This chapter considers the role of economic information in generating political inequality across income groups. Income inequality across many advanced democracies has risen sharply over the last four decades (Lupu and Pontusson, this volume). Not only have market incomes become increasingly concentrated among the very rich in a wide range of national contexts; so, too, have posttax-and-transfer incomes. In other words, many elected governments, notwithstanding the formidable range of market-shaping and redistributive policy instruments at their disposal, have over an extended period of time allowed a narrow and extremely affluent segment of the population to reap a further outsized share of the fruits of economic growth. How has this happened? What has allowed inequalities in material resources to mount in political systems that, nominally, distribute votes equally across adult citizens? Why have basic mechanisms of electoral accountability not induced governments to pursue economic and social policies that better serve the distributional interests of the vast majority of the electorate?

While scholars have identified a wide range of causes of political inequality in advanced democracies (many of them the focus of other chapters of this volume), our focus is on an examination of a key informational prism through which voters learn about the state of the economy: the news media. A vast literature points to the strong influence of citizens’ evaluations of the economy on their votes (e.g., Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis-Beck Reference Lewis-Beck1988). Meanwhile, a substantial body of evidence highlights the powerful role that the news media play in informing citizens’ economic evaluations (Blood and Phillips Reference Blood and Phillips1995; De Boef and Kellstedt Reference De Boef and Kellstedt2004; Boydstun, Highton, and Linn Reference Boydstun, Highton and Linn2018; Garz and Martin Reference Garz and Martin2021; Goidel et al. Reference Goidel, Procopio, Terrell and Denis Wu2010; Hollanders and Vliegenthart Reference Hollanders and Vliegenthart2011; Mutz Reference Mutz1992; Nadeau, Niemi, and Amato Reference Nadeau, Niemi and Amato1999).

Building on our own prior work on the United States (Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Scott Matthews, Hicks and Merkley2021) and presenting a set of new cross-national analyses, we investigate how journalistic depictions of the economy relate to real distributional developments. In particular, we ask: when the news media report “good” or “bad” economic news, whose material welfare are they capturing? How does the positivity and negativity of the economic news track income gains and losses at different points along the income spectrum?

Using sentiment analysis of vast troves of economic news content from a broad set of advanced democracies (drawing on data from Kayser and Peress Reference Kayser and Peress2021), we demonstrate that the evaluative content of the economic news strongly and disproportionately tracks the fortunes of the very rich. Although we observe somewhat more news responsiveness to the welfare of the middle class in this cross-national sample than we did in our earlier US study, the pro-rich skew in economic news observed in other advanced democracies is highly comparable to that found in the United States. To the extent that economic news shapes citizens’ economic evaluations and that evaluations of the economy shape votes, we thus have in hand at least a partial potential explanation of why mechanisms of electoral accountability have failed to deliver more equal economic outcomes.

And yet the finding of class-biased economic news raises one further puzzle: why does economic news content appear to overrespond to gains and losses for the rich? We review a range of potential explanations drawn from the existing media studies literature, most of which posit a set of interests or preferences among news owners, producers, sources, or consumers that lead inexorably to a pro-rich bias in economic reporting.

We then propose an alternative account, arguing that pro-rich biases in news tone could arise from routines of economic reporting in which journalists aim to capture the performance of the economy in the aggregate while paying minimal attention to distributive matters. In this model, the class bias in news content need not arise from a set of pro-rich interests within the news sector, but from the workings of the economy itself: from the fact that, in most capitalist democracies, aggregate expansion and contraction over the last forty years have been positively and disproportionately correlated with the rise and fall, respectively, of the incomes of the very rich. Thus, a news media that seeks merely to cover the ups and downs of the business cycle will generate news that, implicitly, tracks the fortunes of the most affluent. Voters will tend to read “good” economic news in those periods when inequality is rising and “bad” economic news as disparities shrink. We test key predictions of this theory on a large sample of news content from a broad range of OECD contexts, finding that movements in GDP growth, unemployment, and share valuations explain most of the association between news tone and relative gains for the very rich. In addition, we show that pro-rich bias in the economic news is relatively uniform across outlets with varying partisan slants, suggesting that these biases arise at least in part from sources other than journalists’ or owners’ economic preferences.

In sum, the analyses that we present in this chapter suggest that the democratic politics of inequality may be shaped in important ways by the skewed nature of the informational environment within which citizens form economic evaluations. Moreover, this informational skew appears to be in part a product of the underlying structure of the economy itself. In an economy that distributed aggregate economic gains relatively equally, journalists and voters alike could fairly well assess the changing welfare of the typical household simply by following the ups and downs of the business cycle. In a political economy that generates systematically biased distributions of the fruits of growth, however, the informational demands of our normative model of democratic accountability are steeper, and there is reason to worry that the news media are not currently meeting those demands.

The Economic-Inequality Puzzle

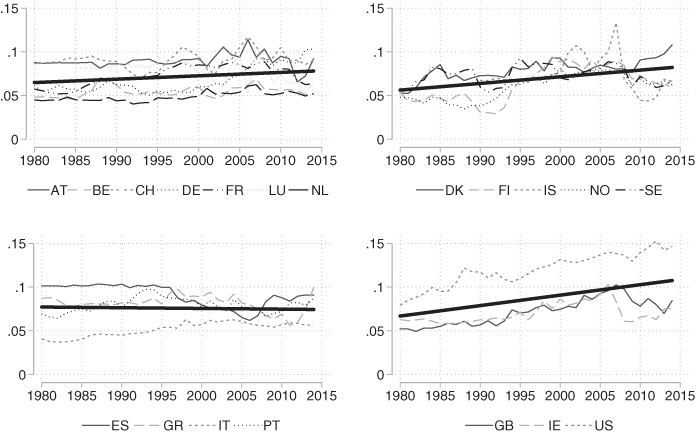

A substantial share of advanced democracies has witnessed rising inequality in posttax-and-transfer income over the last four decades. We illustrate the pattern in Figure 11.1, where we plot change over time (1980–2014) in the posttax-and-transfer income share of the richest 1 percent of individuals for nineteen advanced democracies, grouping countries approximately by welfare-state-regime type (see “Data” for information on data sources). We see that top-income shares, after taxes and transfers, have risen considerably across most of these countries: most steeply in countries with liberal welfare states; somewhat less so, but still markedly in social democracies; and more modestly but nontrivially in continental, corporatist settings. In Southern Europe, we see top-income shares holding about steady over this period (see also Lupu and Pontusson, this volume).

Figure 11.1 Posttax-and-transfer income share of the top 1 percent of individuals for nineteen advanced democracies

Note: Thick black lines are overtime trends based on pooled OLS regressions.

Governments in these nations have had opportunities to shape the allocation of households’ consumption possibilities at multiple stages. A range of “predistributive” policies can influence the allocation of income derived from labor and capital, while tax rules and social welfare systems can, and to varying degrees do, compensate for market-driven disparities. Given the powerful tools at the state’s disposal for influencing final distributional outcomes, those countries in which disposable income (and wealth) have become increasingly concentrated among the very rich represent a puzzle: how have political systems that are nominally governed under the principle of political equality failed to generate more egalitarian outcomes?

Explanations for rising postgovernment inequality (or, similarly, for the incompleteness of compensatory redistribution) abound, and many are considered in this volume. We can distinguish between two broad lines of explanation. One such line emphasizes political inequality, or differentials in influence wielded by the rich and the nonrich: the nonrich might want more equal outcomes, but their demands lose out in the political sphere to those of the most affluent (e.g., Giger, Rosset, and Bernauer Reference Giger, Rosset and Bernauer2012; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2011, Reference Hacker and Pierson2020; Peters and Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015; Bartels, this volume; Mathisen et al., this volume).

A second line of explanation focuses on the “demand side” of the political dynamic and, in particular, on the attitudes and political behavior of the nonrich.Footnote 1 We can usefully think of demand-side research on the politics of inequality as coming in two varieties. A majority of demand-side scholarship has focused on citizens’ policy preferences, such as their level of support for redistribution (e.g., Cavaillé, this volume; Cavaillé and Trump 2015; Cramer, this volume; Fong Reference Fong2001; Kenworthy and McCall Reference Kenworthy and McCall2007; Lupu and Pontusson Reference Lupu and Pontusson2011). If we aim to explain elected governments’ distributional policy choices, then citizens’ attitudes toward those policy choices is a perfectly reasonable place to start.

At the end of the day, however, incumbents in a democracy who wish to remain in office must win elections, a goal that may depend only weakly on their distributive policies. Voters typically lack strong preferences on all but the most salient policy controversies (Converse Reference Converse2006, Reference Converse and Apter1964; Tesler Reference Tesler2015) and, in the absence of specific views, may be inclined to adopt the positions of candidates who are favored for reasons unrelated to their policy commitments (Lenz Reference Lenz2012; but see Matthews Reference Matthews2019). When distributional issues do meaningfully influence vote choice, furthermore, that influence may be swamped by other considerations.

On the other hand, among the best-established regularities uncovered in decades of research on electoral behavior is that voters’ choices are strongly influenced by economic outcomes, or, at least, by voters’ assessments of those outcomes (e.g., Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis-Beck Reference Lewis-Beck1988). A second line of demand-side inquiry has begun to examine how economic voting interacts with the politics of distribution, asking how electorates respond to different distributions of economic gains and losses. This line of research is motivated by a baseline, normative notion of how economic voting might work: we might in principle expect nonrich members of the electorate to defend their economic interests at the ballot box by voting out governments that oversee patterns of (income) growth that concentrate gains at the very top and rewarding incumbents that spread gains broadly. Even in the absence of conscious demands for redistribution, electoral dynamics should serve as a brake on rising material inequality if citizens cast their economic votes in distributionally sensitive ways, in ways that align in some way with their income stratum’s distributional economic interests. Do they?

The answers we have so far suggest that electorates respond to distributional outcomes in a manner directly at odds with this normative model. Not only do nonrich voters appear not to vote their distributional interests, but patterns of economic voting may play a substantial role in incentivizing governments to concentrate economic gains at the top. Studying presidential elections from 1952 to 2012, Bartels (Reference Bartels2016) finds that incumbent parties in the United States perform better in election years with higher rates of income growth at the 95th percentile, conditional on mean income growth. In other words, for any given level of per capita income growth, incumbent parties receive an electoral premium when a higher share of that growth flows to the family at the 95th income percentile. At the same time, the US presidential electorate as a whole appears unresponsive to mean income growth after taking into account income growth at the top. Moreover, and most puzzlingly, this broad pattern – which Bartels (Reference Bartels2016) terms “class-biased economic voting” – holds specifically for voters in the bottom third and in the middle third of the income distribution. Lower-income voters appear to respond favorably to top-income growth conditional on mean growth, but not at all to mean growth conditional on top-end growth. And while middle-income voters show some responsiveness to mean income growth, they are about twice as responsive to top-income growth.

In an extension of Bartels’ work, we find clear evidence of the operation of class-biased economic voting in a broader comparative context (Hicks, Jacobs, and Matthews Reference Hicks, Jacobs and Scott Matthews2016). Analyzing individual-level election-study data, for instance, we find that lower- and middle-income voters in Sweden and the United Kingdom vote for the incumbent party at higher rates as income growth for the richest 5 percent rises for any given level of mean growth, and appear unmoved by income growth for the bottom 95 percent.Footnote 2 Further, analysis of aggregate election data for 200 postwar elections across fifteen OECD countries reveals a substantial average reward to the incumbent party for overseeing rising income shares for the top 5 percent. And, as in the United States, OECD electorates on average fail to reward governing parties for the portion of mean income growth that does not flow to the top.

In short, what we know about the relationship between distributional dynamics and electoral patterns suggests a serious empirical problem with a normative model in which voters defend their (income groups’) economic interests at the ballot box. What we seem to be seeing is not the absence of economic voting but a distributionally perverse form of it. The observed patterns suggest the operation of one or more mechanisms that do more than prevent citizens from casting economic votes in distributionally sensitive ways; they seem to turn distributional self-interest on its head.

In the remainder of this chapter, we focus on a mechanism that plausibly intervenes in critical ways between the economy and voter evaluations: the news media. A substantial body of evidence highlights the powerful role that the news media plays in informing citizens’ economic evaluations (Blood and Phillips Reference Blood and Phillips1995; Boydstun, Highton, and Linn Reference Boydstun, Highton and Linn2018; De Boef and Kellstedt Reference De Boef and Kellstedt2004; Garz and Martin Reference Garz and Martin2021; Goidel et al. Reference Goidel, Procopio, Terrell and Denis Wu2010; Hollanders and Vliegenthart Reference Hollanders and Vliegenthart2011; Mutz Reference Mutz1992; Nadeau, Niemi, and Amato Reference Nadeau, Niemi and Amato1999). A key question, then, is how economic news coverage itself relates to objective distributional dynamics in the economy. If the economic news disproportionately reflects the economic experiences of the very rich, then nonrich voters will be operating in an informational environment that is, in an important sense, systematically skewed against their own material interests. In the section that follows, we consider reasons why the economic news in advanced capitalist democracies might tend to be biased in favor of the interests of the most affluent.

Potential Preference- or Interest-Based Sources of Class-Biased Economic News

It is not difficult to imagine reasons why major news outlets might cover the economy in ways that favor the interests of the rich. One possible source of such bias might be the general economic interests of media owners. Since the owners of news outlets tend to be either large corporations or very rich families (Grisold and Preston Reference Grisold and Preston2020; Herman and Chomsky Reference Herman and Chomsky1994), they share an interest in rising concentrations of income and wealth at the top. Moreover, news outlets depend on revenue from advertisers, who themselves may have an interest in policies that promote or permit higher inequality. To the extent that owners and advertisers can influence content, the result may be economic coverage that systematically favors the interests of wealthy households and corporations (for a formalization, see Petrova Reference Petrova2008; though see also Bailard Reference Bailard2016; Gilens and Hertzman Reference Gilens and Hertzman2000: 371).

A further potential source of class bias in economic reporting might arise from the upper-middle-class composition and elite educational background of most members of the journalism profession (e.g., Gans Reference Gans2004, 124–138; Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit Reference Weaver, Willnat and Cleveland Wilhoit2019). Journalists’ interpretation of economic events may be shaped directly by their class interests, and their involvement in upper-middle-class social networks might shape the kind of information about the economy to which they are exposed and, in turn, their beliefs about which economic topics are newsworthy.

On a related note, bias in economic-news content might derive from the skewed perspective of the sources on whom journalists routinely rely when reporting on the economy. As numerous studies have documented, economic reporters looking for commentary and analysis tend to turn disproportionately to elites with close ties to the business community and finance (Call et al. Reference Call, Emett, Maksymov and Sharp2018; Davis Reference Davis2002, Reference Davis, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018; Knowles Reference Knowles, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018; Knowles, Phillips, and Lidberg Reference Knowles, Phillips and Lidberg2017; Wren-Lewis Reference Wren-Lewis, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018). Dependence on economic-elite and corporate sources might tend to generate coverage that systematically privileges the interests of firms, financial institutions, and investors and that is skeptical of state intervention to redress inequality.

Independently of owners’, reporters’, or sources’ interests and outlooks, readers of economic news may themselves tend to be more affluent than the general population (Davis Reference Davis, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018) and prefer content that reflects their material interests. Gentzkow and Shapiro (Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2010) find suggestive evidence of the effects of audience partisanship on editorial content in the United States, while Beckers et al. (Reference Beckers, Walgrave, Valerie Wolf, Lamot and Van Aelst2021) find that Belgian journalists overestimate the conservatism of the general public, a perception that might dampen any focus on inequality and boost attentiveness to outcomes aligned with the interests of the rich.

A further possibility is that, in many OECD contexts since the 1970s, economic reporting as a whole has been influenced by a general, rightward ideological shift in the political sphere, especially the ascendance of free-market ideas (Davis Reference Davis, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018; DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio2017; Schifferes and Knowles Reference Schifferes, Knowles, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018). Cutting against this view, however, is evidence that journalistic opinion (e.g., Rothman and Lichter Reference Rothman and Robert Lichter1985) and use of sources (Groseclose and Milyo Reference Groseclose and Milyo2005) reflect a left-wing bias (though see Nyhan Reference Nyhan2012) and findings of considerable ideological variation in news outlets’ economic content (Arrese Reference Arrese, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018; Barnes and Hicks Reference Barnes and Hicks2018; Larcinese, Puglisi, and Snyder Reference Larcinese, Puglisi and Snyder2011).

A Theory of News Bias Independent of Preferences: Covering the Business Cycle

While the material interests and ideological preferences of those who produce, inform, or consume the news might all serve to skew journalistic portrayals of the economy, we will argue that a pro-rich tilt in the economic news can readily emerge from a process in which news outlets seek to do nothing more than faithfully report on the aggregate state of the economy – depending on how the economy itself operates. If journalists seek to assess overall economic performance but economic growth itself is associated with greater relative gains for the rich, then media evaluations of the economy will tend to most closely track the welfare of the rich, even in the absence of pro-rich preferences among media actors themselves.

To be clear, the argument that follows is not a case against the view that ideological or interest-based biases shape economic news coverage. What we seek to elucidate in this section is how features of the economy itself, together with a set of facially neutral journalistic operating routines, could themselves be sufficient to generate bias before the worldviews or class interests of news producers even enter into the equation.Footnote 3

A Focus on Economic Aggregates

We begin by positing the operation among journalists of an understanding – a “mental model” – of the economy that treats the promotion of aggregate expansion as the central, if not exclusive, objective of economic management. In his classic study of American newsrooms, Gans (Reference Gans2004) finds that “responsible capitalism” is among the core values of American journalism and that, in economic reporting, “[e]conomic growth is always a positive phenomenon” (p. 46). Thomas’ (Reference Thomas, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018) analysis of British TV news during the postfinancial-crisis recovery similarly finds that economic growth was depicted as an unalloyed good, while Davis (Reference Davis, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018) reports that British economic reporting largely “focuses on a series of headline macroeconomic indicators,” including GDP growth and unemployment (p. 165). “Good” and “bad” economic news, then, are defined by developments that signal or reflect an upturn or a downturn, respectively, in the business cycle – especially in output and its close correlate, employment.

In this framework, moreover, distributional questions as such are generally not salient, on the assumption that the benefits of economic growth are typically broadly distributed, with rampant rent-seeking by economically privileged actors rare. As Gans writes of TV news in the United States, journalists display “an optimistic faith that in the good society, businessmen and [business]women will compete with each other in order to create prosperity for all, but that they will refrain from unreasonable profits and gross exploitation of workers or customers.” Along just these lines, in their study of coverage of the Bush tax cuts in the United States, Bell and Entman (Reference Bell and Entman2011) find that news stories emphasized their potential effects on growth, while neglecting their likely impact on inequality.

Aggregate Growth and Distribution

How might a journalistic focus on economic aggregates generate a class bias in economic news? In principle, it need not. Where economic gains and losses were equally distributed, a journalistic focus on the business cycle would generate news that is equally sensitive to the fortunes of all income groups. However, that will cease to be the case in any context in which aggregate income growth is systematically skewed in favor of the most affluent. In particular, if economic growth, its drivers, or its presumed proxies (such as corporate performance) tend to generate higher concentrations of income at the top, then journalists who “cover the business cycle” will, without necessarily intending to, generate portraits of the economy that systematically and disproportionately track the fortunes of the rich.

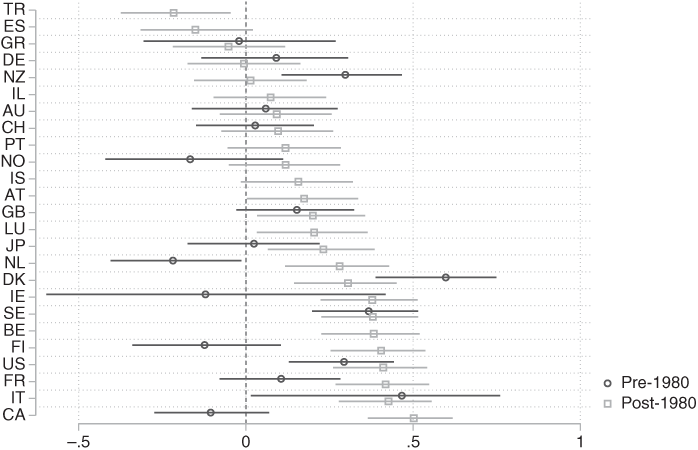

In Figure 11.2, we plot the post-1980 correlation between the annual rate of GDP growth and annual change in top-1 percent pretax income shares for a broad set of countries, with the pre-1980 correlation plotted where data are available (see “Data” for information on data sources). As we can see, since 1980, there is clear evidence of cyclicality of top-income shares in more than half of the countries in this sample. Put differently, it is incomes at the top that most closely track the business cycle: that grow fastest during periods of aggregate growth and fall most rapidly in recessions. We also note that the group of countries featuring cyclical inequality represents a wide range of political economies, from liberal market economies like Britain, the United States, and Canada to most of the coordinated market economies of Scandinavia. While pre-1980 data are missing for some countries, we also see considerable evidence, on balance, of increasing cyclicality over time.

Figure 11.2 Correlation between the annual rate of GDP growth and annual change in top-1-percent pretax income shares for a broad set of countries, before and after 1980

Notes: Quarterly observations. Pre-1980 observations unavailable for certain countries.

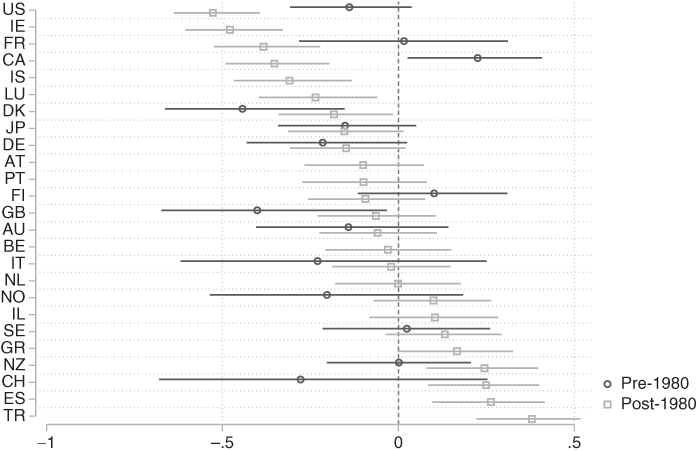

In Figure 11.3, we turn to another oft-reported economic aggregate, the unemployment rate. The figure plots the correlation of annual change in the unemployment rate with annual change in top pretax income shares for all advanced democracies for which consistent data were available, pre- and post-1980. While unemployment is commonly understood to weaken the bargaining power of labor vis-à-vis capital, we see that change in the unemployment rate has more often been negatively correlated with income concentration at the top, meaning that years with falling unemployment have tended to be years of growing top-income shares – or in which top incomes grow faster than incomes of the nonrich. This is, again, the case for a diverse set of political economies, including the United States, Denmark, and France.Footnote 4

Figure 11.3 Correlation between the annual change in the unemployment rate and annual change in top-1-percent pretax income shares for a broad set of countries, before and after 1980

Notes: Quarterly observations. Pre-1980 observations unavailable for certain countries.

Why do the incomes of the rich tend to grow faster than incomes of the nonrich during economic booms and fall faster during recessions? While we do not seek to unravel this piece of the puzzle in this chapter, we can point to a few possible suspects: reasons why the forces driving economic growth might simultaneously drive greater inequality. Several studies point to changes in the distribution of demand for skills driven by trade and technical change that might generate relatively faster growth (decline) in top incomes as overall output and employment expand (contract). Focusing on the United States, Cutler et al. (Reference Cutler, Katz, Card and Hall1991) argue that, during the recovery of the 1980s, while employment rose – a phenomenon that, on its own, would have benefited lower-paid workers – this aggregate development was overwhelmed by an increase in relative demand for higher-skilled labor, generating a net increase in wage dispersion and income inequality. In broader theoretical work, Aghion, Caroli, and García-Peñalosa (Reference Aghion, Caroli and García-Peñalosa1999) contend that technological change, especially the spread of general-purpose technologies, has become a key driver of both economic growth and earnings inequality by creating a growing skill premium, particularly as the supply of higher-end skills fails to keep pace with demand (see also Goldin and Katz Reference Goldin and Katz2009; Parker and Vissing-Jorgensen Reference Parker and Vissing-Jorgensen2010). Factors such as the increasing financialization of OECD economies (Lin and Tomaskovic-Devey Reference Lin and Tomaskovic-Devey2013) and the decline of labor unions in many advanced economies (Volscho and Kelly Reference Volscho and Kelly2012) may play a similar role, simultaneously driving higher rates of economic growth and higher concentrations of income at the top. And, of course, the same forces might not explain the observed correlations across political economies as different as the liberal United States and social democratic Denmark.

Whatever the underlying economic mechanisms, however, we can see that the share of income going to the most affluent has in recent decades been closely tied to key economic aggregates across a broad swathe of advanced democracies. The implication for the economic news is striking: the tone of news focused on economic aggregates, like growth and unemployment, will be characterized by a bias toward the interests of the very rich – even without any conscious intention, on journalists’ part, to deliver a skewed portrait of the economy. To the extent that growth and income inequality arise from a common source, “good” economic times – understood in aggregate terms – will tend to be accompanied by rising concentrations of income at the top. We should, on this logic, expect economic news focused on the business cycle to more closely track the incomes of the very rich than the incomes of the nonrich, and we should expect the news to become more positive as income inequality – understood as an income skew toward the top – rises. Given the steep concentration of company shareholding among the very rich, economic assessments tied to corporate or stock market performance will likewise be disproportionately correlated with welfare at the top of the income scale.

This argument (if true) would not imply that class-biased economic news emerges apolitically or via the ineluctable operation of market forces. In the United States, for instance, there is strong reason to believe that political choices in areas such as trade, education, labor relations, and taxation have played a substantial role in tying growth and inequality more closely together in recent decades (see, e.g., Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2011). Moreover, one could understand a journalistic focus on economic aggregates at the expense of distributional dynamics as itself ideological in nature – as a “blind spot” underwritten by a political worldview or material interests. Our claim, however, is that class-biased economic reporting itself need not involve any deliberate effort by reporters to overattend to the interests of the rich. Given the underlying distributional biases in the broader political economy, the emergence of class-biased news merely requires that journalists cheer the economy on during periods of aggregate growth and lament its decline in aggregate downturns.

Why would class-biased economic news matter for the politics of inequality? Recall that voters’ choices are shaped to a substantial degree by sociotropic assessments of the economy and that those assessments are influenced by signals from the news media. If economic reporting is driven overwhelmingly by changes in economic aggregates, and the incomes of the nonrich are less closely correlated with aggregate growth than are the incomes of the rich, then the signals received by nonrich voters in many OECD contexts will most closely track the fortunes of the rich. The implication is not just that nonrich voters’ economic assessments are less likely to capture welfare changes among the nonrich. It is also that nonrich voters are, on average, taking in more favorable assessments of economic performance at precisely those times when inequality is increasing – and less favorable signals as inequality is falling. To the extent that the economic vote is shaped by the news media, then, journalism that covers the business cycle – in a context in which the fruits of growth are concentrated at the top – will tend to generate an electoral environment favorable to rising income disparities between the rich and the rest.Footnote 5

Empirical Predictions

We can summarize our core argument with this simple causal graph:

where X denotes a set of inequality-inducing drivers of growth and employment (e.g., trade, skill-biased technological change, financialization, union decline). In this model, the drivers of growth simultaneously generate aggregate expansion and higher inequality (i.e., higher income shares for the very rich). Economic aggregates, in turn, drive the positivity of economic news, resulting in a positive correlation between inequality and news tone. Importantly, inequality itself has no causal effect on news tone in this model, and class-biased economic news does not emerge from a journalistic response to inequality. Rather, class-biased news arises here from media actors placing a positive value on features of the economy that are systematically correlated with rising inequality, owing to common causes of these features of the economy and rising inequality.

Part of the analysis that follows is focused on the descriptive question of whether class bias is operating: whether the news tracks gains and losses for different income groups in a manner that is disproportionately sensitive to the welfare of the rich. In addition, we examine a number of empirical implications of our theorized causal mechanism. Specifically: (1) News tone should be positively correlated with inequality. (2) News tone should be correlated positively with GDP growth and negatively with unemployment rates. (3) A final prediction – one more specific to the aggregate-centered-journalism explanation for class-biased economic news – is that any correlation between inequality and news tone should be weaker conditional on the macroeconomic aggregates than it is unconditionally. In the language of Pearl (Reference Pearl2009), conditioning on the macroeconomic aggregates should, under this causal model, “block” the path running between news tone and inequality, eliminating any correlation between the two that arises from this path (while potentially preserving other sources of correlation not captured in the model).

Further, in their efforts to find indicators of the performance of the overall economy, journalists may be expected to devote special attention to the health of the corporate sector – with corporate performance itself an important driver of inequality:

Under this argument, (4) corporate performance should be correlated with news tone, and (5) controlling for corporate performance should reduce the size of the correlation between top-end inequality and news tone, since conditioning on corporate performance blocks a path connecting these two variables.

Empirical Evidence of Class-Biased Economic News

We now consider empirical evidence on both the presence of class-biased economic news in advanced democracies and the mechanisms driving it. A growing literature, drawing on increasingly sophisticated data collection and measurement techniques, has examined how the economic news – usually captured by the positivity and negativity of the tone of coverage – responds to changes in the real economy. This has included analysis of the sensitivity of the news to levels and changes of various economic parameters, such as growth, unemployment, and inflation, over different time horizons (Kayser and Peress Reference Kayser and Peress2021; Soroka Reference Soroka2006, Reference Soroka2012; Soroka, Stecula, and Wlezien Reference Soroka, Stecula and Wlezien2015). There has been little analysis to date, however, of whose material welfare the economic news reflects or of whether and how the news captures the distribution of aggregate economic gains and losses.

The media studies literature has yielded significant qualitative evidence, derived from close readings of modest corpora of news content, of how journalists represent distributional issues. On the whole, these studies suggest that news coverage of economic issues generates a discursive environment that is not merely unfavorable to proequality policies, but also favorable to policies that might aggravate existing material disparities. For instance, in the US context, Bell and Entman (Reference Bell and Entman2011), drawing on a qualitative assessment of television news coverage of the highly regressive Bush tax cuts, argue that reporting created an informational environment favorable to their passage. Kendall (Reference Kendall2011), analyzing the frames used in US newspapers to describe people of different classes, finds more sympathetic portrayals of the affluent, even when engaged in wrongdoing, than of the working class and the poor. Schifferes and Knowles (Reference Schifferes, Knowles, Basu, Schifferes and Knowles2018), in a qualitative content analysis of British economic commentary on austerity in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, find that it overwhelmingly legitimized austerity measures and devoted little attention to its impacts on poverty or household income. Grisold and Preston (Reference Grisold and Preston2020), in a four-country study of newspaper coverage of the debate unleashed by Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-first Century, report that while inequality is largely represented as a problem, there remains a strong focus on inequality’s quasi-automatic causes (e.g., technology, globalization) at the expense of its political sources. They also find that journalists tend to emphasize the goals of meritocracy and equality of opportunity over that of equality of material outcomes; characterize growth as beneficial for all; and depict redistributionist policies in unfavorable terms. Further, they identify important silences in coverage, including an absence of attention to the failure of earnings to keep pace with productivity growth and to the adverse consequences of inequality.

While these studies shed light on the substantive frames and considerations shaping news coverage, they are unable to speak to broader systematic patterns in news responsiveness. In particular, they cannot tell us how news coverage of the economy on the whole relates to real developments in the distribution of resources. Studies that systematically examine the relationship between a large corpus of news content and objective material-distributional conditions have been sparse and mixed in their findings. Kollmeyer (Reference Kollmeyer2004) analyzes a modest sample of Los Angeles Times articles from the late 1990s and finds that negative economic news focused disproportionately on difficulties faced by corporations and investors as compared to those faced by workers, at a time when corporate profits in California were skyrocketing relative to wages. On the other hand, taking a longer time period and examining a European setting, Schröder and Vietze (Reference Schröder and Vietze2015) analyze postwar coverage of inequality, social justice, and poverty in three leading German news outlets, finding that coverage of these topics rises with inequality itself.

In the remainder of this section, we present analyses that relate the tone of large corpora of economic news content over extended periods of time to real distributional dynamics in the economy across a substantial set of OECD economies. These analyses build on those reported in Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Scott Matthews, Hicks and Merkley2021), where we examine biases in the economic news in the United States. In that study, drawing on an original dataset of sentiment-coded economic news content from thirty-two large-circulation US newspapers, we uncover a set of descriptive relationships strongly consistent with the operation of a pro-rich bias in the economic news as well as evidence consistent with the empirical predictions of the “covering the aggregates” mechanism. However, the US political economy and media environment are different from those of other OECD nations in many highly consequential ways; relationships uncovered in the United States tell us little on their own about whether class-biased economic reporting is a widespread or general phenomenon in advanced capitalist democracies. Our aim in the remainder of this chapter is thus to ask whether we find similar patterns – in regard to both the descriptive question of whether class bias is operating and the causal question of why – across a broader set of OECD countries. To do so, we bring together a massive new cross-national, time-series dataset of economic news tone from Kayser and Peress (Reference Kayser and Peress2021) and data on the distribution of income from the World Inequality Database.

Data

The dependent variable in all analyses – the tone of the national economic news – derives from Kayser and Peress’s (Reference Kayser and Peress2021) cross-national, time-series dataset. Based on a sample of roughly 2 million newspaper articles about the economy, this dataset provides monthly readings of economic news tone – the degree of positivity or negativity of sentiment in economic news articlesFootnote 6 – for sixteen countries for the period 1977–2014 (coverage windows vary by country; see Table 11.A1 in the Appendix). Complete details regarding data collection can be found in Kayser and Peress (Reference Kayser and Peress2021: 7–12). For our purposes, two critical features of the Kayser and Peress (KP) dataset are worth noting.

First, the data were collected with the aim of studying, among other things, whether media with different ideological leanings portray economic developments differently: whether left-wing outlets report more positively on the economy when a left-wing government is in power, and whether the reverse holds for right-wing outlets under right-wing governments. A key element of the data structure, accordingly, is that tone is observed in two media outlets in each country: one left-wing and one right-wing newspaper. The data consist, thus, of thirty-two time series (16 countries × 2 newspapers per country) of monthly economic-tone observations.Footnote 7

Second, as in Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Scott Matthews, Hicks and Merkley2021), the KP dataset utilizes a dictionary-based approach to the coding of economic sentiment. Kayser and Peress translated their English-language sentiment dictionaries into five additional languages (French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian), allowing them to code equivalent measures of economic news tone for multiple countries. The KP dataset contains separate news tone measures concerning coverage of “the economy in general, growth, unemployment and inflation” (p. 12). Our analysis relies solely on the first of these measures. The tone measures are based on coding of the tone (positive or negative) of individual sentence fragments containing terms denoting relevant economic concepts. In turn, these fragment-level tone scores are aggregated by month, such that the monthly tone score is given by the ratio of positive fragments to all positive/negative fragments. This approach normalizes the measure for monthly variation in the volume of economic news.

To the KP dataset, we add measures of growth in pretax and disposable incomes and income shares at different points in the income distribution derived from the World Inequality Database (WID). These measures allow us to replicate in the cross-national sample precisely the same descriptive analyses estimated with US data in Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Scott Matthews, Hicks and Merkley2021). We rely exclusively on WID measures for the population of individuals over twenty years of age, assuming income is distributed equally among household members (e.g., for average pretax income of the top 5 percent, the variable name is aptinc992j_p95p100). We are also able to use the KP dataset to search for evidence of the possible mechanisms of class-biased economic news, examining the empirical predictions set out in the preceding section. For measures of GDP growth and the unemployment rate, we rely on the indicators included in the KP dataset, which combine data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the International Monetary Fund. In addition, we capture corporate performance using a measure of the market capitalization of listed domestic companies as a percentage of GDP, obtained from the World Development Indicators dataset (variable name: mkt_capitalization).

As noted, the KP dataset consists of monthly observations. To align with the analysis in Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Scott Matthews, Hicks and Merkley2021), we collapse these data to the quarterly level, taking the mean value for each variable within quarters. For economic variables that we observe only annually (such as income growth for income groups), we use linear interpolation to produce monthly values (prior to collapsing the data to quarters). All income-growth variables record twelve-month growth as a percentage. Income share variables are twelve-month first-differences in the proportion of income captured by a particular group. GDP growth is observed quarterly. Finally, we take first differences by month in the unemployment rate and capture monthly percentage growth in market capitalization (again, collapsing these by quarter in the analysis).

Descriptive Patterns across Countries

We start by asking the descriptive question of whether the economic news differentially captures the changing fortunes of individuals in different income groups. We do so by estimating, in different model specifications, the relationship between news tone and income growth at various points along the income distribution. Because our theoretical logic operates via market dynamics, we focus our analysis on the relationship between news tone and changes in market incomes,Footnote 8 but we show toward the end of this subsection that the pattern is remarkably similar when we instead examine changes in disposable income.

Given the spatial and temporal structure of our data, simply pooling the observations and estimating the relationships of interest by OLS would not be appropriate, as this requires implausible assumptions regarding the independence of observations over time and across the panels (i.e., the thirty-two newspapers). Accordingly, throughout this section and the next, we estimate dynamic models of economic tone that incorporate newspaper-specific fixed effects and time trends, quarter-of-year fixed effects, and four lags of the dependent variable. Our goal is to model the “nuisance” variance within our data, in the form of temporal trends and autocorrelations, so that our remaining inferences regarding the associations between news tone and changes in the economy are credible. More precisely, we estimate the following regression model:

where ![]() is economic news tone for newspaper

is economic news tone for newspaper ![]() at time

at time ![]() , the

, the ![]() are newspaper fixed effects, the

are newspaper fixed effects, the ![]() are newspaper-specific time trends,

are newspaper-specific time trends, ![]() is a time counter,

is a time counter, ![]() are quarterly dummies, and

are quarterly dummies, and ![]() is a set of income quantiles that varies by model. We also allow a newspaper-specific AR1 process in the errors and estimate panel-corrected standard errors.Footnote 9

is a set of income quantiles that varies by model. We also allow a newspaper-specific AR1 process in the errors and estimate panel-corrected standard errors.Footnote 9

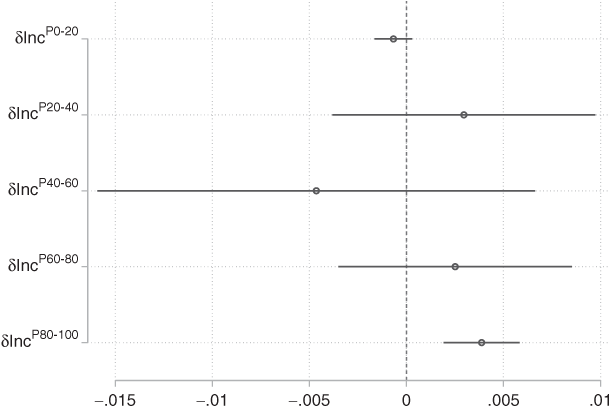

First, dividing each country’s population into income quintiles, we ask how the tone of the economic news relates to income growth for each quintile, conditional on income growth in all of the other quintiles. We display, in Figure 11.4, estimates of these associations across the sixteen countries, revealing that growth in the top quintile is significantly associated with economic tone. The estimate implies that, in this cross-national sample, a standard deviation increase in the average income of the top 20 percent is associated with an increase in the positivity of economic news of 0.13 standard deviation units. There is no sign that income growth in any other quintile is associated with the tone of economic news, as the relevant coefficients cannot be reliably distinguished from zero. The top-20 percent coefficient is also significantly larger than the first- (p = 0.02) and fourth-quintile (p = 0.02) coefficients.

Figure 11.4 Association between economic news tone and pretax income growth for each income quintile, conditional on income growth for all other quintiles

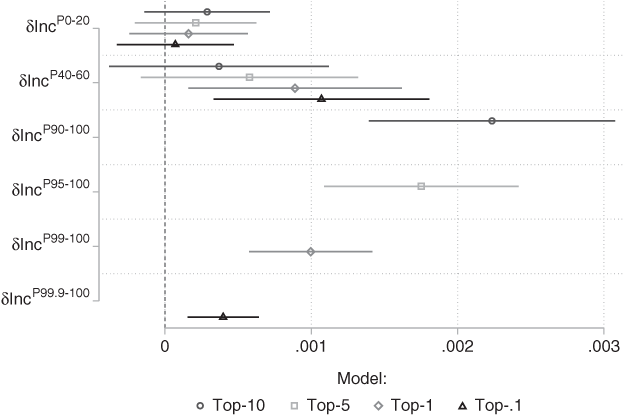

We next turn to the association between economic news tone and income growth within progressively narrower slices of the very top of the income distribution. We include, in separate models, measures for the top 10 percent, 5 percent, 1 percent, and 0.1 percent of income earners. As regards income growth at the top, the results, presented in Figure 11.5, suggest that the fortunes of highly affluent subgroups of the population are significantly associated with economic tone in the cross-national sample. A standard deviation increase in income growth among the top 10 percent of earners, for example, is associated with an increase in the positivity of economic tone of 0.11 standard deviations. Equivalent shifts among the top 5 percent, top 1 percent, and top 0.1 percent are associated with increases in economic tone of 0.10, 0.08, and 0.05 standard deviations, respectively. The comparison between the top 10 percent and top 0.1 percent in the magnitude of these associations bears emphasis: whereas the top 10 percent group is 100 times the size of the top 0.1 percent group, the magnitude of the former’s association with tone is just over double that of the latter. Notwithstanding the sizable correlation between these two income-growth variables (![]() ), the results suggest that an outsize share of the association between top 10 percent growth and economic tone reflects the association between tone and a tiny sliver of earners at the very top of the income distribution.

), the results suggest that an outsize share of the association between top 10 percent growth and economic tone reflects the association between tone and a tiny sliver of earners at the very top of the income distribution.

Figure 11.5 Association between economic news tone and pretax income growth for top-income groups, controlling for bottom- and middle-income growth

A notable difference between Figure 11.5 and the US results, reported in Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Scott Matthews, Hicks and Merkley2021, Figure 11.3), concerns associations between economic tone and income growth in the middle of the distribution. In the United States, there is no sign whatsoever that change in the fortunes of any group below the very top is associated (conditional on income changes at the top) with the positivity of economic news. In the cross-national sample, however, there is evidence that growth in the third quintile is related to economic news sentiment. In models that include the top 1 percent or top 0.1 percent of income earners (diamonds or triangles in Figure 11.5), who have been so central in popular discourse on economic inequality, growth in incomes at the middle is significantly associated with economic tone. Specifically, in the top-1 percent model, a standard deviation increase in growth at the middle of the income distribution is associated with a 0.04 standard deviation increase in tone, while the same increase in the top-0.1 percent model is associated with a tone shift of 0.05 standard deviations. The important substantive implication is that, when we look beyond the United States, there is some evidence that coverage of the economy is, on average, somewhat reflective of the experiences of a broad swath of the population.

Nevertheless, the estimates depicted in Figure 11.5 also imply that there is still a very substantial class bias in economic news in the cross-national sample. For instance, focusing on the top-1 percent model, recall the 0.08 standard deviation shift in tone associated with a standard deviation increase in income growth in this top-income group – an association that is double the estimate for the middle quintile (in the top-1 percent model), even as the latter income group is twenty times larger than the former.

We now evaluate these patterns more formally by constructing a test for the presence of pro-rich bias in the tone of the economic news. This test takes into account the fact that the income groups we are comparing are comprised of different numbers of individuals, with (for instance) the bottom 20 percent being comprised of twenty times more people than the top 1 percent. We define unbiasedness according to the normative principle that every individual’s welfare should weigh equally in representations of the nation’s welfare. On this “representational equality” principle, the absence of pro-rich bias would require that the correlation between, for instance, bottom-quintile income growth and news tone be twenty times larger than the correlation between top-1 percent income growth and news tone. Under this logic, inferences about biasedness must derive from the ratios of relevant coefficients, rather than the raw coefficients themselves.

On this basis, we estimate models that allow us to assess the degree of descriptive pro-rich bias in news tone. The core specification that we adopt here contains income-growth rates for three income groups: the bottom 20 percent, the top X percent, and the broad middle from the 20th percentile to the lower threshold of the top-X percent group – where we estimate models with X ∈ {10, 5, 1, 0.1} to assess the robustness of the inferences to progressively narrower conceptions of top income.

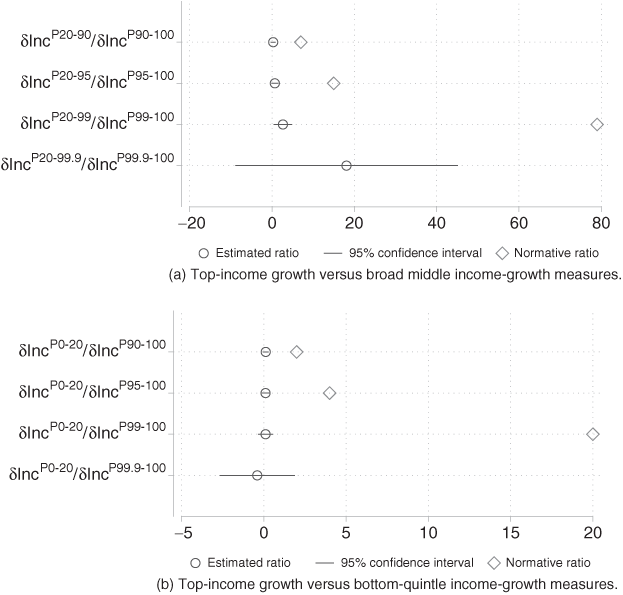

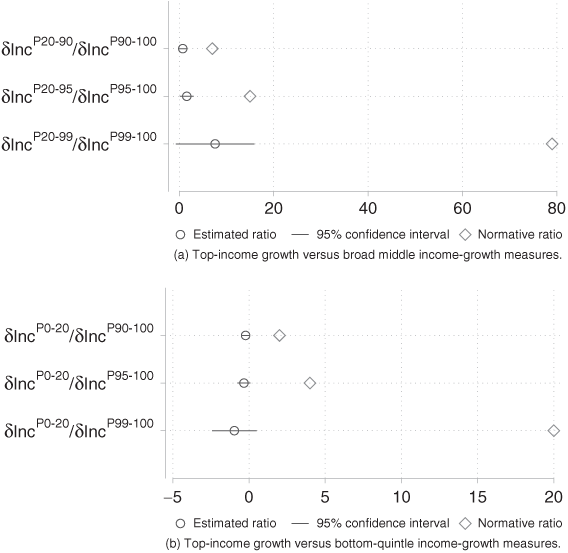

We separately present results for a comparison of the broad middle to the top (Figure 11.6a) and for a comparison of the bottom to the top (Figure 11.6b). For the former, for each top-income measure, the circle represents the estimated ratio of news tone’s association with income growth in the broad middle to news tone’s association with income growth for the top-income group. We see that, in Figure 11.6a, the ratio of tone’s association with middle-income growth to tone’s association with top-income growth is statistically indistinguishable from zero for all but the comparison with top-1 percent income growth. Meanwhile, the diamonds represent the group-size-based normative baseline of unbiasedness for each top-income measure. We do not plot the diamonds for the top-0.1 percent models because these values (799 for the middle-top comparison and 200 for the bottom-top comparison) would be located so far to the right that the x-axis scales would be too large to clearly read off the inferences for the other top-income groups.

Figure 11.6 Estimated coefficient ratios from models predicting economic news tone with pretax income growth for different parts of the income distribution

Notes: Each row in each panel represents a ratio between the news-tone/income-growth correlation for a top-income group to the news-tone/income-growth correlation for a nonrich group. The diamond represents a normative baseline ratio for each comparison, derived from relative population sizes and the principle of equal per capita weighting. The circle (with 95 percent confidence interval) represents, for each comparison, the actual estimated ratio between the two tone-growth correlations. Confidence intervals not apparent where they are smaller than the radius of the dot representing the point estimate.

To illustrate how one would read this graph, consider the third row in Figure 11.6a, which plots the comparison between the top 1 percent (p99–100) and the income group that lies between the 20th and 99th percentiles (p20–99). The diamond represents the normative baseline for this comparison. If every individual’s economic welfare received equal weighting in the news media’s depiction of each nation’s economic welfare, then the correlation between news tone and income growth for the p20–99 group should be seventy-nine times the size of the correlation between news tone and income growth for the p99–100 group – since the population of the former group is seventy-nine times as large as that of the latter. The plotted circle on this same row represents the actual estimated ratio between these two correlations and the 95 percent confidence interval around that estimate for our sixteen countries. As can be seen here, the estimated ratio is a tiny fraction of that normative baseline, indicating that the association between news tone and income growth for the p20–99 group is dramatically smaller than that for tone and income growth of the top 1 percent, once we adjust for the differing sizes of the groups. Figure 11.6b is read in the same way, but with the nonrich comparison group always being the bottom 20 percent, rather than the broad middle.

The core message of Figure 11.6a is that, across all four top-income measures, the estimated ratios are much lower than the normative baseline: in other words, news tone’s association with top-income growth is far stronger, relative to that with middle-income growth, than would be expected on the basis of an equal weighting of the welfare of individuals across the income distribution. As the confidence intervals indicate, the inferences in this regard are extremely clear. Figure 11.6b displays, with respect to the bottom-top comparison, a remarkably similar pattern of stark overrepresentation of the welfare of the very rich in the tone of the economic news.Footnote 10

We have so far analyzed tone-income growth relationships for market incomes, but we might wonder whether government intervention changes the picture. To address this question, we undertake precisely the same set of analyses we have presented for pretax incomes, but now substitute measures of growth in disposable income for the pretax indicators. Note that, in doing so, we lose five countries for which disposable income estimates are not available (Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand), which together comprise over 40 percent of our observations.

Figure 11.7, which plots associations between news tone and disposable income growth by quintile, yields the same inference as the counterpart figure for pretax incomes: there is a significant positive association between tone and income growth in the top quintile, and only extremely weak evidence of such an association for any other quintile. The estimates indicate that a standard deviation increase in the rate of income growth in the top quintile is associated with a 0.18 standard deviation increase in the tone of economic news.

Figure 11.7 Association between economic news tone and disposable income growth for each income quintile, conditional on income growth for all other quintiles

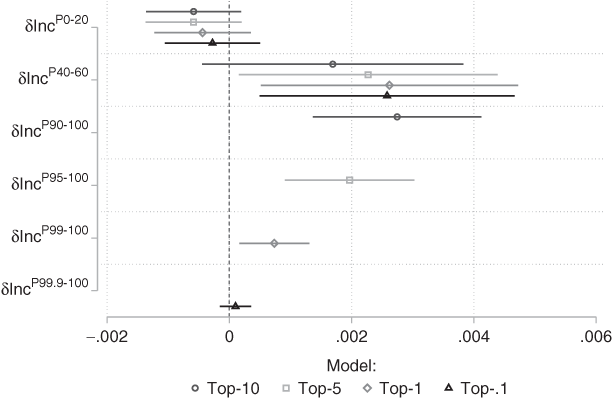

Figure 11.8 captures relationships between economic tone and narrow slices at the top of the income distribution and is the disposable income counterpart to Figure 11.5. Again, the inferences are largely similar. Economic tone is positively associated with disposable income growth for the top 10 percent, top 5 percent, and top 1 percent of income earners; only among the top 0.1 percent does the association fall from statistical significance. A standard-deviation increase in disposable income growth among the top 10 percent, top 5 percent, and top 1 percent is associated with increases in the positivity of economic tone of 0.15, 0.12, and 0.07 standard deviations, respectively. As in the pretax estimates, tone is also positively associated with income growth in the middle quintile, except in the model including top 10 percent income growth. Depending on the model, a standard deviation increase in the rate of income growth in the middle quintile is associated with economic tone increases of between 0.10 and 0.11 standard deviations.

Figure 11.8 Association between economic news tone and disposable income growth for top-income groups, controlling for bottom- and middle-income growth

Finally, Figure 11.9 returns to our formal test for class-biased economic news. Figure 11.9 is exactly parallel to Figure 11.6, but uses disposable income growth instead of pretax income growth. As in Figure 11.6, we are comparing the ratios of growth-tone coefficients for different group pairings against a normative standard of representational equality. By this standard, it will be recalled, coefficient magnitudes should be in proportion to group sizes – that is, for instance, the coefficient for income growth in the bottom quintile should be twenty times that of the top 1 percent (see further discussion earlier). In each row, the diamond represents the normative baseline ratio of the growth-tone correlation for the top-income group to the growth-tone correlation for the middle (11.9a) or bottom (11.9b) income group. So, for instance, we see that for the comparison of the p20–95 group to the p95–100 group, we would normatively expect news tone’s correlation with the former group’s welfare to be about fifteen times as large as its correlation with the latter group’s welfare. The circle in this row represents the estimated actual ratio between these two growth-tone correlations. As we can see, the estimated ratio is much smaller than the normative baseline ratio, indicating that the correlation of news tone with the welfare of the p20–95 group is in a per capita sense (our normative baseline), dramatically smaller than news tone’s correlation with the welfare of the top 5 percent. Note that we omit comparisons involving the top 0.1 percent: as the coefficients for this group are very imprecisely estimated, the wide confidence intervals for the corresponding ratios have a distorting effect on the plot.

Figure 11.9 Estimated coefficient ratios from models predicting economic news tone with disposable income growth for different parts of the income distribution

Notes: Each row in each panel represents a ratio between the news-tone/income-growth correlation for a top-income group to the news-tone/income-growth correlation for a nonrich group. The diamond represents a normative baseline ratio for each comparison, derived from relative population sizes and the principle of equal per capita weighting. The circle (with 95 percent confidence interval) represents, for each comparison, the actual estimated ratio between the two tone-growth correlations. Confidence intervals not apparent where they are smaller than the radius of the dot representing the point estimate.

In short, as with the pretax income estimates, the estimated ratios uniformly diverge from the normative standard of equality. Figure 11.9a shows that the association between disposable income growth and economic tone is much stronger – sometimes many times stronger – for top-income groups than for the broad middle of the income distribution. Figure 11.9b tells a substantively equivalent story for the comparison of top- to bottom-income group coefficients, with the notable qualification that the estimated ratios are actually negative. This pattern reflects the fact that the coefficients for the bottom quintile, while statistically insignificant, are in fact less than zero. In any case, the implication is the same: relative to lower income groups, improvements in the welfare of those at the very top are vastly better reflected in the tone of economic news.

To summarize, our analysis of associations between economic tone and income growth measured at different points in the income distribution reveal a pattern of class-biased economic news across a broad sample of advanced democracies. In Tables 11.A7 and 11.A8 in the Appendix, we show that the comparative results are virtually unaffected by excluding the United States from the analysis. Having said that, there is one notable way in which the United States stands out. Contrary to our earlier US results, we do find some evidence in the cross-national sample of associations between economic tone and income growth below the very top. However, the below-the-top associations are still substantially smaller than those at the top when considered relative to the size of the income groups concerned.

Mechanisms of Class-Biased Economic News in the OECD

We next go looking for evidence of the mechanisms that might explain this normatively troubling descriptive bias in the relationship between economic news tone and distribution. We begin by asking whether and how much of the observed bias can be explained by our central argument: that is, by the media’s tendency to cover economic aggregates, which are themselves positively correlated with top-end inequality.

To shed light on this question, we take advantage, as noted earlier, of time-series data on economic aggregates (measures of GDP growth and the unemployment rate) for each country in the KP dataset. To these measures, we add the measure of market capitalization growth obtained from the World Development Indicators. We focus our analysis on the five empirical implications of the covering-the-aggregates argument, outlined earlier. For these tests, we return to using pretax incomes since our proposed mechanism speaks primarily to the relationship between economic aggregates and the market income of the very rich, whether earnings or capital income. We estimate models of the form described earlier, though now we include additional variables – principally, economic aggregates – relevant to our theory.

Estimates for the variables of interest are reported in Table 11.1. We start with a baseline estimate of the correlation between economic news tone and income inequality. If, as we showed in the preceding section, economic news sentiment is relatively more strongly associated with growth in the incomes of the most affluent, then it follows that a change in the share of income captured by the most affluent – here, the top 1 percent of income earners – should be positively associated with economic tone (Prediction 1). The estimates for Model 1 confirm this expectation.

Table 11.1 Mechanisms of class-biased economic news

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8329*** | 0.4735** | 0.6666*** | 0.6137** | 0.3052 | 0.8367*** | |

| (0.2087) | (0.1826) | (0.1891) | (0.2058) | (0.1846) | (0.2086) | |

| 0.0382*** | 0.0261*** | |||||

| (0.0043) | (0.0038) | |||||

| −0.0738*** | −0.0529*** | |||||

| (0.0107) | (0.0102) | |||||

| 0.0039*** | 0.0032*** | |||||

| (0.0007) | (0.0006) | |||||

| 0.0852 | ||||||

| (0.0839) | ||||||

| Constant | 0.1463*** | 0.1429*** | 0.1563*** | 0.1186*** | 0.1284*** | 0.1466*** |

| (0.0281) | (0.0260) | (0.0265) | (0.0268) | (0.0245) | (0.0281) | |

| Observations | 2061 | 2061 | 2061 | 1947 | 1947 | 2061 |

Standard errors in parentheses. Regressions include quarterly and newspaper-fixed effects, newspaper trends, and 4 lags of economic tone, with panel-corrected standard errors.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

In Models 2 and 3, we consider whether economic aggregates, specifically, GDP growth and change in the unemployment rate, drive the tone of economic news (Prediction 2) and also account, via their correlations with income inequality, for some part of the correlation between inequality and economic tone (Prediction 3). The former expectation is strongly supported in these models: Model 2 shows that GDP growth is positively related to economic tone, while Model 3 indicates that change in the unemployment rate is negatively related to tone. Both coefficients are statistically significant at the 99.9-percent level.

Critically, there is also clear evidence that part of the association between inequality and economic tone reflects correlations between inequality and these two economic aggregates. When GDP growth is controlled for, the association between economic tone and change in the income share of the top 1 percent is sliced by more than two-fifths (Prediction 3). Controlling for change in unemployment has a similar, if more modest, effect: the coefficient on top 1 percent income share change is reduced by one fifth (Prediction 3).

Model 4 addresses the specific role of corporate performance in the covering-the-business-cycle process. We see here that growth in market capitalization is positively related to positive economic tone (Prediction 4). We also see that controlling for this variable reduces the association between economic tone and top 1 percent income share change by more than a quarter (Prediction 5).

Model 5 captures the combined effect of GDP growth, unemployment rate change, and market capitalization growth on the association between economic tone and income inequality. Notably, while the associations between the three growth-related variables shrink in this setup, each variable retains a sizable and statistically significant association with economic tone, which reflects the modest correlations between these variables in the cross-national sample.Footnote 11 Most importantly, from the perspective of the covering-the-business-cycle theory, the inclusion of these variables in the same model shrinks the top 1 percent income share change coefficient by almost two-thirds, rendering it statistically insignificant.

Overall, looking across the estimates of Models 1–5, one finds substantial support for the argument that the class bias in economic news across OECD countries reflects journalists’ focus on economic aggregates in reporting on economies in which inequality itself is cyclical. Moreover, we show in Table 11.A9 in the Appendix that the results of these mechanism tests are broadly the same when the United States is excluded from the sample.

Last, we leverage Kayser and Peress’ coding of the ideological leanings of newspapers to speak to alternative mechanisms. If class-biased economic news reflects the class-biased interests or worldviews of news producers or consumers, then class bias in the tone of economic news should be stronger in those outlets that present a more conservative worldview in general. Model 6 thus adds an interaction between top 1 percent income share change and newspaper ideology. The interaction between inequality and ideology is not statistically significant: the tone of the news in left-wing newspapers is as strongly associated with inequality as is economic news tone in right-wing newspapers. Of course, it is possible to imagine ideological or interest-based mechanisms that might operate for left- as well as right-wing outlets (e.g., even the former are likely to be owned by members of the richest 1 percent and rely on corporate advertising). Yet the lack of any detectable difference should cast at least some doubt on the notion that class biases derive in any straightforward way from media actors’ ideological commitments.Footnote 12

Conclusion

Our aim in this chapter has been to suggest that there is something worth puzzling over in the relationship between economic news and income distribution in advanced democracies. The analysis that we present here naturally has its limits. In seeking to characterize national media environments, we have drawn on data from only two newspapers per country, and our sample is limited both in the number of countries and the time period covered. Yet we think the evidence in this chapter constitutes at least a prima facie case that economic reporting by leading news outlets in a wide range of advanced democracies aligns relatively poorly with the economic experiences and distributional interests of the nonrich. We hope that other scholars will seek to test this proposition with more data drawn from a wider set of national contexts.

Among the questions that we have not addressed here is what might explain the variation in patterns of class-biased reporting across countries. Table 11.A1 in the Appendix suggests considerable differences in the presence and strength of pro-rich biases in economic news across the OECD contexts in our sample. Some of this variation may be mere “noise,” given the small number of available observations for some countries. At the same time, these results may, in fact, understate the variation across the OECD, insofar as Nordic social democracies are not captured in the KP data.

What might explain the cross-national variation in class-biased economic reporting? We suggest a few possibilities in the spirit of hypothesis generation. One conjecture that flows directly, and almost mechanically, from our theoretical argument is that settings in which economic growth and contraction are less strongly (and positively) correlated with top-income shares should see less-biased economic news coverage. We would expect a range of factors – from labor-market rules and institutions to the tax treatment of executive compensation to the degree of financialization of the economy – to condition the link between inequality and the business cycle. Variation in the underlying structure of the political economy should, in turn, generate variation in the pro-rich bias of the economic news. That said, Table 11.A1 does not suggest any straightforward pattern, given the considerable variation across countries typically considered to have broadly similar political economies (e.g., Ireland vs. other liberal countries; Germany and France vs. Austria).

We might also imagine variation in the norms and routines that shape the production of news content itself. In characterizing the performance of the economy, journalists might attend more to the distribution of gains and losses in contexts that otherwise make distribution more salient. These might include, for instance, contexts in which inequality is especially high, in which parties on the Left place distributional matters prominently on the agenda, or in which party competition is strongly configured around a distributional dimension of conflict.

We would also emphasize that our analyses by no means settle the question of whether or how the ideology and interests of news producers and consumers shape economic reporting. The news outlets in our sample may represent too little variation in ideological leanings or economic worldviews to pick up the effect of these factors. As we have also noted, a journalistic focus on the business cycle might itself reflect a set of widespread ideological presumptions about the benefits of growth or satisfaction with a set of measures that in fact do a good job of capturing the welfare of the most affluent. Unpacking these possibilities will likely require, in part, the collection of individual-level data tapping media owners’ and journalists’ economic attitudes and worldviews.

Finally, we point out some complexity in making normative sense of our findings. While periods of economic growth see rising concentrations of income at the top, they also tend to be the periods in which most groups experience absolute income gains. One might, therefore, ask whether it is such a bad thing if the nonrich receive favorable signals about economic performance in periods in which they are gaining in absolute terms, even if they are losing in relative terms. Indeed, news tone has a positive, statistically significant (p < 0.05) bivariate relationship (i.e., without controls for other income quintiles) with disposable income growth for all but the first and second income quintiles in the countries in our sample (see Figure 11.A1 in the Appendix). This pattern suggests that the economic news might tend to correctly signal the direction of welfare change for most income groups. This fact, however, does not seem to us to dispose of the normative problem. For one thing, news tone appears to provide no meaningful signal about how the economy has performed for the bottom 20 percent of the income scale; and, more generally, Figure A1 suggests that news tone provides a less-informative signal as we move down the income distribution. More importantly, accepting the signaling of absolute gains as normatively sufficient would commit us to the view that information about distribution is effectively irrelevant for the formation of citizen assessments of economic performance. We see no clear reason to believe that nonrich citizens with full information would be indifferent to the distribution of aggregate gains and losses.Footnote 13

We also note that these patterns – news tone’s positive correlation with both inequality and absolute income gains for middle-income groups – may shed light on the economic and political resilience of advanced capitalist democracies, as examined by Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2019). In Iversen and Soskice’s view, postwar democracy and advanced capitalism have operated in a symbiotic relationship, as democratic governments have made economic policy choices in response to voter demands for effective economic management, delivering both prosperity and democratic legitimacy. At the same time, as we have shown in Figure 11.1, that growth has in most countries disproportionately benefited the very rich. Our analysis of the informational environment might help explain how incumbents have won support for prosperity-generating policies that exacerbate inequality: as they evaluate governments’ economic management, the middle classes receive media signals that track the rise in aggregate prosperity and the absolute gains experienced by their own income groups but are insensitive to the distribution of those gains. Economic reporting that systematically attended to distribution – perhaps applying a “tone penalty” to less-equal allocations – might well heighten the contradictions embedded in advanced capitalist democracy.