According to the World Food Summit (1996) definition, ‘food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’. Food insecurity is defined as a lack of availability or access to food or a lack of capacity to utilise food to provide an adequate diet. Food insecurity has been linked to adverse health outcomes, such as cardiometabolic conditions(Reference Te Vazquez, Feng and Orr1) and diabetes(Reference Seligman, Bindman and Vittinghoff2), as well as higher mortality than in food-secure populations(Reference Men, Gundersen and Urquia3).

Food insecurity has been commonly researched by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in low- to middle-income countries, and food insecurity data in the USA have been published by the US Department of Agriculture since 1995. However, it is only within the past decade that rising food insecurity in Europe has gained more attention(Reference Gundersen4–Reference Campanera, Gasull and Gracia-Arnaiz7). Limited data are available in Finland. According to the FAO of the UN’s report, the prevalence of severe food insecurity in Finland was 2 %, while in 2017, the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity was 8·3 %(8). A Finnish study from 2001 of a nationally representative sample of 25–64-year-olds(Reference Sarlio-Lähteenkorva and Lahelma9) noted that 9 % reported fears of running out of food due to economic problems, 11 % had experiences of running out of money to buy food and 3 % had had too little food due to lack of money. In a previous study on a group of private sector service workers belonging to the Finnish Service Union United (PAM), 36 % of participants were severely food insecure, and 29 % were mildly or moderately food insecure(Reference Walsh, Nevalainen and Saari10). Furthermore, participants reported worse self-perceived health than the population average(Reference Erkkola, Walsh and Saari11). In Finland, the union membership rate in the private service sector was 48 % in 2017(Reference Ahtiainen12).

The negative associations between food insecurity and health have been hypothesised to not only be direct but also mediated by an unhealthy diet(Reference Hanson and Connor13), as it is an established risk factor for many chronic diseases(Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay14). Several studies in Western societies have linked food insecurity to overall lower diet quality and particularly lower consumption of fruits and vegetables(Reference Hanson and Connor13,Reference Lund, Holm and Tetens15–Reference Marshall, Laurence and Qian17) . Up to the last decade, most studies have been conducted in the USA(Reference Hanson and Connor13,Reference Leung and Tester18) , but reports from Europe have emerged in recent years(Reference Lund, Holm and Tetens15,Reference Bocquier, Vieux and Lioret16,Reference Keenan, Christiansen and Hardman19,Reference Shinwell, Bateson and Nettle20) . To date, only one study has been carried out in the Nordic countries(Reference Lund, Holm and Tetens15). In this Danish study, Lund et al. found that after adjustment for sociodemographic factors, adults from low or very low food-secure households had a higher probability of having an unhealthy diet, as measured by the Danish Dietary Quality Score, and food insecurity was associated with lower intakes of fruits, vegetables and fish. It is important to investigate these associations in Nordic welfare countries since dietary patterns, social safety nets, food availability and price policies, among others, differ from the USA and other European countries.

In high-income countries, diet quality tends to follow a socio-economic gradient where higher quality diets are associated with higher socio-economic status(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski21). According to a Finnish report, one of the socio-economic factors linked to low diet quality was occupational class; blue-collar workers had on average lower-quality diets than white-collar workers(Reference Prättälä, Linnanmäki and Vartiainen22). Thus, it is important to identify the most vulnerable groups for whom the dietary risk factors could accumulate. Evidence shows that people in lower socio-economic groups, including lower occupational class, are at higher risk of both lower diet quality and higher food insecurity(Reference Lund, Holm and Tetens15,Reference Darmon and Drewnowski21,Reference Holmes23–Reference Tarasuk, Fafard St-Germain and Mitchell25) . It remains unclear whether food insecurity exacerbates the poor diet quality observed in lower socio-economic groups such as Finnish private sector workers in low-salary positions.

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between food insecurity and diet quality in private sector service workers who were members of PAM and to analyse differences in consumption of selected food groups across the different levels of food insecurity.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data were collected via two online surveys in collaboration with Service Union United PAM, the trade union for private sector service workers. Most PAM members work in retail trade, tourism, restaurant and leisure services, property maintenance services (including cleaning) or security services. PAM has 190 000 members, 71 % of whom are women(26).

In April–May 2019, the PAMEL study survey was sent to all Finnish-speaking employed, unemployed and retired PAM members who had provided their email addresses in the PAM member register, excluding student members (n 111 850). The number of individuals receiving or reading the email is unknown. The study survey included questions on food consumption frequency, food insecurity and sociodemographic characteristics. Data on the employment industry were obtained from the annual PAM survey sent in May–June 2019.

Participants were asked for permission to link their survey answers to national register data provided by Statistics Finland for the years 2018–2019. Data obtained from Statistics Finland for 2019 included sex, year of birth, municipality type and individual income for 2018. Of the 6435 participants who answered the PAMEL study survey, national register data were available for 6431 members in 2018 and for 6421 members in 2019.

Measures

Food insecurity was measured with a slightly modified Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), originally developed by Coates et al. (Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky27). Although other food insecurity questionnaires are available (e.g. Food Insecurity Experience Scale by the FAO of the UN)(28), we chose to use the modified HFIAS because it was previously validated in the same study population(Reference Walsh, Nevalainen and Saari10). The tool was translated into Finnish and modified to inquire about an individual’s food insecurity experience rather than the entire household’s, as described in Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Nevalainen and Saari10).

The HFIAS questionnaire includes nine questions on how often participants have experienced issues related to worry about having enough food or having to limit the food quality or quantity for financial reasons during the past 30 d. Based on their responses, participants were categorised as food secure or mildly, moderately or severely food insecure(Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky27). In the previous study among the same sample of service workers, the HFIAS tool demonstrated acceptable construct and criterion validity(Reference Erkkola, Walsh and Saari11).

Food consumption was measured with an FFQ inquiring about the frequency of consumption of different food items over the last month. The FFQ was designed to measure the whole diet of participants and was based on an FFQ that has previously shown acceptable validity when ranking food group consumption compared with food records in Finnish children(Reference Korkalo, Vepsäläinen and Ray29). The FFQ was modified for adults: Some food items were combined into broader food groups (cheese instead of low-fat and high-fat cheese, yogurt instead of natural and flavoured yogurt, breakfast cereals instead of sugar-sweetened breakfast cereals and whole-grain breakfast cereals, sweet pastry instead of biscuits and cakes), and some food items were added (oils, margarines, oil-based salad dressings, coffee, tea, bottled water, wine, beer, cider, alcohol-free beer and cider and spirits), and finally, dried fruits and berries and flavoured nuts were removed. Because of these changes, the number of food items in the final modified FFQ was fifty-two food items (instead of forty-seven in the original). The FFQ was modified to concern the previous month instead of the previous week as in the original FFQ, with the seven response options ranging accordingly from ‘not at all’ to ‘more than once a day’. The frequency options were converted to weekly values as follows (converted values in parentheses): not at all (0 times per week), less than once a month (0·12 times per week), 1–3 d per month (0·47 times per week), 1–2 d per week (1·5 times per week), 3–5 d per week (4 times per week), daily or almost daily (6 times per week) and more than once a day (8 times per week). Portion sizes were not included in the form.

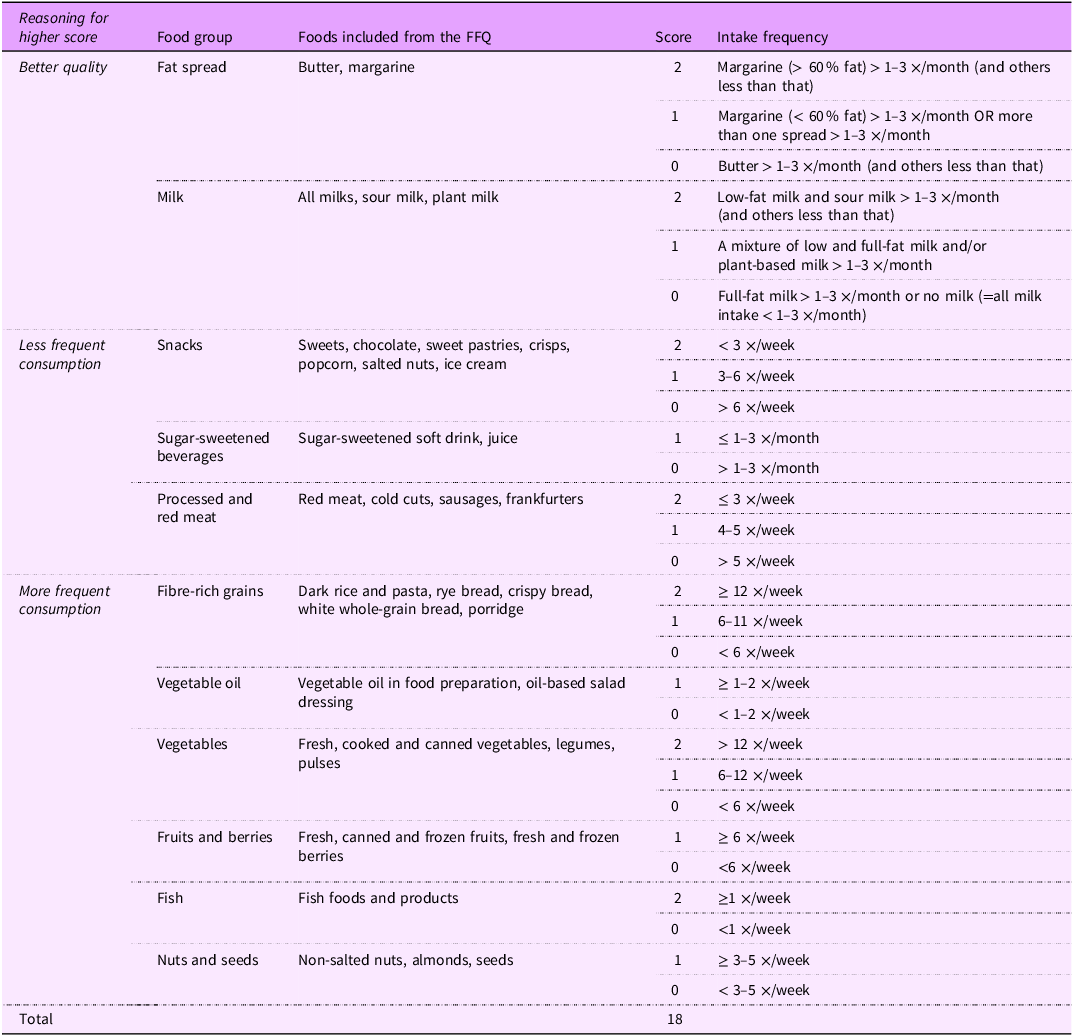

Diet quality was measured with a modified version of the Healthy Food Intake Index (HFII), developed and validated by Meinilä et al. (Reference Meinilä, Valkama and Koivusalo30). The HFII components reflect the food-based dietary guidelines of the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations(Reference Blomhoff, Andersen and Arnesen31). In a validation study, higher HFII scores reflected nutrient intake closer to the recommendations, and scores were higher in those who had higher educational attainment, were more physically active, had lower BMI or were non-smokers(Reference Meinilä, Valkama and Koivusalo30). Detailed FFQ data allowed us to incorporate processed and red meat as well as nuts and seeds in the original HFII to create a modified HFII (mHFII). Certain cut-off points had to be altered since our FFQ response options differed from the original.

A detailed description of the foods included in the different food groups of the index and the frequency cut-off points can be found in Table 1. In brief, items of fast food and low-fat cheese were removed as those were not included in the FFQ, and red and processed meat and nuts and seeds were added because the Finnish and Nordic Nutrition Recommendations include a recommendation for both food groups(Reference Blomhoff, Andersen and Arnesen31,32) . The modified index comprised eleven food groups for which points between 0 and 2 or between 0 and 1 were awarded based on the frequency of consumption and weighting. The maximum score was higher (2 points v. 1 point) for food groups considered to have relatively more importance in the Finnish diet. The total index score ranged from 0 to 18, with a higher score indicating more optimal consumption.

Table 1. Description of modified healthy food intake index (mHFII)

Statistical analyses

The normality of the variables was assessed through visual inspection separately in each HFII and food insecurity category. The association between food insecurity levels and modified mHFII score was first tested with one-way ANOVA, followed by estimation of pairwise differences to the reference level (food secure). Associations between sociodemographic variables and food insecurity were described by Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Nevalainen and Saari10).

Multi-way ANOVA was then used to refine the estimates after adjustment for confounding variables. The confounding variables were identified using a combination of hypothesis-driven and data-driven methods. First, potential confounders were identified from previous studies(Reference Jonker-Hoffrén, Müller, Vandaele and Waddington33–Reference Valsta, Tapanainen and Kortetmäki36). These comprised age, sex, highest education, marital status, household size, number of children in the household, housing type (e.g. owner-occupied housing, rented municipal housing), municipality type (urban, semi-rural, rural), employment status and income.

Second, key confounders were defined as those significantly associated with both food insecurity and mHFII score, influencing the estimates of food insecurity levels, and doing so persistently and with little correlation with the other key confounders. Following these criteria, key confounders in the multi-way ANOVA model were age, sex and highest education. The associations of these variables and the mean of the mHFII scores were tested with one-way ANOVA.

Furthermore, the associations between food insecurity and individual food group scores were examined with ordinal regression analysis using a proportional odds model. Because our analyses revealed that mHFII scores differed significantly only between those who experienced severe food insecurity and those who were food secure, we compared only these two groups. Analyses were conducted for each of the eleven food groups, where the outcome variable was the food group score (either two or three score categories), and the explanatory variable was food insecurity level (severe food insecurity/food secure). The ordinal regression models were adjusted for the key confounders.

Missing data were excluded from the analyses. The level of statistical significance used was set at 0·05. To control multiplicity, pairwise comparisons were Bonferroni-corrected. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package, version 27 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

Participants

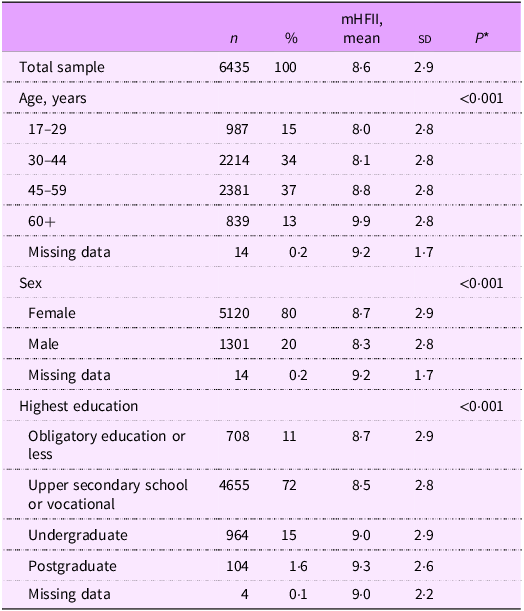

Sample characteristics and the associations of sociodemographic variables with mHFII score are presented in Table 2. Most of the participants were women (80 %), and the largest age groups were 30–44-year-olds (34 %) and 45–59-year-olds (37 %). Most (72 %) of the participants reported their highest education as upper secondary school or vocational education.

Table 2. Sample characteristics and associations of sociodemographic variables with the mean of the modified healthy food intake index (mHFII) scores, in Finnish private sector service workers (n 6435) in 2019

* One-way ANOVA.

Mean mHFII was consistently higher in older age groups; the oldest age group had the highest mHFII score, with a score of 1·9 points higher than the youngest age group. Females had a 0·4-point higher score than males. Participants with postgraduate level education had the highest score, with a 0·8-point difference from the group with the lowest score, which was the participants with upper secondary or vocational education. There were no differences in HFII between different job industry sectors (retail, hospitality, property maintenance and others; data not shown).

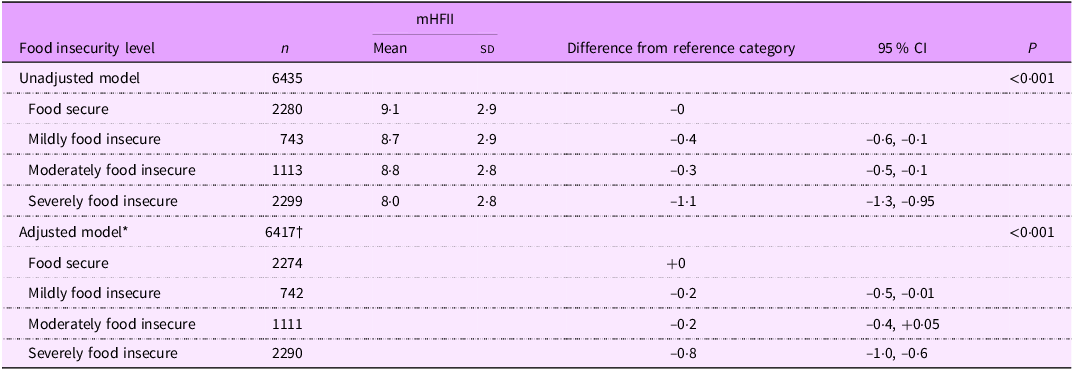

Diet quality and food insecurity

In the unadjusted model, diet quality, as measured by mean mHFII scores, was significantly lower in all three levels of food insecurity than in the food-secure level, and this difference was the most prominent among those with severe food insecurity (Table 3). The severe food insecurity level had a 1·1 (95 % CI –1·3, –0·95) point lower mean mHFII score than the food-secure level. Differences between mild and moderate food insecurity levels were approximately one-third of this difference.

Table 3. Mean difference in diet quality measured by modified healthy food intake index (mHFII) at different food insecurity levels, with food-secure participants as a reference group, in Finnish private sector service workers (n 6435) in 2019

* Adjusted for age, sex and highest education.

† Data on age, sex and/or highest education missing for eighteen participants.

After adjusting for age, sex and education level, differences in diet quality remained significant only between severe food insecurity and food-secure levels. The mHFII score was on average 0·8 points (95 % CI –1·0, –0·6) lower in the severely food-insecure group than in the food-secure group.

Food groups and food insecurity

Compared with food-secure participants, those with severe food insecurity had nearly twofold lower odds for high vegetable scores (Fig. 1 and online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). The odds were lower also for scores in sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), fibre-rich grains, fruits and berries, vegetable oil, fish, nuts and seeds and milk, both before and after adjustment for sociodemographic factors. On the contrary, compared with food-secure participants, those with severe food insecurity had 1·15-fold odds of having a higher (more optimal) score in red and processed meat. The odds did not differ between the food security levels in the scores for fat spreads and snacks.

Figure 1. Adjusted likelihood of severely food-insecure participants achieving higher food group scores relative to food-secure participants (represented by a score of 1·0 on the scale) in Finnish private sector service workers (n 4564–4579) in 2019.

Discussion

Our main finding was that severe food insecurity was associated with overall lower diet quality than in those without food insecurity. More specifically, severe food insecurity was linked to less frequent consumption of vegetables, fruits and berries, fibre-rich grains, fish, vegetable oil and nuts and seeds and more frequent consumption of SSB. Since lower consumption of these food groups (apart from SSB) is all linked to various adverse health outcomes(Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay14), participants who experienced severe food insecurity may be predisposed to cumulation of risk factors for chronic diseases over time.

Our findings are mainly in line with studies from other countries that suggest lower diet quality in individuals who experience food insecurity in terms of both overall diet(Reference Hanson and Connor13,Reference Lund, Holm and Tetens15–Reference Keenan, Christiansen and Hardman19) and individual food groups(Reference Hanson and Connor13,Reference Lund, Holm and Tetens15–Reference Marshall, Laurence and Qian17) . Regarding consumption of individual food groups, Lund et al. (Reference Lund, Holm and Tetens15) found similar results to ours among Danish adults (n 1877); food insecurity was associated with a lower intake of fruits, vegetables and fish, which were also the food groups in which we found the largest differences between severely food-insecure and food-secure participants. This could be because of the preference for ‘cheap energy’ as discussed later.

Interestingly, severe food insecurity was associated with less frequent consumption of red and processed meat than in the food-secure group. As limiting the consumption of red and processed meat is recommended(Reference Blomhoff, Andersen and Arnesen31), in this regard, the diet of the food-insecure group could be viewed as healthier. Alternatively, the finding could be an indication of low energy intake, which we cannot rule out because we did not measure energy intake. A small number of studies in high-income countries have not found an association between food insecurity and energy intake(Reference Bocquier, Vieux and Lioret16,Reference Shinwell, Bateson and Nettle20,Reference Zizza, Duffy and Gerrior37) . We also do not know whether red and processed meat were replaced with less nutritious food items, in which case the infrequent intake would not indicate a healthier diet. Consequently, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the healthiness of the less frequent use of red and processed meat by the severely food-insecure participants. Nevertheless, one reason for less frequent consumption of red and processed meat could be the high price of some red meat products(Reference Maillot, Darmon and Darmon38,Reference Drewnowski, Darmon and Briend39) although the variation in the prices of red meat products is large(Reference Fogelholm, Vepsäläinen and Meinilä40). Previous studies suggest that meat is also an established part of low-income households’ diets(Reference Wiig and Smith41,Reference Inglis, Ball and Crawford42) and that its consumption has not been associated with income(Reference Fogelholm, Vepsäläinen and Meinilä40,Reference Inglis, Ball and Crawford42) . However, the participants in those studies were not identified as food insecure and therefore may have still had more financial flexibility to make food choices based on preference – something that may not be possible for individuals experiencing food insecurity. A somewhat similar result to our high consumption of SSB by food-insecure individuals is that of a French study of a nationally representative population (n 2624)(Reference Bocquier, Vieux and Lioret16). The researchers found that consumption of soft drinks was high in both those with food insecurity and those with the lowest income without food insecurity, compared with subjects with a higher income. An American study on dental students (n 286) also found higher sugar intake from SSB among those experiencing food insecurity than among food-secure individuals(Reference Marshall, Laurence and Qian17). Although the criteria for high consumption differed between the French and American studies and our study, the direction of the association was similar.

It should be noted that to be categorised as severely food insecure in our study required skipping meals several times and/or going a whole day without eating at least once during the past month. Hence, it is logical that the consumption frequency is lower in many food categories, as severely food-insecure participants, by definition, ate less frequently than food-secure participants. It could, however, be speculated that people with severe food insecurity prefer cheaper sources of energy, such as refined grains and sugary drinks, instead of the foods they consume less frequently, including fruits, vegetables and fish. Earlier studies have demonstrated that foods of lower nutritional value, and lower-quality diets in general, cost less per calorie and tend to be favoured by groups of lower socio-economic status(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski43). In a Belgian study, consumers who spent less money on food were more likely to fail to meet healthy dietary guidelines(Reference Vandevijvere, Seck and Pedroni44). Food insecurity has also been linked to overweight and obesity, and a previous study suggested that obesity was a mediator between food insecurity and cardiometabolic diseases(Reference Te Vazquez, Feng and Orr1).

The results of this study must be interpreted with certain limitations in mind. First, due to the cross-sectional study design, conclusions on causality cannot be made. We do not know the duration of food insecurity or possible changes in the diet, as the measures only consider the past month. The main limitations of food consumption assessment were the self-reporting of consumption frequency, with no measurement of portion sizes or energy intake. Those who experience food insecurity tend to consume smaller portion sizes(Reference Usfar, Fahmida and Februhartanty45), but we did not consider this. In addition, we were unable to adjust the analysis for energy intake, which is a potential confounder. However, in the validation study of the HFII, the correlation coefficients between the HFII scores and nutrient intakes measured with food records did not change substantially when adjusted for energy intake(Reference Meinilä, Valkama and Koivusalo30). In addition, as is common in health research, the participants, on average, had a higher socio-economic status than typical private sector service workers, suggesting that the results may not be generalisable to all private sector service workers.

One notable strength of the study was that the HFIAS tool for measuring food insecurity is validated in this population(Reference Walsh, Nevalainen and Saari10). The measures for food intake and diet quality were not validated in this population, but the original FFQ has previously been validated in Finnish children(Reference Korkalo, Vepsäläinen and Ray29) and the original HFII in pregnant Finnish women(Reference Meinilä, Valkama and Koivusalo30). Our HFII modifications included the important food group of red and processed meat, as well as nuts and seeds, thereby improving the HFII to better reflect current dietary recommendations. Also, the FFQ allowed us to examine food intake over a longer time period than, for example, food diaries or 24 h recalls, which only consider short periods.

Another strength is that we were able to investigate a typically hard-to-reach population – low-paid private sector service workers – who are usually underrepresented in studies. The representativeness of the current sample of the low-salary private sector worker population is described in more detail in Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Nevalainen and Saari10), but it can be concluded that despite some limitations we were able to capture Finnish-speaking private service sector union non-student members reasonably well. However, because our research only focused on members of PAM, individuals from some of the most vulnerable groups who are less frequently members of trade unions are probably underrepresented, namely, young people, men, unemployed and those in part-time or fixed-term contracts(Reference Jonker-Hoffrén, Müller, Vandaele and Waddington33). In addition, because the questionnaires were not translated into other languages, the study population may have consisted of lesser diversity due to the high likelihood of missing non-Finnish-speaking members. According to PAM’s own data, 6·2 % of its members have foreign background(26). Immigrant background has been identified as a risk factor for food insecurity(Reference Maynard, Dean and Rodriguez46), and ethnicity has been found to moderate the association between food insecurity and diet quality(Reference Leung and Tester18). Therefore, more inclusive data collection methods should be considered in the future.

Low intake of healthy foods, such as fruits, vegetables and fish, is more common in socio-economically disadvantaged groups(Reference Valsta, Tapanainen and Kortetmäki36). Our findings suggest an even more concerning situation: clustering of suboptimal consumption across various food groups among those experiencing severe food insecurity. Our findings highlight the urgency of implementing effective actions to ensure equal access to a healthy diet. Potential actions include reforms in food taxation and the availability of affordable, nutritious meals in workplace restaurants. However, the primary focus should be on decreasing poverty among workers through sufficient salaries, fair employment contracts and robust social security to prevent food insecurity(Reference Walsh, Nevalainen and Saari10).

Food insecurity is a relevant issue also due to elevated food costs. The cost of food in Finland increased by 16 % in March 2023 from March 2022(47). It is reasonable to assume that rising costs will further drive people towards food insecurity and worsen the situation for those already affected, as could be the case for 65 % of the PAM members in the present sample. Our results suggest that private sector service workers are at increased risk of non-communicable diseases not only because of more prevalent food insecurity but also because of lower diet quality(Reference Seligman, Bindman and Vittinghoff2). In addition, food insecurity and poor diet quality are associated with worse work ability and more frequent health care utilisation(Reference Penttinen, Virtanen and Laaksonen48–Reference Virtanen, Penttinen and Laaksonen50). More research is warranted on the long-term implications and interconnections between food insecurity, diet quality, health and the societal impacts these may have.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980024002386.

Acknowledgements

We thank the PAM for collaboration and PAM members who completed the questionnaires used in the study. We thank our author-editor Carol Ann Pelli for excellent work on the manuscript.

Authorship

JN, TS, OR, HMW and ME were responsible for study conception and funding acquisition; JN, ME, RJ, HMW and JM designed the work; HMW, JN, TS and ME were responsible for the acquisition of data; RJ, HMW, JM, EL and JN designed the analysis; HMW, RJ and EL carried out the analyses; HMW, RJ and JM drafted the manuscript; all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was funded by the Finnish Work Environment Fund (M.E., grant no. 210173), the PAM and the Finnish Cultural Foundation (H.M.W., grant no. 00221125). Open access was funded by the Helsinki University Library. The funders had no role in the study design, analysis or writing of this article.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.