I

Since the advent of steam mobility in the 1830s every major innovation in transport and communication has consistently been either acclaimed or repudiated for reducing distance, shrinking the world, or even annihilating space altogether. Descriptions of the effects of the railways, the telegraph, or, a century later, of electronic telecommunications or Boeing 747 jumbo jets and supersonic planes flying over the Atlantic, might seem to be part of a similar historical process of increasing speed and mobility, and shrinking distance. In its most recent incarnation, this narrative of spatial annihilation has become a popular refrain in the growing literature on globalization; common slogans such as ‘cyberspace’, ‘global village’, and ‘flat world’ all draw upon this supposed historical narrative of the ‘death of distance’.Footnote 1 This article reacts to the permeation of this language of space reduction into the social sciences, and especially when it comes to the historical understanding of transport technologies.

As noted by Koselleck, the concept of space reduction comes in two versions: one is experiential – alluding to the perception and formulation of changing experiences of space by individuals and social groups in the past – while the other is willingly anachronistic and speculative, relying on historical, sociological, technological, environmental, or political meta-narratives of which people living at the time might not have been aware (say, climate change) or were unable to conceive (say, economic growth). The second version of the concept relies on a more structural understanding of space, as a function of, or a medium for, historical change. This version is, for example, what lies beneath analyses of past ‘waves of globalization’ defined in terms of the share of exports in world GDP, or of market integration measured by the speed at which prices adjust to shocks at different places in an economy, in both cases space being compressed as the result of the increasing circulation of goods and a higher degree of economic connectedness, regardless of the experience of contemporaries.

There is little to object to in Koselleck's distinction between the two versions of the concept – no nominalism in historical science – but it also comes with risks: in particular, it could give the impression that the two versions are somehow genetically related and that the experiential notion is a precursor of its analytical counterpart. My argument is, instead, that there is an unbridgeable gap between the two uses of the term, and that scholars interested in experiences of space as a historical phenomenon should not conflate or attempt to project one onto the other. It is neither possible to derive the subjective experience of space from metrics describing the conditions of these experiences (a higher degree of connectivity and increased speed do not necessarily lead to the perception of a smaller world), nor suitable – pace most postmodern human geography, including phenomenological, post-phenomenological, and non-representational geography – to use psychological descriptors (the perception of shrinking space) to analyse changes in economic history/geography.

Koselleck, though, clearly believes in this temporal articulation. This is because, according to him, space reduction can be treated as the experiential counterpart, ‘the benchmark’, of social acceleration, which itself is not an experiential concept but a ‘utopian concept of expectation’ and ‘an indicator of a specifically modern history’.Footnote 2 The slip here from the experiential to the speculative and the historical via the narrative of modernity seems to me like kicking the can down the next conceptual alleyway. What one should make of his claim that ‘only in the wake of the French and Industrial Revolutions did acceleration [experienced as shrinking space] begin to become a universal principle of experience’ remains – possibly because of the misleading translation – something of a mystery to me.Footnote 3 Spatial reductionism (in the experiential version) might not be spatially comprehensive (it does not apply to the same extent everywhere) and might have its own historicity (it develops at different rhythms), but it cannot, at any rate, pretend to be universal. Inversely, as a speculative concept (or a form of periodization), it cannot be a ‘principle of experience’. I agree with Koselleck that space reductionism must be historicized, but I cannot understand what would make it fundamentally more experiential than acceleration, or inherently modern. Most of what he diagnosed about acceleration could be said about space reduction, too: it is ‘not a shrinking of space but in space’. Hard evidence for the subjective experience of shrinking space is non-existent (neurosciences) or largely unrepresentative from a quantitative point of view (cultural studies, literary analyses, and phenomenological geography). A few quotes – even many of them – praising or bemoaning the effect of the railways barely scratch the surface and the diversity of contemporary engagements with spatiality.

If we now agree to discard the link between the speculative and experiential versions, how much of the criticism of the notion of space reduction remains apposite to many of the non-philosophical twentieth-century uses of the term? My argument is that, whether as a metaphor or a descriptor, even when not offering a direct critique of modernity, or not intending to be normative, the notion of space reduction is rooted in political and historiographical traditions fundamentally engaging with the nature of modernity. Still, one may ask, could it not be employed as a purely descriptive turn of phrase, devoid of any political and cultural connotations? Yet, I do not think anyone has ever said ‘the world is shrinking’ as a simple factual statement, as one would say ‘it is raining’. In all my readings, I have not found one literary use of the trope that could be described as entirely trivial. It is always a symbolic engagement (be it indirect and through a hackneyed formulation) with the spatial and temporal effects of technological change.Footnote 4

Historians, perhaps more than any other group, should be reluctant to use it. Space reduction first crept into contemporary historical lingo through a branch of Marxist historiography of the industrial revolution and the Braudelian world history of economic integration and modernization. It re-emerged as a conceptual device in the cultural history of transport (Schivelbusch) and in essays concerned with the cultural history of modernity (Kern).Footnote 5 Space reduction seems now to be a legitimate shorthand for describing the effects of nineteenth-century improvements in communication and transport technologies (the holy trinity: steamboats, railways, and the telegraph), and it has cropped up in almost all historiographical genres concerned with these transformations: mobility studies, the cultural history of techniques, the economic history of commercial and financial integration, world history, and studies on globalization, together with all sorts of essays about the nature and culture of modernity. Does the prevalence of space reductionism in all these fields prove its validity and heuristic value? In the following pages I have tried to offer an intellectual history of the idea of space reductionism and to study the relationship between the experiential and speculative versions of the concept over time. This will clarify our own language – as historians – when talking about changing perceptions of space. My etymology of space reductionism covers its use as a nineteenth-century literary and visual trope, a proto-political economy of space, and a twentieth-century intellectual engagement with the nature of modernity.

II

Many commentators have linked the emergence of a discourse of space reductionism to what Leo Marx called ‘one of Pope's relatively obscure poems’, which was supposed to emphasize the divine or sublime effect of cancelling distance.Footnote 6 This origin is probably correct, but the meaning of the cultural reference has been totally misunderstood. Peri bathous or the art of sinking in poetry, which contains the couplet, was written in 1727 under the pen name Martinus Scriblerus and, like all the other works by members of the Scriblerus Club, it was a farce sneering at literary and philosophical mediocrity. The book was presented as a treatise on how to write bad poetry, and the couplet appears in the section devoted to hyperbole. Annihilation of space and time is used as an example of impossible, ridiculous, and overemphatic prose. In this case, Pope did not quote someone else's bad poetry but seems to have crafted the couplet himself, which suggests that it is a reference, a pun, directed at a contemporary philosophical controversy about the nature of space launched by Berkeley's 1710 Treatise concerning the principles of human knowledge. The latter claimed that space was merely an idea derived from experience and, hence, could easily be annihilated. This is most likely the hyperbole that Pope had in mind, and his sarcastic reference to the annihilation of space continued to exemplify poor writing in Britain at least until the 1820s.Footnote 7

In America, the metaphor became a literal epithet for industrial mobility during the early nineteenth century, especially in relation to steamboat navigation (see Figure 2).Footnote 8 After 1830 the expression came back to Europe: first with the rapid expansion of the railways, and then with the development of telegraphic communications after 1835–6.Footnote 9 By the late 1830s the trope seemed to have almost entirely lost its comical power and become part of the official jargon of modernization, with the full approval of the learned elite. In Liverpool, on 9 October 1838, the future prime minister Lord John Russell (himself a keen writer) very seriously ‘alluded to the recent improvements in communications from one part of the country to the other, and hoped that this annihilation of time and space, this bringing together of all interests into contact with each other would tend to harmonize all, and bring them to act together’.Footnote 10

By the late 1840s the expression had become a visual metaphor for the effects of steam mobility in Britain. Frederick Smeeton Williams's 1852 account Our iron roads is a telling example of this new trope:

the country may now be traversed from the South coast to the Borders in a few hours. The extremities of the island are now to all intents and purposes as near the metropolis as Sussex or Buckinghamshire were two centuries ago. The Midland counties are a mere suburb. With the space and resources of an empire we enjoy the compactness of a city.Footnote 11

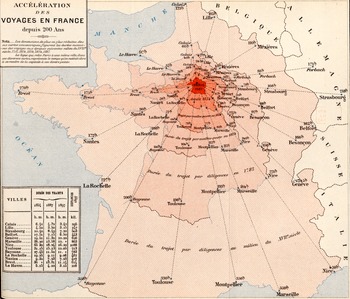

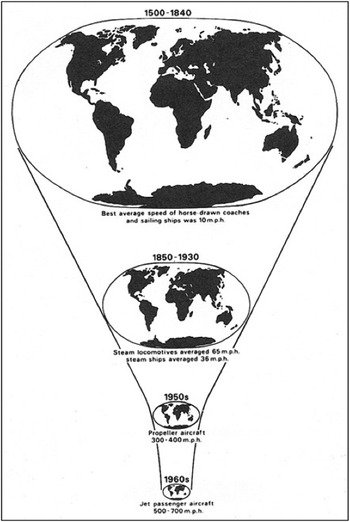

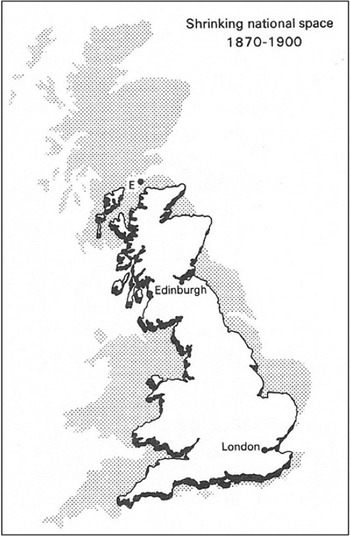

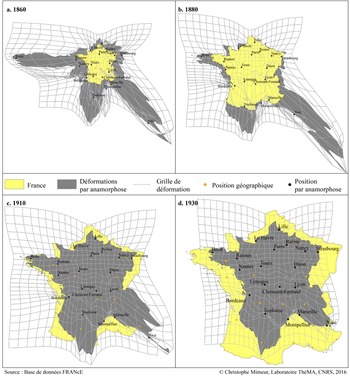

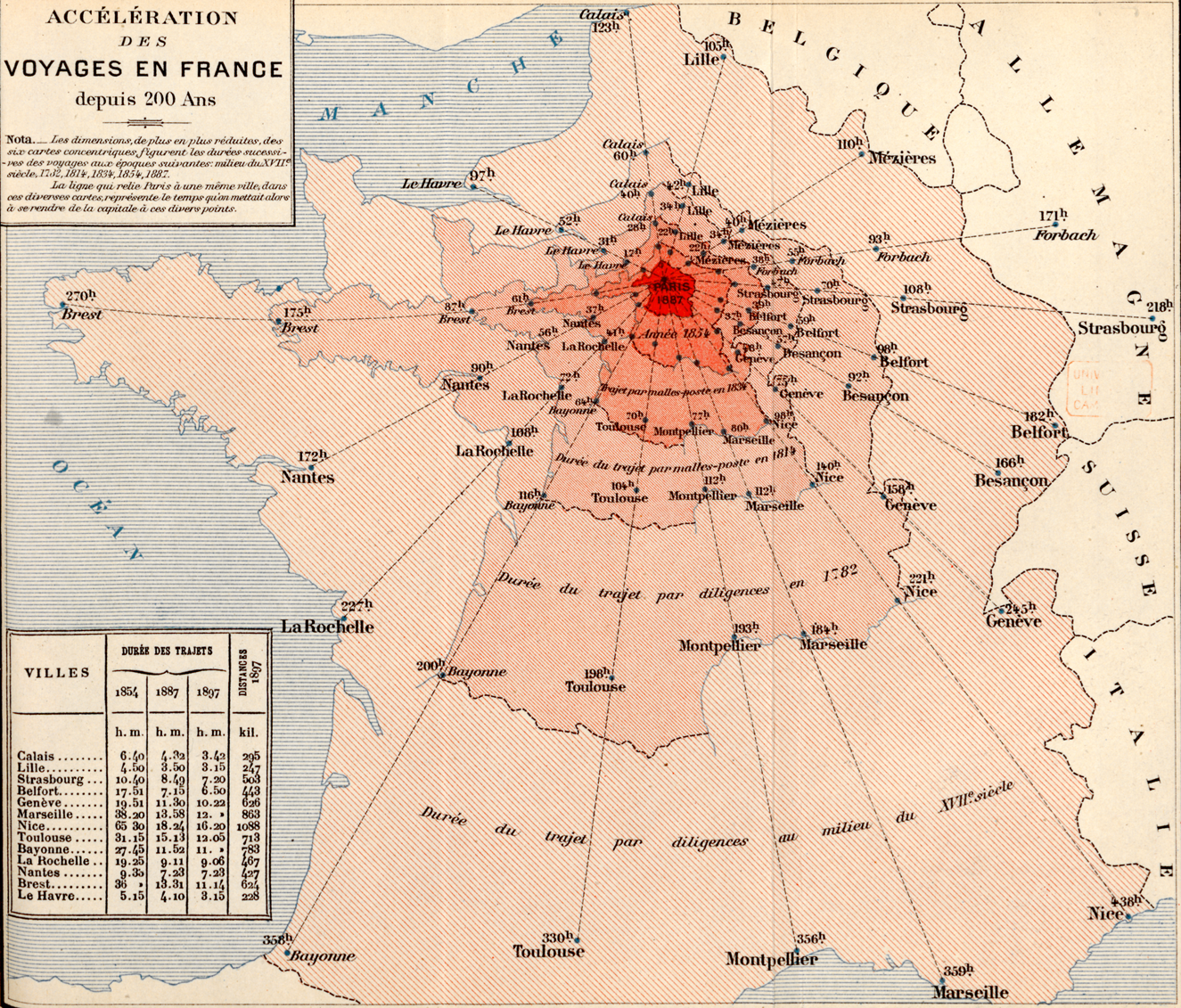

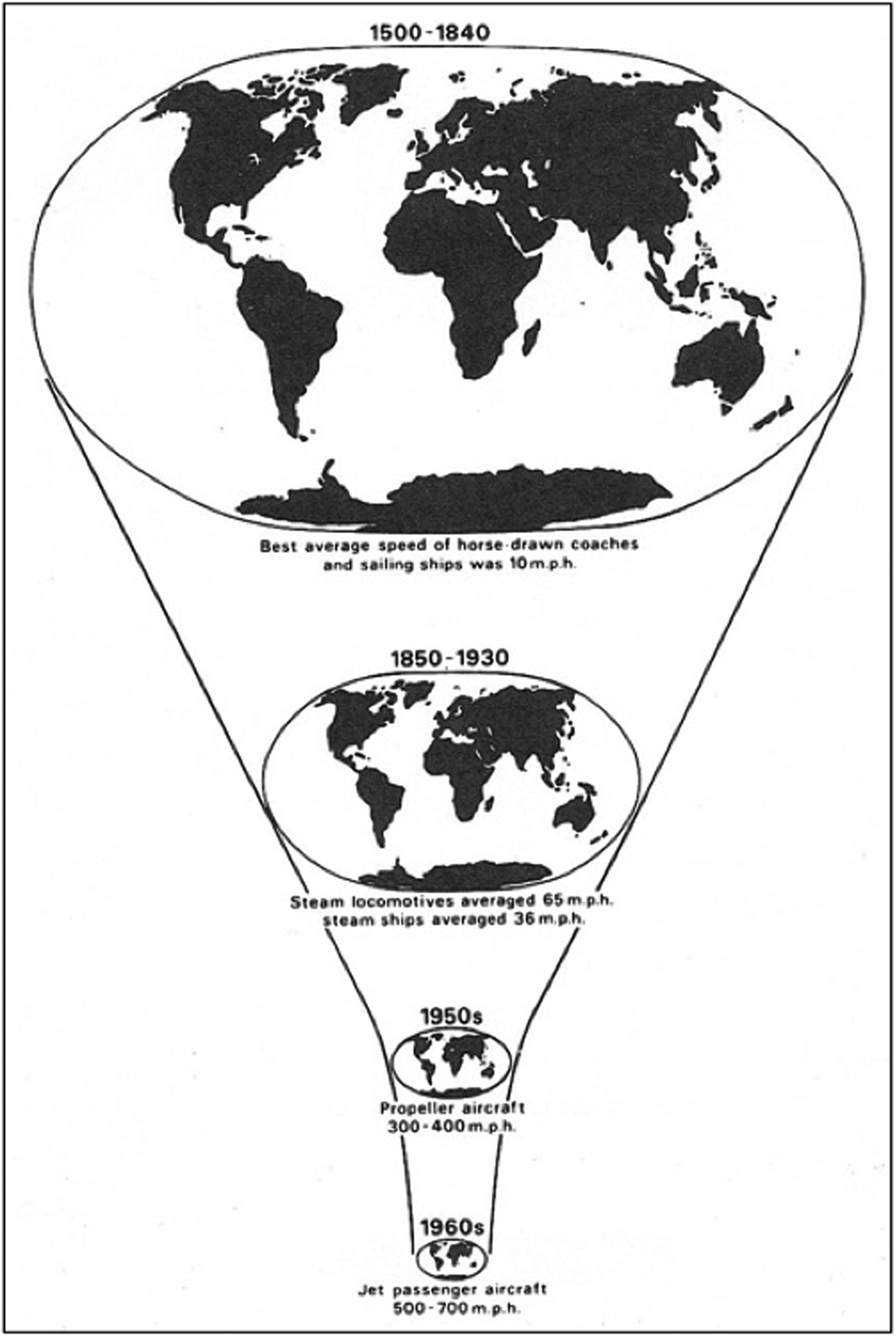

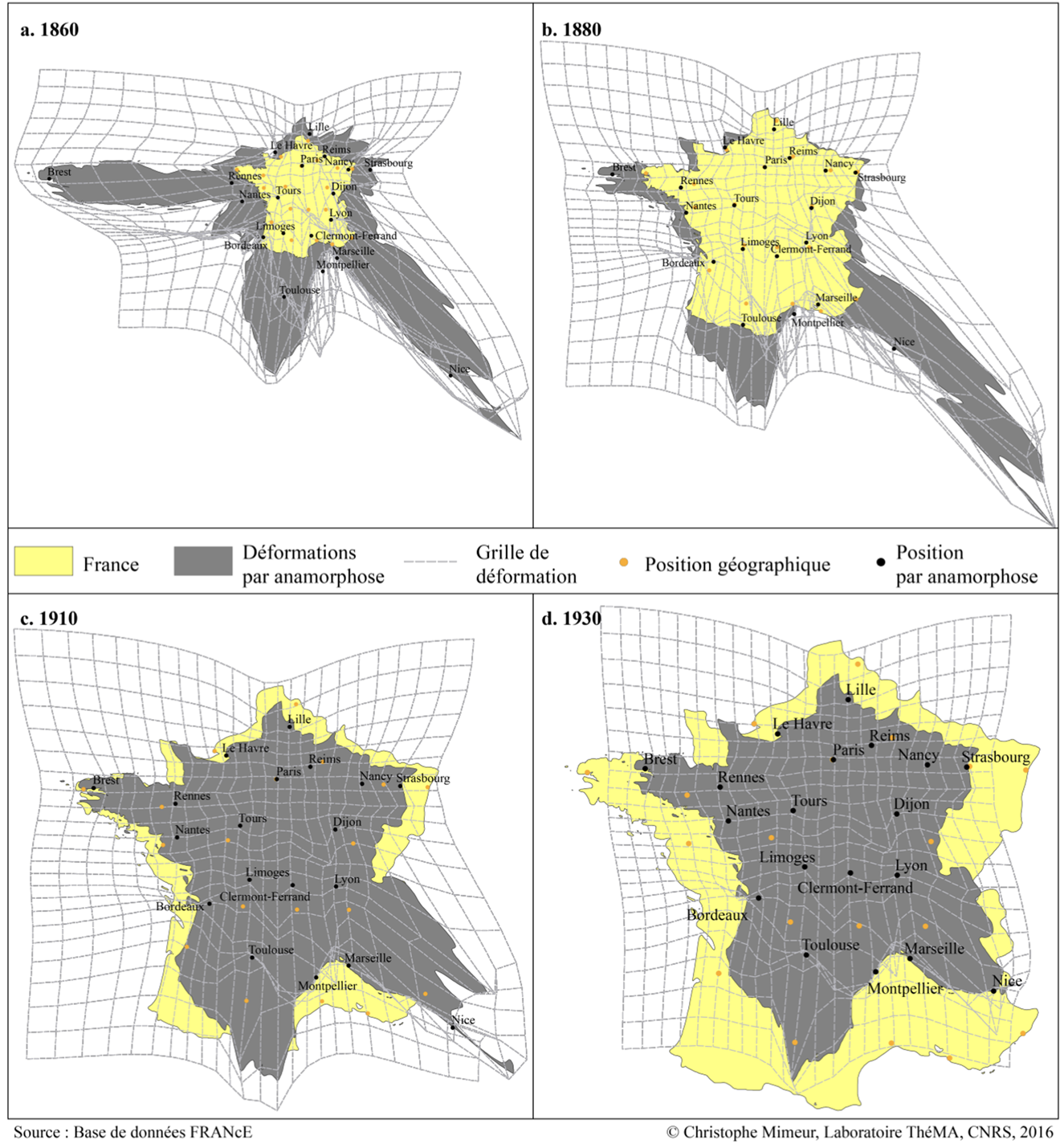

At the turn of the century, this literary image of a shrinking nation was supplemented by a corresponding iconography – first in academic and official publications and later in railway treatises and many kinds of economic and commercial pamphlets – which aimed at mapping the relative effects of the reductions in travelling time as a progressive compression of national space. Isochronic maps (showing journey times from a similar origin at different points in time) emerged as the topical representations of these effects of industrial mobility, delineating on the page, as it were, the compression of time-space (Figure 1.1).Footnote 12 For reasons that will become evident in the following sections of this article, these representations of relative space shrinkage enjoyed a great revival in the 1960s through the work of radical and humanistic geographers who wished to illustrate the relativity of spatial experiences (Figure 1.2), and then became a standard iconographic narrative of the effects of industrial mobility (Figure 1.3).Footnote 13 They are now staging another comeback in the visual culture of the social sciences with the help of GIS technology and the application of graph theory to transport network analysis (Figure 1.4). Complex anamorphoses (mathematical deformations) of geographies according to connectivity, accessibility, travel costs, or any other analytical metric have now become standard practice in geography, mobility, and planning studies, and, more recently, economic history.

Figure 1.1 Increases in travelling speed from 1650 to 1887.

Source: C. Colson, Transports et tarifs (Paris, 1898), p. 89.

Figure 1.2 Stages of space compression.

Source: D. Harvey, The condition of postmodernity (Oxford, 1990), p. 241.

Figure 1.3 Shrinking national space, 1870–1900.

Source: M. J. Freeman, ‘Transport’, in J. Langton and R. J. Morris, eds., Atlas of industrializing Britain, 1780–1914 (London, 1986), p. 90.

Figure 1.4 The effects of railway accessibility in France.

Source: C. Mimeur, ‘Les traces de la vitesse entre réseau et territoire: approche géohistorique de la croissance du réseau ferroviaire français’ (Ph.D. thesis, Dijon, 2016), p. 268, http://www.theses.fr/2016DIJOL028/document.

III

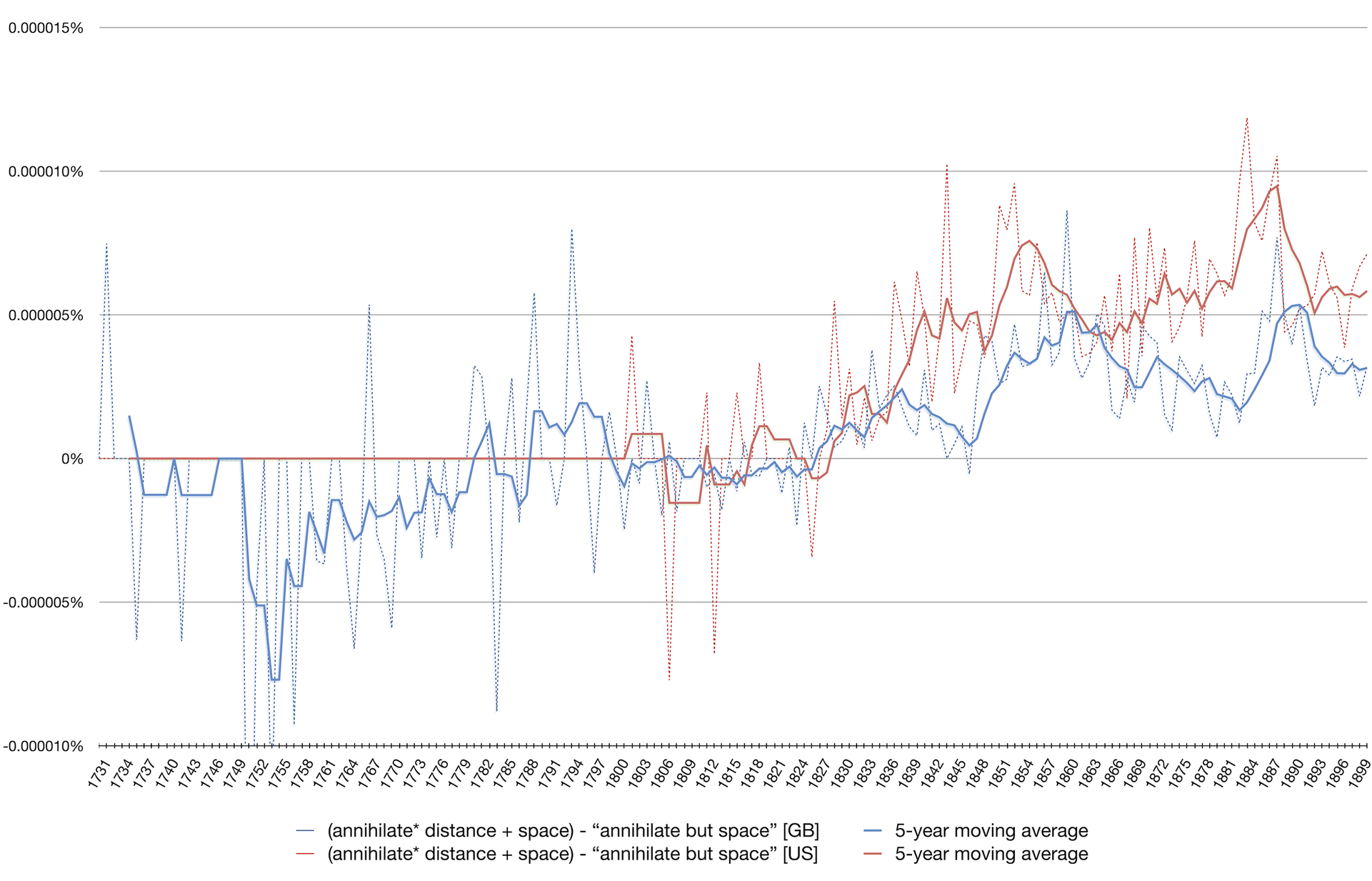

The qualitative shift in the way that the expression ‘annihilation of space’ was perceived was accompanied by a substantial increase in popularity in the 1830s (Figure 2). The term also began to convey a new emphasis on the historical and social effects of this shrinking of space that did not come from America but resulted from contemporary intellectual developments on the continent, leading to the emergence of a political economy of space reductionism. When spatial annihilation was mentioned in this context, it was always as the overcoming of a physical obstacle, which was hailed as a key, tangible realization of progress in universalizing history. For this reason, the early nineteenth-century political economy of spatiality was in its foundation essentially negative, mechanistic, and idealist: it required the management of nature to abolish worldly friction. But it did not champion human mobility. On the contrary, by shrinking space, the need for migrations (always politically and economically suspect) would be reduced. In this world of absolute commuters, rootedness was protected by easier and more affordable travel, while ideas and goods could spread unconstrained.

Figure 2 Diffusion of the ‘annihilation of space’: from a derogatory expression to a metaphor of industrial mobility. The graph plots the difference in relative frequency between all expressions based on the root ‘annihilate distance’ or ‘annihilate space’ and the verse from Pope ‘annihilate but space’ in all British and American publications included in the 2012 revised version of the Google Books database, complemented by the EEBO, EECO, and British Library datasets. For a description of the methodology, see A. Litvine, ‘The industrious revolution, the industriousness discourse, and the development of modern economies’, Historical Journal, 57 (2014), pp. 531–70.

The emergence of a political economy of spatial compression can be traced back to Saint-Simon's late work on what he called the âge industriel. This hailed improvements in transport and communication as a practical means of achieving economic welfare and international peace. By willingly turning Adam Smith's famous argument on commercial interest on its head, Saint-Simon argued that the more the new classes of industrialists could travel and communicate, the more old borders and rivalries would become useless, up to the point where nations would disappear entirely. Although Smith and Hume were pessimistic about world peace, Saint-Simon argued that it would derive from industrial spatial unity, space reduction, and mobility.Footnote 14 This eccentric French aristocrat was certainly not the originator of these ideas – most of which had been debated since the 1770s in Europe – but the importance of his work relied perhaps more on its messianic message and on the identity of his followers than on its real intellectual content. In practice, Saint-Simonism took the form of an unlikely conglomeration of industrialists, engineers, and pioneering social scientists, who contributed to the forging of the first ‘institutional’ discourse on the civilizational merits of space compression.Footnote 15 This vague but fashionable political economy of space, brought to life under the aegis of Auguste Comte's positivism (Comte having once been Saint-Simon's secretary), found a direct echo in three more discourses that emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century: sociology, social and human geography, and the Marxian critique of spatial annihilation.

Marx's conceptual reworking of space reduction can be found in a manuscript written between 1857 and 1861, known as the Grundrisse der Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Although it is by far the most influential text and, perhaps even the raison d’être of this article, the Grundrisse had no immediate intellectual filiation during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as it remained unpublished in western Europe until the late 1950s, and only became widely available when it was translated into English in 1973.Footnote 16 For this reason, until the 1970s spatial annihilation remained for all practical purposes – scientific and journalistic – coterminous with spatial compression. We will see in the following section how geographers then picked up Marx's conceptual footwork and combined it with phenomenological theories of space to create two separate understandings of the concept.

The Grundrisse is Marx's effort to combine the Saint-Simonian teleology of unification with Hegel's ontology (and dialectical negativity) of space.Footnote 17 In it, Marx clearly states that the driving force behind the historical process of annihilation of space was inherent to the expansion of capital itself. David Harvey (with the benefit of hindsight, having read the Grundrisse) was one of the first scholars to stress the centrality of Marx's overlooked coda to the first volume of Das Kapital on the theory of colonization. He noticed that the chapter revealed the spatial dynamics and the contradictions of capital accumulation. Expropriations during the agricultural revolution required a first ‘spatial fix’, which was the ‘creation of the home-market for industrial capital’, but, when this internal expansion was achieved, capitalist accumulation had to find new horizons: that is, towards the colonies.Footnote 18 This always-renewed need for a spatial fix was what drove the progressive annihilation of all barriers to trade, and eventually space itself.

Marx in this way transposed the Hegelian dialectics of space to his analysis of economic development. On the one hand, creating the internal market by transforming independent producers into wage earners was a direct consequence of the accumulation of capital, but, on the other hand, as soon as the market entered this relationship the relative immobility of labour became incompatible with the mobility of capital required to pursue accumulation elsewhere. The industrial mobility of labour thus became the consequence of a progressive deskilling and subjection of workers to the mobile nature of capital, and:

while capital must on one side strive to tear down every spatial barrier to intercourse, i.e. to exchange, and conquer the whole earth for its market, it strives on the other side to annihilate this space with time, i.e. to reduce to a minimum the time spent in motion from one place to another. The more developed the capital, therefore, the more extensive the market over which it circulates, which forms the spatial orbit of its circulation, the more does it strive simultaneously for an even greater extension of the market and for greater annihilation of space by time.Footnote 19

Despite the omnipresence of this formulation in recent historiography, the Grundrisse remained an intellectual dead end and, at least until the 1970s, the history of space reductionism was mainly influenced by the emergence of two academic traditions in the late nineteenth century: namely, sociology and geography.

Durkheim was one of the first sociologists to address the question of the nature of ‘space’ in the newly institutionalized discipline. He wanted to reject the Kantian ideal and homogeneous model of space in favour of space conceived as a social datum: that is to say, as the manifestation of cohesive society. Although each society engenders its own spatiality, and so different ways of constructing space cohabit, Durkheim insisted that social heterogeneity does not lead to purely individual experiences of spatiality, for space remains inherently holistic. This is how one should read his claim that ‘all individuals from a similar civilization have a similar conception of space’.Footnote 20 Merging this holistic conception of space with the historicism inherited from the Saint-Simonian teleological narrative (‘space as progress’) led to a gloomier, socio-biological Darwinian conclusion. In De la division du travail social, Durkheim argued that contradictory representations of space tended to be resolved, or rather unified, in a historical process of contacts, conquests, and domination made possible by technological change. This progressive homogenization of space conditioned by the reduction of distances, he continued, would eventually lead to the disappearance of spatial categories as means of differentiation in favour of new forms of violent struggle between individuals based on labour specialization.Footnote 21

In this respect, Durkheim did not differ as radically from Spencer as he would probably have argued. The latter also associated the expansion of economic relations with a progressive unification (hence reduction) of space associated to a strongly racialized conception of spatial homogenization. For Spencer, the domination (financial, economic, military, or otherwise) of propertied white European men over large swathes of the world consecrated a superior form of global consciousness based on ‘the difference between the proprietary feeling in the savage, responding only to a few material objects adjacent to him … and the proprietary feeling in the civilized man, who owns land in Canada, shares in an Australian mine, Egyptian stock, and mortgage-bonds on an Indian railway’.Footnote 22 This perhaps too clearly and sadly illustrates the point made by Subrahmanyam that ‘the awareness of globality … had severe consequences for indigenous populations’ around the globe.Footnote 23 For Spencer (as for Durkheim), the historical annihilation of contradictory spaces was neither a metaphysical category nor the sum of individual representations and experiences, but the result of a progressive annihilation of weaker (that is, non-western European) forms of spatiality.Footnote 24

A second important sociological conceptualization of space took place roughly at the same time in Germany, with Georg Simmel's 1908 essay on ‘The stranger’.Footnote 25 This attractive reformulation of social distance as the interaction of physical and psychological distance applied to figures such as the migrant (someone from another place) and the marginal (in the space but not of it) and became extremely influential in the early development of a critical social psychology of estrangement. The resulting critique of urban uprootedness created by large-scale industrial mobility became a defining feature for many German intellectuals, ranging from the Frankfurt School (starting with Simmel's own students: Benjamin and Kracauer) up to Heidegger, and was also adopted by the Chicago school of sociology in the 1920s.

Geography as an academic discipline also emerged in the nineteenth century, and was informed by a very similar language, resulting from the conjunction of social holism and spatial entelechy. Both Retzel's Anthropo-Geographie in Germany and Vidal de La Blache in France grounded their geographic and geopolitical analyses in the confrontation between two contradictory processes.Footnote 26 The first was a reduction in physical space due to technological improvements – or, as they both called it, ‘a transformation of the scale of the world’ – and the second was the need to increase national space to sell new industrial products.Footnote 27 Although the institutionalization of geography was slow in Britain compared to France and Germany, Jonathan Murdoch has recently shown that the metaphor was also a tenet of British humanistic geography from ‘the beginning of the twentieth century, [when] A. J. Herbertson (1915) talked of the “annihilation” of space and time by new technologies of transportation’.Footnote 28 As the narrative of space reduction seemed to intuitively fit the descriptive, historical, economic, and political dimensions of spatiality within the imperial mentality and the pragmatic management skills required for colonial administration, it became a central plank of British geographic discourses, and even served its pretensions in the context of increasing academic institutionalization.Footnote 29

Building upon this success, early twentieth-century historians eagerly adapted the spatial framework of geography and sociology to historical discourses. Following in particular François Simiand's seminal article of 1903, ‘Méthode historique et science sociale’, the École des Annales adopted Durkheim's and de La Blache's conception of space.Footnote 30 Spatial reductionism was both the methodological key of the sort of global social science that historians such as Fernand Braudel had been longing for, and seen as the practical result of a longue-durée evolution of the structures du quotidien, culminating in the advent of modern spatiality.Footnote 31 In 1986, Bernard Lepetit, also a member of the Annales school, analysed Braudel's spatial framework, concluding that ‘spatial reduction is the condition of possibility for any comparative history and even for the integrated practice of social sciences that Fernand Braudel called for’.Footnote 32

During the 1920s and 1930s, however, the grand holistic narrative inherited from the sociological and historical traditions came under fire from philosophers for its inability to account for the very process of perception through which any theory of space and time should derive. The most virulent onslaught began in 1927, when Heidegger took over the idea of spatial experience in Sein und Zeit (Being and time) to give a radically different formulation of the relationship between the self and its environment. What was before both a poetic licence (a trope) or a visual metaphor (a shrinking map) and a justification of European imperial domination, now became the centre of his conceptualization of space.

IV

Heidegger essentialized the relationship between existence and location by giving an ontological status to the notion of place or, as he put it, to the fact of ‘being-in-space’. What he perceived as the historical phenomenon of space compression and homogenization, induced by technological change and its philosophical corollary, technological nihilism, therefore threatened to blur this essential distinction between spatially rooted existence and the weak and overstretched experience of ‘being’ (Dasein). In section 70 of Being and time, Heidegger had famously argued that spatiality could be derived from temporality, thereby relegating the experience of space as secondary to Dasein's innate temporality.Footnote 33 This (somewhat unhelpfully) conflated the two issues of space reduction and the speed-up of human relations, but, as shown by Casey in his 1962 essay ‘Time and being’, Heidegger later explicitly rejected this claim and reconsidered the foundational role of human spatiality over temporality.Footnote 34 This revaluation of space logically buttressed his negative conception of spatial reduction as both decadence and psychological trauma in all his post-war writings, such as the 1959 collection of essays On the way to language:

All distances in time and space are shrinking … Yet the frantic abolition of all distances brings no nearness; for nearness does not consist in shortness of distance … Everything gets lumped together into uniform distancelessness. How? Is not this merging of everything into the distanceless more unearthly than everything bursting apart?Footnote 35

It is important to note that even the later Heideggerian ontological reformulation did not wholly reject the premises of geographical holism inherited from early twentieth-century geopolitical sciences. Heidegger argued that Germany, ‘as a historical people, must transpose itself – and with it the history of the West – from the centre of their future happening into the originary realm of the powers of Being’.Footnote 36 A by-product of industrial transport and communication technologies, time-space compression is also understood as a historical phenomenon that puts growing pressure on Europe, and especially on the ‘squeezed German Dasein’, to occupy the historical place ‘befitting its destiny’.Footnote 37 As a careful rejoinder, it is fair to distinguish between Heidegger's ‘provincial’ or localized understanding of what Germany's historical place should have been, which derived from his very rejection of industrial mobility, and the contemporary Nazi expansionism and arms race that Heidegger (although very discreetly indeed) criticized for being a mere prolongation of the same decadent and technological worldview.Footnote 38

The consequences of the Heideggerian reformulation are threefold. First, it embodied a widespread disillusion and even a moral rejection of mobility in the second half of the twentieth century. Hannah Arendt, a student of Heidegger in Freiburg, criticized the uprooting effects of modernity and industrial technology, which, according to her, unleashed the most nefarious power of totalitarianism by creating its audience: accursed masses. This gave birth to a tradition of anti-modernist thinkers recruited equally from the right and the left, who – although not always consciously – also drew upon Heideggerian phenomenology to repudiate the idea of mobility.Footnote 39 These phenomenological heirs of the duke of Wellington include recent contributors such as Finkielkraut and Sloterdijk and, on the other side, the denigration of mobility and commodification, which has been perpetuated with great success among historians through 1960s British Marxist cultural studies inspired by E. P. Thompson and Raymond Williams.Footnote 40

Secondly, this philosophical reformulation of experiential space became the foundation of a phenomenological and humanistic turn in the social sciences and contributed to the definitive blurring of the divide between the experiential and interpretative versions of the concept. It first found an echo among French phenomenologists of the 1960s and 1970s, especially through the work of Merleau-Ponty.Footnote 41 It is true that not all phenomenologists influenced by Heidegger were obsessed by space compression (like Casey, for example), but the material construction of perception and its social diffusion became one of the most important subjects of reflection for thinkers such as Lefebvre, Deleuze, Guattari, Levinas, and Derrida, and for the growing fields of urbanism, spatial sociology, phenomenological geography, and psychiatry (Minkowski), and existentialist (Sartrean) psychology. In the then burgeoning field of humanistic geography, Bachelard and Virilio (both former students of Merleau-Ponty) were central in imposing a place-based vision of human experience defined with terms such as rootedness and authenticity.Footnote 42

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a third line of enquiry has drawn upon the Heideggerian formulation to denounce the effects of industrialization and unlimited mobility on the environment. It would be unrealistic to go into the details of the expanding field of environmental humanities, but suffice it here to say that the critique of spatial reductionism will sound familiar to all readers of Jonas's The imperative of responsibility, and that, as environmental issues have finally been embraced by most social sciences, the neo-Heideggerian intellectual framework from which environmental ethics originated has given credence to the historical and epistemic validity of spatial annihilation, and – perhaps ironically – made it acceptable as a progressive, liberal, and environmental turn of phrase.Footnote 43 Yet, since the publication of The imperative of responsibility, our understanding of the impact of human activities on climate change has greatly improved, and a new global awareness of natural, social, and economic disasters – not least a literal shrinkage of habitable space caused by rising sea levels – has made even more implausible this use of ‘spatial annihilation’ as an environmental concept. Far from being annihilated, our incessantly travelled space has become the very nexus of the environmental emergency of the Anthropocene, as both its material proof (by documenting, for example, climate history through geological samples) and its crime scene (loss of natural habitat and sustainable ecosystems).

Because of this triple filiation (critique of the Enlightenment, phenomenological, and environmental), spatial reductionism, newly dressed as a humanistic concept, survived unscathed the temporary dismissal of its intellectual props in the aftermath of the Second World War. Amazingly enough, not only did it remain a constant feature of spatial analysis even when the notorious term Lebensraum had become unpalatable and geopolitics had been declared scientia non grata, but it went so far as to become a motto or catalyst of the phenomenological turn in geography. The main challenge for geographers and historians was to consider the construction and experience of space in order to balance the materialist premise of what they considered old-fashioned, deterministic, and potentially dangerous geography. To do so was like walking a tightrope: they needed a malleable (sensitive to human experience) and technically oriented concept of space, but at the same time it could not question space as a fundamental category of understanding – that is, the mere possibility of geographical discourses. The idea of the extension or reduction of space thus enjoyed a revival; it was flexible enough (as the experience of space determined by available technologies could be said to have a deforming effect) without abolishing objective spatiality altogether. This protracted continuation of spatial reductionism was nevertheless revealing of a certain conceptual unease in late twentieth-century human geography that emerged from the axiomatic distinction between ‘space’ and ‘place’.

Yet, the above dichotomy had already become largely artificial as it failed to encompass most modes of spatiality revealed by phenomenological approaches. Perhaps, because it was so embedded in geographical traditions and perceived as one of the historical legitimations of the discipline, it was not immediately challenged. On the contrary, it dutifully served to reproduce Durkheim's intellectual trick whereby the heterogeneity of space was subsumed under a positivist historical narrative. This is particularly striking in Donald Janelle's contributions in the 1960s in which, despite outlining very diligently the experiential and the non-experiential dimension of space reductionism, he described the paradoxical historical combination of shrinking space and extended spatiality in terms that abolished this distinction. On the one hand, he posited that ‘human extensibility’ – that is to say, the range and the complexity of spatial experiences – had greatly increased, but, on the other, he perceived a historical stage of ‘time-space convergence’ in which some places moved ‘closer’ together as travel times diminished.Footnote 44 Space reductionism serves both as an unquestionable epistemic foundation and as a metaphorical trump for ‘stabilizing’ an intellectual field which had become dizzy under the influence of the often undecipherable postmodern critique. It levels the ground and recreates a ‘space’ in which geographers can work.Footnote 45

Postmodern theory has played a great role in the constitution of American ‘cultural studies’ and humanistic geography, especially with Tuan's notion of sensory spaces and Relph's ‘placelessness’.Footnote 46 Rather than dwelling upon a story that has been well and truly told, I would like to argue here that the most decisive turn in this genealogy of space reductionism and the primary cause of its wide prevalence in contemporary analyses of modern spatiality took place in the 1970s, when the British radical geographer (and Cambridge-trained historian) David Harvey reunited Marxian and Heideggerian spatial thought by popularizing the combination of the phenomenological formulation with a historical framework, brought about by the rediscovery of Marx's Grundrisse.Footnote 47 I am perfectly aware of the utter contradiction between Harvey's and Heidegger's political agendas, and I imagine that this comparison might offend some of Harvey's dedicated readers. But politics should not serve as a censorious or prudish rejection of comparative analysis.

V

Even if one were to deny that Harvey had ever been Heideggerian, he was (and still admits to being) at least Lefebvrian: he was directly inspired by works such as Le droit à la ville and La production de l'espace.Footnote 48 Lefebvre was also one of the first Frenchmen to read and discuss Heidegger (as early as 1928), and, although he consistently tried to describe his intellectual relationship to Heidegger as conflicted and even argued that his whole philosophical enterprise was designed to prove Heidegger wrong, one cannot deny the seminal influence that the German thinker exerted over him and others of the Parisian jeunes philosophes in the interwar period. This peculiar French mixture of Hegelianism and Heideggerianism was crucial in preparing for Harvey's bridging of the gap between historical materialism and phenomenological analysis of space.Footnote 49 Thus, although politically antagonistic, Harvey's Condition of postmodernity can still be called a Heideggerian text.Footnote 50 Harvey emphasizes the commodification of human mobility which causes ‘places’ to lose their ‘aura’ – their significance and their distinctiveness – because of an ever-increasing ‘time-space compression’, resulting in a progressive dominance of ephemerality in all realms of social, cultural, and economic life.Footnote 51 The narrative of disenchanted place is here a direct consequence of the combination of moral and economic condemnation of industrial mobility with the subject-oriented posture entailed by its phenomenological premise.

The second building block of Harvey's intellectual edifice is carved from Marx's analysis of the spatial dynamics of capital in the Grundrisse.Footnote 52 Here again, Lefebvre had preceded him, probably helped by the fact that the French translation of the Grundrisse was released a few years earlier, in 1968–9, but it was Harvey who had the privilege of intersecting phenomenology and historical materialism for the analysis of space in the English language. The capitalist production of space, he concluded, created monotony rather than difference, for ‘goods have begun to lose their spatial presence, and they have become instead products of an increasingly expansive market’.Footnote 53 Since 1989 Harvey has refined his argument, especially in The enigma of capital (2010), in which he shows that the levelling-up action of time-space compression has been matched by the permanent production of heterogeneity through cultural, social, and economic gradients which constitute the dynamic force behind capital's ‘creative destruction’ and allow for repetition of financial and economic crises.Footnote 54

Many contemporary geographers, anthropologists, and philosophers looking at mobility phenomena, such as Relph, Seamon, Meyrowitz, Sack, Augé, and recently Malpas, have developed similar negative narratives of space reductionism, positing that human experience is constituted by its situation in space (over its social relationships, which are determinant for Harvey).Footnote 55 Since the 1990s, all these works have been subsumed under the time-space compression heading.Footnote 56 This trivialization of the Heideggerian notion of being-in-the-world establishes a normative relationship between human nature and position in space. To put it differently, everyone has to be (metaphorically and physically) in her or his place because it is only through this experiential construction of space that her or his humanity can fully be realized. These authors therefore accuse industrial mobility of spoiling this natural relationship and denaturing space, which can no longer become one's constructed place. Invasive transport technologies are both the embodiment of and the means for moral, social, or economic degradation: ‘roads, railways, airports, cutting across or imposed on the landscape rather than developing with it are not only features of placelessness in their own right, but, by making possible the mere movement of people … have encouraged the spread of placelessness’.Footnote 57

Such negative judgement regarding industrial mobility also permeated the current of cultural history initiated separately by Schivelbusch and Kern in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Both used categories imported from phenomenological psychology and psychiatry to analyse late nineteenth-century perceptions of modernity and mobility, and the trauma caused by the destruction of traditional forms of temporality and spatiality. The railways were, for Schivelbusch, ‘that great destroyer of experiential space and time … [because of which] … the places visited by the traveller become ever more similar to the commodities that are part of the same circulatory system’.Footnote 58 Although neither of them was aware of Harvey's work at the time of the original publication, promoters of the new cultural history of transport have largely annexed these texts to fit in the space reductionism framework. This framework has now become so much embedded in the ‘spirit of the time’ that in 2003, twenty years after the first publication of The culture of time and space, Kern explained in the foreword to the new edition that one of his motivations for writing the book was discerning the ‘transformation of the experience of time and space, with both transportation and communication times dropping drastically, which made for the shrinking of lived distance’.Footnote 59 The issue with this general acceptance of space reductionism is that, regardless of its late twentieth-century intellectual elaboration, it now tends to be applied indiscriminately to all early reactions to industrial mobility, as for example when Schivelbusch writes: ‘annihilation of space and time, this is how the early nineteenth century characterizes the effect of railroad travel’.Footnote 60

VI

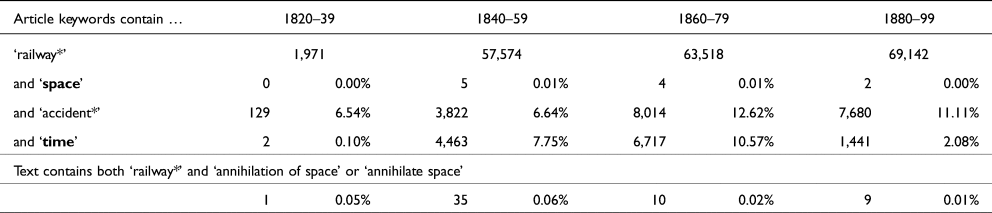

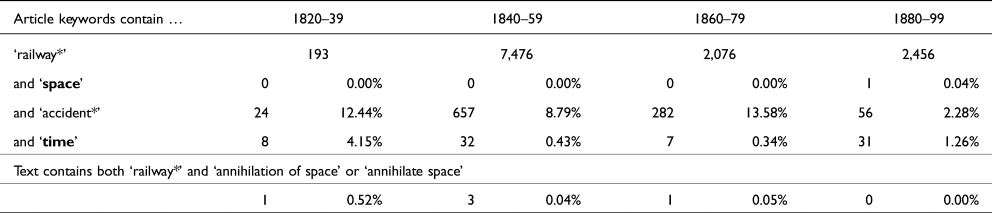

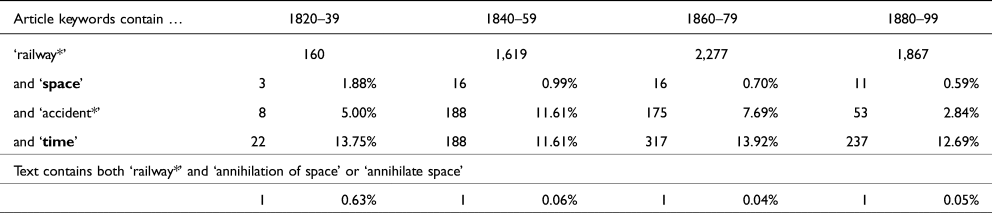

I want to conclude this article by explaining why the concept of spatial compression – in both its experiential and speculative versions – cannot be a proper historical category, and why, as for Schivelbusch in the quote above, it generally leads to misrepresenting the effects of industrial mobility on space and its representations. The main problem, which historians will hopefully regard as a death warrant for its experiential component, is that it is anachronistic and socially exclusive, but at the same time far too generic and crude a descriptor for the variety of spatial experiences. Tables 1–3 (see below) show that, contrary to what Schivelbusch claimed, nineteenth-century discussions of the railways seldom focused on questions of space. Furthermore, spatial compression tends to disguise a whole series of questionable social, occupational, regional, national, and sexual reductionisms, and homogenizes the understanding of past experiences: women and men, rural and urban dwellers, workers and aristocrats, Britons and Americans had divergent perceptions and uses of spatiality and industrial mobility, and their spaces did not shrink at the same rate or in the same direction, if at all.Footnote 61

Table 1 Articles about railways in nineteenth-century British Library newspapers

Table 2 Articles about railways in Gale nineteenth-century UK periodicals parts 1 and 2

Table 3 Articles about railways in ProQuest UMI British periodicals collection

Does that mean that any overarching narrative on space should be regarded as failing this principle of sociological diversity? Absolutely not. Spatial homogeneity – understood as a by-product of modernity – should not be a prerequisite to the writing of good connected or global histories. As David Edgerton put it, the problem is that much of this literature ‘simply re-assert[s] … techno-globalist clichés about a shrinking interconnected world, now expressed as a rejection of ideas of centres and peripheries and a focus on circulation and networks’.Footnote 62 Other conceptualizations that do not rely on spatial compression are possible. When in 1991 Benedict Anderson revised his landmark study of nationalism, Imagined communities, he added two chapters to correct what he then saw as ‘serious theoretical flaws’ in the original (1983) edition, both linked to some extent to the relationship between space and modernity.Footnote 63 The first one, ‘Census, map, museum’, showed how European colonial spatiality (here mediated through cartographic means), far from creating a homogenous spatial experience of modernity, brought about the tools and the needs to contest it,Footnote 64 while the second, ‘Memory and forgetting’, reframed Anderson's theory of the spatial and temporal foundations of the nation.

The temporal schizophrenia at the heart of Anderson's conceptualization – the nation is experienced as both the remembering and forgetting of a fantasized communal past binding members of the polity – has its own spatial equivalent, too. He shows that the naming of colonial settlements as newer versions of European cities (New York, Nueva Leon, Nouvelle Orléans, Nova Lisboa, Nieuw Amsterdam) does not illustrate a shrinking of space but a new conception of synchronous but distant communality, not unlike the science-fiction trope of parallel universes or realities accessible through portals or windows. This layering of early modern time-space was in no way made redundant by the advent of industrial technologies. The portals may have changed in shape (from that of the printing press and steamboats to perhaps that of a low-cost airline and a social media blue bird) or in size (many more people inhabit our planet today and can now willingly travel across continents), but the underlying parallel experiences of spatiality have never been abolished by these changes. As Anderson adds, for ‘this sense of parallelism or simultaneity not merely to arise but also to have vast political consequences, it was necessary that the distance between parallel groups be large’.Footnote 65 Distance is a precondition to the new synchronous spatiality of the Nation-State, not abolished by it.

Historians who nevertheless choose to co-opt accounts of shrinking space have tended to justify their choice of terminology by quoting contemporaries who used similar language. It should be clear by now that conflating the metaphorical use of the 1830s and the phenomenological concept now prevalent among certain geographers is both ahistorical and beside the point. But could we not, regardless of linguistic and theoretical hair-splitting, argue that contemporaries did experience a fundamental distress caused by industrial mobility, and that spatial compression was their way of conveying it? This is not convincing either. Selecting quotes from a very vocal but unrepresentative sample of writers for whom aesthetics, tradition, and economic morality were the holy trinity against industrial mobility is not sufficient. The likes of Wordsworth, Arnold, Carlyle, Ruskin, or Vigny, or the allegorical prose of socially minded realist writers such as Dickens or Zola, who used the railways as a social metaphor, do not reveal popular perceptions at the time. Wordsworth's sonnet ‘Is there no nook of English ground secure from rash assault?’, sent to Gladstone in 1844 as a protest against the opening of the Kendal and Windermere Railway, is often quoted as the seminal cultural reference of this pastoral inward-looking Victorian vision.Footnote 66 The same is true in France of Alfred de Vigny's poem ‘La maison du berger’, also published in 1844, in reaction to a Versailles–Paris train crash two years earlier (‘Distance and time have been vanquished … Our experience has shrunk the world’).Footnote 67 Both are echoed in Ruskin's fulminations against the positivist, utopian, and civilizational values of the railways: ‘A fool always wants to shorten space and time: a wise man wants to lengthen both. A fool wants to kill space and kill time … Your railroad, when you come to understand it, is only a device for making the world smaller.’Footnote 68

Do such texts really prove a Victorian aversion to the railways, modernity, and urbanity? And how representative of Victorian society were these enlightened aesthetes? In an important article, Peter Mandler has warned us against the over-representation of rural nostalgia. These reactionary ideologues, he argues, constituted a minority of writers who were neither drawn from the popular masses they so despised nor representative of the aristocratic and financial elite. They were, ‘rather, those who fulminated against the dominant classes and propagandized for an “Englishness” that they felt was practically near extinction. Distinct from the true dominant classes, they have their own sociology and chronology.’Footnote 69 The same is true for the railways: landed aristocrats’ early rejection of the railways was chiefly due to pecuniary, not moral or aesthetic, concerns. Even the duke of Wellington, who is so often quoted as a paragon of railway opponents, ended up speculating in railways and earning great amounts thanks to them. Public campaigns and parliamentary proceedings give a good indication of these landowners’ motivations; although they denounced the railways’ danger and filth, the disturbance to rural life – lowering yields, maddening cows, and ‘injuring the fleeces of the sheep’ – and disruption to ancestral traditions like fox hunting, all the protest really came down to a fear that it might reduce property values.Footnote 70 The opposition to the railways from the landed elite was based on economic grounds, not aesthetic or moral ones, and, unsurprisingly, the fiercest reaction came from turnpike investors and canal proprietors worried by the competition.

Finally, hardly any evidence suggests that the way in which most Britons imagined the railways and its consequences involved any thought of negative spatial reduction. There was no real movement of popular protest against the railways during their formative years, and, if usage means consent, it is fair to say that they were very swiftly and massively adopted. Although in the early years the railways chiefly targeted affluent coach travellers, after 1844–5 third-class passengers progressively became an essential part of companies’ passenger business.Footnote 71 Together with the popularity of ‘parliamentary trains’ and, after 1883, of workers’ tickets, this rules out any popular rejection of the railways dominated by fear of a shrinking world. Even those who did not travel, or could not yet afford it in the 1830s, seem to have enjoyed the railways as a popular attraction. During this decade it was common for people to watch the spectacle of trains arriving at London stations. In sum, as Mandler argued, ‘the fact is that before the First World War, English culture as a whole was aggressively urban and materialist, and the rural-nostalgic vision of “Englishness” remained the province of impassioned and highly articulate but fairly marginal artistic groups’.Footnote 72

Similarly, Harvey's premise that the railways increased the pressure on labour mobility, and hence uprooted and traumatized many working-class people, is questionable. Even if it were possible to prove that mobility was inherently psychologically traumatic, labour mobility and urbanization are two phenomena that largely predated the railway age. Furthermore, industrial mobility had three positive indirect benefits: first, by making it possible to commute over longer distances, it helped some people live further away from industrial centres and hence lessened the afflictions inherent to early industrialized urbanity. Avoiding a flight from the land and the ‘Manchesterian evils’ (misery, urban squalor, lack of sanitation, overcrowding, and a more precarious epidemiological regime) was certainly one of the top priorities of most European politicians in the mid-nineteenth century – and of many other countries in the twentieth century, especially China. In Belgium, the solution to this problem was not to prevent labour mobility but to build a very dense railway network and offer affordable workers’ tickets so that rural labourers could start commuting instead of migrating, and by 1900 over 20 per cent of all Belgian workers were commuting by train.Footnote 73 Secondly, the railways and steamships certainly amplified long-distance emigration by dramatically lowering the cost of transatlantic travel, but it is hard to see how much more traumatic this mobility was compared to previous waves of emigration, which seldom included the possibility of a return journey or were made in incomparably more dangerous and desperate conditions. How blind can it be to criticize the traumatic effect of steamships or aeroplanes while – so close to home – men, women, and children are still killed in thousands each year attempting to reach European shores on dinghies? Thirdly, for all the legitimate concerns about tragic crashes and wrecks, transport safety surely increased in the age of steam and has done so steadily since then. Although there is currently no relevant data available for the earlier period, it would be very surprising if fatalities per passenger mile travelled by both coach and sail were lower in the sixteenth century than those in the nineteenth century. For all these reasons, once we reject psychological models, the evidence for any general traumatic experience of industrial mobility appears much sparser.

The ecstatic view of modernity is no less caricatured and restrictive. Over-enthusiastic accounts of the railways generally came down to either technophilia (often by engineers, mechanics, or even architects like George GodwinFootnote 74) or utopian prospects of spatial unity (Saint-Simonian – see Russell's quote above) acting as a literal rapprochement between nations and peoples. This is the case with most early railway advocates, such as Thomas Gray or Samuel Smiles, and some Whig historians like T. B. Macaulay, but their work should not be considered as representative of a general attitude towards the railways.Footnote 75

Looking at different (not literary) sources emphasizes the unrepresentative nature of this dichotomy. Newspaper archives, for example, reveal a more nuanced picture: despite some scattered enthusiastic comments, suspicion about the financial soundness of the railways was the prevailing concern of most articles published in the 1820s and early 1830s. Obviously, this only mattered to a very limited and economically literate audience interested in the stock markets – regular readers of the financial sections of these newspapers – and so it had little popular resonance. It was only the ‘railway manias’ of 1835–7 and 1843–4, with the dramatic downfalls of speculators, that aroused massive public interest.Footnote 76 The almost twentyfold increase in the number of articles about the railways between 1820–39 and 1840–59 in three nineteenth-century British periodical databases (Tables 1–3) illustrates this sudden wave of public scrutiny very well. Fervency and rejection closely followed the boom-and-bust cycles of the railway economy. It is true that these repeated financial scandals nevertheless ended up fuelling a popular denunciation of venality and speculation.Footnote 77 Although this might seem very similar to the romantic moral argument, the conjunction of the two was only momentary and based on very different perceptions: it was not beauty, tradition, or religion that most people had in mind but the dramatic depictions of railway catastrophes. In the 1880s the attention of the public had shifted from aesthetics to questions of security and the ethics of railway companies.

Accidents were by far the most frequent and long-lasting subject of all discussions regarding the railways throughout the nineteenth century, starting with the first fatal one, the dramatic death of the M.P. William Huskisson, whose leg was crushed by ‘Stephenson's Rocket’ on 15 September 1830 during the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Whether opposition came from people like Vigny after the shocking derailing of the Versailles–Paris train in 1842, which killed over fifty people, or Dickens, who himself quite miraculously survived a terrible train crash in June 1865, or from those who denounced the unscrupulous behaviour of companies eager to secure profits over passengers’ safety, accidents were defining moments in the constitution and crystallization of popular opposition to the management of the railways.Footnote 78

Mirroring this obsession with catastrophes, a new literary genre appeared which used the railways as a social or civilizational metaphor, including ghost stories, crime novels, all sorts of cartoons, and tales of adventure.Footnote 79 Such texts and images, though still very dramatic in essence, give a valuable insight into a much more socially inclusive and routine experience of the railways, as they also belong in the broader realm of material culture that is so fundamental to our understanding of people's perception of space. Printed material such as railway guides, timetables, newspaper commercials, maps, and railway indicators, among many other similar objects, can likewise illustrate the expanding mental repertoire of place, space, and time, from which social and cultural historians can trace changes in the experience of railway travel.Footnote 80 From this vantage point, new industrial technologies of transport appear to have added complexity and enhanced the contemporary observer's and traveller's world, rather than shrunk it. Material culture does not, however, fully answer Mandler's question, about the sociology – and more generally the multiplicity – of responses to industrial mobility.

To give a satisfactory account of how people conceived and experienced spatiality, a radically improved empirical knowledge is first required: who moved, when, where, and at what speed? Until all these questions find proper answers, most of what we can say about popular experiences of space in the railway age will rely on a small quantity of questionable evidence and untold ideological frameworks, hidden behind an indiscriminate and overblown notion of the impact of technological change. Critical geography and human geography in the vein identified in this article are unlikely to be the most suitable disciplines to lead the way. Instead, it might be time for a revaluation of empirical economic geography – making use of more advanced geospatial technologies,Footnote 81 and the ability to incorporate very large, spatially disaggregated datasets – combined with a socio-cultural history of techniques. This is the key to a much finer and more rigorous understanding of changing experiences of space in the age of industrial mobility.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Ruth Murphy for her patient and sharp-eyed proofreading.