Introduction

In many established democracies, the foundations of democratic institutions are being slowly dismantled as checks on the power of elected leaders are weakened, the franchise is restricted and democratic rights and freedoms are curtailed (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Levitsky and Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Waldner and Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018). According to the latest Freedom House report, fully 25 of 41 established democracies saw their scores decline between 2005 and 2019 (Freedom House, 2020a). Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States were all among the countries registering lower scores.

Canada was not on the list of countries where democracy is under threat, registering a near perfect score of 98 (Freedom House, 2020b), but we should not assume that it is immune to the subversion of democratic norms and institutions. Canada's Westminster-style system accords a good deal of power to the executive, especially when combined with a parliamentary majority. It has even been suggested that Canadian prime ministers are less constrained than presidents in many presidential systems (Bakvis and Wolinetz, Reference Bakvis, Wolinetz, Poguntke and Webb2005). “In the extraordinary conditions created by the COVID-19 crisis,” Brock (Reference Brock2020: 9) observes, “ . . . the long-term peril is that the critical importance of Parliament holding the government accountable for its spending decisions may be eclipsed.” The country's “constrained parliamentarism” has proved an important source of “democratic resilience” (Albert and Pal, Reference Albert, Pal, Graber, Levinson and Tushnet2015: 121), thwarting the government's attempt in March 2020 to grant itself the ability to raise taxes and spend without parliamentary approval until the end of 2021 in order to deal with COVID-19. However, citizens’ dispositions are as critical to the quality of democracy as the proper functioning of democratic institutions (Mayne and Geißel, Reference Mayne and Geißel2018).

From that perspective, Canada's democracy might seem to be in safe hands, given Canadians’ high levels of support for democracy. When asked the importance of living in a country that is governed democratically, the average rating on a 0-to-10 scale in fall 2019 was 8.4.Footnote 1 However, conventional survey questions are likely to overestimate how much Canadians value democracy. Democracy is an abstract concept to which few will have given much thought (Kiewiet de Jonge, Reference de Jonge and Chad2016). Rating democracy highly in response to an abstract survey question does not preclude Canadians overlooking or even condoning the undermining of democratic norms. An unprecedented crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic offers a critical opportunity to assess the extent to which Canadians can be considered reliable defenders of democratic norms and institutions.Footnote 2

We focus on Canadians' reactions to executive aggrandizement. This is a key mechanism through which democratic norms are undermined, as the Trump presidency exemplified (Kaufman and Haggard, Reference Kaufman and Haggard2019; Lieberman et al., Reference Lieberman, Mettler, Pepinsky, Roberts and Valelly2019). It entails “the (at least initially) incremental but systemic dismantling of checking mechanisms that liberal democratic constitutions typically put in place to ensure the accountability of the political executive. This aggrandizement is effected by an elected executive leadership that seeks to defang independent checking institutions” (Khaitan, Reference Khaitan2019: 343). The COVID-19 pandemic has witnessed multiple attempts to limit checks on the executive. Trudeau was not alone in trying to avoid parliamentary scrutiny. Rather than preserving parliamentary oversight by using the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, the British government passed the Coronavirus Act 2020, granting the executive the power to implement sweeping measures without parliamentary scrutiny (Bolleyer and Salát, Reference Bolleyer and Salát2021). The French Public Health Code was amended to allow the government to govern for a month without legislative approval while expanding its regulatory powers (Bolleyer and Salát, Reference Bolleyer and Salát2021). Meanwhile, the Spanish coalition government implemented a “state of alarm” rather than declaring a state of emergency, which would have required prior parliamentary approval (El País, 2021). These examples raise important questions about citizens’ willingness to tolerate such executive overreach.

Drawing on terror management theory and the literature on threat, we develop two hypotheses to explain why Canadians may be willing to condone executive aggrandizement in the face of an unprecedented health crisis. Central to both is the notion that people adopt coping mechanisms when faced with a threat to their safety and security. One way that people cope with an existential threat is to look to their leaders “to deliver us from evil” (Landau et al., Reference Landau, Solomon, Greenberg, Cohen, Pyszczynski, Arndt, Miller, Ogilvie and Cook2004: 1136). The more anxious people are about a threat, the greater their openness to loosening restraints on the power of the executive in the belief that decisive action is needed to address the crisis (Hypothesis 1). A second way that people cope with an existential threat is by supporting policies that are perceived to offer protection against the threat. The desire for protective policies may be so intense that they will be willing to overlook abuses of executive power for the sake of getting those policies implemented (Hypothesis 2). And this might be particularly true if they are extremely anxious about COVID (Hypothesis 2a).

Our three-pronged approach to testing these hypotheses combines observational data and data from two novel experiments. The observational data come from an online survey of 2,322 Canadians and are used to test our first hypothesis. Embedded in the same survey were a vignette-based experiment and a candidate-choice conjoint experiment, which enable us to test both hypotheses. The vignette experiment probed people's willingness to accept a provincial legislature being shut down for the sake of their preferred lockdown policy, while the randomly assigned attributes in the conjoint experiment included the candidates’ positions on the lockdown and their views about checks on prime ministerial power.

COVID-19 and Support for Executive Aggrandizement

The desire for decisive leadership

Central to terror management theory is the phenomenon of mortality salience: humans desire self-preservation while at the same time realizing that death is inescapable. This realization makes for existential anxiety (Greenberg and Arndt, Reference Greenberg, Arndt and A2011; Rosenblatt et al., Reference Rosenblatt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski and Lyon1989). People have various ways of dealing with this anxiety. Particularly relevant for our purposes is a tendency to turn to strong leaders whose appeal “lies in his or her perceived ability to both literally and symbolically deliver the people from illness, calamity, chaos, and death” (Landau et al., Reference Landau, Solomon, Greenberg, Cohen, Pyszczynski, Arndt, Miller, Ogilvie and Cook2004: 1138). From this perspective, “transferring power to and investing faith in a powerful authority” is a coping mechanism for dealing with existential anxiety (1139). Studies conducted following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States have highlighted this mechanism. Subtly reminding people of their mortality increased support for George W. Bush in the run-up to the 2004 presidential election (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Ogilvie, Solomon, Greenberg and Pyszczynski2005) and for Donald Trump in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Solomon and Kaplin2017). Both findings were attributed to the candidates’ perceived ability to protect Americans from further attacks.

The source of the anxiety is quite different, but COVID-19 is certainly an existential threat. As Albertson and Gadarian (Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015: 106) observe, “public health crises tend to scare people at a visceral level.” If terror management theory is correct that “one of the most basic functions that leaders serve is that of helping people manage a deeply rooted fear of death that is inherent in the human condition” (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Solomon, Greenberg, Cohen, Pyszczynski, Arndt, Miller, Ogilvie and Cook2004: 1137), existential anxiety may well make Canadians more willing to overlook or even condone the undermining of democratic norms in order to enable the executive to act decisively to combat the pandemic.

In a similar vein, the threat literature argues that people turn to strong leaders to cope with the feelings of anxiety elicited by collective crises. Differentiating their approach from terror management theory, Merolla and Zechmeister (Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009) emphasize that this coping strategy is not limited to crises that threaten people's physical security but also applies to crises that jeopardize financial and psychological welfare. What is critical is whether a threat evokes a strong emotional response. With both lives and livelihoods at stake, the pandemic clearly qualifies as a collective crisis. According to Merolla and Zechmeister (Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009), such crises can create a sense of powerlessness and loss of control. Even though people can take steps to protect themselves, resolving the crisis is beyond their individual control. In such circumstances, people are likely to put a premium on decisive leadership and be willing to see an expansion of the power of the executive in order to combat the crisis. The authors suggest that this reflects a psychological need to restore a sense of personal security as well as a rational calculation that only decisive action can resolve the crisis. The psychological need for decisive leadership may be especially strong in the face of an unprecedented health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, when even science-based advice can change rapidly and people may be unsure of the best way to deal with the pandemic. Faced with such uncertainty, some people may seek to alleviate their anxiety by placing their faith in a strong executive. Thus, both the terror management literature and the threat literature provide a basis for predicting that the more anxious people are about COVID-19, the more open they will be to weakening restraints on the power of the executive (Hypothesis 1).

The desire for protective policies

Threatening events can also increase people's support for policies that they believe can protect them from the threat (Albertson and Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015). From the public health perspective, the key protective policy in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic has been shutting down all but essential businesses. Fearing for their health and physical well-being, some people will see lockdowns as their best safeguard. However, others may favour opening up to mitigate the dire economic consequences of the lockdowns. Whether they favour opening up or continuing the lockdowns, people may well care more about politicians’ positions on the lockdowns than their respect for democratic norms.

Survey evidence indicating that many Americans were willing to sacrifice civil liberties in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Davis and Silver, Reference Davis and Silver2004) illustrates people's willingness to trade off democratic principles for the sake of security in the face of a collective threat. Pandemics may elicit a similar willingness. Participants in an experimental study were most supportive of policies entailing limits on civil liberties when told about a supposed smallpox outbreak occurring “just last week” (Albertson and Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015). Particularly relevant for our purposes, a survey conducted in Britain, Canada and the United States early in the pandemic revealed people's willingness to support civil-liberties-violating policies for the sake of protection (Cilizoglu et al., Reference Cilizoglu, Heinrich and Kobayashi2021). Moreover, Canadians have proved much more open to COVID-19 contact-tracing apps (which raise concerns about civil liberties) if COVID is seen as a threat to their family members (Rheault and Musulan, Reference Rheault and Musulan2021). Accordingly, we predict that people will be willing to ignore the need for restraints on the power of the executive for the sake of their preferred stance on lockdown policies (Hypothesis 2). If protective policies help to combat existential anxiety (Albertson and Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015), people who were anxious about COVID-19 may be particularly open to executive aggrandizement when such policies are at stake. Consequently, we hypothesize that the greater the COVID-related anxiety, the greater the willingness to sacrifice democratic norms for the sake of the preferred lockdown policy (Hypothesis 2a).

Data and MethodsFootnote 3

To test these hypotheses, we use data from a sample of 2,322 Canadian citizens provided by the survey firm Dynata.Footnote 4 Respondents were excluded if they failed an attention check,Footnote 5 took fewer than 300 seconds or more than 3,600 seconds to complete the survey, and/or selected the same answer for three consecutive batteries of questions that used a 1-to-7 scale. Since partisanship is potentially a key control variable (see below), Quebec residents were not included, given the different line-up of federal parties in the province. The survey was fielded from May 16 to May 28, 2020, and hosted on the online platform Qualtrics. Quotas were implemented for education, age, sex and region to match the 2016 Census. The final sample closely approximates the composition of the adult population outside Quebec (see Table A1 in the appendix).

We use three methods to test our hypotheses. Regressing support for executive aggrandizement on a measure of existential anxiety, plus controls for potential confounders, enables us to test our first hypothesis that greater anxiety is associated with greater willingness to loosen restraints on the power of the executive. The second method is based on a vignette experiment depicting a provincial premier who is willing to shut down the provincial legislature in order to implement their preferred lockdown policy; the third method involves a candidate-choice conjoint experiment that includes a willingness (or not) to ignore legislative or judicial checks among the candidate attributes. Both experiments are designed to test our second hypothesis regarding people's willingness to trade off democratic norms for the sake of their preferred lockdown policy, while also providing additional tests of our first hypothesis.

Method One: Cross-sectional analysis

Our first hypothesis predicts that people who are experiencing debilitating anxiety about COVID-19 are more likely to favour executive aggrandizement. Executive aggrandizement “occurs when elected executives weaken checks on executive power one by one, undertaking a series of institutional changes that hamper the power of opposition forces to challenge executive preferences” (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016: 10). Accordingly, our measure is based on the extent of respondents’ agreement or disagreement with two short statements involving loosening restraints on the power of the executive: “When parliament is obstructing a prime minister's agenda, a prime minister should shut down parliament and govern on his/her own” and “Governments would be more effective if they could just ignore the arguments of those who disagree.”Footnote 6 The two items loaded on a single factor and were combined to form an additive scale (Cronbach's alpha = 0.71). The scale was recoded to run from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the most support for executive aggrandizement. The mean score was .27, but almost 10 per cent of respondents scored above the midpoint (see Table A2 in the appendix for summary statistics for all variables included in the analyses).

Our measure of COVID-related anxiety is intended to capture existential anxiety, an emotion elicited by a perception of threat to one's safety and security that is beyond the individual's control (Albertson and Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015: 8). It is based on responses to two questions: “How often in the last two weeks were you so anxious about COVID-19 that you could not think about anything else, no matter how hard you tried?” and “How often in the last two weeks were you unable to carry out your daily activities because you felt anxious about COVID-19.” The four answer options varied from “never” to “often.” Responses to the two items were recoded and combined to create an anxiety scale (alpha = .84). The scale ranged from 0 to 1, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of anxiety. Almost one-third (31%) of our sample had not experienced any debilitating anxiety about COVID. However, fully a quarter (26%) scored above the midpoint and 10 per cent responded “often” to one or both questions. As expected, anxiety was driven by economic worries as well as health-related concerns.Footnote 7 Respondents who were more worried about the economic fallout and those who were more concerned about the health risks both had an average anxiety score of .30. However, respondents who expressed both health and economic worries registered the highest levels of debilitating anxiety, with an average score of .54. Meanwhile those who were relatively unconcerned on both counts had an average score of only .15.

The models control for various potential confounders. Younger Canadians have experienced higher levels of anxiety during the pandemic than older Canadians (Nwachukwu et al., Reference Nwachukwu, Nkire, Shalaby, Hrabok, Vuong, Gusnowski, Surood, Urichuk, Greenshaw and Agyapong2020). Since Canada is among the countries showing a steady decrease in support for democracy from the oldest to the youngest cohorts (Norris, Reference Norris2017), age could be a common cause of both COVID-related anxiety and support for executive aggrandizement. Following Foa and Mounk (Reference Foa and Mounk2016, Reference Foa and Mounk2017), birth cohorts are based on the decade of the respondent's birth.

Research on support for anti-terrorism policies reports that people with more education did not feel as anxious in the wake of terrorist attacks (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005). This was attributed to experiencing fewer life stressors and a greater capacity for processing probabilistic information. A similar pattern could be expected for COVID-related anxiety, especially given the role of numeric information in eliciting negative emotions (Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Baicker and Boggio2020). There is also evidence that higher levels of education are associated with “democratic enlightenment” (Nie et al., Reference Nie, Junn and Stehlik-Barry1996) and a heightened belief in the importance of democracy (Cordero and Simón, Reference Cordero and Simón2016). Accordingly, education could explain an association between anxiety and support for executive aggrandizement.

The same applies to people's material circumstances: people with lower incomes are likely to be more adversely affected by the economic fallout from the pandemic, and they tend to be less persuaded of the importance of democracy (Cordero and Simón, Reference Cordero and Simón2016). Material circumstances were measured based on the extent to which the respondent had had to manage on a lower income, draw on savings to cover ordinary living expenses, or go deeper into debt in the previous three years (ranging from “not at all” to “a great deal”). The resulting scale (alpha = .84) ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the most difficult circumstances.

Partisanship is another potential confounder. There is evidence that Liberals are more likely than Conservatives to be very concerned about COVID-19 (Pickup et al., Reference Pickup, Stecula and van der Linden2020). Liberals may also be more open to executive aggrandizement. Partisans are apt to put partisan advantage ahead of respect for democratic norms (Graham and Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020), viewing democratic institutions instrumentally as vehicles for advancing their party's interests. If so, as partisans of the party controlling the executive, Liberals may be more open to expanding prime ministerial powers in order to advance their party's agenda and consolidate its hold on power. Partisanship is measured based on whether respondents thought of themselves as Conservative, Liberal, New Democratic Party (NDP), Green, other, or none of these. Respondents answering “none of these” are classified as non-partisans. Too few respondents (29) identified as partisans of other parties for reliable analysis, and they are therefore excluded.

People with authoritarian personalities are apt to become very anxious in the face of uncertainty and insecurity, because they have failed to develop coping strategies (Oesterreich, Reference Oesterreich2005). Consistent with this argument, authoritarianism predicted greater anxiety about terrorist attacks (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005). Authoritarians are also especially likely to look to their leaders to protect them from danger (Hetherington and Suhay, Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011). If so, they may be particularly likely to favour executive aggrandizement when faced with the threat posed by COVID-19, raising the possibility that authoritarian predispositions are a common cause of both anxiety and support for executive aggrandizement. Following Feldman and Stenner (Reference Feldman and Stenner1997), our measure of authoritarian predispositions focuses on child-rearing values. Respondents were asked which values it would be desirable to teach a child: independence or respect for elders, obedience or self-reliance, being well-behaved or curiosity. The resulting measure ranges from those who believed children should be independent, self-reliant and curious to those who thought children should be respectful, obedient and well-behaved. To conserve cases,Footnote 8 the scale was dichotomized: those choosing two or more of the authoritarian values were considered to have authoritarian predispositions (43%).

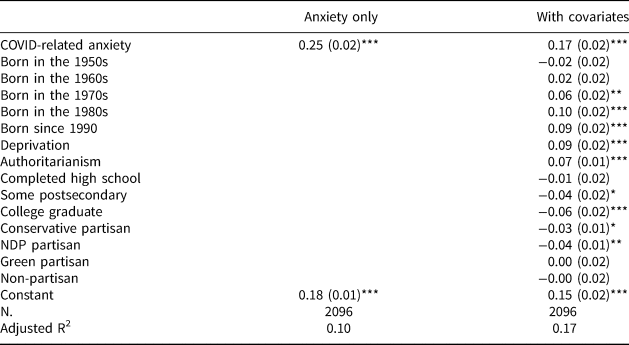

As predicted by our first hypothesis, there is a significant association between anxiety about COVID-19 and support for executive aggrandizement. In the full model, predicted support for executive aggrandizement increases by 16 points, going from .21 when someone has never experienced debilitating anxiety to .37 when people are so anxious about COVID that it often interferes with their daily activities and occupies their thoughts (see Figure 1). Given that the mean score on the executive aggrandizement scale is 0.27, this effect is substantively large. Put differently, a one-standard deviation increase in COVID-related anxiety is expected to increase support for executive aggrandizement by 0.21 standardized units. Accordingly, our first hypothesis is confirmed: COVID-19-induced anxiety is associated with greater support for executive aggrandizement.

Figure 1. Anxiety about COVID-19 and Support for Executive Aggrandizement

Note: Predicted support is based on an ordinary least squares regression model that includes birth cohort, material circumstances, education, partisanship, and authoritarianism. The support for executive aggrandizement scale ranges from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater support.

The anxiety coefficient shrinks when potential confounders are added to the model (see Table A3 in the appendix for the full results). As expected, younger cohorts are more anxious about COVID and more supportive of executive aggrandizement. Similarly, economic deprivation is associated with greater anxiety and more support for executive aggrandizement. However, education is not a confounder: people with post-secondary education are less supportive of executive aggrandizement but no less anxious than those with lower levels of education.

Authoritarian predispositions are associated with support for executive aggrandizement. This is consistent with survey evidence from Britain, Canada and the United States that people with authoritarian predispositions are more supportive of policies to fight the virus, even though those policies restrict civil liberties (Cilizoglu et al., Reference Cilizoglu, Heinrich and Kobayashi2021). Authoritarian predispositions are also associated with greater anxiety about COVID. Like New Democrats, Conservatives are significantly less likely than Liberals to favour executive aggrandizement. Conservatives are also significantly less anxious. However, even controlling for all these variables, the observed association between anxiety and support for executive aggrandizement remains substantively large.

Method Two: A vignette experiment

The vignette experiment depicts a provincial premier who wants either to continue the lockdown although infection rates are slowing down or to open up for the sake of the economy amid relatively high infection rates, but who faces opposition from the provincial legislature and needs to decide whether to shut down the legislature or not. We used the phrasing “a premier” rather than “your premier” to enhance the vignette's plausibility in provinces with majority governments and to ensure the same treatments across provinces. At the time, British Columbia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island had minority governments and Ontario had experienced a minority government only five years earlier, lending credibility to the notion that a premier could be thwarted.Footnote 9

Based on work by Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020) and Carey et al. (Reference Carey, Clayton, Helmke, Nyhan, Sanders and Stokes2022), we had expected that responses would be jointly conditional on the partisanship of the premier and the respondent's partisanship: if a premier is from another party, a partisan might be unwilling to endorse shutting down the legislature, even if they agree with the premier's policy stance. Accordingly, depending on the condition, the premier is described as being a Conservative, a Liberal, or a New Democrat, or else no party label is provided. This results in eight randomly assigned conditions.Footnote 10 There is no threat treatment as we assume that, in the midst of a pandemic, people have effectively been treated. The infection rate was not manipulated, as this would have resulted in 16 conditions. Instead, we opted for those conditions that constituted the most conservative test.

A [Conservative] [Liberal] [NDP] [empty field] premier wants to continue the lockdown. The infection rate in the province is slowing down. The provincial legislature is arguing against this step and wants to open businesses immediately to stimulate the economy. Should the premier shut down the legislature and continue the lockdown?

A [Conservative] [Liberal] [NDP] [empty field] premier wants to open businesses again to stimulate the economy. The infection rate in the province is relatively high. The provincial legislature is arguing against this step and wants to continue the lockdown for two more weeks. Should the premier shut down the legislature and open businesses?

Respondents could answer yes or no. It turns out that a premier's partisanship did not make a significant difference to the proportions responding that a premier should shut down the legislature, whether the premier was depicted as wanting to open up the economy or continue the lockdown (see Figure S1 in the supplemental online appendix) and whether or not the premier was a co-partisan (see Figure S2 in the supplemental online appendix). Accordingly, we have combined responses across the four partisanship conditions. This enables us to focus on the effect of the key treatment with respect to our second hypothesis: whether the premier wants to open businesses again to stimulate the economy, despite relatively high infection rates, or prefers to continue the lockdown although infection rates are slowing.

In line with our first hypothesis, anxiety is associated with a greater likelihood of agreeing that a premier should shut down the legislature if it is thwarting the premier's proposed way of dealing with the pandemic (see Figure 2). Even controlling for potential confounders, the predicted probability of agreeing with shutting down the legislature increases significantly from .33 for those who never experienced debilitating anxiety to .50 for those who were so anxious about COVID-19 that they were often unable to think about anything else or carry out their daily activities.Footnote 11 Notably, this effect holds whether or not respondents agreed with a premier's lockdown stance, though policy congruence has a stronger independent effect than does anxiety (see Table A4).

Figure 2. COVID-related Anxiety and Support for Shutting Down the Legislature

Note: Predicted support is based on an ordinary least squares regression model that includes birth cohort, material circumstances, education, partisanship, authoritarianism, and congruence between a premier's policy and the respondent's lockdown preference.

According to our second hypothesis, some people will be willing to ignore the need for checks on the power of the executive for the sake of their preferred lockdown policy. Respondents’ preferences were tapped based on which COVID-19 policy they preferred: ending lockdowns immediately, continuing lockdowns until there are fewer COVID-19 deaths or continuing lockdowns until a COVID-19 vaccine is found. Eleven per cent wanted the lockdown ended at once, 20 per cent would wait for a vaccine and 69 per cent preferred waiting until there were fewer deaths. Validating our assumption that some people would favour opening up the economy to mitigate the dire economic consequences of the lockdowns, 51 per cent of those who were more worried about the economic fallout than about the health risks wanted the lockdown ended now, compared with 4 per cent of those who were more concerned about the health implications and 9 per cent of those who were worried on both counts.

As predicted, many Canadians’ lockdown preferences seemingly mattered more than respecting democratic norms (see Figure 3). Looking at respondents who shared a premier's preference for maintaining the lockdown,Footnote 12 fully 86 per cent of those who wanted the lockdown to continue until a vaccine was found were willing to condone the removal of legislative checks on the premier if that meant that the lockdown would remain in place, and so were 54 per cent of those who wanted to wait until there were fewer deaths. Similarly, when the legislature was described as opposing the premier's plan to open businesses again in order to stimulate the economy, 64 per cent of respondents who wanted the lockdown ended now condoned shutting down the legislature.Footnote 13 Accordingly, our second hypothesis is confirmed: people are apparently willing to sacrifice legislative checks for the sake of their preferred lockdown policy.

Figure 3. Support for Shutting Down the Legislature by Premier's Lockdown Policy and Respondents' Lockdown Preference

Note: The bars represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

However, there is no support for the expectation that the willingness to sacrifice democratic norms for the sake of the preferred lockdown policy would increase as anxiety about COVID increased (H2a). When we added an interaction between COVID-related anxiety and congruence with the premier's lockdown policy to the model estimated in Table A4, there was nothing to suggest that anxiety moderated the effect of policy congruence (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Support for Shutting Down the Legislature by COVID-related Anxiety and Congruence with Premier's Lockdown Policy

Note: Predicted agreement is based on an ordinary least squares regression model that includes birth cohort, material circumstances, education, partisanship, authoritarianism, and an interaction between COVID-related anxiety and congruence with the premier's lockdown policy (see Table A4).

In sum, the vignette experiment lends support to both our main hypotheses: the more anxious people are about COVID-19, the more willing they are to dispense with legislative checks on the executive (H1), and people's desire for protective policies outweighs any concern for constraining the power of the executive (H2). However, contrary to H2a, the effects of anxiety and policy congruence are independent of one another.

Method Three: The candidate-choice experiment

Our candidate-choice conjoint experiment is particularly appropriate for evaluating respondents’ willingness to sacrifice checks on the executive for the sake of their preferred lockdown policy, because it allows for an assessment of the weight that people assign to different candidate attributes (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, Yamamoto, Druckman and Greene2019; Incerti, Reference Incerti2020). This design also reduces the risk of social desirability bias, since potentially sensitive candidate attributes can be included along with more neutral attributes, such as age and prior experience. Finally, the conjoint design approximates a real-world decision context (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015).Footnote 14

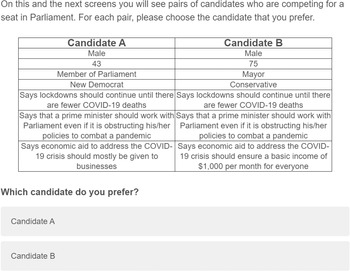

Respondents were told that they would see a series of screens displaying the profiles of pairs of candidates competing for a seat in Parliament. They were asked to select their preferred candidate in each pair. The candidate profiles included age, sex, political experience, party label, position on economic aid, position on the lockdown, and one attribute relating to executive aggrandizement (see Table A5 in the appendix for the complete list of attribute values, and see Figure A1 for an example of a profile table). Lockdown positions ranged from “lockdowns should be ended immediately” to “lockdowns should continue until a COVID-19 vaccine is found.” There were two randomly assigned versions of the executive aggrandizement attribute, one dealing with weakening legislative checks and the other with weakening judicial checks. For one random half sample, the candidates were described as saying either that “A prime minister should work with Parliament even if it is obstructing his/her proposals to combat the pandemic” or “A prime minister should shut down Parliament if it is obstructing his/her proposals to combat the pandemic.” For the other random half sample, the candidates were portrayed as stating either that “A prime minister should comply with court decisions overturning his/her policies to combat a pandemic” or “A prime minister should ignore court decisions overturning his/her policies to combat a pandemic.” For both versions, advocating checks on prime ministerial power serves as our baseline. These manipulations are plausible. For example, former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper prorogued Parliament to forestall a vote of non-confidence and to shut down committee hearings regarding the treatment of Afghan detainees. More recently, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau used prorogation to put an end to the finance and ethics committee probes into the WE Charity scandal. Similarly, the disregard of judicial checks is plausible in light of Trudeau's attempts to pressure the justice minister (who also serves as Canada's attorney general) to intervene in the ongoing prosecution of a large corporation.

Respondents were presented with six randomly generated profile tables.Footnote 15 Having respondents choose between multiple pairs of candidates makes for much more precise estimates of the quantities of interest. This introduces the risk of survey satisficing (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2018) and carryover effects (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). However, task-specific estimates of the effects of candidates’ attributes are quite consistent across tasksFootnote 16 (see Figure A2 in the appendix), meaning that we can safely leverage the benefits of the multi-task design by collapsing results across tasks. Instances where a respondent spent less than five seconds on a task have been dropped.Footnote 17 The analyses are based on 25,426 hypothetical candidates.

The levels of the attributes were fully randomized across both respondents and profile tables. Mimicking a typical candidate profile, age, sex, political experience and party label always appeared first, but the order of the policy positions and the attribute relating to executive aggrandizement was randomized across respondents. To avoid cognitive overload, the ordering of the attributes was fixed across the six tables for each respondent. Regardless of the order in which the candidates and the attributes appeared, the results are quite similar (see Figures A3 and A4 in the appendix). After viewing each pair of profiles, respondents were instructed to select their preferred candidate. A forced-choice format was preferred to ratings of each candidate because it made the potential trade-offs more explicit (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, Yamamoto, Druckman and Greene2019). Respondents’ choices between candidates serve as our outcome variable.

We begin with the overall results (see Figures S4a and S4b in the supplemental online appendix for the full results). To facilitate interpretation, we plot the average marginal component effects (AMCEs). These represent the estimated effect of a given attribute relative to the baseline value of that attribute, averaged over other candidate attributes (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). The AMCE plots show how much the probability of choosing a candidate with a given attribute increases or decreases, relative to the baseline for that attribute. For example, we can state that the average estimated probability of choosing a candidate is X points lower when the candidate says that a prime minister should ignore court decisions overturning his/her policies to combat a pandemic. Here, the baseline would be the candidate saying that a prime minister should comply with court decisions. Overall, 43 per cent of respondents in the Parliament condition and 44 per cent in the courts condition preferred a candidate who ignored democratic norms to one who respected those norms.

Figure 5a focuses on the weakening of legislative checks on prime ministerial power. It shows that candidates who endorse executive aggrandizement suffer only a modest penalty. The estimated probability of choosing a candidate is only seven points lower when a candidate believes that a prime minister should shut down Parliament if it is obstructing the prime minister's proposals to combat a pandemic as opposed to working with Parliament even if it is being obstructive. The punishment is very similar (six points) in the case of a candidate who states that a prime minister should disregard court decisions overturning the prime minister's policies to combat a pandemic (see Figure 5b).

Figure 5a. Estimated AMCEs (Legislative Checks)

Figure 5b. Estimated AMCEs (Judicial Checks)

Figure 6 provides an additional test of our first hypothesis. It breaks down the AMCEs according to how anxious respondents felt about COVID-19. We created four levels based on whether respondents reported “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely” or “never” feeling so anxious that they could think of nothing else or so anxious that their anxiety interfered with daily activities.Footnote 18 The results for legislative checks confirm that the more anxious people feel about COVID-19, the less likely they are to penalize a candidate who would flout democratic norms. However, anxiety does not make a difference when it comes to dispensing with judicial checks.

Figure 6. Estimated AMCEs by COVID-related Anxiety

Candidates’ policy stances clearly have a much stronger independent effect on people's choice of candidate than whether or not the candidate endorses executive aggrandizement (see Figures 5a and 5b). In the Parliament condition, the estimated probability of choosing a candidate is 18 points higher if the candidate wants to continue the lockdown until a vaccine is found and 28 points higher if the candidate would wait until there are fewer deaths, compared with a candidate who would end the lockdown right away. The figures are very similar in the courts condition, with the estimated probability of selecting a candidate who would continue the lockdown being 26 points and 17 points higher, respectively.

However, the AMCE plots cannot tell us how people choose when faced with a trade-off between a candidate's respect for democratic norms and a candidate's policy positions. This trade-off is key to our second hypothesis, which predicts that people will sacrifice restraints on the power of the executive for the sake of their preferred lockdown policy. To test this hypothesis, we focus on tasks that required respondents to choose between a candidate who respected the need for legislative or judicial checks and one who showed a disregard for restraints on prime ministerial power. To assess respondents’ willingness to sacrifice checks on the executive when their preferred lockdown policy is at stake, we compare the proportion choosing the undemocratic candidate when only the democratic candidate shares the respondent's lockdown preference and when only the undemocratic candidate has the same preference. If respondents’ preferred lockdown policy trumps concern for executive aggrandizement, respondents should be most likely to choose the undemocratic candidate when that candidate is the only one of the two to share their preference and least likely to choose such a candidate when only the democratic candidate favours their preferred policy. By way of comparison, we also include tasks where respondents did not have to choose between their preferred policy and respecting democratic norms, because neither candidate or both candidates shared the respondent's position. We exclude tasks pitting a candidate who said that lockdowns should continue until deaths decline against a candidate who wanted the lockdown to continue until a vaccine is available, since both positions involve keeping the lockdowns in place.

The results are striking (see Figure 7a). Respondents were clearly ready to sacrifice restraints on prime ministerial power for the sake of their preferred lockdown policy. When both candidates share the respondent's position on lockdowns, the candidate who endorses shutting down Parliament receives 40 per cent of the vote compared with 60 per cent for the candidate who respects the need for legislative checks. The figures are very similar when neither candidate shares the respondent's policy preference, with 43 per cent choosing the candidate who would shut down Parliament. By contrast, fully 76 per cent of respondents chose the candidate who favoured shutting down Parliament when that candidate was the only one of the two to share their preference regarding the lockdown. Meanwhile, only 15 per cent would prefer a candidate who flouted democratic norms if the other candidate respected the need for legislative checks and favoured their preferred policy.

Figure 7a. Support for Executive Aggrandizement by Policy Congruence (Legislative Checks)

Note: The points indicate the proportion selecting a candidate who would ignore the need for legislative checks over a candidate who would respect the need. The bars indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

The results for the court condition are equally supportive of our second hypothesis (see Figure 7b). Indeed, the numbers are very similar. Once again, lockdown preferences decisively trump concern for democratic norms. Seventy-five per cent of respondents disregarded the need for judicial restraints on a prime minister if the candidate who would ignore unfavourable court decisions was the only one of the two to advocate their preferred position on the lockdown. The figure drops to 16 per cent when the candidate who respects the need for judicial checks is the only one to share the respondent's position on the lockdown.

Figure 7b. Support for Executive Aggrandizement by Policy Congruence (Judicial Checks)

Note: The points indicate the proportion selecting a candidate who would ignore the need for legislative checks over a candidate who would respect the need. The bars indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

There is mixed support for the notion that anxiety moderates the willingness to ignore the need for checks on prime ministerial power (H2a). When we break down the results by level of anxiety, there is no evidence of this for legislative checks (see Figure 8a). However, people who often experienced debilitating anxiety about COVID-19 were significantly more likely than those who never experienced such anxiety to disregard the need for judicial checks if only the undemocratic candidate shared their lockdown preference (see Figure 8b).

Figure 8a. Support for Executive Aggrandizement by Policy Congruence and COVID-related Anxiety (Legislative Checks)

Figure 8b. Support for Executive Aggrandizement by Policy Congruence and COVID-related Anxiety (Judicial Checks)

In sum, the results of the conjoint experiment offer strong support for our second hypothesis: people are willing to sacrifice checks on the power of the executive for the sake of their preferred stance on the lockdown. However, only in the case of judicial checks is this moderated by anxiety about COVID-19. At the same time, with the exception of dispensing with judicial checks, we find relatively strong support for our first hypothesis that anxiety about COVID-19 would be associated with a greater willingness to condone executive aggrandizement.

Concluding Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic offered an opportunity to assess the extent to which Canadians can be considered reliable defenders of democracy. Our study has the advantage of going beyond measures of support for democracy in the abstract. It suggests that faced with threats to their lives and livelihoods, substantial numbers of Canadians may be ready to condone executive aggrandizement. Canadians register high scores (8.4 on a 0-to-10 scale) when asked about the importance of living in a country that is governed democratically, and yet 10 per cent of respondents scored above the midpoint on our executive aggrandizement scale: 39 per cent agreed that a premier should shut down the provincial legislature if it was thwarting a premier's proposal to open up or continue the lockdown, and 43 per cent of respondents in the Parliament condition and 44 per cent in the courts condition chose the candidate who disregarded democratic norms over a candidate who respected those norms. Whether Canadians would be as ready to condone executive aggrandizement should it actually occur is an open question, but our analysis certainly points to the possibility. Future research will have to determine whether this willingness to condone executive aggrandizement will persist once the COVID-19 crisis is over. However, our findings suggest that, especially in the face of a crisis, support for democracy may not run as deep as conventional survey questions about democracy in the abstract seem to indicate.

Drawing on terror management theory and work on threat, we identified two ways that people may cope with an existential threat like the COVID-19 pandemic. The first involves looking to leaders for decisive action to protect them from the threat. Accordingly, we predicted that the more anxious people felt about COVID-19, the more likely they would be to condone executive aggrandizement. As predicted, respondents whose reported levels of COVID-related anxiety interfered with their daily lives and consumed their thoughts had significantly higher scores on our measure of executive aggrandizement than respondents who reported never experiencing such anxiety. They were also more likely to agree with a premier shutting down the provincial legislature and to choose a candidate who would disregard legislative checks (but not judicial checks) on prime ministerial power.

The second way that people may cope with existential threats is to look to protective policies. This led us to predict that people would be willing to sacrifice democratic norms for the sake of protective policies. The vignette experiment provided strong support for this argument: many respondents’ desire to continue or to end the lockdown outweighed any concern for legislative checks on a premier's power. The candidate-choice experiment provided even stronger support for this argument. When faced with choosing between a candidate who shared their preferred position on the lockdown and a candidate who believed otherwise, substantial majorities were willing to forgo both legislative checks and judicial checks in favour of the candidate who shared their preference. In the case of judicial checks, this willingness was enhanced when someone had often experienced debilitating anxiety about COVID-19. Still, we cannot rule out the possibility that people might be willing to trade off democratic norms for the sake of any salient policy. Future research should investigate whether this is indeed the case.Footnote 19

In addition to providing insight into Canadians’ willingness to condone executive aggrandizement in the midst of a global pandemic, our study highlights the value of combining insights from terror management theory and the threat literature. The core insight from terror management theory relates to the importance of mortality salience and the resulting existential anxiety in fuelling a desire for decisive leadership. Merolla and Zechmeister's (Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009) work on threat adds two key elements: the role of collective crises in eliciting profound anxiety and the recognition that threats to people's financial and psychological welfare can motivate the same need for coping mechanisms as threats to their physical security. The threat literature also highlights people's tendency to deal with threats by looking to protective policies. Our study has provided empirical support for both coping mechanisms and does so in the face of an actual threat to lives and livelihoods.

Studying responses to a collective crisis in the midst of a pandemic necessarily limits our ability to make causal claims, since we were unable to manipulate the degree of threat. In effect, our respondents had all been treated to varying degrees. Moreover, without a pre-COVID measure of trait anxiety, we could not disentangle the extent to which anxiety was elicited by the pandemic, as opposed to being a stable personality trait.

Future studies need to investigate how willing Canadians are to tolerate the erosion of other democratic norms, especially relating to restricting voting rights and limiting civil liberties. The latter may be particularly important in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Pickup et al., Reference Pickup, Stecula and van der Linden2020; Rheault and Musulan, Reference Rheault and Musulan2021). The need to sacrifice some personal freedoms for the sake of public health may not be inherently undemocratic, but there is the risk of discriminatory or abusive enforcement (Kolvani et al., Reference Kolvani, Pillai, Edgell, Grahn, Kaiser, Lachapelle and Lührmann2020). How willing might Canadians be to overlook such behaviour when a disliked group is targeted? This type of question can most appropriately be answered by combining observational and experimental research, as we did here.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada under its Insight program. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Table A1. Sample Descriptives

Table A2. Summary Statistics

Table A3. Anxiety and Support for Executive Aggrandizement

Table A4. COVID-related Anxiety and Support for Premier Shutting Down the Legislature

Table A5. List of Attributes

Figure A1. Example of a Candidate Profile Table

Figure A2a. Consistency of AMCEs across Tasks: Shutting down Parliament

Figure A2b. Consistency of AMCEs across Tasks: Ignoring Court Decisions

Figure A3a. Profile-order Effects: Shutting down Parliament

Figure A3b. Profile-order Effects: Ignoring Court Decisions

Figure A4a. Row-specific AMCEs: Shutting down Parliament

Figure A4b. Row-specific AMCEs: Ignoring Court Decision