On March 13, 1954, thousands of soldiers descended from the hills above the remote Mường Thanh valley in northwestern Vietnam. These infantrymen of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) were taking part in a massive assault, months in the making, on the heavily fortified French garrison in the town of Điện Biên Phủ, located on the valley floor below them. Thus commenced what would become a bloody 56-day siege, culminating eventually in the surrender of the last French outpost on May 7. The PAVN’s victory would prove to be a momentous event – not only in Indochina, where it led to the swift unraveling of France’s century-old empire, but across the Afro-Asian world, too, serving as a symbol and potential model for anticolonial movements elsewhere in a decolonizing world. As Frantz Fanon, the Martiniquais doctor, intellectual, and member of the Algerian nationalist movement, put it in his famous denunciation of colonialism in 1961, The Wretched of the Earth:

The great victory of the Vietnamese people at Điện Biên Phủ is no longer, strictly speaking, a Vietnamese victory. Since July 1954, the question which the colonized peoples have asked themselves has been: “What must be done to bring about another Điện Biên Phủ? How can we manage it?” Not a single colonized individual could ever again doubt the possibility of a Điện Biên Phủ. The only problem was how best to use the forces at their disposal, how to organize them, and when to bring them into action.Footnote 1

Fanon understood that the battle of Điện Biên Phủ had clearly been no guerrilla skirmish. The violence the Vietnamese had succeeded in generating and applying to the battlefield had no equivalent in the Algerian War or any other war of decolonization in the twentieth century for that matter. The PAVN’s commanding general, Võ Nguyên Giáp, had led a modern army consisting of seven divisions, equipped with intelligence, communications, and logistical services. Artillery guns had rained down shells on the French fortress for almost two months, turning the valley floor into a lunar landscape of craters and rubble. As the Algerians struggled against the same French Army in North Africa, Fanon wanted to know how the Vietnamese had fought a set-piece battle in the open against a conventional Western army at Điện Biên Phủ and won. Fanon was not alone in asking this question. Having survived the epic battle himself, French General Marcel Bigeard later marveled at what his adversaries had achieved before he was marched off to a prisoner-of-war camp: “And here I was now a prisoner of these little Vietnamese who in the French army we always considered them to only be good for working as drivers or nurses. Although these men of extraordinary morale had started out with nothing but a hodgepodge of weapons in 1945, they had an ideal, a goal: to drive out the French. In nine years, Giáp had indisputably defeated our Expeditionary Corps … There are lessons to be learned from this.”Footnote 2

Prelude: Going Deep into the Highlands

No one could have imagined at the start of the Indochina War that its endgame would occur in this remote valley in northwestern Vietnam. When full-scale hostilities had engulfed all of Vietnam in late 1946, Hồ Chí Minh moved the capital of his recently created state, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN), to the hills of Thái Nguyên province, above the French-controlled Red River Delta. From there, Hồ Chí Minh and his Communist Party administered a fragmented DRVN state that sprawled across noncontiguous “islands” of territory scattered from north to south. But thanks in no small part to the communist bloc’s aid and advice that began pouring into the DRVN in 1950, following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Hồ Chí Minh and his followers began to strengthen and consolidate their territorial control and their military power. As described in Chapter 10, the DRVN by 1954 controlled a vast sickle-shaped swath of territory that stretched from the Việt Bắc zone on the border with China, through the Highlands north and west of Hanoi, across the rice-rich provinces lying to the south of the capital, and all the way down into lower-central Vietnam (the regions designated on DRVN maps as zones III, IV, and V). The French continued to hold Hanoi, Haiphong, and most of the heart of the Red River Delta, as well as large areas in southern Vietnam, along with the central Vietnamese port cities of Đồng Hới, Huế, and Đà Nẵng.

A key development leading to the creation of the DRVN “sickle” had occurred in 1950, when the PAVN had used their first divisions and newly received Chinese support to crush French forces in the battle of Cao Bằng, thus securing a direct resupply route to the People’s Republic of China led by Mao Zedong. Giáp failed, however, to take the northern delta from French General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny in a series of bloody battles in 1951. Yet PAVN forces hung on to the strategic province of Hòa Bình, thanks less to a resounding battle victory than to the French decision to withdraw from there in order to secure their hold on the Red River Delta.

All of this led DRVN leaders and their Chinese advisors to rethink their military strategy. Starting in 1952, the Vietnamese refocused on seizing as much of the Indochinese Highlands as possible while maintaining guerrilla operations in the northern delta, where they continued to procure rice and recruit soldiers and porters. In October 1952, Võ Nguyên Giáp marched his PAVN troops deep into the northwestern hills for the first time, capturing French forward bases at Tú Lệ, Gia Hội, and Vӑn Yên. The PAVN’s 308th “iron division” overran Nghĩa Lộ in a powerful attack. Marcel Bigeard barely escaped to the west as the Vietnamese seized much of Sơn La province on the border with Laos. The French commander-in-chief, General Raoul Salan, who had succeeded de Lattre after the latter was diagnosed with terminal cancer, fully recognized the strategic import of the PAVN advances. As he informed his men: “We have taken the hit. The loss of the Nghia Lo sector is a painful one. But it is not a decisive one. … The game has only begun.”Footnote 3

To halt Giáp’s western expansion, Salan decided to transform the highland village of Nà Sản into a heavily fortified camp. He correctly anticipated that his Vietnamese nemesis would attack him there in order to secure his march westward toward Laos. In a flurry of activity in late 1952, Salan transformed this small upland settlement into an entrenched position. Bulldozers cleared the jungle while colonial soldiers and Vietnamese workers dug trenches, laid 5,000 mines, unfurled more than 1,000 tons of barbed wire, and installed heavy artillery. Engineers refurbished and extended the colonial airstrip there. More than six-tenths of a mile (1 kilometer) long, it could now handle an almost nonstop flow of landings and takeoffs. By November 23, Salan had 12,000 troops protecting the garrison. The French were thus ready when PAVN soldiers began arriving in the area. On November 30, Giáp ordered his men to take the camp. PAVN soldiers duly attacked with their legendary courage, but they immediately ran into barbed wire, mines, and a hail of machine-gun fire. French bombers attacked with impunity. Giáp called off the attack within days.

Salan won at Nà Sản, but it turned out to be a pyrrhic victory. Giáp simply sent his divisions around the enemy camp and deeper into northern Indochina. In April 1953, in a spectacular move designed to disperse the French Expeditionary Corps even further and expand the PAVN’s hold over Laos, PAVN troops seized Sam Neua and Phong Saly provinces and moved into the hills overlooking the Lao capital of Luang Prabang. In the end, the Vietnamese went no further, content to remain in Sam Neua and install their Laotian allies there, the Pathet Lao. Meanwhile, in central Vietnam, Giáp strengthened the PAVN’s 325th Division and even began dispatching parts of it into the Central Highlands. This Vietnamese “go deep” strategy did not necessarily guarantee victory in pitched battle, but it scattered the adversary’s forces and obligated the French to keep playing defense on an expanding Indochinese battlefield.

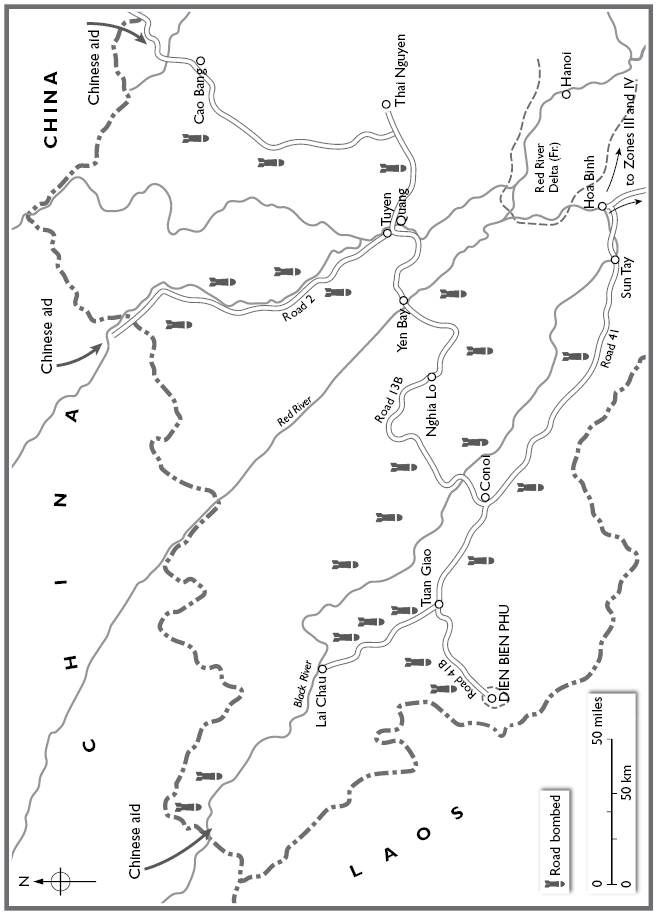

The Vietnamese could count on sustained Chinese advice and support for the next round of fighting during 1953–4. Mao Zedong had already rushed a Military and Political Advisory Group to northern Vietnam in 1950 to help train the Vietnamese army and outfit it with modern weapons. With the fighting in Korea over in July 1953, the Chinese began shipping as many trucks, artillery guns, and anti-aircraft systems as they could spare to their Vietnamese counterparts while the Americans did the same for the French. Based on what they had learned from failures to take the well-defended enemy positions at Nà Sản, the Chinese and Vietnamese understood that to overrun any fortified camp of this kind in the future, they would have to do several things: (1) bring unprecedented amounts of carefully calibrated artillery fire to bear on enemy positions; (2) use that artillery to destroy any enemy airstrip, while anti-aircraft guns prevented French planes from parachuting in supplies and reinforcements; (3) organize a fleet of trucks to transport weapons, ammunition, food, and medicines from the Chinese border to PAVN depots as close to the battlefield as possible; (4) conscript tens of thousands of laborers to repair bombed-out bridges and roads and carry weapons and food to the battlefield when the trucks could not; and (5) ensure that enough rice, medicines, and medical personnel were on hand to keep the troops and their people-powered logistics up and running for what would likely be a drawn-out and bloody affair (Map 11.1). This is where things stood on the battlefield in May 1953, when General Henri Navarre took over from Salan in Indochina.

Map 11.1 Vietnamese supply routes through China and Laos.

The Navarre Plan

Although Navarre did not know Indochina as intimately as Salan did, the new commander-in-chief in Indochina was serious about retaking the initiative from the enemy and helping his government end a war that had entered its eighth year.Footnote 4 Navarre began with a fact-finding mission to Indochina. He consulted officers and officials across the federation. He read Salan’s reports while preparing his own plan for the French governments led by René Mayer and (after June 1953) by Joseph Laniel. Both premiers were ready to pursue a political solution to achieve an “honorable exit” from the Indochina imbroglio. To this end, both expected the army to strengthen the government’s negotiating hand when serious talks commenced. The government left it up to Navarre to devise a strategy they could approve.Footnote 5

Their new general did not disappoint when, in mid-1953, he presented his project. The “Navarre plan” rested on four key assumptions. First, the new commander-in-chief realized that he would get few additional troops from Paris. The government needed them in the metropole as efforts got underway to allocate troops to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and a possible European Defence Community, both designed to contain the Soviet threat to Western Europe. To compensate in Indochina, Navarre further expanded the army of the Associated State of Vietnam (known officially as the Vietnam National Army, or VNA) to 200,000 troops by early 1954. Second, with the help of this expanding Vietnamese force, the French aimed to pacify the northern delta once and for all. This would deprive the enemy of his biggest source of rice and recruits and consolidate the Associated State of Vietnam’s territorial control at the same time. Third, the French Expeditionary Corps would avoid major engagements in the Northern Highlands for a year, both to secure the northern delta and to regroup and rebuild. Only during the second year of the plan, starting in the fall of 1954, did Navarre intend to go after the PAVN in the Highlands.

Lastly, Navarre decided that the French Expeditionary Corps, working with the VNA, would launch a major offensive called Operation Atlante against enemy zones in lower-central Vietnam. With French forces and their allies maintaining firm control over most of the Mekong Delta and the rest of Cochinchina, Navarre hoped to seize these DRVN-ruled provinces (known as Zone V) and turn them over to the SVN. This would grow the Associated State’s territory from the Mekong Delta up to about the 16th parallel and assuage their leaders’ demands for an increased say in military and political affairs. By taking the enemy’s zone south of Huế, Navarre also hoped to confine Giáp’s remaining divisions to the north, and then to destroy them there in an offensive during the 1954–5 dry season.

That was the plan, and it had its merits. Strangely absent, however, was any clear explanation as to what Navarre would do if the Vietnamese continued to “go deep” into the Indochinese Highlands, into the French-administered Tai federation in Lai Châu province in the far northwest of Vietnam or even deeper into Laos. There was no reason to suppose that the Vietnamese would not do so, and Navarre knew it. When he asked the French government in late July 1953 if he had to defend Laos in the event of an attack, he did not receive a clear answer until months later. Yet this did not seem to bother Navarre as much at the time as he would later claim. Although the commanding general knew that any enemy attack on Laos or the Tai federation would potentially force him to take a stand in the Highlands, he preferred to wait and see which way his adversary would actually go before committing himself. In the meantime, he would focus on the two linchpins of his plan: pacifying the northern delta and taking Zone V in Operation Atlante.

The Highlands or the Delta?

To make their own military plans for 1953–4, Vietnamese and Chinese strategists naturally wanted to know what Navarre was secretly cooking up. They had learned a few details of his projects on July 30, 1953, when a Parisian newspaper leaked details of the general’s recent meeting with government officials in the French capital. Of particular interest was the revelation that Navarre, when pressed, had stated that he would have a hard time defending Laos in the event of an enemy attack. The Vietnamese were able to piece together more details over the next few weeks, thanks to their espionage services. Sometime in early September, the Chinese provided the Vietnamese with “the entire Navarre plan.” Upon hearing his military intelligence experts sum up Navarre’s strategy, Hồ Chí Minh replied: “The enemy is massing his forces to occupy and hold the Tonkin lowlands, so we will force him to disperse his forces out to other sectors so that we can annihilate them.”Footnote 6

Despite this tough talk, the Vietnamese did not rush into the northwest. Nor did they abandon their interest in the delta. For now, the Vietnamese and their Chinese advisors “kept two irons in the fire,” as one eminent French historian of the French Indochina War put it.Footnote 7 They began preparing to renew their northwest campaign, but they tested the waters in the delta before committing. It is possible that some in the DRVN saw the lowlands as a better alternative to the massive population mobilization that a return to the Highlands would require. Logistics had been a nightmare when the army went deep into the northwest a year earlier, at Nà Sản and in Laos. Whatever the reasons, between late September and early November 1953, Giáp activated his battalions inside the delta and his divisions circulating around it. In late October, he ordered the 320th Division to infiltrate the delta from the southern side. Apprised, Navarre was waiting for him and responded with massive firepower in what he called Opération Mouette. When the fighting ended on November 7, 1953, the 320th had lost more than 1,000 men. Seizing the delta by outright force was now out of the question.

By going deep into the Highlands again, the Vietnamese would do what they did best: disperse enemy forces as thinly as possible across Indochina’s mountainous spine while still harassing them inside the northern lowlands. But this time, when Navarre came out to stop Giáp by throwing up an entrenched camp as Salan had done at Nà Sản, the Vietnamese would be prepared to go the distance. They correctly assumed that the French general would have to take a stand to protect, if not the Tai federation, then Laos for sure. Despite what he would say later, Navarre was confident at the time that he could handle any problem that might come up in the Highlands. If the adversary moved on him in an unacceptable way in the northwest, then he would do as his predecessor had done a year earlier: fly in several thousand crack troops, create a heavily fortified camp, supply it through an air bridge, win, and then evacuate if necessary. The increasing size of the Associated State of Vietnam’s army would allow Navarre to maintain his pacification operations in the Red River Delta and execute Operation Atlante in south-central Vietnam at the same time.

That was the plan. Navarre’s critical error was underestimating his enemy’s ability to learn from prior mistakes. First, the French general did not think the Vietnamese capable of bringing in the heavy artillery and anti-aircraft guns needed to destroy an entrenched camp’s artillery and airstrip. Second, Navarre did not believe the PAVN could organize the massive logistical system needed to supply a sustained, pitched battle in the Highlands. Third, he hoped that the Chinese would not increase the quantity and the quality of their military aid to the Vietnamese following the Armistice in Korea in July 1953. Last, the general also failed to consider how rapid diplomatic changes at the international level would require him to adjust on the battlefield.

The Changing International Context

Since Navarre was named commander-in-chief of the armed forces in Indochina in May 1953, several dramatic events had taken place at the international level. Two months earlier, the leader of the communist camp since the 1920s, Joseph Stalin, had died. Although Hồ Chí Minh was said to have shed tears on learning of this, not everyone in the communist bloc did. In fact, Stalin’s death opened the way for a new group of Soviet leaders in the Kremlin to emerge, ones who were increasingly keen on easing Cold War tensions in Europe (with Germany and in Berlin) and Asia (in Korea and Indochina). This would allow them to focus on the domestic economy and a more liberal form of communism to accompany it, a process better known as “de-Stalinization.” The Chinese, led by Mao, were also anxious to focus on domestic issues. Having applied full-scale land reform to all of the country since 1950, they wanted to turn to their new five-year economic plan as they raced down the road to collectivization. They brought their North Korean allies on board and, with Soviet support, signed an Armistice agreement ending the Korean War in July 1953.

The new American president entering the White House in early 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower, also wanted to ease international tensions in order to focus on domestic issues. He agreed to the ceasefire in Korea that kept the peninsula separated into two states at the 38th parallel. But Eisenhower was determined to continue support for the French and the State of Vietnam (SVN) in Indochina. While the Chinese built up the PAVN in Vietnam to help protect their southern flank against a hostile American attack, Washington was supplying and arming the French Expeditionary Corps and the VNA in order to stop the communists from moving into Southeast Asia. Eisenhower, like Mao, was paying attention when PAVN troops invaded Laos in early 1953.

In the summer of 1953, the French government’s position on Indochina began to shift. As negotiations accelerated to end the war in Korea, Joseph Laniel announced in late June that, as part of his new government’s mandate, he would actively pursue a negotiated settlement to the Indochina conflict. Pushing him in that direction were the stepped-up efforts by leaders in the “Associated” States of Vietnam and Cambodia to obtain full independence and leave the French Union. In 1953, Cambodia’s Norodom Sihanouk and Vietnam’s Ngô Đình Diệm went on “crusades” in France and North America to make their cases for independence and garner foreign support for it.Footnote 8 Many in the French political class, long supportive of the war and of the Indochinese empire it was designed to preserve, began to wonder if it was really worth the continued effort if their own partners wanted out so badly. Support for the French Indochina War in the National Assembly was declining fast, too, and the French public, never really interested in the conflict anyways, increasingly favored getting out. In response, the French government got serious about negotiations for the first time since the outbreak of general hostilities in 1946.

Following the signing of the Korean Armistice, the various parties began to talk earnestly about finding a similar solution for ending the shooting in Indochina. The Soviets suggested to the French that a negotiated settlement to the Indochina conflict could be found. The French broached the subject with the Americans. The Chinese reacted favorably to a Soviet proposal in September 1953 to convene a meeting of the “Big Powers” (the Unted States, France, Britain, and the Soviet Union plus China) to discuss major global disputes, including the Indochina conflict. Communist bloc exchanges with Vietnamese communists also yielded important changes in strategy. In a widely noted interview published in the Swedish paper, the Expressen, on November 26, 1953, Hồ Chí Minh indicated his party’s willingness to discuss a political solution to the war in Indochina.Footnote 9 However, he and his Chinese advisors needed a major victory on the battlefield first to strengthen the DRVN position at the negotiating table. And of course, Navarre needed exactly the same thing for his government.

Looking for a Showdown

With these events as a backdrop, Vietnamese leaders in charge of the PAVN moved first: unable to take the delta, in early November they initiated their Highland Plan by moving on Lai Châu province.Footnote 10 (The French had administered this colonial Tai “island” in the middle of DRVN territory since 1945.) Around November 10, the PAVN’s 316th Division left its base west of the Red River Delta to head northwest to rendezvous with the 308th on its way there, too. The French knew that their small contingent of mainly special-forces teams in Lai Châu could not protect the Tai federation against a PAVN attack. Moreover, Lai Châu was too close to China for comfort and too hard to supply by air. This is why Salan had earlier proposed the transfer of the Tai capital to Điện Biên Phủ. Navarre now concurred that Điện Biên Phủ was the best choice for defending Laos. The Mường Thanh valley in which Điện Biên Phủ sat was the largest in the northwest region. It had the required airstrip and would be easier to supply by air than Nà Sản or Lai Châu.

Điện Biên Phủ now acquired enormous importance for both sides. When the first PAVN regiments began moving toward Lai Châu in mid-November, Navarre issued orders to prepare for the airborne seizure of Điện Biên Phủ. Operation Castor was launched on November 20, 1953, with a massive deployment of airborne troops. Within days, they easily dislodged the small PAVN presence in the valley, quickly repaired the airstrip, and began turning Điện Biên Phủ into another entrenched camp, bigger and better than Nà Sản. Planes brought in artillery, machine guns, ammunition, and tanks, while soldiers and laborers felled trees, dug trenches, laid minefields, and unfurled tons of barbed wire. By the end of the year, the valley was home to 12,000 French Union troops and a handful of Tai villages.

When the Vietnamese learned that Navarre was moving on Điện Biên Phủ, Giáp immediately ordered his intelligence service to find out what was going on. Two questions were particularly important: Is the enemy going to withdraw? And how are they deployed? Scouts were dispatched to the valley in search of answers. Signals teams focused on intercepting enemy radio communications to glean details of troop positions and strength. The cartography service scrambled to provide the General Staff with an accurate map of Điện Biên Phủ. Seasoned communist interrogators began interviewing prisoners of war who knew the area. Meanwhile, Giáp ordered the 316th Division to change course and head for the valley. Similar orders went out to the 308th, the 312th, and the 351st. By mid-December, more than half of the PAVN was on its way to Điện Biên Phủ.

DRVN leaders and their Chinese advisors believed that Điện Biên Phủ might be the showdown they were anticipating. But they were not yet sure. Preparations began in earnest despite uncertainty about whether the French would stay put. Giáp hoped they would. Supplying this valley over a sustained period of time would be easier than in Nà Sản or areas further west. The DRVN controlled Hòa Bình, Nghĩa Lộ, and Tuần Giáo (a hub located east of Điện Biên Phủ). If they planned and executed it carefully, the Vietnamese were confident they could supply troops, weapons, and food to Điện Biên Phủ from southern China’s Yunnan province; from the western side of the DRVN’s Việt Bắc zone connected to the Chinese border at Cao Bằng; and from zones III and IV south of Hanoi. Thanks to their first thrust into the northwest in 1952, the Vietnamese were already hard at work building, repairing, and widening roads to move Chinese-supplied trucks to Cò Nòi via Route 13 and on to Tuần Giáo, thanks to Route 41. From there, thousands of porters pushing pack-bikes could transport weapons and food along 50 miles (80 kilometers) of trails leading to Điện Biên Phủ.

Navarre remained supremely confident that he could defeat the Vietnamese in the Highlands without sacrificing his control of the delta or his upcoming Atlante offensive on Zone V. On December 3, he informed the government that he would accept the battle for the northwest at Điện Biên Phủ. The fact that French leaders informed him that he would receive no more troops did nothing to change his mind. On December 6, Navarre gave the order to evacuate Lai Châu in Operation Pollux. If Giáp attacked him at Điện Biên Phủ, he reasoned, his forces would crush the PAVN once and for all. The French slang expression for that action, casser du Viet, could be heard on the lips of officers and soldiers alike as they readied for the clash. René Cogny, second to Navarre and the head of the army in northern Vietnam, dared Giáp to attack: “I want a clash at Điện Biên Phủ. I’ll do everything possible to make him eat dirt and forget about wanting to try his hand at grand strategy.” It is true that Navarre could have evacuated Điện Biên Phủ by air, even in late December; but he did not do so for one very simple reason: he did not want to. He wanted the fight.Footnote 11

So did the Vietnamese. By the end of December, Giáp’s divisions had surrounded the valley from all sides and had begun installing carefully camouflaged artillery and anti-aircraft guns in the hills. The Vietnamese were confident that if they could line everything up correctly, this was a battle they could win before negotiations began in Europe. “Navarre had spread out his fingers,” the deputy director of military intelligence at the time recalled. The Vietnamese leadership had enough information, he continued, “to make the decision to destroy the Điện Biên Phủ fortified defensive complex, turning this into the key battle of our entire 1953–1954 Winter–Spring plan. Điện Biên Phủ became a battle that neither the enemy nor our side had originally anticipated in our plans … We were concerned that the enemy would retreat and abandon the area, while the enemy was afraid that we would not dare to attack. At this point the battle of wits entered the decisive phase.”Footnote 12 It is hard to put it any better.

No one on the Vietnamese side thought this would be an easy victory, though. Indeed, Giáp had to be very careful not to attack prematurely and lose his best divisions in a hail of enemy artillery fire. Giáp’s caution became evident in January 1954, when he called off the first scheduled attack on the enemy camp. Initially, the PAVN and their Chinese advisors had planned to hit the French camp hard and fast (“Attack swiftly to win swiftly” was the slogan). The goal was to improve the government’s negotiating position with a quick victory as diplomats were about to take up the Indochina question for the first time in a Great Powers meeting scheduled for January 25 in Berlin. Although Giáp’s troops were as keen on a fight as Navarre’s were, the Vietnamese general delayed the order when some of his artillery failed to arrive on time and the enemy’s perimeter turned out to be much stronger than initially thought.

The good news for Giáp was that Navarre launched Operation Atlante in lower-central Vietnam at the same time. To disperse Navarre’s forces even further and give his own men time to put more artillery into place around Điện Biên Phủ, Giáp ordered his troops in Zone V to attack into the Central Highlands. He even instructed the 308th Division to briefly leave Điện Biên Phủ and move into northern Laos. Although diversionary, this move served to bring back rice, secure more territories for the Pathet Lao, and make a mockery of the French claim that the engagement at Điện Biên Phủ would stop the PAVN from threatening Laos. In mid-February, the 308th returned to Điện Biên Phủ and joined a total force of 51,000 PAVN regulars now waiting in the hills to attack the 12,000 French Union troops in the garrison. Meanwhile, the Vietnamese infiltrated parts of the 320th Division back into the Tonkin Delta – just as Giáp had done to Salan when the latter had committed to Hòa Bình and Nà Sản during 1951–2. PAVN “pacification” operations in the Red River Delta resumed like clockwork.

This is where Navarre committed the error that would cost him the battle. He knew in early January that the Vietnamese were successfully bringing in artillery. He was sure that Giáp was going to throw everything he had at him at Điện Biên Phủ – not in the delta, not in Laos, and certainly not in Zone V or the nearby Central Highlands. The French general also knew that there was a linkage between negotiations and the battlefield, which could make Điện Biên Phủ the decisive battle of the war. And yet he refused to cancel Operation Atlante to free up additional troops to help defend Điện Biên Phủ. By persisting with his attack on lower-central Vietnam, Navarre missed a chance to provide the reinforcements that might have tipped the coming battle in France’s favor.

The Battle

The battle of Điện Biên Phủ began on March 13, 1954, with a barrage of PAVN artillery fire.Footnote 13 Soon thereafter, thousands of PAVN troops stormed down from the hills to attack the French fortress below. Soldiers rushed the two most vulnerable French positions on the northern side of the camp, Gabrielle and Béatrice, and controlled them within a few days. On the French side, five remaining strong points protected the command center in the heart of the valley. The commanding officer was General Christian de Castries. He relied on the two officers, colonels Pierre Langlais and Marcel Bigeard, to protect the perimeter and to counterattack. They and their men fought with uncommon valor. But they were powerless to prevent Giáp from achieving what he had failed to do at Nà Sản: destroy the runway and weaken the French air bridge.

On the eve of the battle, the Frenchman in charge of the camp’s artillery, Captain Piroth, had bragged to Navarre that “no Viet Minh cannon will be able to fire three rounds before being destroyed by my artillery.” He should have held his tongue because, within a few hours of the start of the battle, it was obvious that the French had badly misjudged the PAVN’s ability to deliver concentrated artillery fire with deadly accuracy. Four days later, the Vietnamese artillery had rendered the airstrip largely unusable. As French bombers scoured the hills in search of the enemy’s guns, Piroth killed himself rather than carry on.

None of this meant that the French were suddenly destined to lose the battle, but it did mean that Điện Biên Phủ would immediately become the site of a siege battle without precedent in any war of decolonization in the twentieth century. For the time being, the troops in the valley could hold on, thanks to the supplies and soldiers that continued to arrive by parachute. However, unlike at Nà Sản, Giáp had anti-aircraft guns hidden in the hills above Điện Biên Phủ. They were soon sending flak into the sky, forcing enemy planes to fly as high above them as 6,500 feet (2,000 meters). This, coupled with increasingly bad weather as the rainy season arrived, made it increasingly difficult for French pilots to resupply the besieged camp by mid-April.

On the ground, the experience of siege warfare was brutal and exhausting for all involved. With both sides in possession of artillery and machine guns, soldiers immediately dug into the ground as exploding shells churned the dirt into piles of rubble and created a crater-like landscape. Having disrupted the French air bridge in the first attack, Võ Nguyên Giáp spent the second half of March spinning a web of trenches around the heavily armed cluster of positions protecting the shrinking enemy fortress. Soldiers and laborers worked day and night with their pickaxes and shovels. With their trenches finally in place, the PAVN launched its second assault on March 30. After making considerable headway over the first two days, a ferocious counterattack led by Langlais and Bigeard pushed the attackers back, with high casualties on both sides. The French fortress held. On April 6, Giáp called off the second attack and requested new recruits. Meanwhile, the French Air Force parachuted in the last troops Navarre could spare. (He still refused to cancel Atlante.) In all, 16,000 French Union troops fought at Điện Biên Phủ.

The start of the third Vietnamese attack on April 26 coincided with the opening of the Geneva Conference on Korea and Indochina. Điện Biên Phủ had to fall, and fast, in order to strengthen the communist negotiating position. On May 1, thousands of PAVN troops went over the top again as Giáp unleashed his artillery on the camp. Thanks to the Chinese, the Vietnamese also deployed Soviet Katyusha truck-mounted rocket launchers. They now concentrated these on the enemy positions, with deadly effects. The Katyushas, which the Soviets had first used against the Nazis, were also known as “Stalin’s organs” because of the screeching sound the shells made as they raced through the air. The rockets rained down during the last desperate days of fighting as Giáp’s men fought their way, meter by meter, trench by trench, until the last enemy position surrendered on the afternoon of May 7, 1954. The victorious troops raised the DRVN flag over de Castries’ bunker that day, marking an epic victory of the colonized over the colonizer in set-piece battle. To Fanon’s disappointment, there would be no replication of Điện Biên Phủ in any other war of decolonization in the twentieth century.Footnote 14

The valley in the aftermath of the battle was a scene reminiscent of Verdun or battles coming out of World War II. Artillery explosions had obliterated the Tai villages that had stood for generations and turned the surrounding green rice fields into ugly craters and mounds of rubble. Although PAVN troops suffered many casualties storming the heavily defended fortress, the French endured the terror delivered by the enemy’s artillery, machine guns, and rockets. As one of the survivors in the French camp later recalled: “Shells rained down on us without stopping like a hailstorm on a fall evening. Bunker after bunker, trench after trench, collapsed, burying under them men and weapons.”Footnote 15 On top of it all, heavy and seemingly incessant rain, which had started in April, filled the trenches with knee-deep mud, breeding disease and swarms of yellow flies looking for hosts. They found them among the bodies strewn across this lunar landscape.

Hardest to repair was the violence this type of warfare inflicted on the surviving soldiers. Artillery fire accounted for 86 percent of the wounds inflicted on Vietnamese bodies at Điện Biên Phủ. Of those suffering severe head and back injuries, hundreds of them would never walk again – disabled, paralyzed, or worse. Similarly, 75 percent of all French Union troop losses were the result of artillery fire.Footnote 16 This was clearly not “guerrilla warfare.” One veteran recalled the hell he had witnessed at Điện Biên Phủ as a medic:

I was responsible for the transport teams evacuating the dead and wounded for our unit, A1. I was in a shelter some 500 meters from the hill [which was under attack]. I could see the bodies of our dead strung all over the ground, at the mercy of all kinds of enemy projectiles. I couldn’t hold back my tears at the scene of such violence, at the brutality of the battlefield. The evacuation became increasingly difficult because we had a limited number of porters. I had one company of porters. We waited for the rare moments of calm when we could recover our comrades on the hill. I lived among the dead. Many had to wait for days until we could bring them to the lines at the rear; often, their bodies were no longer intact. Many couldn’t be identified, for we hadn’t even had the time to take down the name, age, or origin of these new recruits. There are others who stayed on this hill forever, as we never succeeded in recovering their bodies.Footnote 17

Not everyone could take it. Many could not overcome all the physical and psychological trauma they had encountered in a few crowded hours. Others were exhausted from the endless digging to extend the trenches forward. But the General Staff needed the lightly wounded back in action as quickly as possible. Even some of the communist political cadres attached to combat units faltered. Apparently, the French (re)capture of the fortified position they called Eliane on April 11 sapped confidence along the PAVN lines. On April 29, as the third attack got underway, Giáp sent strict orders to his political officers in which he criticized creeping defeatism among the troops, cadres, and officer corps:

All the necessary conditions are there for us to win. However, there is still one great obstacle, one extremely dangerous obstacle blocking our ability to carry out that task. That hindrance is rightist negative thinking that has seriously and insidiously infested the ranks of our cadres and committees within the party. If we do not wipe out this rightist negative thinking, then it will be extremely difficult for us to carry out our glorious victory.Footnote 18

“Rightist deviationism” was communist doublespeak for troubling cases of insubordination, cowardice, fear of death and injury, exhaustion, and lack of morale. To fix these problems, the party center organized three days of intensive study sessions, propaganda drives, and rectification campaigns to raise morale, assert party control, and, in so doing, return as many men to their combat positions as possible. The French camp had to fall, period.

Beyond the Valley

There was more to this epic battle than what happened in the valley.Footnote 19 For the soldiers, the fighting may have started on March 13, but for hundreds of thousands of peasant conscripts, the hardship and hard work began months earlier. From November 1953 onward, the communists mobilized tens of thousands of people to transport food, salt, medicines, ammunition, and weapons. The Communist Party’s General Supply Office administered human and mechanical logistics under the leadership of Trần Đӑng Ninh. Despite the obstacles, this man of real organizational talents ensured that food, weapons, and medicines got to the front lines. Thanks to the general mobilization law of 1950, Ninh conscripted men and women into massive supply groups, organized them into work teams, and confiscated rice when he had to, as well as boats, bikes, cars, and packhorses. The supply section also had a fleet of Molotova and GMC trucks at its disposal, around six hundred in all. While manpower remained important, mechanized logistics now transported most of the heavy weapons from China to areas near Điện Biên Phủ. A telephone and radio network coordinated this work. Without this mechanization of the rear lines and wiring of the front, there would have been no PAVN victory at Điện Biên Phủ.

However, the labor of the conscripts was equally indispensable. Starting in November 1953, work teams began repairing and widening roads running to Điện Biên Phủ through the Tuần Giáo interchange: from southern China’s Yunnan province via Lai Châu, from zones III and IV south of Hanoi, and from China’s Guangxi province by way of Cao Bằng and Thái Nguyên. Despite French bombing, the Vietnamese relied heavily on roads 13 and 41 to ship supplies to Điện Biên Phủ. Each time the French destroyed a bridge or bombed out the road, thousands of workers arrived on the scene with their shovels, pickaxes, and baskets to repair them or build a new segment to keep the trucks moving and the supplies flowing. Those six hundred transport trucks supplied ammunition and heavy weapons. French bombers destroyed thirty-two of them, while forty-three overturned on dangerous roads. When artillery arrived at the Tuần Giáo hub, technicians there dismantled them into smaller pieces that porters, oxen, and horses lugged into the hills overlooking Điện Biên Phủ. There, another group of specialists in carefully hidden places were tasked with putting the guns back together. French bombers circled constantly above, looking for targets. Human porters and animals also brought in rice, medicines, and supplies from nearby areas and from zones III and IV south of Hanoi. In all, 261,453 people served as human transporters. Of the 21,000 pack-bikes pushed by people carrying rice and medicines, more than half came from Zone IV. Twelve thousand bamboo rafts and five hundred horses also contributed to this logistical victory.

Food was as important as artillery. The communists might have initiated land reform in 1953 to better mobilize the peasantry for war, but they knew that they would not improve agricultural production in time for their operations at Điện Biên Phủ. Trần Đӑng Ninh and his supply team had to provide enough rice, meat, and salt to feed the four divisions setting up camp around Điện Biên Phủ in December 1953. The quarter of a million peasants they had conscripted had to eat, too, as well as the horses and oxen. At the outset, Ninh’s team worked on the assumption that their army would attack the enemy in January 1954 and win quickly. However, the party’s decision not to attack in January and to implement a siege sowed panic as the supply section’s officials scrambled to find the additional rice to feed so many people during what ended up being a military operation of six months (from late November 1953 to early May 1954). Finding the 6,000 tons of rice needed for the January attack had been hard enough; now they would need to double that, if not more. Once again, the communists had no choice but to lean even harder on the peasants, promising them that they would eventually get land, but requisitioning their rice and animals by force if necessary.

It is hard to convey how desperate the situation truly was on the food front. The People’s Army had already depleted rice reserves in the northwest during its operations in the Highlands in 1952–3, triggering famine in large parts of the Tai country where Điện Biên Phủ was nestled. Many areas in the northwest were still experiencing famine. The party ordered each division to plant its own vegetables and raise its own animals. The government provided commanders with money to buy rice and animals whenever they could instead of taking them by force. In the end, the supply section obtained 25,000 tons of rice and almost 2,000 tons of meat through force, persuasion, or purchase. Most of this went to the front lines. The rest fed the supply teams and the civil servants and cadres involved in this massive operation.

The rear lines also extended northward into Laos and China. Even before Giáp had cancelled the January attack, Trần Đӑng Ninh had dispatched his deputy to southern China in search of rice and salt. Between February and April 1954, the Chinese authorities in Yunnan province provided 15 tons of salt and 1,870 tons of rice, as well as several thousand tons of grain for the 500 horses. The Chinese also provided 6,000 rafts that transported rice, salt, and animals down the Jin Shui River to Lai Châu province’s Black River. Meanwhile, the Vietnamese worked with their Laotian allies in the rice-rich areas of Sam Neua and Phong Saly to procure 1,700 tons of rice and other supplies.Footnote 20

As the fighting unfolded in the valley, French bombers killed an untold number of civilians in work and supply teams in the surrounding hills. Hubs such as Cò Nòi and Tuần Giáo came under intensive bombing. In one French raid at “KM13,” on the road running from Tuần Giáo to the battlefield, ninety porters died in a matter of minutes. Despite attempts to hammer them into line through heavy doses of propaganda, the communists had to accept the desertion of dozens of civilian teams. These people were simply terrified of dying in a hail of fire. At least half the porters and work teams were made up of women. French bombers inflicted death and injury regardless of gender.

Glorious though the victory was, Điện Biên Phủ came at a great cost for the Vietnamese. The official number of Vietnamese military casualties for the battle in the valley is 13,930, with 4,020 of that number listed as killed or missing in action. But French military intelligence estimated that the Democratic Republic of Vietnam lost around 20,000 combatants. The latter number is closer to the truth. None of the statistics, however, count the thousands of porters killed or missing in action. During the Điện Biên Phủ campaign (November 1953–July 1954), one can safely assume that the DRVN lost 25,000 souls in all, men and women, civilians and combatants involved in the endgame of 1953–4.

Conclusion

Although the price of victory was high, the epic nature of the military achievement of the PAVN at Điện Biện Phủ was indisputable. But what, exactly, had the Vietnamese accomplished by winning the battle? Had they in fact secured the decolonization of Vietnam, as Fanon believed? By signing the ceasefire with the French at Geneva on July 21, 1954, Hồ Chí Minh and his party accepted the provisional division of Vietnam at the 17th parallel. Although the Soviets and Chinese pressured the Vietnamese to accept the compromise terms on offer at Geneva, DRVN leaders had their own reasons to strike a deal. For one, Hồ Chí Minh and his party conceded in internal debates in July that although they might have won an historic battle over the colonizer at Điện Biên Phủ, they had not yet attained the military capabilities needed to defeat the French Army in all of Indochina. Second, the Vietnamese and their communist backers in Beijing and Moscow feared that the Americans would intervene militarily if they did not make peace at Geneva. In addition, Hồ Chí Minh and his entourage recognized that the protracted war they had been fighting since 1945, and especially the conventional one they had added to it in 1950, had taken a terrible toll on their people, with Điện Biên Phủ as the most painful chapter in that story. By going for broke in this Highland showdown, the Vietnamese had pushed their state, its army, and the population to the breaking point. Their backs against the wall, the Vietnamese people could not give any more, as the French colonialists continued to bomb and the communists asked for ever greater amounts of manpower and food. Even the promise of land was not enough. If the war continued, Hồ Chí Minh and the DRVN risked driving their people into the ground and pulling down the communist temple on their heads before it had even been completed.

In the end, Hồ Chí Minh and his party opted to roll the political dice at Geneva. They signed the ceasefire agreement with the French on July 21, 1954, hoping that a separate declaration (duly noted but never signed by the Americans or the leaders of the State of Vietnam) to hold elections two years later would allow them to recover the rest of Vietnam. If, however, a political solution failed, the Vietnamese reserved the right to resume the war where they had left off in July 1954. As it happened, their last engagement had taken place not at Điện Biên Phủ in the north, but in the Central Highlands, where the 325th PAVN division had last struck the French in the battle of Mang Yang pass near Pleiku. This was the same area where the PAVN would engage the US Army’s 1st Calvary division in the battle of Ia Drang of November 1965, the first major battle between American and PAVN regular ground forces. As momentous and consequential as the battle of Điện Biên Phủ had been, it had not settled the unresolved disputes that lay at the heart of the conflict. As a result, the Indochinese Highlands would once again become the scene of massive and bloody clashes between conventional armies wielding the most modern armaments available.