There is wide consensus about the benefits of breast-feeding for both mothers and infants. Breast-feeding supports optimal growth for infants, while also decreasing the risk of being underweight and obese among different populations(Reference Arifeen, Black and Caulfield1–Reference Villalpando and Lopez-Alarcon3). Other short-term and long-term health benefits for infants include a reduced risk of infection and mortality in early life(Reference Arifeen, Black and Antelman4–Reference Quigley, Kelly and Sacker7), reduced risk of developing diabetes in later life(Reference Evenhouse and Reilly8,Reference Ravelli, Van der Meulen and Osmond9) and moderate improvement in intelligence performance(Reference Lucas, Morley and Cole10,Reference Whitehouse, Robinson and Li11) . For maternal health, breast-feeding is known to decrease the risk of breast and ovarian cancers(Reference Jordan, Cushing-Haugen and Wicklund12,Reference Palmer, Viscidi and Troester13) and CVD(Reference Jäger, Jacobs and Kröger14,Reference McClure, Catov and Ness15) . Despite the WHO recommendations(Reference Kramer and Kakuma16), the global prevalence of exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months is estimated at around 37 % in low- and middle-income countries, with lower rates in high-income countries(Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros17).

A growing trend of working mothers is evident worldwide, with employment rates of mothers with children under 18 years old reported as increasing in Australia(Reference Baxter18), the USA(19) and the United Kingdom(20). Maternal employment is a known barrier for exclusive breast-feeding practice(Reference Hossain, Islam and Kamarul21,Reference Lee, Bai and Soo-Bin22) and has been shown to contribute to early discontinuation of breast-feeding(Reference Baxter, Cooklin and Smith23,Reference Villar, Santa-Marina and Murcia24) . Given the number of women participating in the workforce, it is worth investigating how to better support working mothers to breast-feed. In addition, there is evidence that support for breast-feeding by fathers has a strong influence on the duration of breast-feeding(Reference Arora, McJunkin and Wehrer25–Reference Rempel and Rempel28). Workplace programmes for male employees as expectant fathers are potential strategies to balance the work–family conflict and to increase the involvement of fathers(Reference Kobayashi and Usui29).

Although a number of interventions have focused on the promotion of breast-feeding in the hospital and community setting(Reference Sinha, Chowdhury and Sankar30), there is limited research on the effectiveness of interventions to support breast-feeding in the workplace. A recent systematic review restricted to randomised controlled trials found no studies reporting workplace interventions(Reference Abdulwadud and Snow31). Another descriptive review found that the provision of a lactation space was the most common support offered in the workplace, with many employers also offering breast-feeding breaks and lactation support programmes; however, the effectiveness of these interventions was not evaluated(Reference Dinour and Szaro32). Given the increasing number of women participating in the workforce, how to better support working mothers to breast-feed needs further investigation. The current study aimed to critically review the literature regarding workplace interventions for supporting breast-feeding among employed parents and to assess their effectiveness for supporting breast-feeding.

Method

A systematic review of the literature was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33) and was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42018103009).

Inclusion criteria were studies: (1) that described workplace intervention studies which support breast-feeding;(2) that measured at least one outcome of interest, including primary outcomes (any breast-feeding indicators) or secondary outcomes (mother-related, infant-related and employment-related benefits); (3) of any study design except case studies; and (4) of any date of publication or language. Exclusion criteria were (1) non-intervention studies; (2) interventions not specifically focused on breast-feeding; (3) interventions delivered off-site and not specifically supported by the employer; (4) studies only reporting intention, attitude and knowledge outcomes; and (5) case study design.

Eight electronic databases were searched, including PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, CENTRAL, Web of Science, Business Source Complete, ProQuest-Sociology and ProQuest-Social Science for relevant articles up to and including 16 June 2018, and further updated on 13 April 2020. The search strategy in PubMed was (Breastfeeding OR ‘breast milk’ OR ‘human milk’ OR breastfe* OR breast fe* OR lactati* OR ‘Breast Feeding’(Mesh) OR ‘Milk, Human’(Mesh)) AND (Workplace OR work OR employ* OR organisation* OR organization* OR occupation OR “Return to Work“(Mesh) OR ‘Employment’(Mesh)) AND (Intervention OR support OR program OR counselling OR peer OR education OR ‘family practice’) and was adapted to suit each of the different databases (see online supplementary material, search strategy). References of relevant reviews retrieved in the search were also checked to find additional studies.

All search results were imported into EndNote X8 and de-duplicated prior to screening. Two reviewers (X.T. and P.P.) independently screened the title and abstract for articles, with disagreements resolved by consensus or a third reviewer (K.M.S.). The full text of all articles not excluded at title and abstract stage was further independently assessed by two authors (X.T. or P.P. and D.R., J.B. or L.v.H.) against the inclusion criteria. Quality assessment of included studies was undertaken independently by two reviewers (X.T. and K.M.S. or L.v.H.), with disagreements resolved by consensus or a third reviewer (D.R.) using the Mixed Method Assessment Tool (MMAT)(Reference Pluye, Robert and Cargo34). For cross-sectional studies, the Quantitative Descriptive Domain (MMAT Domain 3.0) was used when all subjects received a programme and results only indicated the association between subject characteristics and outcomes, while the Quantitative Nonrandomised Domain (MMAT Domain 4.0) was used when the association between the programme exposure and outcomes was reported.

Data were extracted by one author (X.T.) and checked for accuracy by a second author and included source (review author, citation and contact details), study design, settings with context, participants, duration, follow-up time, programme details, delivery modes, method of data collection, measures, data analysis, results and conclusions. Mean, sd or 95 % CI for continuous outcomes and OR or 95 % CI for categorical outcomes were extracted for analysis. A meta-analysis was conducted where at least two similar quantitative studies with homogenous outcome measures were reported. The package meta in R statistical software version 3.5.3 was used for meta-analysis(35). Specifically, these functions were used: metamean for pooling the mean duration of breast-feeding in single-arm studies, metabin for binary outcome data comparing participants against non-participants in workplace programmes and metaprop for pooling proportions from single-arm studies. Pooling of the estimates for random effects models was carried out using the inverse variance method. Heterogeneity was assessed with the I 2 statistic. If sd were not reported in studies included for meta-analysis, the sd from a similar quantitative study was applied, as suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions(Reference Higgins and Green36). A narrative review was used to synthesise qualitative studies and quantitative studies that were not included in a meta-analysis.

Results

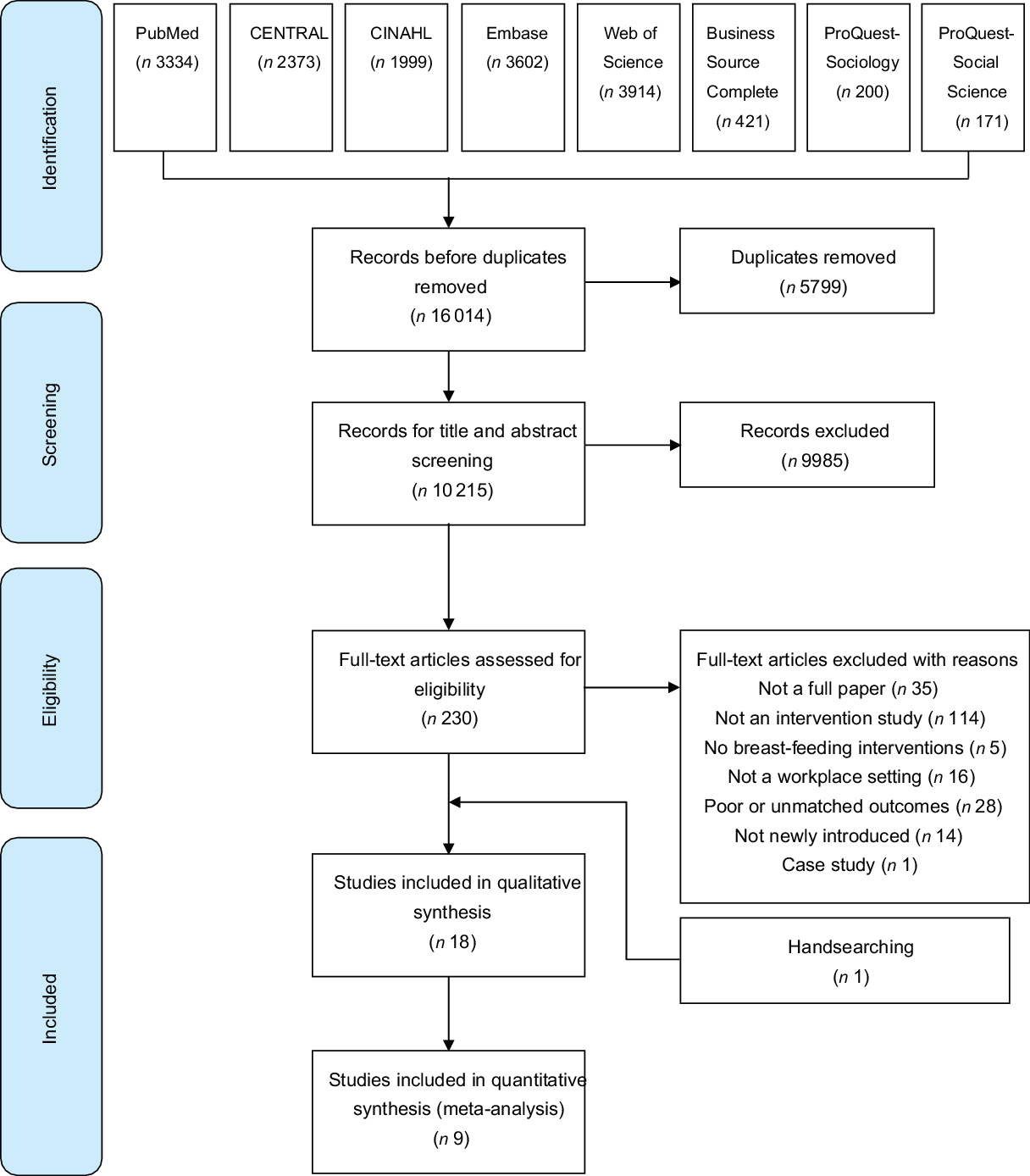

Study selection

The original and updated search combined identified 16 014 articles from the eight databases (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 10 215 articles were screened based on title and abstract. Of these, 230 articles were subject to full-text review. The most common reason for exclusion was that the study was not an intervention study. A companion paper of one included study, which was not identified in the search, was added as a result of handsearching. Fourteen studies were included and were reported across eighteen publications, of which nine out of fourteen studies were eligible to be included in the meta-analysis. Two studies(Reference Hilliard and Brunt37,Reference Katcher and Lanese38) were ineligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis due to different study designs from other included studies, one study(Reference Tsai39) was ineligible due to measuring breast-feeding rate in a different way from other included studies and two studies(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40,Reference Johnson and Salpini41) were ineligible as they were qualitative studies.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of study selection

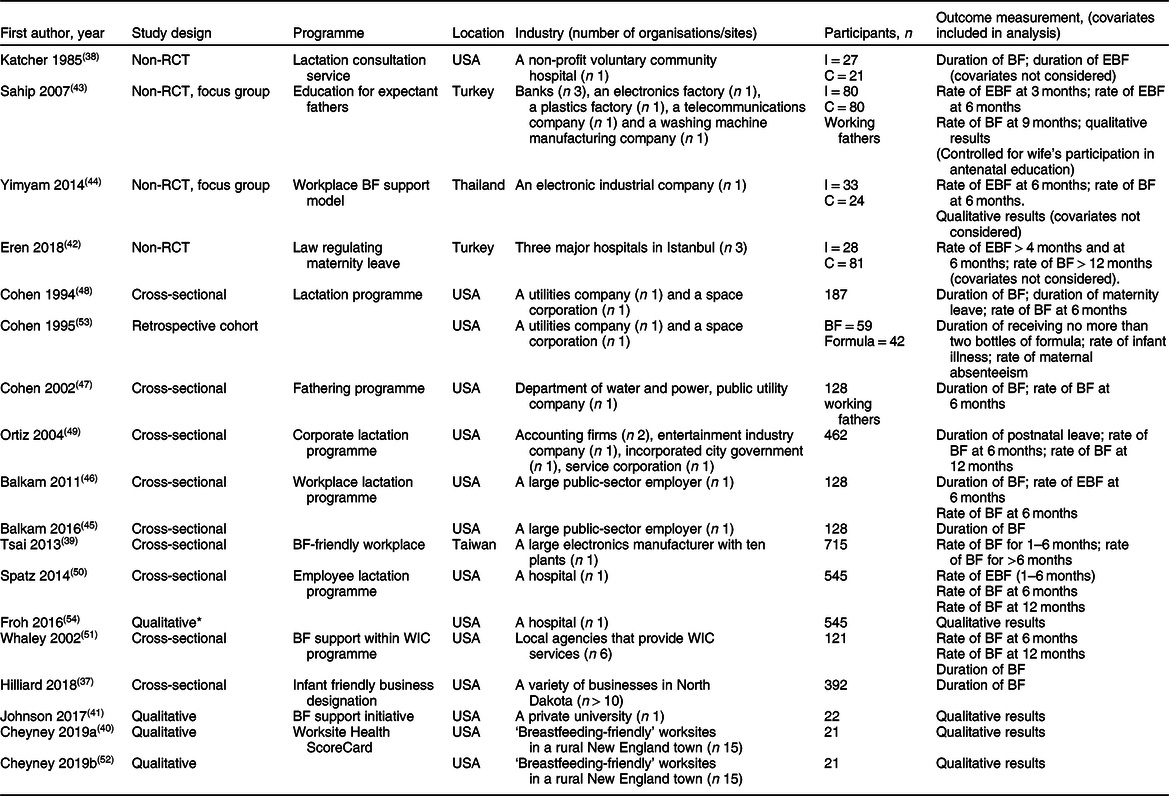

Study characteristics

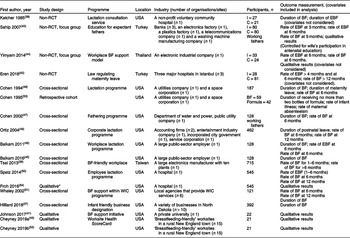

Table 1 shows an overview of the characteristics of the included studies. The majority of studies (n 10) were programmes delivered in the USA, with remaining studies reporting on programmes delivered in Turkey (n 2), Thailand (n 1) or Taiwan (n 1). Four publications were non-randomised controlled studies(Reference Katcher and Lanese38,Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42–Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) , and two of these four also included qualitative results from focus groups(Reference Sahip and Turan43,Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) . Nine publications(Reference Hilliard and Brunt37,Reference Tsai39,Reference Balkam45–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) reporting eight breast-feeding support programmes were cross-sectional studies, most of which participants had received an intervention. Three publications across two studies reported only qualitative results on women’s breast-feeding experiences(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40,Reference Johnson and Salpini41,Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan52) .

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

Non-RCT, non-randomised controlled trial; BF, breast-feeding; EBF, exclusive breast-feeding; I, intervention; C, comparison; WIC, women, infants and children programme.

* Secondary data analysis from a survey reported in Spatz 2014(Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50).

There were eight publications that represented multiple reports of four studies (Table 2). There were two reports of one intervention composed of a breast pump room and lactation consultant(Reference Cohen and Mrtek48,Reference Cohen, Mrtek and Mrtek53) . One of these reports presented cross-sectional results of infant feeding choice (formula or breast) for all participants in the programme(Reference Cohen and Mrtek48) and the other presented a comparison of maternal absenteeism and infant illness between formula-fed and breast-fed babies of mothers participating in the programme in a retrospective cohort study(Reference Cohen, Mrtek and Mrtek53). There were two reports of a comprehensive hospital employee lactation programme encompassing multiple intervention components(Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50,Reference Froh and Spatz54) . One publication presented cross-sectional breast-feeding outcome(Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50), and the other publication presented qualitative data from a survey of participants(Reference Froh and Spatz54). There were two reports of an intervention consisting of lactation consultants for employee support and access to a lactation room(Reference Balkam45,Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46) . Both reports presented cross-sectional data on duration of breast-feeding; however, one was focused on breast-feeding duration for all participants(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46) while the other described breast-feeding problems of participants and compared breast-feeding duration of employees with lactation problems against those experiencing no problems(Reference Balkam45). Finally, there were two reports of a qualitative study investigating women’s experiences of breast-feeding-friendly workplaces(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40,Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan52) . The current study reported on women’s experiences of returning to work with the findings separated into two papers, one focused on the translation of policy into practice(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40) and the other focused on the findings related to physical environment(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan52).

Table 2 Summary of workplace breast-feeding interventions reported in included studies

* Time for breast-feeding breaks was part of the second stage for the programme, but most interviewees were still in stage one.

† Personal-use breast pump purchase programme at cost for employees.

‡ Source of clean water and refrigerator.

§ Hospital personnel policy extended for the whole programme.

‖ Policy to guarantee specific break times for expressing milk.

¶ Including paid and unpaid maternity leave, and shorter working duration.

Quality assessment

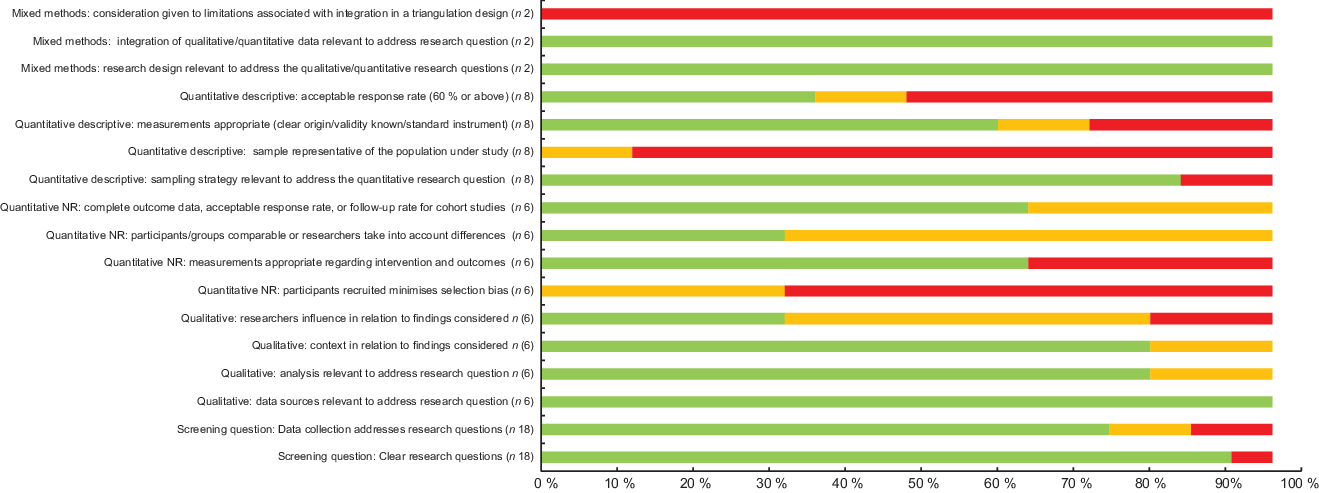

The quality of included studies was found to be variable based on the MMAT(Reference Pluye, Robert and Cargo34) (Fig. 2). Among eighteen articles assessed with the MMAT, four qualitative publications(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40,Reference Johnson and Salpini41,Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan52,Reference Froh and Spatz54) were assessed with only the ‘Qualitative Domain’ (MMAT Domain 2.0); two mixed methods studies(Reference Sahip and Turan43,Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) were assessed with MMAT Domains 2.0, 3.0 and 5.0; two quantitative non-randomised controlled trials(Reference Katcher and Lanese38,Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42) , one cross-sectional study(Reference Hilliard and Brunt37) and one retrospective cohort study(Reference Cohen, Mrtek and Mrtek53) were assessed with MMAT Domain 3.0; and the remaining eight quantitative articles(Reference Tsai39,Reference Balkam45–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) were assessed with MMAT Domain 4.0. Overall, the majority of studies were low-to-moderate quality, although the proportion of articles assessed within the ‘qualitative domain’ that met the methodological criteria was comparatively higher than the proportion of articles assessed within the ‘quantitative domain’ (i.e., the green bar represented in Fig. 2). The main criteria with a higher proportion of articles assessed as ‘Can’t tell’ or ‘No’ included questions related to selection bias of sample or how representative the sample was, triangulation of qualitative and quantitative results for mixed methods studies (MMAT Domain 5.0) and the validity of measurement tools used.

Fig. 2 Proportion of studies meeting quality assessment criteria for each of the MMAT questions. ![]() , yes;

, yes; ![]() , cannot tell;

, cannot tell; ![]() , no

, no

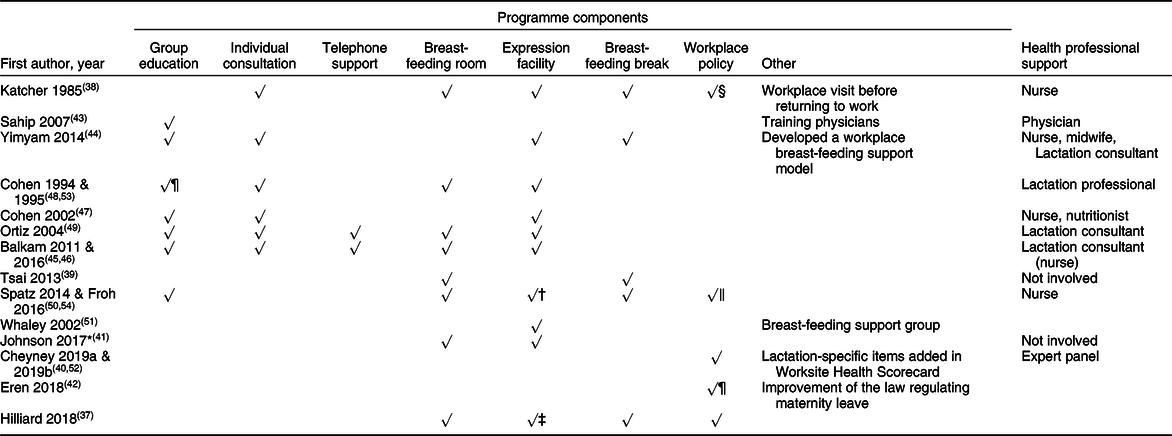

Programme summary

Most of the included studies described a comprehensive breast-feeding support programme, consisting of several components. Table 2 summarises all the components of eligible workplace programmes, incorporating one or more of the following strategies: group education, individual consultation/s, telephone support, breast-feeding space on site, provision of expression equipment, breast-feeding break/s within working day, supportive policies or supported interactions with health professionals. The most common component included was the provision of breast milk expression equipment for free or with a discount, with the equipment often provided along with the breast-feeding room. The intervention in two studies(Reference Hilliard and Brunt37,Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40,Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan52) was certifying worksites as ‘infant or breast-feeding friendly’ by developing criteria for modifying worksites. The measures were similar to those listed above, such as supportive policies and lactation room. One study(Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42) investigated the effectiveness of the improvement of the law regulating maternity leave, including extending paid and unpaid maternity leave and less working hours after returning to work.

Two of the programmes(Reference Sahip and Turan43,Reference Cohen, Lange and Slusser47) were designed for male employees as expectant fathers. The programme(Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) in the USA provided group education, individual consultation and pump rental to the partners of the employees, whereas a programme(Reference Sahip and Turan43) in Turkey focused on training worksite physicians and delivering six group education sessions covering a variety of topics.

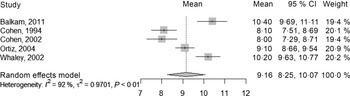

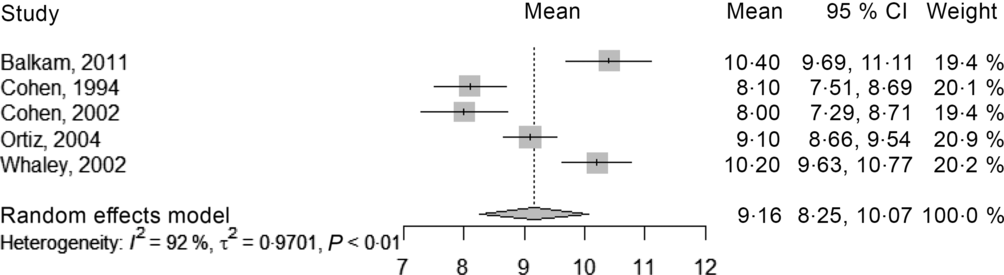

Breast-feeding duration

Seven studies across eight publications(Reference Hilliard and Brunt37,Reference Katcher and Lanese38,Reference Balkam45–Reference Cohen, Lange and Slusser47,Reference Ortiz, McGilligan and Kelly49,Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51,Reference Cohen, Mrtek and Mrtek53) reported the duration of breast-feeding and all studies reported a positive impact on breast-feeding duration. Five single-arm studies were able to be included in a meta-analysis, reporting mean duration of breast-feeding of participants ranging from 8 months to 10 months. From a sample of 896 subjects participating in a workplace breast-feeding promotion programme, the pooled mean duration of breast-feeding for five single-arm studies(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46–Reference Ortiz, McGilligan and Kelly49,Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) was 9·16 months (95 % CI 8·25, 10·07, I 2 = 92 %, Fig. 3). The I 2 of 92 % indicated high heterogeneity among these observational studies, and the potential sources of heterogeneity included the study design, the sample, the programme components and the method of data collection. The two other studies reporting duration of breast-feeding were a non-randomised controlled study(Reference Katcher and Lanese38) and a cross-sectional study with comparison of employee breast-feeding among organisations who were currently, previously or never participating in a workplace programme that included lactation support(Reference Hilliard and Brunt37). The results from these two studies were not pooled due to insufficient trials to perform a meta-analysis. These results are reported narratively.

Fig. 3 Forest plot showing the pooled mean duration (months) of breast-feeding for five single-arm studies (896 subjects)

The non-randomised study(Reference Katcher and Lanese38) (n 48, participant = 27, comparison = 21) implemented a programme that included the provision of a pump, professional advice and time during the work day for expression of breast milk and reported an average of 11·7 months of breast-feeding duration among participating employees. This was significantly higher than a mean of 6·0 months among employees on maternity leave before the implementation of the programme (P < 0·003). It reported a mean of 12·1 weeks of exclusive breast-feeding duration among participants compared with 10·6 weeks of exclusive breast-feeding duration among non-participants, without indicating whether the difference was significant.

The cross-sectional study(Reference Hilliard and Brunt37) divided participants into four groups, based on their employment at worksites designated in 2011 or 2012 and recently recertified as ‘infant friendly business’ (n 42), worksites designated later than 2012 (n 14), worksites designated in 2011 or 2012 but not recertified (n 7) and worksites not currently designated (n 147). The durations of total breast-feeding among the four groups were not significantly different (P = 0·30). The potential reason for the lack of effect was that whether a worksite was designated did not necessarily indicate the actual support in the worksite and non-designated worksites may have still offered employees breast-feeding support.

The study by Balkam et al. (Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46) was reported across two publications: the first of which was included in the meta-analysis and the second report of the current study(Reference Balkam45) was not included in the meta-analysis and had a different focus. It explored the problems experienced by women breast-feeding and participating in a workplace programme and how the problems affected their duration of breast-feeding.

Rate of exclusive breast-feeding

Five studies(Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42–Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44,Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46,Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50) reported the rate of exclusive breast-feeding. Of these, three studies(Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42–Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) were non-randomised controlled studies and two(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46,Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50) were cross-sectional studies. Sahip et al. (Reference Sahip and Turan43) reported exclusive breast-feeding at 3 months while the other four studies reported exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months. Three studies were included in a meta-analysis and reported the outcome at 3 months(Reference Sahip and Turan43) or 6 months(Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42,Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) . All three studies showed a positive effect of workplace programmes on exclusive breast-feeding, with CI suggesting significance of effect. The smaller study (n 57) included in the meta-analysis(Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) reported an OR for exclusive breast-feeding of 13·14 for participants compared with non-participants; however, the current study had a wide CI (1·57, 109·94). The other two studies(Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42,Reference Sahip and Turan43) included in the meta-analysis had smaller positive OR and narrower CI (Fig. 4). The pooled OR for participants v. non-participants of these three non-randomised controlled studies on exclusive breast-feeding at 3 or 6 months was 3·21 (95 % CI 1·70, 6·06, I 2 = 22 %, Fig. 4). In all studies, participants in workplace programmes (after improving the law regulating maternity leave in one study(Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42)) were more likely to practise exclusive breast-feeding.

Fig. 4 Forest plot of OR for exclusive breast-feeding at 3 (Sahip, 2007) or 6 months (Eren, 2018 & Yimyam, 2014) for participants v. non-participants of workplace programmes for three non-randomised controlled studies

Two cross-sectional studies measured exclusive breast-feeding but were not included in the meta-analysis, so are described narratively. The first study(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46) (n 128) reported on the usage of individual components of a multi-component workplace lactation support programme, and showed 57 % of participants who used any of the components were able to maintain exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months. The second study reported on a similar programme with multiple components in a hospital workplace(Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50) (n 545) and indicated a lower rate of exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months, at 35 % of respondents. The rate of exclusive breast-feeding decreased from 69·7 % at 1 month to 35 % at 6 months, and a critical drop was observed at 4 months, which was 50·8 %(Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50).

The study by Balkam et al. (Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46) assessed the intervention programme as well as the effectiveness of individual components in the programme. The results indicated the effectiveness of telephone support and return to work consultations for supporting exclusive breast-feeding, but not prenatal education or the availability of a lactation room. Additionally, with each increase in the number of components received, the rate of exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months was significantly higher (P < 0·05).

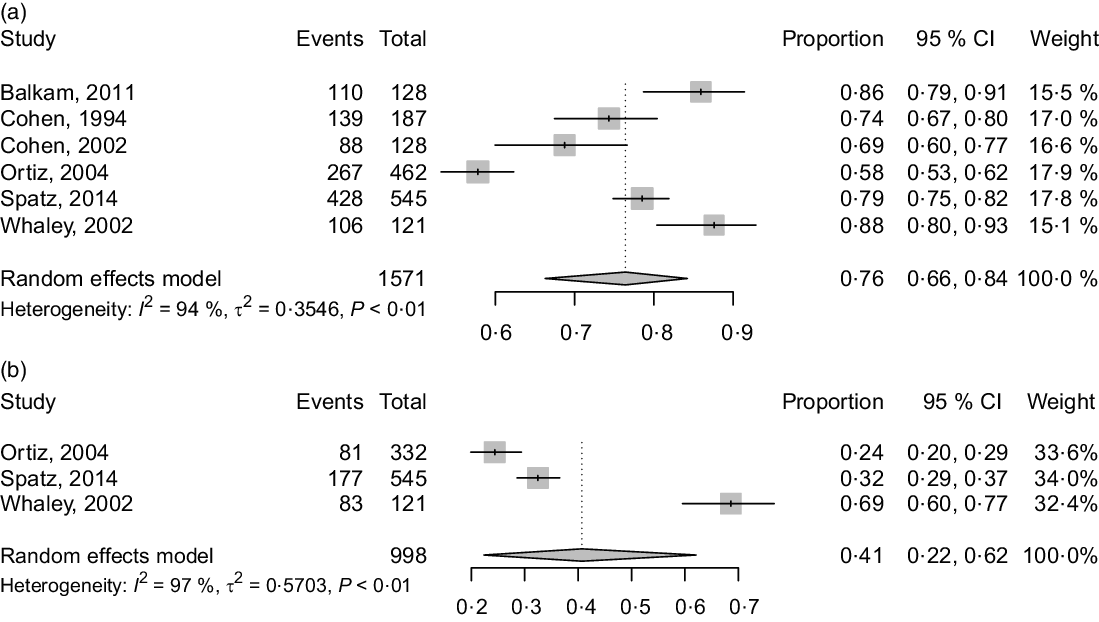

Rate of any breast-feeding

Nine studies(Reference Tsai39,Reference Sahip and Turan43,Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44,Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) reported the rate of any breast-feeding. Six of these studies(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) were included in a meta-analysis of proportion of participants with any breast-feeding at 6 months (Fig. 5a) and three studies(Reference Ortiz, McGilligan and Kelly49–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) were pooled for proportion of participants with any breast-feeding at 12 months (Fig. 5b). The proportion of participants’ breast-feeding at 6 months ranged from 58 to 90 % in the six included studies. The pooled proportion for breast-feeding at 6 months from the meta-analysis of six single-arm studies(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) was 0·76 (95 % CI 0·66, 0·84, I 2 = 94 %, Fig. 5a), indicating that 76 % of participants in a workplace programme maintained any breast-feeding at 6 months. Across the three studies(Reference Ortiz, McGilligan and Kelly49–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) reporting any breast-feeding at 12 months, the proportion was more variable ranging from 24 to 69 % of participants. The pooled proportion for breast-feeding at 12 months from the meta-analysis for three single-arm(Reference Ortiz, McGilligan and Kelly49–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) studies was 0·41 (95 % CI 0·22, 0·62, I 2 = 97 %, Fig. 5b), indicating that 41 % of participants in a workplace programme maintained any breast-feeding at 12 months. The high heterogeneity in studies reporting the 6-month outcome (I 2 = 94 %) and studies reporting the 12-month outcome (I 2 = 97 %) potentially resulted from the observational study designs, diversity in the samples (which were all American women but from different states and backgrounds), the diversity of programme components and different ways of measuring the outcomes.

Fig. 5 (a) Forest plot of breast-feeding proportion of participants in a workplace programme: any breast-feeding at 6 months for six studies (1571 subjects). (b) Forest plot of breast-feeding proportion of participants in a workplace programme: any breast-feeding at 12 months for three studies (998 subjects)

Three studies(Reference Tsai39,Reference Sahip and Turan43,Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) reporting any breast-feeding outcome were not able to be included in the meta-analysis, and these are reported narratively. The first of these studies was a cross-sectional study by Tsai(Reference Tsai39) and participants were categorised by the rate of breast-feeding: no more than 1 month, 1–6 months and more than 6 months, which made the outcomes unsuitable to pool with other studies. For all employees included in the current study, using breast milk expressing breaks significantly increased both proportions of mothers who maintained breast-feeding for 1–6 months (44·0 %) and for more than 6 months (49·4 %) (P < 0·0001)(Reference Tsai39).

The remaining two studies(Reference Sahip and Turan43,Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) that were excluded from meta-analysis were non-randomised controlled studies. Yimyam et al. (Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) reported the rate of breast-feeding at 6 months in a Thai workplace was significantly higher among mothers participating in a programme (containing education and support by health professionals, breast-feeding support campaign and a designated breast-feeding corner in the workplace) compared with non-participants (χ 2 = 4·52, P = 0·033). Similarly, Sahip(Reference Sahip and Turan43) reported the rate of breast-feeding at 9 months in a Turkish workplace six-session breast-feeding education programme targeted at expectant fathers was significantly higher among partners of employees participating in the programme compared with those of non-participants (OR = 2·64, 95 % CI 1·36, 5·09, P < 0·01).

Secondary outcomes

Three studies(Reference Cohen and Mrtek48,Reference Ortiz, McGilligan and Kelly49,Reference Cohen, Mrtek and Mrtek53) reported secondary outcomes including postnatal leave, infant illness and infant-related maternal absenteeism. The length of postnatal leave, as a secondary outcome, was extracted to assess how well a workplace programme supported employees to deal with work–family conflicts and whether employers also benefited from such programmes in case mothers returned to work earlier. These are summarised narratively. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen and Mrtek48) reported on a three-phase lactation programme (prenatal, perinatal and return to work) which showed a longer maternity leave period of 3·4 months among participants compared with 2·3 months among non-participants. Ortiz et al. (Reference Ortiz, McGilligan and Kelly49) reported mean postnatal leave of 2·8 months (sd = 1·4) for 336 mothers who successfully expressed milk at work (with no comparator group).

A retrospective cohort study by Cohen et al. investigated how a workplace breast-feeding support programme improved breast-feeding practice(Reference Cohen and Mrtek48), and then how it further benefited employers in terms of infant illness incidents and infant-related maternal absenteeism(Reference Cohen, Mrtek and Mrtek53). A sample of breast-fed babies (n 59), whose mothers were participants of a workplace programme, was compared with a sample of formula-fed babies (n 42). The results showed that babies in the breast-fed group had lower incidence and severity of infant illness, and less maternal absenteeism directly related to infant illness(Reference Cohen, Mrtek and Mrtek53). To be specific, among twenty-eight babies who were not experiencing any illness during the study period, the proportion of breast-fed babies was 86 %, which was significantly higher (P < 0·005) than that of formula-fed babies (14 %). Another example was infant illness episodes causing one-day-absence. Among forty infant illness episodes causing one-day-absence, the proportion of breast-feeding mothers was 25 %, which was significantly lower (P < 0·05) than that of mothers using formula (75 %). Overall, these results suggested that employers also benefited from offering a workplace breast-feeding support programme to employees.

Qualitative results

Two mixed methods studies(Reference Sahip and Turan43,Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) and three qualitative studies(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40,Reference Johnson and Salpini41,Reference Froh and Spatz54) reported qualitative findings on workplace breast-feeding programmes. Sahip et al. reported that the programme (educating expectant fathers) enhanced the confidence of new parents to feed babies in a way they thought was right; however, some mothers reported they were stressed by their husbands’ suggestions(Reference Sahip and Turan43). Yimyam et al. (Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44) reported positive comments from breast-feeding mothers who reported feeling supported, reduced family costs and healthier infants as well as comments from management who reported feeling positive about being able to support breast-feeding employees(Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44). The results of the two qualitative studies indicated that mothers have varied experiences in combining breast-feeding and employment, and many barriers still needed to be addressed even after implementing a workplace programme, including time, space and understanding from colleagues and supervisors(Reference Johnson and Salpini41,Reference Froh and Spatz54) . One study(Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan40,Reference Cheyney, Henning and Horan52) highlighted that although employers had put effort in supporting breast-feeding, many barriers still existed for working mothers to feel comfortable to practise breast-feeding.

Discussion

This review set out to critically analyse the literature on workplace interventions to support breast-feeding and to assess their effectiveness in improving breast-feeding outcomes. There were no randomised controlled trials and study designs were limited to non-randomised controlled trials, cross-sectional studies and a retrospective cohort study. The results from the set of meta-analyses suggest that workplace programmes are effective in supporting breast-feeding among employed mothers, and partners of employed fathers, in terms of breast-feeding duration, proportions of exclusive breast-feeding and any breast-feeding. These results build on previous reviews which concluded that the workplace is an important and potential place to situate supportive breast-feeding programmes to improve breast-feeding practice(Reference Dinour and Szaro32,Reference Hirani and Karmaliani55) . To the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the first time that meta-analysis has been used to investigate the effectiveness of workplace interventions for supporting breast-feeding. The positive results are encouraging, although cautiously so. High heterogeneity in the meta-analyses of single-arm studies, the small number of studies included in the meta-analyses and overall low-quality design of the included studies means that the results identify promising interventions but definitive recommendations for workplace programmes cannot be made.

The meta-analysis results, across a range of measures, highlight the potential for improving breast-feeding outcomes for employees. In terms of the rate of any breast-feeding for the single-arm studies included in the meta-analysis, all delivered in the USA, the pooled effect size suggests 76 % of participants in workplace programmes (n 6 studies) were breast-feeding at 6 months. The individual studies reported proportions ranging from 58 to 88 %, with five of the studies indicating higher proportions (between 69 and 88 % of mothers) that are of public health significance when compared with the general prevalence (55 %) in that country. These comprehensive programmes(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46–Reference Whaley, Meehan and Lange51) shared common programme components, in that they all included the provision of breast milk expression facilities and incorporated a group component, in the form of either group education or support group. Four of these six studies(Reference Balkam, Cadwell and Fein46,Reference Cohen and Mrtek48–Reference Spatz, Kim and Froh50) also provided employees with a dedicated breast-feeding room.

Furthermore, while the three non-randomised controlled studies suggested that those participating in workplace programmes were more likely to exclusively breast-feed, the pooled result should be interpreted with caution given each of the programme components and contexts was quite different despite low statistical heterogeneity. The programme delivered in Turkey was a comprehensive education programme for expectant fathers, in which there were six sessions, lasting 3–4 h per session(Reference Sahip and Turan43). The programme delivered in Thailand was a multi-component breast-feeding support programme offering working mothers group education, individual consultations, breast milk expression facilities and breast-feeding breaks(Reference Yimyam and Hanpa44). Another study in Turkey investigated the improvement of laws regulating maternity law, including leaving work 3 h earlier in the first 6 months after delivery and 1 1/2 h earlier in the following 3 months, withdrawing night shifts from the time of the pregnancy to 24 months after delivery, and provision of 16 weeks of paid leave and optional unpaid leave of 24 months(Reference Eren, Kural and Yetim42).

In addition to those programmes reported in the included studies for this review, there were also several innovative programmes that were retrieved in the search but were excluded for not reporting outcomes of interest. These may be useful for employers looking for innovative ideas for workplace breast-feeding programmes, which could be tested in future research. One study(Reference McIntyre, Pisaniello and Gun56) reported on the development of a comprehensive information kit to combine breast-feeding and paid employment which was distributed across Australia. A set of distribution strategies were implemented with the use of current employer networks including targeting industries with the highest proportion of females in their workforce; targeting human resource managers, Chief Executive Officers, union representatives; media promotion of the project; internet searching for target employers; newsletters/journals of some industry organisations; and curating project materials on the Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy website. Another study(Reference Magner and Phillipi57) made use of existing employee benefit systems, in which employees accumulated points for conducting healthy behaviours, which were then exchanged for benefits, such as paid leave. In this way, healthy behaviours were encouraged. As an extension, the study reported adding breast-feeding as a new option which led to 152 employees logging breast-feeding activities, with an average duration of 12 weeks per employee. A further, recently described large-scale programme(Reference Lennon, Bakewell and Willis58) was implemented across different companies with a focus on industries with a larger proportion of women in the workforce. Companies with an existing lactation programme were identified as mentor businesses and assigned to those without a lactation programme (mentee businesses)(Reference Lennon, Bakewell and Willis58). Mentor businesses helped mentee businesses to establish new policies or interventions for supporting employee breast-feeding. One further excluded study reported that the Nevada Health Division implemented a policy enabling employees to bring new babies to work, which was simple and low cost to employers(Reference Langdon59) and while this report did not meet the inclusion criteria for the review (as it was a single case study), it highlights outcomes which may be important to employers.

It is of value to establish evidence that employers can benefit from supporting breast-feeding among employees and to further set policies and laws in place. Only one included study reported on infant outcomes and concluded lower child-related maternal absenteeism with a workplace breast-feeding programme. This is important as employers often make decisions on workplace policies or interventions based on cost and this finding highlights another advantage of a workplace programme to support breast-feeding(Reference Bai, Wunderlich and Weinstock60). Including more of these employer-centred outcomes, such as infant health, maternal health and child-related parental leave, would be of interest in future research.

The strengths of this review are the comprehensive search strategy across both health and business databases, the inclusion of all intervention study designs, with no restriction on language or date. Independent researcher screening, data extraction and appraisal of studies provide confidence in the robustness of the methods. However, a few limitations should be noted, most significant being that eligible studies were generally low to moderate in quality, and many of the studies in the meta-analyses were single-arm studies with no comparison. In addition, the number of studies able to be included in the meta-analyses was limited. All included studies reported at least one positive outcome, raising the potential for publication bias as workplace programmes with negative effects were not identified as eligible for inclusion. Therefore, the results could potentially overestimate effectiveness. An assessment of publication bias was not possible due to varied outcomes from included studies. Finally, not all studies in the meta-analysis measured the outcomes in the same way but were treated as if they were. Measuring outcomes in different ways also resulted in the exclusion of some studies in the meta-analysis. While a meta-analysis allowed the pooling of results where the same outcomes were reported, we acknowledge that the lack of robust study designs and variability across the pooled studies (reflected in the high heterogeneity) means that there is uncertainty in these results. However, these results are still of value in establishing guidance to those wishing to develop effective programmes to promote breast-feeding in the workplace setting, and those interested in developing robust study designs to provide more certainty about effectiveness. Until more rigorous studies are conducted to better evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions, the results provide some useful evidence relating to the research question.

Conclusion

Workplace programmes play an important role in promoting breast-feeding among employed mothers and partners of employed fathers. The meta-analysis demonstrates a non-causal association between group components, provision of breast-feeding facilities and space and improved breast-feeding outcomes. Further, high-quality research on the effectiveness of these workplace interventions to improve breast-feeding practice is essential to direct human resource and public health practitioners to implement programmes that meet the needs of mothers, infants and the employers.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to Dr Jaimon Kelly for assisting with EndNote and RevMan, Associate Professor Lotti Tajouri, Gabriela Machado Negrao and Gahee Lee for translating articles in Spanish, French, Portuguese and Korean into English. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: P.P., X.T., J.B., D.H., K.M.S and D.R. contributed to the design of the study; X.T. conducted the literature search; X.T., P.P., D.R., J.B., K.M.S. and L.v.H. screened study eligibility; X.T., L.v.H., K.M.S. and D.R. appraised included studies; X.T. and E.R. conducted the meta-analyses; X.T. and D.R. interpreted the results; X.T. drafted the manuscript; all authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final submission. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020004012