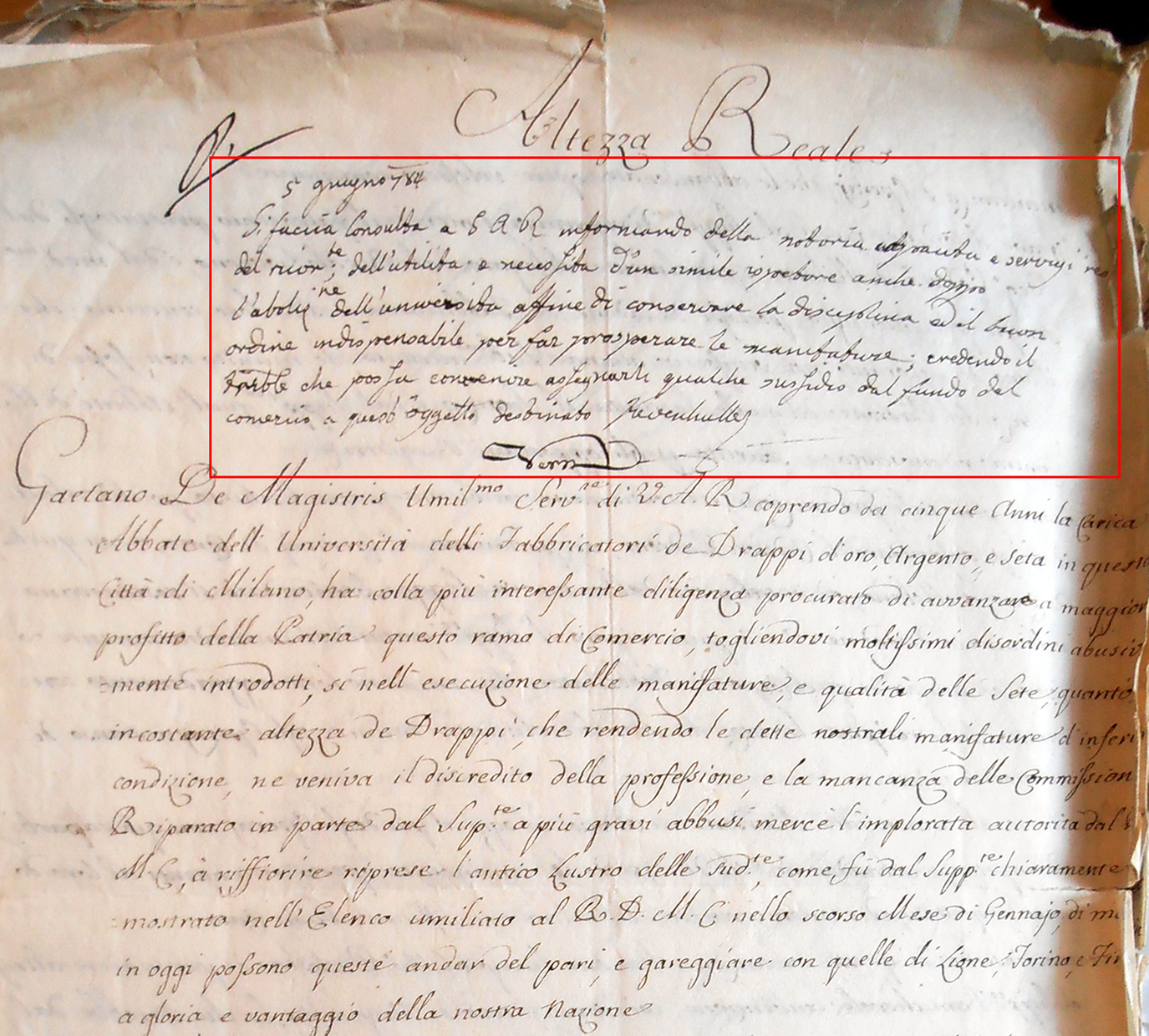

The form of a document can sometimes reveal more than its content. That is certainly the case for a report sent in 1784 to the government of Milan by Gaetano De Magistris, the decan (abate) of the silk weavers’ guild. In his letter asking for a reward for his zealous work, the decan offers a detailed account of his interventions to maintain order in the city's textile workshops. The report was received by Pietro Verri (1728–1797), the most prominent Italian political economist of the eighteenth century, employed at the time as a councillor in the government. Even if the demise of the guild system in Milan had begun nine years before, Verri seems astonished at the prolific activity the document revealed and suggested, writing in the margins of a page, that perhaps it would be necessary to discuss the “usefulness and necessity of such an inspector even after the abolition of the guilds in order to preserve discipline and good order in the factories” (Figure 1).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Pietro Verri's note on workers’ discipline written by hand on Gaetano De Magistris's report. Photograph by the author.

Courtesy of Ministero dei Beni e le Attività Culturali N. 5070.

The abolition of the guild system in Italy followed the trend across eighteenth-century Europe. Decrees abolishing craft associations were enacted in France (1791), Spain (1840), and Austria and Germany (1859–1860), as the growth of science, technology, and industrialization, the development of the factory system, and changing ideas about the economy and the rights of common people led to a decline of the merchant and craft guild system that had flourished between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries. As a new contractual view of society spread across Europe, the need to enforce the obedience of workers under a new legal paradigm emerged as a common dilemma: how to express the apologia of regulations using the new language of economic individualism?Footnote 2 This article examines how this issue was addressed in the Duchy of Milan, where ideas about freedom of contract fostered by Lombard Enlightenment reformers such as Pietro Verri and Cesare Beccaria were challenged by continued requests to enforce corporal punishment and imprisonment to ensure attendance at work.

The article begins by describing the demise of the guild system as a result of a royal decree in 1764 that created parallel legislation to the guild statutes. Inspired by the model of domestic service, this edict became the only legal basis for punishing workers who took advantage of their new margin of freedom after the abolition of the guilds. The article then retraces the ideological background of the new regime of freedom of work and trade that was supposed to govern economic life after the abolition of the guilds’ privileges. Finally, in discussing the effectiveness of these reforms, I investigate the daily workshop interactions in the main Lombard industrial sector, silk fabric production, by looking at some examples of conflict at work and punishments used by the authorities.

Free Contracts and Good Faith in the Age of Reform

The discussion about the role of guilds in the pre-industrial economy has always fascinated historians. The last decade was marked by the fierce debate between Sheilagh Ogilvie and S.R. Epstein concerning the guilds’ ability to guarantee quality, skills, and innovation. Ogilvie argued that corporations were essentially a rent-seeking coalition blocking economic development.Footnote 3 They prevented outsiders (foreigners, women) from accessing the trade, avoided innovation, and could not guarantee the quality of products while artificially raising prices. Epstein, on the contrary, stressed that the guild successfully responded to information asymmetries in times when markets had high transaction costs, fulfilled an important role in protecting innovation, and helped to transmit technical knowledge through apprenticeship.Footnote 4

Until recently, in Italy, historiography has mostly posited the pernicious role of the guilds, especially in the early modern period, with judgements oscillating between their uselessness and harmfulness to economic growth.Footnote 5 However, an extensive quantitative analysis of the sectoral distribution of the guilds has recently shown that their expansion was often located in fast-growing industries with a strong outbound orientation.Footnote 6 That evidence undermines the widespread belief that guilds represented the last bastions behind which backward sectors hid to preserve their rents on the city market. The Italian case shows mainly that these medieval institutions experienced, during the modern period, a “genetic mutation towards flexibility spurred on by mercantile capital” that allowed them to sustain the growth of specific sectors.Footnote 7 Furthermore, even within the city walls, regulation and freedom were deeply entangled as urban markets structurally integrated both guilded and non-guilded labour.Footnote 8

The example of early modern Milan is illustrative of this dynamic, as the guild's stratification mainly reflected the functional adaptation to the redefinition of the productive and commercial environment of each sector on the international market.Footnote 9 More specifically, the definition of the gold and silk's guild landscape – between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries – was characterized by a double process of polarization and hierarchization promoted by a small elite of merchants.Footnote 10 On the one hand, in little more than thirty years, four new guilds were created with no formal autonomy and were placed directly under the control of the silk and gold merchants’ guild.Footnote 11 On the other hand, the members of the powerful silk weaver guild progressively lost their capacity to operate autonomously on the market and became either “proletarianized” workers or subcontractors on behalf of merchants.Footnote 12 Therefore in their fully matured period, between the seventeenth and eighteenth century, Milan's silk guilds became essentially tools to ensure control and discipline rather than protect the equality between their members.

The fading of the guild regime started in the early eighteenth century, when direct subsidies and tax exemptions were granted to some merchant-manufacturers as part of the mercantilist policy promoted during the reign of Charles VI.Footnote 13 The arrival of big, privileged manufactures in the textile sectors increased labour demand and the mobility of weavers between different firms. Before the abolition of the Milanese guilds, this motivated the creation of a parallel and competing regulation of the workforce: the royal edict on the discipline of manufactures of 30 May 1764.Footnote 14 This edict reflected the particular condition of manufacturing work at the time, mixing elements typical of factory regulations with residues characteristic of guild statutes. As the state took over manufactures through direct financing, any infringement of their proper functioning could be construed as a direct attack on the sovereign will. Misbehaviour by workers was no longer seen as a matter for the guilds but rather as an attempt to “defraud Her Majesty's clear intentions”, as written in the text's preamble.Footnote 15

The first part of the edict is devoted to attendance at work. A worker could not be admitted to a new master without the previous master having released him from all duties. The circulation of practitioners had to be regulated, and their activity needed to be continuous. An inactive worker became a supposed culprit, the edict threatening to make the unemployed fall under the regime of idlers. The second part is devoted to “fidelity”, which had to be “universally observed, but most unquestionably in this context”. The edict threatens that anyone who stole “things from factories” or “returns a lesser weight of what has been delivered to him to be worked on” must be publicly whipped “with the sign ‘thief of manufactures’ around his neck”. With the motivation of avoiding trafficking, the edict limited the legitimacy of informal trade. A presumption of guilt fell on those who bought from small traders who did not have a shop of their own. Finally, the third part of the edict attacks any possibility of a union or alliance between workers to increase wages: individual pay was not supposed to be influenced by any factor external to the contract.

The importance of this decree – in fact, the only legal basis mentioned in the disputes between employers and workers, at least until the 1830s – should not be underestimated. It completely discarded the statutory self-regulation of guilds in favour of sovereign legislation that made labour discipline a police matter. The edict was also the first attempt to define a new contractual form of managing the workforce, but a very particular contractual model emerges from the text. In Italy, before the civil law reform at the end of the nineteenth century, wage labour was fitted into the narrow limits of one of the rental contracts from Roman civil law, more specifically, the locatio conductio operarum.Footnote 16 The locatio conductio operarum presupposes, like any consensual contract in Roman law, bona fides (good faith).Footnote 17 Bona fides is a complex and stratified legal concept as it does not refer to respect for the terms of the agreement in the abstract space of the will but is configured as an attribute of the person. Hence, it is a notion deeply intertwined with social hierarchies: good faith can only be presumed of a person who is recognized as worthy of it.Footnote 18 The status of the merchant attested good faith and, unlike craftsmen, following the Lombard reform, merchants preserved their status even after the abolition of guilds through the maintenance of a special and separate jurisdiction in matters of trade.Footnote 19 In contrast, the new work regulations of the 1764 edict were directly transferred from the domestic service model, with its corollary of prison sentences and public whipping. Even though it was explicitly drafted for privileged factory workers, two decades later, the edict evolved into the only legal basis allowing for the functioning of the Lombard silk industry after the formal abolition of the guilds.Footnote 20

Behind an “apparent universality”, therefore, we observe the transition to a very peculiar form of contractual society.Footnote 21 Concerning trade, freedom of contract was based on the presumed good faith of merchants; concerning labour, however, such freedom was based on the putative disloyalty associated with domestic workers.Footnote 22

From Labour Control to Product Control

In Lombardy, most guilds were gradually abolished from 1775 onwards. Even if the silk weavers’ guild was not formally eliminated until 1787, the constraints previously set by the statutes were unofficially abandoned a few years earlier. In 1784, the State Chancellor Anton von Kaunitz (1711–1794) declared that the size and quality requirements for cloths were null and void because “the dealer must always comply with the buyer's wishes”.Footnote 23 Workers who wanted to change their occupation could no longer be prevented from doing so because such a ban “does not seem to correspond to the principles of freedom that the industry demands”.Footnote 24 The overcoming of the guild system was completed by the creation of eight Chambers of Commerce in 1786. They co-opted merchants, bankers, and large manufacturers (fabbricatori nazionali) into a single organization.Footnote 25

These reforms were part of a vast fiscal, economic, and jurisdictional overhaul of the state spanning the eighteenth century.Footnote 26 From the early 1760s, the question of what institutional frame could ensure “public happiness” became pivotal for the young civil servants overcoming the old regulatory system.Footnote 27 For these representatives of an Enlightenment imbued with confidence in the new truths of political economy, the moral aim of reform was to reorganize economic life along competitive principles. As Verri put it, liberty was the “secret life of commerce”, enforcing fairness and prosperity.Footnote 28 The general view of these intellectuals, working closely with Vienna to modernize the Duchy of Milan, was that the responsibility for dealing with the new economic freedoms should fall to each individual subject. The state was only supposed to take care of breaches of good faith through the severe punishment of acts of fraud.Footnote 29

One of these civil servants was councillor Pietro Secchi (1734–1816), entrusted by Vienna to abolish the guilds. Alongside better-known figures such as Verri and Beccaria (1738–1794), Secchi was a member of the liberal intellectual circle Academy of Fisticuffs (Accademia dei Pugni).Footnote 30 He was involved, as most European pre-classical economists were, in political discussions about policies for the grain trade and was a strong supporter of freedom of labour.Footnote 31 However, some doubts about such an approach to industrial labour were voiced in Vienna. Chancellor Kaunitz, amid the abolition of the guilds, expressed his concern that excessive freedom to undertake a craft might jeopardize the reform. He asked, therefore, whether it would not be wiser to maintain some regulatory system to verify the dexterity of practitioners. The response to his concerns makes clear that the interlocking of regulations and guilds was typical of a time when the spirit of reform had not yet had to confront the everyday necessities of trade. Secchi explicitly opposed this idea and replied to Kaunitz that “all these verifications carried out by the current regulations have, with time, degenerated into a simple and expensive formality”.Footnote 32 For Secchi, the maintenance of an entrance examination for the exercise of crafts would inevitably end up restoring those pernicious constraints that prevented industry from prospering. By opening the Pandora's box of “regulations” that had been closed so painfully, one could only spread the evil of the “monopoly”.Footnote 33

According to the plans of the Lombard reformers, what was previously supposed to be ensured by trade guild statutes should now be derived from the extrinsic characteristics of the objects traded on the market. A voluntary public mark should certify the quality of the goods. Yet, goods without such a mark could continue to circulate since anyone who wanted to buy unmarked products “should attribute to himself the deceit to which he has exposed himself”.Footnote 34

Probably thanks to the intervention of Verri mentioned at the beginning of this paper, the 1786 edict that established the Chambers of Commerce provided for introducing two Expert Commissioners for Manufactures and Workers’ Discipline (Commissari periti per le Manifatture, e disciplina degli operaj).Footnote 35 However, the conviction that compulsory and binding labour control had to give way to a more modest and voluntary product control was shown in Beccaria's approach, adopted in 1787, to rewrite a regulation for silk manufactures. The issues addressed to the Chambers of Commerce by the famous jurist in charge of the Milanese government's economic department focused mainly on how to guarantee the quality of cloth. And his reply to merchant-manufacturers who demanded the application of corporal punishment against recalcitrant workers sounds like an Enlightenment manifesto: “[L]et the manufacturers make such agreements with their workers as are in their own interest, and it will be easier for them to obtain from the obligation of a free man's contract what cannot be obtained, unless badly and rarely, from the force used against a slave.”Footnote 36

Silk Weaving in Lombardy

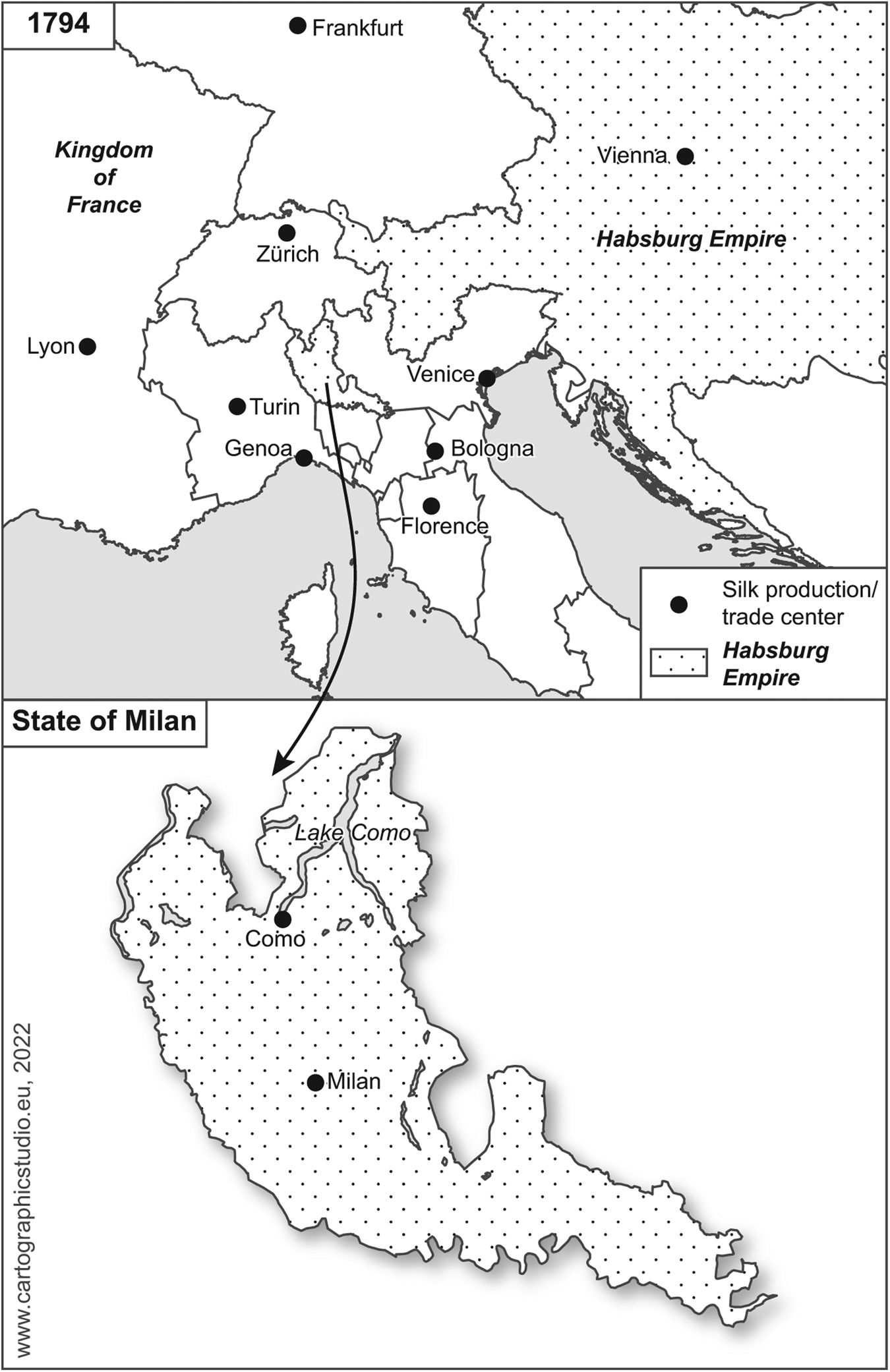

This period of profound institutional changes in the Duchy of Milan coincided with a time of intense growth for the Lombard silk industry as the Habsburgs’ desire to encourage greater integration between the various regions of the empire opened the door to the Vienna market for Lombard silk fabrics. The export of silk textiles from the Duchy of Milan (Figure 2) almost quadrupled between 1769 and 1790.Footnote 37 The most significant increase took place in 1785 when, in just one year, export value jumped from 328,036 to 663,811 florins as Lombard manufacturers enjoyed an exemption to the import ban of foreign textiles in the Hereditary Lands (Erblande).Footnote 38 Even after the abolition of the guilds, Lombard silk weaving (Figure 3) remained mostly an urban affair.Footnote 39 The control exerted by the merchant class over the different silk guilds since the early modern period removed any incentive to relocate the last stage of production to the countryside, in contrast to several other textile cities of northern Italy.Footnote 40

Figure 2. Map of the Duchy of Milan (Ducato di Milano) at the end of the eighteenth century, with silk production and trade centres and their trade connections throughout Europe.

Figure 3. A representation of a Lombard silk weaving workshop. In the back, a man working on a four-shaft weaving loom, in the front a woman winding some silk thread.

Arti e Mestieri m. 4-23, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli, Castello Sforzesco, Milan. With permission.

In 1785, in Milan, there were 1384 active silk looms.Footnote 41 Even if it was not coming close to the high-quality products of Lyon, production in the capital was pretty diversified, featuring cloths of all kinds, ribbons, silk hosiery, and other minor productions. Exports played an important role, but the presence of a large urban market and the ability to modulate production according to a new domestic demand (i.e. by reducing the production of less popular fabrics such as damask in favour of light cloths and shawls) allowed a significant proportion of silk textiles to be sold within the city's walls. The new tariffs also allowed the development of another regional centre, Como, where 725 looms were in use this same year.Footnote 42 Here, the range of products was limited to plain fabrics. Production was highly dependent on foreign demand and proved volatile, with frequent booms and busts. Along with Vienna, the German fairs (especially Frankfurt) played a significant role. Another outlet for Como silk fabrics was Russia and the Baltic territories, where costumers were less exigent in terms of quality.Footnote 43 Despite the differences, when it comes to silk, Como and Milan formed one single labour market “since between these two cities there's always been a communication of artificers, if we can say, also of disorder and vices of the same kind”, as the royal provincial delegate put it in 1787.Footnote 44

The dominant form of work organization at the time was typical of what historians call the “putting-out system” (a means of subcontracting work). A small group of merchant-manufacturers (fabbricatori) were in charge of the commercialization of the product. They entrusted the silk yarn to the master weavers (capi tessitori or capi fabbrica), who turned it into cloth. The master weaver was a liminal figure somewhere between artisan and subcontractor. Sometimes, he worked at home on his own looms with the help of his relatives; other times, he was a middleman between weavers and merchant-manufacturers.Footnote 45 To fill the orders by the merchant-manufacturers, the master weaver hired salaried workers (tessitori) to work on his looms. Even if they did not have any form of stable organization, these workers could be likened to the French journeymen since, generally, they were very mobile, did not possess their own loom, and were paid by the piece. Production was most often carried out in the master house, but sometimes, following the wave of abolitions of several monastic orders, the main manufacturers started to concentrate looms in old urban monasteries in both Milan and Como.Footnote 46

We must be cautious in fixing too static a picture of production and social classification. Even before the abolition of the guilds, the structures of silk weavers’ associations were very elastic according to the needs of merchant capital. Some weavers were allowed to be the master for a limited time, even without a formal inscription to the guild, and it was easy for foreigners to join the guild.Footnote 47 After the demise of the guilds, the ideal tripartition of the putting-out system (merchant-manufacturer, master weaver, weavers/workers) was continually reconfigured by variations in the demand for cloth and the supply of silk yarn. Since formal apprenticeships had disappeared, in times of high textile demand, all kinds of people came to work on the silk looms. Furthermore, merchant-manufacturers now issued their orders directly to the weavers without the intermediation of those who had qualified as master weaver under the former guild regime. On the contrary, in times of good cocoon harvest, master weavers started to act as manufacturers since falling silk prices meant they could afford to produce their own cloths and put them on the market.Footnote 48

Desacralizing Saint Monday

Since one of the main features of the pre-industrial labour market was instability, it is only by considering market trends that we can make sense of working-class practices. In 1786, the merchant manufacturers of Como complained that the silk weavers were

always insatiable about their pay (although they are increased for each quality [of cloth]), they disturb the manufacturers, inciting them to compete to increase wages. Once such an increase is obtained, workers try to improve it more and more, making their claims through intemperance and sloppy work [and] preventing commerce from flourishing.Footnote 49

Merchant-manufacturers were echoed some months later in such views by the political authorities who noted that silk weavers not only plotted for more money and reduced their workloads, but also shortened their working week: “[I]nstead of being made up of six working days, as it is for everyone, it has become for them of three or four days.”Footnote 50

The voluntary inactivity at the start of the week (referred to as “Saint Monday”) was a well-known practice in pre-industrial society and has been subject to multiple interpretations among scholars. In his seminal essay on time and work discipline, British historian E.P. Thompson argued that Saint Monday was embedded in the dense web of artisan customs and one mark of workers’ resistance to the intensification of work.Footnote 51 Another interpretation, by the Italian historian Simona Cerutti, suggests that Saint Monday was instead a time of autonomous organization by workers. Monday was a very busy day. On this day, workers would meet outside their workplaces, redistribute workloads in taverns, or collect alms to help their fellow journeymen. Thus, Saint Monday was not just a chance to offer resistance, but also experience another form of work organization that was distinct and alternative from that of the masters.Footnote 52 The progressive disappearance of this practice has been primarily addressed in terms of a shift in the balance between toil and leisure in working-class households.Footnote 53 Jan de Vries has cast this change in terms of economic growth, theorizing that the household choice to increase labour supply participated in an “industrious revolution” that paved the way to industrial take-off in Western Europe.Footnote 54 Since then, labour historians have returned to the issue of working time, putting forward less linear and univocal arguments. Several scholars have underlined that the intensification of work during the long eighteenth century is fuzzier than De Vries claims and that both masters and workers were fully aware of the centrality of the “struggle for time” earlier than what E.P. Thompson admitted.Footnote 55 This revisionism allows us to put forward a third explanation of Saint Monday since, in the case of the Lombard silk manufactures, this practice seems to have been followed for the more prosaic reasons of keeping wages in line with the high demand for cloths.Footnote 56

The letter cited above by the Como intendant complaining about weavers’ absences at the start of the week was written in early 1787 after several months of positive trends in the cloth market. Only a few months later, the situation changed radically and with it, the behaviour of the weavers. A poor cocoon harvest in the summer and the decrease in cloth demand because of the beginning of a new Russo–Turkish war (1787–1792) threw the silk factories into a rude economic crisis. At the beginning of the autumn, the Como intendant warned that the spinners had practically ceased work, that weavers would soon do so, and that crowds of unemployed workers had started to roam the towns and loot the fields.Footnote 57 What about the weavers still employed? Beccaria was told by the master weavers that the workers presently “have become more docile and active so that now that work is scarce, they not only work five full days of the week, but even on the famous Monday”.Footnote 58 Remarkably, then, it was at the very moment of economic crisis and decreased labour demand that what was thought to be the ineradicable indolence of weavers on Mondays seemed momentarily to vanish.

In contrast, the years 1794 and 1795, just before Napoleon Bonaparte's First Italian Campaign, saw a further boom for the Lombard silk industry as French producers could no longer supply the European silk cloth market because of the war. As cloth demand rose again, complaints immediately resumed against Saint Monday. The Chamber of Commerce of Como criticized weavers “as never before [so] insolent, saying that they want to work whenever they like, and so they do, since the weavers’ taverns are full on the first days of the week”.Footnote 59 It seems that manufacturers even had to dismiss several orders as their employees were working “not even half of what they would have done in bad times”.Footnote 60

One could argue that the masters and manufacturers always complained about the lack of industriousness of their employees. But we can observe not just general grievances about the vicious nature of the workers – though these were not lacking, as we will see – but detailed allegations explicitly linking the state of trade to the voluntary modulation of working time. In my view, this complaint appears to be coherent with the interpretation of Saint Monday as a way to restrain labour supply in order to maintain high wages.Footnote 61

The manufacturers, on their side, expressed their frustration that using wages as leverage seemed to have the opposite effect of what was expected: the more they were paid, the less the weavers worked. In the words of the Chamber of Commerce of Como:

Experience has shown that in the years 1786 and 1787, during which time prices were raised by two soldi for every auna, the weavers abandoned themselves to all sorts of vice, they loaded themselves with debts, they worked very little, and badly. As further proof, in the scarcity of the year 1790, the merchants, with one-third fewer workers, had the same quantity of cloth and greater perfection.Footnote 62

I argue that Saint Monday was then part of a dynamic form of wage negotiation that followed its own logic. That logic is certainly astonishing if looked at through the eyes of the nascent political economy, but it is entirely consistent with the cyclical variations of the silk fabric market.

Private Concerns and Public Unrest

If raising wages did not work as the merchants expected, what means of constraint could be considered to ensure that every worker remained committed to their assigned task?

A first punishment, strongly urged by the merchant authorities, was to treat absent workers as idlers in order to take advantage of the dissuasive effect of incarceration. However, this approach proved challenging to implement, given the social unrest it might provoke. At the end of 1790, faced with the insistence of the manufacturers to act, the government council intervened to demand “greater caution” in applying the law.Footnote 63 This circumspection was undoubtedly dictated by an awareness that the social stability that permitted the functioning of the silk manufactures was somewhat precarious. The possibility that the private concerns of the merchants might turn into public unrest seemed to pose a persistent threat. A weaver's riot had shaken the town of Como only a few months earlier, with hundreds of workers demanding the head of the Chamber commissioner.Footnote 64

The other option for constraining absentee workers was the sequestration of their loom shuttles.Footnote 65 Once again, it was the commissioner of the Chamber of Commerce who oversaw removing such tools to force the weavers to show up at the Chamber to recover them and, in the process, be served a formal injunction to respect their contractual commitments. In practice, such operations were often complicated due to the animosity of the weavers and their wives, who greeted the commissioner with insults and even stones.Footnote 66 In Como, during the summer of 1791, intimidation became so frequent that the commissioner was too scared to leave the Chamber, afraid of the threats he received “if he had dared to go to visit the looms and take possession of the shuttles of those whom he found absent from work”.Footnote 67

Moreover, it was precisely at times of intense work that absences were most serious and most challenging to constrain. In September 1795, orders abounded with the upcoming German fairs, and the Chamber of Como insisted that several absent weavers be imprisoned “to serve as an example to make the others maintain their commitments”.Footnote 68 However, this show of force was cut short: one weaver spent a few days in jail before his master pleaded for his immediate release because he needed him to finish a cloth.Footnote 69

The manufacturers were well aware of these contradictions and complained about the ineffectiveness of the measures available to them. When questioned about the alternatives that might be made available to them in a new regulation for silk workshops, they replied that

if suspension from work were a punishment that did not encourage idleness and vice, it might be appropriate in this case. But experience has now shown the contrary. Therefore, to avoid such inconvenience, it is in the Chamber's opinion to punish those absent from work for a depraved cause (causa viziosa) by forcing them to work chained to the loom.Footnote 70

Although one might have expected a liberal backlash to such a suggestion, much more pedestrian arguments seem to have prevented its implementation. As the intendant explained in his response to the Chamber of Commerce's proposal, chaining a worker to his loom “can be the cause of many disruptions: a grouping of his comrades with the aim of freeing him can take place any time”. And his advice, at the time, was to “stay away from anything that can cause any excitement”.Footnote 71

Nevertheless, the Chamber's proposition was reiterated in 1794, but the Duchy government never accepted it.Footnote 72 On the contrary, the Milan authorities pushed for exclusively pecuniary sanctions against workers who did not respect their contractual commitments. As might be expected, the merchants of Milan and Como, when consulted, opposed what they deemed to be a relaxation of the rules, but it is the motivation for their opposition that is especially interesting. The Chamber political magistrate (Magistrato politico camerale) alleged that they considered that “the punishment in case of transgression seems to be the only one that can contain such people who have no property to lose” (nulla ha da perdere dal lato della robba).Footnote 73 Maria Luisa Pesante has identified the servile roots of the modern wage in a specific conception of the salaried worker's condition going back to natural jurisprudence. On the one hand, despite his engagements, the wage earner cannot entirely cede what he is renting, namely, his workforce. On the other hand, he lacks any other property entitlement that he could alienate.Footnote 74 It is this double deficiency that legitimates the legal coercion to work. The remark of the Lombard manufacturer about workers’ insolvency, then, is crucial since it evokes the limits of any attempt to cast the transition to a contractual order as a peaceful and consensual one in which employer and worker exchanged on equal terms. For the merchants, the new “free labour” system could not function because one of the parties to the contractual relationship lacked the two prior and necessary attributes of the civil law regime: good faith and private property.

Debt, Pay, and Runaways

Even if incarceration and physical coercion were an ever-looming threat, such forms of punishment appeared unmanageable for commercial and political reasons. As such, and despite the manufacturers’ petitions, debt remained the most common form of labour constraint. The use of wage advances was deeply rooted in the pre-industrial organization of work. Since any worker was officially prohibited from leaving his workplace while he was indebted to his master, advances were used to enforce loyalty, fix a highly mobile labour force to the workplace, and limit competition between employers.Footnote 75

During the turbulent years in Lombardy immediately after the guild system's abolition, weavers’ debts exploded because of the need to try to keep up with the growth of the textile market. In this regard, there was no discontinuity before or after the abolition of guilds; instead, the debt spiral of the end of the eighteenth century was mainly related to the instability of the international cloth market. As the market rose, “mainly instigated by manufacturers”, master weavers started to propose to workers to pay their debts if they moved to their workshop.Footnote 76 At the same time, to try to convince them to stay, the master weavers were forced to increase the advances that, in times of buoyant economic activity, became a de facto pay raise. During one of these favourable trends, the master weavers in Como declared that they were “threatened by the workers to force their hand and give them what they wanted” and begged the authorities to intervene “by any means to be exempted from giving the workers any money”.Footnote 77 This kind of petition opens up a more ambivalent interpretation of credit in the pre-industrial work organization. Andrea Caracausi has already pointed out that textile workers often pretended advances as insurance against insolvent masters or to face the cost of moving to a new town.Footnote 78 The Lombard case shows that they were not only a tool of labour constraint but were also a symptom of the capacity of the weavers to exploit the position of strength they had in certain moments since it was common that the debt was only partially refunded or not paid back at all as the workers ran away from the workshop. The continual complaints about the comings and goings of workers between Como and Milan are evidence of this credit-driven mobility.Footnote 79 Furthermore, the bond created by the debtor-creditor relationship was a reciprocal one. In times of low cloth demand, the masters were encouraged to continue to employ the indebted workers “with the hope of reducing or extinguishing the debt of each”. At the same time, the weavers “resist[ed] any attempt to save anything on their wages in return for the debt”.Footnote 80

As has already been pointed out, the ubiquity of credit in the modern economy was not only motivated by the limited amount of money available. It constituted a means to cement economic relationships and mediate the uncertainty that was necessarily inherent to such exchanges at any level.Footnote 81 According to Craig Muldrew, the social trust at the base of this “economy of obligation” was inextricably linked to communitarian bounds placed under strain by increasing market activity.Footnote 82 While it is true that this movement pushed towards an increasingly contractual society, as far as labour was concerned, the form of the contract was influenced by the peculiar relationship of the parties to “good faith”, as I have emphasized in this article. Freedom of contract could not go along with freedom of movement for workers, as demonstrated by the fact that limitations imposed on the displacement of working men and women were not only maintained after the abolition of the guilds but started to be directly enforced by the state through specific devices combining mobility restraint, identification, and debt control.Footnote 83

In Lombardy, it was only at the beginning of the nineteenth century, amid the Napoleonic conquest, that the prefecture began to track down missing workers. Some weavers were jailed; many more were returned to work by the police authorities.Footnote 84 The chief of police even started to settle arrangements to stagger the debts owed to the masters with money deposited monthly by the debtors to the prefecture office.Footnote 85 The involvement of police authorities in punishing breaches of contract represents a persistent and significant infringement of the legal logic that distinguishes civil from penal law.Footnote 86 Furthermore, the manufacturers go as far as to suggest that the scope of labour discipline should no longer be limited to the workshop but may embrace the whole town. Any weaver caught in places like taverns should be brought back to his master:

[I]t would also be good for the universal benefit of the workers themselves if the police could keep an eye on them and, if they find them idle and wandering on weekdays outside of mealtimes, they [should] send them back to their respective jobs. They [should also] frequently visit the taverns and inns, and if they see workers drinking and gambling outside the aforementioned hours, they [should] chase them away from there and send each one to his job, threatening the most reluctant with prison.Footnote 87

Such punishment was characterized as being inflicted for the worker's own benefit. “Working the whole week, they would spend less and earn a lot more”, thanks to which “gradually we would remove that innate [sic!] rooted indolence which unfortunately rules them”.Footnote 88

Weavers or Idlers?

The French domination was not only a period of police reform but ushered in a time of deep crisis for the Lombard silk fabrics industry. In addition to the loss of the crucial Viennese market, Northern Italy suffered from a shift in French economic policy to turn the region into a simple supplier of cheap raw silk for Lyon. By 1800, in Como, there was only a third of the number of active looms that had existed on the eve of the French invasion in 1795.Footnote 89 Faced with unemployment, some weavers set off for Veneto while others went to Northern Europe. However, the Chamber of Commerce of Como declared that among the workers who remained in town, there were “some who would be well suited to work [but] they prefer to go to begging in [the] town and in the countryside […] and, rather than conform with their profession, decide to become peddlers or boatmen”.Footnote 90 The master weavers hunted workers for their workshops, especially for auxiliary tasks, “but with no success because those people replied that they would work when they are paid as in the past”.Footnote 91

During the summer of 1810, the parishes of Como were asked to classify the poor; all beggars who wanted to keep asking for alms had to present themselves to the municipal authorities.Footnote 92 In November, the Chamber of Commerce pointed out again that “today there would be work to occupy some of those who remain idle, and who, because of the decrease in the price of work, prefer either to take up another craft or to become vagabonds by begging”.Footnote 93 A month later, in December 1810, the interior minister decided to “repress the idleness and vagrancy of silk workers” and asked the police commissioner to imprison the workers circulating in the town.Footnote 94 However, this drastic measure failed to dissuade the weavers. Less than a year later, in November 1811, the Chamber of Commerce once again complained about silk workers who, invited to return to their looms, refused because “the ordinary and common wage does not give them enough to live on”.Footnote 95

Because the Lombard cloth manufacturers managed to reduce wages to cope with the economic crisis, becoming a silk weaver was no longer an advantageous option for the urban worker. As many workers weaved only in times of high demand for cloth, during crises, they could return to their former profession, find a new one, or start to beg.Footnote 96 Because this form of voluntary inactivity played off when wages fell below subsistence levels, the political authorities had to deal with another form of disguised wage negotiation through the modulation of working time.

Conclusion

Through the preceding analysis of the constraints imposed on work in a significant and growing industry, I have highlighted the gap between the principles of liberty enunciated by the Lombard state reformers like Verri and Beccaria and the pragmatic appeal of constraints imposed on workers’ right to ensure the regularity of their production. Different conceptions of legal responsibility are relevant to investigate how the formal unity of civil law hides the “tutelage of a society to be fortified in its new hierarchies and its new proprietary certitudes”.Footnote 97 In Lombardy, the discussion between the political authorities and the merchant-manufacturers continued for several decades, forcing the constant affirmation of the distance between the officially applied “free labour” regime and the demands to force workers to perform their tasks. In particular, the lack of property and presumed good faith on the part of workers were central elements to explain why manufacturers never claimed that a contractual relationship in a proper civil law regime was possible.

Despite the pressure to reinforce punishment, the debt relation, taking the form of salary advances, stood as the most effective means to try to discipline the workers. In this regard, there was no significant disruption compared with the guild regime, but a dynamic assessment of weaver behaviour suggests a more active role played by workers. For instance, if we consider the state of the international cloth market, we observe that the debts were not only undergone by workers but sometimes obtained as a form of disguised pay raise. A similar approach can help make sense of practices like Saint Monday as a form of struggle to keep wages high or to frame begging by weavers as a decision not to accept low pay under a given amount.

Concerning institutions, by looking beneath the fiction of a contract between equals, it becomes clear that, after the guilds’ abolition, the wage relationship's inherently asymmetric nature was not compensated by political authorities but reinforced by police measures, particularly concerning the mobility of workers.