In January 1775, Johann Gottlieb Bärstecher (1749–after 1802) began publishing a newspaper in Kleve dedicated to the theatrical arts. His Theater-Zeitung was designed to help ‘compensate for the lack of a central German stage’, something he believed the ‘patriot who values German theatre’ would support.Footnote 1 Bärstecher elucidated that with his journal

the director has before him a critical index of the newest products for the stage; he will select the best ones … ; the actor receives treatises on aspects of his art, perhaps also encouragement to read his name in a newspaper that is everywhere, will reach every troupe, and want to ponder praise and criticism precisely; finally, the enthusiast can entertain himself not only with dramatic and critical news, but also poems and anecdotes if he prefers the tone of paperbacks and newspapers.Footnote 2

In combining systematic information, professional guidance, and lay content, the paper had the ability to connect theatre practitioners and audiences from across an expansive realm in a single space. Yet the newspaper could only achieve this if correspondents from far and wide regularly sent reports to Kleve and if it was able to reach areas well beyond the city’s boundaries once published. Bärstecher was keenly aware of this. He later wrote to a friend: ‘I have … come to an agreement with the Imperial Post under the guarantee of the Prince of [Thurn und] Taxis that allows me to send free of postage the next instalment of the Theater-Zeitung throughout the entire Holy Roman Empire.’Footnote 3 This was no small feat, as postage-free shipping was typically reserved for the most important imperial missives.Footnote 4

The Thurn und Taxis family began operating Europe’s first systematic postal network in the late fifteenth century.Footnote 5 In so doing, they helped to connect Spain, the Spanish (later Austrian) Netherlands, and the expansive Empire in the centre of Europe. A kaleidoscopic realm of hundreds of territories, the Holy Roman Empire (or Reich) had necessitated the development of this information network, as it afforded rulers the ability to communicate efficiently with administrators in distant and discontiguous territories.Footnote 6 Around a century later, the Thurn und Taxis were made postmaster generals of the Imperial Post and were entrusted with conveying ‘the outgoing dispatches of the Emperor, Imperial Chancellor, Imperial Vice-Chancellor, Imperial and Privy Councilors of the Court, and other such high officers without tax or letter fees’.Footnote 7 So crucial was the postal service to the political stability of the Reich that emperors elevated the Thurn und Taxis to barons (1608), made the position of postmaster general a hereditary fief (1615), and conferred their status as count (1624) and ultimately prince (1695).Footnote 8 Although the Taxis enjoyed in essence a private monopoly of the Imperial Post, the emergence of territorial rivals – especially during the Thirty Years War (1618–48) – caused disputes but did not hinder the Taxis, who continually expanded their network and struck agreements with local competitors. Available to anyone willing to purchase postage from about 1600, their system of hubs and relays was so effective that the time it took to cross the Empire went ‘from 30 to just 5 days; a speed not surpassed until the spread of railways and electric telegraph in the 1830s’ (see Figure 0.1).Footnote 9 As Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) would recall, ‘the Taxis postal system was reliably swift, the seal secure, and the postage reasonable’.Footnote 10 This centuries-old media empire was the conduit through which many commoners travelled – via post carriages – and through which most written communication was disseminated, including journals like Bärstecher’s, the written reports sent to him, and the musical performances and materials discussed in them.Footnote 11 Travelling along ancient roads, people and their material objects criss-crossed the Empire one coach house at a time. At these important hubs, coachmen and riders would be changed, letters sorted, and fresh horses hitched to the wagons. Meanwhile, weary travellers could seek refreshment and overnight accommodation. They could even attend the theatre offered at the inn next to the coach house.

One inn where theatre was performed was Das goldene Kreuz in Regensburg, at once the home of the Holy Roman Empire’s Reichstag and the Thurn und Taxis.Footnote 12 As an Imperial City, Regensburg did not have a ruling prince. Yet that did not stop the Taxis, who had nevertheless attempted to act as one ever since establishing their primary residence there in 1748, when the prince was again made principal commissioner – the emperor’s representative to the Reichstag – owing to the family’s service as postmaster generals.Footnote 13 Charged with communicating the emperor’s decisions, protecting his interests, and overseeing the ceremonial protocol of this assembly, the principal commissioners played a significant role in the political life of the city and Empire. They also shaped Regensburg’s cultural life. To entertain ambassadors during Reichstag sessions, the Thurn und Taxis rented the theatre building from the city magistrate and fashioned it into a Hoftheater that staged French (1760–74), Italian (1774–8), German (1778–84), and again Italian (1784–6) music and theatre.Footnote 14 The chronological favouring of different theatrical traditions followed those supported by the emperor and were designed to project the Taxis’s political power before an imperial audience.Footnote 15 Above all others, the Taxis Italian opera fused the spectacle of politics and theatre, for performances were held on the same evenings as Reichstag meetings.Footnote 16 The price of attending the prince’s theatre was the acceptance of his cultural agenda: those deemed worthy to attend were invited at his expense.Footnote 17 Yet the interrelation of political and cultural institutions was not always advantageous and not always appreciated. Having closed the German theatre and re-established his Italian opera, Prince Carl Anselm of Thurn und Taxis (1733–1805) began losing control of his audience in 1784. His decision incited a contingent of Reichstag ambassadors to organize a German-language ‘opposition theatre’ that was to be free from the prince’s cultural influence.Footnote 18

Carl Anselm should have seen it coming. When Friedrich Nicolai (1733–1811) visited the city a few years earlier, he compared the physical state of the Reichstag with that of Das goldene Kreuz, leading him to accuse ambassadors of caring more about their entertainment than ‘the common good of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation’.Footnote 19 Indeed, not only did diplomats prefer German theatre, but – perhaps motivated by political reasons as much as cultural ones – a group of dissatisfied ambassadors also went as far as to boycott Carl Anselm’s Italian opera.Footnote 20 On 16 July 1786, Carl Anselm expressed his frustration and warned the ambassadors diplomatically about the continued popularity of their theatre:

His Highness is well aware that several of these ambassadors enjoyed [the Italian opera], others have shown indifference, [while] few others expressed no amusement[.] Among the latter were those who had initially very much praised the Italian opera and deprecated the German theatre but afterwards changed their opinion[. This] is proof to his Princely Highness that, to his regret, it is not possible to please everyone, even with the best intentions. His Highness also maintains [unreadable] that the excellent ambassadors’ position is not to replace the Italian [opera] by organizing a German theatre, because his Highness is too assured of the intentions of those ambassadors to really believe that they aim to eliminate something in which his Highness finds enjoyment.Footnote 21

Despite the prince’s good intentions of providing for free Italian opera and his tactful admonition (or threat), the enduring success of the German theatre resulted in the dissolution of his court opera. Only days after warning Reichstag officials, Carl Anselm dismissed his Italian actors and dissolved the company.Footnote 22 His decision to do so was not merely because maintaining a court opera was incredibly expensive, as the family’s postal monopoly made them among the wealthiest in the Reich.Footnote 23 Rather, Carl Anselm simply had had enough. The prince now purchased a subscription to see visiting German troupes, as did the other representatives.Footnote 24

The drama unfolding in Regensburg was part of a larger theatrical shift. Beginning in the mid-1770s, courts and civic centres around the Reich had established and hosted German-language theatre companies with increasing frequency. Within a decade, even the most powerful princes who had for years supported Italian and French operas began turning to German theatres for entertainment and to fulfil their cultural and political agendas.Footnote 25 In so doing, they displayed their support of local culture and saved significant sums of money, for German genres could be staged at a fraction of the cost of foreign ones. Indeed, this shift was owing in part to the influence of the public, which now compelled rulers to display fiscal restraint as much as cultural taste and political power.Footnote 26 It is possible that, as the emperor’s representative in Regensburg, Carl Anselm was politically obligated to appear fiscally responsible, and made the best of a precarious situation by fashioning the popularity of the opposition theatre as an excuse to close his own.Footnote 27 But whatever his true motivation, what was clear was that Carl Anselm could not switch between his choice of theatrical spectacle and expect imperial ambassadors to simply accept it as he and they once had. In other words: he no longer controlled what was popular. The rise of the opposition theatre and the Thurn und Taxis’s subsequent abandonment of Italian opera signalled just how much and how quickly attitudes towards German-language music and theatre had changed since the Hamburg Enterprise – considered the first German Nationaltheater – failed after only two years of operation in 1769.Footnote 28

This book is about music for the German-language stage in the twilight years of the Holy Roman Empire. Although these contexts hardly earn a mention in scholarly narratives of music circa 1800, I posit them as crucial towards understanding the world of music and theatre during what has hitherto been labelled the ‘Classic Era’. The Holy Roman Empire was at the heart of political and cultural life in Central Europe for nearly a millennium; although German-language stage music was at the centre of musical life there for a mere fraction of this time, it would shape and dominate its final years. Focusing primarily on the period between 1775 and 1806, I explore the musico-theatrical practitioners, institutions, repertoire, and material objects that networked the Empire and brought music theatre to nearly every corner of its expansive territories. Thus, my task is that of Bärstecher. In a political and cultural domain with no single capital, he set out to share the stories of these theatres in a central space equally useful for the practitioner as the enthusiast. I aim to accomplish the same.

By placing into dialogue scholarship of German music traditions around the year 1800 with recent historical work on the Holy Roman Empire, I argue that this long-marginalized polity helped foster the proliferation of hundreds of German-language theatres that were collectively understood as Nationaltheater. The Empire not only served as the precondition for the rise of such theatres, but also facilitated communication and cooperation between them. Just as the Holy Roman Empire’s disparate territories were bound together by a common imperial political system, so too were its varied theatres linked to one another by a shared musico-theatrical culture. This book thus posits the Holy Roman Empire as a common framework in which German theatres operated and were connected across – and by – vast geographic distances, political boundaries, and musical repertoires.

The ‘Emergence’ of Singspiel, ‘Wandering’ Troupes, and the Nationaltheater

The story of shifting aesthetic preferences towards German music theatre in Central Europe typically goes something like this: in Leipzig, Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–66) sought to reform German theatre.Footnote 29 To do so, he turned to foreign practices. Although Gottsched was a proponent of the French neo-classical style, he was critical of performances of opera staged by the Northern Italian acting companies that crossed the Alps to perform in Leipzig and other German centres during the mid-1700s.Footnote 30 According to Gottsched, opera played no part in a German theatre, as he found both its dramaturgy and the fact it was delivered entirely in song unnatural and irrational. He contended that the ridiculousness of operatic action and continuous singing rendered the display unintelligible and the didactic maxims wasted, for audiences could not grasp what they could not understand.Footnote 31 While intellectuals contemplated practical solutions to Gottsched’s critiques of opera, German civic theatres were forced to close owing to economic difficulties. Lavish opera – including those by dramatist Pietro Metastasio (1698–1782) – as staged at Europe’s most prestigious courts thus remained Central Europe’s principal musico-theatrical genre. But the Seven Years War (1756–63) placed even greater financial constraints on courts and disrupted the tours of Italian opera companies. This allowed German troupes to fill the void. In Leipzig, the company of Heinrich Gottfried Koch (1703–75) began staging a new genre of comic opera known as Singspiel during the 1760s. Dramatist Christian Felix Weiße (1726–1804) and composer Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804) created works for Koch’s troupe that contained dialogue and simple song, while their plots concerned the lives of commoners rather than the mythological and heroic topics commonly found at court. In this regard, Singspiel can be considered a German version of French opéra comique, which similarly comprises spoken dialogue and musical numbers. The music of such early Singspiel abandoned the technical displays of virtuosity characteristic of Italian opera that had attracted much criticism in the 1760s.Footnote 32 This new ‘German’ version of music theatre was practical. Hiller’s music was accessible to a range of performers, as many companies independent of a court could not afford trained, experienced singers. His songs were easily sung by actor and audience-member alike. As Estelle Joubert has argued, the dissemination of songs from Hiller’s Singspiele throughout the public helped to foster a common cultural identity.Footnote 33 The rise of the public sphere – a virtual realm of communication fuelled by print media that emerged as a private social space distinct from the authority of the state – simultaneously began to shift the locus of music production from private courts to public theatres.Footnote 34 Traditional narratives trace these developments – Gottsched’s discourse on Italian operatic models, the court preoccupation with foreign-language opera, the rise of German-language theatres, and the formation of a genre that German actors could perform – from the ‘emergence’ of Singspiel in the mid-1760s throughout the nineteenth century, when German music theatre reached its zenith with the operas of Richard Wagner (1813–83).Footnote 35

Studies of German opera and the theatre companies that performed it often begin precisely at this moment, circa 1765. Thomas Bauman employs Hiller’s works for Leipzig as a point of departure in his history tracing the development of specifically ‘North German opera’.Footnote 36 Focusing on court, touring, and national theatres, Bauman’s work then progresses chronologically to different centres. The study begins in Weimar and Gotha for the early 1770s and moves to Berlin for the latter part of that decade. It then traces a period of ‘lean years’ in the 1780s, until Vienna became the centre of Singspiel production. The book concludes by exploring how Viennese traditions were ultimately assimilated into subsequent North German opera of the 1790s. It seems all too convenient that its locus of Singspiel development ended up in Vienna just in time for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91) and his Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782) and Die Zauberflöte (1791). Bauman’s decision to ultimately tie his study into the canon seems to have been a deliberate choice, as, by the author’s own admission, ‘to counter such received ideas [that German opera is trivial in comparison to Mozart’s operas] by convincing the reader of North German opera’s intrinsic importance in the scheme of eighteenth-century opera as a whole would be a hopeless task, as well as a misguided one’.Footnote 37 If his admission speaks to the anxieties of that moment in dealing with non-canonic repertoires, his pessimism was nonetheless portentous, for scholars have paid little attention since to the music and musicians he explored in the mid-1980s. John Warrack mentions a few of the same lesser-known theatre companies as Bauman in his history of German opera published sixteen years later, for instance, and he too focuses on Vienna at the very same historical moment.Footnote 38

Just under half of all German theatre companies operating around the year 1800 were mobile. And although Bauman and Warrack do explore a few before turning to Vienna, these theatres play almost no part in the story of German opera after this Viennese turn. Despite their role in bringing opera to diverse audiences around Central Europe, travelling companies have been grouped together and cast aside as ‘wandering troupes’ that meandered from place to place constantly in search of new audiences.Footnote 39 Owing to their mobility, they are frequently characterized simultaneously as in fierce competition to stage the best works and as unable to perform music that scholars deem worthy of study.Footnote 40 This paradox – which I will address in this book – means that the few studies of mobile companies that have recently emerged concern only those that had direct links with canonic composers.Footnote 41 Such is the case with the troupe of Pasquale Bondini (c.1737–89) and (later) Franz Seconda (1755–1833) – the subject of recent investigation in connection with Mozart – that performed in Dresden, Leipzig, and Prague, for example.Footnote 42

The proportionally few German theatres labelled ‘Nationaltheater’ receive far more attention by comparison. German national theatres are often traced back to Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–81) and the Hamburg Enterprise.Footnote 43 Such theatres, as institutions and as a concept, feature prominently within investigations of the emergence of a German national consciousness and German opera during the (long) eighteenth century, as they provide a convenient framework in which both operated.Footnote 44 But the danger here is that Nationaltheater – beginning with Hamburg in 1767 – are teleologically positioned as the beginning of a distinct German national operatic tradition that culminated with Wagner and German political ‘unification’ under Prussian hegemony in the later nineteenth century.Footnote 45 For this reason, the impetus behind the foundation of a ‘national’ theatre in the late eighteenth century and even what nation they were established to represent has been the subject of continued interest. Bauman, for instance, dodges the national aspect of Nationaltheater and claims that they were simply public theatres that sought to ‘elevate theatrical standards and taste without regard to profit’.Footnote 46 Although Gloria Flaherty foregoes defining the term in Opera in the Development of German Critical Thought, it is clear from her investigation of the Hamburg, Mannheim, and Vienna national theatres that she perceives the term along the same lines.Footnote 47

Others have directly explored what ‘nation’ these theatres represented institutionally and conceptually. In his Theater and Nation in Eighteenth-Century Germany, Michael Sosulski concludes that ‘the word “nation” stood for a community of common language, customs, culture, and temperament, but also for an ethical community of shared values and conduct’.Footnote 48 For him, the former group was in place before the national theatre movement, while the latter constituted the missing aspects of nation that the institutions were designed to establish and fulfil.Footnote 49 Sosulski traces how, in the face of political decentralization, a conceptual German nation was developed and acted out in vernacular plays found in the repertoires of Nationaltheater in Hamburg, Vienna, Mannheim, and Berlin. In this way, his study is similar to that of Lesley Sharpe, who likewise explored the development of a German national stage through the spoken plays of dramatists and actors including Goethe, August Wilhelm Iffland (1759–1814), and Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805).Footnote 50 Martin Nedbal complements these investigations by revealing how German identity was articulated in performances of opera in Vienna. Employing Gottsched’s views on theatrical didacticism as a point of departure and by subsequently examining Singspiele such as Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Die Zauberflöte, Nedbal argues that national identity in German-language music theatre was linked to morality. He thus explores the very aspect that Sosulksi maintains Nationaltheater were intended to project: while Sosulski argues that national theatres were founded to establish the nation’s morality, Nedbal posits that morality helped to establish the concept of nation. Seeking a definition of the term, Reinhart Meyer conceded that the label ‘Nationaltheater’ was unclear in the eighteenth century and became even more so in the nineteenth. Through an examination of the court and public Nationaltheater in Mannheim, Munich, and Berlin, he ultimately concluded that the only difference between a German-language theatre and a Nationaltheater is that the latter was simply named as such.Footnote 51

The scholarly division of Nationaltheater from other German theatres is significant. Yet investigations do not sufficiently address the relationship between the two because just as there is a selective focus on certain travelling companies, so too is there uneven coverage of Nationaltheater. This is owing to a tendency to focus on the same handful of theatres: Hamburg (1767), Vienna (1776), Mannheim (1777), and Berlin (1786), all of which were, or have subsequently been, labelled Nationaltheater. The importance of such investigations notwithstanding, their almost exclusive reliance on these examples is puzzling, given that there were additional Nationaltheater during the period in Altona, Augsburg, Bonn, Braunschweig, Brünn (Brno), Frankfurt am Main, Graz, Innsbruck, Mainz, Nuremberg, and Prague. Some of these German Nationaltheater were even situated in areas where German was not the largest cultural-linguistic group, such as in Brünn and Prague. And this is to say nothing of the hundreds of similar German theatres not formally called Nationaltheater active across Central and Eastern Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century that – as I shall show – were otherwise performing the same works as ‘official’ national theatres.

The distinction between Nationaltheater and German theatre was not lost on those performing on the late eighteenth-century stage. In 1777, one anonymous commentator contended that ‘the idea of stationary national theatres is nothing better than the fairy tale of the man in the moon. … Instead of one, the Nationaltheater consists of all the various, scattered considerable troupes’.Footnote 52 Fifteen years later, another contemporary report expanded on this point, questioning:

In Germany does one actually understand ‘Nationaltheater’ to be every stage on which German is spoken? Several theatres employ this title [to indicate] their precedence over others in which German is likewise spoken. But this should not at all be an essential asset. A number of Nationaltheater emerged over the past fifteen years without insisting on a definition of what one means by the term. Not long ago it was said in a newspaper [that] the prince had honoured the theatre with the title ‘Nationaltheater’. What is the honour? What does the title say? All Germans together constitute a nation. All German theatres are national theatres. Or does one want to create national divisions among the German nation[:] the Saxons, the Cologners, the Austrians, the Bavarians, the Mainzers, the Palatines, the Holsteins, the Brandenburgers, etc.? And should each of these nations have their own Nationaltheater? Thus it is! But then only natives are permitted to speak in their own national theatre so that the dialect of the nation – for good or bad, according to the style of the nation – can be used by posterity. If this does not happen, the title is an absurdity in the German provinces and the stages that seek an advantage with this title – are – [missing;] if a stage is called a national stage as opposed to other non-German-speaking actors, the title is gratuitous. ‘German stage’ is enough. ‘National’ actors are no better than all other German actors. It is different with court actors. They have an important title when they are paid by the court.Footnote 53

For this anonymous commentator, there was absolutely no difference between the two, as ‘all Germans together constitute a nation’ and therefore ‘all German theatres are national theatres’. Because they were financed by a specific institution, only court theatres deserved to be distinguished, presumably with the designation ‘Hofschauspielergesellschaft’ (or similar). The term ‘Nationaltheater’ was superfluous for the rest, as every German theatre was a theatre of the German nation. The examples the author calls upon to highlight national divisions appear purposely chosen. When mapped, these groups represent nearly every region of the Holy Roman Empire. There were hundreds of German-language theatres – including court, city, and travelling – any of which could be labelled Nationaltheater within these separate nations of the Empire. In this imperial context, the commentator’s insistence makes sense that Saxony, Bavaria, Mainz, the Palatinate, and Brandenburg, for example, are at once separate nations yet together create a larger nation. Despite their local and shared linguistic traditions, their individual German theatres were nevertheless all Nationaltheater because they together represented the collective German imperial nation.

The reluctance to accept that German-language theatres and Nationaltheater were one and the same – and the cultural implications of this parity – is only exacerbated by the fact that studies continue to employ the same small sample of Berlin, Hamburg, Leipzig, Mannheim, and Vienna to tell the story of late eighteenth-century German music theatre. Beginning with those by Hiller and ending with those by Mozart, Singspiel likewise continues to represent the repertoire performed in these theatres. But there were hundreds of other German theatres and, although important, Singspiel was not the only musical genre they staged. What is more, when contemporaries recounted the history of German theatre in the late eighteenth century, they often told the story of these companies, their movement across various places, and their performance of numerous musical and spoken genres.Footnote 54 Yet despite their role in bringing music theatre to audiences in diverse regions in ways that stationary theatres simply could not, mobile companies hardly factor into subsequent histories of the so-called ‘German-speaking lands’ or ‘German territories’. These terms have come to represent a nebulous cultural-linguistic entity that features prominently in accounts of emerging German national (musical) consciousness in the century leading to 1871.Footnote 55 When concerning the culture in which these musico-theatrical repertoires and institutions operated circa 1800, most studies favour these terms rather than engaging with the German political, cultural, and linguistic realm that did exist at the time: the Holy Roman Empire. This was the polity that linked German-language theatres, the musical genres they staged, the musicians who composed for and played in them, and the audiences for whom they performed. Yet to recognize the Holy Roman Empire as a framework for German music and theatre, it is important to understand what it was as well as its place in music historiography.

Das Heilige Römische Reich deutscher Nation in (Music) Historiography

The Holy Roman Empire existed for a millennium, from the coronation of Charlemagne (742–814) in ad 800 until the abdication of Emperor Franz II (1768–1835) in 1806. Originally a Frankish domain, the Empire increasingly became a German polity beginning with the coronation of Otto I (912–73) in 962.Footnote 56 Despite Voltaire’s oft-cited quip, that it was ‘neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire’, the Reich was ‘holy’ in that it was once understood as a universal Christian realm; it was ‘Roman’ in so far as it was perceived as a symbolic continuation of the Roman Empire; and it was an ‘empire’ comprising the kingdoms of Burgundy, Germany, and Italy.Footnote 57 The degree to which the ‘Holy Roman Empire’ was understood to reflect its constituent elements altered throughout its long history, during which it was mostly referred to as just ‘the Empire’. Although the Habsburgs carried the elected title of Holy Roman Emperor for much – but not all – of the early modern period, the Holy Roman Empire was distinct from the intersecting Habsburg Empire, also referred to as Austria or the Austrian Empire between 1804 and 1867.Footnote 58 Only a portion of the Austrian Empire was situated within the Holy Roman Empire, as much of its territory lay outside the Reich. Contemporaries were well aware of these distinctions, yet a misunderstanding has emerged in music scholarship that views the Habsburg realms, including those in the Holy Roman Empire, collectively as the ‘Habsburg Empire’. Indeed, this term is employed more generally – and occasionally unhelpfully – to denote any political entity in which the Habsburgs were involved rather than a specific polity, and to which I shall return. Because Habsburg territories constituted only a portion of those within the Reich, the histories, politics, and cultures of the Holy Roman and Habsburg empires are related, yet distinct.

The Holy Roman Empire comprised well over a thousand entities, around 315 of which were represented in the Reichstag towards the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote 59 Known as Imperial Estates (Reichsstände), these territories can be grouped into three subcategories: (1) electorates (Kurfürstentümer); (2) princedoms (Fürstentümer); and (3) Imperial Cities (Reichsstädte). Electorates and princedoms were ruled by individual governments, at the head of which were secular (hereditary) or ecclesiastical (elected or appointed) potentates whose place in the imperial system was distinguished by any number of titles including elector (Kurfürst), duke (Herzog), margrave (Markgraf), prince (Fürst), count (Graf), archbishop (Erzbischof), bishop (Bischof), and abbot (Abt) to name but a few. Grouped collectively as princes, these rulers could reign over multiple territories, which was reflected in any combination of titles. Others still could be at once the hereditary prince of one Estate and the elected ecclesiastical ruler of another, such as a prince-bishop. To complicate matters further, the land of ecclesiastical Estates frequently extended into the secular territories of neighbouring princes and Imperial Cities. Reichsstädte were governed by magistrates and were answerable only to the emperor, not any mediating prince whose territory might surround the city. All three categories of Imperial Estate supported music theatre directly through employment or indirectly by granting theatres permission to perform throughout their lands.

The governments of individual Imperial Estates were bound together by imperial institutions such as the Reichstag. Located in Regensburg since 1663, the Reichstag was an assembly of Estates established to coordinate the Empire’s responses to internal disorder and external threats. As principal commissioners from 1748 until the dissolution of the Empire, the Thurn und Taxis voiced the emperor’s interests at this assembly and entertained its ambassadors with their Hoftheater – that is until 1786, of course. The Reichstag was divided into the colleges of electors, princes, and cities. Each college met to debate and vote on matters separately before coming together. Once a consensus was reached, their decision would be presented to the emperor who could either veto it or approve it as imperial law.

Imperial law was upheld by two supreme courts. Founded in 1495, the Reichskammergericht had operated in Wetzlar since 1693 to judge breaches of the internal peace, oversee regional justice, and rule on religious disputes. When in session, members of the Reichskammergericht principally judged complaints between rulers of individual Estates, although they also heard cases in which rulers had infringed upon their subjects’ rights. When not in session, they were entertained by travelling companies that visited Wetzlar.Footnote 60 The Reichshofrat, the second imperial supreme court, was founded in 1498. This judiciary was situated in Vienna – which would become the principal Habsburg residence – and was designed to ensure the emperor’s prerogatives, provide him with legal counsel, and protect the public peace. On occasion, the Reichshofrat might even be called upon to assess appeals filed by theatre directors.Footnote 61

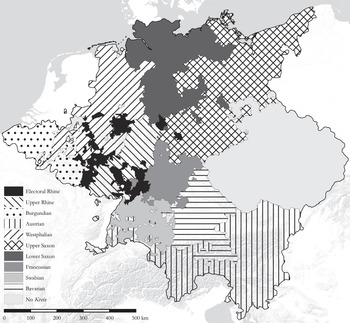

The verdicts of the Reichskammergericht and Reichshofrat were enforced by the Empire’s ten administrative circles (Kreise): Electoral Rhine, Upper Rhine, Burgundian, Austrian, Westphalian, (also called Lower Rhine), Upper Saxon, Lower Saxon, Franconian, Swabian, and Bavarian. Other integral parts of the Reich were not part of this system: Bohemia, Imperial Italy, Lusatia, Moravia, and Silesia (see Figure 0.2). The Kreise were larger, intermediary regions responsible for maintaining the road infrastructure upon which Taxis post carriages dispersed written communications and theatre companies travelled from one performance location to the next.Footnote 62 Each Kreis had the right to self-assembly, ensured its members equal representation (unlike the Reichstag), and assisted in the coordination of imperial defence and finances. The Kreise helped place Estates of varying size on equal footing and often led to cross-regional cooperation. Such was the case with the Bavarian, Franconian, and Swabian Kreise, which often worked together, creating even more expansive regional units.Footnote 63 Indeed, the Kreise helped to preserve the rights of smaller individual Estates not only in the face of their larger, more powerful neighbours, but also the emperor himself.

Emperors were elected by the elite group of princes aptly called electors (Kurfürsten). Successors were often chosen during the reign of a living emperor and crowned King of the Romans. The primate of the Imperial Church, the elector-archbishop of Mainz, oversaw the election and coronation of an emperor, which were regularly held in Frankfurt am Main beginning in the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote 64 Emperors reigned over both their Imperial Estate and the Reich. Yet while they were sovereign within their own territory, emperors did not wield absolute control over the Empire. Rather, the imperial constitution reserved two sets of powers for emperors: one for them alone (jura caesarea reservata), the other to be shared with imperial princes (jura comitialia). Save one brief period, members of the House of Habsburg (and Habsburg-Lorraine) were elected emperors throughout the early modern era, meaning that the emperor resided in their lands for much of this period.

Vienna had long been the principal Habsburg residence city (Residenzstadt) by the eighteenth century. It was not, however, the capital of the Holy Roman Empire. The focus on Vienna in studies of the period’s music imparts a disproportionate impression of its centrality in contemporary life, a misconception that betrays the underlying influence of modern, centralized nation-states that informs this assumption.Footnote 65 To be sure, the early modern period was not the era of nation-states, and the Holy Roman Empire had no signal capital. At least part of the scholarly emphasis on Vienna is also because the city belonged to both the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg Empire. Indeed, Vienna was at once an important cultural and political space within the Reich and the Habsburg territories not formally within the Holy Roman Empire, such as the kingdoms of Croatia, Slavonia, Hungary, and, later, Galicia and Lodomeria. Situated near the geographic extent of the Reich, Vienna was a hub that helped to link the Empire with Habsburg lands that extended deep into South-East Europe. Yet it was neither centrally located within the Reich, nor home to all of the Empire’s institutions. Hundreds of residence cities likewise served as the capitals of the Imperial Estates that constituted the Empire. The Reich’s institutions were themselves spread across territories in such locations as Regensburg (Reichstag), Wetzlar (Reichskammergericht), Vienna (Reichshofrat; emperor), Frankfurt am Main (site of coronation), and Mainz (primate of the Imperial Church).

The imperial institutions outlined here had time and again survived crises including the Reformation (beginning in 1517) and the Thirty Years War. They were put to the test again after nearly a century of peace when Brandenburg-Prussia incited the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–8) and later the Seven Years War. The Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918) lay beyond the Reich, yet was linked in a personal union to the Electorate of Brandenburg, meaning that Prussia acted as a foreign power while threatening the imperial peace simultaneously from within. Still, the Reich’s institutions continued to function until the very end of its long history. It is not for nothing that the Empire persisted for as long as it did, as the imperial institutions designed to ensure peace proved capable of reform to protect the rights of its constituent members. Even in the midst of the debilitating French Revolutionary (1792–1802) and Napoleonic wars (1803–15), the Imperial Church was the only institution that was dissolved, when, in 1803, the decision of a special Reichstag Imperial Deputation (Reichsdeputationshauptschluss) secularized and distributed ecclesiastical property as compensation to larger Estates that lost territories during the conflict.Footnote 66 Although in need of renewed reform owing to protracted wars with France and internal rivalry, the Reichstag, Reichskammergericht, and Reichshofrat persisted until Emperor Franz II dissolved the Reich on 6 August 1806, a move which many considered illegal.Footnote 67

In 1806, statesmen were suddenly faced with how to move forward after Franz II had released the Estates from the imperial system that had bound together most of Central Europe for nearly a millennium.Footnote 68 The German Confederation, which emerged from the Congress of Vienna nine years later, was little more than a rehashed version of the former Reich. Much as the Empire of the late eighteenth century, this new polity was plagued with internal rivalry. Prussia’s ultimate solution was to design a war that expelled Austria from the Confederation, in 1866, and then to engineer yet another conflict that brought the remaining German territories under its control in 1871.

What unfolded politically across the nineteenth century was mirrored culturally in the invention of nationalist histories. Informed by the idea of a powerful, centralized nation-state, Prussian historians deprecated the Reich, as its overlapping forms of sovereignty and identity (local and imperial) were incongruous with the concept of a Machtstaat unified in a single cultural nation. The nineteenth-century attitude towards the Reich is exemplified by the work of Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) and Heinrich von Treitschke (1834–96), who viewed the Holy Roman Empire as a fragmented monstrosity, the collapse of which in 1806 was a foregone and welcomed conclusion. In the opening of his Deutsche Geschichte im neunzehnten Jahrhundert, Treitschke was unwittingly prophetic when he contended that ‘the political history of the German Confederation can be contemplated only from the Prussian point of view’.Footnote 69

While Prussia no longer exists, its negative historical interpretation of the Reich has proven remarkably resilient. Informed by nineteenth-century scholarly traditions, the Sonderweg theory features the Empire prominently in seeking to explain how Germany’s historical trajectory deviated from other Western powers so as to make sense of the bloodshed of the Second World War and the Holocaust.Footnote 70 Despite renewed scholarly interest in the Empire beginning in the mid-twentieth century, the negative view of the Holy Roman Empire persists.Footnote 71 At the turn of the last century, Heinrich Winkler insisted that ‘everything that divides German history from the history of great European nations had its origins in the Holy Roman Empire’.Footnote 72 While the Sonderweg theory has been widely discredited, these opening words betray the staying power of this reading and the Empire’s place within it.

Historians including Georg Schmidt, Joachim Whaley, and Peter Wilson have done much to view the Holy Roman Empire in more positive terms rather than as a fragmented polity unable to live up to the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century imagination. Their work instead posits the Reich as a complex system that protected by peaceful means its diverse territories and peoples in the face of repeated crises. They have also argued that it was itself a powerful imaginary, a function that has been overlooked by those keen to distinguish it from the later nation-state. To borrow Whaley’s words:

The Holy Roman Empire was not a nation state and could never have become one. It was, however, a state, that is a coherent political order, and also clearly identified from the Middle Ages onwards with something that understood itself as the German nation.Footnote 73

The Reich was thus recognized as both a political state and a cultural nation, though it was not a nation-state that integrated these aspects. Rather, the Empire’s political and cultural spheres operated on separate, yet distinct levels. Its national identification can in part be gauged by the suffix ‘deutscher Nation’, which was first appended to the ‘Holy Roman Empire’ in 1474 and was used more frequently after 1512.Footnote 74

This ‘German Nation’ did not in the first instance denote a particular geographic area or even people, but rather the Estates that comprised the Reich. The early modern concept of the German nation could be employed as propaganda, a shared space that imperial princes were obligated to defend against foreign aggression.Footnote 75 Although the relationship between ‘Empire’ and ‘German nation’ was never defined with precision, there was consensus by the late eighteenth century that the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation was a federation of princes, a system commentators referred to as the ‘Reich’, ‘German Reich’, or simply ‘Germany’.Footnote 76 Most Germans – as a cultural-linguistic group – of all strata of society associated the Reich with the nation, understood the imperial constitution, and were aware of their place within it.Footnote 77 Writing in the 1780s, the leading expert of public law, Johann Stephan Pütter (1725–1807) believed that the unity of this nation was most ‘visible at the emperor’s court, the Reichstag, and the Reichskammergericht’, all of which helped protect the rights of those living within it.Footnote 78

To be sure, Germans were only one group and German but one language of many in the Holy Roman Empire. Communities within the Empire also spoke Czech, Dutch, French, Frisian, Italian, Ladin, Rhaeto-Romanic, Slovenian, and Sorbian.Footnote 79 The recognition of such linguistic diversity was enshrined in imperial administration. Depending on the recipient, civil servants wrote in Czech, German, Latin, or Upper Italian, the languages acknowledged in the Golden Bull of 1356.Footnote 80 Indeed, the Reich was home to disparate cultural-linguistic groups that ‘identified with the Empire to varying degrees, but only the Germans associated it with their nation’.Footnote 81 Not all Germans lived within the Empire, however.

German-speaking communities surrounded the Reich, forming a larger German cultural sphere, or Kulturkreis. The boundaries between the two were constantly in flux, making them difficult to delineate with precision. Generally speaking, the Reich was at the geographic heart of the wider Kulturkreis by the late eighteenth century. To the north were German speakers living in the kingdoms of Denmark (in a personal union with Norway) and Sweden; to the west and south were those in the United Provinces of the Netherlands, the Kingdom of France, and the Swiss Confederation; to the south-east were German communities extending from the Kingdom of Hungary into the Principality of Wallachia; and to the north-east was an expansive community that stretched through Prussia, Poland-Lithuania, and into the Russian Empire.Footnote 82 Even if they were not ethnically German, most educated people in these territories were fluent in German, which functioned as a lingua franca in much of Central Europe during the era and beyond.Footnote 83 Yet German speakers in these areas were not politically German, for they lived in polities neighbouring the Reich. Those situated along the Baltic coast, for instance, ‘regarded the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as guarantor of their identity and rights’.Footnote 84 The Reich fulfilled a similar function for its own diverse cultural-linguistic groups, allowing them to foster distinct identities that were not necessarily opposed to one another, Germans, or the Empire.Footnote 85 As Whaley would have it, such ‘diversity and complexity was no obstacle to a sense of belonging to a larger system or to identifying this system with the wider national community of the Germans’.Footnote 86

It was precisely this ‘inclusive diversity’, as Wilson has labelled it, that at once made the Empire distinctive and allowed disparate inhabitants to identify with it.Footnote 87 As historians of early modern Europe have warned, it would be dangerous to conflate the modern connotation of nation with the early modern concept that embraced such intersecting degrees of identity as local, regional, and supra-regional.Footnote 88 This helps to explain how diverse groups identified with the Empire as a polity and how Germans associated it with the nation. It also means that identity roughly followed the Reich’s hierarchical organization, giving way to multi-layered identification. Individual territories, regions, towns, and localities – manors, castles, and monasteries – all served as a locus of identity and belonging.Footnote 89 Yet so too did the Reich itself. During the 1700s, concepts of nation (Nation), fatherland (Vaterland), and patriotism (Patriotismus) began to compete with the earlier idea of a political German nation, entangling further multi-layered identification in the process.Footnote 90 As exemplified by the commentator who questioned the term ‘Nationaltheater’ above, Nation could at once refer to a specific territory – such as the County of Waldburg-Waldsee – and the Reich as a whole.Footnote 91 Whereas Vaterland might denote individual regions and rural communities, Patriotismus was the commitment to, and engagement in, the Nation or Vaterland, however one might have understood them.Footnote 92

In the face of growing (extra-imperial) Prussian Patriotismus following the Seven Years War, for example, Friedrich Carl von Moser (1723–98) attempted to unite regional identification with a broader imperial one when he proclaimed

We are one people, in name and language, under a common leader, together under our constitution, rights and duties determined by laws, bound to a great communal interest in freedom, unified to this important aim by a more than one-hundred-year [old] national assembly, the first empire in Europe [concerning] inner power and strength, whose royal crowns shine on German heads[.] And so, as we are, we [also have] through the centuries a puzzle [of a] political constitution, are our neighbour’s predation, [and] an article of their scoffing[.] Marked in the history of the world as discordant [among] ourselves, feeble through our divisions, strong enough to hurt ourselves, yet powerless to save ourselves, immune towards the honour of our name, indifferent towards the dignity of laws, jealous towards our leader, distrustful of one another, disconnected in principles, and violent in our implementation. A great Volk and nevertheless disdained, fortunate in possibility, but in practice very pitiable.Footnote 93

These are the opening words from Vom dem Deutschen Nationalgeist (1765).Footnote 94 Although Moser might have been critical of the Empire and its constituent Estates, he nevertheless contended that the basis of their common nation was the Volk, a community of free individuals united in culture and language.Footnote 95 Granted, Nation, Reich, and Volk would take on new, disparate, and ultimately dangerous meanings beginning with the rise of modern nationalism at the exact moment the Reich ceased to exist. According to Helmut Smith, although there were isolated articulations of German nationalism prior to 1806, ‘it was the defeated fatherland of Prussia that brought the new nationalism to the fore’ after it was overrun by the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821).Footnote 96 The concepts Nation, Reich, and Volk were thus deeply entwined for late eighteenth-century observers like Moser and Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803).Footnote 97 Contemporaries, therefore, understood the Reich as both a political state and as a German cultural nation with individual traditions that distinguished it from its neighbours.Footnote 98

One feature that set the Reich apart from Great Britain and France, for instance, was that it had no single national capital. This might have been a source of shame for later historians, but it nevertheless led to significant cultural innovation. As I mentioned at the beginning of this introduction, the Reich was the first to develop a systematic postal service in Europe.Footnote 99 The information and material disseminated throughout the Thurn und Taxis’s network included the Empire’s – and world’s – first weekly (Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien, 1605) and daily (Einkommende Zeitungen, 1650) newspapers, which appeared decades before the emergence of French (La Gazette, 1631, and Le Journal de Paris, 1777) and English (Oxford Gazette, 1641, and Daily Courant, 1702) equivalents.Footnote 100 By 1800, there were around 200 German newspapers issuing 300,000 copies each week for three million readers.Footnote 101 At this same moment, the Empire was home to some forty-five universities compared to France’s twenty-two and England’s two.Footnote 102 Literacy was comparatively quite high in the Empire. Between 1750 and 1800, aggregate literacy in Paris, Lyon, and Rouen, for example, averaged around 40 per cent; in Frankfurt am Main, Speyer, and Tübingen rates were about twice as high at 80 per cent.Footnote 103 It was within this very context of decentralization, communication, information, and education that the Nationaltheater emerged. With no national capital and with an aim towards promoting German culture, intellectuals, theatre directors, and princes established hundreds of German-language theatres across the Reich.

Although historians have done much to emancipate the Reich from Prussian historiographic hegemony, there has been no comparable effort in music scholarship. The Holy Roman Empire remains a misunderstood early modern polity that is rarely mentioned in studies of German music around the year 1800. When it does appear, it is more often than not with negative connotations and employed imprecisely alongside the ‘Habsburg Empire’. According to a book on Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), for instance, the Holy Roman Empire was ‘more a loose collection of states than a geographic entity – that sprawled across central Europe … [and] the role of the empire in power politics had been virtually nullified for more than a century before Beethoven’s birth in 1770 by the rising dominance of Britain, France, and above all Prussia’.Footnote 104 For a study of German opera, Germany in this period ‘was still some eight decades from unification, a widespread area of disparate territories held together by the loosest of bonds’, the Holy Roman Empire, which was ‘politically decrepit [and] administratively in a state of advanced senility’.Footnote 105 In addition, a history of Western music has insisted that ‘the multinational Hapsburg (“Holy Roman”) Empire was slowly crumbling under its own dead weight’.Footnote 106 To employ Holy Roman Empire and Habsburg Empire synonymously – something period commentators would not have done – is to conflate two distinct cultural and political spheres, as the Reich should not be confused for, or equated with, the Habsburg Empire. What is more, such characterizations of the Reich, all published after 2000 and still typical for even specialist studies of eighteenth-century German music, run counter to more positive assessments of the Holy Roman Empire published after 1945 and especially research that has appeared in the last thirty years. This, along with the focus on the same key modern-day German centres, is symptomatic of the continued dominance of nineteenth-century historiographic traditions in musical histories of Central Europe in the late eighteenth century.

Narratives of eighteenth-century music have historically centred around the concept of Viennese Classicism, a paradigm of music circa 1800 defined by the instrumental music of Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), Mozart, and Beethoven.Footnote 107 The continued reliance on Viennese Classicism is owing in part to the persistent perception that explorations of the period’s non-canonic locations, musicians, and repertoires run the risk of being dismissed as irrelevant. If Bauman’s concerns can be attributed to an earlier period, the very same sentiment compelled John Rice more recently both to defend and understate his choice to give ‘the great Austro-German triumvirate a little less prominence than most other surveys’ by explaining that

no one would dispute the beauty, importance, and value of their music; no one would wish to teach or take a course on eighteenth-century music in which their accomplishments were minimized … yet a modest shifting of emphasis away from Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven will, I hope, prove useful as we seek fresh insights into and a deeper understanding of eighteenth-century music and its place in European culture and society.Footnote 108

The music of these figures remain so deeply entrenched in the understanding of eighteenth-century music that when studies examine musicians, locations, and musical concepts of the period not limited to Vienna, they frequently do so in a context of these composers, thus returning conceptually to the city.Footnote 109 Bruno Nettl pointed out this tendency in the 1990s when he argued that musicologists defined themselves, and identified research topics, primarily in relation to a single composer and that explorations of a ‘minor composer’ depended on a ‘scholar’s ability to show relationship to or influence from or upon a member of the great-master elite’.Footnote 110 To be certain, scholars recognize that many composers played an important part in the history of late eighteenth-century music. But, as Nettl recognized decades ago, studies nevertheless continue to examine – or at the very least relate their investigations back to – the same subjects again and again.

There is little doubt that Viennese Classicism has done much to distort the musical world it purports to describe, ever since it first started taking shape in the 1830s.Footnote 111 And as this date suggests, the concept of Viennese Classicism is itself tied up in nineteenth-century nationalist projects: as Germans forged a new national identity, they sought to (re)invent their own musical tradition.Footnote 112 Scholars fashioned a select few composers, who were never strictly speaking either ‘Austrian’ or ‘German’, as their musical heroes and claimed instrumental music – which they then considered the aesthetic epitome of musical genres – for themselves, leaving vocal repertoires to the French and Italians. Furthermore, they wrote out of history composers valued in the period. This included Georg Benda (1722–95), who Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739–91) – having heard his music in its original contexts – considered ‘one of the premiere composers to have ever lived – one of the epoch-makers of our time’.Footnote 113 Nineteenth-century historians had long since distorted the political, cultural, aesthetic, and historic framework for Central European music at the vanguard of modernity.

To be sure, however, scholars have acknowledged the continued dominance of nineteenth-century narratives for some time, and alternatives have emerged. Although crucial, the Kleinmeister movement – which sought to recover forgotten, and discover new, Mozarts – was too little, too late.Footnote 114 More recent approaches draw stylistic divisions between North and South Germany and Austria.Footnote 115 In so doing, they construct geographic and political boundaries that did not necessarily exist at the time, overlooking the networks of politics, mobility, and communication that linked these areas. Other studies investigate individual urban centres and court establishments as alternatives to Viennese Classicism and regional approaches.Footnote 116 Yet as I posited above, many of these locations – such as Berlin, Munich, Prague, and Vienna – not only represent a narrow geographic axis, but they are also the capitals and principal cities of modern nation-states. This approach also serves to strengthen regional examinations, as Berlin, Munich, and Vienna have come to represent North German, South German, and Austrian musical cultures respectively, for example. Furthermore, much as regional examinations, studies of urban and court centres tend to overlook the connections between them. And to be sure, other alternative approaches turn to opera, rather than the instrumental music that characterized earlier studies. Such examinations have a tendency to focus on ‘elite’ Italian court opera and Mozart’s Singspiele.Footnote 117

Popular German genres by additional composers often play only a supporting role, and the treatment of Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739–99) exemplifies this all too clearly. A recent monograph investigates competition between Vienna’s Italian opera and the German Singspiel, which apparently came to a head in 1786.Footnote 118 This rivalry was marked by the lacklustre reception of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (later adapted for the German stage as Die Hochzeit des Figaro) and the resounding success of Dittersdorf’s Der Apotheker und der Doktor. It is easy to predict the narrative’s trajectory: competition between troupes resulted in competing works of distinct national genres (‘elite’ Italian and ‘popular’ German opera) and ultimately to the rivalry between composers, themselves representing mediocrity and genius. As reviewers of the book have noted, portions of this argument are based on conjecture.Footnote 119 Yet the conflict depicted in this account serves a purpose no matter how speculative it may be. With the familiar rivalry between Mozart and Antonio Salieri (1750–1825) long since debunked, a new nemesis was required. Rather than exploring the conditions surrounding the contemporary success of Der Apotheker und der Doktor and the relative failure of Le nozze di Figaro, the popularity of Dittersdorf’s Singspiel was instead employed to identify Mozart’s new rival.Footnote 120 This decision appears to have been anything but accidental. Facing two centuries of close investigation into Mozart’s life and works, it would be difficult to counter arguments made against Dittersdorf because few scholars and ensembles have sought to address the lacuna surrounding his biography and creative output. Hubert Unverricht summarized the scholarly neglect of Dittersdorf in 1997, revealing that the claims I am making here were valid not only then, but also as early as the late nineteenth century.Footnote 121 Still, Dittersdorf is a name associated with just enough success in Mozart scholarship to serve as a worthy opponent. Attempting to rehabilitate Salieri’s reputation after decades of antagonism for a wider readership, a New Yorker article draws on this recent Mozart scholarship and states bluntly: ‘A plot was indeed afoot against Mozart, but Salieri was not the ringleader. … The true operatic villain of Josephine Vienna [was] Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, a second-tier composer.’Footnote 122 The piece never pauses to consider if Dittersdorf might be receiving the same negative treatment that Salieri had and if it might itself be contributing to the mythicizing. It rather simply accepts the latest scholarly interpretation without question because it makes such a good story.

Well documented, Dittersdorf’s position as one of the leading composers for the German stage and the popular success of Der Apotheker und der Doktor are beyond doubt. Ernst Ludwig Gerber (1746–1819) considered him the ‘darling of the German public’, who had ‘filled so many hearts with joy and so many box offices with cash’.Footnote 123 An earlier version of Gerber’s lexicon concluded Dittersdorf’s entry by listing his successful operas and relating how the emperor publicly applauded him at a performance of Der Apotheker und der Doktor.Footnote 124 A review from 1786 believed that ‘of all the new German operas, this is the one that receives the most approval and that deserves it. The music, containing the most beautiful thoughts, is richly original; a true masterpiece of art!’Footnote 125 Published that same year, Uiber das deutsche Singspiel den Apotheker des Hrn v. Dittersdorf explains in greater detail just why this opera deserved the acclaim it received. Proclaiming Dittersdorf the rightful heir to Christoph Willibald von Gluck (1714–87), the anonymous author declares:

The simplicity in his vocal writing reigns without robbing the singer (who understands by the word ‘art’ as something other than wrenches of the throat) of the opportunity to enrapture us with their performance, exhibits Hr. Ditters’s knowledge of the nature of music and its innermost science – and the newness – with which he knows how to accompany the single voice with the command of a full accompaniment of instruments, so daring and so clever – is evident of a powerful genius.Footnote 126

Dittersdorf’s music was clearly appreciated by the audiences for whom he composed, even if he wrote this himself, as some suspect.Footnote 127 Among his many successful works, Der Apotheker und der Doktor ‘received extraordinary acclaim’ and ‘could not be given enough’ within and without Vienna – and to which I return in Chapter 2.Footnote 128 Yet despite the historical evidence pointing scholars in the direction of music theatre long known to have ‘received extraordinary acclaim’ like this, it has attracted scant attention at best. Needless to say there is a difference between popularity and perceived musical value. Modernists might argue that some repertoires are aesthetically deficient precisely because they are popular, while others might believe that Mozart’s works are simply better than those of his contemporaries. But it begs the question what attention other (popular) German music theatre would be afforded if Mozart had composed it. The continued scholarly neglect of Der Apotheker und der Doktor and its composer – like so many others from the period – betrays a reluctance to understand the historical reasons behind a piece’s popularity simply because it was not composed by a certain composer or because the genre is seen as unworthy of serious investigation. It is a matter of perceived aesthetic value versus historical observation, one that opens a can of worms regarding who determines this value. But then, this is what the canon is all about.

Investigation into German musico-theatrical traditions are thus largely relegated to the ‘peripheries’ generally, and to the confines of Vienna’s suburban theatres specifically.Footnote 129 Popular German music theatre of the period – least of all, yet most importantly, melodrama – is under-represented by comparison even in studies exploring the so-called ‘German-speaking territories’. Put another way, the Holy Roman Empire and its music has suffered due to national discourses as well as canonic sympathies and anxieties. The musicological reluctance to engage with – or at the very least recognize – recent historical studies of the Holy Roman Empire stems from an inability to perceive the Reich as anything but the backwards polity that nineteenth-century historians made it out to be. The Empire’s rich landscape of music theatre has yet to be explored.

Music Theatre and the Holy Roman Empire

The aim of this book is to do just that: to investigate the extent to which the Holy Roman Empire delineated and networked a cultural entity as expressed through music for the German stage circa 1800. To be certain, the Reich was entangled with the wider Kulturkreis that surrounded it, and it is often difficult to discern precisely the cultural boundaries between them. The Reich’s geographic placement rendered it an important hub helping to network the Kulturkreis which extended into neighbouring (non-German) polities. What is more, both were home to German theatres alongside those of additional cultural-linguistic groups. But because the polities that surrounded the Empire and overlapped with the Kulturkreis had a greater number of ‘national’ theatres performing in languages other than German, comparison between the two can be problematic. Furthermore, scholars have long noted that operatic genres were not afflicted by canonicity until much later when compared to the developing canon of instrumental music around 1800.Footnote 130 But music theatre – as opposed to instrumental music – was considered by contemporaries to be the aesthetic pinnacle of the musical arts during much of the period, a status reflected in its association with fame for those who created and performed it. The reason Schubart proclaimed Benda an ‘epoch maker’ was indeed owing to ‘his greatest creation, known as melodrama, [which] was soon received with general acclaim across Europe’.Footnote 131 Dittersdorf was considered the ‘darling of the German public’ because of his success at theatres across the Empire.Footnote 132 Their fortunes, and those of many others like them, rested primarily on their work for the German musical stage. That is not to say that instrumental music and other national operatic traditions were unimportant, but rather that the careers of most musicians active in Central Europe around the year 1800 – many of whom were at once composers and performers – hinged on their success in the German theatre. While acknowledging the extent of the Kulturkreis beyond the Reich, I focus on German-language music theatre and the Empire as the space in which a German polity and cultural nation intersected – though were not necessarily integrated – during this period.

Music theatre in the Holy Roman Empire assumed many forms. It comprised opera, melodrama, ballet, and incidental music, alongside which audiences could also hear instrumental concerts in the same theatres. Genres that set music to text included German-language works by poets and musicians who came from any number of cultural-linguistic backgrounds. The same diverse group of dramatists and composers – including native German speakers – often created foreign-language operas in the Empire. Other music theatre comprised settings and adaptions of foreign pieces for the German stage. All of these works were crafted for performers of countless backgrounds to be staged before cosmopolitan audiences. This makes identifying – let alone defining – what constituted an ‘original’ German work difficult, something that period commentators did not seem particularly keen to distinguish. I thus include all music theatre performed in German, for when distinctions were drawn it was based on residency of composers in relation to the Empire, not along categories of ‘original’ and ‘adaptation’ as Chapter 2 demonstrates further. Although the diverse forms of music theatre performed in the Reich’s theatres each have their own important story to tell, I focus particularly on the genres that set music to, and interacted most closely with, German text: Singspiel and melodrama. I maintain that this imperial music was made possible by, and converged in, the Empire’s network of theatres. Such institutions constituted nodes where musicians, dramatists, audiences, repertoires, fame, aesthetic tastes, theatrical developments, and criticism intersected and connected an expansive realm. The Empire’s stages and the resident and mobile companies that performed on them brought music theatre to a polity otherwise too diverse for a select group of theatres situated in a national capital. Although it might have been embarrassing and frustrating for nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historians, the Reich’s decentralized political system was an ideal framework for the cultivation of a common musico-theatrical culture that extended across Central Europe in the decades leading up to 1800.

It is not my aim merely to reclaim the Holy Roman Empire as a site of German music theatre circa 1800, but it is a point of departure. By drawing on digitized sources and newly discovered evidence found in archives, I posit that traditional musical boundaries, such as North Germany, South Germany, and Austria, as well as the court and public, can be better understood when viewed within the context of the Empire. Such divisions are really local realizations of a much larger common musical culture that spread across Central Europe.

As I demonstrate in the pages that follow, German music theatre was performed by far more travelling companies than the select resident troupes and Nationaltheater that have hitherto attracted the most scholarly attention. But almost nothing is known about them. Fundamental concerns, including how many there were, where they visited, what they staged, and for whom they performed, remain largely uncertain. Even less is understood about the reasoning behind their movements and programming decisions. While it is true that ‘each court or municipality had its own personality’, I argue that there was also a shared musico-theatrical culture linking them.Footnote 133 Looking beyond key cities and to the Empire as a whole sheds new light on the intersections of court and public music cultures. By shifting the primary focus from Vienna, capital cities, composers, and instrumental music to the Empire and its music theatre, this book opens a new vista of understanding that the emphasis on choice centres, composers, and genres has obscured. The music produced by Vienna’s composers undoubtedly forms an essential aspect of the musico-theatrical network that spread across the Holy Roman Empire in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By extension, studies of theatres in Berlin, Hamburg, Mannheim, and Prague betray important local realizations of the Empire’s larger culture of music theatre. But these urban locations constitute only a small number of centres belonging to a much larger and more complex system of music and theatre.

Beginning with the theatre network itself, Chapter 1, ‘An Empire of Theatres’, maps the vast web of German troupes that brought music and theatre to audiences across Central Europe around the year 1800. I focus primarily, though not exclusively, on the period 1775–1800, for that was when the Theater-Kalender was printed, and from which much of this chapter’s empirical data is drawn. Periodicals like this and missives written by those active at the Empire’s theatres allow me to investigate how this network functioned in practice as well as how it was imagined across vast distances. By arguing that the level of theatrical activity in any given place had more to do with its imperial context than with its population or geographic size alone, I examine the movement of the Empire’s companies to both redraw the theatrical map of late eighteenth-century Central Europe and to challenge further the perception of oppositional court and public cultures. I go on to posit that this very real network simultaneously existed in the imaginary thanks to print culture and a reading public. Alongside personal correspondence, journals – like Bärstecher’s that began this introduction – informed theatre directors of the activities of faraway companies and enabled audiences to experience the spectacle of theatre in their mind’s eye at a time and place of their choosing. While touring companies made the arduous journey from one city to the next, readers could be transported to theatres scattered across the Empire with the turn of a page. In other words, the Reich’s theatre network was as much a political and theatrical reality as an imaginary realm, where the bandwidth and diffusion of data was as important as the theatrical institutions, personnel, repertoires, and developments the information conveyed. Regulated from the bottom up, the Empire’s musico-theatrical complex – both physical and imaginary – was the foundation upon which an imperial music could be intensely cultivated.

Whereas Chapter 1 remaps the Reich’s network of theatres, Chapter 2, ‘(In)forming Repertoire’, identifies the music theatre audiences encountered in such theatres. I mine and analyze references to titles and musicians in the Theater-Kalender to ascertain those that received the most attention – and how recognition developed – throughout the era. This chapter demonstrates in the first instance that the Reich had its own practical repertoire that transcended any one area, national tradition, or group of composers. My distant reading of the Theater-Kalender also reveals new insight into the contemporary associations between music theatre and the musicians who composed it. Contemporaries often referenced a title without identifying a composer despite the fact that works could circulate in multiple versions by a single musician, in various settings by different composers, and as adapted texts by dramatists and musicians. But the years around 1785 marked a moment of gradual normalization during which topics already set to music would be generally avoided by composers and in which pieces circulating in multiple settings were increasingly linked to the work of just one composer. Pieces were often referenced by numerous titles, and it was also during this period that contemporaries questioned the practice of retitling music theatre, which could affect audience expectations and a theatre’s operation. I ultimately argue that the gradual emergence of a common imperial repertoire was owing to the regulatory capacity of such periodicals as the Theater-Kalender. By establishing which music theatre and musicians received the most attention, their relative importance by comparison to one another, and how associations between them altered throughout time, this chapter demonstrates that the Reich cultivated a shared repertoire that was formed and informed by networks of information, communication, and material exchange.

In Chapter 3, ‘Letters from the German Stage’, I investigate how written communication helped to regulate and network theatres and repertoire, as well as how information was put into practice by institutions that brought music to an empire. This central chapter begins with an exploration of the types of information communicated between companies and how discursive networks supported their performances. I argue that far from constantly competing to survive, as they are typically portrayed, companies also regularly cooperated with one another. I then turn to the theatre company of Gustav Friedrich Wilhelm Großmann (touring, 1778–96), the Electoral Mainz Nationaltheater (ecclesiastical-court, 1788–92), and the Theater zu Mecklenburg-Schwerin (secular-court-affiliated, 1788–92), which represent varying types of theatres in disparate imperial regions. By illustrating the equal importance of the dissemination of information and musical materials among these theatres, I further call into question traditional concepts of distinct musical regions as well as court and public cultures. Indeed, I reveal that theatrical companies were designed with both audiences in mind, and in practice cultivated a shared repertoire through the transmission of data whether at a court theatre or a public stage. Although programming choices were made to some degree based on location, the status of audiences, tastes of patrons, and access to performance materials, I posit that such decisions were usually owing to the intense communication of theatrical information and recommendations between theatre directors and enthusiasts – and, ultimately, to the expectations to which a collective imperial culture gave rise.