Introduction

In 1922, George Milligan, Professor of Divinity and Biblical Criticism at the University of Glasgow, published a book called Here and There among the Papyri. It was aimed at the interested public, ‘addressed in the first instance to that wide and ever-increasing public who are keenly interested in the study of the New Testament, and are anxious to know more of the bearing of the papyrus discoveries, of which they hear so much, on its language and literature’.Footnote 1 The work represents a first attempt at a synthesis of the significance of the mass of papyri that had trickled into European collections since 1862,Footnote 2 focusing on their significance for New Testament exegesis, questions of canon, Greek linguistics and the social world of early Christianity. Milligan concludes that for the student of early Christianity ‘a rich and fruitful field of investigation lies ready to his [sic] hand in the new discoveries’.Footnote 3

A century on, many corners of this ‘rich and fruitful field’ remain untilled, despite the numerous studies that examined the texts, transmission and scribal habits of the papyri. The overgrown patch that I attend to in this article is one that Milligan overlooked altogether: the question of media, paratextuality and early intellectual engagement with the New Testament. As some of the earliest witnesses to the New Testament, papyri offer glimpses at the way these works were conceptualised by those who read and copied them, how they were enumerated and organised into corpora. Their paratexts reflect the earliest layers of scholarly activity on the works that came to form the New Testament, foreshadowing the developed paratextual systems contrived from late antiquity onward, like the Eusebian apparatus for the Gospels and the Euthalian tradition for the Praxapostolos (Acts and Catholic Epistles) and Pauline Letters.Footnote 4 Most obvious among paratexts in the earliest manuscripts are the titles, the inscriptions (beginning-titles), subscriptions (end-titles) and kephalaia notations (chapter headings) that became attached to the New Testament works.

As features that are the product of anonymous scribes and readers, not of authors, the New Testament's titles reflect readerly engagement with these works, communal perceptions of their content, relationship to other works and the personae affiliated with their production. Unlike modern publishing conventions, titles were flexible components of textual transmission that fluctuated, albeit within a set of traditional boundaries.Footnote 5 The titular tradition grew over time in response to interpretive pressure and in conjunction with changing perceptions of the New Testament as a literary text to be organised. The titles provide raw material by which one might structure the works that came to comprise the New Testament, enabling list-making, content organisation and interpretation of various kinds.Footnote 6

The titles of the New Testament preserved in the papyri inform two ongoing critical discussions that I will focus on in this article. The first concerns the place of material and paratextual features in the emerging digital edition and changing media cultures. As the digital edition slowly becomes a reality, offering scholars greater access to images, transcriptions, metadata and rationales behind editorial decisions, we are beginning to reconsider the boundaries of what features these tools should represent. Paratexts, and especially titles, are at the forefront of this conversation and they point to the complexities that face editors and users of future editions alike.Footnote 7

A second area that this discussion informs is practices of entitling in ancient literature. Multiple studies have explored the dynamics of titular traditions of classical literature, but these studies have only obliquely engaged material from the New Testament and the consequences of such studies have not yet been sufficiently considered by New Testament scholars in terms of thinking about the place of the papyri in the larger reading culture of the eastern Mediterranean.Footnote 8 Analysing all titles in New Testament papyri offers a platform for considering broader trends in the labelling of ancient works in the broader Roman world.

In order to understand this evidence better, I catalogue every form of every title in the 141 papyri currently included in the Kurzgefasste Liste,Footnote 9 using this material to make observations about the place of these manuscripts in the broader context of ancient labelling practices and the significance of paratexts for the emerging editorial agenda. The papyri are not always the earliest evidence for the title, as for example the kephalaia to Luke in P3, which postdate the presence of gospel kephalaia in Codex Alexandrinus, but it is useful to take the papyri as a group because they come predominantly from the same geographic area (Egypt) and because many of the more fragmentary manuscripts that preserve titles have not received significant scholarly attention.Footnote 10 In all, ten papyri preserve a total of twenty-six titles (P3 P4 P26 P46 P61 P62 P66 P72 P74 P75).

1. P3 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Pap. G. 2323, 6–7th cent., diktyon 73498)

P3 is an opisthographic fragment of Luke (recto 7.36–45; verso 10.38–42) that preserves three titles.Footnote 11 Its first editor, Karl Wessely, suggested that the fragment was once a non-continuous lectionary based on thematic parallels of texts arranged there (the woman who wept at Jesus’ feet and the Mary and Martha episode), but without further codicological information it is difficult to make a sure judgement.Footnote 12

The first title to discuss is a kephalaion heading, not an inscription or subscription for the work itself (although it is possible that a further title for Luke's Gospel may have been present at this point). The first two lines of the recto, which preserve parts of Luke 7.36–45, contains the remnants of a kephalaion title for a section of text that runs from Luke 7.36 to 8.3, traditionally denoted as kephalaion 21 (κ̅α̅) in Luke's list of 83 kephalaia: ɛυ]α̣γγɛλιον̣ | [πɛρι της αλɛι]ψα[σης] τον κ̅ν μυρ̣[ω] (‘go]spel | [regarding she who ano]int[ed] the Lord with ointme[nt’).Footnote 13 The upper portion of the recto is damaged, both in terms of lost papyrus and faded ink, but the first line clearly preserves the latter half of the word ‘gospel’ in the nominative or accusative case, possibly the remnants of a running title or a label for Lukan material in a non-continuous manuscript.Footnote 14 The two gammas in the first line are clearly legible, as is the -ιον inflected ending. The second line contains the text of the kephalaion titlos, the latter half of which is well preserved, including the horizontal line above the nomen sacrum. There is an upper margin of about 1 cm above the title.

Competing reconstructions of these two lines have been offered. Wessely's first transcription of the second line of the recto fails to make sense of the textual remains there, reading τον κ̅ ησου (perhaps ‘gospel | the lord Jesus’?).Footnote 15 In 1963, J. Neville Birdsall offered an elegant solution, reconstructing line 2 as the titlos for kephalaia 21, a reading that I have adopted here.Footnote 16 More recently, Stanley E. Porter and Wendy J. Porter have read line 2 of the title as α..ο̣.τονκι̅μ̣.., critiquing Birdsall's reconstruction in three places: the final sigma in αλɛιψασης, the presence of the nu in the nomen sacrum and the presence of upsilon rho in μυρω.Footnote 17 While their more conservative reconstruction reminds us of the underlying uncertainties in working with this material, their observations on letter-forms can be explained by the irregular damage patterns and the irregular hand of the scribe.

Birdsall's reconstruction of the recto also has the benefit of accounting for the two titles on the verso: ɛυαγγɛλιο]ν̣ του αγιου λουκα (‘Gospe]l of Saint Luke’), possibly an inscription, and πɛ]ρ̣ι̣ μ̣α̣ρ̣θας και̣ μαρ[ιας (‘Rega]rding Martha and Ma[ry’), kephalaion 37 (λ̅ζ) to Luke (10.38–42). Apart from ɛυαγγɛλιον, of which only part of the nu remains, the first line of the verso is legible, preserving an inscription to or some other labelling of Luke's Gospel that appears to lack the preposition κατά. No such title is included in the apparatus for the inscriptio in NA28 and this formulation resists an overinterpretation of the κατά + evangelist formula that has characterised some recent arguments, even if the reading and its function in P3 are uncertain.Footnote 18

The text of the third title in P3, the kephalaion titlos in line 2 of the verso, is fairly certain, even though the beginning and end are lost due to damage. The clarity of this formulation supports Birdsall's reconstruction of the kephalaion title in line 2 of the recto.Footnote 19

2. P4 (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, suppl. gr. 1120, 3–4th cent., LDAB 2936, diktyon 53778)

The title in P4 is probably an inscription to Matthew.Footnote 20 It appears on a flyleaf, alongside material from Luke, of a codex that contains two works by Philo. Recycled from a previously disassembled manuscript, it is perhaps the earliest inscription to Matthew's Gospel.Footnote 21 Simon Gathercole dates the Matthew and Luke material to the late-second or early-third century ce.Footnote 22 Following Gathercole's transcription, I read the title as ɛυαγγɛλιον | κ̣ατ̣α μαθ᾽θαιον.Footnote 23 The first epsilon in ɛυαγγɛλιον is slightly effaced but still visible, and the upsilon has a long vertical stroke that extends down to the next line. In the second line of the title, both alphas in κατα are visible (especially the final one), while the kappa and tau are only partially legible: remnants of the tau's vertical stroke are visible and (possibly) the upper vertical diagonal stoke of the kappa. The upper halves of both thetas in μαθ’θαιον are partially abraded.

The spelling of Matthew with two thetas (μαθθαιον) is adopted as the Ausgangstext for the inscription to Matthew in NA28 (ΚΑΤΑ ΜΑΘΘΑΙΟΝ), even though the short form without ɛὐαγγέλιον is preserved in only a few early manuscripts, and even there it is sometimes corrected.Footnote 24 In the titular tradition beyond the papyri, ματθαιον is the predominant spelling.Footnote 25

3. P26 (Southern Methodist University Library, Pap. 1, 7th cent., LDAB 3055)

The title in P26 is another highly fragmentary inscription, this time to Romans, that was found at Oxyrhynchus.Footnote 26 A single opisthographic fragment, it contains parts of Rom 1.1–16, the recto preserving most of the right-hand edge of the column and the verso the left side of the column. On the recto above the first line of text appears the inscription προς ρ]ω̣μαι̣[ους, probably indented from the left margin. The πρός + destination formula for Pauline inscriptions and subscriptions is well attested in the early papyri and majuscule pandect manuscripts, even though more effusive titles develop within the tradition. The three horizontal dashes framing the title (two above and one below) reflect common practices in the papyri and other early manuscripts to separate the titular form from the main text (see the examples from P46 below). There is a slightly larger space between the title and the first line of text, signalling a desire to distinguish text from paratext.

4. P46 (The Chester Beatty, CBP BP ii + University of Michigan Library, Inv. Nr. 6328, 3–4th cent., LDAB 3001)

P46 is a remarkably well preserved codex of the Pauline Epistles and Hebrews. It is probably the earliest instance of a Pauline collection of some kind bound in a single codex, although the Pastoral Epistles are not present. This manuscript has received significant scholarly attention from its first editor, Frederick Kenyon, onward, including careful studies of its text, scribal habits and copious corrections.Footnote 27 Of all the Greek papyri that preserve parts of the New Testament, it contains the most titular formulations, with a total of nine.

προς ɛβραιους. As in P26, the inscription to Hebrews is centred in the column and set apart from the surrounding text (Rom 16.23 above and Heb 1.1 below) by a string of horizontal lines and a paragraphos that extends above the title into the left margin.Footnote 28 A stichometry notation is also present, added by a later hand.Footnote 29

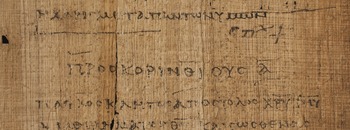

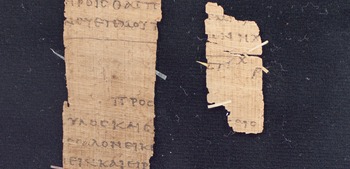

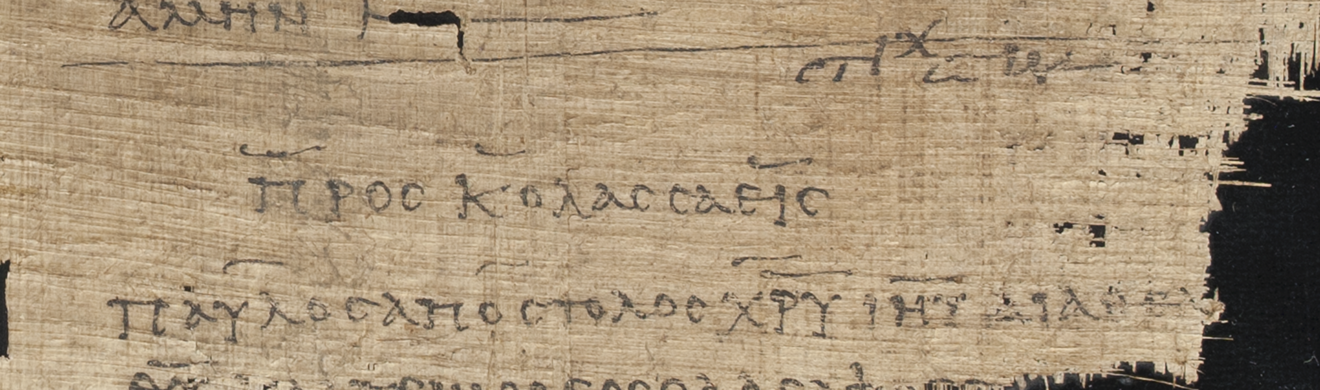

προς κορινθιους α̅ (Fig. 1). The aesthetics and layout of this inscription to 1 Corinthians are identical to the Hebrews inscription: it is centred, distinguished by horizontal lines and a paragraphos, and a stichos notation for Hebrews is present, added by the same second hand.

Figure 1. P46, 38r. Inscription to 1 Corinthians. © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. Photographed by CSNTM (CBL BP ii fol. 38)

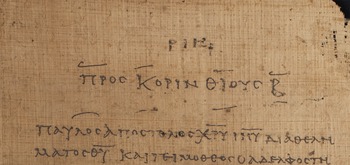

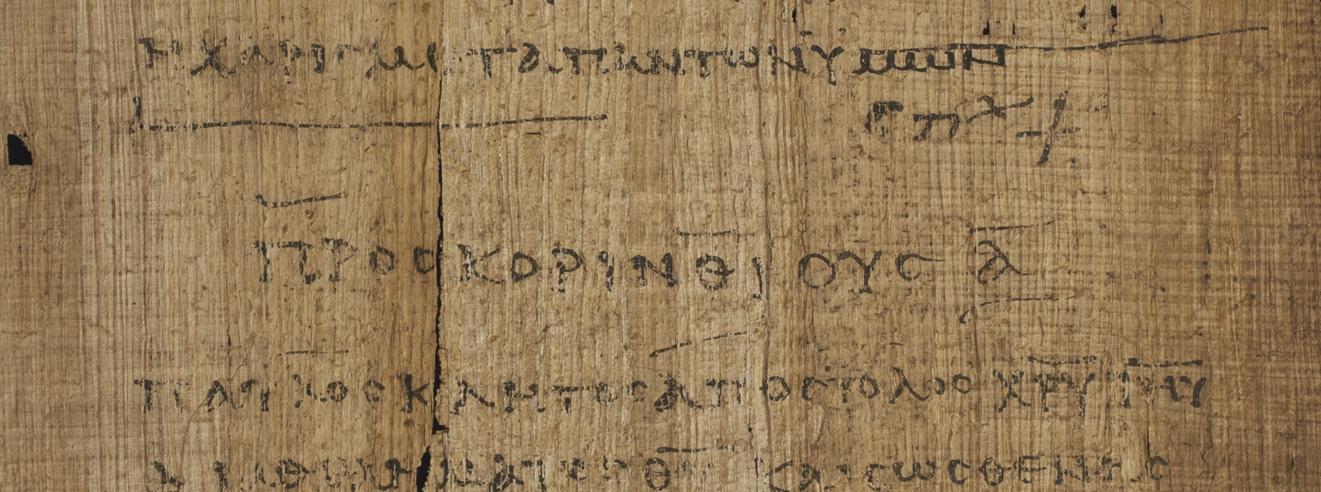

προς κορινθιους β̅ (Fig. 2). This inscription to 2 Corinthians is nearly identical in composition to the other titles in this manuscript, with horizontal lines above and below the title.

Figure 2. P46, 61r. Inscription to 2 Corinthians, with page number (ρ̅ι̅η). © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. Photographed by CSNTM (CBL BP ii fol. 61)

π]ρος κορινθιους | β̅. Although damaged, the text of the subscription to 2 Corinthians, located in the lower margin, is probably identical to the inscription. The only letter of which no trace is present is the pi in προς. The numeral abbreviation β̅ is centred on a second line and the upper curve of the letter is visible, along with the vertical abbreviation bar. Like the inscription, this formulation is separated by horizonal lines above and below the title and by a long paragraphos immediately below the text and above the title.

προς ɛφɛσιους. Ephesians begins on a new folio and the inscription is centred at the top of the page and separated from the text by its justification vis-à-vis the main text and the use of horizontal bars. It is preceded only by a page number (ρ̅μ̅ς).

προς γαλατας. The features of the inscription to Galatians are consistent with the rest of the manuscript. Because Galatians begins about halfway down the folio, a paragraphos is present, along with the horizontal lines, different justification and use of negative space. A stichos notation was added by the same hand that added the other notations at the end of letters.

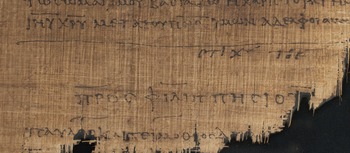

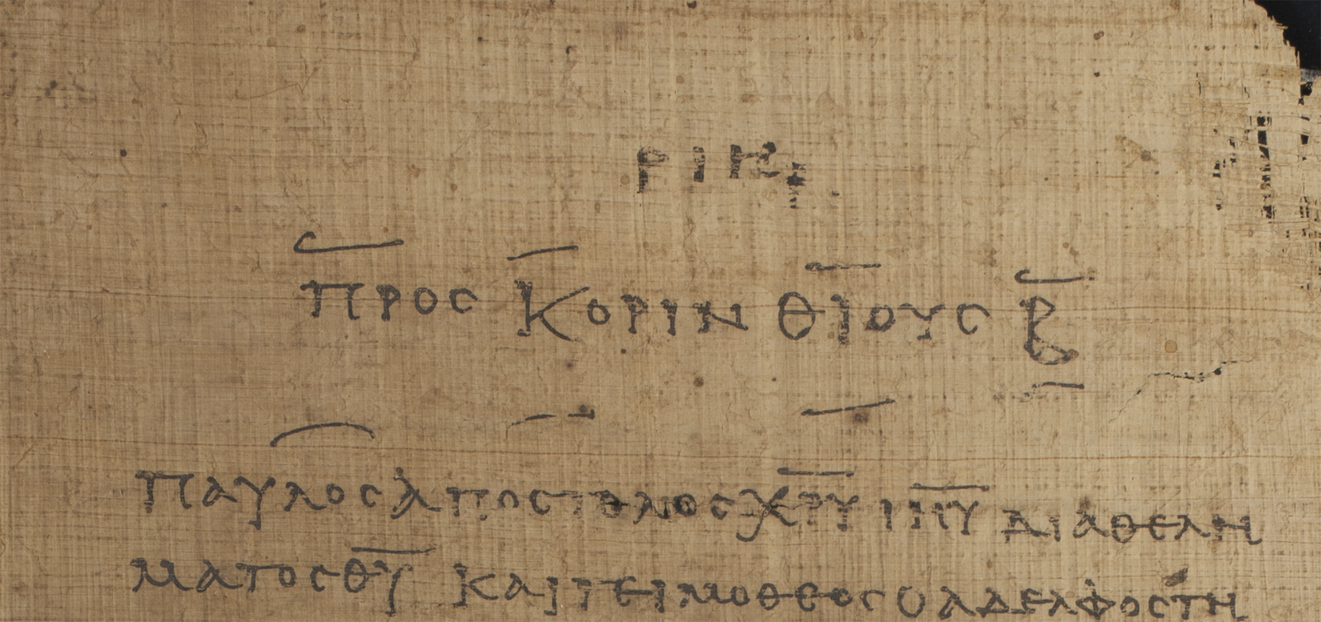

προς φιλιππησιους̣ (Fig. 3). Although the final two letters are partially lost due to damage, the reading remains clear, following the same pattern in text, positioning and separation as the other titles in the manuscript when the title appears amid the column with text from two different works. In this case, the folio preserves the end of Galatians (without a subscription) and the first two lines of Philippians.

Figure 3. P46, 86r. Inscription to Philippians. © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. Photographed by CSNTM (CBL BP ii fol. 86)

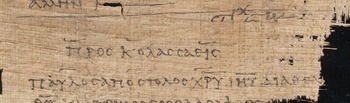

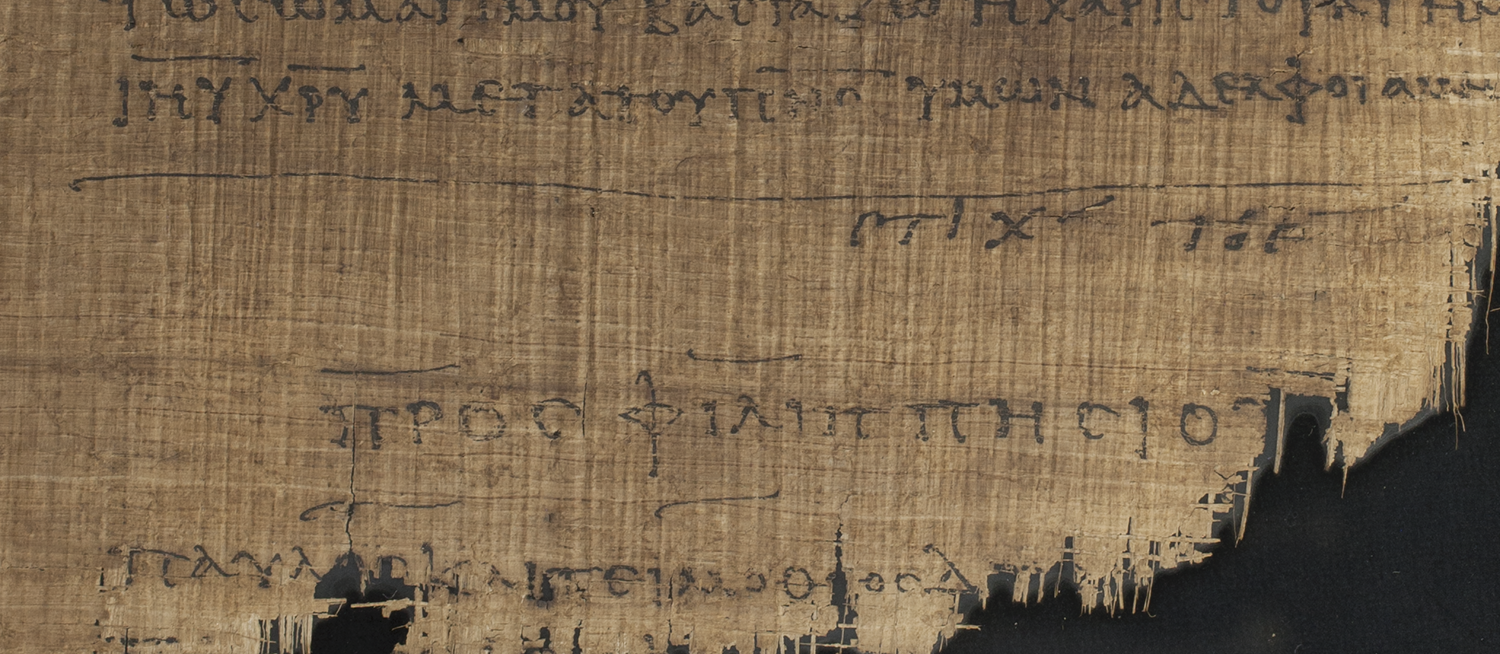

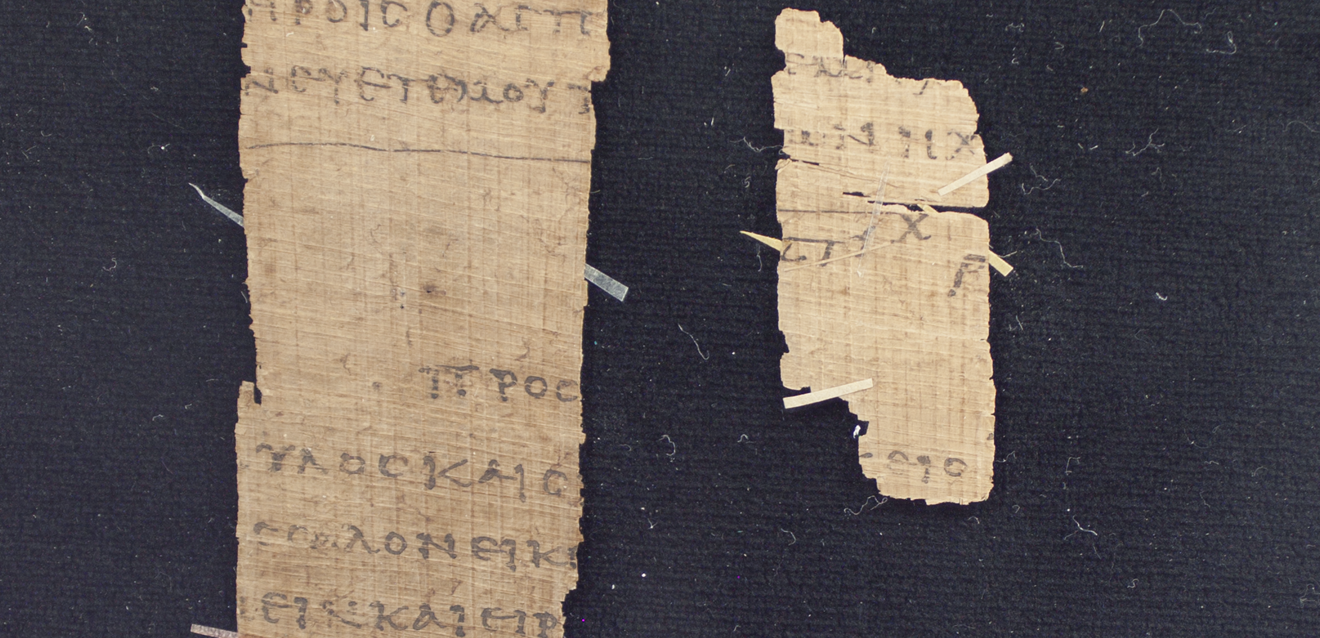

προς κολασσαɛις (Fig. 4). This inscription to Colossians is distinguished from the main text by features standard across the manuscript, especially when two works share the same folio:Footnote 30 negative space, horizonal lines framing the title, a long paragraphos that extends nearly the entire width of the writing block and a secondary stichos notation.

Figure 4. P46, 90r. Inscription to Colossians. © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. Photographed by CSNTM (CBL BP ii fols. 15 & 90)

προς [θɛσσαλονι]κ̣ɛις [α̅] (Fig. 5). The final title in P46 is an inscription to 1 Thessalonians. The προς is clearly visible, along with the upper vertical stroke of the kappa and the final -ɛις. Despite the loss of material, similar separation strategies are present, including the use of negative space after the end of Colossians, a long horizontal line dividing the two works and a secondary stichos notation.

Figure 5. P46, 94r. Fragmentary inscription to 1 Thessalonians. © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. Photographed by CSNTM (CBL PB ii fol. 94)

The composition of titles in P46 is largely consistent throughout what remains of the manuscript, both in terms of the text (πρός + recipient) and separation strategies. Already at this stage, titles are an ingrained part of the tradition and work to simultaneously distinguish one work from another and link the works into a defined sequence through their consistent characteristics. The consistency of the titles creates coherence across a miscellaneous set of occasional letters, using paratexts to construct the Pauline Epistles as a work abstracted from the quotidian realities of letter circulation.Footnote 31

5. P61 (The Morgan, Colt Pap. 5.1–4, 8th cent., LDAB 3063)

The next title also comes from what was once probably a codex of (at least) the Pauline Letters.Footnote 32 P61 contains parts of Romans, 1 Corinthians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon and Titus. The only visible part of any titular form is the subscription to Titus: π̣ρ̣ο̣ς̣ [τιτον. Following the final line of Titus, a line of diplai (>) is visible, distinguishing the main text from the title.Footnote 33 Below this line, the parts of the each of the letters in προς are visible, although the title is difficult to read due to the loss of papyrus and faded ink.

6. P62 (University of Oslo Library, P.Osloensis 1661, 4th cent., LDAB 2993, diktyon 76007)

P62 is a Graeco-Coptic (Akhmimic) excerpted manuscript that contains Matt 11.25–30 and Dan 3.50–5.Footnote 34 The verso of fragment 1 (the recto is blank) includes a title to Matthew with a peculiar spelling: ⲡ]ⲉⲩⲁ[ⲅ]̣ⲅⲉⲗ̣ⲓⲟⲛ | [ⲡⲕⲁ]ⲧ̣ⲁ ⲙⲁⲑⲁⲓⲟⲥ | [ɛυαγ]γɛλιον | [κατα μαθθαιον?]. The situation is complicated by the fact that the scribe's hand is identical for the Coptic and Greek portions of the manuscripts and that Greek usually precedes the Coptic on the other fragments.Footnote 35 If we assume that the title follows a similar pattern to the rest of the manuscript, then we encounter two issues in the text: Matthew is spelled with one theta and in the nominative case following κατά. These two issues probably suggest that the first two lines constitute the Coptic title, followed by a now lost Greek version of the title that began with ɛὐαγγέλιον, part of which is preserved in the third line of text on the fragment below a string of glyphs that follows the second line of the first title.

7. P66 (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, P.Bod. ii + The Chester Beatty, BP xix, 3–4th cent., diktyon 76008)

P66 is a substantial copy of John's Gospel, including the inscription to the work, which is possibly the earliest title for any Gospel: ɛυαγγɛλιον κατα ι̣ωανν̣η̣ν.Footnote 36 The title appears centred in the upper margin of the column, running near to the end of the right margin and separated from the main text by horizonal lines above and below the title (like P46), negative space between the writing block and the title, and the title's centre justification. A small glyph (similar to the > siglum with a horizontal line extending right at the point of the triangle, perhaps a paragraphos) separates ɛυαγγɛλιον and κατα. The title was added by a subsequent hand, but not significantly later.Footnote 37

8. P72 (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, P.Bod. viii + Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, P.Bod. vii, 3–4th cent., LDAB 2565)

P72, the Bodmer Miscellaneous Codex, has received significant scholarly attention due to the order of its works, the importance of their texts and the multiple production layers present in the now disassembled manuscript. Since it was first edited by Michel Testuz, numerous theories have emerged that explain the bibliographic context of a manuscript that preserves parts of the Catholic Epistles (1–2 Peter and Jude) and a series of other works, including Melito's Homily on the Passion (P.Bod. xiii), the Apology of Phileas (P.Bod. xx), 3 Corinthians (P.Bod. x), the Protoevangelium of James (P.Bod. v), the 11th Ode of Solomon (P.Bod. xi) and Ps 33.2–34.16 (P.Bod. ix), produced by various scribes and brought together into a single codex secondarily.Footnote 38 In fact, the codicological relationship between ‘biblical’ material in the manuscript, 1–2 Peter (P.Bod. viii) and Jude (P.Bod. vii) is secondary, a reality that questions the logic of their classification in the Liste.Footnote 39 In any case, a total of six titles are preserved for 1–2 Peter and Jude, an inscription and subscription for each work.Footnote 40

πɛτρου ɛπιστολη α̅. The inscription to 1 Peter appears in the first line of text on the folio, separated from the text of 1 Peter by its justification (centred) and the use of horizontal lines above and below the title. The composition of this title is similar to the aesthetics of the titles in P46, but more informal. A page number (α̅) is preserved above the title.Footnote 41

The text of the subscription to 1 Peter is identical to the inscription: πɛτρου ɛπιστολη α̅. Unlike the inscription, this form is ornamented with a string of diplai/paragraphoi to fill the line it occupies. The subscription is further set off from the main text by two large coronides below it that further frame a colophon which reads, ‘peace to the one who writes and the one who reads’.Footnote 42

The third title in P72 is the inscription to 2 Peter: πɛτρου ɛπιστολη β̅. The text of the title follows a pattern identical to that in 1 Peter. It is distinguished from the main text only by its justification: it is indented in from the left margin and the line is left blank after the numeral abbreviation. The text is the same size as the main text and there are no glyphs or lines to set off the title from the text. A page number appears directly above it (κ̅ γ̅).

As in 1 Peter, the text of the subscription is identical to the inscription: πɛτρου ɛπιστολη β̅. And, like 1 Peter, the design of the subscription is more complex, incorporating two coronides and the colophon. Unlike the 1 Peter subscription, however, the title here is centre-justified on its own line and completely encased in a penwork box.

Moving to Jude, the form of the title text is similar to that of the Petrine titles, but the aesthetics differ, as does the scribal hand. First, the inscription has a correction by the first hand: ιοδα ɛπɛιστολη] ιουδα ɛπɛιστολη. Initially, the scribe omitted the upsilon in ιουδα, placing the missing grapheme above the line between the omicron and delta. Another anomaly that was not corrected is the spelling of ἐπιστολή with a fuller orthography, adding an additional epsilon after the pi.Footnote 43

Unlike the Petrine inscriptions, Jude does not begin on its own folio, following instead the final two lines of Odes of Solomon 11. The title is separated from Odes by a penwork geometric headpiece that traverses the folio and the rest of the line that follows the title is blank, setting off the inscription from the text of the work that follows.

The subscription to Jude, ιουδα ɛπɛιστολη, is identical to the corrected version of the inscription. The subscription occupies its own line, is centre-justified and followed by an irregular penwork tailpiece.

Despite the codicological and bibliographic complexities of the manuscript, the titular traditions in the Petrine letters and Jude follow consistent patterns. The texts of the inscriptions and subscriptions match for each work (if the corrected text of Jude's inscription is considered), a reality that is not always reflected in the titular tradition,Footnote 44 and the subscriptions are given further ornamental emphasis compared to the inscriptions.

9. P74 (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, P.Bod. xvii, 7th cent., LDAB 2894)

A copy of Acts and the Catholic Epistles, preserving parts of each work in the corpus, P74 preserves one titular form: a subscription to Acts on fol. 188: πρ̣α̣ξις [απ]οστ̣ο̣λ̣ων.Footnote 45 The title is distinguished from the main text by a dividing glyph string and small coronides that frame what remains of the formulation. Parts of each grapheme are preserved apart from the alpha and pi in αποστολων, which extend into the break in the fragment below the final line of text. The singular (or defective plural form?) of πραξις, instead of πραξɛις, is unusual but not unattested in the titular tradition. GA 2412, for example, a twelfth-century copy of Acts, Paul and the Catholic Epistles, preserves the damaged title πραξις των [αποστο]λων συγγραφɛις παρα του ɛυαγγɛλιστου λουκα (‘Act of the Apostles, written by Luke the Evangelist’).Footnote 46 Nonetheless, the prevalence of the plural form in the tradition suggests that πραξις in P74 represents a scribal omission of the epsilon (πραξ<ɛ>ις).Footnote 47

10. P75 (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pap.Hanna. 1, 4th cent., LDAB 2895)

P75, renowned in New Testament textual criticism for its supposed early date and close textual affiliation with Codex Sinaiticus, remains an important witness to the early texts of Luke and John.Footnote 48 The manuscript preserves two titles on the folio that the Gospels share (44r): a subscription to Luke – ɛυαγ’γɛλιον | κατα | λουκαν – and an inscription to John – ɛυαγγɛλιον | κατα ιωανην. Immediately following the end of Luke, the subscription appears in three lines, followed by 2–3 lines of negative space that precede the inscription to John, written in two lines.Footnote 49 Noteworthy here is the spelling of John with only one nu between the alpha and eta (ιωανην). Although the predominant spelling for John is ιωαννην in the titular tradition and elsewhere, the shorter spelling certainly exists. For example, the subscription to the book of Revelation in Codex Sinaiticus and GA 386 and the inscription to 1 John in Codex Vaticanus and GA 468 each preserve the spelling without the double nu.Footnote 50 Both spellings co-exist in the main text of P75.Footnote 51 When we set aside these few exceptions, it is no surprise that the editors of NA28 have silently corrected ιωανην to ιωαννην in the apparatus to John's inscription.

11. Conclusion

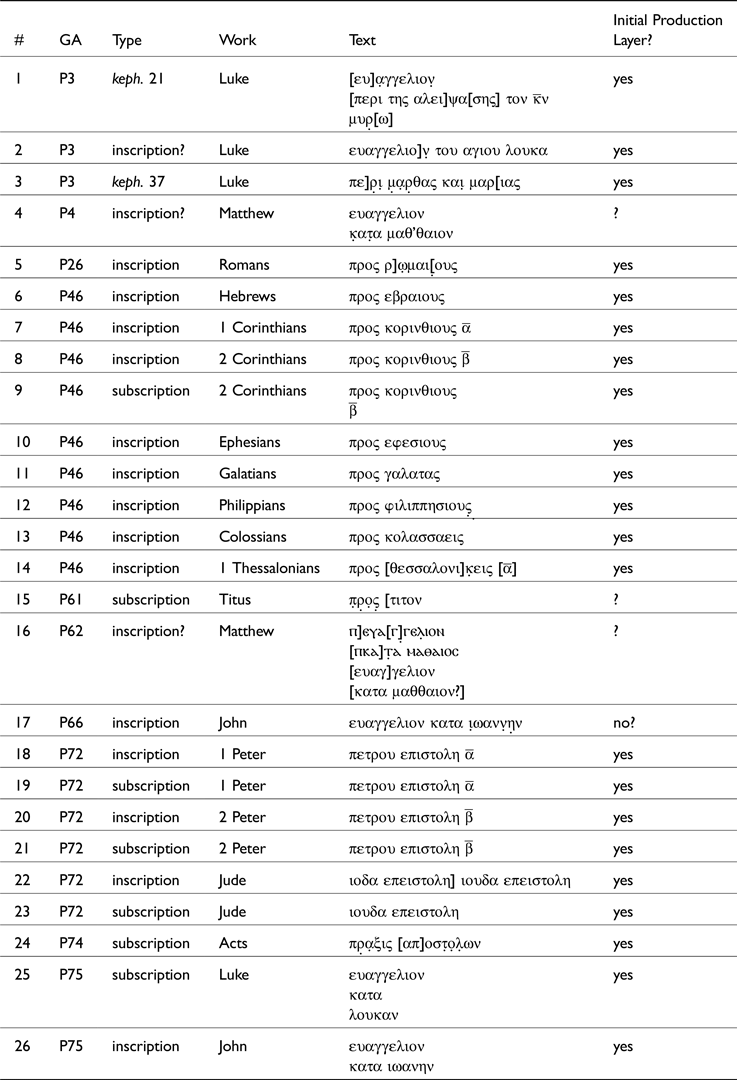

What, then, can we say about the titular traditions of the New Testament in the papyri, as reflected in Table 1, and their value for textual scholarship? The first thing to note is that these titles show that readers were tolerant towards paratextual variation and that scribes did retain some level of freedom to develop paratextual traditions. Even though the texts of these forms tend to be concise and formulaic, offering very little by way of paraphrase or literary content and focusing on letter recipients, attribution and generic designations (letter and gospel),Footnote 52 there are still multiple ways in which titles can vary, including the spelling of proper names (26), corrections within titles (22), orthographic variations that lead to unusual spellings or morphological uncertainty (24), ambiguous bilingualism (16) and titles that deviated from early traditions (2).

Table 1: Summary of Titles in the Papyri

These textual peculiarities pale in comparison with the variety of ways in which the titles are designed and laid out vis-à-vis the main text. In cases where the material is sufficiently preserved, multiple strategies distinguish titles from the texts they label. For example, the two inscriptions to John (P66 and P75) share essentially the same text but are presented in different ways and were added at different stages in each manuscript's history of usage. The title in P66, added by a secondary hand, is centred above the first line of text on a new folio and set off from the gospel text by negative space and horizontal dashes that frame the title. It is composed in one line and preserves a glyph between ɛυαγγɛλιον and κατα. The aesthetics of the inscription in P75 are not wildly different from P66, but notable differences are present. The title in P66 is also centre-justified and framed by horizontal dashes, but it shares page space with the end of Luke. The titles on this folio were also executed by the same scribe who copied the main text. They are pre-planned parts of the first production layer. The early titular tradition of the New Testament is far from unconstrained but numerous textual, aesthetic, scribal and design variables exist that make the titles a continuing locus of change throughout the New Testament's transmission. Among other factors, it is these variables that underwrite the complex titular and paratextual developments which become central to the New Testament's transmission from late antiquity onward.

Within these possibilities of variation, there are also examples of consistent scribal execution, the prime example being the nearly identical inscriptions and subscriptions to the Petrine Letters and Jude in P72, even though they were produced by different scribes. P46 too is largely consistent in its titles, preserving inscriptions for every extant Pauline letter (except Romans, where the start of the work is lost) and following a mostly consistent set of segregation, layout and design techniques. The inclusion of a subscription to 2 Corinthians, the only subscription present in P46, can be explained as a way to fill the end of the folio since the next work (Ephesians) begins on a new sheet. But even in manuscripts where paratexts are largely consistent, variation exists due to bespoke scribal, aesthetic or material issues specific to a particular codex and its contexts of production and subsequent use.

More broadly, this material offers a vantage point from which to compare the production of early manuscripts that preserve the New Testament with other literatures that were copied on papyrus. For example, Francesca Schironi notes that the name Homer (ΟΜΗΡΟΣ) never appears in the titular formulations attached to papyri of the Iliad and Odyssey. Instead, most subscriptions are composed in two lines with the name of the work followed by a book number, located below the final line of text ‘after a significant interlinear space’.Footnote 53 A nearly identical composition of the titles occurs in the Pauline corpus: Paul is never mentioned by name, the only subscription to Paul (2 Corinthians in P46) preserves the book number on a second line, and nearly every title to Paul is separated from the text by negative space and glyphs of various kinds.

Schironi suggests that ‘Homer’ is absent from titles because the ‘the two poems themselves clearly overshadowed that of their author (or authors) for ancient readers … the title alone was sufficient for identifying the work’.Footnote 54 This observation may, at least in part, explain the early forms of the Pauline letters. The scribes responsible for P46 probably viewed Paul's authorship of the letters as an uncontested question, even for Hebrews, which is located between Romans and 1 Corinthians. Explicit identification of Paul in the title is then unnecessary since his name is the first word in each letter preserved in P46 except Hebrews. Nonetheless, it is striking that neither Paul's nor Homer's name is associated in their early titular traditions, even though the names of purported authors of the other New Testament works like the Gospels and Catholic Epistles are entrenched parts of the traditions, as is the case with other classical works such as the writings of Hesiod and many grammarians.Footnote 55 The early forms of titles in the New Testament are constrained by broader traditions of entitling present in the eastern Mediterranean, but even within this framework different approaches to identifying purported authors are preserved alongside one another, with the Gospels (focusing on authorial personae) and Paul (lacking any mention of the author) on either end of the spectrum.

Most of the titles I have catalogued here are inscriptions. Schironi notes that inscriptions, what she calls ‘beginning-titles’, are rare in papyrus scrolls that contain hexametric poetry, even if they are more prevalent in prose texts.Footnote 56 She attributes the development of inscriptions to the invention of the codex, a form that also influenced the titular traditions in later Homeric scrolls.Footnote 57 Although Schironi overplays the significance of the connection between book-form and paratextual traditions, there is little doubt that the codex enabled new opportunities for paratextual development as the late ancient work of the likes of Origen and Eusebius shows. The titles in the papyri represent early experiments with paratextuality in the context of the codex, precursors to more developed paratextual systems that define the New Testament's transmission, even if the relationship between book-form, paratext and text layout are not simple to define.

The complexity of the titles in these manuscripts, produced in a period where the codex form was slowly overtaking the prevalence of the roll, which enabled new opportunities to cultivate and change paratextual traditions, also offers insight into our current moment when it comes to the medium through which scholars engage the New Testament. Like the scribes of P46 and P72, for example, we straddle two distinct but overlapping cultures, this time the print and the digital. In this space, we are still only beginning to grapple with the digital form of scholarly tools and outputs like the critical edition. At least when it comes to the New Testament, the printed critical edition is a powerful tool, honed in an ever-developing culture of print, the Editio Critica Maior being the most sophisticated and recent iteration. Modern critical editions of the New Testament are concerned primarily with purely textual issues: the reconstruction of an initial text or some other early text form, cataloguing the significant points of variation and offering access to the textual tradition without having to consult far-flung manuscripts. But images of most of the New Testament's manuscripts are available online, and scholars are nowadays privy to the open secret that editions are, by definition and necessity, highly selective, bracketing out for the most part the paratexts endemic to the manuscript tradition and (rightly) ignoring most manuscripts and their features altogether. Now more than ever it is clear that our modern critical editions do not represent the text of the New Testament but are important tools that function as guides to accessing the textual and manuscript traditions of these works. And tools can be changed or supplemented to meet new demands.

In the digital realm, the critical edition is becoming a resource that is potentially more powerful in its multimodality because images, transcriptions and other metadata can contextualise the textual choices of editors encoded in printed editions. The mass digitisation of manuscripts and the development of collaborative editorial platforms like the New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room have created a situation where we can now turn our editorial attention to the liminal but omnipresent features of the tradition to locate the past 300 years of textual scholarship within the material spaces from which these texts were initially abstracted. Features like the titles are one vector for considering the future of the critical edition, the critical value of paratexts for interpretation and reception, and the many anonymous people who read, annotated and copied sacred traditions from the second century onward. One thing is for sure: just as we continue to work with this material a century after Milligan, so too will scholars of future generations continue to read the papyri, even if it is not yet clear in what medium they will be doing so.

Competing interests

The author declares none.