Self-harm is a priority area for suicide prevention and patient safety internationally.Reference Turecki, Brent, Gunnell, O'Connor, Oquendo and Pirkis1,Reference Rheinberger, Wang, McGillivray, Shand, Torok and Maple2 Consistent with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), self-harm in this study is defined as any intentional self-poisoning or injury, irrespective of motive or suicidal intent.3 Annually, at least 200 000 episodes of self-harm are treated in hospital emergency departments in England.Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters and Ness4 Around a tenth of patients harm themselves again within 5 days of the initial episode,Reference Kapur, Cooper and King-Hele5 and the risk of suicide is markedly elevated immediately after hospital presentation following self-harm.Reference Geulayov, Casey and McDonald6 Any intervention for patients who have self-harmed should therefore happen quickly to reduce the markedly elevated risk of further episodes and of fatality.3,Reference Kapur, Cooper and King-Hele5

Motivations for self-harm and suicidal intent can fluctuate, change over time, and vary within and between episodes.Reference Kapur, Cooper, O'Connor and Hawton7 Irrespective of suicidal intent, self-harm acts as an important risk factor for adverse events, including suicide.Reference Kapur, Cooper, O'Connor and Hawton7,Reference Mars, Heron, Crane, Hawton, Lewis and Macleod8 Psychological therapies after a self-harm episode represent an important opportunity to help patients and prevent repetition and suicide.3 However, there are few services dedicated to this group in the UK and other countries.3,Reference Hawton, Witt, Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell9,Reference House and Owens10

Several studies have investigated patient experiences of healthcare services following self-harmReference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11–15 and/or access to psychological therapies generally.Reference Punton, Dodd and McNeill16–18 However, few have specifically focused on access to psychological therapies following self-harm. One voluntary sector report on aftercare following self-harm described negative experiences of healthcare services (e.g. not taken seriously, exclusion).15 Although unmet needs for talking therapies and good quality aftercare are indicated, we know little about the consequences of these experiences for patients or about strategies to improve services from the perspective of people who have self-harmed. We previously investigated aftercare following self-harm from the perspective of liaison psychiatry practitioners referring patients into services. Staff reported concern over the harmful impact of limited aftercare services and long waiting times on patients.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Marks, Monaghan, Asmal and Webb19

Understanding patient views on barriers and enablers to accessing psychological therapies following self-harm is essential for facilitating implementation of clinical guidelines into practice and making services safer for patients. Therefore, we conducted a co-designed qualitative survey to investigate access to psychological therapies from the perspectives of patients and carers (as proxy respondents for patients). Our specific aims were to explore (a) subjective experiences of accessing psychological therapies and (b) patients’ views on improving access to psychological therapies for patients who have self-harmed.

Method

Ethics statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were reviewed and approved by Greater Manchester Central Research Ethics Committee (REC no: 18/NW/0839) prior to commencement of the study.

Consent statement

Written consent was obtained from all participants. This confirms that any participant has consented to the inclusion of material pertaining to themselves, that they acknowledge that they cannot be identified via the manuscript, and that the participant has been fully anonymised by the authors.

Design and sample

This study is part of a larger programme of work on psychosocial assessments and psychological therapies following self-harm. Our qualitative survey methods have been reported previously.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11,Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood12 In brief, we conducted a co-designed qualitative online survey18 of people with experience of self-harm and accessing psychological therapies. The use of an online patient/carer survey provided greater anonymity and control to the participants when sharing their experiences.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11,Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood12,18 Survey questions (Supplementary Appendix A) were co-developed with our patient and carer involvement panel and included open, closed and free-text options without word limits. Further details on question development are presented in Supplementary Appendix B and our previous publications.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11,Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood12

Recruitment

Patients and carers (as proxy respondents for patients) aged 18 or over with any experience of harming themselves (defined as intentional self-poisoning or self-injury irrespective of motivation or suicidal intent)3 and of accessing psychological therapies and/or psychosocial assessments were eligible to participate in a national online survey. We recruited participants through 16 mental health National Health Service (NHS) trusts around England, as well as social media, community organisations (e.g. charities, patient groups) and newsletters, from April to November 2019. Additional methodological information is presented in Supplementary Appendix B.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11,Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood12

Analysis

Thematic analysis, within a qualitative paradigm (as opposed to a post-positivist paradigm) was used to explore patterns, shared meaning, similarities and differences across the study data-set.Reference Braun and Clarke20–Reference Braun and Clarke24 Thematic analysis was used instead of other methods (e.g. content analysis)Reference Wilkinson25 because we wanted to explore subjective experiences of accessing psychological therapies following an episode of self-harm. We addressed our research questions from a qualitative critical realist theoretical position,Reference Clarke, Braun, Hayfield and Smith21 which considers meaning and experience as subjective realities for participants and our active role in conducting the analyses.Reference Clarke, Braun, Hayfield and Smith21,Reference Braun and Clarke23 Coding and themes were generated through our reflexive and active engagement with the data. People with lived experience, clinicians, and experts in health services and qualitative research were involved throughout the study to bring their perspective, views and experiences to the analyses.

Consistent with the approach developed by Braun and Clarke,Reference Braun and Clarke20 after immersion and familiarisation with the data, we coded the data systematically and iteratively at a predominantly semantic level. Two authors (L.G. and L.Q.) independently and systematically coded the full data-set. Six members of our patient and public involvement (PPI) panel, which included individuals with lived experience in this area, coded sections of the data (the data-set was split across members to minimise the burden). Throughout the process, codes and themes were iteratively generated, revised, reviewed and named via discussion within the team (L.Q., L.G., S.M., E.M., S.A., R.T.W. and N.K.). This team facilitated discussion and reflection around the process of accessing psychological therapies following self-harm, which enriched our interpretation of the data. The final themes, thematic structure and write-up (report) were agreed through discussion among team members. Themes addressed important aspects of the data in relation to our research question. We did not generate descriptive statistics for themes (e.g. use of counts or percentage values). This approach would have been inconsistent with our methodological approach and may have undermined the importance of some subjective experiences.Reference Clarke, Braun, Hayfield and Smith21,Reference Braun and Clarke23

SPSS version 22 was used for generating demographic descriptive statistics.26 NVivo 12 software was used for data management.27 Additional methodological details, including author details, and the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research FrameworkReference O'Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed and Cook28 are included in the Supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.27.

PPI panel

Our patient and carer advisory panel was involved in all aspects of the research process, including setting research questions, design, conduct, reporting and dissemination plans. The PPI panel collaboratively developed the initial research and survey questions, analysed the data, reviewed the results and contributed to interpretation and are co-authors. This research was also reviewed by a team with experience of mental health problems and their carers who had been specially trained to advise on research proposals and documentation through the Feasibility and Acceptability Support Team for Researchers (FAST-R), a free, confidential service in England provided by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at King's College London and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. There was PPI input into our dissemination plan, which includes communicating key findings to relevant patient groups, carers and mental health services.

Results

For the online survey, 151 participants provided text responses on access to psychological therapies following self-harm. Most participants were patients (128/151, 84.8%), and the remainder were carers (23/151, 15.2%). Patients were aged between 18 and 75 years, and their median age was 32 (interquartile range (IQR): 26–45). Carers were aged between 52 and 73 years, with a median age of 50 (IQR: 38–59). Most patient respondents (106/128, 82.8%) identified as women and White British (121/127, 95%), 18 (14.1%) participants identifed as men, and four (3.1%) as other (non-binary/gender-queer). Most carer respondents (20/23, 87%) identifed as women and White British (21/23, 95%). Additional sociodemographic information about participants is provided in the Supplementary Appendix B.

Qualitative results

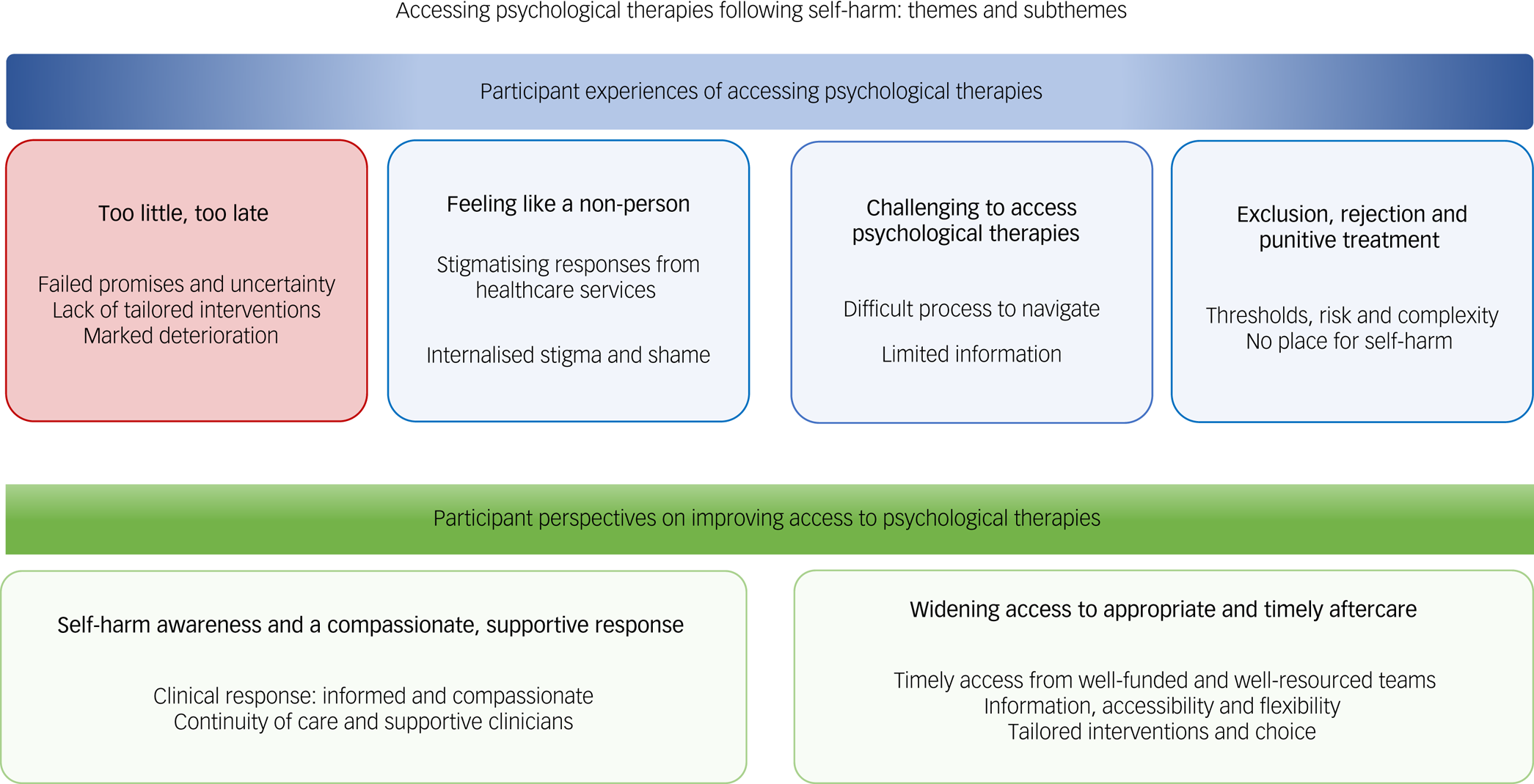

Themes and subthemes are presented in Fig. 1. We generated and grouped themes into two sections. The first section presents patient experiences of accessing psychological therapies following self-harm, and the second explores patient perspectives on improving access to aftercare following self-harm. The first four themes (‘Too little, too late’; ‘Feeling like a non-person’; ‘Challenging to access psychological therapies’; and ‘Exclusion, rejection, and punitive treatment’) report participants’ experiences of accessing psychological therapies following self-harm. Participants’ views and strategies for improving access to aftercare are reported in the second section and include ‘Self-harm awareness and a compassionate, supportive response’ and ‘Widening access to appropriate and timely aftercare’. Tabulated summaries are provided after each section (Figs 2 and 3). Additional supporting quotations are tabulated in Supplementary Appendix C.

Fig. 1 Themes and subthemes generated from the data.

Fig. 2 Participants’ views on barriers to psychological therapies (summary).

Fig. 3 Participants’ views on improving access to psychological therapies for self-harm (summary).

Themes

Section 1: experiences of accessing psychological therapies following self-harm

Theme 1: ‘Too little too, too late’

Limited availability of tailored interventions for people who self-harm, barriers to accessing help and long waiting times negatively affected many participants’ safety and well-being.

Initial assessments and referrals to psychological therapies were typically followed by long waiting times, rejection by healthcare services and further unsuccessful referrals. Poor communication from healthcare services contributed to participants’ uncertainty over already long waiting times and feelings of exclusion. After reaching out and struggling to access help, participants reported that their mental health worsened in the absence of timely intervention.

‘It's stressful, you have a positive meeting about this therapy that's meant to help then you get left waiting for months with no contact or updates’ (R43, female, patient, aged 18–25).

‘Significantly [impact of waiting times on mental health]. I feel like no one cared if I lived or died. I opened up and was really honest and I was left to rot’ (R149, female, patient, age 50).

‘Felt like I was worthless, more so than I already felt’ (R118, male, patient, aged 40–59).

Participants reported a lack of appropriate psychological therapies for people who have self-harmed. Existing treatments were reported as being insufficient for self-harm and/or ongoing support needs, which resulted in participants feeling unsuccessful in recovering from their distress. The dearth of psychological therapies was mostly attributed to underfunding of healthcare services and lack of resources.

‘It's [talking treatments] just not available to people’ (R39, female, patient, aged 26–35).

‘Six sessions of CBT [cognitive behavioural therapy] isn't going to do it, and would make me feel I'd failed’ (R30, female, patient, aged 60+).

The impact of excessive waiting times on participants was stark. One mother talked about the profound impact of waiting for psychological therapies on her daughter, who only received psychological assessments just before she died by suicide.

‘Terribly [impact of waiting times]. My daughter did not receive psychological support according to national guidelines. After waiting four months for first appointment, she only received two further appointment before her death. Too little, too late’ (R44, female, carer, aged 40–59).

Opportunities to intervene over self-harm for some people were missed, while others lost the ability to work, their quality of life, and hope. Significant distress over waiting times exacerbated strong negative feelings towards the self (mental pain). Participants reported feeling hopeless, anxious, worthless, abandoned, scared, and undeserving of help: ‘I gave up hope’ (R151, female, patient, age 40–59). Participants commonly reported further harming themselves again during the waiting period for psychological therapies, and some reported heightened suicidal thinking. Other participants lost trust in mental health services and/or were reluctant to seek help for self-harm: ‘I have lost the ability to trust anyone enough to talk about how I actually feel’ (R31, female, patient, aged 40–59).

‘My mental health deteriorated, my quality of life and functioning was impaired, I was unable to work or study, my self-care deteriorated, my self-injury became more severe, I experienced a severe relapse of anorexia nervosa, and I eventually attempted suicide. I was then put in hospital as an involuntary patient’ (R71, female, patient, aged 26–35).

Theme 2: ‘Feeling like a non-person’

The overarching participant experience for this theme was the stigmatising response of healthcare services when seeking help following self-harm. These responses, in addition to personal feelings of shame over self-harm, became internalised for participants and acted as a barrier to further help-seeking. Participants felt worthless, experienced further shame and felt that they were a ‘non-person’ undeserving of help.

Stigma and misunderstanding from some healthcare providers were identified as barriers to accessing help for self-harm. Participants felt that they were not taken seriously and that their distress was trivialised by some healthcare professionals. Individuals received judgemental responses when attending mental health services, which resulted in fear, apprehension and anxiety when subsequently asking for help or seeking psychological therapies.

‘I had to talk to four separate professionals before they helped me. They ignored me saying it was silly and trivial’ (R06, female, patient, 18–25).

‘Fear of judgement- fear of being called “attention seeking” or that it's just a “phase”. And also not being taken serious enough because you haven't cut deep enough or been to the hospital for it’ (R142, female, patient aged 18–25).

Internalised stigma and shame were common barriers to accessing psychological therapies. People experienced great shame, embarrassment, stigma and worry over asking for help. The response of some clinical services to their previous help-seeking exacerbated these negative feelings. Combinations of stigma and high thresholds to access services left some participants feeling they did not deserve help for their self-harm.

‘Shame, guilt, trauma, internalised stigma, self-hatred, feeling unworthy and undeserving of treatment, stigmatising and dehumanising attitudes and stereotypes about self-harm, putting other people first (other patients, health resources, the time of health professionals)’ (R71, female, patient, aged 26–35).

Theme 3: challenging to access psychological therapies

Navigating access to psychological therapies was perceived as emotionally and physically difficult, irrespective of the pathway (e.g. referral by a clinician or self-referral). Participants felt greater anxiety, distress and uncertainty during the referral process over the possibility of further rejection. Unsuccessful referrals via several professionals and services added to already long waiting times and feelings of despair.

‘There were many unsuccessful referrals to begin with, which had a significant detrimental effect on my mental health, as I felt untreatable and lost hope. The successful referral, which led to my current Psychological input, took about 7 months from point of referral to initial assessment. This was difficult as it felt like a long time to sit with the uncertainty that I would just be assessed and denied treatment again, and it left me feeling very anxious’ (R46, patient, female, aged 26–35).

Self-referral was a core but challenging route into psychological therapies when people were mentally unwell and exhausted. Participants reported struggling with administrative issues, booking appointments and uncertainty when seeking help via the self-referral route.

‘They are usually in a low state of mind and have no motivation to ring places and make appointments’ (R130, patient, female, aged 40–59).

‘Understanding and awareness of the support available and how to access them is a barrier, but also if you're struggling with mental health issues you often won't have the confidence or even ability to be proactive or persevere in the face of waiting lists and organisations with limited resources’ (R141, male, patient, aged 40–59).

Participants reported a lack of information on psychological therapies, including what they are, where they are available and how to access appropriate treatments. This knowledge vacuum exacerbated challenges in navigating the mental healthcare system. Participants wanted information on the benefits of psychological therapies but felt that some healthcare staff knew little about available treatments. Other participants mentioned that staff did not discuss psychological therapies when they presented to healthcare services for self-harm (e.g. when speaking to the mental health team in the emergency department). General practitioners (GPs) were commonly utilised when trying to access psychological therapies, but their knowledge and response to self-harm also reportedly varied.

‘Emergency department staff were either not well-informed of psychological therapies or did not have the capacity to explain this when I was presenting regularly there. I was under the impression at the time that my GP needed to refer me for talking therapies that were more intensive and didn't know that I could self-refer to a lower step and be referred on’ (R144, patient, male, aged 40–59).

‘There is no information given following self-harm, when self-harming people are not aware of the help that is out there’ (R13, patient, male, aged 40–59).

Theme 4: exclusion, rejection and punitive treatment

Participants referred to thresholds, perceptions of risk and complexity, and restrictive criteria as barriers to accessing psychological therapies. Exclusion from IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) and some third-sector mental health charities for self-harm were common experiences among participants. Participants perceived that the stigma associated with self-harm resulted in some clinicians’ assumptions that they were emotionally unstable, or that their conditions were too complex or severe for psychological therapy in primary care. However, exclusion in secondary care was also common, because the service did not deem the person severely ill enough to warrant treatment.

‘My local psychological therapies service had refused to see me as I was deemed too severe. At the same time, I wasn't deemed severe enough for alternative services so I was left to cope alone. Things escalated over time and I didn't refer myself as I was struggling more than when they had said I was too severe’ (R105, female, patient, aged 26–35).

‘I know how to make a referral for IAPT, but they won't provide a service for me because of dx [psychiatric diagnosis]. Too mad for IAPT, not mad enough for CMHT [community mental health team]’ (R07, female, patient, aged 40–59).

Disclosing self-harm was a source of exclusion from psychological therapies. For example, some participants were unable to access IAPT, third-sector charities, or eating disorder services owing to disclosing self-harm. Other participants reported that some service providers insisted that the self-harm ceased prior to and during psychological therapy, or they would risk exclusion or discharge from the service.

‘When my daughter was an inpatient on an acute unit the staff said that if she self-harmed she would be discharged. The staff did not offer any support or help in stopping her from self-harming. When she became extremely distressed and unable to cope she self-harmed and was discharged immediately, despite being suicidal’ (R126, female, carer, aged 40–59).

‘Told I have to have 3 months with no self-harm before being allowed to start trauma therapy’ (R28, female, patient, aged 36–39).

Participants struggled to access psychological therapies because they were currently under existing mental health services or on the waiting list to access services. Punitive approaches to treatment and exclusions for self-harm left some people without support while struggling with their mental health. They had to manage their escalating distress alone or to try to find help for self-harm elsewhere, often at great expense.

‘Currently accessing eating disorder services therefore not eligible for therapy re: self-harm’ (R72, female, patient, aged 36–39).

‘It was difficult because I needed support, but other services won't see you in the meantime if you're already on the waiting list for an existing service’ (R146, patient, genderqueer, aged 18–25).

‘I have been discharged from psychological therapies after self-harm and no follow up. I have struggled to receive any psychological support about it’ (R37, female, patient, aged 26–35).

‘I pay for this [psychological therapies] privately. At a great expense to be honest’ (R112, patient, female, aged 26–35).

Figure 2 summarises participant views on barriers to accessing psychological therapies.

Section 2: improving access to psychological therapies

Theme 5: self-harm awareness and compassionate, supportive response

Participants suggested that greater awareness, understanding and training regarding self-harm were necessary for healthcare staff to reduce stigmatising responses and anxiety over including people in treatment. Participants also consistently highlighted the importance of a collaborative, compassionate, empathetic and hopeful response to patients seeking psychological therapy for self-harm.

‘A better understanding of self-harm among professionals to reduce the fear in treating these individuals’ (R105, female, patient, aged 26–35).

‘Staff having better empathy, a better attitude, better training, better understanding’ (R50, female, patient, aged 36–39).

Ongoing relationships with healthcare providers were an important source of support during long waiting times and mitigated some uncertainty and distress. Participants explained how mental health and primary care professionals advocated for access to psychological therapies and provided support during the self-referral process. Some participants also depended on a high level of continuity of care with their GP to get through challenging waiting times.

‘I have spoken to my GP who has given me information for a self-referral treatment. I found the company who did self-referral treatments not particularly useful and went back to my GP for further help… I regularly saw my GP during the wait for my current treatment which helped a lot; however I did struggle when my GP went on maternity leave as I felt I had to start over and struggled to talk as easily. However, the new doctor I saw was understanding and tried to listen and suggest simple ways to help whilst I was waiting for my therapy to start’ (R47, female, patient, aged 26–35).

Theme 6: widening access to appropriate and timely aftercare

Overwhelmingly, participants indicated that reducing waiting times for psychological therapies was vital when improving access to care for people who have self-harmed. Services for these patients were also deemed to require adequate funding, staffing and resources to meet patient demand and need.

‘Fund these services better. These services are important to the well-being of patients. There should be better access, more referrals and shorter timescales for referrals’ (R24, female, patient, aged 40–59).

Participants also preferred to have greater information about availability, access and benefits of psychological therapies from healthcare staff, in addition to ease of referral via a range of different services (e.g. helplines, hospitals, GPs). Participants called for interventions to be delivered at the right time and at accessible local locations, with flexibility around appointment times to accommodate work and other commitments.

‘To know more information about why it would be beneficial’ (R42, female, patient, aged 18–25).

‘Flexible appointments – late nights and weekends. More availability so lower waiting time’ (R84, female, patient, aged 18–25).

‘Make them accessible immediately after discharge from hospital’ (R114, female, patient, aged 60+).

Participants called for greater availability of tailored interventions for self-harm. Participants suggested having a greater choice of treatments to suit their individual needs, including peer-supported options and group and individual therapies. However, choice was also important in the delivery of therapies. Some people wanted enhanced access to group interventions or drop-in services, but others indicated that these interventions could trigger further self-harm episodes or social anxiety for some individuals. Other participants noted the importance of interventions to help them to stabilise prior to psychological therapy.

‘Informed by lived experience of self-harm. Offered peer support’ (R64, female, patient, aged 40–59).

‘Care tailored to needs rather than trying to fit people into boxes’ (R70, female, patient, aged 26–35).

‘I think it would have helped me to have some sort of motivational interview-type intervention to identify other support networks or strategies I could put into place while waiting for therapy. Once I started to do this for myself (using high-intensity exercise to manage my distress) I realised how powerful it was at getting me to a place where I could benefit from therapy’ (R44, female, patient, aged 26–35).

Figure 3 summarises participant views on improving access to psychological therapies.

Discussion

Main findings

We sought to understand contextual issues and experiences behind access to psychological therapies following self-harm from the perspective of patients. Disappointingly, given the publication of several clinical guidelines,3,29–31 our qualitative study suggests that access to psychological therapies remains low and challenging. Participants experienced multiple failed promises from mental health services after reaching out to seek help for self-harm. Lack of prompt intervention and distress and anxiety over long waiting times exacerbated hopelessness, self-harm and suicidal thinking for many patients.

Reported barriers to access psychological therapies included poor communication and information provision on psychological therapies from healthcare services, a lack of tailored interventions for self-harm, and stigmatising responses from some service providers. Exclusion, rejection and punitive approaches to self-harm and repetition were commonly reported, leaving many participants struggling alone during times of acute distress. Participant recommendations to improve access to psychological therapies for patients who have self-harmed included: (a) having timely access to aftercare from well-resourced teams; (b) receiving information about the benefits and availability of interventions from healthcare staff; and (c) increased accessibility and choice. Continuity of care and a compassionate response were deemed as paramount for any healthcare worker treating patients who have self-harmed.

Strengths and limitations

This study was part of an overall larger programme of work on psychosocial assessments and psychological therapies. The methodological strengths and limitations of the qualitative survey design have been comprehensively reported elsewhere.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11,Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood12 In brief, we conducted a qualitative survey to explore patient experiences and views on accessing psychological therapies following self-harm. Our aim was to explore shared context, meaning and experiences, rather than clinical management and generalisable attendance rates for aftercare following self-harm. Our approach was similar to that taken by other participatory studies, which enable wider access to a range of often stigmatised experiencesReference Braun, Clarke, Boulton, Davey and McEvoy22 while providing control and choice to participants.

Our recruitment strategy included hospital sites and community groups, enabling us to gather a wide range of experiences nationally. Our sample characteristics were broadly consistent with other community samples of self-harm, with the majority being women and White British.Reference MacDonald, Sampson and Turley32,Reference Hunter, Chantler and Kapur33 Self-harm rates are higher for women in several Western countries.Reference Carter, Page and Large34–Reference Finkelstein, Macdonald and Hollands36 Our results provide important information about individuals’ unmet needs when trying to access psychological therapies after self-harm. However, healthcare needs and inequalities when accessing psychological therapies may vary across specific groups (e.g. LGBTQ+, men, young people, older adults).3 Access to aftercare following self-harm is also lower among minority ethnic groups compared with White ethnic groups.Reference Farooq, Clement and Hawton37 Further co-designed studies using multiple mixed methods may be helpful to ensure more equitable inclusion in research and the development of tailored treatments for people who have self-harmed.

Our definition of self-harm includes any intentional act of self-injury or self-poisoning irrespective of method or suicidal intent, which is consistent with the definition used by NICE.3,30 We recognise that suicide attempts constitute a distinct subset of all self-harm episodes and require different treatment approaches. However, people can have several motivations for harming themselves, other than to die.Reference Rasmussen, Hawton, Philpott-Morgan and O'Connor38 It is challenging to accurately dichotomise suicidal intent, and classifications such as non-suicidal self-injury can lead to further exclusion or inappropriate treatment for patients.Reference Kapur, Cooper, O'Connor and Hawton7 For example, people who have used self-cutting or self-injury as a method are taken less seriously and are less likely to receive a psychosocial assessment and aftercare.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11 Motivations for self-harm and suicidal intent (including self-poisoning) fluctuate, yet people who have self-poisoned are excluded from definitions of non-suicidal self-injury.Reference Kapur, Cooper, O'Connor and Hawton7 Consistent with clinical guidelines, all patients who have self-harmed, irrespective of motive or suicidal intent, are at risk of further self-harm and suicide and should be offered psychological therapies.3,30

Comparisons with existing research

For decades, service provision for people who have self-harmed has been characterised as variable and patient experiences have been reported as generally poor.Reference Cooper, Steeg and Bennewith39 The most comprehensive study of patient management in 2013 found that referral rates to follow-up with specialist mental health services varied between 11% and 64%.Reference Cooper, Steeg and Bennewith39 Our qualitative study suggests a lack of available aftercare and that patients still struggle to access psychological therapies following self-harm. However, nationally representative survey research is needed to evaluate the quantity, quality and effectiveness of aftercare following self-harm.

Similar to the findings of Punton et alReference Punton, Dodd and McNeill16 and third-sector reports,15,Reference Wooster17,18 our results demonstrate the detrimental and unacceptable implications of struggling to access psychological therapies on patients. We found that waiting for too long was especially pernicious for people's mental health following an episode of self-harm. Participants in our study reported substantially reduced functioning, higher levels of emotional distress, and increased frequency of self-harm and suicidal thinking. Emotional distress was exacerbated by cumulative failed promises, poor communication and a lack of tailored interventions for people who have self-harmed.

Our findings are consistent with third-sector reports of poor patient experiences when accessing aftercare and the use of exclusionary thresholds.15 Reports of punitive treatment towards people who have self-harmed when accessing aftercare were also common in our data. Participants reported exclusion from psychological therapies when on waiting lists owing to perceived further self-harm risk and/or emotional instability. Others were requested by clinical services not to self-harm or risk exclusion from the service. This approach is similar to the use of ‘no-harm contracts’ for suicide risk (patient agrees not to self-harm, either verbally or in writing). Such approaches may negatively affect the therapeutic relationship, reduce the likelihood of disclosure, are not supported by evidence and may be harmful.Reference Rudd, Mandrusiak and Joiner40

The detrimental impact of stigmatising expereinces (societal and from healthcare staff) on patient engagement, help-seeking and well-being has long been reported.Reference MacDonald, Sampson and Turley32,Reference Saunders, Hawton, Fortune and Farrell41 Consistent with previous reports, we found that many participants experienced stigmatising responses from healthcare services and staff when they sought help for self-harm. These negative experiences contributed to internalised stigma and acted as barriers to subsequently accessing psychological therapies.

We focused on experiences of accessing psychological therapies rather than specifics of support that may be beneficial in interventions or the socioeconomic determinants associated with help-seeking. It is of course important to address wider socioeconomic determinants of healthcare access, given the association between deprivation and reduced access to specialist mental health services.Reference Farooq, Clement and Hawton37,Reference Carr, Ashcroft, Kontopantelis, While, Awenat and Cooper42 Future research is needed to understand contextual barriers in these areas and to improve access to evidence-based healthcare services for marginalised groups. Brennan et alReference Brennan, Crosby, Sass, Farley, Bryant and Rodriquez-Lopez43 suggest addressing societal, social and interpersonal aspects in interventions to reduce repeat self-harm frequency. However, given the individual nature of self-harm episodes, they caution against blanket recommendations in the development of any supportive interventions to reduce repetition.

Participants in our study reported the importance of GPs for accessing psychological therapies, continuity of care and support during waiting times. The quality of interactions with GPs was also reported as variable, which is consistent with other studies.Reference Troya, Chew-Graham, Babatunde, Bartlam, Mughal and Dikomitis13,Reference Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde and Chew-Graham44 GPs have an essential role in the provision of ongoing support and care continuity for patients who have self-harmed.Reference Mughal, Troya, Dikomitis, Chew-Graham, Corp and Babatunde45 Research is needed to understand shared communication and transitions between primary and secondary services to improve care quality for patients when unwell. GPs and staff working in GP surgeries may need support and professional training to confidently and compassionately support patients who have self-harmed.Reference Mughal, Troya, Dikomitis, Chew-Graham, Corp and Babatunde45

Participants reported a lack of information provision on psychological therapies from healthcare staff. Our previous study on referrer views of barriers to accessing aftercare for patients who have self-harmed indicates that this may partly be due to siloed working and service cuts and changes.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Marks, Monaghan, Asmal and Webb19 Staff may be unaware of available and suitable psychological therapies in their area or nationally for out-of-area presentations. Reluctance to mention or refer to aftercare may also be due to the dearth of available treatments, barriers to accessing services and apprehension over disappointing patients.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Marks, Monaghan, Asmal and Webb19

Implications for clinical practice and policy

The revised NICE guidelines for self-harm3 recommend follow-up within 48 h of a psychosocial assessment for self-harm, as well as recommending that any psychological interventions are based on a comprehensive assessment of needs, risk and coexisting conditions (see Fig. 4 for an infographic summary). Consistent with these clinical guidelines, participants in this study highlighted the importance of promptly delivered, collaboratively planned aftercare and tailored interventions that are determined on the basis of need. Participants also indicated the importance of staff having improved knowledge and information on the benefits and availability of accessible psychological therapies, as well as having choice in terms of delivery (e.g. group, individual). Above all, and consistent with other studies,Reference Quinlivan, Gorman and Littlewood11–15 participants highlighted the importance of compassionate, empathetic and hopeful responses from any staff working with people who have self-harmed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations for aftercare following self-harm,3 infographic summary.

Previous clinical guidance may not have been implemented widely owing to lack of capacity, ongoing staffing challenges, and fragmentation and rapid transformation of services. Implementation of the new self-harm guideline on future clinical practice may be better because of the increased focus on aftercare following self-harm and evidence base for psychological therapies.3 There is also substantial policy focus on reducing fragmentation between services, translating research to clinical practice and improving community mental health provision for people who have self-harmed.Reference Kapur46 Liaison psychiatry services have also transformed rapidly over the past decade and have received dedicated funding to expand services, which will hopefully include greater investment for out-patient clinics.Reference Jasmin, Walker, Guthrie, Trigwell, Quirk and Hewison47,Reference Walker, Barrett, Lee, West, Guthrie and Trigwell48

Our previous study on referrer views of barriers and/or facilitators to accessing aftercare for patients who have self-harmed indicates that prompt follow-up from the mental health liaison team may increase the likelihood of patients being accepted onto psychological therapies and improve safety planning and therapeutic relationships.Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Marks, Monaghan, Asmal and Webb19 Further co-designed studies using patient-determined outcomes are needed to evaluate models of follow-up care prospectively. Considering the frequent contact of patients who have self-harmed with emergency departments and primary care services,Reference Carr, Ashcroft, Kontopantelis, While, Awenat and Cooper42,Reference Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde and Chew-Graham44,Reference Mughal, Troya, Dikomitis, Chew-Graham, Corp and Babatunde45 these areas have significant scope for the provision of prompt follow-up care and improved integration between services for people who have self-harmed.

Current economic crises and the COVID-19 pandemic may have potentially long-lasting effects on psychological distress and the demand for mental health services.Reference Pierce, Hope and Ford49 Rates of self-harm are also increasing in many Western countries.Reference Griffin, Arensman, Perry, Bonner, O'Hagan and Daly50,Reference McManus, Gunnell, Cooper, Bebbington, Howard and Brugha51 Patients and staff have long voiced their frustrations over the lack of aftercare service provision for people who have self-harmed and the associated patient safety risks. There is an urgent need to transform services for people who have self-harmed and to develop promptly accessible models of safe and effective care, delivered by well-resourced and supported teams. Routine aftercare services for people who have self-harmed in England do exist, but they are rare,Reference Walker, Barrett, Lee, West, Guthrie and Trigwell48 which may widen inequalities in help-seeking and recovery. Decades of research on evidence-based care exists for people who self-harm, and there are substantial policy-funded initiatives to improve care quality.3,52,53 We need to prioritise learning from examples of good practice, understanding what works for whom, when, and where, address inequalities and implement beneficial change more widely.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.27.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants who have taken the time to generously share their often painful experiences of mental health services. We also thank our patient and carer (MS4MH-R), NIHR FAST-R and staff advisory panels for their involvement and insights throughout the research process. Thanks also to Dr Donna Littlewood for her excellent support and participation in discussions during the study; and to the mental health trusts, clinical research network staff, and community organisations for facilitating the research and assisting with recruitment.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the study. R.T.W. and N.K. were responsible for funding acquisition. We designed and developed the study through discussion at team meetings involving L.Q., D.L., R.T.W. and N.K. and at meetings with members of our PPI group and staff advisory panel. L.Q. coordinated data collection with input from public contributors with personal experience in this area, and D.L. L.Q. led the analyses with input from L.G., E.M., S.A., R.T.W. and N.K. L.Q. interpreted the results with input from L.G., S.M., E.M., S.A., R.T.W. and N.K. L.Q. wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts and approved the final version. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. N.K. is the guarantor of the study.

Funding

This paper presents independent research funded by the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre (grant reference number PSTRC-2016-003). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of interest

N.K. is a member of the Department of Health and Social Care (England) National Suicide Prevention Advisory Group. He chaired the NICE Guideline Development Group for the Longer-Term Management of Self-Harm and the NICE Topic Expert Group (which developed the quality standards for self-harm services). N.K. is currently chair of the updated NICE Guideline for Depression and topic advisor for the current NICE Guideline Development Group for the Longer-term Management of Self-harm, and is also supported by the Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available owing to restrictions of the research (consent and information that could compromise the privacy of some research participants).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.