Modern technology provides access to a plethora of contexts where remembering may take place: a full inbox, a morning video conference, an instant message from a friend, and a quick scroll on a social media timeline. These environments, for better or for worse, dominate day-to-day life for many people, especially after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic when face-to-face interactions became limited. While there is enormous variance in the look, feel, and utility of such contexts, they all fundamentally facilitate some sort of virtual social interaction and have influences on memory (Marsh and Rajaram Reference Marsh and Rajaram2019). A recent surge in cognitive-experimental research has examined how social remembering shapes memory, but this work has focused on in-person situations, leaving questions open about how virtual social remembering takes shape and whether it has the same properties as its in-person counterpart. With the prolific use of technology to share information, we ask – how does social remembering in this new, digital age impact memory? Beyond the influence on the individual, how does digital social remembering shape the formation of collective memory (Barnier and Sutton Reference Barnier and Sutton2008; Hirst and Echterhoff Reference Hirst and Echterhoff2012; Wertsch and Roediger Reference Wertsch and Roediger2008)? And how can psychological research illuminate the influence of online medium for social sharing on memory construction? We approach this question by leveraging an online paradigm to study the patterns of individual versus social remembering in a totally virtual, chat-based setting.

In this article, we discuss through a cognitive-experimental lens the importance and challenges inherent in examining social remembering in completely online settings (Echterhoff Reference Echterhoff2013). Furthermore, we demonstrate with experimental data that social memory research – with equal parts care and creativity – can be advanced to online settings. While previous research has assessed computer-mediated collaborative remembering in chat environments, this work has taken place in the laboratory and therefore in a standard physical environment, often including face-to-face interactions with other participants and the experimenters (eg, Ekeocha and Brennan Reference Ekeocha and Brennan2008; Guazzini et al Reference Guazzini, Guidi, Cecchini and Yoneki2020; Hinds and Payne Reference Hinds and Payne2016, Reference Hinds and Payne2018; but see Gates et al Reference Gates, Suchow and Griffiths2021). However, many virtual platforms, from social media sites to messaging apps, present a completely different context for assessing fully online group remembering. With this framework in mind, we launch a virtual collaborative memory paradigm for online experiments, aimed at implementing a classic, social memory paradigm into a completely virtual environment. We note that this paradigm can also serve well to study individual remembering online, as we show in Experiment 2.

We present two experiments in which the participants joined the experiment remotely and completed all tasks – including collaborative recall – online from their respective, remote locations. To contextualise this approach, we touch on some potential conceptualisations of online social remembering across academic fields. We then review a classic approach used in cognitive psychology – the collaborative memory paradigm. In doing so, we discuss how this cognitive paradigm can inform research across disciplines despite surface-level differences. Finally, we survey prior work on lab-based collaborative remembering and collective memory, highlighting the relationship between collaboration and collective memory, and the critical role collaboration plays in grounding other group-level processes.

Online social remembering

Social interactions, beyond just social remembering, have been completely altered due to the onset of online platforms. In the digital age, people have exponentially more access to the Internet, social networking, and mobile communication, a phenomenon coined the triple revolution (Rainie and Wellman Reference Rainie and Wellman2012). This triple revolution is a global phenomenon, one that has facilitated social interactions at a scale never seen before in human history. People now can connect with others across the globe at any time and exchange information (Marsh and Rajaram Reference Marsh and Rajaram2019). Additionally, the accessibility and availability of mobile devices allow people to be constantly connected to their mobile devices and, in turn, to the Internet and social media accounts (Barnier Reference Barnier2010; Baron Reference Baron2010). Now more than ever, people can connect with others, including strangers, beyond their offline social circles, engage with online social platforms at any moment, and exchange information that normally would not be accessible to them (Chayko Reference Chayko2014). This mass expansion of digital media has also been coined the connective turn, which has shifted memory in numerous ways (Hoskins Reference Hoskins2011).

The digital age has clear influences on how social interactions are facilitated, and consequently, must have implications for online social remembering (eg, Hoskins Reference Hoskins and Hoskins2017; Stone and Wang Reference Stone and Wang2019). Online, or technology-mediated, social remembering can be framed in a variety of ways, making it a rich topic of study across disciplines (Barnier and Hoskins Reference Barnier and Hoskins2018). In cognitive psychology, for example, we may explore if joint remembering on different platforms (eg, text vs. video conferencing) affects memory performance and, if so, what mechanisms are responsible. At the same time, a political scientist might be interested in how online groups translate virtual engagement into real-world mobilisation (eg, Twyman et al Reference Twyman, Keegan and Shaw2017). Likewise, an anthropologist might consider digital landscapes to be areas capable of sustaining broad cultural narratives over relatively long timespans, while a sociologist may focus on how digital artefacts contribute to social cohesion among group members (Agger Reference Agger2008; Pertierra Reference Pertierra2018).

The study of memory in the digital age from a cognitive psychology perspective is relatively new, and it has sparked a profound debate about exactly how the Internet, for better or for worse, has impacted human memory (eg, Carr Reference Carr2008; Schacter Reference Schacter2022). While there is a plethora of studies that have revealed the nature of human memory, and social memory, most of these studies have been conducted in-person outside the context of the Internet and technology (Rajaram and Marsh Reference Rajaram and Marsh2019). Therefore, it is unclear exactly how these studies map onto the nature of everyday memory that often is associated with technology (Storm and Soares Reference Storm, Soares, Wegner and Kahana2021; Wang Reference Wang2019; Yamashiro and Roediger Reference Yamashiro and Roediger2019). Research comparing how memory is studied in the physical laboratory and the expression of memory in the digital world is still in its infancy, motivating many questions about how the Internet influences memory.

Here, it is critical to recognise that there are considerable obstacles that cognitive psychologists must contend with to examine online social remembering. To start, offline memory studies facilitate precise experimental control to help isolate the influence of the experimental manipulation. Virtual studies, however, do not always have that degree of experimental control as participants can be anywhere with access to the Internet throughout the study. Additionally, offline studies typically have an experimenter present to facilitate the session and address questions where online studies do not have an experimenter physically or continuously present to ensure participants are completing tasks correctly. While these are valid concerns with virtual studies that prevent researchers from being able to readily investigate memory processes online, there are also ways to address these issues and conduct experimentally solid studies on virtual platforms (Sauter et al Reference Sauter, Draschkow and Mack2020). For example, experimenters can add instruction checks, add attention checks, and shorten the length of the experimental session. These methods have proven successful in some cases, with some classic studies replicated online (eg, Horton et al Reference Horton, Rand and Zeckhauser2011). The challenges of online experimentation notwithstanding, given that online social networking has become ‘a way of life’, with people having constant, almost unlimited access to online social networks, the time is upon us to examine the properties and consequences of online social remembering. This sentiment has been echoed in recent, related work focusing on the relationship between memory and the self in the age of social media (Wang Reference Wang2022)

Our aim was to ask whether online remembering, both social and individual, encompasses the same properties as the offline counterparts. We briefly discuss the collaborative memory paradigm that we leveraged to create its virtual counterpart, and how its application has contributed to our understanding of social remembering and its downstream impacts on memory. In describing the paradigm, we aim to demonstrate its relevance to research questions in other domains, especially those just described, namely, that the control and flexibility of this paradigm affords insights into the bottom-up processes that shape individual and collective memory.

Collaborative recall and collective memory

Historically, most of human memory research has focused on the individual (Ebbinghaus Reference Ebbinghaus1885). This focus contributed to the development of influential theoretical frameworks that attempt to explain how individuals, working in isolation, remember information (Surprenant and Neath 2009). Bartlett's (Reference Bartlett1932) pioneering work on social memory is an early example of diverging from this path. In many now famous descriptive experiments, Bartlett demonstrated that human memory is subject to social influence. In other fields, such as anthropology and sociology, how societies and groups remember the past has been an active focus of research for many years (Olick Reference Olick1999), whereas in cognitive psychology and cognitive science more broadly, this focus has evolved over time. While influential lines of research have reported on how others may contaminate our memories (eg, Bartlett Reference Bartlett1932; Gabbert et al Reference Gabbert, Memon, Allan and Wright2004; Loftus Reference Loftus1992; Roediger et al Reference Roediger, Meade and Bergman2001), groups and collectives as the unit of measurement have emerged much more recently in cognitive science (Barnier and Sutton Reference Barnier and Sutton2008; Rajaram Reference Rajaram2011; Weldon Reference Weldon and Medin2000).

The relatively recent surge of interest within cognitive psychology in assessing collective cognition can simultaneously draw from and inform research across disciplines (Harris et al Reference Harris, Paterson and Kemp2008; Hirst and Manier Reference Hirst and Manier2008; Wertsch and Roediger Reference Wertsch and Roediger2008). In cognitive psychology, definitions of collective memory have focused on operationalisation in terms of the number of overlapping items recalled independently by all former members of a group. Psychologists have also assessed collective memory with data, showing that people from different countries overclaim the role of their nation for the same historic event such as World War II (Roediger et al Reference Roediger, Abel, Umanath, Shaffer, Fairfield, Takahashi and Wertsch2019). Anthropologists have approached the concept of collective memory at a societal level, examining how groups remember their collective past and how these memories are passed down through generations. For example, Cole (Reference Cole2001) had conducted fieldwork in East Madagascar examining how Betsimisaraka villagers’ social practices preserved memories of their French colonial time period. Similarly, historical studies examine how nations (or cultures) may remember their past (eg, Russia and Georgia's contrasting narratives of the war of August 2008, Wertsch and Karumidze Reference Wertsch and Karumidze2009; Jewish people remembering the origins of their culture, Dudai Reference Dudai, Roediger and Wertsch2022; for a broader commentary, see Wertsch Reference Wertsch, Assmann and Shortt2012) or, in sociology, some researchers are interested in examining how sub-groups within nations come to have contrasting perspectives of their nation's past atrocities (eg, Olick Reference Olick2007; Simko Reference Simko, Roediger and Wertsch2022).

To address the issue of collective memory through a cognitive lens and analyse the bottom-up process that gives rise to shared memory representations, we leverage a collaborative recall framework (for a review, see Rajaram and Pereira-Pasarin Reference Rajaram and Pereira-Pasarin2010; Rajaram Reference Rajaram, Meade, Barnier, Van Bergen, Harris and Sutton2017; for a meta-analysis, see Marion and Thorley Reference Marion and Thorley2016). This approach draws from the collaborative memory paradigm, established in the 1990s by a series of cognitive studies (Basden et al Reference Basden, Basden, Bryner and Thomas1997; Meudell et al Reference Meudell, Hitch and Kirby1992, Reference Meudell, Hitch and Boyle1995; Weldon and Bellinger Reference Weldon and Bellinger1997), where a standard collaborative recall experiment typically entails the following procedure: (1) participants study materials, (2) complete a filler task, (3) recall the study material working individually or in a group, and oftentimes (4) recall the study material again individually. This paradigm offers flexibility for researchers to explore the influence of different study materials, group sizes, and collaboration styles. Moreover, the paradigm can provide insights into how group recall influences subsequent individual memory, affording assessments of post-collaborative memory performance and the emergence of collective memory (Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014; Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014; Rajaram and Maswood Reference Rajaram and Maswood2018). Finally, the collaborative memory paradigm provides a large degree of control over a variety of factors, allowing research to pinpoint the social and cognitive explanations.

Weldon and Bellinger (Reference Weldon and Bellinger1997) were among the first to employ this paradigm in their canonical study. Their key comparisons focused on collaborative versus nominal group recall. Nominal groups – or groups in name only – serve as the baseline and are formed by pooling the non-redundant responses from participants who had worked alone. This provides a fair comparison and is standard practice in this research domain (Basden et al Reference Basden, Basden, Bryner and Thomas1997). One of the most notable findings from this study – of central interest here – was that collaborative groups recalled less than the nominal groups. This effect, referred to as collaborative inhibition, has since been replicated many times in a variety of contexts.

Beyond the collaboration stage itself, collaborative remembering can have a lasting impact on individual memory. Several studies that have implemented post-collaborative, individual recall phases have found that an initial collaborative recall can improve downstream memory (eg, Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014; Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2011, Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014). This improvement is larger than what would be expected if the only mechanism at play is hypermnesia – or improvement in individual recall performance across repeated retrieval attempts (Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2012; Payne Reference Payne1987; Roediger and Butler Reference Roediger and Butler2011; Rowland Reference Rowland2014). One explanation for improved recall following collaboration, over and above standard hypermnesia (Payne Reference Payne1987), is re-exposure. That is, group members can strengthen memories for information reintroduced during collaboration. This can act as a second encoding phase, and this improves recall performance in later retrieval recall attempts (Blumen and Rajaram Reference Blumen and Rajaram2008). Some studies show that group members can also impair memory, producing persistent forgetting evident in later individual memory (Barber et al Reference Barber, Harris and Rajaram2015; also see Cuc et al Reference Cuc, Ozuru, Manier and Hirst2006 for an example of such evidence from a different approach).

As we just described, the effects of group remembering reach beyond collaboration, having downstream effects on individual memory, thereby shaping the collective memory of former group members (Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014; Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014). In cognitive psychology, collective memory is usually indexed by the amount of overlapping content recalled by former members of a group (Cuc et al Reference Cuc, Ozuru, Manier and Hirst2006; Stone et al Reference Stone, Barnier, Sutton and Hirst2010). Not only do former collaborators recall similar material, but they also do so in a similar fashion, reporting items in similar output positions (known as collective organisation, Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014). This additional perspective – examining collective organisation over and above collective memory content – provides a deeper and likely more enduring window into how collaboration synchronises memory for a people. Thus, collaboration facilitates the development of collective memory and homogenises memory structures. In brief, collaboration facilitates the development of collective memory in former group members, such that their memories and the structure of those memories become more aligned with one another.

While the aforementioned effects – collaborative inhibition, post-collaborative recall boosts, and the emergence of collective memory content and structure – are robust in face-to-face collaborative recall settings, we do not know whether collaborative remembering in completely virtual environments would yield similar outcomes. The few studies that include chat-based contexts have reported effects comparable to face-to-face collaborative memory research, including collaborative inhibition, but have found better post-collaborative individual recall in face-to-face groups. This has been attributed to the constraints associated with working in a chat-based environment which, unlike face-to-face collaboration that is laden with non-verbal cues, leads group members to self-filter their responses and/or ignore their partners’ contributions and send duplicates (Clark and Wilkes-Gibbs Reference Clark and Wilkes-Gibbs1986; Ekeocha and Brennan Reference Ekeocha and Brennan2008; Hinds and Payne Reference Hinds and Payne2016, Reference Hinds and Payne2018). Critically, these studies have been situated in lab settings where the use of the electronic chat platform was limited to the individual and collaborative remembering phases. The impact that a fully virtual and remote setting can have on individual and collaborative remembering remains mostly unknown, despite the use of digital platforms that increasingly characterise our educational and social lives.

In light of this background, we explore whether findings from the standard collaborative memory paradigm on the nature of collaborative inhibition, post-collaborative recall, and collective memory for content and structure observed in in-person laboratory settings will generalise to fully online virtual interactions.

The present study

We launch virtual collaborative recall, and report two experiments, to explore individual and collaborative recall in a fully online, chat-based environment. In Experiment 1, our method closely followed the in-person method in Peña et al (Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021, Experiment 1) in terms of stimuli, design, and task sequence, with few exceptions other than all aspects of the procedure being conducted online. Experiment 2, which included several changes from Experiment 1, was designed to follow up on the surprising effects observed in our first experiment.

Drawing from a rich literature on collaborative memory, we developed several hypotheses regarding classic collaborative inhibition, post-collaborative recall, and collective memory. First, based on the reports of the robust findings from in-laboratory collaborative memory experiments, we hypothesised that Collaborative groups would recall less than equal-sized Nominal groups (eg, Basden et al Reference Basden, Basden, Bryner and Thomas1997). The inclusion of a second recall phase in Experiment 1 allowed us to examine how collaborating with others can shape subsequent memory performance. Consistent with previous work, we hypothesised that former Collaborators would recall more than their Nominal counterparts (Blumen and Rajaram Reference Blumen and Rajaram2008; Weldon and Bellinger Reference Weldon and Bellinger1997). Continuing with the assessment of post-collaborative recall, we hypothesised that collective memory would be greater among former collaborators compared to those who did not collaborate before. That is, we expected to replicate the findings from in-laboratory settings that collaborating would lead to individuals recalling more of the same content (eg, Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014; Maswood et al Reference Maswood, Rasmussen and Rajaram2019). Lastly, we assessed whether previous collaborators would have more aligned memory structures as observed in previous studies; here, former group members would not only recall the same information, but they would also organise this information in similar ways when recalling it individually (Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014).

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

Our sample included 96 Stony Brook University undergraduates (M = 19 years, SD = 1.90 years, Range = 17–27 years). Participants were recruited using the Psychology Department's subject pool platform (SONA) and received course credit for their time. This sample size was selected to achieve power of 0.98 based on the collaborative inhibition effect reported in Peña et al (Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021), from which our method was drawn, with an effect size of 1.52 (Cohen's d; Cohen Reference Cohen1992). To prepare for the possibility that the relatively noisier, online testing environment would reduce the effect size, we selected for more power.

Design and procedure

The experiment consisted of two (Recall Condition: Collaborative and Nominal) fully between subjects levels with 48 participants (ie, 16 groups) randomly assigned to each condition. This design and procedure are the standard approach used in collaborative memory studies (eg, Barber and Rajaram Reference Barber and Rajaram2011).

The entire experimental session was conducted online via Qualtrics. After providing consent, participants read instructions for the study phase. Participants were given incidental study instructions, such that they were not informed about later memory tests for the words (eg, Barber et al Reference Barber, Rajaram and Fox2012; Harris et al Reference Harris, Barnier and Sutton2013). Participants were told to rate each word for pleasantness of meaning (1 – very unpleasant to 5 – very pleasant; Craik and Lockhart Reference Craik and Lockhart1972). At study, each word was presented for 6 s, with an asterisk fixation between each word for 1 s. If participants missed a word, the screen automatically advanced. Participants studied a list which consisted of a 90-exemplar list taken from Congleton and Rajaram (Reference Congleton and Rajaram2011) who had drawn the items from Van Overschelde et al (Reference Van Overschelde, Rawson and Dunlosky2004). After the study phase, participants completed a distractor task that required them to list as many United States cities as they could for 7 min.

After completing the distractor task, participants received recall instructions to remember items from the study list. Nominal participants worked alone and were instructed to recall as many words presented earlier as possible, in any order they prefer, in an online chat room for 10 min. Collaborative participants were instructed to complete the same task but were informed they would be working with group members, again all of them online at their respective locations, to recall the studied information. Additionally, Collaborative participants were told to monitor messages from group members to avoid sending duplicate responses. Once all participants of a given triad arrived in the online chat room, they were able to collaborate freely via a chat box for 10 min.

Participants had a 3-min break after the first recall task. After the break, all participants completed a second, individual free recall task for all the studied items (including words recalled during the previous task) for 10 min. Participants were then asked to answer demographic and technology usage questions that were not directly related to the main research question of this study and, therefore, will not be discussed. The entire experiment lasted approximately 1 h.Footnote 1

Results

In this experiment, we assessed individual and collaborative remembering in a totally online, chat-based context. In doing so, we largely co-opted hypotheses from in-person experiments and expected to replicate laboratory findings. Specifically, we hypothesised that (1) Collaborative groups would recall less than equal-sized Nominal groups, (2) collaboration would boost post-collaborative individual recall, relative to those that never collaborate, and (3) collaboration would contribute to the emergence of collective memory content and structure.

For all analyses in this and the next experiment, we chose a cut-off of ±2 SDs for the exclusion of outliers. Our choice was motivated by the online environment; in the laboratory, when participants can be monitored, relatively fringe performance can be classified as reasonable (ie, by confirming no cheating, no intermittent checking of social media). In our experiments, this was not possible. For each analysis, such exclusions were low and did not change the general pattern of results. For all analyses, alpha was set at 0.05 (two-tailed) and Cohen's d (Cohen Reference Cohen1992) was used to assess effect size.

Recall 1 – group recall

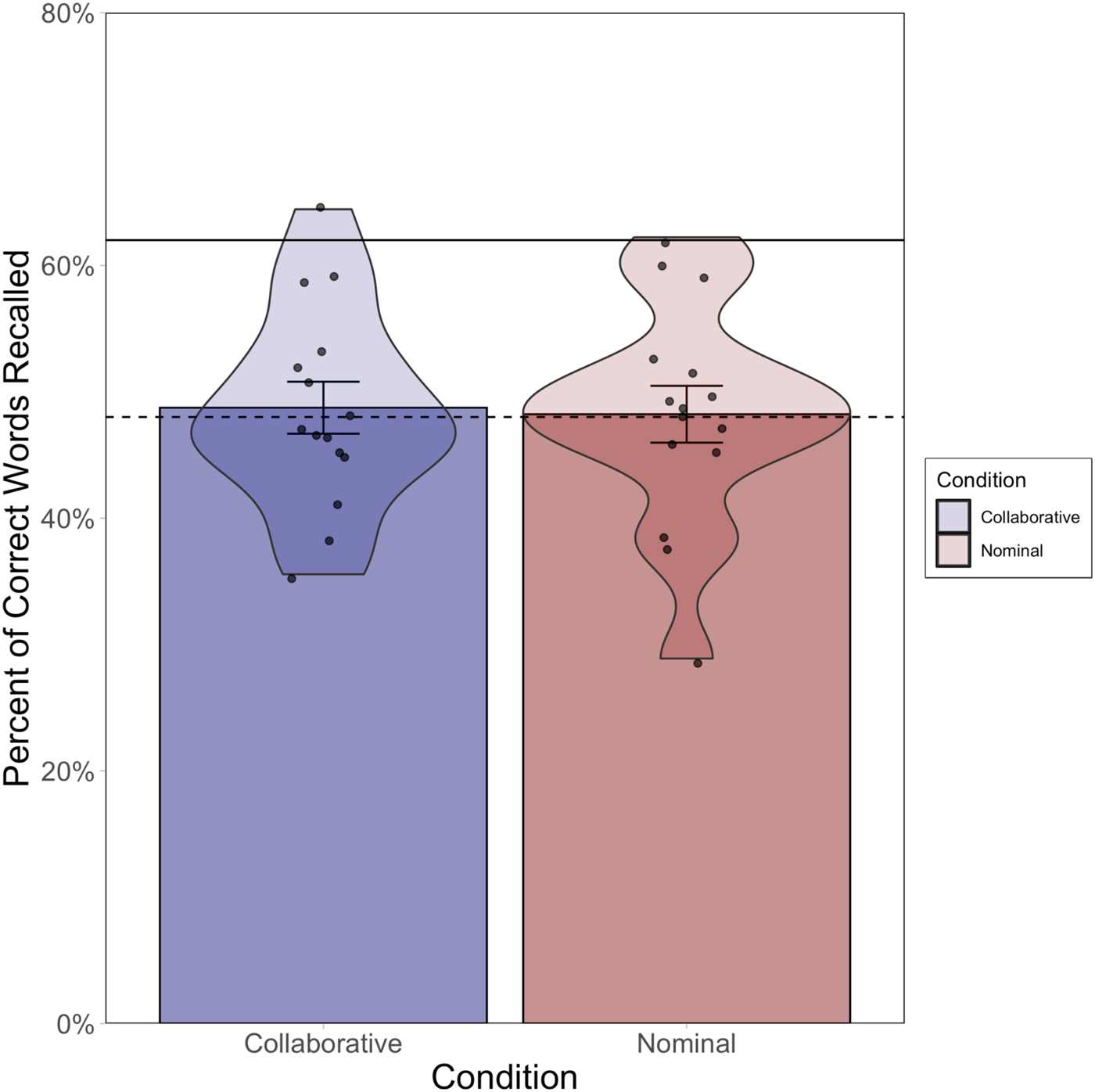

To examine if collaborative inhibition persists in a totally online, chat-based context, we compared the proportion of correct items recalled between Collaborative and Nominal groups. Nominal groups were computed by aggregating the non-redundant recall of three Control participants. An independent sample t-test revealed no significant difference between the conditions, t(28) = 0.17, p = .8661, Difference 95% CI [−5.72 to 6.76%], d = 0.06, d 95% CI [−0.69 to 0.81]. Collaborative group recall (M = 48.74%, SD = 7.96%, n = 15) and Nominal group recall (M = 48.22%, SD = 8.72%, n = 15) were essentially equivalent – see Figure 1. This result – a lack of collaborative inhibition – was surprising and diverged from a large body of work in the collaborative memory literature (Marion and Thorley Reference Marion and Thorley2016). As we note with a reference line in Figure 1, the Collaborative group performance was on par with an in-person study using identical stimuli and the procedure (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021) and other similar in-person research using categorised stimuli (Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2011). In other words, the online platform did not change the levels of collaborative recall compared to the typical levels reported for in-person studies; the impact was seen in the decline of individual recall levels that constituted the Nominal group performance.

Figure 1. Experiment 1 – Recall 1: group-level recall (per cent of correct words recalled). Note: The y-axis is the per cent correct, out of 90 studied words. Bars are at mean and error bars are SEM. Individual points and the overlaid distributions represent the underlying data (n = 15 triads of participants in each condition). Horizontal reference lines are from an in-person experiment using the same stimuli and procedure where we observed collaborative inhibition (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021). The dashed line is collaborative performance from that study, and the black solid line is Nominal performance. Note that Collaborative group recall is nearly even with levels observed using the same procedure in the laboratory, whereas Nominal recall is well below laboratory performance.

Recall 2 – individual recall

We also wanted to see how online collaboration affects memory downstream. We found that former collaborators recalled more correct items (M = 32.49%, SD = 10.57%, n = 45) than those that never collaborated (M = 22.41%, SD = 9.85%, n = 47). This difference was statistically significant (independent samples t-test: t(90) = 4.74, p < .001, Difference 95% CI [5.85–14.31%], d = 0.99, d 95% CI [0.55–1.43]). This finding, depicted in Figure 2, is consistent with previous work, demonstrating that collaboration can boost subsequent individual recall performance (eg, Bärthel et al Reference Bärthel, Wessel, Huntjens and Verwoerd2017; Blumen and Rajaram Reference Blumen and Rajaram2008; Nie et al Reference Nie, Ke, Li and Guo2019; Weldon and Bellinger Reference Weldon and Bellinger1997).

Figure 2. Experiment 1 – Recall 2: individual-level recall (per cent of correct words recalled). Note: The y-axis is the per cent correct, out of 90 studied words. Bars are at mean and error bars are SEM. Individual points and the overlaid distributions represent the underlying data (Collaborative n = 45; Nominal n = 47). Horizontal reference lines are from an in-person experiment using the same stimuli and procedure (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021). The dashed line is former collaborative individual performance from that study, and the solid line is Nominal individual performance.

Nominal participant hypermnesia

To further assess the low recall performance during the first recall in the Nominal condition, we analysed the within-subject change from Recall 1 to Recall 2. If low performance was driven largely by a failure to follow task instructions rather than by lowered engagement, we would expect little change between the two phases. However, if recall performance improved between phases, a small improvement of hypermnesia typically observed in successive recalls (hypermnesia; Payne Reference Payne1987), it means that participants did not entirely ignore the task but instead that they were not fully engaged. Indeed, performance improved from Recall 1 (M = 18.91%, SD = 8.09%, n = 45) to Recall 2 (M = 21.80%, SD = 9.61%, n = 45), and this improvement was statistically significant (paired-samples t-test: t(44) = −3.96, p < .001, Difference 95% CI [−4.36 to −1.42%], d = −0.31, d 95% CI [−0.47 to −0.15]). These results suggest that Nominal participants do not perform at their normal standard as they would in the laboratory despite this small boost in performance.

Collective memory – content

Including a second recall phase allowed us to examine collective memory. To assess this, we calculated the overlap in recall, ie, items recalled by all former members of a group (Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014). Former collaborators, ie, participants who were collaborative group members earlier, recalled more of the same material (M = 10.56%, SD = 3.56%, n = 14) than did members of Nominal groups (M = 2.50%, SD = 2.24%, n = 16). This difference was statistically significant, t(28) = 7.52, p < .001, Difference 95% CI [5.86–10.25%], d = 2.75, d 95% CI [1.71–3.80]. This finding is depicted in Figure 3 and replicates the in-person finding that collaboration promotes collective remembering (Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014; Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021).Footnote 2

Figure 3. Experiment 1 – recall 2: collective recollection (per cent of correct words collectively recalled). Note: Collective memory was calculated by dividing the total number of items remembered by all previous group members during their second, individual recall by the number of items possible (90). Bars are at the group means, error bars represent SEM, individual points are group-level proportions, and the overlaid shapes describe the distribution of the data in each group.

Collective memory – structure

We used the Shared Organization Metric Analysis (SOMA – see Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014 for a detailed treatment) to assess the collective similarity in how former group members organised their later individual recall. SOMA, based on Pair Frequency (PF – Sternberg and Tulving Reference Sternberg and Tulving1977), assesses the number of adjacent forward and backward word pairs reported by previous group members in subsequent, individual recall phases. A score of 0 indicates a chance number of pairs across group members. Former collaborative group members exhibited more similarity in the way they organised their recall (M = 2.07, SD = 1.17, n = 15) than Nominal group members that never collaborated (M = 0.46, SD = 0.55, n = 16). Because of restricted variance in the Nominal condition (scores clustered around 0; Levene's test for equal variances: F(1,29) = 6.64, p = .0153, we used a Welch two-sample t-test to compare conditions, which was statistically significant, t(19.64) = 4.84, p < .001, Difference 95% CI [0.91–2.29], d = 1.78, d 95% CI [0.91–2.64]). This relationship is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Experiment 1 – recall 2: collective memory structure measured with SOMA. Note: SOMA scores in each condition, as defined by Congleton and Rajaram (Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014). A score of 0 indicates chance level shared organisation, whereas higher scores indicate greater shared organisation. Bars are at the group means, error bars represent SEM, individual points are group-level scores, and the overlaid shapes describe the distribution of the data in each group.

Discussion

How does a fully online, chat-based environment shape the nature of collaborative remembering and emergence of collective memory? We launched a virtual collaborative memory paradigm in a fully online environment to explore this question. Building from a rich history of in-person collaborative memory research, we hypothesised that (1) Collaborative groups would recall less than equal-sized Nominal groups, (2) collaboration would boost post-collaborative individual recall, relative to those that never collaborated, and (3) collaboration would contribute to the emergence of collective memory and collective organisation.

Surprisingly, we did not observe collaborative inhibition when comparing the recall of Collaborative groups to the Nominal groups. This finding diverges from the previous literature that reports a robust, collaborative inhibition effect in studies conducted in the laboratory (Marion and Thorley Reference Marion and Thorley2016). Why did we observe this null effect? First, Collaborative participants could have been paying less attention to their group members’ items throughout the collaborative session than typically the case in in-person situations which caused less impairment in their own recall. This explanation is not supported, however, because Collaborative participants exhibited re-exposure benefits gained during collaboration in their second, individual recall as evidenced by higher recall by those who collaborated earlier compared to those who did not (Blumen and Rajaram Reference Blumen and Rajaram2008). Second, the remote environment could have encouraged shallower learning during the presentation of the study words than the in-person context, which made collaboration less disruptive than we typically would observe in the laboratory (Pereira-Pasarin and Rajaram Reference Pereira-Pasarin and Rajaram2011). We ruled out this explanation because the recall performance of our collaborative triads was comparable to the recall performance of the in-person collaborative triads reported in a study with the same method that we conducted in person in the laboratory for a different purpose (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021). Lastly, it is possible that Nominal participants – working alone – were less engaged with this remote setting, which lowered their recall. This final explanation is the most likely considering our chat-based Nominal groups recalled far less than in-person Nominal groups that recalled the same stimuli (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021). Specifically, this explanation is supported by previous work using the same study materials and procedure, which found that Nominal individuals recall approximately 30 per cent of the study list – whereas our Experiment 1 Nominal groups recalled about 18.92 per cent of the study list (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021). This indicates that individual memory performance, not collaborative group performance, is most impacted by the fully online, chat-based environment. We follow up on this explanation in Experiment 2.

We examined differences in Recall 2 both at the individual and collective levels, to examine the nature of post-collaborative performance in online settings. Participants who collaborated earlier outperformed Nominal participants in their individual recall performance in Recall 2 which suggests that they benefited from re-exposure benefits. Additionally, consistent with previous research (Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014; Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014), former collaborators recalled more of the same items than participants that never collaborated. This indicates that virtual collaboration contributes to the development of collective memory, just like face-to-face collaborative recall.

In summary, our findings reveal that some properties of fully online, chat-based collaboration are the same as laboratory-based collaboration, while other properties are different. Like previous studies, we observed that collaboration can homogenise memory representations and structures of previous group members, which leads to the emergence of collective memory for content. What is novel to our study is that our control participants recalled less than what we typically observe in-person, which diluted collaborative inhibition. So, then, it seems that the question is not, how does remote, chat-based collaboration differ from standard collaborative remembering, but how does remote, chat-based individual remembering differ from standard individual remembering? This insight about the impact of the digital world on individual and collective memory was illuminating. We followed up this question in our next experiment.

Experiment 2

Our candidate explanation for the lack of collaborative inhibition in Experiment was that Nominal participants were less motivated to complete the task alone under online conditions and, therefore, did not complete it to their full potential. In laboratory contexts, all distractions would be removed, and the experimenter would be physically present to encourage engagement with the task at hand. These factors do not feature in standard remote, online situations and were not present in the current study for those participants who had to perform the task working individually. We tested this explanation by creating conditions where participants would be more motivated to sufficiently complete the recall task while working individually.

This idea of reduced motivation is similar to the notion of social loafing in which people defer responsibility to others and put forth less effort (Latané et al Reference Latané, Williams and Harkins1979). Weldon et al (Reference Weldon, Blair and Huebsch2000, Experiment 2) tested a possible role of social loafing during collaborative recall by creating conditions in which participants would have higher expectations for their own recall performance and, in turn, would be less likely to coast through the task. Specifically, participants were given information about other participant's ‘typical performance’, which was actually 2.5 times the typical performance the authors observed in their Experiment 1, and were told that they should take their best guess to reach that recall threshold. This ‘forced recall’ task (Erdelyi et al Reference Erdelyi, Finks and Feigin-Pfau1989; McKelvie Reference McKelvie2001) aimed to reduce social loafing and evaluation apprehension (Diehl and Stroebe Reference Diehl and Stroebe1987) by providing participants with a high criterion for performance and encouraging guessing. These instructions improved individual recall for participants in their control, Nominal condition while leaving the performance of participants in the collaborative condition unaffected and still elicited collaborative inhibition in group recall. For present purposes, these results also show a way to increase motivation for Nominal participants.

We built off the work done by Weldon et al (Reference Weldon and Medin2000) to test if lack of motivation influenced low Nominal performance in our first experiment. We made the following modifications to ensure that participants were sufficiently motivated to complete the task to their full potential: (1) participants were given ‘forced’ recall instructions adapted from Weldon et al at the start of the recall phase which provides ‘other participants’ typical performance’; (2) participants were told at study that they would eventually complete an unspecified memory task; (3) the experimenter established presence by re-sending the recall instructions at the start of each recall in the chatroom; and (4) participants studied a shorter word list. Therefore, if our initial null findings for group recall were caused by lack of motivation in the Nominal condition, then we expect to observe collaborative inhibition under these modified conditions.

Method

Participants

Our final sample included a new group of 90 Stony Brook University undergraduates (M = 20.1 years, Range = 17–30 years). This sample size was selected to achieve power of 0.95 based on the collaborative inhibition effect reported in Choi et al (Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014; the project from which our study list was drawn) with an effect size of d = 1.38. Participants were recruited using the Stony Brook University Psychology Department's subject pool website and received course credit or Amazon Gift-Cards ($5) for their time.

Design and procedure

As in Experiment 1, we implemented a 2-level (Recall Condition: Collaborative and Nominal) between subjects design with 45 participants (ie, 15 groups) per condition.

After providing consent, participants were given instructions for the study phase. The instructions for the study task matched Experiment 1 in all respects, except participants received intentional study instructions where they were informed that there would be a memory test for the words as this more closely matched the instructions from Weldon et al (Reference Weldon and Medin2000). Participants independently studied 50 unrelated nouns (two primacy buffers, two recency buffers, and 46 targets), a shorter study list compared to Experiment 1, which were drawn from another in-person study on collaborative recall we have conducted (Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014). These words were originally selected from Clark and Paivio (Reference Clark and Paivio2004). Participants next performed a distractor task that lasted 3 min. For this task, we chose the online Snake game (Pepe et al Reference Pepe, Wang and Rajaram2021) so as to differentiate further than before the task demands between this task and the subsequent recall task of interest.

Like Experiment 1, participants completed either an individual free recall task or a collaborative recall task after the distractor phase. The instructions for both conditions were the same as Experiment 1, with one important change. Participants in both conditions were asked to recall the studied items in any order that they prefer, but the Nominal participants were told that people typically recall at least 24 items and Collaborative participants, who worked in groups of three, were told that groups typically recall at least 35 words. These numbers translated to 1.5 times the items recalled on average in these conditions in Choi et al (Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014). These instructions are modelled after the instructions used in Weldon et al's (Reference Weldon, Blair and Huebsch2000) Experiment 2 to encourage more engagement.Footnote 3 At the start of the recall session, all participants received their respective set of instructions on the screen and as a message from the experimenter at the start of the recall phase. Participants completed their respective task either individually or collaboratively for 10 min. Given the goals of Experiment 2 that focused on examining collaborative recall per se, we included only one recall session. Participants then completed the same set of survey questions as in Experiment 1 and were then debriefed and compensated. The entire procedure lasted approximately 30 min.

Results and discussion

The goal of this experiment was to examine how collaboration influences memory performance when engagement, likely lower in online settings, is increased. We addressed this goal by setting a high standard for performance for participants working individually in a remote, chat-based environment.

An independent samples t-test to examine group recall performance revealed a significant difference between Nominal groups (M = 63.77%, SD = 9.81%, n = 15) and Collaborative groups (M = 54.64%, SD = 12.80%, n = 15), t(28) = −2.20, p = .037, Difference 95% CI [−17.66 to −0.60%], d = −0.80, d 95% CI [−1.58 to −0.02] (see Figure 5). In summary, we found that with improving the conditions for engagement, with the combination of intentional encoding instructions, setting a high-performance standard for recall, and adding experimenter presence at recall, restored collaborative inhibition in chat-based, remote environments.

Figure 5. Experiment 2: group-level recall. Note: The y-axis is the per cent correct, out of 46 studied words. Bars are at mean and error bars are SEM. Individual points and distributions represent underlying data (n = 15 in each condition). Horizontal reference lines are from an in-person experiment using the same stimuli and a similar procedure (Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014 – Recall 1). The dashed line is collaborative group performance from that study, and the solid line is Nominal performance.

Discussion

We found that a collaborative inhibition effect also emerges in a remote, chat-based environment, which is in line with previous research using the instructions we implemented in this study (Weldon et al Reference Weldon and Medin2000), along with additional measures to promote engagement. These findings support our initial explanation that control participants, working alone in a remote environment, were simply putting forth less effort into the free recall task which diluted our group comparisons in Experiment 1. Furthermore, these results are consistent with in-person research using similar stimuli (Blumen and Rajaram Reference Blumen and Rajaram2008; Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014). While we cannot isolate which manipulation(s) from Experiment 1 to Experiment 2 led to the jump in control performance, it is clear that some or all of the carefully considered changes to increase task engagement that we implemented are needed to calibrate individual performance in online settings – a shorter study list, intentional study for a later test, removing the overlap in the demands of an intervening task and the target memory task, setting a higher bar for recall, and experimenter presence in the chatrooms. Our results are intuitive and support the reasoning about decreased motivation underlying the poor control performance in remote settings when people work alone. Nonetheless, given the variable nature of online performance, evolving online platforms, and the current work-from-home demands, we recommend interpreting these results with caution as well as replication to ascertain the reliability of online remembering.

General discussion

In this study, we launched the collaborative recall paradigm into a completely virtual, chat-based setting. Novel to the current study, we found that remote, chat-based collaboration can facilitate the emergence of collective memory, similar to in-person collaborative remembering. Likewise, collaborative memory performance, in general, was similar to in-laboratory performance and former collaborators exhibited the expected post-collaborative recall boost. By contrast, control recall, that entailed individuals recalling alone instead of in groups, was numerically lower in Experiment 1 than in an in-person study using the same stimuli and general procedure (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021).

Perhaps, the most striking finding we report is the vanishing – and reappearance – of collaborative inhibition across the two experiments. In Experiment 1, collaborating groups performed equally well as in-person collaborative groups recalling the same stimuli (Peña et al Reference Peña, Pepe and Rajaram2021). However, control performance suffered. In fact, relative to Peña et al and Congleton and Rajaram (Reference Congleton and Rajaram2011), individual recall performance was a full standard deviation below in-laboratory performance. We posit that motivation, generally defined, was reduced in this context for those working alone to perform the recall task, and that this reduction could stem from a variety of sources (eg, task length and lack of supervision), and Experiment 2 supports this idea. We designed our second experiment to address a range of factors that could be responsible for such a reduction (ie, intentional encoding, ‘forced’ recall instructions, shorter word list, and experimenter presence). With these procedural adjustments, individual/Nominal group recall returned to levels consistent with laboratory-based research (Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014).

Why would there be a differential motivation reduction between conditions? Given that in both experiments, Collaborative recall was approximately even with in-person performance we have observed in other, in-person studies, it is possible that the social component – being told just before recall that one will be working in a group – increased engagement and motivation. Conversely, when working individually in a remote and perhaps isolated context, there may be little incentive to recall more than a handful of items. This would amount to a reverse social loafing effect. Such an effect would also be exacerbated, though not completely explained, by completing longer and/or more intensive tasks virtually. If task length/intensity was solely at play, Collaborative performance would have suffered as well. In Experiment 2, designed specifically for ease and to afford individuals every opportunity to perform to their full potential, we observed collaborative inhibition. Our explanation of a reverse social loafing effect is consistent with evaluations of the ways in which constant access to online media and digital technology can create memory lapses and distortions where, for example, media multitasking can produce attentional lapses and undermine memory for target information (Marsh and Rajaram Reference Marsh and Rajaram2019; Schacter Reference Schacter2022; Wammes et al Reference Wammes, Ralph, Mills, Bosch, Duncan and Smilek2019)

In addition to providing an approach to assess collaborative inhibition online, we examined the emergence of collective memory. Several in-laboratory studies have established the role collaboration plays in reshaping individual memory, such that, following collaboration, former group members recall more of the same information (Choi et al Reference Choi, Blumen, Congleton and Rajaram2014; Congleton and Rajaram Reference Congleton and Rajaram2014). Experiment 1 extended this finding to a totally virtual, online setting. Together, these findings indicate that while some memory phenomena generalize across offline and and online memory studies, notable differences also emerge across these contexts.

Concluding thoughts

Online socialisation and social remembering

People socialise for many reasons online. Beyond education, social media and other platforms offer users the opportunity to connect and engage with others – to share news, seek information, debate, express opinions, and more. Our findings relating to collective memory may have implications for such general online engagement. While we examined collective memory for basic stimuli following collaboration between strangers, it is possible that similar effects will emerge naturally in existing social networks. For example, if one is repeatedly engaging with the same individuals online, it is possible that they will come to remember similar material. If collective memory is predictive of individual or group-level attitude formation, decision making, or other outcomes, understanding the mechanisms by which these memories emerge and evolve is critical (Garagozov Reference Garagozov, Roediger and Wertsch2022; Rajaram et al Reference Rajaram, Peña, Greeley, Roediger and Wertsch2022).

Applied implications for remote education and work

The data presented here shed light on the social and cognitive factors that underpin many virtual learning tasks. While the COVID-19 pandemic has forced the abrupt adoption of remote learning and education, virtual learning is not new (Farrell Reference Farrell1999). Likewise, while many institutions are transitioning back to face-to-face instruction at the time of this writing, virtual education will continue to supplement curriculums. Finally, beyond formal academic settings, independent learners have and will continue to harness the Internet to pursue knowledge in many domains.

Our findings suggest that learning in virtual settings may be sensitive not only to collaboration, but also other aspects of the experience that may be less critical in-person. For example, Experiment 1 revealed that – unlike in face-to-face contexts – Nominal group memory performance may drop. Conversely, Experiment 2 results suggest that individual memory performance can parallel in-person performance, given the right combination of factors. Directly assessing what these results mean for educational outcomes would require conceptual replication with more naturalistic materials, and the present study provides a prototype for such exploration. As such, the present study illustrates how basic collaborative memory research can extend to virtual settings where this learning takes place. Our findings suggest the possibility that collaboration may serve as an even more important pedagogical practice in online learning than for in-person learning (Pociask and Rajaram Reference Pociask and Rajaram2014).

Beyond educational pedagogy, the assessment of virtual collaboration demands attention to how it is distinct from face-to-face collaboration for a variety of reasons. The assessment of the nature of virtual collaboration, and virtual learning in general, applies not only to platform-specific features that constrain communication in different ways (Kraut et al Reference Kraut, Fussell, Brennan, Siegel, Hinds and Kiesler2002), but also to why people are collaborating. That is, over and above technical affordances, virtual collaboration may have different goals than face-to-face collaboration, such as time constraints for people with financial or family obligations, disabled individuals who may thrive in online but not in-person learning environments, geographic lack of local access to the same learning opportunities as those available online, and beyond.

Similarly, communication preferences may influence the way people use online platforms to collaborate with others. For example, while people across the adult lifespan now use mobile messaging apps, younger adults exhibit a stronger preference for such texting compared to older adults (Pew Research Center 2015). Research shows differences in the manner of usage as well: children commonly use textese and textism (omission of words and nonstandard, abbreviated use of words) when communicating with others through online texting, although this usage does not have a negative impact on their grammar and other literacy abilities, or executive function abilities (Plester et al Reference Plester, Wood and Joshi2009; van Dijk et al Reference Van Dijk, Van Witteloostuijn, Vasić, Avrutin and Blom2016; Wood et al Reference Wood, Kemp, Waldron and Hart2014). Older adults often prefer specific addressee details and no emoticons (Kuerbis et al Reference Kuerbis, van Stolk-Cooke and Muench2017). How age differences for these and other online communication preferences can impact memory across age would be interesting to explore.

In the contexts we just described, what constitutes ‘successful’ collaboration may come down to what collaborative groups aim to optimise. For example, face-to-face collaboration studies report that groups collaborate to optimise recall accuracy levels (Harris et al Reference Harris, Barnier and Sutton2012; Weldon et al Reference Weldon and Medin2000; Experiment 1), or they may focus on regulating the emotions they felt towards the to-be-remembered information (Maswood et al Reference Maswood, Rasmussen and Rajaram2019). The variety of reasons people may collaborate in virtual settings and the goals they prioritise when doing so may differ in similar ways, making investigations about the memory consequences in virtual settings a fruitful topic for future research.

More generally, we take note of several advantages of examining social remembering in virtual environments. Notably, the collaborative recall paradigm is robust and allows us to isolate the influences of specific cognitive mechanisms. Furthermore, while striking findings, such as collaborative inhibition, have been largely tested in laboratory settings with controlled learning materials and procedures, this phenomenon has been also observed for more naturalistic to-be-remembered information such as movies and real-life incidents (Wessel et al Reference Wessel, Zandstra, Hengeveld and Moulds2015; Yaron-Antar & Nachson Reference Yaron-Antar and Nachson2006) and in more naturalistic conditions involving life experiences (eg, married couples remembering shared trips, Harris et al Reference Harris, Barnier, Sutton, Keil and Dixon2017). As such, understanding this as well as a range of social memory phenomena on virtual platforms holds considerable promise. In this vein, future research should consider not only the technical features of virtual collaboration and virtual learning in general, but also the motivational and task-specific features that can make both the individual and collaborative performance online distinct from their face-to-face counterparts. Given the dimensions on which these online versus face-to-face features can vary, such explorations will benefit from a coordinated, interdisciplinary approach.

Going beyond chat-based recall and scaling up to social network platforms

We explored chat-based social remembering in a fully online context, but exploring other communication mediums would have both basic and applied value. In a basic research context, examining the timing, availability, and medium of group member input could reveal more about how information disrupts or potentiates cognitive processes. In an applied context, understanding how individual and group memory changes on different platforms would be valuable in many domains. For example, modern video conferencing provides a range of features and options. One can join a meeting or class with or without video, use only chat, record for later viewing, generate a transcript for later review, and display subtitles to supplement audio. The novel approach we present here is flexible enough to be adapted to a variety of paradigms. Future work can leverage this flexibility to widen the exploratory scope. For instance, access to social media trace-data allows researchers to ‘scale up’ research and the unit of analysis (Marsh and Rajaram Reference Marsh and Rajaram2019; Risko Reference Risko2019). Alternatively, researchers can map established paradigms onto these new environments incrementally. The methods we introduce here provide an experimental approach that is grounded by cognitive theory to explore these options.

Data availability statement

The data reported in the current manuscript will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jasmine Mui and Vanessa Chan for their research assistance and Dr. Lauren L. Richmond for feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Financial support

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship 1839287 and the National Science Foundation Grant 1456928.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/mem.2022.3

Suparna Rajaram is SUNY Distinguished Professor of psychology and former Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs in the College of Arts and Sciences at Stony Brook University. She studies human memory, including the psychological mechanisms of memory transmission, collaborative remembering, and collective memory, memory and ageing, and memory disorders.

Tori Peña is currently a fourth-year, doctoral candidate in Cognitive Science at Stony Brook University. She received her B.S. in Psychology and Biological Anthropology from Binghamton University in 2018. She is currently studying collaborative memory, collective memory, and collective future thinking.

Garrett Greeley is currently a third-year doctoral student in Cognitive Science at Stony Brook University. He received his B.A. in Psychology from Winona State University in 2018. He is currently studying collective memory, collaborative memory, and retrieval dynamics.