Introduction

Participant recruitment and retention (R&R) represent well-known challenges in human subjects research (HSR) [Reference Nicholson, Schwirian and Klein1], especially with studies involving young children, long-term follow-up, burdensome assessments, and/or interventions or procedures with some level of risk. Inadequate R&R can threaten the integrity of research and its findings [Reference Desai2]. Lack of access to affordable, reliable transportation, childcare, overnight lodging, or meals are some of the common logistical issues surrounding study activities and can pose major barriers to research participation. The differences in needs and perceived barriers versus motivators can be subtle yet important between different communities. Researchers can reduce burden and foster positive experiences for participants by proactively addressing potential barriers in advance of a study, and by practicing procedures to systematically assess and meet evolving, often unanticipated needs of the study participants.

Transportation-related challenges may make it impossible for some individuals to engage in research requiring in-person visits [Reference Graham, Ngwa and Ntekim3]. Improved access to public transportation, especially taxi or rideshare services, could help boost recruitment [Reference Gibaldi, Whitham, Kopil and Hastings4]. Residential proximity to the research site and reliable public transportation can increase willingness of individuals to participate in research [Reference Rigatti, DeGurian and Albert5]. Unfortunately, 45% of Americans do not have access to public transport [6]. For rural residents, limited public transportation and concerns about parking are major barriers to participation [Reference Caston, Williams and Wan7]. Even if participants have transportation, they may have to cover the related costs upfront, and then receive reimbursement later, posing challenges, especially for participants with lower socioeconomic status (SES). These issues can be further compounded if car seats are required for child transportation.

Lack of available or affordable childcare is another major barrier. Securing childcare has been reported as “extremely difficult” by participants [Reference Robiner, Yozwiak, Bearman, Strand and Strasburg8–Reference Hilliard, Goldstein, Nervik, Croes, Ossorio and Zgierska11], and identified as one of the most important facilitators for research participation among pregnant and breastfeeding persons [Reference Lemas, Wright and Flood-Grady12]. Participants with less-flexible work schedules may require childcare to enable their participation [Reference Fassinger and Morrow13]. Yet, many families are unable to afford childcare, and/or the availability of childcare can be limited, especially in rural areas [Reference LeCroy, Potter and Bandeen-Roche14]. Although some research groups can provide onsite childcare, many sites do not have access to a pool of volunteers (e.g., undergraduate or graduate students) or a child-friendly space.

Lack of affordable lodging near the research site can be an insurmountable barrier to research participation when overnight accommodations are needed, e.g., due to participant extended travel time to the research site, the duration or timing of the study visits, or participant safety concerns. As with other barriers, this can especially impact those with low SES and rural residents. Freidman et al. (2015) noted that perceived recruitment barriers, motivators, and strategies were contextually similar between rural and urban sites; however, the perception of the importance of certain factors varied, with rural participants paying more attention to the study-related time commitment and benefits to the entire family [Reference Friedman, Foster, Bergeron, Tanner and Kim15]; strategies increasing the perception that study participation is “worth their time” and emphasizing family aspects may help boost research engagement in rural areas.

Participant access to food, whether snacks or larger meals, increases participant satisfaction with research and the likelihood they will complete the study [Reference Nicholson, Schwirian and Klein1,Reference Goldstein, Bakhireva and Nervik16,Reference Wong, Song and Jiao17]. Providing food and drinks, especially during longer study visits, ensures participants are not distracted by hunger or thirst. This acknowledgment of participants’ biological needs is particularly important for studies involving pregnant, lactating, or child participants. Shared meal times by offering a less formal social environment and a positive atmosphere can be an opportunity to enhance trust and rapport between research team and participants [Reference Dunbar18].

The intersectionality of participant needs and logistical barriers to research participation has been well-documented, and addressing these challenges can enhance representative population sampling, which is critical for robust conclusions to be drawn from any research. Persistently low enrollment rates are common in research, causing extended enrollment periods and delays in research completion [Reference Huang, Bull, Johnston McKee, Mahon, Harper and Roberts19]. Even with a representative sample enrolled at baseline, external validity can be challenged in longitudinal research by attrition, which is anticipated to be higher among participants from disadvantaged social backgrounds, minority groups, or who are pregnant, younger, low-income, less educated, in unstable marital partnerships, have mental illness, or use substances [Reference Beasley, Ciciolla and Jespersen9,Reference Goldstein, Bakhireva and Nervik16]. Groups historically underrepresented in research include racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender and other minority groups; geographically isolated groups (e.g., rural populations or residential racial segregation); vulnerable populations, including the elderly, pregnant people, children, individuals with disabilities, limited English proficiency [20], and fewer economic resources. These groups have been impacted by negative historical factors and social determinants of health known to increase health inequities and reduce research participation [Reference LeCroy, Potter and Bandeen-Roche14]. Previous studies have found that family and work obligations and stressful life events are more frequently experienced by marginalized and underrepresented groups, limiting their capacity to engage in research despite their desire to do so, and requiring research/researcher flexibility and support [Reference Nicholson, Schwirian and Klein1,Reference Otado, Kwagyan, Edwards, Ukaegbu, Rockcliffe and Osafo21]. In addition, our understanding of how to best meet the needs of gender and sexual minority groups and effectively engage them in research is still evolving. Employing participant-centered, culturally sensitive practices that foster trust between researchers and participants, and anticipating and overcoming logistical burdens can improve research engagement, particularly among populations historically underrepresented in research [Reference Beasley, Ciciolla and Jespersen9,Reference Goldstein, Bakhireva and Nervik16,Reference Morton, Grant and Carr22,Reference Chasan-Taber, Fortner, Hastings and Markenson23].

This is of particular concern for the NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-term® (HEAL) HEALthy Brain and Child Development (HBCD) study [Reference Friedman, Foster, Bergeron, Tanner and Kim15], which focuses on young children whose parents may need to bring their other children to the study visits, especially since the HBCD’s assessments can be long and its brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is best acquired during a child’s evening/nighttime sleep when childcare support volunteers are harder to recruit.

The HEAL HBCD long-term birth cohort study, focused on inclusion of vulnerable populations, may be particularly affected by these considerations [24]. The HBCD study plans to engage a diverse population of 7,500 parent (or guardians or other caregivers) - child dyads, starting with pregnant people who are representative of the US population, to better understand child development from pregnancy through early childhood. The design of the HBCD study combines longitudinal assessments of brain (using the MRI and electroencephalogram), cognitive and behavioral development, biospecimens, contextualized by in-depth characterization of the pre- and post-natal environments through the first decade of child’s life. The study protocol includes several study visits (both remote and in-person) that span from several hours to multiple days, bringing to light questions about best practices for equitable research engagement of participants from diverse populations. Given its national scope, it is critical for the HBCD study to understand factors that may negatively impact R&R, so that it can positively and effectively engage participants, including those from historically underrepresented and marginalized groups.

With this in mind, and with a dearth of evidence to inform practical solutions for improving R&R of participants in longitudinal research, we developed a study-specific survey and surveyed the research sites participating in the HBCD consortium prior to study launch to learn about their local strategies and plans for meeting participants’ needs related to transportation, lodging, childcare, and meals. This manuscript presents this survey’s findings on the current landscape of these support strategies, followed by recommendations for overcoming logistical barriers and supporting families and children across the HBCD consortium as the essential first step toward developing equitable and adaptable best practices.

Materials and methods

Design

The survey was an outcome of the discussions held with members from the NIH HEAL HBCD study [Reference Friedman, Foster, Bergeron, Tanner and Kim15] sites and workgroups. Site members discussed how they planned to support participants’ transportation, childcare, lodging, and meal/snack needs during study visits. This project did not meet criteria for HSR and did not require review by the Institutional Review Board.

Survey design

The survey was developed by investigators from the HBCD study’s Rural and Sovereign Communities Workgroup, with input from the members of the consortium-wide R&R; Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; Ethics, Legal, and Policy; and Study Navigators Workgroups. This non-validated survey was tailored to the HBCD study needs and administered in the planning phase of HBCD, prior to participant enrollment, and designed to capture the spectrum of planned strategies related to participant transportation, childcare, lodging, and meal/snack support needs, so that the survey-yielded data could serve as a platform for developing guidance for all sites regarding best practices for strategies to address participant needs during research activities. Most questions offered multi-choice responses and options for qualitative comments to describe individual site’s plans not captured by the closed-ended response choices. The final survey (see Appendix 1) included 20 questions, querying sites about their location, strategies and barriers regarding transportation, childcare, lodging, and meals/snacks, and one open-ended question: “Anything else you would like to share about transportation, lodging, childcare or meal related considerations or issues?”

Procedures

A link to the Qualtrics survey (Qualtrics, Version October 2022, Provo, UT) was sent by the consortium’s Administrative Core to all sites’ Principal Investigators and completed between 10/08/2022 through 11/15/2022. The survey collected information identifying the site, but not information about the person who completed the survey on the site’s behalf. Although the HBCD study includes 25 sites, some sites include more than one location, resulting in 28 consortium recruitment locations (i.e., potential respondents).

Analytical approach

Frequencies of responses were calculated across survey respondents using Microsoft Office 2019 Excel program, with the total sample of completed surveys serving as the denominator for all percentage calculations. Qualitative responses were reviewed by the authors to determine the extent to which they provided additional contextual information and were grouped into general themes. The overall number, length, and type of the qualitative comments did not meet the standards for formal qualitative thematic analytic procedures [Reference OʼBrien, Harris, Beckman, Reed and Cook25]. The results were categorized by participant need type (e.g., transportation, childcare, etc.).

Results

All 25 funded institutions, representing 28 recruitment locations completed the survey; therefore, n = 28 was used as a denominator to calculate the frequencies of specific responses. Among the survey respondents, 100% answered the multiple-choice survey questions, and 25% (7 respondents) provided responses to the open-ended question.

Transportation

The sites reported various approaches for supporting participant transportation to and from study appointments. Most respondents (25 [89.3%]) planned to arrange for taxi, transportation service, or rideshare programs (e.g., ZipCar, Uber, Lyft). Sixteen respondents (57.1%) reported no barriers to these services, six (21.4%) did not or could not arrange for such services, and six (21.4%) qualitatively described rideshares as being unreliable in their area, unavailable outside of city limits, or limited by institutional policies.

Paying upfront for transportation, without any cost to the participant, was the dominant approach (24 [85.7%]). In addition, 16 respondents (57.1%) planned to reimburse participants based on the mileage driven to/from the study site, and six (21.4%) planned to reimburse participants after they covered travel-related expenses. Thirteen respondents (46.4%) also planned on supporting transportation for all participants, while 14 respondents considered specific criteria for offering transportation, by participant request (14 [50.0%]), if the participant lives over one hour away (7 [25.0%]), or if the study visit spanned two days (4 [14.3%]). Eleven respondents (39.3%) added qualitative responses about offering rideshares, participant reimbursement through gas cards or paying for onsite parking, or research staff driving participants to the study site or meeting participants at the participant-selected locations.

In the event a participant did not have a required car seat for child transportation, 12 respondents (42.9%) planned to provide one, and 10 (35.7%) planned to make them available through the arranged transportation service. Nine (32.1%) also marked having “other plans,” such as getting car seats from local community organizations or providing study-owned car seats for vehicles used to transport participants (e.g., Uber Medical; institutional fleet). Seven respondents (25.0%) reported not having plans for car seats yet. Eighteen respondents (64.3%) wished to have rear-facing, 17 respondents wished to have forward-facing (60.7%) car seats available, and 14 (50.0%) planned to have booster seats in the future.

Fourteen respondents (50.0%) had plans for research personnel or approved volunteers to travel to meet participants in the community for study-related activities, while 4 respondents (14.3%) planned to do this “in general, but not right now,” and 9 (32.1%) did not plan to do it.

When asked about the liability and personal injury coverage when driving participants or driving to meet participants, 16 respondents (57.1%) did not respond, and nine (32.1%) did not know if their institution provided such coverage.

Childcare

One respondent (3.6%) did not plan to provide childcare for siblings/children accompanying participants during the visits. Twenty-seven respondents (96.4%) planned to provide childcare, using designated study staff (22 [78.6%]) and/or trained volunteers (21 [75.0%]) onsite, and/or making provisions for “ecological support” (i.e., space for the parent/caregiver to care for their child/children). The majority (16 [57.1%]) planned to offer childcare support whenever requested.

Only three respondents (10.7%) stated their institution has a policy guiding childcare for research participation; 12 respondents (42.9%) answered “No,” and 11 respondents (39.3%) answered “I donʼt know” regarding such policies.

Lodging

Six respondents (21.4%) did not plan to offer participants overnight lodging. Most (17 [ 60.7%]) planned to offer lodging near the site, with five respondents (17.9%) still working on a specific plan. When asked about their criteria for offering overnight lodging for in-person visits, 11 respondents (39.3%) did not answer this question. The remaining respondents planned to offer lodging if the visit ended late at night (17 [60.7%]), if there were concerns about participant safety when returning home late (13 [46.4%]), if the assessments spanned two consecutive days (9 [32.1%]), or if the participant lived over an hour away (9 [32.1%]). Notably, only one respondent (3.6%) planned to offer lodging to all participants, regardless of circumstance.

Meals/snacks

The respondents endorsed varied plans for feeding participants and/or parents/caregivers during the study visits. Twenty-six (92.9%) planned to offer shelf-stable snacks/drinks; 18 (64.3%) planned to offer baby foods, including rice cereal; and 15 (53.6%) planned to offer bottles and formula. Fourteen respondents (50.0%) also planned to provide vouchers for participants to purchase food at a local restaurant, with 11 respondents having a list of selected restaurants for participants to choose from, and 3 respondents not having the details established yet. Twenty-two respondents (78.6%) planned to offer snacks/meals to all, at every in-person visit.

Other

Three respondents commented in response to: “Anything else you would like to share…?,” noting the survey helped them identify issues and areas they had not previously considered, and that it would be useful to receive specific guidance and funding/financial assistance to help overcome these types of logistical barriers.

Discussion

Findings from this cross-sectional survey of members from 28 unique data collection locations (across 25 awarded research sites) of the HBCD consortium conducting a large-scale, long-term birth cohort study across the U.S. [24] highlight critical considerations and plans for addressing logistical barriers related to R&R, including transportation, childcare, lodging, and meals for research participants. Plans for addressing participant needs varied across the locations, despite an otherwise standardized, common study protocol. Responses also emphasized that institutional policies are often inadequate (or missing), thus insufficient for effectively guiding these aspects of HSR that are critical for recruitment and retention, which, in turn, are essential for the validity and generalizability of research findings. Notably, the sites involved in the HBCD study largely comprise experienced research teams from academic institutions with a long history of HSR. Yet, even these teams continue to grapple with logistical barriers, highlighting an urgent need for developing guidance on these issues to ensure equitable support for research participants across diverse study settings and populations.

The limited evidence and recommendations on how to conceptualize these “mundane” aspects of research, combined with sparse or non-existent institutional policies, place a burden on individual research teams to create detailed participant support protocols, while also navigating legal and regulatory concerns. These concerns are particularly relevant to research-related transportation and childcare considerations. Providing safe transportation and childcare requires advanced planning, secure facilities, and an adequate number of sufficiently trained and approved staff or volunteers. Yet, although most institutions enforce child protection training and safety guidelines for campus-based youth programs, many do not carry these policies further or provide guidelines specific to research projects involving children and families. Similar challenges relate to transportation, when an institution may guide their faculty/staff driving in general terms (in personal, institutional fleet, or externally rented vehicles) but not in relation to research participant transportation and relevant legal/financial aspects.

Our survey findings indicated substantial heterogeneity in approaches across the study recruitment locations, and a scarcity of policies and published guidelines related to the “logistical barriers.” Yet, overcoming barriers to research participation involves addressing both the logistical barriers and tangible resources (including transportation, childcare, lodging, and meals) and intangible ones. Ongoing engagement with participants, their families, and communities is critical toward understanding and accommodating their needs, building trust and rapport, and creating a more equitable participant experience. Integrating input from patients (“peers”) and other stakeholders into study protocols can positively change these historically harmful power dynamics; patient stakeholders become research partners, acknowledged as subject matter experts of their own needs, and work together with researchers to develop effective solutions addressing logistical barriers [Reference Hards, Cameron, Sullivan and Kornelsen26,Reference Montgomery, Kelly and Campbell27]. This is key in building an atmosphere, in which participants feel valued, heard, and able to honestly and timely voice emergent needs. Involving “peers” (e.g., recovery peer specialists in a substance use-related research) can boost research engagement among hard-to-reach, vulnerable populations [Reference Zgierska, Hilliard, Deegan, Turnquist and Goldstein28]. Hiring research personnel who speak the same language as the potential study participants (i.e., “bilingual staff”), are trained in cultural competency and conditions under the investigation, and avoid stigmatizing language can also improve recruitment rates, more than focusing on hiring ethnically matched study personnel [Reference Woodall, Morgan, Sloan and Howard29]. It is important to understand that different study sites will (and should have) different engagement plans, which reflect participant needs at each site. Even within a site, plans to increase equity and retain diverse participants should be multifaceted, offering a range of supports to meet varying needs of individuals, communities, and research teams. Working with stakeholder partners can help research teams identify both local barriers and solutions optimally suited for their local contexts to support participation in research of diverse groups.

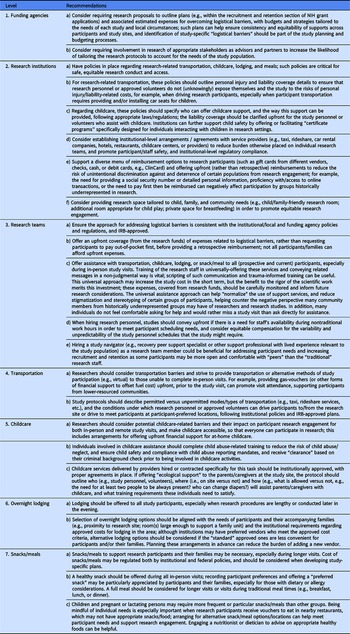

The success of the HBCD study and similar HSR with in-person assessments will hinge on consistent, honest, long-term participation from diverse families who volunteer to commit to a major investment of their time and effort. It is the responsibility of research teams, as those with the funding resources, to support equitable research participation in order to conduct impactful, robust investigations. Therefore, we propose a set of recommendations for the HBCD consortium regarding transportation, childcare, lodging, and meals to support research participants based on the existing literature and experience of researchers involved in the HBCD study (Table 1). Although we focused on these specific areas, they do not exhaust a list of potential logistical barriers to research that participants may face (e.g., language or mobility-related barriers). It is important for research teams to consider specific needs of the study population during the planning phase of each project and adequately budget for overcoming the identified barriers. Future surveys of the HBCD sites about their approach to addressing logistical barriers, along with the evaluation of actual R&R outcomes across the sites, will provide data to better discern if our recommendations and site-applied specific strategies can increase engagement of participants across diverse populations, including those historically underrepresented in research. What follows are the HBCD study team recommendations regarding the provision of transportation, childcare, lodging, and meals as a means of equitably supporting participant study engagement.

Table 1. Recommendations for minimizing the impact of transportation, childcare, lodging, and meals as “logistical barriers” to participant research engagement

Conclusions

Funding agencies and research institutions can facilitate engagement of diverse participants in HSR by aligning their funding supports and policies to overcome common logistical barriers and support R&R and equity in research participation. Researchers must take a multifaceted approach to R&R to ensure that study activities are appealing, accessible, and conducted within a welcoming, inclusive environment for all participants. The strategies and their impact on R&R should be continually evaluated to inform result validity, generalizability, interpretation, and future approaches. The scientific imperative to ensure that study participants are representative of the larger community is dependent on addressing barriers, which have led to historical underrepresentation of some groups in research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2024.4.

Acknowledgments

Data and Concepts used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the HBCD Study (https://hbcdstudy.org/), a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit approximately 7,500 families and followed them from pregnancy to early childhood. The HBCD Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners. A full list of supporters is available at https://hbcdstudy.org/about/federalpartners/. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://hbcdstudy.org/study-sites/. HBCD Consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and provided data, with the members of the Rural and Sovereign Communities; Recruitment and Retention; Diversity, Equity and Inclusion; Legal, Ethics, and Policy; Study Navigator Workgroups; and the Administrative Core particularly contributing to this manuscript. Dr Traci M. Murray substantially contributed to the interpretation of the data and participated in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript, consistent with her role as the Scientific Advisor for JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) for the HBCD Consortium study.

Author contributions

The authors contributed to the manuscript’s conception and design of the work (AEZ, DSD, LGY, BH, HH, FH, JMC, the HBCD Consortium); data collection (all authors); data analysis (AEZ, TG, NP, BS, JC); result interpretation (all authors); drafting of the manuscript (AEZ, TG, NP, DSD, TMM, LGY, BH, BS, JC, AA, HH, FH, JMC); and editing and final approval of the manuscript (all authors). AEZ takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Funding statement

This work was funded by the National Institutes of HEAL HBCD initiative’s award numbers U01DA055352, U01DA055353, U01DA055366, U01DA055365, U01DA055362, U01DA055342, U01DA055360, U01DA055350, U01DA055338, U01DA055355, U01DA055363, U01DA055349, U01DA055361, U01DA055316, U01DA055344, U01DA055322, U01DA055369, U01DA055358, U01DA055371, U01DA055359, U01DA055354, U01DA055370, U01DA055347, U01DA055357, U01DA055367, U24DA055325, and U24DA055330. In addition, it was supported by funds (AA) from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $473,925 with 15% financed with non-governmental sources, and funds (AEZ) from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant U54 TR002014-05A1. The content, views, and opinions presented in this manuscript are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy, or position of the NIH, HRSA, HHS, the U.S. Government, or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Competing interests

None.