Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is a short-term, problem-focused psychosocial intervention. Evidence from randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses shows that it is an effective intervention for depression, panic disorder, generalised anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder (Department of Health, 2001). Increasing evidence indicates its usefulness in a growing range of other psychiatric disorders such as health anxiety/hypochondriasis, social phobia, schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. CBT is also of proven benefit to patients who attend psychiatric clinics (Reference Paykel, Scott and TeasdalePaykel et al, 1999). The model is fully compatible with the use of medication, and studies examining depression have tended to confirm that CBT used together with antidepressant medication is more effective than either treatment alone (Reference Blackburn, Bishop and GlenBlackburn et al, 1981) and that CBT treatment may lead to a reduction in future relapse (Reference Evans, Hollon and DeRubeisEvans et al, 1992). Generic CBT skills provide a readily accessible model for patient assessment and management and can usefully inform general clinical skills in everyday practice.

CBT can be offered as an integrated part of a biopsychosocial assessment and management approach, but there are certain situations in which it should be particularly considered; these are summarised in Box 1.

Box 1 Circumstances in which cognitive–behavioural therapy is indicated

The patient prefers to use psychological interventions, either alone or in addition to medication

The target problems for CBT (extreme, unhelpful thinking; reduced activity; avoidant or unhelpful behaviours) are present

No improvement or only partial improvement has occurred on medication

Side-effects prevent a sufficient dose of medication from being taken over an adequate period

Significant psychosocial problems (e.g. relationship problems, difficulties at work or unhelpful behaviours such as self-cutting or alcohol misuse) are present that will not be adequately addressed by medication alone

What makes CBT so effective?

Effective psychosocial interventions share certain characteristics. They provide: a focus on current problems of relevance to the patient; a clear underlying model, structure or plan to the treatment being offered; and delivery that is built on an effective relationship with the practitioner. CBT is founded on these principles and is essentially a psychoeducational form of psychotherapy. Its purpose is for patients to learn new skills of self-management that they will then put into practice in everyday life. It adopts a collaborative stance that encourages patients to work on changing how they feel by putting into practice what they have learned.

The problem of accessibility to specialist CBT services

Psychological treatments such as CBT are in great demand, but access to psychotherapy services is often limited. Furthermore, the traditional language of CBT is highly technical and often inaccessible to those who have not received a specialised training. This language barrier affects not only our clinical work with patients, but also our ability to share CBT thinking with colleagues in both primary and secondary care. It is not easy to translate into everyday words concepts such as negative automatic thoughts, schemata, dysfunctional assumptions, faulty information processing, dichotomous thinking, selective abstraction, magnification, minimisation and arbitrary inference.

The inaccessibilty of CBT's standard terminology is exemplified in Box 2. This compares some of the classic technical language used in the seminal manual Cognitive Therapy of Depression (Reference Beck, Rush and ShawBeck et al, 1979) with the corresponding terms used in a new CBT model, the Five Areas model, which we describe in this paper. The reading age for the classic CBT language (left-hand column of Box 2) is 17 years (Flesch–Kincaid grade 12). In contrast, the reading age for the terms used in the Five Areas model (right-hand column) is 12.1 years (Flesch–Kincaid grade 7.1). Even a good reading ability is insufficient to enable a patient or a practitioner to make sense of the classic technical concepts: for this they must also have specialised knowledge. The CBT model in its traditional method of delivery (12–16 weekly 1-hour sessions) allows sufficient time for patients to gain this knowledge. Unfortunately, this luxury of time is not usually available in most psychiatric clinics, where 10–20 minute sessions are the norm. It is clear therefore that the model requires adaptation to retain the integrity of CBT as outlined above, but to use a language and format more suitable for non-psychotherapy settings.

Box 2 Comparison of terms in the standard CBT model with those in the Five Areas model

Classic CBT terms Five Areas equivalents

Thinking errors/faulty information processing Unhelpful thinking styles

Negative automatic thoughts (NATS) Extreme and unhelpful thinking

Arbitrary inference Jumping to conclusions

Selective abstraction Putting a negative slant on things

Overgeneralisation Making extreme statements or rules

Magnification and minimisation Focusing on the negative and downplaying the positive

Personalisation Taking things to heart; unfairly bear all responsibility

Absolutistic dichotomous thinking All or nothing (black or white) thinking

A jargon-free model of CBT

The Five Areas approach is a more pragmatic and accessible model of assessment and management that uses CBT (available from the authors upon request). It was originally commissioned by Calderdale and Kirklees Health Authority and is used by a wide range of health care practitioners, including day-hospital- and community-based psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, behavioural nurse therapists, general practitioners, health visitors and practice nurses. The development phase has included extensive piloting of the model and its language in clinical settings to ensure clarity and acceptability of content. Evaluation and feedback by representatives of the various practitioner groups have led to continuous refinement of the model and its content over the past 3 years.

The model aims to communicate fundamental CBT principles and key clinical interventions in a clear language. It is important to recognise that it is not a new CBT approach; rather, it is a new way of communicating the existing evidence-based CBT approach for use in a non-psychotherapy setting. Although our paper and the others planned for the series in APT pay particular attention to presentations with anxiety and depression, the same model of assessment and intervention can be helpfully offered across the range of psychiatric disorders.

The key elements of the Five Areas model

The fundamental principle of CBT is that what people think affects how they feel emotionally and physically and also alters what they do. In depression and anxiety, characteristic changes occur in thinking and behaviour. Thinking becomes extreme and unhelpful – focusing on themes in which individuals see themselves as worthless, incompetent, failures, bad or vulnerable. Behaviour alters, with reduced or avoided activity, and/or the commencement of unhelpful behaviours (e.g. excessive drinking, self-cutting and reassurance-seeking) that worsen the problems.

These two areas, thinking (cognition) and behaviour, form the focus for CBT assessment and intervention.

The C-component of CBT: unhelpful thinking styles

If people are depressed or anxious they often start to think about things in extreme and unhelpful ways. These patterns of thinking are called unhelpful thinking styles and are summarised in Box 3.

Box 3 The unhelpful thinking styles (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001)

People with depressed and anxious thinking tend to show certain common characteristics

They overlook their strengths, become very self-critical and have a bias against themselves, thinking that they cannot tackle difficulties

They unhelpfully dwell on past, current or future problems; they put a negative slant on things, using a negative mental filter that focuses only on their difficulties and failures

They have a gloomy view of the future and get things out of proportion; they make negative predictions about how things will work out and jump to the very worst conclusion (catastrophise) that things have gone or will go very badly wrong

They mind-read and second-guess that others think badly of them, rarely checking whether this is true

They unfairly feel responsible if things do not turn out well (bearing all responsibility) and take things to heart

They make extreme statements and have unhelpfully high standards that are almost impossible to meet; they hold rules such as ‘I should/must/ought/have got to …’.

Overall, thinking becomes extreme, unhelpful and out of proportion

Unhelpful thinking styles are important because they tend to reflect habitual, repetitive and consistent thought patterns that occur during times of anxiety or depression. As a result, many everyday situations are misinterpreted. As problems are focused on and blown out of proportion, and their own strengths and ability to cope are overlooked or downplayed, individuals become increasingly distressed. To an extent these unhelpful thinking styles are a normal part of everyday life. At one time or another most of us can recognise experiencing at least some of these thinking styles. Usually, when people are not feeling low or are only mildly distressed, they can modify and balance this type of thinking fairly easily. However, during times of greater anxiety or depression these unhelpful thinking styles become more frequent, last longer, are more intense, more intrusive, more repetitive and more believable (Reference Williams, Watts and MacleodWilliams et al, 1997: pp. 72–105, 107–133). As a result, more helpful (balanced) thoughts are crowded out. Helping the patient to notice these unhelpful thinking patterns is an important first step in the process of change and this will be the focus of a later paper in this series (Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams & Garland, 2002).

Such thinking styles are so unhelpful because of the effect that believing them has on how people feel and on what they do. Consider the links between the different situations, thoughts, feelings and behaviour shown in Table 1. From time to time these fears and negative predictions are correct: sometimes we won't enjoy a party, a medication will be ineffective and someone may well not like us. However, during times of depression or anxiety people become overly prone to misinterpret almost everything in such ways – nothing will be enjoyed, nothing will make any difference and no one at all likes them. Extreme and unhelpful thinking can become part of the problem by worsening how people feel emotionally and physically and causing them to act in ways that add to their problems.

Table 1 The links between events, thoughts, emotional and physical feelings, and behaviour

| Situation, relationship or practical problem | Altered thinking | Unhelpful thinking style | Altered emotions and physical symptoms | Altered behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| You are asked to a party | ‘It will be terrible. I won't have anything to say.’ | Jumping to the worst conclusion | Anxiety, physical symptoms of arousal | You don't go (avoidance) |

| You are feeling depressed and your general practitioner prescribes an antidepressant medication | ‘It won't make any difference to how I feel.’ | Negative prediction about the future | Leave feeling even more depressed; noticeable drop in energy from despondent feelings | You take the script but don't pick up the medication |

| While speaking to someone you worry what she thinks of you | ‘She dislikes me and thinks I'm an idiot.’ | Mind-reading and second-guessing how others see you | Anxiety, physical symptoms, including going red and feeling hot and sweaty | You avoid eye contact as you talk and bring conversation to an abrupt end; you avoid speaking to her again; you isolate yourself |

The B-component of CBT: altered behaviour

Reduced activity/avoidance

When people feel depressed or anxious, it is normal for them to experience difficulty doing things. In depression, this reduced activity may be because of: low energy and tiredness; negative thinking and reduced enthusiasm for doing things; low mood and little sense of enjoyment or achievement when things are done; and a feeling of guilt and belief that they do not deserve any pleasure. Anxiety may also cause people to reduce what they do. In this case they tend to avoid doing certain things or going into particular places – for example speaking out loud when others are around, going into a large shop or on a bus, or meeting members of their university tutorial group.

A vicious circle may result, where the reduced or avoided activity exacerbates the feelings of depression and anxiety. In CBT, vicious circles are seen as the main mechanism by which current illness is maintained, and the goal of CBT is to identify and break any that are part of the present problem. Inherent in this approach is the belief that all elements of the vicious circle represent symptoms that maintain the problem. You will find out more about how to identify and break these vicious circles in Garland et al (2002).

Unhelpful behaviours

When people become anxious or depressed, it is normal for them to alter their behaviour to try to improve how they feel. This altered behaviour may be helpful (positive actions to cope with their feelings) or unhelpful (negative actions that block their feelings); examples of such actions are given in Box 3. All of these actions may further worsen how they feel by undermining self-confidence and increasing self-condemnation as negative beliefs about themselves or others seem to be confirmed. Again a vicious circle may result, where the unhelpful behaviour exacerbates the feelings of anxiety and depression, thus maintaining them.

Bringing things together: the Five Areas model

We have so far looked at two important aspects of human experience that alter during times of anxiety and depression – thinking and emotional feelings – but other areas are also affected. The Five Areas model, as its name suggests, focuses on five of these:

-

1 life situation, relationships and practical problems

-

2 altered thinking

-

3 altered emotions (also called mood or feelings)

-

4 altered physical feelings/symptoms

-

5 altered behaviour or activity levels.

Box 4 Helpful and unhelpful behaviours

Helpful behaviours

Going to a doctor or health care practitioner to discuss what treatments may be of help

Reading or using self-help materials for anxiety or depression

Maintaining activities that provide pleasure such as meeting friends, doing hobbies, playing sport or going for a walk

Unhelpful behaviours

Misusing alcohol or drugs

Seeking excessive reassurance

Anxiety-reducing behaviours that are ultimately self-defeating (‘safety behaviours’), e.g. never going out unless accompanied by someone else

Going on a spending spree to buy new clothes or goods in order to cheer themselves up (‘retail therapy’)

Harming themselves (e.g. cutting or scratching their bodies or taking an overdose of tablets)

Pushing family and friends away (e.g. through rudeness)

Becoming very promiscuous

Actions designed to set themselves up to fail and push others away

The assessment model based on these five domains provides a clear structure within which to summarise the range of problems and difficulties faced by people expriencing anxiety and depression. A Five Areas assessment enables detailed examination of the links between each area for specific occasions on which the patient has felt more anxious or depressed. This use of the model is examined in greater detail by Wright et al (2002). Future papers in this series will tell you more about the style of treatment offered in CBT, how to ask effective questions, the sequencing of questions to bring about change and experiments and plans that the patient can use to bring about change.

Using the model in assessment

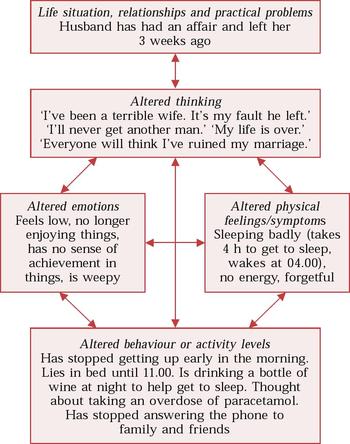

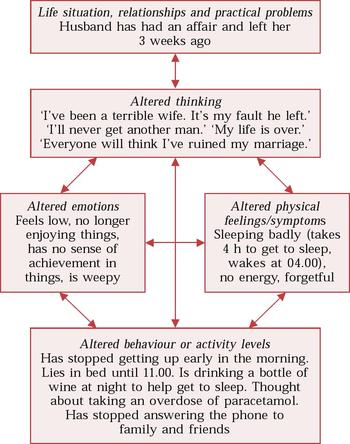

Figure 1 shows a Five Areas assessment of a 40-year-old married woman called Joan, who has recently experienced a relationship split. The assessment clearly reveals that what she thinks about her situation affects how she feels physically and emotionally, and also alters what she does (her behaviour and activities). Each of the five areas affects the others.

Fig. 1 A Five Areas assessment of Joan Smith, a 40-year-old married woman

Area 1: Situation, relationships and practical problems

Many of our patients are facing practical problems, and the actions of people around them can create upsets and difficulties. Such problems may include the following.

Checklist

-

• Debts, housing or other difficulties

-

• Problems in relationships with family, friends, colleagues, etc.

-

• Life events such as deaths, redundancy, divorce, court appearance.

Area 2: Altered thinking

The various unhelpful thinking styles referred to earlier can occur in anxiety and depression and in other psychiatric disorders. Anxious and depressed thinking shows certain common characteristics, as previously summarised in Box 3, and is the focus of the next paper in this series (Reference Wright, Williams and GarlandWright et al, 2002).

Area 3: Altered emotions

The following checklist gives commonly occurring mood states as described by patients.

Checklist

-

• Low mood, depression, sadness, feeling ‘blue’, ‘down’, ‘fed-up’, ‘hacked off’

-

• Feeling flat or numb, or with no capacity for enjoyment or pleasure

-

• Anxiety, worry, stress, fear, panic, ‘hassled’

-

• Guilt

-

• Angry or irritable

-

• Shame or embarrassment.

Area 4: Altered physical symptoms

The physical changes that occur in depression and in anxiety differ.

Checklist

Depression:

-

• Altered sleep (waking earlier than usual, difficulty getting to sleep, disrupted sleep pattern)

-

• Altered appetite (increased or decreased)

-

• Altered weight (increased or decreased)

-

• Reduced concentration and memory deficits

-

• Reduced energy, tiredness, lethargy

-

• Reduced sex drive

-

• Constipation

-

• Pains, physical agitation/restlessness.

Anxiety:

-

• Restlessness and inability to relax

-

• Awareness of physical tension in their muscles, with aches, pains or tremors (‘tense, wound-up’)

-

• Shakiness or unsteadiness on their feet

-

• A feeling of being physically drained and exhausted

-

• Feeling sick, with a churning stomach, ‘butterflies’, reduced appetite

-

• Finding it difficult getting off to sleep

-

• Feeling hot, cold, sweaty or clammy

-

• Awareness of a racing heart and/or overbreathing, with rapid, gasping breaths

-

• Awareness of a muzzy-headed (depersonalised) feeling

-

• Pins and needles/tingling sensations/tight chest.

Area 5: Altered behaviour

Identifying reduced activity in depression

A useful question to help identify reduced activity is ‘What things have you stopped doing since you started feeling depressed?’ This can reveal inactivity, social withdrawal and putting activity off (procrastination).

Checklist

Has the person begun to:

-

• Stop meeting friends?

-

• Reduce socialising/going out/joining in with others?

-

• Reduce hobbies/interests?

-

• Reduce pleasurable things in life?

-

• Find that life is becoming emptier?

-

• Reduce activities of daily living (self-care, housework, eating, etc.)?

Identifying areas of avoidance in anxiety

The question to ask is ‘What things have you stopped doing since you started feeling anxious?’

Checklist

-

• Are there situations, people or places that they are avoiding?

-

• Is there anywhere they cannot go or anything they cannot do because of their anxiety?

-

• What would they be able to do if they were not feeling anxious?

Identifying unhelpful behaviours

A useful question to help identify unhelpful behaviours is ‘What things have you started doing to cope with your feelings of anxiety and/or depression?’

Checklist

Are they:

-

• Seeking reassurance?

-

• Only going out/going to certain places when accompanied by other people (safety behaviour)?

-

• Misusing alcohol or illegal drugs?

-

• Misusing medication?

-

• Withdrawing from others?

-

• Actively pushing others away?

-

• Comfort-eating?

-

• Harming themselves in some way as a means of blocking how they feel?

Why go through this process?

You will probably find that you already routinely asking most of the questions in the Five Areas assessment that have been identified above. The Five Areas model merely structures the information differently from the traditional psychiatric or medical model. Note that the Five Areas model is described as an assessment model, and the purpose of this assessment is to inform treatment.

There are two main reasons for working with the patient to identify problems in each of the five areas. First, this is helpful for us as practitioners. It aids our understanding of the impact of depression or anxiety on the patient's subjective experience. It also enables us to identify clear target areas for intervention: making changes in any one of these areas leads to change in other areas as well (this is a direct implication of the vicious circle model).

Second, it is helpful for our patients. A Five Areas assessment is easily understood by patients and it helps them to develop an understanding of the effect that depression and anxiety have on them. The process of writing down their symptoms is helpful in its own right and can enable patients to look at these more objectively – it can provide a degree of emotional distance from their experiences. Encouraging patients to consider depression and anxiety as a set of interrelated problems that affect various areas of their lives can lead to very important insight as they recognise that hitherto seemingly unconnected and diverse symptoms are in fact all different aspects of anxiety or depression.

Explaining maintenance of the disorders

The Five Areas model offers a useful way of accounting for the maintenance of anxiety and depression. Regardless of their original cause, they can be kept going or even intensified by the unhelpful thinking styles and altered behaviour that they engender and that become part of the problem. A Five Areas assessment gives a summary of the difficulties currently experienced by a patient who is depressed or anxious. It does not argue that unhelpful thinking and behavioural changes play a causal role in anxiety or depression. Rather, it takes a pragmatic, multi-factorial stance regarding their origins, which include life events, hereditary factors, changes in brain neurochemistry, and vicarious learning from and modelling on important others such as family members and friends.

Putting into practice what you have learned

The time we spend in formal sessions with our patients is only a very small part of their week. We consequently urge them to put into practice in their everday life what they have learned with us. Perhaps the same principle can be helpfully applied to our own learning of CBT skills. We therefore encourage you to apply elements of the Five Areas model with some of your patients over the next few weeks. This will allow you to find out how useful (or not) the model might be for you and other psychiatric team members. At the beginning of the next article we will include a short section to review how helpful this was in practice.

Two situations in which the Five Areas model might be tried out are during case feedback in multi-disciplinary team meetings and in Care Programme Approach (CPA) meetings. In diagrammatic format (as in Fig. 1) the Five Areas assessment model provides a useful framework for case feedback. It enables relevant features to be recorded on a single sheet so that a concise problem-oriented summary can be presented in only 3–4 minutes for team discussion. The diagram may be used to record key features of assessments carried out by team members using any interview style. The single-sheet summary can also act as both a problem list and a record of interventions offered, making it a useful document in CPA meetings. The summaries could be copied for the clinical record, the patient and key practitioners, thus facilitating communication with the patient and with team and non-team members.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. The following are terms used in the Five Areas assessment model:

-

a selective abstraction

-

b extreme and unhelpful thinking

-

c maximisation

-

d the vicious circle of reduced activity

-

e mind-reading.

-

-

2. The following are unhelpful behaviours that may contribute to the vicious circle of unhelpful behaviour:

-

a pushing family or friends away

-

b stopping going out or meeting people

-

c trying to spend one's way out of depression

-

d acting in a very dependent or reassurance-seeking way

-

e reading self-help materials on anxiety or depression.

-

-

3. Examples of unhelpful thinking styles described in the Five Areas assessment model include:

-

a schemata

-

b jumping to the worst conclusion

-

c negative automatic thoughts

-

d a bias against oneself

-

e having a negative mental filter.

-

-

4. The following are areas in the Five Areas assessment model:

-

a altered behaviour or activity levels

-

b absolutist dichotomous thinking

-

c life situation, relationships and practical problems

-

d altered emotions

-

e altered physical feelings/symptoms.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | F | a | T |

| b | T | b | F | b | T | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | F | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.