Alcohol use disorder (AUD) affects an estimated 5% of adults worldwide and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.1–Reference Carvalho, Heilig, Perez, Probst and Rehm3 AUD has been identified as among the strongest risk factors for suicidal behaviour.Reference Darvishi, Farhadi, Haghtalab and Poorolajal4–Reference Crump, Sundquist, Sundquist and Winkleby9 Men or women with AUD have been reported to have more than fourfold risks of completed suicide compared with the general population, after adjusting for sociodemographic differences and other psychiatric and somatic disorders.Reference Crump, Sundquist, Sundquist and Winkleby9 Because of these high risks and its high overall prevalence, AUD has been estimated to account for 20% of all disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost due to suicide.10 Little is known about healthcare utilisation patterns prior to suicide in persons with AUD. Such patterns may reveal key opportunities to prevent suicide in this high-risk patient population.

Several studies have explored healthcare utilisation before suicide in general populations or patient samples. Most of these studies have reported that a large majority (80–90%) of individuals who died by suicide had a healthcare encounter in the previous 1 year,Reference Pedersen, Fenger-Gron, Bech, Erlangsen and Vestergaard11–Reference Andersen, Andersen, Rosholm and Gram15 and approximately 30–40% had a primary care encounter in the previous 1 month.Reference Pedersen, Fenger-Gron, Bech, Erlangsen and Vestergaard11,Reference Hochman, Shelef, Mann, Portugese, Krivoy and Shoval16 Healthcare utilisation also varies across different psychiatric disorders and patient subgroups.Reference Cho, Kang, Moon, Suh, Ha and Kim13,Reference Pearson, Saini, Da Cruz, Miles, While and Swinson14 A US study of male military veterans with substance use disorders (either AUD or drug use disorders) reported that 94.6% and 55.6% had a healthcare encounter within 1 year or 1 month before suicide respectively.Reference Ilgen, Conner, Roeder, Blow, Austin and Valenstein17 However, to our knowledge, no large population-based studies have examined these patterns specifically in persons with AUD.

We conducted a large cohort and nested case–control study in Sweden to examine healthcare utilisation patterns among adults with AUD who died by suicide. Our goals were to: (a) determine the risk of suicide among persons with AUD; (b) provide the first population-based estimates of healthcare utilisation prior to suicide in this patient population; and (c) assess for gender- and age-specific differences. The results may help inform the development of more effective healthcare intervention strategies to prevent suicide in persons with AUD.

Method

Study design and population

This study consisted of both cohort and nested case–control designs. First, a national cohort study was conducted of all 6 947 191 persons aged ≥18 years who had lived in Sweden for at least 2 years as of 1 January 2002, as identified in the Swedish Total Population Register. This register contains demographic information for nearly 100% of persons living in Sweden since 1968.Reference Ludvigsson, Almqvist, Bonamy, Ljung, Michaelsson and Neovius18 Within this cohort, a nested case–control study was conducted of all 2601 persons who died by suicide during 2002–2015 and who had a registration of AUD within the previous 2 years, as identified using national population registries (as described below). Each of these individuals was matched to 10 controls randomly sampled from the general population who had the same birth year, birth month and gender, and who were still living in Sweden on the respective individual's death date (the index date).

We assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human participants were approved by the ethics committee of Lund University in Sweden (no. 2013/736). Participant consent was not required as this study used only anonymised registry-based secondary data.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) ascertainment

Alcohol use disorder was identified using nationwide diagnoses and alcohol-related convictions reported during 2000–2015. First, ICD codes for AUD were identified from all primary or secondary diagnoses in the Swedish Hospital, Out-Patient, and Primary Care Registries (ICD-8: 291, 303, 357F, 425F, 535D, 571A–571D, 980, V79B; ICD-9-CM: same codes as ICD-8, plus 305A; ICD-10-CM: F10, except F10.0, Z50.2, Z71.4, E24.4, G31.2, G62.1, G72.1, I42.6, K29.2, K70.0–K70.9, K85.2, K86.0, O35.4). The Swedish Hospital Registry started in 1964 and initially included all hospital discharge diagnoses from six populous counties in southern Sweden, but was gradually expanded to cover >99% of the national population since 1987.Reference Ludvigsson, Andersson, Ekbom, Feychting, Kim and Reuterwall19 The Out-Patient Registry started in 2001 and contains out-patient diagnoses from all specialty clinics nationwide. The Primary Care Registry initially included all primary care diagnoses from two populous counties covering 20% of the national population starting in 1998, but was expanded in 2001 to cover approximately 45% of the national population and since 2008 has covered 75%.Reference Sundquist, Ohlsson, Sundquist and Kendler20 In addition, AUD was identified in all individuals having at least two convictions for drink-driving (law 1951:649) or drunk in charge of a maritime vessel (law 1994:1009), using nationwide data from the Suspicion and Crime Registers.

Suicide ascertainment

The study cohort was followed up for suicide deaths from 1 January 2002 through 31 December 2015, using nationwide data from the Swedish Cause of Death Registry. This registry includes deaths and ICD codes for cause of death among all persons registered in Sweden since 1960, with compulsory reporting nationwide. All intentional deaths were identified using ICD-10-CM codes X60–X84, and deaths of undetermined intent were identified using ICD-10-CM codes Y10–Y34. Prior studies have suggested that substantial numbers of suicides may be misclassified as deaths of undetermined intentReference Ohberg and Lonnqvist21,Reference Bjorkenstam, Johansson, Nordstrom, Thiblin, Fugelstad and Hallqvist22 and that such misclassification may be more common in persons with AUD.Reference Lindqvist and Gustafsson23,Reference Allebeck, Allgulander, Henningsohn and Jakobsson24 In the present study, intentional deaths and deaths of undetermined intent were analysed together as the primary outcome and separately as secondary outcomes.

Ascertainment of healthcare encounters

In the nested case–control study, all healthcare encounters in in-patient, specialty out-patient and primary care out-patient settings during the year prior to the index date, regardless of diagnosis, were identified using the Swedish Hospital, Out-Patient and Primary Care Registries (as described above). To exclude encounters that were the direct result of a fatal suicide attempt, hospital admissions were included only if the discharge date preceded the recorded date of death. In addition, all healthcare encounters were excluded if they occurred on the death date and contained a diagnosis directly related to mortality (i.e. ICD-10-CM R96–R99: ‘ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality’).

Other study variables

Sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric disorders that may be associated with AUD, suicide and healthcare utilisation were examined as adjustment variables. Sociodemographic factors were identified from the Total Population Register and national census data and were 100% complete. These variables included age (continuous and categorical (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, ≥75 years) to allow for a non-linear effect), gender, marital status (married/unmarried) and education level (≤9, 10–12, >12 years) at baseline. Psychiatric disorders included drug use disorders (ICD-8: 304; ICD-9-CM: 292, 304–305, except 305.0 and 305.1; ICD-10-CM: F11–F16, F18–F19; Suspicion Register codes 3070, 5010–5012; Crime Register codes for laws covering narcotics (law 1968:64) and drug-related driving offences (law 1951:649)), affective disorders (ICD-8: 296.0–296.8, 300.4; ICD-9-CM: 296A–296E, 296W, 300E, 311; ICD-10-CM: F30–F39, except 32.3), anxiety/phobia disorders (ICD-8: 300.0, 300.2; ICD-9-CM: 300A, 300C; ICD-10-CM: F40–F41), psychotic disorders (ICD-8: 291, 295, 297–299; ICD-9-CM: 291–292, 295, 297–299; ICD-10-CM: F20–F25, F28–F29, F32.3, X.5 in F10–F19), personality disorders (ICD-8/9-CM: 301; ICD-10-CM: F60), and other psychiatric disorders (ICD-8: 300.1, 300.5–300.9; ICD-9-CM: 300B, 300F–300H, 300W, 300X, 307B, 307F; ICD-10-CM: F43–F45, F48, F50).

Statistical analysis

In the national cohort analysis, Poisson regression with robust s.d. was used to determine incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for suicide associated with AUD. Analyses were conducted using three models: (a) unadjusted, (b) adjusted for sociodemographic factors (age, gender, marital status, education level) and (c) further adjusted for psychiatric disorders (as above).

In the nested case–control analysis, Poisson regression with robust s.d. was used to compute prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs for the prevalence of a healthcare encounter in specific time intervals before the index date (<2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year) among the people with AUD compared with the controls. In addition, generalised linear models with a Poisson distribution, identity link function and robust s.d. were used to compute prevalence differences (PDs) and 95% CIs for those same prevalences in the people with AUD versus controls. Each of these models was performed both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates (as above). Poisson model goodness-of-fit was assessed using Pearson and deviance tests and was met in each model.

Interactions between AUD and gender or age were examined in relation to healthcare encounter prevalence on both the additive and multiplicative scale. In a sensitivity analysis, the analyses of healthcare utilisation were repeated after identifying AUD on the basis of any reported lifetime history rather than within the previous 2 years. All statistical tests were two-sided and used an α-level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1 for Windows.

Results

A total of 256 647 persons (3.7% of the cohort) were identified with AUD during the study period. Table 1 reports participant characteristics in the total cohort, those with AUD, all persons who died by suicide, and all persons who died by suicide and had an AUD registration in the previous 2 years. Compared with the total cohort, persons with AUD or who died by suicide were more likely to be ages 35–64 years, male or unmarried; have low education level, drug use or other psychiatric disorders; and/or have more frequent hospital admissions or specialty clinic encounters. In addition, persons with AUD were more likely to average at least 2 primary care encounters per year.

Table 1 Characteristics of study participants, 2002–2015, Sweden

AUD and risk of suicide

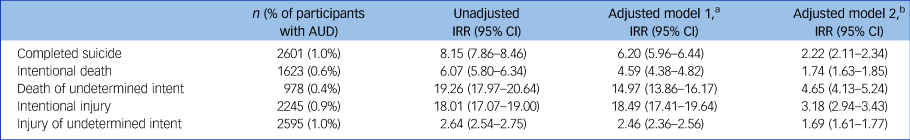

In 86.7 million person-years of follow-up, 15 662 (0.2%) persons in the entire cohort died by suicide (18.0 per 100 000 person-years), including 2601 persons identified with AUD in the previous 2 years (1.0% of all persons with AUD; 80.0 per 100 000 person-years). Unadjusted and fully adjusted IRRs for suicide associated with AUD were 8.15 (95% CI 7.86–8.46) and 2.22 (95% CI 2.11–2.34) respectively (Table 2). Of these deaths, 1623 (62.4%) were reported as intentional and 978 (37.6%) as of undetermined intent. The fully adjusted IRRs for intentional death or death of undetermined intent associated with AUD were 1.74 (95% CI 1.63–1.85) and 4.65 (95% CI 4.13–5.24) respectively. In addition, AUD was associated with a >3-fold risk of non-fatal intentional injury and >1.6-fold risk of non-fatal injury of undetermined intent (Table 2, adjusted model 2).

Table 2 Associations between alcohol use disorder and suicidal behaviours, 2002–2015, Sweden

AUD, alcohol use disorder; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

a. Adjusted for age, gender, marital status and education.

b. Additionally adjusted for drug use disorders, affective disorders, anxiety/phobia disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders and other psychiatric disorders.

Healthcare utilisation prior to suicide

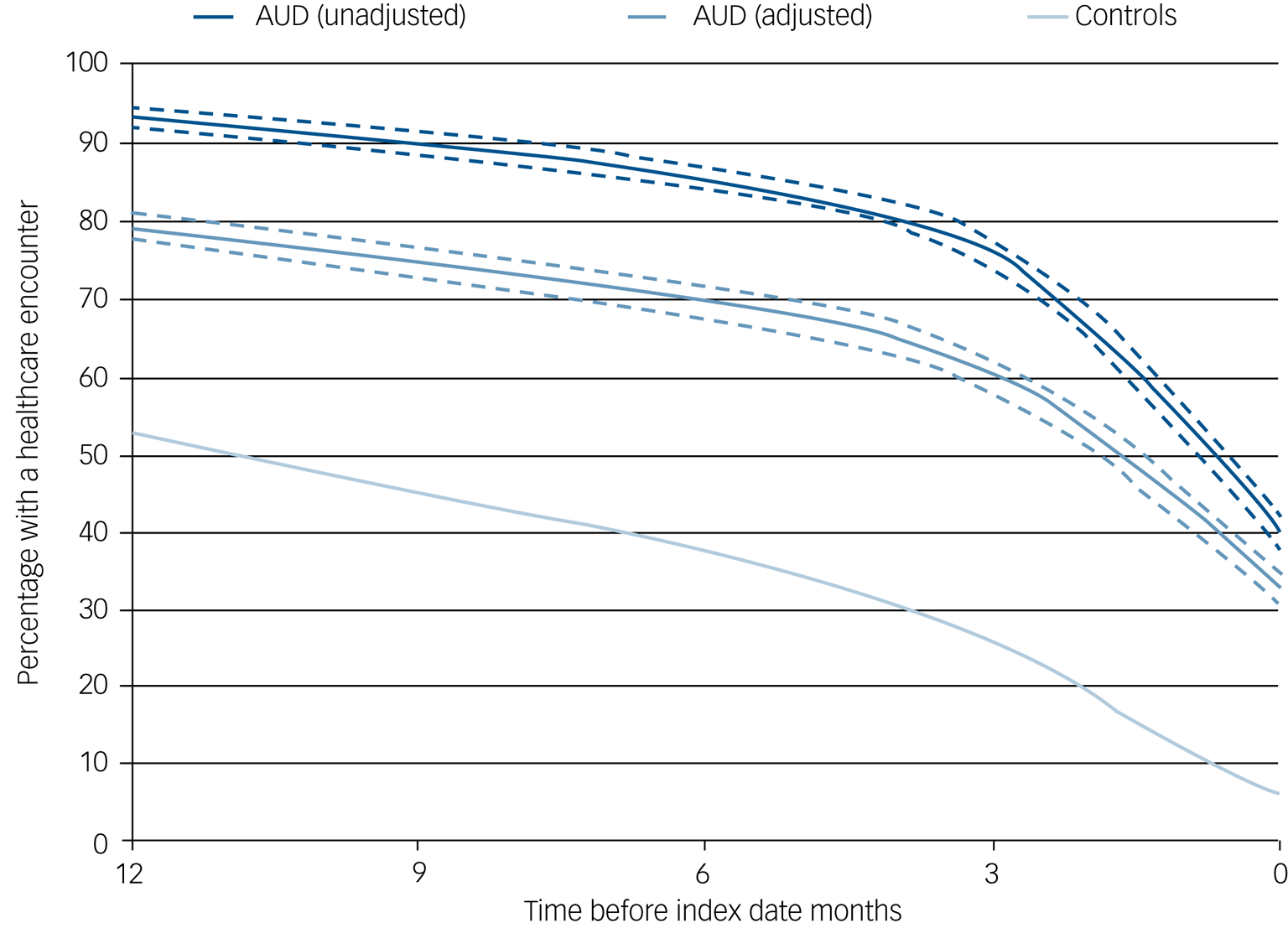

In the nested case–control analysis, persons with AUD were substantially more likely than controls to have had a healthcare encounter within each time interval before the index date (Table 3). For example, 39.7%, 75.6% and 93.0% of those with AUD who died by suicide had a healthcare encounter within 2 weeks, 3 months or 1 year of the index date respectively, compared with 6.3%, 25.4% and 51.8% of controls (adjusted PR and PD, <2 weeks: PR = 3.86 (95% CI 3.50–4.25), PD = 26.4 (95% CI 24.2–28.6); <3 months: PR = 2.03 (95% CI 1.94–2.12), PD = 34.9 (95% CI 32.6–37.1); <1 year: PR = 1.44 (95% CI 1.40–1.47), PD = 27.2 (95% CI 25.5–28.9)). Figure 1 shows the backward cumulative prevalence (and 95% CIs) for healthcare encounters within a given time interval before the index date for persons with AUD compared with controls.

Table 3 Prevalence of healthcare encounters among persons with alcohol use disorder and controls within specific time intervals before index date

a. Adjusted for age, gender, marital status, education, drug use disorders, affective disorders, anxiety/phobia disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders and other psychiatric disorders. All P < 0.001.

Fig. 1 Backward cumulative prevalence of a healthcare encounter within a given time interval before index date among persons with alcohol use disorder compared with controls. Dashed lines show 95% CIs.

Separate analyses of intentional deaths and deaths of undetermined intent yielded very similar prevalence ratios and differences compared with analyses of these outcomes combined. For example, the adjusted PR and PD for a healthcare encounter within 2 weeks of the index date were PR = 3.95 (95% CI 3.49–4.47) and PD = 26.4 (95% 23.7–29.2) for intentional deaths, and PR = 3.76 (95% CI 3.20–4.42) and PD = 26.6 (95% CI 22.9–30.3) for deaths of undetermined intent, compared with PR = 3.86 (95% CI 3.50–4.25) and PD = 26.4 (95% CI 24.2–28.6) for these deaths combined (Table 3).

Supplementary Table 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.122, reports the setting and primary diagnosis for last healthcare encounters within 2 weeks or 1 year of suicide among participants with AUD. Among 1032 encounters at <2 weeks, 23.1% were hospital admissions, 28.9% were in specialty clinics and 48.1% were in primary care. Among all out-patient encounters (either specialty or primary care), the majority (55–61%) were for non-psychiatric and non-injury-related medical diagnoses and <12% were for AUD. Overall similar patterns were found for last encounters within 1 year of suicide (supplementary Table 1).

A sensitivity analysis in which AUD was assessed on the basis of any lifetime history (rather than the previous 2 years) yielded slightly lower PRs but the overall conclusions were not substantially changed. For example, the fully adjusted PR for a healthcare encounter <2 weeks before suicide was 3.58 (95% CI 3.33–3.84) compared with 3.86 (95% CI 3.50–4.25) in the primary analysis, and for <1 year before suicide was 1.34 (95% CI 1.31–1.36) compared with 1.44 (95% CI 1.40–1.47) in the primary analysis.

Interactions

Interactions were explored between AUD and gender in relation to healthcare encounters <2 weeks before the index date (supplementary Table 2). Among controls, men had a slightly lower prevalence of an encounter than women (5.7% v. 8.0%; adjusted PR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.71–0.87). However, comparing controls with participants with AUD, this prevalence increased from 8.0% to 44.7% among women (adjusted PR = 3.05, 95% CI 2.64–3.52) and from 5.7% to 38.1% among men (adjusted PR = 4.19, 95% CI 3.75–4.63). The relatively greater change among men resulted in significantly positive additive and multiplicative interactions (i.e. the combined effect of AUD and male gender on the likelihood of an encounter exceeded the sum or product of their separate effects; P = 0.01 and P<0.001 respectively). The positive additive interaction indicates that AUD accounted for more healthcare encounters within 2 weeks of suicide among men than among women.

Interactions also were explored between AUD and age (supplementary Table 3). Among participants with AUD with a healthcare encounter <2 weeks before suicide, 12.0% were aged <35 years, 75.7% were 35–64 years and 12.3% were ≥65 years (median, 51.4 years). The prevalence of a healthcare encounter increased with age among controls (from 3.6% to 8.2%), whereas participants with AUD had a much higher overall prevalence that did not vary by age (39–40% for each group). A positive multiplicative interaction was noted between AUD and younger ages (<35 years), and a negative multiplicative interaction between AUD and older ages (≥65 years) (P = 0.03 and P < 0.001 respectively). However, no additive interactions were found, suggesting that AUD accounted for similar numbers of additional encounters among younger or older adults compared with those in mid-adulthood.

Discussion

In this large national cohort, AUD was a strong independent risk factor for completed suicide, which was often shortly preceded by healthcare encounters, especially in primary care or specialty out-patient settings. Of persons with AUD who died by suicide, 39.7%, 75.6% and 93.0% had a healthcare encounter within the previous 2 weeks, 3 months or 1 year respectively, percentages that were significantly higher than among controls. Furthermore, AUD accounted for more encounters within 2 weeks of suicide among men than women, despite fewer encounters among men in the general population. Approximately half of all encounters within 2 weeks of suicide were in primary care clinics, and the majority of those were for non-psychiatric diagnoses.

Comparison with other research

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine healthcare utilisation patterns prior to suicide in persons with AUD in a large population-based cohort. A US study of 3132 male military veterans with any substance use disorders reported that 25.4%, 55.6% and 75.9% had a healthcare encounter within 7, 30 or 90 days of suicide, but did not include a comparison group or assess this separately in those with AUD.Reference Ilgen, Conner, Roeder, Blow, Austin and Valenstein17 Other studies have explored healthcare utilisation more broadly in general populations. The largest of those include a Danish study of 11 191 persons who died by suicide and 55 955 controls, which reported that 83% and 32% had a primary care encounter within 1 year or 1 month of the index date respectively, compared with 76% and 19% among controls.Reference Pedersen, Fenger-Gron, Bech, Erlangsen and Vestergaard11 A South Korean study of 11 523 persons who died by suicide also reported high prevalences of healthcare utilisation (81% in men, 91% in women) within 1 year of suicide, and increasing frequency during the final 3 months.Reference Cho, Kang, Moon, Suh, Ha and Kim13 A US study of 5894 persons who died by suicide reported that 83% received healthcare in the previous 1 year, and 55% did not have a psychiatric diagnosis.Reference Ahmedani, Simon, Stewart, Beck, Waitzfelder and Rossom12 A UK chart review study of 247 primary care patients who died by suicide also reported significant heterogeneity in healthcare utilisation across different psychiatric disorders.Reference Pearson, Saini, Da Cruz, Miles, While and Swinson14 However, these patterns have not previously been examined specifically in patients with AUD.

These patterns are clinically important because of the high prevalence of AUD and its known suicide risks. AUD is among the most common mental disorders, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5%, and even higher in high-income (8.4%, 95% CI 8.0–8.9) or upper-middle-income (5.4%, 95% CI 5.0–6.0) countries.1–Reference Carvalho, Heilig, Perez, Probst and Rehm3 AUD is also one of the strongest reported risk factors for suicidal behaviour.Reference Darvishi, Farhadi, Haghtalab and Poorolajal4–Reference Crump, Sundquist, Sundquist and Winkleby9 A meta-analysis of 33 cohort studies reported nearly 10-fold risks of completed suicide in adult men and women with AUD compared with the general population (standardised mortality ratio, 979, 95% CI 898–1065).Reference Wilcox, Conner and Caine7 A more recent meta-analysis of 31 studies with 420 732 participants reported pooled odds ratios of 3.13 (95% CI 2.45–3.81) for suicide attempt and 2.59 (95% CI 1.95–3.23) for completed suicide associated with AUD.Reference Darvishi, Farhadi, Haghtalab and Poorolajal4 A Swedish cohort study of 7.1 million adults who overlapped with the present cohort found >4-fold risks of completed suicide associated with AUD in either men or women, even after adjusting for depression, other psychiatric disorders and somatic disorders.Reference Crump, Sundquist, Sundquist and Winkleby9

In the present study, persons with AUD had more than a threefold higher prevalence of healthcare encounters <2 weeks before suicide compared with the background prevalence. Furthermore, AUD accounted for more such encounters among men, and similar numbers among younger or older adults compared with those in mid-adulthood. Most of these encounters were for non-psychiatric diagnoses. These findings provide further evidence to support universal screening of patients for suicidality and its major risk factors, including depression and AUD. Prior studies have shown that clinical interventions to prevent suicide are effective but remain underutilised.Reference Hofstra, van Nieuwenhuizen, Bakker, Ozgul, Elfeddali and de Jong25,Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas26 Brief screening for depression, AUD and suicidality is clinically feasible, effective and can be administered by medical assistants.Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova and Oquendo27–Reference Babor, Del Boca and Bray31 Positive screens should trigger further discussion with the clinician and prompt psychiatric follow-up.Reference Bauer, Chan, Huang, Vannoy and Unutzer32 Healthcare settings that lack a system to follow up positive screens should prioritise the development of such a system to provide effective care for mental health and suicidality.Reference Coffey33

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of the present study was the ability to examine healthcare utilisation patterns using nationwide in-patient and out-patient (including both specialty and primary care) data. This design minimises potential selection or ascertainment biases, enabling more robust estimates based on a national population. AUD was ascertained using not only nationwide diagnoses but also alcohol-related convictions, thus improving ascertainment with data that are independent of the healthcare system. The results were controlled for sociodemographic factors and other psychiatric disorders, which also were ascertained using highly complete nationwide data.

This study also had several limitations. First, although it included primary care encounters, they were not available with complete nationwide coverage. The Swedish Primary Care Registry had approximately 45% coverage of the national population in 2001, which increased to 75% by 2008 and onward.Reference Sundquist, Ohlsson, Sundquist and Kendler20 Primary care encounters are therefore underreported in the present study and their estimated proportion of all encounters should be considered a lower bound. Second, as in other population-based studies, the reporting of suicides involves some misclassification. However, available data on intentional deaths as well as deaths of undetermined intent enabled separate analyses of these outcomes, which showed little difference in healthcare utilisation patterns. Third, generalisability to other populations with different socioeconomic contexts and healthcare systems is uncertain. These findings will need replication when possible in other countries and diverse populations.

Clinical implication

Improved uptake of screening and treatment interventions in primary care and specialty out-patient settings is a high priority for suicide prevention among persons with AUD.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.122.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health (R01 AA027522 to A.E. and K.S.); the Swedish Research Council; and ALF project grant, Region Skåne/Lund University, Sweden. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Data availability

The national registry data on which this study was based were analysed under strict confidentiality agreements with Swedish authorities. For ethical and legal reasons, the supporting data (which come from a large portion of the Swedish population) cannot be made openly available. Further information about the data registries is available from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/.

Author contributions

J.S. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; study concept and design: all authors; acquisition of data: J.S., K.S.; analysis and interpretation of data: all authors; drafting of the manuscript: C.C.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: C.C., J.S.; obtained funding: all authors; approval of the final version to be published: all authors.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.122.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.