The nickname came first, although its exact origins are unknown. The first time it appeared in print it graced the 4 February 1971 cover of Jet magazine and declared Isaac Hayes the “Black Moses of Today's Black Music.” Hayes recalled hearing the phrase initially from a Stax Records employee who claimed that audiences responded to the musician as if he were a “modern-day Moses.” Around the same period, an Apollo Theater announcer introduced Hayes as “Black Moses” before his performance at the famous venue began. Although he originally viewed the name as sacrilegious in part due to his southern evangelical background, Hayes soon considered the name favorably because it heightened racial consciousness among fans during an era when “people were proud to be black.” The moniker elicited such a positive reaction from African Americans that Stax titled his subsequent album Black Moses.Footnote 1 The record, released in November 1971, came at the height of Isaac Hayes's commercial and popular success. Over the previous twenty-six months, Hayes released four albums and became a multimillionaire. Each of his records received tremendous critical acclaim, achieved platinum sales status, and cracked the US Top Ten album list. In fact, the Shaft soundtrack held the number one position on the Billboard magazine album chart and the movie's title track was number two on the “Hot One Hundred” singles list when Black Moses premiered. The two titles were the first non-live or greatest-hits double albums released by a rhythm and blues (R & B) artist and the latter transformed Hayes into the “Black Moses” persona, whom the artist presented consciously as “the epitome of black masculinity.”Footnote 2

Isaac Hayes is a critical figure in music, southern, and African American history whose art connects celebrity, consumers, and scholars in dialogue concerning race, gender, popular culture, and liberation. An examination of Hayes and his “Black Moses” persona, the creative apex of his career, reveal a calculated rejection of prevailing stereotypes concerning African American heterosexual manhood and contributes to a more complete understanding of the long black freedom struggle by challenging norms around what black artists could, and should, do with their music.Footnote 3 Most importantly, Hayes reveals that the contemporary conceptualization of African American masculinity was not monolithic and that “Black Moses” represented an artistic effort to achieve a more complete realization of black male self-identity independent of white definitions or standards. As “Black Moses,” Isaac Hayes embodied an ideal that differed tremendously from the aggressive, hypersexualized, phallocentric image of African American masculinity that dominated popular culture at the time and remains a central figure in collective memory of the 1970s black power era. Hayes personified sensuality, vulnerability, and emotional pain as masculine traits, while presenting himself as the embodiment of a strong, successful, proud, and confident black man. He likewise challenged the dominant concepts of black male propriety that were central to the mainstream civil rights movement's emphasis on respectability politics. Hayes never intended American Americans to use his self-presentation, artistic expressiveness, or personal behavior to counter white beliefs that inherent black inferiority perpetuated racial injustice, which rejected the cultural accommodationism that Booker T. Washington and his adherents promoted. The determination of Isaac Hayes to create music and present himself on his own terms constitutes a vital component of the long black freedom struggle, which contributes to a more nuanced understanding of African American male identity and places him within a longer tradition of artists whose cultural production constituted the foundation of black power between 1965 and 1975.

In the classic study New Day in Babylon, historian William Van Deburg demonstrated that “the Black Power movement was not exclusively cultural, but it was essentially cultural” because such expression “provided a much-needed structural underpinning for the movement's more widely trumpeted political and economic tendencies.” This cultural “seedbed,” Van Deburg maintained, allowed African Americans to access “power – both actual and psychological” – through the liberating self-definition that “was central to the Black Power experience.”Footnote 4 Similarly, historian Joe Street concluded that black artists used cultural expression “to make a political point” and “broaden both the movement and the movement's appeal to ordinary Americans.” The “cultural organizing,” as Street labeled it, often held important intrinsic political meaning that connected performer to audience and formed a crucial component of the emergent black power movement.Footnote 5 A focus on the era's cultural production, scholar Robert J. Patterson proclaimed, provides “multiple way of defining blackness” that “pushes conventional ways of thinking” about culture “outside of the norms that the existing sociopolitical order disciplines us to call upon when we imagine or think about black freedom.” The emphasis on cultural expressions created during the period, Patterson continued, “provides a space to imagine possibilities for black thriving that have yet to be imagined or otherwise realized,” and music is one of the important – and accessible – forms of African American cultural expression.Footnote 6

In 1963 Imiri Bakara released his groundbreaking Blues People, which emphasized the centrality of music in the unique sociocultural and historical African American experience. Historian Brian Ward extended many of Bakara's conclusions in Just My Soul Responding and presented African American music consumption “as a self-conscious assertion of the racial pride which was one of the most important legacies of the movement, and a defining characteristic of the black power era.” Music, Ward argued, brought a “sort of psychological empowerment” for African Americans who never participated in movement demonstrations, protests, or campaigns and “helped to shape and define black consciousness over time.”Footnote 7 During the black power era in particular, according to William Van Deburg, black recording artists “served as conduits for the vital message of racial unity,” “were perceived as remaining ‘unspoiled,’ ‘natural,’ and close to the people,” and “became a true culture hero.”Footnote 8 Due to his commercial success, artistic uniqueness, and international visibility, then, Isaac Hayes occupied a unique cultural space at a crucial time in African American history when Stax released Black Moses in 1971. The prevalent image of normative black manhood that existed during the contemporary political and entertainment realms made the masculine image that “Black Moses” embodied particularly subversive. Scholars of the civil rights movement have noted the important role that gender played in the long freedom struggle, yet few extend their work into deeper explorations of black masculinity during the period beyond integration.

Historian Steve Estes, in I Am A Man! Race, Manhood and the Civil Rights Movement, presented Malcolm X as a “model of militant masculinity” which “guided the course of the civil rights movement after his death” in 1965.Footnote 9 Indeed, Van Deburg posited Malcolm X as “the archetype, reference point, and spiritual adviser in absentia” for those who embraced the “racial pride, strength, and self-definition that came to be called the Black Power movement,” most notably the Black Panther Party. The decline of nonviolent southern-based civil rights campaigns after passage of the Civil and Voting Rights Acts, Estes contended, created opportunities for African Americans to “fashion new definitions of manhood” which the Black Panthers ultimately embodied.Footnote 10 Feminist writer Michele Wallace labeled that dominant ideal, “the cultural embodiment of the hyper-masculine image that the Panthers had initially created for themselves,” as “black macho.”Footnote 11

The “black macho” ideal dominated popular culture when Isaac Hayes reached his creative peak and still permeates historical memory of the era. In Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, Wallace contended that the black power movement understood race within “a metaphorics of phallic power” in which men emphasized a hypersexuality and pursuit of sexual pleasure. For men, black power became a vehicle in which African American men objectified women, emphasized their sexual prowess, and provided a “narcissistic” counterimage to the benevolent patriarchy that Martin Luther King Jr. advocated which “presumed some emotional and material responsibility towards black women and children.” The black macho “mythology,” Wallace later wrote, “was really an extension and reversal of the white stereotypes about black inferiority” and “dictated that black men would define their masculinity (and thus their ‘liberation’) in terms of superficial masculine characteristics.”Footnote 12 Robyn Wiegman validated the “phallocentric perspective” that guided the works of influential black power cultural figures such as Malcolm X, Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, and Amiri Baraka. She also referenced the macho, hypermasculine character that dominated the “blaxploitation” films in the early 1970s to further her thesis.Footnote 13 Consequently, according to historian Daniel Matlin, “Male black power activists have often been depicted as nihilistic, armed poseurs, oblivious to the welfare of their communities but spurred to action by their genitals, which pointed unfailingly at white women.” The “rapist, the macho man, the brute who uses force to get his demands met,” according to the activist scholar bell hooks, is often perceived as the model of heterosexual African American masculinity as the 1960s ended, and no one represented the hypermasculinity and sexism within contemporary black popular culture more in music than James Brown and on screen quite like the movie Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song.Footnote 14

With the 1968 anthem “Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud,” James Brown transformed a word often used to denigrate an entire people into one that conveyed self-worth and racial authenticity. In Remaking Black Power, historian Ashley Farmer explained that the shift in identifying between the terms “Negro” and “black” represented “a deeper, more encompassing effort to transform the black condition by developing interpretations of black manhood and womanhood unbridled by Eurocentric definitions.”Footnote 15 To identify as “black” in 1968, then, was to declare a degree of racial and cultural identity not universally accepted at the time. In addition, according to cultural historian Alice Echols, James Brown's music, live performances, and carefully manicured appearance “configured black masculinities in the sixties as surely as the Black Panthers did in their black berets and leather jackets.”Footnote 16 His status as “Soul Brother Number One” and personal appearance embodied what music journalist Nelson George labeled the “unbridled machismo” of the era.Footnote 17 With hypersexual songs like “Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine,” “I'm a Greedy Man,” “The Payback,” “Cold Sweat,” and “Papa Don't Take No Mess,” it is little wonder that George Clinton attributed his appreciation of Brown to the fact that his music “makes your dick hard.”Footnote 18 Similarly, Melvin Van Peebles reinforced “the enduring representation of black power as a hedonistic outburst propelled by the antisocial impulses of black macho” in the film he wrote, directed, and starred in as the title character, Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song.Footnote 19 Prostitutes reared Sweetback in a brothel, raped him into manhood as a young boy, named him for his sexual proficiency and penis size, and incorporated him into sex shows as an adult. The 1971 movie's titular antihero, labeled at its conclusion a “baad asssss Nigger,” killed police and used gratuitous amounts of sex and violence – including rape – to ultimately escape into Mexico. Black Panther Party cofounder Huey Newton devoted an issue of the organization's newspaper to the film and lauded it “the first truly revolutionary film made and it is presented to us by a Black man.” He was enamored with the implication that Sweetback discovered liberation through violence and sex, and Newton made the film required viewing for Black Panther members.Footnote 20 The model of black masculinity, therefore, that dominated the national imagination as the 1970s began, made the image presented by Isaac Hayes incredibly unique. Yet little in his personal and professional development indicated that he would create a subversive cultural figure like “Black Moses.”

Isaac Hayes was born on 20 August 1942 in Covington, Tennessee. His grandparents, sharecroppers named Willie and Rushia Wade, reared Isaac with his stepsister and relocated the family to Memphis in 1949 to escape their desperate economic circumstances. Debilitating poverty, however, followed Hayes into his teenage years. Only a burgeoning love of music provided him temporary solace from hunger, seasonal field work, and occasional homelessness. As a ninth-grader, Isaac learned to play the saxophone. He later joined a doo-wop group and a gospel quartet and taught himself to play the school's piano. After graduation, his performances at a Memphis nightclub caught the attention of Floyd Newman, a member of the Stax recording group known as the Mar-Keys. Newman used Hayes as a pianist during a recording session at Stax, and he ultimately landed a full-time position at the upstart label. Hayes ultimately became a studio pianist but he attained his greatest success up to that point as part of one of the greatest songwriting duos in popular music history.Footnote 21 In 1966, Hayes and David Porter, a Memphis native and the first salaried songwriter at Stax, began writing songs for the duo Sam and Dave and ultimately produced such classic tunes as “You Don't Know Like I Know,” “Hold On, I'm Comin,” “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby,” and the Grammy-winning “Soul Man.”Footnote 22 The studio was at the height of its commercial success when three events permanently altered the direction of Stax Records and, ultimately, Isaac Hayes's career.

On 10 December 1967, Otis Redding and four members of the Bar-Kays died in a Wisconsin plane crash while on tour. Stax never fully recovered from the calamitous loss of Redding, whom music journalist Jann Wenner deemed “the crown prince of soul.”Footnote 23 Weeks later, label cofounder Jim Stewart learned that his distribution contract with Atlantic Records included a clause that gave the label total ownership of all Stax recordings made between 1960 and 1967. For all intents and purposes, Stax was a recording company that owned nothing in 1968.Footnote 24 Tragedy struck yet again on 4 April, when an assassin killed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as he stood on the balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Stax artists used the Lorraine weekly, as it was one of the only public places in the city where black and white musicians could lodge and gather together freely. The loss of King, Redding, and the entire Stax catalog altered permanently the label's artistic direction, economic objectives, and interracial composition, each of which had a direct effect on the rise of Isaac Hayes as a solo superstar.Footnote 25 Al Bell, an African American deejay whom Stax hired in a promotional and business development capacity in 1965, eventually bought half of the company, became one of its vice presidents, and presided over the label's post-1968 resurrection. Most importantly, Bell developed a sales idea called “Soul Explosion,” which would flood the music market with the simultaneous release of twenty albums in May 1968. The strategy intended to both build an immediate catalog of original Stax material and announce the label's rejuvenation in one bold move, and Bell asked Isaac Hayes to produce the final “Soul Explosion” record.Footnote 26 The decision allowed Hayes to develop his art and image in personal and liberating ways which repudiated the era's “black macho” ideal of African American masculinity.

Stax released Introducing Isaac Hayes, the titular artist's debut record, in February 1968. The decision surprised Hayes, who “was not in control of my mental and spiritual facilities” and unsatisfied with the results after he made the informal recording with two members of the Stax house band after a party at the studio.Footnote 27 Unsurprisingly, the LP sold modestly and Hayes rarely mentioned it in subsequent interviews. He agreed to release another record only if Stax gave him full artistic and creative freedom in all aspects of the production process. The “Soul Explosion” strategy allowed Al Bell to grant the performer's demands. As a result, Hayes felt no pressure to produce a commercially successful record as “my album was to be just one out of twenty-eight (and) the spotlight wouldn't fall on me. So,” he recalled, “I just went in to the studios and did just as I wanted to.”Footnote 28 The result, Hot Buttered Soul, was a work of black artistic creativity unusual within the rhythm and blues genre. It introduced numerous elements which characterized his next four albums and culminated with Black Moses, all released during a key period in the evolving long African American freedom movement. The records each presented Isaac Hayes as a transcendent figure in American popular culture whose art and self-presentation challenged existing norms concerning black masculinity and musical expectations. Stax packaged Black Moses to evoke a literal interpretation of its equally audacious title.

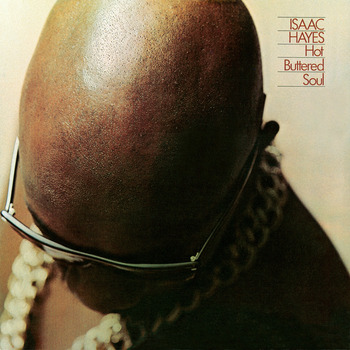

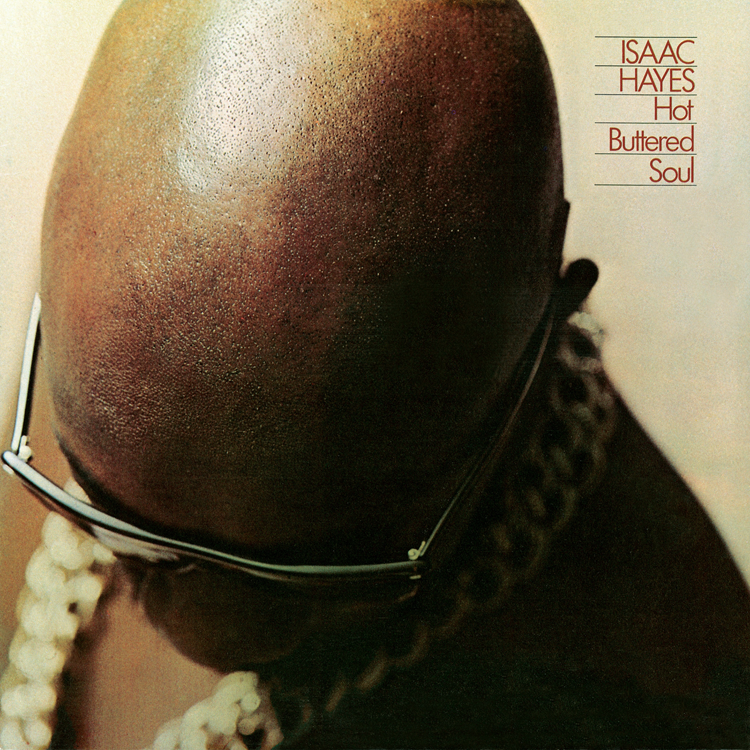

Larry Shaw, the head of advertising at Stax, claimed that his label “put an inordinate amount of money into that album jacket” in order “to capture fully all the things about [Isaac Hayes] that were not in the record. The record,” Shaw told writer Rob Bowman, “was the box” and it presented Hayes as a grandiose cultural figure who transcended musical virtuosity.Footnote 29 The Black Moses cover featured a head-shot of Isaac Hayes wearing sunglasses and a striped multicolored hooded cloak while looking slightly up to the distant heavens (Figure 1). The jacket unfolded to reveal the cover's true magnanimity, which was a four-foot by three-foot, cross-shaped poster of Hayes displayed as an Old Testament-like prophet. In the print, Hayes wore sandals and an ankle-length robe while he stood on the banks of a large body of water. Each arm extended outward from the side with his palms upturned, which suggested that he both embraced and sacrificed himself for the viewer (Figure 2). On the record's back cover, two stone tables that resembled the Ten Commandments listed the individual song titles. Most importantly, the album's sleeve told a story of biblical proportion about “the budding young prophet” who came from a region near “the ancient Cotton Kingdom of Memphis” to lead “the chosen people” against “the blind and mindless forces of racial hatred and bigotry.” The ornate description equated the Nile river to the Mississippi, claimed “racist and xenophobic Pharaohs” killed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and proclaimed that “the Lord” revealed himself to Hayes through a “burning bush.” Now a “major prophet,” the narrative concluded, “Black Moses” led the “favored few.”Footnote 30 The religious references portrayed “Black Moses” as a persona that linked his followers to an ancestral African past that is a central component of black authenticity, the existence of which legitimized Hayes as an artist whose work represented cultural liberation. Black Moses, in appearance and substance, transformed Isaac Hayes into what Jet senior editor Chester Higgins called “a soulful prophet of the Chosen People, a willing servant of the Lord, and one helluva entertaining genius.”Footnote 31 The album jacket, therefore, glorified a figure whose appearance undermined the existing “black macho” archetype in several ways.

Figure 1. The resplendent cover of Black Moses. Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group.

Figure 2. Black Moses folded fully out in its cross-shaped glory. Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group.

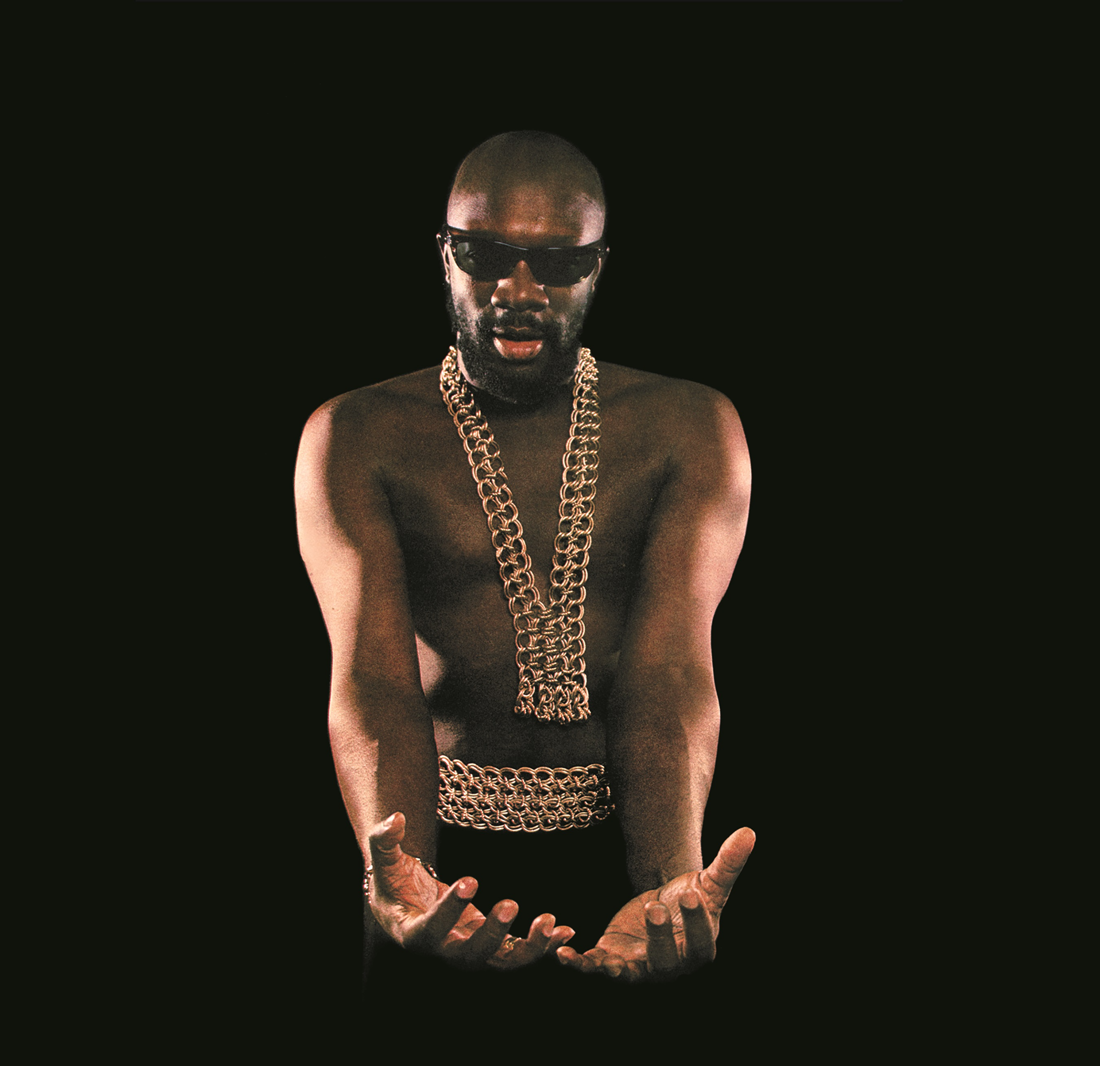

The novel look started with the hairstyle or, rather, lack thereof, that Isaac Hayes sported. In the mid-1960s, he tried to straighten his hair in the fashion of many contemporary black musicians, including James Brown. Yet Hayes believed a that processed hairstyle “was a pain in the ass to keep up” and much too hot for the Memphis seasons, so he shaved his head but kept his beard because “I liked being different.” Al Bell remember the look as boldly unique because “bald heads weren't popular back then.”Footnote 32 Indeed, historian Tanisha Ford observed, “In the early 1960s, the dividing line” between black cultural authenticity “was between straightened and natural hair. By the early 1970s, it was about who could ’fro their hair and who could not.” At the time Stax released Black Moses, influential cultural figures such as James Brown, Nina Simone, and the Black Panthers, among others, had popularized the Afro and made it what William Van Deburg characterized as “a highly visible imprimatur of blackness; a tribute to group unity; a statement of self-love and personal significance.” The rounder and more full, Ford declared, “the better, because the Afro, more than any other natural hairstyle, became symbolic of one's black consciousness.”Footnote 33 The distinctive bald head, particularly when combined with his lean, muscular, nearly six-foot-tall frame, attracted much attention, so Hayes kept it for the remainder of his life. In an age when the Afro reflected racial pride for black men and women, the image of Isaac Hayes that adorned the cover of 1969's Hot Buttered Soul represented a cultural statement which, according to Rob Bowman, “signified for many an in-your-face declaration of blackness.” The photograph of Hayes's bare head taken from a high angle while he glanced downward slightly to his right behind dark sunglasses, shirtless, wearing thick golden links fastened together around his neck, made for a striking and unforgettable image (Figure 3).Footnote 34 The album cover of The Isaac Hayes Movement, the follow-up to Hot Buttered Soul, built upon the distinctive image and unfolded into a vertical photograph of the shirtless artist adorned in dark sunglasses with thick gold chains around his neck and waist. Hayes reached his arms forward and down to the viewer with a physique Jet magazine compared to “a Mandingo daddy” which, in referencing the popular 1957 novel Mandingo, connected Hayes ironically to prevailing stereotypes concerning black male hypersexuality.Footnote 35 Black Moses, then, advanced and magnified the way Isaac Hayes used album covers as a means of artistic self-expression and cultural liberation to project an image of confident masculinity that challenged the contemporary mainstream.

Figure 3. The iconic Hot Buttered Soul album jacket. Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group.

His eclectic fashion sense also played a critical role in the way Isaac Hayes expressed himself on the Black Moses cover and beyond. Style, as Tanisha Ford demonstrated, is a vital yet underappreciated aspect of the long black freedom struggle because it represents “a powerful symbol of black resistance and rebellion.” Fashion theorist Carol Tulloch agreed that style is indicative of personal agency because it indicates “the construction of self through the assemblage of garments, accessories, and beauty regimes that may, or may not, be ‘in fashion’ at the time of use.”Footnote 36 The Black Panthers, observed historian Robyn Spencer, “devised chic and stylish uniforms: black slacks, a powder blue shirt or turtleneck, a black leather jacket, and a black berets, rakishly tilted to one side.” According to Panthers cofounder Bobby Seale, the outfit represented what Spencer labeled “a symbol of powerful masculinity to be emulated.”Footnote 37 The multicolored robe that Hayes adorned on the Black Moses cover, though, was the antithesis of the Panther's look. The album jacket described the clothing the “prophet” wore as “so bright, so colorful, so kaleidoscopic, he can be looked upon only by indirection.” It is unclear if his fashion choices or deity-like aura prevented observers from gazing upon “Black Moses” directly. Regardless, the narrative described his wardrobe as “a raiment that embodies the colors of hot pinks, purples, reds. The fashions feature a bare torso under a long flowing cape, a big floppy hat covering a bald and shining head,” with “legs and hips encased in salmon ink panty hose. For as a man dresseth, so is he.”Footnote 38 Hayes lived the philosophy, which blurred the lines between himself and the Black Moses persona and fascinated those who reviewed his art.

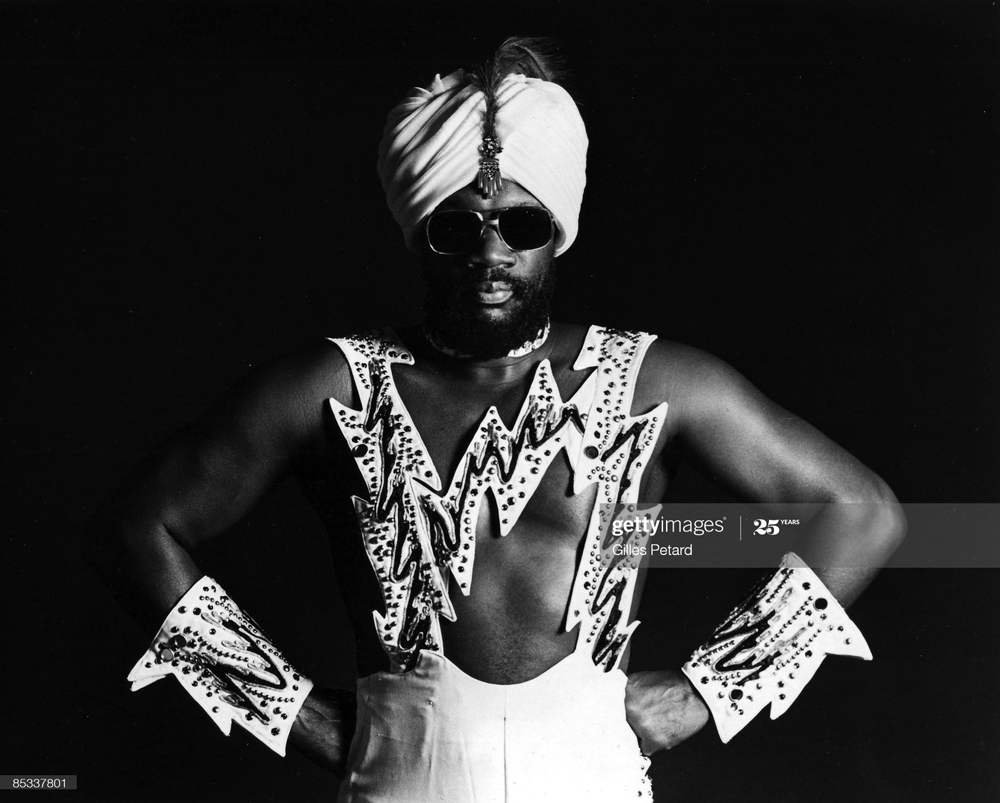

Numerous magazine articles detailed Isaac Hayes's elaborate outfits. One Jet piece compared him to a “strutting, virile peacock” and “a slightly malevolent genii [sic] squeezed, colorful plumage and all, out of Aladdin's magic lamp” (Figure 4). The journalist described Hayes's attire from “way out to absolutely weird,” and detailed that the performer, “a highly unconventional dresser,” could take the stage wearing “cranberry colored tights, striped fur Eskimo boots, a buckskin or suede vest with beaded thongs naked to the waist; a zebra-like cloak, or a Russian, military-appearing cape, bright colored scarf, heavy fur or a big floppy hat.”Footnote 39 Descriptions of his “multi-hued poncho,” “big black hat,” “tight tights,” “fur capes,” “black ’n’ white furry boots, gold chains, glinting shades and shaven armpits” often preceded album and concert reviews. Hayes wore “an electric blue suit, startingly trimmed in gorgeous white mink” to the 1972 Oscars ceremony, while an English columnist who attended his concert claimed that the performer “looked like the world's first blind all-in wrestler.” He sat for a Rolling Stone interview sporting only “a long robe of Indian cloth and wine-colored silk socks” the day after he took to the New York Philharmonic Concert Hall stage adorned with “a sort of British magistrate's wig fashioned out of straw, a long mantle of African cloth and a grass skirt.”Footnote 40 According to Stax executive Al Bell, “I have never seen anybody dressed like Isaac Hayes.” The way he “combined colors,” Bell recalled, was “absolutely unique” (Figure 5).Footnote 41 Hayes's dress, therefore, represented a conscious degree of cultural and historical subversion, as young black men in the South drew attention to themselves at the risk of attracting a lynch mob's fury. Sunglasses and gold chains became vital parts of his public identity, with the latter playing a particularly subversive role. He wanted his followers, Hayes told the audience during a 1973 appearance on the Soul Train television program, to interpret the accessory “in a positive manner” because his chains “made a mockery of what they once represented to the black man in the United States.”Footnote 42 The display of golden chains against his bare chest during public performances, then, embodied much more that the trappings of soul superstardom and financial success – they inverted a symbol of black enslavement and emasculation in a direct way (Figure 6). As Village Voice writer Carol Cooper noted some years later, Isaac Hayes projected “a sexy image and a warrior image” that “blew Brer Rabbit's timidity” into a bygone era.Footnote 43 Bar-Kays drummer Willie Hall put it more succinctly in saying, ““Isaac was just cool as shit.”Footnote 44 Yet Hayes used more than fashion, baldness, and a confident self-presentation to undermine the singular notion of black heterosexual masculinity that existed at the time. His music, in numerous ways, revealed a creativity uninfluenced by white-imposed standards, which epitomized the long freedom struggle's demand that African Americans advance cultural liberation and express themselves as individuals.

Figure 4. “Black Moses” as “a slightly malevolent” genie or “blind all-in wrestler.” Photo by Gilles Petard/Redferns, courtesy of Getty Images.

Figure 5. The eclectic style of Isaac Hayes. Photo by GAB Archive/Redferns, courtesy of Getty Images.

Figure 6. The golden chains that became a central accessory to the “Black Moses” persona featured prominently in The Isaac Hayes Movement bi-fold. Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group.

First, Isaac Hayes emphasized the album as more than a collection of hit singles for an African American audience. While black popular artists remained confined to the three-minute single for a variety of reasons, Hot Buttered Soul only contained four songs, two per record side, that averaged eleven minutes and twenty-three seconds in length. On the four non-soundtrack studio LPs that Hayes released between September 1969 and November 1971, he recorded twenty-seven songs that averaged nine minutes and eleven seconds because “I always wanted to present songs as dramas. It was something white artists did so well but black folks hadn't gotten into.” Besides, he stated in another interview, “I didn't give a damn if [records] didn't sell because I was going for the true artistic side” and “what I had to say couldn't be said in two minutes and thirty seconds.”Footnote 45 Jet editor Chester Higgins praised Hayes's artistic “audacity” for using an eleven-minute monologue to introduce one song and compared him to jazz musician John Coltrane. Critic Ken Tucker similarly opined that Hayes made “soul music as a jazz musician might, lengthening and improvising on a single idea.”Footnote 46 Isaac Hayes, then, presented the full-length album as a viable cultural medium for black musicians and audiences as it had been for whites. The trend peaked with Black Moses. The shortest of the fourteen tracks on the double LP clocked in at just under five minutes long, while four songs surpassed nine minutes. Black Moses continued the pattern established by Hayes that one music journalist claimed “almost single-handedly freed black American music from the shackles of the three-minute single, while at the same time opening the floodgates for black artists to the lucrative FM-pop market” which played longer songs. The record proved that significant numbers of black consumers would purchase multi-disc album sets and efforts from Funkadelic, James Brown, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, and Earth, Wind, and Fire followed the precedent Black Moses established less than a decade after its debut.Footnote 47

In addition to their length, the source and arrangement of many Hayes songs also distinguished him from other black popular artists of the time and demonstrated the incomparable nature of his cultural self-expression. In a marked departure from the formulaic sales-driven singles that characterized the “Motown sound” for much of the 1960s, rhythm and blues artists emphasized the social, political, and economic plight of African Americans as the decade neared its end. “The sound of soul,” Brian Ward contended, “seemed to darken audibly during this period of rising nationalist sentiment” and black audiences increasingly expected musicians to address the stark realities of African American life and provide commentary on the state of contemporary race relations.Footnote 48 Marvin Gaye's What's Going On, released approximately six months before Black Moses, best exemplifies Ward's insight. In contrast, Isaac Hayes provided no social observations through his lyrics and, instead, often reimagined songs that other artists inside and outside of the rhythm and blues genre composed. Hot Buttered Soul, for instance, only contained one song that Hayes himself wrote, the imaginatively titled “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic.” Burt Bacharach and Hal David wrote the Hayes rendition of “Walk on By,” a song Dione Warwick previously popularized, and composer Jimmy Webb penned “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” which country star Glen Campbell won two Grammy Awards for recording in 1967. Consequentially, historian Alice Echols described Hot Buttered Soul as “a cross between lounge music, movie soundtrack, and R & B” which revealed “a penchant for the truly offbeat.”Footnote 49 Hayes continued to reinterpret the works of others on his next five albums and recorded songs on Black Moses that Burt Bacharacht and Hal David, Curtis Mayfield, Kris Kristofferson, Jerry Butler, Clay Hammond, and Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff wrote for other performers, including Aretha Franklin and the Carpenters. The opening song on and first single from Black Moses, “Never Can Say Goodbye,” reached number two on the US pop charts earlier in the year as a Jackson Five release. “Working on other people's songs,” Hayes explained, “gives me room to stretch myself more fully” as an artist because “I see myself as an arranger.” He incorporated elements into familiar songs that reflected his symphonic classical music, jazz, be-bop, blues, gospel, and soul influences in way that allowed him to “express myself the way I want to, the way Isaac Hayes wants to express himself” To that end, the Memphis Symphony Orchestra played on multiple Black Moses songs. His unique layout of “huge lush orchestrations on top with a funky underlying rhythm,” Hayes claimed, took each song “into a completely different world” that combined an “R & B feeling” with a “more sophisticated” production. His artistic arrangements, compositions, and productions displayed a tremendous degree of musical freedom that black artists possessed as the 1970s began, but the most ambitious application of creative license that Isaac Hayes contributed to American music was his use of the spoken monologue to introduce songs. He called this device “the rap.”Footnote 50

The “rap” of Isaac Hayes stemmed from the spoken-word tradition within African American musical expression. The practice originated within slave communities during field labor in what ethnomusicologist Ronald Radano labeled a unique “Negro sound” developed to communicate messages, maintain African cultural roots, and resist bondage. An integral component of the tradition became the spoken word, which sociologist Valerie Chepp defined as “artistic cultural expressions communicated through orality and performance, carried out in the presence of an audience or community of listening spectators.” The spoken word remained a central theme in black music after emancipation and persisted, Chepp argued, as one of the “‘partially hidden’ cultural sites where marginalized African American communities have historically challenged the systems of inequality.”Footnote 51 Numerous gospel groups, blues performers, and popular recording artists from Louis Jordan to Solomon Burke blurred the line between song and speech and used it as a familiar conversational device, which placed Isaac Hayes firmly within a unique African American musical tradition. Yet he used the technique for reasons more mundane that resisting an oppressive power structure or providing commentary to assert his autonomy. Hayes implemented the rap out of necessity, which exemplified both continuity and change within the black musical tradition and further epitomized the unique masculine identity of “Black Moses.”

Because Isaac Hayes covered many songs unfamiliar to a predominately black audience, he utilized the monologues to communicate a dramatic story and establish the appropriate mood as he segued into song. His first recorded use of the rap introduced “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” on Hot Buttered Soul. The raps lengthened songs considerably, as Hayes preferred to record them live with no retake to “preserve the vibe” of each lyric. “Phoenix,” for instance, lasted eighteen minutes and forty-two seconds.Footnote 52 By the time of the release of Black Moses, the rap had become a familiar and effective way in which Isaac Hayes communicated to listeners, and the double album included multiple such monologues. Its use, one critic observed, “conveyed a sense of majestic freedom, a welcome balm from the neurotic ‘sock-it-to-me, uptight’ soul music of the time.”Footnote 53 Indeed, the rap became a mainstay for many African American recording artists during the 1970s, including Barry White, Curtis Mayfield, and George Clinton, among others, and became the foundation of the hip-hop genre which flourished approximately a decade after the release of Black Moses. Not surprisingly, the originality of Hayes's art defied simple classification and his records charted simultaneously on the jazz, pop, R & B, and easy listening charts. Cultural scholar Alice Echols claimed that Isaac Hayes's music “anticipated disco” with its “repetitiousness, outsized tracks, orchestration, and audacious covers of unlikely songs,” while music writer Jim Farber characterized the work of Hayes as “symphonic soul” or “psychedelic soul.” Whatever the label, Melody Maker magazine contemporaneously deemed Hayes “the man who gave a new direction to black music” during the early 1970s.Footnote 54 That artistic originality and creativity carried over into the song lyrics, which indicated that Hayes embodied an alternative model of black masculinity as the 1970s began.

The raps that Isaac Hayes delivered on his albums often set the emotional stage for songs whose themes repudiated the black macho ideal of African American masculinity. The topics did not capture “the sound of young America,” which Motown claimed to represent, and the chosen songs did not resemble the conventional soul tracks Hayes wrote with David Porter. “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” for instance, addressed the challenges of a man dealing with an unfaithful woman whom he still loved after the eighth time he caught her in bed with another man. Bar-Kays drummer Willie Hall often performed the song live with Hayes and claimed that by the time he began singing, “people in the audience would be crying, Isaac would be crying. I'd be crying, the background singers would be crying – because we could relate to the situation.”Footnote 55 Songs on subsequent records honestly detailed an emotional vulnerability, as evidenced by titles like “One Big Unhappy Family,” “You've Lost That Loving Feeling,” and “I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself.” On Black Moses, Hayes performed versions of “Never Can Say Goodbye,” “I'll Never Fall in Love Again,” “Nothing Takes the Place of You,” “Help Me Love,” and “Need to Belong to Someone.” The use of lyrics such as “You put the hurt on me, you socked it to me momma, when you said goodbye,” exposed an artist in touch with his most primal emotions. The spontaneity and genuineness of the lyrical delivery suggested, one writer observed, “a very big heart in this very big man … that was evidently broken into thousands of pieces.”Footnote 56 Yet Hayes presented his vulnerability as a virtue, not a deficiency. His confidence, appearance, and, according to one female columnist, “deep, throaty, oh so sexy voice” embodied a kind of African American heterosexual manhood that contradicted the dominant black “militant masculinity” archetype that a popular figure such as James Brown represented. Brown biographer R. J. Smith juxtaposed his subject with “Black Moses” by proclaiming the latter “a composer who was as cool as Brown was agitated, turned inward where Brown was ready to explode. Isaac Hayes,” Smith observed, “was a new breed of star” due in significant part to the unguarded sensitivity of his lyrics.Footnote 57

Yet while Isaac Hayes used his lyrics to convey what Alice Echols described as “emotions usually considered unseemly in men,” the performer used the lyrical vulnerability for decidedly heterosexual ends.Footnote 58 The emotional honesty enhanced his appeal with women, which lifelong friend Mickey Gregory said, “was all he lived for … Nothing,” he continued, “was more important to Isaac than women being attracted to him.” His onstage valet characterized “Black Moses” more directly as a “freak (who) had women all over Memphis.” Likewise, Willie Hall remembered Hayes a “one hell of a womanizer,” while journalists typically referenced his sexual magnetism and appreciation of female companionship. Author Robert Gordon recalled that with his “bare-chested, well muscled, skin-tight pants that bulged in all the right places,” the artist “unleased a new male sexuality that made James Brown seem like a drag queen.” It is little wonder that soul music writer Bob Davis claimed Hayes's albums “changed the bedroom habits of an entire generation!”Footnote 59

In stretching the boundaries of traits considered appropriate for African American men in the late 1960s and the 1970s, Isaac Hayes demonstrated that the contemporary conceptualization of black masculinity was not singular. Variables such as race, class, gender, region, and sexuality created distinctions between, and (as Africana studies scholar Riché Richardson demonstrated) hierarchies among, black men, and Hayes placed himself at the pinnacle of such by using his music, lyrical choice, and confident self-preservation to maximize his number of female sexual conquests. Yet this does not mean that Hayes represented an oppositional figure to the persistence of toxic masculinity within contemporary culture or the evolving freedom struggle. The projection of emotional tenderness, honesty, and availability by Hayes provided a stark contrast to the misogynistic attitudes toward women expressed within the black macho ideal that Michelle Wallace outlined, but both approaches shared the ultimate goal of female sexual conquest. Hayes's conscious vulnerability represented the “intensified contestations over definitions of black masculinity” that Richardson claimed characterized the era, but many of his closest friends and associates later recalled how those traits provided Hayes with the opportunity to bed numerous females.Footnote 60 The fact that Isaac Hayes projected an alternative means to achieving decidedly heterosexual ends for African American men demonstrates how alternative models of black masculinity did not represent a thorough subversion of existing gender constructs. The long freedom struggle, therefore, provided artists the power and opportunity to create alternative conceptions of black masculinity as the 1970s began, and no one did so as publicly as Isaac Hayes.

In addition to his unique sense of style, musical virtuosity, and lyrical selection, Hayes also made economic extravagance and social activism key components of his masculine identity and creative self-liberation. The accomplishments of Hot Buttered Soul, Black Moses, and, most famously, The Soundtrack from ‘Shaft’ made “Black Moses” a very rich man, and he made little effort to conceal his material wealth. On the contrary, Hayes displayed his money conspicuously in ways that buttressed his unique masculinity and remain the stuff of legend. By the mid-1970s, Hayes had accumulated three homes, including a $460,000 fourteen-room mansion in East Memphis, six motorcycles, ostentatious jewelry, and a large collection of new and vintage Smith and Wesson pistols. On a 1973 trip to Britain, he “spent £38,000 on jewelry and another £30,000 on a custom-built red and grey Rolls-Royce.” He designed his own clothes and had a Hollywood tailor make them to his exact measurements. Hayes also employed a salaried staff of full-time assistants that reached at least seventy-five people who served as his agents, attorneys, business advisers, bodyguards, public-relations personnel, secretaries, valets, chauffeurs, personal trainers, and concert dancers, among others. The automobiles, though, were his most lavish expenditure. At his peak, Hayes owned nine luxury vehicles, including the Rolls Royce, three limousines, two Jaguars, and two customized Cadillac Eldorados. He obtained his first Cadillac as part of the new contract he negotiated with Stax Records in 1972 after he received seven Grammy nominations and “The Theme from Shaft” made Hayes the first artist in label history to sell over a million singles. The $26,000 sea blue Eldorado had gold-plated wheels, wiper blades, and interior features. Not one to settle for extravagant accessories alone, his 1974 model, Jet magazine detailed, “is a silver-grey monster … fitted with carpet, a closed-circuit television link between passenger and driver, telephone system, bar, refrigerator … a thundering quadraphonic stereo set” and, of course, “a wrap-around love seat in the passenger compartment.”Footnote 61

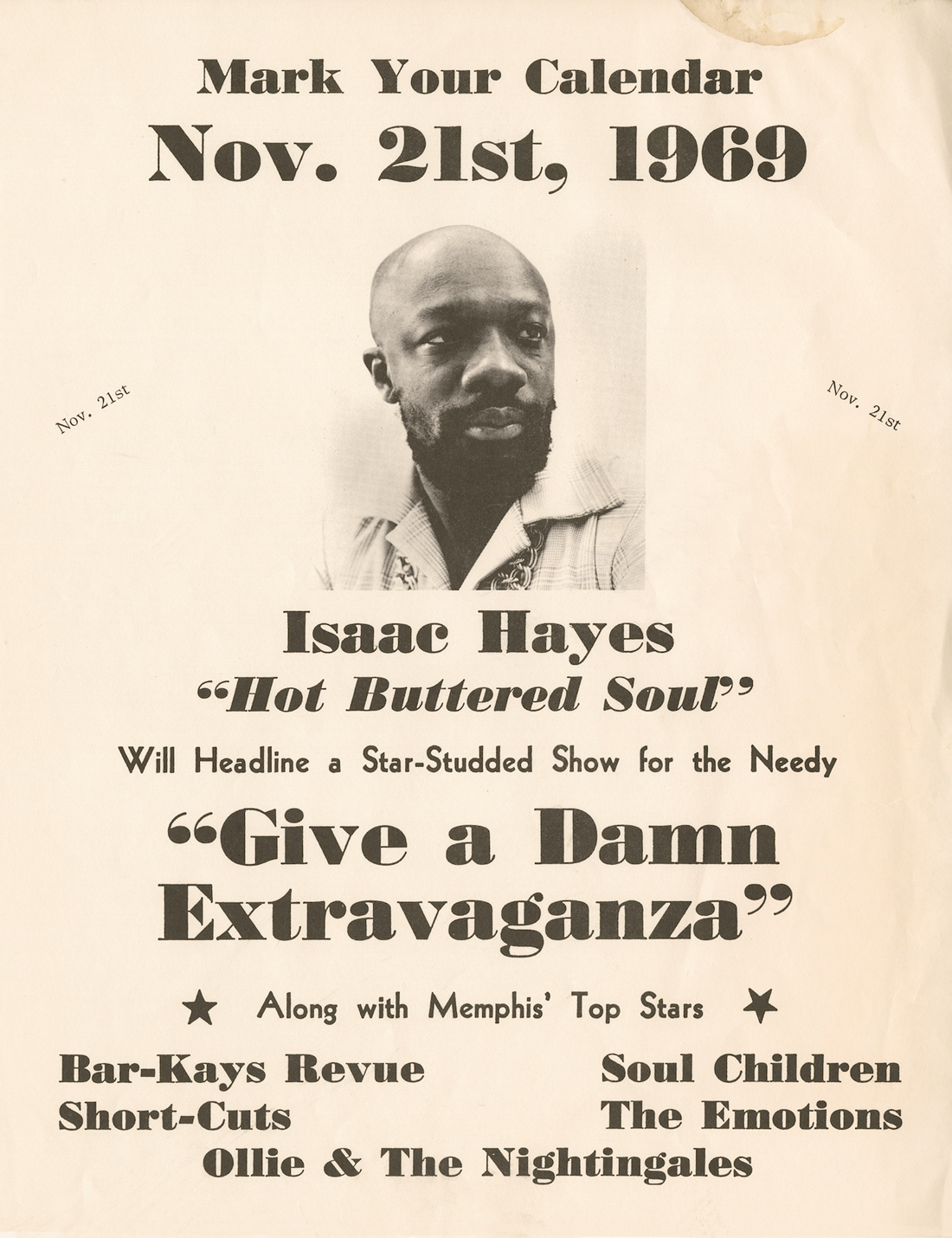

The material excess demonstrated that Isaac Hayes achieved the financial empowerment which leaders within the black freedom struggle demanded as a necessary step toward racial equality and became a vital component of his contemporary masculine self-presentation. Hayes supported the nonviolent movement and participated in the 28 March 1968 Memphis sanitation workers’ strike that that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led. The protest descended into chaos and violence, and Hayes recalled seeing “gas and dogs and all that shit” as he helped a group of nuns seek refuge in a church. The subsequent 4 April assassination of King “devastated” Hayes to the point where he could not work for the next twelve months. He ultimately determined, as he told journalist Tim Sampson, “that there was nothing [Hayes] could do about it other than to become successful and powerful enough to have a voice and make a difference.”Footnote 62 Hayes considered the wealth that came with his popular success “de facto liberation – the first minute of a very new day.”Footnote 63 He showcased his financial prosperity in part, Hayes maintained, to give “black people something toward which they can aspire. I'm proving they are as good as anyone else.”Footnote 64 To validate his outlook, Hayes used his wealth and celebrity to heighten awareness concerning the challenges that blacks still encountered beyond the era of legalized public desegregation in America (Figure 7). Yet his perspective on economic prosperity proved different to those of other contemporaneous black power icons such as James Brown and the Black Panther Party.

Figure 7. Advertisement for the “Give a Damn Extravaganza,” the “Star-Studded Show for the Needy” in Memphis that Hayes headlined. Item courtesy of Concord Music Group.

Isaac Hayes embraced the materialism and conspicuous consumption that supplemented his masculine self-presentation, which rejected the Marxist ideals of the Black Panthers. His use of wealth, however, also differed from the conciliatory, conservative, accommodationist version of black entrepreneurship that James Brown championed. According to historian James West, Brown's “bootstraps rhetoric” presented black power as a “manageable and controllable” form of “acceptable” activism that reinforced “a conservative economic agenda” that mainstream media outlets and politicians such as Richard Nixon endorsed. Yet the entrepreneurial endeavors that Brown supported, as West observed, did little for African Americans without access to investment capital.Footnote 65 Isaac Hayes, in contrast to Brown's black capitalism objectives, used his wealth to inspire the poorest blacks and pledged on multiple occasions to invest more than half of his income in projects for the impoverished that limited opportunities for personal economic return. In 1971, Hayes purchased apartments for two hundred senior citizens who lost their homes in a Memphis fire. Later that year, he started the Hayes Foundation to develop philanthropic endeavors that he hoped would “alleviate suffering wherever and whenever possible.” Hayes served on the board of directors with Julian Bond and Jesse Jackson and pledged to “share my good fortune” with “people who are shunted aside, ignored by society and forced to live under conditions of purposeless despair.”Footnote 66 He also funded an eight-million-dollar housing project for destitute citizens in the Virgin Islands and explored other low-cost housing investments for Native Americans, Mexican immigrants, poor whites, and African American communities throughout the country.Footnote 67 In addition to his charitable pursuits, Hayes served as vice chairman of the Memphis Black Knights, an organization formed after Dr. King's assassination to work against police brutality, job discrimination, and inadequate housing in Memphis. He told Rolling Stone magazine that while he believed in “using tact and intelligence” to confront the local white power structure, “I'm not the turn-the-other-cheek kind of person.”Footnote 68 To that end, Hayes explained his motivations to a reporter that remain relevant almost fifty years later:

People sometimes criticise [sic] entertainers and say “What right have they to set themselves up as political philosophers, what do they know about it?” Well, our right lies in us being people, just like everyone else. We are affected by what's going on and we know about it because, just like everyone else, we experience it all. But unlike most people we are fortunate in having access to the media so we can express our feelings and through these, those of others. People listen to us rather than to politicians who've lost touch with the things that affect people's lives.Footnote 69

Hayes later recalled that many interpreted his look – the gold chains, bald head, beard, dark shades, ostentatious dress – as racially militant, when he defined it as speaking out and acting against racial oppression. In that regard, Hayes admitted, “I was militant.”Footnote 70 The social consciousness of Isaac Hayes, and of Stax Records as a whole, culminated with the label's Wattstax concert in Los Angeles on 20 August 1972, which was meant to raise much-needed funds for those who still struggled to recover from the nation's most destructive urban uprising seven years after it transpired.Footnote 71 The event best represented the fusion of economic empowerment, social activism, and cultural autonomy that “Black Moses” embodied as the African American freedom struggle advanced into and beyond the 1970s.

In conclusion, Isaac Hayes provides a vital figure through which scholars can analyze, evaluate, and more fully understand the revolutionary nature of the long black freedom struggle as it progressed into the 1970s. Through his “Black Moses” persona and album of the same name, Hayes created an alternative model of contemporary African American manhood that demonstrated that the dominant conceptualization of black masculinity was not monolithic. Hayes introduced and embodied an ideal that undermined the dominant notions of black manhood which pervaded popular culture and remains a central component of popular memory concerning black power. Hayes's preference to record songs that artists previously composed for a predominately white audience, creative arrangements and musical experimentation in the studio, and refusal to conform to the three-minute length that constrained the contemporary R & B single presented the album as a viable medium for African American artists and consumers. Furthermore, his signature “raps” inspired countless black musicians and became a staple of an emergent hip-hop genre, while over eighty subsequent artists – including Beyonce, Wu-Tang, Biggie Smalls, and Tupac Shakur – sampled Hayes's work on their own albums.Footnote 72 Most importantly, Isaac Hayes impugned the prevailing “black macho” ideal. “Black Moses” exuded sensuality and vulnerability, placed female needs and desires above his own, and publicly expressed the emotional highs and lows that relationships brought in a very personal manner. His appearance reinforced a new standard in black male self-definition, while his opulent lifestyle and conspicuous display of wealth conveyed a sense of financial empowerment and economic possibility that remained central to the long freedom struggle. Finally, his social activism and charitable endeavors indicate that Hayes believed, to some degree, that his success came with an obligation to improve life for the impoverished and victimized. “Black Moses,” therefore, embodied the freedom of African Americans to move beyond contemporary racial classifications in a cultural capacity and presents scholars with a fascinating model through which to examine the intersection of race, black male identity, popular culture, and the continuous quest for personal power through an unrestricted self-expression that characterizes the persisting struggle for complete liberation in the United States.