Introduction

Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 (GBD 2010) study have reinforced our understanding of the significant impact that mental, neurological and substance use disorders (MNSDs) have on population health (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Vos, Lozano, Naghavi, Flaxman, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla, Aboyans, Abraham, Ackerman, Aggarwal, Ahn, Ali, Alvarado, Anderson, Anderson, Andrews, Atkinson, Baddour, Bahalim, Barker-Collo, Barrero, Bartels, Basáñez, Baxter, Bell, Benjamin, Bennett, Bernabé, Bhalla, Bhandari, Bikbov, Abdulhak, Birbeck, Black, Blencowe, Blore, Blyth, Bolliger, Bonaventure, Boufous, Bourne, Boussinesq, Braithwaite, Brayne, Bridgett, Brooker, Brooks, Brugha, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Buckle, Budke, Burch, Burney, Burstein, Calabria, Campbell, Canter, Carabin, Carapetis, Carmona, Cella, Charlson, Chen, Cheng, Chou, Chugh, Coffeng, Colan, Colquhoun, Colson, Condon, Connor, Cooper, Corriere, Cortinovis, de Vaccaro, Couser, Cowie, Criqui, Cross, Dabhadkar, Dahiya, Dahodwala, Damsere-Derry, Danaei, Davis, Leo, Degenhardt, Dellavalle, Delossantos, Denenberg, Derrett, Des Jarlais, Dharmaratne, Dherani, Diaz-Torne, Dolk, Dorsey, Driscoll, Duber, Ebel, Edmond, Elbaz, Ali, Erskine, Erwin, Espindola, Ewoigbokhan, Farzadfar, Feigin, Felson, Ferrari, Ferri, Fèvre, Finucane, Flaxman, Flood, Foreman, Forouzanfar, Fowkes, Fransen, Freeman, Gabbe, Gabriel, Gakidou, Ganatra, Garcia, Gaspari, Gillum, Gmel, Gonzalez-Medina, Gosselin, Grainger, Grant, Groeger, Guillemin, Gunnell, Gupta, Haagsma, Hagan, Halasa, Hall, Haring, Haro, Harrison, Havmoeller, Hay, Higashi, Hill, Hoen, Hoff man, Hotez, Hoy, Huang, Ibeanusi, Jacobsen, James, Jarvis, Jasrasaria, Jayaraman, Johns, Jonas, Karthikeyan, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Keren, Khoo, King, Knowlton, Kobusingye, Koranteng, Krishnamurthi, Laden, Lalloo, Laslett, Lathlean, Leasher, Lee, Leigh, Levinson, Lim, Limb, Lin, Lipnick, Lipshultz, Liu, Loane, Ohno, Lyons, Mabweijano, MacIntyre, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Manivannan, Marcenes, March, Margolis, Marks, Marks, Matsumori, Matzopoulos, Mayosi, McAnulty, McDermott, McGill, McGrath, Medina-Mora, Meltzer, Mensah, Merriman, Meyer, Miglioli, Miller, Miller, Mitchell, Mock, Mocumbi, Moffitt, Mokdad, Monasta, Montico, Moradi-Lakeh, Moran, Morawska, Mori, Murdoch, Mwaniki, Naidoo, Nair, Naldi, Venkat Narayan, Nelson, Nelson, Nevitt, Newton, Nolte, Norman, Norman, O'Donnell, O'Hanlon, Olives, Omer, Ortblad, Osborne, Ozgediz, Page, Pahari, Pandian, Rivero, Patten, Pearce, Perez Padilla, Perez-Ruiz, Perico, Pesudovs, Phillips, Phillips, Pierce, Pion, Polanczyk, Polinder, Pope III, Popova, Porrini, Pourmalek, Prince, Pullan, Ramaiah, Ranganathan, Razavi, Regan, Rehm, Rein, Remuzzi and Richards2012; Whiteford et al. Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine, Charlson, Norman, Flaxman, Johns, Burstein, Murray and Vos2013). One of the key findings of GBD 2010 was the global health transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases and this is particularly rapidly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Vos, Lozano, Naghavi, Flaxman, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla, Aboyans, Abraham, Ackerman, Aggarwal, Ahn, Ali, Alvarado, Anderson, Anderson, Andrews, Atkinson, Baddour, Bahalim, Barker-Collo, Barrero, Bartels, Basáñez, Baxter, Bell, Benjamin, Bennett, Bernabé, Bhalla, Bhandari, Bikbov, Abdulhak, Birbeck, Black, Blencowe, Blore, Blyth, Bolliger, Bonaventure, Boufous, Bourne, Boussinesq, Braithwaite, Brayne, Bridgett, Brooker, Brooks, Brugha, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Buckle, Budke, Burch, Burney, Burstein, Calabria, Campbell, Canter, Carabin, Carapetis, Carmona, Cella, Charlson, Chen, Cheng, Chou, Chugh, Coffeng, Colan, Colquhoun, Colson, Condon, Connor, Cooper, Corriere, Cortinovis, de Vaccaro, Couser, Cowie, Criqui, Cross, Dabhadkar, Dahiya, Dahodwala, Damsere-Derry, Danaei, Davis, Leo, Degenhardt, Dellavalle, Delossantos, Denenberg, Derrett, Des Jarlais, Dharmaratne, Dherani, Diaz-Torne, Dolk, Dorsey, Driscoll, Duber, Ebel, Edmond, Elbaz, Ali, Erskine, Erwin, Espindola, Ewoigbokhan, Farzadfar, Feigin, Felson, Ferrari, Ferri, Fèvre, Finucane, Flaxman, Flood, Foreman, Forouzanfar, Fowkes, Fransen, Freeman, Gabbe, Gabriel, Gakidou, Ganatra, Garcia, Gaspari, Gillum, Gmel, Gonzalez-Medina, Gosselin, Grainger, Grant, Groeger, Guillemin, Gunnell, Gupta, Haagsma, Hagan, Halasa, Hall, Haring, Haro, Harrison, Havmoeller, Hay, Higashi, Hill, Hoen, Hoff man, Hotez, Hoy, Huang, Ibeanusi, Jacobsen, James, Jarvis, Jasrasaria, Jayaraman, Johns, Jonas, Karthikeyan, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Keren, Khoo, King, Knowlton, Kobusingye, Koranteng, Krishnamurthi, Laden, Lalloo, Laslett, Lathlean, Leasher, Lee, Leigh, Levinson, Lim, Limb, Lin, Lipnick, Lipshultz, Liu, Loane, Ohno, Lyons, Mabweijano, MacIntyre, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Manivannan, Marcenes, March, Margolis, Marks, Marks, Matsumori, Matzopoulos, Mayosi, McAnulty, McDermott, McGill, McGrath, Medina-Mora, Meltzer, Mensah, Merriman, Meyer, Miglioli, Miller, Miller, Mitchell, Mock, Mocumbi, Moffitt, Mokdad, Monasta, Montico, Moradi-Lakeh, Moran, Morawska, Mori, Murdoch, Mwaniki, Naidoo, Nair, Naldi, Venkat Narayan, Nelson, Nelson, Nevitt, Newton, Nolte, Norman, Norman, O'Donnell, O'Hanlon, Olives, Omer, Ortblad, Osborne, Ozgediz, Page, Pahari, Pandian, Rivero, Patten, Pearce, Perez Padilla, Perez-Ruiz, Perico, Pesudovs, Phillips, Phillips, Pierce, Pion, Polanczyk, Polinder, Pope III, Popova, Porrini, Pourmalek, Prince, Pullan, Ramaiah, Ranganathan, Razavi, Regan, Rehm, Rein, Remuzzi and Richards2012). The proportion of burden attributable to non-communicable disease in LMICs has risen by more than one-third, from 36% in 1990 to 49% in 2010. In contrast, the share of non-communicable disease burden in high-income countries (HICs) has raised only 3–4% over the same time period (from 80 to 83%) (Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2013). These findings hold particular public health importance for MNSDs in LMICs for the coming decades.

GBD 2010 estimates the majority of disease burden due to MNSDs is from non-fatal health loss; only 15% of the total burden is from mortality, in terms of years of life lost (YLLs) (Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2013). This may erroneously lead to the interpretation that premature death in people with mental and neurological disorders is inconsequential, whereas evidence shows that people with MNSDs experience a significant reduction in life expectancy (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Hayes, Perera, Broadbent, Fernandes, Lee, Hotopf and Stewart2011; Wahlbeck et al. Reference Wahlbeck, Westman, Nordentoft, Gissler and Laursen2011; Crump et al. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist2013; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013). In Australia and the UK males with a mental disorder die, on average, 15 years earlier than the general population and females die on average 12 years earlier (Crump et al. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist2013; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013). It is estimated that about 80% of premature deaths in people with MNSDs are due to physical illnesses, particularly cardiovascular disease, including stroke and cancer (Crump et al. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist2013; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013). Dementia is an independent risk factor for premature death with increased risk found in those patients with physical impairment and inactivity, and medical comorbidities (Park et al. Reference Park, Lee, Suh, Kim and Cho2014). Excess mortality in people with epilepsy is reported to be two- to threefold higher compared with the general population; with an increased risk of up to sixfold higher in LMICs (Diop et al. Reference Diop, Hesdorffer, Logroscino and Hauser2005). A significant proportion of these deaths are preventable, resulting from falls, drowning, burns and status epilepticus (Diop et al. Reference Diop, Hesdorffer, Logroscino and Hauser2005; Jette & Trevathan, Reference Jette and Trevathan2014). A recent review has shown the highest standardised mortality ratio (SMR) among mental and substance use disorders was 14.7 for opioid use disorders (Chesney et al. Reference Chesney, Goodwin and Fazel2014). In HICs the life expectancy gap is widening with the general population now enjoying a longer life while the lifespan for those with a mental disorder has remained static (Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013).

Mortality associated with a disease can be quantified using two different, yet complementary, methods which are employed as part of GBD analyses. First, cause-specific mortality draws upon vital registration systems and verbal autopsy studies which identify deaths attributed to a single underlying cause using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) death-coding system. Second, GBD creates natural history models for each disease, including its distribution across age and sex. This involves estimation of a range of epidemiological parameters, including excess mortality – that is, the all-cause mortality rate in a population with the disorder compared with the all-cause mortality rates in a population without the disorder. By definition, estimates of excess deaths include cause-specific deaths.

Although often arbitrary, the ICD conventions are a necessary attempt to deal with the multi-causal nature of mortality and avoid ‘double-counting’ of deaths. However, despite the systems clear strengths, cause-specific mortality estimated via the ICD obscures the contribution of other underlying causes of death; for example, suicide as a direct result of major depressive disorder coded as injury, and will likely underestimate the true number of deaths attributable to a particular disease. On the other hand, estimation of excess mortality using natural history models will often comprise deaths from both causal and non-causal origins and will likely overestimate the true number of deaths attributable to a particular disorder. The challenge is to parse out causal contributions to mortality (beyond those already identified as cause-specific) from the effects of confounders.

Quantification of the contributions of multiple causal factors to excess mortality associated with a particular disease is challenging and requires approaches such as the comparative risk assessment (CRA), which is now an integral part of the GBD studies. The fundamental approach for the GBD CRA is to calculate the proportion of deaths or disease burden caused by specific risk factors – e.g., lung cancer caused by tobacco smoking – while holding all other independent factors unchanged. A key concept when attempting to quantify causal relationships is that of ‘counterfactual burden’ which compares the burden associated with an outcome with the amount that would be expected in a hypothetical situation of ‘ideal’ risk factor exposure (e.g., zero prevalence). This approach provides a consistent method for estimating the changes in population health as a function of decreasing or increasing the level of exposure to risk factors (Lim et al. Reference Lim, Vos, Flaxman, Danaei, Shibuya, Adair-Rohani, Amann, Anderson, Andrews, Aryee, Atkinson, Bacchus, Bahalim, Balakrishnan, Balmes, Barker-Collo, Baxter, Bell, Blore, Blyth, Bonner, Borges, Bourne, Boussinesq, Brauer, Brooks, Bruce, Brunekreef, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Bull, Burnett, Byers, Calabria, Carapetis, Carnahan, Chafe, Charlson, Chen, Chen, Cheng, Child, Cohen, Colson, Cowie, Darby, Darling, Davis, Degenhardt, Dentener, Des Jarlais, Devries, Dherani, Ding, Dorsey, Driscoll, Edmond, Ali, Engell, Erwin, Fahimi, Falder, Farzadfar, Ferrari, Finucane, Flaxman, Fowkes, Freedman, Freeman, Gakidou, Ghosh, Giovannucci, Gmel, Graham, Grainger, Grant, Gunnell, Gutierrez, Hall, Hoek, Hogan, Hosgood III, Hoy, Hu, Hubbell, Hutchings, Ibeanusi, Jacklyn, Jasrasaria, Jonas, Kan, Kanis, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Khang, Khatibzadeh, Khoo, Kok, Laden, Lalloo, Lan, Lathlean, Leasher, Leigh, Li, Lin, Lipshultz, London, Lozano, Lu, Mak, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Marcenes, March, Marks, Martin, McGale, McGrath, Mehta, Mensah, Merriman, Micha, Michaud, Mishra, Hanafiah, Mokdad, Morawska, Mozaffarian, Murphy, Naghavi, Neal, Nelson, Nolla, Norman, Olives, Omer, Orchard, Osborne, Ostro, Page, Pandey, Parry, Passmore, Patra, Pearce, Pelizzari, Petzold, Phillips, Pope, Pope III, Powles, Rao, Razavi, Rehfuess, Rehm, Ritz, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson, Rodriguez-Portales, Romieu, Room, Rosenfeld, Roy, Rushton, Salomon, Sampson, Sanchez-Riera, Sanman, Sapkota, Seedat, Shi, Shield, Shivakoti, Singh, Sleet, Smith, Smith, Stapelberg, Steenland, Stöckl, Stovner, Straif, Straney, Thurston, Tran, Van Dingenen, van Donkelaar, Veerman, Vijayakumar, Weintraub, Weissman, White, Whiteford, Wiersma, Wilkinson, Williams, Williams, Wilson, Woolf, Yip, Zielinski, Lopez, Murray and Ezzati2012). Importantly, the flexibility within counterfactual analysis allows the sum of death counts attributed to different risk factors for a particular cause to sum to more than 100% which is not permissible by ICD registry data.

In this paper, we explore the cause-specific and excess mortality of individual MNSDs estimated by GBD 2010. We also present the additional attributable burden that can be ascribed to disorders using GBD results for CRA's assessing MNSDs as risk factors for other health outcomes. Disorders included in the analyses are grouped by: mental disorders (schizophrenia, major depression (MDD), anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, childhood behavioural disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder (CD)), autistic disorder and intellectual disability); substance use disorders (alcohol, opioid, cocaine and amphetamine use disorders); and neurological disorders (dementia, epilepsy and migraine).

Methods

YLLs and cause of death

The GBD 2010 methodology uses a time-based metric, YLLs, to quantify the fatal burden by underlying cause (Lozano et al. Reference Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, Lim, Shibuya, Aboyans, Abraham, Adair, Aggarwal and Ahn2012). YLLs are computed by multiplying the number of deaths attributable to a particular disease at each age by a standard life expectancy at that age. The standard life expectancy represents the normative goal for survival and for 2010 was computed based on the lowest recorded death rates in any age group in countries with a population greater than 5 million (Salomon et al. Reference Salomon, Wang, Freeman, Vos, Flaxman, Lopez and Murray2012).

Cause-specific death estimates in GBD 2010 were produced from available cause of death data for 187 countries from 1980 to 2010. Data sources included vital registration, verbal autopsy, mortality surveillance, censuses, surveys, hospitals, police records and mortuaries (Lozano et al. Reference Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, Lim, Shibuya, Aboyans, Abraham, Adair, Aggarwal and Ahn2012). Cause of death ensemble modelling (CODEm) was used for all MNSDs. In summary, CODEm uses four families of statistical models testing a large set of different models using different permutations of covariates. Model ensembles were developed from these component models and model performance was assessed with rigorous out-of-sample testing of prediction error and the validity of 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs). Details relating to CODEm and the method for how these models were used in calculating YLLs are described in detail elsewhere (Lozano et al. Reference Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, Lim, Shibuya, Aboyans, Abraham, Adair, Aggarwal and Ahn2012).

YLLs for GBD 2010 were computed from cause-specific mortality estimates for seven of the 15 MNSDs: schizophrenia; opioid, amphetamine, cocaine and alcohol use disorders; dementia and epilepsy (Lozano et al. Reference Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, Lim, Shibuya, Aboyans, Abraham, Adair, Aggarwal and Ahn2012). As the ICD does not permit the other mental and neurological disorders to be recorded as the ‘primary’ cause of death, YLLs were unable to be calculated for the remaining eight disorder groups (World Health Organization, 1993; Lim et al. Reference Lim, Vos, Flaxman, Danaei, Shibuya, Adair-Rohani, Amann, Anderson, Andrews, Aryee, Atkinson, Bacchus, Bahalim, Balakrishnan, Balmes, Barker-Collo, Baxter, Bell, Blore, Blyth, Bonner, Borges, Bourne, Boussinesq, Brauer, Brooks, Bruce, Brunekreef, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Bull, Burnett, Byers, Calabria, Carapetis, Carnahan, Chafe, Charlson, Chen, Chen, Cheng, Child, Cohen, Colson, Cowie, Darby, Darling, Davis, Degenhardt, Dentener, Des Jarlais, Devries, Dherani, Ding, Dorsey, Driscoll, Edmond, Ali, Engell, Erwin, Fahimi, Falder, Farzadfar, Ferrari, Finucane, Flaxman, Fowkes, Freedman, Freeman, Gakidou, Ghosh, Giovannucci, Gmel, Graham, Grainger, Grant, Gunnell, Gutierrez, Hall, Hoek, Hogan, Hosgood III, Hoy, Hu, Hubbell, Hutchings, Ibeanusi, Jacklyn, Jasrasaria, Jonas, Kan, Kanis, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Khang, Khatibzadeh, Khoo, Kok, Laden, Lalloo, Lan, Lathlean, Leasher, Leigh, Li, Lin, Lipshultz, London, Lozano, Lu, Mak, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Marcenes, March, Marks, Martin, McGale, McGrath, Mehta, Mensah, Merriman, Micha, Michaud, Mishra, Hanafiah, Mokdad, Morawska, Mozaffarian, Murphy, Naghavi, Neal, Nelson, Nolla, Norman, Olives, Omer, Orchard, Osborne, Ostro, Page, Pandey, Parry, Passmore, Patra, Pearce, Pelizzari, Petzold, Phillips, Pope, Pope III, Powles, Rao, Razavi, Rehfuess, Rehm, Ritz, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson, Rodriguez-Portales, Romieu, Room, Rosenfeld, Roy, Rushton, Salomon, Sampson, Sanchez-Riera, Sanman, Sapkota, Seedat, Shi, Shield, Shivakoti, Singh, Sleet, Smith, Smith, Stapelberg, Steenland, Stöckl, Stovner, Straif, Straney, Thurston, Tran, Van Dingenen, van Donkelaar, Veerman, Vijayakumar, Weintraub, Weissman, White, Whiteford, Wiersma, Wilkinson, Williams, Williams, Wilson, Woolf, Yip, Zielinski, Lopez, Murray and Ezzati2012).

Excess mortality from a natural history model

Drawing on a series of systematic reviews, we collated comprehensive sets of epidemiologic data for each disorder. Data were pooled, adjusting for between-study variance, and then an internally consistent epidemiologic model derived using the relationship described in the generic disease model (see the appendix) (Vos et al. Reference Vos, Flaxman, Naghavi, Lozano, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla, Aboyans, Abraham, Ackerman, Aggarwal, Ahn, Ali, Alvarado, Anderson, Anderson, Andrews, Atkinson, Baddour, Bahalim, Barker-Collo, Barrero, Bartels, Basáñez, Baxter, Bell, Benjamin, Bennett, Bernabé, Bhalla, Bhandari, Bikbov, Bin Abdulhak, Birbeck, Black, Blencowe, Blore, Blyth, Bolliger, Bonaventure, Boufous, Bourne, Boussinesq, Braithwaite, Brayne, Bridgett, Brooker, Brooks, Brugha, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Buckle, Budke, Burch, Burney, Burstein, Calabria, Campbell, Canter, Carabin, Carapetis, Carmona, Cella, Charlson, Chen, Cheng, Chou, Chugh, Coffeng, Colan, Colquhoun, Colson, Condon, Connor, Cooper, Corriere, Cortinovis, de Vaccaro, Couser, Cowie, Criqui, Cross, Dabhadkar, Dahiya, Dahodwala, Damsere-Derry, Danaei, Davis, De Leo, Degenhardt, Dellavalle, Delossantos, Denenberg, Derrett, Des Jarlais, Dharmaratne, Dherani, Diaz-Torne, Dolk, Dorsey, Driscoll, Duber, Ebel, Edmond, Elbaz, Ali, Erskine, Erwin, Espindola, Ewoigbokhan, Farzadfar, Feigin, Felson, Ferrari, Ferri, Fèvre, Finucane, Flaxman, Flood, Foreman, Forouzanfar, Fowkes, Franklin, Fransen, Freeman, Gabbe, Gabriel, Gakidou, Ganatra, Garcia, Gaspari, Gillum, Gmel, Gosselin, Grainger, Groeger, Guillemin, Gunnell, Gupta, Haagsma, Hagan, Halasa, Hall, Haring, Haro, Harrison, Havmoeller, Hay, Higashi, Hill, Hoen, Hoff man, Hotez, Hoy, Huang, Ibeanusi, Jacobsen, James, Jarvis, Jasrasaria, Jayaraman, Johns, Jonas, Karthikeyan, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Keren, Khoo, King, Knowlton, Kobusingye, Koranteng, Krishnamurthi, Lalloo, Laslett, Lathlean, Leasher, Lee, Leigh, Lim, Limb, Lin, Lipnick, Lipshultz, Liu, Loane, Ohno, Lyons, Ma, Mabweijano, MacIntyre, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Manivannan, Marcenes, March, Margolis, Marks, Marks, Matsumori, Matzopoulos, Mayosi, McAnulty, McDermott, McGill, McGrath, Medina-Mora, Meltzer, Mensah, Merriman, Meyer, Miglioli, Miller, Miller, Mitchell, Mocumbi, Moffitt, Mokdad, Monasta, Montico, Moradi-Lakeh, Moran, Morawska, Mori, Murdoch, Mwaniki, Naidoo, Nair, Naldi, Venkat Narayan, Nelson, Nelson, Nevitt, Newton, Nolte, Norman, Norman, O'Donnell, O'Hanlon, Olives, Omer, Ortblad, Osborne, Ozgediz, Page, Pahari, Pandian, Rivero, Patten, Pearce, Perez Padilla, Perez-Ruiz, Perico, Pesudovs, Phillips, Phillips, Pierce, Pion, Polanczyk, Polinder, Pope III, Popova, Porrini, Pourmalek, Prince, Pullan, Ramaiah, Ranganathan, Razavi, Regan, Rehm, Rein, Remuzzi, Richardson, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson and De Leòn2012). To do this we used DisMod-MR, a Bayesian meta-regression tool which estimates a natural history of disease model producing age-, sex- and region-specific estimates for prevalence, incidence, remission and excess mortality (Vos et al. Reference Vos, Flaxman, Naghavi, Lozano, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla, Aboyans, Abraham, Ackerman, Aggarwal, Ahn, Ali, Alvarado, Anderson, Anderson, Andrews, Atkinson, Baddour, Bahalim, Barker-Collo, Barrero, Bartels, Basáñez, Baxter, Bell, Benjamin, Bennett, Bernabé, Bhalla, Bhandari, Bikbov, Bin Abdulhak, Birbeck, Black, Blencowe, Blore, Blyth, Bolliger, Bonaventure, Boufous, Bourne, Boussinesq, Braithwaite, Brayne, Bridgett, Brooker, Brooks, Brugha, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Buckle, Budke, Burch, Burney, Burstein, Calabria, Campbell, Canter, Carabin, Carapetis, Carmona, Cella, Charlson, Chen, Cheng, Chou, Chugh, Coffeng, Colan, Colquhoun, Colson, Condon, Connor, Cooper, Corriere, Cortinovis, de Vaccaro, Couser, Cowie, Criqui, Cross, Dabhadkar, Dahiya, Dahodwala, Damsere-Derry, Danaei, Davis, De Leo, Degenhardt, Dellavalle, Delossantos, Denenberg, Derrett, Des Jarlais, Dharmaratne, Dherani, Diaz-Torne, Dolk, Dorsey, Driscoll, Duber, Ebel, Edmond, Elbaz, Ali, Erskine, Erwin, Espindola, Ewoigbokhan, Farzadfar, Feigin, Felson, Ferrari, Ferri, Fèvre, Finucane, Flaxman, Flood, Foreman, Forouzanfar, Fowkes, Franklin, Fransen, Freeman, Gabbe, Gabriel, Gakidou, Ganatra, Garcia, Gaspari, Gillum, Gmel, Gosselin, Grainger, Groeger, Guillemin, Gunnell, Gupta, Haagsma, Hagan, Halasa, Hall, Haring, Haro, Harrison, Havmoeller, Hay, Higashi, Hill, Hoen, Hoff man, Hotez, Hoy, Huang, Ibeanusi, Jacobsen, James, Jarvis, Jasrasaria, Jayaraman, Johns, Jonas, Karthikeyan, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Keren, Khoo, King, Knowlton, Kobusingye, Koranteng, Krishnamurthi, Lalloo, Laslett, Lathlean, Leasher, Lee, Leigh, Lim, Limb, Lin, Lipnick, Lipshultz, Liu, Loane, Ohno, Lyons, Ma, Mabweijano, MacIntyre, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Manivannan, Marcenes, March, Margolis, Marks, Marks, Matsumori, Matzopoulos, Mayosi, McAnulty, McDermott, McGill, McGrath, Medina-Mora, Meltzer, Mensah, Merriman, Meyer, Miglioli, Miller, Miller, Mitchell, Mocumbi, Moffitt, Mokdad, Monasta, Montico, Moradi-Lakeh, Moran, Morawska, Mori, Murdoch, Mwaniki, Naidoo, Nair, Naldi, Venkat Narayan, Nelson, Nelson, Nevitt, Newton, Nolte, Norman, Norman, O'Donnell, O'Hanlon, Olives, Omer, Ortblad, Osborne, Ozgediz, Page, Pahari, Pandian, Rivero, Patten, Pearce, Perez Padilla, Perez-Ruiz, Perico, Pesudovs, Phillips, Phillips, Pierce, Pion, Polanczyk, Polinder, Pope III, Popova, Porrini, Pourmalek, Prince, Pullan, Ramaiah, Ranganathan, Razavi, Regan, Rehm, Rein, Remuzzi, Richardson, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson and De Leòn2012). Where data were scarce, DisMod-MR was able to impute information with associated uncertainty ranges based on epidemiologically and geographically similar populations. Excess mortality estimates based on this natural history model are reported for MNSDs in terms of global deaths for 2010. Further details of the GBD 2010 methods for developing a natural history model of disease using DisMod-MR have been described in detail elsewhere (Vos et al. Reference Vos, Flaxman, Naghavi, Lozano, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla, Aboyans, Abraham, Ackerman, Aggarwal, Ahn, Ali, Alvarado, Anderson, Anderson, Andrews, Atkinson, Baddour, Bahalim, Barker-Collo, Barrero, Bartels, Basáñez, Baxter, Bell, Benjamin, Bennett, Bernabé, Bhalla, Bhandari, Bikbov, Bin Abdulhak, Birbeck, Black, Blencowe, Blore, Blyth, Bolliger, Bonaventure, Boufous, Bourne, Boussinesq, Braithwaite, Brayne, Bridgett, Brooker, Brooks, Brugha, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Buckle, Budke, Burch, Burney, Burstein, Calabria, Campbell, Canter, Carabin, Carapetis, Carmona, Cella, Charlson, Chen, Cheng, Chou, Chugh, Coffeng, Colan, Colquhoun, Colson, Condon, Connor, Cooper, Corriere, Cortinovis, de Vaccaro, Couser, Cowie, Criqui, Cross, Dabhadkar, Dahiya, Dahodwala, Damsere-Derry, Danaei, Davis, De Leo, Degenhardt, Dellavalle, Delossantos, Denenberg, Derrett, Des Jarlais, Dharmaratne, Dherani, Diaz-Torne, Dolk, Dorsey, Driscoll, Duber, Ebel, Edmond, Elbaz, Ali, Erskine, Erwin, Espindola, Ewoigbokhan, Farzadfar, Feigin, Felson, Ferrari, Ferri, Fèvre, Finucane, Flaxman, Flood, Foreman, Forouzanfar, Fowkes, Franklin, Fransen, Freeman, Gabbe, Gabriel, Gakidou, Ganatra, Garcia, Gaspari, Gillum, Gmel, Gosselin, Grainger, Groeger, Guillemin, Gunnell, Gupta, Haagsma, Hagan, Halasa, Hall, Haring, Haro, Harrison, Havmoeller, Hay, Higashi, Hill, Hoen, Hoff man, Hotez, Hoy, Huang, Ibeanusi, Jacobsen, James, Jarvis, Jasrasaria, Jayaraman, Johns, Jonas, Karthikeyan, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Keren, Khoo, King, Knowlton, Kobusingye, Koranteng, Krishnamurthi, Lalloo, Laslett, Lathlean, Leasher, Lee, Leigh, Lim, Limb, Lin, Lipnick, Lipshultz, Liu, Loane, Ohno, Lyons, Ma, Mabweijano, MacIntyre, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Manivannan, Marcenes, March, Margolis, Marks, Marks, Matsumori, Matzopoulos, Mayosi, McAnulty, McDermott, McGill, McGrath, Medina-Mora, Meltzer, Mensah, Merriman, Meyer, Miglioli, Miller, Miller, Mitchell, Mocumbi, Moffitt, Mokdad, Monasta, Montico, Moradi-Lakeh, Moran, Morawska, Mori, Murdoch, Mwaniki, Naidoo, Nair, Naldi, Venkat Narayan, Nelson, Nelson, Nevitt, Newton, Nolte, Norman, Norman, O'Donnell, O'Hanlon, Olives, Omer, Ortblad, Osborne, Ozgediz, Page, Pahari, Pandian, Rivero, Patten, Pearce, Perez Padilla, Perez-Ruiz, Perico, Pesudovs, Phillips, Phillips, Pierce, Pion, Polanczyk, Polinder, Pope III, Popova, Porrini, Pourmalek, Prince, Pullan, Ramaiah, Ranganathan, Razavi, Regan, Rehm, Rein, Remuzzi, Richardson, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson and De Leòn2012).

Counter-factual burden and CRA

Prince et al. (Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko, Phillips and Rahman2007) have summarised the evidence where a causal relationship between mental and substance use disorders and other health outcomes have been proposed. In GBD 2010, a series of reviews were conducted to assess the strength of evidence for MNSDs as independent risk factors for other health outcomes (Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Hall, Lynskey, Mcgrath, Mclaren, Calabria, Whiteford and Vos2009a ; Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe, Parry, Patra, Popova, Poznyak, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov and Taylor2010a ; Charlson et al. Reference Charlson, Stapelberg, Baxter and Whiteford2011; Degenhardt & Hall, Reference Degenhardt and Hall2012). Risk factor studies were identified through systematic searches of published and unpublished data with information on effect sizes and study characteristics extracted and collated (Charlson et al. Reference Charlson, Moran, Freedman, Norman, Stapelberg, Baxter, Vos and Whiteford2013; Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Whiteford, Ferrari, Baxter, Charlson, Hall, Freedman, Burstein, Johns, Engell, Flaxman, Murray and Vos2013; Ferrari et al. Reference Ferrari, Norman, Freedman, Baxter, Pirkis, Harris, Page, Carnahan, Degenhardt, Vos and Whiteford2014). A meta-synthesis was used to calculate a relative risk (RR) for MNSDs (the exposure) as a risk factor for other health outcomes. The RR was then applied to prevalence distributions of the specific exposures by sex and age-group for each geographic region to derive population attributable fractions (PAFs). More detail on the calculation of PAFs in GBD 2010 is provided by Lim et al. (Reference Lim, Vos, Flaxman, Danaei, Shibuya, Adair-Rohani, Amann, Anderson, Andrews, Aryee, Atkinson, Bacchus, Bahalim, Balakrishnan, Balmes, Barker-Collo, Baxter, Bell, Blore, Blyth, Bonner, Borges, Bourne, Boussinesq, Brauer, Brooks, Bruce, Brunekreef, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Bull, Burnett, Byers, Calabria, Carapetis, Carnahan, Chafe, Charlson, Chen, Chen, Cheng, Child, Cohen, Colson, Cowie, Darby, Darling, Davis, Degenhardt, Dentener, Des Jarlais, Devries, Dherani, Ding, Dorsey, Driscoll, Edmond, Ali, Engell, Erwin, Fahimi, Falder, Farzadfar, Ferrari, Finucane, Flaxman, Fowkes, Freedman, Freeman, Gakidou, Ghosh, Giovannucci, Gmel, Graham, Grainger, Grant, Gunnell, Gutierrez, Hall, Hoek, Hogan, Hosgood III, Hoy, Hu, Hubbell, Hutchings, Ibeanusi, Jacklyn, Jasrasaria, Jonas, Kan, Kanis, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Khang, Khatibzadeh, Khoo, Kok, Laden, Lalloo, Lan, Lathlean, Leasher, Leigh, Li, Lin, Lipshultz, London, Lozano, Lu, Mak, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Marcenes, March, Marks, Martin, McGale, McGrath, Mehta, Mensah, Merriman, Micha, Michaud, Mishra, Hanafiah, Mokdad, Morawska, Mozaffarian, Murphy, Naghavi, Neal, Nelson, Nolla, Norman, Olives, Omer, Orchard, Osborne, Ostro, Page, Pandey, Parry, Passmore, Patra, Pearce, Pelizzari, Petzold, Phillips, Pope, Pope III, Powles, Rao, Razavi, Rehfuess, Rehm, Ritz, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson, Rodriguez-Portales, Romieu, Room, Rosenfeld, Roy, Rushton, Salomon, Sampson, Sanchez-Riera, Sanman, Sapkota, Seedat, Shi, Shield, Shivakoti, Singh, Sleet, Smith, Smith, Stapelberg, Steenland, Stöckl, Stovner, Straif, Straney, Thurston, Tran, Van Dingenen, van Donkelaar, Veerman, Vijayakumar, Weintraub, Weissman, White, Whiteford, Wiersma, Wilkinson, Williams, Williams, Wilson, Woolf, Yip, Zielinski, Lopez, Murray and Ezzati2012). In some cases, for example suicide, ceiling values were calculated and applied for joint PAFs to ensure the sum of proportional contribution for all risk factors did not exceed 100% (Ferrari et al. Reference Ferrari, Norman, Freedman, Baxter, Pirkis, Harris, Page, Carnahan, Degenhardt, Vos and Whiteford2014). The additional burden (YLLs and YLDs) attributable to MNSDs is the product of the PAFs and the burden for the health outcome as estimated in GBD 2010.

Here we compare the number of cause-specific deaths reported (YLLs) for MNSDs, calculated as part of the GBD 2010 study with the number of all-cause deaths derived from natural history models. We explore differences in these estimates across the age-span for each disorder. Additional YLLs attributed to disorders as underlying causes and quantified in the CRA are reported.

Results

YLLs and causal mortality

Globally, the seven disorders (dementia, epilepsy, schizophrenia, alcohol use disorders, opioid use disorders, cocaine use disorders and amphetamine use disorders) for which YLLs were estimated were directly responsible for 1.3 million deaths in 2010, equating to about 12 million YLLs (see Fig. 2 in the appendix). Epilepsy and then dementia contributed the greatest proportion of YLLs within this group.

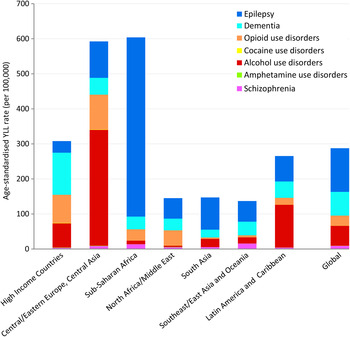

Age-standardised YLL rates vary considerably across the seven geographical super-regions primarily due to differences in patterns of alcohol and drug use, and mental and neurological disorder prevalence. There are several regions with substantial deviations from global YLL average rates (Fig. 1). (Details of which countries are in each sup-region can be found on the IHME website (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2014).)

Fig. 1. Age-standardised YLL rates (per 100 000 population) for MNSDs by GBD super-region and disorder, 2010.

In 2010, YLL rates were highest in the sub-Saharan Africa region (604 YLLs per 100 000 population) and the region comprising Central/Eastern Europe plus Central Asia (593 YLLs per 100 000); the causes for which vary considerably (Fig. 1). In sub-Saharan Africa the YLL burden was driven by epilepsy which was fourfold higher than the global average and approximately 85% of all YLLs attributed to MNSDs in sub-Saharan Africa. Although the substance use disorders YLL rates appear unremarkable for this region, their YLL burden has increased 3.0% from 1990 to 2010, almost double the average global increase and the highest of all regions (Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Whiteford, Ferrari, Baxter, Charlson, Hall, Freedman, Burstein, Johns, Engell, Flaxman, Murray and Vos2013). In contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, the high fatal burden in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia was largely caused by deaths attributed to alcohol use. High mortality due to illicit substance use disorders also contributed to the YLL rate in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia with all substance use disorders together explaining 73% of YLLs in the region. Countries within East Asia and the Pacific exhibit very low YLL rates across all MNSDs with little change observed between 1990 and 2010.

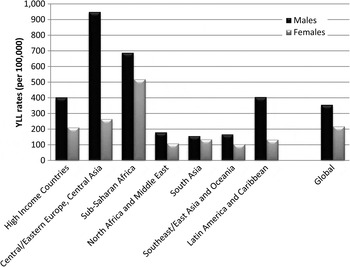

Globally, neurological disorders accounted for 58% of the all MNSD YLLs in males and 81% of YLLs in females. Substance use disorders explained 39% of YLLs in males and 16% of those in females. The contribution of schizophrenia to total MNS disorder YLLs was similar for both genders (3% each). Differences in YLL patterns between the genders were influenced in part by the differing contribution to YLLs by substance use disorders compared with neurological disorders across regions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Age-standardised YLL rates (per 100 000) for MNSDs by GBD super-region and sex, 2010.

Excess mortality from a natural history model

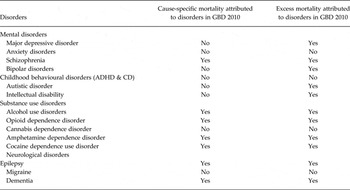

The only mental disorder for which cause-specific deaths and YLLs were estimated in GBD was schizophrenia; however, several mental disorders, such as major depression and bipolar disorder, exhibit significant and documented excess-mortality (Roshanaei-Moghaddam & Katon, Reference Roshanaei-Moghaddam and Katon2009; Baxter et al. Reference Baxter, Page and Whiteford2011b ) (Table 1). There were four disorders for which sufficient evidence of excess all-cause mortality could not be found in the literature (anxiety, childhood behavioural disorders, cannabis dependence and migraine) and therefore excess mortality was not included in the natural history of disease for these disorders.

Table 1. Presence of cause-specific mortality and excess mortality attributed to DCP3 MNSDs in GBD 2010

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD, conduct disorder.

Mental disorders

Figure 3 shows the estimated number of cause-specific and excess deaths for each of the five mental disorders with estimated excess mortality by age and with uncertainty bounds. While cause-specific deaths were attributed to only one mental disorder (schizophrenia), excess mortality was present in natural history models for five: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, autistic disorder and intellectual disability.

Fig. 3. Numbers of cause-specific and excess deaths attributed to mental disorders in 2010, by age with upper and lower 95% CI. *Note: ADHD, CD and anxiety not shown as there were no cause-specific or excess mortality estimated (Table 1).

Although schizophrenia is one of the few mental disorders with cause-specific deaths permissible by ICD, the numbers of cause-specific deaths globally (approximately 20 000) are noticeably lower compared with all-cause deaths (approximately 700 000) ascribed by the disorder's natural history. Around 1.3 million excess deaths are estimated in the natural history model of bipolar disorder but there are no cause-specific deaths attributed to the disorder. The natural history of the disease suggests, however, that bipolar disorder is associated with a higher number of excess deaths globally than schizophrenia. No deaths were coded to depressive disorders in GBD 2010. Natural history models of MDD suggest there were more than 2.2 million excess deaths in persons with MDD, with a particularly high rate of death in older persons that is not observed in schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Intellectual disability was modelled as an ‘envelope disorder’ for GBD 2010, meaning that the intellectual disability ascribed to all underlying causes including meningitis, Down's syndrome, and chromosomal defects, were captured under a single disorder category. After modelling, the contributions of each specific underlying cause were separated out and a ‘rest’ category of idiopathic intellectual disability was created. There were no deaths causally attributed to intellectual disability; however, excess deaths in people with idiopathic intellectual disability were estimated to be substantial at over 900 000 deaths globally in 2010.

At this time there is insufficient information available to determine whether premature mortality is significantly raised across the spectrum of anxiety disorders (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter, Vos, Scott, Norman, Flaxman, Blore and Whiteford2014) and in childhood behavioural disorders (Erskine et al. Reference Erskine, Ferrari, Nelson, Polanczyk, Flaxman, Vos, Whiteford and Scott2013). In GBD 2010 there were no YLLs or excess mortality associated with the natural history of disease applied to anxiety disorders or childhood behavioural disorders.

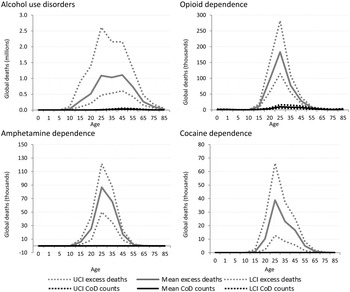

Substance use disorders

GBD estimates indicate more than 110 000 deaths were causally attributed to alcohol use disorders worldwide in 2010, but indicative of the true impact of alcohol dependence as an underlying cause of death in many is that over 5 million excess deaths were estimated in the same year. Over 700 000 excess deaths occurred in dependent illicit drug users in 2010 compared with only 44 000 deaths which were coded as the cause of death. The majority of these deaths can be ascribed to opioid dependence (43 000) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Numbers of cause-specific and excess deaths attributed to substance use disorders in 2010, by age and with upper and lower 95% CI. *Note: Cannabis not shown as there was no cause-specific or excess mortality.

Neurological disorders

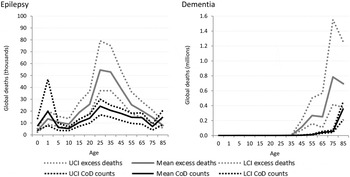

Cause-specific death estimates are more substantial for neurological disorders (Fig. 5) resulting in a less dramatic gap between cause-specific and excess deaths. This is likely indicative of neurological disorders being recognised more readily as the primary cause of death.

Fig. 5. Numbers of cause-specific and excess deaths attributed to neurological disorders in 2010, by age and with upper and lower 95% CI. *Note: Migraine not shown as there was no cause-specific or excess mortality.

Similar to intellectual disability, epilepsy was modelled as an envelope disorder in GBD 2010 with idiopathic epilepsy and epilepsy secondary to a range of causes, including meningitis, neonatal tetanus, iodine deficiency and a variety of birth complications, being modelled as one disorder. Cause of death modelling estimated nearly 180 000 deaths due to epilepsy in 2010 while natural history models show us about 300 000 excess deaths in fact took place. The proportion of deaths attributable to different causes differ by region and GBD 2010 showed sub-Saharan African populations had the highest death rate due to epilepsy. Around 2.1 million excess deaths worldwide were estimated from dementia for 2010, yet less than 500 000 were attributed to dementia as the primary cause of death.

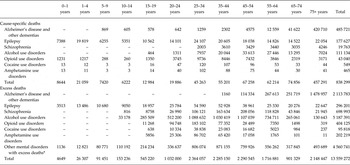

Table 2 shows that the cause-specific deaths and excess deaths directly coded to MNSDs are relatively similar up to 4 years of age but then rise sharply: in children aged 5–9 years there were 7420 cause-specific deaths compared with more than 91 000 excess deaths in the same age group. Alcohol use disorders explained the highest number of excess deaths (5.2 million): 38% of all excess deaths due to mental and neurological disorders in 2010. Considered together, the mental disorders for which no cause-specific deaths were attributed (bipolar disorder, major depression, autism and intellectual disability) explained more than 4.5 million deaths, equating to one third of all excess deaths in 2010.

Table 2. Number of cause-specific and excess deaths, by age for 2010

Note: larger than expected numbers in the 75+ age group may be an artefact of age groupings.

*Disorders with all-cause excess mortality but no cause-specific mortality (bipolar, autistic disorder, major depression and intellectual disability).

Counter-factual burden and CRA

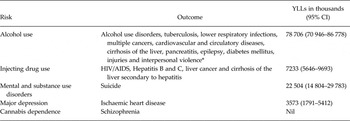

The reviews conducted as part of GBD 2010 collectively yielded sufficient evidence for several CRAs (see Table 3). Neurological disorders were not assessed as risk factors in GBD 2010.

Table 3. MNSDs included as risk factors in GBD 2010 CRAs with attributable YLLs for health outcomes in 2010

*Source: Table 1. From Lim, Vos, Flaxman et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet no. 380 (9859):2224–2260.

For mental disorders, a number of associations were investigated but data limitations meant that only suicide and IHD were able to be included as outcomes for mental disorders (suicide) and MDD (IHD) (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter, Charlson, Somerville and Whiteford2011a ; Charlson et al. Reference Charlson, Stapelberg, Baxter and Whiteford2011; Ferrari et al. Reference Ferrari, Norman, Freedman, Baxter, Pirkis, Harris, Page, Carnahan, Degenhardt, Vos and Whiteford2014). Collectively, mental and substance use disorders are estimated to be responsible for about 22 million YLLs due to death by suicide (Ferrari et al. Reference Ferrari, Norman, Freedman, Baxter, Pirkis, Harris, Page, Carnahan, Degenhardt, Vos and Whiteford2014). The CRA of major depression as a risk factor for ischaemic heart disease estimated an attributable to burden of about 3.5 million YLLs (Charlson et al. Reference Charlson, Moran, Freedman, Norman, Stapelberg, Baxter, Vos and Whiteford2013).

Injecting drug use was considered as a risk factor for a number of outcomes, including blood borne viruses and liver disease, and collectively accounted for over 7 million YLLs in attributable burden. Interestingly, and despite common preconceptions, GBD results did not show any mortality-related burden from schizophrenia that could be attributed to cannabis dependence. Alcohol use was the biggest contributor with nearly 80 million attributable YLLs estimated across a number of health outcomes.

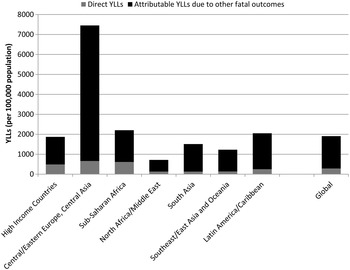

Figure 6 shows the considerable additional burden when MNSDs are considered as underlying contributors to other health outcomes. Given the large estimate of mortality-related burden attributed to alcohol dependence, it is expected that, when aggregating YLLs, the regions with the largest attributable burden will be those which have highest rates of alcohol dependence, i.e., Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Sub-Saharan Africa experiences large communicable disease YLLs attributable to alcohol dependence as a result of the continuing high prevalence of communicable disease in relation to other regions.

Fig. 6. YLL rates (per 100 000 population) for deaths directly associated with MNSDs and indirect deaths for MNSDs as risk factors for other health outcomes, 2010. Note: Indirect deaths include deaths attributable to alcohol and drug use from CRA study; suicide deaths attributable to mental and substance use disorders; and ischaemic heart disease deaths attributable to major depression (see Table above for specific fatal outcomes)

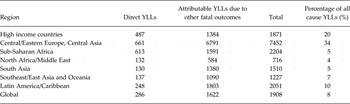

By incorporating the additional YLLs estimated using CRAs into the overall contribution of mental, substance use and neurological disorders to all cause YLLs (Table 4) we can see a dramatically different picture to that painted in Appendix 1 where YLL contributions appeared negligible in many cases.

Table 4. Revised MNS disorder YLLs (per 100 000 population) as a % of all cause YLLs after the inclusion of CRA burden estimates

Contributions across regions vary in accordance with the epidemiological profile of disorders within each region, not only of mental, substance use and neurological disorders but also the health outcomes assessed in CRAs. For example, the relatively large contribution in HICs and Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia likely to be reflective not only of high prevalence of substance use, but also of cardiovascular disease (CVD) which was assessed as an outcome of major depression and alcohol use. In contrast, the relatively lower contribution in sub-Saharan Africa is likely reflective of comparatively lower rates of both substance use disorders (risk factors) and chronic diseases such as CVD (health outcomes). If neurological disorders were assessed as risk factors for other health outcomes using CRAs this picture may have looked different for sub-Saharan Africa where YLLs attributable to neurological disorders is higher than in other regions in the world.

Discussion

A relatively small YLL burden was attributable to MNSDs in GBD 2010; however, numbers of excess deaths derived from natural history of disease models clearly demonstrate the high degree of mortality associated with these disorders. Quantifying the independent contributions of mental and substance use disorders to poor health outcomes through methods such as the CRA is restricted by data availability and methodological challenges such as establishing causal relationships (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter, Charlson, Somerville and Whiteford2011a ); nevertheless, there is a growing body of literature which can help us develop hypotheses around these contributions by observing the risks associated with excess death in individuals with mental and substance use disorders.

The relationship between mental disorders and suicide has long been recognised (Li et al. Reference Li, Page, Martin and Taylor2011). Mental disorders have also been linked to higher rates of death due to coronary heart disease, stroke, type II diabetes, respiratory diseases and some cancers (Hoyer et al. Reference Hoyer, Mortensen and Olesen2000; Crump et al. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist2013). The relationship between mental disorders and physical disease, leading to premature death, is complex. People with mental disorders have an increased risk of death in several ways, for example people with MDD are more likely to develop CVD (Charlson et al. Reference Charlson, Stapelberg, Baxter and Whiteford2011). Psychotropic medications can negatively impact on cardiovascular and metabolic health (De Hert et al. Reference De Hert, Detraux, Van Winkel, Yu and Correll2012). Obesity and metabolic disturbances are primary risk factors for CVD and type II diabetes, and are two- to threefold more common in people with mental disorders compared with the general population (Scott & Happell, Reference Scott and Happell2011). Major modifiable risk factors for chronic disease, such as smoking (Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Mitrou and Zubrick2009), poor diet and physical inactivity (Kilbourne et al. Reference Kilbourne, Rofey, Mccarthy, Post, Welsh and Blow2007; Shatenstein et al. Reference Shatenstein, Kergoat and Reid2007) and substance abuse (Scott & Happell, Reference Scott and Happell2011), are overrepresented in people with mental disorders and these may be consequences of symptoms of MNSDs, medication effects and poor emotional regulation (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Wu, Saunders, Benjet, He, Lepine, Tachimori, Van Korff, Alonso, Chatterji and He2013).

Interestingly, while schizophrenia was the condition among these mental disorder among for which YLLs were attributed, the number of YLLs were very small compared with the excess mortality associated with the disorder. Our finding of high excess mortality in people with schizophrenia is in line with that found in the previous research (Laursen, Reference Laursen2011; Crump et al. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist2013; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013). Data linkage studies have shown that the majority of deaths in people with schizophrenia are due to chronic disease with CVD accounting for more than one-third of all premature deaths, while unnatural causes, including suicide, homicide and accidents account for just under 15% of excess deaths (Crump et al. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist2013; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013). Despite concerns over the side-effects of antipsychotic medication, lack of antipsychotic treatment has been linked with higher all-cause mortality rates (HR 1.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20–1.76), with highest risks attributed to cancer (HR 1.94, 95% CI 1.13–3.32) and suicide (HR 2.07, 95% CI 0.73–5.87; Crump et al. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist2013). Poly-pharmacy and discontinuation of medication also appear to increase risk of all-cause death (Joukamaa et al. Reference Joukamaa, Heliovaara, Knekt, Aromaa, Raitasalo and Lehtinen2006; Haukka et al. Reference Haukka, Tiihonen, Härkänen and Lönnqvist2008).

Research from the UK suggests that the excess mortality rate in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are comparable (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Hayes, Perera, Broadbent, Fernandes, Lee, Hotopf and Stewart2011). In a recent study, it was estimated that about 80% of premature death in people with bipolar disorder is due to physical disease, almost half of which is explained by CVD (Westman et al. Reference Westman, Hallgren, Wahlbeck, Erlinge, Alfredsson and Osby2013). Just under 20% of premature deaths were explained by unnatural causes (suicide, homicide and unintentional injuries; Westman et al. Reference Westman, Hallgren, Wahlbeck, Erlinge, Alfredsson and Osby2013).

People with developmental disorders are at twice the risk of premature death compared with the general population (Mouridsen et al. Reference Mouridsen, Bronnum-Hansen, Rich and Isager2008). Elevated death rates in autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) are due to several causes, including accidents, respiratory diseases and seizures (Shavelle et al. Reference Shavelle, Strauss and Pickett2001; Mouridsen et al. Reference Mouridsen, Bronnum-Hansen, Rich and Isager2008). The elevated mortality risk associated with ASD may be due more to the presence of comorbid medical conditions, particularly epilepsy, and intellectual disability rather than ASD itself (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Harrington, Chang and Connors2008; Bilder et al. Reference Bilder, Botts, Smith, Pimentel, Farley, Viskochil, Mcmahon, Block, Ritvo, Ritvo and Coon2013).

Individuals with intellectual disability are expected to have, on average, a life expectancy of 7–12 years less than the general community and life expectancy is dramatically lower in those more severe disability and those with a genetic disorder (e.g., Down syndrome) (Bittles et al. Reference Bittles, Petterson, Sullivan, Hussain, Glasson and Montgomery2002). Intellectual disability is associated with greater tendency towards obesity and physical inactivity compared with the general population, and enhanced predisposition to mental disorders, osteoporosis, thyroid disorders, non-ischaemic heart disease and early onset of dementia (Bittles et al. Reference Bittles, Petterson, Sullivan, Hussain, Glasson and Montgomery2002). In HIC, causes of death in people with intellectual disability are generally coded under congenital abnormalities, diseases of the nervous system and sense organs, mental disorders and respiratory disease (Tyrer & McGrother, Reference Tyrer and Mcgrother2009). Information on causes of death in LMIC populations is sparse.

Children with ADHD or CD are two to three times more likely to experience unintentional injuries requiring medical attention compared with children without behavioural disorders (Rowe et al. Reference Rowe, Maughan and Goodman2004; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Harrington, Chang and Connors2008). The injuries most commonly reported included burns, poisoning and frac(Rowe et al. Reference Rowe, Maughan and Goodman2004). Adolescents and young adults with inattention disorders are more likely to be involved in traffic accidents (Jerome et al. Reference Jerome, Segal and Habinski2006). Adults who were identified with behavioural disorders in childhood are at higher risk of cigarette smoking, binge-drinking (ADHD) and obesity (CD) (von Stumm et al. Reference Von Stumm, Deary, Kivimäki, Jokela, Clark and Batty2011) in later life. Despite the strong evidence for an association between childhood behavioural disorders and poorer health outcomes, there is insufficient information available to model the natural history of disease and thus no estimates quantifying excess mortality in this group at population level.

Another important disorder demonstrating an apparent absence of excess-mortality in GBD 2010 is the umbrella anxiety disorders group. This was a necessary choice as the information on excess mortality in anxiety disorders was found to be inconsistent with some anxiety disorders; however, severe presentations such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), have previously been associated with increased deaths caused by ischaemic heart disease (IHD), neoplasms and intentional and unintentional injuries (Ahmadi et al. Reference Ahmadi, Hajsadeghi, Mirshkarlo, Budoff, Yehuda and Ebrahimi2011; Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013).

While light-to-moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with lower rates of some disease such as diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease, heavy consumption has been associated with increased rates of chronic disease, including cancer, MNSDs, cardiovascular disease, liver and pancreas diseases (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe, Parry, Patra, Popova, Poznyak, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov and Taylor2010a ). There is evidence for alcohol as a carcinogen in humans, with particularly strong causal links established between alcoholic beverage consumption and oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, liver, colorectal and female breast cancers (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe, Parry, Patra, Popova, Poznyak, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov and Taylor2010a ). A consistent relationship has also been found between heavy alcohol consumption and epilepsy (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe, Parry, Patra, Popova, Poznyak, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov and Taylor2010a ) and it is also implicated in development of depression and personality disorders, although the direction of causality and effect of confounding factors remains uncertain (Rao et al. Reference Rao Um, Daley and Hammen2000; Rohde et al. Reference Rohde, Lewinsohn, Kahler, Seeley and Brown2001). Risk of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, sudden cardiac death and other cardiovascular outcomes is elevated in those with alcohol use disorders (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe, Parry, Patra, Popova, Poznyak, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov and Taylor2010a ). The relationship between alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis is well recognised, but alcohol use disorders appear more strongly related to cirrhosis mortality v. morbidity as it negatively affects the course of existing liver disease (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Taylor, Mohapatra, Irving, Baliunas, Patra and Roerecke2010b ). Heavy alcohol use is also related to higher rates of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, and unintentional and intentional injury, with strong evidence for a dose–response relationship (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe, Parry, Patra, Popova, Poznyak, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov and Taylor2010a ).

Excess and premature deaths in illicit drug users occur in several ways. Most obvious is the acute toxic effects of illicit drug use which may lead to overdose – the cause-specific deaths generally captured by the ICD-coding system. In addition, a substantial number of deaths are likely due to the more indirect effects of intoxication resulting in accidental injuries and violence. There are a plethora of adverse health outcomes with elevated risks of premature mortality for which illicit drug dependence is an important contributor. These outcomes are often chronic and include cardiovascular disease, liver disease and a range of mental disorders including psychosis. Suicide is an important outcome, particularly for opioid users where an SMR of approximately 14 has been reported in two separate reviews (Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Bucello, Mathers, Briegleb, Ali, Hickman and Mclaren2011; Chesney et al. Reference Chesney, Goodwin and Fazel2014). Injection of drugs, most common in opioid dependence, carries a high risk of blood-borne bacterial and viral infections, notably HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C (Mathers et al. Reference Mathers, Degenhardt, Ali, Wiessing, Hickman, Mattick, Myers, Ambekar and Strathdee2010; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Mathers, Cowie, Hagan, Des Jarlais, Horyniak and Degenhardt2011).

Epilepsy is associated with two- to threefold higher than mortality in the general community, particularly in childhood onset epilepsy, with the highest standardised mortality ratio encountered in the first year or two after diagnosis (Preux & Druet-Cabanac, Reference Preux and Druet-Cabanac2005; Sillanpaa & Shinnar, Reference Sillanpaa and Shinnar2010; Neligan et al. Reference Neligan, Bell, Shorvon and Sander2010; Trinka et al. Reference Trinka, Bauer, Oberaigner, Ndayisaba, Seppi and Granbichler2013). Common causes of premature mortality in epilepsy include acute symptomatic disorders (e.g., brain tumour and stroke), sudden unexpected death, suicide and accidents (Hitiris et al. Reference Hitiris, Mohanraj, Norrie and Brodie2007). Roughly 85% of people with epilepsy live in LMICs and here the risk of premature mortality is highest (Carpio et al. Reference Carpio, Bharucha, Jallon, Beghi, Campostrini, Zorzetto and Mounkoro2005; Diop et al. Reference Diop, Hesdorffer, Logroscino and Hauser2005; Newton & Garcia, Reference Newton and Garcia2012; Jette & Trevathan, Reference Jette and Trevathan2014) from status epilepticus, drowning and burns associated with poor access to and/or compliance with medical treatment, cognitive impairment and age (Jilek & Rwiza, Reference Jilek and Rwiza1992; Kamgno et al. Reference Kamgno, Pion and Boussinesq2003; Mu et al. Reference Mu, Liu, Zhang, Si, Hu, Fang, Gao, He, Li, Wang, Wu, Sander and Zhou2011; Ngugi et al. Reference Ngugi, Bottomley, Fegan, Chengo, Odhiambo, Bauni, Neville, Kleinschmidt, Sander and Newton2014).

As with mental disorders, excess mortality in dementia has been associated with functional disability leading to lifestyle factors (e.g., poor eating behaviours, physical inactivity and poor hygiene) and comorbid or underlying physical conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and neoplasms (Guehne et al. Reference Guehne, Riedel-Heller and Angermeyer2005; Llibre Rodríguez et al. Reference Llibre Rodríguez, Valhuerdi, Sanchez, Reyna and Guerra2008). Infections, particularly pneumonia and the complications of urinary tract infections, frequently lead to death in people with dementia (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Teno, Kiely, Shaffer, Jones, Prigerson, Volicer, Givens and Hamel2009).

Strategies for reducing mortality associated with MNSDs are primarily related to preventing onset of disorders, reducing case fatality, and preventing onset of fatal sequela. There is growing evidence that excess mortality in people in mental and substance use disorders can be reduced through existing evidence-based treatments and improved screening and treatment for chronic disease. There is some evidence that collaborative care by community-based health teams has the potential to reduce overall death as well as suicide deaths (Malone et al. Reference Malone, Marriott, Newton-Howes, Simmonds and Tyrer2007; Dieterich et al. Reference Dieterich, Irving, Park and Marshall2010). The use of collaborative care models to improve physical health in people with MNSDs is growing in developed countries and these have demonstrated a range of positive health outcomes including reduced cardiovascular risk profiles (Druss et al. Reference Druss, Von Esenwein, Compton, Rask, Zhao and Parker2010). The effectiveness of these strategies in preventing premature mortality in LMIC populations has yet to be tested but this may be a cost-effective approach to treatment where trained mental health clinicians are scarce.

To improve life expectancy in people with comorbid mental and physical health issues requires proactive screening and adequate care for chronic disease. Screening and prevention of metabolic risk factors is essential. Strategies for early cancer detection should be prioritised and models of care developed to ensure that people with MNSDs receive the same level of physical health care and treatment as the rest of the population.

Psychiatric treatments, specifically pharmacotherapies, may have some protective effect against excess mortality (Weinmann et al. Reference Weinmann, Read and Aderhold2009) although evidence suggests that this depends on use of medications according to best practice guidelines (Cullen et al. Reference Cullen, Mcginty, Zhang, Dosreis, Steinwachs, Guallar and Daumit2013). In contrast, some second generation antipsychotics may actually pose an elevated risk mediated by metabolic side effects (Newcomer, Reference Newcomer2005; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Hopkins, Peveler, Holt, Woodward and Ismail2008; Rummel-Kluge et al. Reference Rummel-Kluge, Komossa, Schwarz, Hunger, Schmid, Lobos, Kissling, Davis and Leucht2010).

Much of the disease burden due to opioid dependence and injecting drug use could be averted by scaling up needle and syringe programs (NSPs), opioid substitution treatment and HIV antiretroviral therapy (Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Mathers, Vickerman, Rhodes, Latkin and Hickman2010; Turner et al. Reference Turner Km, Hutchinson, Vickerman, Hope, Craine, Palmateer, May, Taylor, De Angelis, Cameron, Parry, Lyons, Goldberg, Allen and Hickman2011). Both methadone and buprenorphine (the two most commonly used medications) have been listed on the WHO's List of Essential Medicines (World Health Organization, 2005) as core medications for the treatment of opioid dependence (Mattick et al. Reference Mattick, Kimber, Breen and Davoli2008, Reference Mattick, Breen, Kimber and Davoli2009). OST reduces mortality among opioid-dependent people (Davoli et al. Reference Davoli, Forastiere, Abeni, Rapiti and Perucci1994; Caplehorn & Drummer, Reference Caplehorn and Drummer1999; Brugal et al. Reference Brugal, Domingo-Salvany, Puig, Barrio, Garcia De Olalla and De La Fuente2005; Darke et al. Reference Darke, Degenhardt and Mattick2006; Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Degenhardt, Mattick, Ali, White and O'Brien2008; Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Randall, Hall, Law, Butler and Burns2009b ), with time spent in treatment halving mortality compared with that in time spent out of treatment (Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Bucello, Mathers, Briegleb, Ali, Hickman and Mclaren2011). A large evaluation study in multiple countries, including LMICs, has demonstrated that OST is effective in reducing opioid use and injecting risk behaviours and improving physical and mental wellbeing (Lawrinson et al. Reference Lawrinson, Ali, Buavirat, Chiamwongpaet, Dvoryak, Habrat, Jie, Mardiati, Mokri, Moskalewicz, Newcombe, Poznyak, Subata, Uchtenhagen, Utami, Vial and Zhao2008). There is increasing evidence that not only HIV (Degenhardt et al. Reference Degenhardt, Mathers, Vickerman, Rhodes, Latkin and Hickman2010) but also HCV (Turner et al. Reference Turner Km, Hutchinson, Vickerman, Hope, Craine, Palmateer, May, Taylor, De Angelis, Cameron, Parry, Lyons, Goldberg, Allen and Hickman2011) burden can been reduced through NSPs; HCV burden can also be decreased by effectively treating chronic HCV (Turner et al. Reference Turner Km, Hutchinson, Vickerman, Hope, Craine, Palmateer, May, Taylor, De Angelis, Cameron, Parry, Lyons, Goldberg, Allen and Hickman2011). The release of more effective and less toxic HCV drugs is expected to dramatically improve what have been extremely low rates of HCV treatment uptake by people who inject drugs (Swan, Reference Swan2011).

There is also scope for reducing the risk of overdose among people who continue to use opioids. There is increasing evidence that the provision of the opioid antagonist naloxone to opioid users enables peers to effectively intervene if overdoses occur (Galea et al. Reference Galea, Worthington, Piper, Nandi, Curtis and Rosenthal2006; Sporer & Kral, Reference Sporer and Kral2007). Additional strategies may include: education of users about the risks of overdose (especially high risk periods such as post-release from prison or after a period of abstinence), and motivational interviews with users who have recently overdosed (Sporer, Reference Sporer2003). Safe injecting rooms have been proposed as an additional strategy to reduce overdose, although their population reach is likely to be more limited (Hall & Kimber, Reference Hall and Kimber2005). There is evidence that psychosocial interventions including self-help programmes and cognitive behavioural therapy are effective in psychostimulant dependence (Baker et al. Reference Baker, Lee and Jenner2005; Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Soares, Farrell and Silva De Lima2007).

In low-income regions, mortality in epilepsy patients is largely due to preventable causes (Diop et al. Reference Diop, Hesdorffer, Logroscino and Hauser2005; Jette & Trevathan, Reference Jette and Trevathan2014). Yet, the treatment gap is more than 75% in low-income countries, and more than 50% in many lower and upper middle-income countries (Jette & Trevathan, Reference Jette and Trevathan2014). Legislation to ensure availability of affordable and efficacious anti-seizure medications, clinician education in prescribing antiepileptic medications, and patient education regarding the importance of medical adherence is critical to alleviate the epilepsy treatment gap. Cost-effective epilepsy treatments are available and accurate diagnosis can be made without costly technical equipment. Targeting epilepsy risk factors, including more common structural and metabolic causes of epilepsy will likely decrease mortality risk as well. In addition, education and information provision on safe lifestyle habits in epilepsy patients (i.e., avoiding fires, swimming and driving in those with active convulsive epilepsy) will clearly be beneficial. Education to dispel myths associated with epilepsy among employers and teachers may empower those with epilepsy to seek treatment.

Mortality in dementia patients is commonly by preventable medical conditions, including infections. Caregiver education and support services regarding proper care of patients with cognitive decline will likely decrease infection rates and thus, mortality. Government financial support for healthcare services and caregiver support would also benefit this population. Strategies to enhance nutrition, as well as monitoring and treatment of vascular risk factors including high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, obesity and diabetes, are important measures as well.

Limitations of the study

Quantifying mortality presents several challenges. Cause of death data is affected by multiple factors, including: certification skills among physicians, diagnostic and other data available for completing the death certificate, cultural variations in choosing and prioritising the cause of death, and institutional parameters for governing mortality reporting (Lozano et al. Reference Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, Lim, Shibuya, Aboyans, Abraham, Adair, Aggarwal and Ahn2012). In LMIC populations, where many deaths are not medically certified, different data sources and diagnostic approaches are used (e.g., from surveillance systems, psychological autopsy work and disease registries) to derive cause of death estimates (Lozano et al. Reference Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, Lim, Shibuya, Aboyans, Abraham, Adair, Aggarwal and Ahn2012). The implication is that cause of death assessments are subject to uncertainty; a good illustration is the widely debated difference in maternal death estimates by GBD and by the United Nations (Byass, Reference Byass2010).

Cause of death data also provided estimates of deaths due to MNSDs that were not captured within the main GBD 2010 categories. The decision was taken to create residual categories to reflect the additional mortality not captured within specific disorders. Deaths and YLLs were calculated for: ‘other’ mental disorders (16 140 deaths equating to 5.4 YLLs per 100 000 persons); ‘other’ drug use disorders (33 ,561 deaths equating to 22.5 YLLs per 100 000 persons); and ‘other’ neurological disorders (481 142 deaths and 231.6 YLLs per 100 000). The modelling strategies for these residual groups do not allow calculation of excess mortality for comparison as done throughout this paper however the YLL estimates for these groups are exceptionally high.

Mortality directly related to MNSDs is particularly difficult to capture in cause of death data due to the complex web of causality which link them with other physical disorders. Thus it becomes very important to identify and quantify the not inconsiderable excess premature mortality in people with MNSDs through understanding the pathway between these disorders and fatal sequelae.

Although valuable, the CRAs undertaken as part of GBD 2010 provide an incomplete picture. There are almost certainly deaths where we may not have enough information to parse out what is causally related or what is due to confounding. Assuming multiple risk factors are independent of each other is also a limitation as done in CRA methodology. A more accurate quantification of the joint effects of multiple risk factors, that is what explains the difference between excess and cause-specific deaths, is an important area for future research.

Conclusion

Despite the challenges in quantifying causal mortality in MNSDs it is abundantly clear that the mortality-associated disease burden of mental, substance use and neurological disorders is significant. The continuing life expectancy gap in persons with these disorders represents a lack of parity between this portion of the population and the community in general (Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2013). People with MNSDs face additional barriers to physical health care because of stigma within the healthcare system, the ‘silo’ effect between mental and physical health care caused by overspecialisation, and diagnostic overshadowing of physical health issues by presence of mental disorders (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Thorpe and Smith2013). Differential access to ‘usual’ care for this group leads to poorer outcomes in terms of health loss and mortality and incurs high costs in health care provision (Centre for Mental Health, 2010). Further research and development of new strategies for reducing mortality associated with MNSDs is needed.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material referred to in this article can be found at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/EPS.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Disease Control Priorities (3rd Edition) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Financial support

Core funding for the Queensland Centre of Mental Health Research is provided by the Queensland Department of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.