After almost four years, the end of our editorship is approaching soon. On June 1st, the new editorial team will take over and immediately start handling all new submissions as well as those still under review. As we near the end, it is only natural that we take a step back and reflect upon our editorial decisions and policies of the past years. We faced many challenges; one we dealt with often concerns rejected authors in times of continuously increasing number of submissions. Even though we increased the absolute number of annually accepted papers from 45 in 2016 to 75 in 2019, the overall acceptance rate remained low (≈6% in 2019). Thus a vast majority of authors still face a negative outcome after submitting to the APSR. Compounding this issue is that we continue to rely on these very authors to review for us.

With regard to our limited pool of reviewers, we compensated the higher number of submissions by increasing the desk rejection rate. Arguably, at first this upsets many of those authors who get desk-rejected; but, it lowered turnaround times, which ultimately allowed them to submit their manuscripts to other journals faster. At the same time, increasing desk rejections also runs the danger of increasing both editor bias as well as the likelihood of rejecting papers which reviewers or the scholarly community would have considered publication-worthy. However, we cannot have all manuscripts reviewed, given the limited reviewer pool, so as editors we have to be cautious not to overload our reviewers with work. In fact, we have stressed the importance of helpful feedback authors receive from our peer review process and even if a paper is ultimately rejected, the review process may nonetheless increase the prospects of publication in other outlets.

This brings us to this issue’s Notes from the Editors in which we take a closer look at manuscripts that were rejected at the APSR.Footnote 1 Specifically, we are interested in whether they were eventually published in one of the two other main generalist political science journals, the American Journal of Political Science (AJPS) and the Journal of Politics (JoP). By doing so, we want shed light on three questions. First, were the editors’ decisions justified based on the recommendations of the reviews the manuscripts received? Second, how do rejected articles perform in comparison to those that we published in terms of their impact in the scientific community? Finally, is there any indication that the review process of the APSR motivates authors to incorporate changes their papers after rejection?

To answer the first question we calculate a score for the combination of a manuscript’s reviewer recommendations. This allows to evaluate whether articles published in the APSR received more positive recommendations compared to those which were initially rejected but later published in AJPS or JoP. Secondly, we focus on the number of citations they receive. Though not perfect, it is a commonly-used measure to assess the quality of and interest in a journal’s publication record. Reflecting on our own decisions, comparing rejected and elsewhere-published articles with APSR’s publications may help us shed light on whether APSR editors and reviewers have been able to detect and publish articles that are of major interest to the discipline. Finally, we compare the textual similarity of the abstracts we desk-rejected and rejected-after-review to those published in AJPS or JoP. Although we cannot measure whether a change of the abstract improved the papers, this comparison can indicate whether and to what extent authors changed their papers when they received reviews or not.

Data for the analysis is taken from our Editorial Manager database. We identified 491 submissions which were rejected by the APSR but were accepted either at the AJPS (N = 231) or the JoP (N = 260).Footnote 2 Interestingly, having a total of 10,344 rejected submissions in our database before December 1st, 2019 corresponds nicely to a share of 4.7% of rejected papers that were still published in one of the two major other generalist political science journals.

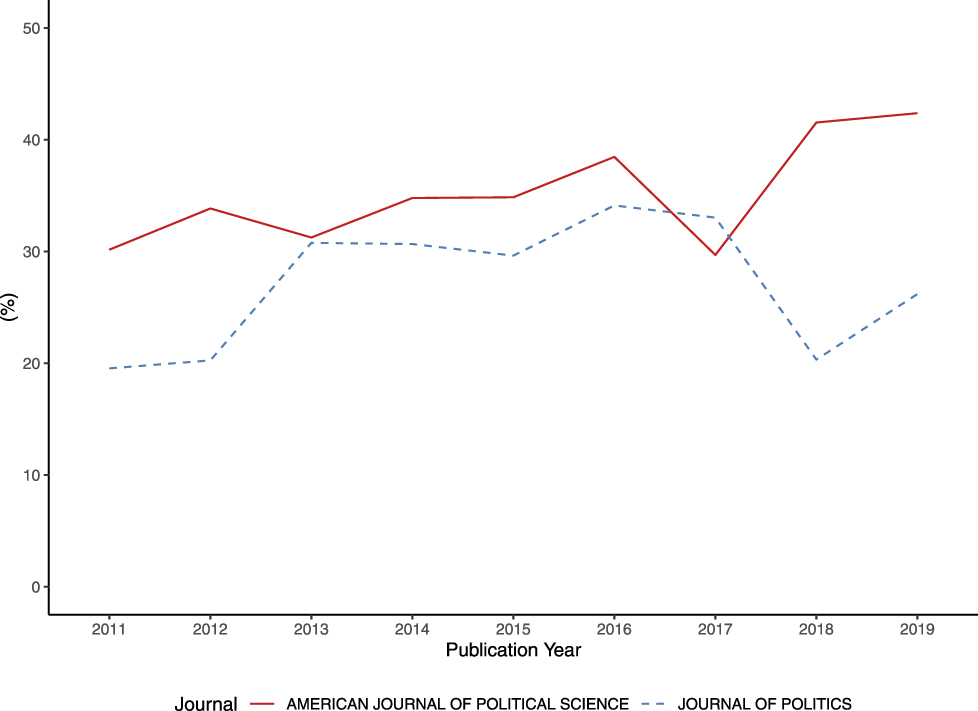

Figure 1 shows the annual share of previously rejected papers among publications both in the AJPS and the JoP since 2011.Footnote 3 The average share is higher in the AJPS (35%) than in the JoP (27%). With the exception of 2017, we observe an increasing trend of rejected papers among publications in the AJPS over time. Keep in mind that the impact factor of the AJPS has also increased in recent years. Broadly speaking, there are two possible interpretations that can follow from this correlation. One, the average quality of submissions that the APSR receives is increasing, making it also more likely that rejected manuscripts not only make it into one of the other top journals, but also contribute to their impact factors. Two, it is an indication of flaws in the review process of the APSR, for example, when our editors and reviewers fail to detect high quality papers which are then published in the other journals (and raise their impact factor after being highly cited while ours declines or increases at a different rate). This may possibly be an unintended consequence of a higher desk rejection rate where less time and fewer people are involved in the decision. The latter interpretation would, however, be worrying for us as editors who aim to identify and publish work of outstanding merit and, therefore, calls for further examination.

FIGURE 1. Share of Previously Rejected Manuscripts Among Publications in the AJPS and the JoP

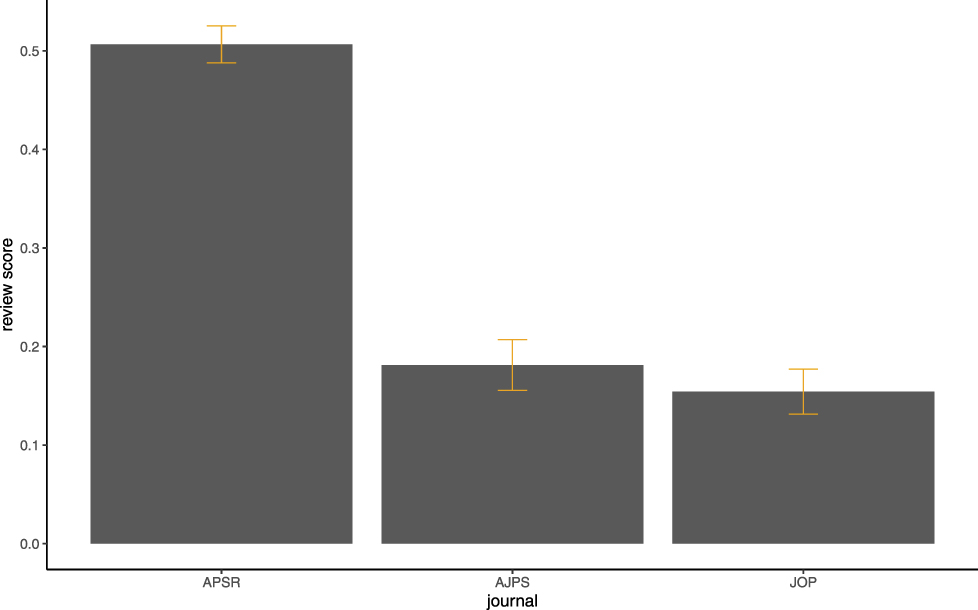

We start by asking whether rejected-after-review manuscripts received more negative reviewer recommendations when handled by our journal. Typically, a manuscript under review receives on average three written reports. Additionally reviewers provide the editors one of four recommendations, accept, minor revisions, major revisions, and reject, which results in various combinations of recommendations given the number of reviews. Following Bravo et al. (Reference Bravo, Farjam, Moreno, Birukou and Squazzoni2018), we calculate a review score based on the first round review recommendations of each manuscript in our sample. The score estimates the “value” of a given combination of recommendations, accounting for the possible set of recommendations that are both clearly better and clearly worse. Being bound between 0 and 1, it allows the comparison of scores for manuscripts which received a different number of reviewers:

Figure 2 shows that the average review score of manuscripts published in the APSR between 2007 and 2019 is more than twice as high as the average score for manuscripts that were rejected and eventually published in either the AJPS or JoP. It is a reassuring finding that our editors’ decisions are not completely random but seem to be based on the reviewer recommendations a manuscript receives.

FIGURE 2. (Optimistic) Review Score (Bounded Between [0, 1]) for Manuscripts that Were Under Review at the APSR and Were Then Either Published in the APSR or Rejected and Later Published at the AJPS or JoP

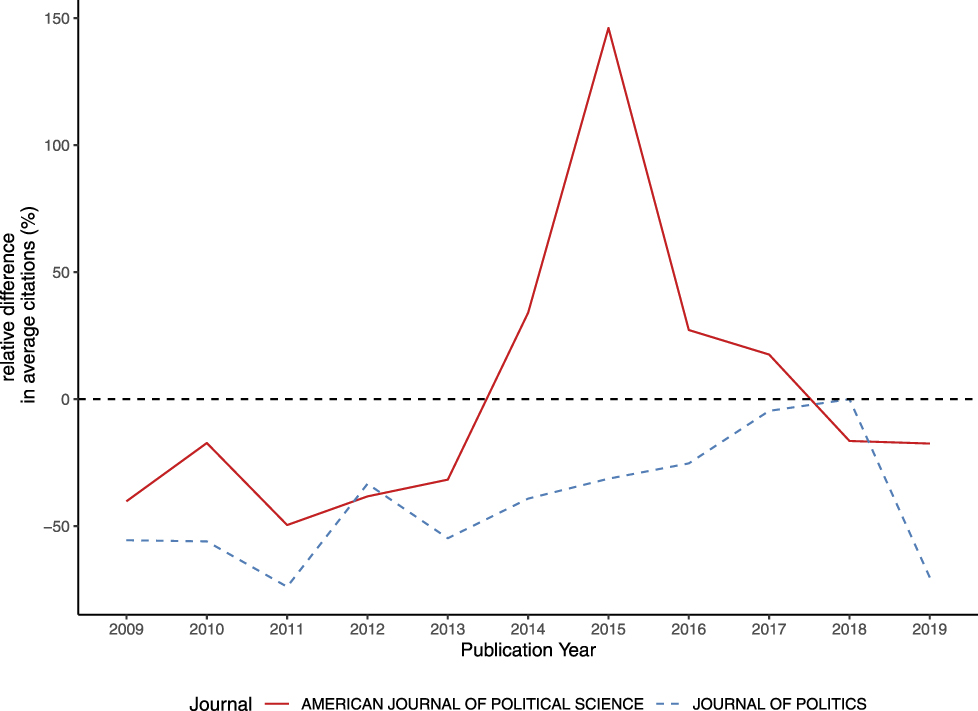

Our second question asks whether the APSR has been rejecting papers which are highly cited in other generalist political science journals. To do so, we calculate the relative difference between the average number of citations that manuscripts published in the APSR receive and those rejected by the APSR but published in the AJPS or the JoP. Figure 3 presents the percentage difference of the relative difference by year of publication. Rejected papers which were published in the JoP are generally less cited than the average APSR publication. In contrast, the AJPS published a number of previously rejected papers between 2014 and 2016 which were cited more than our own publications. What stands particularly out in the chart is the year 2015 when the average number of citations of previously rejected manuscripts was almost 150% higher than the average paper published in the APSR in the same year. Yet, the trend reversed and since 2018 the average APSR publication is again more often cited than rejected papers published in either AJPS or JoP. We carefully interpret this as a sign that APSR editors are able to identify and publish articles that are of generalist interest to our scholarly community.

FIGURE 3. Relative Difference in the Average Number of Citations

Finally, are desk-rejected papers cited less than papers that were rejected after a round of review at the APSR? This is what we would expect if our desk rejection decisions filter out articles that are in fact of less interest to our discipline or provide a smaller, more field-specific contribution. For this analysis, we focus on manuscripts that were solely handled by our editorial team since we took over on August 26, 2016 (the first issue under full responsibility of our team decisions was published in February 2018). Comparing the average number of citations of the 55 papers which were later published in the AJPS or JoP by the decision term suggests that we did not desk reject manuscripts that were more cited than those which were sent out for review. The average number of citations of desk-rejected manuscripts published in the AJPS or JoP is 0.6, while it is on average 1.4 citations for manuscripts that received feedback. While being suggestive, we take these numbers as another indication that our editorial policy worked and we do not make unjustified decision with respect to our desk rejections—at least on average.

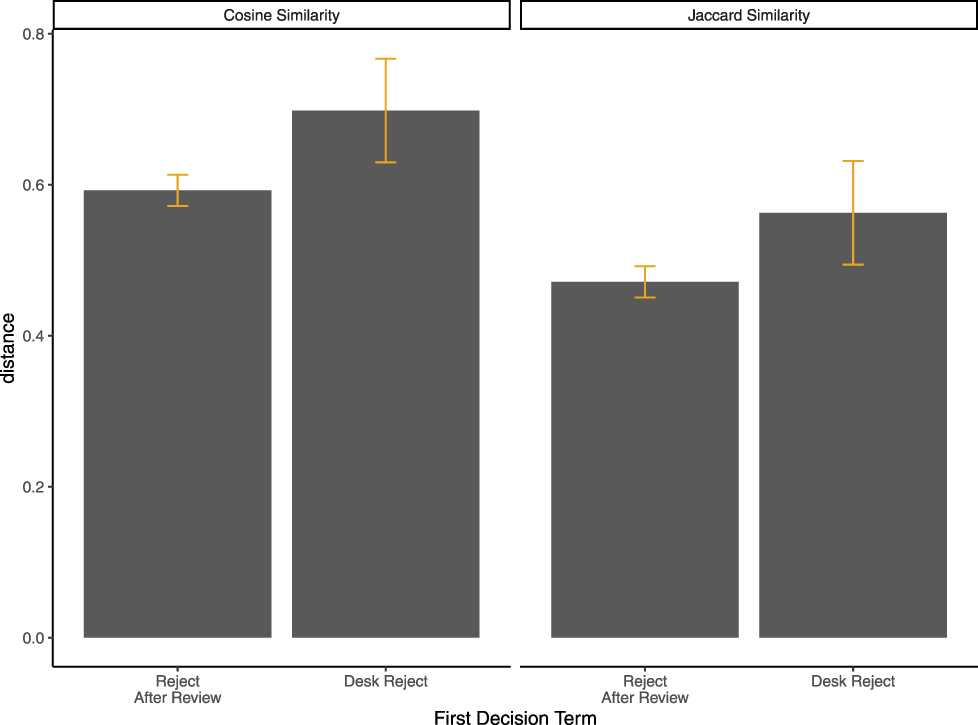

Another question is whether our review process impacts the papers, which were rejected at the APSR and later published in other generalist political science journals. To answer this question we compare the abstract of desk-rejected manuscripts with those rejected-after-review by the APSR to the one of the same manuscript after it was published in one of the other two generalist journals. From our experience, one of the main reasons why reviewers refrain from recommending publication in the APSR is the lack of a theoretical or empirical puzzle and, correspondingly, the lack of a convincing frame. Therefore, we focus on the first two sentences of each abstract where the frame and research puzzle is typically stated. For comparison, we calculate two text similarity metrics, the Cosine similarity and Jaccard similarity.Footnote 4 As shown in Figure 4, the text similarity of abstracts is higher for desk-rejected manuscripts than for manuscripts that were rejected-after-review, regardless of the measure. Put differently, the first two sentences of published abstracts differ on average more between the abstracts when it rejected at the APSR after being sent out for review. It may be an indication that the review process in the APSR helps authors to re-structure and re-frame their manuscripts as we have suggested in previous Notes from the Editors.

FIGURE 4. Text Distance of the First Two Sentences Between Abstracts of Manuscripts Previously Rejected at the APSR and Then Published in the AJPS or JoP

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.