Globally, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in young children is high, with 41 million children under the age of 5 reported to be overweight or obese in 2016(1). Obesity in childhood is associated with both short- and long-term health conditions(1–Reference Reilly, Methven and McDowell3). Studies report that excess weight tracks into adulthood, increasing the lifetime risk of a range of diseases(Reference Reilly and Kelly2,Reference Umer, Kelley and Cottrell4) . The primary determinants of excessive weight gain are poor diet and physical inactivity (including excessive sedentary behaviour)(5). While international guidelines for physical activity, sedentary behaviour and healthy eating in young children exist, research suggests that the majority of children do not meet such recommendations(Reference Hinkley, Salmon and Okely6,Reference Kranz, Findeis and Shrestha7) . As such, leading organisations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), recommend that these risk factors be targeted in community-based interventions to achieve the healthy weight status of children(8).

Early childhood education and care services represent an important setting for implementing health-promoting interventions, given that they provide access to a significant proportion of young children for prolonged periods throughout the day(9). In Australia, such services primarily consist of centre-based childcare services and family day care services(10), also known as family childcare homes and childminding in the United Kingdom. Centre-based childcare services are typically run in a purpose-built facility, have set hours of operation and can accommodate a larger number of children(11). Family day care services, which usually provide care to a smaller number of children within an individual provider’s own home, where hours of operation and regulatory structures vary, is the focus of the current review(11).

Family day care services are the third largest provider of care for children in Australia who do not attend school (approximately 10 % of the population)(10), and almost one million (11 %) children in the United States access such care(Reference Laughlin12,13) . Family day care services may also be accessed by more disadvantaged groups due to their overall lower daily fees(9), with the proportion of Australian families accessing such services increasing as income reduces. In the United States, a study in family day care services reported that 63 % of children were of African American background who report poorer health outcomes(Reference Benjamin-Neelon, Vaughn and Tovar14).

There is a significant opportunity to improve children’s obesogenic behaviours while attending family day care services. A systematic review examining preschoolers’ physical activity levels in family day care services has found that the average time preschoolers spent in moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity and total physical activity was 5·8 and 10·4 min/h, respectively(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15), which is lower than the recommendation of 120 min of activity in care(16). A review of screen-viewing has found that children attending family day care services engaged in 108–114 min of screen time per day compared to 6–78 min for children attending centre-based care(Reference Vanderloo17). While no review of dietary intake exists, a number of cross-sectional studies of children attending family day care services in the United States have reported that diet quality scores varied from 59 to 64 out of a possible 100, highlighting significant opportunities for improvement(Reference Benjamin-Neelon, Vaughn and Tovar14,Reference Tovar, Benjamin-Neelon and Vaughn18) .

The majority of research to date has focused on improving child’s diet, activity and weight in centre-based care, such as preschools and long-day-care centres. The interventions undertaken in centre-based care include those targeting environmental enhancements (e.g. interventions that aim to change the availability of food and/or play equipment), curriculum (e.g. interventions that schedule time for structured play or healthy eating opportunities), policy (e.g. interventions that demonstrate organisational commitment) and education (e.g. interventions that seek to improve the skills and knowledge of staff, children and parents)(Reference Temple and Robinson19–Reference Wolfenden, Jones and Finch21). While family day care services can act in accordance with regulations and standards similar to centre-based childcare services(11), the ability of providers to deliver health promotion programmes is likely to differ from centre-based childcare(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15). The organisational nature of family day care services, which involves smaller numbers of children of wider age ranges, single caregiver environments, as well as different physical infrastructures and levels of staff training, is likely to present unique challenges with the implementation of health promotion programmes(Reference Ward, Vaughn and Burney22). Previous studies have also highlighted that family day care providers may have poorer health behaviours, which may impact their ability to become positive role models for children in their care(Reference Tovar, Vaughn and Grummon23).

A recent review by Francis et al.(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15) in 2018 sought to describe US-based studies that examined the nutrition and physical activity-promoting environments of family day care services. This review of observational studies has found that there are significant opportunities to improve the physical, policy and sociocultural environments of US-based family day care services to promote healthy eating and physical activity among children attending these services. In particular, the review highlighted that a lack of comprehensive written policies, lack of training for family day care providers, inaccurate nutrition beliefs, poor communication with families, lack of equipment and space for play, and poor feeding practices may need to be targeted to improve child’s diet, activity and weight-related behaviour. To our knowledge however, there has been no previous synthesis of the impact of intervention studies that seek to improve the diet, physical activity and weight status of young children attending family day care services. Such a review is warranted to identify effective approaches and opportunities to enhance future research in this setting. As such, this systematic review sought to identify and assess the effectiveness of interventions to improve the dietary intake, physical activity and weight status of children aged 0–6 years attending family day care services. Secondary aims of the review were to examine the impact of the interventions on family day care services’ health-promoting environments, policies or practices, similar to that defined by Francis et al.(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15) Additionally, adverse outcomes and costs of the intervention were also examined. Lastly, the review sought to describe ongoing studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Methods

Registration

This review employed rigorous review procedures as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration(Reference Higgins and Green24), including pre-specifying review questions and screening by two individuals at every stage. The review was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42017077078) and is reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff25).

Information sources and search strategy

A computer-based literature search was carried out in March 2019. The search strategy was developed in consultation with an experienced medical research librarian and conducted on the following electronic databases: Medline in Process, PsycINFO, ERIC, Embase, CINAHL, CENTRAL and Scopus. The search strategy included search terms for the setting (childcare services and family day care services) as well as ‘dietary intake/nutrition’, ‘physical activity’ and ‘weight’-related search terms used in a Cochrane systematic review(Reference Wolfenden, Jones and Finch21) undertaken by the authors (see online Appendix A for search strategy). The reference lists of all potentially relevant studies and systematic reviews were also searched by one author (M.L.).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

To be included in this review, studies must have examined an intervention aiming to improve the diet, physical activity and/or weight status of children attending family day care services, with a parallel control arm, including randomised, cluster-randomised, factorial trial, interrupted time series, multiple baseline, stepped wedge and any controlled non-randomised trial. For the purpose of this review, the term ‘family day care services’ refers to a formal type of childcare service where providers deliver care to a small group of children typically in the provider’s own home. Family day care services are an approved form of childcare, generally cater to children prior to compulsory schooling and are usually required to undergo licensing and accreditation processes(11).

All interventions that promote healthy eating, nutrition and/or physical activity, reduce sedentary behaviour or prevent unhealthy weight gain were eligible for inclusion. Interventions could be environmental, organisational or policy- and practice-related; singular or multi-component; and delivered by research staff, family day care service staff or any other organisation or expert. These could include interventions targeting environmental enhancements, curriculum, policy and staff, as well as parent and children education and knowledge. Interventions that target factors influencing the operation of family day care services in relation to professional guidelines, accreditation standards, food procurement strategies or other interventions were also eligible for inclusion. There were no restrictions on intervention duration. Interventions that targeted family day care services as part of a broader multi-component intervention targeting child’s dietary intake and physical activity were eligible for inclusion if outcomes from the family day care services could be isolated.

Outcomes included any objective or subjective measures of dietary intake, physical activity or sedentary behaviour and measures of weight status. Secondary outcomes included those related to family day care services’ health-promoting environments, policies or practices, adverse outcomes or any estimate of intervention costs. Examples of family day care environments include changes to the physical environment (availability of healthier foods, water, play equipment), policy (the presence and content of healthy eating and physical activity guidelines) and sociocultural environments (role modelling of healthy eating behaviours by family day care providers)(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15) of the family day care service. This may be assessed via audits of service records, questionnaires or surveys of staff, service managers, other personnel or parents; direct observation or recordings; examination of routine information collected from government departments or other sources.

Exclusion criteria

Manuscripts or reports not published in English were excluded, as were studies involving centre-based childcare services only (e.g. preschools, long-day-care services, kindergartens), as well as informal types of childcare provided in the child’s own home (e.g. care given by grandparents, nannies, au pairs, babysitters). Studies that did not have an intervention component delivered within family day care services were also excluded (i.e. studies that recruited participants from the setting only). Interventions that focused specifically on examining malnutrition/malnourishment were excluded, as were those examining obesity treatment (i.e. those included only overweight/obese children).

Study selection

Screening procedures developed for the review were pilot-tested before use and undertaken using an online systematic review tool, Covidence(26). Two authors (among S.L.Y, M.L., L.K.C., S.M.) independently screened all titles and abstracts. Full-text manuscripts of all potentially relevant studies were obtained and independently assessed for eligibility by two authors (among M.L., L.K.C., M.F., K.S., E.K., S.L.Y.). In instances where conflicts regarding the eligibility of studies were not resolved via consensus, a decision was made by a third author (among S.L.Y., L.K.C., A.G.). Authors of potentially relevant studies were contacted to request provision of additional data. Authors of published protocols were also approached to request further details of any publications in the press.

Data collection processes

Two authors (A.G. and M.L.) independently extracted information using a data extraction form developed based on the recommendation included in the Cochrane Public Health Group Guide for Developing a Cochrane Protocol(27). Data extracted included: (1) study information, including study design, date of publication, childcare service type (e.g. family day care service), country, recruitment rate, service/participants’ demographic/socioeconomic characteristics and number of experimental conditions; (2) characteristics of the intervention, including the duration, number of contacts, intervention components and implementation strategies classified according to the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy(28), theoretical underpinning and delivery modalities, as well as a description of control; (3) primary and secondary outcomes, including data collection methods, validity of measures used, effect size and measures of outcome variability, where possible; (4) intervention costs and adverse outcomes; (5) source(s) of research funding and potential conflicts of interest. All discrepancies in the data extraction process were resolved between review authors by consensus.

‘Risk of bias’ assessment

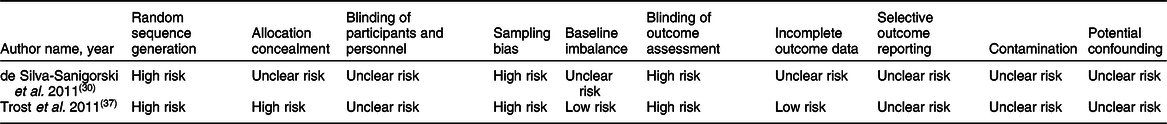

Two authors (A.G. and M.L.) independently assessed the risk of bias using the ‘Risk of Bias’ tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Reference Higgins and Green24). Each included study was given a ‘risk of bias’ assessment (‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’) based on the consideration of methodological characteristics (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and ‘other’ potential sources of bias). Discrepancies were resolved between authors by consensus. We included ‘potential confounding’ as an additional criterion for the assessment of risk of bias due to the inclusion of non-randomised trial designs(Reference Higgins and Green24).

Analysis

We were unable to undertake a meta-analyses as the included studies were highly heterogeneous. Instead, we narratively described the intervention and outcomes as reported by each study.

Results

Study selection

The electronic search yielded 8965 citations. An additional twelve records were identified from checking the reference lists of potentially relevant systematic reviews, publications and study protocols. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, 199 full texts were obtained for further review. Two controlled studies that assessed the impact of interventions on family day care service’s health-promoting environments were included; however, both did not measure any impact on child-level outcome (primary aim). The primary reasons for excluding studies from the review are presented in Fig. 1. One study was excluded as it did not address diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour; rather, it examined an intervention to improve children’s social and emotional wellbeing. Although studies may have examined interventions to improve family day care environments, not having a parallel control group resulted in their exclusion. Online Appendix B provides an overview of such types of previous interventions undertaken in this setting(Reference Bravo, Cass and Tranter29–Reference Woodward-Lopez, Kao and Kuo36).

Fig. 1 Study flow diagram

Study characteristics

The trials were conducted in the United States (n 1)(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37) and Australia (n 1)(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30), and both published in 2011 (conducted 2004–9). Participants were family day care schemes (the managing organisational structure) and family day care providers (individuals providing care to children). Eighteen family day care schemes participated in one trial(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30), with family day care providers ranging from 251 to 533 across both trials. Both studies were of a quasi-experimental design, comparing the intervention participants to a cross-sectional sample drawn from the same state in which the interventions took place. Characteristics of included studies are reported in Table 1.

Table 1 Study characteristics of included trials

SEIFA, socioeconomic index for areas.

Risk of bias

Both studies were judged as having a high risk of selection bias (i.e. random sequence generation and allocation concealment) as they were non-randomised trials (see Table 2). Further, for both trials, there was insufficient information to assess for the following criteria: selective outcome reporting, contamination and potential confounding. The study by Trost et al.(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37) was judged as having a low risk for incomplete outcome data and baseline imbalance.

Table 2 Risk of bias assessment extracted from included studies

Interventions

Intervention duration ranged between 12 months(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37) and 4 years(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30) between the two studies. One study aimed to determine the effectiveness of a community-wide programme in reducing obesity and promoting healthy eating and active play among young children (aged 0–5 years)(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30); the other aimed to assess the impact of a train-the-trainer intervention on family day care services’ healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37). The study by de Silva-Sanigorski et al. (Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30) used health promotion principles by Nutbeam(Reference Nutbeam38,Reference Nutbeam39) and the socioecological framework(Reference McLeroy, Bibeau and Steckler40,Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza41) to guide intervention development, while the other study did not report the use of theory(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37). Both studies used a range of strategies delivered to family day care providers, including educational meetings (training), educational outreach visits and educational materials.

Measures

Both studies used self-reported environmental surveys to assess the impact of the interventions. de Silva-Sanigorski et al. (Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30) used an environmental audit to capture factors in the physical, policy, sociocultural and economic environment of family day care providers, whereas Trost et al.(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37) employed the validated Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care self-assessment instrument(Reference Benjamin, Ammerman and Sommers42,Reference Benjamin, Neelon and Ball43) to capture the implementation of nutrition and physical activity policies and practices within family day care.

Outcomes

One study reported statistically significant improvements in the intervention group on a number of environmental outcomes, including increased active play opportunities and more healthy eating rules and supportive meal time practices compared to the control group(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30). The other study reported statistically significant improvements in healthy eating and physical activity environment scores among the intervention group compared to the control(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37). Neither trial measured the impact on child outcomes, nor reported intervention costs or adverse effects.

Ongoing studies

Two ongoing studies were also identified. The first was a two-arm, cluster randomised controlled trial involving 150 family day care providers and 450 children. The 9-month intervention conducted in the United States targeted the health, knowledge and skills of the family day care provider to create environments to encourage healthy eating and physical activity in children, and adopt sound business practices(Reference Ostbye, Mann and Vaughn44). The second protocol was a cluster-randomised trial with 132 family day care providers and 396 children in the United States. The study compared the intervention aimed at improving food and physical activity environments with an active comparison group that provided resources related to literacy and school readiness(Reference Risica, Tovar and Palomo45).

Discussion

This review is the first to synthesise findings from controlled trials, conducted in family day care services, that examined interventions to improve child’s diet, physical activity and weight status. We could not identify any studies that met the pre-specified inclusion criteria for the primary outcomes; however, two studies that examined the secondary outcomes of family day care service’s healthy eating and/or physical activity environments were included. Additionally, two ongoing studies conducted in the United States were identified, which are likely to contribute considerably to the evidence base once findings are disseminated(Reference Ostbye, Mann and Vaughn44,Reference Risica, Tovar and Palomo45) . Given the reach of family day care services, access to potentially vulnerable groups and the low levels of activity and poor diets of children attending such settings(Reference Laughlin12,Reference Ward, Vaughn and Burney22) , findings from this review clearly indicate a need for future controlled trials to identify effective obesity prevention interventions in this setting.

This review included two studies reporting on secondary outcomes, both using quasi-experimental designs with parallel control groups. The risk of bias assessment indicated that studies scored mainly ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ risk across the range of criteria it was assessed against. Both de Silva-Sanigorski et al.’s(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell30) community-wide obesity prevention intervention and Trost et al.’s(Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald37) train-the-trainer intervention found statistically significant improvements in family day care providers’ implementation of healthy eating and physical activity environments, relative to control providers. As both studies employed strategies including educational meetings, educational outreach visits and educational materials, this suggests that educational interventions targeting provider’s knowledge, attitudes and skills may be promising to improve the healthy eating and physical activity environments in the family day care setting. Such findings are supportive of Francis et al.(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15) who found that the constructs of Theory of Planned Behaviour (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control and intention) may influence family day care providers’ ability to create environments supportive of healthy eating and physical activity. Future interventions in this setting, evaluated via randomised controlled trial design, using validated observational measures and measuring child’s diet and physical activtiy as well as cost and adverse outcomes are warranted. Further, interventions targeting a broader range of environmental characteristics as identified in the review by Francis, including nutrition and physical activity policies, nutrition feeding practices, communication with parents, availability of play equipment and creative play spaces, may be warranted to increase the overall impact of interventions on child’s diet, physical activity and/or weight status(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15).

Despite a clear need for more research in the area, researchers have identified several unique challenges with undertaking intervention research in the family day care setting. Specifically, this includes large variability in the operations and stability of the setting, the small number of clusters (i.e. each provider may only enrol up to ten children), participation burden in a single-carer environment and increased risk of loss to follow-up of family day care schemes, providers and children(Reference Ward, Vaughn and Burney22). Further, the personal nature of a relationship between family day care providers and the families of children attending care compared to centre-based care could present additional challenges to implementing obesity prevention initiatives(Reference Bromer46). A number of strategies have been suggested to facilitate the conduct of research in this setting, including ensuring recruitment materials are understandable and address barriers to research participation such as lack of time, gaining endorsement from community partners, developing rapport with family day care services; ensuring concerns about participation are addressed; and considering strategies to facilitate parent engagement without jeopardising personal relationships between carers and families(Reference Ward, Vaughn and Burney22).

Although few interventions were examined, findings of this review are important as it highlights gaps in the evidence base and presents clear opportunities for future research in this setting. This review has found no investigations examining the impact of family day care-based interventions on child nutrition, physical activity and weight status measures, and as such, the effectiveness of such interventions on these outcomes is unknown. Additionally, this review provides a high-quality synthesis of the existing evidence base and highlights ongoing research in the area. Such information is valuable to undertake future interventions in this setting. Given the broad eligibility criteria and rigorous search processes, this review presents an accurate overview of the effectiveness of obesity prevention strategies in family day care settings at the time the search was run (March 2019). A future update of this review is needed given the increasing interest in this setting as an avenue to support obesity prevention initiatives and ongoing trials(Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black15,Reference Ostbye, Mann and Vaughn44,Reference Risica, Tovar and Palomo45) .

Strengths and limitations

This review applied high-quality processes in line with those recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration(Reference Higgins and Green24). Given the limited number of studies and heterogeneous outcomes, we were unable to undertake a meta-analyses of study outcomes. Further, the risk of bias for the included studies was judged as ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ for a number of criteria, and findings from this review should be considered in light of such assessments. Non-English studies were excluded from the review, and no systematic search of grey literature was undertaken, which could have resulted in missed studies.

Conclusion

This review has found no controlled trial examining the impact of interventions on child’s diet, physical activity and/or weight status in family day care services. However, two quasi-experimental obesity prevention interventions were found to improve family day care’s healthy eating and physical activity environments. These findings highlight a clear need for future randomised controlled trials measuring the impact on both child outcomes and family day care environments in this setting.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge Debbie Booth for her assistance with developing the search strategy, and Luke Wolfenden for providing feedback on the draft manuscript. Financial support: This study received systematic review pilot funding from the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour, University of Newcastle. Hunter New England Population Health and the University of Newcastle provided infrastructure funding. S.L.Y. is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE170100382). Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.L.Y., J.J. and M.F. developed the review question. S.L.Y., M.L. and L.K.C. developed the search strategy. S.L.Y., M.L., A.G., E.K., M.F., S.M., L.K.C. and K.S. screened the articles. A.G. and M.L. conducted data extraction and risk of bias assessment. S.L.Y. led the drafting of the manuscript, supported by M.L. and T.D. All authors were involved in reviewing the draft manuscript, supporting interpretation of results and final approval of the submitted versions. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this article visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019005275