INTRODUCTION

A government’s legitimacy is a crucial asset. Dahl (Reference Dahl1971), for example, argues that without legitimacy a government is likely to collapse. This is because legitimacy, which can be defined as “the normative belief by an actor that a rule or institution ought to be obeyed” (Hurd Reference Hurd1999, 381), makes it easier to rule. This study examines the impact of state support for religion on governments’ legitimacy.

This relationship is important to understand because many countries enact practices and laws that endorse and materially support certain faiths. About one in four countries in the world today have an official state religion, such as the United Kingdom or Iran. A similar share has a favored religion without designating it as the official religion (Fox Reference Fox2015), such as the Roman Catholic Church in Spain and Italy (Masci Reference Masci2017). What is the effect of this relationship between religion and state on government legitimacy?

We are aware of no empirical studies on the topic and with some notable exceptions (e.g., Hoffman Reference Hoffman and Thompson2019; Turner Reference Turner1991), few studies directly address the topic. Most studies that address the issue do so in passing or as part of a larger argument focused on other issues such as religious freedom, conflict, populism, and political mobilization, among other topics of study (e.g., Deitch Reference Deitch2020; Lincoln Reference Lincoln2003; Sandal Reference Sandal2021b). However, when the issue of why a government would support religion is addressed, few studies dispute the proposition that governments hope to gain legitimacy because of this support. This is not to say that religion cannot be used to undermine a government’s legitimacy or support the opposition’s legitimacy. It clearly can. Rather, we address the argument that governments that support religion, do so intending to gain the benefit of increased legitimacy (Gill Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008) and test whether that expectation is realized.

Some argue that this legitimation often occurs in fact. For example, Bellah (Reference Bellah1978, 16) argues that “through most of Western history some form of Christianity has been the established religion and has provided ‘religious legitimation’ to the state.” Similarly, Juergensmeyer (Reference Juergensmeyer1993, 3) argues that “coopting elements of religion into nationalism … provides religious legitimacy for the state; and it helps to give nationalism a religious aura.” That being said, religion’s legitimation function can be used to bolster both a government and its opposition. This legitimation of the opposition tends to occur either as a competing claim to religious legitimacy or in cases where the government is not particularly supportive of religion (Driessen Reference Driessen2014b; Juergensmeyer Reference Juergensmeyer1993; Lincoln Reference Lincoln2003) such as in the case of the Catholic Church’s support for the Solidarity movement’s opposition to Poland’s Communist government in the 1980s (Goldstone, Gurr, and Moshiri Reference Goldstone, Gurr and Moshiri1991, 149–50).

This support–legitimacy relationship is potentially more complex because in the expanding field of religion and politics, a diverse set of arguments are emerging that imply that supporting a religion may not increase a government’s legitimacy. These interrelated literatures do not focus on the support–legitimacy relationship and in most cases do not directly address a government’s legitimacy at all. Rather, they focus on issues such as secularism and why people are religious (e.g., Finke Reference Finke1990; Reference Finke2013; Kuru Reference Kuru2009; Toft, Philpott, and Shah Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011). Nevertheless, we posit that three arguments in this literature have clear implications for the support–legitimacy relationship.

First, the increasing popularity of political secularism may undermine the legitimacy of state support for religion. Political secularism is a diverse family of ideologies where positive interpretations mandate that separation of religion and state is beneficial to both government and religion and negative interpretations seek to limit religion’s role in the public sphere (Kuru Reference Kuru2009; Toft, Philpott, and Shah Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011). Supporters of both interpretations of secularism would likely see state support for religion as illegitimate. Second, the supply-side theory of religion posits that religion is more likely to thrive in a climate of separation of religion and state. This implies that religious people may prefer separation of religion and state over state support for a religious monopoly because it is more beneficial to their religion. Also, positive secularism is gaining popularity among religious people, likely precisely because religion thrives under regimes with a separation of religion and state. Third, state support for religion often results in state control over that religion which can cause many believers to feel that the government-controlled version of their religion is inappropriate and unauthentic.

This study draws upon the Religion and State (RAS) and World Values Survey (WVS) datasets to test the relationship between support and legitimacy. We construct our sample with all Christian-majority countries surveyed in the WVS between 1990 and 2014, resulting in 54 countries and 126 country years. We find that overall state support for religion is associated with lower levels of confidence in government and legislative bodies. However, we find that different types of state support for religion have different relationships with confidence in government. Specifically, state enforcement of some religious precepts, particularly restrictions on abortion and homosexuals, has a positive relationship with state legitimacy, while state funding for religion and entanglement with religion has a negative relationship with state legitimacy.

We make several contributions. First, to our knowledge, this is the first quantitative test of the relationship between state support for religion and government legitimacy. Our findings suggest a serious flaw in the assumption that state support for religion increases legitimacy. Second, we provide a theoretical foundation for understanding why this is the case. Third, we build upon a large body of research that seeks to understand the sources of states’ legitimacy. Socioeconomic factors, such as economic growth (Clarke, Dutt, and Kornberg Reference Clarke, Dutt and Kornberg1993) and welfare gains (Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991), as well as political factors such as political stability (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2005), control of corruption (Seligson Reference Seligson2002), and democratic rights (Diamond Reference Diamond1999) have all been found to be boons to states’ legitimacy. In investigating an unexplored influence on governments’ legitimacy—that of state support for religion—we shed additional light on the pillars of states’ legitimacy and find that ideologically driven policies may have complex consequences for a government’s legitimacy.

CLASSIC RELIGIOUS LEGITIMACY THEORY

The argument that religion can influence the legitimacy of governments, as well as nearly any political body, policy, or action, is uncontroversial. Fox (Reference Fox2018, 60) argues that “the ability of religion to both enhance and undermine the legitimacy of a government, a policy, political actors, and political institutions, among many other things, is arguably among the most uncontroversial propositions in political science.”

There is a strong body of theory supporting this contention. In fact, for much of Western history, religious legitimacy was a precondition for ruling. For example, European Kings ruled by divine right. That is, God was seen as granting the King the right to rule, and this authority was actively supported by the church. Today most governments have replaced this “descending” theory of legitimacy with an “ascending” one where they derive much of their legitimacy through popular consent rather than divine right (Bellah Reference Bellah1978, 16, 17; Toft, Philpott, and Shah Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011, 55–6; Turner Reference Turner1991, 178–83). Yet even in this “ascending” context, religion can still be an important potential source of legitimacy, particularly when there is considerable popular support for religion or for a government policy that supports religion (Fox Reference Fox2015; Reference Fox2018).

However, some like Juergensmeyer (Reference Juergensmeyer1993) argue that Western secular ideologies are losing popularity in parts of the developing world, which has led to an increased popularity of the “descending” theory of legitimacy. He argues that factors including the failure of governments founded on secular-nationalist ideologies such as liberalism, socialism, and communism to produce economic prosperity and social justice and the perceived foreignness of these ideologies have led to a legitimacy vacuum where indigenous religions, which he argues are inherently legitimate, are gaining popularity as a potential basis for government. He posits that this explains a rise of religious rebellion and terror. Toft, Philpott, and Shah (Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011) argue that many of these secular-nationalist ideologies, in addition to being anti-religious, were also top-down and anti-populist, which may have contributed to their lack of legitimacy. While in most such countries, religious opposition and rebels have not succeeded in gaining power, many governments are increasing their support for religion in order to preempt religious-based attempts to undermine their legitimacy (Fox Reference Fox2015; Schleutker Reference Schleutker2021, 211).

Be that as it may, there are few studies that focus explicitly on the role of religious legitimacy in politics, though this argument is present in textbooks on the topic (e.g., Fox Reference Fox2018; Hoffman Reference Hoffman and Thompson2019; Turner Reference Turner1991). Most studies that address religious legitimacy in politics do so in other contexts where the role of religious legitimacy is an element of an argument focusing on another topic. These studies, which mostly focus on some aspect of religion and politics, commonly assert that religion is capable of supporting (or undermining) the legitimacy of governments and their opposition (Arjomand Reference Arjomand1993, 45; Assefa Reference Assefa1990, 257; Berryman Reference Berryman1987, 126; Billings and Scott Reference Billings and Scott1994; Cosgel et al. Reference Cosgel, Histen, Miceli and Yildrim2018; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2007, 914; Lincoln Reference Lincoln2003; Williamson Reference Williamson1990, 243), leaders (Barter and Zatkin-Ozburn Reference Barter and Zatkin-Ozburn2014, 190; Brasnett Reference Brasnett2021, 43; Cingnarelli and Kalmick Reference Cingnarelli and Kalmick2020, 940; Ives Reference Ives2019; Saiya Reference Saiya2019b) and other political activities and phenomena such as conflict, terrorism and violence (Appleby Reference Appleby2000; Dalacoura Reference Dalacoura2000, 883; Deitch Reference Deitch2020, 3; De Juan Reference De Juan2015, 766; Hoffman Reference Hoffman1995; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2009, 168; Klocek and Hassner Reference Klocek, Hassner and Thompson2019, 6; McTernan Reference McTernan2003), conflict resolution and peacemaking, (Appleby Reference Appleby2000; Luttwak Reference Luttwak, Johnston and Sampson1994, 17, 18), political protest and mobilization (Akbaba Reference Akbaba and Thompson2019; Fawcett Reference Fawcett2000, 8; Hoffman and Jamal Reference Hoffman and Jamal2014, 595), discrimination, (Fox Reference Fox2020; Peretz and Fox Reference Peretz and Fox2021), populism (Cremer Reference Cremer2023, 172; Peker and Laxer Reference Peker and Laxer2021; Sandal Reference Sandal2021b), and fascism (Eatwell Reference Eatwell2003), among others.

Others discuss the ability of religion to legitimate political agendas on a more general level (Berger Reference Berger1996/1997, 11). Sociologists argue that religion can legitimate social order, social control, and the purposes and procedures of society in general (e.g., Wilson Reference Wilson1982). Many also argue that religious legitimacy can be important in politics even in countries that maintain separation of religion and state (Billings and Scott Reference Billings and Scott1994; Demerath Reference Demerath2001; Mantilla Reference Mantilla2016, 233) and that democracy cannot be legitimate without a higher moral authority (Juergensmeyer Reference Juergensmeyer2008, 230).

We stress that while these studies claim religion can influence legitimacy, they rarely claim that it does so in all cases. Some also explicitly discuss how religion can delegitimize a government, leaders, policy, other political actors, or phenomena (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012, 432; Juergensmeyer Reference Juergensmeyer1993; Kettell and Djupe Reference Kettell and Djupe2020, 2; Philpott Reference Philpott2007). Demerath (Reference Demerath2001) argues that religion’s role can range from an empty symbol to something that is essential to the state’s legitimacy and can be a detriment to the legitimacy of states that rely on explicitly secular anti-religious theories of legitimacy. Johnston and Figa (Reference Johnston and Figa1988) argue that churches are well positioned to challenge governments because regimes are less likely to repress religious organizations than secular ones, their privileged access to the media, their inherent legitimacy in the eyes of the public, and their organizational capacity.

Nevertheless, within this body of theory, few claim that when religion undermines the legitimacy of a state or government, it is a result of that state supporting religion. Rather, this occurs when a religious actor seeks to undermine the legitimacy of the government. Sandal (Reference Sandal2021a) theorizes strategies to accomplish this delegitimization as a form of outbidding which can take several forms. These include challenging the fundamental legitimacy of the government, accusing it of treason or cooperation with the “other,” accusing it of being secular, questioning the morals of the government, and questioning the government’s actions. Thus, this body of theory assumes religion is capable of influencing legitimacy and the only questions are the direction in which this influence is applied and by whom.

This relationship between religion and legitimacy is theorized in different manners. For example, Grzymala-Busse (Reference Grzymala-Busse2015) theorizes that the source of religious legitimacy is its moral authority. Others like Joustra (Reference Joustra2019) and Philpott (Reference Philpott2007, 520) focus on “political theology” a concept that argues that religions have a defined ideology on the nature and limits of legitimate political authority. This relationship between religion and ideas of legitimate political authority can evolve over time and is deeply connected to and influenced by the political interplay between religion and politics.

That being said, when these studies address the relationship between government support for religion and legitimacy, the assumption is generally that this support is likely intended to lead to increased legitimacy. Some make this argument in general (e.g., Driessen Reference Driessen2014b, 367; Henne, Saiya, and Hand Reference Henne, Saiya and Hand2020, 1948; Vaubel Reference Vaubel2019). Others make it more specifically. For example, Schleutker (Reference Schleutker2021, 228) argues that “one of the benefits of coopting the religious groups is that these groups can support the regime in its legitimation strategies and thus give credibility for the regime.” More importantly, there is a growing rational choice literature which argues that politicians choose to support a state religion precisely because they believe that it makes ruling easier and more efficient for a number of reasons including religion’s ability to increase a government’s legitimacy.

RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY, RELIGION, AND LEGITIMACY

Rational choice theorists among politics and religion scholars, with few exceptions, argue that state governments and politicians choose to support religion because they expect this to increase the government’s legitimacy, but this discussion focuses mostly on religious freedom rather than legitimacy. The argument’s originator, Gill (Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008), asks why governments support religious freedom versus a religious monopoly, which inevitably requires repressing religious minorities.Footnote 1 Gill (Reference Gill2008, 40–58) argues that politicians decide based on the costs and benefits of each option and that the potential benefits of supporting a religion include increased legitimacy which reduces the costs of ruling by reducing opposition and increasing compliance with laws. Additional benefits include increased morality which reduces law enforcement costs by reducing crime.

Thus, government support for a religion is motivated, at least in part, by that government’s desire to gain legitimacy. If they choose not to support religion, it is because the opportunity costs outweigh any perceived benefits, including cases where politicians believe the gained legitimacy will be minimal. However, if politicians support a religion, it is because they believe that these benefits, including increased legitimacy, are sufficiently substantial to be worth the costs (Gill, Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008, 48–51).

There is a growing discussion and critique of this argument, but almost none of it questions the argument that state support for religion is intended, at least in part, to increase legitimacy. In fact, most critics explicitly acknowledge this motivation when they address this argument. This is because this literature largely focuses not on religious legitimacy but on the costs and benefits of supporting a state religion versus supporting religious freedom. Rather than questioning the legitimacy motivation, critics tend to argue that there are additional costs and benefits that Gill (Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008) did not consider. These potential costs and benefits include the material costs of repression, the potential of religious institutions to be a basis for opposition (Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2015), and the social welfare benefits of religious-based charity (Koesel Reference Koesel2014). Several empirical studies demonstrate that state support for religion and a lack of religious freedom can increase terrorism and conflict (Grim and Finke Reference Grim and Finke2011; Henne, Saiya, and Hand Reference Henne, Saiya and Hand2020; Saiya Reference Saiya2019a; Saiya and Manchanda Reference Saiya and Manchanda2020). Finke (Reference Finke2013, 300) argues that even atheist governments can gain legitimacy from supporting religion. Fox, Eisenstein, and Breslawski (Reference Fox, Eisenstein and Breslawski2022) find that state support for religion can increase social trust. Some argue that other factors mediate this relationship including the state’s bureaucratic structure (Mayrl Reference Mayrl2015), the population’s religiosity (Buckley and Mantilla Reference Buckley and Mantilla2013, 345), and the regime (Schleutker Reference Schleutker2019).

An additional critique is that Gill (Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008) inappropriately downplays the role of ideology in the decision to support a state religion (Kuru Reference Kuru2009, 21, 22; Philpott Reference Philpott2009, 194). Finally, Gill (Reference Gill1998), in earlier work, argues that in Latin America the Catholic Church has separated itself from some regimes in cases where the regimes were so illegitimate that remaining associated with the state was undermining the church’s legitimacy.

This literature is important for two reasons. First, it provides a discussion of what motivates a government’s state religion policy. Second, and more central to our purposes, it shows that this literature is largely in agreement that if a government supports a religion or religions, the desire for increased legitimacy is among its motivations and is, perhaps, its primary motivation. In fact, few, if any, references to Gill (Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008) question this motivation. He is often cited regarding the general utility of religious legitimacy (e.g., Elischer Reference Elischer2019; Mantilla Reference Mantilla2019) or to support the argument that state support for religion increases legitimacy and the ease of ruling (e.g., Arikan and Bloom Reference Arikan, Bloom and Thompson2019; Dromi and Stabler Reference Dromi and Stabler2019; Dzutsati, Siroky, and Dzutsev Reference Dzutsati, Siroky and Dzutsev2016; Ringvee Reference Ringvee2015). The few studies which unfavorably reference Gill’s (Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008) arguments tend to question his assumption of rationality and do not address the legitimacy issue (e.g., Larson Reference Larson2015; Miller Reference Miller2012). While there have been empirical studies testing Gill’s (Reference Gill2005; Reference Gill2008) arguments linking state support for religion to decreased religious freedom (Finke and Martin Reference Finke and Martin2014; Fox Reference Fox2020; Grim and Finke Reference Grim and Finke2011; Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2015), we are aware of none which directly test the impact of government support for religion on that government’s legitimacy.

It is important to note that nearly all references to the support–legitimacy link in the rational choice and general literatures theorize the link as one where support for religion influences the government’s legitimacy. However, there is no shortage of theories that religious beliefs and ideology (as opposed to legitimacy) may motivate a government to support a state religion. As noted, Kuru (Reference Kuru2009, 21, 22) and Philpott (Reference Philpott2009, 194) make this argument as do (Fox Reference Fox2015, 42, 43; Reference Fox2018, 49–57), Grim and Finke (Reference Grim and Finke2011), Henne (Reference Henne2016), Schleutker (Reference Schleutker2021), Stark (Reference Stark2003), and Stark and Finke (Reference Stark and Finke2000), among many others. That is, while this could be framed as arguing that states in which religion is legitimate tend to be more likely to support religion, those who address religion’s influence on state support for religion focus on facets of religion other than legitimacy, particularly religious ideology, to theorize about this relationship.

COUNTERARGUMENTS TO THE UTILITY OF SUPPORTING RELIGION

There is a growing literature which implies that, whatever politicians may think, support for religion may reduce legitimacy. To be clear, this literature rarely directly addresses the support–legitimacy relationship or even a government’s legitimacy at all. Nevertheless, we argue that if examined with the question of this relationship in mind, it provides a rationale for arguing that government support for religion may undermine that government’s legitimacy as well as a mechanism through which this delegitimation can occur. This rationale consists of three interrelated factors: the rise of secularism and political secularism, the supply-side theory of religion, and the desire for religious independence from the state.

Secularism and Political Secularism

Social scientists have long discussed the potential impact of secularism on politics. For much of the twentieth century, the dominant argument was secularization theory, which predicted that religion would decline and perhaps disappear.Footnote 2 For example, Chaves (Reference Chaves1994, 756) describes secularization as “declining religious authority… [which] refer[s] to the declining influence of social structures whose legitimation rests on reference to the supernatural.” Thus, this argument has religious legitimacy declining and perhaps disappearing but, to the extent that it still exists as an influence, the support–legitimacy relationship should hold.

As it became clear that religion was not disappearing, researchers began to discuss secularism as an ideology that competes with religion for influence (Calhoun, Juergensmeyer, and VanAntwerpen Reference Calhoun, Juergensmeyer and VanAntwerpen2012). Taylor (Reference Taylor2007), focusing on religiosity, argues that the existence of an organizing ideology for the nonreligious is a game-changing factor. Fox (Reference Fox2015) focuses on the political competition between ideologically secular and religious actors. Specifically, secular actors seek to remove religion from government, policy, and perhaps the public sphere, as well as restrict some religious practices while religious actors seek the opposite.

The specifics of the secular agenda depend on the variation of the secular ideology in question. Secularism is a family of ideologies that can be as diverse as religion. For example, Kuru (Reference Kuru2009) and Toft, Philpott, and Shah (Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011) differentiate between negative and positive secularism. The former includes anti-religious versions of secularism. Philpott (Reference Philpott2019, 77) calls one form of anti-religious secularism “repressive” secularism which “emanates from a western strand of thinking, vivified in the French Revolution, which holds that religion must be managed, controlled, and contained in order to make way for the modern state.” Positive secularism, in contrast, considers religion a positive influence but also considers the separation of religion and state to be healthier for both religion and government.

That this agenda has had considerable success in both its positive and negative manifestations (Fox Reference Fox2015; Kortmann Reference Kortmann2019) implies that there is a significant constituency that believes religion should not influence the political agenda. It is reasonable to argue that this constituency would consider state support for religion illegitimate.

This constituency can include people who are personally religious. This is because many manifestations of political secularism, particularly positive secularism, are about removing religion from politics and, in some cases, the public sphere and not necessarily about opposing religion as a private personal matter. However, some of the more extreme versions of negative secularism do propose restricting religion even in the private sphere. This is implied in definitions of political secularism such as “defenses of the secular functions of government, the constitutional secularity of government, and the promotion of governments showing legal neutrality toward, and relative independence from, religions” (Zuckerman and Shook Reference Zuckerman and Shook2017, 11) or “an ideology or set of beliefs advocating that religion ought to be separate from some or all aspects if politics or public life (or both)” (Fox Reference Fox2015, 2). For instance, in a survey of Christian Romanians, over half indicated that church intervention in politics was undesirable, even though most consider the church to be legitimate. Indeed, amongst Romanian citizens, a strong expectation exists that religious entities remain confined to sacred, rather than political, spheres of influence (Flora, Szilagyi, and Roudometof Reference Flora, Szilagyi and Roudometof2005).

Research shows this attitude is also common in non-Western countries. For instance, a survey of 34 African countries found that a majority of respondents in all but three favor civil over religious laws as a foundation for the government (Howard Reference Howard2020).Footnote 3 This is despite the fact that 95% of Africans identify with a religion and perceive religious leaders to be more trustworthy and less corrupt than any other type of leader (Howard Reference Howard2020). As we discuss in more detail below, there are multiple reasons a religious person might prefer political secularism as the basis for a government’s religion policy.

The Supply Side Theory of Religion

The supply-side theory of religion provides one such rationale and is the second factor that we posit may motivate a reduction in government legitimacy when that government supports a religion. This theory uses economic language and rationale to discuss the relationship between a religious monopoly and individual religiosity in a country. It conceives of religions as producers or firms that market religion to consumers. In an unregulated market—one where the government does not support religion—multiple religious firms compete for consumers. As part of this process, constantly evolving religious firms fill empty niches within the religious economy. As is the case with any competition setting, this will result in better religious products and more people will consume religion. As religious firms require congregants to fund their activities, they actively seek to remain attractive to their consumers. In contrast, in a monopoly situation—where the state supports a religion—religion’s institutions and workers are beholden to the government rather than to their congregants. This decreased importance of pleasing consumers results in a lower quality product which reduces the use of this inferior product. For example, in a monopoly situation religious workers are essentially government employees, and pleasing the government rather than ministering to congregants increases job security, promotions, and salary increases for clergy. That is, “under monopoly conditions, religious firms have an incentive to take advantage of their position through rent-seeking behaviors and poor performance. Because clerics in monopoly firms are provided secure incomes and face no extra-firm competition, they have weak incentives to meet the needs of their constituents” (Pfaff and Corcoran Reference Pfaff and Corcoran2012, 759). Also, only a single religious product is available in a monopoly situation. If a religious consumer is not interested in this monopolist religion but might have been interested in another unavailable religious product, this potential religious consumer will not partake in religion (Barro and McCleary Reference Barro and McCleary2003; Finke Reference Finke1990; Reference Finke2013; Finke and Iannaccone Reference Finke and Iannaccone1993; Froese Reference Froese2004; Iannaccone Reference Iannaccone1995; Stark and Finke Reference Stark and Finke2000; Stark and Iannaccone Reference Stark and Iannaccone1994).Footnote 4

How is this relevant? This theory argues that religion thrives when it is unfettered from state support. If religious individuals believe this to be true, they will likely prefer that a state not support religion and could consider such support illegitimate. This is inherent in the concept of political theology which Joustra (Reference Joustra2019, 2) defines as “the understandings and practices that political actors have about the meaning of and relationship between the religious and the secular, and what constitutes legitimate political authority.” Philpott (Reference Philpott2007, 505), when discussing political theology, similarly argues that “religious bodies contain shared ideas about legitimate political authority.” This theory is also related to the issue of political secularism in that it specifically predicts that over the long term, state support for religion decreases religiosity (Saiya and Manchanda Reference Saiya and Manchanda2022).

The Desire for Religious Independence from the State

A third but related reason is the influence of state control over religion on the perceived authenticity of that religion. Specifically, we argue that religious individuals might support political secularism if they believe that their religion is purer and more authentic when separated from the government. This is because when a government supports religion, this inevitably leads to government control of that religion. Government support for a religion makes that religion’s institutions to some degree dependent on that government and, accordingly, more vulnerable to government efforts to control them, even if control was not the original motivation for that support (Fox Reference Fox2015). That is, once a religious institution is dependent upon government support for its well-being and perhaps survival, the threat of withdrawal of this support is always a potential lever of control. More importantly, one of the most effective tactics available to governments that seek to control a religion is to support it (Cosgel and Miceli Reference Cosgel and Miceli2009, 403; Demerath Reference Demerath2001, 204; Grim and Finke Reference Grim and Finke2011, 207).

Kuhle (Reference Kuhle2011, 211) argues that “a close relationship between state and church entails the risk of the state interfering with what some would regard as ‘internal’ religious questions.” She documents that the five Nordic states successfully pressured their national churches to adopt new doctrines on issues such as the ordination of women and gay marriage. In Sweden, there is increasing frustration regarding the involvement of politicians in theological affairs. In fact, archbishops openly criticize the way in which the Church of Sweden has been pressured by the government to adjust their values to reflect a secular worldview (Forster Reference Forster2021).

The ability to control religion is also likely among the reasons many authoritarian states create and support national religious networks and institutions. Though only some such states declare them official religions, in nearly all cases they exert considerable control over religious institutions and networks (Fox Reference Fox2015; Philpott Reference Philpott2019; Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2015). Also, control over religious institutions, especially when it includes influence over who is appointed to lead those institutions, constitutes control over those who are the caretakers of how theology and doctrine are interpreted and taught.

This dynamic is even relevant in secular states. Henne, Saiya, and Hand (Reference Henne, Saiya and Hand2020, 1948) argue that “state favoritism of religion can also exist in ostensibly secular states where political elites believe that the best way to keep religion’s public power in check is to support a moderate strain of the predominant faith tradition, making it dependent on or beholden to the government.” Kuru (Reference Kuru2009, 167) and Philpott (Reference Philpott2019, 77–83) similarly argue that negative secular states often support religion in order to create a privatized version that will have little public influence. Given this, religious individuals who prefer that their religion be free of government influence, particularly on matters of doctrine and theology, may consider state support for religion illegitimate.

This preference for religion to be a private matter of individual choice is also noted in the secularization literature. While this focus on individualism was seen mostly as a reason organized religion would disappear (Bruce Reference Bruce and Haynes2009, 147), it also supports the contention that individuals want to decide matters of religion for themselves without government interference. Crouch (Reference Crouch2000), for example, argues that increased individualism in the West has led to religion becoming more of an individual choice and that in this context “people become very wary about how much heteronomy they are accepting” (Crouch Reference Crouch2000, 95). There is some evidence that in Christian-majority countries individuals are seeking forms of Christianity tailored to their individual preferences (Muller Reference Muller2011; Pollack Reference Pollack2008). This blends well with the supply-side argument that people prefer a free religious market that allows them to seek the religious product they find most attractive. It is also clear that many religious activists consider laws which in some way restrict the ability to practice their religion a violation of their individual freedoms (Jelen Reference Jelen2006, 335–6). Consequently, it is reasonable to argue that government control of religion would be similarly distasteful to at least some of these activists and those who prefer a religion suited to their individual preferences.

Grzymala-Busse (Reference Grzymala-Busse2015) argues that it is also in the interests of religious institutions to remain separate from politics. This is because becoming involved in politics undermines the moral authority of a church by making it seem no better than other politicians. In contrast, churches that remain generally supportive of a state in a nationalist and neutral manner tend to have more influence over government policy through backroom politics.

All three of these various factors influencing preferences for government religion policy are deeply connected to legitimacy. This is inherent in the concept of political theology which, as noted, involves what religious individuals and institutions consider to be the legitimate relationship between religion and politics (Joustra Reference Joustra2019, 2; Philpott Reference Philpott2007, 505). It is important to note that “political theology is shaped not purely by doctrine but also by the lessons of history” (Philpott Reference Philpott2019, 75). This is particularly relevant to fears that state control of religion will make a religion unauthentic and impede its ability to thrive.

In light of the two opposing expectations suggested by the literature regarding the relationship between state support for religion and state legitimacy, the relationship between state support for religion and government legitimacy could be positive or negative. We rely on our empirical analysis to draw conclusions about the direction of the relationship.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To investigate the effect of state support for religion on legitimacy, we combine data from the RAS and the WVS datasets. Our sample is made up of all Christian-majority countries that were surveyed for the WVS between 1990 and 2014.Footnote 5 We focus on Christian-majority states because we expect the relationship between state support for religion and government legitimacy to be different across different religions.Footnote 6 For example, Fox (Reference Fox2020) found that while there were commonalities across different religious traditions, many aspects of state support for religion were different across religious traditions. We match our data by country and year, meaning that for every country and year there is a WVS survey, the observations from that survey are matched to the RAS data from that same country year. Our approach results in a sample that includes 54 countries and 126 country years.Footnote 7

We use the WVS data to measure government legitimacy. The question of how to measure legitimacy is much discussed, and scholars have highlighted multiple dimensions of legitimacy, identifying both attitudes/opinions as well as behavior as components of legitimacy (Von Haldenwang Reference Von Haldenwang2016). We focus here on attitudes/opinions, and specifically, confidence in leaders. To capture government legitimacy, we use two different dependent variables. The first is an ordinal measure that asks individuals how much confidence they have in the government, to which they can answer, “None at all,” “Not very much,” “Quite a lot,” or “A great deal.”Footnote 8 The second dependent variable is equivalent to the first, but asks individuals how much confidence they have in parliament.Footnote 9

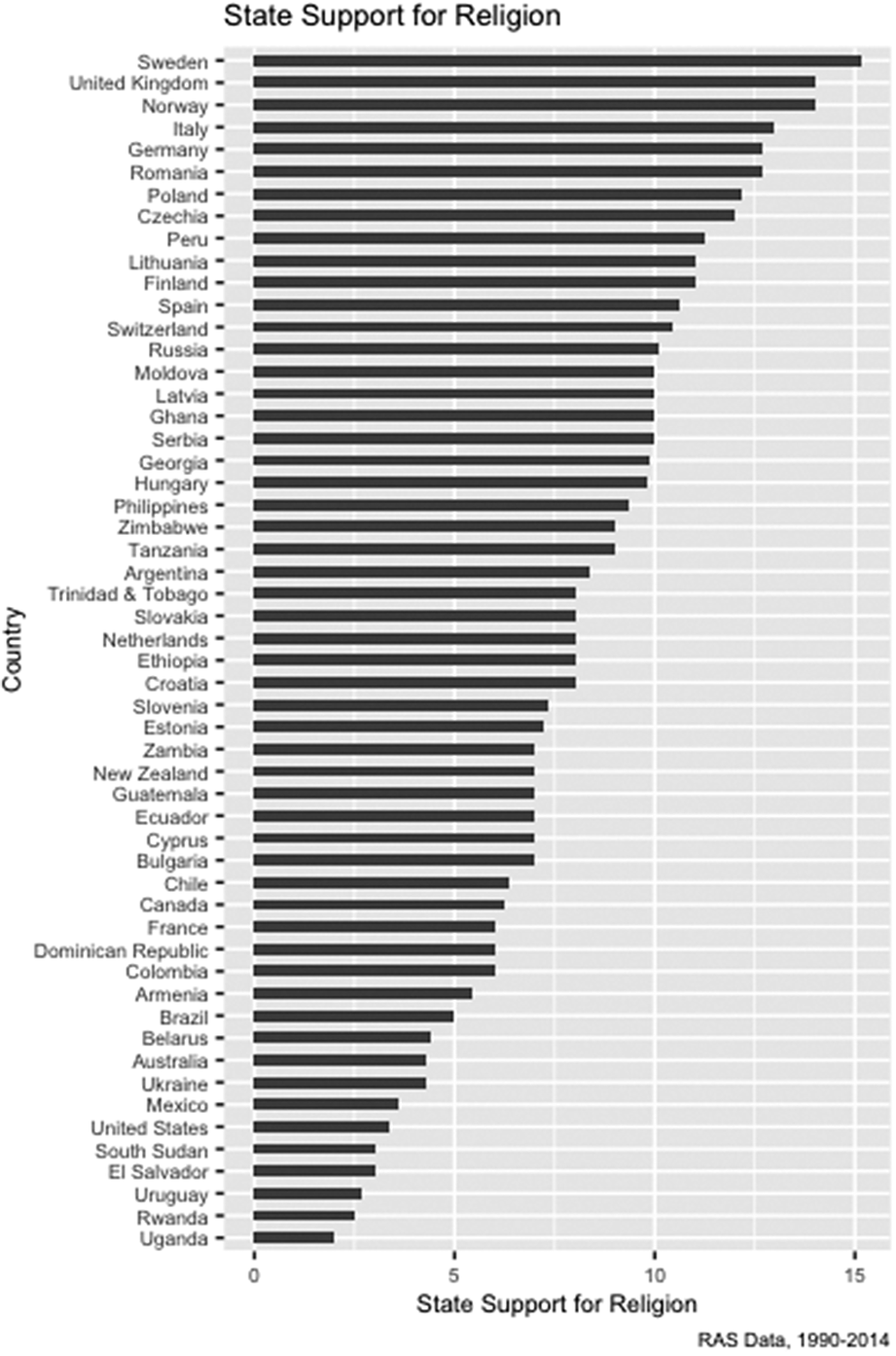

To capture state support for religion, we use the RAS data to construct a continuous measure that includes 52 types of support, including different types of laws on relationships, sex, and reproduction,Footnote 10 institutions that enforce religion, various government funding for religion, and forms of entanglementFootnote 11 of government and religious institutions.Footnote 12 While the variable could theoretically take any value between zero and 52, the highest in our sample is 16, with a mean of eight. Figure 1 shows the mean level of state support for religion for each country in our sample.

Figure 1. Mean State Support for Religion by Country

In modeling the relationship between state support for religion and citizens’ perceptions of state legitimacy, we include a number of additional variables to control for alternative explanations, both at the individual and country level. At the individual level, we control whether an individual is a member of a minority religion, which may impact how state support for religion affects their individual views of the state.Footnote 13 We control for an individual’s level of religiosity, which may be a product of state policies toward religion and has been found to influence trust.Footnote 14 We include a measure of subjective well-being and level of education, which may be connected both to state behavior and individuals’ confidence in the government.Footnote 15 At the country level, we control for state discrimination against minority religious groups, which may be associated with higher levels of state support for religion and also negatively impact government legitimacy.Footnote 16 We also control for the country’s Gini coefficient,Footnote 17 logged population, logged GDP per capita, the level of democracy,Footnote 18 and the country’s stability,Footnote 19 all of which may influence and be influenced by a country’s religious policies as well as shape individual perceptions of government legitimacy. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of each variable. Table A11 in the Supplementary Material summarizes the variables’ labels, data sources, and years of availability.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

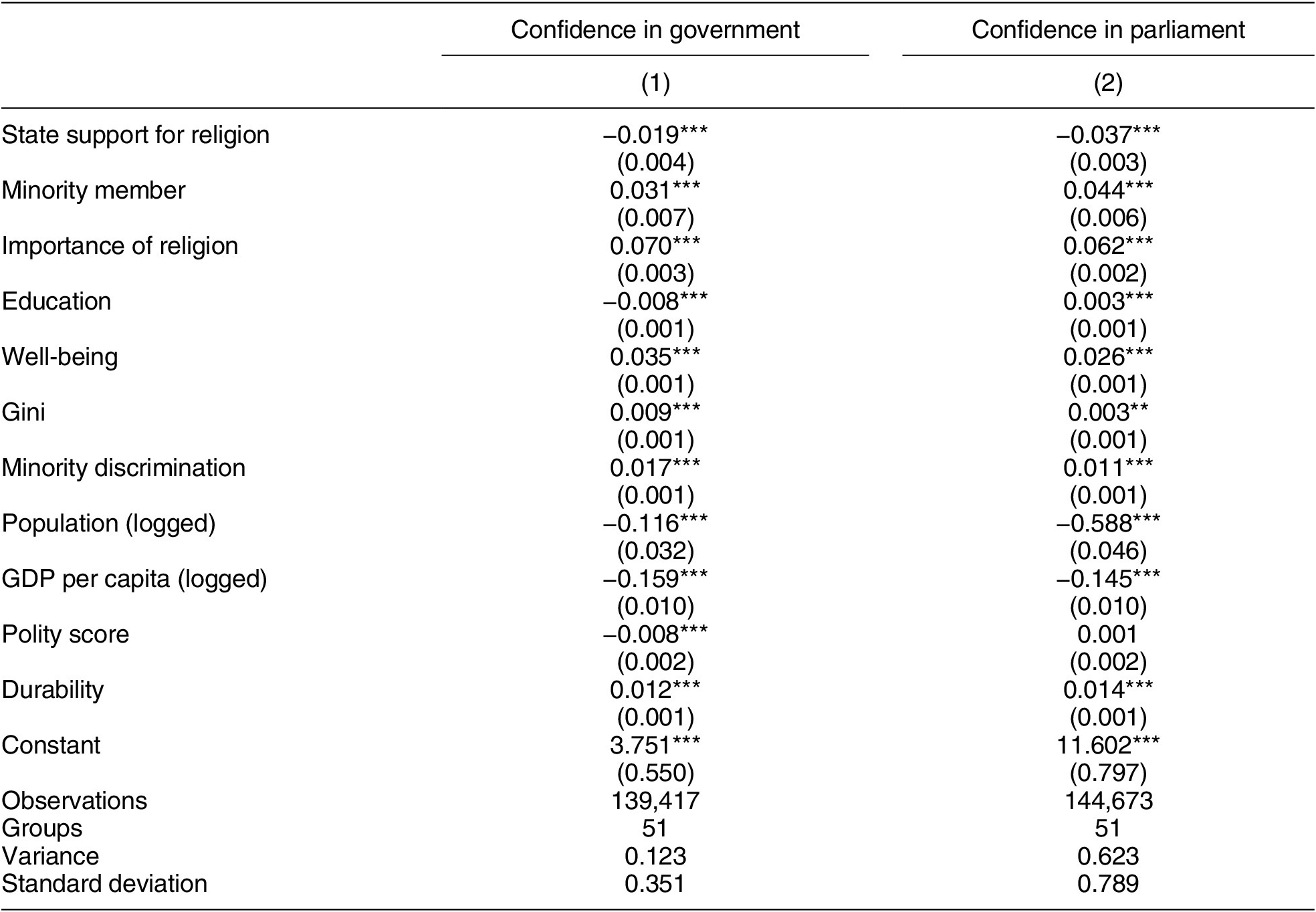

We use a multilevel model approach in order to estimate the cross-sectional associations between state support for religion and perceptions of legitimacy while taking into account the clustering of observations within countries. We use random intercept models, which are highly advantageous for analyses of complex data structures in which observations are grouped. In our case, individuals’ perceptions of legitimacy likely depend on the country in which they live. Due to the fact that the model’s key independent variable is a characteristic of the country, multilevel models are the appropriate way to model the relationship between state support of religion and legitimacy. We use generalized linear mixed effect models that predict individuals’ levels of perceived government legitimacy, allowing intercepts to vary between each country. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The Relationship between State Support for Religion and Confidence in Government and Parliament, 1990–2014

Note: While some of the coefficients on the control variables appear counterintuitive (for instance, a negative relationship between GDP per capita and confidence in government), we are hesitant to expound on their meaning, as control variables generally have no structural interpretation and do not correspond to any causal effect (Hünermund and Louw Reference Hünermund and Louw2020). *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Both models 1 and 2 provide evidence of a negative relationship between state support for religion and government legitimacy. State support for religion yields a negative and statistically significant coefficient, indicating that as state support for religion increases, confidence in both the government and parliament decreases. The public’s reactions to several recent cases in which the government discussed or carried out changes in state support for religion are illustrative of the results of our quantitative analysis. In Mexico, a 2019 initiative by a senator from the left that proposed an end to the separation of church and state was met with criticism from across the political and religious spectrum (Orsi Reference Orsi2019). The proposal included provisions that would encourage cooperation between church and state on social and cultural development, open an avenue to object laws on religious grounds, and allow religious authorities to do spiritual work in government facilities like hospitals and military bases (Orsi Reference Orsi2019). In this case, the discussion of increasing state support for religion led to pushback from religious and nonreligious Mexicans alike. To illustrate the relationship in the opposite temporal direction, in 2018, Ireland ended the country’s ban on blasphemy, following a landslide referendum on the topic (Graham-Harrison Reference Graham-Harrison2018). In this case, decreasing state support for religion was widely popular amongst the Irish public. Notably, both countries’ populations are relatively religious, with only 8% of Mexicans and 10% of Irish identifying as nonreligious (Department of State 2022).

In order to understand whether these results are substantively significant, we calculate the predicted confidence in government and parliament as state support for religion increases.Footnote 20 Regarding confidence in government, moving from one standard deviation below the mean of state support for religion (4) to one standard deviation above the mean (11) results in a 11% decrease in confidence in government. Regarding confidence in parliament, moving from one standard deviation below the mean of state support for religion to one standard deviation above the mean results in a 29% decrease in confidence. Figure 2 illustrates these results.

Figure 2. Predicted Confidence in Government and Parliament by State Support for Religion

Given the fact that our index of government support for religion includes a wide array of policies and laws, it may obscure important variations. We thus break the index into four categories that correspond with distinct aspects of governments’ support for religion. Figure 3 shows the relationship between each category of religious support and confidence in government and parliament. All the same control variables are used in the models. Full regression tables can be found in Tables A1 and A2 in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 3. The Relationship between State Support for Religion and Confidence in Government and Parliament, by Category

The first category is institutions or laws that enforce religious behavior, which includes blasphemy laws or censorship of press on grounds of being anti-religious. While a number of European countries have abolished blasphemy laws in recent years, the laws are still common across Europe. For instance, Greece criminally sanctions “showing disrespect to the divine” while in Finland “blaspheming against God” is a crime (IPI 2017). The relationship between enforcement and government legitimacy does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance in the case of the government but has a statistically significant negative relationship with confidence in the parliament.

The second category is funding for religion, which includes policies such as governments funding religious schools or providing grants to religious organizations. Countries have a range of policies regarding the financial support of religious institutions. For instance, in the United States, the constitution prohibits the direct funding of religious institutions by taxpayers. In contrast, a number of countries in Europe, like Austria, Denmark, and Germany, provide funding for churches with taxes paid by the public (Masci Reference Masci2019).Footnote 21 In Russia, the Orthodox Church has been the primary beneficiary of presidential grants in recent years (Brechenmacher Reference Brechenmacher2017). Funding has a negative and statistically significant relationship with confidence in government and parliament.

The third category is laws on relationships, sex, and reproduction, which, as noted, includes several categories but is in practice mostly driven by restrictions on abortion and homosexuals. In contrast to the other categories, this category has a positive and statistically significant relationship with government legitimacy.

The fourth category is the entanglement of government and religious institutions, which includes policies such as government officials needing to meet certain religious requirements or certain religious officials becoming government officials by virtue of their religious position. Entanglement has a negative and statistically significant relationship with confidence in government and parliament.

These results are particularly interesting because government funding for religion and entanglement between government and religious institutions are important methods of government control for religion (Fox Reference Fox2015). However, enforcement of religious laws such as abortion, do not imply government control of religion but, rather, government enforcement of religious norms.

We run a number of additional analyses to further probe the relationship between state support for religion and government legitimacy. First, we examine whether the relationship is different between members of the majority and minority religions. Second, we investigate whether the negative relationship of state support for religion and government legitimacy differs between those who are more religious and those who are less so. Third, we run a number of models with different specifications, additional controls, and alternative measures.

A natural question is whether members of majority and minority religions have different perceptions of government legitimacy based on the level of state support of religion. Table 3 shows regressions that test the relationship between state support for religion and government legitimacy, separating members of the majority and minority religions. Models 3 and 4 include members of the majority religion, while models 5 and 6 include members of minority religions.

Table 3. The Relationship between State Support for Religion and Confidence in Government and Parliament, by Majority and Minority Religious Groups, 1990–2014

Note: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The relationship between state support for religion and government legitimacy is robust across both members of the majority and minority religions. In all models, higher levels of state support for religion are associated with lower confidence in the government and parliament. While the finding may seem counterintuitive in the case of members of the majority religion, it is unsurprising with respect to minority religions. State support for religion usually, though certainly not always, constitutes preference for the majority religion, especially at higher levels of support (Fox Reference Fox2015). This can make minorities feel like second-class citizens which would likely influence their feelings toward the government.

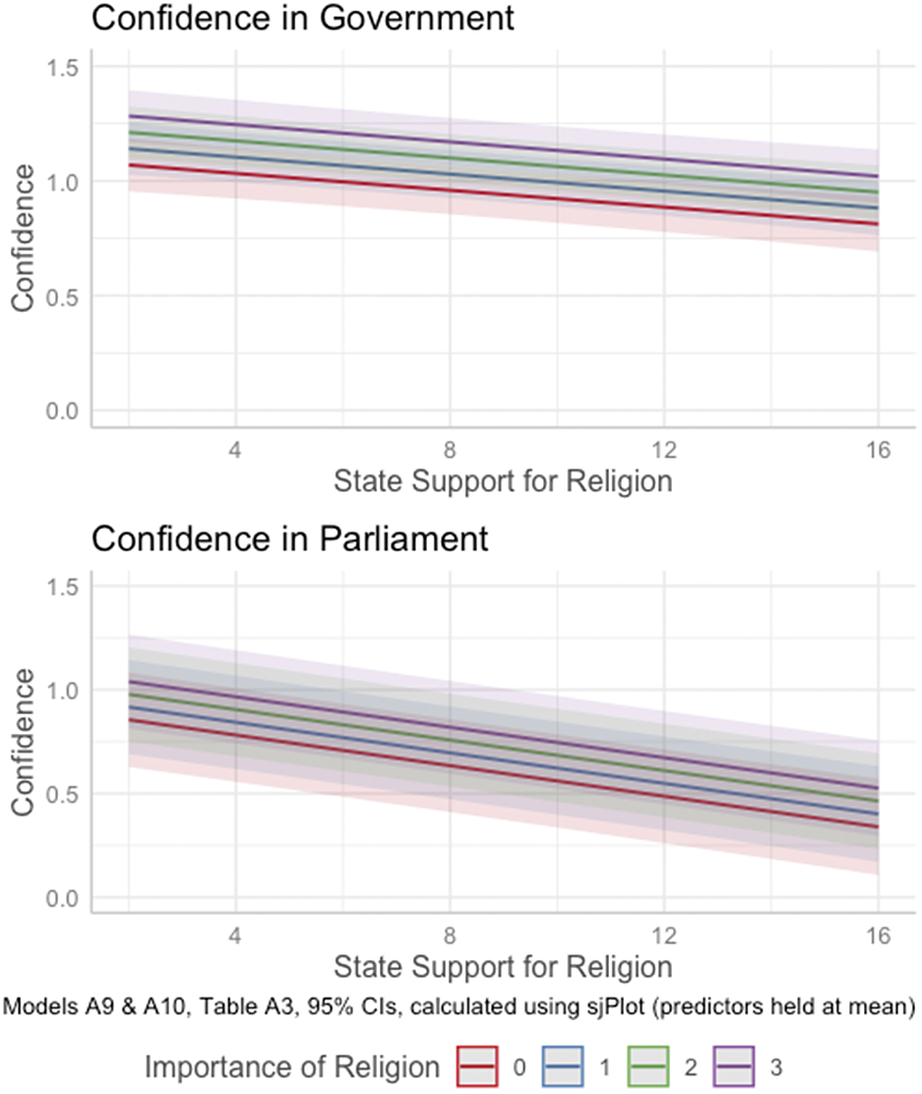

We next investigate whether the relationship between state support for religion and confidence in government differs depending upon one’s level of religiosity. To do so, instead of controlling for religiosity, we interact it with our main variable of interest. The coefficient representing the interaction between state support for religion and religiosity is not statistically significant, indicating that the negative relationship between state support for religion and confidence in government extends to even those who value religion the most. Figure 4 illustrates the consistency of the relationship between state support for religion and confidence in government across all levels of reported importance of religion. Table A3 in the Supplementary Material shows the full results. At all levels of religion, state support for religion has a negative effect on confidence in government and parliament.

Figure 4. Predicted Confidence in Government and Parliament by State Support for Religion, by Religiosity

The dynamics of religion and state in Poland are illustrative of these findings. Officially, religion and state are independent and autonomous from one another. However, in recent years, the two institutions have grown increasingly entangled, which has caused broad backlash, even from religious Poles. In fact, many have undertaken apostasy—a formal disaffiliation from the church in response to the politicization of religion in their country. When the government ruled to make aborting fetuses with abnormalities illegal in 2020, Polish Google searches for apostasy reached their highest volume in over fifteen years (Pawlak and Ptak Reference Pawlak and Ptak2021).

We run models using country and wave-fixed effects, as an alternative to the random effects approach used in our main analysis, which can be found in Tables A4 and A5 in the Supplementary Material. While our main models account for differences across countries in government legitimacy, they do not account for differences across time. Including wave-fixed effects allows us to address the phenomenon of change over time in individuals’ perceptions of what is a legitimate relationship between church and state. We run a number of models with additional controls. First, we add additional demographic variables—sex and age (Table A6 in the Supplementary Material).Footnote 22 Next, we add a measure of the level of societal discrimination that religious minorities face in the country (Table A7 in the Supplementary Material). Greater state support for religion may in turn legitimize discrimination by members of the majority religion against members of minority religions, which may affect confidence in the government.Footnote 23 We also run a model that adopts an alternative measure for religiosity—the frequency that individuals attend religious services (Table A8 in the Supplementary Material).Footnote 24 Finally, we add regional dummies, to account for any differences in the relationship between state support for religion and confidence in government between regions (Table A9 in the Supplementary Material).Footnote 25 The relationship between state support for religion and confidence in government is robust to controlling for these different variables.

CONCLUSION

In the long run, legitimacy is less costly and more efficient than coercion as a means of control and as a result, both democratic and nondemocratic governments desire legitimacy (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; Hurd Reference Hurd1999). For this reason, understanding the relationship between state support for religion and legitimacy is important both to the scholarly community and the politicians that set government religion policy.

In this article, we examine the relationship between a government’s support for religion and the government’s legitimacy. We find that if governments in Christian-majority countries expect to gain legitimacy in return for supporting religion, they are likely to be disappointed. We find robust support for the finding that state support for religion is associated with a decrease in individuals’ confidence in government and parliament. A shift in state support for religion from one standard deviation below the mean to one standard deviation above the mean is associated with a 10% decrease in individuals’ confidence in government. Because state support for religion involves a number of diverse policies and practices, we examine which types of state support for religion are driving its negative relationship with confidence in government and find that government funding of religion and entanglement with religion are the two primary categories responsible for the negative relationship between state support for religion and confidence in government. In contrast, state restrictions on abortion and homosexuals, overall, are associated with higher levels of confidence in government.

These results have important implications for our understanding of the sources of a government’s legitimacy beyond demonstrating flaws in the assumption that state support for religion will increase a government’s legitimacy. Our findings imply that there is a diverse constituency that objects to certain types of state support for religion, including both secular and religious individuals. The latter likely believe that religion is more authentic and better able to thrive in an environment where religion and state are separate.

These interactions can be complex. For instance, in Poland, following the recent government ruling to enforce a total ban on all abortions, polls found that the popularity of the ruling party dropped and that the majority of Poles supported the resulting protests against the government (Tilles Reference Tilles2020). Relatedly, as politicians in Zambia and Uganda seek to mobilize voters in their favor with laws criminalizing same-sex relationships, research has shown that these elite strategies are not always in touch with their citizens’ attitudes (Awondo, Geschiere, and Reid Reference Awondo, Geschiere and Reid2012).

In both cases, politicians are playing to a religious base by enforcing religious precepts popular to that base and are likely successful at increasing their support and legitimacy among that base. However, in both cases there exists significant opposition to these policies which some portray as a competition between religious and progressive forces (Palacek and Tazlar Reference Palacek and Tazlar2021) or as secular-religious competition (Fox Reference Fox2015). Yet this interaction is more complex because our results suggest that even among religious individuals, many support the separation of religion and state.

This suggests that a religious constituency exists that opposes government interference in religion. Yet at least some of this constituency supports government efforts to enforce their religious values on the wider population. Clearly, this constituency is a subset of all religious people. Nevertheless, our evidence suggests this constituency is sufficiently influential that it can contribute to a decline in support for governments that are overly involved in religion in a manner that might control or influence the religion itself but also contribute to an increase in support for governments that are willing to enforce religion-based policies popular with portions of that constituency. Thus, for these individuals, support for religion is illegitimate when this type of government policy influences religion in a manner that undermines religions’ authenticity and independence but legitimate when it is their religious beliefs which influence government policy.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001320.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NM0XLV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank David Buckley, Daniel Philpott, Roger Finke, Ariel Zellman, and Peter Henne as well as APSR’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on this study.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 23/14), The German-Israel Foundation (Grant 1291-119.4/2015) and the John Templeton Foundation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.