In “White Man’s IR: An Intellectual Confession,” David Lake wrote that international relations (IR), at least in the United States, is a “relatively homogenous” field of study that consists of a set of individuals who are “mostly white (85 percent), mostly male (68 percent)” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1112). Lake then made a candid confession that he, as “a white man,” is “a beneficiary” of the “mainstream” of the profession and that his “privileged [intellectual] life experience” is reflected in his theorizing about world politics (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1113). Following from this self-reflection, he continued as follows: “I would be a better scholar were I surrounded not by other white males but by a more diverse community of researchers.…By broadening participation, we open the discipline to new experiences, new intuitions, new theories, and ultimately a better understanding of world politics” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1117). Naturally, he concluded his paper with a call for “greater diversity” in terms of race/culture and gender in the academy. This call, of course, is premised on his belief that IR will be a more diverse and better field of study if we embrace varied “life experiences and intuitions,” especially those of “marginalized” scholars, about politics and how the world works (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1116–18).

While praising his frank “intellectual confession” and concurring with his admonition, I also believe that his call for “greater diversity” in IR and his approach to realizing it need to be subject to critical scrutiny. For this reason, as a “non-white” scholar working in a “non-Western” IR community, I want to make my own confession to better understand what is at stake in promoting diversity in the academy from a different angle and to help achieve Lake’s ultimate goal: “enrich[ing] the intellectual breadth of the field” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1117).

The key to enhancing diversity and improving IR, according to Lake, lies in embracing “underrepresented minorities” (e.g., IR scholars of color). They have different life experiences and intuitions. “By broadening participation,” IR can incorporate different and new perspectives, which in turn helps us to capture “the larger patterns” of international politics and promote theoretical “progress” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1117–18). This is a straightforward as well as important insight, given the co-constitutive relationship among experience, intuition, and theory. As Lake noted, rightly in my view, “[a]ll theories are ultimately based on [scholars’] intuitions, insights,” while intuitions and insights reflect their “lived experiences” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1113–14). Moreover, IR, like all social science fields, is not exogenously given but rather what we scholars make of it. If, for example, we are living in a “Western-centric” IR world (Buzan Reference Buzan2016, 156; see also Acharya Reference Acharya2016; Hobson Reference Hobson2012), that world has emerged from our own practice—as individuals and as a collective—and our willingness to persist with the mainstream (i.e., Western) perspective. If not from us, then from where? Ex nihilo? Scholars from diverse racial, gender, and cultural backgrounds, therefore, are necessary for achieving greater diversity and progress in IR.

At the same time, however, my own lived experience and intuitions gained in working in “non-white” (or, in Lake’s words, “underrepresented” and “marginalized”) IR communities indicate that Lake’s proposed remedy is insufficient.

Moreover, IR, like all social science fields, is not exogenously given but rather what we scholars make of it. If, for example, we are living in a “Western-centric” IR world (Buzan Reference Buzan2016, 156; see also Acharya Reference Acharya2016; Hobson Reference Hobson2012), that world has emerged from our own practice—as individuals and as a collective—and our willingness to persist with the mainstream (i.e., Western) perspective.

WILL “MARGINALIZED” SCHOLARS AND THEIR DIFFERENT LIFE EXPERIENCES INDUCE “GREATER DIVERSITY” IN IR?

Several scholars expect that “US parochialism” and “growing interest in IR outside the core [i.e., the United States], in particular, in ‘rising’ countries such as China” would lead to the waning of American disciplinary power while opening up new spaces for the study of international relations (Tickner Reference Tickner2013, 629; see also Acharya and Buzan 2010; Shambaugh and Jisi Reference Shambaugh and Jisi1984; Tickner and Waever 2009). Kristensen and Nielsen (2013, 19) argued that “[t]he innovation of a Chinese IR theory is a natural product of China’s geopolitical rise, its growing political ambitions, and discontent with Western hegemony.”

In addition, it is well known that Chinese scholars have long been trying to develop an IR theory with “Chinese characteristics.” Qin (2011, 313) of China Foreign Affairs University asserted that it “is likely and even inevitable” that a Chinese IR theory will “emerge along with the great economic and social transformation that China has been experiencing.” In this regard, Marxism, Confucianism, “Tianxia” (天下, “all-under-heaven”), the Chinese tributary system, and the philosophy of Xunzi or Hanfeizi are all brought in as theoretical resources of “Chinese IR” or “enriching” extant IR theories “with traditional Chinese thought” (Qin Reference Qin2016, 33; Wan Reference Wan2012; Wang Reference Wang2011; Yan Reference Yan2011, 255; Zhang Reference Zhang2012; Zhao Reference Zhao2009).

Chinese IR Scholarship (in Comparison to American IR)

For these reasons, there has been a reasonable anticipation that theoretical or epistemological approaches employed by the Chinese IR community are markedly different from American IR, and that Chinese scholars will make the field more colorful or critical. Nevertheless, several empirical investigations of how IR is researched and taught in China—as well as my experience—reveal the opposite. There is a clear lack of difference between American and Chinese IR: the American theoretical terrain is dominated by three perspectives—that is, realism, liberalism, and conventional constructivism—and both American and Chinese IR scholarships are committed to positivist epistemology.Footnote 2 To clarify this point, I first briefly review research and teaching trends in contemporary American IR. Because there are a number of excellent studies that explore how IR is researched and taught in the United States, the following investigation builds on these studies.

The comprehensive research of Maliniak and colleagues (Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Oakes, Peterson and Tierney2011), which analyzed recent trends in IR scholarship and pedagogy in the United States using the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) survey data, demonstrated that more than 70% of contemporary IR literature produced in the United States falls within the three theoretical paradigms—realism, liberalism, and conventional constructivism—all of which lie within the epistemological ambit of positivism. Of course, constructivists are less likely to adopt positivism’s traditional epistemology and methodology than scholars working within the other two theoretical paradigms. However, “most of the leading constructivists in the United States…identify themselves as positivist” (Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Oakes, Peterson and Tierney2011, 454, fn. 42). More specifically, approximately 70% of all American IR scholars surveyed describe their work as positivist. Furthermore, younger IR scholars are more likely to call themselves positivists: “65% of scholars who received their PhDs before 1980 described themselves as positivists, while 71% of those who received their degrees in 2000 or later were positivists” (Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Oakes, Peterson and Tierney2011, 453–6).

The fact that IR is largely organized around the three theoretical paradigms also is evident in the classrooms of American colleges and universities. A series of surveys conducted by the TRIP Project shows that IR faculty in the United States devote substantial time in introductory IR courses to the study or application of the major theoretical paradigms, particularly realism. Although its share of class time may have declined, realism still dominates IR teaching in the United States. For example, 24% of class time in 2004, 25% in 2006, and 23% in 2008 was devoted to this paradigm; these percentages are larger than for any other theoretical paradigm.Footnote 3 It is not surprising that this trend is consistent with the content of American IR textbooks. Matthews and Callaway’s (2015, 190–207) content analysis of 18 undergraduate IR textbooks currently used in the United States demonstrated that most of the theoretical coverage is devoted to realism, followed by liberalism, with constructivism a distant third. In summary, the attention of American IR scholarship is confined to the three theoretical paradigms, and there is a strong and increasing commitment to positivist research among American IR scholars.

Is Chinese IR different? To answer this question, my research team first searched the databases of four leading academic journals in the IR field in China—国际政治研究 (Journal of International Studies), 现代国际关系 (Journal of Contemporary International Relations), 外交评论 (Journal of Foreign Affairs Review), and 世界经济与政治 (Journal of World Economics and Politics)—and analyzed the abstracts of all articles published in Chinese in these journals in a recent 20-year period (1994–2015) to determine to which theoretical paradigms they are committed. The results showed that 78% of the Chinese theoretical articles surveyed (3,739 articles) fit within the three paradigms (i.e., realism, liberalism, and constructivism). It is interesting that the majority of articles focus on liberalism.Footnote 4 Recent studies on developments in IR theory in China reached similar conclusions. Shambaugh’s (2011, 347) work, which analyzed articles published in Chinese IR journals between 2005 and 2009, demonstrated that realism, liberalism, and constructivism dominate Chinese IR theory articles—with realist articles being the most numerous. Qin (2011, 249) also observed that “most of the research works in China in the last 30 years have been using the three mainstream American IR theories [realism, liberalism, and constructivism].”

The results showed that 78% of the Chinese theoretical articles surveyed (3,739 articles) fit within the three paradigms (i.e., realism, liberalism, and constructivism). It is interesting that the majority of articles focus on liberalism.

In addition, I analyzed the syllabi of Chinese universities’ introductory IR theory courses for the 2013–2014 academic year. This investigation was based on 23 syllabi gathered from 21 faculty members who teach and/or conduct research on international politics at eight major Chinese universities, including Beijing University and Tsinghua University. Findings of the investigation showed that realism, liberalism, and constructivism account for the majority of class time. For example, the most frequently appearing reading in the Chinese IR syllabi is the canonical neorealist work, Waltz’s Theory of International Politics (1979). Correspondingly, when the meaning (or purpose) of theory is taught or discussed in an IR classroom in China, what primarily is invoked is a positivist understanding of the role of theory—namely, “generality.” Even in discussions on building an IR theory with “Chinese characteristics,” several Chinese IR scholars argue that such a theory “should seek universality, generality” to be recognized as a “scientific” enterprise (Song Reference Song2001, 68). Interestingly (and naturally, from a socio-epistemic perspective), this positivism-oriented understanding of theory and epistemology is more easily discernible in studies by the younger generations of Chinese IR scholars who have attended American universities (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2011). They tend to remain skeptical of attempts to build an “indigenous” IR theory (Wan Reference Wan2012).

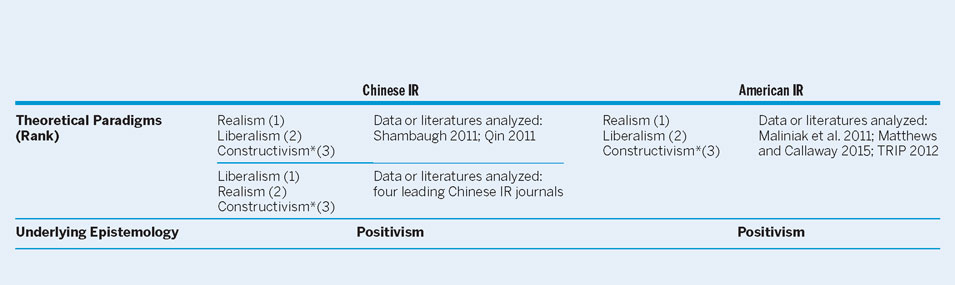

In short, the emerging Chinese IR scholarship is much in line with American IR: both are based largely on positivist epistemology and the three theoretical paradigms committed to it (see table 1).

Table 1 Dominant Theoretical Paradigms in the Chinese and American IR Communities

* Following Hopf’s (1998) distinction, constructivism here points to conventional constructivism, not critical variant.

Other Asian IR Communities

It is interesting—and unfortunate from a pluralist perspective—that a lack of attention to alternative or critical approaches also is visible in other Asian IR communities. For example, I analyzed the abstracts of all theoretical articles published in the Korean Journal of International Relations (KJIR)—the most-cited Korean IR journal—between 2002 and 2017. The results showed that the three theoretical paradigms remained at the center of discussion: of the 234 articles analyzed, only 2% (five articles) related to critical theory and/or feminism, whereas 84% (198 articles) were devoted to liberalism, realism, or constructivism.Footnote 5

Furthermore, “American dependency” and “Western-centrism” continued to dominate the “Korean-style” IR theory-building enterprise (Cho Reference Cho2015, 682). Korean IR scholars often argue that Korea should develop a “Korean School” of IR on the basis of its unique history and traditions. However, they explore how to develop a Korean IR theory and judge its success largely from a positivist perspective, considering “universalism” and American IR as the key and global reference points. In this regard, Cho observed that Korean IR scholarship has “appeared to be a staunch disciple of” American IR—especially in the sense that “political science and IR in South Korea still tends to prefer American doctoral degrees to domestic or non-American ones” and that “PhDs from the US have an advantage in the South Korean academic job market” (Cho Reference Cho2015, 681–3; see also Yu and Park Reference Yu and Park2008).

Japan also has a clear tendency to adhere to a positivist understanding of science and to utilize existing mainstream theories or concepts as the central reference point in international studies. Some claim that Japanese contributions to IR, particularly those of pre–World War II Japanese thinkers, should be considered original and receive greater recognition (Inoguchi Reference Inoguchi2007). However, Japanese IR—as Chen’s analysis (2012, 463) demonstrated—“reproduces, rather than challenges, a normative hierarchy” embedded in IR “between the creators of Westphalian norms and those [at] the receiving end.” Yamamoto (2011, 274) made a similar observation about Japanese IR scholarship when he explored how international studies have evolved in Japan in the postwar period: “research designs that seek generality and causality, statistical and mathematical modelling…have increasingly become popular” in political science fields in Japan.

In summary, there is little difference between research trends in the American and Asian (i.e., Chinese, Korean, and Japanese) IR communities: the three theoretical paradigms—namely, realism, liberalism, and constructivism—remain the dominant influence across the Western (i.e., American) and non-Western (i.e., Asian) IR communities. These academic communities are committed to a positivist epistemology and methodology.

“GREATER DIVERSITY” THROUGH REFLEXIVE DIALOGUE

This is a surprising (and perhaps disappointing) finding, particularly for those—including David Lake—calling for greater diversity in IR. As we know, Asians have different “life experiences and intuitions” than Americans and Europeans. Moreover, Chinese IR scholars have attempted to develop new or indigenous theories for more than two decades. In contrast to general expectations, a “greater diversity of scholars” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1119) does not lead to greater diversity in terms of how we conduct IR or understand world politics. Although we “marginalized” scholars have different life stories and thus different intuitions, these differences do not naturally translate into new ways of knowing. Why?

In contrast to general expectations, a “greater diversity of scholars” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1119) does not lead to greater diversity in terms of how we conduct IR or understand world politics. Although we “marginalized” scholars have different life stories and thus different intuitions, these differences do not naturally translate into new ways of knowing. Why?

Lake confesses as follows: attempts to enhance diversity are “often resented by currently privileged groups…as a ‘watering down’ of standards in the discipline” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1117). The “mainstream” of the profession creates “a self-reinforcing community standard” by acting as “gatekeepers” regarding what is studied and how—although these gatekeepers are “rarely self-conscious in their biases and even less…intentional in their exclusionary practices” (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1116).

It is true that greater diversity in IR is obstructed by this gatekeeping on the part of the Western mainstream. However, from my perspective, what is of more concern is the fact that “marginalized” scholars—even those working outside of the mainstream/American IR academy—tend to pursue for themselves the community standard established by the “gatekeepers.” We “marginalized” scholars, despite our different lived experiences, follow the research standard set by the mainstream rather than redefining how we theorize about world politics, what counts as a valid question, and what can count as valid forms of evidence and knowledge. This is not because Chinese (and Asian) scholars are trying to emulate their American counterparts but rather because they are socialized into “the discipline of the discipline” that treats a positivist approach/theory as the normal way of “doing” IR (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1117).

Critical Self-Reflexivity

Given the previous discussion, Lake’s call and solution for promoting “greater diversity” in the field must be reconsidered in terms of reflexivity—more specifically, critical self-reflection by “marginalized” scholars. A diverse community of researchers is one thing; the translation of their varied and different experiences into disciplinary practice is quite another. Whereas the former might be a necessary condition for achieving greater diversity in IR, it is not a sufficient one. We must go beyond arguing that IR has to be more attentive to underrepresented minorities.

Of course, I agree with Lake’s key point that diversity in the study of international politics can be enhanced by “broadening [the] participation” of “underrepresented” or “marginalized” groups of IR scholars (Lake Reference Lake2016, 1116–18). This is true not only because they have different life experiences but also because it is unlikely that a push to increase diversity in IR and denaturalize the (narrowly constituted) mainstream paradigm will come from the mainstream as such. For example, Mearsheimer (2016, 147), a mainstream IR theorist, explicitly distanced himself from recent calls to broaden the theoretical horizons of IR beyond American dominance.

Yet, this by no means indicates that any or every underrepresented or marginalized IR scholar will attempt to open up the field. As a non-white (i.e., “marginalized”) scholar living and working in the Asian (i.e., “underrepresented”) IR community, I must confess that many of us accept the present status of marginalization and work to be recognized by the mainstream of the profession. Who, then, is likely to initiate and lead the increase of diversity in IR? The role of changing the parochial landscape of IR falls to critical, conscious, and reflexive individual scholars who are consciously willing to translate our different life experiences and intuitions into practice and who offer strong support for that undertaking. This critical reflexivity goes beyond whether we are white or non-white, Western or non-Western, male or female.

Fundamentally, we scholars are what Gramsci (Reference Gramsci1971) called “organic intellectuals.” We are not merely consumers and producers of ideas and ideologies but also “organic organizers” of them. Thus, in Gramscian terms, we are “organizers of hegemony” in that we play a central role in formulating “common sense” (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971, 199, 441). Furthermore, as organic intellectuals, we have the capability to politically organize the masses by exercising “intellectual and moral leadership” (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971, 57); as such, we can provide “cohesion and guidance to hegemony” (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971; Zahran and Ramos 2011, 28). By the same token, however, if we are in the position to offer “cohesion and guidance” in regard to (political or epistemic) hegemony, we also can weaken that hegemony by exercising the same “intellectual and moral leadership” in a way that transcends the dominant way of governing or knowing and embraces a flourishing of diverse experiences, theories, and methodologies.

Viewed in this light, our calls for greater diversity must begin with critical self-reflection. This is especially true for “marginalized” IR scholars because, as Lake (Reference Lake2016) pointed out, they have the basic resources for “greater diversity”—namely, varied life experiences and intuitions. What do we research philosophically, theoretically, methodologically, or empirically? How do we carry out peer review of other research? Most important, what and how do we teach in the classroom? In other words, we “marginalized” scholars should critically ask ourselves whether our research and teaching practices have been rich enough to go beyond the mainstream paradigm and do justice to our varied life experiences and intuitions (i.e., multiplicity) in both our publications and our classrooms. To accept and practice alternative but equally valid approaches to producing knowledge, we must first problematize ourselves—specifically, our routinized behavior and actions that continue to fall within the mainstream paradigm.

Diversity and Dialogue

Of course, I am not saying that we “marginalized” scholars should seek to discard or disavow the existing (i.e., Western/positivist-centric) IR in the process of developing alternative approaches and understandings. Rather, our calls for diversity in IR should be accompanied by our efforts to promote dialogue and engagement across growing theoretical and spatial divides. As Lake (Reference Lake2011) noted elsewhere, IR currently is divided and dominated by monologue; in this state, attempts to promote greater diversity in the field can raise concerns about the fragmentation of IR scholarship. This is one main reason that some scholars take issue with pluralism in IR theory or epistemology. “Pluralism,” they contend, “masks the fact that we have an incoherent field” (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008, 298 [emphasis added]). In particular, greater divergence between the racially (or regionally) ordered professions of the field could place IR’s disciplinary coherence at risk. Levine and McCourt (2018, 104) noted that “a time may come—or, perhaps, has come—when IR scholars from different professional milieux lack any shared points of reference.”

In this sense, I must make another confession that the ongoing “broadening” IR project, whether non-Western or Global IR—in which I participate—tends to approach the problem of “Western/America-centrism” too narrowly, in terms of the geographical origins of concepts, theories, or theorists. Wemheuer-Vogelaar et al.’s study (2016, 18–24), based on the 2014 TRIP survey data, revealed that non-Western IR scholars “have geographically bounded perceptions of IR communities” and that “geography plays a central role in the Global IR debate.” Of course, it is true that non-Western worlds and their voices are on the margins of the discipline; we must grapple with this problem of marginalization and underrepresentation. The point is not that these geographically or ethnically based concerns are misplaced but rather that non-Western IR theorization projects must widen their discussion to explore the potential (or previously unrecognized) similarities and overlaps among perspectives across regions or cultures.Footnote 6

I believe that our ultimate aim should be to move IR one step closer to becoming a pluralistic and dialogical community. To this end, critical self-reflection must come first. Otherwise, the “performativity” with which a call for diversity should be accompanied is likely to remain truncated. For our agential leadership and resources to be more fully harnessed in the opening up of IR, critical self-reflection by “marginalized” groups of scholars and collective collaboration among reflexive scholars are essential. By bringing this reflexivity to our everyday practice for greater diversity in IR, new and diverse ways of “doing” IR and thus “knowing” international relations can begin to flourish. In addition, rather than developing alternative or indigenous knowledge to replace mainstream IR, we must focus on promoting dialogue between them, with the aim of creating inclusive and complementary understandings of our complex world. After all, the issue is not who is right or where we are from but instead whether we can talk to one another. I read Lake’s present article as an important contribution in this self-reflexive vein, and I see his previous studies on hierarchy and power (Lake Reference Lake1992; Reference Lake2009) and his constant calls for eclecticism and middle-range theory (Lake Reference Lake2011; Reference Lake2013) as important points of reference in this regard. I hope that my “intellectual confession” also can contribute to this important undertaking.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank anonymous reviewers and the editors of this journal for their thoughtful and constructive comments on previous versions of this article. In particular, I am indebted to David Lake’s input for tightening my arguments.