Chicahuaxtla TriquiFootnote

1

[

![]() i.kaˈwaks.

i.kaˈwaks.

![]() a ˈtɾi.ki] or Nânj ǹï'ïn [nã

4

h

nɯ1ʔɯ3] ‘the complete language’, as named by the Triqui people, is one of three languages in the Triqui subfamily of the Mixtecan family. The Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI 2014; http://www.inali.gob.mx/clin-inali/) lists two other Triqui languages with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility for speakers of Chicahuaxtla Triqui (Casad Reference Casad1974: 79) – the first is spoken in San Martín Itunyoso and the other in San Juan Copala.Footnote

2

a ˈtɾi.ki] or Nânj ǹï'ïn [nã

4

h

nɯ1ʔɯ3] ‘the complete language’, as named by the Triqui people, is one of three languages in the Triqui subfamily of the Mixtecan family. The Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI 2014; http://www.inali.gob.mx/clin-inali/) lists two other Triqui languages with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility for speakers of Chicahuaxtla Triqui (Casad Reference Casad1974: 79) – the first is spoken in San Martín Itunyoso and the other in San Juan Copala.Footnote

2

The Mixtecan family, which also includes Mixtec and Cuicatec, is one of eight families that make up the Otomanguean stock. The Otomanguean language stock consists of Mixtecan, Zapotecan, Popolocan, Chinantecan, Amuzgo, Tlapanec, Otopamean and Chiapanec-Manguean.

ChicahuaxtlaFootnote 3 Triqui is spoken in eleven communities:Footnote 4 San Andrés Chicahuaxtla (SAC), La Laguna Guadalupe, San Isidro de Morelos, San Marcos Mesoncito, Santa Cruz, Zaragoza, Yosunduchi, La Cañada Tejocote, Miguel Hidalgo Chicahuaxtla, San José Xochixtlán, Santo Domingo and San Isidro del Estado (Hernández Reference Hernández2013). Although the Triqui variants listed above share the ISO code [trs], there are significant phonological and tonal differences in addition to lexical variation among the different varieties, some of which will be discussed below. This Illustration will focus primarily on the variant that is spoken in San Andrés Chicahuaxtla.

The language consultant is a 52-year-old native of San Andrés Chicahuaxtla who speaks Spanish and Triqui fluently. The consultant translated two versions of the ‘North Wind and the Sun’ passage into Chicahuaxtla Triqui, based on the Spanish version published by Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (Reference Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas and Carrera-Sabaté2003: 259). He preferred the second translation because it sounded ‘more Triqui-like’ to him. Unless otherwise noted, the recordings included in this Illustration are from this language consultant.

ConsonantsFootnote 5

Chicahuaxtla Triqui has the following consonants: four voiceless plosives /p

t

k

k

w

/, four voiced plosives /b

d ɡ ɡw/, three affricates /

![]() /, five sibilants /s

z ʃ ʒ ʐ/, two laryngeals /ʔ h/; two prenasalized plosives /nd

nɡ/; and 10 lenis–fortis sonorants /m

mː n

nː l

lː j

jː w

wː/. The fortis alveolar lateral /lː/ is very rare in Chicahuaxtla Triqui. We found only one occurrence of this sound. For some consultants, /s/ and / ʃ/ occur in free variation with /z/ and /ʒ/, respectively. In addition, [

/, five sibilants /s

z ʃ ʒ ʐ/, two laryngeals /ʔ h/; two prenasalized plosives /nd

nɡ/; and 10 lenis–fortis sonorants /m

mː n

nː l

lː j

jː w

wː/. The fortis alveolar lateral /lː/ is very rare in Chicahuaxtla Triqui. We found only one occurrence of this sound. For some consultants, /s/ and / ʃ/ occur in free variation with /z/ and /ʒ/, respectively. In addition, [

![]() ] is an allophone of /j/ that surfaces before nasal vowels.

] is an allophone of /j/ that surfaces before nasal vowels.

Plosives

/p/ and /b/ are not native sounds of Chicahuaxtla Triqui (Elliott, Sandoval Cruz & Santiago Rojas Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012: 214). /p/ is realized as a voiceless bilabial plosive and may surface in word-initial or intervocalic position from influence of Spanish loanwords, many of which were adopted without modification except for tonal changes and final vowel lengthening.Footnote

6

In polysyllabic words, the penultimate syllable or tonic vowel from Spanish is usually tone 3 (T3), i.e. the default tone in Triqui, while the final syllable, always a vowel unless morphophonologically inflected, lengthens and frequently evidences a lowered tone. Examples include [pɾe

3

si

3

![]()

![]()

![]() 3

3

![]() eː32] ‘president’, [pɾo

3ɡɾa

3

maː32] ‘software program’, [

eː32] ‘president’, [pɾo

3ɡɾa

3

maː32] ‘software program’, [

![]() uh

3

pe

3ɾeː32] ‘pear’ and [

uh

3

pe

3ɾeː32] ‘pear’ and [

![]() ũː3

po

ũː3

po

![]() 3

3

![]() eː32] ‘post’. The word [la

3ˈpi

3

h] ‘pencil’, from Spanish lápiz [ˈla.pis], retains the original <p> from Spanish; however, stress is shifted from the penultimate to the ultimate syllable with the addition of a fricative segment [h] to word-final position.

eː32] ‘post’. The word [la

3ˈpi

3

h] ‘pencil’, from Spanish lápiz [ˈla.pis], retains the original <p> from Spanish; however, stress is shifted from the penultimate to the ultimate syllable with the addition of a fricative segment [h] to word-final position.

/b/ is realized as a voiced bilabial plosive and may occur in free variation with [ m b] in utterance-initial position or after a pause. Pre-nasalized stops have also been reported in other Otomanguean languages such as Mazatec, Mixtec and Otomí. Like /p/, the phoneme /b/ is not native to Chicahuaxtla Triqui and surfaces through Spanish contact (Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012).

Similarly to Spanish, intervocalic /b/ is sometimes pronounced as an approximant or non-fricative continuant [β]; however, after a nasal, laryngeal /h/ or a pause it is articulated as a plosive. Examples include [mbe4suː3] < ‘peso’ (< SP peso [ˈpe.so]), [m

bel

![]() 4

4

![]() uː3] < ‘pleito’ (< SP [ˈ

uː3] < ‘pleito’ (< SP [ˈ

![]() .

.

![]() o] ‘lawsuit’ or ‘dispute’), [beʐuː4] < ‘Pedro’, [m

baluː4] < ‘Pablo’ (< SP [ˈpa.

o] ‘lawsuit’ or ‘dispute’), [beʐuː4] < ‘Pedro’, [m

baluː4] < ‘Pablo’ (< SP [ˈpa.

![]() o]), [aɡw

a

4

h

bakaː3] ‘muge la vaca’ (< SP vaca [ˈba.ka]) ‘the cow moos’ and [nːeː32 βeɾe

o]), [aɡw

a

4

h

bakaː3] ‘muge la vaca’ (< SP vaca [ˈba.ka]) ‘the cow moos’ and [nːeː32 βeɾe

![]()

![]() eː3] < ‘aguardiente’ (< SP [a.ɣ

eː3] < ‘aguardiente’ (< SP [a.ɣ

![]() ar.ˈ

ar.ˈ

![]()

![]() e

e

![]() .

.

![]() e]) ‘firewater’.

e]) ‘firewater’.

[

![]() ] is a voiceless denti-alveolar plosive with long contact in Chicahuaxtla Triqui, see Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 22–23). /t/ in word-initial position may be pronounced as a consonant sequence [

] is a voiceless denti-alveolar plosive with long contact in Chicahuaxtla Triqui, see Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 22–23). /t/ in word-initial position may be pronounced as a consonant sequence [

![]()

![]() ] as a variant pronunciation of particular disyllabic words such as (s)tane

Footnote

7

[

] as a variant pronunciation of particular disyllabic words such as (s)tane

Footnote

7

[

![]() aneː3] ~ [

aneː3] ~ [

![]()

![]() aneː3] ‘goat’– a finding that was previously reported by Hollenbach (Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977) and Elliott et al. (Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012). Denti-alveolar [

aneː3] ‘goat’– a finding that was previously reported by Hollenbach (Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977) and Elliott et al. (Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012). Denti-alveolar [

![]() ] occurs principally in word-initial and medial position but can also surface in word-final position in fused enclitic morphophonological forms, e.g. [na

3ɾuʔwe

32

] occurs principally in word-initial and medial position but can also surface in word-final position in fused enclitic morphophonological forms, e.g. [na

3ɾuʔwe

32

![]() ] ‘[you] pay 2s.fam’, [si

3

] ‘[you] pay 2s.fam’, [si

3

![]() a

3

a

3

![]() ] ‘your (2s.fam) song’, [sa

1

] ‘your (2s.fam) song’, [sa

1

![]() ] ‘[you are] good 2s.fam’ or [jo

13

] ‘[you are] good 2s.fam’ or [jo

13

![]() ] ‘[you are] quick 2s.fam’. Word-final /t/ for these forms may be released in careful or slow speech (e.g. [

] ‘[you are] quick 2s.fam’. Word-final /t/ for these forms may be released in careful or slow speech (e.g. [

![]() ]) but is frequently inaudible in vernacular or rapid speech (e.g. [

]) but is frequently inaudible in vernacular or rapid speech (e.g. [

![]() ]) and may easily be confused with a glottal plosive [ʔ].

]) and may easily be confused with a glottal plosive [ʔ].

The segment /d/ is realized as a voiced denti-alveolar plosive [

![]() ] with long contact, see Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 22–23). In word-initial position or after a pause, /d/ frequently evidences prenasalization and may be articulated as [nd]. In intervocalic position, /d/ may be articulated as an interdental spirant [ð]Footnote

8

(Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977, Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012). /d/ does not occur in word-final position. Itunyoso Triqui <t> corresponds to [d] in Chicahuaxtla Triqui except for one example [ɾu3ðaʔ3]Footnote

9

(transcribed by DiCanio) ‘cylindrical grindstone’,Footnote

10

in which the intervocalic /d/ is fricativized, cited by DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 229). In Copala Triqui, the /d/ occurs natively in word-initial position and is pronounced as [ð] in intervocalic position only in Spanish loanwords (Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977), otherwise it is articulated as a plosive. As in Copala and Itunyoso Triqui, /d/ is not found in word-final position in Chicahuaxtla Triqui.

] with long contact, see Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 22–23). In word-initial position or after a pause, /d/ frequently evidences prenasalization and may be articulated as [nd]. In intervocalic position, /d/ may be articulated as an interdental spirant [ð]Footnote

8

(Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977, Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012). /d/ does not occur in word-final position. Itunyoso Triqui <t> corresponds to [d] in Chicahuaxtla Triqui except for one example [ɾu3ðaʔ3]Footnote

9

(transcribed by DiCanio) ‘cylindrical grindstone’,Footnote

10

in which the intervocalic /d/ is fricativized, cited by DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 229). In Copala Triqui, the /d/ occurs natively in word-initial position and is pronounced as [ð] in intervocalic position only in Spanish loanwords (Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977), otherwise it is articulated as a plosive. As in Copala and Itunyoso Triqui, /d/ is not found in word-final position in Chicahuaxtla Triqui.

/k/ is a voiceless velar plosive. In word-initial position, /k/ may occur before an oral or nasalized central vowel (e.g. [a

ã]) or oral back vowels (e.g. [ɯ o

u] but never precedes a front vowel (e.g. [e

i]). In word-medial position, /k/ may follow [i

a

u] but not before other vowels. In this environment, it may precede [a ɯ o

u] or [ã

![]() ]. When [u] precedes [k] in word-medial position, [u] must also follow (Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977). Examples include [ᵑɡuku

1h

u] ‘ocote pinecone’ and [ᵑɡu

]. When [u] precedes [k] in word-medial position, [u] must also follow (Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977). Examples include [ᵑɡuku

1h

u] ‘ocote pinecone’ and [ᵑɡu

![]() ukuː23] ‘carnival’. /k/ is not found in word-final position.

ukuː23] ‘carnival’. /k/ is not found in word-final position.

/ɡ/ (and its prenasalized variant [ŋɡ]) is realized as a voiced velar plosive and surfaces only in word-initial or word-medial position. Like /b d/ in intervocalic position, /ɡ/ may be pronounced as a voiced velar fricative [ɣ]; however, there are some speakers for whom [ɡ] and [ɣ] occur in free variation in this environment. In running speech, word-initial and intervocalic [ɡ] may undergo lenition to the degree that it is almost inaudible.

/k

w/ and /ɡw/ are voiceless and voiced bilabial-velar plosives, respectively. There are some instances in which [ɡw] evidences prenasalization, as in [ŋɡw

iː31] ‘person – soul’ (refer to the sound file in supplementary materials accompanying the online version of the present Illustration (http://journals.cambridge.org/IPA)). Pronunciation of /ɡw/ varies on a continuum from careful speech (e.g. [ɡw]) to the vernacular or rapid speech, where it may be pronounced [ᶢw] or simply [w] as in [

![]() uwiʔiː4] ‘sad’ in the transcription section below. Merrill (Reference Merrill2008) reported a similar finding for Tilquiapan Zapotec, another language belonging to the Otomanguean stock.

uwiʔiː4] ‘sad’ in the transcription section below. Merrill (Reference Merrill2008) reported a similar finding for Tilquiapan Zapotec, another language belonging to the Otomanguean stock.

Laryngeals

There are two laryngeals in Chicahuaxtla Triqui: /ʔ/ and /h/. In Itunyoso Triqui, DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 229) notes that /ʔ/ is realized ‘as short duration creak with significant pitch perturbation’ in intervocalic position while as a word-final coda consonant, complete glottal closure is evident. Both /ʔ/ and /h/ surface as mid-syllable interrupts (i.e. glottally interrupted vowels) in monosyllabic words in addition to word-final coda position.

The voiceless glottal plosive [ʔ] surfaces in initial, medial and final positions in Chicahuaxtla Triqui. In word-initial position, the degree of glottal constriction varies among consultants, compare [

![]()

![]() ːᵑ2] and [ʔ

ːᵑ2] and [ʔ

![]() ːᵑ2] ‘nine’. In medial position, [ʔ] can be followed by a sonorant but not by an obstruent, for example /ʔm ʔn ʔl ʔj ʔŋɡ ʔw/. In Itunyoso Triqui, DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 232) states that glottalization precedes and overlaps the initial portion of the consonant and is voiced throughout its duration. Contrary to DiCanio's findings, glottal stops surfacing before sonorant consonants in Chicahuaxtla Triqui rarely maintain voicing and most always involve complete closure of the glottis prior to the onset of the following consonant. While DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 232) argues that ‘glottalized consonants are better treated as undecomposable [sic], complex segments rather than sequences’ for all three Triqui languages, we believe, like Longacre (Reference Longacre1952, Reference Longacre1957) and Hollenbach (Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977, Reference Hollenbach1984), that glottal stop followed by a sonorant consonant constructions are best analyzed as sequences in Chicahuaxtla Triqui rather than a single preglottalized segment as per DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010).Footnote

12

ːᵑ2] ‘nine’. In medial position, [ʔ] can be followed by a sonorant but not by an obstruent, for example /ʔm ʔn ʔl ʔj ʔŋɡ ʔw/. In Itunyoso Triqui, DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 232) states that glottalization precedes and overlaps the initial portion of the consonant and is voiced throughout its duration. Contrary to DiCanio's findings, glottal stops surfacing before sonorant consonants in Chicahuaxtla Triqui rarely maintain voicing and most always involve complete closure of the glottis prior to the onset of the following consonant. While DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 232) argues that ‘glottalized consonants are better treated as undecomposable [sic], complex segments rather than sequences’ for all three Triqui languages, we believe, like Longacre (Reference Longacre1952, Reference Longacre1957) and Hollenbach (Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977, Reference Hollenbach1984), that glottal stop followed by a sonorant consonant constructions are best analyzed as sequences in Chicahuaxtla Triqui rather than a single preglottalized segment as per DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010).Footnote

12

Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, Longacre, Elliott and Rojas2012) found that tone and glottals co-occur in patterns such as 3h, 4ʔ, 3ʔ3 and 3h3, in addition to other tone–glottal combinations that we do not list here. Some glottal consonants [ʔ h] are not lexical but arise in constructions of tone–laryngeal marking of morphological form, for example [ʔ] in word-final position serves as a marking morpheme in verbs, possessed nouns, adjectives and prepositions, and indicates person and number for first person plural inclusive forms. In Chicahuaxtla Triqui, fused enclitics usually surface in word-final position, but they can, however, appear in mid-syllable positions – for example, where V is a vowel and [T] represents tone, exponents can be word-final: [Vʔ/hVT] or [VːT]; or mid-syllable: [VʔTV VhTV]. Both constructions, [VʔTV] and [VʔVT], appear to be identical but demonstrate different syllable patterns depending upon which vowel carries phonemically contrastive tone. [Vʔ/hTV] is a ‘split’ or glottally interrupted syllable that consists of only one syllable while [VʔVT] is a two-syllable construction (Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Edmondson, Longacre and Cruz2014). Some researchers refer to the glottally interrupted syllable as echo vowels, rearticulated constructions, extra harmonic vowels (Matsukawa Reference Matsukawa2008, Reference Matsukawa2012: 109–118) or laryngeally interrupted vowels (Silverman Reference Silverman1997: 242). Longacre (Reference Longacre1952: 75–76 fn. 2) argued long ago that mid-syllable glottal interrupts did not result in an additional syllable. In this Illustration, mid-syllable glottals [ʔ h] will be superscripted to indicate that glottally interrupted vowels (e.g. [Vʔ/hTV]) consist of one syllable. The following are examples of glottal stops [ʔ] in Chicahuaxtla Triqui:

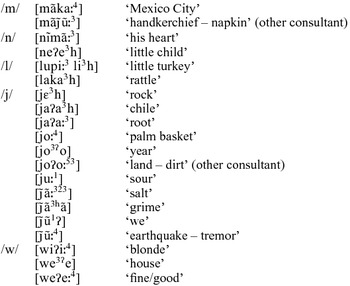

The following are representative examples of glottal stop [ʔ] plus sonorant consonant sequences (e.g. /ʔm ʔn ʔl ʔj ʔŋɡ ʔw/) in Chicahuaxtla Triqui:

Prenasalized plosives

[

![]()

![]() ŋɡ] are segmental sequences that are found in many varieties of Mixtecan languages.

ŋɡ] are segmental sequences that are found in many varieties of Mixtecan languages.

Affricates

Chicahuaxtla Triqui has three voiceless affricates: /

![]() /, /

/, /

![]() / and /

/ and /

![]() /. [

/. [

![]() ] is an apico-dental affricate and surfaces in word-initial and word-medial positions. It appears before /i ɯ/ and not before any other vowel.

] is an apico-dental affricate and surfaces in word-initial and word-medial positions. It appears before /i ɯ/ and not before any other vowel.

/tɕ/Footnote

13

is a voiceless prepalatal affricate that surfaces in word-initial and word-medial positions and appears only before /i

e/. /

![]() / is never found in word-final position.

/ is never found in word-final position.

/

![]() / is a voiceless affricate retroflex with airflow striking the tip of the tongue. It occurs in word-initial and word-medial positions. In word-initial or medial position it may surface before [i

e

a

o

u]; /

/ is a voiceless affricate retroflex with airflow striking the tip of the tongue. It occurs in word-initial and word-medial positions. In word-initial or medial position it may surface before [i

e

a

o

u]; /

![]() / never surfaces before [ə ɯ].

/ never surfaces before [ə ɯ].

Sibilants

/s/ is a voiceless narrow groove apical denti-alveolar fricative [s]. Based on the data collected for this study, /s/ appears mostly in word-initial position and may be voiced or voiceless without being semantically contrastive (i.e. [s] ~ [z]). /s/ may also surface before all vowels with the exception of [ə ɯ]. Although rather infrequent in word-medial position, it may occur before /i

u/, e.g. [siː3 ʐazũː2

ne

3

h

si

3

h] ‘their thing(s)’, and is commonly found in Spanish loanwords such as [me

3

saː3] ‘table’ (< SP mesa), [la

3

suː3] ‘lasso’ (< SP laso) and [

![]() a

3

suː3] ‘piece’, from the Spanish word pedazo ‘piece’.

a

3

suː3] ‘piece’, from the Spanish word pedazo ‘piece’.

/ʃ/ is a voiceless alveo-palatal fricative and surfaces before /i e a o u/ but not in conjunction with /ə ɯ/. Our data suggest that [ʃ] may occur in free variation with [ʒ] for the same consultant.

Although /ʃ/ and /ʒ/ may occur in free variation for some consultants, for others, this sound is almost always voiced /ʒ/, as in the following examples

Orthographically represented as <r>, rhotic /r/ in word-initial position has been commonly described as a voiced alveolar trill [r] in the Triqui languages (Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977, DiCanio Reference DiCanio2010, Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012); however, based on our most recent findings, trilled [r] is not as common in this environment as once believed. Hollenbach (Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977: 53) and Elliott et al. (Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012) note that /r/ in word-initial position may be pronounced as [dr] but is more commonly pronounced with acoustic frication, either as voiced [ʐ] or voiceless [ʂ]. For other speakers, varied articulations of /ʐ/ have been observed: [r

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ]. /ʐ/ in intervocalic position may be pronounced as a voiced alveolar flap [ɾ] but may be assibilated [ʐ] as well, compare [ŋɡuɾuwiː3] with [ŋɡuʐuwiː3] in the examples to follow. Voiced alveolar flap [ɾ] is not found in word-initial position.

]. /ʐ/ in intervocalic position may be pronounced as a voiced alveolar flap [ɾ] but may be assibilated [ʐ] as well, compare [ŋɡuɾuwiː3] with [ŋɡuʐuwiː3] in the examples to follow. Voiced alveolar flap [ɾ] is not found in word-initial position.

As previously stated, some consultants pronounce <r> as a voiced alveolar trill [r], as in the following examples:

Fortis–lenis contrasts

Perhaps one of the most striking features of the consonantal system of Chicahuaxtla Triqui are the fortis–lenisFootnote 14 phonological contrasts: [m mː n nː l lː j jː w wː]. Fortis phonemes are limited to monosyllabic words in Chicahuaxtla Triqui (Longacre Reference Longacre1952, Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977).

Although DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010: 230) notes that there are two groups of fortis–lenis consonantal contrasts in Itunyoso Triqui consisting of obstruents and sonorants, no such distinction has been found for obstruents in Chicahuaxtla Triqui. In Chicahuaxtla Triqui, fortis contrasts are limited to sonorants only.

The fortis consonants differ from their lenis counterparts by a ‘perceptible lengthening of the fortis phonemes’ (Longacre Reference Longacre1959: 37) and are restricted to word-initial position in monosyllabic words. Fortis voiced bilabial nasal [mː] is limited in its distribution and only surfaces before [i a]. [nː], fortis voiced alveolar nasal, appears only before [i e a ã ɯ] but does not surface before back labial rounded vowels [o u]. We found only one instance of the fortis voiced alveolar lateral approximant [lː]: [ma 32 lːe 4ʔ] ‘hello, sister’, by another consultant.

The lenis voiced palatal approximant /j/ surfaces in word-initial position before [ɛ a

o

u]. Longacre (Reference Longacre1957) claimed that /j/ has a nasal allophone, transcribed here as [

![]() ], when preceding a nasal vowel and surfaces in word-initial position before [ã ũ]. In Chicahuaxtla Triqui there is no fortis counterpart to [

], when preceding a nasal vowel and surfaces in word-initial position before [ã ũ]. In Chicahuaxtla Triqui there is no fortis counterpart to [

![]() ]. Fortis voiced palatal approximant /jː/ appears only before [a

o]. Fortis voiced velar approximant /wː/ may precede front vowels [i

e]. The following are examples of lenis–fortis contrasts.

]. Fortis voiced palatal approximant /jː/ appears only before [a

o]. Fortis voiced velar approximant /wː/ may precede front vowels [i

e]. The following are examples of lenis–fortis contrasts.

Fortis consonants [mː nː jː wː] were measured for their duration and subsequently compared to their lenis counterparts. Based on the data, on average, fortis /mː/ was 125% longer, fortis /nː/ was 129% longer, fortis /jː/ was an average of 75% longer and fortis /wː/ was 89% longer in comparison to their lenis counterparts. Independent samples t-tests were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) indicated that the duration of the fortis consonants was significantly different (p < .05) in comparison to the consultant's pronunciation of the lenis contrast (i.e. fortis phonemes are longer than their lenis counterparts). Since there was only one instance of fortis voiced alveolar lateral in our data set in the word [m ãː32 lːeʔ4], [lː] was excluded from the statistical analyses. Post hoc Student–Newman–Keuls testing for significant differences between the fortis–lenis pairings confirmed the results of the previous analysis.

Figure 1 illustrates the fortis–lenis contrast of [lː l] spoken by another consultant. The fortis token in [mãː32 lːe4ʔ] ‘hello, sister’ has a duration of 148 ms in comparison to its lenis counterpart in [waː li 3 h] ‘he is small’ which is 104 ms. The fortis voiced alveolar lateral is 44 ms or approximately 42% longer in duration in comparison to the lenis voiced alveolar lateral. Although this difference is not quite as great as those found for the other fortis–lenis contrasts, unlike the other comparisons, the contrast measured here was used in running speech and not in isolated repetitions.

Figure 1 Spectrogram depicting duration of lenis /l/ in [waː32 li 3 h] ‘he is small’ with fortis /lː/ in [m ãː32 lːe 4ʔ] ‘hello, sister’.

Tone

Chicahuaxtla Triqui has five basic tones (Ts) and from 10 to 15 tonal contours (Longacre Reference Longacre1957, Good Reference Good1979). In this Illustration, tones are designated from 1 to 5 superscripted, with 1 being the lowest and 5 the highest. Contrastive phonemic tone is generally found in word-final position except for some constructions such as the formation of the future and the past in which contrasting phonemic tone is generally found word-initially. The anticipatory mode (called potential in other investigations of Triqui and Mixtec) undergoes tone lowering in the aspectual prefix, [ɡa]-, [ɡi]- or [ɡV]-, with a concomitant lowering of tone in the final syllable, e.g. [

![]() ũ1

h

a

3ʔmiː43] ‘I speak – I am speaking’, [

ũ1

h

a

3ʔmiː43] ‘I speak – I am speaking’, [

![]() ũ1

h ɡa

3ʔmiː43] ‘I spoke’, [

ũ1

h ɡa

3ʔmiː43] ‘I spoke’, [

![]() ũ1

h ɡa

2ʔmiː2] ‘I will speak’ by another consultant. Matsukawa (Reference Matsukawa2009: 1) identified one rising tone /13/ and three falling tones /43 32 31/. Longacre (Reference Longacre1957) reports two sequences of three-tone segments /323/ and /312/ in open syllables.Footnote

15

Here we report on an additional three-tone segment of /353/ in [wːeː353] ‘palm mat’, listed in the examples below.

ũ1

h ɡa

2ʔmiː2] ‘I will speak’ by another consultant. Matsukawa (Reference Matsukawa2009: 1) identified one rising tone /13/ and three falling tones /43 32 31/. Longacre (Reference Longacre1957) reports two sequences of three-tone segments /323/ and /312/ in open syllables.Footnote

15

Here we report on an additional three-tone segment of /353/ in [wːeː353] ‘palm mat’, listed in the examples below.

Elliott et al. (Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012) provided a plot of Chicahuaxtla Triqui tones by extracting pitch trajectories (f0) for T5 through T1 using PRAAT v. 5.3.14 and plotting the results in MS Excel, see Figure 2. Based on the differences in semitones (with 0 set at 100 Hz), Elliott et al. (Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012: 218) show that the differences in semitones between tone /1/ and tone /2/ (i.e. low tones) and tone /3/ and tone /4/ (i.e. mid-tones) are minimal. Tone /5/ (i.e. extra high tone) averages approximately 5 semitones higher at its peak in relation to /4/.Footnote 16

Figure 2 Chicahuaxtla Triqui tone trajectories (Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Cruz and Rojas2012: 218, reprinted with permission) extracted from the following lexical items: T5 – [kuː53] ‘bone’; T4 – [nːãː4] ‘heat from the sun’; T3 – [k

ãː3] ‘squash’; T2 – [n

![]() a

2

h] ‘delicious’; and T1 – [wːiː1] ‘hidden’.

a

2

h] ‘delicious’; and T1 – [wːiː1] ‘hidden’.

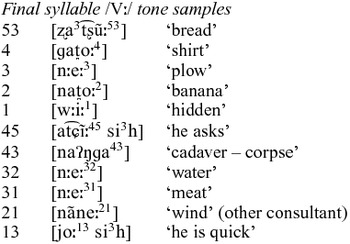

The following are tone examples in final syllable position in Chicahuaxtla Triqui:

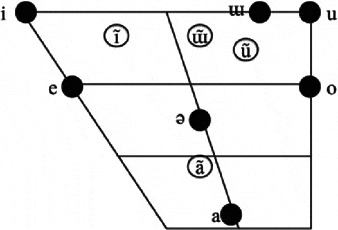

Vowels

Chicahuaxtla Triqui has eleven vowels: seven oral vowels /i

e ə a ɯ o

u/ and four nasal vowels /ĩ

ã

![]() ũ/. Medial nasal vowels /ẽ õ/ exist but only surface as fused enclitics in morphophonological forms in verbs, possessed nouns, and adjectives (Elliott Reference Elliott2013, Hernández Reference Hernández2013), e.g. [ᵑɡã

2

n

ã

2ɾuʔwẽː323] ‘[he – she] will pay’, [si

3

n

ã

2

ũ/. Medial nasal vowels /ẽ õ/ exist but only surface as fused enclitics in morphophonological forms in verbs, possessed nouns, and adjectives (Elliott Reference Elliott2013, Hernández Reference Hernández2013), e.g. [ᵑɡã

2

n

ã

2ɾuʔwẽː323] ‘[he – she] will pay’, [si

3

n

ã

2

![]() õː23] ‘[his – her] banana’, [j

õː323] ‘[he – she is] quick’.

õː23] ‘[his – her] banana’, [j

õː323] ‘[he – she is] quick’.

Similarly to the Copala and Itunyoso Triqui variants (Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977, DiCanio Reference DiCanio2010), Chicahuaxtla Triqui has no diphthongs. When two vowels occur, they are always pronounced as the nucleus of a separate syllable (Hollenbach Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977, Longacre Reference Longacre1952: 75 fn. 2). Spanish loanwords containing diphthongs and triphthongs may vary in their pronunciation depending upon the consultant. Some speakers may pronounce these sounds as they do in Spanish (i.e. as diphthongs or triphthongs), while others may pronounce them as labialized /k

w/ and /ɡw/, e.g. [si

3

li

4

h

sk

w

e

3

laː2] ‘student – scholar’ from the Spanish borrowing escuela ‘school’ or [ɡw

a

![]() juː3] from caballo ‘horse’. Orthographically represented as <ë ï>, [ə ɯ] mostly surface in final syllables, e.g. [kɯ3hɯ] ‘mountain – hill’ or [əː43] ‘what?’. [ə ɯ] may surface in non-final syllables provided that the same vowel is found in the final syllable as well, for example, [ɡa

3

k

juː3] from caballo ‘horse’. Orthographically represented as <ë ï>, [ə ɯ] mostly surface in final syllables, e.g. [kɯ3hɯ] ‘mountain – hill’ or [əː43] ‘what?’. [ə ɯ] may surface in non-final syllables provided that the same vowel is found in the final syllable as well, for example, [ɡa

3

k

![]() 2ʔ

2ʔ

![]() 3] ‘sin; blame’ and [əʔə32h ʃio

4ʔ] ‘hiccough’. Longacre (Reference Longacre1957) and Hollenbach (Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977) found a similar restriction on the distribution of /o/ in both Chicahuaxtla and Copala Triqui, respectively, however no mention was made regarding the distribution of /ə ɯ/.

3] ‘sin; blame’ and [əʔə32h ʃio

4ʔ] ‘hiccough’. Longacre (Reference Longacre1957) and Hollenbach (Reference Hollenbach and Merrifield1977) found a similar restriction on the distribution of /o/ in both Chicahuaxtla and Copala Triqui, respectively, however no mention was made regarding the distribution of /ə ɯ/.

Matsukawa (Reference Matsukawa2012: 72) reports that [

![]() ] is not used by some speakers of Chicahuaxtla Triqui and is frequently pronounced by younger speakers as [ĩ]. Recent fieldwork carried out by Elliott (October–November 2012, July 2013 and November 2014) lends credence to Matsukawa's claim. Consider the following examples:

] is not used by some speakers of Chicahuaxtla Triqui and is frequently pronounced by younger speakers as [ĩ]. Recent fieldwork carried out by Elliott (October–November 2012, July 2013 and November 2014) lends credence to Matsukawa's claim. Consider the following examples:

Based on our data, pronunciation of /ə/ may vary (e.g. /ə ~ e/) for the same speaker, compare [əʔə32 h ʃio 4ʔ] with [eʔe32 h ʃio 4ʔ] ‘hiccough’.

Both oral and nasal vowels of Chicahuaxtla Triqui are plotted in the vowel diagram. The data for the vowel plot come from the mean of acoustic measures of F1 and F2–F1 for both stressed oral and nasal vowels produced by the male speaker. Several tokens for each nasal and oral vowel were recorded in isolated words – minimally three repetitions of each word. The number of tokens that were recorded and analyzed was determined by the number of occurrences we had.

Transcription of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

Broad transcription

Narrow transcription

‘The North Wind and Sun’ in Spanish

El viento norte y el sol discutían sobre cuál de ellos era el más fuerte, cuando pasó un viajero envuelto en ancha capa. Convinieron en que quien antes lograra obligar al viajero a quitarse la capa sería considerado el más poderoso. El viento norte sopló con gran furia, pero cuanto más soplaba, más se envolvía en su capa el viajero. Por fin el viento norte se dio por vencido. Entonces brilló el sol con ardor e inmediatamente el viajero se quitó su capa; por lo que el viento norte tenía que reconocer la superioridad del sol.

‘The North Wind and the Sun’ in English

The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger, when a traveler came along wrapped in a warm cloak. They agreed that the one who first succeeded in making the traveler take his cloak of should be considered stronger than the other. Then the North Wind blew as hard as he could, but the more he blew the more closely did the traveler fold his cloak around him; and at last the North Wind gave up the attempt. Then the Sun shone out warmly, and immediately the traveler took off his cloak. And so the North Wind was obliged to confess that the Sun was the stronger of the two.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible through UT-Arlington Presidential Funds, a University Research Enhancement Grant and travel funds that were generously provided by The Charles T. McDowell Center for Critical Languages and Area Studies at the University of Texas at Arlington. We would like to thank the leaders of San Andrés Chicahuaxtla for welcoming us into their village and for enthusiastically helping us in the documentation of their language. The following graduate and undergraduate students participated in the data collection for this research: Thelma Cabrera, Brenda Jackson, Jaha Thomas, Paul Jacob Kinzler, Kevin Knochel, Aaron Lansford, Humberto Rodríguez and Ramiro Valenzuela. We would also like to thank Adrian Simpson and the anonymous reviewers, whose comments and suggestions were invaluable in the final preparation of this manuscript. We dedicate this article to our dear colleague and friend, Dr. Robert E. Longacre (1922–2014), a pioneer in the first studies on Chicahuaxtla Triqui.

a ˈ

a ˈ