In the introduction to Major John Robertson’s memoir of his service with the Imperial Camel Corps, With the Cameliers in Palestine (1938), Sir Harry Chauvel, the wartime commander of the Desert Mounted Corps, ruminated on the importance of Robertson’s memoir. ‘In New Zealand as in Australia’, he explained, ‘it is only natural that more interest has been shown in the Western theatre of the Great War than in the Eastern theatres as the great bulk of their soldiers served in the former. The Palestine campaign’, he continued, ‘is consequently little known in these countries’.Footnote 1 Curiously, he thought, the campaign was better known in the United States, especially amongst American cavalrymen who likened the EEF’s northwards drive to Aleppo to Stonewall Jackson’s campaign in the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War, than it was in Britain and the Dominions. The memory of the campaign was alive and well, though, Chauvel was happy to report, amongst the men of the 14th and 15th Australian Light Horse Regiments, who had adopted the motto Nomina Desertis Inscripsimus, ‘In the Desert we have written our names’.Footnote 2 Chauvel had first pointed out the relative obscurity of the war in Sinai and Palestine seventeen years earlier, when he praised R. M. P. Preston’s regimental history, The Desert Mounted Corps (1921), for bringing attention to a campaign ‘but little known to the general public’.Footnote 3 He did so again in the foreword to Ion L. Idriess’s The Desert Column (1932).Footnote 4 Yet little, it seemed to him on the eve of the Second World War, had changed.

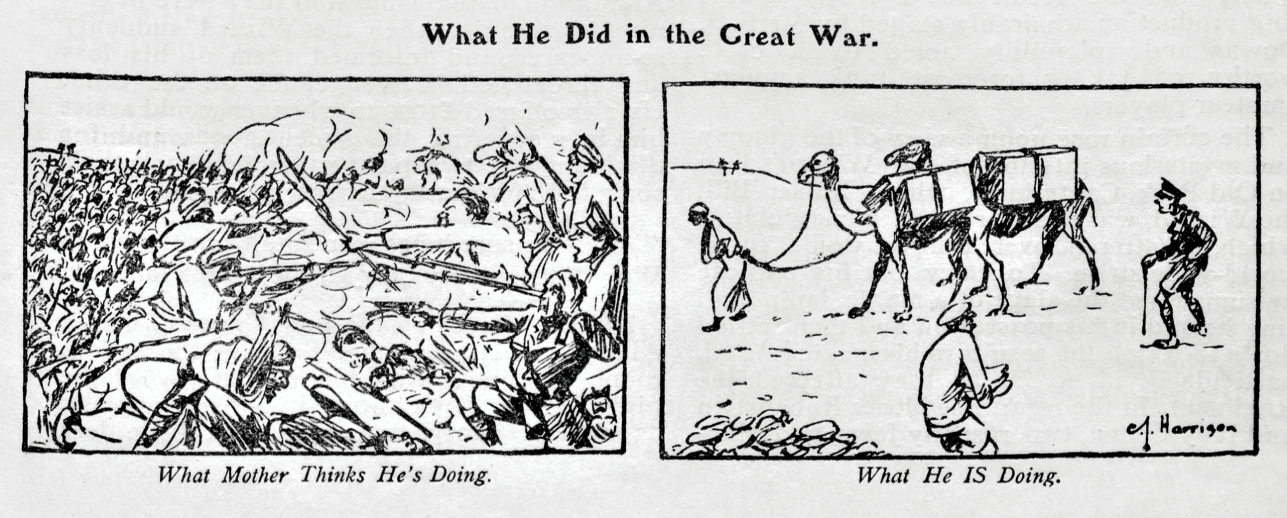

Chauvel wasn’t exaggerating. Although the campaign in Sinai and Palestine and elsewhere had long been overshadowed by the war on the Western Front, much to the dismay of soldiers during the conflict, as we have seen in previous chapters, the situation had worsened in the interwar period. Twenty years after the start of the war, the ‘popular definition of culturally legitimate war experience’ in Britain, as Janet Watson has argued, ‘had narrowed to that of the soldier in the trenches: young junior officers or possibly men in the ranks, preferably serving in France or Belgium, and almost certainly disillusioned’.Footnote 5 The very worst fear of the men who had fought outside the Western Front – of men like ALA, whose reinterpretation of the wartime poster ‘Daddy, what did You do in the Great War?’ opened Chapter 3 – had been realised. To paraphrase Watson, it seemed as though they had fought a different war altogether – a war that had not been waged in the trenches of France or Flanders and was undeserving of attention, inclusion, admiration, or even sympathy.Footnote 6

How were soldiers going to fight back? The answer, as Chauvel’s comments implied, was to put pen to paper and to write for the public. By bearing witness to their war in memoirs and battalion and regimental histories, ex-servicemen would set the record straight, as only those who had experienced the privations of soldiering in the Jordan Valley or the Struma Valley, had seen the army roads running from Salonika to Summerhill Camp, or had watched jubilant Arabs and Jews welcome them in Baghdad and Jerusalem could do. In this way, ex-servicemen were ‘agents of memory’, as Jay Winter and Antoine Prost have labelled them, and their memoirs were ‘political weapons’.Footnote 7 The goal was to persuade and ‘to shape the memory of others’, as Peter Burke argued of memoir writing some time ago.Footnote 8 The reading public had to know why they had fought, suffered, and sacrificed so far from the Western Front, especially at a time when a stable and functional government was being put together and rebellions were being put down viciously in Mesopotamia/Iraq, ethnic and religious violence were tearing apart Mandate Palestine, and when, in public, politicians such as Bonar Law, during the Conservative Party’s campaign in the general election in 1922, had condemned the campaign in Mesopotamia, telling the press ‘I wish we had never gone there’.Footnote 9

First, this chapter will explore the main reason ex-servicemen gave for writing their memoirs, which was the belief that they were still forgotten in the interwar period and that their memoirs were meant to correct that oversight. And if the other wars were still forgotten, as ex-servicemen argued, that means that the hardships of their wars, which we explored in Chapter 1, also were unknown. Thus, we will move from ex-servicemen feeling forgotten to ex-servicemen defending their fronts as active and ‘real’ warfare. Again, as soldiers did during the war, they often compared their campaigns to the Western Front. To add extra meaning to their campaigns, ex-servicemen also connected them to history and the past. We will then move on to how ex-servicemen constructed the memory of their campaigns. Linking back to Chapter 3, we will see how ex-servicemen returned to themes such as crusade, liberation, and the civilising mission. Yet laying the groundwork for the spread of liberal imperialism and seeing their campaigns as civilising missions were far more widespread in the post-war period. The main difference was that, during the war, there was little doubt that France and Flanders mattered more. With the benefit of hindsight, however, some soldiers questioned the supremacy of the Western Front. Last, and tied to a reassessment of the importance of the peripheral fronts and the Western Front, we will look at how ex-servicemen, particularly those who had fought in Palestine and Macedonia, claimed (once again) that they had played an instrumental part in ending the war.

Still Forgotten

Returning to Chauvel’s comments, he was by no means alone in alleging that the campaign in Sinai and Palestine, or the campaigns in Macedonia and Mesopotamia, had been forgotten, if they were ever known, by the public. As we saw in Chapter 4, British and Dominion soldiers throughout the war wrote to loved ones, periodicals, newspapers, and to other press outlets, afraid, upset, and indignant that their part in the wider war effort had been either misrepresented, giving the public the misconception that their campaigns were ‘cushy’ compared to the Western Front, or overlooked. The fear that the other wars were still forgotten continued to haunt ex-servicemen in the interwar period and was one of the main reasons, as they explained in forewords, introductions, and prefaces, for writing their memoirs.

But were ex-servicemen airing a legitimate grievance? Had they been squeezed out of interwar memory? At least for the first four or five years after the conflict, the campaign in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine was very much a part of the memory of the war throughout the British Empire. Across the empire, Lowell Thomas, an American journalist and official war correspondent to New York’s The Globe, presented his travelogue With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia. Between 1919, the year the show debuted in New York and then went to London, and 1925, the travelogue was delivered around four thousand times and total ticket sales exceeded four million. In 1923, British Instructional Films (BIF) released Armageddon, a full-length film about the campaign that combined official war films, photography, animated maps, and dramatic re-enactments. Three wartime events that resulted in the awarding of a Victoria Cross were shown, including the rescue of two English soldiers from Ottoman shellfire and the storming of an Ottoman machine-gun position by a lone Scottish corporal. The surrender of Jerusalem along the Jaffa Road was dramatised and starred F. G. Hurcomb, the British soldier to whom the mayor of Jerusalem surrendered the city. Elements of the scene were reconstructed with the benefit of Hurcomb’s own collection of wartime souvenirs. In addition to scenes of personal bravery, the film covered the extension of the water pipeline and railway from Egypt into Sinai, the cavalry charge at Huj, and parts of Allenby’s entry into Jerusalem. Importantly, too, Armageddon portrayed the Ottoman Empire’s involvement in the war as part of a centuries-long expansionist policy of the House of Hohenzollern, dating back to the fifteenth century. The film was an immediate commercial success, drawing an opening week audience of nearly 27,000. After a two-week season at the New Tivoli Theatre in London, the ‘British Film for the British People’, as New Era Films, the chief distributor for Armageddon, called it, its popularity led to a second season at the Pavilion, Marble Arch.

Critical reviews were overwhelmingly positive, too. The Star called it ‘perhaps the most remarkable film ever made’, while Bioscope, a trade journal, praised the average British ‘Tommy’ as the film’s star. The film’s use of ex-servicemen to dramatise events had lent Armageddon a ‘convincing realism which one generally associates with animals or little children’.Footnote 10 Armageddon’s realism was enhanced by a live, in-person presentation at the film’s premier by Hurcomb and a soldier who had swum the Jordan River, Lieutenant G. E. Jones of the London Regiment. The presence of Hurcomb and Jones blurred the line between Armageddon as educational film and interactive media. Moderated by Sir George Aston, a member of the War Cabinet Secretariat and a military historian, Hurcomb and Jones fielded questions from the crowd following the film’s exhibition. The Daily Graphic, impressed both by the film and by the presence of the two ex-servicemen, suggested that people ‘will go to this picture as on a pilgrimage’.Footnote 11 Crucially, the film’s focus on British and Dominion heroics and on the Allies’ ultimate victory over the Central Powers, as well as the commercial and critical popularity of Armageddon, lends more weight to historian Michael Paris’s argument that interwar society considered the First World War as ‘another bloody but glorious page in the history of the British Empire’. As Armageddon’s popularity demonstrates, that ‘page’, at least in the early 1920s, included the war in the Middle East.Footnote 12 Juvenile and fictional literature, such as With Allenby in Palestine: A Story of the Latest Crusade and On the Road to Baghdad, both written by F. S. Brereton, a popular writer for Blackie’s Publisher who served as a lieutenant colonel with the RAMC, were also popular throughout the empire.Footnote 13 Watercolour paintings of the war in Mesopotamia, particularly the actions of the Royal Flying Corps, later the Royal Air Force, at Kut, featured in the Royal Academy’s exhibition in 1919.Footnote 14

In Australia, the campaign in Sinai and Palestine was also well known in the interwar period and beyond. George Lambert, an official war artist in the Middle East in 1917 and 1918, had his painting, The Charge of the Light Horse at Beersheba, 1917, exhibited at the Australian War Memorial Museum in 1920. The Museum also loaned official war photographs of Palestine to local war exhibitions. An entire court in the Australian War Memorial Museum, ‘Palestine Court’, was devoted to the war in Sinai and Palestine.Footnote 15 Towns in Australia, such as Mena Creek, paid tribute to the Australian encampment at the foot of the pyramids. Soldier settlements were named after battles in the region. El Arish was established in Queensland in 1921. Three of the settlement’s streets were named after high-ranking officers who had fought in Sinai and Palestine, including Chauvel, John Royston (who had commanded the 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Brigades), and Granville Ryrie (who had commanded the 2nd Light Horse Brigade). When Australian film-makers looked to boost recruitment in the Second World War, they turned to First World War Palestine. In December 1940, Forty Thousand Horsemen, shot between 1938 and 1939 and directed by Charles Chauvel, the nephew of Harry Chauvel, was released in Australia and subsequently in the United Kingdom and the United States. The film follows three Australian Light Horsemen, one of whom is tangled in a love affair with a French woman working at a vineyard in Palestine, up to the Battle of Beersheba in October 1917.

Despite the clear attention paid to both the capture of Jerusalem and the broader campaign, British and Dominion soldiers who had fought in Sinai and Palestine, as well as those in Macedonia and Mesopotamia, alleged in their memoirs that their part in the war effort had been forgotten. Macedonia was a ‘forgotten expedition’ which had been fought by a ‘Forgotten Army’.Footnote 16 Mesopotamia had ‘been neglected by military students and historians alike’.Footnote 17 The campaign was ‘so distant from Europe that even the tragedy of Kut and the slaughter which failed to save our troops and prestige were felt chiefly in retrospect’, wrote another. The public knew something of the surrender of Kut al-Amara and Baghdad’s capture, but ‘of the hard fighting which followed, which made Baghdad secure, nothing has been made known, or next to nothing’.Footnote 18 Another ex-serviceman, who was certain ‘that the tragedies and hardships of our troops on the lesser war fronts passed almost unnoticed’, guessed ‘that there are many people who have never heard of the Siege of Kut, much less the bloody battle of Ctesiphon and the subsequent rearguard action we fought back on to Kut-el-Amara’.Footnote 19 ‘Little did the British public, more immediately affected by the greater wars’, wrote Lieutenant-Colonel J. E. Tennant of the Royal Flying Corps, who had served in Mesopotamia, ‘realise how forgotten British officers were dying in nameless fights, or rotting with fever in distant outposts, “unknown, uncared-for, and unsung”’.Footnote 20 ‘As a rule, only the dramatic portion of the work has been chronicled in daily newspapers’, complained Major Kent Hughes in Modern Crusaders (1918), referring to Jerusalem’s capture, ‘and very little information ever appeared of the conditions under which the troops lived, whether on the desert of Sinai or on the fields of Palestine’.Footnote 21 ‘LITTLE has been said, and less written of the campaigns in Egypt and Palestine’, wrote Antony Bluett of the Camel Transport Corps in With Our Army in Palestine (1919). ‘The Great Crusade began with the taking of Jerusalem and ended when the Turks finally surrendered in the autumn of 1918’, he wrote of the public’s perception of the campaign. ‘This view, entirely erroneous though it be, is not unreasonable’, he continued, ‘for a thick veil shrouded the doings of the army in Egypt in the early days, and the people at home saw only the splendid results of two years’ arduous preparation and self-sacrifice’.Footnote 22 Even Allenby, the subject of so much celebrity during and immediately after the war, joked to ex-servicemen at the regimental dinner for the Dorset Yeomanry in February 1933 that he ‘was dining in London a few nights ago when a lady next to me said, “Have you ever been to Jerusalem?” That tore my reputation to shreds.’Footnote 23

Memoirs were meant to fill the gap and to present the soldier’s truth to the public. Bluett’s memoir was to give the public an ‘idea of the work and play and, occasionally, the sufferings of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force’.Footnote 24 F. H. Cooper’s Khaki Crusaders (1919) was meant to ‘interest rather than instruct the people at home’.Footnote 25 Another ex-serviceman, who had fought with the 20th Machine Gun Squadron in Palestine, wrote to allow ‘friends and relations to obtain some idea of their experiences whilst they were serving with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force’.Footnote 26 Captain John More’s With Allenby’s Crusaders (1923) was written not only for his fellow ex-servicemen, for whom his memoir would be ‘merely a reminiscence of the Palestine Campaign’, but also ‘to give an honest account of life in the Palestine Campaign’ for a public who had neither been there, he thought, nor read about the campaign’s hardships.Footnote 27 Sir George Milne, the wartime general officer commanding in chief of the BSF, praised A. J. Mann’s The Salonika Front (1920) for helping the public ‘pierce the supposed veil of mystery with which popular fancy has enshrouded these forces, and to form his own opinion as to their weight in the scale of the military operations which eventually led to the debacle of the Central Powers and their allies’.Footnote 28 Alexander Douglas Thorburn’s Amateur Gunners (1934), his memoir of his time in France, Macedonia, and Palestine, was written ‘to present an entirely truthful picture of a varied experience of the Great War’.Footnote 29 Lieutenant V. J. Seligman of the 60th (London) Division, in the first of his two memoirs, Macedonian Musings (1918), had written because ‘France is so near home, and abler pens than mine have done the work. But of the Salonica campaign those at home know next to nothing. If I have done a little to bring before my readers a picture of life in the Salonica Army, its hardships and difficulties, its interests and pleasures’, he explained, ‘I shall not have laboured in vain’.Footnote 30 Major E. W. C. Sandes of the 6th (Poona) Division hoped that his recollection In Kut and Captivity (1919), which detailed the deplorable conditions in which the POWs of Kut al-Amara saw out the remainder of the war, would serve as a testament to the ‘British soldiers and their Indian comrades who succumbed during captivity’ and ‘died for their country’. ‘May they not be forgotten by the sons of the new and glorious British Empire created by the Great War!’, he closed his memoir.Footnote 31 ‘So far as I can discover’, W. J. Blackledge pointed out in The Legion of Marching Madmen (1936), ‘the Mesopotamian Campaign has been recorded only by militarists, historians who never write anything “indiscreet or contrary to public policy,” and political deceivers’. His memoir, instead, was ‘the untold story – an account of what one rather young Tommy saw from the fighting line’.Footnote 32

By the mid-1920s, nearly a decade before Watson has suggested that the Western Front became the only ‘culturally legitimate war experience’, ex-servicemen were already concerned that they had been shut out of public memory. ‘So much has been written concerning the Great War’, wrote Robert H. Goodsall, formerly a lieutenant in the RFA, in Palestine Memories (1925), ‘that some justification would seem necessary for the present work’. His ‘excuse’ for writing, given how inundated the public was with accounts of the war on the Western Front, was the ‘hope that these pages will mirror a little of the life, duties, and pleasures which fell to the lot of those who served in Palestine’ and to ‘stir the memory of those who were “out East” in 1917 and 1918’.Footnote 33

Fatigue with the disillusioned, hyperrealist accounts of the war by the end of the 1930s presented an opportunity that ex-servicemen hoped to seize. In Henry C. Day’s Macedonian Memories (1930), General Milne wrote that Day’s memoir came at an opportune time. ‘After the recent flood of somewhat unpleasant war literature, mostly from the “other side of the line”’, he explained, ‘the general public will no doubt turn with relief to a book such as this, which looks upon war in the healthy British way’. Milne was ‘very glad to have the opportunity of welcoming a book of such sturdy character’, and one, he was optimistic, ‘which will help towards the long delayed recognition, by the general public, of the work done by the British rank and file in Macedonia’.Footnote 34

If the public weren’t listening, as ex-servicemen feared they weren’t, some literary critics and reviewers were. In April 1923, Orlando Cyprian Williams, a clerk of committees in the House of Commons and literary critic for The Times Literary Supplement, thought it was ‘impossible not to be struck by the difference of tone in war diaries’ when comparing More’s With Allenby’s Crusaders to memoirs of the Western Front. Williams was no friend of the downcast and heavy-hearted types of memoirs, such as C. E. Montague’s Disenchantment (1922) and H. M. Tomlinson’s anti-war Waiting for Daylight (1922) that had, he lamented, become all too common in the early part of the decade. ‘In spite of all the elaborate apparatus for recuperation behind the front in France and the nearness of home’, he wrote, ‘the unabating horror of soul-destroying monotony of war on that front affected even the most cheerful of men’. By contrast, More’s memoir of Palestine, and other memoirs of other fronts he had read, ‘where back-of-the-line organization was, in early stages, far more primitive, the spirit of sport and adventure was never extinguished. This was peculiarly true of the great campaign which led from the Suez Canal to the conquest of all Syria.’ Williams wasn’t naïve, though. He was well aware of the difficulties that had troubled British and Dominion soldiers in Sinai and Palestine, including ‘the weary desert, now scorching, now freezing, the septic sores, the fleas, the flies, the frequent thirst, the first failure at Gaza that cost so many lives’.Footnote 35 Seven years later, Cyril Falls, the well-known Irish military historian and ex-serviceman, felt the same. In his annotated bibliography of war books, Falls lambasted disillusioned memoirs as ‘propaganda founded upon a distortion of the truth’, for appealing ‘to the emotions rather than to reason’, for pandering to ‘a lust for horror, brutality, and filth’, for belittling the British Empire’s war effort, and for pretending that ‘no good came out of the War’. Some of the books that caught Falls’s eye as better representations of the war came from outside the Western Front, and included Gerald B. Hurst’s With Manchesters in the East (1918), Adams’ The Modern Crusaders (1920), Vivian Gilbert’s The Romance of the Last Crusade: With Allenby to Jerusalem (1923), More’s With Allenby’s Crusaders, and Edward Cooke’s With the Guns West and East (1924).

Still Misrepresented

Williams and Falls, writing at opposite ends of the decade following the war, were but two voices championing the memoirs of those who had fought outside the Western Front. They were not enough to convince ex-servicemen, if ex-servicemen knew of their reviews and support at all, that the public had taken notice of their campaigns. Fear that the war outside the Western Front had been badly misrepresented – that it was bloodless and a ‘picnic’ from the real war on the Western Front – first arose during the conflict, as we saw in Chapters 1 and 4. Soldiers wrote letters home to popular periodicals, journals, and newspapers to make clear that they had done their bit, had suffered, and, in some cases, had a hand in winning the war. That men had fought, been wounded, and/or died during the war was paramount in the interwar period. For British society, the war’s ‘greatness’, as Dan Todman has explained, went hand in hand with a ‘morbid revelling in mass fatality’ and an ‘amazement with vast catastrophe’.Footnote 36 Scale and numbers mattered, and the campaigns in Macedonia or the Middle East, by most measures, fell far behind the Western Front. Northern Irishmen who had fought at the Somme, for example, had bled for Britain and were ‘valiant unionist heroes’, as historian Jane G. V. McGaughey has shown of Northern Irish attitudes to its ex-servicemen. Those who had fought away from the Western Front, like the 10th (Irish) Division, which spent considerable time in Macedonia and Palestine, were ‘omitted from this pantheon of warrior masculinities’ and often discriminated against in the interwar period.Footnote 37

The problem was obvious to Major C. S. Jarvis of the 60th (London) Division. ‘We imagine always’, he wrote in Through Crusader Lands (1939), ‘that most of our soldiers were killed in France or Flanders, and forget that thousands lost their lives fighting their way through the mountains of Palestine to free Jerusalem from the Turk’.Footnote 38 On the frontispiece to the Legion of Marching Madmen, Blackledge, much like ‘ALA’ had done in his fictional scene for the Chronicles of the White Horse, appropriated Saville Lumley’s Parliamentary Recruiting Committee poster:

The co-authors of the history of the 2nd Essex Battery, RFA, titled Romford to Beirut: Via France, Egypt and Jericho, rejected any suggestion that soldiers in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine had it easier than their comrades on the Western Front. ‘There was certainly cause for righteous indignation among the troops in Palestine and Egypt’, they wrote,

when they continually learned from the old country that everyone regarded this hazy venture as a glorious picnic. War and hardships? Not on your life. They’re romping in the sylvan glades of the Holy Land, or lazily languishing on the line of communications somewhere east of the Canal. There was a war on, and at times as fierce in intensity as France could show.Footnote 40

Other soldiers were compelled to point out that there ‘was domesticity even in the life of soldiers on a campaign’. ‘Apollo is not forever bending his bow’, wrote Rowlands Coldicott in London Men in Palestine and How They Marched to Jerusalem, and ‘yet, when pens and cameras and returned warriors have done their best, it is difficult, so fearful are the quick sympathies of those who perforce remain behind, to convince them that we do not use cold steel daily, or kill men as a matter of course every forenoon before we have our dinner’.Footnote 41 Nonetheless, Coldicott promised ‘young and old a right good piece of battling at the end of the story’.Footnote 42

Others were convinced that the root of the problem was terminology. ‘How many people there are’, wrote C. W. Hughes in the ‘The Forgotten Army’, ‘who form their ideas of a thing by the name that is given to it. The “Salonika Campaign”, the “Salonika Army”, were unfortunate titles. They were too local, even the Macedonian Campaign was misleading’, he explained. ‘It would have been far more satisfactory and also more accurate to call it “The Balkan Campaign” and the “Balkan Army” for its activities were not confined to a single town or a single country.’Footnote 43

Although soldiers on the Western Front had fought more than they had, those outside the Western Front had campaigned. Bluett described the army’s time in Sinai as ‘days of unremitting toil. We turned our attention to road-making and with bowed backs and blistered hands shoveled [sic] up half the desert and put it down somewhere else; the other half we put into sand pits and made gun pits of them.’ (Figure 5.1)Footnote 44

Figure 5.1 ‘What He Did in the Great War’, April 1917, Chronicles of the White Horse.

‘It should be understood that Mesopotamia is largely a flat expanse of sanded waste, with many miles of barrenness between the towns and the village and the occasional date palm groves’, wrote Blackledge, ‘and at that time the country was entirely without railways, the only means of transport being the camel and the donkey’. Exacerbating the problem was the poor conduct of the Indian Government, which ‘seemed unaware of the fact that an-ever-advancing army required an increasing body of transport to bring up rations, equipment and munitions. We just muddled on from day to day, not knowing how far our successful engagements would carry us. We went on without lines of communication. We went on to our doom.’Footnote 45 ‘Considering that this Expeditionary Force of barely one division of troops had fought its way for some 240 miles over extremely difficult country’, F. S. Hudson, a bombardier with the 86th (Heavy) Battery, lectured, ‘maintaining lines of communication, providing garrisons for occupied towns and villages, considerably reduced in numbers by tropical sickness apart from the many casualties inflicted upon us by the Turks, we wonder if the armchair critics of General Townshend’s tactics really did realise the whole state of affairs, and had full and fair appreciation of the situation’.Footnote 46 Milne’s preface to Mann’s Salonika Front argued that the ‘campaign communications were the main difficulty, but like the work of the Romans of old, the roads of the British Army in Macedonia will long remain the best memorial of its presence’.Footnote 47 E. P. Stebbing, a transport officer stationed at the Field Hospital at Lake Ostrovo, wrote an entire chapter, ‘Some Description of the Country in which the Western Armies Were to Operate’, on the difficulties of campaigning in Macedonia, from miles of hillsides covered in ‘large boulders or rocky masses, varied by lengths of naked projecting rock masses of all sizes and sharpnesses’, to the poor roads on which ‘no car had ever been seen’.Footnote 48 The title of Harold Lake’s memoir, Campaigning in the Balkans, was indicative of its content. Large parts of Lake’s memoir described the difficulties facing British and Dominion soldiers in Macedonia, especially compared to those who had fought in France and Flanders. Of having to traverse the Seres Road, Lake wrote,

all that they are feeling is so plainly written on their faces. They are so far away from home and all the beloved, accustomed things. Enthusiasm and love of adventure might have carried them triumphantly through some wild brief rush in France, but in this there is no adventure. Here is no glory, no swift conflict and immediate service. This is nothing but dull, unending toil, with all the pains of thirst and weariness in a strange and friendless land.Footnote 49

Of the poor roads near the Struma River, Lake continued, ‘In Sir Douglas Haig’s report on the Somme offensive he told how hundreds of miles of railway had to be laid down in preparation for that great move. We have only fifty miles of a disastrous road and no railways at all.’

Unpublished memoirs, such as C. W. Hughes’ account of his time with the Wiltshire Regiment in Macedonia, made the same argument. ‘The campaign in the Balkans had many unique features’, wrote Hughes, ‘consider the difficulties to be overcome in this Country compared with France’. France had ‘many excellent roads and many railways’, he explained, while in Macedonia there were only three major roads and three railways; the lines of communication in Macedonia ‘served a front of 250 miles, nearly the total length of the line in France from Switzerland to the Sea’; the region’s rugged terrain, especially the ridges between Lake Doiran and Vardar made ‘these main routes almost impassable for a modern army’; Greece lacked the supplies necessary to support the Allies’ war effort; and Macedonia, which had ‘suffered terribly from recent wars and villages were nothing but heaps of stone’, lacked ‘any accommodation for troops such as was to be found in the villages of France’. ‘I have no wish to make excuses’, Hughes ended, ‘but if a fair understanding of the campaign is to be gained these difficulties must be understood’.Footnote 50

Campaigning seemed to be the one thing that all men who had fought outside the Western Front shared in common. ‘There is no doubt that it was in fronts like Mespot, Salonica, and Palestine’, wrote Second Lieutenant R. Skilbeck Smith, who had fought in Macedonia with the 1st Battalion, Leinster Regiment,

that one got one’s fill in the matter of campaigning. Whether there was fighting or not, there was always campaigning, and that of a very strenuous nature, too. One was continually on the move, and one had not the benefit of good billets or huts. Whether behind or in the line one’s home was one’s bivvy, a delightful thing for a children’s picnic, but at times wretchedly at the mercy of the weather. Nor were opportunities of real change and relaxation of very frequent occurrence. At the best you got an occasional amateur pantomime. So that men were at times liable to lapse into a mood of ennui.Footnote 51

Campaigning also meant being ravaged by tropical diseases, none more so than malaria. ‘It is not’, Lake pointed out, ‘our fault or our choice that we had so little actual fighting, and the only sort of picnic which our experiences could be said to resemble would be one in which the picnic basket had been left behind and half of the party were more or less ill all the time’.Footnote 52 Lake insisted that he was not griping to garner sympathy, since ‘Hundreds and thousands of our men have endured as much and more in that country, and for that reason only the thing is mentioned’. Their ‘suffering’ and ‘misery’, he continued,

must be set down to the account of the Salonika force as surely as the agony of the wounded is credited to the account of our troops in France. We were bitten by mosquitoes instead of being shattered by bullets, but the result was not different in the end, and one can do no more than go on suffering up to that point where Nature sends the saving gift of unconsciousness; there is that limit fixed to all that a man can endure, and it has been reached not once but very many times by those who have played their part in the war by marching up and down and across Macedonia. And there are graves in that remote, inhospitable land.Footnote 53

In Macedonia, there were ‘wide spaces’ of land ‘where every battalion which occupies the ground is certain to be decimated. You could not be more positively sure of reducing its strength if you were to put it in the most perilous part of the line in one of the big offensives in France.’ Every battalion, whether in the Struma Valley, near the Galliko River, the Vardar, or Lake Langaza, he argued, knew ‘quite well that it will be losing men day after day, week after week while it stayed there’.Footnote 54

Ex-servicemen understood, however, that campaigning was not fighting and that neither military labour nor being worn down by disease were the same as suffering in the trenches of France and Flanders. Gerald B. Hurst’s With Manchesters in the East (1918) prophesied that the backbreaking work of the Manchester Regiment in Sinai, of erecting desert outposts to fortify the peninsula, would never measure up to the Western Front. ‘It is clear that this particular phase of soldiering has in itself no place in the annals of the Great War’, he wrote. ‘Ashton is already nothing but a desert site. The tide of victorious warfare has left it high and dry. It was always high and dry.’Footnote 55 Expanding the railway from Kantara into Sinai was ‘not such a simple affair as it sounds because the sand is continually blowing on to the line and covering it up’, according to E. V. Godrich of the Worcestershire Yeomanry in Mountains of Moab (1925). The railway was ‘a wonderful piece of work’ and had not, he argued, ‘received the notice it deserves in the “Home Press”’.Footnote 56 The steady build-up of a transport system capable of delivering the tools and bodies of war from Egypt to Sinai to Palestine ‘was a colossal task’, wrote Bluett, ‘the magnitude of which was never even imagined by the people at home’.Footnote 57 People at home, he continued, who

from time to time, asked querulously, ‘What are we doing in Egypt’ should have seen Kantara in 1915, and then again towards the end of 1916. Failing that I would ask them, and also those kindly but myopic souls who said: ‘What a picnic you are having in Egypt!’ to journey a while with us through Kantara and across the desert of Northern Sinai. For the former there will be a convincing answer to their query; the latter will have an opportunity of revising their notions as to what really constitutes a picnic.Footnote 58

Although there was ‘none of the pomp and circumstance of war about their work’, he admitted, ‘no great concentration of men and horses and guns, no barrage nor heavy gunfire for days in preparation for an attack, no aircraft’, alluding to the industrialised warfare on the Western Front, there was ‘nothing but a few thousand men in their shirt sleeves; and it was out of that sweat and blood that the way was made clear for them that followed’.Footnote 59 The ‘nation should know what manner of task that is which its soldiers were performing’, wrote Lake of the army’s work on the Seres Road, ‘lest there be a tendency to judge without knowledge and to condemn without the evidence for the defence’.Footnote 60 Over a decade after the war had ended, Smith was still agitated when recalling the suggestion that the soldiers in Macedonia had not done their bit, even though ‘the actual campaigning was, as the soldiers say, “hard graft”; sometimes strenuous’. ‘There was nothing that annoyed the soldier on service more’, he ended, ‘than the impression that those at home considered him to be on a “cushy” front, or garrisoning the town and having a good time generally’.Footnote 61

Lake took particular issue with the plight of the diseased, who seemed invisible, he bemoaned, to the public. ‘There is a great tendency’, he wrote,

to regard the wounded man as being on a far higher plane than the man who merely contracted sickness in the service of his country. The wounded man is given gold stripes to wear. If he is an officer he is presented with a large sum of money as a wound gratuity – but there is nothing for the man who has merely fallen ill. He may be one of those who came away from Gallipoli with their constitutions shattered beyond hope of repair by dysentery; he may be tortured and twisted and crippled with rheumatism from the trenches in France; he may be so poisoned by malaria in Mesopotamia or Macedonia, that the trouble will remain with him while life lasts, but in any event there is nothing for him. He has no gold stripes or gratuities, nor is it likely that his pension will reflect what he endured. In hospitals, in convalescent camps, and even at home in England, he is given to understand that he is a bit of a failure – a ‘wash-out’ in the slang of the day – and not to be compared with some lucky youngster who has had a finger shot off or a tibia fractured.Footnote 62

Lake’s main point was unmistakable. To the public, machine-gun fire and artillery shrapnel were obvious symbols of the modern, industrialised, and technological war that had been waged on the Western Front, not the vector-borne illnesses and bacterial water of campaigning in the Middle East or Macedonia.

Palestine: A Crusade?

During the war, The Gnome, the newspaper of the Middle East Brigade, Royal Flying Corps, tried to fathom why some soldiers were hung up on the region’s past. What purpose, the soldier author of ‘Gaza and the Crusades’ asked, did the past serve in the present? ‘The gift of historical imagination’, he argued, ‘is one of the rarest and most delicate ever vouch-safed to mortals, for it gives one the power to enter into the thoughts and feelings of men of other ages and of other countries’. Thinking of Gaza and wondering why so many armies, including the crusaders, had fought over the city, he concluded that ‘doubtless it may be that there is some purpose in all this turmoil of history’.Footnote 63 Past history had lent meaning to the present. Gaza mattered because it had always mattered, from the crusades of the Middle Ages to the present war.

But that soldier writing in the Gnome was unusually thoughtful. As we saw in Chapter 3, few soldiers in Palestine, with the exception of some Salvationists, romantics, and the odd author in a soldier newspaper, considered the campaign in Palestine as either part of the fulfilment of Zionism or a holy war between Islam and Christianity. After the war, however, references to the crusades were everywhere. Memoirs often used crusade in the title, including The Modern Crusaders, The Romance of the Last Crusade, Through Crusader Lands, Temporary Crusaders, Khaki Crusaders, and Crusader’s Coast. What had changed? John More, formerly of the 1/6th Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers, whose own memoir was titled With Allenby’s Crusaders, offered an explanation. Time and hindsight, he argued, had allowed ex-servicemen to make comparisons they never would have made during the war. ‘It was hard to realise at the time’, More closed his memoir, ‘that many outlandish places we passed through or lived in were so steeped in Biblical or historical interests. There was no time to think about such things’, he explained, ‘and it is only by reading the history of Palestine that one comes to grasp that one has been among the scenes of great conflicts, tragedies and events with which the Holy Land has ever been associated’.Footnote 64 Soldiers during the war were well aware that they were in historic lands, as we saw in Chapter 2. But thinking of themselves as modern-day crusaders or twentieth-century knights? For most, More wrote, that had to wait. Soldiers needed time to reflect. More’s reasoning is backed up by the unpublished memoir of L. J. Matthews, formerly of the 5th Siege Company, Royal Monmouth Royal Engineers. ‘While we were stationary’, he wrote of his time in Palestine,

we did talk at times about the nations which had crossed these desert lands in the centuries gone by. We thought and talked about the Israelites who, under Moses had wandered for 40 years in the Sinai Desert; we talked too of the Crusades in the Early Middle Ages; not that we felt much like Crusaders – all we wanted to do was to get on with the job – knock Johnny for six – if we could and then return home to England and back to peace-time activity.Footnote 65

With the passage of time, the benefit of hindsight, and a chance to delve into the region’s past, many ex-servicemen turned to the crusades. It was an obvious choice. Medievalism had taken society by storm in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Chivalry, honour, and knightly conduct were once again revered, and not only by the upper echelon of society, as all classes reacted to the dual strains of industrialisation and urbanisation by looking backwards.Footnote 66 Families took an interest in finding crusading ancestors and fitting them into their family tree.Footnote 67 Children’s literature and fiction were set during the crusades.Footnote 68 Artists and composers looked to them for inspiration.Footnote 69 If not out of some misguided sense of religious zealotry, then why did average, working-class British and Dominion ex-servicemen, some of whom, to be fair, were middle class and well educated (perhaps a disproportionately high number in the EEF, which was composed mainly of Territorials), refer to their wartime experience in the context of the crusades?

There are three answers, some of which overlapped in ex-servicemen’s memoirs. The first uses an alternate understanding of the crusades that did not rely upon its medieval and inherently religious connotation. The meaning of the crusades changed considerably in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, reflecting new attitudes towards nationalism, imperialism, and European history. While ‘pseudocrusading language’, according to the late crusades historian Jonathan Riley-Smith, had taken hold in Britain, France, and Germany, it had ‘no correspondence to the old reality, but borrowed its rhetoric and imagery to describe ventures – particularly imperialist ones – that had nothing at all to do with the Crusades’.Footnote 70 In France, under the Bourbon Restoration, the July Monarchy, and after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 to 1871, the crusades were reimagined as a part of French national history and as an event that had united Europe. As it related to France’s mission civilisatrice, its civilising mission, the crusades were linked to the occupation of North Africa and used to defend French influence in Ottoman Syria and Mount Lebanon.Footnote 71 The crusades also became ‘embedded in the concept of German imperialism’.Footnote 72 In Britain, the crusades were ‘de-Catholicized’, as Adam Knobler has argued, and made a part of Christian militarism or muscular Christianity. Crusading heroes such as Richard the Lionhearted epitomised model for nineteenth-century Englishness. As in France and Germany, crusading and imperialism became almost interchangeable. Soldiers in the Crimean War and the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars, defenders against the Indian Mutiny, and imperial heroes such as Sir Henry Havelock and General Charles Gordon were all written about in pseudocrusading language.Footnote 73 Protestant Christian missions, such as the Christian Missionary Society, envisioned their proselytising work as akin to that of the crusaders.Footnote 74 In short, crusading in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was almost always divorced from the reality of the medieval crusades. More often, it elided with imperialism, so that crusading and the imperial project became one and the same. It was also reworked in nineteenth-century histories and children’s textbooks to read as the arrival of western governance and institutions in the Middle East and the defence of political or moral right and justice against tyranny.

‘Will our campaign be passed down to history as “The Last Crusade”?’, asked Major Henry Osmond Lock, formerly of the Dorsetshire Regiment. ‘Presumably not. Throughout the campaign there was little or no religious animosity except that the Moslem Turk extended no quarter to the Hindoo. To speak of this as a campaign of The Cross against The Crescent is untrue’, he concluded.Footnote 75 Unsurprisingly, then, the capture of Jerusalem was almost exclusively remembered as a liberation. Coldicott of the 60th (London) Division wrote: ‘That Jerusalem was to be visited by us in the guise of liberators was an idea now handed freely about from man to man.’Footnote 76 To Captain John More, ‘Jerusalem was delivered out of the hands of the terrible Turk after four centuries of misrule’.Footnote 77 The unpublished memoir of J. C. F. Hankinson of the London Scottish recalled that he and his comrades had ‘helped to free Jerusalem from Turkish occupation’.Footnote 78 Many soldiers were convinced that Ottoman rule had retarded the economic development of Palestine, mirroring the wartime anti-Ottoman propaganda of Wellington House. Captain Alban Bacon of the Hampshire Regiment in The Wanderings of a Territorial Warrior looked back to the disparity between the Rothschild colonies of Akir and Katrah and nearby Arab villages as proof of Ottoman oppression. With the helpful hand of European finance and direction, Akir and Katrah were model colonies filled with ‘prosperous-looking houses and moderately well-clad inhabitants’. In comparison, Arab villages ‘seemed sparse and apathetic’. ‘Turkish rule’, Bacon concluded in his post-war memoir, ‘evidently acted like a blight. Some of the country had been cultivated, but there were scant signs of enterprise.’Footnote 79 In Major A. H. Wilkie’s Official War History of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, it was ‘Turkish oppression and maladministration’ that had ‘been responsible for the degeneration of the once fertile Valley’, referring to Jericho and the area around the Jordan River. The ‘Apple of Sodom’ had replaced ‘the grapes and figs which once grew in profusion there’.Footnote 80

Just as Prussian militarism had trapped helpless Belgians and French under the boots of the German Army, ex-servicemen pointed to a number of peoples who had been in desperate need of deliverance from the Ottoman Turks. In addition to freeing the Holy Land ‘from the ambitions of a modern Herod’, Bluett of the Camel Transport Corps suggested that Britain’s victories over the Ottomans had kept Egypt politically free and independent. His fantasy of Egyptian sovereignty completely ignored the fact that Egypt had been under British military occupation since 1882. Nonetheless, he was certain that the Ottomans had designs on Egypt and would turn it into an economic backwater like Palestine. In a way, then, Bluett’s understanding of the campaign in Egypt and Palestine was like a preventive war of self-defence.Footnote 81 Donald Maxwell’s chance meeting with an Armenian, possibly a political exile, on a train from Taranto to Egypt convinced him that to defeat the Ottomans was to free the Armenians. Lodged together in the same carriage, the Armenian traveller lectured Maxwell on Armenia’s Christian past, its role in supporting medieval European crusaders, and convinced him that the Ottoman Empire had brought nothing to civilisation except destruction. ‘For this war is a Crusade of Crusades’, Maxwell recalled the Armenian shouting, ‘and it has overthrown the unspeakable Turk and liberated a subject people’. Maxwell seemingly agreed and provided in his memoir a lengthy catalogue of Ottoman misdeeds such as its expansion into Europe and the enslavement of Slavs along the Black Sea.Footnote 82

However important was the freeing of the Arabs, and few soldiers, if any, doubted that the Ottomans had devastated Palestine, others felt that the liberation of the Jews had been the war’s crowning achievement. A. O. W. Kindall, formerly of the Machine Gun Corps, connected Jerusalem’s capture to the Maccabees. ‘After four centuries of conquest, the Turk was ridding the land of his presence in the bitterness of defeat’, he wrote. ‘It was fitting’, Kindall continued, ‘that the flight of the Turks should have coincided with the national festival of Hanukah’ and the ‘re-capture of the Temple from the heathen Seleucids’.Footnote 83 Edwin C. Blackwell and Edwin C. Axe of the 2nd Battalion, Essex Battery, also wrote that it was no coincidence that the capture of Jerusalem occurred on the same date that Judas Maccabaeus had liberated the Holy Temple ‘from the heathen Seleucids’ in 165 BCE. Much to the satisfaction of Palestine’s Jews, wrote the pair, in nearly identical language as Kindall, ‘After four centuries of conquest the Turk was ridding the land of his presence in the bitterness of defeat’.Footnote 84

In Lieutenant Colonel B. H. Waters-Taylor’s post-war memoir The Eighth Crusade, published under the pseudonym ‘British Staff Officer’, he linked the war in Palestine with the end of Ottoman Turkish misrule, as so many others had done, but charged that Britain had been duped by Zionist Jews. Serving under Allenby’s staff during the war, Waters-Taylor was chief of staff, Occupied Enemy Territory Administration, from 1919 to 1920. Staunchly pro-Arab and anti-Zionist, he admonished Britain for betraying the Arabs and gave voice to anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, including his belief that Whitehall had been infiltrated by disloyal Jews and half-Jews. Of the war in Palestine, he wrote, Britain had failed as the previous seven crusades had done. The ten years following the war had convinced him that ‘whereas these [the medieval crusades] failed because their campaigns were abortive, they themselves being defeated on the field of battle, Britain had to forego the fruits of victory because a craven and corrupt Government had mortgaged them to its paymasters, the Jews. Consequently’, he ended, ‘Allenby’s troops fought to their own detriment, for an alien oligarchy to whom they had been sold, and at whose behest and for whose material advantage Britain had surrendered the heritage of Empire’.Footnote 85

Even though Waters-Taylor was retrospectively consumed with Zionist plots undermining Britain’s war effort, he was the exception and not the rule. Far more ex-servicemen looked back fondly on the campaign as one of liberation and far more were sure that they had done the right thing. With the Ottoman Turks evicted from Palestine, liberal imperialism, they wrote, was free to reshape Palestinian politics, economics, and society in Britain’s image. Colonel Philip Hugh Dalbiac’s History of the 60th Division insisted that the capture of Palestine had ‘restored the blessing of civilisation and good government to a country that for upwards of four hundred years had had to submit to the abominations of Turkish misrule’.Footnote 86 With Britain as the international guardian of a ‘New Jerusalem’, it was hoped that the laws and social mores of its liberal empire would reform the city. Frank Fox’s The History of the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars Yeomanry anticipated that British Jerusalem would be a city of open worship – which, probably unbeknownst to him, it had been under Ottoman rule – under the benign sovereignty of the British Empire:

The British people have no place in their minds for religious intolerance. More perhaps than any other people of the world they have a sincere respect for whatever form the aspiration towards God takes in the human heart. In their world-wide Empire, which has more non-Christian than Christian inhabitants, there is the fullest religious liberty. To be not only just but reverent towards the religious views of Moslems, Buddhists, Jews, Pagans, is part of their innate character as well as of their policy. Regarding Jerusalem, they recognise that it was, and is, a Holy City for Moslems and Jews as well as for Christians.Footnote 87

Fox’s point was clear: people of all faiths would be welcome in the ‘New Jerusalem’, which would be governed with the same tolerance and spirit of religious freedom as the rest of the British Empire. Bluett considered Allenby’s promise of religious freedom made during his speech in Jerusalem on 11 December 1917 ‘a triumph for British diplomacy and love of freedom’.Footnote 88 ‘Within three weeks of the signing of the Armistice’, wrote R. M. P. Preston, formerly of the Desert Mounted Corps, ‘unarmed pedestrians travelled alone and unafraid through all the land. On every road were to be seen throngs of refugees returning to their ravished homes.’ It was, in his words, a ‘Pax Britannica’.Footnote 89

Nowhere was the civilising drive greater than in Vivian Gilbert’s memoir The Romance of the Last Crusade. Although Gilbert was occasionally enchanted by the romance of fighting where the medieval crusaders had fought, he never revealed any sort of religious hostility towards Islam nor the belief that Palestine belonged to Christendom. In fact, Gilbert’s first reference to crusading comes early in his memoir and in relation to the war on the Western Front, not Palestine. ‘I wanted to believe that we were all knights dedicating our lives to a great cause’, he wrote of his decision to enlist, ‘training ourselves to aid France, to free Belgium, to crush Prussianism, and make the world a better world place to live in. What did it matter if we wore drab khaki instead of suits of glittering armour?’ he asked rhetorically. ‘The spirit of the Crusaders was in all these men of mine who worked so cheerfully to prepare for the great evidence.’Footnote 90

Still, it was the chance to liberate Palestine and return it to its past glory that dominated his writing. Gilbert dedicated his memoir ‘to the Mothers of all the boys who fought for the freedom of the Holy Land’.Footnote 91 Although he had fought in both France and Macedonia in addition to Palestine, Gilbert thought that the former two had produced nothing more than strategic deadlock and appalling casualties. ‘I had the same feeling’, he wrote, ‘about Macedonia that I had with regard to France; it was all so futile, so little worth while. Men were dying by the thousands but it never seemed to lead anywhere.’Footnote 92 Modern combat and the stalemate of trench warfare had turned Gilbert and his comrades into ‘an army of “wearers down” and “economic exhausters!”’Footnote 93

Coming long before the tide of disillusioned war books, Gilbert’s disenchanted view of the fighting in France and Macedonia was made easier by the fact that he returned to neither front following his transfer to Palestine. He missed both the Hundred Days Offensive that ended with the collapse of Germany and the Allied breakthrough in Macedonia that forced the surrender of Bulgaria. And in trying to answer the question of what his soldiering had done for the war effort and, more broadly, the world at large, Gilbert could only find proof of a just, righteous war in Palestine. Before he turned to the edifying effects of British governance, he catalogued at length the horrors of ‘Turkish misrule and oppression’. Whatever qualities the Ottoman effendi possessed, Gilbert argued, and there were many – ‘charming manners’, ‘highly educated and most hospitable’, ‘overbearing, suave, extortionate and conscienceless’ – the backwardness of Palestine was undeniable proof that Ottoman rule had stifled civilisation. Overtaxation, deforestation, and neglect of social works had made twentieth-century Ottoman Palestine no better, if not worse, than first-century Roman Palestine. At least under Roman rule, wrote Gilbert, aqueducts carried fresh water right into Jerusalem. Under Ottoman administration the inhabitants of Palestine had no other choice but to ‘catch the rain that fell during the winter months on the flat roofs of their houses and store it in tanks in the cellars, where it became foul and polluted as the summer advanced’.Footnote 94

Gilbert concluded his memoir with a passage detailing what he had seen from atop the Umayyad White Mosque in Ramla in October 1920:

In the fields below me they were gathering in the harvest, Christians, Jews, Moslems, Syrians, Bedoueen, Arabs – all gathering in the golden grain … In the distance I could hear a military band at divisional headquarters playing the latest popular dance tune; nearer an Arab boy was playing on his reed flute as he drove his goats to water. We had finished our crusade, peace and freedom were in the Holy Land for the first time in five hundred years – and it all seemed worth while.Footnote 95

High above Ramla, Gilbert had watched as the city’s multi-ethnic and multi-confessional populace tilled the field together, a sure sign of the religious freedom guaranteed by the British Empire; the faint sound of a military band was a reminder of the stabilising force that was the British Army, and the Arab boy tending his flock signalled a return to individual economy and freedom of movement. For Gilbert, it was the pacifying hand of the British Army, a Pax Britannica of sorts (like R. M. P. Preston), that had made Palestine’s return to glory under liberal imperial rule a real possibility.

At least for Robert H. Goodsall, the chance to return to Palestine seven years after the war ended and to see how Palestine had improved under British mandate rule was confirmation that what he and other men had done was worthwhile. ‘At times, perhaps, we are inclined to ask “was it worth while?”’, he ruminated in the final chapter of his memoir. ‘And before the question is formed, in our minds, we know the answer to be “yes,” otherwise the gallant sacrifice of so many of the Sons of our Empire would have been in vain.’ Of his return to Palestine, he wrote,

This year [1925] I have seen a little of the good which follows as war’s aftermath in the great work of reconstruction which is going on in Palestine. Future decreed that I should visit the Holy Land once more. To thus renew acquaintanceship, under happier and more peaceful circumstances, with many well-remembered spots, and to note the great development which has taken place, as a result of British influence during the last seven years, was wonderfully interesting. I make no excuse, therefore, in adding this chapter as an epilogue to my story of the Story of the Last Crusade.Footnote 96

For others, referring to the crusades and other moments in military history was done to lend continuity, order, and purpose to their memoirs. Ex-servicemen had made their mark on world history, so to speak, as the crusaders of medieval England had done. The sociologist James Olney has proposed the critical significance of metaphor in the assembly of meaningful patterns, writing, ‘They are something known and of our making, or at least our choosing, that we put to stand for, and so to help us understand, something unknown and not of our making’.Footnote 97 By relating the past to the present, autobiographers not only ‘organize the self into a new and richer entity’ but also, according to Regina Gagnier, enhance the author’s status as a historical agent.Footnote 98 Thus, to soldier memoirists, El Arish became the place ‘where Baldwin the Crusader, King of Jerusalem’, had died in 1185 CE and where ‘Napoleon’s flag once floated’.Footnote 99 Arsuf was where ‘one of our own kings, Richard the Lionhearted, fought Saladin’, and Acre where ‘Napoleon suffered the first reverse of his meteoric military career’.Footnote 100 Beth-Horon was where ‘our own Richard Coeur de Lion on his last crusade’ had passed.Footnote 101 It was in the footsteps of the ancients that British and Dominion soldiers had fought. The march along the Mediterranean coastline towards Gaza was done on ‘one of the oldest routes in history, the highway between Egypt and Syria, trodden through the ages by “Egyptian and Syrian Kings, by Greek and Roman conquerors, by Saracens and Crusaders, and lastly by Napoleon from Egypt and back again”’.Footnote 102 Palestine had seen ‘some of the fiercest battles of the world’ and was where ‘Thotmes, Rameses, Sennacherib, Cambyses, Alexander, Pompey, Titus, Saladin, Napoleon and many another led his armies where Allenby led us!’Footnote 103 For H. O. Lock, formerly of the Dorsetshire Regiment, Palestine ‘was the cock-pit of the known world’ long before ‘Belgium became the cockpit of Europe’ and where ‘the great wars of Egyptians and Assyrians, Israelites and Canaanites, Greeks and Romans, Saracens and Crusaders’ had been fought.Footnote 104 ‘Verily, history repeats itself!’, wrote the co-authors of a brigade of the RFA, likening their advance to that of Egypt’s pharaohs.Footnote 105 ‘Napoleon’s task was not unlike General Murray’s’, wrote another soldier. ‘His dream was to reach Gaza, and thence to march to Constantinople by way of Damascus and Allepo [sic].’Footnote 106 Lastly, he pointed out, ‘our own troops have passed’.Footnote 107 Lieutenant Colonel E. D. M. H. Cooke of the RFA, an Etonian who had also fought in France, reminded his readers in With the Guns East and West (1923) that the liberating march of the EEF was the latest triumph of an Anglo-Saxon civilisation that had been on an endless moral quest since the Middle Ages. Cooke reworked the medieval crusades into a defence of liberty and justice and slotted the EEF’s campaign into a history of British righteousness, closely connected to the modern people’s knightly ancestors. ‘It seems no part of the Recorder’s duties’, he wrote, ‘to remind us occasionally that England’s renown all the world over for fair play, for chivalry, indeed for her finer points, is the result of traditions and customs handed down to us for generations’.

The fair name we still hold to-day is chiefly due to Britain’s loyal subjects, sailors, soldiers and civilians doing their bit unheard of, many of them living their lives in the far outposts of empire, spreading their influence and justice amongst their fellow-subjects of many races, for ever [sic] conscious of our great heritage. Originated early in our history with the solid foundations and backbone of Great Britain, i.e. the country-bred squires … It was these men, not only in their example of loyalty to king and country, but also in their fighting qualities, who rode as Crusaders to the Holy Land under Richard Coeur de Lion; lord and retainers, who, master and man, from Nottingham and Warwick, Dorset and Gloucester, and other counties, again in this War fought side by side against the enemies of England.

Like nineteenth-century families who looked for crusading ancestors in their line, Cooke told the reader that ‘there were instances in Palestine, in that brisk affair at Huj, of squires and their yeomen, both descendants of those former Crusaders, riding knee to knee for those guns’.Footnote 108

Not only had British and Dominion soldiers written the most recent chapter of the history of warfare and the empire in the Holy Land, they had also succeeded where the ancients and other greats had failed. The regimental history of the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars Yeomanry boasted that the army had achieved ‘that full measure of success which had been denied to Napoleon and to the armies of the Crusades. Their share in that achievement makes their fame secure for ever [sic].’Footnote 109 The history of the 5th Battalion, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment, bragged that the army had moved quickly up the coastline towards Jerusalem, sparing little time and avoiding the ‘fate of the Assyrian, Roman and Crusader forces’.Footnote 110 And they had done so with more obstacles in their way. Neither the crusaders nor Napoleon, who had both sieged and captured Gaza, wrote Adams, had to deal with the logistics or bureaucracy of twentieth-century warfare. ‘Things were altogether less complicated then’, he wrote, ‘one simply spent the morning working up to a suitable pitch of fanaticism or intoxication, foregathered round the walls after a hashish lunch and waited for the holy man to fire the Verey arrow’. The offensive ‘was not allowed to cool under the influence of operation orders and preliminary reconnaissance, but glowed with the promise of well-earned loot and pleasurable atrocities’.Footnote 111

So far we have established that crusading was a byword for the liberation of Palestine from Ottoman misrule and the extension of liberal imperialism, and that connecting their war to the past, both to the crusades and to other periods in military history, was one way ex-servicemen showed that they had made a mark on world history. A third and final answer is that crusading to liberate Palestine also allowed ex-servicemen to compete with the liberation of Belgium. Like soldiers on the Western Front, wrote Wilkie, New Zealanders had fought and died in Palestine for ‘freedom and humanity’.Footnote 112 Some even argued that the crusade to liberate Palestine was fought for more honest reasons than the crusade to liberate Belgium. Bernard Blaser, formerly of the 2/14th Battalion, London Regiment, pushed this argument to its limits. In Kilts Across the Jordan, he dismissed the morality of the war on the Western Front. Britain fought not for the safety and security of the Belgians, he claimed, but most contemptibly to extend its economic sway in Europe. The war in Palestine was fought for different, purer reasons.

Here in Palestine there could be no empty and fallacious reasons for the war we were waging against the Turks, no selfish aims for commercial supremacy, no ‘Remember Belgium’ and other shibboleths which had so sickened us that they became everyday jokes, but the purest of all motivations, which was to restore this land, in which Christ lived and died, to the rule of Christian peoples.

Much like the post-war exasperation with Belgium that had led to anti-Belgian resentment, Blaser believed that it was only in Palestine that the war had been fought for a just cause.Footnote 113 ‘To free the Holy Land’, he explained, ‘from a policy of organized murder, tyranny so awful and despicable as to cause the hearts of the most apathetic to revolt in disgust, was in itself sufficient to urge us to great efforts, to suffer increased hardships without complaint’.Footnote 114 Blaser was not fighting, though, to subject Muslims to the authority of the Anglican Church. Although he referred to the benefits of Christian government, by this time Christian rule and the British Empire had started to shift closer towards a secular and enlightened, although perhaps nominally Christian, definition of governance. He was instead fighting to allow for the transmission of British liberal imperialism – civics, democracy, and enlightenment – to flourish in Palestine.

It is tempting to suggest that soldiers referred to the crusades as a simple marketing gimmick. On the cover of F. H. Cooper’s memoir Khaki Crusaders, for example, is a knight, likely of the Third Crusade, watching the EEF pass by and saluting them. But by exploring how publishers advertised these memoirs and how the public received them, the claim that ex-servicemen used crusading language for commercial purposes quickly breaks down. Cecil Sommers’ Temporary Crusaders was marketed by its publisher, John Lane The Bodley Head, as an ‘amusing account of campaigning in Palestine and the East’.Footnote 115 The publisher Edward Arnold’s announcement of Coldicott’s London Men in Palestine and How They Marched to Jerusalem contained no reference to crusade despite Jerusalem featuring in the title.Footnote 116 Given that both memoirs were published in 1919, when the campaign in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine was still hailed as an imperial success, is telling. Publishers also ignored crusading language in later memoirs. Heath Cranton’s publicity for John More’s With Allenby’s Crusaders marketed the memoir alongside works on equatorial Africa and world travel.Footnote 117 In one of the longest advertisements for an ex-serviceman’s work on Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine, Ernest Benn praised Edward Thompson’s Crusader’s Coast as a welcome escape from the ‘alleged realism’ of other war books but still ignored the EEF’s connection to the medieval crusades.Footnote 118

Just as the publicity of book publishers had ignored crusading language, so too did reviews written by literary critics in the press. Punch’s review of More’s With Allenby’s Crusaders presented the memoir as one of travel and tourism. ‘Captain J. N. More’, the reviewer argued, ‘has, perhaps unconsciously, written an account of places and people in Palestine as they appeared to a lover of the Bible who chanced to explore the country in the middle of a war, rather than a history of a campaign against the Turks’.Footnote 119 In the left-wing Nation, Coldicott’s London Men in Palestine was acclaimed not as a story of a triumphant crusade – in spite of the book’s subtitle, and How They Marched to Jerusalem – but instead as a ‘pleasant book of travel with an army’ told ‘in an honest prose’.Footnote 120 Captain Adams’ The Modern Crusaders was reviewed favourably by The Times Literary Supplement as a ‘slight’ and ‘chatty’ account of the army’s advance under Allenby.Footnote 121 According to the Observer, Thompson’s Crusader’s Coast was best described as a ‘guide to the flora of the Holy Land’. ‘Those who seek excitement’, the reviewer warned, ‘may avoid this book’.Footnote 122 In the Anzac Bulletin’s review of Oliver Hogue’s The Cameliers, the reviewer acknowledged that memoirs on the war in Palestine were

a welcome addition to Australian war literature, if only because it records some of the doings of the Light Horse Regiments and other Australian units, who were unable to share in the fights on the Western Front, but who worthily bore in the Eastern theatre of war the standard of fighting for which the Commonwealth soldiers are so famous.

The reviewer made only one reference to the crusades – apart from the review’s title – referring to the infrastructural developments made in Sinai and southern Palestine by the ‘new Crusaders’ as they marched towards Jerusalem.Footnote 123

No more receptive to crusading language were institutional journal reviews written by other ex-servicemen. In the Army Quarterly, for example, reviewers were more inclined to comment upon a memoir’s handling of military strategy, logistics, or decision-making than the memoir’s worth as a story of holy war against the Muslim Ottomans. Reviewed by C. T. Atkinson, a captain with the Oxford University Officers Training Corps, Preston’s The Desert Mounted Corps was praised for its concision and meticulous attention to detail, and for ‘telling the story of that important force clearly and fully’.Footnote 124

Other reviews acknowledged but rejected the use of crusading language. Reviewing More’s With Allenby’s Crusaders in the Times Literary Supplement, Orlando Cyprian Williams expressed his cynicism of the crusading analogy. ‘Members of the E.E.F., then – Crusaders, if they liked to be called so’, he jibed at the end of his review.Footnote 125

The above points to two conclusions. First, ex-servicemen’s memoirs were neither advertised nor received as stories of a twentieth-century holy war or religious crusade. Publishers’ advertisements did not market them as such and instead promoted their value as travel and geographical literature as well as eyewitness accounts of soldier life in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine. This explanation is further supported by the fact that unpublished memoirs, such as F. V. Blunt’s ‘The Last Crusade: The Diary of a Private Soldier in the Palestine Expeditionary Force 1917–1919’, also employed crusading language when no commercial incentive existed.Footnote 126 Furthermore, no critical reviews bought into the idea that British and Dominion soldiers had crusaded in a holy war. Instead, greater stock was put into a memoir’s truthfulness, its writing style, its grasp of grand strategy, and, in some cases, what it revealed about the daily lives of those who had fought in Sinai and Palestine.

Liberation and Liberal Imperialism

Although one newsreel film by Jury’s Imperial Pictures, ‘Advance of the Crusaders into Mesopotamia’, released in four parts between 1918 and 1920, extended crusade to Mesopotamia, no ex-serviceman remembered the campaign as a holy war.Footnote 127 The crusading narrative had clear limits when applied to the Muslim Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. Ex-servicemen did, however, remember the campaign, like ex-servicemen had remembered Palestine, as a war of liberation and the extension of liberal imperialism. Lieutenant Colonel J. E. Tennant’s In the Clouds above Baghdad charted a ‘chain of corruption’ that had ‘started in Stamboul and ended with the Arab beggar in the bazaar’ of Baghdad. Liberal imperial rule had liberated the people and ended the corruption. ‘The educated Armenian and Jewish classes’, he wrote, ‘hailed us with delight. They knew that the arrival of Englishmen meant fair play, and that their women-folk would be freed from an everlasting peril.’ Armenian and Circassian women were able ‘to walk abroad’, when before,

A Turkish officer might be attracted by the appearance of a Christian woman in the street, and she, under pain of being put in the public hospital by the health officer as diseased, must needs surrender herself for the satisfaction of the Turk. Within a few days of our occupation they had cast off their veils and somber clothing and appeared in bright European creations reminiscent of the accumulations in a Whitechapel emporium.Footnote 128

Tennant was sure that the people of Baghdad found it strange ‘that the conquering British Army did not immediately engage in wholesale looting, massacre, and rape. Instead’, he pointed out, ‘the Baghdadi gaped open-mouthed at the Trooper from the Home Counties or the Jock from Dundee who, after many weeks’ marching and fighting, offered him his last cigarette and carried on strange conversation’, for hatred had ‘no place’ in the ‘heart of the British Tommy’.Footnote 129 Captain J. A. Byrom, formerly of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, thought that Basra under liberal imperial rule was confirmation of the British Empire’s superiority. Commerce had been restored, everyday life made peaceful, and individual liberty returned to the city’s inhabitants. Baghdad’s Jews, he pointed out, had even been allowed to return to wearing western clothes instead of ‘Eastern garments’. ‘The work that had been done in and around’ the city, he wrote in his unpublished memoir, ‘was extraordinary. It is only on seeing things like this that one can appreciate to the full extent what a wonderful little nation we really are. The greatness of Britain can only be realised when one travels from home.’Footnote 130

Reshaping Mesopotamia was about more than making up for the disastrous siege and surrender of Kut al-Amara, as historian Priya Satia has argued.Footnote 131 Ex-servicemen had fought to liberate Mesopotamia as others had fought to liberate Belgium. Lieutenant Colonel Arnold Talbot Wilson compared the plight of Ottoman Mesopotamia to that of German-occupied Belgium. Mesopotamia had been ‘devastated by the supine folly of its former rulers’ like the ‘stricken fields of Flanders’ had been pummelled by the ‘colossal machinery of modern war’ and the German Army. The only difference between the two fronts, argued Wilson, was that British finance and British labour would rebuild Mesopotamia. ‘We, and we alone’, he wrote, ‘had it in our power to enable the peoples of the Middle East to attain a civic and cultural unity more beneficial and greater than any reached by the great Empires of their romantic past’.Footnote 132

Like the aforementioned Blaser and Wilson, who considered the liberation of Palestine and Mesopotamia alongside, if not more important than, the liberation of Belgium, Douglas Walshe of the 708th Motor Transport, ASC, wrote that Macedonia was fought over to liberate the Serbs from Austro-Hungarian occupation. ‘You don’t forgit [sic] about the Belgian’s wrongs’, he wrote as Cockney ‘Private Smith’ in his memoir, With the Serbs in Macedonia,

Walshe, like Blaser, was tired of Belgium dominating the memory of the war. ‘Belgium has always been written up in the Press’, he griped, ‘Belgium has all our sympathies. Belgium was fine – at first. But Serbia has been fine all through.’ ‘We are sick’, he concluded, ‘of the war and irresponsible war-books, and there are so many axes to grind. Enthusiasts are wearisome, foolish people, but facts are facts’.Footnote 134 Another ex-serviceman was confident that ‘Nothing in the whole history of the war, not even the overwhelming of Belgium, is comparable with the mental and physical sufferings of the Serbs during their march across Albania’.Footnote 135 The British Army’s ‘occupation provided a foothold for the remnants of the Serbian army and a starting-point for the hopes of the Serbian people. If we had not been there’, wrote Harold Lake, ‘it is hard to think what would have become of those fine soldiers’.Footnote 136

Liberal imperialism also had a role to play in Greek Macedonia, including Salonika, where the ‘terrible Turk’ had kept Greece ‘down-trodden’ and ‘beneath the heal’ of Istanbul for too long, wrote Lieutenant V. J. Seligman, formerly of the 60th (London) Division. For Seligman, the post-war rebuilding of Greek Macedonia, guided by British and French hands, was the paying off of a centuries-long debt owed to the ‘priceless civilization of Ancient Greece’. Greece stood ‘forth to take her part in history’, he wrote:

She has within her all the fine qualities of a Great Nation; she needs only a wise Government and a noble example to bring them forth. The former she possesses in M. Venizelos: may we not hope that in the latter the example of France and England may be of some real assistance? If so, the thousands of Frenchmen and Englishmen who have fallen in Macedonia will not have died in vain.Footnote 137

War Winners