Homelessness is an important social problem in North America. On any given night, approximately 20 000 people stay in homeless shelters across Canada(1) and over 650 000 Americans experience homelessness each night(2). In addition to lacking stable housing, many of these individuals and families do not have food security(Reference Lee and Greif3–Reference Whitbeck, Chen and Johnson7), which has been defined as ‘physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet … dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’(8). A 1996 national survey of homeless individuals in the USA found that more than 80 % of respondents experienced food insecurity(Reference Lee and Greif3). Food insecurity can have a substantial impact on health; in a recent study of a nationally representative sample of homeless adults in the USA, food insufficiency was associated with higher rates of hospitalization and with more frequent use of emergency departments(Reference Baggett, Singer and Rao9).

Two frequently used instruments for measuring food security in the general population are the US Food Security Survey Module (US FSSM)(Reference Bickel, Nord and Price10) and the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)(Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky11). The US FSSM was developed by the US Department of Agriculture and the US Department of Health and Human Services and has been administered annually in the US Current Population Survey(Reference Bickel, Nord and Price10). The HFIAS was developed through the US Agency for International Development's Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance project and has been applied in numerous countries around the world, particularly in resource-constrained settings(Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky11–Reference Maes, Hadley and Tesfaye13).

The most appropriate instrument for the assessment of food security among homeless people is unclear, and we are unaware of any studies comparing the use of the US FSSM and the HFIAS in homeless populations. The importance of examining the relevance of these food security instruments to homeless people became apparent to us when, in preparation for another study, we pilot tested the US FSSM with a small group of homeless individuals. We received feedback from participants that the US FSSM was not applicable to their situation because of its frequent references to lack of money to buy food. In reality, homeless individuals often obtain food at shelters and meal programmes rather than through personal purchases(Reference Tarasuk, Dachner and Poland4, Reference Cowan, Hwang and Khandor14, Reference Darmon15). Therefore, we developed a slightly modified version of the US FSSM questionnaire in which monetary references were removed, with the hypothesis that the modified version would be more likely to detect food insecurity among homeless individuals compared with the standard US FSSM.

The present study had two specific goals. The first goal was to compare the HFIAS, the US FSSM and the modified version of the US FSSM in terms of their classification of food security levels among individuals who are homeless. The second goal was to determine which of these instruments was the most understandable, applicable and appropriate to assess food security from the perspective of homeless individuals.

Experimental methods

Study sample and data collection

We recruited fifty study participants between January and July 2010 from seven shelters and three drop-in programmes that serve homeless individuals in Toronto, Canada. The shelters and drop-ins constituted a convenience sample selected from a list of all such programmes in Toronto. Potential participants were identified by programme staff and screened for eligibility by a research investigator. Participants had to be ≥18 years of age, able to communicate in English and currently homeless. Homelessness was defined as sleeping at a shelter, or in a park, outdoor location, vehicle or other location not intended for human habitation for the past seven nights. Five participants were recruited at each programme site. Participants gave informed consent and received a $CAD 10 honorarium. The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of St. Michael's Hospital.

Two researchers (A.C.H. and M.C.K.) administered face-to-face surveys that obtained information on demographic characteristics and the number of meals obtained at shelters or meal programmes over the past 7 d, and which included the HFIAS, the US FSSM and the modified US FSSM. The order of administration of the three instruments was randomized. The HFIAS was administered either before or after the two US FSSM questionnaires on a random basis. The ordering of the US FSSM and the modified US FSSM was also randomized. The number of seconds required to complete each instrument was recorded.

After completing each food security instrument, participants were asked to rate how easy it was to understand on a 10-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating ‘very hard to understand’ and 10 indicating ‘very easy to understand’. Relevance was evaluated by asking participants to rate how well it applied to their current situation on a scale from 1, indicating ‘doesn't apply at all’, to 10, indicating ‘very much applies’. After completing the US FSSM and the modified US FSSM, participants were given paper copies of each instrument and asked to indicate which one of the two was better for administration among people who are homeless. After completing all three instruments, participants were again given paper copies of each instrument and asked to indicate which one of the three was the best for administration among people who are homeless.

Food security instruments

The 2008 version of the US FSSM for single adults was administered using a 30 d reference period (Appendix 1)(Reference Bickel, Nord and Price10, 16). The US FSSM assigned respondents to one of the following categories: high food security, marginal food security, low food security or very low food security. The modified US FSSM was created by removing monetary references (Appendix 1). For example, the statement ‘I worried whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more’ was changed to ‘I worried whether my food would run out before I could get more’, and the question ‘In the last 30 days, did you ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn't enough money for food?’ was changed to ‘In the last 30 days, did you ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because you couldn't get enough food?’ The modified US FSSM was otherwise administered and scored according to standard methodology for the US FSSM.

The HFIAS was administered and scored according to standard guidelines (Appendix 2)(Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky11). The version of the HFIAS for single individuals was used. The HFIAS assigned respondents to one of the following categories: food secure, mildly food insecure, moderately food insecure or severely food insecure.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistical software package version 16·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The classification of food security was determined for each pair of food security instruments (US FSSM v. modified US FSSM; HFIAS v. US FSSM; and HFIAS v. modified US FSSM). The κ statistic was used to assess the level of agreement between instruments. For these analyses, the following US FSSM and HFIAS food security categories were considered to be approximately comparable: high food security/food secure; marginal food security/mildly food insecure; low food security/moderately food insecure; and very low food security/severely food insecure. The Friedman test was used to examine differences in understandability and applicability ratings and in administration times among the three instruments.

Results

Study participants

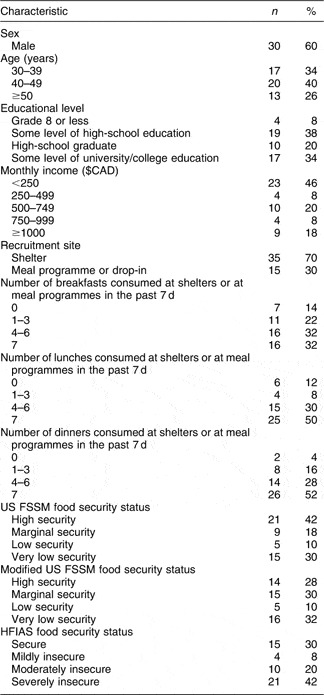

The characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The majority were men, and most were between the ages of 30 and 49 years. Almost half of the participants had a monthly income of <$CAD 250. In all, 70 % of participants were interviewed at shelters and 30 % were interviewed at drop-in programmes. About half of the participants had eaten lunch at a shelter or meal programme every day for the past 7 d, and similarly for the number of dinners eaten in the past 7 d. The proportion of participants with very low food security was 30 % on the basis of the US FSSM and 32 % on the basis of the modified US FSSM. The proportion of participants who were severely food insecure was 42 % on the basis of the HFIAS.

Table 1 Characteristics of the participants (n 50)

US FSSM, US Food Security Survey Module; HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale.

Comparison of food security classifications

The level of agreement between the category of food security assigned by the US FSSM and the modified US FSSM was moderate (κ = 0·61). A total of 72 % of participants were assigned to the same food security category by the US FSSM and the modified US FSSM (Table 2). However, the modified US FSSM assigned 20 % of participants to a lower food security category compared with the US FSSM and only 8 % to a higher food security category.

Table 2 Comparison of food security categories assigned by the US FSSM and the modified US FSSM among a sample of homeless adults (n 50) in Toronto, Canada

US FSSM, US Food Security Survey Module.

κ = 0·61 for US FSSM v. modified US FSSM.

The level of agreement between the HFIAS and the US FSSM and between the HFIAS and the modified US FSSM was only fair, with κ values of 0·44 and 0·38, respectively. As shown in Table 3, the HFIAS assigned 30 % of participants to a lower food security category compared with either the US FSSM or the modified US FSSM, and only 10–16 % of participants to a higher food security category. Among twenty-one individuals designated as having high food security by the US FSSM, ten (48 %) were classified as being mildly, moderately or severely food insecure by the HFIAS.

Table 3 Comparison of food security categories assigned by the HFIAS, the US FSSM and the modified US FSSM among a sample (n 50) of homeless adults in Toronto, Canada

HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; US FSSM, US Food Security Survey Module.

κ = 0·44 for HFIAS v. US FSSM; κ = 0·38 for HFIAS v. modified US FSSM.

Administration time, understandability and relevance

The HFIAS took significantly longer to administer than the US FSSM and modified US FSSM (median = 113, 79 and 75 s, respectively; P < 0·001; Table 4). All three instruments were rated as very easy to understand by the vast majority of participants. In terms of applicability to their current situation, the median rating was highest for the HFIAS and lowest for the US FSSM, but these differences were not statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 4 Administration time and participants’ ratings of food security instruments among a sample (n 50) of homeless adults in Toronto, Canada

HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; US FSSM, US Food Security Survey Module; IQR, interquartile range.

*Rated on a scale of 1–10, where 1 was ‘very hard to understand’ and 10 was ‘very easy to understand’.

†n 49; rated on a scale of 1–10, where 1 was ‘doesn't apply at all’ and 10 was ‘very much applies’.

Preference

When asked to compare the US FSSM with the modified US FSSM and indicate which one of these two instruments would be better for administration among people who are homeless, 44 % of respondents selected the modified US FSSM, 30 % selected the US FSSM and 26 % had no preference, were undecided or stated that it depended on the situation. When asked to compare all three instruments (the US FSSM, the modified US FSSM and the HFIAS), 62 % of respondents selected the HFIAS as the best instrument for people who are homeless (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Instrument selected by study participants (n 50) as the best one to ask people who are homeless (![]() , the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale;

, the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; ![]() , the modified US Food Security Survey Module;

, the modified US Food Security Survey Module; ![]() , the US Food Security Survey Module;

, the US Food Security Survey Module; ![]() , no preference or undecided)

, no preference or undecided)

Discussion

The assessment of food security among people experiencing homelessness is an important challenge. In the present study, the US FSSM, the modified US FSSM and the HFIAS yielded differing results in a sample of homeless adults. The level of agreement for ratings of food insecurity was moderate for the US FSSM compared with the modified US FSSM, and only fair for the HFIAS compared with either the US FSSM or the modified US FSSM. The modified US FSSM, in which respondents were asked about getting food rather than buying food, was more likely to assign participants to a lower food security category compared with the standard US FSSM. This finding suggests that homeless individuals sometimes experience food insecurity in ways that they do not directly attribute to a lack of money to buy food. Another important observation was that the HFIAS assigned almost one-third of homeless individuals to a lower food security category compared with either the US FSSM or the modified US FSSM.

Our findings suggest that the HFIAS should be considered the preferred instrument for the assessment of food insecurity in homeless populations. In particular, the majority of homeless individuals in our study selected the HFIAS as the best instrument for people who are homeless. Although the HFIAS took longer to administer than the US FSSM, the additional time required was <1 min. Our study also suggests that, if the US FSSM is used in homeless populations, a slightly modified version that asks about the ability to get food rather than the ability to buy food may be more appropriate.

Certain limitations of the present study should be noted. Participants were recruited from a single city, and our sample was not large enough to compare responses from different subgroups of the homeless population. As the homeless population is diverse, it is possible that different instruments would be more appropriate for different subsets within the homeless population. The use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of our results. In addition, in our analysis we have compared approximately comparable but non-equivalent ordinal categories of food security used by the HFIAS and the US FSSM. The non-equivalence of these categories is a potential limitation of the present study. In addition, as the present study was conducted in a large urban centre where many services were available for homeless individuals, our findings may not be reflective of the food security experience of homeless populations in more service-deprived areas.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that the HFIAS is a more appropriate instrument than the US FSSM for measuring food security among homeless adults. Further research on the validity and reliability of the US FSSM, the modified US FSSM and the HFIAS in homeless populations would be welcome. Studies on the relationship between food insecurity as measured by these three instruments and important health outcomes are also needed.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported in part by a Keenan Research Centre – St. Michael's Hospital Summer Student Scholarship. The Centre for Research on Inner City Health gratefully acknowledges the support of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, nor of any of the above-mentioned organizations. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. A.C.H. and S.W.H. designed the study; A.C.H. conducted interviews, performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript; M.C.K. conducted interviews, performed the analysis and helped to draft the manuscript; S.W.H. supervised all stages of data collection and analysis and wrote some sections of the manuscript. The authors thank the faculty and staff of the Determinants of Community Health, Course 2, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, for their advice and guidance.

Appendix 1

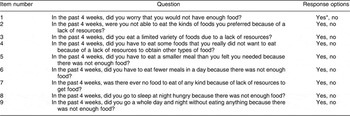

Standard and modified US FSSM questions and response options

US FSSM, US Food Security Survey Module; DK, do not know.

*US FSSM and modified US FSSM response options were identical.

†Text italicized here to highlight differences between questions (not italicized in study instruments).

Appendix 2

Household Food Insecurity Access Scale questions and response options

*If a given question was answered affirmatively, respondents were subsequently asked the follow-up question ‘How often did this happen?’. Response options for follow-up questions were: rarely (once or twice in the past 4 weeks), sometimes (three to ten times in the past 4 weeks) and often (more than ten times in the past 4 weeks).