Introduction

Canada’s population of older adults is increasing. In 2010, there were approximately 5.8 million seniors, representing 16.1 per cent of the population. By 2036, this number is projected to reach over 10 million (Statistics Canada, 2015). Older adults are at higher risk for transition to residential care if they have (a) limitations in personal care abilities, (b) multiple chronic health conditions, and (c) lack of nearby family or friends who are willing and able to provide support (Guberman et al., Reference Guberman, Lavoie, Fournier, Grenier, Gagnon, Belleau and Vézina2006). Advancing age is also a strong predictor of institutionalization (Luppa et al., Reference Luppa, Luck, Weyerer, König, Brähler and Riedel-Heller2010). People living in institutions today are older, have multiple co-morbidities, and are more dependent on others than their counterparts were two decades ago (Han, Gill, Jones, & Allore, Reference Han, Gill, Jones and Allore2016). In British Columbia, there are about 820,000 seniors, and 30,000 of them (4%) live in residential care (Office of the Seniors Advocate British Columbia, 2016).

A move to residential care, with its rules and routines, where one is dependent on others for care and support, can have a major impact on a person’s ability to retain a sense of identity and express their individuality (Grenade & Boldy, Reference Grenade and Boldy2008). The loss of opportunity for meaningful interaction with family members, friends, community, and social activities can lead to social isolation and a loss of a sense of self (Drageset, Kirkevold, & Espehaug, Reference Drageset, Kirkevold and Espehaug2011). Several studies have reported a link between having strong supportive social networks and improved health outcomes in later life whereas belonging to a small and/or unsupportive network increases the risk of poor physical and mental health (e.g., Bosworth & Warner Schaie, 1997; Seeman, Reference Seeman1999). Residential care also offers fewer possibilities for engaging in personalized meaningful activity compared to a similar population in community (Haugan, Reference Haugan2014). In the later stages of life, having a sense of meaning and purpose in life confers a stronger ability to cope with stressful life experiences, illness, loneliness, despair, and the fear of death (Krause, Reference Krause2007; Van Orden, Bamonti, King, & Duberstein, Reference Van Orden, Bamonti, King and Duberstein2012).

To address these concerns, residential care facilities have offered programs centred on the arts although such efforts are poorly resourced and involve arts and crafts activities instead of professionally oriented art education (Katz, Holland, Peace, & Taylor, Reference Katz, Holland, Peace and Taylor2011; Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Mortenson, Stone, Suto, Timonen and Rozanova2015). Yet there is increasing recognition that professionally taught arts programs can offer significant benefits for reducing social isolation, increasing self-esteem, and providing participants with a sense of empowerment (Camic, Reference Camic2008; Roos & Malan, Reference Roos and Malan2012). In a study of a professionally taught arts program in a long-term care facility, Wilkinson, MacLeod, Skinner, and Reid (Reference Wilkinson, MacLeod, Skinner and Reid2013) found an improvement in participant well-being, creative expression, and sense of meaning. This finding emerged from an analysis of field notes, weekly logs kept by program volunteers, transcripts of volunteer debriefing meetings, and program evaluation questionnaires which were completed by both volunteers and participants.

Unfortunately, there is limited research documenting the benefits of such programs in residential care. To address this gap in knowledge, this qualitative study explored the nature and impact of a creative visual art-making program in a long-term residential care facility for older residents in Victoria, British Columbia.

Literature Review

In North America, individuals in residential care are generally characterized by advanced age, physical impairment, and cognitive decline, all of which require 24-hour skilled nursing care (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Daly, Armstrong, Szebehely, Armstrong and Lafrance2012). All facilities are licensed and regulated by provincial governments but ownership can be private and for profit, nonprofit, or by a provincial or territorial government (Berta, Laporte, Zarnett, Valdmanis, & Anderson, Reference Berta, Laporte, Zarnett, Valdmanis and Anderson2006). Residential care facilities also provide complex care to improve the functional ability and quality of life of adult residents with disability and facilitate their transition to a reduced level of care. Individuals who receive this type of care may be younger than those in long-term residential care and have chronic physical functional disability, but no cognitive impairment (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee, Armstrong, Amaratunga, Bernier, Grant, Pederson and Wilson2009).

Admission into residential care has a significant impact on adults: Many report less meaning in their lives compared to their community-dwelling peers (Bondevik & Skogstad, Reference Bondevik and Skogstad2000) as well as a diminished sense of purpose which affects their ability to manage stress and the limitations of their disability (Dwyer, Nordenfelt, & Ternestedt, Reference Dwyer, Nordenfelt and Ternestedt2008; Haugan, Reference Haugan2014). These adults also have limited social opportunities beyond their daily care activities, interactions with staff, and relationships with other residents (Cipriani, Faig, Ayrer, Brown, & Johnson, Reference Cipriani, Faig, Ayrer, Brown and Johnson2006). These circumstances can heighten feelings of loneliness and make it more difficult for adults to develop meaningful friendships while in care (Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Mortenson, Stone, Suto, Timonen and Rozanova2015).

In addressing these concerns, residential care facilities provide a variety of therapeutic programs designed to maintain or enhance psychosocial and functional capacity (Katz, Reference Katz2000). Most of these programs are task-oriented, organized with minimal or no input from residents, and focus primarily on distracting participants rather than encouraging them to meaningfully interact with one another (Timonen & O’Dwyer, 2009). Yet programs designed around the arts have been shown to reduce social isolation; increase self-esteem; foster a sense of empowerment, meaning, and purpose; and improve quality of life (Camic, Reference Camic2008; Flood & Phillips, Reference Flood and Phillips2007; Greer, Fleuriet, & Cantu, Reference Greer, Fleuriet and Cantu2012; Macnaughton, White, & Stacy, Reference Macnaughton, White and Stacy2005; Roos & Malan, Reference Roos and Malan2012). Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Perlstein, Chapline, Kelly, Firth and Simmens2006) studied the impact of professionally taught cultural arts programs on the physical and mental health of more than 300 older adults above the age of 65. The study found that those participating in the arts programs experienced a higher quality of life and better health compared with their non-participating peers.

Other studies identified similarly positive outcomes in older adults living in the community and in residential care settings. For example, Greaves and Farbus (Reference Greaves and Farbus2006) found that creative arts (i.e., painting, printmaking, creative writing, reminiscence/living history, pottery, and singing) promoted greater meaning and improved psychological well-being in older adults living in the community. Fraser, Bungay, and Munn-Giddings (Reference Fraser, Bungay and Munn-Giddings2014) showed that participatory visual arts (i.e., clay modelling and painting) resulted in increased levels of engagement for older adults in residential care. Wilkinson et al. (Reference Wilkinson, MacLeod, Skinner and Reid2013) found an expressive arts program gave isolated seniors in rural communities and institutional settings an opportunity to “learn about the aging process, open doors to new perceptions and increased confidence” (p. 234).

Participative arts for persons with dementia have been shown to improve residents’ health and quality of life (Tesch & Hansen, Reference Tesch and Hansen2013; Young, Camic, & Tischler, Reference Young, Camic and Tischler2016). In particular, Graham and Fabricius (Reference Graham and Fabricius2017a) examined the benefits of introducing a “Winter Wonderland” space for residents, staff, and visitors to explore in a residential care facility. The residents created installation components such as snowflakes and garlands hanging from tree branches during art classes led by staff artists. The intent was to engage residents in building an indoor winter experience. A thematic analysis of guestbook comments revealed that visiting the installation was a pleasurable experience for residents, staff, and visitors. Visitors also remarked how the installation often evoked pleasant memories of previous winter activities among the residents. Graham and Fabricius (Reference Graham and Fabricius2017b) also reported on a participative arts mural project on two secure residential care dementia units. The project involved designing and painting murals on each of the care units’ main doors to lessen residents’ exit-seeking behaviour, reduce anxiety, and provide a more home-like environment. Staff from the two units observed a decrease in exit-seeking behaviour after the murals were created.

Arts interventions, particularly those with a participative component, can thus contribute to well-being, increase motivation to remain active, improve self-esteem and physical health, and allow older adults with disability to express themselves creatively, which can promote a sense of identity as artists (Malchiodi, Reference Malchiodi1999; Stallings, Reference Stallings2010). However, demonstrating the benefits of arts programs has been fraught with challenges due in part to the lack of agreement on the types of programs to be studied and how outcomes should be measured (Leckey, Reference Leckey2011; Roe, Reference Roe2014). Against this backdrop, Fraser et al. (Reference Fraser, Bungay and Munn-Giddings2014) have argued for moving beyond narrowly framing the arts as therapeutic intervention in order to gain a deeper understanding of how programs can foster a sense of meaning and purpose among older adults in care. Accordingly, this study sought to examine the experiences of a group of adults in residential care who participated in a creative visual arts program. Our study was guided by two research questions: (a) What is the nature of resident engagement in the creative visual arts program? (b) How do residents view and understand the impact of the program on their well-being and their sense of purpose and meaning?

Theoretical Framework

In investigating the search for meaning among adults in residential care, our study relied on the theory of gerotranscendence. Developed by sociologist Lars Tornstam (Reference Tornstam2011), the theory posits that gerotranscendence is marked by a “a shift in metaperspective, from a materialistic and rational view of the world to a more cosmic and transcendent one, normally accompanied by an increase in life satisfaction” (p. 166). Influenced by classical psychoanalytical theorists such as Carl Jung and Erik H. Erikson, Tornstam (1996) suggested that, as individuals age, they change the way in which they view themselves and the world, which can lead to new understandings of one’s self and of others. He further argued that gerotranscendence is a natural developmental process which reflects continued growth and creative potential in later life (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005). As Tornstam (Reference Tornstam2011) argued, the process of gerotranscendence is a “positive development involving increased life satisfaction in the context of a developmental pattern typically including a redefinition of the self and relations to other people, as well as a new way of understanding existential questions” (p. 168). In analysing the interviews of 50 older adults, Tornstam (Reference Tornstam1997, Reference Tornstam2005) found that they experienced significant changes in three levels of development: the cosmic level, the level of self, and the level of social and individual relations.

At the cosmic level, older adults experience broad existential changes whereby the perception of time and space shifts. This shift leads to the development of new connections between the past and present, an acceptance of the uncertainty and mystery of life, and a greater appreciation of the subtler experiences of life. Tornstam (Reference Tornstam2011) argued that the distance between now and then is transcended at the cosmic level, which allows the person to reinterpret and reconcile with previous situations from childhood or later periods in life. Additionally, individuals can feel increasingly integrated within the flow of generations and harbour a sense of being part of the continuation of life. A further characteristic of this level is an increased interest in past and future generations, decreased fear of death, and an overall feeling of communion with the universe and cosmic awareness.

The second level of development involves changes in understanding the present self and the older self in retrospect. This results in the discovery of hidden aspects of the self, the loss of self-centredness, a shift from egoism to altruism, the rediscovery of the child within, and ego-integrity with recognition that one’s life is meaningful and its various aspects interconnected. According to the theory of gerotranscendence, people also achieve a level of maturity and wisdom at the second level, in part because of an increased desire for inner peace, meditation, and contemplative solitude. Another feature of this level is a greater satisfaction with the body and acceptance of one’s appearance.

Finally, changes occur in social and individual relationships whereby older adults become more selective in their choice of social relations and devote less time to superfluous socializing with others. They seek time for solitude and reflection and develop a desire to give up role-playing. They also realize the limitations of wealth and the freedom of asceticism and see value in withholding judgment and advice. On this later point, older adults reaching gerotranscendence come to understand that answers are seldom easy in reality, which leads to a reluctance to superficially separate right from wrong. Older adults are also more selective in their choice of activities and develop “a new skill to transcend needless conventions, norms and rules, which earlier in life had curtailed freedom to express the self” (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2011, p. 173).

The usefulness of gerotranscendence lies with its holistic and positive portrayal of aging as a process of self-discovery and potential fulfillment although this process may be impacted by the challenges people encounter in older life, including disability, social isolation, and the lack of opportunity to engage in activities that facilitate meaningful reflective engagement. Gerotranscendence offers a way to understand participants’ experiences with the arts as a reflective process and a repositioning of one’s identity in the context of residential care.

In later writings, Tornstam (Reference Tornstam2011) drew attention to the ways gerotranscendent development may be obstructed by the medicalized nature of residential care. As Wadensten and Carlsson (Reference Wadensten and Carlsson2003) argued, staff members need to be made aware of gerotranscendence as a developmental process and to recognize its signs as a normal aspect of aging. Further, places of care need to address the institutional barriers that hinder gerotranscendence and promote active participation in the arts so that older adults can continue their personal development despite the task-focused care routines inherent in the daily life of those in residential care.

Methodology

The study relied on the methodology of narrative inquiry to gain insight into the experiences of participants who engaged in a creative visual arts program in a residential care facility. A key tenet of narrative inquiry “is that people live storied lives and that studying the experiences of life offers the possibility for its reconstruction, thus opening a new avenue for living” (Manakil-Rankin, Reference Manakil-Rankin2016, p. 62). The researcher’s role in narrative inquiry “is to interpret the stories in order to analyze the underlying narrative that the storytellers may not be able to give voice to themselves” (Riley and Hawe, Reference Riley and Hawe2005, p. 227). The researcher can complement insights from interviews with other methods of data collection, including observation, interviews, and document analysis, to understand the complex particularities of human experience (Clandinin & Connelly, Reference Clandinin and Connelly2000).

Narrative inquiry is well suited to researching gerotranscendence because it can capture human experience as it unfolds along the three-dimensional inquiry space of temporality, personal/social conditions, and place (Clandinin & Connelly, Reference Clandinin and Connelly2000). The first dimension reflects the temporal links within the participant’s storyline, including links between current and past life events. The second dimension represents how personal experiences are shaped by social conditions within the environment. The third dimension of place pertains to the current physical context of the participants’ experiences such as their place of care or the studio where they create art.

Ethics approval was granted by the Joint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Victoria and Island Health. The study was conducted at the Argyll Arts Program (AAP) located in a facility in Victoria, British Columbia, which provides both long-term residential care and specialized complex care to older residents and younger adults with complex functional challenges. With support from the facility, a community foundation, and a local community arts council, the AAP was developed by a full-time recreational therapist to offer professionally taught arts instruction in weekly 90-minute classes. The program supports participants in sharing their voices through arts while fostering community engagement and a sense of belonging. Participants in AAP learn a variety of techniques, including art collage, watercolour painting, ceramics, and digital photographs; and participants travel monthly to a community recreation centre to attend art classes. AAP participants exhibit their artwork once a year in an art gallery; this public event is one of the highlights of the program.

Recruitment and Sampling

The first author and principal investigator (PI) first met with AAP staff to inform them of the purpose of the study and provide each of them a letter of invitation and a consent form. The PI later met with residents participating in the AAP at the start of their first class to explain the study and provide a letter of invitation. Residents later received a consent form from the social worker on their care unit. Staff and residents were given one week to decide if they wished to participate in the study. Ten out of 11 residents and three staff agreed to participate.

All participating residents with the AAP were of Anglo-European origin. There was one male and nine female residents between 56 and 86 years of age with an average age of 68 years. Eight residents had a high school diploma, two a post-secondary degree, and one had elementary school education. The majority of residents were widowed and had family members living outside of Victoria. Most residents had relocated from a home they had lived in for many years prior to entering the facility.

All residents had mobility limitations and used either a manual or powered wheelchair, and most had limited arm and hand functionality associated with brain injury and/or a chronic illness. They required assistance with three or more activities of daily living such as dressing, personal hygiene, mobility, monitoring of medication use, and other routine activities.

The AAP staff sample consisted of two activity workers and one facilitator. The workers were all female, Canadian born, Anglo-European, and worked full time at the residential care facility. The activity workers helped residents travel from their room to the location of the AAP and provided assistance in getting to the bus when residents attended classes at a local recreation centre. They also provided the tools that residents needed to hold brushes and other supplies for the art classes. The AAP also used the services of two volunteers who assisted primarily with instrumental tasks such as preparing the art supplies and cleaning up. They were not invited to participate in the study because they were new to the program and unfamiliar with the AAP and the participants.

Data Collection

The PI conducted in-depth, face-to-face interviews with residents and staff as well as field observations. The interviews were loosely structured, approximately one hour in length, and consisted of open-ended questions to allow participants to elaborate and share their personal stories. The interviews took place in a room close to where the AAP was held which offered a safe, comfortable, and private environment for the participants. The PI conducted the observation sessions in the AAP room, at the community arts centre, and at the public art exhibit. Each observation session lasted approximately fifty minutes. The observation field notes followed a chronological format in documenting activities and interactions occurring during the artwork sessions and art exhibit. Whenever possible, the researcher included direct quotes from residents and staff. The PI also reviewed program documents including the AAP Facebook page, the health authority’s newsletters, promotional material for the community art exhibit, and two videos on the exhibit from a local TV channel.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded with the permission of the participants and transcribed verbatim. The handwritten field notes were typed immediately after the AAP sessions and arts exhibit. The names of the participants, along with any identifying characteristics or details, were removed from the data to ensure anonymity.

Narrative inquiry methods were used to analyse the data (Riessman, Reference Riessman2008). Concurrently with observing the AAP sessions and interviewing participants, the PI listened and re-listened to audio-recorded interviews, read and re-read field notes and transcripts, and developed initial interpretations of the data. Narrative inquiry requires the researcher to continuously reflect on and keep track of the multiple levels of the participants’ experiences in relation to the research aims. This reflective process guided the analysis as the PI worked to understand the meaning of the participants’ stories in relation to her own struggle and insight as an artist.

Interviews and field notes were thematically organized following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guidelines to establish the “relationship between codes, between themes, and between different levels of themes” (p. 89). The interviews with the AAP participants and staff, and observations of the art classes were coded individually to allow for the analysis of categories within each distinctive data source (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The use of the mind-mapping software Coggle (https://coggle.it, Cambridge, England) facilitated this phase of analysis by allowing the researcher to visually organize the complex relationships between the themes in a diagram and identify the “relationship between codes, between themes, and between different levels of themes” (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006 p. 89). Documents and news reports were analysed afterwards for contextual information about the AAP, its aims, and the manner in which participants publicly represented their experiences.

The diverse sources of data from interviews, observations, and documents from the AAP program enhanced the validity of the findings by allowing a full understanding of the complexity of participant involvement and instructional practices within the AAP (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Reference Cohen, Manion and Morrison2000). We then evaluated the findings from the analysis in the context of the study’s overall purpose and the guiding research questions which focused on understanding the nature of resident engagement in the creative visual arts program and on how residents viewed and understood the program’s impact on their well-being and sense of purpose and meaning.

Findings

Themes derived from the analysis of resident and staff narratives, field notes, and documents are organized in the following three sections: (a) social relationships within the AAP; (b) meaningfulness and self-exploration; and (c) engagement with the community.

Social Relationships within the AAP

All 10 residents found the AAP appealing, in part, because the program offered them the opportunity to interact and share their respective passion for the art. Residents saw this as an important aspect of the program given the few contacts they had with friends and family members after entering into care. One resident (R10), who had lived in the facility for nearly two years, talked about gradually losing touch with friends in the community. She said, “When I was in my home I used to have a party for everybody for Christmas, with people I wanted to invite. But when I moved here I haven’t seen them since … They don’t like to come here, I guess.” She thought her friends felt uncomfortable in the hospital-like environment of the facility. To compensate, she went to coffee shops and the shopping mall more frequently, but found these activities offered superficial social contact when compared to her previous life in the community. Other residents shared similar stories – they saw their care environment as a barrier to maintaining meaningful relationships with the people they knew in the community. The majority of residents said they had resigned themselves to having fewer meaningful social interactions. Two recently admitted residents felt less socially isolated as they saw their care as rehabilitative and, unlike other residents, hoped to leave the facility soon. As one resident (R8) said, “I believe that I need to keep myself busy and eventually … I’ll get back to home once I’m better.”

All three AAP staff recognized that feelings of loneliness and social isolation were prominent among the care facility’s longer-term residents. One staff member added that the AAP sought to address these concerns by providing residents the opportunity to engage with each other and with community members through the yearly art exhibit. As one staffer (S3) said, “They still exist and are capable of producing material … They are still learning … They are not just here, doing nothing.”

The AAP allowed for deeper interactions to occur among residents. As one resident (R6) reflected, “There is some exchange about family, things that we have done, the reasons we are here. In the arts program, there are things that we want to do, so we talk.” Another resident (R9) stated, “I think the environment changes when the group comes together, when everybody is working together. You just don’t have this another time.” Resident (R3) added, “In the arts program you’re sitting beside somebody else. Then you have a chance to talk. You know they are doing well, they are quite happy.” Staff member (S3) commented on the meaningfulness of these interactions: “They are very supportive of each other, and they are encouraging, and I think this is more about a meaningful interaction than small talk.” Another staff member (S1) similarly remarked, “I’ve never seen them interacting before the program … only after they started the arts program.” She went on to comment that the AAP “opens them up and they’re also willing to share with us their history.”

Meaningfulness and Self-Exploration

All residents spoke of the AAP as a space which facilitated an exploration of their own unique need to express themselves artistically. Most residents had previous involvement with the arts before their admission into residential care and reminisced of doing artwork with a range of media like acrylic or watercolour paint, sewing, singing, and even woodworking. A few residents without previous artistic experience spoke of wanting to explore their artistic abilities in ways they did not in their younger years. As resident (R9) said, “I was always interested in arts. But I never allowed myself to practice until I moved here. And I did my first painting when I was 61.”

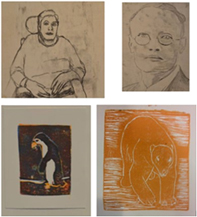

During the study, the AAP coordinator provided residents with professional instruction for two types of visual arts projects. The first centred on printmaking (Figure 1) where participants modified either photos of themselves taken by the arts facilitator or photos they chose from a National Geographic magazine. The project unfolded over a 3-week period, which gave participants enough time to master relatively intricate printmaking techniques.

Figure 1: Printmaking

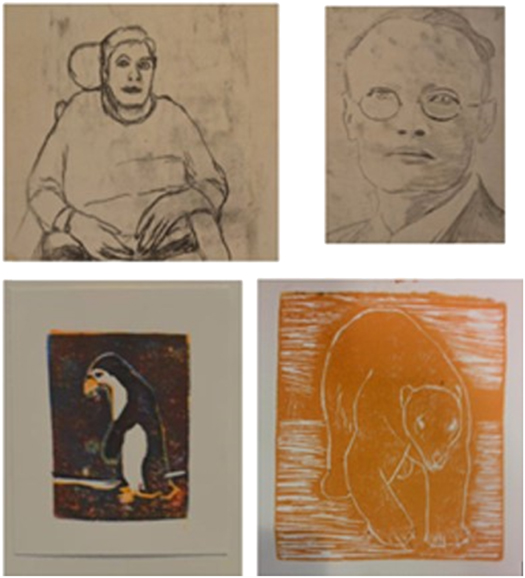

The second project involved an alcohol ink technique (Figure 2) where participants learned to paint with a range of inks using long cotton swabs, sponges, alcohol wipes, and toothpicks to achieve a variety of effects. This project also spanned several weeks to give residents sufficient time to master the ink painting techniques and use of the tools to achieve artistic effects.

Figure 2: Alcohol ink painting

The AAP coordinator felt that the residents’ active engagement in the creative visual arts projects allowed them to transcend the limitations of their disabilities: “When they are engaged in creating, there is a sense of stillness … They forget about their condition, pain and troubles. They are in the present moment creating a work of art.” Residents particularly appreciated the AAP coordinator’s enthusiasm in supporting their desire to use art to express themselves in unique and personal ways. As resident (R1) noted, “She is very honestly motivated. I like her direction more than anything else.”

Residents also commented on how participation in the AAP instilled a deeper sense of meaning and purpose in their lives. As resident (R1) noted, “If I were not doing this, I would be reading or watching TV … these are things from the outside into your brain … and doing arts is like putting something out from inside.” On the AAP Facebook page, resident (R6) commented on the impact of the AAP in her life: “I feel that I am in search of a certain meaning while creating and making sense of my life and environment. Expressive communication through the visual arts involves honesty and simplicity.” Residents also underlined the importance of learning a variety of art techniques to represent unique and deeply personal aspects of their life experiences through artwork.

Several residents spoke of their involvement in the AAP as a spiritual experience. One resident (R5) noted that “Life is not just here and now. I was influenced by my faith, and I believe that the arts bring a big deal about life, and how I approach life.” Other residents used similar terms in describing their engagement, such as this comment from resident (R3): “The art grounds me.” Resident (R9) said “It puts me in contact with my soul” and then explained how the AAP brought her a sense of happiness and hope:

I also got images from Bhutan, a Buddhist place in Asia that measure their success in happiness. I thought that was the most important reason for a country to be successful, alive. And this gives me hope, Bhutan gives me hope.

Most residents commented on how being part of the AAP led them to reminisce about meaningful events in their younger lives. One resident (R2) remembered doing printmaking in high school: “I enjoy the printmaking because it’s a different process. I used to do that in school and I really enjoyed it … and the high school we had a very good arts teacher.” Some residents mentioned selecting printmaking images that reminded them of activities they had enjoyed. For example, one resident chose images of the beach because she grew up close to the ocean and often walked on the beach. A few residents remembered socializing with family, friends, and community members when previously involved in the arts. As one staffer (S1) noted, “This is about their history, where they come from … when they were youngsters … It opens them up … And they’re also willing to share with us their history.”

Engagement with the Community

To display AAP residents’ artwork, the AAP coordinator organized a public art exhibit at the Spruce Meadow Art Gallery. This widely advertised event opened with a ceremony attended by AAP staff and residents, members of an elder care advocacy agency, and recreational centre staff. The exhibit featured 30 art pieces from the 12 residents in the program, which were arranged in three separate displays. One wall showed the alcohol ink paintings; another, the printmaking images, and the last wall featured the printmaking canvasses of the residents’ own pictures (see Figure 3) with the title “Selfie.” The residents were also given the opportunity to price and sell their artwork to members of the public.

Figure 3: The “Selfie” wall at the exhibit

Residents greatly appreciated the opportunity to show their artwork in the community, as illustrated by this quote by resident (R3): “You feel good because you are on an outing … it’s good to be outside and seeing what other people have done. That was very nice.” In an interview with a local TV station, resident (R2) remarked that the exhibit reflected their collective effort as a group of artists. She said, “It’s quite remarkable to see the entirety of it … one piece is okay … but 100 pieces hanging, that’s remarkable. It’s a case of the whole being much greater than the parts.” She went on to observe that “It’s really beautiful to see something that you create be hanging on the wall. And the public look at it and say “wow.” That’s really something … And even more when they say “I want that.”

The residents felt the exhibit helped reaffirm their identity as artists, as illustrated by this quote from resident (R2): “Now the community knows about our arts. And not because we are in rehab, we aren’t just sitting and vegetating.” She further commented on how the exhibit helped her transcend the sense of being institutionalized in a care facility: “I have this to look forward to and having the exhibition is really important. Here, it’s very easy to get depressed. … because you are stuck here in four walls.” A staffer similarly commented on the benefit of the exhibit for residents:

A lot of them were artists previously, so it’s a way for them to be creative again, they are encouraged by family to participate again and get out from their comfort zone a little bit. If they had a stroke, they are encouraged to use their hands again … to be creative and make something and be proud of doing something that’s different. (S1)

One staffer (S3) noted that family members were in disbelief at the quality of their relatives’ artwork: “All the family members are always shocked; one participant’s son said that he never thought it could be possible ... She is 97.”

Residents also greatly appreciated the care put into displaying their art in the gallery. Several noted how the use of frames and the overall arrangement greatly improved the appeal of their work. One resident hoped that the quality of the exhibit and the diversity of the artwork would help dispel the myth that people in residential care lack ability and talent. Another resident (R9) similarly commented on how the exhibit “provides an opportunity for the world, the community, to learn about what you’re doing here. I feel very lucky to be part of that. The sense of community is here.”

Another important aspect of the exhibit was the arrangement for residents to sell their artwork to the public. Several of them sold pieces during the exhibit, an experience they found validated their abilities as artists. As one resident (R2) said, “I’m very fortunate that people even purchase some of my arts. That’s terribly satisfying. Somebody else likes your work and spends money on that. … and the fact that now they have these arts in their home.” Staff member (S3) similarly commented on the value of this aspect of the program: “There is more confidence … and just the fact that they’re selling their art is amazing.”

In addition, the exhibit facilitated meetings between residents and community members that were also artists. One staffer described the following successful connection:

A participant met another artist at the art gallery and they had an interaction. The young lady out there was an artist also … It was like meeting a new friend. And when her exhibit went on, the participant went to see hers, so they really developed a connection. (S1)

Discussion

The AAP coordinator designed the creative visual arts program to engage residents in artistic self-expression and increase their mastery of intricate art techniques. With professional guidance, she supported residents in creating unique and personalized pieces of art. The AAP stood in contrast to the typical arts and crafts programs that rely on piecemeal projects aimed to distract participants (Timonen & O’Dwyer, 2009). The AAP coordinator recognized the residents’ skills and motivated them to learn new techniques. Residents reported feeling respected both as individuals and for their artistic skills. Pavlicevic and Ansdell (Reference Pavlicevic and Ansdell2004) similarly reported on the value of this type of engagement in a study of arts programs for older people. They found that supportive rapport between the arts facilitator and participants was crucial in maintaining motivation and commitment to the program.

Findings from resident interviews and observations suggest that the AAP contributed to a process of gerotranscendence in this group. The nature of the art projects in the AAP as well as the coordinator’s guidance and encouragement played a role in triggering residents to reminisce on past meaningful events that shaped their lives and contributed to their sense of identity. The majority had a background in the arts although they were no longer practicing due to their disability and admission into care. As part of their involvement with the AAP, most residents recalled memories of the role of the arts in their younger years and felt a renewed sense of identity as an artist. In that sense, residents developed an emergent sense of cosmic transcendence as they reinterpreted or positively reminisced about “events and situations from childhood or other earlier periods in life” (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2011, p. 169). Specifically, the AAP seemed instrumental in prompting residents to explore previously hidden or neglected aspects of the self and gain a renewed appreciation of their identity as artists.

Such reminiscence should be considered an essential aspect of achieving gerotranscendence as individuals simultaneously reflected on past, present, and even future aspects of their lives (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005). This finding echoes the results of other studies which have reported that involvement in creative visual arts programs induces a life review and intense reminiscence (Greaves & Farbus, Reference Greaves and Farbus2006; Greer et al., Reference Greer, Fleuriet and Cantu2012). This process was also enhanced by the art exhibit – residents felt validated by the public interest in their artwork and proud that the exhibit challenged misinformed views of older adults in care as lacking abilities.

The findings on resident interactions also suggest the presence of gerotranscendence. Staff observed how residents interacted minimally with others on the care unit but seemed to readily engage with each other during the AAP. The residents themselves spoke of the stories they shared, and many said they valued their interactions with each other as much as the artwork they created. This is an important step in reaching gerotranscendence because meaningful social relationships have been shown to improve self-worth among older adults, contribute to personal growth, increase self-esteem, and provide a sense of purpose (Avlund, Damsgaard, & Holstein, Reference Avlund, Damsgaard and Holstein1998; Cohen, Reference Cohen2005; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Perlstein, Chapline, Kelly, Firth and Simmens2006; Fisher & Specht, Reference Fisher and Specht1999).

The AAP also fostered connectedness between residents and the broader community. In joining the AAP, participants described being motivated by a desire to express themselves as artists within the community. They felt the exhibit would help them transcend the stigma and isolation they felt as residents in a care facility. They also felt a great sense of pride in their accomplishments. These feelings facilitated a realignment of their self-image in relation to others, including family, friends, and the local community. They appreciated how people began to see them favourably as talented artists.

Overall, the testimonies of residents on how the AAP enhanced their lives reflect, to some extent, the process of gerotranscendence. It is difficult to confidently confirm whether all residents fully engaged in transcendence at the cosmic level, the level of self, and the level of social and individual relations. It is possible that the process of reaching a high level of gerotranscendence was hindered by illness, grief, conflict with social ideals, along with the nature of care these older adults received (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam1996; Wadensten & Carlsson, Reference Wadensten and Carlsson2003). For these reasons, we suggest that our findings reflect how gerotranscendence occurred in varied ways in our sample and that each resident likely reached different levels of depth in transcendence (Jewell, Reference Jewell2014).

Just as importantly, the study supports the value of using Tornstam’s (2005) theory of gerotranscendence to fully understand the experiences of older adults in residential care. In this regard, our findings echo those results of Stephenson (Reference Stephenson2013) who highlighted how a Creative Aging Therapeutic Services art therapy program promoted “artist identity, motivation, connection to others, and movement toward gerotranscendence” among a group of older participants in the community (p. 156). Nonetheless, it is fair to say there is insufficient research on the relationship between meaningful involvement in the arts and gerotranscendence, particularly in the context of residential care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, with only one participant being male, there is an oversampling of female participants. Second, as this is a qualitative study with a convenience sample of 10 participants, the findings cannot be extrapolated to the overall population living in complex residential care. A quantitative study with a larger, diversified sample of older adults would allow researching gerotranscendence in a more representative way. Third, ethnic diversity is absent in the sample. Therefore, the findings may not apply to individuals of other cultural backgrounds who might have different engagement with the arts or complex care. Fourth, participants in the visual arts program received specialized, complex rehabilitative care rather than long-term nursing care. The participants had functional and mobility limitations but none had dementia-related cognitive impairment. Future research should, therefore, consider evaluating the benefits of creative visual arts–making programs for longer-term residents in the later stages of life. Fifth, the sample size for staff is very small (n = 3). The study also did not include volunteers in its sample due to their limited experience with the program and residents. More experienced volunteers would undoubtedly contribute to the program’s success. Future research should include interviews with volunteers to better understand their role in the program.

Implications

Hauge (Reference Hauge1998) argued that the theory of gerotranscendence is relevant to the practice of nursing because it challenges medicalized understandings of the aging process. However, studies have shown that interpretations of the signs of gerotranscendence vary widely among nursing staff working with older adults. Tornstam and Törnqvist (Reference Tornstam and Törnqvist2000) studied nursing staff’s interpretation of behaviours indicative of gerotranscendence and found that nurses regarded most of these behaviours as caused by inactivity, or as the symptoms of decline. Wadensten and Carlsson (Reference Wadensten and Carlsson2003) similarly found that behaviours such as changed perception of time and space, withdrawal from casual social activities, and a preference for sitting alone and thinking were viewed by nursing staff as signs of decline. In light of these results, guidelines to interpret gerotranscendent behaviours would help nursing staff develop a greater appreciation of this developmental process in residential care.

Pilot programs modelled after the AAP could further illuminate the extent to which creative visual arts programs mediate the psychosocial impact of residential care, encourage community inclusion, and alleviate loneliness in later life. Future studies involving creativity and aging could use the participatory action research methodology (Freire, 1970; Hall, Reference Hall1992). A relevant aspect of this methodology is praxis, where researchers, community members, residents in care, family members, and staff become advocates in efforts to increase the availability of creative art programs in residential care.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the arts may be a useful tool to foster greater meaning in later life and development towards gerotranscendence. Overall, the art exhibit allowed recognition of the residents’ artistic work by the community, increased their sense of self-esteem and self-confidence, and validated their identity as artists. Arguably, the exhibit can be seen as a “process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age” (World Health Organization, 2005, para. 1). Ultimately, programs like the AAP offer a space for creativity, reflection, and meaningful community engagement. Such programs play an important role in reducing not just the psychological, but also the social effects of medicalized residential care.

As Tornstam (Reference Tornstam2011) noted, perhaps only 20 per cent of older adults reach a high degree of gerotranscendence, potentially because the process is hindered for various reasons. As a result, “some old people who are suffering from, for example, anxiety and depression may not be suffering as a consequence of retirement, loneliness or old age as such, but rather as a result of being hindered or hindering themselves in their developmental process” (p. 177). The structure of residential care, which is organized by medical routines, lacks opportunities for self-expression and may actually be blocking successful transition into gerotranscendence in adult residents. Advocacy and education on the value and health benefits of gerotranscendence, along with participatory programs in the arts, would be effective strategies to overcome these institutional barriers and improve well-being in care.