1. Introduction

Lower respiratory tract infections are among the top 10 causes of death worldwide and are of particular relevance in chronic lung diseases. Lysozyme is one of the most abundant antimicrobial proteins in the airways and alveoli. The concentration of this enzyme in the surface liquid of the human airway is estimated to be 20–100 µg ml−1, which is sufficient to kill important pulmonary pathogens such as Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Travis et al. Reference Travis, Conway, Zabner, Smith, Anderson, Singh, Greenberg and Welsh1999). Klebsiella pneumoniae, which is a frequent cause of nosocomial infection and may be responsible for up to 20% of the respiratory infections in neonatal intensive care units (Gupta, Reference Gupta2002), is also specifically attacked by lysozyme (Markart et al. Reference Markart, Korfhagen, Weaver and Akinbi2004).

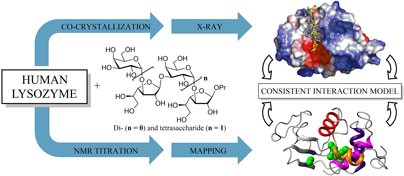

Human lysozyme (HL, also known as muramidase, N-acetyl muramide glycanohydrolase, or EC 3.2.1.17; Fig. 1 a) is a 130-amino acid cationic protein that cleaves the glycosidic bonds of N-acetyl-muramic acid (Fig. 1 c), thereby damaging the bacterial cell wall (Fig. 1 b) and ultimately killing bacteria by lysis in cooperation with defensins. An inter-domain cleft in HL contains six binding pockets (labeled A–F in Fig. 1 a), and a strictly conserved catalytic residue Glu35 is located between the D and E sites (Chipman & Sharon, Reference Chipman and Sharon1969). Co-crystallization of HL with N-acetyl-chitohexaose (GlcNAc)6 (Fig. 1 c) has revealed а crystal structure with non-covalently linked (GlcNAc)4 and (GlcNAc)2 in subsites A–D and E–F, respectively (Song et al. Reference Song, Inaka, Maenaka and Matsushima1994).

Fig. 1. Lysozyme and its carbohydrate ligands (a) Structure of HL (PDB code 1LZS) with selected residues (Glu35, Asp53, and Trp109). Binding sites A–F are indicated by letters in green circles. Helices are colored as follows: a, violet; b, magenta; c, red; d, orange. In the orientation shown, the α-domain is to the right of the binding cleft and the β-domain is to the left. (b) Schematic drawing of the LPS molecule and its position in the outer layer of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria; for clarity, membrane associated proteins and integral membrane proteins are not shown. (c) Hydrolysis of the (1→4)-glycosidic bond between N-acetyl muramic acid and N-acetyl glucosamine in the peptidoglycan. (d) Structures of the repeating unit of the O-chain of the K. pneumoniae O1 lipopolysaccharide and the structurally related synthetic disaccharide 1 and tetrasaccharide 2. Monosaccharide units are numbered with Roman numerals.

In addition to the well-known muramidase activity of HL, increasing evidence suggests the existence of non-enzymatic and/or nonlytic modes of action against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Lee-Huang et al. Reference Lee-Huang, Maiorov, Huang, Ng, Lee, Chang, Kallenbach, Huang and Chen2005; Masschalck & Michiels, Reference Masschalck and Michiels2003). Furthermore, lysozyme has antitumor (Osserman et al. Reference Osserman, Klockars, Halper and Fischel1973) and antiviral activities (Lee-Huang et al. Reference Lee-Huang, Maiorov, Huang, Ng, Lee, Chang, Kallenbach, Huang and Chen2005), and it enhances the immune system (Siwicki et al. Reference Siwicki, Klein, Morand, Kiczka and Studnicka1998). The mechanisms of these activities remain unclear, and the dominant questions involve how HL recognizes pathogenic microbes.

Bacterial LPSs represent the group of important virulence factors, which are recognized by antibodies and pattern recognition receptors in the initial steps of innate immune response to Gram-negative bacteria. These processes and their physico-chemical characteristics were previously studied using surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-method (Shin et al. Reference Shin, Lee, Park, Hyun, Sohn, Lee and Kim2007; Young e t al. Reference Young, Gidney, Gudmundsson, MacKenzie, To, Watson and Bundle1999). The ability of lysozyme to interact with lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) was demonstrated in the late 1980s (Ohno & Morrison, Reference Ohno and Morrison1989a, Reference Ohno and Morrisonb). However, the details of this interaction (i.e. how binding specificity is established between specific parts of the lysozyme protein and the LPS carbohydrate units) have not been examined. The attraction between lysozyme and LPS has been largely attributed to non-specific hydrophobic interactions of lysozyme with lipid A, which is the innermost hydrophobic component of LPS and is primarily responsible for its toxicity. To examine whether lysozyme specifically interacts with bacterial LPS and particularly with the O-chains that form the outer layer of the bacterial cell wall, we performed SPR-based experiments as previously described (Tsvetkov et al. Reference Tsvetkov, Burg-Roderfeld, Loers, Ardá, Sukhova, Khatuntseva, Grachev, Chizhov, Siebert, Schachner, Jiménez-Barbero and Nifantiev2012). By SPR experiments we detected the interaction between HL and LPS from K. pneumoniae O1, which is associated with the development of severe hospital-acquired infections and is clinically relevant to infections beyond those of the airways (Enani, Reference Enani2015; Enani & El-Khizzi, Reference Enani and El-Khizzi2012). SPR permitted to measure corresponding dissociation constant (K d) of 0·41 mM and association and dissociation rate constants (k a and k d) of 216 M−1 s−1 and 0·0886 s−1, respectively (online Fig. S1 in Supplementary Information). To assess whether the O-chains of these LPSs were involved in the observed interactions, we combined nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), molecular modeling, data mining and X-ray crystallography techniques to investigate HL binding to synthetic disaccharide 1 (Krylov et al. Reference Krylov, Argunov, Vinnitskiy, Verkhnyatskaya, Gerbst, Ustyuzhanina, Dmitrenok, Huebner, Holst, Siebert and Nifantiev2014) and tetrasaccharide 2 (Fig. 1 d), which represented one and two repeating units of the O-chain of K. pneumoniae O1, respectively, at the sub-molecular level.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Lysozyme

Recombinant HL was provided by T. E. Weaver (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, USA). The HL was purified as previously described for other lysozymes (Akinbi et al. Reference Akinbi, Epaud, Bhatt and Weaver2000; Markart et al. Reference Markart, Korfhagen, Weaver and Akinbi2004).

2.2 Oligosaccharides

The synthesis of disaccharide 1 was performed using the recently discovered pyranoside-into-furanoside rearrangement (Krylov et al. Reference Krylov, Argunov, Vinnitskiy, Verkhnyatskaya, Gerbst, Ustyuzhanina, Dmitrenok, Huebner, Holst, Siebert and Nifantiev2014, Reference Krylov, Argunov, Vinnitskiy, Gerbst, Ustyuzhanina, Dmitrenok and Nifantiev2016). The synthesis of tetrasaccharide 2 (Verkhnyatskaya et al. Reference Verkhnyatskaya, Krylov and Nifantiev2017) was based on similar approaches and is described in the online supplementary information (Scheme S1).

2.3 SPR analysis

SPR was performed on a protein interaction array system (ProteOn XPR36, Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Vertical channels of a GLM sensor chip were activated with undiluted EDAC-sNHS 1:1 mixtures according to the amine coupling kit (Biorad). HL was immobilized from 100 µg ml−1 solutions in 10 mM acetate buffer pH 4·5 on the activated sides of channel. Remaining active sides of the channels were blocked by treatment with 1 M ethanolamine. All steps were performed in phosphate buffered saline pH 7·4 containing 0·005% Tween 20 (PBS-T) running buffer using a flow rate of 30 µl min−1 and 150 µl total reaction volume, respectively. A regeneration of the sensor surface was performed before each testing by injecting 0.85% phosphoric acid solution at 100 µl min−1 for 18 s.

LPS of Klebsiella was diluted in running buffer and different concentrations (10, 20, 40, 80 µM) were injected for 60 s association time corresponding to a total reaction volume of 100 µl at 100 µl min−1 followed by 600 s dissociation step using an equal flow rate via channels A1–A4 (horizontal channels). Interaction binding signal (RU) raw data of channels were referenced by subtraction of the unspecific binding signals on uncovered channel. Double reference was carried out by subsequent subtraction of unspecific binding signals measured in a reference channel with PBS-T. Data were analyzed with the computer software (ProteOn manager software, Bio-Rad). Kinetic constants were calculated using Langmuir model kinetic analysis of the ProteOn manager software (Bio-Rad).

2.4 NMR sample preparation

All samples were prepared by dissolving lyophilized HL in 0·3 ml H2O containing 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer and 10% D2O. Final concentrations of all samples were 0·5 mM protein as determined by measurement of the molar extinction coefficient, using E1% = 25·5 for HL. For mixtures of lysozyme with disaccharide 1, a 40 mM stock solution was prepared. The following samples were prepared: pure HL as well as 1:1 mixtures of these proteins with disaccharide1 at pH 3·8 and 5·5. Additional samples for HL were prepared in a similar manner for the pH titrations described below.

2.5 NMR measurements

All NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Unity INOVA 800 MHz spectrometer at 35 °C using 3 mm Shigemi tubes. The 1H chemical shifts were referenced to DSS. For disaccharide–lysozyme interaction measurements, equivalent amounts of disaccharide1 were added to the enzymes. Homonuclear 2D NOESY (mixing time 150 ms) and TOCSY (mixing time 50 ms) with spectral width 11 204 Hz for both dimensions were acquired with 512 increments in the indirect dimension and 4096 data points in the direct dimension, using Watergate solvent suppression and a pulse sequence repetition delay of 1·5 s. All data were processed with the NMRPipe software package (Delaglio et al. Reference Delaglio, Grzesiek, Vuister, Zhu, Pfeifer and Bax1995) by zero-filling to 1024 points in the indirect dimension and ending with either a Gaussian or a shifted sine-bell function. After zero-filling the digital resolution was 0·0015 ppm for the direct dimension and 0·014 ppm for the indirect dimension. For pKa determinations of HL, 10 NOESY spectra were recorded in the pH range 3·8–8·1 (3·8, 4·2, 4·6, 5·0, 5·5, 6·2, 6·8, 7·4, 7·7 and 8·1). A separate sample of HL was prepared for recording of 22 1D spectra covering the pH range of 3·17–8·13 in steps of ~0·2 units. All 1D datasets were defined by 4096 complex points and consisted of 256 transients. The digital resolution of the 1D spectra was 0·0024 ppm after zero-filling. Xeasy (Bartels et al. Reference Bartels, Xia, Billeter, Güntert and Wüthrich1995), Mnova (Claridge, Reference Claridge2009), and CCPNmr (Vranken et al. Reference Vranken, Boucher, Stevens, Fogh, Pajon, Llinas, Ulrich, Markley, Ionides and Laue2005) were used for analysis and resonance assignment. Line widths are defined as half-width at half-height of a peak; for most peaks the line width was estimated to be 0·01 ppm.

All pH adjustments were made by addition of small aliquots of either H3PO4 or NaOH. The pH meter was calibrated with standard solutions (from Sigma) at pH 4 and 7. The temperature dependence of the pH reading for HL was checked by recalibrating the pH meter at 35 °C: the difference between an incubated lysozyme sample at 35 °C and at room temperature was less than 0·1 pH unit. The pH for each sample was measured before and after each experiment to warrant constant conditions.

2.6 Signal assignments

1H resonance assignments at pH 3·8 and pH 5·5, both at 35 °C, were obtained for HL by transferring chemical shifts from the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB, http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/) (Ulrich et al. Reference Ulrich, Akutsu, Doreleijers, Harano, Ioannidis, Lin, Livny, Mading, Maziuk, Miller, Nakatani, Schulte, Tolmie, Wenger, Yao and Markley2008) entries 5130 and 1093, respectively, to the NOESY and TOCSY spectra. Based on chemical shift changes, conclusions about interactions between lysozymes and disaccharide 1 could be made in several cases as described in the main text. However, no intermolecular NOEs were detectable, suggesting dynamic binding modes only.

2.7 Molecular modeling and data mining

Docking studies were performed with the AutoDock 4·2 software, which uses the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) implemented therein. For the docking of the LPS disaccharide fragment 1 with human or chicken lysozyme, the required file for the ligand was created by combining the Gaussian and AutoDock 4·2 software packages. The grid size was set to 126, 126, and 126 Å along the X-, Y-, and Z-axis; in order to recognize the LPS glycan binding site of HL, the blind docking simulation was adopted. The docking parameters used were the following: LGA population size = 150; maximum number of energy evaluations = 250 000. The lowest binding energy conformer was taken from 10 different conformations for each docking simulation and the resultant minimum energy conformation was applied for further analysis. The MOLMOL (Koradi et al. Reference Koradi, Billeter and Wüthrich1996) and PyMOL (DeLano, Reference DeLano2002) software packages were applied for visualization and analysis of the docked complex. Data mining of protein–carbohydrate interactions in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) was performed with GlyVicinity at a redundancy level of 70% (www.glycosciences.de/tools/glyvicinity/). Only non-covalently bound ligands in structures with a resolution of at least 3 Å have been considered. The analysed dataset comprised 498 amino acids that have been found within a 4 Å radius of 73 alpha-galactose residues in 73 different PDB entries.

2.8 X-ray

For crystallization, the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method was performed in 24-well plates. Single crystals of the HL were obtained by mixture of 2 µl of the reservoir solution (0·8 M NaCl, 25 mM NaOAc, pH 4·4–5·6) with 2 µl of the protein solution (50 mg ml−1 in 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6·0). These drops were equilibrated against 1 ml of the reservoir solution at 291 K. For co-crystallization, the protein solution was mixed with a 10-fold excess of tetrasaccharide 2 and incubated for 30 min at room temperature prior to setting up the crystallization drop. Data collection for X-ray diffraction was performed at 100 K. The crystals were transferred into liquid nitrogen for flash-cooling without the prior addition of cryoprotectants. All data processing was performed using the XDS/XSCALE (Kabsch, Reference Kabsch2010) program package. Molecular replacement was carried out using the MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, Reference Vagin and Teplyakov1997) program with the HL structure (PDB id: 1REX) (Muraki et al. Reference Muraki, Harata, Sugita and Sato1996) as the search model. Model building and refinement were performed with the Refmac5 program as implemented in the CCP4 suite (Murshudov et al. Reference Murshudov, Skubák, Lebedev, Pannu, Steiner, Nicholls, Winn, Long and Vagin2011; Winn et al. Reference Winn, Ballard, Cowtan, Dodson, Emsley, Evans, Keegan, Krissinel, Leslie, McCoy, McNicholas, Murshudov, Pannu, Potterton, Powell, Read, Vagin and Wilson2011) and PHENIX (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Afonine, Bunkóczi, Chen, Davis, Echols, Headd, Hung, Kapral, Grosse-Kunstleve, McCoy, Moriarty, Oeffner, Read, Richardson, Richardson, Terwilliger and Zwart2010). The COOT (Emsley et al. Reference Emsley, Lohkamp, Scott and Cowtan2010) graphics program was used to interpret the electron density maps and to rebuild the structure.

3. Results

3.1 NMR observations of structural rearrangements of the binding site of HL

The lysozyme enzymatic reaction requires an initial protonated form of the highly conserved Glu35, which exhibits a high pKa of 6·8 (Kuramitsu et al. Reference Kuramitsu, Ikeda, Hamaguchi, Fujio, Amano, Shiro and Nishina1974). Two pH-based NMR titrations of lysozyme without (see below and Fig. 2) and with (see below and Fig. 3) the weakly binding disaccharide 1 were used to provide atomistic insights into the relationship between the (de)protonation of Glu35 and its associated structural rearrangements in the surrounding helices, which were suspected to control the continuation of the catalysis reaction and hence influence specificity.

Fig. 2. NMR-based investigation of free human lysozyme (a) 1D spectra of pure HL at various pH values (indicated on the left border). For clarity, we show the residues, indole ring proton of Trp (Trp109, Trp112, and Trp34) and the HN of Cys77 and Ala111 (shown in top two traces), which show strong chemical shift perturbation. (b) Selected 2D NOESY regions for HL at various pH values. Spectra for the different pH values are colored as follows: 3·8, red; 5·0, light blue; 5·5, green; 6·8, orange; 7·4, black; 7·7, purple; 8·1, dark blue. Chemical shifts that varied with pH are indicated by arrows on or beside the corresponding peaks with different colors. Peak contours are calibrated such that the intensities of the HN–HN cross-peaks for helix c are constant across all pH values. (c) Epitope mapping of HL from the pH titration, based on all resonances listed in the first part of online Table S1. Side chains are shown and labeled for Glu35, Asp53 and Trp109. Spheres are color-coded as follows: atoms on helix b are magenta, atoms on helix d are orange, and Trp109 side-chain atoms are blue (Hβ2, Hδ1 and Hɛ1). Additionally, black spheres mark the HN positions from the following residues: 58 and 59 (near D53), 100 (at the end of the red helix c), and HN 108 (before Trp109). The structure is rotated by 30° around a vertical axis with respect to Fig. 1 a; the helix coloring is the same, and helix a is presented as a thin violet curve for clarity.

Fig. 3. Interaction between human lysozyme and disaccharide 1, observed by NMR. (a) Selected regions from the 2D NOESY spectra of pure human lysozyme (red) and a 1:1 mixture with disaccharide 1 (black) demonstrate some of the shift changes observed after the addition of disaccharide 1. Peak labeling is as described in Fig. 2 b. (b) Mapping of resonances with chemical shift changes exceeding 0·07 ppm (online Table S1) after the addition of disaccharide 1 onto the 3D structure of lysozyme; the atoms are indicated as green spheres. The structure has an identical orientation and helix coloring to that described in Fig. 1 a.

The pH dependence of the lysozyme binding site modulations was analyzed for free lysozyme and lysozyme in the presence of the weakly binding disaccharide 1 (Fig. 1 d), and conclusions regarding the interactions between lysozyme and disaccharide 1 were made on the basis of chemical shift changes. However, intermolecular NOEs between these two molecules were undetectable, thus suggesting the existence of only dynamic binding modes for which no stable structure could be determined. The results were therefore compared with the stable complex of lysozyme with tetrasaccharide 2 (Fig. 1 d), which occupies four binding sites (A, B, C, and D) (Fig. 1 a).

3.2 NMR-based investigation of free human lysozyme

Titrations in the 3·8–8·5 pH range were observed for free HL by 1D and 2D NMR (online Table S1, Supplementary Information). Figure 2 a shows 1D spectra for different pH values, illustrating that the indole ring proton (Hε1) of residues Trp34, Trp109, Trp112, and the amide protons of Cys77 and Ala111 are strongly affected by pH. The most pronounced change was observed for Trp109, with a shift to lower field by 0·43 ppm, whereas Trp64 and the overlapping Trp28 (at 9·13 ppm, not shown) did not titrate in the 3·8–8·5 pH range. 2D NOESY spectra complemented the 1D titrations and provided a comprehensive picture of the chemical and structural changes in the enzyme (Fig. 2 b). Again, large changes were observed for the HN of Ala111 (around pH 6·8) and for various side-chain atoms of Trp109. Additional chemical shift perturbations were also observed in large portions of helices b and d (Fig. 1 a). The observed effects outside of these two helices included Gln58, Ile59, Val100 and Ala108 (online Table S1, Supplementary Information).

The strongest shift changes in the spatial neighborhood of the catalytic residue Glu35 were revealed by mapping of these shift changes onto the 3D structure of HL; they affect most of the b and d helices, and the loop between the second and third β-strands from the β-domain (Fig. 2 c). Changes involving the HNs of residues Gln58, Ile59, Val100 and Ala108, were located in the plane of the Trp109 ring, thus indicating rotation of this ring. The common pKa value (within the measurement error) of all these resonances, about pH 6·8, coincided with the reported (and unusually high) pKa value of the catalytic Glu35 protonation site (Kuramitsu et al. Reference Kuramitsu, Ikeda, Hamaguchi, Fujio, Amano, Shiro and Nishina1974); this strongly indicated that all of these events are coupled (online Table S1 and Fig. S2 and S3 Supplementary Information). The common pKa value (within the measurement error) of all these resonances, about pH 6·8, coincided with the reported (and unusually high) pKa value of the catalytic Glu35 protonation site (Kuramitsu et al. Reference Kuramitsu, Ikeda, Hamaguchi, Fujio, Amano, Shiro and Nishina1974), and furthermore identical pKa strongly indicated that all of these events are coupled (online Table S1, Supplementary Information). The large shift variation of ~0·84 ppm for the HN of Ala111 is probably the result of an adjacent charge change, and the obvious cause of this shift variation is the Glu35 side chain, whose carboxyl group is nearby at 3·4 Å (Harata et al. Reference Harata, Abe and Muraki1998). The remarkable behavior of the HN of Ala111 was an important observation that demonstrated a direct coupling between helices b and d. The next largest shift changes concerned the Trp109 side chain, which is an important component of the binding site surface and exhibited direct interactions with Glu35; the shortest distance between these side chains is 2·2 Å.

In addition to the well-known relative motions of the two domains required for ligand binding, HL undergoes a series of specific processes, both chemical and structural, when the pH is varied near 6·8. These processes include large parts of the α-domain with the catalytic Glu35, the side chain of Trp109, most of the b and d helices, and the loop between the second and third β-strands from the β-domain (Fig. 2 c). The identical pKa (within the measurement error) of all relevant resonances strongly indicated that all of these events are coupled (online Table S1, Supplementary Information). Although some strong interactions with Glu35 have been previously reported (Kuramitsu et al. Reference Kuramitsu, Ikeda, Hamaguchi, Fujio, Amano, Shiro and Nishina1974) (e.g. with Trp109) or can be assumed on the basis of their proximities (e.g. to the amide of Ala 111), other titrating residues appeared to be too far away from Glu35 to show direct effects due to the charge change upon (de)protonation; reports have instead focused on a higher flexibility of the α-domain that involves mutual rearrangements between helices b and d, which mirrors similar observations regarding factors such as ligand binding, temperature or pressure variations (Refaee et al. Reference Refaee, Tezuka, Akasaka and Williamson2003; Young et al. Reference Young, Tilton and Dewan1994). The relative position of helices b and d within the α-domain modulated by the hydrogen bonding network with Glu35, Trp109 and Ala111 is further defined by the previously described interaction between Arg115 and Trp34, and the Arg115Glu mutation has been reported to modify both the position of helix d and the enzyme activity (Harata et al. Reference Harata, Abe and Muraki1998). Thus, (de)protonation of Glu35 appears to trigger processes that spread over most of the α-domain.

3.3 Interaction between HL and disaccharide 1, observed by NMR

The binding sites of the c-type lysozyme include six individual subsites (labeled A–F, Fig. 1 a) for specific interactions with multiple saccharide rings (Chipman & Sharon, Reference Chipman and Sharon1969). Mixtures of HL and disaccharide 1 (Fig. 1 d) yield observable chemical shift value changes at only pH 5·5; effects caused by intermolecular interactions were undetectable at pH 3·8. At pH 5·5, the nuclei in the residues surrounding the D-F sub-sites that show changes were Glu35 HN and Hγ, Asn44 H, Trp109 Hδ1 and Hε1, and Arg113 HN (Fig. 3 a).

The affected residues were mapped onto the 3D structure of HL in Fig. 3 b and demonstrated transient binding at subsites D and E (Fig. 1 a). Helices b and d and the catalytic Glu35 in particular responded to the addition of disaccharide 1. Furthermore, a chemical shift change was observed on the β-domain in the center of the first strand (Asn44). Since Trp109 is part of the binding cleft (Fig. 1 a), it is unsurprising that the aforementioned structural changes mediated by this tryptophan were affected by ligand binding. The observations of chemical shift changes for Arg113, whose location was distal to all binding sites and buried behind the preceding helix loop (residues 110–111), were in agreement with a coupling between the ligand-binding and conformational effects.

3.4 Molecular modeling of the interaction between HL and disaccharide 1

Molecular modeling (Kar et al. Reference Kar, Gazova, Bednarikova, Mroue, Ghosh, Zhang, Ulicna, Sieber, Nifantiev and Bhunia2016; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Eckert, Lutteke, Hanstein, Scheidig, Bonvin, Nifantiev, Kozar, Schauer, Enani and Siebert2016) and data mining (Lütteke et al. Reference Lütteke, Frank and von der Lieth2005; Rojas-Macias & Lütteke, Reference Rojas-Macias and Lütteke2015) tools are necessary for general discussions of the principles of carbohydrate–protein interactions. In order to gain insight into the binding mode for disaccharide 1, molecular modeling is a rational tool to use. During the docking, each simulation includes 100 runs, which generate 100 conformers for the ligand. The top 10 conformers with low energy were selected for further analysis. For this step, both energy and ligand binding were considered. In fact, in the end, only the conformer with the lowest energy was selected for interaction description, which also shows a rational binding conformation. Figure 4 a displays the most favorable energetic structure of HL and disaccharide 1. A close-up view of the basic pocket with the LPS-interacting side chains is presented in Fig. 4 b. Red dashed lines indicate the hydrogen bonds. The simulation of the binding for disaccharide 1 indicated its interaction with HL at the substrate binding sites C and D. This observation is in agreement with the analysis based on the crystal structure of HL with the tetrasaccharide 2 since the binding sites C and especially D provided most of the interactions between sugar and protein. Comparisons of this specific result with similar cases in the PDB uncovered numerous meaningful agreements. The protein–carbohydrate interaction analysis in the PDB revealed that Trp, Tyr, Asp, Asn and His were the most overrepresented amino acids in the vicinity of α-D-Galp residues (Fig. 4 c). The previously described data mining approach (Bhunia et al. Reference Bhunia, Vivekanandan, Eckert, Burg-Roderfeld, Wechselberger, Romanuka, Bächle, Kornilov, von der Lieth, Jiménez-Barbero, Nifantiev, Schachner, Sewald, Lütteke, Gabius and Siebert2010; Lütteke et al. Reference Lütteke, Frank and von der Lieth2005) provided important information regarding the amino acid residues that typically occur in the vicinity of α-D-Galp. Using our data mining protocols, we performed an overview of the molecular interactions between α-D-Galp and the functional groups of certain amino acid residues (Fig. 4 c) in relation to the general structural aspects of lysozyme–carbohydrate interactions.

Fig. 4. Molecular modeling of the interaction between human lysozyme and disaccharide 1. (a) Molecular surface of lysozyme with carbons (green), oxygens (red), nitrogens (blue) and polar hydrogens (gray). (b) Close-up view of the basic pocket with disaccharide 1 shown in stick rendering and with hydrogen bonds indicated by red dashed lines. (c) Amino acid residues in the vicinity of α-Gal in the protein-carbohydrate complexes deposited in the PDB, which indicates the deviation from natural abundance. Trp, Tyr, Asp, and His are overrepresented by greater than 100% (i.e. they are observed twice as often or more in a 4 Å radius of α-Gal compared with an average protein).

Molecular modeling calculations with respect to the electrostatic surface potentials and hydrophobic patches were also performed (online Fig. S4). The differences in the patterns of the electrostatic surface potentials suggest variations in ligand binding and deviations in the aggregation/fibrillation behavior between human and avian lysozyme.

3.5 X-ray crystallography-based study of the interaction between HL and tetrasaccharide 2

To provide data that are independent of the results of the NMR measurements and molecular modeling calculations, X-ray crystallographic experiments were performed for human lysozyme. Extensive experiments to co-crystallize HL with bound disaccharide 1 (Fig. 1 d) at different pH values failed. We did not observe a convincing electron density for bound disaccharide, even after the crystals were soaked with high disaccharide concentrations. We assume that the disaccharide was too short to provide sufficient interaction opportunities with the protein to form a stable complex. Therefore, the study of a longer oligosaccharide ligand representing a larger polysaccharide fragment was initiated.

The crystal complex of HL with tetrasaccharide 2 was successfully obtained by co-crystallization of 1·9 mM HL in the presence of 20 mM tetrasaccharide 2. The X-ray diffraction resolution of the crystals was approximately 1·0 Å. A summary of the data collection and structure refinement is presented in Table 1. For details regarding the definitions of the individual parameters, see online Table S2 in the Supplementary Information.

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics

a Values in parentheses are for the high-resolution shell.

b For details regarding the definitions of the individual parameters, see online Table S2 in the Supplementary Information.

The refined structure of HL in complex with tetrasaccharide 2 reveals the binding of tetrasaccharide 2 near the A, B, C, and D substrate-binding sites of the enzyme (Fig. 5). The Galf–I furanoside unit of tetrasaccharide 2 is located near site A, and the Galp-II pyranoside unit is located near site B. The second repeating unit (Galf-III)-(Galp-IV) is in proximity to sites C and D. Both Galp units of tetrasaccharide 2 adopt a chair conformation. Overall, there are eight direct hydrogen bonds between tetrasaccharide 2 and the amino acid residues of HL. Seven residues (Ile59, Asn60, Tyr63, Trp64, Ala76, Asp102, and Trp109) form hydrophobic interactions. Through comparison with tetra N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, it is clear that the sugar ring systems of tetrasaccharide 2 are not identically positioned. However, a similar number of direct hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions and water-mediated bridged hydrogen bonds jointly contribute to the overall binding affinity.

Fig. 5. Molecular surface of HL in the complex with tetrasaccharide 2. (a) Representation of the molecular surface of HL is colored according to the electrostatic potential. Tetrasaccharide 2 is represented by sticks for one conformation (carbon atoms in cyan and oxygen atoms in red) and by black lines for an alternative conformation. The HL (PDB-entry 1LZR)-bound chitotetraose (GlcNAc)4 ligand is superimposed and represented by sticks (carbon atoms in yellow). (b) Close-up view of the superimposed ligands, tetrasaccharide 2 (carbon atoms in cyan) and (GlcNAc)4 (carbon atoms in yellow, oxygen atoms in red and nitrogen atoms in blue. (c) Representation in stereo of the electron density 2Fobs-1Fcalc omit map defining bound tetrasaccharide 2. The Galp-II, Galf-III and Galp-IV units are represented by sticks (carbon atoms in cyan and oxygen atoms in red). The protein backbone is indicated by a ribbon representation in green. The representation was generated using PyMOL v.1.6 (DeLano, Reference DeLano2002).

Based on number and ratio, an important contribution to the overall binding affinity for tetrasaccharide 2 seems to be provided by bridged hydrogen bonds that are mediated by approximately 20 water molecules within the binding pocket toward the following lysozyme residues: Glu35, Asp49, Asp53, Asn60, Tyr63, Val99, Arg98, Gly105, Ala108, Val110, and Ala111 (Fig. 6 and online Table S3, Supplementary Information). This ratio and mix of interactions is similar to those observed for (GlcNAc)4 (PDB entry 1LZR) and (GlcNAc)4/(GlcNAc)2 (PDB entry 1LZS) (Song et al. Reference Song, Inaka, Maenaka and Matsushima1994) bound to HL. The superposition of HL-2 with HL-(GlcNAc)4 and with HL-(GlcNAc)4/(GlcNAc)2 resulted in RMSD values of 0·23 and 0·46 Å, respectively (based on 130 C-alpha positions), thus indicating that the 3D structures of the protein-ligand complexes are similar in all three complexes.

Fig. 6. Binding site of human lysozyme with bound tetrasaccharide 2. The ligand is shown as a ball-and-stick representation; the bonds are indicated in purple. The protein residues are represented without side chains. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines, and the spoked arcs represent protein residues that form hydrophobic interactions with the ligand. The cyan spheres indicate water molecules, which provide bridged hydrogen bonds between the ligand atoms and amino acid residues. The individual interactions are provided in online Table S3 of the Supplementary Information. The representation was derived from an analysis with LigPlot+ (Laskowski & Swindells, Reference Laskowski and Swindells2011).

The binding modes of tetrasaccharides 2 and (GlcNAc)4 in the A, B, C, and D sites display small but significant differences. Specifically, Arg98 forms a direct hydrogen bond between its side-chain atom, Nɛ2, and the O1 atom of the Galf-I unit in site A of the HL-2 complex. Additionally, water molecules mediate a bridged hydrogen bond between the NH group of Arg98 and the OH group of Galf-I. Arg98 is not involved in the binding of (GlcNAc)4 or (GlcNAc)2 to HL.

The major interactions of the Galp-II unit in site B of HL are managed by direct hydrogen bonds with the surrounding amino acid residues Tyr63, Asp102, and Gln104. In addition to the hydrogen bond between atom O7 and the OH group of Tyr63, the aromatic plane of Tyr63 provides a strong hydrophobic interaction with the Galp-II moiety. A similar interaction of Tyr63 with the second GlcNAc residue is present within the HL-(GlcNAc)4 complex. Notably, the orientation of the Tyr63 side chain in the HL-2 complex is rotated by ca. 10° for an optimal interaction with the shifted sugar position in comparison with the GlcNAc unit. The Oδ2 side-chain atom of the Asp102 residue contributes two hydrogen bonds to the binding of the first two sugar units of 2, but only one direct hydrogen bond to the first GlcNAc unit is observed in (GlcNAc)4. In the HL-(GlcNAc)4/(GlcNAc)2 complex, atom Oδ1 forms two hydrogen bonds with atoms N and O6 of the first GlcNAc moiety of (GlcNAc)4/(GlcNAc)2. As a consequence of these differences, tetrasaccharide 2 adopts a closer binding orientation toward the ‘bottom’ of the binding pocket, as compared with (GlcNAc)4 and (GlcNAc)4/(GlcNAc)2.

The Galf-III unit is located near the C substrate-binding site. Only one direct hydrogen bond is formed between the Trp64 atom Nɛ1 and atom O19. Similar hydrogen bonds are contributed by these two residues for sugar binding in the HL complex to produce HL-(GlcNAc)4 and HL-(GlcNAc)4/(GlcNAc)2. The unit Galp-IV is located between the two substrate-binding sites, C and D. The only two direct hydrogen bonds are formed between atom O16 and the main-chain atom O of Gln58 and between atom O15 and the main-chain atom N of Asn60. Within the HL-(GlcNAc)4 complex, a similar hydrogen bond is contributed by Gln58 to the fourth GlcNAc moiety. Additionally, two residues, Asn46 and Asp53, form direct hydrogen bonds with GlcNAc atom O1 in the HL-(GlcNAc)4 complex. Interestingly, in the HL-(GlcNAc)4/(GlcNAc)2 complex, Gln58 is not involved in the interaction with the fourth GlcNAc moiety; instead, it is involved in the interaction with the Asn46 side chain and the main-chain atoms of Ala108 and Val110. Notably, approximately 10 water molecules play an important role in mediating interactions between unit Galp-IV of tetrasaccharide 2 and the Glu35, Asp49, Ser51, Asp53, Gln58, Gln104, Ala108, and Ala111 residues near the D and E substrate-binding sites. It is possible that a fifth sugar moiety may be adopted within this interaction network, which would contribute to a further gain in binding affinity.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to indicate that tetrasaccharide 2, which represents part of the O-chain of the K. pneumoniae O1 LPS, binds to HL at its conserved sites (A, B, C, and D) within the substrate binding pocket; this binding occurs mainly through direct hydrogen bonds and indirect hydrogen bonds that are mediated by water molecules. Our SPR experiments indicated a specific binding of LPS fragments to lysozyme, however with a rather low on-rate. A couple of synchronously occurring processes have to be considered for the evaluation of this slow on-rate: closing/opening of the binding cleft, rearrangement of side chains, water molecules have to be squeezed out of the binding cleft before the sugar molecule can bind and finally the sugar has to adopt an optimal conformation. In the case of dihydrofolate reductase the dynamic events during catalysis were deciphered e.g. by NMR experiments and helped to model the energy landscape (Boehr et al. Reference Boehr, McElheny, Dyson and Wright2006). We have performed a combination of molecular dynamic simulation, NMR-spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography to thoroughly characterize the ligand binding. Our NMR titrations provide a detailed picture of how the active site and the overall structure are related to each other. At pH 6·8, deprotonation of Glu35 occurs, which inactivates the enzyme at this unusually high pKa value, and helices b (with Glu35) and d undergo a substantial repositioning as indicated by the mapping of pH titration effects in Fig. 2 c. Because one of the first catalysis steps also involves the deprotonation of Glu35, these domain-wide structural changes are likely to modulate the continuation of the catalysis reaction. Together with earlier studies (Refaee et al. Reference Refaee, Tezuka, Akasaka and Williamson2003; Young et al. Reference Young, Tilton and Dewan1994), our data indicate a general flexibility and lower stability of helix d, which can be affected by numerous factors, including sugar binding and temperature changes. The ability of lysozyme to exhibit complex responses to environmental changes is evidenced by the following observations: the titration effects observed for the proton probes on Glu35, Trp109 and Ala111; the line broadening of local motions that involve Trp109 and Ala111; the spatial neighborhood of these three residues, which allows for direct interactions; and the wide range of titrating resonances on helices b and d. These structural rearrangements appear to be strongly coupled to enzyme activation by the (de)protonation of Glu35.

The carbohydrate binding site of HL displays a strong structural plasticity. This fact agrees with earlier observations by NMR relaxation studies, that the binding of carbohydrates to proteins is significantly determined by changes in conformational entropy (see for example Diehl et al. Reference Diehl, Engström, Delaine, Håkansson, Genheden, Modig, Leffler, Ryde, Nilsson and Akke2010). This may take various forms, for example of transient interactions such as water-bridged hydrogen bonds, or of changes in protein dynamics without observation of structural changes in crystal structures. Only a few amino acid residues are in direct hydrogen-bonding contact with the oligosaccharide chain. Most interactions are formed by hydrophobic contacts and particularly by water-mediated bridged hydrogen bonds. These latter two modes of interaction are less constraining and can be used to adopt binding environments for various ligands. The lectin-like ability of HL to interact with the O-chain of bacterial LPS highlights the strong possibility of a new role of HL in immune defense functions. This study may enable future developments of new and important therapeutic approaches to prevent and treat bacterial infections.

4.1 Speculation

The investigated lectin-like ability of HL to interact with the O-polysaccharide chain of bacterial LPS shows the possibility of an unknown glycan-guided mechanism of lysozyme's biological role. It underlies recognition of the bacterial cell wall by lysozyme and may complement its known immune defense functions. Further investigation of carbohydrate specificity of lysozyme with the use of larger linear and branched oligosaccharide ligands related to the O-chain of K. pneumoniae O1 as well as of antigenic polysaccharides of others bacterial pathogens may show the scope and limitations of the studied phenomenon.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033583517000075.

Acknowledgements

The Swedish NMR Centre is acknowledged for supplying instrument time and support. Diffraction data were collected on a P14 operated by EMBL at the PETRAIII storage ring (Hamburg, Germany). We are grateful to the beamline staff for providing assistance in using the beamline. We thank Dr Timothy Weaver (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, USA) for the provision of human recombinant lysozyme.

Financial support

This work was supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (grant KUK-11-008-23 awarded to B.N. with a Ph.D. position for L.W.) and the European Research Council (ERC-2008-AdG 227700 to B.N.). Beamtime on the P14 at the EMBL outstation in Hamburg was funded by a BioStruct-X grant. We thank the Sialic Acids Society for financial support. The synthetic portion of the work was supported by the RSF (grant 14-23-00199 to N.E.N.). A.D. would like to thank CSIR, Govt. of India for senior research fellowship.

Conflict of interest

None