CHD is a broad term that defines a range of conditions involving the structure of the heart present at birth. Reference Dolk, Loane and Garne1 CHD is the most common type of birth defect, affecting around 8/1000 babies born in the UK. Reference Dadvand, Rankin, Shirley, Rushton and Pless-Mulloli2 Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is a severe defect, where the left-sided structures of the heart are severely underdeveloped, leaving the right ventricle as the only functional pumping chamber of the heart. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome accounts for 2–3% of all CHD and if left untreated leads to heart failure and death in the first weeks of life. Reference Liu, Oza and Hogan3 After birth, the neonate will present with cyanosis, failure to thrive, tachypnoea, and lethargy. Reference Moodie4 Treatment involves a series of staged surgical interventions aiming to use the only functioning ventricle (right) to support the systemic circulation, while the systemic venous return is redirected to the lungs, bypassing the heart. Reference Gobergs, Salputra and Lubaua5 This is achieved with the Norwood sequence (involving three stages): Stage 1 uses the right ventricle to pump blood systemically via a common outlet provided by a reconstructed aorta together with the pulmonary artery, while pulmonary blood flow is provided by a systemic to pulmonary shunt; Stage 2 occurs at around 3–4 months of age when the systemic to pulmonary shunt is exchanged for a Glenn Shunt, where the superior vena cava is redirected to the pulmonary artery; and Stage 3, the Fontan procedure, to redirect blood from the inferior vena cava to the pulmonary artery via a conduit. Thus, the systemic venous return is separated from the pulmonary venous return avoiding intracardiac mixing of blood and cyanosis. Despite advancements in treatment and surgical techniques during the last 30 years, Reference Kutty, Jacobs, Thompson and Danford6 children and adults with hypoplastic left heart syndrome still report several physical limitations during daily activities, a reduced exercise capacity, and a poorer quality of life overall. Reference Uzark, Zak and Shrader7

Physical activity plays a fundamental role in childhood development, contributing to healthy growth Reference Malina8 ; improved cardiovascular fitness; and quality of life. For children with CHD, these benefits may be heightened. Reference Tran, Gibson and Maiorana9 However, children diagnosed with CHD (irrespective of complexity) usually report more sedentary behaviours compared to peers and reduced physical activity participation. Reference Voss, Duncombe, Dean, de Souza and Harris10 This worsens with age and disproportionately affects girls, and those from areas of higher deprivation. Reference Voss, Duncombe, Dean, de Souza and Harris10 Several barriers to physical activity participation, such as social stigma and parental overprotection, have been identified in children with CHD. Reference Moola, McCrindle and Longmuir11 Currently, there is no consensus on what constitutes optimal activity levels. However, based on evidence from other chronic conditions, an individualised approach to physical activity, with adaptation over the life course is likely to be beneficial. Reference Anderson and Durstine12

The aim of this study was to explore the engagement in physical activity and activity levels in these children and how family social functioning/lifestyle acts as barriers or enablers.

Patients and methods

Data were collated via a combination of activity monitors, questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews.

Participants

Children with a Fontan circulation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome, aged 5–16 years were identified via a research database at AlderHey Children’s Hospital, and social media between June 2021 and March 2022. Each participant received information explaining the study. Written consent was recorded from participants aged 16 years and older, with assent from those <16 years. Inclusion criteria comprised diagnosis of a single ventricle heart pathology in the child, and subsequent Fontan circulation.

Data collection

Data collection comprised three stages: (i) children wore an activity monitor for ≥7 days; (ii) children and siblings (if any) completed a bespoke questionnaire (10-15 minutes to complete); and (iii) parents completed a semi-structured interview (20–30 minutes).

Activity monitors

Physical activity was monitored using a tri-axial accelerometer (Actigraph wGT3x-BT) worn on the right hip for seven consecutive days, with removal for sleeping and water-based activities. Times the device was worn were recorded manually. Accelerometer nonwear time was defined as 60 consecutive minutes of zero counts/min−1. Reference Troiano13 Data were considered for analysis if there was >7 hours of wear time per day, Reference Corder, Ekelund, Steele, Wareham and Brage14 for a minimum of 4 days, including at least one weekend day. Reference Trost, Loprinzi, Moore and Pfeiffer15

Activity monitors’ data analysis

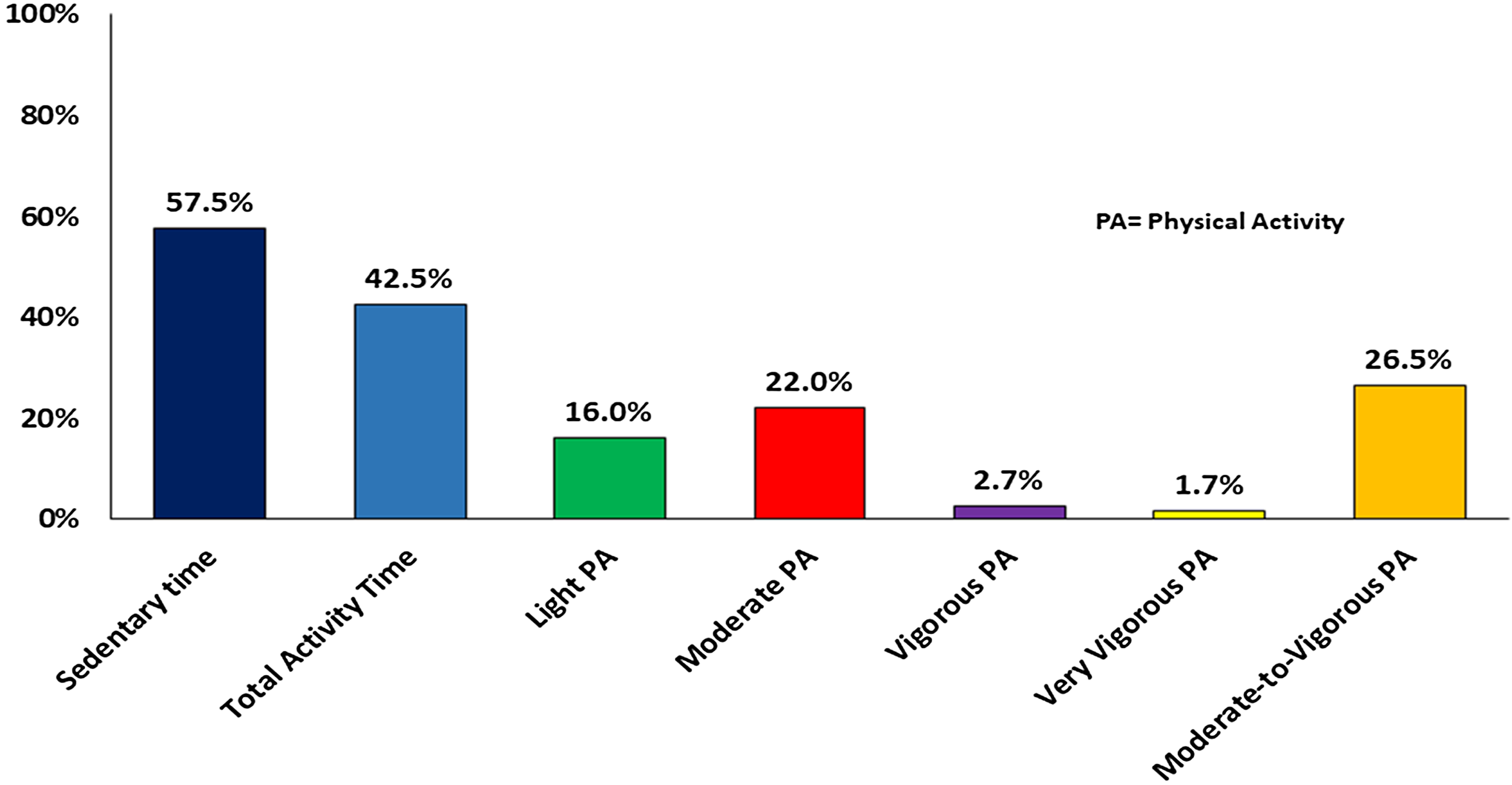

The ActiLife software, version 6.2 (ActiGraph, Florida) was used to download the data and perform scoring and wear-time validation analysis. Raw acceleration data were converted to 60-s epoch activity count data (counts·min−1). Physical activity intensity was based on the following cut points (counts min−Reference Dolk, Loane and Garne1 ) Reference Freedson, Pober and Janz16 : light (≥150), moderate (≥500), and vigorous (≥4000). Total time (minutes) spent in the above thresholds was calculated (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Activity and sedentary time in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Figure shows the data from the activity monitors.

Children/siblings questionnaire

Two questionnaires were developed: one for children with CHD and one for siblings. Questionnaires comprised two sections: (i) multiple choices questions based on “emoji scores” Reference Leo, Murphy, Gambling, Long, Jones and Perry17 and (ii) free narrative section where the child could describe daily routines. For children with CHD, the questions (Supplementary Table S1) related to aspects of daily life, providing insight into barriers/facilitators in physical activity. The sibling questionnaire enabled the children to record the impact of their siblings’ condition on their life. Questionnaires were developed and piloted with a dedicated Patient and Public Involvement group.

Children/siblings’ questionnaire analysis

The results of the questionnaires were reported using descriptive statistics. No formal statistical significance testing was undertaken due to small numbers.

Parents’ interviews

The interviews explored parental experiences, particularly the impact of CHD on family activities, daily activities, sport, and physical activity. A semi-structured interview format was utilised, with each interview lasting ∼30 minutes.

Parents’ interview analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were analysed in accordance with the six-step thematic analysis. Reference Clarke and Braun18 All transcripts were read by three researchers (DGL/DAL/RRL) and discussed in dedicated meetings.

Results

Participants

Fifteen participants were recruited, seven parents and seven children (three girls/four boys), ranging from 5 to 16 years (mean (SD) 8.8 (3.7) years; one aged >11 years). Only one sibling was recruited and therefore this data was excluded to ensure confidentiality.

Activity monitors

All children wore the activity monitors for ≥7 hours per day. Mean daily sedentary time (ST) over 7 days (including two weekend days) was higher (57.5% of wear time) than mean daily total activity (TA) time (42.5% of wear time). Mean (SD) daily time spent in moderate-to-vigorous activity was 153 (36) minutes (26.5% of the total wear time) (Fig 1). No difference in activity level was observed between weekdays and weekends (Table 1).

Table 1. Differences in activity time and sedentary time between week days and weekend days in children with Hhypoplastic left heart syndrome who received a Fontan procedure.

Children/siblings questionnaires

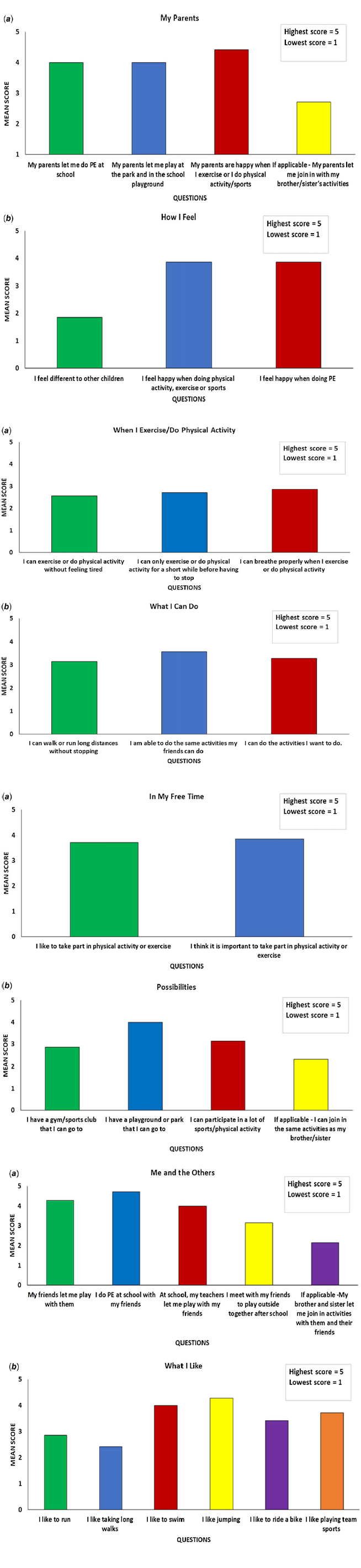

Results from children’s questionnaires are presented in Figure 2. Physical activities of interest suggested by the children (H.7–Supplementary Table S1) were dance (33%), short walks (17%), and climbing (17%).

Figure 2. (a) Results from the children questionnaire: Limits imposed by parents in physical activity participation in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (A), and the way these child feels about engagement in physical activity (B). ( b) Results from the children questionnaire: Limitations reported by children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome when doing physical activity (A and B). ( c) Results from the children questionnaire: Considerations on participation in physical activity in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome in their free time (A); and possibilities of these children to engage in physical activities (B). (d) Results from the children questionnaire: Interaction between children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and others during physical activity (A); and activities that these children like (B).

Parents’ interviews

Data generated from six interviews (one interview undertaken with parents together) were analysed. Four key themes were identified. A new lease of life – post Fontan highlights the impact of the surgery on physical activity engagement by children following completion of the Fontan circulation. Setting limits – managing limitations explores the different mechanisms through which families manage physical activity with a child with a single ventricle. The wider world – how others set limits examines the way in which the community affects engagement in physical activity in children with a single ventricle. Finally, I fear the future – parental concerns examining fears and anxiety that parents experience in relation to their child’s condition.

A new lease of life – post-Fontan

All the parents spoke about the positive impact of the Fontan circulation on their child’s ability to engage in physical activity. Post-surgery, parents reported that their child was less exhausted and had fewer limitations in physical activity participation:

“Before his operation he was taking Wednesday off as he was exhausted. After the operation he is in full time school, he keeps up with his peers. I’m thrilled about it”[05 Mother]

Prior to completion of the Fontan circulation, cyanosis on exertion was common. Parents frequently described these changes as visible indicators of the child’s limitations, providing a measure of how much a child could do.

“He would join PE, but his teachers are really aware of his condition, so if his lips get blue or if he gets breathless, then they make sure he sits down and rest.”[09 Mother]

However, these external markers disappeared post-surgery and changed the way the child was perceived.

“Since he started school, it shocked the people I tell it to, they are like “has he?!”. This because he is doing just fine… he doesn't look like he has got a heart condition. People are very shocked”[05 Mother]

For some parents, this raised concerns that their child risked being pushed too hard when it came to engaging in physical activity:

“He had some swimming lessons at a sport facility and the instructor was like ‘ok, ok, I got it’ [referring to #03’s condition] and then one day she [the instructor] pushes (#03)too much and (#03)is like ‘I am not coming again’… because she [the instructor] just did not get it…”[03 Mother]

Setting limits – managing limitations

Parents managed their child’s condition in different ways, influencing the way in which limits were imposed and the way the child was included in their activities as a family. In general, the parents interviewed recognised the importance of physical activity to improve their child’s fitness and cardiovascular health:

“When she got 6 months old I would let her participate in ‘water babies’, which I thought was a good respiratory training… and from there I always tried to keep her active.”[01 Mother]

For some parents, this meant supported the child to effectively judge when to push themselves, as well as when to stop and have a quick break:

“He self-manages himself very well. So, he understands his limitations and knows when he has to stop, … he does self-manage very well.”[03 Father]

On occasions, this could mean pushing their own concerns away and allowing the child to make their own decisions.

“If he want to do something we completely let him do that, even if sometimes we caught us thinking ‘uhm… not so sure about that… it could be dangerous…’ “[03 Mother]

However, other parents reported a more risk-averse approach, stepping in when they perceived their child was overdoing things:

“He just keeps going, to the point I have to tell him ‘come and get your drink, you are getting very hot’”[05 Mother]

All the parents discussed their attempts not to treat their child differently to their siblings. However, for some families, this meant adjusting activities to enable the child to participate:

“We are very active, really…But when #03 was 3 he was riding a quad bike because there was a significant difference in mobility… he couldn't keep up with his brother and his cousins …” [03 Mother]

Conversely, others reported adapting family activities to their child’s condition, thereby avoiding activities that could potentially exhaust their child:

“We don't tend to do anything in the evening as a family because of #09 limitations. What we don't want to do is to tire him out to the point where he can't attend school the next day.” [09 Mother]

Additional limitations to engaging in physical activity were associated with environmental factors, such as temperature:

“He struggled a little when he joined the football team, and it [the training] was outside and was in the winter… and he got too cold even if he had thermal clothes on, we had to stop him from continuing with the training." [08 Mother]

The wider world – how others set limits

Parents spoke about a spectrum of approaches to managing engagement in physical activity at school. For some, it was treated as a risky activity by the school, resulting in limitations placed on the child.

“School, obviously there was always the risk assessment… I mean, why shouldn't she do PE? You know, she can sit down if she needs to rest… I don't see the point to limit her participation i.” [01 Mother]

For others, whilst the child was included in activities, they were identified as ‘disabled’ by the teacher:

“At school they were letting them have a race and were trying to make it even for everyone […] and they had to wear a head-band to let the other boys know they had to give them a chance in the race, but he literally outraced everyone” [05 Mother]

In contrast, other children were trusted by their parents and teachers to self-manage.

“They know he has a problem, but I don't think it worries them at all [in limiting what he can do], so I don't think they are limiting him but as soon as he says ‘I would like to sit down for a minute’ they are quite happy to allow him to step back.”[03 Father]

Fear for the future – parental concerns

Uncertainty about the future, led all interviewed parents to express fear, with most of them preferring to live in the present and not talk/think about the future.

“I think it is quite hard to know what to plan for the future not knowing how much time we have got with them [their children]…”[09 Mother]

Discussion

The children recruited for this study reported an average daily physical activity higher than the minimum recommended by the national guidelines, but also a high proportion spent in sedentary behaviours. The interviews highlighted different mechanisms for managing their child’s level of physical activity. Whilst some parents supported the child in self-managing activities, others felt it necessary to impose limitations to protect their child. This was confounded by the spectrum across which the wider community perceived their child, either adding to restrictions, or being unaware of the child’s limitations. Whilst the children were all much more active following completion of the Fontan circulation, parents had ongoing concerns over the future.

Evidence examining engagement and perception of physical activity in children with a Fontan circulation is limited. This study demonstrated an average daily moderate-to-vigorous activity more than 2.5 times the recommended 60 minutes for children and adolescents Reference Oja and Titze19 . Other observational studies measuring physical activity in healthy children in England Reference Craig, Mindell and Hirani20,Reference Ramirez-Rico, Hilland, Foweather, Fernandez-Garcia and Fairclough21 suggest that only 31% of boys and 22% of girls aged 4–15 years in England, Reference Craig, Mindell and Hirani20 and 27% of children living in the North-West Reference Ramirez-Rico, Hilland, Foweather, Fernandez-Garcia and Fairclough21 meet recommended levels of daily physical activity. Moderate-to-vigorous activity has been shown to decrease with age, with children aged 4–7 averaging 124 minutes per day (boys) and 101 minutes (girls), dropping to 52 (boys) and 28 (girls) minutes in those aged 12–15 years. Reference Craig, Mindell and Hirani20 Data derived from the CHD population are variable, with some evidence of reduced physical activity levels and increased sedentary behaviour, Reference McCrindle, Williams and Mital22 while others have shown that despite a CHD diagnosis, children are meeting physical activity recommendations Reference Brudy, Hock and Häcker23 with no significant differences in sedentary time. Reference Ewalt, Danduran, Strath, Moerchen and Swartz24 Sedentary behaviour in children has been identified as a risk factor for obesity and cardio-metabolic diseases Reference Saunders, Chaput and Tremblay25 which may disproportionately impact those with CHD, Reference Andonian, Langer and Beckmann26 further reducing physical fitness and negatively impacting quality of life. Reference Gauthier, Curran, O’Neill, Alexander and Rhodes27 Physical activity interventions have shown to increase the submaximal cardiorespiratory fitness in children with CHD. Reference Williams, Wadey, Pieles, Stuart, Taylor and Long28 However, children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome represent the highest risk group among CHD and further studies are required to assess the effects of physical activity/exercise intervention in this population before making appropriate recommendations.

Parental attitudes to physical activity were predominantly positive, although approaches to moderating exertion differed. The impact of parental fears and anxiety on physical activity are well documented, Reference Bennett, Voss, Faulkner and Harris29 with a positive parental attitude toward physical activity important in promoting self-efficacy in CHD children. Reference Moola, Faulkner, Kirsh and Kilburn30 Parental perceptions of staff attitudes suggest teachers often adopt a precautionary approach to physical activity in children with CHD. Since children spend a considerable proportion of their waking time at school, Reference Long31 limiting physical education and other play activities may significantly impact overall physical activity levels. Perceived risk of physical activity in children with CHD therefore needs to be more widely addressed, with effective support in place for schools and families.

Study limitations

The sample size is small, although acceptable as a pilot study. Geographic diversity of the sample was limited, and participation was likely to be biased towards families who had a more positive attitude towards physical activity. Additionally, activity level of the children in the sample may have been modified by observation (Hawthorne effect).

Practical implications

Although the level of sedentary behaviour of children in this study was similar to their healthy peers, the children spent a significant time sedentary. Reducing sedentary behaviour is crucial in preventing co-morbidities and further reducing quality of life in this cohort. Reference Andonian, Langer and Beckmann26 Children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (and CHD in general) have been shown to have a reduced exercise capacity, Reference Haley and Davis32 which has been linked to reduce neurodevelopment. Reference Cooney, Campbell, Wolfe, DiMaria and Rausch33 Physical activity increases exercise capacity for children with single ventricle heart disease Reference Haley and Davis32 and has also been shown to potentially reduce NT-proBNP levels (markers of cardiac stress) in these children. Reference Perrone, Santilli and De Zorzi34 Despite this, physical activity participation is still restricted in these children due to healthcare professionals and parents’ concerns regarding safety. Reference Caterini, Campisi and Cifra35 Further studies that assess the long-term effects of physical activity in children with CHD are required, Reference Williams, Wadey, Pieles, Stuart, Taylor and Long28 with appropriate assessment of cardiorespiratory fitness pre- and post-intervention. Engaging the whole family in physical activity, Reference Brown, Atkin, Panter, Wong, Chinapaw and van Sluijs36 and reducing barriers through increased awareness of the beneficial effects, and safety of physical activity, are the first steps to improving physical activity participation.

Conclusion

Children with a Fontan circulation appear to participate in physical activity commensurate with national recommendations, with similar time spent engaged in sedentary behaviours. Parents’ support and external influences (e.g., teachers/relatives) play an important role in supporting engagement in physical activity. Increased awareness of the safety and effectiveness of physical activity in children with CHD amongst parents, supported by educational materials around physical activity for the wider community, is needed to promote greater engagement. Further studies to investigate interventions that promote physical activity participation and the long-term effects of physical activity in this population are required.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951122003754

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Professor Helen Jones, Liverpool John Moores University (UK) for providing the activity monitors for the study.

Financial support

This project has received funding from The Hugh Greenwood Legacy for Children’s Health Research Fund (Grant:B19).

Conflicts of interest

DGL, MR, AAL, and RRL declare no conflict of interest. DAL has received investigator-initiated educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS); been a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, and BMS/Pfizer and consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, and BMS/Pfizer; all outside the submitted work.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (UK HRA and NHS ethics) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 4 (ref. 20/WA/0144).