1. Introduction

In recent years, automated writing evaluation (AWE) has grown in popularity as a source of feedback that can complement teachers’ response to second language (L2) writing. The complementary nature of automated feedback is representative of a system’s adept ability to provide feedback on lower-order concerns (LOCs) (Ranalli, Link & Chukharev-Hudilainen, Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017). It has been suggested that because AWE can take care of LOCs, it has the potential to liberate teachers’ time to focus more on higher-order concerns (HOCs) (Warschauer & Grimes, Reference Warschauer and Grimes2008; Wilson & Czik, Reference Wilson and Czik2016). However, little empirical evidence exists to support this claim. The small number of studies that have investigated the impact of AWE on teacher feedback (Jiang, Yu & Wang, Reference Jiang, Yu and Wang2020; Link, Mehrzad & Rahimi, Reference Link, Mehrzad and Rahimi2022; Wilson & Czik, Reference Wilson and Czik2016) reveals conflicting results, thus warranting more research in this regard. Additionally, little effort has been made by these studies to explore teachers’ perceptions of AWE when they use AWE to complement their feedback. Insights into teachers’ perceptions of AWE as a complement to their feedback can show various pedagogical strategies teachers use to compensate for limitations inherent in AWE (Cotos, Reference Cotos, Liontas and DelliCarpini2018). Because students tend to adopt an attitude toward AWE similar to that of their teacher (Chen & Cheng, Reference Chen and Cheng2008; Li, Reference Li2021), it is crucial to examine teachers’ perceptions of AWE to avoid any negative impact on students. Finally, teachers’ perceptions of AWE are “an important source of evidence – evidence of social validity” (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ahrendt, Fudge, Raiche, Beard and MacArthur2021: 2). Considering the integral role teachers play in making decisions about the implementation of various technologies in their L2 writing classrooms, it has become highly important to investigate teachers’ use and perceptions of AWE as a complement to their feedback.

The current study first examines the nature of pre- and in-service postsecondary L2 writing teachers’ feedback when they used Grammarly, which is making important inroads in L2 writing classrooms (Ranalli, Reference Ranalli2018), as a complement. The study then explores the teachers’ perceptions of the tool. The findings of the study provide a better understanding of how to use Grammarly and similar systems to complement teacher feedback for productive student learning outcomes.

2. Literature review

2.1 Impact of AWE on teacher feedback

AWE is a software program that provides instant automated scoring and individualized automated feedback for essay improvement (Cotos, Reference Cotos, Liontas and DelliCarpini2018). Initially, AWE systems were developed for assessing large-scale tests, such as the TOEFL, with the purpose of reducing the heavy load of grading a large number of student essays and saving time (Chen & Cheng, Reference Chen and Cheng2008). These systems were called automated essay scoring (AES) because of their automated scoring engine (Warschauer & Grimes, Reference Warschauer and Grimes2008). Then, AES systems were extended to include automated formative feedback (Cotos, Reference Cotos, Liontas and DelliCarpini2018) for instructional purposes, and the systems, which received the name AWE, were marketed to schools and colleges. When AWE was introduced for instructional use, there was a concern that it may replace a teacher as a primary feedback agent (Ericsson & Haswell, Reference Ericsson and Haswell2006). Researchers, however, assure that the intended use of AWE is to complement teacher feedback instead of replacing it (Chen & Cheng, Reference Chen and Cheng2008; Stevenson, Reference Stevenson2016; Ware, Reference Ware2011). As such, AWE has the ability to liberate teachers’ time to focus more on HOCs (Grimes & Warschauer, Reference Grimes and Warschauer2010; Li, Link & Hegelheimer, Reference Li, Link and Hegelheimer2015; Link, Dursan, Karakaya & Hegelheimer, Reference Link, Dursan, Karakaya and Hegelheimer2014) because AWE’s automated feedback is more computationally adept at providing feedback on LOCs (Ranalli et al., Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017). However, evidence to support this claim is scarce. To date, only three studies have explicitly investigated the impact of AWE on teacher feedback.

Wilson and Czik (Reference Wilson and Czik2016) conducted a quasi-experimental study in which they assigned two eighth-grade English Language Arts (ELA) classes to the Project Essay Grade (PEG) Writing + teacher feedback condition and two classes to the teacher-only feedback condition. They then asked the US middle-school teachers in each condition to provide feedback as they normally would and analyzed their feedback to examine the impact of PEG Writing on the type (direct, indirect, praise), amount, and level (HOCs vs. LOCs) of teacher feedback. The researchers found that teacher feedback did not change in the type and amount across two conditions. As for feedback level, the researchers found that the teachers in the PEG Writing + teacher feedback condition still gave a substantial amount of feedback on LOCs, despite using PEG Writing to complement their feedback. However, they gave proportionally more feedback on HOCs than LOCs compared to the teachers in the teacher-only feedback condition. Due to the small effect sizes for differences in feedback proportions across two conditions, the researchers claimed that they provide only partial support for the premise that AWE allows teachers to focus more on HOCs.

Link et al. (Reference Link, Mehrzad and Rahimi2022) extended Wilson and Czik’s (Reference Wilson and Czik2016) study by focusing on English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers from Iran and investigating the impact of the Educational Testing Service’s Criterion on teacher feedback. The researchers assigned two classes to either the AWE + teacher feedback condition or the teacher-only feedback condition. The results revealed that unlike the teacher in the teacher-only feedback condition, the teacher in the AWE + teacher feedback condition provided less feedback, but the use of Criterion did not result in a higher frequency of feedback on HOCs, which contradicts the results in Wilson and Czik. However, the results of Link et al.’s study should be interpreted with caution because of the study’s methodological constraints. While the teacher in the AWE + teacher feedback condition provided feedback only on HOCs since Criterion took care of LOCs, the teacher in the teacher-only feedback group gave feedback on both HOCs and LOCs, making a comparison of feedback across two conditions problematic.

Different from the two comparative studies, Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang, Yu and Wang2020) conducted longitudinal, classroom-based qualitative research in which they explored the impact of automated feedback generated by Pigai on Chinese EFL teachers’ feedback practice. The researchers found that of the 11 participating teachers, two resisted using Pigai because they had low trust in its feedback; therefore, their traditional feedback practices remained unchanged. Three of the teachers used Pigai as a surrogate, which resulted in the reduction of feedback time and amount as they offloaded the majority of their feedback to Pigai. The remaining six teachers used Pigai as a complement to their feedback, which allowed them to provide more feedback on HOCs, corroborating the claim that AWE affords teachers to focus their feedback more on HOCs. Similar to Wilson and Czik (Reference Wilson and Czik2016), the researchers noted that there is no division of labor, such as that a teacher takes care of HOCs and AWE takes care of LOCs, as the teachers in their study still provided a considerable amount of feedback on LOCs, despite using Pigai to augment their feedback. Therefore, the researchers suggested that there is a need to refute a dichotomy that leaves feedback on global aspects of writing to teachers and local aspects of writing to AWE.

2.2 Teachers’ perceptions of AWE

Not only is there limited research on the impact of AWE on teacher feedback, but the extant literature has also put little effort into understanding teachers’ perceptions of AWE when they use it to complement their feedback. Teachers’ perceptions of AWE can reveal factors influencing changes, if any, in teacher feedback when AWE is used as a complement to their feedback. However, such information is minimal. A modest number of studies that have focused on teachers’ perceptions of AWE (Chen & Cheng, Reference Chen and Cheng2008; Grimes & Warschauer, Reference Grimes and Warschauer2010; Li, Reference Li2021; Link et al., Reference Link, Dursan, Karakaya and Hegelheimer2014; Warschauer & Grimes, Reference Warschauer and Grimes2008; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ahrendt, Fudge, Raiche, Beard and MacArthur2021) provide insight into the areas of teachers’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with AWE.

For instance, Link et al. (Reference Link, Dursan, Karakaya and Hegelheimer2014) interviewed five English as a second language (ESL) university writing teachers to learn about their perceptions of Criterion. The results revealed that the teachers found Criterion effective for fostering students’ metalinguistic ability, reducing their workload, and providing feedback on grammar. The teachers were also highly satisfied with Criterion’s ability to promote students’ autonomy and motivation. As for the areas of dissatisfaction, the teachers reported that Criterion does not always provide necessary and high-quality feedback, and its holistic scores, though useful, are not always reliable. Li (Reference Li2021) examined three ESL university writing teachers’ perceptions of Criterion. The findings of his study showed that while the teachers were satisfied overall with Criterion, as they found it helpful, they noted that its automated feedback was too broad and occasionally confusing to their students. The teachers also reported that Criterion missed a lot of errors committed by their ESL students. In their recent study, Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Ahrendt, Fudge, Raiche, Beard and MacArthur2021) explored 17 ELA elementary teachers’ perceptions of the AWE system, MI Write, for supporting writing instruction in grades 3–5. They found that the teachers were satisfied with the immediacy of MI Write feedback. They also liked that MI Write helped them determine students’ weaknesses and strengths in writing and helped students understand that writing is a process and revising is important. The areas of teachers’ reported dissatisfaction were that MI Write was misaligned with their instruction. The teachers also voiced their concerns about the accuracy of MI Write’s holistic scores and that the scores would result in students valuing quantity over quality.

Overall, studies report that AWE is often perceived as an “extra voice” and “extra helper” (Li, Reference Li2021: 5), a “second pair of eyes” (Grimes & Warschauer, Reference Grimes and Warschauer2010: 21), and a “good partner with the classroom teacher” (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ahrendt, Fudge, Raiche, Beard and MacArthur2021: 5). This indicates that teachers tend to find AWE useful and hold positive views about AWE, despite being aware of its limitations, particularly regarding the accuracy of its automated scoring and the quality of its feedback (Grimes & Warschauer, Reference Grimes and Warschauer2010; Li, Reference Li2021; Link et al., Reference Link, Dursan, Karakaya and Hegelheimer2014).

2.3 Grammarly

While the bulk of the aforementioned research has focused on commercially available AWE systems, such as Criterion (Li, Reference Li2021; Link et al., Reference Link, Dursan, Karakaya and Hegelheimer2014, Reference Link, Mehrzad and Rahimi2022; Warschauer & Grimes, Reference Warschauer and Grimes2008) and My Access! (Chen & Cheng, Reference Chen and Cheng2008; Grimes & Warschauer, Reference Grimes and Warschauer2010; Warschauer & Grimes, Reference Warschauer and Grimes2008), scant literature exists on Grammarly, despite it being the world’s leading automated proofreader and being increasingly used in higher education and K-12 institutions. In fact, more than 3,000 educational institutions, including Arizona State University, University of Phoenix, and California State University, have licensed Grammarly to improve student writing outcomes (Grammarly, 2022). The small number of studies that have focused on Grammarly’s L2 writing pedagogical potentials show that Grammarly helps to considerably improve students’ writing and that students perceive it positively (Barrot, Reference Barrot2021; Guo, Feng & Hua, Reference Guo, Feng and Hua2021; Koltovskaia, Reference Koltovskaia2020). The studies that have examined Grammarly’s performance reveal that Grammarly is quite accurate in detecting and correcting common L2 linguistic errors, and it provides feedback on more error categories than, for example, Microsoft Word (Ranalli & Yamashita, Reference Ranalli and Yamashita2022).

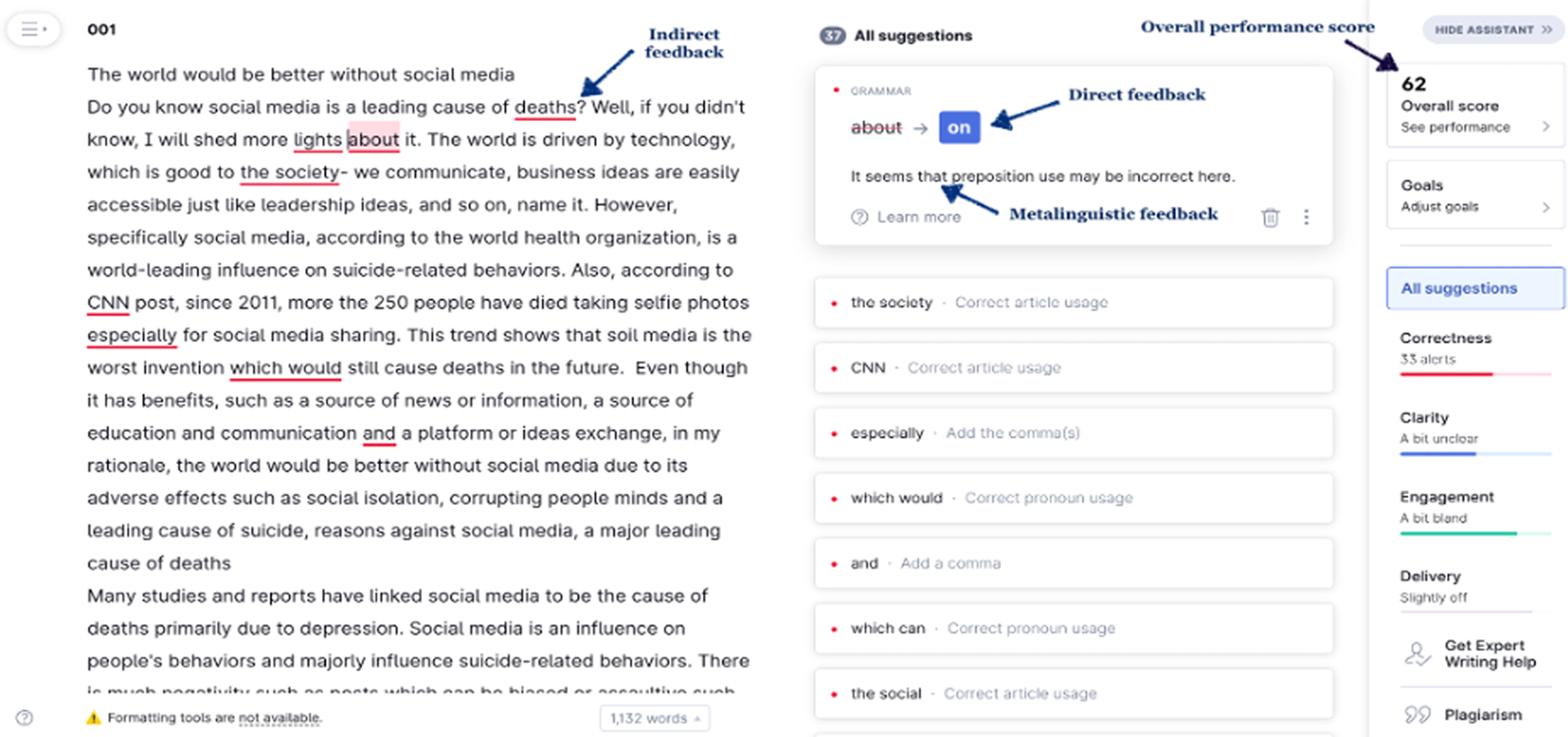

As for Grammarly’s affordances, Grammarly can be used for free, but users can also get Grammarly Premium for a monthly subscription of $12 per month (Grammarly, 2022). Grammarly can be accessed in multiple ways, such as through a web app, browser extension, productivity software plug-in, and mobile device. Once a paper is uploaded to Grammarly’s website, it provides indirect feedback (i.e. it indicates that an error has been made by underlining the error), a metalinguistic explanation (i.e. it gives a brief grammatical description of the nature of the error), and direct feedback (i.e. it gives a correct form or structure) (Figure 1). It is noteworthy that the free version of Grammarly, which was used for this study, provides feedback on five error types, including grammar, punctuation, spelling, conventions, and conciseness. Apart from feedback on errors, Grammarly also provides an overall performance score from 1 to 100 that represents the quality of writing. This feature was not the focus of the study. Finally, Grammarly generates a full performance report that contains such information as general metrics, the performance score, the original text, and feedback on errors, and it can be downloaded in PDF format.

Figure 1. Grammarly’s interface

2.4 Research aim and questions

This study first examines the nature of pre- and in-service postsecondary L2 writing teachers’ feedback when they used Grammarly as a complement. The studyFootnote 1 then explores their perceptions of the tool. The study was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. What is the nature of L2 writing teachers’ feedback when they use Grammarly as a complement?

RQ2. What factors (if any) influence teacher feedback when using Grammarly?

RQ3. What are L2 writing teachers’ overall perceptions of Grammarly as a complement to their feedback?

3. Methods

3.1 Participants

Of the 15 graduate teaching associates pursuing their doctorate or master’s degree in applied linguistics and working in an L2 writing program at a US university, six consented to participate in the study. They were three in-service teachers, who were teaching one or two sections of undergraduate and/or graduate L2 writing courses in the program, and three pre-service teachers, who were observing courses taught by in-service teachers. The six participants were Mik, Mei, Maria, Rob, Jackson, and Heaven. Table 1 shows their background information.

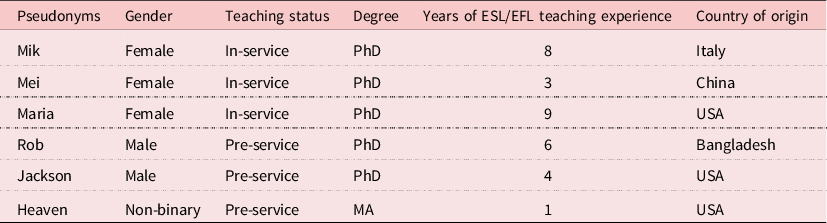

Table 1. Participants’ background information

3.2 Procedures

Because data collection began in the middle of the semester and during the COVID-19 pandemic when L2 writing courses were taught online, implementing Grammarly into those courses was not practical, as this could disrupt the classroom flow in already unusual circumstances. Therefore, the participants were given a hypothetical scenario that asked them to provide formative feedback on students’ rough drafts and use Grammarly to complement their feedback (see supplementary material for the hypothetical scenario). The participants were given 10 randomly selected rough drafts of the argumentative essay written in an L2 writing course offered to freshmen whose first language was not English. The course focuses on expository writing with an emphasis on structure and development from a usage-based perspective, with special attention paid to sentence and discourse level of ESL. The essays were written during the fall 2018 semester and extracted from the participating university’s corpus. In the argumentative essay, the students were asked to write an article for an imaginary Discover Magazine, arguing about one invention the world would be better without (see supplementary material for the argumentative essay prompt). Along with 10 essays, the participants also received, for reference, the assignment rubric (see supplementary material for the assignment rubric) used for summative assessment and the Grammarly report for each essay downloaded from Grammarly’s website. Although the participants were given reports that contained Grammarly feedback for the purpose of ease, they were asked to independently run the essays through Grammarly to understand how Grammarly functions. It is noteworthy that the participants did not have prior experience using Grammarly. Additionally, all the participants were familiar with the assignment and knew how to evaluate students’ essays because they were either teaching or observing the L2 writing course. Feedback provision took two to three days, and, after that, the participants had an individual semi-structured interview with the researcher. The interviews were conducted virtually via Zoom and audio/video-recorded. The interview consisted of three parts. In part one, the participants were asked to provide their demographic information (e.g. degree, teaching experience, country of origin). In part two, the participants were asked about their prior experience with AWE and Grammarly. In part three, the participants were asked about their perceptions of Grammarly as a complement to their feedback (e.g. How did you feel about using Grammarly to supplement your formative feedback in this scenario?). There were 17 questions in total, and the interview lasted for about 40 minutes with each participant (see supplementary material for the interview questions). Prior to conducting the interview with the participants, a brief pilot interview was carried out with a colleague who graduated from the applied linguistics program at the participating university. The questions were slightly modified for clarity during that interview.

3.3 Data analysis

Each participant’s feedback offered for 10 essay drafts and recordings from the semi-structured interview were used for data analysis.

The participants’ feedback was analyzed to answer the first research question that focuses on the nature of L2 writing teachers’ feedback when Grammarly is used as a complement. The author first generated the error categories rubric based on previous literature (Ene & Upton, Reference Ene and Upton2014; Ferris, Reference Ferris, Hyland and Hyland2006) for coding. In the initial rubric, teacher feedback was divided into two feedback levels: higher-order(level) concerns (herein HOCs) and lower-order(level) concerns (herein LOCs). HOCs were operationalized as feedback that focuses on the discourse level, including content and organization/coherence/cohesion. LOCs were operationalized as feedback that focuses on the form level, including vocabulary, grammar/syntax/morphology, and mechanics (see supplementary material for the rubric of error categories). The author and a professor at a US university, whose research centers on written corrective feedback, independently coded each participant’s feedback point using the error categories rubric. It is noteworthy that the participants provided their feedback electronically in Microsoft Word, and each intervention in a comment balloon that focused on a different aspect of the text was regarded as a feedback point. The coders then had a meeting in which they discussed the rubric and compared their initial codes. In the meeting, the coders decided to modify the rubric by including codes that emerged from the data itself. In addition to HOCs and LOCs, the coders included such codes as general feedback, positive feedback, and Grammarly feedback evaluation. The general feedback code was used when a teacher provided feedback on the overall quality of an essay by focusing on both HOCs and LOCs. For example, “This essay draft has many run-on sentences. Ideas in the counterargument paragraph were well-presented. A title is needed for this essay” (Mei). The positive feedback code was used when a teacher praised a student for achievement or encouraged them about performance. For example, “This is a strong opening sentence, and one that captures reader attention. Good job!” (Heaven). The Grammarly feedback evaluation code was used when a teacher made some notes on Grammarly’s performance. For example, “One of the things to keep in mind with Grammarly – and spellcheck – is that sometimes, it won’t recognize something as misspelled because it looks like another word. Therefore, it’s worthwhile to reread your essay, even if spellcheck says that nothing is wrong, in case you accidentally mistyped something” (Heaven). The coders also added such codes as documentation and attribution and formatting and style to the mechanics under LOCs. The coders again independently coded the participants’ feedback using a modified rubric. They then had another meeting in which they compared their codes and measured the inter-coder reliability by calculating the percentage of error categories the two coders agreed on. The agreement rate across all identified error categories was 93%. Any discrepancies were discussed in the meeting until a consensus was reached. The data were then transferred to Excel for further calculation and interpretation, and a figure and a table (see supplementary material for a detailed breakdown of teacher feedback in a table) were created for the presentation of the results.

The interview transcripts were analyzed to answer the second research question, which looks at the factors that might have influenced teacher feedback when using Grammarly, and the third research question, which examines teachers overall perceptions of Grammarly as a complement to their feedback. The audio recordings extracted from Zoom were transcribed in Trint (https://trint.com/) and checked for accuracy against the original recordings. Then, the transcripts were organized by an individual participant in Excel. Inductive coding that allows for themes to emerge from the data was used for analysis (Creswell, Reference Creswell2014). After reading each participant’s transcript reiteratively, the coders independently coded the data that appeared to address the aforementioned research questions. The coders highlighted the keywords, phrases, and sentences pertinent to the participants’ actions when using Grammarly to complement their feedback and perceptions of Grammarly. Those were then categorized into themes. For example, the theme “teachers use of Grammarly reports” focused on the participants’ actions taken when providing feedback to 10 essay drafts. The coders then had a meeting to compare their themes. In the meeting, they refined themes and chose illustrative quotes that represent the essence of each theme.

4. Findings

4.1 RQ1: What is the nature of L2 writing teachers’ feedback when they use Grammarly as a complement?

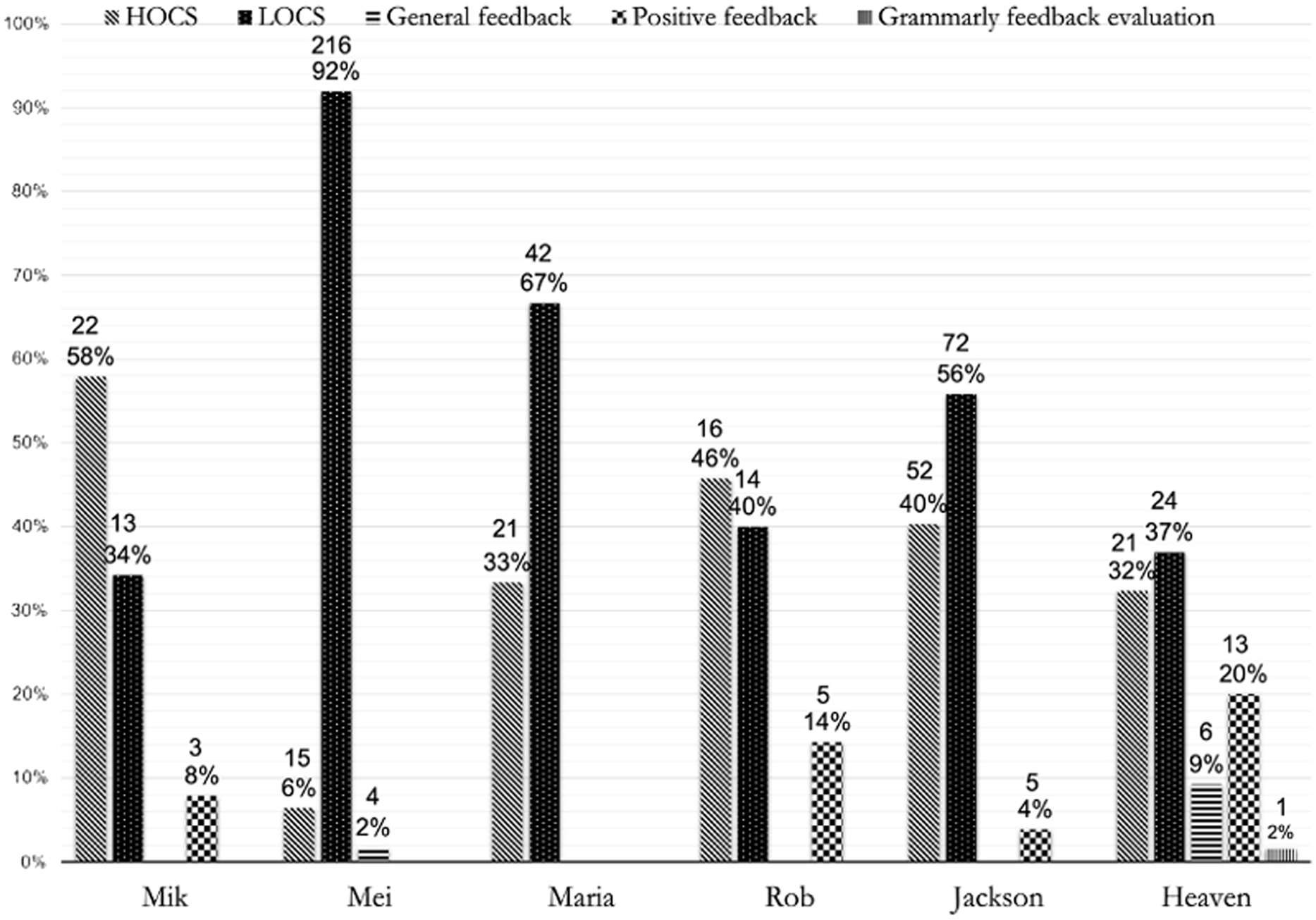

To answer the first research question, the participants’ feedback for 10 essays was analyzed. According to Figure 2, all six participants provided feedback on both HOCs and LOCs, despite having Grammarly feedback on LOCs as a complement. Additionally, the participants also felt the need to provide positive feedback, general feedback, and feedback that comments on Grammarly’s performance. Of the six participants, two participants, Mik and Rob, gave relatively more feedback on HOCs than on LOCs. They both also provided positive feedback. Mei, Maria, Jackson, and Heaven provided more feedback on LOCs than on HOCs. Of the four participants that gave more feedback on LOCs, Mei provided the highest number (92%). Heaven’s feedback among all the participants was the most diverse in terms of feedback type. A closer look at the participants’ feedback on LOCs shows that they devoted most of their feedback to sentence structure, word choice (including collocations and phrasing), spelling, punctuation, word form, overall quality of grammar, and documentation or attribution (see supplementary material for a detailed breakdown of teacher feedback).

Figure 2. L2 writing teachers’ feedback for 10 essays

4.2 RQ2: What factors (if any) influence teacher feedback when using Grammarly?

To answer the second research question, the participants’ interview data were analyzed. The analysis revealed three factors that might have influenced the participants’ feedback when they used Grammarly as a complement. These factors are the participants’ use of Grammarly reports, their attitude toward Grammarly feedback, as well as their feedback practice and personal beliefs about feedback and the L2 writing course.

4.2.1 Teachers’ use of Grammarly reports

The way the participants used Grammarly reports might have impacted their feedback. The interview data revealed that Mik, Maria, Rob, and Heaven consulted Grammarly reports before providing their own feedback. They reported that they first glanced at students’ essays, as Heaven said, to “get an idea of the content, argument, structure, and what problems might exist.” The participants then consulted Grammarly reports to check what errors Grammarly caught and what errors were left for them to address. In this regard, Maria said,

I went ahead and scanned to see what was happening there and just look at the mistakes that were already commented on by the software so that I would not be wasting my time repeating the same thing.

After consulting Grammarly reports, the participants provided their own feedback. Unlike the four participants, Jackson consulted Grammarly reports while providing his feedback. In the interview, he said that he put the paper on one half of his screen and the Grammarly report on the other half, which helped him make decisions regarding what errors to address. The following is his comment in this regard: “I had it open. I would glance at it. I didn’t really go off of it too much. I would just go OK! It addressed a lot of things here. I could focus on content. If it didn’t look at anything, I needed to also address a bit of form.” Mei, in contrast, looked at Grammarly reports after providing her own feedback. In the interview, she said she did not “want to be distracted or be biased by Grammarly feedback.” Therefore, she first provided her own feedback and then looked at Grammarly reports to see if Grammarly was able to catch the same errors she did. She then added, “many of the comments match mine, especially the local language errors.” Mei was the only teacher who did not use Grammarly to complement her feedback.

4.2.2 Teachers’ attitudes toward Grammarly feedback

When using Grammarly as a complement, the participants noted some disadvantages and advantages of automated feedback that affected their feedback provision. In terms of disadvantages, all participants noticed that Grammarly skipped a lot of errors. The following is what Mik said in this regard: “it’s not extensive, and it skips a lot of grammar mistakes.” To compensate for this limitation, the participants provided feedback on LOCs.

Some participants also noted that Grammarly caught only “basic” errors. For instance, Maria said, “I did notice the software didn’t get sentence structure errors. So I addressed those. I didn’t do anything really simple like subject-verb agreement or number. You know, those are really basic. Grammarly took care of those.” Since Grammarly took care of the “basic” errors, the participants’ feedback on LOCs predominantly focused on sentence structure, word form, word choice, and documentation and style.

All participants also noticed that Grammarly feedback was occasionally inaccurate. In this regard, Heaven said,

Sometimes Grammarly thinks that this word is the problem, but it’s actually this other word. It’s just confused, and Grammarly sometimes gets confused because you make a typo, but the typo looks like a word. So it doesn’t really know what to do with that. So it takes a human looking at it and evaluating those things that Grammarly is saying is an error.

Because Grammarly feedback was inaccurate at times, Heaven felt the need to warn students about this in her comments. Some participants also reported that Grammarly feedback was negative and can be discouraging and overwhelming as it catches every little error. To this end, Jackson said, “One student got sixty-four comments, which is incredibly discouraging. […]. I know if I got a paper back like that I would be discouraged.” Since Grammarly feedback was negative, the participants provided positive feedback.

As for advantages, the participants liked that Grammarly does part of their job by taking care of errors on LOCs, which frees their time to focus more on other issues in students’ papers. In this regard, Rob said, “It really reduces time and effort, and it can let me focus on higher-order issues.” Similarly, Maria said, “I just focused on higher-order features like writing quality and structure, and citations. So it made it easier for me. So I didn’t have to spend time making comments on grammar unless totally necessary.”

The participants also were satisfied with how detailed Grammarly feedback was. They liked that Grammarly underlines errors and provides metalinguistic explanation, which is very similar to what they do. Mik, for example, said,

It underlined where the mistake was and it kind of gave you a keyword for it. So you start learning some of the vocabularies like determiner or verb tense that a lot of L2 writing students might not even know to talk about grammar. So I thought that was really nice.

Finally, the participants reported that Grammarly feedback helped them see the most frequent errors of individual students and the class as a whole and what errors need to be addressed in the paper and in class. Regarding this, Heaven said, “I liked that it freed me up to just kind of focus on what I saw as broader trends, and I liked that looking at it made it easier for me to see what everybody in the class is having difficulty with.”

4.2.3 Teachers’ feedback practice and beliefs

Another factor that might have influenced the participants’ feedback when they used Grammarly as a complement is their feedback practice and beliefs about feedback and the L2 writing course. All the participants noted that students enrolled in the L2 writing course need both types of feedback because not only their writing but also their linguistic skills are developing. In this regard, Mei said: “they are freshmen and their language skills are developing and also their critical thinking skills are developing. That’s why I try to give both types of feedback.”

However, the participants reported that they tend to prioritize feedback on HOCs over LOCs because students often struggle with idea development and structure, which is more important than grammar. For instance, Maria said, “I mostly try to give comments on essay structure, paragraph structure, thesis statement, topic and conclusion sentences, and citations, especially on citation formatting.” Surprisingly, the quantitative findings contradict the above statements because the majority of the participants provided more feedback on LOCs than HOCs, according to Figure 2.

When asked if their feedback practice changed when using Grammarly to complement their feedback, all participants said that their feedback practice did not substantially change. What changed a bit is that Grammarly took care of the errors that teachers do not consider that much of a problem as there were more pressing issues in students’ writing that needed to be addressed, such as sentence structure. For example, Mik said, “whether or not I had the Grammarly report didn’t really change the approach that I have. The only thing that changed maybe if I saw something, a specific grammar error that was repeated over and over, I might have highlighted it, but I didn’t because Grammarly took care of that.” Similarly, Maria noted, “it’s impossible to give students an explanation for every little mistake. So, the software is really helpful in that respect.”

As for beliefs about the L2 writing course, the participants expressed concerns about the tool because it may not align with the course’s main goal, which is to teach students to find solutions for the identified errors on their own, while Grammarly not only indicates where the error is but also provides a correction, which students can automatically accept. This consequently may result in no learning as students may accept feedback blindly. For instance, the following is what Mik said in this regard:

Yes, you want to make sure that the essay they turn in is grammatically correct, but really what you’re trying to do is to teach them how to understand the grammar and how to eventually catch their own mistakes and not make them anymore. So, I think they’re slightly different objectives and it’s hard to make sure that you’re doing that with Grammarly because that’s really not the point, or at least not the long-term point of teaching L2 writing.

Heaven, Mik, Jackson, and Maria expressed their preference for other sources of feedback such as peer review and writing center consultations, which they believe are more effective. In this regard, Heaven said, “there are benefits to peer review that Grammarly is just not going to be able to capture because it’s not another student, it’s not another person who’s saying, here’s the mistake and here is how you can fix it.” All the participants also emphasized the importance of a human-to-human interaction when it comes to providing feedback, as students can ask questions if they do not understand feedback.

4.3 RQ3: What are L2 writing teachers’ overall perceptions of Grammarly as a complement to their feedback?

To answer the last research question, the participants’ interview data were scrutinized. The interview data revealed that while four participants were positive about Grammarly, two were pessimistic about using Grammarly in their L2 writing classroom.

Mei, Maria, Rob, and Heaven were favorable of Grammarly and reported that they would use it in their L2 writing course. For instance, Mei said, “I had a positive experience, and also it is a trend for teachers to use Grammarly. So I feel good about using Grammarly as support.” Similarly, Maria said, “Grammarly is already really widely used by native and non-native speakers of English. So I think there’s no reason to exclude it. And the more tools we can give to our students to improve their English, the better.” Rob stated that “automated writing feedback, augmented reality, […] artificial intelligence in the education sector are inevitable.” He believes that today “there is Grammarly, tomorrow there will be something else.” Therefore, he thinks that instead of avoiding this phenomenon, teachers should “reinforce the happening in a positive direction, which can support teaching.” Heaven noted that having a tool to take care of grammar issues can make them an “effective teacher” as they will be able to allocate more time and effort to global aspects of writing. They then added, “Grammarly is beneficial, and it is going to be something that I take into future classes.”

Contrary to the four participants, Mik and Jackson were pessimistic about Grammarly. Mik did not like that Grammarly skips a lot of L2 errors and that its automated nature may not increase any type of awareness of the error, so she feels hesitant to introduce it to her students. Mik also said, “I think that it would quicken our work and hopefully make us focus on other things in the writing that are more important in my opinion. But I just don’t think it’s there yet.” Jackson also did not favor that fact that Grammarly skips a lot of errors and “if there is supposed to be a division of labor, that division of labor maybe existed for 50% of the time” because he had to address form issues if they were not covered by Grammarly. More importantly, however, Jackson emphasized the fact that Grammarly feedback can be discouraging for students. In this regard, he said, “I think because of how many errors there are sometimes labeled, it’d be incredibly discouraging;” therefore, Jackson believes that Grammarly may not be good for ESL students.

5. Discussion

The quantitative findings of the study revealed that despite using Grammarly to complement their feedback, the participants provided feedback both on HOCs and LOCs, along with other types of feedback (e.g. positive feedback). This is in line with previous research that suggests that there is no division of labor, such as that AWE takes care of LOCs as it is more computationally adept at providing such feedback and a teacher takes care of HOCs (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Yu and Wang2020; Wilson & Czik, Reference Wilson and Czik2016). It seems that the premise of labor division between a teacher and AWE should be revisited, as teachers still feel the need to provide feedback on sentence-level issues regardless of AWE’s feedback. In this study, teachers felt the need to provide feedback on sentence structure, word choice, word form, spelling, punctuation, and documentation or attribution.

A closer look at the qualitative data revealed three factors that might have influenced the participants’ feedback when they used Grammarly as a complement. The first factor is the participants’ use of Grammarly reports. Five participants used Grammarly reports to complement their feedback and consulted the reports before or while providing their own feedback to see what errors Grammarly detected. This helped them make decisions about which errors to address in students’ writing. One participant, Mei, did not use Grammarly reports to complement her feedback. Instead, she first provided her own feedback, and then she looked at the reports to compare her feedback with Grammarly feedback. In the interview, she reported that she wanted to read students’ drafts for herself first to make her own judgments, because if she had looked at Grammarly reports first, that might have impacted what she thought of the paper. As a result, Mei ended up providing the highest number of feedback on LOCs among all the participants. Despite the fact that Mei did not use Grammarly to complement her feedback, she reported that she would use Grammarly in the future because Grammarly caught the same errors she did.

The second factor that might have influenced teacher feedback is the participants’ attitude toward Grammarly feedback. All the participants noticed that Grammarly skipped a lot of errors on LOCs; therefore, the participants also provided feedback on sentence-level issues. The participants also noticed that Grammarly caught, as they said, only “basic” errors, such as subject-verb agreement and possessive noun endings, which in the literature are defined as “treatable” errors. That is, an error “related to a linguistic structure that occurs in a rule-governed way” (Ferris, Reference Ferris2011: 36). A closer look at quantitative findings revealed that the majority of the participants’ feedback on LOCs focused on sentence structure, word form, and word choice, which are considered “untreatable” errors. That is, an error is “idiosyncratic, and the student will need to utilize acquired knowledge of the language to self-correct it” (Ferris, Reference Ferris2011: 36). Additionally, because Grammarly feedback was negative, which could be discouraging for students, the participants felt the need to provide positive feedback. Interestingly, the participants indicated that Grammarly liberated their time to focus more on HOCs. This seems to go against the quantitative findings of the study that revealed that only two participants provided more feedback on HOCs, while four participants provided more feedback on LOCs. One explanation could be the HOCs/LOCs dichotomy used in this study. The participants seemed to regard feedback on sentence structure, word choice, word form, and documentation or attribution (i.e. untreatable errors) as feedback on HOCs, while in this study, these error categories were coded as LOCs, which seems problematic and suggests that future studies should use the treatable/untreatable dichotomy (Ferris, Reference Ferris2011). Because Grammarly took care of treatable errors, and the participants took care of errors on global aspects of writing along with untreatable errors, which they regarded as feedback on HOCs, they had a sense that Grammarly freed them up to focus more on global aspects of writing. These findings partially support the claim made in the extant literature that AWE liberates teachers’ time to focus more on HOCs (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Yu and Wang2020; Wilson & Czik, Reference Wilson and Czik2016).

The last factor that might have impacted teacher feedback is the participants’ feedback practice and beliefs about feedback and the L2 writing course. All the participants reported that students taking the L2 writing course need feedback on both HOCs and LOCs because they are developing both writing and linguistics skills, but feedback on HOCs is often prioritized. Although this contradicts their actions, as seen in the quantitative findings, the participants truly believed Grammarly helped them focus more on HOCs. The participants also emphasized the fact that Grammarly may not align well with the L2 writing course objective as students may accept its feedback uncritically, which will not lead to true learning and students will not be able to resolve errors on their own. Therefore, they expressed their preference for other sources of feedback such as peer review and writing center feedback in addition to automated feedback because automated feedback is impersonal. Such concerns have also been raised in previous research (Ericsson, Reference Ericsson, Ericsson and Haswell2006; Herrington & Moran, Reference Herrington, Moran, Ericsson and Haswell2006).

As for overall perceptions of the tool, of the six participants, four were positive about Grammarly and reported they would use it in their L2 writing classroom. Although the participants were aware of Grammarly’s limitations, they were positive about it due to its numerous benefits, such as it provides detailed feedback, allows them to focus more on HOCs, and gives an overview of the most frequent errors in students’ writing. The participants also noted that tools like Grammarly are inevitable, and instead of resisting them, teachers should find ways for their effective use. However, two of the participants were skeptical about introducing Grammarly to their ESL students due to the fact that it does not detect all L2 errors and can be overwhelming because sometimes it provides too many suggestions. The findings suggest that when teachers experience using AWE, this allows them to recognize its strengths and weaknesses, which, in turn, can help them make educated decisions about the implementation of AWE in their classrooms (Cotos, Reference Cotos, Liontas and DelliCarpini2018; Li, Reference Li2021; Link et al., Reference Link, Dursan, Karakaya and Hegelheimer2014; Weigle Reference Weigle, Shermis and Burstein2013). Additionally, the findings support Chen and Cheng’s (Reference Chen and Cheng2008) claim that the limitations inherent in AWE can have a negative impact on teachers and could result in rejection of the idea of using the tool in the classroom.

6. Conclusion

The study explored postsecondary, L2 writing teachers’ use and perceptions of Grammarly as a complement to their feedback. By doing so, the study extended the extant literature on teachers’ use and perceptions of AWE in several ways. First, the study offers meaningful insights into how six postsecondary L2 writing teachers use Grammarly to complement their feedback, which has not been reported in previous research. Second, the study reveals the impact of Grammarly on teacher feedback and factors that might have influenced teacher feedback when Grammarly was used as a complement. Finally, the study provides implications for how to use Grammarly effectively as a complement to teacher feedback.

In light of the study findings, Grammarly has the potential to be used as a complement to teacher feedback but certainly should not be used to replace teacher feedback (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Yu and Wang2020; Weigle, Reference Weigle, Shermis and Burstein2013). Teachers should test the tool on their own to identify its limitations and affordances to make informed decisions about the use of such tools in their classrooms (Cotos, Reference Cotos, Liontas and DelliCarpini2018). Along with considering the limitations and affordances of the tool, teachers should also take into account their feedback beliefs and practices and also course objectives. If teachers decide to use Grammarly and similar tools in their classrooms, they should offer explicit training to their students on how to use these tools and respond to automated feedback (Koltovskaia, Reference Koltovskaia2020).

The following are the implications for Grammarly use as a complement to teacher feedback. Because of Grammarly’s limitation in skipping some of the L2 errors, teachers are advised to provide feedback on sentence-level issues too. Furthermore, teachers’ feedback on local aspects of writing should focus on untreatable errors because Grammarly is more computationally adept at detecting treatable errors. Research suggests that feedback on untreatable errors should be direct, as students find it difficult to resolve such errors on their own (Ferris, Reference Ferris2011). Additionally, because of the prescriptive nature of Grammarly feedback, students may not be aware of descriptive uses of grammar. Therefore, teachers are advised to provide lessons on prescriptive versus descriptive grammar. Since Grammarly feedback is negative, teachers should also provide positive feedback to avoid discouragement during the revision process. Finally, Grammarly detects errors comprehensively and may provide a lot of comments; therefore, its feedback could be overwhelming for students. Studies on written corrective feedback suggest that comprehensive feedback can indeed be overwhelming, confusing, and discouraging (Lee, Reference Lee2019; Sheen, Wright & Moldawa, Reference Sheen, Wright and Moldawa2009). Therefore, it is recommended for teachers to use Grammarly to determine the most frequent errors in individual students’ writing and provide focused feedback for each student.

While the findings of the study are informative for L2 writing teachers, some limitations should be acknowledged. The study focused on a hypothetical scenario and provided insight into teachers’ one-time use of Grammarly. Future studies should be conducted in the actual L2 writing classroom and should explore how teachers’ use and perceptions of AWE change over time. Considering Grammarly provides feedback primarily on treatable errors, future studies could consider the treatable/untreatable dichotomy and examine the impact of the automated feedback on treatable errors on students.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344022000179.

Ethical statement and competing interests

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by The Oklahoma State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (12/10/2020/ Application Number: IRB-20-547). The author declares no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

About the author

Svetlana Koltovskaia is an assistant professor of English at Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, OK, US. She holds a PhD in applied linguistics from Oklahoma State University. Her main research areas are computer-assisted language learning, L2 writing, and L2 assessment.

Author ORCID

Svetlana Koltovskaia, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3503-7295