1. Introduction

In Donald Davidson's Triangulation Argument (henceforth DDTA), Robert Myers and Claudine Verheggen advance important novel interpretations of central aspects of Davidson's later thought centering around an interpretation of the role of triangulation in Davidson's philosophy in fixing the contents of thoughts. The book is divided into two parts. The first is authored by Verheggen and concentrates on the triangulation argument and its epistemic and metaphysical implications. The second is authored by Myers and focuses on extending the argument to normative attitudes to arrive at the conclusion that we share objective values. It was a real pleasure to read this superbly written, philosophically subtle, and ingenious book, to revisit these familiar themes in Davidson's work and see them in a fresh light, and to do it in the company of old friends who know Davidson's work as well as anyone. There is a lot that I agree with in the book about what Davidson is up to and which, with Verheggen and Myers, I think many other interpreters have got wrong. But, as usual in these contexts, I focus not our agreement but on places where I still have some doubts — some of philosophical substance and some of interpretation. I hope, in the spirit of Davidson, the extent to which we agree will help clarify the differences in a philosophically useful way.

I focus on two important moments in the argument of the book. The first is the defence of a reconceptualized triangulation argument in which the two roles that triangulation plays in Davidson's later work, fixing objects of thought, and supplying a context for the possession of the concept of objectivity, are treated as integrated into a single argument. I will explain why, despite its advantages, I am not yet convinced either that triangulation solves the problem of fixing thought contents or that linguistic communication is required for possessing the concept of objectivity. The second is the attribution to Davidson, and defence of, a non-Humean conception of pro-attitudes, principally in relation whether they are globally sensitive to the independently determined contents of normative beliefs. I will raise some doubts about whether Davidson did endorse this non-Humean conception of pro-attitudes and argue that in any case a decision-theoretic revision of the simple Humean theory of the pro-attitudes (which there is good reason to think that Davidson endorsed) handles the considerations that motivate adopting the non-Humean alternative.

2. The Triangulation Argument

Verheggen notes that in the literature on Davidson's later work it is standard to distinguish two contextsFootnote 1 in which Davidson invokes the idea of triangulation.Footnote 2 The first is to determine where on a causal chain leading to a response to locate what an agent is thinking about — for instance, the stimulation at the sensory surfaces, the wave of electromagnetic radiation two meters in front of her, the television set, cable junction box at the edge of the yard, television station, events at a trouble spot in the Middle East, the coalescence of the solar system out of a cloud of cosmic dust, or the Big Bang. The second is to explain the source of the concept of objectivity, that is, of the distinction between true and false belief, of a world distinct from what we think it is, possession of which Davidson held was necessary to have propositional attitudes.

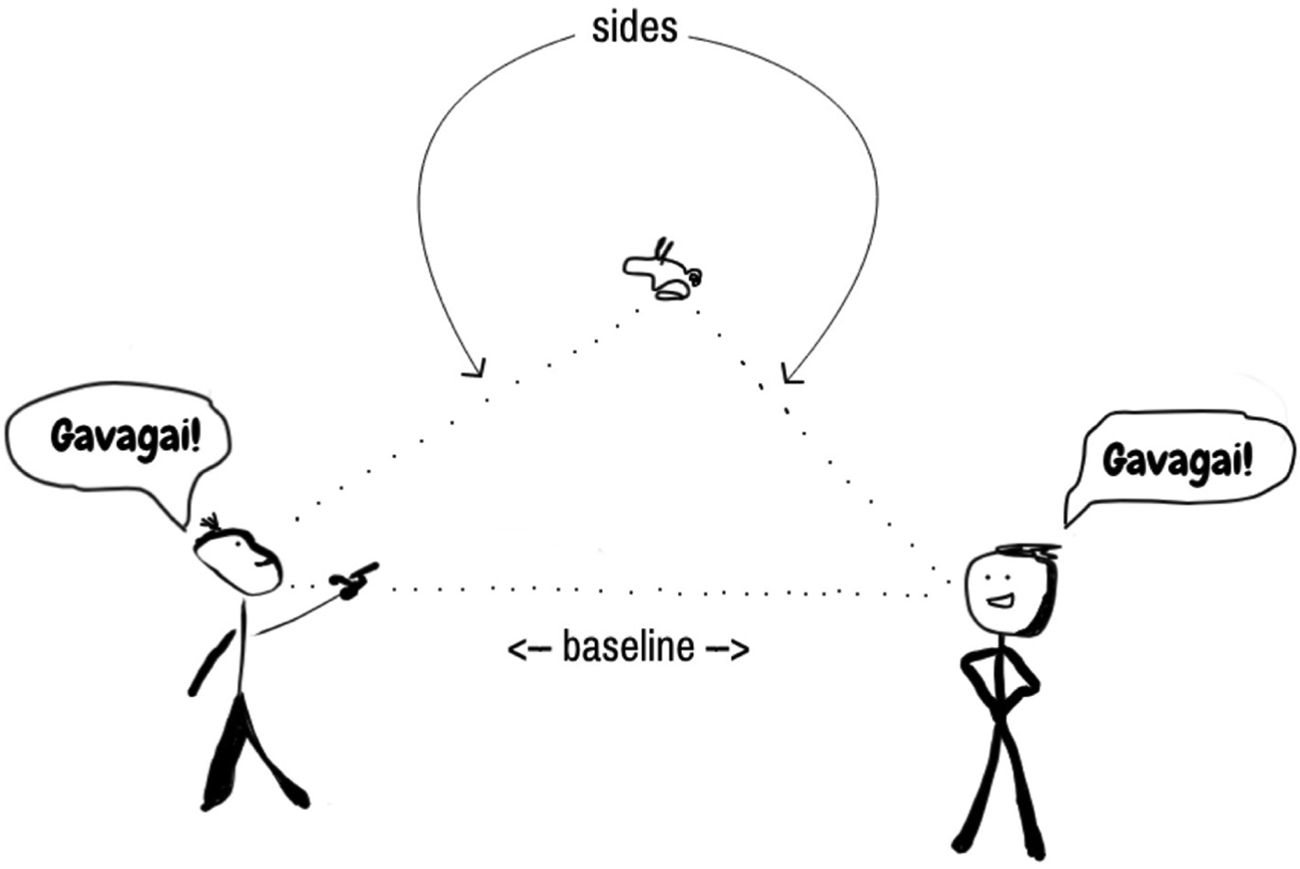

What kind of triangulation is supposed to solve these problems? The basic idea is that, when two people are communicating with one another about something in their immediate environment (a basic case of communication in the sense that if there were no such cases, there would be none at all), they are responding (in roughly the same way) to the same thing (in the environment) at the same time (roughly) that they are responding to each other's similar responses to it. They thus triangulate on the object about which they are communicating. The common object is the vertex of the triangle, the sides are the lines from it to each speaker, while the base is formed by their responses to each other, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Linguistic Triangulation

The idea is that, to solve the first problem, namely, cutting the causal chain leading to a thought at the link it is about, we must have more than a solitary thinker. For the solitaire, in Verheggen's useful terminology, we can find nothing that determines which of the nodes of the web of causal influences on her reactions should be the objects of her thoughts. If we think that something about her interaction with her environment must metaphysically determine what it is that she is thinking about, if she is thinking, then given that thought is possible, we should conclude that the environment of a solitaire is not sufficient for thought. Davidson suggested that a crucial part of the solution is to add another speaker. We identify the object of thought for each (given that everything else necessary is in place) as the link at which the causal chains leading to their similar reactions to the environment and to each other intersect, the apex of the triangle in Figure 1. This provides an objective answer (something in the structure of the world and how they are embedded in it) to the question what their thoughts are about. While this leaves a further problem, what aspect of the object the thoughts are about, this is to be handled by an application of Mill's Methods, seeing what is common between the circumstances in which a given response is produced (by each of a pair triangulating on the object and responding to each other) and absent when it is not.

As Verheggen notes, one problem is that it is not clear that there is only one common cause of the thoughts of thinkers in communication with each other, and the hopeful thought that it is “the nearest mutual cause of the joint reaction”Footnote 3 won't in general yield the right answer. For example, if we are sitting on the couch watching television, there are many common causes of our similar responses: the electromagnetic radiation in front of the television screen (the nearest mutual cause of the joint reaction), the television screen, the signal in the cable junction box, and so on right back to the Big Bang.

In connection with the second problem, we assume that to have the concept of objectivity (or error) requires scope for its application in one's experience. The context of communication is sufficient because the concept of error plays a crucial role in making overall sense of another as a rational agent responding to you and to a shared environment. For while sometimes the interpretation that makes the other most rational involves taking him to mean something other than what you do by a shared word, other times it is better to find him to be in error (from your point of view) about what is going on in his environment, or the world generally. For example, when the other says ‘Lo, a rabbit’ on spotting what you recognized to be a hedgehog, though interpreting ‘rabbit’ on other occasions has facilitated smooth communication, the least overall adjustment to your theory may involve attributing to him an error, especially when you have a plausible explanation of the mistake (the angle of sight obscures the head from your interlocutor). Davidson requires for his purposes, however, that the context of communication be not only sufficient but also necessary, for he wants to argue that, since the concept of objectivity is necessary for thought, and language is necessary for the concept of objectivity, language is necessary for thought. Thus, it has appeared to interpreters (including this one) as if Davidson was arguing in roughly the following fashionFootnote 4:

(1) To have the concept of a belief, one must have the concept of error, or, what is the same thing, of objective truth.Footnote 5

(2) That something possesses the concept of error, or objective truth, stands in need of grounding: this must take the form of explaining how there could be scope in its behaviour or experience for application of the concept. (Implicit premise.)

(3) There is scope for the application of the concept of error in interpretation to achieve a better rational fit of a speaker's behaviour to the evidence we have for his beliefs and meanings.Footnote 6

(4) There is scope for the application of the concept of objective truth in a creature's behaviour or experience only if it is (or has been) in communication with others.Footnote 7

(5) Therefore, from (2) to (4), to have the concept of error or objective truth, one must be (or have been) in communication with others.

(6) Therefore, from (1) and (5), to have the concept of belief, one must have a language and be (or have been) in communication with others.

There are two plausible objections. First, (2) does not support the inference to (5) because at most it gets us that, from the agent's subjective point of view, there must be scope for the application of the concept, but this does not secure its objective application. Second, (4) is false because it is easy to imagine other contexts in which there is scope for the application of the concept of error, e.g., in reviewing a calculation when reliance on it leads to a problem, or in adjusting one's view in the light of evidence that contradicts what one had formerly believed.

I have rehearsed these arguments separately because a central theme of Verheggen's interpretation of the role of triangulation in Davidson's philosophy is that (i) it is a mistake to treat them as independent arguments, and (ii) when they are combined into a single argument, or a single picture, they are mutually supporting in a way that shows how the standard objections can be countered.

How does this work? Here is the combined argument, as I understand it. Verheggen distinguishes primitive and linguistic triangulation (DDTA, p. 15). Primitive triangulation does not require propositional attitudes. Two lions might triangulate in this sense on the same gazelle (assuming with Davidson that thought requires language). Linguistic triangulation is the sort that I described above in the context of communication. Primitive triangulation, according to Davidson, is a necessary condition on having thoughts with determinate contents, and so a necessary condition on having thoughts, but it is not sufficient. It is not sufficient because it is not sufficient to show that a creature has concepts of particular objects or types of objects.

Why is even this much necessary? In the background is the assumption that thought is externally determined. At one point, Verheggen calls this the first premise of the triangulation argument. We'll come back to this later. So the idea is that something must determine thought contents, and, without triangulation, there is no hope of determining thought contents. Behind this in turn is the thought that there must be a story about how thought contents are determined. It can be by way of external factors or internal factors. Verheggen argues that the internalist about the factors that fix thought content (e.g., functional role or phenomenal experience) is no better off than the solitaire. So we get to the need for triangulation by an argument by elimination.

At the same time, in distinction from Davidson, Verheggen argues that primitive triangulators are no better off than the solitaire or, conversely, that the solitaire is no worse off. We must be a bit loose about what counts as a common cause in many cases because of the different perspectives triangulators have on objects. But then similarity of causes rather than sameness appears to be at most what is needed. Why then isn't the solitaire in at least as good a position, for she can triangulate with herself on common responses to similar causes: looking at the table now turning away and looking again, walking around something while looking at it, seeing and touching the same thing, etc.? And if there is an issue about the width as well as the depth of the common cause (how much of the television, screen, plus frame, plus case, etc., and its environs we are thinking about, and what about it we are thinking), it is a problem for both.

The solution to these problems, which brings the concept of objectivity into the frame, is linguistic triangulation:

The crude answer is that, since no non-intensional magic trick will do to fix the causes, and hence the meanings, of one's thoughts and utterances, only those producing the thoughts and utterances could achieve this feat. And they could achieve it only by having the concept of objectivity and triangulating linguistically with others. (DDTA, p. 20; emphasis added)

I understand this as follows. Primitive triangulation per se is neither sufficient nor necessary (pace Davidson) for having thoughts with determinate contents. Rather, linguistic triangulation, that is, triangulation in which each individual in a communicative exchange possesses and is at least ready to deploy the concept of error as needed, is what determines what thoughts are about. This is because it is by their recognizing that they are both responding in similar ways to the same cause (a cause classified in the same way by each) that they make it the case that (or maybe: it is made the case that) they are thinking about the same object.

Thus, Verheggen says:

Triangulation is not supposed to answer, first, the question of how meanings can be fixed and then, only afterwards, the question of how one may possess the concept of objectivity. Rather, triangulation accomplishes both tasks at once, for possession of the concept of objectivity is required for the determination of meanings. Only those who possess the concept are in a position to disambiguate the causes of their utterances in that only they can solve the aspect problem. … Perhaps the best way to express the idea here is to say that only of someone who is in a position to have the concept of objectivity can we say that her utterances are meaningful because only of such a person can we say that the meanings of her utterances have been fixed. (DDTA, p. 21)

Saying that “those who possess the concept … solve the aspect problem” suggests that they do it by deciding what they are thinking (which would presuppose what they were deciding, namely, that they had determinate thoughts). However, the last sentence in this passage suggests rather that (i) it is only when (mere) triangulation and the rest of the pattern of behaviour that suffices for an interpretation of something as a speaker are in place that we can legitimately attribute thoughts to her and meanings to her utterances but (ii) this must include at the same time the attribution of the concept of objectivity. To put it another way, the concept of an agent, a creature minimally with beliefs, desires, and intentions, and so the capacity to act, captures a pattern in the behaviour of an object in an environment — one that cannot be picked out by any other vocabulary.Footnote 8 That pattern has to make sense of the creature as having determinate thoughts and as possessing the concept of objectivity. The only pattern that supports both at the same time involves two agents who can be interpreted as being in communication with one another.Footnote 9

This is a really neat idea about how to interpret Davidson and it is very Davidsonian. I find it hard to think that he would have objected to this way of characterizing his thinking even if it is not so easy to see it stated explicitly in the essays. Insisting on linguistic triangulation as the solution to the problem of determinate thought, it appears to block two objections at once. The first is that there are contexts other than communication in which the concept of objectivity can be acquired — for those contexts would not, if the thought is right, be adequate for determinate thought. The second is that at most we get a subjective rather than an objective application of the concept of objectivity — for fixing the contents of thoughts requires objective triangulation on shared causes of common responses, so that the applications of the concept of objectivity have to themselves be objective. At the same time, by requiring that the concept of objectivity be acquired in the context of linguistic communication, it appears to block the thought that triangulation in any other context could suffice for determinate thoughts because it does not suffice, if the thought is right, for the concept of objectivity. In this way, putting the two ideas together enables each to lend support to the other. This, as I understand it, is how, at least in part, reconceptualizing the two roles triangulation plays as roles in one argument puts the resulting argument in a better position to respond to the objections that have been raised to each considered separately.

3. The Determination Assumption and the Contrast between Solitaire and Pair

I proceed in two stages. I start with a background assumption. Then I turn to the argument against the possibility of the solitaire having determinate thoughts in distinction from a pair.

3.1 The Determination Assumption

The background assumption, [Determination], appears in an argument, [Argument for Externalism] below, whose conclusion is that only an externalist account could satisfactorily answer the question what determines the contents of thoughts.

[Argument for Externalism]

1. [Determination] The contents of thoughts are determined by something independently specifiable.

2. The contents of thoughts are determined either by external factors or by internal factors or by a combination of both.

3. Internal factors alone are not sufficient.

4. [Externalism] Therefore, the contents of thoughts are determined by external factors or a combination of external and internal factors.

If we call an externalist account of the determinants of thought content one which says that there are external elements involved, then we have the conclusion that only an externalist account of thought content could be correct. Now we can argue as follows (though this is not an argument that Verheggen gives, I think that if it is not sound, we should have doubts about the solution offered):

[ALC: Argument from Linguistic Communication]

1. The facts about a solitaire's interactions with its environment are insufficient to determine thought contents; that is, the external factors available are insufficient for determining thought contents.

2. Primitive triangulation is insufficient to determine thought contents; that is, the external factors available in this case are insufficient for determining thought contents.

3. We know speakers in linguistic communication have thought contents.

4. Therefore, there are external factors together with internal factors that suffice in the case of speakers in linguistic communication.

5. The cases of the solitaire and primitive triangulation are the only alternatives.

6. Therefore, by [Externalism], 1–2 and 4–5, linguistic communication (or its supervenience base, whatever it comes to) is necessary and sufficient for thought.

I will go on to ask some questions about the details of argumentation. But my first question is about [Determination]. Davidson accepts this assumption. It is an anti-Cartesian assumption. Why is he entitled to it? If it is not independently justified, then to the extent to which the triangulation argument assumes it, we may object that it relies on an assumption for which no argument has been given.

However, Davidson took himself to have an argument for [Determination].

[Publicity]

1. Language by its nature is public, that is, intersubjective.

2. Hence, by 1, all the evidence for meaning by its nature has to be available to any potential interpreter.Footnote 10

3. Hence, by 2, any speaker must be interpretable in any environment (by any speaker).

4. Attributing propositional attitudes to an agent is inseparable from interpreting speech.

5. Therefore, by 1 and 4, the evidence for propositional attitudes by their nature has to be public in the same sense as the evidence for meaning.Footnote 11

6. Therefore, by 5, something public, and in principle available to any potential interpreter, together with facts about speakers, determines what their thought contents are.

A natural objection is that language is not required for thought (this targets premise 4). Hence, determinate thought does not require interpretability. If thought does not require interpretability, we can tell a story about how language arises out of the capacity for thought in environments in which as a matter of fact agents have access to public clues to meaning without thinking that those facts determine the meanings. For the meanings can be thought of as determined by the intentional use to which speakers put tokens of expression types.

Davidson recognizes that an argument is required. His argument is that having propositional attitudes requires the concept of objectivity, and that it is only in the context of linguistic communication that a creature can come to have the concept of objectivity.Footnote 12 But, in the representation of the triangulation argument above, [Determination] plays the role of a premise. And the conclusion of the argument is that linguistic communication is required for the concept of objectivity. The argument for [Determination] then rests in part on an argument for thought requiring language, which rests on [Determination]. Thus, we have assumed [Determination] to support it.

Rejoinder: But doesn't Verheggen give an account that shows how thought contents are determined that vindicates [Determination]? An account is sketched, and some essential features argued for, namely, that content is possible only in the context of linguistic communication. But the argument puts constraints on a full account (it requires linguistic communication) rather than providing a full account itself (it seems to me). Accepting [Determination] give us the confidence that the story can be completed in a way that makes it clear how it works. However, I suggest below that, on the assumption that the objective facts about the solitaire do not suffice to determine that she has thought contents, the same goes for a pair. This would show, if correct, that an account has not been provided that vindicates [Determination]. In any case, if the argument for linguistic communication being necessary and sufficient rests on the assumption that language is required for thought, and that rests on [Determination], then the argument for [Determination] rests on [Determination].Footnote 13

Apart from this, there is a problem for [Publicity]. Premise 2 doesn't follow from 1. Language is public in that it is a tool for communication. Language must be interpretable by others on the basis of behaviour. Meaning can't be hidden and still serve its role in communication. But it doesn't follow that having the capacity to speak a language means that you can be interpreted on the basis of evidence available to any potential interpreter no matter what. First, we'd have to rule out the possibility that you don't share enough concepts with another who also has a language to be mutually interpretable. Second, it doesn't follow that you would be interpretable in any environment. Language is a tool for communication provided that it does the job in the actual context in which it is used.Footnote 14

The alternative to [Determination] is that intentionality is fundamental. Many people think it is implausible to suppose that intentionality is fundamental. Science has explained much about complex objects by appeal to the features for the constituents and the laws governing them. There seems good reason to think, therefore, that any holdouts will eventually be explained in the same way. The constituents of things don't have mental properties, and the laws governing them don't mention mental properties. So, in the case of thought, even if we haven't succeeded yet, we should (the argument goes) be confident that we will eventually explain thought reductively. [Determination] does not entail reduction but reduction does entail [Determination]. Thus an argument for reduction is an argument for [Determination]. But, first, the inductive argument has a presupposition, namely, that there are no conceptual obstacles to reduction. And, second, this is not a line of argument that would be especially congenial to Davidson since he denies that the mental, though it supervenes on, is reducible to the physical.

3.2 Solitaire vs. Pair

Grant [Determination]. Does the argument go through? This comes to the question whether it is only in linguistic communication that the concept of objectivity has scope for deployment. This is the question whether 1, 2, and 5 are true in [ALC]. Verheggen gives a detailed and subtle argument against objective determination of thought content being possible in the case of the solitaire and non-linguistic animals. I am going to concentrate on the case of the solitaire because it is the best case for finding sufficient complexity in behaviour in relation to the environment to fix thoughts and the conditions for possessing the concept of objectivity.

The solitaire is just like one of us except for operating outside the context of a linguistic community. For a fully realized conception, we can imagine a physical duplicate of one of us, a quantum fluke involving a body coalescing from some sand, sea water, and coconuts, that wakes up alone one morning on a desert island. We can grant that this is not a human being, because it is not a member of the species Homo sapiens. It has no history, so no evolutionary history. But it has all the behavioural dispositions that you do. Its behaviour will be indistinguishable from what yours would have been if you had been transported to the island in your sleep and left in the same place. To the extent to which its stream of phenomenal consciousness is determined by its physical construction, it will be indistinguishable from what yours would have been in its place. Our question is: can we make sense of this physical duplicate of you, which has never engaged in linguistic triangulation, having thoughts and meaning things by certain of its utterances?

The rules of the game are that we have to make sense of its having determinate thought contents and (for the whole package) the concept of objectivity in terms of objective features of its environment and its interactions with them.

Verheggen's argument that the solitaire does not have determinate thought contents begins with a quotation from Davidson, who writes “by yourself you can't tell the difference between situations seeming the same and being the same.”Footnote 15 Why not?

Recall the predicament she is in: no matter how regular her responses to the environment may be, they may still be responses of different kinds; they may be responses to different aspects of the environment. Thus she must be the one to tell, objectively, at least for some of the causes of her responses, which causes are the same as which, which of her responses are correct. But how is she supposed to draw such an objective line between what seems to her to be the same cause, or the correct response, and what is in fact the same cause, or the correct response? (DDTA, p. 22; emphasis added where it is presupposed that the subject has intentionality)

Verheggen goes on to say:

… it may be replied, she might have the following kind of experience: As a result of regularly finding blackberries in some particular bush, she one day experiences frustration upon not finding any in that bush. And it may be argued that experiences of this kind put her in a position to have the concept of objectivity since by hypothesis she realizes that her belief about what is in the bush is false and thus that there is a distinction between what she believes to be the case and what is the case. Now, strictly speaking, by assuming that the solitaire has beliefs, this scenario begs the question against Davidson, if he is right to say that only those who have the concept of objectivity can have beliefs with determinate contents. Thus what we have to imagine here is some experiences of the solitaire putting her in a position to possess both. But then what we have to imagine is the solitaire being able to notice that her present and her former “thoughts” do not match and to decide objectively which way to go. This in turn entails the question, what reason is there to think that she is having a thought about the same bush? Perhaps she is “thinking” that she passed the fruity bush, or that she took the wrong turn … The point is that, whatever she is “thinking”, be it that it is the same bush or that it is not, will be correct, according to her. She does not have to draw one conclusion rather than another. However she draws the line between correct and incorrect responses that will be right to her. There is no way she can do this objectively. (DDTA, p. 22; emphasis added, and footnote omitted)

This predicament is then contrasted with linguistic triangulation. But before we get to the contrast, I want to raise a question about the problem being raised here. The problem is again posed as if it were a problem for the solitaire to distinguish from her point of view (noticing, deciding, drawing the line) a right from a wrong response. But, if she is in a position to raise this question, she already can distinguish between correct and incorrect responses because she can think. So I think this cannot be the canonical way to put the problem. It seems to me that our question is whether the objective facts about the solitaire's behaviour provide a pattern sufficient for the application of the concept of thought and attribution of the concept of error. Hold that thought for a moment while we turn to the contrast with linguistic triangulation.

In the case of linguistic triangulation, Verheggen continues, quoting Davidson:

If you and I each correlate the other's responses with the occurrence of a shared stimulus, however, an entirely new element is introduced. Once the correlation is established it provides each of us with a ground for distinguishing the cases in which it fails.Footnote 16 (DDTA, pp. 22–23)

Verheggen concludes:

What changes dramatically for the triangulator is [not that there is suddenly room for the concept of error but] that she is interacting and so can settle with another person, rather than just with herself, the ways in which perspectives on a given event or state of affairs may diverge. As long as the responses of triangulators do not diverge, they presumably cannot yet objectively distinguish between what seem to them to be the same, or the correct, responses and what are the same, or the correct, responses to their environment. But if their responses diverge, the distinction is “forced” upon them, as Davidson once put it (Davidson Reference Davidson and Guttenplan1975, 170). It is forced upon them because they have no choice but to negotiate, so to speak, the resolution of the divergence. Thus, suppose that they have been picking blackberries in a particular bush and one day they come across a bush that is empty of blackberries. One of them insists that it is the same bush now empty of blackberries; the other maintains that it is a different bush because they took a wrong turn. How they settle the dispute cannot be dependent on one or the other interlocutor but must be the result of genuine communication between them. (DDTA, p. 23; emphasis added)

These passages also seem to presuppose that their subjects are already able to think and are posed the task of distinguishing between correct and incorrect responses. The objection to the solitaire was that whatever she decided was right would be right (but don't wrong decisions have consequences if one acts on them, which will often show them to be wrong?). The presence of another is supposed to get around that. But why? Because one disagrees with another? But that presupposes that one already has the concept of objectivity, and if you give that to the solitaire, she can find something she thinks to be contradicted by new evidence. If we do not presuppose that two individuals triangulating have the concept of objectivity, what is supposed to determine that they have it? We can admit that there is scope for its use in interpretation, but Verheggen agrees that there is (potential) scope for its use for the solitaire. We get that they have to negotiate, when they are engaged in a joint action, and disagree, but only if we have already presupposed that they have the concept of objectivity and have thoughts. We need to say what about the behaviour pattern in the case with two individuals, described neutrally with respect to whether those exhibiting it have thoughts and the concept of objectivity, adds something crucially missing in the case of the solitaire. In requiring this, we are not assuming that thought and meaning are reducible but only that they supervene on facts about actual and potential behaviour in an environment, as Davidson holds explicitly. So we can ask: if the solitaire's behaviour in its environment is an inadequate supervenience base, what about the case of two creatures’ interaction in an environment makes the difference?

Consider your duplicate on the desert island. Let's call her Robin for convenience. Robin exhibits a pattern of behaviour that we are inclined to describe as wandering around the island, seeking food, building a shelter, lighting fires, carving a face on a coconut, and so on. In saying this, I do not mean to be asserting that she wanders around the island, seeks food, builds a shelter, etc., but only to be identifying the patterns of behaviour we would ordinarily describe that way. Continuing in this vein, perhaps one day she seems to find some blackberry bushes and seems to harvest some for food. She returns a few days later and appears to be disappointed — perhaps if we could listen in, we would hear something that sounded like, ‘Damn, I thought there were more berries here, but they are all gone now. I know it is the same bush because it was growing next to the stream by that rock that looks like a duck's head. Probably some animal has got them since I was last here.’ Later, over a period of several days, she appears to gather rocks, which she then appears to be arranging on the beach to spell out what for all the world looks like ‘H E L P.’ We know a lot more about Robin's potential behaviour than this. We know that if you visited her, she would produce a noise that sounds like English (though perhaps it means nothing): ‘Thank God, I thought I would be stranded here forever! Where am I? How did I get here? I fell asleep one night and the next morning I woke up here on the beach! You wouldn't believe how starved I have been for the sight of another person.’ Call this super complex pattern of actual and potential behaviour in relation to her environment RP (for ‘Robin's Pattern’).

Consider another island on which, fortuitously, as Robin appears on the beach on one side of the island, a duplicate of her original's best friend (call him Friday) appears on the beach on the other side of the island. They too (Robin and Friday) appear to wander around, build shelters, light fires, carve faces on coconuts, and so on. They also appear to locate some blackberry bushes, and each comes back to the same one and appears to be disappointed, etc. Then, one day they meet while seeming to look for blackberries. Thereafter, they are inseparable. One day, they return to a blackberry bush they had visited together before. Robin seems to say, ‘Damn, I thought there were more berries here, but they are all gone now. I know it is the same bush because it was growing next to the stream by that rock that looks like a duck's head. Probably some animal has been here since we were last here.’ Friday seems to say, ‘No, you're mistaken. We haven't been to this bush before. The bush we harvested last week was next to a rock that looked like a rabbit.’ And so on. We also know a lot about their potential behaviour, as for solitaire Robin. Call this super complex pattern of interwoven actual and potential behaviour after they meet RFP (for ‘Robin and Friday's Pattern’).

Our question is this. Is there something in RFP that supports attribution of thought and the concept of objectivity which is missing in RP?

Provisionally accepting [Determination], our question is basically whether RP suffices to determine an acceptably determinate interpretation scheme. There is one obvious interpretation scheme that fits RP. That is roughly the interpretation scheme we would apply to you (as the person of whom Robin is a duplicate) if you had been transported to a desert island. We would, of course, make adjustments in our distribution of truth values over attitudes, and treat some of her utterances as failing of truth value because they involve directly referring terms which require her to have a history that she does not. But by and large we know what would work to make sense of her behaviour and enable us, on meeting her, to converse fluently (to all intents and purposes). Can we be confident that there is any other pattern that would do as well, at least that we could arrive at without starting with the obvious one? As a practical matter, I think the answer is no, though there may be reasons to think that it could be done in principle. However, let us grant this possibility. And let us grant that it would be possible to develop an alternative scheme that was so radically different that it calls into question whether the objective facts in the case of the solitaire suffice to determine her thought contents. The question is whether adding another speaker to the picture makes a difference in that respect.

In the case of RFP, it is also clear before the fateful meeting at the blackberry bush that there are obvious interpretation schemes that fit Robin and Friday, namely, the ones that would be appropriate for you and your best friend if you had been transported to the island. We suppose there are also alternatives that are too radically different. But after they meet and disagree, do we now have a pattern that resists in principle the possibility of a radically different interpretation scheme being imposed? As a practical matter, yes, but that is so in the case of RP as well. Shouldn't we expect it to be more difficult though? Maybe, but it is hard to see how to prove that there could not be some alternative so radically different that it calls into doubt, as for the solitaire, whether the objective facts suffice to determine their thought contents. Moreover, there is a reason to be sceptical that the objective facts suffice for determinate thought contents.

The reason is that we can construct a radical scheme on the basis of what we have already granted about the solitaire. Suppose that there is a radically different scheme for RP from the natural one, so different that we think that what it means is that the objective facts do not suffice to determine thought contents. Call the first sort of scheme ‘Natural’ and the second sort ‘Radical.’ We apply a Natural scheme to both Robin and Friday in the case of the double duplication before they meet, and they mesh, of course, when they get together (as we can see beforehand). If there is a Radical scheme for Robin as a solitaire, there will be a corresponding one for Friday in the double duplication case before they meet. But then shouldn't we find those schemes meshing when Robin and Friday get together? In this case, there is a radical alternative interpretation scheme for RFP, as there is for RP, and we still have not found anything in RFP that shows that, if we can't get a sufficiently determinate scheme for RP, RFP supplies what is missing. If this is right, then the argument for the necessity of linguistic triangulation for thought and meaning and possession of the concept of objectivity fails.

If we decide that RP is not sufficient to determine thoughts, then we have to give up [Determinism], if the above argument is correct, because adding interlocutors doesn't help. If we decided that RP is sufficient to determine thoughts, then the conclusion is weaker. Provided that we are willing to think of solitaire Robin as having a language as well as thought, Davidson could still maintain just about everything he wants to. The thought would be that being capable of speaking to and interpreting others is necessary for having the concept of objectivity and thought. All Davidson must to give up is the claim that being or having been in communication with others is necessary.

4. The Humean and Non-Humean Accounts of Pro-attitudes

As early as 1984, in “Expressing Evaluations,” Davidson sought to extend the claim that to interpret a speaker one must find him by and large right in his beliefs and so agreeing with the interpreter, to finding him also right in his values, from the interpreter's point of view, and so sharing values with the interpreter. There are hints of the same idea in earlier work. Myers argues that there is more to the idea than most commentators have thought. Central to this is an interpretation of Davidson's views on pro-attitudes that runs contrary to how most commentators understand Davidson. In a nutshell, and I will explain what this comes to in a moment, the idea is that Davidson is a Humean about motivation but a non-Humean about pro-attitudes. In my comments on the second half of the book, I want to focus on this interpretation. I will raise some doubts about whether Davidson was a non-Humean of the sort Myers describes. I will also raise some doubts about the argument for the non-Humean conception, which rests, I think, on an understanding of the Humean position that is not fully adequate to the most sophisticated modern versions of it. I have in mind the conception expressed in decision theory, which we know Davidson incorporated into his account of human agency and interpretation.

Before we get to the distinction between a Humean theory of motivation and of the pro-attitudes, I want to sketch Davidson's argument for shared values. Myers characterizes this as an argument for shared normative beliefs about what considerations there are in favour of action. I think the latter characterization is probably not broad enough since we can have values that in light of our beliefs don't provide any considerations in favour of action. We can put this aside for the moment. The decision-theoretic Humean position will apply a correction.

Myers distinguishes two arguments in Davidson, an argument from interpretation that depends on the principle of charity, and an argument from triangulation that rests on the need to identify the objects of thought. Here is a passage from “The Interpersonal Comparison of Values,” in which the first thought lies in the foreground (interpreting ‘charity’ as requiring agreement):

It is inevitable that different considerations will often favor different interpretations. Remembering that the underlying policy of interpretation requires us to choose an interpretation that matches the other's beliefs and desires to our own as far as possible, the conflict in considerations means that we have come across a recalcitrant case. Making a fair fit elsewhere perhaps forces us here to interpret a sentence the other holds true and wants true by one we hold true while hating that we must.Footnote 17

The other theme seems to emerge in “The Objectivity of Values”:

Objectivity depends not on the location of an attributed property, or its supposed conceptual tie to human sensibilities; it depends on there being a systematic relationship between the attitude-causing properties of things and events, and the attitudes they cause. What makes our judgments of the “descriptive” properties of things true or false is the fact that the same properties tend to cause the same beliefs in different observers, and when observers differ, we assume there is an explanation. This is not just a platitude, it's a tautology, one whose truth is ensured by how we interpret people's beliefs. My thesis is that the same holds for moral values. Before we can say that two people disagree about the worth of an action or an object, we must be sure it is the same action or object and the same aspects of those actions and objects that they have in mind. The considerations that prove the dispute genuine — the considerations that lead to correct interpretation — will also reveal the shared criteria that determine where the truth lies. Footnote 18

Similarly, in “Expressing Evaluations” he writes:

As with belief, so with desire or evaluation. Just as in coming to the best understanding I can of your beliefs I must find you coherent and correct, so I must also match up your values with mine; not, of course, in all matters, but in enough to give point to our differences. This is not, I must stress, to pretend or assume we agree. Rather, since the objects of your beliefs and values are what cause them, the only way for me to determine what those objects are is to identify objects common to us both, and take what you are caused to think and want as basically similar to what I am caused to think and want by the same objects. As with belief, there is no room left for relativizing values, or for asking whether interpersonal comparisons of value are possible. The only way we have of knowing what someone else's values are is one that (as in the case of belief) builds on a common framework.Footnote 19

Philosophers have found these arguments unpersuasive. Desire does not play the same role in interpretation that belief does. To break into the circle of meaning and belief, Davidson says that we need to identify hold-true attitudes. These are the product of beliefs about the world and knowledge of the meanings of sentences. If I believe that the moon is full and I know that ‘the moon is full’ means that the moon is full, I hold true the sentence ‘the moon is full.’ Davidson imagines us finding correlations between hold-true attitudes (identified on the basis of more primitive data ultimately) and what's going on in the environment of the form: S holds true ‘the moon is full’ iff the moon is full. To solve for meaning, we assume the belief on the basis of which the sentence is held true is itself true, and infer that the sentence held true in these circumstances means (ceteris paribus) the same as the sentence that expresses the condition that is correlated with its being held true — if S holds true ‘the moon is full’ iff the moon is full, we assume (ceteris paribus) that this is because S means that the moon is full by ‘the moon is full’ and believes correctly that the moon is full. This ensures we interpret the other as sharing with us the belief that the moon is full. But the contents of desires are not typically correlated with what they are about since their job is not to match the world but, to put it roughly, to get the world to match them. We get at the contents of desires indirectly. We try to make the other mostly rational both theoretically and practically. Thus, we aim to find patterns of behaviour interpretable as actions and read in desires compatible with the beliefs we attribute that makes sense of some available pattern as rational. Thus, there is no direct argument for our sharing desires in the way there is for our sharing beliefs about our environment. Moreover, this seems prima facie to leave wide open whether another shares values with you, or would upon full information. Identifying what it is that you disagree about wanting to be the case seems to require agreement in belief but not to imply anything about whether there is a background of shared values.

This objection depends on taking Davidson to be arguing directly for the conclusion that sharing a lot of pro-attitudes is required for interpretation. Myers's strategy in responding on Davidson's behalf is to (i) shift attention to shared normative beliefs, first, and then (ii) argue that they are not mere expressions of pro-attitudes. Then the idea is that the usual arguments for sharing objectively correct beliefs will carry over to normative beliefs. For beliefs to be normative, they must be about considerations in favour of acting (or maybe about what would generate considerations in favour of acting depending on what one believed the actions open to one might be able to bring about), where for them to be reasons in the relevant sense they have to make a difference to how one is motivated to act.

This is where the distinction between a Humean theory of motivation and of the pro-attitudes comes in. A Humean theory of motivation, as Myers understands it, holds that beliefs can never motivate action alone, and Myers accepts that Davidson held a Humean theory of motivation. Many philosophers, Myers says, have also thought that Davidson holds a Humean theory of pro-attitudes. What is a Humean theory of pro-attitudes?

[Simple Statement]

A simple statement of it might go something like this: A pro-attitude towards Ψ-ing is a disposition to do whatever one believes will increase one's chances of Ψ-ing. (DDTA, p. 142)

So a non-Humean theory of the pro-attitudes is simply one that denies this. But Myers has in mind a specific contrast which is supposed to help show how we can use charity to argue for agreement on normative beliefs while also retaining a connection with how one is motivated to act. The idea is that pro-attitudes, while they do figure in explanations of behaviour in the usual ways, are systemically influenced by one's normative beliefs in that they are inter alia dispositions to respond to normative beliefs. This is not supposed to mean that for every normative belief one will have a pro-attitude towards an action in virtue of having the belief, or that one might not act against one's reasons. It is rather that pro-attitudes “are typically dependent on normative beliefs … considered as a system or a whole” (DDTA, p. 148).

Myers argues both that the Humean theory of pro-attitudes is inadequate to our understanding of why we act, and that Davidson rejected it in favour of the non-Humean theory that Myers describes.

This is also a neat idea. It aims to get around what seems to be a devastating objection to Davidson's project of grounding the objectivity of values in conditions for interpretation by (1) rejecting an account of the nature of pro-attitudes typically attributed to Davidson, and (2) substituting for it an account that makes them sensitive to normative beliefs. It subsumes normative beliefs under the usual arguments for agreement and objective truth. Pro-attitudes are then responsive to them while maintaining their status as a distinct type of state.

5. Defending a Humean Account of Pro-attitudes and the Standard Interpretation of Davidson

I want to take a close look at the argument against the Humean theory of pro-attitudes and at the same time make a case that Davidson accepted a Humean theory of pro-attitudes.

5.1 The Humean Theory of Pro-attitudes

The simple statement of the Humean theory, repeated here,

[Simple Statement]

A simple statement of it might go something like this: A pro-attitude towards Ψ-ing is a disposition to do whatever one believes will increase one's chances of Ψ-ing. (DDTA, p. 142)

is obviously inadequate. I doubt that any modern philosopher of action would endorse it. First, not all of our desires (let this stand in for pro-attitudes in general excepting intentions) are directed towards action and in fact it is doubtful that very many of our non-instrumental desires are directed at particular actions or at action types. What is wanted is a general characterization of the role of desire in relation to action, not an account of desires directed specifically towards action. These are typically derived from other desires. Second, we have many desires. Some conflict outright and others conflict in the light of what we believe. Their influence on action is mediated by our other beliefs and desires (and how we rank them) and crucially by intention. However one characterizes the functional role of desire, it cannot be simply in terms of a disposition to do something when one sees it as promoting the object of the desire. This is something that Davidson was clear about from his earliest work in the philosophy of action. So if [Simple Statement] were all the Humean theory could come to, then I agree that it is false and that Davidson was not a Humean about pro-attitudes. But I think most modern self-identified Humeans about pro-attitudes would claim that [Simple Statement] does not adequately characterize their view.

Myers argues against [Simple Statement] by example. Is my desire to win at chess a disposition to do whatever I believe will increase my chances of winning at chess? If this means that winning is taken to be a commitment that trumps all others, obviously not. I could win by playing weak opponents, but instead I play credible opponents. Myers imagines a Humean responding that the content of the desire is underspecified, and that includes winning against credible opponents. But couldn't I do that by unnerving them? Myers imagines the Humean invoking another pro-attitude to maintain a reputation for fair play. Against this, he says:

That seems just false to me. I think it is perfectly possible that I may actually not be disposed to unnerve my opponents because I see no way at all in which defeating my opponents by unnerving them would respond to the reasons I believe I have for wanting to win at chess against credible opponents in the first place. For example, I may believe it is a good thing to develop skills of the sort required to win at chess against credible opponents, and it may be true of me that I wouldn't have any desire to play chess at all if I didn't have this belief. If such is indeed the case, and I believe defeating my opponents by unnerving them would not require skills of the sort that I believe I have reason to develop, then why would I be even the least bit disposed to try to unnerve them, even if I did believe that doing so would increase my chances of defeating them? (DDTA, p. 145)

Myers does raise the question whether “this is really the only or the best way to avoid the [Simple] Humean view,” and notes that “Davidson himself might be enlisted in support of this worry, for when he discusses cases like one's desire to win at chess, his suggestion is that the content of the pro-attitude is probably conditioned not by one's normative beliefs but by other pro-attitudes that one has” (DDTA, p. 145). The passage Myers has in mind, from “Representation and Interpretation,” I think, is this:

Ordinary desires like wanting to win at chess compete with further values, they are conditioned by experience, and grow stale with repeated frustration.Footnote 20

But Myers sees “no plausible way to develop” (DDTA, p. 146) the idea that avoids the problems already raised. In contrast, I think that there is a plausible way to develop it and that it is what Davidson had in mind all along.

First, though, Davidson does not say that pro-attitudes affect each other's content. He says that desires compete against each other, and this is the key to the whole puzzle. For desires as such are not commitments to action. This is a lesson from “How Is Weakness of the Will Possible?”Footnote 21 It is rather that they each have their weights, and their weights together with one's beliefs about the likelihood of their being satisfied on the condition that one performs one or another action open to one, determines what one intends, if all goes well. Decision theory, which introduces the notions of a preference ranking and of a degree of belief, makes this more precise. Suppose you are faced with (from your point of view) a range of actions that you could undertake: α1, α2, α3, …, αn. Suppose for each action there are a range of possible outcomes relevant to your desires: O i1, O i2, O i3, … O im, where ‘i’ is replaced by the index for the action, αi.Footnote 22 Each outcome will have implications for which of your desires are satisfied or frustrated. We assign a value, represented by a number, V(O ij), to each outcome that is the sum of the relative weights of your desires, positive if satisfied and negative if frustrated, to which the outcome is relevant. This induces a partial preference ordering on the outcomes. (Of course, we idealize in assuming all desires have at the outset a determinate weight that represents their ranking relative to others. But, in the crucible of choice, they must, if relevant to the decision, be assigned a place in one's subjective ranking, and so the account of the conditions for rational choice remains the same.) The value (or disvalue) that each possible outcome contributes to performing action αi is weighted by the subjective probability of (degree of belief or confidence in) that outcome obtaining given that you perform αi. The expectation value, EV(αi), of the action, is the sum of the values of the possible outcomes weighted by their subjective probability.

The action with the highest expectation value is the one that it is rational to choose, if there is a highest; if there are ties, then it is rational to choose any of them. The choice is represented by the formation of an intention, which is a commitment to performing the action, a pro-attitude whose conditions of satisfaction require it to bring about the action it aims at in accordance with a plan the agent has at the time of acting. This gives us a more sophisticated Humean account of the functional role of desire in the production of action. We do not say that a desire is a disposition to do whatever it takes to satisfy it. We say that a desire in an ideally rational agent contributes to the determination of commitments to action in the way specified above.

How does this apply to the case of playing chess? Playing chess is a determinable. Some aspects of the determinate form are (in part) up to you. Two varieties are what we might call ‘unnerving chess play’ and ‘fair chess play,’ conceiving both as aiming at winning. Suppose for simplicity that these are the only two options, and that there are no other outcomes besides the instances of the one or the other form of chess. Suppose that you want to develop skills of the sort required to win against credible opponents (in fair play), and that this is higher in your preference ranking than any desire or conjunction of desires that might be satisfied by unnerving chess play, and that you believe that it is quite likely that playing against credible opponents with the aim of winning will lead to developing skills of the sort needed to win against credible opponents, while the probability is very low in the case of unnerving chess play. Suppose that it is no more likely that in playing unnerving chess you would satisfy whatever other desires might thereby be satisfied. Then the expectation value for fair chess play is higher than that for unnerving chess play. The decision-theoretic Humean theory predicts that if you are rational you will not have any disposition to play unnerving chess. For having a disposition to act is to have an intention to act.

Is it able to explain the sense in which trying to unnerve your opponent would not speak to the reasons you have for wanting to win at chess, namely, “it is a good thing to develop skills of the sort required to win at chess against credible opponents” (DDTA, p. 145)? The answer the sophisticated Humean gives is that the evaluative judgement is itself an expression of an antecedent pro-attitude, which has its weight in tacit practical deliberation. Relative to it, unnerving chess play is not seen as an action type that will promote satisfying the pro-attitude. Thus, unnerving one's opponent does not speak to the reasons you have for wanting to win at chess.

This is a Humean theory to the extent to which we say: and that is all there is to it. You have the preferences, and the rest flows from that. Your beliefs provide the weighting for the ends open to you to pursue in deciding what is best. There is no reasoning your way to acquiring or giving up preferences that does not start with other preferences (which could be higher-order preferences as well as first-order preferences), and no legitimate rational influences on them other than through practical reasoning grounded in your basic preferences. Your normative beliefs, beliefs that give considerations in favour of action, are simply expressions of your pro-attitudes or the result of inference from them together with what you believe about the world (and so you can make mistakes).Footnote 23 For desires, they would be what Davidson calls prima facie judgements in “How Is Weakness of the Will Possible?” For a simple desire to experience the taste of curry chicken, the judgement is that experiencing the taste of curry chicken is good insofar as it is experiencing the taste of curry chicken. When we consider actions that bear on the satisfaction or frustration of many desires, the judgements about those actions will be relative to all the considerations taken into account in reaching a judgement that it is good or bad. When we have taken all relevant considerations into account and all the options open to us, we reach a judgement that corresponds to the judgement that the expectation value of one action is higher or at least as high as any other. The unconditioned judgement expresses the formation of an intention.

It is certainly possible to modify this view by holding that not all normative judgements are expressions of pro-attitudes and that some of those are ones to which pro-attitudes are systemically sensitive. Then the argumentative strategy could be resumed. So it might still be open to defend Davidson in the way suggested.

5.2 Was Davidson a Non-Humean?

But is that Davidson's view? I have some doubts about that. First, Davidson did endorse decision theory. In his later work, he aimed to integrate decision theory into his account of how the interpreter could work his way into the language and thought of another speaker without presupposing prior knowledge.Footnote 24 This leaves it open that he might have rejected the claim that normative or evaluative judgements express pro-attitudes. But, second, Davidson at one point says explicitly that evaluative judgements express pro-attitudes (emphasis added):

The natural expression of his desire [wanting to improve the taste of the stew] is, it seems to me, evaluative in form; for example, ‘It is desirable to improve the taste of the stew’, or ‘I ought to improve the taste of the stew’. We may suppose different pro attitudes are expressed with other evaluative words in place of ‘desirable’.

There is no short proof that evaluative sentences express desires and other pro attitudes in the way that the sentence ‘Snow is white’ expresses the belief that snow is white. But the following consideration will perhaps help show what is involved. If someone who knows English says honestly ‘Snow is white’, then he believes snow is white. If my thesis is correct, someone who says honestly ‘It is desirable that I stop smoking’ has some pro attitude towards his stopping smoking. He feels some inclination to do it; in fact he will do it if nothing stands in the way, he knows how, and he has no contrary values or desires. Given this assumption, it is reasonable to generalize: if explicit value judgements represent pro attitudes, all pro attitudes may be expressed by value judgements that are at least implicit. Footnote 25

This was Davidson's view in 1978. I think it is plausible to think this was his view in earlier work as well. It is very natural to read “How Is Weakness of Will Possible?” from 1969 in the light of this thesis, and it would explain why in early work he sometimes mentioned normative judgements as among the pro-attitudes, thinking that they represented pro-attitudes and so were a typical way of expressing them. Did Davidson change his mind after 1978?

I think there are two main considerations that Myers advances, aside from the interpretation helping to make a better case for Davidson's argument that we must share values as well as beliefs.

The first is a passage from “Expressing Evaluations,” which Myers claims shows that “Davidson is careful to make it clear that he thinks it would be a distortion to identify normative beliefs and pro-attitudes” (DDTA, p. 141). The passage is (numbering added):

What is the difference between embracing an evaluative sentence and embracing a descriptive sentence? We have already made the obvious observation that embracing the sentence ‘It would be good if poverty were eradicated’ is closely related to valuing the proposition that poverty is eradicated. But we can also put this by saying: embracing the sentence ‘It would be good if poverty were eradicated’ is much like wanting or desiring the sentence ‘Poverty is eradicated’ to be true. … So there is a clear asymmetry between embracing an evaluative sentence and embracing the embedded descriptive sentence, an asymmetry that becomes apparent when a piece of practical reasoning is put into words.

It is possible, however, to represent this asymmetry in quite a different way. We have been considering [1] the contrast between embracing an explicitly evaluative sentence and embracing a descriptive sentence. But we could instead contrast two different attitudes, belief and desire, as directed to the same sentence (or proposition). This comes out as [2] the contrast between wanting ‘Poverty is eradicated’ to be true, and believing it to be true, or the contrast between wanting poverty to be eradicated and believing it has been. Which of these two contrasts [[1] or [2]] or asymmetries we take as basic will, I suggest, make all the difference to our study of the relation between valuing and language. Most studies of this relation concentrate on the first contrast [1], which depends on the use of explicitly evaluative sentences — sentences that ‘say’ that something is desirable or good or obligatory. Such an approach [1] encourages one of two distortions: either desire is seen as a special form of belief, a belief that certain states or events have a moral or other kind of value, or are obligatory, etc.; or evaluative sentences are thought to lack cognitive content. The first of these views makes evaluation too much like cognition; the second bifurcates language in an unacceptable way by leaving the semantics of evaluative sentences unrelated to the semantics of sentences with a truth value.Footnote 26

Here, it seems to me, Davidson is saying that contrasting embracing an evaluative sentence with embracing a descriptive sentence leads people to think of the former as just a special form of belief or to deny that evaluative sentences have content. Those are the two distortions. So I don't think he is here saying that evaluative sentences don't express pro-attitudes or that it is a distortion to identify normative beliefs with pro-attitudes. Instead, it seems that he is concerned with the question of how to characterize an asymmetry that is expressed in one way with the contrast between embracing evaluative sentences and descriptive sentences. On the previous page, in fact, he says, “We understand a person when we are able to explain his or her actions in terms of intentions, and the intentions in terms of beliefs and evaluative attitudes.”Footnote 27 Here, the expression ‘evaluative attitudes’ is slotted into the position of ‘pro-attitudes’ in earlier writing. Further down the page, he writes:

On the one hand, we may think of a person who puts a positive value on the eradication of poverty as embracing or accepting the sentence ‘It would be good if poverty were eradicated’. Embracing or accepting an evaluative sentence is to valuing what holding a descriptive sentence true is to belief. In fact there seems no reason not to use the words ‘embrace’ or ‘accept’ in both cases: to embrace an evaluative sentence is to value a certain proposition; to embrace a descriptive sentence is to believe a certain proposition.Footnote 28

If ‘evaluative attitudes’ is standing in for ‘pro-attitudes,’ and putting a positive value on the eradication of poverty or valuing a proposition is an evaluative attitude, then this seems to show that Davidson thinks that to have a pro-attitude is to embrace an evaluative sentence. Plausibly, embracing an evaluative sentence is being willing to utter it sincerely. So a sincere utterance of ‘It would be good if poverty were eradicated’ is an expression of a pro-attitude towards eradicating poverty. The point of the passages following this (the ones first quoted from above) seems to be to urge that we can shift from this way of drawing the contrast to talking of desiring or believing a sentence true. It is not that it is a mistake but that it can be misleading. This reinforces the impression that evaluative sentences are to be thought of as expressing pro-attitudes. For what now goes proxy for embracing an evaluative sentence is desiring a descriptive sentence to be true. So far as I can tell, nothing in the rest of the essay contradicts this. Notably, the passage concerned with shared values starts with, “As with belief, so with desire or evaluation.”Footnote 29 So here at least it is clear that he is arguing that it is shared desires that are required for interpretation — evaluations are expressions of them. This also fits the manner in which he argues because the main novelty is integrating Bayesian decision theory into the interpreter's practice, which requires simultaneous assignment of contents to beliefs and desires. At the end, he adds this:

But what about explicitly evaluative sentences, sentences about what is good, desirable, useful, obligatory, or our duty? The simplest view would be, as mentioned before, to identify desiring a sentence to be true with judging that it would be desirable if it were true — in other words, to identify desiring that ‘Poverty is eradicated’ be true [which rests on a desire that poverty be eradicated] with embracing the sentence ‘It is desirable that poverty be eradicated’. And it is in fact hard to see how these two attitudes can be allowed to take entirely independent directions. On the other hand, there is a point to having a rich supply of evaluative words to distinguish the various evaluative attitudes clearly from one another: judging an act good is not the same as judging that it ought to be performed, and certainly judging that there is an obligation to make some sentence true is not the same as judging that it is desirable to make it true. For these and further reasons, there is no simple detailed connection between our basic preferences for the truth of various sentences and our judgments about the moral or other values that would be realized if they were true.Footnote 30

However, he is not saying here that evaluative sentences, when embraced (when one is willing to utter them sincerely), do not express pro-attitudes, but only that desire is not always the right evaluative attitude (the right pro-attitude) to associate with an evaluative sentence. One might wonder about his saying that “it is hard to see how these two attitudes can be allowed to take entirely independent directions.”Footnote 31 Is this the suggestion that the evaluative judgements constrain the pro-attitudes? But this doesn't fit how he goes on, where the point is that there are different evaluative attitudes (pro-attitudes) expressed by different evaluative words, and it does not fit with the earlier discussion in the same paper. So on balance it seems to me that these passages in “Expressing Evaluations” support the view that Davidson has not changed his mind between 1978 when “Intending” was published and 1984 when “Expressing Evaluations” was published. Is there evidence that he had a change of mind in later papers?

The second consideration draws on a passageFootnote 32 from “The Problem of Objectivity” first published in 1995.

I come now to some further aspects of holism: intra-attitudinal and inter-attitudinal. The first concerns the relations among the various beliefs, within the category of belief, or the relations among desires, within the category of desire. The second concerns the relations between one category of thought or judgment and another: for example, the relations between beliefs and desires.Footnote 33

The question is what is meant by holistic intra-attitudinal constraints among desires as opposed to beliefs. Unfortunately, although Davidson goes on to give examples of holistic intra-attitudinal constraints for beliefs, he does not give any examples for desires. Myers suggests that if we take a Humean view of pro-attitudes, it could not come to much. This might be a reason to think that Davidson rejected a Humean view of the pro-attitudes. But, first, it is not clear that rejecting a Humean view helps with intra-attitudinal holistic constraints because what that seems to get us, on the non-Humean view that Myers champions, is inter-attitudinal constraints. And, second, there may be some plausible candidates for holistic intra-attitudinal constraints on a Humean view. First, there is the requirement that desire be ranked (which can in general include ties), but more specifically that desires whose contents conflict outright be ranked strictly so that one is preferred to the other. Second, there are rationality requirements on preferences, such as transitivity. Third, it is plausible to require that if one desires one thing and one knows another thing is required for it, one desires in that respect the other thing. If we extend the thought to all pro-attitudes including intentions, then we get further intra-attitudinal constraints since intentions are constrained to be consistent with one another and obey principles like Michael Bratman's agglomeration principle: if you rationally intend to A and rationally intend to B, you can rationally intend to A and B.Footnote 34 Did Davidson intend more than this? It is hard to say, but it does not seem to me that we need to appeal to a non-Humean theory of pro-attitudes to make sense of what he says here.

6. Afterthoughts

One might say: fine, it is unclear whether Davidson endorsed the non-Humean view. But it is not inconsistent with general Davidsonian principles. And it could be combined with a commitment to decision theory as a framework for understanding action with the proviso that normative beliefs are to be conceived of as having their content fixed independently and the system of pro-attitudes constitutively aim at a world endorsed by normative belief. I think one might still worry about the argument for shared norms, at least norms beyond those of practical and theoretical rationality.

First, it is not clear that normative beliefs about particular actions or events or states of affairs are direct responses to properties of goodness or badness or rightness or wrongness of objects in the environment, and it is not clear that they have to be for us to understand others as having normative beliefs. Often, when we judge some particular thing to be wrong, it is because we bring to bear a principle that applies to the case. Sticking pins in people is wrong because it causes harm. The moral principle is not to cause gratuitous harm to any moral agent or moral patient. The properties we respond to are pin pricks and harms (if ‘harm’ is a moral term, we can replace it with one more purely descriptive). The badness of the action is derived from that and the principle. So we don't get, I think, the conclusion that most of someone's normative beliefs are true on the grounds that filling in the content of the concept of good or bad (along whatever dimensions are relevant) requires triangulating on those properties in particular. We can think of them rather as functional concepts in the sense that those who deploy them allow principles in which they are used to guide their behaviour in certain ways. But we have relatively free play with what the principles are in which those functional concepts are deployed. So we could find the same functional concepts deployed in relation to different properties in the world than we deploy them in response to, and so interpret others as having normative concepts of various sorts but employing them in different principles. It is hard to see why this would block successful interpretation. One might argue that the relevant normative concepts we deploy are not like that, but that they are not like that doesn't fall out of the methodology of interpretation. It would need an independent argument.

Second, there are sociopaths who have little use for many of our normative concepts, except to keep track of what we are likely to do given what we say. We can easily imagine a group of them retiring to an island to run a society in accordance with sociopathic principles. They would not have any use for many of our normative concepts. Suppose that their children are also sociopaths (maybe it is genetic, maybe cultural). Over the generations, they lose most of the normative vocabulary that we use. I submit that there would be no very great difficulty in interpreting them upon reestablishing contact. But we would not find them sharing normative beliefs with us except for those having to do with prudential and epistemic rationality. So, again, sharing normative beliefs beyond those pertaining to rationality does not appear to be a requirement on interpretation.

In the first case, this is because we can imagine interpreting people with different principles, locating the concept by its functional role; in the second case, this is because we can imagine interpreting people who simply lack many of the normative beliefs we have because they don't share the concepts with us.

7. Summary

There were two main issues I raised concerning the triangulation argument. The first is about the role of [Determination] in the argument. It looks as if it stands in need of an argument. I think Davidson gave one. But that needs a defence of the thesis that language is required for thought. But that seems to require the conclusion that linguistic triangulation is the only context in which the concept of objectivity can be deployed. But that rests on [Determination]. So we have a dialectical circle, and this one looks like it leaves everything hanging in the air. The second is whether there is a crucial addition to the objective facts in the case of a pair as opposed to a solitaire that makes determinate thought and possession of the concept of objectivity possible. I suggested that if we find that a solitaire's embedding in her environment did not provide enough structure to fix determinate (enough) thought contents in the sense that there were possible interpretations that were too far from the canonical, then it is plausible that we could construct equally radical interpretations for pairs.