1. Introduction

Corporate governance has attracted considerable interest in the post-war period (see for example Gordon and Ringe Reference Gordon and Ringe2017; Engwall Reference Engwall2018). A dominant model in that context is the principal-agency model (Alchian and Demsetz Reference Alchian and Demsetz1972; Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1976; Fama Reference Fama1980). Central to this approach is the problem for owners (principals) to have managers (agents) work fully in their interest. Later work in the same tradition in the 1990s includes Fligstein (Reference Fligstein1990), Roe (Reference Roe1994), Blair (Reference Blair1995), Monks and Minow (Reference Monks and Minow1995), and Keasey et al. (Reference Keasey, Thompson, Wright, Keasey, Thompson and Wright1997). Other scholars have chosen to focus on the relations between corporations and their various stakeholders (Freeman Reference Freeman1984; Aoki et al. Reference Aoki, Gustafsson and Williamson1990; Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and De Colle2010).

However, neither of the two above-mentioned approaches works well for organizations that lack owners and customers. One such group of organizations is philanthropic foundations, which have become increasingly important in economies where individuals have been able to build up considerable fortunes. In the United States, the Carnegie Corporation, the Ford Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation have long been significant examples (Berman Reference Berman1983; Gemelli Reference Gemelli2001; Anheier and Hammack Reference Anheier and Hammack2010; Krige and Rausch Reference Krige and Rausch2012). A recent addition to this group of very rich US foundations is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Two European examples are the British Wellcome Trust and the German Volkswagen Foundation (Anheier and Toepler Reference Anheier and Toepler1999; Hall and Bembridge Reference Hall and Bembridge1986; Nicolaysen Reference Nicolaysen2002).

The fact that foundations lack owners and customers makes it appropriate to analyse their characteristics of governance, which is the aim of this article. To this end, the next section will present a framework for such an analysis. It will be used in a study of the first centenary of a major Swedish philanthropic foundation, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. This analysis will lead up to some general conclusions that will be presented at the end of the paper.

2. Governance and Foundations

As mentioned above, the principal-agency approach focuses specifically on the relationship between owners and managers. The stakeholder approach, on the other hand, takes a wider perspective. In the words of Freeman (Reference Freeman1984, 46): ‘A stakeholder in an organization is (by definition) any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives’. However, as pointed out by Freeman et al. (Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and De Colle2010, 208) this definition of stakeholders has problems, as it is too inclusive:

Indeed, on this definition, one could imagine virtually anyone, or any organization […] Given such a wide view of what the term might mean, the notion of stakeholder risks becoming a meaningless designation. If all are stakeholders, then there is no point in using the term.

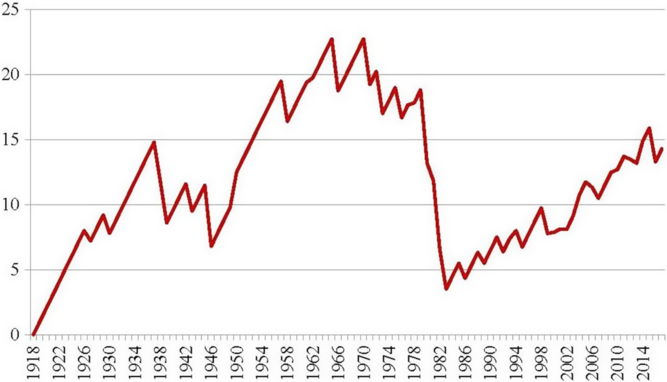

A way to handle this problem is to focus on those stakeholders that appear particularly significant for all organizations (Figure 1). As pointed out by the proponents of the principal-agency approach, owners constitute such a group. They may benefit from the revenues of the corporation and have the last word in times of economic problems. A condition for the avoidance of the latter are sufficient payments from a second group of significant stakeholders, not taken into consideration by the principal-agency approach, customers. They put pressure on the corporation with their demand. A third group, also neglected by the principal-agency approach, is regulators. These are important in determining the rules of the game and in having the power to punish corporations that are not behaving according to these rules.

Figure 1. Corporations, regulators, owners and customers.

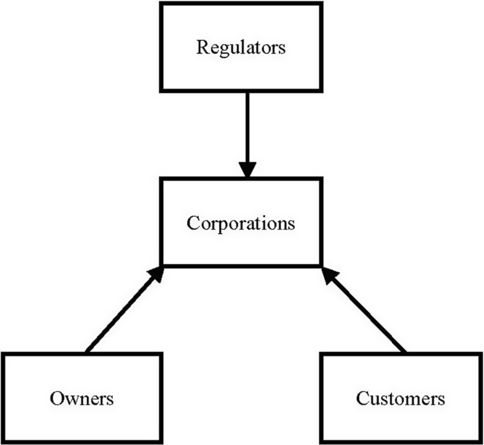

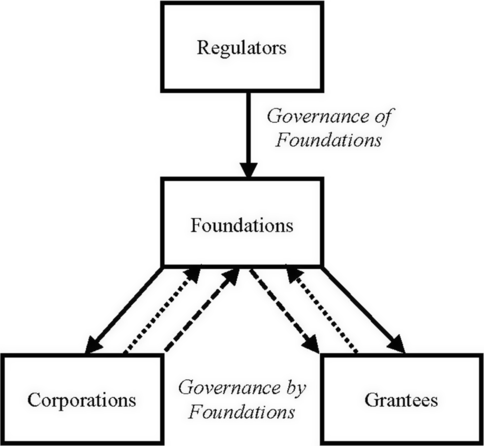

The model shown in Figure 1 is applicable for corporations. However, it is not for foundations. While regulators still constitute a significant group, foundations have no owners and no customers. Instead of owners, foundations have a relationship to corporations represented in their asset portfolio (Figure 2). And, this relationship is the inverse to that between corporations and owners, that is, foundations govern corporations through their ownership. Similarly, foundations have no customers that purchase goods and services but instead grantees that obtain grants from the foundation. Therefore, it is just regulators that are active in the governance of foundations, while corporations in the asset portfolio and grantees are subject to governance by foundations. These two types of governance will be further discussed in the following.

Figure 2. Foundations, regulators, corporations and grantees.

2.1 Governance of Foundations

The fact that foundations do not have any owners means that donors cannot use what Albert Hirschman has labelled ‘the exit option’, i.e. the possibility of withdrawing their stakes (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970). Once a donation has been given, it cannot be taken back. In addition, donors are to a certain extent also restricted regarding the use of what Hirschman called ‘the voice option’, i.e. expressing views on operations. Although donors may be represented on the board of a foundation, they will have difficulty changing its purpose without permission from regulators, something that is generally problematic to obtain. However, within the limits of the purpose of the foundation as formulated in the statutes, donors and their followers can express their voice.

The statutes of a foundation thus constitute its fundamental governance document. Therein, two paragraphs are of particular significance: (1) the purpose of the foundation and (2) the rules for the composition of the board. In terms of the first issue, tax rules have often been determinative, i.e. purposes that are associated with rules for tax exemption. As for the second issue, it is important to note that the absence of owners generally means that existing board members select new board members. Exceptions to this state of affairs are foundations where the statutes prescribe that certain external bodies have the right to nominate new board members.

The circumstance that foundations do not have any owners and that they are often exempted taxation means that regulators set up special rules for their scrutiny. Two issues are crucial in that context, i.e. (1) that grants are compatible with the ends stipulated by the statutes and (2) that the foundation follows the tax rules. Violation by a foundation of either of these types of rules may impose taxation or legal sanctions.

2.2 Governance by Foundations

Foundations are in most cases supposed to assure themselves a long-lasting life by limiting their grants to the annual revenues from the assets, normally adding a small part of the revenues to the capital. Therefore, asset management becomes a significant task. If statutes do not limit asset allocation to government bonds, foundations are likely to invest in the stock market, thereby providing opportunities to be involved in corporate governance. For most foundations, their role therein may be restricted, as they strive to spread their risks by investing their capital in a number of disparate companies and thereby have limited stakes in relation to the total capital of individual corporations. If so, foundations are generally loyal investors who do not use their voice, often abstaining from the exit option with reference to their eternal time horizon. However, it does happen that foundations join other actors by giving proxies for voting at shareholders’ meetings or that they have considerable stakes in particular companies. The latter case is especially interesting, as it entails rather far-reaching opportunities for influencing corporate governance.

In terms of governance through resource allocation, foundations provide an alternative to the traditional allocation mechanisms in society: politics and markets (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1977). However, for some this is controversial. In the words of Megan Tompkins-Stange: ‘Why should Bill Gates decide how our children should be educated?’ (Tomkins-Stange Reference Tomkins-Stange2016a, Reference Tompkins-Stange2016b). Criticism can also sometimes be heard from the scientific community about the allocation of foundation resources to research. However, generally the extra money provided by foundations is associated with positive attitudes, particularly among those who receive the grants.

In fact, foundations add to the plurality of funding. This is not least important in terms of research. As pointed out by Thomas S. Kuhn, innovative research risks being hampered by the dominant actors within a discipline, who tend to protect their own type of research and theories (Kuhn Reference Kuhn1962). Plurality of funding may therefore provide better opportunities for innovative research (Engwall and Hedmo Reference Engwall and Hedmo2016).

2.3 Implications

The above means that foundations have some characteristics that distinguish them from most other organizations in general and corporations in particular (Table 1). First, they differ by not having any owners. This in turn has the implication that donors after having given their donation cannot use the exit option. In addition, foundations lack customers demanding various types of goods and services. In fact, the task of foundations is not to produce goods or services but instead to be active in asset management and grant distribution. The two types of organizations also differ in terms of their goal and time horizon. Corporations − particularly the quoted ones that are subject to what has been labelled ‘quarterly capitalism’ – tend to be oriented towards short-term profits. Foundations, on the other hand, aim at securing a long-term granting capacity, many of them with an eternal time horizon.

Table 1. A comparison between corporations and foundations.

In view of the above, this article will address three research questions:

-

(1) What are the characteristics of the governance of foundations?

-

(2) What role do foundations play for corporate governance?

-

(3) What role do foundations play for resource allocation?

In an effort to answer these questions, this article will provide an empirical analysis of the first centenary of a significant Swedish foundation, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (the KAW Foundation in the following), created in 1917. This in turn will provide the basis for the more general conclusions at the end of the paper.

3. The KAW Foundation

‘Maybe it is egoistical to give while one is still alive but oh, what fun it is’ (Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 64). These were the words of the Swedish banker Knut Agathon Wallenberg in a letter of 9 June 1937 to the Swedish Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf after a donation to the Swedish Institute in Rome from the KAW Foundation. At the time, the latter had existed for 20 years; the year 2017 marked its centenary.

The KAW Foundation was the result of a donation from Knut and Alice Wallenberg, who had been married since 1878, with no children. The original endowment was a promissory note of SEK 20 million mortgaged on 4000 lots in Stockholms Enskilda Bank (SEB in the following) and 10,000 shares in the industrial holding company, Investor, founded by the bank in 1916, the year before the KAW Foundation (Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 82). Ultimately, Knut and Alice would donate assets representing an additional SEK 7 million (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993a, 134).

Knut was the second son in the first marriage of André Oscar Wallenberg (1816–1886), who founded SEB in 1856. At the age of 21, Knut was elected to the SEB board. Twelve years later, upon the death of his father, he became its CEO. He had then got a number of half-sisters and half-brothers, among whom one of the latter, Marcus Wallenberg Sr. (1864–1943), would play significant roles in both SEB and the KAW Foundation (see Tjerneld Reference Tjerneld1969; Gårdlund Reference Gårdlund1976; Nylander Reference Nylander, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993, 17–64; Olsson Reference Olsson2006; Wetterberg Reference Wetterberg2014, 175–178).

The basis for the foundation was the fortune that Knut Wallenberg had amassed as a major owner of the family bank, SEB. He had gained that position by successively buying lots in SEB during its difficult times in the 1870s and the 1880s. This turned out to be a very profitable investment: between 1886 and 1918, the price of the shares rose almost ten-fold (Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 82).

Knut Wallenberg was not only a banker, however. He was also involved in politics: Member of the Stockholm City Council (1883–1915), Member of the Upper House of the Swedish Parliament (1907–1919), and Foreign Minister (1914–1917) (Vem är det? 1925, 788). As a result, Knut Wallenberg had close connections to Sweden’s top leaders, a circumstance he would take advantage of in the governance of the KAW Foundation (see below).

As will be evident in the following section, the first century of the KAW Foundation − based on changes in the conditions for its governance – can be divided into three periods. The first runs on until 1971, that is, before SEB merged with Skandinaviska Banken, thereby radically changing the conditions stated in the original statutes. The second period includes the years from 1972 until 1995, before the introduction in 1996 of a new state regulation of foundations, while the third period comprises the years thereafter (1996−2017).

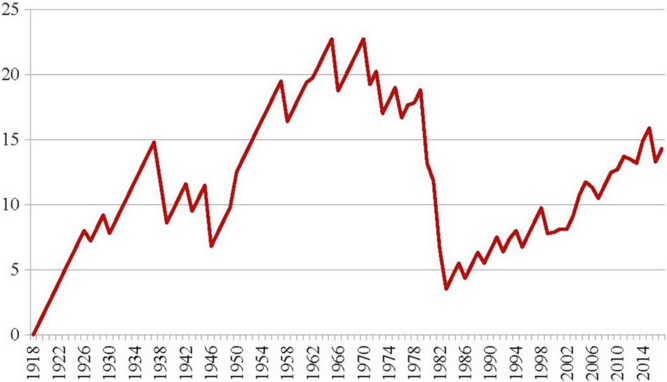

At the end of the third period, the KAW Foundation had developed to a position as the largest Swedish private research-funding foundation. The original donations had by the beginning of the same period grown to a market value of almost SEK 20,000 million, and had at the end of the period grown further to a level above SEK 100,000 million (see Figure 3).

Thanks to the growth in asset value, the KAW Foundation has been able to provide increasing amounts for grants, particularly since the 1990s. Thus, while the average sum granted per year in the first period was SEK 3 million, it was, in the second period, SEK 133 million and SEK 1033 million in the third period, with an all-time high in 2017 of SEK 1784 million (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Market values of the KAW foundation assets 1996−2017 (MSEK).

Source: Annual Reports of the KAW Foundation 2003−2017 and information from the KAW Office for 1996–1998.

Figure 4. Annual grants from the KAW Foundation 1918−2017 (MSEK).

Source: Hoppe (Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993b, 134 and 221) and Annual Reports of the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation 1993−2017.

4. The KAW Foundation and Regulation

Various types of regulation constitute the fundamental rules for a foundation like the KAW Foundation. These external rules then have effects on the statutes and the composition of the board. These three components are significant for our analysis of the governance of the KAW Foundation.

4.1 Regulation

At the time of the creation of the KAW Foundation in 1917 there was no particular legislation regarding the governance of Swedish foundations, although discussions regarding regulation had been going on since the 1850s. However, various proposals had been turned down, a circumstance that demonstrates the difficulty of finding proper regulation for foundations (Hessler Reference Hessler1952, 7−13). It was not until 1929 − 12 years after the establishment of the KAW Foundation – that an act was finally passed (Isoz Reference Isoz1997, 12–13). It stated that a foundation should be registered with the county governor in the county where the foundation had its seat (§1). Such registration was to include the foundation statutes, which should specify the name of the foundation, its purpose, its management, auditing procedures, and board composition (§§4–5). Foundations were also required to keep accounts of assets, debts, revenues and expenses (§14). Following registration of a foundation, the county governor would become its supervisor (§8, §9 and §15) (Lag 1929:116).

These rules from 1929 governed Swedish foundations until 1995, when the Swedish Parliament passed a new act that came into effect from 1 January 1996. The path to this decision demonstrates again that the governance of foundations is associated with great difficulties. Discussions regarding the governance of foundations had started 20 years earlier, not least in view of a scandal in the Wenner-Gren Foundations in the early 1970s (Wallander Reference Wallander2002). As a result, a Government Commission had been set up in 1975 to propose a new act. However, following disagreements in the commission, the preparation of a new act was taken over in 1983 by the Ministry of Justice. It then took more than a decade to formulate a bill for a new act (Stiftelselag 1994:1220; Isoz Reference Isoz1997, 13–17). It was considerably more extensive than its predecessor with as many as 11 chapters. One of the early paragraphs stated that a foundation should have a name that includes the Swedish word for foundation (stiftelse) (§6) and that other organizations could not use this term. In this way, foundations were provided with an arrangement similar to that of banks with their charters (see for example Sinkey Reference Sinkey2002, 16–17).

The subsequent chapters of the act provided rather detailed specifications of rules that are particularly significant for the governance of foundations, i.e. asset management, board composition, accounting, and supervision. As for the latter, the county governors continued to be supervisors of foundations. An important new feature was the sixth chapter, which placed rather strict restrictions on changes in the statutes (Stiftelselag 1994:1220; Isoz Reference Isoz1997).

Distinct from the Act on Foundations, the Swedish Parliament had as early as 1972 passed an act giving the government the right, for a trial period of three years, to appoint one board member and a deputy board member in 30 investment companies and foundations (Ds I Reference Ds1980:1; Lag 1982:315). On 1 April 1973, the Government appointed such representatives for 22 investment companies and eight foundations. Such representatives were kept until the new Foundation Act came into force in 1996.

Overall, there is thus evidence of considerable interest from Swedish politicians to find means to govern foundations through private law. This was justified by the influence of foundations as well as their lack of owners, but also by their favourable treatment with respect to fiscal law. As early as in the nineteenth century there had been tax exemptions for a group of public organizations, including what was labelled pious foundations. In 1928, these rules were extended to a wider population of foundations (Proposition 1928:214; SOU 1939:47, 14–34; Hagstedt Reference Hagstedt1972, 136–143).

An additional change to relieve foundations from taxes was the stipulation in 1942 of the criteria for tax exemption. They entailed that tax exemption could be granted foundations aiming to (1) strengthen the defence of the country, (2) promote the care and the upbringing of children, (3) support teaching or education, (4) carry on charity work among the needy, and (5) promote research. Additional conditions for tax exemption were that the foundation should not be geared to supporting particular families or persons and that they should distribute a reasonable share of the revenues to beneficiaries. (SOU 1995:63, 60 and 73).

As of 1 January 2014, revised rules specified three conditions for tax exemption: (1) a mission of doing public good, (2) activities that are 90–95% in accordance with the purpose of the foundation, and (3) giving out grants that represent 80% of the net revenues. In terms of the first condition, the new rules have extended, in addition to the previously specified aims, the definition of public utility to include sports, culture, environmental conservation, political activities, religious activities, and health care (Skatteregler för stiftelser 2016, 2–3; Gunne and Löfgren Reference Gunne and Löfgren2014).

4.2 Statutes and Boards of the KAW Foundation

4.2.1 Statutes

The original statutes of the KAW Foundation had nine paragraphs (Hoppe et al. Reference Hoppe, Nylander, Olsson, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993, 12–13). They provide strong evidence of a quite close relationship to SEB. The bank was to appoint the board and keep the assets of the Foundation. In addition, the auditors of the bank were to be the auditors of the Foundation, and SEB’s annual meeting was to decide on the discharging of liability of the Foundation board as well as − together with the bank board − deciding on action in the case of the discontinuity of the bank. Finally, the annual meeting of the bank was to represent the donors after their death in cases of changing the statutes. It is also worth noting that the original donation consisted of shares in the closely associated investment company, Investor, and that the promissory note was mortgaged on lots in SEB. In other words, there was, from the beginning, a considerable symbiosis between the KAW Foundation and SEB.

With time, the KAW Foundation has made three significant changes in its statutes. The first occurred in 1928 as a response to political discussions regarding the taxation of foundations (cf. above). The original second paragraph regarding the purpose of the foundation, which originally had been ‘satisfying religious, charitable, social, scientific, artistic, or other cultural ends and promoting trade, industry, and other lines of business within the country’ (my translation) was changed to ‘[promoting] scientific research, training and other educational work of national interest’ (official translation provided by the KAW Foundation).

A second significant change occurred in 1947 in the paragraph regulating the composition of the board, which according to the founding statutes was to consist of the Chairman, the Vice Chairman, and the CEO of SEB, with two additional members appointed by the directors of SEB. As a precaution relating to fears of the nationalization of Swedish banks, this paragraph was changed to simply say that the board should consist of four to seven Swedish men [sic!] (Olsson Reference Olsson, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993, 78).

The third significant change occurred in 1971, which was a turbulent time for the KAW Foundation for two reasons. First, there was the legislation introducing state representation on the boards of the major Swedish foundations (cf. above), among them the KAW Foundation, as well as a proposed merger between SEB and the Skandinaviska Banken (see further Olsson Reference Olsson2000, 374–380: Lindgren Reference Lindgren2007, 399–408). In relation to the latter, the two sons of the founder’s stepbrother, Marcus Sr., were in disagreement: Marcus Jr. favoured the merger, while Jacob was against it. Marcus won out, and the merger was undertaken, which had the effect that a Council of Principals consisting of representatives of a selection of Swedish universities and academies meeting once a year took over the role of SEB in relation to the foundation (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993a, 117–118).

4.2.2 The KAW Foundation Board

The rules of the foundation statutes regarding the board resulted in strong family representation in the first period (1917−1971). Board members also had long tenures. During the first 55 years of the KAW Foundation, the board had only 15 members (Table 2). The majority (eight) were Family members (Knut, Marcus Sr., Oscar, Jacob, Marcus, Axel, and Marc), two (Joseph Nachmanson and Robert Ljunglöf) were Executives within the Wallenberg sphere, three (Otto Printzsköld, Johannes Hellner, and Nils Vult von Steyern) were prominent Officials and two (Arne Tiselius and Ulf von Euler-Chelpin) were distinguished Academics. A particularly interesting feature of the board composition is the addition of members outside the family and family sphere, first Officials and then Academics, an apparent reflection of a wish to gain legitimacy in society. The move from Officials to Academics was obviously a result of the reorientation of the grants given (see further below).

Table 2. KAW board members in the first period (1917–1971).

Source: Dahlberg et al. (Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 75).

Key: A = Academic, F = Family, O = Official and W = Executive within the Wallenberg sphere.

After the creation of the Council of Principals in 1971, the link to academia became even stronger in the second period (1972–1995) (see Table 3). This was particularly the case after 1976, when the Council of Principals was given the right to nominate a member to the KAW Board (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993a, 117–119). Such elected members were all former Vice Chancellors (in order: Lennart Stockman and Gunnar Brodin of the Royal Institute of Technology, Håkan Westling of Lund University, and Mårten Carlsson of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences). Yet another link to the scientific community was the appointments in 1981 and 1992 of two other former Vice Chancellors (Gunnar Hoppe of Stockholm University and Jan S. Nilsson of Gothenburg University) as Executive Members of the Board. The representation of Academics increased further with the appointments in 1983 of the 1982 Medicine Nobel Laureate Sune Bergström and the Gothenburg Professor of Medical Microbiology Jan Holmgren in 1992.

Table 3. KAW board members in the second period (1972–1995).

Source: Dahlberg et al. (Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 75).

Key: A = Academic, F = Family, O = Official and W = Executive within the Wallenberg sphere.

Another significant change was the addition of state representatives in major foundations between 1973 and 1995 (see above). The first such KAW board member was the Director General of the National Swedish Board of Health and Welfare, Bror Rexed, followed by a series of MPs from the Centre Party (Christina Rogestam, Anders Dahlgren, and Torbjörn Fälldin). At the same time, the Wallenberg representation increased through the election of the Wallenberg Executive Curt Nicolin and the two cousins Jacob and Marcus (both born in 1956). The result was that the composition of the KAW board changed from one of Family domination with three family members, and one Academic in 1972 to one of four Academics, three Family members, one Executive, and one Official in 1995.

In the third period (1996–2017), the family representation increased anew (Table 4). Jacob’s brother, Peter Jr. and Marcus’ brother, Axel, and sister, Caroline, were elected to the board, in 1999, 2000 and 2012, respectively. Other board members elected after 1996 were three Wallenberg Executives (Björn Svedberg 1999–2004, Björn Hägglund 2006–2016 and Michael Treschow 2007–) and six Academics (Janne Carlsson 2001–2007, Erna Möller, Executive Member 2002–2009, Bo Sundqvist 2007–2013, Göran Sandberg, Executive Member 2010–, Kåre Bremer 2014– and Pam Fredman 2017–). Of the latter, Carlsson, Sundqvist, Sandberg, Bremer, and Fredman had all been Vice Chancellors. In this way, the link to the leadership of Swedish universities was strengthened. At the same time, there is no evidence that the legislation passed in 1995 had any visible effects on the recruitment to the KAW Board.

Table 4. KAW board members in the third period (1995–2017).

Source: Dahlberg et al. (Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 75).

Key: A = Academic, F = Family, O = Official and W = Executive within the Wallenberg sphere.

4.3 The Centenary as a Whole

The above analysis demonstrates that the first ten years of the KAW Foundation passed without any specific regulation of Swedish foundations, followed by one act of legislation in 1929 and another in 1995. However, although these laws were important for the governance of the foundation, other things appear to have been more influential in terms of its statues: (1) threats of changes in taxation rules in 1928; (2) threats of nationalization of banks in 1947; and (3) the merger between SEB and the Skandinaviska Banken. Thus, the governance of foundations thus seems to go beyond strict legislation.

A notable feature of the KAW Board is the low turnover of board members. During its first century of existence, the KAW foundation had only 41 board members. Some of them had rather long tenures: Jacob Wallenberg 53 years, Marcus Wallenberg and Peter Wallenberg both 44 years, and Marcus Wallenberg Sr. 25 years. In this way, there has been considerable continuity in the board, with a steady increase in the average tenure until 1937, when it declined for a few years only to reach an all-time high of 23 years in 1965 (Figure 5). It then plummeted to 3.5 in 1983 and has, since then, again continuously risen.

For several decades, the Family and Wallenberg Executives together had a majority on the KAW Foundation board, above 70% (Figure 6). In the 1970s and early 1980s, they lost this position, reaching an all-time low of 20% in 1982. Since then, the share has gradually increased again to 70%. The decline was not only an effect of state representation but also the appointment of several Academics to the board. This latter representation, which began in the 1960s with the appointments of Nobel Laureates, has no doubt been important for the general legitimacy of the KAW Foundation. It is particularly worth noting how the KAW Foundation solved the problem of governance when SEB merged with Skandinaviska Banken by creating the Council of Principals, thereby building a formal link to universities and academies. A further sign pointing in the same direction is the creation in 2012 of a Scientific Advisory Board consisting of eight Nobel Laureates (KAW Scientific Board).

5. The KAW Foundation and Corporate Governance

5.1 The First Period (1917–1971)

As already mentioned, it is obvious from the very beginning of the first period (1917–1971) that the KAW Foundation had close relationships to SEB and the bank spin-off company, Investor. Upon the death of Knut Wallenberg on 1 June 1938, the KAW Foundation thus owned 10,000 shares in Investor (representing 13.9% of its capital) and 9200 SEB shares (representing 20.4% of its capital). Together, these two holdings constituted 80% of the estimated market value of the KAW assets of SEK 55 million. The additional assets were five minor holdings, bonds, and cash (Olsson Reference Olsson, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993, 68–74).

Obviously, the two major holdings had implications for corporate governance. The assets of Investor at the end of 1929 were estimated to have been around SEK 70 million, two-thirds of which were shares in industrial companies, among them SKF, with 13.4%, and ASEA, with 10.1%, of the total shares (Lindgren Reference Lindgren1994, 63–64). At the time, Marcus Wallenberg Sr. was the Chairman of Investor, while Knut held this position in SEB.

A restructuring of the holdings occurred in 1947 as SEB founded Providentia for the management of holdings that were no longer lawful for the bank. In this way, 40,000 Providentia shares were added to the KAW portfolio. Thereby, through its holdings in Investor and Providentia, the KAW Foundation took on significant indirect ownership in prominent Swedish companies: Astra, Atlas Copco, Bergvik och Ala, Ericsson, NK, SKF, Stora Kopparberg, and Svenska Tändsticksbolaget. This indirect ownership increased over time as the share of the two investment companies in the KAW portfolio increased from 32.7% in 1947 to 44.4% in 1967. The latter year the portfolio also included two significant direct holdings in Scania-Vabis (21.2%) and Ericsson (10.2%), while the share of SEB decreased from 53.9% to 37.0% and finally to 15.6% (Olsson Reference Olsson, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993, 78–79).

There can be no doubt that the Wallenberg brothers, Jacob and Marcus, took corporate governance seriously some 50 years after the creation of the KAW Foundation: in 1965 they were Chairman (Jacob) and Vice Chairman (Marcus) of the two investment companies, Investor and Providentia (Aktieägarens uppslagsbok 1965). They were also leading the boards of seven of the companies where Investor and Providentia had stakes: Astra, SKF, Stora Kopparberg, and Svenska Tändsticksbolaget (Jacob) and ASEA, Atlas Copco, and Ericsson (Marcus). In addition, the Chairman of the KAW Board 1961–1966, Nils Vult von Steyern, was also a member of the boards of Investor (1947−1966) and Atlas Copco (1948−1966).

5.2 The Second Period (1972–1995)

In the second period (1972−1995) the KAW portfolio was restructured in several ways. The most significant changes were a merger between Investor and Providentia in 1992 and the buy-out of SAAB-Scania in 1991. At the same time, the share of the holdings in the bank resulting from the merger (SE-Banken) shrank drastically because of the banking crisis, which reduced the share price for SE-Banken by 90%. As a result, the new Investor in 1992 accounted for two-thirds of the value of the KAW Foundation’s Swedish shares. At the same time, the number of different shares was cut from 22 in 1972 to eight in 1992, and the market value of the portfolio increased from SEK 421 Million to SEK 5568 million (Olsson Reference Olsson, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993, 91–97).

5.3 The Third Period (1996–2017)

In the third period (1996−2017) the market value of the KAW assets increased considerably from SEK 20,000 million to above SEK 100,000 million in 2017 (see Figure 2 above). In terms of corporate governance, it is obvious that Investor continued to play a significant role for the KAW Foundation. This became even more the case when the KAW Foundation acquired additional shares in Investor in February 2013. The close relationship between this investment company and the KAW Foundation had been manifested by an exchange of shares about a decade earlier (2001): the KAW Foundation bought shares in SAS, SKF, and Stora Enso from Investor, which in return got shares in Ericsson and SE-Banken (Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 84–85).

A further restructuring of the portfolio occurred in 2007 when the KAW shares in SKF and Stora Enso were transferred to Foundation Asset Management Sweden AB (now FAM), which had been created to manage the assets − particularly the unlisted holdings − of other Wallenberg foundations. In this way, it supplements Investor in managing the foundation assets (Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 85). At the end of 2017, the Wallenberg foundations had 100% ownership of FAM, while they owned 23.29% of the capital and had 50.1% of the votes in Investor (FAM 2017 and Investor 2017, 24).

5.4 The Centenary as a Whole

The above means that, over the years, the KAW Foundation has been deeply involved in corporate governance. In the early years, there were strong links to SEB (see Lindgren Reference Lindgren1988, 43 and Olsson Reference Olsson1986). Chairmen of the SEB board were, in order, Knut Agathon Wallenberg (1917–1938), Marcus Wallenberg Sr. (1938–1943), Johannes Hellner (1944–1946), Robert Ljunglöf (1946–1950), Jacob Wallenberg (1950–1969), and Marcus Wallenberg (1969–1971), all men that were also on the KAW Board (see above). Likewise, the Wallenberg family members − Marcus Sr., Jacob and Marcus, Peter, and Jacob – have chaired Investor with the three exceptions of 1916−1925 (Otto Printzsköld), 1943−1945 (Johannes Hellner), and 1997−2002 (Percy Barnevik) (Fagerfjäll Reference Fagerfjäll2016, 248–249). Currently, there is a division of labour between the two brothers Jacob and Peter Jr. and their cousin Marcus. Jacob is the Chairman of Investor as of 2005, Marcus is the Chairman of SE-Banken as of 2004 and FAM as of 2013, while Peter Jr. is the Chairman of the KAW Foundation as of 2015, where Jacob and Marcus are board members. Marcus is also a board member of Investor, and three of the other Investor board members were, in 2017, Chairmen of sphere companies in the portfolio: Atlas Copco (Hans Stråberg), Husqvarna (Tom Johnstone), and Mölnlycke (Gunnar Brock) (websites of the companies). In the 1960s, such arrangements were questioned, but they are today more generally accepted as active national ownership is embraced in a world of aggressive international capitalism.

6. The KAW Foundation and Resource Allocation

6.1 The First Period (1917–1971)

During the first decade, the grants were few, and it was not until 1927 that the annual number of grants exceeded ten. However, at the end of the period in 1971, the KAW Foundation had provided almost 1500 grants. Together they totalled SEK 178 million with a maximum of SEK 15 million in 1967. Grants were basically directed towards two purposes: investments in institutions and support of individual top scientists.

In terms of institutions, the very first grant in 1918 of SEK 1 million was provided for the building of the Stockholm City Library. Another million grant in the first decade was the one in 1923 to the Stockholm School of Economics, an institution that Knut Wallenberg had initiated through a donation in 1903. A third large early grant was a half-million grant to a housewifery school in Uppsala in 1920, a project which appears to be the only one where Knut’s wife Alice was directly involved.

Further institutional grants appeared after that Knut Wallenberg, in 1927, had proactively approached the Director General of the National Board of Agriculture in order to receive input to the resource allocation of the KAW Foundation. The response was a suggestion to start one institute for genetic research regarding domestic animals, and another regarding freshwater fishing. Both proposals prompted a number of grants for many years (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993b, 161–178). These grants are just two examples of recurrent grantees.

Other institutional grants included the acquisition of a building for the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (1927); the construction of a student union building (1933) and a library at Stockholm University College (1939); an observatory for the Royal Academy of Sciences (1928−1929) and support to schools in Sigtuna and Stockholm (from 1930) (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993b, 178–181 and 206–212). Likewise, the KAW Foundation supported the creation of cultural institutions: the National Maritime Museum (from 1931), the National Museum of Technology (1933), and the Swedish Institute in Rome (1937−1938) (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993b, 192–206). Moreover, the KAW Foundation supported existing museums such as the Army Museum (1937) and the Nordic Museum (1936) as well as the salvaging of the man-of-war Vasa (1959), nowadays a popular tourist attraction. In the 1960s, a number of Wallenberg laboratories were created, first at Uppsala University (1963, 1965 and 1967), then at Lund University and Stockholm University (1968−1969).

In terms of the ‘support to prominent scientists’, these began in the late 1920s. The first of these grantees was Hans von Euler, the 1929 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, who up to 1950 received some 15 grants (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993b, 157–161). Other Laureates that received grants for a number of years from the KAW Foundation were Manne Siegbahn (Physics Laureate in 1924), Theodor (The) Svedberg (Chemistry in 1926), George de Hevesy (Chemistry in 1943), Arne Tiselius (Chemistry in 1948), Hugo Theorell (Physiology or Medicine in 1955) and Ragnar Granit (Physiology or Medicine in 1967). However, other distinguished scientists received grants from the Foundation: genetics professors Torbjörn Caspersson at the Karolinska Institute and Åke Gustafsson at Lund University as well as the Gothenburg professors of Oceanography Hans Pettersson and of Astronomy Olof Rydbeck.

From the mid-1940s, grants became larger, with an increasing orientation towards natural sciences and medicine. During the leadership of Axel Wallenberg (1946–1961) there was a particular tendency to support medical research, especially at the Karolinska Institute. From 1946 to 1959, its share of the annual total grants was always above 12%, for eight years above 25%, and in 1953 even 50% (Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993b, 231 and 236). At the same time, the Swedish landscape for research funding had changed during and after the war through the creation of the national research councils, which put the KAW Foundation in a new situation (see further Nybom Reference Nybom1997; Engwall and Nybom Reference Engwall, Nybom, Whitley and Gläser2007).

6.2 The Second Period (1972–1995)

During the 24 years of the second period (1972–1995) the number of grants multiplied to almost 1900, a total sum of SEK 2883 million and SEK 353 million as the 1995 figure (see again Figure 3). The information provided in Hoppe (Reference Hoppe, Hoppe, Nylander and Olsson1993b, 216–286) and the annual reports 1975–1995 show that the KAW Foundation continued its support to institutions, an orientation that became even more significant in the 1980s and 1990s. Stockholm University was well furnished with considerable grants for its Aula Magna (1993) and a genetics laboratory (1990). Large grants went also to Uppsala University and Chalmers University of Technology for a centre for materials sciences (1991) and a microelectronic centre (1995), respectively. Furthermore, the KAW Foundation funded a conference centre at the University of Gothenburg (1987) as well as Wallenberg Laboratories at the University of Gothenburg (1980), Malmö Academic Hospital (1991), and Lund University (1993). The Foundation even provided a grant to the Scandinavian School in Brussels for the purchase of a building. In addition, various academic institutions, schools, and museums obtained a number of smaller grants (SEK 10 to 20 million). Some of these were additional support to earlier grantees.

A second group of grants in the second period comprised those for expensive research equipment. To a considerable extent, these grants were a consequence of earlier grants for laboratories. As the buildings were constructed, the researchers needed equipment to pursue their research. Grants were given to the universities in Gothenburg (1994), Lund (1992, 1993, 1994), and Uppsala (1995), the Royal Institute of Technology (1995), and the Karolinska Institute (1993). Equipment in high demand included electron microscopes, accelerators, laser equipment, Position Emission Tomography (PET) cameras, and computers (among the latter, three grants of SEK 10 million each to Linköping University for a supercomputer in 1985−1987). Two other grants of special interest in relation the earlier support by the KAW Foundation to astronomy are those for the satellites Freja (1988) and Odin (1994) as well as those to the Institute for Space Physics (1975, 1984, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1994 and 1995) and Chalmers for their space laboratory (1973, 1991 and 1993).

The last year of the second period (1995) also saw the start of a new kind of grant that aimed at supporting doctoral students and senior researchers. These grants were a development of the stipend programmes that the foundation had been pursuing over the years. Such special programmes were running for researchers in law, the humanities, and theology. In addition, university vice chancellors obtained resources to support the international contacts of their faculty members.

Overall, in the second period, the KAW Foundation directed its resources mainly towards the construction of university laboratories and the provision of appurtenant equipment. In this way, the Foundation no doubt played a significant role in the redirection of Swedish research towards areas such as materials science, molecular biology, and genetics. It also played an important role for the development of private schools and continued its support for museums. At the end of the period, the Foundation started a reorientation towards funding individual researchers. A strong contributing factor was the transfer in 1993 of most of the university buildings in Sweden to the state-owned and profit-driven company Akademiska Hus.

6.3 The Third Period (1996–2017)

The annual reports for the third period (1996–2017) show that these years have represented the true take-off for the KAW Foundation in terms of its allocation of grants, which increased almost fourfold from SEK 453 million in 1996 to SEK 1784 million in 2017 (see again Figure 3). At the same time, the last period saw not only a change in the granting capacity but also a change in the direction started at the end of the second period. The previously prominent types of grants to institutions were now reduced in favour of grants to specific research programmes and to research positions for outstanding scholars.

Among the few grants for institutions, the largest part (in total SEK 205 million) went to the private Stockholm School of Economics for reconstruction of its building (1998 and 2007). Stockholm University received additional funding for its auditorium (1996), while the University of Gothenburg was granted funding for a Science Centre (1997), Chalmers University of Technology for a micro technology centre (2001), the Royal Institute of Technology for an IT centre (2001), and the Karolinska Institute for a cancer research centre (1996). In the late 1990s, student facilities were funded at several universities.

The funding of expensive equipment continued in the last period. Such grants above SEK 100 million were provided to Lund University for the accelerator MAX IV (2010), a group of universities jointly for nanotechnology equipment (2004), and Linköping University for an unmanned aircraft (1999). A particularly noteworthy project was the high-speed link to Stanford University within the programme ‘The Global University’ (1996), followed by grants for cooperation between Swedish universities and Stanford University in 1999, 2007 and 2010, totalling SEK 270 million. In addition, in 2015 the Foundation allocated SEK 64.5 million for postdoc stipends to Stanford University and the creation of a Bienenstock–Wallenberg Chair at Stanford.

However, the largest share of the grants now went to specific research programmes. Here, the Swedish Human Proteome Resource at the Royal Institute of Technology garnered particularly strong support, with a number of grants from 2002 and onwards. Another strong initiative was a programme regarding function genomics, for which the KAW Foundation created two consortia, one consisting of the universities in Uppsala, Stockholm, Umeå, and Linköping, and the other with the universities in Lund and Gothenburg as members. They were funded for five years (2000–2004), and both received more than SEK 300 million in total. Furthermore, after a first smaller grant to the Royal Institute of Technology in 1997, the KAW Foundation launched a large programme regarding wood science. In addition, a number of other programmes were funded, such as the SEK 100 million initiatives in regenerative medicine (2009 at the Karolinska Institute), Swedish Brain Power (2009 at the Karolinska Institute), Protein Research (2015 at the Royal Institute of Technology) and the Swedish CArdioPulmonary bioimage Study (2015, at Uppsala University) as well as a number of research projects with support below SEK 100 million.

A fourth type of grants were those for research positions after the turn of the century. In 2000–2008, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Royal Academy of Antiquities, Letter and History received such grants and were later given the responsibility to select holders of research positions for promising young scholars (Wallenberg Academy Fellows). Later, in 2008, the Foundation launched a Wallenberg Scholar programme for excellent researchers and in 2015 a Wallenberg Clinical Scholars programme. As before, the KAW Foundation ran a number of stipend programmes, which added up to hundreds of millions.

6.4 The Centenary as a Whole

In terms of the allocation of grants, the first centenary of the KAW Foundation has implied a strong growth in its granting capacity and thereby its influence on resource allocation. After a slow start with relatively limited allocations until the 1980s, the foundation has experienced a spectacular granting capacity, ending the first century with total grants of SEK 1784 million in 2017. At the same time, the foundation has also made a reorientation in its allocation strategies. It started out in the first period with a strong focus on supporting institutions but eventually added support to prominent scientists, particularly in the natural sciences and medicine. The support to institutions, in turn, created a need for expensive equipment, which the KAW Foundation then came to finance in the second period, during which they also provided grants to individual scholars. In the third period, there was a reduction in the support for institutions in favour of specific research programmes and the support to outstanding scholars. At the centenary of the Foundation, it is thus evident that a reorientation had occurred. In the words of the jubilee publication: ‘the previous emphasis on large-scale facilities and expensive equipment has been toned down in favour of comprehensive investments with national significance.’ (Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Hedenqvist and Sundström2017, 87). A contributing factor for this has been the creation of the profit-oriented state-owned Akademiska Hus. Another change in the environment of the KAW Foundation has been the development of other significant actors funding Swedish research, such as the Swedish Research Council and the Foundation for Strategic Research with annual granting capacities in 2017 of SEK 5845 million and SEK 935 million, respectively (Vetenskapsrådet 2017 and Stiftelsen för Strategisk Forskning 2017).

7. Conclusions

7.1 The Governance of Foundations

Although the KAW Foundation is just one case, it demonstrates some general features of the governance of foundations. First, in relation to the first research question (‘What are the characteristics of the governance of foundations?’) the case points to the difficulties regulators face in finding adequate rules for foundations. Although a Companies Act had been passed in Sweden as early as 1848 and several efforts had been made since the 1850s to regulate foundations, it was not until in 1929 that an act for foundations was finally passed. In addition, as this act was considered ripe for modification, it again took considerable time to formulate a new act that could pass through the Parliament. At the same time, the case also clearly demonstrates how Swedish politicians have had an interest in governing foundations. The introduction of state representatives in the major foundations during the period 1973−1995 is the most obvious evidence. However, for most of the time the monitoring has been delegated to the county governor and to tax authorities, who have to ensure that the law and the statutes are followed. Therefore, the fulfilment of the purpose of a foundation is particularly examined. In this way, regulators act as representatives of the donors.

In addition to regulators, foundation boards play an important role in pursuit of the intention of the donors. Here the KAW Foundation case demonstrates how a foundation may create owner-like arrangement through the selection of board members. Through the appointment to the board of family members and sphere executives, many of them with long tenures, the KAW Foundation has had owner-like arrangements. These have been combined – long before they were prescribed in corporate governance codes – with the nomination of distinguished independent board members, first officials and then academics. This appears as a reflection of a wish to create legitimacy in relation to regulators as well as to the communities of prospective grantees.

We can thus conclude that regulators have found it more difficult to formulate adequate rules for foundations than for corporations. They also have to rely on arm’s-length monitoring of rule and statute compliance. For foundations themselves, the KAW Foundation case indicates that successful foundation governance is characterized by (1) rule compliance, (2) loyalty to the donors, and (3) legitimacy among prospective grantees.

7.2 Governance by Foundations

Then, in relation to the governance by foundations and the second research question (‘What role do foundations play for corporate governance?’) the KAW Foundation case clearly demonstrates how a major foundation can play a significant role in corporate governance. Through its holdings, the foundation has had a strategic influence in major Swedish corporations through board representation, particularly as chairs. Especially important have been the joint membership of the KAW Foundation board and the boards of the bank SEB and the investment company, Investor. This has been possible through heavy weighting in the asset portfolio of these companies and other sphere companies. Over time, the portfolio has also been characterized by considerable stability. Most of the holdings have been in the portfolio for a long time, a probable effect of the lack of owners and customers. In contrast to corporations, a foundation such as the KAW Foundation thus has no outside pressure to deliver short-term performance. Foundations can therefore have a long-term perspective, which reduces transaction costs. The long-term ownership has also had the advantage of better knowledge about, and understanding of, the corporations in the portfolio. The latter may help in corporate governance to lead companies in the right direction. Together, the above means that we can conclude that the larger, the more concentrated, and the more long-term the asset portfolio, the more significant role a foundation can play in corporate governance.

Then, in terms of the second aspect of the governance by foundations formulated as the third research question (‘What role do foundations play for resource allocation?’) the KAW Foundation case clearly shows how a major foundation has had a significant influence on priorities in society. First, through grants for institutions and equipment in the first and second period, it has been important for investments in infrastructure. Second, from the 1940s and onwards, research has been supported through grants to individual prominent scholars as well as to large research programmes. Together, these grants have had a considerable impact on the Swedish research landscape, an impact that has increased over time because of a growing granting capacity. This in turn has contributed to the legitimacy of the KAW Foundation. As already pointed out, the appointment of board members from the community of prospective grantees has been likewise important for the legitimacy of the foundation. Obviously, this arrangement has also been essential for the identification of possible projects. A further approach for the latter has been the creation of a network of prominent scientists and university leaders linked to the foundation. In this way, the KAW Foundation has been able to make grant decisions in dialogue with significant actors. This means that we can conclude that the more successful asset management and the more careful project selection are, the more significant role a foundation can play in resource allocation.

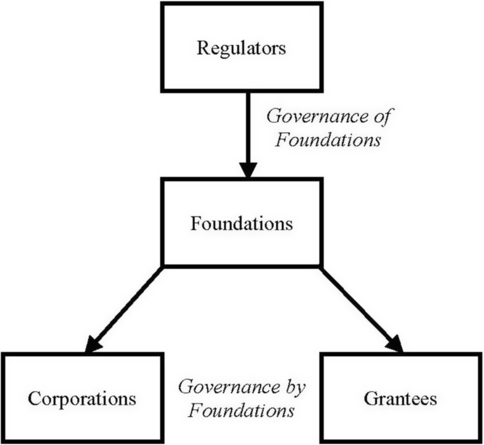

In addition to the above, the KAW Foundation case has pointed to more complicated reciprocal relationships between foundations, corporations, and grantees than those discussed earlier in the paper (see Figure 7). Foundations can thus be dependent on corporations for their own governance, as the merger between SEB and Skandinaviska Banken reveals (left dotted arrow in Figure 7). At the same time, they are in a reciprocal relationship with prospective grantees through their project proposals (right dotted arrow). Moreover, we have seen the reciprocal influence through the election of representatives of corporations and grantees (first officials and later academics) to the board of the foundation. Finally, it is important to point to the financial flow that foundations receive from corporations (left broken arrow), which constitutes the basis for their allocations to beneficiaries (right broken arrow). Professional corporate governance is therefore in the interest of grantees, since the higher the profits in the portfolio companies, the greater the granting capacity of foundations.

Figure 7. The reciprocal relationship between foundations, corporations and grantees.

Obviously, the KAW Foundation is only one case. Further studies in the same spirit in other contexts in terms of time and space would therefore be highly appropriate. In this way, our understanding of foundations under various condition in modern society could be further advanced. This is particularly important, since philanthropic foundations are tending to grow in number and size, thereby playing increasingly significant roles in society.

About the Author

Lars Engwall is Professor Emeritus of Management at Uppsala University, Sweden. His research has been directed towards studies of organizations. Among his recent publications are Bibliometrics (ed., 2014, with Wim Blockmans and Denis Weaire, Portland Press), From Books to MOOCs? (ed., 2016, with Erik De Corte and Ulrich Teichler, Portland Press), Defining Management (2016 with Matthias Kipping and Behlül Üsdiken, Routledge), Corporate Governance in Action (ed., 2018, Routledge) and Missions of Universities (ed., 2020, Springer). He is an elected member of a number of learned societies, among them Academia Europaea, and has received honorary degrees from Åbo Akademi University and Stockholm School of Economics.