulation of hymn singing did not stop at the church. As several scholars have written, slave labor was imbued with an obligation to sing, and the “aural time” that singing provided maintained order during the workday on the plantation.Footnote 49 “Slaves were expected to sing as well as to work,” wrote Frederick Douglass in his autobiography, adding that “a silent slave was not liked, either by masters or overseers.”Footnote 50 Slave singing provided the façade of plantation tranquility that slaveholders aimed to create in order to defend the institution. One 1860 article from The American Cotton Planter and the Soil of the South noted that, “of all the charms of Southern rural life there is nothing more charming to our ear than the songs of a cheerful band of negroes, while merrily engaged in their labors, and beating time with axe or hoe to their simple yet melodious strains.”Footnote 51 The doctor who wrote the article also assured his readers that “musical proclivities…greatly increase the happiness of the negro, by cheering him in his labors, and consequently, that they through the influence of the music over the body, are highly conducive to health.”Footnote 52 Thus, singing created a romanticized view of the plantation and increased the productivity of slave labor according to proslavery writers.

Evangelical slaveholders attempted to control what kind of songs the enslaved sang while working. Although planters were largely unaware of hidden meanings in spirituals, they were eager to replace “nonsensical” lyrics and rowdy tunes in these songs with English hymns.Footnote 53 Underneath vague Protestant language and vocables, spirituals recounted the horrors of slavery and anticipated an eventual, if not eternal, liberation. Their meaning, however, was lost on Southern ministers like Charles Jones, who maintained that “one great advantage in teaching them good psalms and hymns,” referring to the English standards that he included in his catechism, “is that [slaves] are thereby induced to lay aside the extravagant and nonsensical chants, and catches and hallelujah songs of their own composing.”Footnote 54

Slave singing occurred in a variety of forms across the plantation, all of which were carefully regulated by overseers and slaveowners. When the enslaved were not singing while working in the fields, they might have been heard singing during religious meetings designed by white evangelicals for African Americans. Some plantations had a small chapel near the slave quarters where Black and white ministers preached and enslaved congregations worshipped. During these services, English hymnody was often used, especially if supervised by white missionaries. Thomas H. Jones, a minister and former slave from North Carolina, recalled singing the English hymn “Come, ye sinners, poor and needy” during his conversion experience; this hymn was one that was included in Charles Jones's list of appropriate hymns for the enslaved in his 1837 catechism.Footnote 55

It was a pleasant reassurance of social harmony for slaveholders to hear hymns that white evangelicals approved to be sung during plantation revivals and prayer meetings. But, as with almost every aspect of slave life, planters often attempted to regulate African American hymn singing to occur only when supervised. Singing at the right time as decided by slaveholders was a crucial element in maintaining social order on the plantation. Thomas Jones mentioned in his autobiography that when he and a group of enslaved people sang hymns of joy in one slave cabin, his master “soon sent over a slave with orders to stop our noise, or he would send the patrollers upon us.”Footnote 56 Christian slaves living on plantations did find ways to worship in secrecy, often placing a pot upside down on the floor in the middle of a cabin to catch the sound of prayer and singing of hymns.Footnote 57

Just as the enslaved sang in devotion, so too did slaveholding families. Often evangelical planters would require their families to attend a private morning and evening prayer, where they would read verses from the Bible, pray together, and sing hymns. Private hymn books served a variety of purposes in family devotions, and hymns did not always need to be sung in order to fulfill familial religious expectations. Christopher N. Phillips explains the long tradition in England and the United States of reading (and praying on) hymn texts, which continued throughout the nineteenth century in the South, in his book The Hymnal: A Reading History.Footnote 58 One slave narrative by William H. Robinson recalls certain hymns sung during these family worship services. An air, sung to any tune in long meter, written for morning worship rejoices in the divine promise that enabled righteous slaveowners:

Another hymn designed for use during evening services prays to God for the retention of the enslaved on their plantation:

It is possible that these hymns may have been embellished for dramatic flair, but it is still extremely likely that slaveholders did focus their prayers and hymns on their Christian duty as “masters.” Improvised prayers might have addressed plantation or household events, which included enslaved people, and hymns interspersed between these prayers and biblical readings were contextualized with the institution of slavery in mind. Paternalistic hymns such as “Blest be the tie that binds” were popular in devotional settings in addition to their regular use in congregational worship and slave catechisms. These hymns were not uncommon outside the South, and U.S. Protestant culture on the whole reinforced patriarchy throughout the nineteenth century. However, southern evangelical churches and slave catechisms subtly overstated a hierarchal and paternalistic version of Christianity to strengthen the power of elite white men.

Slaveholders attempted to carefully regulate the hymn singing of the enslaved in both life and death. A dignified death was a quiet death according to their genteel sensibilities. Singing on or around the deathbed was a common practice in both Black and white communities throughout the nineteenth century, and the planter class had specific ideas about appropriate deathbed rituals and music. Examples of such a ritual occurred in the death scenes of Richard Goode Wharton, a Confederate medical doctor from Mississippi, and his wife, Mary Catherine Wharton. Wharton's daughter remembered that “when the yellow rays of the setting sun lighted up his room, he would often have his favorite hymn sung, ‘Jesus, Lover of my soul.’”Footnote 61 Likewise, while on her deathbed Mary Wharton often “repeated slowly and emphatically two stanzas of ‘Jesus, Lover of my soul,’ and seemed much comforted by it.”Footnote 62 Richard Wharton's death was romanticized in a poem published in a local newspaper shortly after, and the last stanza of the poem defends his dignity in death:

Such a sentimentalized death scene contrasts drastically with how the death of Black people was perceived in the white imagination. Black death scenes, which “took the form of singing, chanting, praying, clapping and a highly personal bidding of farewell to the corpse in which each mourner paused at the coffin to say goodbye,” were viewed as noisy, emotion-filled, and—perhaps most important to plantation overseers—time-consuming.Footnote 64 A postbellum poem by Irwin Russell, one of the first white poets to write in a Black dialect, reinvented a Black death scene according to the cultural expectations of the planter elite:

This poem highlights a presumed ritual unity between white and Black religious expression in the white southern imaginary. There are several issues with the authenticity of Russell's poem, including the tortured Black grammar that he devised when writing it. His musical testimony is also suspect. “Rock of Ages” was a common funeral song among white evangelicals during the antebellum period; however, music sung on and around slave deathbeds tended to be of African American composition.Footnote 66 Spirituals that welcomed death were particularly popular. One slave narrative explained that the enslaved “feared not death, but would rather welcome it with songs, for we…felt that we should receive the ‘Crown of Life.’”Footnote 67

White evangelicals taught African Americans English funeral hymns in hope of influencing their musical expression surrounding death and funerals. The Isaac Watts hymn “Hark from the tomb a doleful sound,” for instance, became extremely popular at slave funerals, but not as white missionaries expected. Many enslaved congregations sang their own distinct versions of this hymn, altering lyrics, and using tunes that were embedded with African American musical elements. David R. Roediger explains how the text varied widely from plantation to plantation, sometimes as a result of oral transmission and other times an intentional reinterpretation of English lyrics.Footnote 68 While members of the evangelical planter elite insisted on teaching the enslaved specific hymns, how the slave community interpreted those hymns was beyond the elite's control. Spirituals and altered English hymns displayed resistance from the deathbed to the grave—an assertion of freedom just before a final freedom.

III. Black Resistance through English Hymnody

White evangelicals in the antebellum South sought to influence Black religious culture through the hymns that they taught the enslaved. A form of intended cultural erasure, English hymn texts and tunes highlighted a sonic dominance that was important to the perpetuation of southern social culture and the slave society that it maintained. These efforts were met with resistance from the Black community that was both overt and covert. Frederick Douglass mentioned his occasional defiance of his captor's orders to lead devotional hymns:

The exercises of his family devotions were always commenced with singing; and, as he was a very poor singer himself, the duty of raising the hymn generally came upon me. He would read his hymns, and nod at me to commence. I would at times do so; at others, I would not. My non-compliance would almost always produce much confusion. To show himself independent of me, he would start and stagger through with his hymns in the most discordant manner.Footnote 69

Here, Douglass's refusal led to confusion and a disturbance of the devotional liturgy. Because he had the advantage of being literate, and therefore being able to read hymn texts and sing them from the family's devotional hymnal, Douglass was able to insert his own authority in these worship services, meeting the slaveholder who was leading them with a resistance that diminished his authority. Since most enslaved women and men were not able to read English hymn texts, nor did they have access to English hymnals, Douglass is an interesting exception. However, some fugitive slave advertisements mention fugitives taking hymnals with them when they escaped the plantation, demonstrating the importance of these books to African Americans who regarded English hymns as significant to the fabric of their own religious lives or who struggled to become literate.Footnote 70 White hymnody had a significant influence on Black religious expression, although many times it was not in the same ways that missionaries and slaveowners had intended.

Spirituals were a vital part of the African American religious tradition during (and after) slavery. These songs shaped and were shaped by Black theology that centered on salvation and liberation. Scholars such as Sterling Stuckey and Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. highlight the lineage between spirituals and African rituals, too.Footnote 71 The genre showcases one of the many ways that Black inventiveness was used to circumvent the oppressive power of slaveholders and proslavery evangelicalism.Footnote 72 Spirituals also had ties to the English hymnody that white evangelicals sang and taught to the enslaved. John Andrew Jackson, a former slave from South Carolina, explained that spirituals were “composed of fragments of hymns, which we had heard sung at the meeting-houses and camp-meetings of the white men…the negroes compose their songs chiefly from snatches of hymns which they hear sung by the white people, interpolated, it is true, with now and then a line of the original.”Footnote 73 Hymn texts, often by Isaac Watts, served as lyrical building blocks for spirituals:

This sentimental text appealed to African Americans both enslaved and free who suffered under the oppression of white authority. Eileen Southern argues that many spirituals originated in free Black religious communities, particularly Richard Allen's Mother Bethel Church in Philadelphia. However, slave narratives suggest that spiritual composition also likely occurred in the antebellum South.Footnote 75 Many narratives describe the improvisatory nature of slave worship that produced spirituals designed to secrete Black liberation theology from white listeners. Wherever spirituals originated, English hymnody such as “There is a land of pure delight” was crucial to the composition and dissemination of songs like the popular “Roll, Jordan, Roll”:

Spirituals were often sung alongside English hymns during slave worship services. Hymns such as “The voice of free grace cries, ‘Escape to the mountain!’” were popular because they overtly mentioned escape and freedom (even if their original meanings were altered in the context of slave worship).Footnote 77 Spirituals also contained themes of escape and freedom, although they were often disguised in allegory and vocables. Many slaveholders who heard these spirituals assumed the lyrics to be nonsensical and often used them to reaffirm their own notions of white supremacy. However, spirituals were filled with hidden meanings that served as a powerful source of resistance in the Black community. They called out the injustice of white supremacy and horrors of slavery while pleading to God for deliverance, a prayer of hope and “a faith in the ultimate justice of things.”Footnote 78 Frederick Douglass noted in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass that the language of the spirituals “to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.”Footnote 79 Spirituals provided the enslaved a source of discreet resistance against white authority and also helped shape their own religious identities.

Another way that the enslaved developed distinctly African American hymnic expression was through the practice of lining out. Originally used by protestants beginning in the seventeenth century, this method of psalm or hymn singing allowed one leader (usually someone who owned a hymnal and was able to read) to sing one line of a hymn at a time, to which the congregation would respond by repeating each line until the hymn was finished. Aside from a few denominational sects predominately in Appalachia, white evangelicals discontinued this method of singing in worship services during the First Great Awakening of the 1740s.Footnote 80 However, lining out remained popular in the Black church throughout the nineteenth century. Because Isaac Watts wrote many hymns that the enslaved sang, lining out became known as “Wattsing” and had specific ties to African American worship. Still, there was some level of incongruity in a predominantly oral culture singing the poetry of an English cleric. The practice represented “the inherent oppositions between the African oral heritage of slave and hegemony of writing that was set against them,” William T. Dargan explains, and “‘Dr. Watts’ came to stand for what was inaccessible in outward form and meaning, but ownable, knowable, and unassailable in its essence.”Footnote 81 Lining out preserved some musical elements of West African traditions, particularly the call and response method that was common in ritual music. The musical tradition also offered the opportunity for heightened emotionality while singing because of the slow pacing that it provided. For instance, in his autobiography Thirty Years a Slave, Louis Hughes recalled a slave preacher who “solemnly worded out” the Watts hymn “Am I a soldier of the cross” and being “touched in hearing him give out the hymns.”Footnote 82 Through the practice of lining out, both enslaved and free African Americans fashioned a unique musical religious identity that provided agency during the antebellum period.

Just as white sacred music practices helped shape the musical religious expression of the enslaved community, Black spirituals influenced the hymns of white evangelicalism. One Methodist minister criticized the emergence of popular hymnody in 1819, specifically condemning hymns that had their origins in secular music and slave spirituals:

We have too, a growing evil, in the practice of singing in our places of public and society worship, merry airs, adapted from old songs, to hymns of our composing often miserable as poetry, and senseless as matter, and most frequently composed and first sung by the illiterate blacks of the society.Footnote 83

The addition of refrains to white gospel music became popular just before the Civil War, and the tradition was continued through the rest of the century by hymnwriters such as Fanny Crosby, Ira Sankey, and Philip Bliss. Although the inclusion of hymn refrains was not distinctly African American, spirituals popularized their use during a time when English hymnody was mainly strophic. The language of spirituals emphasized an intimate relationship with the divine and the everyday experiences of the enslaved. The publication of Slave Songs of the United States in 1867 codified many of the most famous spirituals in print for the first time, and thus with greater access to these songs, northern poets and composers began altering the hymnic language that was common to white worship to include more intimate textual themes. As Jon Cruz explains in Culture on the Margins: The Black Spiritual and the Rise of American Cultural Interpretation, northern abolitionists collected these songs throughout the Civil War to highlight the evils of slavery with emotional appeal, and by the time Slave Songs was published the spiritual genre was heard by northerners with a “critical humanistic interest in the music of African Americans.”Footnote 84

IV. Who is on the Lord's Side?

During the first year of the Civil War in December 1861, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America designed a committee “to revise and prepare for the use of our Church a suitable Hymn Book.”Footnote 85 Due to the nature of the war, the depletion of resources, and the fact that the South had never been well equipped for book publishing, the hymnal did not appear until 1866, and even then southern editors made very few changes from the original 1845 hymnal. There were, however, a few Sabbath school hymnals published during the war for the use of children. One titled A Collection of Sabbath School Hymns contained a hymn that represented both the evangelical mission and the nation's conflict in a militant language:

Having spent three decades before the war defending the institution of slavery as synchronous with the Christian tradition both past and present, proslavery evangelicals in the South believed entirely that they were on the Lord's side of the battle, and hymns like this one demonstrate their certainty in that belief.

Drew Gilpin Faust, in her book on the success of revivalism among Confederate soldiers, has noted that singing psalms and hymns was a popular pastime in confederate camps.Footnote 87 In constructing their own national identity founded on evangelical theology and proslavery ideology, Confederate clergy and church leaders made sure that civilians and soldiers were well-stocked with hymns that furthered their wartime vision. Such was the purpose of “God Save the South,” a poem written by George Henry Miles turned into the national anthem of the Confederate States of America. The song is reminiscent of an English hymn and was often sung to the tune of “God Save the King,” which was also common in U.S. evangelical worship. The southern position on slavery collides with militant rage in the sixth verse:

English hymnody remained a significant part of southern religious life for both Black and white evangelicals throughout the Civil War. Hymns were one way that white southerners defended their mission and developed community. During this time, the face of sonic domination changed and took on a greater nationalistic and patriotic character instead of playing a subversive role to Black autonomy. Some hymns were deemed more appropriate than others during the war. For instance, one minister in Alabama was accused of being an “abolition traitor” when he announced the following Isaac Watts hymn during a weekday service:

On the battlefield hymns served as a method of prayer and praise to wounded soldiers. A soldier who was wounded during the Battle of Shiloh later recalled singing “When I can read my title clear” when another wounded soldier nearby began singing along with him. “I could not see him, but I could hear him,” the story continued, further explaining that “he took up the strain, and beyond him another and another caught it up, all over the terrible battle-field of Shiloh. That night the echo was resounding, and we made the field of battle ring with the hymns of praise to God.”Footnote 90 This familiar and well-loved hymn provided a musical comradery and religious harmony against the soundscape of war and death.

“When I can read my title clear” was also popular in the slave community, and one can imagine how it might have been interpreted by African American soldiers in the Confederate army during the war:

The promise of freedom and literacy combined with the absence of fear and sadness that this verse describes would have provided an uplifting message of hope during a time of uncertain conflict across the nation. Singing was as crucial to war as it was to plantation labor, only during the war the enslaved or recently escaped had control over the repertoire that they sang and when they sang it.Footnote 92 Booker T. Washington recalled how the enslaved sang about freedom with increased frequency and vocality in their spirituals near the end of the war:

As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom. True, they had sung those same verses before, but they had been careful to explain that the “freedom” in these songs referred to the next world, and had no connection with life in this world. Now they gradually threw off the mask and were not afraid to let it be known that the “freedom” in their songs meant freedom of the body in this world.Footnote 93

As emancipation grew nearer, songs with more overt abolitionist connotations were sung by Black people in the South in addition to their established canon of spirituals. Black soldiers in the Union Army often sang while marching, and one Mississippi newspaper recalled white reactions to this singing, saying, “Friday morning the negro soldiers marched through singing ‘John Brown.’ They were the first we had seen, and the sight was galling, but they were under good discipline and behaved well.”Footnote 94 What was infuriating to white southerners late in the Civil War, then, was not the order of the soldiers but the sight (and quite possibly the sound) of them singing a Union song that had its origins in revivalism hymnody. English hymns, spirituals, and American folk hymnody played an important role in the aural landscape of the war, and southerners both Black and white were attuned to this singing.

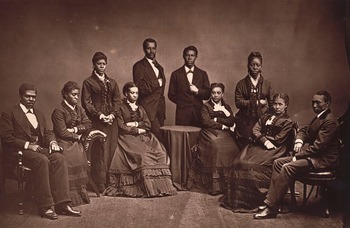

The Civil War and freedom muted the sonic dominance of white hymnody from an institutional perspective, replacing it with a common exchange of compositional elements between southern African Americans and white hymnwriters and publishers in the North. While postbellum independent Black congregations—following the lead of their antebellum predecessors—were able to sing and worship according to their own religious preferences, many still used English hymns during church services. Instead of singing these songs in the European hymn tradition, however, they made them their own, arranging and performing them in line with the cultural and religious practices that they had developed during slavery. A certain convention of hymn singing remained in American thought throughout the nineteenth century, and white evangelicals continued to view their style of singing as superior to that of Black churches and ensembles. For instance, the Fisk Jubilee Singers—who sang spirituals in a European classical style that emphasized the use of homophony and tonal harmony—were portrayed by white reviewers as an ensemble that was more “civilized” than many African American performances but still inferior to white performers (see Figure 3).Footnote 95 Furthermore, aside from a small group of abolitionists in the North, white evangelicals were not interested in African American spirituals as a form of sacred music; rather, a Romantic interest in the exotic made the genre successful in concert both in the United States and abroad. Sonic domination as a widespread systematic strategy did not survive the Civil War, but its legacy was detectable in the aesthetics of singing far beyond emancipation.

Figure 3. The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a successful Black vocal ensemble that promoted concert arrangements of spirituals and toured across the United States and Europe in the late nineteenth century. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Hymnody was a powerful social tool in the antebellum South, and the influence of this religious medium continued through the Civil War. White evangelicals often used English hymns as a method of controlling the enslaved population through promoting paternalistic Christian theology, reducing the number of slave hymns sung, and promoting the singing of hymns across a variety of southern spheres—religious and secular, public and private. The sonic dominance of English hymnody upheld the social order of the planter elite that sustained the institution of slavery. African Americans responded to these missionary efforts with a resistance embedded in song and used English hymns as a structural element in the composition of spirituals that developed their own distinct musical and religious identities. Furthermore, evangelical hymns became essential to the sound of the Civil War and took on a variety of forms and meanings to enslaved and free Black people in addition to southern white evangelicals. Emancipation dissolved the tight grip of white sonic domination on Black religious expression, but independent Black churches that appeared across the postbellum South continued to use English hymns that were learned in slavery as a critical element of worship, albeit within their own stylistic and theological traditions. In peace and war, slaveholders and those that they enslaved used hymns as one method to read the social and religious environment that surrounded them.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Stanley Hastings for revealing sources located in his family archives that are pertinent to this article. I am also indebted to Glenda Goodman, Mia Bay, Francis Russo, and two anonymous readers for their thoughtful comments on various drafts of this article. This research was assisted by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Chase Castle is a PhD candidate in Music at the University of Pennsylvania. His research explores American revivalism across the nineteenth century and focuses on the gospel hymn, a popular sacred genre that rose to prominence near the end of the century. He is the recipient of several nationally competitive fellowships and has curated and been a recording artist for many exhibitions. He is also an active organist and choral conductor.