INTRODUCTION

In his account of Pope Sixtus IV's deeds, apostolic secretary Sigismondo dei Conti (d. 1512) included the extensive decorative program commissioned by the pope for his new chapel. Describing the Sistine Chapel's decoration, Conti briefly mentions the wall frescoes representing the lives of Moses and Christ.Footnote 1 His highest praise refers to a now lost fresco by Pietro Perugino (ca. 1450–1523) that depicted the apocryphal episode of Mary corporally ascending into heaven three days after her death (fig. 1): “[Sixtus] had an image of the Assumed Virgin painted in heaven, expressed with so much mastery that it seemed as if she was raised up from earth and lifted up in the air.”Footnote 2 The Assumption of the Virgin, located directly above the Sistine Chapel's altar (fig. 2), served as the visual centerpiece during the papal liturgy until it was destroyed, when Michelangelo painted the Last Judgment (1536–41).

Figure 1. Assumption of the Virgin, drawing after Pietro Perugino's Sistine Chapel altarpiece, late fifteenth century. Pen and ink with brown wash, heightened with white, 8.2 x 10.7 in. Photo courtesy of Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Figure 2. Reconstruction of the Sistine Chapel's altar wall in 1483. From Johannes Wilde, “The Decoration of the Sistine Chapel,” Proceedings of the British Academy 44 (Reference Wilde1958): plate VIb. Courtesy of Proceedings of the British Academy.

Two contemporary and seemingly accurate reproductions of the Assumption—a detailed drawing (fig. 1) and a miniature (fig. 3)—allow for the determination of the fresco's original appearance. This article presents the first sustained analysis of Perugino's altarpiece by reconstructing its ritual setting and relating it to Sixtus's efforts to increase the observance of Marian feast days, especially the feast of the Immaculate Conception. It also puts the fresco in dialogue with Rome's famous Assumption procession and examines how the pope's larger campaign to advance the universal cult of the Virgin intersected with local religious culture.

Figure 3. Giuliano Amadei (attributed), Celebration of a Papal Mass in the Sistine Chapel, 1484–92. Tempera on parchment (cutting), 4 x 6.4 in. Cliché CNRS-IRHT, © Bibliothèque du musée Condé, château de Chantilly.

I argue that Perugino's image of the Assumed Madonna, when perceived in the context of specific ritual movements and their attendant lighting effects, not only expressed the pope's devotion to the Virgin but also evoked Maria in sole (Madonna clothed in the sun). The metaphor appears frequently in the literature, music, and visual arts associated with Sixtus's devotion to the Immaculate Virgin. In this context, the radiant Madonna expressed Mary's likeness to Christ and the singularity of her unstained body, preserved at conception from original sin—a belief promoted by Immaculists—and exalted after death in the heavenly spheres. The rites conducted during Sixtus's public inauguration of his chapel on the 1483 feast of the Assumption underlined the symbolic ties between the altarpiece and Maria in sole. The Assumption feast represented one of the most important events in the liturgical calendar of Rome, where devotion to Mary was well established.Footnote 3 An examination of the chapel's inauguration reveals how the altarpiece and its associated liturgy allowed Sixtus to temporarily expand a traditionally communal, local feast to include a ritual expression of the pope's spiritual privileges and authority.

Perceptions of the Sistine altarpiece were informed by what viewers had experienced in another sacred space constructed by Sixtus. During the very years when the pope had the Sistine Chapel built and decorated, he also erected a chapel in St. Peter's Basilica; this doubled as the basilica's choir and was intended to include Sixtus's tomb.Footnote 4 Importantly, Sixtus annually celebrated the feast of the Madonna's Conception in the St. Peter's chapel, and he commissioned Perugino to decorate the apse with a Marian fresco. Though the chapel was destroyed in 1609, a written description and two extant reproductions (figs. 4 and 5) establish the lost work's appearance.Footnote 5 Soon after Perugino completed the fresco in St. Peter's in 1479, he began his closely related Sistine Assumption.Footnote 6 Given the visual similarities between the two frescoes, the earlier work offers a useful point of comparison for an analysis of the latter. Moreover, important evidence allows for the reconstruction of the rites that unfolded before both images—specifically, the Conception feast in St. Peter's and the 1483 Assumption feast in the Sistine Chapel. Because these paintings were expressly executed for specific liturgical settings, the ways in which viewers perceived and interpreted them were impacted by these rituals. Thus, the following analysis of the rites, and of how their sensory components interacted with the frescoes, helps reconstruct the paintings’ reception.

Figure 4. Pope Sixtus IV's Conception Chapel in St. Peter's Basilica (detail), 1619–20. Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Barb. Lat. 2733, fol. 131r. © 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, reproduced by permission of Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved.

Figure 5. Giovanni Battista Ricci, Pope Sixtus IV's Conception Chapel in St. Peter's Basilica, ca. 1616–18. Fresco. Vatican Grottoes, Chapel of Santa Maria de Partorienti. © Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano.

Despite the fresco's crucial liturgical role, the Sistine Assumption has garnered considerably less scholarly interest than the extant fifteenth-century wall paintings. In his monumental study of the Sistine decorations (1901), Ernst Steinmann identified a typological relationship between the narrative cycles depicting the lives of Moses and Christ.Footnote 7 In 1965, L. D. Ettlinger criticized certain elements of Steinmann's study—specifically, the suggestion that several of the narrative scenes celebrated Sixtus's personal successes. According to Ettlinger, the paintings primarily express Sixtus's own vision of the papal office and convey an overarching message of papal primacy, an argument generally accepted by subsequent scholars.Footnote 8 The discovery of the frescoed inscriptions, or tituli, between 1965 and 1969 further clarified the nature of the chapel's typological schema and also supported Ettlinger's thesis.Footnote 9 In another book on the wall frescoes, Carol Lewine made an original but unconvincing attempt to link the choice and sequence of the side wall images to the biblical passages read in mass during the Lenten season.Footnote 10 Instead, as Peter Howard has demonstrated, the choice of episodes in the intricate narrative scenes reflects the same methodologies employed in the “art of preaching.” His study further proves that the frescoes employed sophisticated theology to communicate important aspects of Sixtus's papal agenda.Footnote 11 Several articles relate the chapel's original decorations to Mariological themes. In 1988, Rona Goffen interpreted the imagery in light of Sixtus's Franciscan identity.Footnote 12 She also suggested that the chapel's dedication to the Assumption indirectly tied it to the Immaculate Conception.Footnote 13 Other scholars, drawing on Goffen, have observed in passing that Perugino's altarpiece should be considered in the context of Sixtus's Immaculist leanings.Footnote 14 Most recently, Florian Métral presented a closer examination of the chapel's Mariology, and convincingly suggested that Piermatteo d'Amelia's ceiling—later replaced by Michelangelo—represented the sky on the night of the Assumption feast.Footnote 15 The present study complements and extends this research into how Sixtus's theological commitments underpinned the Sistine's imagery. Perugino's understudied altarpiece is the chapel's most prominent expression of Franciscan and Sistine Marianism, and the key to understanding the chapel's Mariology. This article also considers another hitherto unexplored topic: how the altarpiece's subject and the chapel's dedication placed this liturgical space and Sistine theology in conversation with the local Roman community.

My analysis perceives the fresco in the context of the sensorial conditions specific to the papal liturgy, and builds on recent interdisciplinary work that explores the intersection of images with ritual movements, music, lighting, and other sensory components in the construction of sacred space.Footnote 16 A handful of publications have demonstrated that the sixteenth-century artworks executed for the Sistine were designed with their original sensorial environment in mind.Footnote 17 Other studies have examined the decorations in the Vatican Palace through the lens of liturgy and ceremony,Footnote 18 and a recent edited volume has considered how music and performance shaped Rome's sacred and social spaces.Footnote 19 Little is known, however, about how the Sistine Chapel's earlier wall paintings interacted with the performances that unfolded within the sacred space. By focusing on the central liturgical image, I recover salient aspects of the viewers’ reception of the newly renovated Sistine. My interest lies primarily in the optical effects produced by the liturgical lighting, since such a reconstruction reveals an affinity between the Sistine fresco and the imagery pervading Immaculist devotional culture in the period. The resultant study aims to enrich understanding of the experiential and symbolic elements of the liturgy performed during significant moments in the papal court's liturgical calendar and in what was arguably one of the most important chapels in Latin Christendom.

In what follows, I consider the Sistine Chapel altarpiece in the context of a highly contested theological concept. The Virgin's Immaculate Conception did not become doctrine until 1854 and centered on the proposition that she was conceived free from original sin.Footnote 20 During the late Middle Ages, the Franciscans were the primary proponents of Immaculist theology, and their efforts pitted them against the Dominicans. Vitriolic attacks and accusations of heresy were launched between the two factions, and the enduring debate intensified during Sixtus's papacy (1471–84).Footnote 21 Before becoming Pope Sixtus IV, Franciscan Francesco della Rovere had achieved prominence as a friar in the Franciscan Order, thanks in large part to the apologetic texts he had composed on the Immaculate Conception and on other theological issues important to the Friars Minor but perceived by the Dominicans as controversial.Footnote 22 By analyzing the Sistine altarpiece in relation to this theme, this study demonstrates how a pope's theological commitments could shape the visual, liturgical, and devotional aspects of the papal court.

POPE SIXTUS IV AND THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION

Caution permeated Sixtus's campaign to boost the popularity of the Immaculate Conception, and he was careful not to commission artwork that explicitly promoted the Immaculist stance. The iconography of the Marian frescoes adorning the Sistine Chapel and St. Peter's Conception Chapel follows this trend and reflects Sixtus's larger policy governing his endorsement of the Immaculate Virgin. Throughout much of his ecclesiastical career, the future pope exhibited a fierce devotion to the Virgin. He directly sponsored the construction or renovation of three Marian churches in Rome—Santa Maria del Popolo, Santa Maria della Pace, Santa Maria del Buon Aiuto—and his promotion of the Virgin's cult helped drive the surge of Marian images that were venerated and produced in late Quattrocento Rome.Footnote 23 He spent approximately eighteen years at Sant'Antonio in Padua, which was home to a contingent of friars strongly in favor of the concept of the Immacolata.Footnote 24 During his tenure at the Santo, he wrote a sermon that was delivered by Bishop Fantino Dandolo (1379–1459) on 8 December 1448, the feast of the Immaculate Conception.Footnote 25 Underpinning this sermon was a controversial theological tenet that had sparked a complex debate primarily involving two camps: the Immaculists, largely represented by the Franciscan Order, and the Maculists, with whom the Dominicans identified. The main point of consternation between the opposing groups was whether Mary had ever been subjected to original sin. The Dominicans followed Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225–74), who declared that the Virgin, although conceived in original sin, was sanctified in the womb post-conception and, as such, was born sinless.Footnote 26 Immaculists, such as Sixtus, followed the Franciscan theologian John Duns Scotus (1265/66–1308), who argued that, from the beginning, God intended to express his eternal love through the Incarnation. Thus, God necessarily conceived of both mother and son at the same moment, just prior to creation and original sin.Footnote 27

The debate over the Madonna's conception raised fundamental questions regarding the universality and nature of original sin and humanity's shared need for Christ's redemption.Footnote 28 Belief in Mary's immaculacy also heightened the importance of Christ's body by elevating the purity of the womb that contained him.Footnote 29 By the fifteenth century, European rulers were invested in the controversy and the papacy had begun receiving requests to resolve the matter.Footnote 30 In 1439, the Council of Basel addressed the issue and proclaimed the Immaculate Conception doctrine. Though soon deemed invalid, this ruling fed the fires of the dispute. Accusations of heresy and schism continued to be launched against both sides.Footnote 31 The conflict reached a crisis in 1475, when the future Minister General of the Dominicans, Vincenzo Bandelli (1435–1506), published an acrimonious text against the Immaculate Conception that sparked such outrage from the Immaculists that Sixtus was finally obliged to intervene. The pope organized a debate in Rome in 1477 between Bandelli and Franciscan Minster General Francesco Sansone (1414–99), who, according to Sixtus, offered a more compelling case.Footnote 32 The pope then transformed the debated feast into a more officially recognized celebration.

Liturgical offices for Marian feast days were central components in Sixtus's larger campaign to promote the Virgin's cult, specifically the Immaculate Conception. In 1477, Sixtus issued the bull Cum Praecelsa, which conceded indulgences to all who participated in the newly designed office written by Franciscan friar Leonardo Nogarolo (d. 1486).Footnote 33 Additionally, in 1480, the pope authorized a Conception liturgy composed by Franciscan Bernardino de’ Busti (ca. 1450–ca. 1513).Footnote 34 Prior to these two offices, the feast of the Immaculate Conception was typically observed by making slight adjustments to the same mass said on the occasion of the Virgin's Nativity (September 8).Footnote 35 Significantly, Sixtus's support of the two texts clearly distinguished the Immaculate Conception from other Marian festivals by endowing it with its own custom-tailored liturgical identity. The pope also issued at least twelve briefs that granted indulgences to the faithful who participated in the feast of the Conception at certain churches and chapels throughout Europe.Footnote 36

Sixtus's promotion of the feast found favor among many in the larger church community. At the end of the fifteenth century, the Sorbonne required all graduating students to take an oath in support of the Immaculate Conception, a practice that other universities quickly adopted.Footnote 37 New confraternities devoted to the Immacolata were established, and images, poetry, and music celebrating Mary's immaculacy were created and diffused.Footnote 38 Sixtus's promotion of the Immaculate Conception had an impact on the dissemination and iconographical development of Marian imagery throughout Europe. The Maria in sole image, discussed below, rose in popularity at the end of the fifteenth century and eventually became one of the most familiar religious images in the early modern period.Footnote 39

Following Sixtus's decision to encourage the celebration of the Madonna's Conception, Dominicans continued to attack the popular, papally endorsed feast day.Footnote 40 In response, Sixtus composed two versions of the bull Grave Nimis in 1482 and 1483, both of which criticized preachers who condemned the Conception feast that “the holy Roman Church solemnly publicly celebrates . . . and has ordained.”Footnote 41 Both versions of the bull also forbade anyone to criticize or pronounce as heretical either the Immaculist or Maculist position. Sixtus's decision to not officially sanction Immaculist theology undoubtedly stemmed from a diplomatic desire to avoid division within the religious community.Footnote 42 In a similar vein, he never referred to the feast as the Immaculate Conception, but rather, and notably, only as the Conception. Dominicans opposed the application of this adjective to describe her conception.Footnote 43 Nevertheless, as the Dominicans surely noted, the feast promoted by Sixtus celebrated Mary's conception free from concupiscence, given that Nogarolo's office explicitly and repeatedly referred to her “Immaculate Conception.”Footnote 44

Sixtus thus walked a careful line between caution and outright promotion of the Immaculate Conception. He took a similar approach when commissioning artwork incorporating Marian iconography.Footnote 45 During his papacy, a fixed iconographic model for the Immaculate Virgin did not exist.Footnote 46 Only in the late sixteenth century did the Immaculate Conception take definitive visual form—in the figure of the Woman of the Apocalypse—traditionally shown framed by the sun with the moon at her feet.Footnote 47 Previously, Immaculist iconography often remained subtle and allusive, thanks to patrons’ general desire to avoid backlash from detractors.Footnote 48 Early Immacolata images are not always easily recognizable. Recent studies have convincingly argued that several well-known artworks expressed Immaculist themes found in the liturgical texts associated with Sixtus's campaign.Footnote 49 Subsequently, scholars studying the Immaculate Conception in art have had to consider the liturgical and devotional context of Marian images rather than rely solely on iconographic attributes. The two paintings under consideration in this article did not represent explicit images of the Immaculate Conception, but rather celebrated Mary's immaculacy when the perception was temporarily activated during the papal liturgy and when they were read within the framework of Sistine Mariology.

PERUGINO'S APSE FRESCO IN ST. PETER'S CONCEPTION CHAPEL

On the 1479 feast of the Conception, Sixtus issued a bull for his recently erected chapel in St. Peter's Basilica, which will be hereafter referred to as the Conception Chapel.Footnote 50 Situated on the left-hand side of the nave, the chapel was built on an approximately square plan with a projecting apse (fig. 6).Footnote 51 Inside the apse, the altar was adorned with a sacramental tabernacle that Baldassare Peruzzi (1481–1536) designed around 1524; while it is uncertain what stood on the altar prior to this, it is reasonable to assume that Peruzzi's tabernacle may have replaced an earlier one. In 1575, Michelangelo's Pietà took the tabernacle's place on the altar.Footnote 52 The chapel's apse itself was flanked by two porphyry columns that dated from Diocletian's reign (285–305 CE) and were adorned with reliefs depicting two emperors embracing, a motif symbolizing the ancient Roman tetrarchy.Footnote 53 The reliefs have been interpreted as reinforcing “the continuity of papal rule,” a concept similarly illustrated in Perugino's apse fresco, in which Peter presented Sixtus to the Madonna, the embodiment of the church.Footnote 54

Figure 6. Plan of Old St. Peter's with its relationship to the new basilica; the rectangle indicates the location of the Conception Chapel. Natale Bonifacio da Sebenico after Tiberio Alfarano, Almæ urbis Divi Petri veteris novique templi description (detail), 1590. Etching. London, The British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Perugino's Conception Chapel fresco adorned the apse's semi-dome and depicted Sixtus kneeling in the company of Saints Peter, Paul, Francis, and Anthony of Padua. Above the pope, Perugino painted the Madonna and Child seated in heaven against a golden backdrop; the Marian apparition was reminiscent of imagery representing Mary as the Woman of the Apocalypse from Revelations 12 and 13, who bore a son and appeared as “a woman clothed in the sun.”Footnote 55 Perugino's Conception Chapel fresco later served as a model for his Sistine Chapel altarpiece. In the Sistine Chapel, Mary stood inside a shimmering mandorla and appeared without the Christ Child, since the altarpiece represented the moment in which she was assumed into heaven, an event that the apostles and Sixtus witnessed from the ground below. While certain differences existed in the frescoes’ iconography and subject matter, important visual parallels placed them in dialogue with one another. For both chapels, Perugino had painted an image of the Madonna suspended in heaven, encircled by cherubim, and flanked by angelic musicians. Below each celestial scene and on the left-hand side of each painting, Sixtus appeared kneeling, with his papal tiara resting on the ground, and in the company of saints. Both saintly groups included Paul and Peter, who placed his hand atop the pope and presented him to the Virgin.

The 1479 bull for Sixtus's Conception Chapel dedicated it to the Madonna, Saint Francis, and Saint Anthony of Padua and granted indulgences to all who attended the celebrations held in the chapel for the feast of the Virgin's Conception and for the feasts of the two Franciscan saints. Women were normally barred from the chapel but were permitted to attend the papal masses on these special occasions.Footnote 56 The Conception liturgy performed inside the chapel was replete with imagery praising Mary's radiant splendor, and this section will examine how this motif resonated with Perugino's apse fresco. Although Sixtus issued bulls for two Conception offices, the following draws on the composition by Nogarolo, who had studied under Sixtus. The pope had confirmed this text prior to the Conception Chapel's opening.Footnote 57 In 1480, Sixtus released a far shorter bull for de’ Busti's office, for which he never conceded any indulgences.Footnote 58 Given Sixtus's preference for his former pupil's liturgy, the pope undoubtedly employed Nogarolo's office in his observance of the Conception.

The pope's festal celebrations in the Conception Chapel commenced when he attended vespers on December 7 with his household and several cardinals.Footnote 59 The Conception vigil held such import that it overshadowed Saint Ambrose, whose feast fell on that day; during vespers in 1483, apostolic secretary Jacopo Gherardi (1434–1516) reports that “the entire sermon [was] about the Conception with remembrance of Advent, [and] nothing about Saint Ambrose.”Footnote 60 The pope returned to the Conception Chapel the next day to attend morning mass with a larger retinue, including “patriarchs, the curia, and nobles, according to custom.”Footnote 61 On at least one occasion, Sixtus also observed matins in his chapel prior to mass.Footnote 62 After the ceremonies in the basilica, Sixtus journeyed at noon with a retinue of priests, prelates, and ambassadors to a building that he had recently reconstructed, the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo.Footnote 63 The rituals at the Marian sanctuary included a procession by the Roman Senate, whose members were required by a 1472 papal bull to make an offering on the occasion of the Conception.Footnote 64 Sixtus's initiatives fashioned the Conception feast into a city-wide celebration that was attended by members of the curia and local governmental officials and also attracted a wide array of citizens and pilgrims who hoped to witness the papal ceremonies and benefit from the associated indulgences.Footnote 65

From its very beginning, the Conception Chapel was intended to act as the stage for the pope's observance of the Conception feast. Though scholars often refer to this space as the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception,Footnote 66 Sixtus carefully avoided the term immaculate in his bull.Footnote 67 Moreover, an inscription inside the chapel announced that it was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, Francis, and Anthony, without mention of the Conception.Footnote 68 The chapel's dedication aligns with Sixtus's hesitancy to directly express his Immaculist stance in any official capacity. Nogarolo's office, however, explicitly proclaimed that the faithful were observing the Madonna's Immaculate Conception inside the chapel. Phrases announcing the celebration of the Immaculate Conception also punctuated various parts of the office, including the prayer for both vespers and mass; the first versicle of vespers; the matins invitatory; and a reading for lauds.Footnote 69 The repetitive usage of the controversial phrase inside the chapel walls made it apparent that the space served as the locus for promoting an Immaculist understanding of the feast.

During the festal celebrations, Perugino's Marian image in the apse came to embody the Immaculate Madonna. An understanding of the fresco's original appearance can be derived primarily from a sketch and a written description contained in a manuscript documenting Old St. Peter's Basilica that Vatican archivist Giacomo Grimaldi (d. 1623) and a team of draftsmen completed between 1619 and 1620 (fig. 4).Footnote 70 Another image of the Conception Chapel is found in the frescoes decorating the Santa Maria de Partorienti chapel in the Vatican Grottoes (fig. 5). The cycle includes reproductions of chapels and altars once found in the basilica and was painted between 1616 and 1618 by Giovanni Battista Ricci (1537–1627), who lived in Rome from 1585 until his death in 1627.Footnote 71 Ricci undoubtedly viewed Sixtus's Conception Chapel before it was razed in 1609; the presence of Michelangelo's Pietà on the chapel's altar made it an important site of devotional and artistic pilgrimage and would have drawn the attention of a professional artist such as Ricci, who included the sculpture in his image of the chapel.Footnote 72 Both Grimaldi's and Ricci's images formed part of Paul V's initiative that authorized the old basilica's documentation prior to its destruction.Footnote 73

A comparison of the two reproductions reveals the same overall compositional arrangement but discrepancies in iconographic details.Footnote 74 Both show Sixtus kneeling below the Madonna and Child in the company of four saints. Saints Peter and Francis stood on the left-hand side of the composition, and Saints Paul and Anthony of Padua on the far right. Both Anthony and Francis commonly appeared in later images promoting the Immacolata, largely due to their close ties to Sixtus, who attributed his rise to the papacy to the two saints.Footnote 75

Perugino's fresco followed a visual trend found in curial tomb monuments in which Peter presented a kneeling pope to the Madonna and Child, shown either enthroned or in glory. Such presentation images symbolized the deceased's ultimate attainment of eternal life and appropriately appeared in a panel or lunette located in the tomb's uppermost registers.Footnote 76 As seen in Ricci's image, Perugino used gold leaf to identify the heavenly sphere, an unusual choice for this period.Footnote 77 Nevertheless, Rome was known for its centuries-old veneration of miraculous icons, and local painters in the second half of the fifteenth century executed Marian paintings for members of the curia that adopted formal characteristics found in the city's efficacious images—most notably, the employment of gold ground.Footnote 78 This Roman trend gained particular momentum during Sixtus's promotion of the Virgin's cult.Footnote 79 The formal arrangement of figures and the application of gold leaf thus placed Perugino's apse painting in dialogue with a repertoire of images associated with Sistine Marianism in Rome.

MARIA IN SOLE IN FRANCISCAN MARIOLOGY

The Franciscan context of Perugino's fresco, and specifically the belief in Maria in sole, also helps explain the extensive use of gold. The Conception Chapel's decorative program also included Saints Bernardino of Siena (1380–1444) and Bonaventure (ca. 1217–74), both of whom appeared directly outside the chapel's entrance. These saints were commissioned by either Sixtus or his nephew Pope Julius II (r. 1503–13) and were executed by an unknown artist sometime after 1482, the year Sixtus canonized Bonaventure.Footnote 80 The inclusion of Bernardino and Bonaventure, as well as Francis (d. 1226) and Anthony (1195–1231), spoke to the pope's identity as a Friar Minor and placed the painted Madonna in a specifically Franciscan framework. Each of the saints who appeared in the Conception Chapel's decorative schema were also crucial in developing a Franciscan Mariology that influenced Immaculist thinking. Bernardino was a supporter of the Immaculate Conception and, while Anthony never outrightly promoted the concept, his texts suggest that he subscribed to Scotist theology.Footnote 81 Although Bonaventure denied Mary's freedom from original sin, other salient aspects of his Mariology resonated in successive generations of Immaculist Franciscans and had a particular impact on Sixtus.Footnote 82

Anthony, Bonaventure, and Bernardino were united in their conception of the Madonna as a radiant figure clothed in the sun. Anthony's first sermon on the Annunciation commences with Ecclesiasticus 50:7–8 and compares Mary to the shining sun and a light-emitting rainbow.Footnote 83 For Bernardino, “the symbolic identification of the sun with Mary is the summit of [his] Mariology,” and he relied heavily on the image of the Woman of the Apocalypse in his Marian sermons.Footnote 84 Bonaventure also regularly introduced this apocalyptic image at salient moments in his orations and employed it in five of his six Assumption sermons, in which Mary's luminescence represented a central theme.Footnote 85

The image of Mary enwrapped in the sun symbolized her resplendent likeness to Christ and her singular, exalted state above all creation. Bonaventure's second sermon on the Assumption reflects on Wisdom 7:29, and explains that Mary's exceptional beauty, nobility, and wisdom make her “more beautiful than the sun, and above all the order of the stars: being compared with the light, she is found before it.”Footnote 86 He locates Mary close to the apex of the hierarchy: she stands above the physical sun and nearest the “Sun of eternal light, the source and origin of all beauty.”Footnote 87 The Madonna exists within Christ's divine light and her unmatched motherly love “so transformed [her] into his likeness that she can be literally said to be ‘the brightness of eternal light, and the unspotted mirror of God's majesty, and the image of his goodness’” (Wisdom 7:26).Footnote 88 The depth of Mary's love for Christ drew her and her son together in perfect conformity and shaped her into a mirror “sine macula” that reflected his divine light.Footnote 89

Bonaventure's sermon compares Mary to Wisdom, a typology also commonly evoked by defenders of the Immaculate Conception. Nogarolo's office and other Immaculist texts frequently cite Proverbs 8:22, in which Wisdom speaks in the first person: “The Lord possessed me in the beginning of his ways, before he made anything from the beginning.”Footnote 90 Immaculists adduced this verse to prove Mary's conception in God's mind from the very beginning.Footnote 91 Della Rovere's Paduan sermon reinforces this notion by describing Mary as the embodiment of two primordial sources of illumination, the light of Wisdom and the light of creation: “‘the most High has sanctified his own tabernacle,’ which was filled with light. And this light, when God saw that it was good, he separated it from the darkness so as to preserve the mother from original darkness. And this light of sanctification of the blessed Virgin he called day . . . because she is precisely the true ‘brightness of eternal light, and the unspotted mirror,’ as is said in the seventh chapter of Wisdom.”Footnote 92 Mary's predestined role as Christ's vessel necessitated her fully pure conception before the existence of sin. In another part of the homily, della Rovere again refers to God's generation of light as the moment of Mary's conception, and he describes her as the “lux” specially conceived to carry “the divine sun on earth by whom humankind was saved.”Footnote 93

Mary's luminosity symbolized her resemblance to Christ and her elevated position in the heavenly hierarchy. Moreover, her embodiment of primordial light provided Immaculists with a visualization of her conception prior to all creation. As a result, light imagery permeated the larger body of literature and visual arts surrounding the Immaculate Conception, particularly that directly associated with Sixtus. In 1472, Sixtus composed a prayer and inserted it in the bull Stella Maris, which he issued for the Roman miraculous image of Santa Maria della Consolazione.Footnote 94 The prayer proclaims that the “Immaculata Virgo” is like a “bright star” and is “clothed in the sun,” while the bull also states that the Consolazione image “glitters [coruscat] with many . . . miracles.”Footnote 95 Another prayer attributed to the pope and entitled Ave Sanctissima Maria was popularly employed in Immaculist circles. All known surviving copies of the prayer date to during and after Sixtus's reign, and many include a rubric that identifies the pope as the author.Footnote 96 The prayer's indulgence states that it was meant to be recited while meditating on an image of the Virgin “in sole,” and a large number of reproductions of the prayer include representations of Mary, either alone or holding the Christ Child, and framed by rays of the sun (fig. 7).Footnote 97 If Sixtus did indeed compose the prayer, he evidently favored this particular iconographic motif as an expression of Mary's immaculacy.Footnote 98

Figure 7. Maria in sole with the Ave sanctissima Maria prayer, late fifteenth century. Woodcut, 4 x 3 in. The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS Bodl. 113, fol. 13v.

The roots of the Maria in sole can be traced to diverse sources, including the Woman of the Apocalypse and a legend promoted by the Observant Franciscans at the Church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli on Rome's Capitoline Hill.Footnote 99 The church allegedly marked the site where the Tiburtine Sibyl prophesied Christ's coming to the Emperor Augustus, who saw a vision of the Madonna and Child inside a sun surrounded by “a golden circle.”Footnote 100 The Marian church's surviving confessio depicts Augustus kneeling with clasped hands before the vision (fig. 8), and other depictions of the legend bear a similar composition.Footnote 101 Perugino's Conception Chapel fresco recalls these images, with Sixtus assuming the emperor's place. The Aracoeli legend enjoyed popularity throughout the Latin Church, and the Conception Chapel's compositional parallels with the emperor's visionary experience may have served to associate Perugino's painting with the local Franciscan legend and subsequently with the Maria in sole.

Figure 8. Matteo di Pietro da Gualdo, Meeting at the Golden Gate and the Immaculate Virgin, end of the fifteenth century. Tempera on panel, 6.7 x 10 in. Nocera Umbra, Museo Civico. Photo courtesy of Musei Nocera Umbra and Comune di Nocera Umbra.

THE CONCEPTION LITURGY AND PERUGINO'S APSE FRESCO

The Virgin surrounded by light was evidently a recurrent theme in Franciscan and Sistine Mariology. Perugino's Madonna, placed in glory against a golden backdrop at the apex of the apse, can be read as a visualization of this vein of Marian theology that became especially apparent when the fresco was perceived during the feast of the Conception. Eric Palazzo identifies the medieval liturgy as what he calls the ritual “locus” in which the congregants’ sensory perceptions momentarily permitted access to divine presence and truth.Footnote 102 In the liturgy, a combination of sensory stimuli “coexist in close proximity during the ritual sequences of any ceremony.”Footnote 103 This dynamic experience leads to the “‘activation’ of material reality,” which “enables the in presentia, that is to say . . . the manifestation of the invisible contained in the visible through the activation of the sensory dimension.”Footnote 104 The following section draws on Palazzo's notion of liturgical activation to analyze the ritual locus of the Conception feast in the Conception Chapel.

Throughout his papacy, Sixtus actively promoted liturgical texts, as exemplified by his involvement in the printing of two editions of the Roman missal.Footnote 105 The liturgy also represented an important component in Sixtus's efforts to inspire widespread devotion to the Virgin. In 1475, for instance, he issued a bull that reconfirmed the Virgin's Visitation, a feast of particular importance to the Franciscan Order;Footnote 106 for the occasion, Sixtus commissioned a new office that he then performed at Santa Maria del Popolo, a venerable Roman church where he regularly celebrated many of the major Marian feast days with papal masses.Footnote 107 Given the central role that festal liturgies played in Sixtus's Marian campaign, Perugino's image in the Conception Chapel should be considered to speak to, augment, and interact with the antiphons and chants that the pope commissioned for the most important feast celebrated in that space: the Madonna's Conception.

The pope's Conception celebrations included the regular observance of vespers and morning mass as well as the performance of matins on at least one occasion.Footnote 108 During matins, Nogarolo compared the Virgin to gold-encrusted objects that prefigured her role in the Incarnation. One antiphon sang of the gilded seat of Solomon's litter, and another described the Ark of the Covenant enveloped in “the purest gold.”Footnote 109 Christian exegesis attributed a range of significations to gold, all of which ultimately pointed to the singularity and supremacy of the divine.Footnote 110 In the context of the Immaculate Conception feast, the gilding covering the Ark and Solomon's litter symbolized the Madonna's exceptional virginal purity; it thus supported a central Immaculist tenet that held that Mary's body required exemption from original sin in order to serve as the fitting receptacle for Christ.Footnote 111 The words in the liturgy found resonance in Perugino's fresco of the Madonna and Child, which clearly visualized an image of the Incarnation enveloped in golden splendor.

Imagery more explicitly praising Mary's radiant form permeated other parts of Nogarolo's office. A reading in matins intoned a verse also found in the Assumption liturgy: “Who is she that cometh forth as the morning rising, fair as the moon, bright as the sun, terrible as an army set in array?”Footnote 112 Another reading described Mary as “Sun, which does not know the sunset. Perfect moon, morning,” as well as the “woman clothed in the sun, crowned with twelve stars.”Footnote 113 The first versicle of vespers declared, “The Immaculate Conception of the Holy Virgin Mary is today. Alleluia. R[esponse] Whose celebrated innocence illuminates all devoted souls.”Footnote 114 This verse proclaimed the feast day's name within the chapel walls for the first time, and introduced the Immacolata as a figure emitting divine light. The response expressed the participants’ yearning to be cast in her shining light, a desire realized in Perugino's fresco, in which her most faithful devotee, Sixtus, was enwrapped in her celestial glow. Immediately following this versicle, the Magnificat was sung and Sixtus approached the altar to envelop it in incense.Footnote 115 Incense indicated an encounter or communication with the divine because its smell evoked the perfumes of Paradise and the censing of the altar represented uplifted prayers.Footnote 116 In the Conception Chapel, Sixtus's connection with the Immaculate Madonna was sensorially expressed via the sight and smell of the incense wafting from his hands to the Madonna rendered visible in heaven above.

The words resounding inside the chapel vividly described Mary's luminescence and found physical expression in the shimmering displays of artificial light that enlivened Perugino's fresco during the Conception celebrations. Natural light did not directly illuminate the painting since the apse did not possess any windows; instead, the chapel was illuminated by two large windows located on the side walls just outside the apse.Footnote 117 Moreover, a large portion of the feast-day rituals held within the chapel took place during times of day when little or no natural light necessitated the use of artificial illumination. Both vespers and matins revolved around the sun's motions, with vespers observing its setting and matins occurring in its absence. As the sun withdrew during vespers, the first stars appeared. William Durand (d. 1296), whose commentary on the mass and divine office continued to influence liturgy in successive centuries, identified vespers as an office closely associated with the Madonna “because she is the star of the sea [stella maris], which, in the evening time of this world, begins to shine on us, just as the evening star [vespera stella] from which the Office is called ‘Vespers,’ begins to shine at the beginning of night.”Footnote 118 The evening stars’ arrival were echoed in the lighting of the lamps on the altar, an important rite that unfolded during the office.Footnote 119 In the Conception Chapel, the introduction of the flames would have ignited the fresco's gilded surface so that the Madonna's light shimmered like the heavenly firmament.

Claudia Bolgia's study of lighting effects on medieval Roman mosaics exhorts scholars to consider that the “medieval eye” was accustomed primarily to sunlight and to softer artificial lighting and darker environments than the modern-day eye; as a result, the reverberation of moving light over large swathes of gilded surfaces offered a more dazzling experience to the medieval viewer.Footnote 120 This is witnessed in medieval ekphrases of church interiors in which gilded ornaments commonly inspired “meraviglia” in their beholders.Footnote 121 When liturgical lighting enlivens a solid gold backdrop, a painting is dramatically transformed. The shimmering play of light dominates the scene, and the golden background becomes an entity unto itself that was believed to manifest divine light on earth.Footnote 122 In the context of the Conception Chapel, the shimmering backdrop embodied the Madonna's immaculate light.

On the Conception feast, the visual display of shimmering light converged with the sound of heavenly voices to express Mary's jubilant entrance into the world. The introit for the mass sings out, “Come out you daughters of Zion and see your queen, whom the morning stars praise, of whose beauty the sun and moon admire, and all the sons of God sing out joyfully.”Footnote 123 The solemnity commences with radiant heavenly bodies welcoming Mary into their midst, and the gradual similarly describes Mary's joyful, shimmering appearance: “Our beloved is immaculate, resplendent as the rising dawn. Alleluia. Alleluia. / Come our queen, come lady in the garden of perfume over every aroma. Alleluia.”Footnote 124 The Alleluias, as expressions of angelic joy, frame the verse that beckons Mary forth.Footnote 125 Both the introit and the gradual recall the song that rang throughout heaven in anticipation of the Madonna's arrival on earth. In his Paduan sermon, della Rovere cites Saint Brigit's Exhortations, which tells of the long period that the angels spent praising Mary as they awaited her birth.Footnote 126 His homily then turns to compare Mary's conception with God's creation of light (cited above).Footnote 127 The Conception feast, as it unfolded in the chapel, produced sensory conditions recreating the divine light and angelic song that accompanied the beginning of Mary's existence.

During Sixtus's papacy, music held an important role in establishing “maiestas pontificalis,” and he took measures to augment the papal choir and its privileges.Footnote 128 In 1480, he installed in the Conception Chapel a group of ten singers, who performed from the gallery located above the chapel's entrance.Footnote 129 The significance of music within the Conception Chapel is underscored by the tomb that Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (1443–1513) commissioned for his uncle. The freestanding monument sculpted by Antonio Pollaiuolo (1431/32–98) depicts Sixtus's recumbent form surrounded by allegories of the arts. The figure of Music appears amid various instruments and plays an organ adorned with the della Rovere and papal arms. The organ's prominence speaks to the pope's promotion of music in the papal court, which included his installation of an organ inside the Conception Chapel in 1479.Footnote 130

Polyphonic music was also regularly sung in the papal ceremonies during Sixtus's reign.Footnote 131 Surviving incunabula from the early sixteenth century reproduce polyphonic songs for the Conception feast,Footnote 132 and it is possible that polyphonic music may have been performed at an even earlier date, specifically during Sixtus's festal celebrations. The Conception Chapel's smaller, contained design (compared to the basilica's nave) likely offered the ideal acoustical conditions for such performances, since less voluminous spaces tend to allow for enhanced vocal clarity. The music generated by the singers and the organist in the enclosed space likely engulfed the congregation and provided them with an intimate acoustic experience ideally meant to transport them to devotional heights.Footnote 133

In a bull, Sixtus acknowledged the papal choir's ability to augment the congregation's spiritual experience during the liturgy, stating that the choir's performance “incited [the faithful] to devotion.”Footnote 134 According to late medieval theories of the senses, the perception of a musical composition by the corporeal senses allowed the listeners “to engage their higher spiritual sense and thereby achieve a more direct and truthful understanding of the thing represented.”Footnote 135 Sacred song imitated the singing produced by the angels in heaven, and it was believed that the earthly singers summoned the celestial chorus.Footnote 136 While all sacred music had the capacity to transport one's soul to the divine realm, the introit for the Conception mass more fully merged the earthly with the heavenly: as a song about the act of singing, the antiphon allowed the choristers to embody the celestial figures that sang Mary's praise. In this instance, therefore, the introit's ritual and symbolic purposes overlapped: on a figurative level, it mirrored the joyful music celebrating the Virgin's arrival, while on a literal one, it announced the pope's entrance procession. Enveloped in the song of heavenly voices, the pope's arrival became synonymous with the Madonna's entrance into the world and into the liturgical space.

The liturgy's sensory and symbolic atmosphere was reinforced by the apse painting, in which Mary appeared amid golden light and angelic song. The Madonna and Child were surrounded by cherubim, and the presentation scene in the Conception Chapel differed from those found on other papal tombs in its inclusion of two hovering angels playing the lute and the lyre, respectively.Footnote 137 Angels also figured prominently in images of the Assumption. In Perugino's Sistine altarpiece, a multitude of heavenly hosts were compacted within the upper half of the composition: Perugino enclosed the Madonna in two rings of cherubim, and two full-length angels grasped the innermost ring of the mandorla while two others lowered a crown onto Mary's head. The central angelic figures were themselves framed by two registers of celestial musicians. According to texts such as the Golden Legend (quoting Saint Jerome), Mary's entrance into heaven was welcomed by “‘dazzling light’” and the “‘lauds and spiritual canticles’” of the angels.Footnote 138 An aura of divine light and angelic song framed Mary's existence, and the sensory conditions that enveloped her conception and Assumption further emphasized the association between the two feast days (discussed below).

The music, incense, and lighting conditions specific to the Conception feast together offered participants a highly stimulating and affective sensory environment that heightened the liturgy's persuasive and rhetorical capacity meant to inculcate spectators in Immaculist theological tenets. The multisensory spectacle intersected with the image to make present the Virgin's shining, immaculate nature. It also recreated the heavenly realm from whence the Madonna originated and to which she later returned in her Assumption.

TWO INTERTWINED CHAPELS AND FEASTS

The Conception celebrations in the Conception Chapel were attended by members of the curia, many of whom also gathered for the papal ceremonies that took place before Perugino's altarpiece in the Sistine Chapel.Footnote 139 The construction projects for the two chapels located in the Vatican complex occurred concurrently, and documents recently brought to light by Tobias Daniels prove that both were overseen by architect Giovannino de’ Dolci (d. ca. 1485).Footnote 140 Sixtus also commissioned the same painter, Perugino, to fresco the altar walls of both sacred sites. The two chapels shared evident similarities in their patronage and construction, and such correlations, together with the visual linkage forged between the two frescoes, suggest that the Marian images be perceived as a pair in dialogue with one another.

The feasts for the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption, both of which were important to the Franciscan Order, were also closely intertwined.Footnote 141 The Conception offices composed by both Nogarolo and de’ Busti adopted many of the iconic verses traditionally employed in the Assumption celebrations, and the close association between the two Marian feasts led to the occasional conflation of the Assumption and the Immaculate Conception at one altar or chapel.Footnote 142 Sixtus himself conceptually connected Mary's Conception to her Assumption, as expressed in his Paduan sermon: “[Mary] is all beautiful and without stain . . . so much that, in her conception and death, in her assumption, she was raised before all others and distinguished from all, and among all dignified of every source of grace.”Footnote 143 According to Sixtus's understanding of the Immaculate Virgin, the two episodes served as bookends for her life and together testified to her singular, exalted nature. Sixtus's Mariology finds parallels in other contemporary Immaculist texts, such as the Vita Christi of Franciscan abbess Isabel of Villena (d. 1490), who commenced and ended her book with the two Marian episodes, thus framing Christ's life with Mary's Conception and Assumption and underscoring the relationship between both feasts.Footnote 144 For Immaculists, the Madonna's Assumption provided crucial proof of her preservation from original sin because it followed that a fully pure body that had escaped the ravages of death must also possess an equally pure soul.Footnote 145 The Madonna's assumed state, together with her role as the ultimate intercessor to Christ, led Sixtus to issue a bull promoting the Conception feast. Cum Praecelsa commences with an image of the radiant Madonna, thus echoing a recurrent theme found throughout the Conception liturgy. According to the bull, Sixtus chose to confer indulgences on her Conception feast because of “the exalted insignia of the merits with which the queen of the heavens, the glorious virgin mother of God, advanced to the ethereal dwellings, shining amid the constellations as the morning star.”Footnote 146 The decree's opening lines refer specifically to Mary's ascent to heaven, where she now glows with starry brilliance.

Cum Praecelsa, together with the literature and artwork surveyed thus far, demonstrates that Sixtus favored a particular motif when visualizing the Immacolata; her body, radiant in the uppermost hierarchy of heaven, not only attested to her singularity and unmatched purity but also visually associated the Immaculate Virgin with her Assumption. The intersections between the Conception and the Assumption feasts, together with the similarities between Perugino's two Marian frescoes, forged a connection between the Sistine altarpiece and an image directly associated with the Conception. Such a connection became ever more apparent during the Sistine Chapel's liturgy, when the mandorla surrounding the Assumed Madonna shone in a such a way that it evoked the Madonna clothed in the sun.

PERUGINO'S SISTINE ASSUMPTION

The original appearance of the Sistine Assumption is conserved in drawing by a follower of Pinturicchio (fig. 3). Scholarly consensus accepts the drawing as a faithful copy for multiple reasons. First, it contains elements ascribable to Perugino's style, and the scene's compositional arrangement corresponds to a formula that the artist famously reused in at least eight of his later works, including several paintings of the Assumption.Footnote 147 Moreover, Sixtus's kneeling portrait below a scene of the Assumption aligns with the description that Giorgio Vasari (1511–74) provided of the Sistine altarpiece.Footnote 148 Finally, Sixtus's presence in the drawing and the work's elaborate, multifigure scene are fitting for a painting that once adorned the papal chapel.Footnote 149

Perugino's frescoes titled the Finding of Moses and the Nativity of Christ (both destroyed) were once located directly above the Assumption on the same level as the other narrative scenes (fig. 2).Footnote 150 Covered in bitumen and impenetrable by water, the basket encasing the infant Moses was associated with Mary's virginity;Footnote 151 this scene appeared next to an episode portraying the Christ Child and Mary, his sacred vessel. These two scenes, together with the Assumption, “indicate that Maria Assunta was also Maria Ecclesia, because Mary . . . is the sacred vessel by which the Son of God entered the world to unite Gentiles and Jews.”Footnote 152 In Immaculist polemic, Mary's role in the Incarnation, her Conception, and her Assumption were all tightly intertwined. In his Paduan homily, Perugino's patron declares that, because Mary gave birth to Christ, she merited celestial elevation above the angels.Footnote 153 This concept also found expression in the Assumption mass: the first reading draws on Ecclesiasticus 24 and proclaims, “he that made me, rested in my tabernacle,” and continues with a series of typological imagery praising the Madonna's exalted state.Footnote 154 The frescoes on the Sistine altar wall fittingly identified the heavenly rewards Mary received, thanks to her role as Christ's uncorrupt vessel.

The Sistine Assumption, while portraying her heavenly arrival, did not depict the exact moment in which the Virgin's body rose from her sarcophagus. Rather, it was more devotional in nature and suppressed certain narrative details so that an aura of timelessness pervaded the scene.Footnote 155 Perugino chose to omit the sarcophagus and innovatively replaced it with Saint Thomas, who knelt at the center of the lower register and held the Virgin's belt.Footnote 156 According to apocryphal sources, Mary appeared to Thomas after her ascension and delivered him her girdle as proof of her Assumption.Footnote 157 Visual renditions of this episode typically include narrative elements, depicting, for instance, Thomas catching the belt as it stretches earthward. In the Sistine fresco, on the other hand, the once doubting apostle did not reach upward in an active pose but instead appeared in a stationary kneeling position. Draped over his clasped hands, the girdle functioned more as Thomas’s identifying attribute than as the object of a narrative scene.

The absence of certain narrative details relating to her Assumption largely unmoored the Virgin from her earthly existence. She stood above humankind, for she alone had escaped the stain of sin and the bodily decay that accompanies it. At the same time, her feet were firmly planted on a small bank of clouds, and her serene, motionless figure lacked dynamism. The reflective attitudes of the figures in the lower register presented models of comportment for the viewers, who were invited to contemplate the mystery of the Assumption and its deeper theological meaning. Perugino's composition, with its meditative atmosphere, hovered somewhere between an image of a narrative scene and a representation of a theological concept, and finds visual parallels in images of the Immaculate Conception in which the Madonna stands motionless inside a mandorla suspended in the sky (fig. 9).Footnote 158 The Madonna's Assumption and Immaculate Conception were tightly intertwined feasts and theological concepts, and their similarities led artists tasked with expressing the Madonna's immaculacy to draw on iconography representing her assumed form.Footnote 159

Figure 9. Pope Sixtus IV Venerating the Maria in sole with the Ave sanctissima Maria prayer, ca. 1500. Illumination on parchment, 6.5 x 9 in. London, British Library. © British Library Board, Add. MS35313, fol. 237r.

Perugino's altarpiece in the Sistine Chapel evoked, in particular, the iconographic motif of Maria in sole, the devotional image associated with the Ave Sanctissima Maria prayer attributed to Sixtus. In a manuscript now held in the British Library, the prayer and its indulgence appear alongside an illumination of Sixtus kneeling before a framed panel painting depicting a small figure of the Madonna. Below are several lines of text that presumably convey the words of the prayer (fig. 10). Sixtus fixes his eyes on the Virgin, who appears standing against a stark, golden background. The simple devotional painting in the illumination represents the most basic iteration of the Maria in sole iconographic type and recalls Perugino's Sistine Madonna, who stood upright against a blazing backdrop.

Figure 10. Lateran Icon of Christ, encaustic on wood (sixth to seventh century) and gilded silver revetment with gems and enamel work (early thirteenth century), 2 x 4.7 ft. Rome, Lateran, Sancta Sanctorum. Artwork in the public domain. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Sailko, CC BY 3.0.

Bursts of gold leaf against yellow pigment surround other apparitions of the divine in the Sistine Chapel's narrative wall frescoes, such as Perugino's Baptism of Christ. I argue that the Assumed Virgin, as the central liturgical image, was enveloped in a golden mandorla because the constant presence of candles on the altar during mass made the inclusion of gilding desirable from a liturgical standpoint. Moreover, two reproductions of the altarpiece suggest that the Madonna's mandorla may have boasted larger amounts of gold leaf than the divine visions depicted in the other narrative frescoes. First, in the drawing after the painting, the draftsman used a white heightening to fill in the mandorla's central area.Footnote 160 The heightening indicates the presence of gilding in the fresco since it was also used to render the figures’ haloes, which are elements highlighted in gold in the other fifteenth-century wall paintings. Another copy of the fresco is found in a late fifteenth-century miniature titled Celebration of a Papal Mass in the Sistine Chapel (fig. 3), which likely originated in a missal owned by Sixtus's successor, Innocent VIII.Footnote 161 Perugino's altarpiece, reduced to its most fundamental iconography, appears at the center of the illumination, where the Madonna floats in an intensely shimmering sunburst.

John Shearman observes that the high concentration of gilding in the narrative scenes and in the other painted elements of the chapel contributed to the chapel's primary function of expressing papal majesty. Moreover, the decorative cycle was designed for ceremonies in which artificial, rather than natural, lighting dominated the space.Footnote 162 The building's narrow windows are concentrated in the clerestory, so that the lower story received less sunlight, particularly during the early morning and late afternoon hours, when many of the chapel's rites were held.Footnote 163 According to Pope Julius II's master of ceremonies Paris de’ Grassis (ca. 1470–1528), forty solemnities were performed in the Sistine throughout the year: ten vespers, five matins, and twenty-five masses, including a nocturnal mass at Christmastime.Footnote 164 Candlelight also held a central symbolic position in several of the feast days celebrated in the chapel, such as tenebrae, which took place at matins during Holy Week.Footnote 165 In the following section, I will turn to the Assumption feast of 1483, a day when the altarpiece decidedly commanded the congregation's attention. It was a feast when artificial lighting played an emblematic role and when the altarpiece's associations with the Madonna clothed in the sun received particular emphasis. This will allow me to integrate the discussion thus far with the larger Marian devotional culture in the city, as filtered through Sixtus's theological commitments.

THE 1483 FEAST OF THE ASSUMPTION

The Sistine Chapel's dedication to the Assumption, and its corresponding altarpiece, served to associate the pope's chapel with the city's most venerable religious festival, the origins of which can be traced back to the ninth century. In Rome, the festivities honoring Mary's Assumption commenced on the evening of August 14 with a citywide procession that culminated at dawn at the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore.Footnote 166 In 1483, the festal celebrations also included a mass and vespers in the Sistine Chapel on August 15, the day marking the chapel's public inauguration following its renovation. Viewers’ reception of Perugino's newly unveiled altarpiece was subsequently influenced by their recent participation in the vigil procession, in which Mary's association with divine light and the dawning sun represented a driving theme.

The central protagonist of Rome's Assumption procession was an icon of Christ (fig. 12). It was believed that Saint Luke began painting this image, which was completed by an angel. The panel stood as a symbol of pontifical power and was enshrined year-round in the pope's private chapel, the Sancta Sanctorum in the Lateran Basilica.Footnote 167 The panel served as a visual token of Christ's presence, for it “fulfilled his promise to be always with his followers in the place where his earthly representative resides.”Footnote 168 Every year on August 14, the image emerged from the Lateran to wind through the Roman Forum to Santa Maria Maggiore (fig. 11), where it met the Salus Populi Romani, a venerated icon of the Madonna and Child. This meeting between the two paintings reenacted the reunion between mother and son at her Assumption. Upon entering the church, the icon of Christ was placed on the altar, where it remained overnight until morning mass.Footnote 169 In the early iteration of the procession, the pope accompanied the Lateran image during the entire route to express an elision between himself and Christ. His arrival at Santa Maria Maggiore symbolized his union with the church because the Marian icon represented the “Ecclesia Romana” and the Roman people's intercessor.Footnote 170 By the twelfth century, however, the pope no longer commanded a leading position in the parade but rather awaited the Lateran icon's arrival at Santa Maria Maggiore. In the fifteenth century, the procession was the city's only major religious festival not organized by the papacy; instead, the Santissimo Salvatore confraternity led the celebrations, governmental officials and guilds commanded highly visible positions in the processional route, and the Roman people participated in the ritual.Footnote 171 The procession provided an “illusion of civic dignity,” and “the Church was shown to be at the service of the [local Roman] community rather than dominating it.”Footnote 172 The pontiff's passive role in the celebrations and the communal nature of the ceremony may have contributed to Renaissance popes’ gradual withdrawal from, and eventual abolition of, the procession.Footnote 173

Figure 11. Salus Populi Romani, ca. late sixth to early seventh century. Tempera on panel, 3.25 x 5 feet. Rome, Basilica of Maria Maggiore, Cappella Paolina. Artwork in the public domain. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Fallaner, CC BY-SA 4.0.

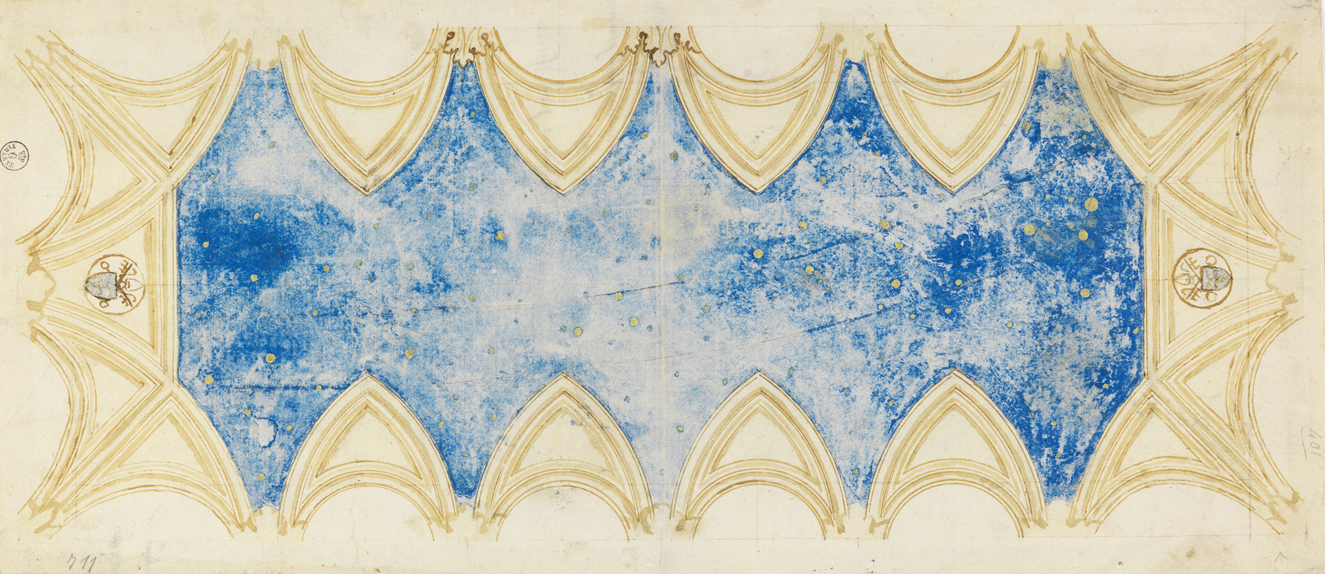

Figure 12. Piermatteo d'Amelia (attributed), design for the Sistine ceiling, 15.4 x 6.8 in. Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, inv. 711 A. © Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi.

At the end of the fifteenth century, the Assumption feast represented a highly significant local feast that was largely civic in nature. The pope, if present, took a secondary role in the festivities. The Assumption feast of 1483, therefore, represented a temporary rupture in tradition when Sixtus organized a separate and memorable ceremony of his own to commemorate Mary's heavenly ascent. Scholars have remarked on the unusually long lag between the completion of the chapel's decoration in April or May of 1482 and its public opening in August the following year. Although the chapel was completed in time for the 1482 Assumption feast, the arrival of Roberto Malatesta's troops to Rome on that day, and the Battle of Campo Morto only days later, presumably prevented the pope from celebrating the feast in the Sistine that year.Footnote 174 Rather than scheduling the chapel's opening for just after the battle, Sixtus chose to hold it an entire year later.Footnote 175 I suggest that Sixtus's decision to wait and celebrate the public opening on the next available Assumption feast was a strategic one. The feast boasted a salient position in the local liturgy, and Rome's intense dedication to the Assumption presented Sixtus with the opportunity to advertise his new chapel on a day when Marian devotion was at its height. He expanded the traditionally civic feast to hold a ceremony in a space that communicated messages of papal primacy. The frescoes placed the pope within a highly distinguished priestly and papal lineage, presenting him as the “new Moses,” the Vicar of Christ, and Saint Peter's rightful successor.Footnote 176 More importantly, for the purposes of this article, Sixtus observed the feast by commanding a leading role in the liturgical reenactment of Christ's visit to Mary during her Assumption.

On 15 August 1483, Sixtus opened the Sistine to the general population; he bestowed a papal blessing on the plebi who gathered for mass and vespers and extended indulgences to anyone, even women, who visited that day.Footnote 177 Jacopo Gherardi reports that the promised indulgence drew such multitudes of Romans that they impeded movement in the Sistine, and the crowds did not disperse until long into the night.Footnote 178 Given the Assumption procession's widespread popularity among the locals, the majority of the Romans who gathered in the Sistine that day had presumably attended the celebrations that had recently culminated at Santa Maria Maggiore, and their memories of these festivities were undoubtedly vivid and fresh.

As in the Conception feast, light commanded a central role throughout Rome's feast-day vigil. Lamps were hung from the building facades lining the route, and guildsmen carried approximately forty talami, or large wooden stands holding candles, before the Lateran icon.Footnote 179 The painting was permanently encased in a gilded silver cover and was offered a pallio d'oro (golden cloth) for the Assumption feast.Footnote 180 Layers of gold swathed Christ's image during the rite, and the metal panel's reflective surface shone with intensity in its ritual setting.Footnote 181 The processional route terminated at the altar inside Santa Maria Maggiore, where Christ's gleaming form reunited with the Marian icon, whose stark golden ground reflected the candlelight employed in the liturgy. The nocturnal vigil ended with a mass held at sunrise, which was considered the moment of Mary's heavenly ascent.Footnote 182 The climax of the festal celebrations at the rising of the sun recalled Pseudo-Melito's account of the Assumption, in which the Apostles turned their eyes from the blinding brightness of Mary's uplifted soul because “it excelled all whiteness of snow and of all metal and silver that shines with great brightness of light.”Footnote 183 A sermon delivered by Pope Innocent III (r. 1198–1216) on the occasion of the Roman feast further compared Mary to the dawning sun that chased away the sin-filled night and ushered in the virtuous light of day on earth.Footnote 184

Following the festivities at Santa Maria Maggiore in 1483, Romans ran to the Sistine Chapel, where their experiences of the Assumption vigil celebrations informed their interpretations of the pope's rituals held before Perugino's altarpiece. Master of ceremonies Agostino Patrizi Piccolomini (d. 1495) detailed the ceremonial precepts of the papal court and included a section on the artificial lighting employed in the liturgy.Footnote 185 During his entrance procession, the pope crossed beneath the chapel's chancel screen, a dividing wall crowned with seven candelabra that originally ran from the choir loft to the opposite nave wall.Footnote 186 Sixtus's arrival in the chapel was announced by a total of nine candles. On those days that the pope did not attend mass, only two candles were borne in the procession, so that, from the very start of the liturgy, the pope's absence cast a gloom throughout the space.Footnote 187 The number of candles burning during the liturgy hinged upon the pope himself and depended on whether he or another official served as celebrant. On the infrequent occasions that the pope himself conducted the sacred rites, the intensity of illumination increased dramatically, with the total amount of candles numbering at least forty-three. If the pope was absent during mass, only twenty or twenty-two sources of light were ignited. When the pope was in attendance but not leading mass, then the number of candles increased to between twenty-seven and twenty-nine, thanks to the inclusion of the seven additional lights employed in the papal entrance procession.Footnote 188 When a cardinal led mass in the pope's presence, six of the candelabra mounted above the chancel screen were lit, and six candles above the altar and two on the credence shimmered during the mass. As the ceremony progressed, lights were temporarily ignited to punctuate salient ritual moments: two glowed during the reading of the Latin Gospel, and four burned when the celebrant raised the Host at the moment of consecration.Footnote 189 Perugino's altarpiece became a focal point during the sacred rites, when at least one-third of the total number of candles were concentrated on or near the altar table.Footnote 190 Ritual activated the painted Madonna, and her golden glow only intensified with the pope's presence. In this moment, the iconographic parallels between the Immacolata in the Conception Chapel, the Maria in sole images, and Perugino's Assumed Madonna were reinforced by the candlelight illuminating the fresco during the ritual.

As in the Lateran Christ's processional route to the Marian image, candlelight played a crucial symbolic role in Sixtus's initial approach to the Assumed Virgin. The nine candles that accompanied the pope during his entrance procession were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of a pair of candle bearers, alongside an incense bearer, all of whom appeared near the head of the procession. Every ordinary celebration of the mass included these three participants, whom liturgists interpreted as representations of the prophetic sources that foretold the coming of “the light of the world.”Footnote 191 During a papal mass, the two candles were followed by a group of seven candles that bore a multifaceted meaning reserved for the pontiff.Footnote 192 Between 1195 and 1197, Cardinal Lotario dei Conti di Segni (later Pope Innocent III) wrote the widely influential De Missarum Mysteriis (On the mysteries of the mass), which expounded on the significance of the mass. His section on the procession to the altar states that the seven lights employed for the pope were intended to manifest John's vision in Apocalypse 1:12–13: “in the midst of the seven golden candlesticks, [I saw] one like to the Son of Man, clothed with a garment down to the feet.”Footnote 193 The symbolism that Lotario attached to the seven processional candles was carried on by Durand, and Paris de Grassis's own section on the candelabra in the papal chapel immediately commences with the verses from Apocalypse 1.Footnote 194

In addition to the seven burning flames, a long flowing robe served as the second identifying feature of the Son of Man in John's vision. The pope entered the chapel with a floor-length cope that received much ritual attention prior to and during the procession. During the pope's vesting, the cardinal deacons paid reverence to the pontiff by bestowing kisses upon the hem of his cope. In the entrance procession, the rear of the cope was prominently displayed by a noble or lay orator who carried the train, while a protonotary held the hem of the cope and fanned it out so that it framed the left side of the papal body.Footnote 195 At this point in the liturgy, the sumptuous vestments, lighting effects, and incense merged to prepare the congregation for the coming of the pope, who, in the context of the procession, represented Christ himself.

As the pope closed the distance between himself and the altar, the many processional lights would have temporarily cast their glow on Perugino's painting, so that the pope's physical presence significantly elevated the brilliance radiating around the Virgin. The apocalyptic symbolism embodied by the glow of papal light enhanced the Sistine Madonna's association with the Woman of the Apocalypse, an image that spoke to Mary's identification with the church.Footnote 196 On the Assumption feast, this correspondence between Mary and the church was strengthened by the employment of verses from the Song of Songs, which theologians interpreted as a marriage song celebrating the union between Christ and his church.Footnote 197 The Assumption mass in the Sistine thus rendered visible the connection forged between Sixtus as Christ's vicar and Mary as Ecclesia. The seven candles employed during the pope's procession were further intended to represent the pope walking amid his church. The lights illuminating Christ in John's vision corresponded to the number of churches to which the evangelist conveyed his text.Footnote 198 Similarly, in the papal installation mass, the candles borne in the procession to the altar in St. Peter's Basilica stood for the seven ancient districts of the Roman diocese.Footnote 199 The Sistine festal celebrations thus signified both the pope's and Christ's union with the body of the church, and such symbolism was heightened by the exceptional presence of the Roman people gathered to witness the papal liturgy on 15 August 1483.

According to di Segni and Durand, the processional lights further symbolized the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit that belonged to the rod of Jesse (Isaiah 11:1–3), a typological image traditionally applied to the Immacolata.Footnote 200 In a sermon on the Annunciation, Bonaventure states that Mary possessed the gifts of the Spirit.Footnote 201 Della Rovere's sermon delivered in Padua similarly associates the gifts with the Immaculate Virgin, whom he characterizes as the “eastern gate” that contained Christ: “Shining in this gate is that candlestick all of gold, and its lamp upon the top of it, and the seven lights thereof upon it which are the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit that shine with outstanding brightness [prefulxerunt] in the glorious Virgin.”Footnote 202 In this passage, della Rovere explicitly forges a connection between the seven candles and the gifts of the Spirit, and their glow appears to find its source in both Christ and the Virgin; Christ carried the gifts with him when he dwelled in her womb, and their light pulsated outward from her virginal body. The lighting activated by the papal liturgy in the Sistine suggested a similar affinity between Sixtus and Mary in which the Virgin's splendor both echoed and was enhanced by the illumination surrounding the papal body.

THE ASSUMED MADONNA AS PORTA COELI

The preceding discussion of the rituals performed in the space provides the basis for new and necessarily hypothetical consideration of how the chapel's sensorial atmosphere impacted viewers’ experiences and perceptions during the liturgy. The Sistine altarpiece participated in a ritual dialogue that unfolded between the pope and the Madonna, and such a dialogue became more evident during the 1483 feast of the Assumption.

For the celebrations on August 15, the pope held mass and vespers in the chapel, and the crowds continued to congregate late into the night.Footnote 203 As the natural light dimmed, the candlelight reflecting off the Madonna's mandorla shimmered with increasing intensity. The pope's procession to the assumed Virgin on the altar recalled the Lateran Christ's luminous journey to the Marian icon on the altar of Santa Maria Maggiore. The viewers’ memories of the recent Assumption procession would have influenced their interpretations of the pope's rituals held before the new altarpiece. At Santa Maria Maggiore, the Romans had waited in anticipation for the first glimmer of sunlight, which corresponded to Mary's celestial ascension. Just hours later, the pope's illuminated walk to the Sistine altar again reenacted Christ's reunion with his mother.