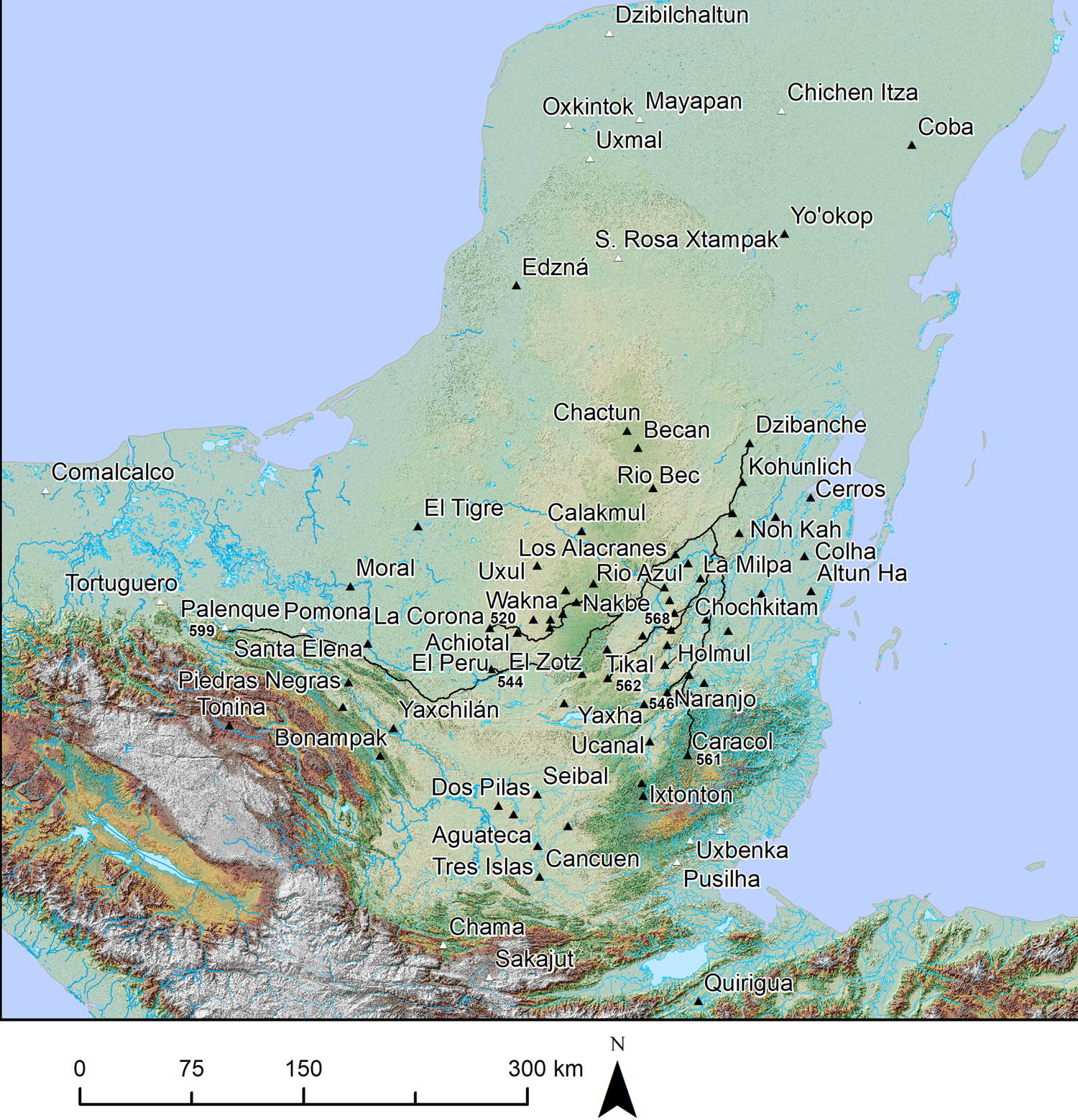

The notion that Classic Maya kingdoms were able to grow into hegemonies has gained increased acceptance in the last decades, thanks to epigraphic data unearthed at numerous sites that reveal a network of client polities centered on the Kaanu'l dynasty based at Dzibanche and Calakmul. The Kaanu'l greater domain extended over most of the Lowland Maya kingdoms during the Classic period, circa AD 500–751 (Figure 1). Much of what is known about this hegemony comes from texts produced during the peak of its power in the Late Classic period, from AD 640 to 736, when the dynasty was situated at Calakmul. Much more obscure is its early history, from ca. AD 400 to 571, when the kingdom rapidly expanded from Dzibanche. In this article we present new archaeological and epigraphic data from Chochkitam, a little-known site in northeastern Guatemala, revealing its political standing as a seat of royal power in the geopolitics of the Maya Lowlands before, during, and after Kaanu'l hegemony. More broadly, these data contribute to ongoing discussions of the origins of the Kaanu'l dynasty, the identity of its early rulers, specific modalities of royal succession and corulership, and, finally, the routes through which the hegemony was expanded.

Figure 1. Map of Maya Lowlands showing the known extent of Kaanu'l hegemony during the Dzibanche period and hypothetical routes from Dzibanche (avoiding the wetlands) and other sites mentioned in the text (drawn by Francisco Estrada-Belli; terrain data from NASA SRTM). (Color online)

The “Snake Head” k'uhul Kaanu'l ajaw (“holy Kaanu'l lord”) royal title is one of the most frequently occurring titles in Classic Maya political statements (Marcus Reference Marcus1976).Footnote 1 Martin and Grube (Reference Martin and Grube1995) suggested that it was associated with explicit expressions of overlordship, proposing that major Classic Maya kingdoms had hegemonic relations with smaller polities. Subsequent research revealed that place names were the main component of such royal emblem glyphs (Berlin Reference Berlin1958), although they did not always correspond to the place names associated with the archaeological sites occupied by the holders of any given emblem glyph (Stuart and Houston Reference Stuart and Houston1994). It later became apparent that the Late Classic seat of the Kaanu'l dynasty was located at the archaeological site of Calakmul, known as Chi'k Nab and Huxte’ Tuun in the hieroglyphic inscriptions (Martin Reference Martin and Carrasco Vargas1996, Reference Martin2005).

The discovery of a hieroglyphic stairway celebrating conquests and rituals undertaken by Early Classic Kaanu'l kings at the site of Dzibanche suggested that it may have been the early capital of the Kaanu'l kingdom (Martin Reference Martin2020; Nalda Reference Nalda2004; Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Nalda2004). Excavations at the site uncovered several richly furnished tombs. One of these potentially royal burials contained a bone bloodletter, with an inscription identifying its owner as “holy Kaanu'l lord Jom Uhut Chan” (also known as “Sky Witness”; Nalda and Balanzario Reference Nalda and Balanzario2004). Subsequent epigraphic discoveries at Dzibanche and Xunantunich provided evidence that the toponym of Kaanu'l of the “Snake King” emblem glyph was, in fact, the ancient name of Dzibanche and that the hub of Kaanu'l hegemony only moved to Calakmul in AD 636–640 (Helmke Reference Helmke and Awe2016; Martin and Velásquez Reference Martin and Velásquez2016).

Recent studies have expanded the list of Dzibanche-based Kaanu'l rulers. Martin and Beliaev (Reference Martin, Alexandre Tokovinine, Fialko, Arroyo, Salinas and Álvarez2017) identified references to K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’, known as Ruler 16 of the Kaanu'l dynastic list on the so-called codex-style ceramic vases (Martin Reference Martin, Kerr and Kerr1997, Reference Martin2017). The inscription on a wooden lintel from Dzibanche (Gann 1928) suggests that K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ became kaloomte’ (high king or paramount ruler) in AD 550. The text on a ceramic vessel at Uaxactun mentions him as an overlord of a previously unknown Tikal king. According to El Peru Stela 44, K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ also supervised the accession of a local ruler in AD 556. A reanalysis of the crucial passage on Altar 21 at Caracol credits the decisive defeat of Tikal ruler Wak Chan K'awiil in AD 562 by Dzibanche and Caracol forces to K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’, instead of to “Sky Witness,” as previously thought (Martin Reference Martin2020; Martin and Beliaev Reference Martin and Beliaev2017).

The new discoveries also implied that there was a chronological overlap of some sort between K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ and his apparent successor “Sky Witness.” The latter is mentioned as a “holy Kaanu'l lord” and a supervisor of a king's accession in AD 561 on Stela 1 at Los Alacranes, a subordinate polity 90 km south of Dzibanche (Grube Reference Grube and Šprajc2008). The revised chronology also failed to resolve discrepancies between accession dates of Kaanu'l dynasts, as reported in the lists on codex-style vases, and the dates of references to the same individuals on carved monuments. One possible explanation for the discrepancy would be a succession system in which rulers acceded to the “holy king” (k'uhul ajaw) office first and only later to the “hegemon” (kaloomte’) position, whereas the codex-style lists mentioned only those Kaanu'l lords who achieved the kaloomte’ rank (Martin Reference Martin2017, Reference Martin2020). At any point in time, a hegemon or high king would corule with one or more lesser “holy kings.” This system would enable the management of war campaigns on foreign lands while a ruler in power remained at home. This two-tier organization was attested at other Classic Maya royal houses, including those of Bonampak-Lacanha and Motul de San Jose (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013; Tokovinine and Zender Reference Tokovinine, Zender, Foias and Emery2012).

Our investigations at Chochkitam sought to uncover archaeological and historical data to fill a large gap in the history of a section of northern Peten that extended from Holmul to Rio Azul, for which little or no well-preserved texts exist. Of particular interest to us were any possible links to the ebb and flow of regional political influences during the middle of the Classic period; in particular, whether the Kaanu'l expansion prior to the decisive war against Tikal in AD 562 advanced through a direct route (Figure 1). The accession of Naranjo's ruler in AD 546 under Kaanu'l lord Tuun Kab Hix marked a terminus ante quem for the timing of the arrival of Kaanu'l armies into central Peten by this or an alternative route, following the coastline and the Belize River Valley. The site of Chochkitam appeared to be located precisely on a north–south inland route from Dzibanche to Tikal. This eastern land route would complement a western route connecting Dzibanche to La Corona and El Peru, which, according to contemporary textual references, was used by the Kaanu'l by AD 520, prior to the route that originated at Calakmul after AD 640 (Canuto and Barrientos Reference Canuto and Barrientos2013; Martin Reference Martin2008, Reference Martin2020).

Investigations at Chochkitam

The site of Chochkitam (CKT) was first reported in 1909 by archaeologist Raymond Merwin during the first Harvard University expedition in northern Peten (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1911). It was mapped by Tulane University's Frans Blom in 1924 who reported an inscribed monument (Blom Reference Blom1988; Morley Reference Morley1937–1938:Vol. 5). The site likely owes its name to a plant locally known as chooch-citam, “peccary-choch” (Roys Reference Roys1931). The site's three main monumental groups extend over approximately 0.5 km2 of upland ridge terrain and are connected by broad causeways (Figure 2). The Main and Merwin plazas form a continuous area of 2 ha. To the south are the Central Acropolis's royal courtyards. The North Group features a 10 m high pyramid, an 80 m long palatial structure to the south, and small lateral courtyards. The Northeast Group features an eastern pyramid and small range structures on a 5 m high plaza platform. Several residential groups surround the main ceremonial complex, forming the urban zone of a medium-sized city. Less dense residential zones extend for at least 3 km to the north and south.

Figure 2. Map of the ceremonial core of Chochkitam (drawn by Antolin Velasquez and Francisco Estrada-Belli).

Blom (Reference Blom1988; Morley Reference Morley1937–1938:Vol. 1) reported seven plain monuments from Chochkitam's main plaza and a carved one, Stela 1, which he photographed. In the north edge of the plaza, Blom noted an altar and a possible stela fragment near Stela 1; two other altars were found in front of the western palace, Structure IV, and another one was found in front of the eastern palace, Structure IX. An additional monument was noted in front of the north side of a pyramid at the south end of the Merwin Plaza, Building X.

Beginning in 2019, our team conducted survey and excavations at Chochkitam (see Supplemental Text 1). We updated the map of the site and investigated looters’ trenches in the main structures, locating three looted and one undisturbed royal tomb. In 2019, we redocumented Stela 1, confirming the good condition of its carving. We also recorded two partial altars and two adjoining fragments of another carved stela (Stela 2) in that same spot. The monument in front of Structure X, Stela A5, was found to be a probable altar with only minor traces of carving. In 2021, we located and documented a carved stela (Stela 3) in the Northeast Group. To test hypotheses about Chochkitam's position in relation to potential routes from Dzibanche to northern Peten. we developed several routes using GIS methods and plotted them against the location of known sites (see Supplemental Text 1 for a fuller description of methods).

Chochkitam's Royal Burials and Monuments

The earliest architecture encountered by our limited excavations at Chochkitam dates to the Late Preclassic period (400 BC–AD 250). It is a stairway on the central axis of Building VII, at the south end of the Main Plaza. Much more activity at the site has been documented for the Early Classic period (AD 250–550). In addition to a later version of that same acropolis stairway, we found Early Classic construction phases in Building XV and in the North Group (Figure 2). Greater building activity at the site, however, appears to have occurred during the Late Classic period (AD 550–830).

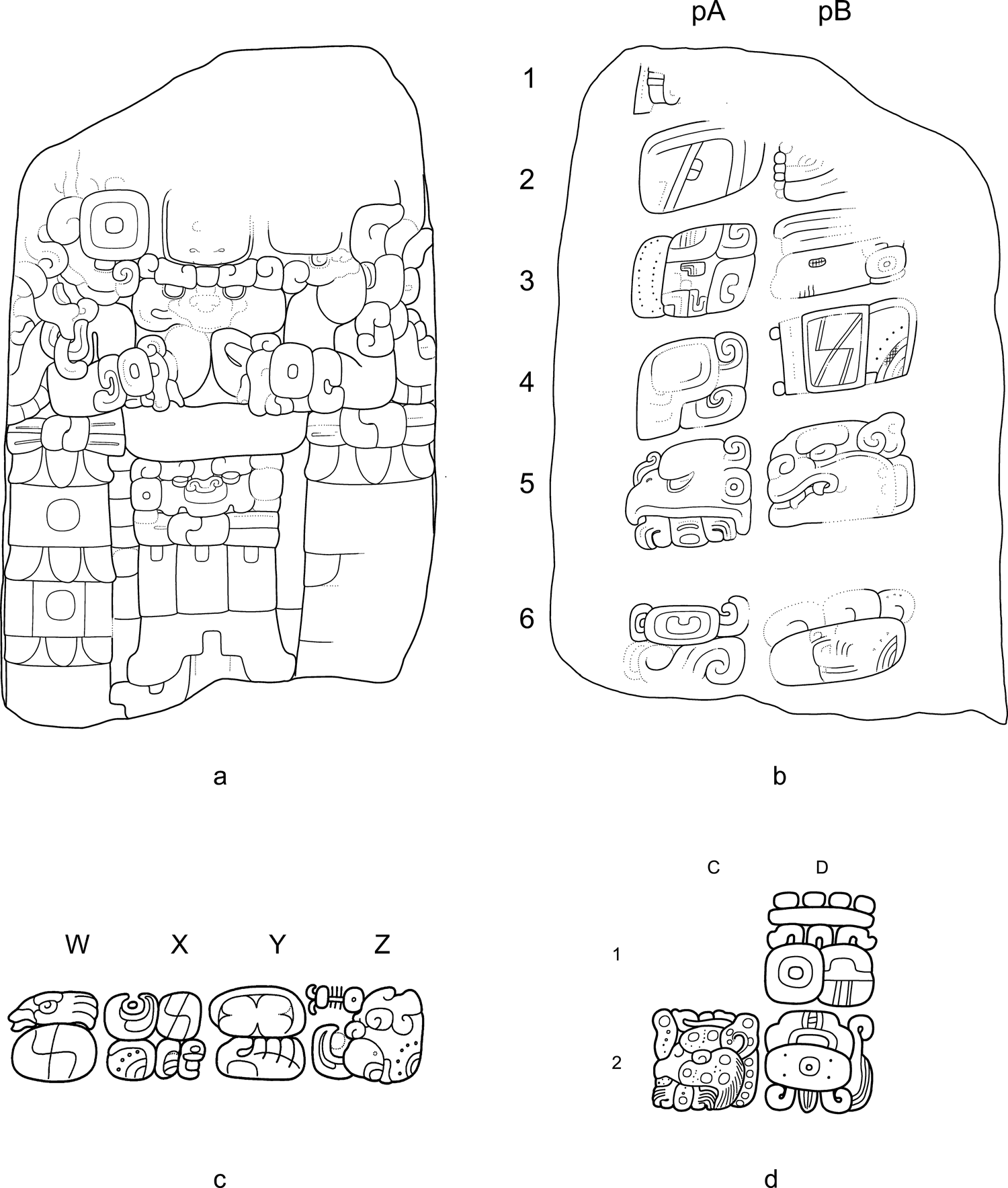

The pre-Kaanu'l perspective on Classic Maya kingship at Chochkitam is provided by Stela 3 (Figure 3a and 3b). This small monument, measuring 1.00 × 0.74 m, was left by looters on the back slope of the eastern Northeast Group pyramid. It is the central portion of a stela whose upper and lower sections are still missing. The relatively good preservation of the carving suggests that the monument was not exposed to the elements for a long time.

Figure 3. Chochkitam Stela 3: (a) front; (b) back; (c) detail of stucco frieze, Building A, Group II, Holmul (redrawn from Estrada Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada Belli and Tokovinine2016:Figure 6a); (d) detail of Lintel 11, Yaxchilan (drawn from a photograph by Ian Graham on file at the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, 2004.15.1.7683.4, by Alexandre Tokovinine).

The front of Stela 3 depicts a standing human figure holding a double-headed serpent, a common element of royal god-summoning rituals during period-ending ceremonies (Figure 3a). A large feline head is visible on the protagonist's belt. Both the body and the head of the protagonist are in full-frontal view. The style of the headdress and of smaller iconographic elements is consistent with Early Classic sculpture (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950). When these elements are considered together with the frontal view, the chronological distribution becomes more restricted: for example, at Tikal and Yaxha, such monuments are accompanied by strong visual links to Teotihuacan imagery that appears around AD 378 (Grube Reference Grube and Wurster2000; Stuart Reference Stuart, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000). There are no overt Teotihuacan traits in the imagery on CKT Stela 3, but the full-frontal view would suggest links with Central Peten.

The inscription on the back of the monument is arranged in two columns of hieroglyphic blocks (Figure 3b). The paleography of the text is solidly Early Classic. The narrative is visibly incomplete because its initial and final parts are on the missing fragments. The date and the predicate of the main sentence are lost. The glyphs in Blocks pA1 and pB1 are largely gone. Block pA2 contains a single logogram TE’ followed by a possible TAY grapheme in the remaining corner of pB2. The next word in the inscription in Block pA3 is “god” (K'UH). Therefore, the preceding part of the text contained the name of a deity or deities. There are at least two Classic Maya theonyms with TAY: Tayal/Tayel Chan K'inich and Juun Tayal Chan Ajawtaak, the latter being a common reference during period-ending ceremonies (Martin et al. Reference Martin2017; Tokovinine and Zender Reference Tokovinine, Zender, Foias and Emery2012). The TE’ (te’ for “wood, stick, tree”) logogram could be part of another theonym. However, it is just as likely that it belonged to a predicate referring to something that the god or gods did. Block pB3 contains a grapheme that looks like a raptorial bird head with a headband or another sign altogether on top of it. Surface damage complicates secure identification, but one very tentative reading would be LAK-[K'IN]-CH'EEN spelling lak'in ch'een for “eastern holy place” or “eastern city.” This is followed by CH'AB-ya for [u]ch'abiiy, “it has been her/his/its penance/creation,” in Block pA4—a common reference to the king's generative auto-sacrifice required to enable the divine presence, presumably the one mentioned in the previous sentence (Stuart Reference Stuart and Scarborough2005). Block pB4 provides further contexts with 12-TZ'AK-TUUN, which seems to omit a preposition for [ti/tu] lajcha’ tz'ak-tuun, “in her/his/its twelve stone-gathering(s).” A similar expression occurs as a title on a late sixth-century stucco frieze on Building A at Holmul (Figure 3c, Block X), where it refers to one's age in years as 20-TZ'AK-TUUN-li-a for winik tz'ak-tuunila’, “the person of twenty stone-gatherings” (Estrada Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada Belli and Tokovinine2016). The implication is that the text on the stela refers to the ceremonies marking the completion of the 12 years of a 20-year period (k'atun). Dedicating a stela for the first 12 years of a k'atun is very rare, but there is at least one other case relatively nearby: Stela 9 at Lamanai was dedicated in 9.9.12.0.0 or AD 625 (Closs Reference Closs1988).

The protagonist's name is spelled in Blocks pA5 and pB5 as MUWAAN BAHLAM (muwaan bahlam, “hawk jaguar”). It is not accompanied by any title, although the preceding passages are consistent only with rituals undertaken by royalty. An identical name appears on Yaxchilan Lintel 11 (Figure 3d) in a passage that lists captives taken by the second ruler of the site, whose reign began some years after AD 359 and ended in AD 378 (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008; Mathews Reference Mathews1997). Muwaan Bahlam could have been a namesake, but the timing of the Yaxchilan reference is close enough to Chochkitam Stela 3 to consider the possibility that it was the same person.

The rest of the inscription on the stela contains part of a parentage statement introduced by y-une[n], “his son of father,” in Block pA6, followed by what looks like an uncommon variant of the logogram YOPAAT in Block pB6, which is likely the first half of a name that could look something like Yopaat Bahlam. The rest of the inscription would be on a now missing lower fragment.

In summary, the imagery and text on Stela 3 provide the first glimpse of Classic Maya kingship at Chochkitam. Curiously, even though the iconography and rhetoric of the monument conform to royal monuments, there is a conspicuous absence of royal titles in the narrative. The style hints at a possible link to Tikal at a time of intensified interaction with Teotihuacan. The fact that Muwaan Bahlam of Chochkitam potentially ended up as a captive at Yaxchilan highlights the complexity of the political landscape of that period.

The next dataset clarifying the position of Chochkitam in the Classic Maya world comes from the North Group, the second largest ceremonial complex at the site and a major focal point of royal activity during the Early Classic period. In 2021, our excavations focused on the central pyramid (Str. 105, Figure 2). Here, looters had penetrated Early and Late Classic construction phases, including an intact structure composed of two gallery-style rooms. The western section of the northern room was occupied by a tall bench. On the exterior, we exposed 5 m of the western half of the north side and a 1 m section of the western side, adjacent to the northwest corner (Figure 4a) and revealing a carved frieze. Unfortunately, its uppermost section had been truncated in antiquity by a later floor.

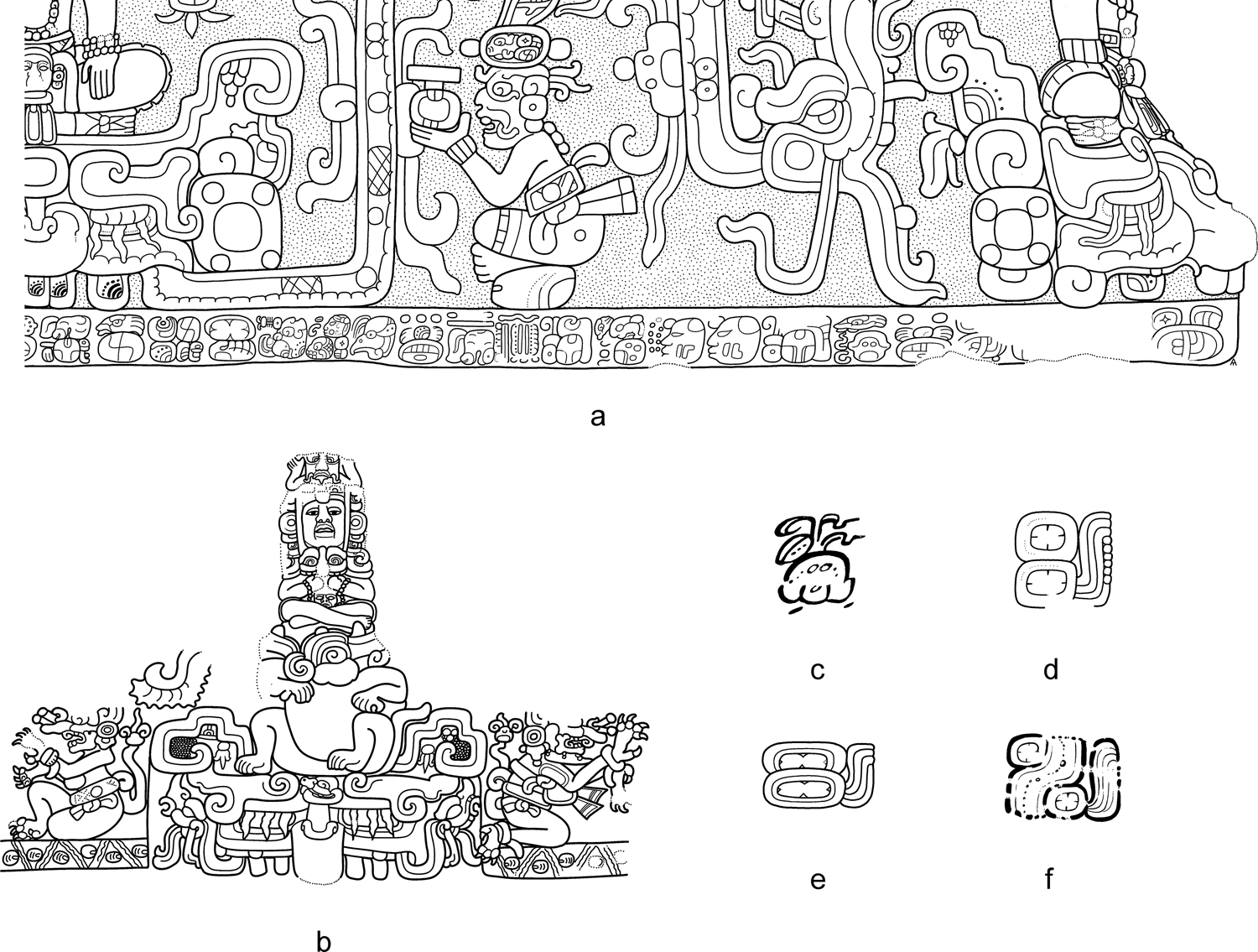

Figure 4. Chochkitam stucco frieze: (a) excavation profile showing its location; (b) northern side; and (c) western side (drawn by Alexandre Tokovinine and Cesar Enriquez).

The frieze features WITZ mountain spirits shown as heads with open mouths and stone-like teeth (Figure 4b). The excavations exposed the mountain head on the northwestern corner and part of the mountain in the center of the composition. Large serpent heads are depicted next to the mountains; the heads are facing each other, toward a large anthropomorphic figure kneeling before the central mountain. A smaller flying or suspended human figure appears between one of the serpent heads and the earflare of the corner mountain. The lower part of a torso of a seated human figure (up to just above the belt level) is visible on top of the corner mountain.

The composition resembles friezes on Early Classic temples, including those at Xultun (Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Hurst, Rossi, Castillo and Saturno2012), Holmul (Estrada Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada Belli and Tokovinine2016), and Balamku (Baudez Reference Baudez1996; Boucher and Dzul Góndora Reference Boucher and Góndora2001). The Holmul (Figure 5a) and Balamku (Figure 5b) imageries are strikingly similar and are interpreted as a representation of royal apotheosis: a deceased king rises (reborn) as the sun seated on the central mountain, flanked by his ancestors or gods on the other mountains, with the kneeling lesser spirits possibly corresponding to stars (Estrada Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada Belli and Tokovinine2016). Just as in the Holmul example, the Chochkitam frieze features an inscription along the cornice at the bottom of the pictorial scene (Figure 4b and 4c).

Figure 5. Comparative context of the Chochkitam stucco frieze: (a) detail of stucco frieze, Building A, Group II, Holmul (redrawn from Estrada Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada Belli and Tokovinine2016:Figure 4a); (b) detail of stucco frieze, Structure 1A, Balamku (redrawn from Estrada Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada Belli and Tokovinine2016:Figure 5a); (c) detail of a codex-style vessel (Los Angeles County Museum of Art M.2010.115.1 / K6751; drawn from a photograph by Alexandre Tokovinine); (d) detail of Nakum Stela 2 (redrawn from Źrałka et al. Reference Źrałka, Helmke, Martin, Koszkul and Velasquez2018:Figure 19a and a photograph by Raymond Merwin on file at the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, 2017.1.92.36); (e) detail of Naranjo Altar 2 (redrawn from Grube Reference Grube2004:Figure 13); (f) detail of the Komkom vase (redrawn from Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Hoggarth and Awe2018:Figure 25 by Alexandre Tokovinine).

The eyes of the mountains on the Chochkitam frieze differ from the standard WITZ logogram or iconography (see Figure 5a and 5b) and are likely conflations with the inscribed glyphic spellings of toponyms. The central mountain appears to be Och Witz, “Enter/Entrance Mountain.” The corner mountain has the “shiny” eyes of the Sun God, so it is probably K'i(h)nich Witz, “Searing Mountain.” The supernatural geography implied by these names is consistent with visual and textual references in Early Classic funeral contexts, such as paintings inside the royal tombs at Rio Azul (Acuña Reference Acuña, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2015). Given that the examples at Xultun, Rio Azul, and Holmul are all relatively close spatially and chronologically to the Chochkitam frieze, they may be manifestations of the same set of beliefs centered on the fate of the ruler after death.

The surviving part of the hieroglyphic inscription (Figure 4b) begins with an isolated section in Blocks pA–pD that contains the end of the Lunar Series (C, X5, and the length of the lunar month as 30 days) and the solar year date. Of the latter, a coefficient of 15 is visible, but the rest of Block pD is largely gone. The missing section covers the remaining part of the main clause, which includes all the predicate and the agent's name. The secondary clause begins in Block pF with a relational ukabaaj (“she/he/it is/was commanded by”), which is a common way of referring to one's subordination in Classic Maya texts.

The name of the overlord is spelled in Blocks pG–pJ as K'AHK’ TI’ CH'ICH’ K'UH ka-KAAN a-AJAW for k'ahk’ ti’ ch'ich’ k'uh[ul] kaan[u'l] ajaw, “K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’, holy Kaanu'l lord.” There can be no doubt that this is the same Dzibanche ruler as the one identified by Martin and Beliaev (Reference Martin and Beliaev2017). Although in the previously known examples of the name all the graphemes were squeezed into a single glyph block (Figure 5c), the new example leaves no doubt that CH'ICH’ is a separate grapheme and not one of the X-in-a-mouth signs. The last block in the sequence (pK) is harder to interpret because it contains a complex conflation. Part of it seems to be KAL-ma for an underspelled kaloom[te’]. The other part consists of two stacked sun disks. Some Late and Terminal Classic inscriptions such as Nakum Stela 2 (Figure 5d) and Naranjo Stela 2 (Figure 5e) use the same combination of stacked sun disks to spell elk'in/lak'in, “east(ern).” A version on the Komkom vase (Figure 5f) shows two sun discs separated by a water stream, implying that it is really a distinct allograph of a glyph ELK'IN or LAK'IN for “east.” “East(ern) kaloomte’” would then be the translation of the block.

On the western side, below the corner WITZ mountain head, was another section of the inscription with a few signs still in situ (Figure 4c). The first block (A) contains the so-called initial series introductory glyph (ISIG) with an embedded sign for the patron Chuwaaj (“Jaguar God of the Underworld”) of the solar year month of Uo (Ihk’ At). As implied by its designation, the ISIG occurs at the beginning of texts where it introduces Long Count dates. However, the presence of the Lunar Series on the northern side of the frieze implies that there was at least one more Long Count date in the narrative. There are examples of inscriptions with multiple Long Count dates such as the text on Tikal Stela 31 (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:Figure 52b). Therefore, it is unclear whether the narrative on the Chochkitam frieze began on the western side and ended on the northern side or began elsewhere and continued on the northern and western sides.

Returning to the inscription on the western side, Block B should contain a count of 400-year periods. Yet the block is so damaged that only a single dot remains. A count of twenty-year periods would follow in Block C, but it is largely gone except for a lower corner of *WINIK.HAAB. The last remaining block (D) is preserved well enough to discern that it contained a count of 14 years (14-HAAB-ba, chanlajuun haab). If we assume that the date falls after K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich's accession to the office of kaloomte’, the best match would be *9.*6.14.X.X, or AD 568. If one accounts for the solar month patron, the date would be *9.*6.14.*5.*7 *8 *Manik *15 Uo, or April 4, 568. That seems to be in agreement with the Lunar Series and with the coefficient of the solar month on the northern side, but the remaining part of the month glyph itself does not look like Uo. Given that there is no indication that the same Long Count date was repeated twice, there are not sufficient data to reconstruct the date on the northern side using the information on the western side. It is not uncommon, however, for Classic Maya inscriptions to begin and conclude with the same pivotal event. Given the earlier mentioned similarities to Holmul Building A, that event would be the dedication of the temple, ceremonies, or both around the burial of the temple's occupant and the accession of the next king. Therefore, assuming that the Long Count date on the western side corresponds to the beginning of the text, the Long Count at the end of the text on the northern side may refer to something that happened in the same year. For example, it could be 9.6.14.14.7 6 Manik 15 Zac, or October 21, 568. This date is separated from the first one by nine 20-day solar months, a number with possible ritual significance.

In summary, the Chochkitam frieze evokes the theme of royal apotheosis and belongs to a set of similar monuments from the region. The inscription contains at least two Long Count dates, one of which is preserved well enough to establish that it corresponds to AD 568. The name of the local protagonist is gone, but he was apparently commanded by the Dzibanche ruler K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ carrying the title of “holy Kaanu'l lord” and “East(ern) kaloomte’.” This implies that by AD 568 Chochkitam had been incorporated into the Kaanu'l hegemony. The fact that K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ was in charge as late as AD 568 conforms to the corulership hypothesis outlined earlier. This is also the earliest known occurrence of the “East(ern) kaloomte'” title. Later rulers in the region such as Til Man K'inich of Altun Ha’ around AD 584 (Helmke, Guenter, et al. Reference Helmke, Guenter and Wanyerka2018) and possibly a ruler of Lamanai in AD 625 claimed the title (Closs Reference Closs1988). It reemerged in references to Kaanu'l lords during the post–AD 751 twilight of the hegemony in the texts at Yaxchilan (Martin Reference Martin2020). Considering the text on CKT Stela 3 discussed earlier, it seems that Dzibanche and Chochkitam were both placed in the “east” of the Maya world along with sites such as Altun Ha’ and Lamanai. Consequently, the title of “East(ern) kaloomte’” implied a more localized domain. The fact that it was in use in AD 568 shows that Dzibanche-based hegemons were still perceived as “eastern,” despite their victory over Tikal and their decisive push into Campeche and Central Peten. It is possible that later use of this title by Altun Ha’ and Lamanai reflected competition for a second-tier regional hegemony within the larger Kaanu'l system.

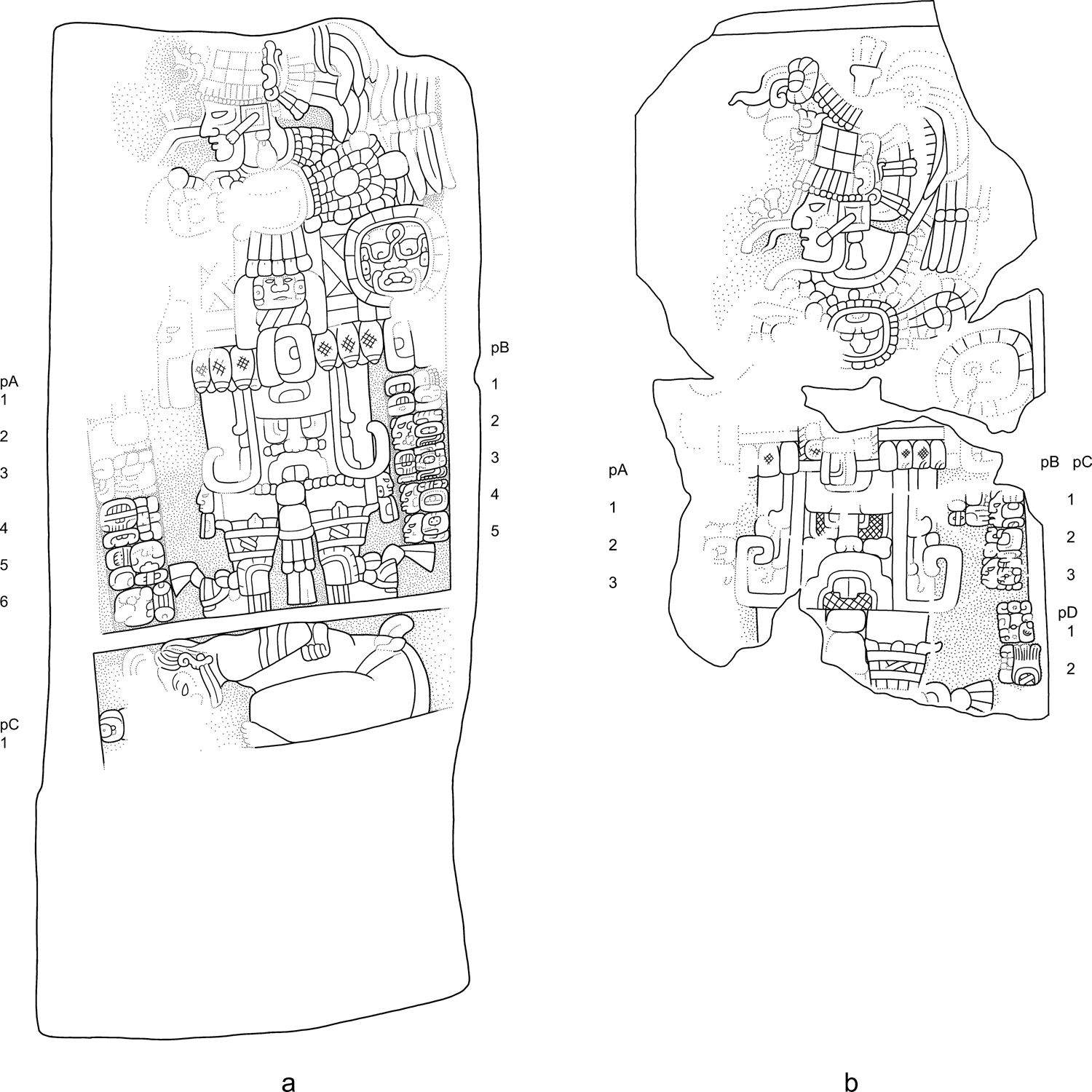

The discovery of a Late Classic tomb and Stelae 1 and 2 at Chochkitam has revealed the third stage in the transformations of the political landscape around the site: it occurred when the Kaanu'l hegemony had withdrawn from the region and smaller polities were left to gravitate toward local power centers such as Xultun in Chochkitam's vicinity. We found Stela 1 (Figure 6a) in front of Structure I at the north end of the Main Plaza, where Frans Blom had photographed it (Morley Reference Morley1937–1938:Vols. 1 and 5). Next to it were several other fragments. Just to the east of it were remains of an altar wrapped in the roots of a large tree. A few meters to the south were the remains of a second, smaller plain altar. Two other fragments were identified as the central portion of a second carved stela (Stela 2, Figure 6b). Directly in front of Stela 1 was a looter's tunnel that penetrated deep into the core of Structure I, reaching a large, vaulted tomb, carved into bedrock at the geometric center of the structure and unfortunately completely empty.

Figure 6. (a) Chochkitam Stela 1 and (b) Stela 2 (drawn by Alexandre Tokovinine).

The main scene on both monuments (Figure 6) consists of a profile of a standing figure of a ruler. The basal register of Stela 2 has not yet been recovered, but the one on Stela 1 shows a captive with arms tied behind his back (Figure 6a). The ruler's costume in the scenes is nearly identical and unequivocally highlights his royal status. He wears a mask and a headdress of the deity Yax Chiit Juun Witz’ Naah Kaan (Coltman Reference Coltman2015) with the Yop Huun (“Jester God”) royal jewel (Stuart Reference Stuart, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2012). He carries a shield with the face of the Jaguar God of the Underworld on his left arm. The ruler's right arm on either monument is eroded, but judging from the available space, it once held K'awiil—the essence of kingship (Martin Reference Martin2020). A belt with ancestral heads and a chest pectoral complete the attire.

The calendrical part of the inscriptions of both stelae is eroded beyond recognition. Nevertheless, the composition of the monument, style of the carving, and paleography of the hieroglyphs can be securely placed in the second half of the eighth century. They are very similar to Xultun Stelae 23, 24, and 25 dedicated by Queen Yax We'n Chahk in AD 761–780 (Rossi and Stuart Reference Rossi and Stuart2020; Von Euw and Graham Reference Von Euw and Graham1984). The synharmonic orthography (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart, Robertson and Ruíz1998) of K'AWIIL-li in Block pC2 on Stela 2 (Figure 6b) is typical of late eighth-century texts.

The inscriptions on the two monuments are organized in a similar manner: a column in the upper right, a continuation in the lower left, and a third column in the lower right corner of the scene (Figure 6). Given the size of the preserved glyphs, it is likely that the eroded initial sections contained a Calendar Round date followed by a single dedicatory statement. The lower-left column would report the name of the protagonist. It is almost entirely eroded on Stela 2 (Figure 6b), but its version on Stela 1 (Figure 6a) is relatively legible, with the exception of the first two blocks: (pA3) a-ha-la (pA4) CHAN-na K'INICH (pA6) sa-ku WINIK-ki (pA6) ch'o-ko . . . ahal chan k'inich saku[n] winik ch'ok, “Ahal Chan K'inich, older brother youth.” The presence of the ch'ok (“youth”) epithet could indicate junior status. However, in the inscription on the Palenque Palace Tablet (Blocks K7-L11), ch'ok is part of the “elder brother” title and is not a reference to one's social or biological youth (Sergei Vepretskiy, personal communication 2022). As with other Chochkitam texts, no emblem glyph follows the personal name. That name consists of a perfect participle ahal “awakened” (see Smailus Reference Smailus1975) followed by chan “sky” and k'i(h)nich “searing [lord]” (Sun God), resulting in a theophoric name phrase evoking the Sun God of the east: “the Searing [Lord] is awakened [in] the sky.”

The third (lower-right) column on both stelae begins with an enigmatic expression. Its version in Block pB1 on Stela 1 (Figure 6a) reads as u-CHIIT ?-K'UH-K'AL-li uchiit k'al- . . . k'uhuul, “her . . . god raising.” The matching section in Block pB1 on Stela 2 (Figure 6b) is more damaged, but one can discern CHIIT-ta and a better-preserved K'AL in the same position as on Stela 1. The element above K'AL appears similar to -ni on Stela 2, but the example on Stela 1 shows that it is closer to the K'UH “water group” element. There are two alternative explanations of chiit k'al-k'uhuul. It could be an otherwise unique parentage expression, or it could refer to ritual activity undertaken by someone who accompanied the ruler but who was not represented in the scene. The second interpretation seems more plausible because of a similar statement on Stela 24 of Naranjo (Graham Reference Graham1975), in which a bloodletting ritual undertaken by Queen Wak Jalam Chan Lem (“Lady Six Sky”) is described twice—as uk'al-mayij, “her gift raising,” and as ubaah ti yax k'uh, “her image with a new/fresh god”—and then depicted as Queen Wak Jalam Chan Lem standing with a bowl of her bloodletting offering. Therefore, k'al-k'uh(uul) may evoke the same act as k'al-mayij: it is about generating divine presence or essence (k'uhuul) through a blood offering (mayij).

As in the case of Naranjo Stela 24, the protagonists of the bloodletting ritual on CKT Stela 1 and 2 texts are queens. The nominal phrase on Stela 1 (Figure 6a) looks like a string of titles: (pB2) IX-OCH-K'IN-ni (pB3) CHAN-na yo-?YOON-ni (pB4) IX-TZOL (pB5) IX-?-?, ix-ochk'in chan yoon ix-tzol ix- . . . , “Lady yoon/yok'in of the western sky, Lady who aligns, Lady . . .” (see Stuart [Reference Stuart2014] on TZOL). The title combining yoon/yok'in, “sky” (sometimes “sky house”) and cardinal directions seems to be reserved for major royal families placed near the boundaries of the narrator's perceived landscape. For example, Copan rulers were called the “yoon/yok'in of the southern sky house” (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013). Therefore, the text refers to a noble woman—the king's mother or spouse—who originated near the western edge of Chochkitam's network. If the text on Stela 2 refers to the same queen, then the nominal phrase helps clarify her identity: pC1) IX-?-ba-li (pC2) K'AWIIL-li (pC3) IX-SUUTZ’-?-AJAW, ix . . . baal k'awiil ix suutz’ ajaw, “Lady . . . baal K'awiil, the Queen of Suutz.’” The Suutz’ toponym of the queen's emblem glyph corresponds to the archaeological site of Naachtun (Cases and Lacadena García-Gallo Reference Cases, García-Gallo, Nondédéo, Hiquet, Michelet, Sion and Garrido2015; Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, García-Gallo and Martín2019). Naachtun was part of the Kaanu'l system and then emerged as a major regional network node after its decline (Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Sion, García-Gallo, Cases Martín, Hiquet, Harada, Chase, Nondédéo and Arnauld2021). Previous investigations of Naachtun Late Classic ceramic data suggested a connection between Rio Azul and Naachtun (Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, García-Gallo and Martín2019). It appears that Naachtun's network extended farther east to Chochkitam.

A significant inscribed vessel came from the first unlooted burial from Chochkitam that was found in a looters’ trench in the Southwest Group. Not much remains of the upper structure of the pyramid, but within its core was a dense layer of ceramic fragments, many of which were from polychrome vessels. Fortunately, the looters stopped their excavation at this point. Below the layers of blackened ceramics was a thin layer of small chert flakes. Below this layer were limestone slabs capping a cist cut into bedrock (Figure 7). Within it, was an extended individual with the head to the west, four ceramic vessels, and two carved jade earflares. The vessels included a Palmar Orange polychrome bowl decorated with quincunx motifs, a small Chinos Black on Orange polychrome bowl decorated with fleur-de-lis, a Cabrito Cream polychrome tripod plate featuring a seated figure on the interior, and a Zacatel Cream Panela variety polychrome vase (CHO.L.09.11.02.02, Figure 8). That vase's iconography includes a repetitive flowery “solar path” motif (Taube Reference Taube, Vail and Hernandez2009) with cloud scrolls. Stylistically, it has close parallels with a group of polychrome vases belonging to Xultun's Queen Yax We'n Chahk. Previous investigations of similar ceramics dealt almost exclusively with looted vessels (Krempel et al. Reference Krempel, Matteo and Beliaev2021). This is the first case of an inscribed Zacatel Cream Panela variety polychrome vase near Xultun with archaeological provenience.

Figure 7. Profile drawing of the CHO.L.09 looter's trench containing the undisturbed tomb at Chochkitam (drawn by Enrique Zambrano) and photo of artifacts (taken by Berenice Garcia). (Color online)

Figure 8. Zacatal Cream Panela variety vase (CHO.L.09.11.02.02) from Chochkitam (photo by Francisco Estrada-Belli). (Color online)

The dedicatory text on this vase (Figure 9a) is slightly damaged but remains mostly legible: (A) a-AL-ya (B) T'AB-yi (C) yu-k'i-bi (D) ka-ka-wa (E) u-BAAH-li-AAN (F) ti-li-wi (G) CHAN-na YOPAAT (H) a-ha-la (I) CHAN-na K'INICH (J) ?1 ?K'AY ?AHK (K) ba-ka-ba, alay t'abaay yuk'ib [ta] kakaw ubaahil aan tiliw chan yopaat ahal chan k'inich juun k'ay ahk ba[ah] kab, “Here goes up the cup for chocolate of the impersonator of Tiliw Chan Yopaat, Ahal Chan K'inich, Juun K'ay Ahk, the principal [on] land.” The inscription highlights the vase's special function—to be used only during a concurrence (ubaahil aan) between the human owner and a manifestation of the storm god Yopaat: “Yopat burns in the sky” (tiliw chan yopaat). Although many royal theophoric names include Yopaat, this is a rare theonym designating a specific manifestation of this deity.

Figure 9. Texts on Chochkitam ceramics: (a) Zacatel Cream vase, Chochkitam; (b) detail of a Zacatal Cream Panela variety vase (Museum aan de Stroom, Antwerpen, MAS.IB.2010.017.084; drawn from Kerr Reference Kerr1989:116, K1837); (c) vessel fragments, Chochkitam (all figures drawn by Alexandre Tokovinine).

The personal name of the king appears in Blocks H and I after the impersonation statement. The first part—Ahal Chan K'inich—indicates that the owner of the vase is the same person as the protagonist of CKT Stela 1; however, we believe that the person buried with it was probably a close relative who may have received the vase as a gift because the king is likely to have been buried in the looted tomb in Structure I, facing his stelae. Block J contains another appellative that seems to function as a secondary name and not as a title. The Juun K'ay Ahk reading is very tentative given the unusual shape of the scroll with a dot coming out of the turtle logogram's mouth. As with other instances of Chochkitam rulers’ names, there is no emblem glyph but instead a common title of high nobles and royalty: baah kab, “the principal [on] land.”

A looted Zacatel Cream vase of the Panela variety (Kerr Reference Kerr2021:K1837) also mentions Ahal Chan K'inich Juun K'ay Ahk as its owner (Figure 9b), and it is very likely that the vase was painted for the same ruler of Chochkitam. Yet another example of that name occurs on a sherd of a Juleki Cream polychrome vase excavated in a layer above the Chochkitam tomb (Figure 9c): . . . -bi . . . -ha-CHAN-na K'IN-ni-chi, [yuk’]ib . . . [a]ha[l] chan k'inich.

The name phrase on K1837 features two additional titles: (L) 13-tzu-ku (M) 20-11 (N) ?, huxlajuun tzuk winikbuluk . . . ,“Thirteen Divisions, thirty-first . . .” The “Thirteen Divisions” title indicates that Chochkitam was part of a regional group of Maya polities also known as “Thirteen Gods” that included Xultun, La Honradez, Altun Ha, Tikal, and Motul de San Jose (Beliaev Reference Beliaev and Robert-Colas2000; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013). Ahal Chan K'inich was apparently the thirty-first ruler of Chochkitam. An undeciphered logogram in Block N of the inscription on the K1837 vase must be the proper royal title of Chochkitam rulers; this is yet another example of a non-emblem glyph dynasty (Houston Reference Houston1986). The relatively high number of successions (31) may be contrasted to more modest counts of kings of the dynasties tracing their foundation to the Early Classic political order. For example, Ahal Chan K'inich's contemporaries at Yaxchilan only counted 15 or 16 predecessors (Stuart Reference Stuart2007).

Although the vase excavated at Chochkitam (CHO.L.09.11.02.02) and the looted vase (K1837) apparently belonged to the same local ruler and the same Panela variety of Zacatel Cream ceramics, the stylistic and paleographic differences between them (compare Figure 9a and 9b) are much greater than what might be expected from a single workshop under the patronage of Queen Yax We'n Chahk, as previous investigations suggested (Krempel et al. Reference Krempel, Matteo and Beliaev2021). K1837 is stylistically much closer to the vessels with the names of Xultun rulers, implying that Xultun potters were commissioned to make it, a gift-labor practice attested elsewhere (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2016). The Chochkitam vase, in contrast, was probably produced at a local workshop. The Juleki Cream sherd with Ahal Chan K'inich's name does not look like any item that could be produced at Xultun and Chochkitam. A Rio Azul workshop is the likeliest source for this polychrome pottery (Adams Reference Adams1999), although there is also an unprovenanced vessel painted in the same style (Kerr Reference Kerr2021:K7524) that names a ruler of Los Alacranes who belonged to the same regional collectivity of Ho’ Pet Hux Haab Te’ (“The Five Provinces [of] Huux Haab Te’” or “The Five Provinces [and] Huux Haab Te’”; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013). Therefore, Ahal Chan K'inich of Chochkitam owned vessels made by his own artists and by potters commissioned from Xultun and Rio Azul and/or Los Alacranes.

Chochkitam and the Expansion of the Kaanu'l Kingdom

The sixth-century Chochkitam frieze suggests a link between Dzibanche and Chochkitam rulers and a possible route connecting them directly. The path generated by our model from Dzibanche to Tikal leads through Chochkitam after passing near La Milpa (Figures 1 and 10), whose dynasty experienced disturbance in the late fifth century (Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Gair Tourtellot and Clarke1996). After Chochkitam, the route leads into Xultun and then Tikal. This would suggest that, for the Kaanu'l armies to arrive at Tikal through the shortest route, Xultun and Chochkitam had to be secured as allies.

Figure 10. Map of hypothetical least-cost routes from Dzibanche to Tikal, Naranjo, La Corona, Caracol, and El Peru that avoid wetlands (drawn by Francisco Estrada-Belli; terrain data from NASA SRTM).

Our GIS analysis suggests that an optimal route to Naranjo that avoided low-lying areas would not have included coastal navigation from the Chetumal Bay to the Belize River, as we might have assumed. Likely, this water route would have been an impractical way to move a large army. Instead, a more direct route included a march through northern Belize, where it headed for medium-sized centers such as Punta de Cacao and El Pilar (Figure 10). We propose that this hypothetical route through the eastern lowlands led Kaanu'l king Tuun Kab Hix to install the 12-year-old Ajnuumsaj Chan K'inich on the Naranjo throne in AD 546 after conquering all the intervening territories. Evidence from La Sufricaya, where Early Classic dynastic monuments and buildings were desecrated and the dynastic seat moved to Holmul around AD 500–550 (Tokovinine and Estrada Belli Reference Tokovinine, Belli, Marken and Fitzsimmons2015), provides support for this military hypothesis. Similar disruptions in the dynastic sequence just prior to AD 546 are evidenced in the inscriptions at Naranjo (Tokovinine et al. Reference Tokovinine, Vilma Fialko, Martin, Vepretskii, Arroyo, Méndez Salinas and Ajú Álvarez2018).

According to our model, the route to Naranjo was probably used to reach Caracol as well. It would have led through El Pilar and Xunantunich, dependencies of Naranjo, before crossing the confluence of the Macal-Chiquibul Rivers and climbing into the Vaca Plateau toward Caracol. The fact that Naranjo was incorporated into the hegemony by the Kaanu'l in AD 546, before Caracol was (in AD 561), suggests that the Kaanu'l armies also likely advanced from there.

Parallel developments related to the Kaanu'l's advancement southward occurred in western Peten, where their activity as overlords dates to AD 520 at La Corona and AD 544 at El Peru (Canuto and Barrientos Reference Canuto and Barrientos2013; Martin Reference Martin2008). The hypothetical route we propose from Dzibanche to El Peru and La Corona initially follows a similar course as the Tikal one—veering southwest toward a close ally of Kaanu'l, Los Alacranes (mentioning “Sky Witness” in AD 561), and then skirting Rio Azul before veering west toward Preclassic and Classic centers such as Nakbe, Tintal, La Florida, and Achiotal, which were associated with the k'uhul chatan winik (“holy Chatan person”) royals, frequently mentioned in Late Classic texts as close Kaanu'l vassals. The route to El Peru would continue southwest, skirting Uaxactun and El Zotz. We wonder whether massive fortifications recently discovered by lidar along the El Zotz ridges (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováč and Marken2018; Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019) initially protected Tikal from a Kaanu'l army advancing through this territory. The route finally reaches the Rio San Pedro at El Peru. This point marks the beginning of a navigable riverine route to the rich Tabasco plain and to trade connections with Highland Mexico (Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2011:Figure 6.3). In AD 599, the Kaanu'l kings attacked and sacked Palenque after securing support from Santa Elena along the way (Martin Reference Martin2020:347). Perhaps the march toward Palenque also followed this rather direct route instead of taking a longer more northernly path (Figure 1).

Conclusions

Data from Chochkitam contribute significantly to our understanding of the history of the kingdom and of its place in a greater political landscape. The long dynastic count of Chochkitam rulers implies that the royal line traced itself back to Preclassic times. The truly historical record begins with Muwaan Bahlam of CKT Stela 3 sometime in the fourth or fifth century. Muwaan Bahlam's political affiliations are unknown, although the innovative style of the monument implies a link to Central Peten. The increased prominence of Xultun as a key regional partner of Tikal and Caracol indicates that Chochkitam benefited less than its immediate neighbors from the post-entrada order.

That situation apparently changed with the rise of the Kaanu'l dynasty. The Chochkitam frieze inscription explicitly states that Kaanu'l king K'ahk’ Ti’ Chich’ commanded local rulers. K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ is now confirmed to have been alive and active as Kaanu'l's hegemonic ruler in AD 568, six years after the victory over Tikal. This confirms Martin and Beliaev's (Reference Martin and Beliaev2017) identification of him as Ruler 16 on the Kaanu'l dynastic sequence, between Tun Kab Hix and “Sky Witness”; he coruled with the latter for some time. The spatial extent of K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich's network discussed here indicates that he was the true architect of the Kaanu'l expansion. Furthermore, a least-cost route analysis suggests that Chochkitam could have been an important waystation to launch attacks against Xultun and Tikal. It also suggests that all other northeast and central Peten kingdoms on direct routes to distant allies had been secured by the Dzibanche kings before the Tikal war in AD 562.

Chochkitam inscriptions expand our list of royal dynasties, which, like those of La Corona, Rio Azul, and Holmul, had the trappings and ritual obligations of Maya royalty but lacked full royal titles like emblem glyphs. In the case of Chochkitam, Holmul, and Rio Azul, the lack of royal titles seems to be related to distinct local identities and the time depth of these identities, rather than the perpetually subordinate status of the rulers. Chochkitam rulers claimed to be one of the Thirteen Divisions, on par with Tikal, Xultun, and Altun Ha kings.

Finally, Chochkitam inscriptions offer a glimpse of what may be the Classic Maya “east identity” that was clearly shared by other polities in the region, including the Kaanu'l of Dzibanche. It appears that K'ahk’ Ti’ Ch'ich’ still perceived himself as a specifically “eastern” hegemon. At Chochkitam, the “east identity” is revealed in the royal names evoking the east and by distinct ritual practices such as commemorating 12 years of a k'atun with a stela and venerating the Yopaat deity. Chochkitam texts reveal that the boundary between the “east” and the “west” was somewhere west of Xultun and east of Naachtun.

After the gradual withdrawal of the Kaanu'l from the Peten after their defeats by Tikal, Chochkitam became part of a reorganized political landscape. It appears that the dynasties of Naachtun, Xultun, and Rio Azul dominated the new political network. Data from Chochkitam indicate relationships with all the three sites during the reign of Ahaal Chan K'inich, albeit asymmetrical ones, because there are no external references to Chochkitam or gifts from Ahaal Chan K'inich to his Naachtun, Xultun, or Rio Azul counterparts.

Acknowledgments

This research was authorized by Guatemala's Ministry of Culture and Sports (convenio 2019–2021) and supported by grants from the Pacunam, Hitz, Maya Archaeology Initiative, and Alphawood Foundations. Institutional support came from Tulane University and the Middle American Research Institute. The excavations at Chochkitam were carried out by Cesar Enriquez and Enrique Zambrano of Universidad de San Carlos, Guatemala (USAC). Antolin Velázquez (USAC) mapped the site. Berenice Garcia (ENAH) drew the ceramic profiles and ran the lab. Ana Lucia Arroyave (USAC) carried out the ceramic analysis. Jesus Eduardo Lopez took the photographs of the monuments and the stucco frieze, which were subsequently used by A. Tokovinine to create photogrammetry 3D scans. We are grateful to the Sociedad Civil Laborantes del Bosque for allowing work in their concession and the use of their camp and to Consejo Nacional de Areas Protegidas de Guatemala for allowing access to the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Several colleagues, including Dmitri Beliaev, David Stuart, Simon Martin, and Sergei Vepretskii, kindly reviewed various iterations of the article, and we greatly appreciate their insights and suggestions.

Data Availability Statement

Annual archaeological reports are available at https://liberalarts.tulane.edu/mari/research-education/holmul; 3D scans of frieze are at https://skfb.ly/o8XZs; a 3D scan of Stela 1 at https://skfb.ly/oq6pz; a3D scan of Stela 2 at https://skfb.ly/o8YnV; and a3D scan of Stela 3 at https://skfb.ly/o8XZt.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2022.43.

Supplemental Text 1. Methods.