Introduction

The new Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a highly contagious disease that was discovered near the end of 2019. The rapid and ubiquitous spread of COVID-19 has produced a global pandemic that has created new challenges for public health, continuing and long-term care (LTC) systems, community support organizations, businesses and the economy, families, and individuals. COVID-19 has been conceptualized as a “gero-pandemic”, defined as a disease that has spread globally with heightened significance and deleterious consequences for older populations (Wister & Speechley, Reference Wister and Speechley2020). This has raised the profile of aging-related pandemic challenges facing societies and older individuals.

As of the end of January 2022, COVID-19 cases surpassed 2,900,000 in Canada and 364,000,000 worldwide. The number of deaths has passed 33,000 in Canada and has exceeded 5,600,000 globally (Government of Canada, 2022). Approximately 15% of positive cases are among persons 60 years of age and older, and over 90% of deaths are among this age group (Government of Canada, 2022). Furthermore, residents of long-term care facilities account for approximately 3 per cent of COVID-19 cases and 43 per cent of deaths (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021). Yet, those living in the community also face risk of infection, and the effects of the pandemic response (Cohen & Tavares, Reference Cohen and Tavares2020).

Although age has become a major focal point in the pandemic (Morrow-Howell, Galucia, & Swinford, Reference Morrow-Howell, Galucia and Swinford2020; Shahid et al., Reference Shahid, Kalayanamitra, McClafferty, Kepko, Ramgobin and Patel2020), there are also other aspects that result in increased risk of and vulnerability to pandemic social isolation and loneliness among older persons. These include mental health or lowered psychological well-being (Alonzi, La Torre, & Silverstein, Reference Alonzi, La Torre and Silverstein2020; Barber & Kim, Reference Barber and Kim2021); physical health conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) (Mauvais-Jarvis, Reference Mauvais-Jarvis2020; Mitra et al., Reference Mitra, Fergusson, Lloyd-Smith, Wormsbecker, Foster and Karpov2020); and mult-imorbidity (Wister, Reference Wister, Rootman, Edwards, Levasseur and Grunberg2021a, Reference Wister, Trump and Linkovb; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong2020). Also at increased risk are individuals who are marginalized as a result of poverty; sexual orientation; race, ethnicity, or culture; immigration status; rural/remote environment; or other vulnerabilities (Alonzi et al., Reference Alonzi, La Torre and Silverstein2020; Wister, Reference Wister, Rootman, Edwards, Levasseur and Grunberg2021a, Reference Wister, Trump and Linkovb).

To reduce the spread of COVID-19, governments have implemented public health measures such as physical/social distancing recommendations, closure of non-essential businesses and public spaces, implementation of lockdowns and stay at home orders, mask mandates, travel restrictions, and restrictions on visitors to LTC facilities. Although these measures have resulted in some successes in reducing transmission of COVID-19, concerns have been raised about the potential negative impacts of the prolonged periods of physical/social distancing and reduced social interactions, with specific attention paid to impacts on older adults (e.g., Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Galucia and Swinford2020; Smith, Steinman, & Casey, Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020). In pandemic research social distancing has been associated with social isolation in community-dwelling older adult populations (Adepoju et al., Reference Adepoju, Chae, Woodard, Smith, Herrera and Han2021). Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020) use the term “COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox” to refer to the paradox that meaningful interactions and social connections are important for the health of older adults, yet pandemic restrictions require older adults to avoid friends, family, and sources of social support.

Indeed, it is well established that social isolation is a common public health concern among community-dwelling older adults, which has been exacerbated by the pandemic, in particular physical/social distancing measures (Shahid et al., Reference Shahid, Kalayanamitra, McClafferty, Kepko, Ramgobin and Patel2020). Pre-pandemic literature has demonstrated that social isolation and loneliness among older adults increases morbidity and mortality; reduces the ability to engage in healthy behaviours; increases anxiety, depression, and stress; decreases health-related quality of life, psychological well-being, and happiness; and results in lower access to health care services and lower health care utilization (Burholt et al., Reference Burholt, Winter, Aartsen, Constantinou, Dahlberg and Feliciano2020; Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017; Fakoya, McCorry, & Donnelly, Reference Fakoya, McCorry and Donnelly2020; Golden et al., Reference Golden, Conroy, Bruce, Denihan, Greene and Kirby2009; Kirkland et al., Reference Kirkland, Griffith, Menec, Wister, Hélène and Wolfson2015; Leigh-Hunt et al., Reference Leigh-Hunt, Bagguley, Turner, Turnbull, Valtorta and Caan2017; National Seniors Council, 2014a, b; 2016; Newall, McArthur, & Menec, Reference Newall, McArthur and Menec2015; Wister, Cosco, Mitchell, Menec, & Fyffe, Reference Wister, Cosco, Mitchell, Menec and Fyffe2019; Wister, Menec, & Mugford, Reference Wister, Menec, Mugford, Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland and Griffith2018).

Therefore, this article addresses current knowledge about the effects of social isolation and loneliness on community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic through the combination of a scoping review, grey literature scan, and new data, given that the research in this area is in its formative stages. We utilize a spectrum of international academic literature, given the dearth of Canadian literature. To add a Canadian perspective to the article, we also include analysis of data on the prevalence of loneliness among older Canadians from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Also, because of the fast-paced and dynamic nature of the pandemic, we incorporate a scan of Canadian grey literature on pandemic interventions. Data are presented on the extent of the problem, risk and protective factors (that either increase or decrease the likelihood of social isolation and/or loneliness), effects on older adults, and strategies and interventions that have been recommended or implemented to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults during the pandemic.

Defining Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Older Adults

Social isolation is commonly defined as “a lack in quantity and quality of social contacts” and “involves few social contacts and few social roles, as well as the absence of mutually rewarding relationships” (Keefe, Andrew, Fancey, & Hall, Reference Keefe, Andrew, Fancey and Hall2006, p.1). A concept closely related to social isolation is loneliness “defined as a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one’s social relationships” (Hawkley & Cacioppo, Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2010, p.1). The key distinction between social isolation and loneliness is that social isolation refers to the objective level of social connections, whereas loneliness reflects the perception of being disconnected from others (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017). An example of a common instrument to measure loneliness is the UCLA-3 Loneliness Scale (and its longer version), consisting of three subjective questions that participants score on a three-point scale (e.g., “How often do you feel that you lack companionship?”) (Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, Reference Hughes, Waite, Hawkley and Cacioppo2004). Social isolation tends to be measured with a broader set of scales. For example, the Abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale consists of six questions about contact with friends and family (e.g., “How many relatives do you see or hear from at least once a month?”) (Lubben et al., Reference Lubben, Blozik, Gillmann, Iliffe, von Renteln Kruse and Beck2006). Although loneliness and social isolation often overlap, there can be unique associations; for instance, some older adults may not feel lonely even if they have low levels of social connectedness, and some people who have many social contacts feel lonely.

Conceptual Framework

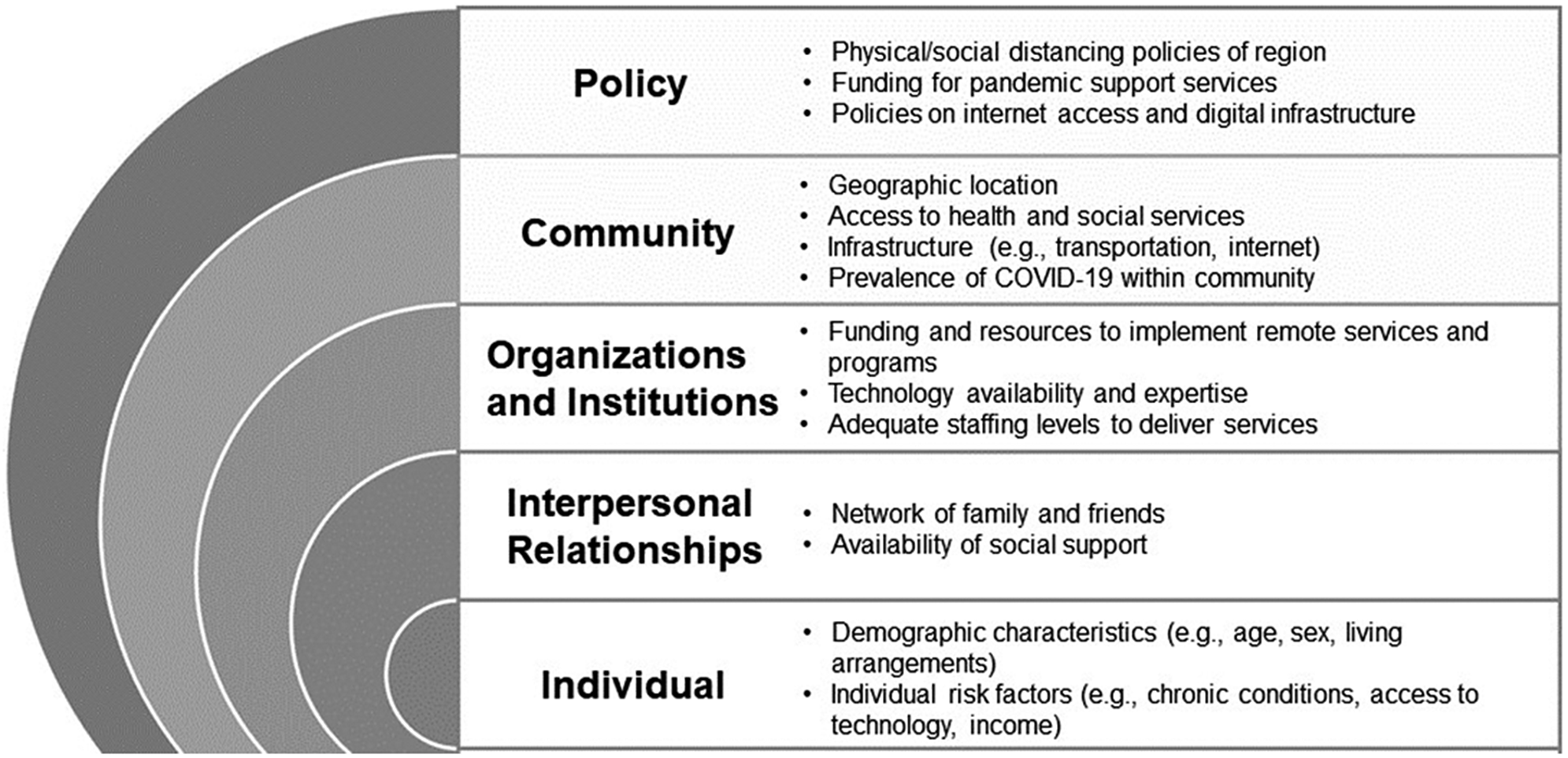

Two complementary models are useful in framing social isolation and loneliness among older adults during the pandemic. Socio-ecological (or socio-environmental) (SE) theory posits that individuals, social systems, and the environment are interrelated and interdependent (Bronfenbrenner,Reference Bronfenbrenner, Gauvain and Cole1994; Stokols, Reference Stokols1992; Reference Stokols2017). Thus, the SE framework differentiates and connects each of the nested ecological domains (e.g., individual, interpersonal, organizational, neighbourhood, municipal, health regional, provincial, country, and global levels) to understand aging experiences. The SE framework has been applied as a useful conceptual framework in the areas of housing (Lawton, Reference Lawton1980), homelessness (Canham, O’Dea, & Wister, Reference Canham, O’Dea and Wister2019), green spaces and walkability (Chaudhury et al., Reference Chaudhury, Sarte, Michael, Mahmood, Keast and Dogaru2011), healthy public policy (Wister & Speechley, Reference Wister and Speechley2015), and recently, COVID-19 (Andrew et al., Reference Andrew, Searle, McElhaney, McNeil, Clarke and Rockwood2020). For example, in a study of frailty and LTC, Andrew et al. (Reference Andrew, Searle, McElhaney, McNeil, Clarke and Rockwood2020) identify COVID-19 risk, vulnerabilities, and responses at the individual level (e.g., pre-existing conditions); family level (e.g., policies limiting physical contact with relatives in LTC); community level (e.g., making public transportation systems less risky to use); and policy level (e.g., increased funding for pandemic response). Figure 1 provides an illustration of how the SE framework can be applied to the issue of social isolation and loneliness during the pandemic.

Figure 1. Socio-ecological framework and loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A second framework that directly builds on and extends the SE framework, adding a new dimension to understanding the pandemic, is a complex systems resilience framework that stems from disaster response research (Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump, & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump, Linkov, Wister and Cosco2021; Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister, & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister and Linkov2021). This framework attempts to: (1) link and quantify the different individual and environmental-level spheres of influence observed within the existing SE framework, and (2) apply a resilience lens whereby focus is placed on how and why individuals and systems respond to adversity (see Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump, Linkov, Wister and Cosco2021 and Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister and Linkov2021 for a full description of this model). According to the National Research Council (2012), the ability of a system to adapt to, plan with regard to, recover from, and absorb adversity represents four key resilience processes. These have been applied to structural systems, individuals, and families.

This framework has also been applied to COVID-19 (Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump, Linkov, Wister and Cosco2021; Linkov, Keenan, & Trump, Reference Linkov, Keenan and Trump2021). First, planning and preparing for adverse or stress-inducing events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, requires targeted reductions in risk and vulnerabilities. Pandemic planning necessitates an understanding of the characteristics of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as population susceptibility, severity, and behavioural response. Second, mitigation of outcomes associated with the adversity (e.g., social isolation and loneliness due to COVID-19 physical/social distancing policies) is necessary to produce positive resilience or coping responses. The ability of an individual or system to overcome pandemic adversity is a primary component of resilience. Third, recovery relies on various forms of strength-based resilience embedded in the individual, family, community, and structural system levels. Recovery is essential for counteracting the weakening of any system so that it can respond to future adversity such as a COVID-19 variant infection wave or a different pandemic on the horizon. Finally, a complex systems resilience framework focuses attention on fostering the strengths of individuals, families, and communities; for example, some Indigenous reserve communities have utilized strong community connections and leadership to support pandemic mitigation strategies even though health care resources tend to be weaker (National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools & National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, 2020). The complex systems resilience framework helps to identify the weaknesses and strengths in nested ecological systems that influence risk and response to social isolation among older adults during the pandemic (Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister and Linkov2021; Pearman, Hughes, Smith, & Neupert, Reference Pearman, Hughes, Smith and Neupert2021; Wister, Klasa & Linkov, Reference Wister, Klasa and Linkov2022).

Methods

CLSA Data

The CLSA is a national, longitudinal study that aims to follow 50,000 Canadians 45 years of age and up for 20 years (see Raina et al. Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Oremus and Patterson2009; Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Balion and Cossette2019; for more details). In order to estimate the increase in loneliness during the pandemic, we use unique data drawn from three separate waves of the CLSA. CLSA Baseline data (collected 2011–2015; n = 51,338); Follow-up One data (collected 2015–2018; n = 44,817); and data from the CLSA COVID-19 Study (collected April to December, 2020; n = 28,559) are employed. Loneliness is measured in all surveys using an identical measure derived from the single loneliness item from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies (CES)-D depression scale. Participants who reported being lonely some of the time, occasionally, or all of the time were deemed to be lonely (compared with those who reported being lonely rarely/none of the time). At the time of writing this article, only the COVID-19 Baseline survey data were available, and only in secondary descriptive form on the CLSA Web site (www.clsa-elcv.ca/) (i.e., not available for analysis and/or linkage to the other CLSA surveys). Therefore, the surveys are employed as individual samples showing age-sex patterns in loneliness for two pre-pandemic periods and one early pandemic survey, albeit with different sample sizes as a result of attrition and non-response.

Scoping Review Methods

The literature review followed the five steps outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) for scoping reviews: (1) identify the research question, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) select relevant studies, (4) chart the data, and (5) collate, summarize, and report the results.

The research questions guiding the review were:

-

1. How has the pandemic impacted patterns of social isolation and loneliness among older adult populations internationally?

-

2. What effects have experiences of social isolation and loneliness had on older adults during the pandemic?

-

3. What strategies and interventions have been recommended to reduce the social isolation and loneliness of older adults during the pandemic?

-

4. What interventions have been implemented to reduce the social isolation and loneliness of older adults during the pandemic?

An initial search of English-language literature from academic journals was conducted the week of January 11, 2021, using the search engine Ebscohost. Ebscohost can search multiple databases simultaneously (e.g., AgeLine, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], MEDLINE®, Social Sciences, PsycInfo, Academic Search Premier). Because of the fast-paced and changing nature of the pandemic, two supplementary searches were conducted the weeks of February 15 and March 8. The keywords used in the searches were social isolation OR loneliness, AND older adults (or synonyms) AND COVID-19 (or synonyms).

Articles were included in the review if they focused on one of the following subjects: (1) patterns (e.g., prevalence, changes, associated factors, effects) of social isolation or loneliness among older adult populations during the COVID-19 pandemic; or (2) strategies or interventions (recommended or implemented) to reduce social isolation or loneliness among older adult populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. For category (2), non-empirical academic literature (e.g., commentaries, descriptions of programs) were considered for inclusion given the paucity of empirical literature. Articles were excluded if they met any of the following exclusion criteria: (1) not written in English, (2) did not focus on a community-dwelling older adult population (articles that included multiple age groups were retained if there was deemed to be sufficient analysis/findings focusing on older age groups), (3) not related to social isolation and/or loneliness, or (4) did not focus on the COVID-19 pandemic context.

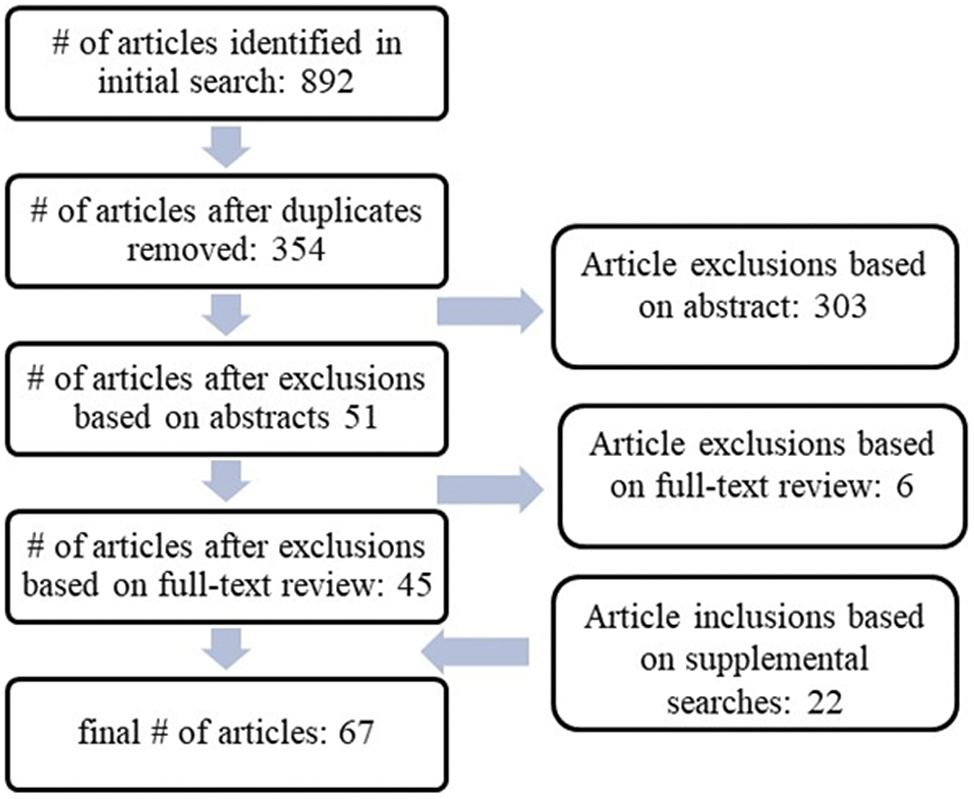

As shown in Figure 2, a total of 67 articles were included in this review based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Given the expected lag between implementation of interventions during the pandemic and publication of journal articles, a supplementary scan of Canadian grey literature (e.g., newspapers, organizational Web sites, and reports) was undertaken between February and March of 2021 to identify common types of interventions being implemented in Canada during the pandemic. Most interventions were identified via news stories through a Google search of the news, using the keywords social isolation OR loneliness AND older adults OR seniors AND Canada. Web sites of organizations serving older adults that were known to the authors were also searched for information on programs (e.g., Healthy Aging CORE BC, A & O).

Figure 2. Literature search strategy.

Results

Patterns of Loneliness in the CLSA during the Pandemic

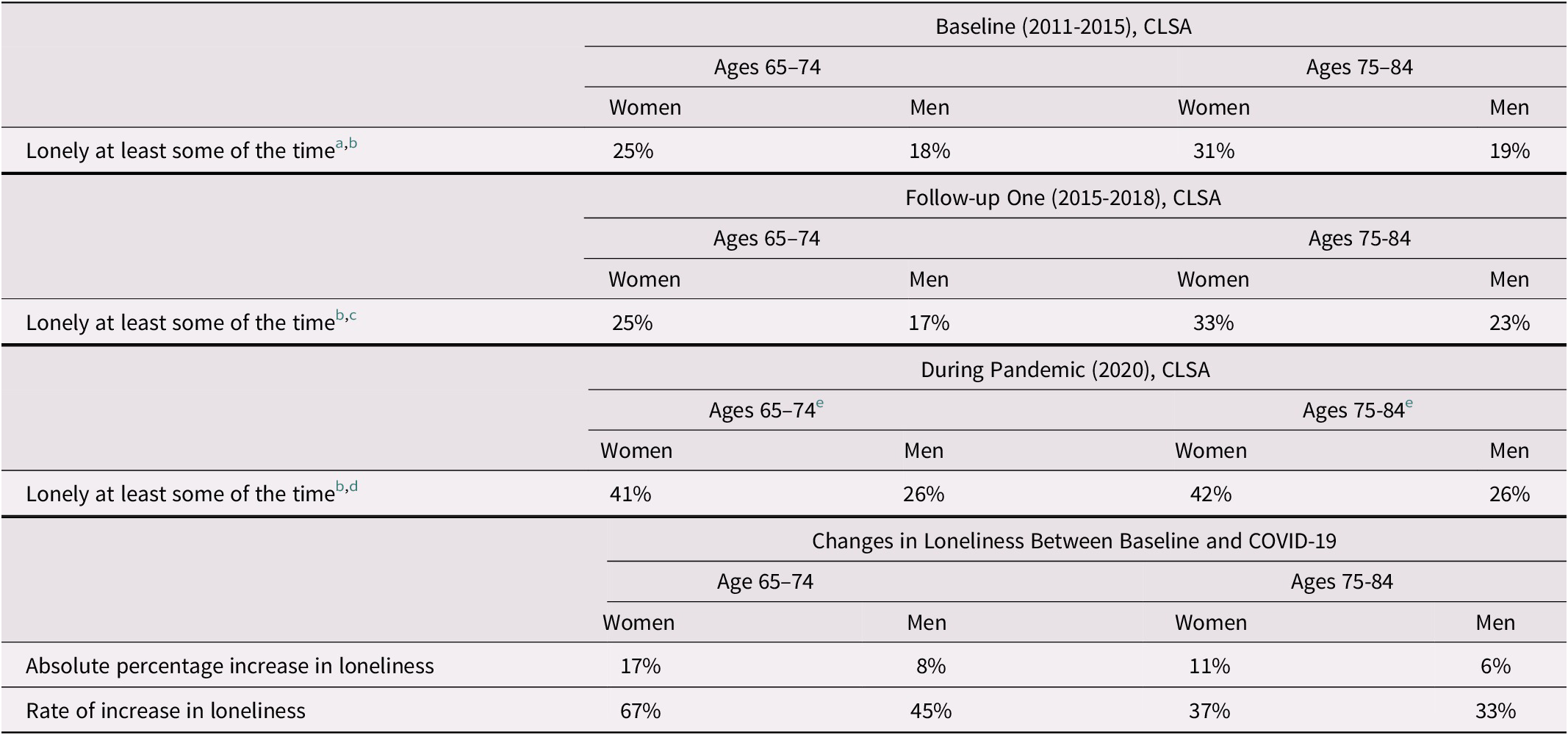

Table 1 presents descriptive data on percentages of CLSA participants feeling lonely. Using pre-pandemic cross-sectional data at CLSA Baseline (2011–2015), among older women 65–74 years of age we observed that 25 per cent reported feeling lonely, whereas among women 75–84 years of age, a total of 31 per cent reported feeling lonely. For men, the rates were lower for these same age groups, where 18 and 19 per cent reported being lonely, respectively. The rates for the CLSA Follow-up One (2015–2018) were almost identical to Baseline levels, with only men 75–84 years of age showing a slight rise from 19 to 23 per cent being lonely. Turning to the CLSA COVID-19 Study (2020), the absolute percentages increased significantly. Among women 65–74 years of age, 41 per cent reported feeling lonely, with 42 per cent among those 75–84 years of age reporting feeling lonely. For men, the percentages also increased, but were lower than for women. Among men 65–74 and 75–84 years of age, 26 per cent felt lonely at least some of the time.

Table 1. Loneliness patterns by age and sex, baseline (2011-2015), Follow-up One (2015-2018), and during pandemic (2020), CLSA

Note. All percentages have been rounded.

a Data drawn from Wister et al., Reference Wister, Menec, Mugford, Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland and Griffith2018.

b Includes: All of the time, Occasionally, and Some of the time responses compared with Rarely/None of the time.

c Generated from Follow-up One CLSA data by authors.

d Generated from the CLSA COVID-19 Study, CLSA Data Centre, McGill University.

e Only includes these ages (65–74 and 75–84) to compare with baseline and follow-up ages.

The relative rate increase in loneliness (percentage change between CLSA Baseline and COVID survey time periods, divided by CLSA Baseline percentage) was striking. There was a 67% increase in loneliness for women 65–74 years of age, and a 37 per cent increase for those 75–84 years of age. Smaller increases were observed for men, for whom there was a 45 per cent relative rise for those 65–74 years of age and a 33 per cent relative increase for the oldest group (see Table 1).

Patterns of Social Isolation and Loneliness Internationally during the Pandemic

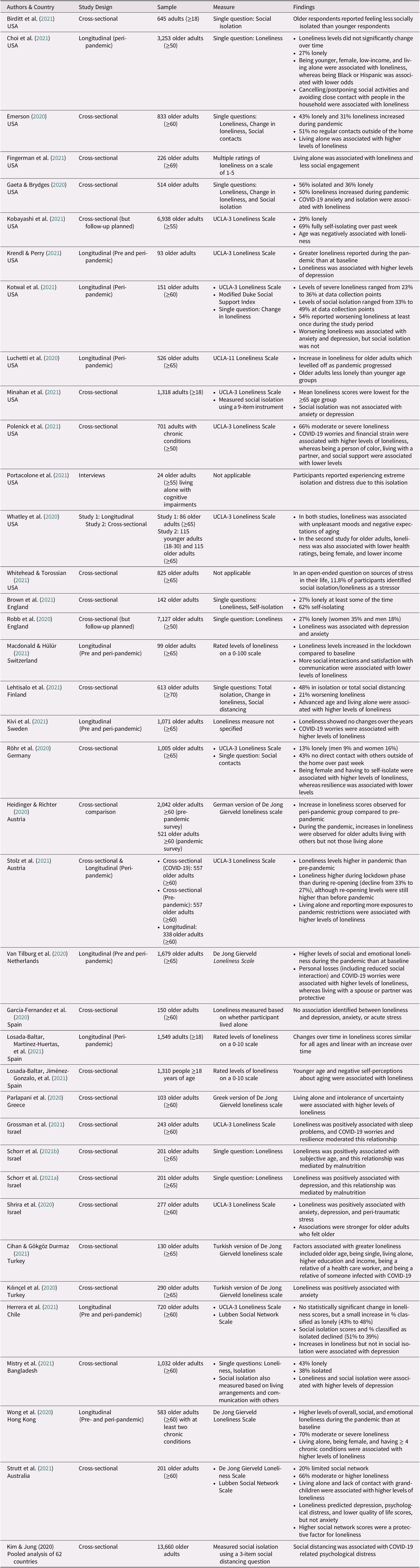

The complex systems resilience framework outlines the need to understand the characteristics of a problem, factors that contribute to vulnerabilities and resilience, and the effects of the problem. In the international literature, a total of 38 articles were identified that reported on patterns of social isolation and loneliness during the pandemic (prevalence and changes, factors, effects). Most articles reported on multiple types of patterns: 22 reported on prevalence or changes in patterns of social isolation and/or loneliness during the pandemic, 24 on associated factors, and 14 on the effects of social isolation or loneliness on older adults. A wide variety of instruments were used in the studies to measure social isolation and loneliness, and some of the measurements utilized were unvalidated or differed from typical measurements for the concept (e.g., reporting on social isolation based on an objective perception). We have reported these findings based on the conceptualization used by the authors. Most studies were cross-sectional (n = 25) or longitudinal (n = 10). There were two hybrid studies that used both cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Only one relevant qualitative study was identified.

Prevalence and Changes in Levels of Social Isolation and Loneliness

Twenty-two studies reported on patterns of social isolation and/or loneliness among older adult populations during the pandemic. The majority originated in the United States (n = 8) or European countries (n = 10) (see Table 2 for an overview of the studies and their findings).

Table 2. Overview of studies reporting on prevalence and changes in rates of social isolation and/or loneliness

In studies that reported on the prevalence of loneliness during the pandemic (n = 12), results ranged from 13 to 66 per cent of community-dwelling older adults (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mossabir, Harrison, Brundle, Smith and Clegg2021; Choi, Farina, Wu, & Ailshire, Reference Choi, Farina, Wu and Ailshire2021; Emerson, Reference Emerson2020; Gaeta & Brydges, Reference Gaeta and Brydges2020; Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Elgueta, Fernández, Giacoman, Leal and Marshall2021; Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, O’Shea, Kler, Nishimura, Palavicino-Maggio and Eastman2021; Kotwal et al., Reference Kotwal, Holt-Lunstad, Newmark, Cenzer, Smith and Covinsky2021; Mistry et al., Reference Mistry, Ali, Hossain, Yadav, Ghimire and Rahman2021; Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh and McKeand2020; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Reininghaus and Riedel-Heller2020; Stolz, Mayerl, & Freidl, Reference Stolz, Mayerl and Freidl2021; Strutt et al., Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021). Two additional studies focusing on older adult populations with chronic conditions reported even higher rates of loneliness, with 66 per cent (Polenick et al., Reference Polenick, Perbix, Salwi, Maust, Birditt and Brooks2021) and 70 per cent (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong2020) found to be lonely, respectively. In addition, in three cross-sectional studies, participants were asked whether they believed that their levels of loneliness had worsened during the pandemic; positive responses range from 21 to 50 per cent (Emerson, Reference Emerson2020; Gaeta & Brydges, Reference Gaeta and Brydges2020; Lehtisalo et al., Reference Lehtisalo, Palmer, Mangialasche, Solomon, Kivipelto and Ngandu2021).

Most of the longitudinal studies comparing levels of loneliness pre and peri-pandemic reported that levels of loneliness increased during the pandemic. Studies from the United States (Krendl & Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021), Switzerland (Macdonald & Hülür, Reference Macdonald and Hülür2021), Netherlands (Van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest, & de Vries, Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries2020), and Hong Kong (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong2020) reported greater levels of loneliness peri-pandemic than pre-pandemic. In Chile, no statistically significant change in mean loneliness scores was observed, although there was a small increase in the proportion of older adults classified as lonely by the authors based on a dichotomous classification of loneliness scores (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Elgueta, Fernández, Giacoman, Leal and Marshall2021). A Swedish study found no differences in loneliness between COVID-19 and pre-pandemic data collection points (Kivi, Hansson, & Bjälkebring, Reference Kivi, Hansson and Bjälkebring2021). Additionally, an Austrian study compared data from two different cross-sectional samples and reported an increase in loneliness scores during the pandemic (Heidinger & Richter, Reference Heidinger and Richter2020).

Five longitudinal studies reported data on loneliness collected at multiple points during the pandemic. Kotwal et al. (Reference Kotwal, Holt-Lunstad, Newmark, Cenzer, Smith and Covinsky2021) collected data in the United States over the period from April to June 2020, and levels of severe loneliness ranged from 23 to 36 per cent. Levels of loneliness were highest during the first period of data collection (4–6 weeks after shelter in place orders began). Although levels of loneliness tended to level off over the course of the pandemic, a sub-group of respondents reported persistent or higher rates of loneliness. Luchetti et al. (Reference Luchetti, Lee, Aschwanden, Sesker, Strickhouser and Terracciano2020) collected data in the United States between February and April 2020 and similarly found an increase in loneliness that plateaued over time. Another American study by Choi et al. (Reference Choi, Farina, Wu and Ailshire2021) measured loneliness between April and June 2020, reporting stable levels of loneliness. Stolz et al. (Reference Stolz, Mayerl and Freidl2021) observed a small decline in loneliness levels between the lock-down phase in Austria (March to April 2020) and re-opening (May to June 2020), although levels of loneliness remained above regular levels. In a study from Spain by Losada-Baltar, Martínez-Huertas, et al. (Reference Losada-Baltar, Martínez-Huertas, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Pedroso-Chaparro, Gallego-Alberto and Fernandes-Pires2021), there was an increase in loneliness scores over time (March to May 2020) for both older adults and younger age groups. The leveling or declining of loneliness during the pandemic in most jurisdictions may be indicative of processes of resilience at the individual, social network, and/or community system levels, because older adults appeared to either find ways to cope with restrictions, or increased supports were provided to them through their social and community networks. Loosening of pandemic restrictions in some jurisdictions may also have stabilized or reduced the observed patterns of loneliness. Further research is required to determine the causes of the observed declines or levelling of loneliness.

A smaller number of studies reported on levels of social isolation during the pandemic. In the longitudinal study by Kotwal et al. (Reference Kotwal, Holt-Lunstad, Newmark, Cenzer, Smith and Covinsky2021) levels of social isolation ranged from 33 to 49 per cent during the pandemic and were highest during the first periods of data collection. Herrera et al. (Reference Herrera, Elgueta, Fernández, Giacoman, Leal and Marshall2021) in Chile found that social isolation scores had decreased during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic. In a cross-sectional survey, Gaeta and Brydges (Reference Gaeta and Brydges2020) reported that 56 per cent of older adults felt isolated; however, this report was based on the subjective perceptions of social isolation among older adults rather than an objective measure, such as levels of contact or network size. In an Australian study, Strutt et al. (Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021) reported that 20 per cent of older adults had a limited social network during the pandemic. Additionally, other studies reported that between 43 and 69 per cent of older adults were engaging in self-isolation or strict social distancing (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mossabir, Harrison, Brundle, Smith and Clegg2021; Emerson, Reference Emerson2020; Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, O’Shea, Kler, Nishimura, Palavicino-Maggio and Eastman2021; Lehtisalo et al., Reference Lehtisalo, Palmer, Mangialasche, Solomon, Kivipelto and Ngandu2021; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Reininghaus and Riedel-Heller2020).

Factors Associated with Social Isolation and Loneliness during the Pandemic

Twenty-four studies reported on factors associated with loneliness or social isolation during the pandemic (almost all focused on associations with loneliness, and only a few examined social isolation) (see Table 2). Furthermore, most of the factors identified were risk factors ("risk" means an increase in the likelihood of experiencing loneliness and social isolation based on a particular factor), rather than protective factors. Our findings are organized in the following sections based on the domains of SE model; studies primarily focused on the individual level, with some attention also paid to interpersonal and policy level factors.

At the individual level, key factors that were reported in articles included age, gender (binary), subjective perceptions of aging, and health conditions. In the studies reviewed, associations with age and gender were equivocal. Gender (being female) was associated with higher rates of loneliness in some studies (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Farina, Wu and Ailshire2021; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Reininghaus and Riedel-Heller2020; Whatley, Siegel, Schwartz, Silaj, & Castel, Reference Whatley, Siegel, Schwartz, Silaj and Castel2020; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong2020), but not in others (e.g., Cihan & Gökgöz Durmaz, Reference Cihan and Gökgöz Durmaz2021; Parlapani et al., Reference Parlapani, Holeva, Nikopoulou, Sereslis, Athanasiadou and Godosidis2020; Polenick et al., Reference Polenick, Perbix, Salwi, Maust, Birditt and Brooks2021). When comparing segments of the older adult population, some studies found that more advanced age was associated with greater loneliness (Cihan & Gökgöz Durmaz, Reference Cihan and Gökgöz Durmaz2021; Lehtisalo et al., Reference Lehtisalo, Palmer, Mangialasche, Solomon, Kivipelto and Ngandu2021), whereas other studies reported the opposite pattern (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Farina, Wu and Ailshire2021; Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, O’Shea, Kler, Nishimura, Palavicino-Maggio and Eastman2021). Other studies reported higher levels of social isolation (Birditt et al., Reference Birditt, Turkelson, Fingerman, Polenick and Oya2021), but not loneliness among older adults compared to younger age groups (Losada-Baltar, Jiménez-Gonzalo, et al., Reference Losada-Baltar, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Gallego-Alberto, Pedroso-Chaparro, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2021, Luchetti et al., Reference Luchetti, Lee, Aschwanden, Sesker, Strickhouser and Terracciano2020; Minahan, Falzarano, Yazdani, & Siedlecki, Reference Minahan, Falzarano, Yazdani and Siedlecki2021). In a comparison of older and younger age groups Luchetti et al. (Reference Luchetti, Lee, Aschwanden, Sesker, Strickhouser and Terracciano2020) found that only older adults experienced a statistically significant increase in levels of loneliness during the pandemic. Older subjective age (Schorr et al. Reference Schorr, Yehuda and Tamir2021b; Shrira et al., Reference Shrira, Hoffman, Bodner and Palgi2020) and negative perceptions about aging (Losada-Baltar, Jiménez-Gonzalo, et al., Reference Losada-Baltar, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Gallego-Alberto, Pedroso-Chaparro, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2021; Whatley et al., Reference Whatley, Siegel, Schwartz, Silaj and Castel2020) were identified as risk factors associated with loneliness. Additionally, multiple chronic conditions and poor health were risk factors for loneliness (Whatley et al., Reference Whatley, Siegel, Schwartz, Silaj and Castel2020; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong2020). Protective factors identified at the individual level included: being a person of color (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Farina, Wu and Ailshire2021; Polenick et al., Reference Polenick, Perbix, Salwi, Maust, Birditt and Brooks2021) and individual resilience, based on perceived ability to cope with stress (Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Reininghaus and Riedel-Heller2020).

Loneliness was also associated with several individual risk factors that related specifically to the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic and extended across micro, meso, and macro domains of the SE model. These included: experiencing personal losses (Van Tilburg et al., Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries2020), financial strain (Polenick et al., Reference Polenick, Perbix, Salwi, Maust, Birditt and Brooks2021), COVID-19 anxiety or worries (Gaeta & Brydges, Reference Gaeta and Brydges2020; Kivi et al., Reference Kivi, Hansson and Bjälkebring2021; Polenick et al., Reference Polenick, Perbix, Salwi, Maust, Birditt and Brooks2021; Van Tilburg et al., Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries2020), intolerance of uncertainty (Parlapani et al., Reference Parlapani, Holeva, Nikopoulou, Sereslis, Athanasiadou and Godosidis2020), being a relative of a healthcare worker (Cihan & Gökgöz Durmaz, Reference Cihan and Gökgöz Durmaz2021), and having a family member infected with COVID-19 (Cihan & Gökgöz Durmaz, Reference Cihan and Gökgöz Durmaz2021).

Living alone was consistently identified as an interpersonal level risk factor associated with higher rates of loneliness during the pandemic (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Farina, Wu and Ailshire2021; Cihan & Gökgöz Durmaz, Reference Cihan and Gökgöz Durmaz2021; Emerson, Reference Emerson2020; Fingerman et al., Reference Fingerman, Ng, Zhang, Britt, Colera and Birditt2021; Lehtisalo et al., Reference Lehtisalo, Palmer, Mangialasche, Solomon, Kivipelto and Ngandu2021; Parlapani et al., Reference Parlapani, Holeva, Nikopoulou, Sereslis, Athanasiadou and Godosidis2020; Stolz et al., Reference Stolz, Mayerl and Freidl2021; Strutt et al., Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong2020). However, a study by Heidinger and Richter (Reference Heidinger and Richter2020) reported a heightening in reported loneliness during the pandemic among older individuals living with others but not in those living alone. Living alone also was associated with not having in-person contact with others during the pandemic (Fingerman et al., Reference Fingerman, Ng, Zhang, Britt, Colera and Birditt2021). Identified interpersonal protective factors included: social support (Polenick et al., Reference Polenick, Perbix, Salwi, Maust, Birditt and Brooks2021), living with others (Polenick et al., Reference Polenick, Perbix, Salwi, Maust, Birditt and Brooks2021; Van Tilburg et al., Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries2020), stronger social networks (Strutt et al., Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021), more social interactions (Macdonald & Hülür, Reference Macdonald and Hülür2021), and satisfaction with communication (Macdonald & Hülür, Reference Macdonald and Hülür2021).

At the policy level, several studies investigated the relationship between pandemic restrictions and loneliness. Choi et al. (Reference Choi, Farina, Wu and Ailshire2021) found the following aspects of social distancing are associated with loneliness: cancelling/postponing social activities and avoiding close contact with people in the household. In a study by Stolz et al. (Reference Stolz, Mayerl and Freidl2021) older adults were asked whether they had been negatively affected by seven types of pandemic restrictions; reporting more negative exposures to pandemic restrictions was associated with higher levels of loneliness. Self-isolating and reduced social interactions were also associated with loneliness (Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Reininghaus and Riedel-Heller2020; Strutt et al., Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021; van Tilburg et al., Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries2020), but few studies focused exclusively on social isolation.

The risk factors associated with loneliness during the pandemic underscore the relevance of the SE domains of influence (particularly at the individual and interpersonal levels). The combination of risk (e.g., living alone) and protective factors (e.g., social support, satisfaction with communication) indicate that interpersonal factors, in particular, likely play a role in fostering resilience to loneliness. The research also suggests that targeted interventions are needed to enhance the resilience and adaptability of older adult populations who are vulnerable to loneliness (e.g., older adults living alone, older adults experiencing multi-morbidity).

Effects of Social Isolation and Loneliness on Older Adults during the Pandemic

Fourteen studies reported on potential negative effects of social isolation and loneliness on older adults during the pandemic (see Table 2). It is important to acknowledge that most of the studies included in this section are cross-sectional (n = 11); therefore, the directionality of associations cannot be conclusively determined.

Multiple studies reported that perceived loneliness during the pandemic was associated with depression (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Elgueta, Fernández, Giacoman, Leal and Marshall2021; Kotwal et al., Reference Kotwal, Holt-Lunstad, Newmark, Cenzer, Smith and Covinsky2021; Krendl & Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021; Mistry et al., Reference Mistry, Ali, Hossain, Yadav, Ghimire and Rahman2021; Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh and McKeand2020; Schorr et al., Reference Schorr, Yehuda and Tamir2021a; Shrira et al., Reference Shrira, Hoffman, Bodner and Palgi2020; Strutt et al., Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021) and anxiety (Kılınçel et al., Reference Kılınçel, Muratdağı, Aydın, Öksüz and Büyükdereli Atadağ2020; Kotwal et al., Reference Kotwal, Holt-Lunstad, Newmark, Cenzer, Smith and Covinsky2021; Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh and McKeand2020; Shrira et al., Reference Shrira, Hoffman, Bodner and Palgi2020). However, one Spanish study reported no associations with anxiety and depression; the null finding may have been related to their choice of measurement of loneliness (living alone rather than a validated scale or a loneliness-specific question) (García-Fernandez, Romero-Ferreiro, López-Roldán, Padilla, & Rodriguez-Jimenez, Reference García-Fernández, Romero-Ferreiro, López-Roldán, Padilla and Rodriguez-Jimenez2020). Studies also found that loneliness was associated with sleep problems (Grossman, Hoffman, Palgi, & Shrira, Reference Grossman, Hoffman, Palgi and Shrira2021), poor quality of life (Strutt et al., Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021), peritraumatic stress (Shrira et al., Reference Shrira, Hoffman, Bodner and Palgi2020), and psychological distress (Strutt et al., Reference Strutt, Johnco, Chen, Muir, Maurice and Dawes2021).

On the other hand, studies focusing on the effects of social isolation on depression and anxiety during the pandemic have been equivocal. Several studies showed no effects of social isolation on these psycho-social outcomes (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Elgueta, Fernández, Giacoman, Leal and Marshall2021; Kotwal et al., Reference Kotwal, Holt-Lunstad, Newmark, Cenzer, Smith and Covinsky2021; Minahan et al., Reference Minahan, Falzarano, Yazdani and Siedlecki2021). In contrast, a Bangladeshi study identified social isolation as being positively associated with depression (Mistry et al., Reference Mistry, Ali, Hossain, Yadav, Ghimire and Rahman2021). In addition, in an analysis of data from 62 countries, Kim and Jung (Reference Kim and Jung2021) found that social distancing was associated with COVID-19 related psychological distress. Furthermore, a qualitative study conducted with older adults with cognitive impairments who lived alone found that participants were experiencing significant psychological distress as a result of pandemic isolation (Portacolone et al., Reference Portacolone, Chodos, Halpern, Covinsky, Keiser and Fung2021).

Whitehead and Torossian (Reference Whitehead and Torossian2021) asked older adults to identify sources of stress in their lives during the pandemic, and loneliness/isolation was the third most frequently identified stressor. Comparison of the responses of different demographic groups revealed that older women, low-income older adults, and single/widowed older adults ranked loneliness/isolation as their number one stressor.

Strategies to Reduce Social Isolation and Loneliness during the Pandemic

The complex systems resilience framework identifies the need to respond to pandemic adversity and foster strengths to build resilience. Twenty articles were identified discussing strategies for reducing social isolation and/or loneliness during the pandemic among older adult populations. (See the next section for examples of interventions). Most articles focused on strategies at the individual and interpersonal levels, rather than opportunities for intervening at higher system levels (e.g., changes to policy, community-level approaches). Only two articles specifically focused on strategies to address social isolation (Dassieu & Sourial, Reference Dassieu and Sourial2021; Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith2020) and three specifically focused on strategies to address on loneliness (Burke, Reference Burke2020; Conroy, Krishnan, Mittelstaedt, & Patel, Reference Conroy, Krishnan, Mittelstaedt and Patel2020; Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2021), while the remaining articles discussed strategies to address social isolation, loneliness, and related concepts in conjunction. Because of the significant overlap in the literature, most of the strategies will be described as potentially having applicability for addressing both social isolation and loneliness, although distinctions are made as appropriate.

Technology was frequently discussed in the literature as an essential component for innovative approaches to address social isolation and loneliness and was the core focus of half of the articles reviewed (n = 10). In the literature, technology-focused strategies for addressing social isolation and loneliness were described in multiple domains of the SE model. At the individual level, technology was positioned as a means to build the resilience of older adults by increasing their access to social support, information, and resources during the pandemic. Education and training for older adults on the use of digital technology was emphasized as necessary for technology-based interventions to be successful at reducing social isolation and loneliness (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Krishnan, Mittelstaedt and Patel2020; Daly et al., Reference Daly, Depp, Graham, Jeste, Kim and Lee2021; Day, Gould, & Hazelby, Reference Day, Gould and Hazelby2020; Seifert, Cotten, & Xie, Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021). Peer or intergenerational training programs were suggested as ways to teach older adults how to use digital technologies (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Depp, Graham, Jeste, Kim and Lee2021; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Charness, Fingerman, Kaye, Kim and Khurshid2020). At the interpersonal level, Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020) contend that older adults need to use technology to engage in “distanced connectivity” during the pandemic. A narrative review by Gorenko, Moran, Flynn, Dobson, and Konnert (Reference Gorenko, Moran, Flynn, Dobson and Konnert2021) identified the following types of remotely delivered interventions as being efficacious and feasible for use during the pandemic: telephone befriending (i.e., older adults are matched with volunteers for regular phone calls), the Senior Centre Without Walls (SCWW) model (i.e., social and educational programs provided virtually or by telephone), and programs that provide training to older adults on how to use the Internet and social media. It has also been recommended that digital technology be used to facilitate social visits, group activities, and health promotion interventions during the pandemic (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Krishnan, Mittelstaedt and Patel2020; Daly et al., Reference Daly, Depp, Graham, Jeste, Kim and Lee2021; Sepúlveda-Loyola et al., Reference Sepúlveda-Loyola, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Pérez-Rodríguez, Ganz, Torralba and Oliveira2020; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Charness, Fingerman, Kaye, Kim and Khurshid2020). Hajek and König (Reference Hajek and König2020) reviewed the small number of studies evaluating the effectiveness of social media use for reducing social isolation or loneliness among older adults; two studies observed no impacts, while one found lower social isolation scores.

Authors also discussed the “digital divide”, a meso level challenge that connects the individual and organizational/policy domains of the SE model. The term “digital divide” is used to highlight the challenge that not all older adults have access to or use the Internet and digital technologies, and certain groups are in danger of being further excluded from society because of the increasing reliance on digital technologies during the pandemic (e.g., low-income older adults, people living in rural areas, the oldest age groups, older adults with functional impairments or multi-morbidity) (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Krishnan, Mittelstaedt and Patel2020; Seifert et al., Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021; Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith2020; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020). Recommended steps to address the challenges posed by the digital divide included: (1) offering some low-tech interventions such as telephone and mail interventions (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Krishnan, Mittelstaedt and Patel2020; Seifert et al., Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020), (2) ensuring access to low-cost, high-speed Internet for all older adults (Seifert et al., Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021), and (3) developing technologies that are accessible to older adults with low technology literacy levels and functional impairments (Seifert et al., Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021).

In addition to technology-based strategies, a range of additional approaches were discussed in the literature to address social isolation and loneliness. Recommended strategies to build upon the strengths and resilience of individuals included: encouraging participation in more outdoor activities (Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2021; Day et al., Reference Day, Gould and Hazelby2020; Hwang, Rabheru, Peisah, Reichman, & Ikeda, Reference Hwang, Rabheru, Peisah, Reichman and Ikeda2020), culturally and religiously grounded interventions (Giwa, Mullings, & Karki, Reference Giwa, Mullings and Karki2020), and creative arts (Day et al., Reference Day, Gould and Hazelby2020). Psychological interventions (e.g., one-on-one interventions, cognitive behavioural therapy, meditation, life review therapy) were also recommended specifically to address loneliness (Conroy et al, Reference Conroy, Krishnan, Mittelstaedt and Patel2020; Gorenko et al., Reference Gorenko, Moran, Flynn, Dobson and Konnert2021; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Bower, Lutz, Silva, Gallegos and Podgorski2020).

In the literature, interpersonal level strategies for addressing social isolation and loneliness focused on providing opportunities for human and non-human companionship. Burke (Reference Burke2020) observed that the pandemic has reduced opportunities for natural intergenerational interactions. Programs that foster intergenerational connections were identified as important components of COVID-19 responses (Burke, Reference Burke2020; Day et al., Reference Day, Gould and Hazelby2020; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Charness, Fingerman, Kaye, Kim and Khurshid2020). Sepúlveda-Loyola et al. (Reference Sepúlveda-Loyola, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Pérez-Rodríguez, Ganz, Torralba and Oliveira2020) have also emphasized the importance of staying connected with family. Social robots and pets have been proposed as forms of non-human companionship to reduce both social isolation and loneliness among older adult populations (though some might question the impact they would have on social isolation and whether one can have social interactions and relationships with a non-human companion). Although currently robots are not advanced enough to act as close friends, they can be used for entertainment and companionship purposes which may be beneficial given the lack of options for in-person contact during the pandemic (Henkel, Čaić, Blaurock, & Okan, Reference Henkel, Čaić, Blaurock and Okan2020; Jecker, Reference Jecker2020). Pets were also highlighted as an important form of non-human companionship by Rauktis and Hoy-Gerlach (Reference Rauktis and Hoy-Gerlach2020), who suggest that steps may need to be taken to support older pet owners during the pandemic (e.g., assistance with shopping for pet food). Media reports show that pet adoption increased significantly during the pandemic (e.g., Cotnam, Reference Cotnam2020), which may be a result of Canadians seeking to address social needs through non-human companionship.

At the organizational system level, it has been observed that given the unique circumstances of the pandemic traditional approaches for prevention and identifying people who are socially isolated or lonely may need to be altered (Dassieu & Sourial, Reference Dassieu and Sourial2021; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020). For health care organizations, health care professionals were identified as having a role to play in addressing social isolation and loneliness through home visits for assessment and prevention initiatives (Day et al., Reference Day, Gould and Hazelby2020), the development of social connection plans with older adults (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Bower, Lutz, Silva, Gallegos and Podgorski2020), and online group health interventions (Day et al., Reference Day, Gould and Hazelby2020). Providing volunteering opportunities to older adults may also reduce social isolation and loneliness, while also magnifying the capacity of organizations (Wu, Reference Wu2020; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Charness, Fingerman, Kaye, Kim and Khurshid2020). Indeed, volunteering became a fulcrum for the successful implementation of many programs that needed to pivot during the pandemic.

Interventions Implemented to Reduce Social Isolation and Loneliness during the Pandemic

A small number of articles (n = 9) described the development and/or evaluation of interventions that had been implemented during the pandemic to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults. Interventions were deemed to be targeting social isolation and loneliness based on consideration of their target populations, descriptions of the programs and program theories, and pre-existing knowledge of interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness. Six of the studies described interventions implemented in the United States, two described interventions implemented in Israel, and one described interventions implemented in in Canada (discussed subsequently in this article). Whereas the articles on Zoom-based group interventions linked the interventions primarily to the aim of reducing loneliness, the articles on befriending programs and telephone outreach suggest applicability for reducing social isolation and/or loneliness. The interventions primarily targeted individual and interpersonal domains of the SE model.

Four of the articles described befriending programs that matched volunteers (most often university students) with isolated/lonely older adults for regular telephone or virtual calls (Dikaios et al., Reference Dikaios, Sekhon, Allard, Vacaflor, Goodman and Dwyer2020; Joosten-Hagye, Katz, Sivers-Teixeira, & Yonshiro-Cho, Reference Joosten-Hagye, Katz, Sivers-Teixeira and Yonshiro-Cho2020; Lewis & Strano-Paul, Reference Lewis and Strano-Paul2021; Office, Rodenstein, Merchant, Pendergrast, & Lindquist, Reference Office, Rodenstein, Merchant, Pendergrast and Lindquist2020). The articles suggested that the connections formed through befriending programs can reduce social isolation and/or loneliness or mitigate their negative effects. However, none of the studies directly measured or planned to measure whether the interventions affected levels of social isolation or loneliness. A pre-post test evaluation (Joosten-Hagye et al., Reference Joosten-Hagye, Katz, Sivers-Teixeira and Yonshiro-Cho2020) and anecdotal evidence from the volunteers (Office et al., Reference Office, Rodenstein, Merchant, Pendergrast and Lindquist2020; Lewis & Strano-Paul, Reference Lewis and Strano-Paul2021) suggest that the calls resulted in positive connections between the volunteers and older adults.

Two articles described telephone outreach programs in which staff or volunteers conduct check-ins with isolated older adults. One article was a process evaluation of a virtual training program for older adult volunteers in a telephone outreach program (Lee, Fields, Cassidy, & Feinhals, Reference Lee, Fields, Cassidy and Feinhals2021), while the other article reported on a telephone outreach program established by the Health Black Elders Centre for their members (Rorai & Perry, Reference Rorai and Perry2020). Anecdotally it was reported that older adults viewed the calls positively and some were able to be referred/connected to needed services.

Three articles described Zoom-based group interventions that aimed to serve as a substitute for in-person group activities and provide opportunities for social interaction. Shapira et al. (Reference Shapira, Yeshua-Katz, Cohn-Schwartz, Aharonson-Daniel, Sarid and Clarfield2021) conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial of a seven-session cognitive behavioural therapy Zoom group (n = 64 intervention group, n = 18 comparison group). The intervention group had a statistically significant decrease in loneliness scores post-intervention compared with the comparison group, although further studies are needed. Cohen-Mansfield, Muff, Meschiany, and Lev-Ari (Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Muff, Meschiany and Lev-Ari2021) surveyed participants and non-participants in Zoom activities offered by a health rehabilitation company. They found that only 16 per cent of participants specifically participated to relieve loneliness; however, 42 per cent thought that social contact should be a core component of activities. Physical activity, relief from boredom, and loneliness and social interaction needs were the central factors motivating participation in the programs. An article by Zubatsky (Reference Zubatsky2021) describes three group health promotion programs that have proven effective in in-person settings and were transitioned to virtual delivery during the pandemic: A Matter of Balance, Cognitive Stimulation Therapy, and Circle of Friends. The article does not include any evaluation of the virtual versions of these programs, but presumably programs that have proven effective in person could be effective in virtual settings provided they were appropriately retrofitted. Further research to confirm the effectiveness of these programs in virtual settings would be beneficial.

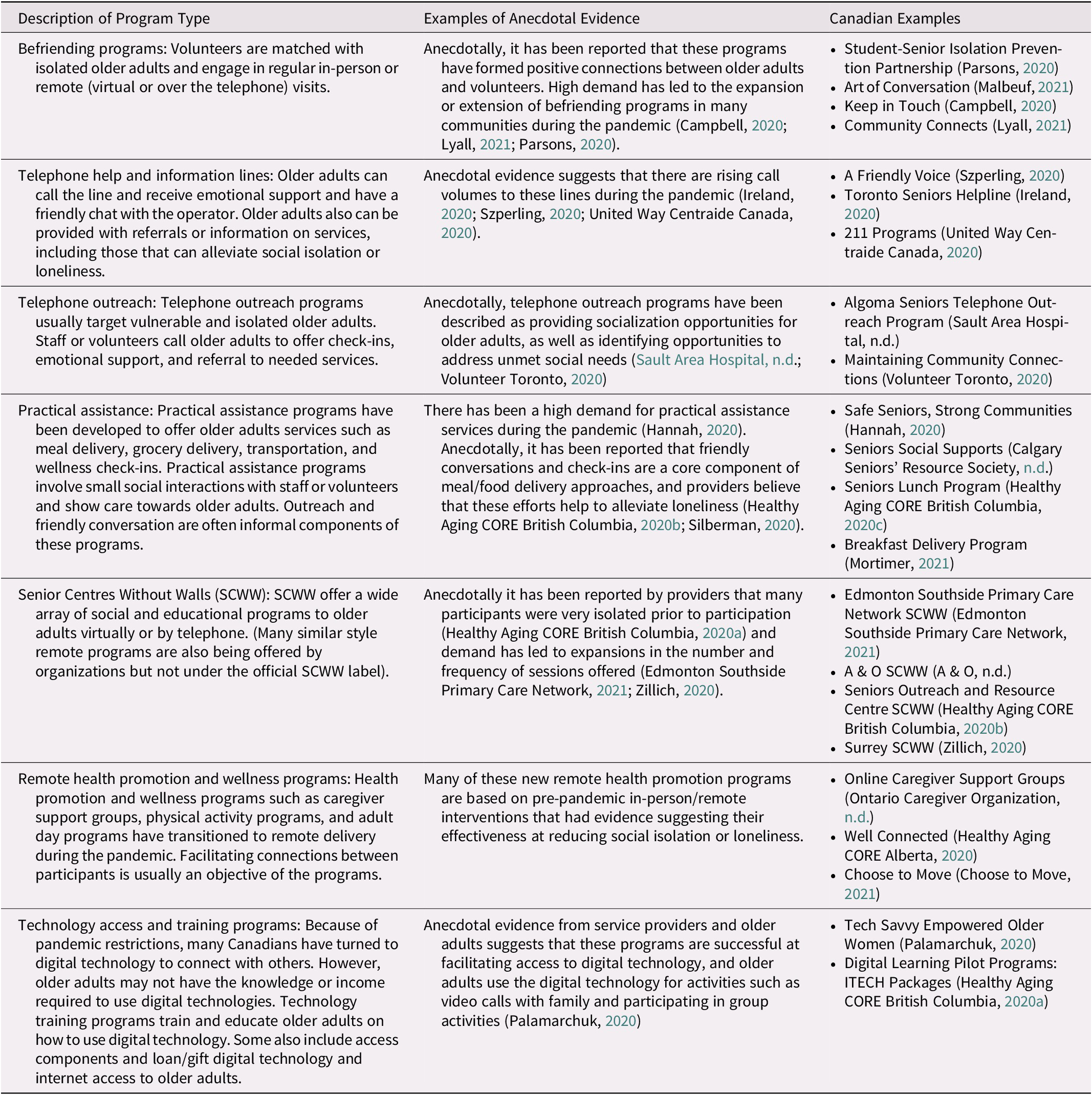

Although only one Canadian academic article was found, a supplementary scan of the Canadian grey literature identified seven common types of programs that were being implemented/utilized to reduce social isolation and loneliness among the older adult population during the pandemic: befriending programs, telephone help and information lines, telephone outreach, practical assistance, Senior Centre Without Walls, remote health promotion and wellness programs, and technology access and training programs. Table 3 describes the type of program, anecdotal evidence on benefits or demand for the program during the pandemic, and a selection of Canadian program examples. Many programs identified were being delivered by non-profit and voluntary organizations (e.g., see Hannah, Reference Hannah2020; Campbell, Reference Campbell2020; A & O, n.d.), but programs were also delivered by other groups such as health care organizations (e.g., Sault Area Hospital, n.d.) and student groups (e.g., Parsons, Reference Parsons2020). Volunteers usually played a role in befriending, practical assistance, telephone outreach, and telephone line programs. The review of the grey literature also reveals the strong reliance on both low-tech (e.g., telephone) and high-tech (e.g., Zoom) interventions. Anecdotally, evidence suggests high demand for most of these programs during the pandemic as well as perceptions by service providers or older adults of positive impacts (see Table 3), although further research is required to determine whether they are reducing social isolation and loneliness. As will be described in the Discussion, pre-pandemic literature provides evidence of the effectiveness of some of these programs at reducing loneliness or social isolation.

Table 3. Canadian examples of programs to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults

Discussion

Data from the CLSA have revealed significant increases in levels of loneliness among Canadian older adults during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic times. These findings are in line with the findings from international longitudinal studies (e.g., Krendl & Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021; Macdonald & Hülür, Reference Macdonald and Hülür2021; Van Tilburg et al., Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries2020; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong2020), although the levels of increase in loneliness vary considerably. Two notable outliers were Chile (mixed results) and Sweden (no significant differences in levels of loneliness). The findings from Sweden are likely a result of the unique “herd immunity” approach Sweden has adopted during the pandemic, and the lack of measures in place limiting socialization and gatherings (Claeson & Hanson, Reference Claeson and Hanson2021). The reasons for the mixed results in Chile are less clear given that COVID-19 restrictions have been in place; the authors suggest that high rates of smartphone use and close contact with family members may have influenced these results (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Elgueta, Fernández, Giacoman, Leal and Marshall2021).

Longitudinal studies conducted peri-pandemic generally suggested that loneliness levels have been relatively stable during the pandemic, often with a spike during the initial implementation of lock-down/stay-at-home orders, followed by a levelling off. This is possibly indicative of processes of resilience among older adults, in which past experiences of adversity, greater access to support systems, and/or changing perceptions of social connections enhanced their ability to cope with pandemic mitigation policies and other pandemic-related constraints. For example, Igarashi et al. (Reference Igarashi, Kurth, Lee, Choun, Lee and Aldwin2021) found that 93 per cent of their sample of older adults described experiencing vulnerabilities directly linked to the pandemic; yet, approximately two thirds identified positive responses to these adversities. Moreover, despite reporting pandemic-related isolation and challenges maintaining interpersonal relationships, older adults described the deepening of pre-existing relationships and increased appreciation for these relationships.

Living alone emerged as the most consistent risk factor associated with loneliness in the pandemic literature. This is unsurprising given that COVID-19 restrictions in many jurisdictions prohibit/limit social interactions with people from outside of the household. A review of pre-pandemic literature also found living alone was associated with loneliness (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Hazan, Lerman and Shalom2016). Given the paucity of research in the pandemic literature that examined other vulnerabilities underlying social isolation and loneliness, we can only speculate that there are likely a myriad additional risk factors at the micro, meso, and macro levels of influence based on well-established pre-pandemic research in this field.

Strong associations emerged between loneliness and depression in the pandemic literature. On the other hand, most studies did not find a relationship between social isolation and depression. Pre-pandemic literature has frequently reported associations between loneliness and depression and between social isolation and depression (Donovan & Blazer, Reference Donovan and Blazer2020). However, results for social isolation have varied depending on the measurements used. Schwarzbach Luppa, Forstmeier, König, and Riedel-Heller (Reference Schwarzbach, Luppa, Forstmeier, König and Riedel-Heller2014) found the strongest evidence of an association for the following types of measures of social isolation: social support, quality of relations, and presence of confidantes.

A limitation of the current research on patterns of social isolation and loneliness is that most studies identified only reported on social isolation and loneliness patterns during the early stages of the pandemic (i.e., March to June 2020), when COVID-19 was newly emerging and lockdown measures were particularly stringent. Additionally, studies tended to focus on patterns of loneliness and only a small number reported on patterns of social isolation. In addition, different measures of social isolation and loneliness were utilized ranging from validated scales to single-item proxies or questions on pandemic experiences. Differences in populations and pandemic restrictions and progression in jurisdictions make comparisons tenuous. Further research is required to understand how levels of social isolation and loneliness have been impacted over the long term and whether higher levels of loneliness will persist as the pandemic continues to change over time.

The literature has strongly emphasized “pandemic age-friendly” approaches to reducing social isolation and loneliness that rely on digital technology. Although digital technology is an essential component of the lives of most Canadians, pre-pandemic data suggest that one third of older Canadians do not use the Internet (Davidson & Schimmele, Reference Davidson and Schimmele2019). Rates of Internet use are particularly low for the 80 and up age group, with only two in five using the Internet (Davidson & Schimmele, Reference Davidson and Schimmele2019). To overcome this digital divide, efforts are needed to ensure that all communities have broad-band WiFi, and that all Canadians have access to low-cost high-speed Internet in their homes, as well as digital technology training and education if needed. An additional caveat that has been provided in the literature about digital technologies and other technological forms of companionship (e.g., robots) is that they can not fully replace the need for in-person contact (Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2021; Henkel et al., Reference Henkel, Čaić, Blaurock and Okan2020; Jecker, Reference Jecker2020; Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith2020). Dahlberg (Reference Dahlberg2021) also observes that in the literature there has been less focus on non-technological options such as outdoor activities and promoting neighbourliness and community.

To date, few of the interventions implemented/utilized to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adult populations during the pandemic have been the subject of formal evaluations. Pre-pandemic literature provides evidence supporting the effectiveness of some of the identified interventions. The most robust body of evidence has been connected to digital technology interventions. Reviews of the impacts of digital technology use on older adults suggest it has positive impacts on aspects of social isolation (e.g., increasing contact with family, intergenerational relationships). However, evidence specifically on the effects of digital technology interventions on loneliness has been equivocal (Chen & Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016; Damant, Knapp, Freddolino, & Lombard, Reference Damant, Knapp, Freddolino and Lombard2017; Ibarra, Baez, Cernuzzi, & Casati, Reference Ibarra, Baez, Cernuzzi and Casati2020). Furthermore, there is a paucity of literature evaluating other types of interventions. Evaluations of virtual programs for older adults conducted prior to the pandemic suggest that they can reduce social isolation (Botner, Reference Botner2018; Gorenko et al., Reference Gorenko, Moran, Flynn, Dobson and Konnert2021). Some pre-pandemic evidence also exists on the effectiveness of Senior Centre Without Walls programs (Newall & Menec, Reference Newall and Menec2015), telephone helplines (Preston & Moore, Reference Preston and Moore2019), and practical assistance programs (i.e., meal and grocery delivery) (Thomas, Akobundu, & Dosa, Reference Thomas, Akobundu and Dosa2016; Wright, Vance, Sudduth, & Epps, Reference Wright, Vance, Sudduth and Epps2015) at reducing social isolation and/or loneliness among older adult populations. One can speculate that programs with evidence of efficacy and effectiveness pre-pandemic would also be supported during the pandemic, if they have been retrofitted to address the inherent context and constraints of the pandemic environment.

Our examination of the patterns, risks, and responses to social isolation and loneliness among older individuals reveals complex systems of vulnerability and resilience occurring within the spheres of influence identified in the SE model (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner, Gauvain and Cole1994; Stokols, Reference Stokols1992; Reference Stokols2017). The SE model affords investigation into the larger policy framework that can both create social isolation and loneliness resulting from pandemic mitigation, while also offering insight into opportunities for intervention at different levels of the SE framework. It also points to the need to consider meso-level inequalities such as the digital divide, and the micro-level adjustments that individuals make in response to the pandemic. Although the literature explored micro-level (e.g., need for digital technology training), meso-level (e.g., digital divide), and macro-level (e.g., policy on high-speed Internet access) considerations for digital technology interventions, other potential interventions have not been afforded the same multi-level analysis. Future research should engage in multi-level analysis of strategies to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adult populations, as well as identifying potential disparities in access to interventions (e.g., digital technology) for marginalized groups.

Furthermore, the use of a resilience conceptualization elucidates how some individuals and groups adapt and respond positively to the adversities of the pandemic better than others (Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump, & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Trump, Linkov, Wister and Cosco2021; Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister, & Linkov, Reference Klasa, Galaitsi, Wister and Linkov2021; Wister & Speechley, Reference Wister and Speechley2020). For example, initial research suggests that older persons who exhibited proactive coping during the early waves of the pandemic were able to reduce the level of pandemic stress and improve psychological well-being (Pearman et al., Reference Pearman, Hughes, Smith and Neupert2021; Whitehead, Reference Whitehead2021). Although this work is in its infancy, a strength-based approach suggests that by identifying positive adaptations and responses to pandemic adversities, older individuals can leverage pre-existing strengths and innovative interventions can be developed that reinforce and enhance resilience. In this review, the findings on protective factors for social isolation and loneliness were limited, with the exception of several interpersonal protective elements (e.g., satisfaction with communication, social support). Further research would benefit from a greater focus on the strengths and resilience of older adults in the face of adverse circumstances (Wister et al., Reference Wister, Klasa and Linkov2022).

Several limitations of this review should be noted. First, because of the recency of the pandemic and the lag between interventions being implemented and publication of evaluation results, this review may not capture the full picture of interventions and strategies being used to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adult populations during the pandemic. The grey literature scan that was conducted attempted to address this deficit. Second, almost all of the academic literature identified were from countries other than Canada. As was illustrated with the example of Sweden, pandemic restrictions and mitigation strategies vary by jurisdiction. As a result, caution should be used when generalizing COVID-19 research from other jurisdictions to Canada. Third, the study designs, measures of social isolation and loneliness used, and populations or sub-populations under study varied and may explain some of the inconsistencies in findings.

Conclusion

Analysis of data from the CLSA, the largest representative longitudinal study of aging in Canada, has revealed striking increases in levels of loneliness among older Canadians. Review of international literature suggests that many other jurisdictions are experiencing significant increases in loneliness among older adult populations during the COVID-19 pandemic as well. To date, literature has primarily discussed and emphasized the use of technology-based interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness. However, as has been noted in the literature, a “digital divide” exists and not all older adults have access to digital technology or use the Internet. Low-tech solutions, including using telephones and volunteers to meet basic needs during lock-down phases of the pandemic, also show promise. Researchers should focus on exploring the wider array of pandemic age-friendly interventions (e.g., outdoor activities, intergenerational programs, and other outreach approaches) that may be useful for reducing social isolation and loneliness among older adult populations. Furthermore, this review has exposed the lack of evaluation of interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness even pre-pandemic, and therefore, a greater focus on evaluating such interventions is needed moving forward. Advancement of knowledge of the risk, response, and resilience embedded in the current pandemic will help us to understand the larger processes underlying these issues and to prepare for future forms of adversity facing societies.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible using the data/biospecimens collected by the CLSA. This research has been conducted using the CLSA data set Baseline Tracking v3.4 and Comprehensive v4.0, under application number 150914 (https://www.clsa-elcv.ca/). The CLSA is led by Drs. Parminder Raina, Christina Wolfson, and Susan Kirkland. We also thank Ian Fyffe for assistance with data analyses. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the CLSA or the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors Forum. The scoping review builds on a contracted literature review conducted for the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors Forum.

Funding

Funding for the CLSA is provided by the government of Canada through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under grant reference LSA 94473 and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. The current study was funded through a CIHR CLSA Catalyst Grant (RN302177 - 373073).