Introduction

Background

Formal volunteering is a productive activity undertaken by individuals to help others in a collective style and within an organisational environment, without receiving any payment or only a minimal remuneration (Hustinx and Lammertyn, Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003; Musick and Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2008; Morrow-Howell, Reference Morrow-Howell2010). Doing voluntary work, in particular after retirement age when access to the labour market is limited, plays a crucial role in the context of active ageing policies – one of the strategic policy solutions to demographic ageing in Europe (Walker and Maltby, Reference Walker and Maltby2012) – as it stimulates healthy ageing and wellbeing in later life which reduces pressure on health-care systems (Musick et al., Reference Musick, Herzog and House1999; Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Hinterlong, Rozario and Tang2003; Harris and Thoresen, Reference Harris and Thoresen2005; Lum and Lightfoot, Reference Lum and Lightfoot2005; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Slagsvold, Aartsen and Deindl2018; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Duan and Xu2020; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhang, Zhang, Shen, Wang, Cheng, Tao, Zhang, Yang, Yao, Xie, Tang, Wu and Li2022). Yet, the actual number of older volunteers and the intensity with which people do voluntary work is low in many European countries. A study based on the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) and the Norwegian Lifecourse, Ageing and Generation (NorLAG) study showed that the rate of formal volunteering varies from 20 to 30 per cent in the north-west of Europe to less than 10 per cent in the south-east (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Slagsvold, Aartsen and Deindl2018). While the prevalence of voluntary work is high in Norway compared to other European countries, less than 10 per cent of Norwegian older adults spend more than 3–4 hours per week on voluntary work (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Slagsvold, Aartsen and Deindl2018), and this percentage is shrinking (Arbeids- og Sosialdepartementet, 2016). People aged between 67 and 74 spend most time volunteering (Hansen and Slagsvold, Reference Hansen and Slagsvold2020b). Therefore, understanding the underlying factors of hours invested in voluntary work may help voluntary organisations to adjust the voluntary work to better fit the volunteers' needs and preferences rather than only focus on recruitment.

There is evidence of inequalities in volunteering, as it is mainly the higher-educated, higher-social status native man and those with better functional ability who engage in organisational voluntary work (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018; Southby et al., Reference Southby, South and Bagnall2019), which calls into question how volunteering can be more inclusive. Our study thus also pays attention to social oppression, including structural forces that limit possibilities to volunteer and push people out of voluntary work. To shed further light on variations in the intensity of volunteering, we examine a wide range of factors potentially associated with volunteering intensity derived from insights from Wilson and Musick's (Reference Wilson and Musick1997) resource theory and Clary and Snyder's (Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991, Reference Clary and Snyder1999) functional theory, while taking into account potential oppressive factors.

Previous studies

In studies on volunteering, two approaches have been dominant: (a) an objective approach which observes ‘people's objective attributes or their social position’, including explicit factors reflected in various socio-economic and individuals' resources (Musick and Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2008: 37); and (b) a subjective approach, including implicit factors, such as motivational factors (Einolf and Chambré, Reference Einolf and Chambré2011). Various researchers have documented the association between resources and older volunteering (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997; Warburton and Crosier, Reference Warburton and Crosier2001; Choi, Reference Choi2003; Smith, Reference Smith2004; Tang, Reference Tang2005, Reference Tang2008; Musick and Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2008; Lee and Brudney, Reference Lee and Brudney2012; Cramm and Nieboer, Reference Cramm and Nieboer2015; Dury et al., Reference Dury, De Donder, De Witte, Buffel, Jacquet and Verté2015) and motivational factors and older volunteering (Clary and Snyder, Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991; Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder, Ridge, Copeland, Stukas, Haugen and Miene1998; Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Andersen and Urban2000; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Terry, Roseman and Sharpiro2001; Meier and Stutzer, Reference Meier and Stutzer2008; Finkelstien, Reference Finkelstien2009). These studies consistently show that more resources and stronger motivation are associated with an elevated likelihood of volunteering.

Despite the progress in our understanding of factors related to later-life volunteering, there are several knowledge gaps. First, previous studies mainly focused on examining the differences between volunteering and non-volunteering (Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Terry, Roseman and Sharpiro2001; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Holly, Brian, Kathryn and Craig2015; Bekkers et al., Reference Bekkers, van Ingen, de Wit and Broese van Groenou2016), but little is known about the relationship between the type of motivation and time spent on voluntary work. Secondly, most studies are based on either the resource theory by Wilson and Musick (Reference Wilson and Musick1997) or the functional approach by Clary and Snyder (Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991, Reference Clary and Snyder1999) to examine the factors associated with older volunteering, but few examined the relative importance of resources and motivations for voluntary intensity. Thirdly, most studies on voluntary work have been conducted in the United States of America, but there are also studies from Europe, China and Australia (Ma and Konrath, Reference Ma and Konrath2018). Still, there is a need to study volunteering in different countries because cultures, politics to stimulate voluntary work, welfare regimes and patterns of volunteering may affect the strength of associations with voluntary work (Principi et al., Reference Principi, Chiatti, Lamura and Frerichs2012). Despite some notable exceptions (e.g. Wollebæk et al., Reference Wollebæk, Sætrang and Fladmoe2015; Folkestad and Langhelle, Reference Folkestad and Langhelle2016; Hansen and Slagsvold, Reference Hansen and Slagsvold2020a), not many studies focused on countries with strong welfare state provisions and culture of voluntary work, such as in Norway. Lastly, the two theoretical approaches that have been dominant do not consider potential structural barriers to volunteering leading to substantial inequalities, while there is solid evidence that voluntary work is hierarchically stratified, with more opportunities for the dominant groups in the society (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022; Meyer and Rameder, Reference Meyer and Rameder2022). At the same time, the demand to recruit the most potential volunteers may exclude disadvantaged groups from volunteering. This study aims to address some of these shortcomings by answering two main research questions:

(1) Which resources are associated with volunteering intensity in Norway?

(2) Which motivations are associated with volunteering intensity, in addition to the resources?

Due to the further concern on the structural inequality in volunteering, our study additionally considers factors reflecting categories of differences, structural factors and other control factors. This will answer our third research question:

(3) Is there any evidence for oppressive barriers that may lead to inequalities in volunteering intensity?

Towards a combined conceptual framework of older adults' volunteering

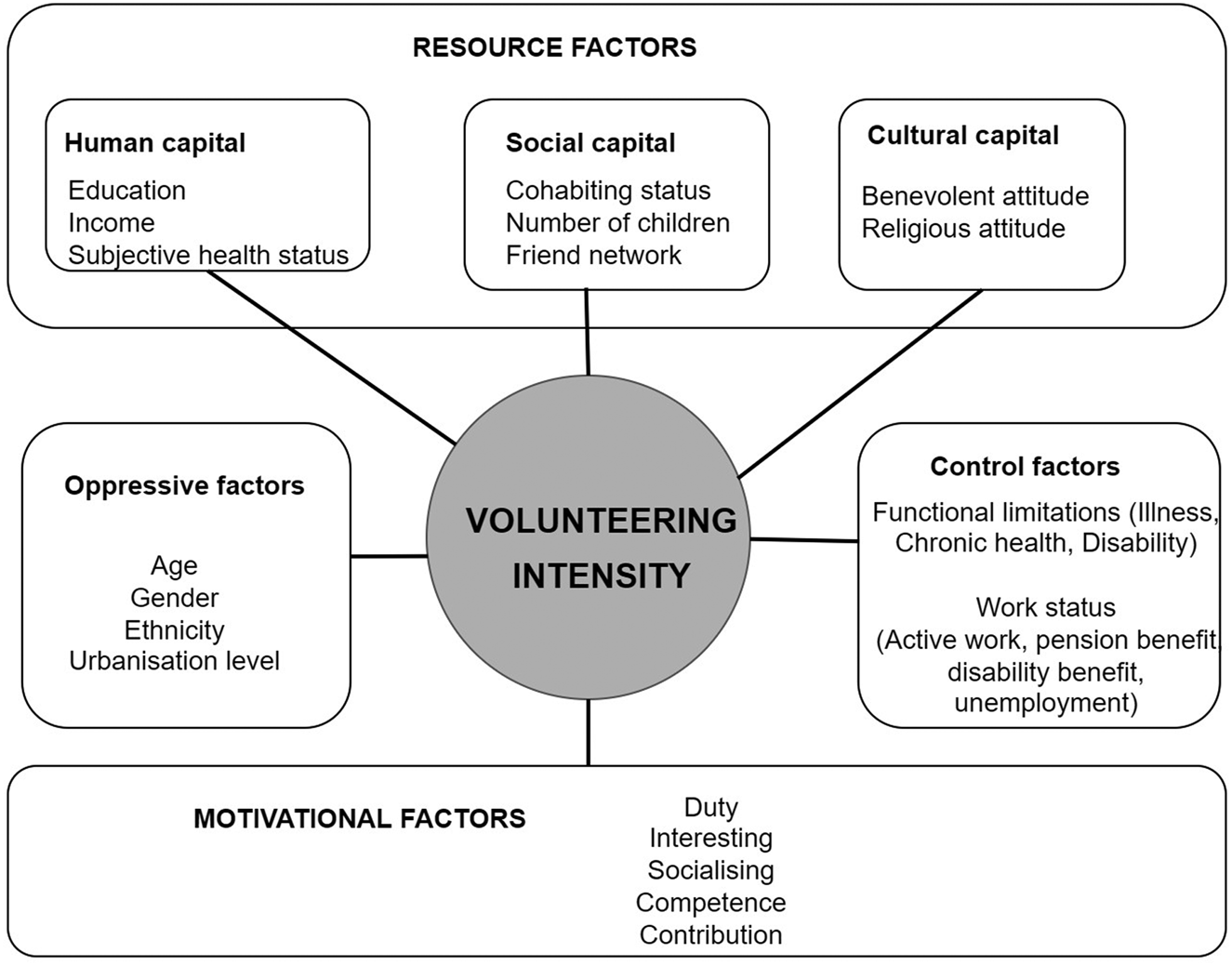

Volunteering is a complex phenomenon and understanding correlates and variation in volunteering intensity requires an integrated theoretical strategy (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010). A combined conceptual framework of the resource theory (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997) and the functional approach to volunteering (Clary and Snyder, Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991, Reference Clary and Snyder1999) that we apply in our study is such an integrated approach aiming at examining different explanations for volunteering intensity. Guided by these theories, we assume that people have a higher intensity of voluntary work if they possess sufficient resources and motivations (see Figure 1). Resource-rich people may find it less challenging to volunteer than resource-poor people because they have more capability and conditions to access and engage in voluntary work. In addition, psychological preferences, needs and goals should be satisfied to facilitate the enthusiasm for volunteering engagement.

Figure 1. Integrated conceptual framework of resource perspective (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997) and the functional approach of volunteering (Clary and Snyder, Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991, Reference Clary and Snyder1999), adjusted for oppressive factors and control factors.

The resource perspective of volunteering derived from Wilson and Musick distinguishes three aspects of voluntary work: ‘a productive activity’ that requires human capital, ‘a collective action’ that requires social capital and ‘an ethically guided work’ that requires cultural capital (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997: 694). Human capital, such as education, health and income, represents resources attached to individuals that make people more qualified for voluntary work and more attractive to voluntary organisations (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997; Forbes and Zampelli, Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014). Social capital refers to the interpersonal relationships illustrated by how many social connections people have, what kind of social connections and how they are organised (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997). The intensity of voluntary work is likely to be higher when people have a substantial stock of social capital since they know more people who can link them and encourage them to do voluntary work. Cultural capital gives people the right information about the voluntary work that fits their attitudes and preferences, such as the culture of benevolence. In general, Musick and Wilson (Reference Musick and Wilson2008: 112–113) highlighted that ‘volunteering is more attractive to the resource-rich than the resource-poor’. One premise of their model is that the more of each capital, the higher the intensity with which people are engaged in voluntary work (Musick and Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2008).

Although the resource perspective of volunteering is meaningful in understanding resource-based factors associated with volunteering, it does not consider the potential importance of motivations for voluntary work. The functional approach of volunteering is a motivation-based approach adopted to apprehend the various motivations to volunteering (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1992; Clary and Snyder, Reference Clary and Snyder1999). Volunteering is motivated by satisfying certain needs and goals, such as the need to meet new people, or the need to learn new things, or improving chances to find a job (Clary and Snyder, Reference Clary and Snyder1999; Finkelstien, Reference Finkelstien2009). The functional approach thus underscores the preference, needs and goals as driving factors of volunteering.

Both approaches, however, have little attention to potential inequalities in voluntary work, despite evidence that people who are in a disadvantaged situation are less likely to volunteer (Southby et al., Reference Southby, South and Bagnall2019). For a better understanding of voluntary intensity, it is thus important to take factors into account that may interconnect to oppress an individual or a group of people. Based on work from Ferrer et al. (Reference Ferrer, Grenier, Brotman and Koehn2017), we therefore also consider factors reflecting categories of difference, such as gender, age and ethnicity. Also, structural factors, such as urbanisation (Hooghe and Botterman, Reference Hooghe and Botterman2012; Dury et al., Reference Dury, Willems, De Witte, De Donder, Buffel and Verté2016; Southby and South, Reference Southby and South2016) may contribute to variations in voluntary work. We include these factors in our analytical models to evaluate whether these are related to voluntary work engagement.

Data and sample

This study uses data from the third wave of NorLAG. NorLAG is a population-based, multi-disciplinary and longitudinal study that includes data on key areas in the second half of life, such as wellbeing, quality of life, health and care, work and retirement, and family relations (Veenstra et al., Reference Veenstra, Herlofson, Aartsen, Hansen, Hellevik, Henriksen, Løset and Vangen2021). NorLAG combines longitudinal survey data with annual data from the public registers from 1967 to 2017. Surveys were held three times (2002/03, 2007/08 and 2017), and data were collected three times by means of computer-assisted telephone interviews with self-administered questionnaires. In the third wave (here referred to as NorLAG3), detailed questions about voluntary work were asked. The register data and survey data were collected with the consent of participants.

The total eligible sample of NorLAG3 was 8,495 people, of which the non-response rate was 31.8 per cent (N = 2,846). The self-administered questionnaire, including detailed questions about volunteering, was filled in by 4,461 persons representing 49.9 per cent of the sample (Veenstra et al., Reference Veenstra, Herlofson, Aartsen, Hansen, Hellevik, Henriksen, Løset and Vangen2021). In this study, we used a subsample of NorLAG3 and included only those that had done any formal voluntary work in the last 12 months. After deleting invalid data, the study sample comprised 1,599 volunteers aged between 50 and 89, with an average age of 64. A slightly higher percentage of volunteers were men (55.1%). Over half of the study participants also participated in the paid labour market (54.8%), 0.8 per cent of the participants were unemployed and around 43 per cent received a pension and/or disability benefit. Most of the respondents are native Norwegians and 7 per cent of participants come from other European countries. Approximately 56 per cent of the respondents live in a large city, 33 per cent live in a town and 11 per cent live in rural areas.

Measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable intensity of voluntary work is a categorical variable based on the question of how much time, in total, people do voluntary work for organisations in one usual week: (1) no time, (2) less than 1 hour, (3) 1–2 hours, (4) 3–4 hours, (5) 5–6 hours, (6) 7–10 hours, and (7) more than 10 hours. Although our dependent variable has an ordinal level, we treat it as an interval variable as the differences between the categories are almost equal, the underlying dimension is an interval variable, the sample is rather large and the variable is normally distributed (skewness = 0.752, kurtosis = 0.244).

Independent variables

Guided by our integrated conceptual framework and within the possibilities of our data, we selected variables representing human capital, social capital, cultural capital, motivations, and potential structural and oppressive factors as our independent variables.

Resources

Three indicators were included to capture human capital, i.e. education, income and subjective health (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997; Tang, Reference Tang2005). Education is categorised into five groups: (1) no or primary education, (2) basic-level high school, (3) higher-level high school, (4) lower-level college and university, and (5) higher-level college and university, and doctoral degree. Income indicates the total income per year after tax of respondents. We recoded all values lower than 10,000 NOK as missing as these are most likely not adequate reflections of the actual income. Subjective health was assessed by asking respondents to evaluate their general health status, with the following options: (1) poor, (2) pretty good, (3) good, (4) very good, and (5) excellent.

Social capital is measured with four indicators and includes both kinship relations and friends. Kinship relations are captured by two indicators, i.e. co-habiting status and the number of children. Co-habiting status is a dichotomous variable with categories (1) not living with a partner and (2) living with a partner. The number of children reflects the total number of children the respondents have. The friend network is captured by two items: (1) apart from your own family, do you have good friends where you live? and (2) do you have good friends in other places? The variable was constructed by taking the arithmetic sum of these two items, subsequently leading to three categories: (1) do not have good friends, (2) having good friends nearby or in other areas, and (3) having good friends both nearby area and in other areas.

Cultural capital is assessed by means of two indicators, i.e. benevolent attitude and religious attitude. A benevolent attitude is a sense of morality, reflecting the protection and promotion of others' interests (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Delston and Wang2017). The benevolent attitude was measured by asking the respondents to indicate how they identified themselves in relation to the following statement: ‘It is important to help and care for others.’ Answering categories are (1) not like me at all, (2) not like me, (3) only a little like me, (4) pretty much like me, (5) like me, and (6) very much like me. For religious attitudes, the respondents were asked whether they consider themselves as being religious. Answering categories are (1) no, (2) yes, little, (3) yes, pretty much, and (4) yes, very much.

Motivations

Five variables were selected to assess the importance of each of the following motivations to do voluntary work: (1) to meet other people (socialising); (2) to contribute something useful (contribution); (3) I think it is fun and interesting (interesting); (4) I can use my competence (competence); and (5) I feel that I have a duty to do so (duty). The respondents indicated the importance of each motivation with a five-point Likert scale: (1) not important, (2) little important, (3) neither important nor unimportant, (4) important, and (5) very important.

Oppressive factors

Gender is a dichotomous variable, coded (1) for men and (2) for women, and age reflects the years lived. Gender and age are included because formal voluntary work can be highly gender-segregated and may be different for various age groups (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Lamura, Principi, Principi, Jensen and Lamura2014; Principi and Perek-Białas, Reference Principi, Perek-Białas, Principi, Jensen and Lamura2014). Ethnicity is measured by the country background of the respondents, categorised into three groups, i.e. Norway, European Union/European Economic Area countries and others. We also include urbanisation as a structural factor that varies within the country. Urbanisation is measured by the level of urbanisation where respondents are living, which was coded (1) as ‘rural’ if the municipality consisted of 1,999 residents or less, (2) as ‘town’ for a municipality with the number of residents between 2,000 and 99,999, and (3) as ‘city’ for a municipality with 100,000 or more residents.

Control variables

The functional limitation variable, measuring whether respondents suffered from illness, chronic health problems or disability is included as a control variable as it may hinder volunteers from committing to voluntary work. Work status may relate to volunteering intensity as people who do not work may have more available time to volunteer (Mutchler et al., Reference Mutchler, Burr and Caro2003). The control variable ‘work status’ was recoded into four dummy variables: (1) active work, (2) pension benefit, (3) disability benefit, and (4) unemployment.

Analytical strategy

Descriptive statistics (number of valid observations, missing values, percentage, mean, range) were used to illustrate the variables' main characteristics. Multivariate linear regression analyses were applied to examine the association between voluntary intensity and the independent variables. To answer the first research question, we examined the association between the dependent variable and resource factors, including indicators of education, income, subjective health, co-habiting status, number of children, friend network, benevolent attitude and religious attitude. To answer the second research question, we added the five motivation indicators discussed before. Age, gender, ethnicity and urbanisation were included in the third model. All variance inflation factor values for variables of interest were smaller than 5, indicating no multicollinearity (Alin, Reference Alin2010; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2014). Data analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 27).

Results

There is substantial variation in the number of hours people do voluntary work. As shown in Table 1, about 15 per cent are inactive as volunteers, one-quarter did less than 1 hour of voluntary work, approximately half of the sample volunteered between 1 and 4 hours, and 15 per cent spent more than 4 hours in one usual week.

Table 1. Descriptive statistic of dependent, independent and oppressive factors and control variables

Notes: N = 1,599. N: number of valid observations. EU/EEA: European Union/European Economic Area.

Most of the respondents have secondary education (45.6%) or university education (45.1%). The average net income was 435,530 NOK per year. One-third of the participants reported that they have chronic health problems or disabilities. About three-quarters of the respondents lived with a partner, and the average number of children was two. Most of the volunteers (86%) reported that they have friends living nearby and in other areas. Most respondents evaluated themselves as having a benevolent attitude. Almost half of the people (47%) have a religious attitude. Most volunteers reported that they are motivated to do voluntary activities that are interesting, provide opportunities for socialising, opportunities to use their competence and to contribute something useful. One-third of the volunteers (32%) are motivated to do voluntary work out of duty.

Table 2 presents the multivariate linear regression results for the intensity of voluntary work regressed on resources, motivations, oppressive factors and control variables. Model 1 included resource variables, motivation variables were added in Model 2, and Model 3 included all resources, motivations, oppressive factors and control variables.

Table 2. Linear regression models for the intensity of voluntary work regressed on resources, motivations and control variables

Notes: N = 1,599. Dependent variable: How much time, in total, you spend on volunteering for an organisation in one usual week? (no time, under 1 hour, 1–2 hours, 3–4 hours, 5–6 hours, 7–10 hours, more than 10 hours). ANOVA: analysis of variance.

Model 1 indicates that of all resource variables, only co-habiting status, number of children and religious attitude significantly contribute to the explanation of the dependent variable (p < 0.05). The volunteers who live with their partners or have more children are likely to have a lower intensity of volunteering (B = −0.218 and B = −0.072, respectively), while volunteers who consider themselves religious are likely to spend more hours per week on voluntary work (B = 0.146). Model 1, including the resource variables, explains 2.4 per cent of the variation in volunteering intensity.

The association between co-habiting status and religious attitude with the dependent variable remains significant after adding the five motivation variables to the model (Model 2), while the number of children lost their significant association. Only two of the five types of motivations that people can have to do voluntary work were significantly associated with time spent on voluntary work: voluntary work is interesting and to use their competence. The association is positive, indicating that volunteers do more voluntary work when they consider that voluntary work is interesting (B = 0.247) and allows them to use their competence (B = 0.114). Adding the motivation variables to the models resulted in a 4 per cent increase in the explained variance.

In Model 3, we further added potential oppressive factors. Urbanisation was not significantly associated with volunteering intensity (p > 0.05), whereas age and gender were significantly associated with the dependent variable, in which men (B = −0.173, p = 0.034) and older people (B = 0.014, p = 0.034) devote more time to voluntary work. Co-habiting status (B = −0.192, p = 0.04), religious attitude (B = 0.116, p = 0.004) and two motivations, ‘interesting’ and ‘competence’ in doing voluntary work, kept their significant association (p < 0.001 and p = 0.004, respectively) with the dependent variable after adding oppressive factors and control variables. The result indicated higher voluntary intensity associated with not living with partner/spouse and a religious attitude. Our study also finds that volunteers who are motivated to volunteer because it is fun and interesting and because they can use their competence and skills spend a higher amount of time on voluntary work. The full model explained 10.6 per cent of the total variation in volunteering intensity.

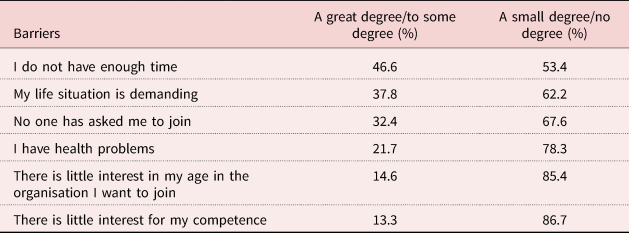

As indicated, our information on oppressive factors that may be associated with the intensity of volunteering is limited, but we do have some information about what people perceive as barriers to volunteering (Table 3). While this may be biased as people are not always aware of social oppression, analysing these reasons may corroborate our findings about oppressive factors. The important reasons that people who wished to be more active gave were lack of time (46.6%) and a too demanding life situation (37.8%). Ten to 20 per cent of the volunteers mentioned health problems, lack of interest from the voluntary organisations because of their age and lack of interest in their competence.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics reporting barriers towards volunteering commitment

Note: N = 1,599.

Discussion

Guided by the resource perspective of Wilson and Musick (Reference Wilson and Musick1997) and the functional approach of Clary and Snyder (Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991, Reference Clary and Snyder1999), this study aims to examine associations between resources and motivations and the intensity of volunteering among Norwegian people aged 50 years and older. We further examined associations between urbanisation, age, gender, ethnicity and controlled for functional limitations and work status. Overall, our study suggests that individual resources and motivations, as well as oppressive factors, help to understand variations in the intensity with which people do voluntary work. Having a religious attitude and doing voluntary work that fits people's interests and competencies associated with an elevated volunteering commitment, while living with partners may decrease the time investment in voluntary work. Higher education, higher income, better subjective health, higher number of children, friend networks and benevolent attitude are not associated with the amount of volunteering time. As a result, our study is only partly in line with the theory of Wilson and Musick (Reference Wilson and Musick1997) that voluntary work is more attractive to people who have more resources. Our results are, however, in line with previous empirical studies finding that a religious attitude stimulates spending more time on volunteering (Choi, Reference Choi2003; Tang, Reference Tang2008; Dury et al., Reference Dury, De Donder, De Witte, Buffel, Jacquet and Verté2015), but in contrast with some findings (Wollebæk et al., Reference Wollebæk, Sætrang and Fladmoe2015; Folkestad and Langhelle, Reference Folkestad and Langhelle2016) that having a partner, friends or other social contacts stimulate volunteering. A plausible explanation for this result may be that although social ties may give more opportunities to access the information to start voluntary work, they may also limit the volunteer's engagement if there are time conflicts between spending time with family and doing voluntary work. This is what the majority of the volunteers also mention when asked about reasons for not spending more time on voluntary work despite their wishes.

As for the association between motivational factors and voluntary work intensity, our results indicated that older volunteers do more voluntary work if the work is interesting and requires their competencies. Only two out of the five motivations for voluntary work that were asked are associated with volunteering intensity, suggesting that our results only partly support the functional approach of Clary and Snyder (Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991, Reference Clary and Snyder1999). While most previous literature reported that volunteers might be mainly motivated by a sense of altruism, a sense of mission and social contacts (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Proenca and Proenca2009), our study reveals these motives are not major factors of time spent on voluntary work. We did not find that urbanisation or ethnicity are related to the intensity of voluntary work, whereas age and gender are associated with volunteering intensity. The finding that men have a higher intensity of voluntary work than women is consistent with the current finding that Norwegian men have a higher likelihood of volunteering engagement than women (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). Although our finding suggests that older volunteers are likely to spend more time volunteering, when asking people about reasons for not spending more hours on voluntary work despite their wish to do so, approximately 15 per cent of them report that they feel excluded based on their age. There is no evidence that work status or functional limitations hinder the intensity with which older adults participate in voluntary work in our study. However, around one-fifth of older volunteers in our study reported that their health problems might prevent them from investing more volunteering hours. Although our result indicates that the relevance between volunteers' competence and skills with voluntary work is important to volunteers, our respondents think that there is a lack of interest in their competence in voluntary organisations. Therefore, one should acknowledge that older volunteers may perceive that their age, health conditions and competencies may prevent them from doing more volunteering hours.

The present study has some practical implications for voluntary organisations. If voluntary organisations are interested in increasing the potential of older volunteers, they can think of recruiting and retaining volunteers who can contribute more hours to voluntary work (Randle and Dolnicar, Reference Randle and Dolnicar2009), or stimulate volunteers to invest more of their time. Concerning the latter, voluntary organisations may want to make sure that there is a good match between the type of voluntary work and the resources, preferences and competence of the volunteers. Second, in designing interventions to increase the time invested in voluntary work, organisations should acknowledge potential barriers. Our study suggests that co-habitation and lacking sufficient time or time conflicts between the time spent with family and doing voluntary work may hamper people from contributing more hours to voluntary work. Therefore, a more flexible volunteer schedule allowing people to choose their suitable time and place for voluntary work may help to increase the possibilities of volunteering. Volunteering from home, in particular, may provide flexible and tailored-made solutions to the particular needs and circumstances of volunteers and may facilitate an optimal balance between family duties and volunteering commitment. In addition, voluntary organisations should pay attention to the volunteers' perception of their age and health conditions as barriers to becoming (more) active in voluntary work.

Limitations of study and suggestions for further studies

Although our study provides further insight into the intensity of formal volunteering, several limitations should be considered. One limitation is that motivations for volunteering have been collected at one point in time (the last round, 2017), which does not allow conclusions on the direction of effects. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the causal relationships between resources, motivations and volunteering. This study further suggests that a conceptual framework combining the resource perspective and functional approach of volunteering is a fruitful approach to understanding the intensity of voluntary work among older adults. The explained variance from our results is rather small (around 10%), suggesting that there are other factors not included in this study that explain variability in volunteering intensity. Future studies could also use various indicators to capture the resources, motivations and structural factors that our study has not examined. As there are very few people with a minority background in our study sample, we could not examine the various ethnic groups in Norway. Our results are based on data from Norway with the characteristic of a strong welfare state policy, characterised by high social security benefits and financial security, that may not apply to other countries with different cultural and economic conditions. To validate the value of this integrated approach to volunteering in other countries, data from other countries are needed.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first that used a theoretical framework that combined the resource perspective (objective approach), functional approach (subjective approach) and oppressive factors to examine factors associated with time spent on volunteering in later life. Our study contributes to the debates about older volunteering in that both resources and the right motivations enhance the likelihood of volunteering engagement among older adults. There is no sign of structural barriers that may affect voluntary engagement in our study. Older men in Norway invest more hours in voluntary work than older women, and the amount of time invested increases with age. Increasing time investment in volunteering should focus on an optimal fit between volunteer tasks and the available time resource, suitable knowledge and skills, and preference of volunteers. Flexibility in working schedules could be further promoted.

Acknowledgement

This paper uses data from NorLAG Wave 3. The NorLAG data collections have been financed by The Research Council of Norway, four ministries, The Norwegian Directorate of Health, The Norwegian State Housing Bank, Statistics Norway and The Norwegian Social Research (NOVA), OsloMet. NorLAG data are part of the ACCESS Life Course infrastructure funded by the National Financing Initiative for Research Infrastructure at the Research Council of Norway (grant numbers 195403 and 269920).

Author contributions

GHL and MA together conceived the idea of the paper. MA helped to access the NorLAG data and suggested the theoretical framework. GHL reviewed the literature, conducted the analyses and drafted the manuscript. MA supervised the methods, consulted in analysing and interpreting the data, and commented on the paper drafts. Both authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This paper has followed the major ethical considerations under the guidance of the Norwegian Data Protection Authority. The authors have assessed NorLAG data with permission of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) after signing a pledge of secrecy.