The health of any workforce is important both to the individuals within it and to their employers. Taking health in the widest sense to include general well-being and job satisfaction, it is clear that ill health poses an economic cost to employers in terms of sickness absence, early retirement and reduced productivity. In healthcare these factors translate directly and indirectly into patient satisfaction and the quality and safety of care (Reference Firth-CozensFirth-Cozens, 2001).

This article describes how doctors in general, and psychiatrists in particular, while enjoying good physical health, have levels of certain aspects of mental ill health which are higher than those of the general population. Individual and organisational causes of these problems, and appropriate interventions, are described.

The health of doctors

For almost all physical conditions, doctors have lower mortality than the rest of the population: one UK study found that, overall, deaths for doctors aged between 25 and 74 years were less than half those expected on the basis of national rates, and considered this due primarily to low smoking rates in doctors (Reference Carpenter, Swedlow and FearCarpenter et al, 2003). In the USA doctors are also less likely to smoke cigarettes (Reference Hughes, Brandenburg and BaldwinHughes et al, 1992a ). In comparisons with the general population and other professional groups, male doctors there live longer than other men and female doctors take better care of their health overall (Reference Frank, Boswell and DicksteinFrank et al, 2001).

However, when it comes to mental illness, reports on the health of doctors are not so positive. Over the past two decades a number of longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have found that doctors suffer from levels of stress, depression and substance misuse – in particular, alcohol – that are substantially higher than those of the general population. When it is considered that they belong to a relatively prosperous, middle-class profession, these elevated rates become more noteworthy; and when they in turn have a potentially deleterious effect on the care given to patients, the issue becomes of paramount importance.

Stress, depression and suicide

A number of studies, using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; Reference Goldberg and WilliamsGoldberg & Williams, 1988), have reported that the stress levels of doctors are substantially higher than the 18% shown by the general population (Reference Wall, Bolden and BorrillWall et al, 1997). This is true for all grades, including consultants (Reference Ramirez, Graham and RichardsRamirez et al, 1996). It has been proposed that the high reported levels might simply be the effect of using the potentially suggestive word ‘stress’ in questionnaires (Reference McManus, Winder and GordonMcManus et al, 1999), but this was not used in all studies quoted, and overall the findings of different studies are remarkably consistent, with about 28% of participants showing above-threshold levels of stress at any one time.

Depression and stress levels are highly related: one study of healthcare staff found that of those who had scored above threshold on the GHQ (>4), 52% had definite depressive or anxiety disorders at clinical interview (Reference Weinberg and CreedWeinberg & Creed, 2000). Anxiety in doctors has rarely been measured, but assessments of depression are more common and show levels which are often less consistent than in stress studies, perhaps because different instruments or interview schedules have been used. However, depression accounts for a large proportion of psychiatric admissions for doctors (Reference Rucinski and CybulskaRucinski & Cybulska, 1985) and is more common in doctors than in some other professional groups (Reference CaplanCaplan, 1994). Doctors in their first postgraduate year were particularly at risk during the 1980s (Reference ReubenReuben, 1985; Reference Firth-CozensFirth-Cozens, 1987), with levels of depression falling over years two and three. In a longitudinal study in the USA, Reference ReubenReuben (1985) showed a first-year peak of 29%, which fell to 22% in second-year and 10% in third-year postgraduates. As lack of sleep is related to lower mood (Reference Leonard, Fanning and AttwoodLeonard et al, 1998), it is likely that the shorter hours and greater support now given to young doctors in Europe under the European Working Time Directive will have had a beneficial effect on these levels of depression. Although women doctors have not usually been found to be significantly more stressed than their male counterparts, some studies have found higher levels of depression, despite there being no gender differences when they were students (Reference Firth-Cozens, Cox, King and HutchinsonFirth-Cozens, 2005).

Most studies of suicide around the world have reported raised rates in doctors, particularly female doctors (Reference Schernhammer and ColditzSchernhammer & Colditz, 2004). In the UK, death rates due to accidental poisoning in male consultants and suicide in female consultants were significantly raised compared with rates for the general population (Reference Carpenter, Swedlow and FearCarpenter et al, 2003). A study of recognised suicides among doctors showed that for females this was twice that of the general population, but it was lower for males (Reference Hawton, Clements and SakarovitchHawton et al, 2001). In the USA, suicide was found to be the only cause of death among doctors that was higher than in the general population (Reference Torre, Wang and MeoniTorre et al, 2005). In Scandinavia mortality from suicide was increased among doctors of both genders, particularly deaths due to self-poisoning (Reference Juel, Mosbech and HansenJuel et al, 1997).

Substance misuse

Although they smoke fewer cigarettes and take fewer illicit substances such as marijuana, cocaine or heroin than their counterparts in the general population, doctors are more likely to use alcohol and prescription medications such as minor opiates and benzodiazepines (Reference Hughes, Brandenburg and BaldwinHughes et al, 1992a ). Benzodiazepines appear to be the drug of choice for young US doctors, with 9.4% of residents having used them without medical supervision (Reference Hughes, Baldwin and SheehanHughes et al, 1992b ).

A high rate of alcohol use has been recognised as a particular problem for doctors for some decades (British Medical Association Working Group, 1998), both in studies of rates of cirrhosis (Reference Harrison and ChickHarrison & Chick, 1994) and of doctors admitted to units for the treatment of alcohol and drug misuse (Reference Brooke, Edwards and TaylorBrooke et al, 1991). There is a high rate of comorbidity between alcohol misuse and depression: a study of 100 women doctors who had recovered from alcoholism showed that 73 had serious suicidal ideation prior to sobriety, with 38 making at least one serious suicide attempt (Bissel & Skorina, 1987). Women medical students are the only student group whose alcohol intake increases over the undergraduate years to equal that of male colleagues (Reference Flaherty and RichmanFlaherty & Richman, 1993). Compared with the general public, women doctors might be particularly at risk for alcoholism and for using alcohol to cope (Reference Firth-Cozens, Cox, King and HutchinsonFirth-Cozens, 2005).

It seems that there is something about the people who enter medicine, and/or the environment in which they work, which leads to poorer mental health. Despite this, doctors frequently have no general practitioner of their own, self-medicate and continue to work even when ill (Reference Pullen, Lonie and LylePullen et al, 1995).

The health of psychiatrists

Although doctors are physically healthier than the general population, psychiatrists show significantly raised mortality overall compared with other doctors, and also for ischaemic heart disease, injury and poisoning, and colon cancer (Reference Carpenter, Swedlow and FearCarpenter et al, 2003). In a study which compared female psychiatrists with other female doctors (Reference Frank, Boswell and DicksteinFrank et al, 2001), the psychiatrists were older (perhaps because they had changed specialties), more likely to be current or ex-smokers, less likely to be married, and were in poorer health. However, it is in some areas of mental health that the differences are most pronounced.

Stress, depression and suicide

A number of cross-sectional studies have reported higher rates of depression (Reference Deary, Agius and SadlerDeary et al, 1996) and burnout among psychiatrists (Reference Kumar, Hatcher and HuggardKumar et al, 2005) than among doctors from other specialties. Longitudinal studies in the UK also suggest that psychiatrists as a group suffer from particularly high levels of stress, with the highest levels of job dissatisfaction and, together with laboratory-based doctors, the highest levels of depression. Surgeons have the lowest levels of depression and stress and the highest levels of job satisfaction. These findings were also apparent when they were students (Reference Baldwin, Dodd and WrateBaldwin et al, 1997; Reference Firth-Cozens, Caceres Lema and FirthFirth-Cozens et al, 1999; Reference Firth-CozensFirth-Cozens, 2000).

The higher depression scores among psychiatrists have been mirrored by higher suicide rates over some decades, both in the USA (Reference Rich and PittsRich & Pitts, 1980) and in the UK (Reference Hawton, Clements and SakarovitchHawton et al, 2001). A large study in the UK covering 1979–1995 found that anaesthetists, community health doctors, general practitioners and psychiatrists had significantly increased rates of suicide compared with doctors in general hospital medicine (Reference Hawton, Clements and SakarovitchHawton et al, 2001).

Alcohol and drug misuse

Studies show no consistent pattern of alcohol and drug misuse among psychiatrists. However, several studies have suggested increased misuse: for example in terms of a higher proportion of disciplinary actions for substance misuse among psychiatrists (Reference ShoreShore, 1982). Comparative studies from the USA show the highest rates of multiple drug use among doctors in psychiatry and emergency medicine, with psychiatry residents favouring benzodiazepines, amphetamines and marijuana (Reference Hughes, Baldwin and SheehanHughes et al, 1992b ). This study and others (Reference Myers and WeissMyers & Weiss, 1987) also showed psychiatrists to have the highest rates of use of all substances, and psychiatry residents to have the highest lifetime use of cigarettes, cocaine, LSD, and marijuana compared with other specialties. Both male and female psychiatrists were over-represented in a study following medical members of Alcoholics Anonymous (Reference Bissell and JonesBissell & Jones, 1976; Reference Bissell and SkorinaBissell & Skorina, 1987), although this might be because psychiatrists are more willing to be open about their condition in a group setting.

Behavioural problems

There is one other area where psychiatrists show an excess over their colleagues: that of sexual relationships with patients. In a study of the California Medical Board comparing matched groups of disciplined and non-disciplined doctors, there were almost twice as many psychiatrists, primarily men, among those disciplined, and this was significantly more likely to be for sexual relationships with patients (Reference Morrison and MorrisonMorrison & Morrison, 2001). Similarly, in a survey of sex-related offences across the USA, psychiatrists had proportionally the most actions against them: twice that of gynaecologists, who were the next highest group (Reference Dehlendorf and WolfeDehlendorf & Wolfe, 1998). Psychiatry was also the specialty with the most doctors referred for disciplinary action in the northern region of the National Health Service in England (Reference DonaldsonDonaldson, 1994a ), although the reasons for referral were not reported by specialty. Apart from the legal and professional ramifications, these findings suggest greater difficulties for some psychiatrists, particularly with sexual boundaries (see Individual causes below).

Ageing

Although the ageing process can present difficulties for all doctors in terms of increasing cognitive difficulties (Reference Turnbull, Carbotte and HannaTurnbull et al, 2000) and it has been suggested to raise issues for psychoanalysts (Reference Weiss, Kaplan and FlanaganWeiss et al, 1997), there is no evidence that ageing leads to any increased problems for psychiatrists in general.

Summary

In summary, psychiatrists have been shown to be more likely than doctors from other specialties to suffer from a range of mental health problems – those disorders whose incidence is already raised within medicine as a whole. In addition, they are over-represented in terms of violation of sexual boundaries. Given these highly consistent findings, it is important to consider causes and interventions for these problems.

Why do psychiatrists have poorer mental health?

A detailed study of healthcare staff, which compared through clinical interview the stressors and personal difficulties of those with a GHQ score > 4 (the criterion for caseness) and matched controls, found that ‘cases’ had more objective stressful situations. These included more objective work problems as well as chronic personal problems such as marital difficulties. They were also more likely to have had a previous episode of psychiatric illness and were less likely to have a confidant (Reference Weinberg and CreedWeinberg & Creed, 2000). This demonstrates that it is the combination of difficulties – individual and organisational – which cause mental health problems for healthcare staff.

Organisational causes

A large-scale study of healthcare staff in 19 UK healthcare organisations found that the proportions of staff with a score above a threshold of 3 on the GHQ–12 ranged from 17 to 33%, and indicated that the size, culture and leadership of the organisation itself play a definite part in determining the psychological well-being of its employees (Reference Wall, Bolden and BorrillWall et al, 1997). Other studies show the extent to which good or bad teams determine the stress levels of their members (Reference Carter, West, Firth-Cozens and PayneCarter & West, 1999); in fact, in aviation it has been proposed that one way to assess good teamwork is simply to consider the well-being of those within the team (Reference HackmanHackman, 1990).

Other work-related factors which are potentially damaging to psychological well-being are those well known within organisational psychology: job instability (Reference Kivimaki, Vahtera and PenntiKivimaki et al, 2000), lower discretion in how the work is done, work overload and a lack of support (Reference Payne, Firth-Cozens and PaynePayne, 1999). In addition, complaints and disciplinary actions are difficult for all doctors: a Finnish study found that medical surveillance often preceded the suicide of its female doctors (Reference Lindeman, Laara and LonnqvistLindeman et al, 1997).

Although work overload in combination with other factors can be detrimental to psychological well-being, the number of hours worked in itself has rarely been found to be a problem (Reference Weinberg and CreedWeinberg & Creed, 2000), and in one UK study psychiatrists reported fewer working demands than doctors of other specialties (Reference Deary, Agius and SadlerDeary et al, 1996). Nevertheless, difficulties with recruitment and retention of psychiatrists within the UK mean that clinical and administrative loads are in fact often high (Reference Holloway, Szmukler and CarsonHolloway et al, 2000). In addition, psychiatrists have more work-related emotional exhaustion (Reference Deary, Agius and SadlerDeary et al, 1996), which suggests that their work is more emotionally difficult than that of other doctors. For example, the work is often isolated and there may be the threat of violence (Reference Guthrie, Tattan and WilliamsGuthrie et al, 1999; Reference Korkeila, Toyry and KumpulainenKorkeila et al, 2003); moreover, patient suicide has a definite psychological impact on some psychiatrists (Reference Alexander, Klein and GrayAlexander et al, 2000; Reference Ruskin, Sakinofsky and BagbyRuskin et al, 2004). There are ambiguities about responsibilities of the members of multidisciplinary teams, and public attitudes towards mental illness and perhaps towards psychiatrists themselves can increase a sense of isolation (Reference Margison, Payne and Firth-CozensMargison, 1987). Government policy means that psychiatrists have a particularly difficult role in terms of discharge planning and risk assessment, and any deaths which result from the discharge of dangerous patients are dealt with in a culture of blame (Reference Holloway, Szmukler and CarsonHolloway et al, 2000).

There are therefore many work-related and cultural pressures that can increase the likelihood of mental health problems for psychiatrists. However, these pressures are faced by all psychiatrists and so there are also likely to be individual factors which tip the scales towards illness.

Individual causes

Job-related stress and depression, with possible comorbid substance misuse, reflect objective work difficulties combined with some form of personal vulnerability that is not just a result of current life events but is also due to dispositional factors and earlier mental state (Reference Firth-Cozens, Firth-Cozens and PayneFirth-Cozens, 1999). The fact that doctors who have chosen psychiatry have high mean stress and dissatisfaction scores as students as well as when they are established in their careers (Reference Firth-Cozens, Caceres Lema and FirthFirth-Cozens et al, 1999) suggests that, for a few doctors, the choice of psychiatry might not have been ideal. In a further follow-up of the study cohort (Reference Firth-CozensFirth-Cozens, 2000), laboratory-based doctors, who also had high scores for stress and depression as students, had considerably lower stress levels as consultants (Table 1). One group had chosen a specialty in which patient contact is minimal – and this was a major reason given for their choice – whereas the other had chosen a specialty with a high level of patient contact, and this has not worked well for some. Although the number completing all assessments over the 17 years is small and needs to be confirmed by larger studies, the findings are consistent with other studies (Reference Baldwin, Dodd and WrateBaldwin et al, 1997).

Table 1 Mean levels of depression (SCL–90: Reference Derogatis, Lipman and CoviDerogatis et al, 1973) and stress (GHQ–12: Reference Goldberg and WilliamsGoldberg & Williams, 1988) in different specialties: follow-up over 17 years

| Senior doctors | Students 1 | Pre-registration house officers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | n | Depression | Stress | Stress | Depression | Stress |

| Psychiatry | 10 | 1.16 | 16.0 | 13.4 | 1.6 | 14.3 |

| General practice | 10 | 0.79 | 12.9 | 11.5 | 1.1 | 12.3 |

| General medical | 24 | 0.84 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 1.1 | 12.7 |

| Surgery | 9 | 0.73 | 10.6 | 10.5 | 0.8 | 9.5 |

| Anaesthetics, radiology | 12 | 0.78 | 11.57 | 13.0 | 1.1 | 13.3 |

| Laboratory | 11 | 1.07 | 11.89 | 12.7 | 1.4 | 15.5 |

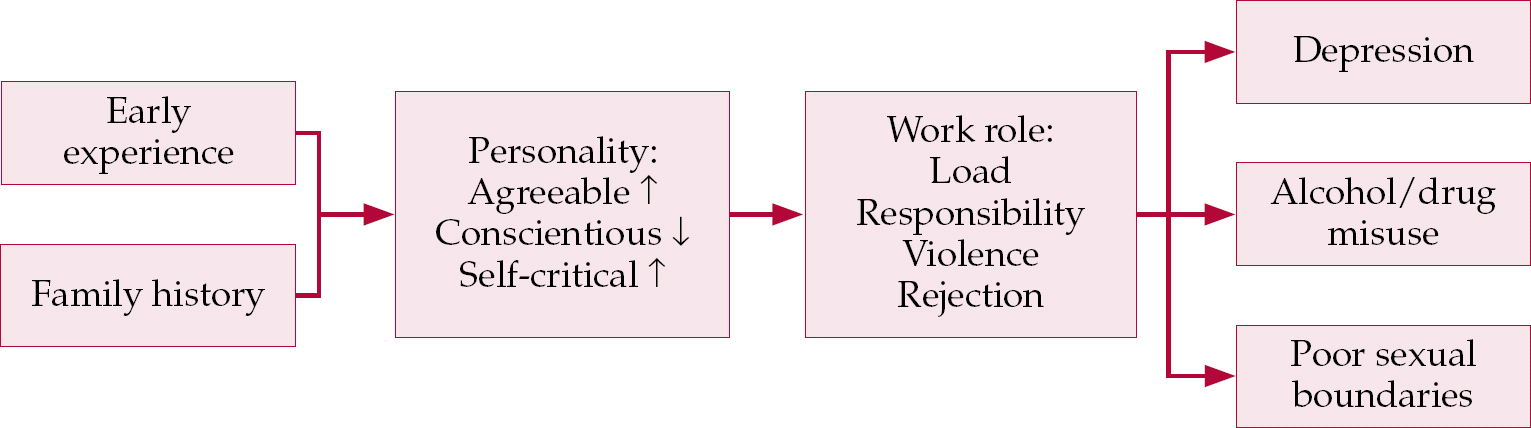

It is likely that some psychiatrists are predisposed to problems prior to entry into the specialty: female psychiatrists are more likely than women in other specialties to report personal or family histories of psychiatric disorder (Reference Frank, Boswell and DicksteinFrank et al, 2001). Similarly, mental health workers in general are more likely to have suffered early experiences of abuse and trauma than other healthcare staff (Reference Elliott and GuyElliott & Guy, 1993). In terms of personality, Reference Deary, Agius and SadlerDeary et al(1996) found that psychiatrists differed from other specialties in being more open and agreeable and less conscientious, as well as experiencing more severe depression and more neurosis, the latter being a difference found by others over some decades (Reference WaltonWalton, 1969). The lower levels of conscientiousness alongside higher neuroticism might have made medicine a more difficult profession to tackle for these psychiatrists even in student days.

It might be that the agreeable nature of some of those who choose psychiatry, together with a higher prevalence of pre-existing mental health problems and potentially damaging early experiences, leads to overinvolvement and to a number of mental health problems. Overinvolvement may lead to sexual misconduct, but also to a sense of rejection by clients, who are rarely grateful, and especially by those who die by suicide, and by the public and colleagues, who sometimes do not appreciate the complexity, difficulty and responsible nature of a psychiatrist's work. This – particularly when linked to high degree of self-criticism (Reference Brewin and Firth-CozensBrewin & Firth-Cozens, 1997) – can result in depression, which may sometimes emerge as behavioural problems or be associated with the use of alcohol and other substances to help the psychiatrist to cope. For those who entered medicine to make good some early family unhappiness or illness, as doctors and other healthcare workers often do (Reference MalanMalan, 1979; Reference Paris and FrankParis & Frank, 1983; Reference Firth-CozensFirth-Cozens, 1998), the difficulties presented by a career in psychiatry may be particularly damaging. The model for the development of mental ill health in psychiatrists is presented in Fig. 1. Of course, psychiatry, like any other medical specialty or occupation, will have a proportion of people with personality disorders which lead them into sexual abuse of others independently of any job-related stressors (Reference Garfinkel, Bagby and WaringGarfinkel et al, 1997).

Fig. 1 Model for the development of mental ill health in psychiatrists as suggested by research findings.

A further cause suggested for the mental health problems of psychiatrists and doctors in general is their failure to seek and receive adequate treatment – a finding that is consistent across continents (Reference Holloway, Szmukler and CarsonHolloway et al, 2000; Reference Center, Davis and DetreCenter et al, 2003). Doctors are reluctant to seek advice formally (Reference Pullen, Lonie and LylePullen et al 1995), and appear to find it difficult to report the mental health problems of colleagues (Reference Firth-Cozens, Firth and BoothFirth-Cozens et al, 2003).

What can be done?

There are a number of ways in which the health of psychiatrists might be improved and these are outlined below.

Career counselling

Career counselling is now a formal part of the foundation years of medical training in the UK. However, counsellors should have specialised training to ensure that they are aware of past experiences that might motivate those thinking about entering psychiatry.

Selection

There is a strong argument for psychometric and/or psychodynamic procedures as part of the selection process for those wishing to enter psychiatry. Although we are some way from being able to provide an evidence base for this, there is sufficient knowledge of some forms of vulnerability, such as family illnesses, personality and problems during undergraduate years. Such selection would not be to preclude certain groups of people (although selection is designed to do just that) but rather to ascertain whether applicants have already tackled the issues which emerge or are willing to do so. Psychodynamic and psychometric assessments are used for selection in the commercial world and psychometric assessments are used by the National Clinical Assessment Service (http://www.ncas.nhs.uk) when things go wrong, so why not at the selection stage?

Training and CPD

Training and supervision in psychiatry need to take into account the potential vulnerability of young doctors and focus more on teaching trainees ways in which they might help each other and themselves, for example through techniques for stress management and the development of academic and outside interests (Reference Kumar, Hatcher and HuggardKumar et al, 2005). However, it is equally important that these issues should be addressed throughout a doctor's career via supervision and CPD, which should also include training in team leadership and risk management (Reference Holloway, Szmukler and CarsonHolloway et al, 2000). Appraisal and mentoring should make lifelong learning more a reality and should play an important part in the support of consultants.

Recruitment

An unpublished UK study of career choice and psychiatry among groups of pre-registration house officers, senior house officers and specialist registrars in psychiatry (further details available on request) revealed that psychiatry was a second choice for almost all of those who had entered the specialty. Suggested ways for increasing recruitment in psychiatry are given in Box 1. †

Box 1 Encouraging recruitment in psychiatry

-

• Provide good, enthusiastic undergraduate teaching with a reasonable spread of patients to show the variety

-

• Demonstrate the intellectual side of psychiatry and its strong evidence base

-

• Emphasise the life-saving possibilities of psychiatry

-

• Publicise its life-style benefits and practice advantages (ability to spend more time with patients and on decision-making, the quality of the training, the chance to innovate)

Systems for recognising when things are going wrong

Problems with doctors – whether concerning performance, health or both – take a considerable time to be reported formally (Reference DonaldsonDonaldson, 1994b ), and by then may have become too entrenched to be dealt with successfully. Good systems for recognising and reporting doctors’ difficulties are still in their infancy, and procedures for addressing these problems are largely haphazard (North East London NHS Strategic Health Authority, 2003). One simple means would be to provide extra support for all doctors during life events, complaints and disciplinary actions, and for psychiatrists when a patient dies by suicide – all factors known to precede the onset of depression in doctors. Psychiatrists and psychologists, with their particular skills in this field, could lead the way in developing such formal support systems, both for themselves and for others. The failure of medical professionals to seek and receive adequate treatment could be addressed by the implementation of stricter guidelines, either by the medical Royal Colleges or as part of a wider initiative for greater patient safety.

Training for dealing with colleagues with mental health problems

We have many good and often brief interventions to help people with psychological problems such as depression and anxiety, and doctors have been shown to recover well from alcohol and drug misuse using 12-step programmes (Reference Carlson and DiltsCarlson & Dilts, 1994; Reference Khantzian and MackKhantzian & Mack, 1994; Reference LloydLloyd, 2002; Anonymous, 2006). Despite the existence of effective interventions, there are several reasons why these are often not used. First, doctors with health problems are reluctant to seek adequate or appropriate help for themselves; second, medical students (Reference Roberts, Warner and RogersRoberts et al, 2005) and doctors appear to be unsure about the mental health problems of their colleagues and to be less likely to report them (Reference Firth-Cozens, Firth and BoothFirth-Cozens et al, 2003). Finally, many doctors find it unusually difficult to treat illness in other doctors appropriately (Reference Ingstad and ChristieIngstad & Christie, 2001). Occasionally the inadequacy of the help provided for mental health problems may contribute to tragic consequences (North East London NHS Strategic Health Authority, 2003). Part of psychiatry training could be devoted to this crucial area since much of the blame when things go wrong is likely to be placed on those providing help (Reference CalillCalill, 2006).

Conclusions

The health of doctors in general, and psychiatrists in particular, has been a vibrant area of research for the past two decades. In that time we have identified the problem areas and isolated some of the key causes. What have not yet been identified are systematic ways of dealing with these problems, although ways to do so have a growing evidence base (Reference Firth-CozensFirth-Cozens, 2001). Psychiatrists need to play a key role in demonstrating the importance, for the doctors concerned and for reasons of clinical governance, of dealing with the mental health problems of doctors. In addition, they need to be central in delivering appropriate training to protect mental health and in developing appropriate interventions for when things go wrong.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 Causes of death which are more common in psychiatrists than in other doctors include:

-

a Parkinson's disease

-

b diabetes

-

c suicide

-

d lung cancer

-

e osteoarthritis.

-

-

2 Drugs which are reported as most often misused by psychiatrists are:

-

a antidepressants

-

b benzodiazepines

-

c cocaine

-

d heroin

-

e chlorpromazine.

-

-

3 The main cause of the elevated rates of mental ill health in psychiatrists is:

-

a an interaction between the role and the personality and background of some psychiatrists

-

b psychiatric patients are difficult to treat

-

c the working conditions would make anyone drink too much

-

d people who enter psychiatry are already psychologically disturbed

-

e most psychiatrists need more training in order to do the job.

-

-

4 Organisational interventions which might reduce mental health problems among psychiatrists include:

-

a selection into medical school

-

b telling young doctors that psychiatry is an easy option in order to increase recruitment

-

c providing a full counselling service for psychiatrists

-

d selection into psychiatry to include psychometric assessments alone

-

e providing special training for working with doctors who are sick.

-

-

5 A psychiatrist recognising mental health difficulties in a colleague should:

-

a talk to them and provide them with treatment

-

b discuss this with their clinical director

-

c tell them to phone a help-line

-

d tell their chief executive

-

e tell the National Clinical Assessment Service.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | T | b | F | b | F | b | T |

| c | T | c | F | c | F | c | F | c | F |

| d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | F | e | F | e | F | e | T | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.