In 1996, a new genre of Bobo masquerade emerged in the city of Bobo-Dioulasso, in south-western Burkina Faso. Artist Kuyméné André Sanou invented the first portrait mask when he carved a wooden headpiece to honour a recently deceased friend. Using a photograph as a model, he created a portrait of his friend in a stylized but highly naturalistic manner. Rather than a ‘thing from the bush’, as Bobo masks are said to be, Sanou's portrait mask clearly portrayed the visage of a specific and identifiable human being. His act of affection spurred a trend that, while deeply controversial, has become a wildly popular Bobo mask genre in the region.

Portrait masks demonstrate the investments and contributions of individuals to masquerade. In this article, I address two related issues: the agency of Kuyméné André Sanou, who introduced portrait masks, and the agency afforded to these naturalistic representations of specific individuals. The artist exploited the descriptive vocabulary of naturalism, making his subjects visually identifiable and quite distinct from other daytime masks, which take abstract forms. This visual analogue offers friends and family the opportunity to publicly celebrate a specific deceased loved one as an individual – an option not previously offered through Bobo masquerade. By redefining the mask as a portrait of the deceased whom it honours, ‘portrait masks’, as I have termed them, resonate with their diverse audiences and underscore the contributions of individuals to society. Yet the features that make André Sanou's portrait mask genre so popular – celebrating specific individuals who are visually identifiable by their physiognomic likeness – are the same ones that make the genre controversial.Footnote 1

Innovation and public controversy

Before entering the military, André Sanou learned to carve wood from his father, who fashioned doors, tool handles, mask headpieces and other objects. At the end of his service in the Algerian War (1959–62), he became a police officer in Burkina Faso (then Republic of Upper Volta) and carved in his free time. Demand for his artworks increased and once he retired from the police force he devoted himself to carving.

On the whole, present-day interlocutors agree that André Sanou carved the first portrait mask in honour of the head blacksmith in Tounouma district, Smaïla Sanou, an esteemed elder and close family friend.Footnote 2 Upon hearing of Smaïla's death, and in advance of the annual funeral celebration (sangaba) where masks dance, André Sanou ‘took the initiative’, as he put it, and made the mask as a surprise for the family and the community.Footnote 3 Using a photograph of Smaïla, the artist carved an anthropomorphic head bearing the visual features of the deceased. It showcases the individual physiognomy of the man in the photograph: the artist reproduced his head shape, penetrating gaze, small, protruding ears, flat forehead, closed mouth, closely cropped salt-and-pepper beard and moustache, and the striped knitted cap the man wore in the reference image.Footnote 4 André Sanou carved two ridged horns that emerge from the cap and arc backward like those of an antelope. In addition to the three-dimensional representation, the artist articulated each element chromatically. The skin is dark and lustrous, the facial hair speckled, each horizontal stripe on the cap rendered in a different colour, and the horns painted dark to contrast with the hat. As a friend of the deceased, a veteran, upstanding member of the community, and a renowned artist, André Sanou told the griots who play at Tounouma's annual sangaba that he wanted to bring out a new mask.Footnote 5 They agreed. According to the artist's account, when Smaïla Sanou's portrait mask toured Tounouma district, ‘no matter which compound it entered, everyone cried, because it was “him”!’Footnote 6 Other interlocutors present at its first appearance confirmed that the portrait mask was immediately recognizable as Smaïla Sanou.

André Sanou's sentimental tribute to Smaïla was a sensation and sparked a cottage industry. Immediately, the artist received commissions to make a portrait mask of someone's distinguished father, grandfather, mother, great-aunt, and so on.Footnote 7 He obliged with pleasure, adding headpieces of individualized human beings to his pre-existing repertoire of non-anthropomorphic mask headpieces, thrones, balaphones, religious objects, and various other commissioned artworks carved in wood. His studio has fulfilled paid commissions for headpieces in the likeness of specific individuals every year since the first one emerged.

Portrait masks also triggered a public controversy – one rooted in the fact that the new genre calls into question the regional definition of a mask. In the Bobo language, masks are ‘kibè-firè’, defined as ‘things that leave from the bush and come to the home/village’ – the bush being non-social, undomesticated space that is not the domain of humans.Footnote 8 But if portrait masks clearly image people, how can they be masks? Smaïla Sanou, for example, was clearly a human being, not a thing from the bush. Another term for a mask is chinyo. Common translations as ‘man's shadow’, or ‘man's double’, intimate that the mask is like a man – but not quite.Footnote 9 Thus, some degree of humanity, as reference or perhaps as origin, is very much at the core of the term's meaning. As the vast literature on masquerade demonstrates, the humanity inherent in masking is also one of its ‘secrets’, although many scholars admit that this ‘secret’ is anything but.Footnote 10 Older children and adults, whether or not they have the right to know that men dance masks, possess that knowledge; the pivotal concern is that they do not openly express that fact. We can more productively think of it as a ‘public secret’. Regarding portrait masks, the artist translated chinyo as ‘image of the deceased’, implying that the Bobo term for mask has a closer relationship to a visual representation of departed ancestors than other translations might suggest.Footnote 11

The majority of Bobo masks dance during the daytime at crucial moments in the life of a community, reputedly to honour and give form to the interconnectedness of the living and the dead.Footnote 12 Guy Le Moal (Reference Le Moal1980), French anthropologist and scholar of Bobo masquerade (who focuses on northern Bobo areas), claims that masks are conceived of as manifestations of the Bobo divinity Do and, through their abstracted animal forms, recall legends involving these animals and distant ancestors. A. T. Sanon (Reference Sanon1972: 181), cultural scholar and Archbishop Emeritus of Bobo-Dioulasso, has written, ‘masks being returned Ancestors [les Ancêtres revenant] among the living, are called the sons of DO’, thus equating masks with deceased relatives made visible, as so many living things are. However, in the same text, he also states that Bobo funerary masks ‘constantly evoke [Do’s] presence’, indicating that masks’ relationship to Do is symbolically expressive, not one of actual transformation. Sanon's latter point is much more consonant with my findings in and around the city.

While the scholarly literature on masquerade makes much of transformation (see Cole Reference Cole1985), my research has detected little pertinence for the issue among those currently involved in masquerade in and around Bobo-Dioulasso. Even if the theory of transformation has overshadowed the role of individual agency in scholarly studies of masquerade, my research colleagues, young and old, blacksmiths and the descendants of farmers, consistently volunteered information and commentary about specific individuals and their role in mask practice, particularly that of André Sanou. In fact, my interlocutors have never used the language of ‘manifestation’, nor have they given me the impression that daytime masks ‘manifest’, via transformation, any divinity. In our conversations and interviews, my colleagues have not referred to gods, spirits or ancestors with regard to the concept or actual being of masks. Rather, they have thus far suggested that their daytime masks are symbolically expressive of a shared heritage as well as powerful forces found in nature on which all life depends. Only certain trained men (blacksmiths, griots, elders, certain titleholders, and others initiated with the necessary knowledge), in concert with the assistance and support of women, are capable of bringing these forces into the village and city in the form of masks. I neither mean to suggest that all Bobo people believe this concept to be true nor that it is the prevailing way to understand masks. This is only one aspect of masking; other features of masquerade, such as interactive performance, entertainment, memory, heritage, innovation and propriety, are often more pressing in public practice and will be addressed below. Here, I would like to emphasize that, throughout my research in this area, interlocutors referred to these natural forces only in the most oblique or general manner as being in ‘the bush’, and that they explained that masks, which are extremely powerful (some more than others), issue from ‘the bush’ and come into the city under the auspices of those specialists mentioned above. If the term ‘manifestation’ is useful in this context, it would be as an acknowledgement that certain physical materials used to make masks (especially vines and leaves, which experience the least amount of intervention by humans in the process) are the purest tangible and visual expression of nature or ‘the bush’. Thus, those powerful forces that exist in the undomesticated ‘bush’ are made manifest via the materiality of the mask by those purportedly capable of mastering them and bringing them into domesticated social space.

Bobo daytime masks can be made from vines, leaves, bark, fibres or cloth. Le Moal (Reference Le Moal1980: 208) has argued that, while masks made wholly from leaves, bark or fibre are morphologically incomparable to living beings, fibre masks with woven or basketry-like heads are humanized, since they bear anthropomorphic facial traits. Fibre masks with wood heads ‘pursue even more clearly the search for models among living beings, mainly men and animals. The carved masks are often treated in a figural style; they possess a “physiognomy” and they have a face so evocative of resemblances that they strongly arouse the exercise of comparisons’ (ibid.). In that spirit, I elucidate the essential characteristics of a daytime mask genre that exhibits an acceptable degree of resemblance before returning to the specific ways in which André Sanou innovated standard contemporary practice.

In and around Bobo-Dioulasso today, masks with fibre bodies and carved wood headpieces exhibit the greatest diversity of form, colour and embellishment. Although there are dozens of mask genres in the region, each district or town has a few masks at the heart of its masquerade practice that belong to the entire community. I call these ‘core’ masks.Footnote 13 Their creation, presence and performance (both public and private) meet ceremonial requirements for the annual funeral celebration. They are the community's oldest genres and tend to dance before all other masks. Core masks belong to the community, are treated as the historical forms of the original masks, and conduct a pre-dance ceremony in which other masks do not participate. In Tounouma and Sya districts, the core masks are Gbama, Fougoula, kelepene and kimi.Footnote 14 The latter also comes in what colleagues commonly call ‘ambiance’ models.

Ambiance masks are commissioned by individual families to add character and luxury to the masquerade event.Footnote 15 Because they are not required, these masks lengthen the dance (otherwise, it would be too short), broaden its appeal by diversifying it, and involve more people (families, dancers, organizers) to make it more inclusive. Ambiance kimis, for example, can be commissioned to honour all the deceased ancestors in a family or to honour a single person. The deceased is not visually identified as being from a particular family nor is he identified by name. The wood headpiece could exhibit a trait or emblem of the deceased, but there are no other visual clues as to whom it honours. Kimi mask headpieces covered with angular yellow, black and white geometric forms are at the core of Tounouma and Sya's masquerade practices. Ambiance kimis can be any colour combination (other than that of the core ones) and bear a wide variety of designs. For example, the ambiance kimi in Figures 1a and 1b bears distinct facial features such as the trapezoidal face, perfectly round eyes, and notch for a mouth. It does not look like any known animal or human, yet it references a hornbill – made apparent by its sculptural beak. While the facial features of kimi masks are fairly standardized, their superstructures are diverse, ranging from abstract or geometric patterns (Figure 1a and 1b) to religious or popular imagery, and they can vary in size and colour scheme. Contemporary examples show immense variety, making each one unique.

Figure 1a Blue and pink kimi with a geometric superstructure (profile view). Note the beak that marks this as a bird. Sya district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2009.

Figure 1b Blue and pink kimi with a geometric superstructure (frontal view) greeting a crowd. Sya district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2009.

The self-referential example in Figure 2 bears representational imagery. Its superstructure is divided into two registers. The lower one frames a man (who is not identifiable) seated behind a kimi that appears to be greeting him.Footnote 16 The upper register depicts an abbreviated version of the nation's coat of arms: the national flag in the form of a shield over two crossed lances and flanked by two rearing white stallions.Footnote 17 Headpiece and frame are painted in geometric fields of red, green, yellow and blue, although they are dominated by the national colours (red, green and yellow). The imagery refers to graciousness, support for the mask tradition, and identification with a strong and contemporary national identity. This kind of specific, representational imagery allows viewers to contemplate, and hopefully emulate, desirable qualities ostensibly possessed by the elder(s) it honours, and, by extension, all of the deceased elders honoured at the sangaba.

Figure 2 Detail of a kimi with a superstructure bearing the national coat of arms. Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Sya district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2009.

If those powerful forces in nature that only certain men can exploit ordinarily have no visible form, masks such as these kimis give them shape at extraordinary moments. As Le Moal (Reference Le Moal1980: 208) has maintained: ‘The form of a mask is only the tangible medium for an abstract idea. All masks are the expression of a spiritual being who, by definition, has no precise form.’ He later continues:

It is a known fact that most African artists have sought in their works to ‘signify’ rather than resemble … Almost all the carved masks display a face whose features are more or less human in nature. We can confirm that the Bobo have never, through a mask, personified an individual, living or dead, whether a real or mythical ancestor or even a legendary hero. (Le Moal Reference Le Moal1980: 208)

Clearly, this is not currently the case. André Sanou's portrait mask genre conspicuously portrays the physiognomic likeness of deceased individuals. And, based on the principles of the regional masquerade practices enumerated above, this is improper. While masks with wood headpieces might articulate and display extremely generalized facial features, given the nature of masks, it would be inappropriate to actually image human form. And yet that is precisely what André Sanou has contributed to mask practice in the region. Depicting specific and identifiable humans is the crux of the controversy. The portrait mask genre contradicts the concept (underscored by its visual expression) that a mask is a ‘thing from the bush’, thus publicly undermining explanations of what constitutes a mask, as it is defined both in the early literature and by present-day interlocutors.

André Sanou's portrait mask genre is a new aesthetic strategy that strives to identify and honour specific individuals, rather than the collection of those who died during the past year. Visually, while kimi masks are immediately recognizable by the plank-like superstructure of the headpiece and abstract representation of a hornbill's curved beak on the lower section, portrait masks are more naturalistic than any other mask genre in the region. Fittingly, whoever commissions a portrait mask from André Sanou's studio typically brings a photograph for the artist to use as a model. This can be done before or after the honouree's death, although by all accounts the celebrant is prohibited from ever seeing his or her portrait mask headpiece, as doing so would reportedly hasten his or her death.Footnote 18 Today, André Sanou's son, Bowouro David Sanou, who has been at the helm of the atelier since André Sanou's retirement in 2009, replicates the photograph in a three-dimensional form.Footnote 19 Thus, the headpiece is custom-made, imaging the deceased specifically as he or she appears in the reference photograph.

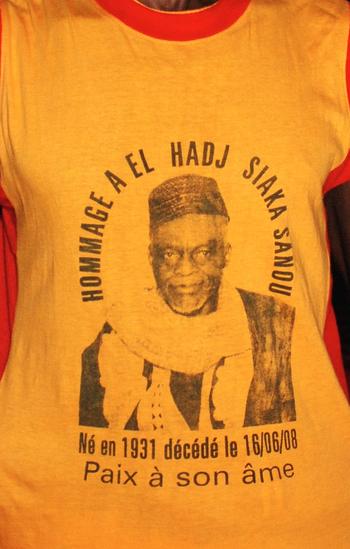

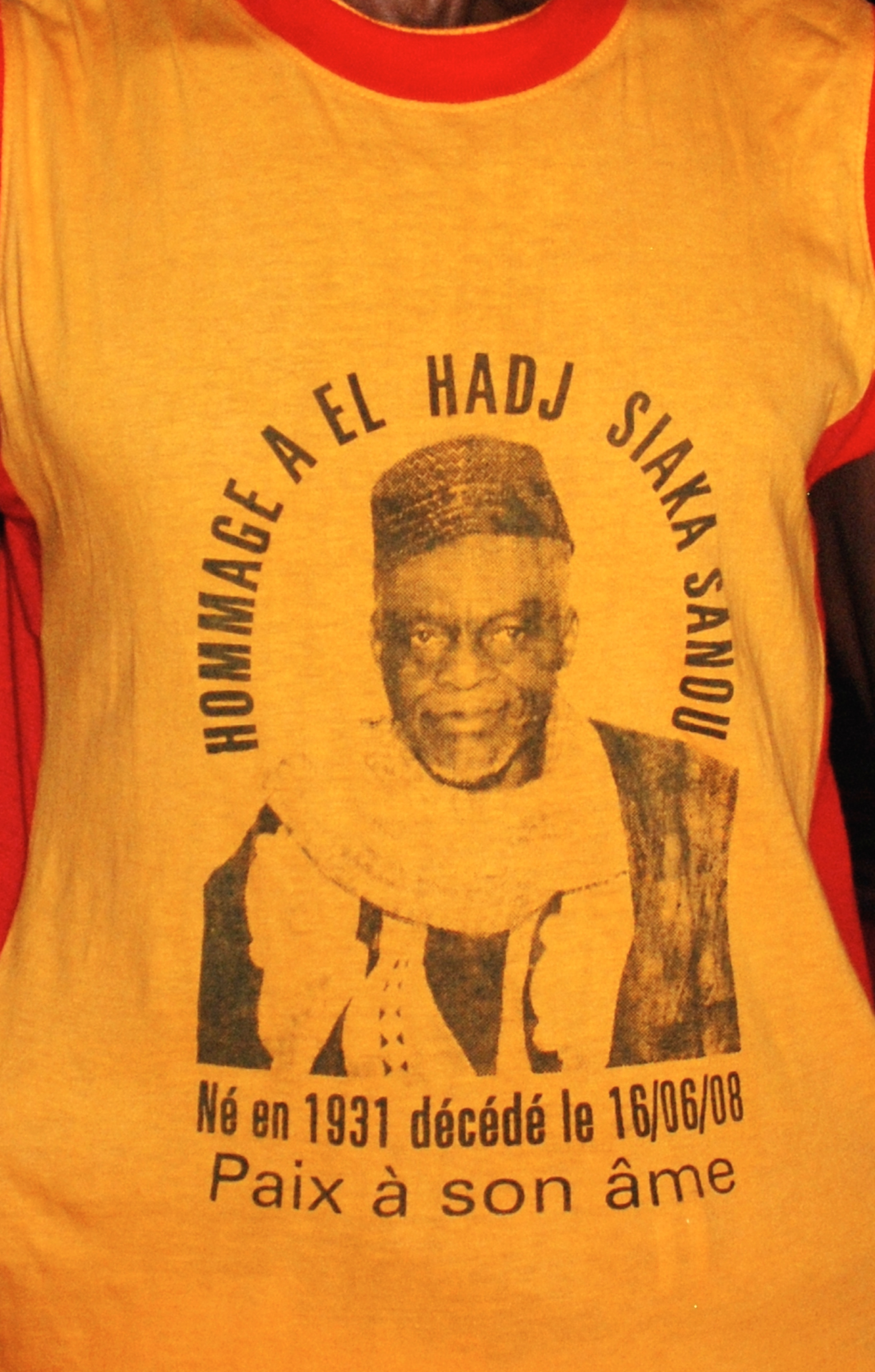

There is a small corpus of literature on African portraiture, although much of it concerns static sculptural or two-dimensional arts, rather than masquerade.Footnote 20 Art historian Jean Borgatti (Reference Borgatti1990: 38) has noted the tendency of African portraitists to idealize their subjects. As a genre, portrait masks exhibit a range of naturalism, from the ‘generalized’ to the ‘idiosyncratic’ (cf. Borgatti and Brilliant Reference Borgatti and Brilliant1990). The portrait mask of El Hadj Siaka Sanou illustrates well both ends of this spectrum in translating the reference image (Figure 3) into a wooden headpiece (Figure 4). The wood headpiece is certainly idealized, particularly in its smooth surface. In order to accommodate its function as a head covering, it is also a bit wider and more uniform than the subject's head shape. Yet it accurately captures enough of Siaka Sanou's particular physiognomy as shown in the photograph that it is clearly recognizable as him. The artist faithfully rendered the subject's prominently outlined orbital sockets and slight bags under his eyes. He depicted two vertical wrinkles between his eyebrows, and correctly flecked them with wispy white ‘hairs’. As far as can be discerned from the photograph, he accurately modelled the contours and lines of the subject's ears, his nose shape, down to the pointed tip, and pronounced laugh lines that emerge from just above the nostrils. The artist reproduced the form and tonal quality of the man's beard and moustache. He turned up the corners of the mouth to convey the deceased's sly smile in the photograph. The artist even replicated the slight tilt of his subject's cap – in dance, it lends a vivacious air to an otherwise immobile visage. André Sanou rendered his subject in an idealized light while accentuating its recognizability.Footnote 21

Figure 3 T-shirt bearing the reference image of El Hadj Siaka Sanou used for his portrait mask (model: Seydouman Sanou). Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2009.

Figure 4 Portrait mask of El Hadj Siaka Sanou dancing. Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Sya district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2009.

If the goal is to metaphorically bring back the deceased, then the artist suggests that the best way to accomplish this is to ‘see’ him. In one conversation about an anthropomorphic wood head he carved, the artist told me that it was ‘a photo in wood’. André Sanou takes responsibility only for carving wood, not masks. A mask is ‘something else’. Materially speaking, his assertion is perfectly consistent with the regional definition of a mask – a headpiece is not a mask.Footnote 22 Only a complete entity – head, body and any accessories (such as a whip or the staffs carried by masks referencing wild beasts) – is a mask. If a carving he makes becomes a mask, it is not through his doing, he says, but occurs through the intervention of others after it leaves his atelier.Footnote 23 He specified: ‘He is no more, but … there he is! It is like a revenant. After someone's death you have his photo [and] it's like you are still seeing the person.’Footnote 24 The artist often referred to portrait masks as revenants, not in the sense of ghosts or phantoms, but in the more literal sense of returners – those who have come back. I understand his usage of revenant to mean that, while ghosts and phantoms are apparitions, the portrait mask is a real, tangible entity that looks so precisely like the deceased that one would say it is that person, just as one would do when seeing a photograph of him or her.

Regarding representation, Margaret Thompson Drewal (Reference Drewal1990: 43) has asserted that ‘it could be argued that the primary function of a representation is to construct what reality is, not the other way around. In this sense, the portrait is not a mere reflection of reality, but a participant in its creation.’ She offers the example of placing a painted portrait depicting the likeness of a deceased man in the same context as an Egungun, which is ‘a visual manifestation of the deceased's spirit that portrays an ordinarily undisclosed reality’. In that instance, ‘the entire configuration in performance is a portrait. Thus the portrait, as well as its meaning, is situational’ (Drewal Reference Drewal1990: 46). Public and private display of portraits of deceased individuals, such as photographs, is perfectly acceptable in and around Bobo-Dioulasso. It is only when that physiognomic likeness of a deceased person takes the form of an animated mask that controversy over impropriety arises, precisely because its naturalism challenges a reality allegedly undergirded by the public secret of masquerade. The visual likeness of a deceased person animated – and by this I mean very much alive – as a mask, in a context in which masks are the purported physical form of ordinarily unseen forces, creates ‘two distinct dimensions of the forefather represented simultaneously and set into a dialogical relationship’ (ibid.: 46). And that relationship is incongruous. Those two ‘dimensions’ of the same individual simply cannot coexist within a single entity if each is to remain conceptually intact. If, as Drewal has pointed out, representation puts reality at issue, André Sanou's portrait masks create a reality that is undeniably problematized, not simply by the fact of representation, but by the naturalism inherent in the genre: that is, the deceased cannot be both an expression of unseen forces (mask) and a visually recognizable individual (headpiece).

Bobo masks historically do not have the faces of specific people; they should not look like one's father, grandmother, or any particular person. For this reason, since their inception, portrait masks have aroused debate about the (im)propriety of naturalistic representation in Bobo masquerade. Blaise Sanou, a member of the blacksmith family in Tounouma district that manages masquerades, current leader of Houet Province's hunters’ association, close friend of André Sanou and vocal critic of the artist's portrait mask genre, pointed out that a mask can be ‘anything but a man’.Footnote 25 ‘A mask has a strange face, but one doesn't know what a revenant looks like. [The portrait mask] is abnormal … I mean, can you explain what the face of a revenant looks like? I am against this; [André] is not working within the tradition.’Footnote 26 His complaint highlights not that ‘the tradition’ is vanishing or falling apart, but that the artist's work has exceeded the acceptable limits of ‘the tradition’. His statement also suggests that although André Sanou was effectively retired and his son David Sanou was carving the portrait mask headpieces coming out of his atelier, Blaise Sanou (and others) continued to hold André Sanou responsible for the genre. This remains true today, even after the artist's death. And Blaise Sanou is not alone in his condemnation of portrait masks.

In 2009, Tounouma's blacksmith family, the head of the ‘village’ (dougoutigi), the head of initiates and thus of masks (yelevo), and a committee of elders, in consultation with other prominent members of the community, decided that the portrait mask genre operated too far outside the parameters of the masquerade tradition for them to permit its performance under their supervision.Footnote 27 They collectively banned the genre from the district. Allied neighbouring Sya district followed suit.Footnote 28 As one of Sya's lead griots, Seydouman Sanou, put it: ‘All masks that resemble a man are prohibited here.’Footnote 29 The interim dougoutigi, Maxime Sanou, in consultation with other district leaders, enacted the ban shortly after he accepted the position.Footnote 30 In other nearby districts and villages, such as Dogona and Nasso, portrait masks remain controversial, but continue to dance to ebullient crowds. There, the lack of propriety associated with portrait masks is outweighed by their popularity with audiences. In still others, such as Kuinima and Pala, the portrait mask genre never caught on, in some cases because it did not suit the local aesthetic, or because officials and/or potential clients did not appreciate its naturalistic resemblance to human beings.Footnote 31 There may well be more reasons to eschew portrait masks, but these were the ones colleagues presented.

Portrait masks’ verisimilitude to individual human beings was the basis for banning them in Sya district. Every one of my interlocutors’ first criticism of the portrait mask genre was its representative nature, whether they framed this as the reason why it is problematic or why it is banned in Sya and Tounouma districts. All other objections to the genre were offered intermittently and without consensus. A lack of authority, innovation, profiteering and collapsing hierarchies are secondary to the fact that the controversy is based on the very thing audiences adore about André Sanou's portrait masks: they force recognition of the animated individual they depict. Their naturalism can be viewed as challenging the deceased's change in status when he passed from this world to the next – that he became an ancestor and is no longer human.Footnote 32 This is not to suggest that audiences are duped into thinking the deceased is not deceased. While portrait masks do not actually negate the change in the deceased's status, through naturalistic and animated representation of a specific deceased individual, they highlight that very impossibility. Their likeness to deceased individuals begs questions such as: if this entity (the portrait mask) is not the deceased individual (who has passed on so clearly cannot physically be here) even though it looks like him, how is it moving? Why does it look like him? How can a mask – a thing from the bush – look like a specific man? These are questions not raised by kimis, or by any other mask genre, since they do not naturalistically represent any known being. There is no significant incongruity between those entities as ‘things from the bush’ and what they look like. While audiences know that men dance masks and so masks are not actually mysterious, non-human entities from the bush, it is wholly inappropriate, dishonourable even, to emphasize that fact.Footnote 33 Yet, because they are naturalistic representations of individual humans, that is exactly what portrait masks do. Portrait masks highlight the ‘secret’ of masquerade, as Grégoire Sanou suggests below.

Debates over visual resemblance are couched within a larger, often public, discourse about a perceived lack of traditionality, evidenced by Blaise Sanou's comments above. And yet André Sanou created the portrait mask simply by modifying the wooden headpiece of pre-existing ambiance masks. Its body, media, colours, music and dance all conform to established aesthetic patterns. The body of bulky, dyed vegetal fibres, in particular, marks the being as a ‘thing from the bush’. This underscores the fact that it is often the head (its shape, aesthetic, representation, colour, pattern, etc.) that visually signals which mask is being danced, within a material genre (Le Moal Reference Le Moal1980: 163–242).Footnote 34 In comparing Figures 1b and 4, the visual similarities between the kimi and portrait mask become clear – particularly regarding the bodies, which share the same material, technique, shape and dynamism. It is their headpieces that distinguish them from one another. The kimi is not the only similar genre. Portrait masks share these features with almost all Bobo daytime masks comprised of fibre bodies and wooden headpieces, including kelepene, tu, nyaga, Flèdalo, Bobodalo and others.Footnote 35

Not only do many other daytime masks bear a body type similar to portrait masks, but also such a mass of vegetal fibres does not correspond to any standard human apparel. André Sanou was explicit about this issue:

A mask is a mask. But this, now, this here [the carved wooden headpiece] is the head of someone. This is the photo of someone that one sculpted. And in order to remember him during the funeral [celebrations], one turned it into a mask, because there is a different style of dress. There you go. Without the dress, the relatives, all those who know this old man, upon seeing him, well, there's the old guy! … It's during the funeral that you will see the clothing is not the same [as the person in the photo].Footnote 36

By expanding the existing visual vocabulary of the headpiece, but respecting the mask's essential form, medium and performance, portrait masks resonate with their diverse audiences and elicit their affection in ways not present with other masks. Portrait masks do not supersede older mask forms; they have made their way into some regional masquerade practices, although their status ranges from acclaimed to problematic.Footnote 37

In a larger discussion about the African portrait images in the exhibition ‘Likeness and Beyond’, Borgatti (Reference Borgatti1990: 39) has written that ‘they are appropriate “relational models” … and that they serve the same purposes in their own cultures as more representational images do in Western culture’. Conversely, the portrait mask genre is neither conventional nor uniformly accepted. Despite its popularity, and because many consider portrait masks inappropriate relational models, the genre is still being negotiated in and around Bobo-Dioulasso. Rather than a stable feature of ‘culture’ ostensibly agreed upon long ago, such as kimi masks, portrait masks are a contentious recent innovation whose inclusion in local practices is, in fact, precarious.

From the concept of a mask, to the role of portraiture, to naturalism and the public controversy it has sparked, there are clearly many entangled issues at work in André Sanou's portrait mask genre. The remainder of this article investigates and analyses various factors contributing to the public debate over portrait masks in order to elucidate the gravity of André Sanou's artistic innovation within Bobo masquerade and who has a stake in it, before considering the potential impact of recent events on the future of the genre.

Popularity: seeing and interacting

The controversy over this genre extends beyond the headpiece's verisimilitude to the ways in which masks and civilians (those people not masked) interact – and the two issues are intertwined.Footnote 38 If ‘[t]he very physicality of sculpture endows it with the capacity to fill an absence with an evocative presence’, as curator Alisa LaGamma (Reference LaGamma2011: 5) writes in Heroic Africans, masquerade heightens that presence through movement. Portrait masks’ full-bodied dynamism gives expression to the otherwise static headpiece.Footnote 39 As a form of remembrance, André Sanou's portrait masks resonate with their diverse audiences precisely because they image specific individuals in a naturalistic manner; when animated, and especially when viewed from a distance, the headpiece truly does ‘evoke’ a human being. No longer an image of someone, the dynamic entity is evidently a living person.

Like other Bobo masks, portrait masks dance, they tour their home districts, and they greet and interact with civilians. An informal, regional term, ‘civilian’ refers to any non-masked human and derives from the regional French term used to describe humans who are en civil (‘in plain clothes’), unlike masks. By pointing out that one is not masked, specifically in terms of clothing, ‘civilian’ obliquely points to the fact that masks are people covered in unusual ways. Yet portrait masks have a dramatically different relationship to civilians than other daytime mask genres. As the artist noted: ‘In principle, the mask is something strange and must be frightening.’Footnote 40 While portrait masks are not exactly human, as evidenced by the brightly coloured fibre body and immovable facial features, they are not at all frightening to a local audience.Footnote 41 Their faces look like people civilians know and love; they neither carry whips nor menace audiences, like so many other daytime masks.Footnote 42 Civilians characterize them as temperate and genial. Exchanges with portrait masks are more personalized, sometimes more moving, than with other masks precisely because the naturalism of the headpiece announces human presence. Rather than figures of legend or cultural heritage, like the kimi, which is visually abstract and mysterious by nature, portrait masks naturalistically depict people audiences might very well know. And there is joy in seeing a loved one return. In some instances, the dancer might start out the performance rather tentatively, even seeming unsteady and frail, and then becoming energetic, using broader steps and more forceful gestures as the dance gains momentum (Figure 4). Colleagues report that such a dance suggests that the deceased was physically fragile, an allusion to overall decline, but that he or she is now ‘OK’. This, of course, depends on the style of the dancer. Many portrait mask performances forgo any gestures of initial sluggishness or frailty in favour of a thoroughly exuberant dance. In both cases, the dancer ultimately portrays the deceased as healthy and happy. Animated portrait masks are a cheerful mode of remembrance that affects audiences positively. Seeing the portrait mask of a recently departed loved one can be a disarmingly emotional experience, in part because the mask is not an inert image, but a dynamic entity.

While a dancer animates that being, and is often the one who made the full body outfit, he generally does not receive official or public recognition as an individual.Footnote 43 Civilians publicly direct their support and affection to the deceased being honoured. Many reported that the naturalism and dynamism of portrait masks facilitate, even trigger, their memories of the deceased individual. Personal emblems or visual markers borne by the mask – such as a cane, pipe, sunglasses, favourite hat or unique facial scars – further evoke the individuality of the deceased. Given the funerary context of the event, for the civilians present, this easily becomes a remembrance of the deceased's resonant qualities. Thus, despite heated debates about naturalistic human representation in masquerade, when portrait masks arrive on the dance floor, crowds appear to greet them with markedly more zeal than for any other mask genre.

Portrait masks often capitalize on the deceased's notable attributes and affiliations, making them extremely relatable to civilians. In April 2008, the portrait mask of Bala Honorat Sanon – known as ‘Papa Bala’ – debuted in Bobo-Dioulasso's Sya district (Figure 5). Papa Bala was an esteemed elder in the district and the leader of Houet Province's hunters’ association. André Sanou had been a senior member of the same association and was its leader when Papa Bala's portrait mask danced.Footnote 44 As a close friend and colleague of the deceased, André Sanou not only carved Papa Bala's portrait mask, he also attended the funeral celebration where it first danced, together with other hunters’ association members and its band.Footnote 45 It is common for a massive entourage of relatives, friends and well-wishers to accompany a portrait mask onto the dance arena. Papa Bala's portrait mask entered the dance floor with an entourage so large it all but obscured him from the rest of the audience.Footnote 46 There were family members in commemorative ‘Papa Bala’ T-shirts, older women in the family, various other supporters, hunters’ association members (including André Sanou) and its band, this latter group decked out in the distinctive cotton tunics that mark their membership. The griots who animate daytime masks temporarily ceded their role to the hunters’ association musicians, who played different rhythms from those used for the other portrait masks out that day.Footnote 47 The portrait mask's entrance visually, physically and sonically marked Papa Bala as exceptional, particularly owing to his authority over the hunters’ association. Then, in an impressive move, André Sanou further dramatized Papa Bala's status and his own: the artist proceeded to manage the mask's entourage, instruct the band, and direct the portrait mask as it moved around the dance area greeting elder family members and other dignitaries.

Figure 5 Portrait mask of Papa Bala on the dance floor. Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Sya district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2008.

The entrance of any much-anticipated mask can be a disjointed process. It is not uncommon for many in the entourage to want to have a say in how things proceed, causing much discussion and contradictory instruction as the performance unfolds. Papa Bala's entrance was no different, except that it was clear who had the final say: the leader of Houet Province's hunters’ association, and creator of the portrait mask's headpiece, André Sanou. As several of Papa Bala's young, male family members, hunters’ association members and musicians in the group vied to direct the mask's greetings and ensure that each dignitary received his or her due, while also singing and swaying or dancing, André Sanou calmly gestured or spoke to the portrait mask, who obeyed. In a series of micro-performances, and at André’s Sanou behest, he hailed, bowed, waved and danced his greetings to officials and elders, who responded by waving, smiling, laughing, shouting greetings, or giving monetary gifts to an entourage or family member (Figure 6).Footnote 48 He even made his way through the audience to greet a distinguished elder in the family of the dougoutigi – by sitting on his lap.Footnote 49 The elder beamed gleefully in return. These were touching moments for participants and onlookers.

Figure 6 Portrait mask of Papa Bala waving a fly-whisk. André Sanou on the right. Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Sya district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2008.

This vignette demonstrates the interactive nature of masks in general, but more specifically the intimacy with which civilians experience portrait masks. It is not the acts as much as their results that matter. The mask's naturalistic representation of a known person allows such micro-performances to take on more personal, more affective meanings than if they were to involve a kimi or any other mask. Civilians interacted with Papa Bala's portrait mask in ways that manifested their joy at seeing ‘him’ alive and well again. This scenario also evidences the extent to which portrait masks refer back to the life of the deceased. By depicting specific deceased individuals, portrait masks encourage audiences to recall and connect with them on a personal level. The mask headpiece images a known human being whose personal history was very much intertwined with the histories and experiences of individuals throughout the district and the region – precisely those people who constitute the audience and entourage.

While Papa Bala's portrait mask was certainly the star, André Sanou also stood out as leader of the hunters’ association, inventor of portrait masks, and head of the studio that made Papa Bala's headpiece. And his particular relationship with Papa Bala came to the fore. Several friends and interlocutors commented positively after the dance about André Sanou leading the hunters’ association in the same breath with which they mentioned his friendship with Papa Bala and being moved by the sincerity of André’s Sanou interactions with the portrait mask. They intimated that kind and generous people publicly celebrate the greats who came up before or with them and that such admirable traits are desirable in leaders – bringing memories of Papa Bala into the current day.

Audiences recognized Papa Bala as a notable elder, patriarch, and leader of the hunters’ association. They also appreciated the many other, more personal, roles he played in their lives. Greetings and interactions with non-portrait masks, such as the kimi, evoke myths or legends deemed essential to local history and contemporary prosperity. The portrait mask genre lacks a specific mythical relationship to the ephemeral Bobo divinity Do or the bush (other than by virtue of being a mask). Portrait masks temporarily bring back specific individuals who, in mask form, evoke personal and public histories, demonstrate that they are well, and give their living friends and relatives an opportunity to rejoice in their momentary return.

Supporters even call the portrait mask by the name of the deceased whom it images – unthinkable for any other Bobo mask, as it emphasizes the humanity of what should be a thing from the bush.Footnote 50 They sing songs lauding the deceased's accomplishments and might publicly display his image alongside the animated mask. In short, they emphasize the individual, his successful life and the family line over how one might perceive his potential as a deceased ancestor. On the occasions in which several portrait masks enter the dance floor at the same time, it becomes a reunion of distinguished, departed elders who greet one another and even dance together. The emotional impact of seeing these revenants in each other's company again is unachievable by any other means, as audiences know that witnessing such a reunion is simply not possible. These interactions are the direct results of the mask headpiece's naturalism (recognizable as a particular human) as much as its movement, vitality and human-like behaviour.

Dissenters claim that portrait masks’ comportment and civilians’ behaviour towards them are overly familiar, embracing a sociability and agency uncommon in other daytime masks, which are gruffer and more menacing. At a mask dance in 2009, the portrait mask of Ali Kolo Sanou charged up to a young man on the dance floor, probably a relative of the deceased diamanatigi, but stopped short at the last second.Footnote 51 This micro-performance called attention to their kinship and was both exhilarating (what would the portrait mask do to the young man?!) and tender (recalling ties that bind). However, such interactions are equally common among non-portrait masks and civilians. At any daytime mask dance, it is probable that a mask, such as a kimi, will run up to or take by surprise some civilian on or near the dance floor – but one never knows when it will happen. As with André Sanou and Papa Bala, the difference here is that because the portrait mask headpiece looks like a particular human being, the interaction appears to occur between two individuals rather than between a mask and a person. Viewers recall and make connections between the personalities and their particular histories. Tellingly, complaints claim that portrait masks are ‘not good’, implying that they are unethical, and that André Sanou should not make them because they are ruining venerable Bobo mask customs by subverting the mask as a ‘thing from the bush’. Grégoire Sanou, currently a supervisor of masks in Sya, explained that although he likes André Sanou's portrait masks, he accepts the ban. He specified that since a mask is something from the bush, when it is presented as a human being, it is like ‘selling the secret’ of masks or outwardly ‘exposing the secret’.Footnote 52 Yet when portrait masks emerge, civilians often give them a much more enthusiastic greeting than any other mask genre in the city. So while some may complain that portrait masks ruin historical ideas of what constitutes a mask – and, by extension, the mask tradition – they remain very popular even in the face of Tounouma and Sya's bans and the visual impropriety involved.Footnote 53

Although André Sanou's new genre reconceives masquerade as a representational medium, as noted above, the issues of transformation and manifestation are also noticeably absent from the discourse surrounding portrait masks, perhaps because it is a new mask genre whose origins are not mythical but personal. Given the public patronage, portrait masks’ secular origins and human visages, civilians’ personalized engagement with the masks and the artist's celebrity, the suggestion that a recently deceased person has actually, physically manifested in public as a portrait mask simply has not come up. No dancer claimed to ‘become’ the spirit of the deceased relative whose portrait mask he danced (compare Cole Reference Cole1985). Those rare dancers who would discuss the matter emphasized dancing well, honouring the deceased, and perhaps adding a little of their own flair to the performances. Grégoire Sanou, who for many years has been assigning dancers to daytime masks in Sya, emphasized selecting someone who will outperform all other possible dancers. He endeavours to choose a dancer who will train and practise well in advance, knows the steps and music, and perhaps has shown a talent for the mask to which he is assigned. Grégoire Sanou never mentioned or even implied the possibility of transformation.Footnote 54 André Sanou, several dancers and civilian enthusiasts all stated that portrait masks allow us to have the enjoyable and touching experience of ‘seeing’ the deceased active and healthy. We all know the deceased has passed away, but the naturalistic headpiece and animated body allow us to acknowledge that the portrait mask ‘is’ the deceased in the same way one would say the subject of a photograph ‘is’ that person.Footnote 55

André Sanou's role and controversy revisited

Given the extreme popularity of bearing witness to the return of a deceased loved one, some criticisms of the portrait mask genre skirt the issue of naturalism. They point out that André Sanou does not have a position of authority over masks, that he has made a blatant and single-handed departure from the principles of Bobo mask making, that he has profited from it, and that portrait masks have come to undermine the social hierarchy of funeral celebrations. While each rationalization against portrait masks has a kernel of truth, none is wholly accurate.

André Sanou created portrait masks to honour a deceased friend. He continued to make portrait masks to fulfil commissions. His success increased his stature as an artist, and he became successful by operating outside the normal channels. Historically, Bobo masks were made exclusively by members of a guild devoted to the task and approved by the committee of elder men who oversaw all aspects of the masquerades. In addition to the fact that blacksmiths exercise some authority over masks in Tounouma district (see above), Le Moal (Reference Le Moal1980) suggests that blacksmiths are the ‘traditional’ carvers of wooden mask headpieces. The artist never belonged to the guild, was not a blacksmith, and had no decision-making authority regarding masks in or around the city. André Sanou's position related more closely to a point made by Kalo Antoine Millogo (Reference Millogo1990: 30) that there is no particular category of person for whom woodcarving is reserved. Those people who emerge as particularly skilled carvers can attract paid commissions for their work. The artist rightfully boasted that, once organizers in various districts and villages recognized his expertise as a carver, they made an exception.Footnote 56 Today, many masquerade organizing committees commission their masks from his studio, thereby inviting his (and his son David's) aesthetic and forms into their masquerade practices. Such an exception is not new; Bobo masquerade's adaptability and openness to innovation are well documented. Le Moal (Reference Le Moal1980: 298–309) recorded various modes of acquiring new mask genres, the primary ones being purchase, exchange, concession, gift and theft. Anselme Titianma Sanon (Reference Sanon1986: 9–10) adds borrowing and imitation to the list and specifies that when initiates attend mask dances in villages other than their own, they are sure to make comparisons and learn alternative possibilities for masquerade in order ‘to enrich the village's heritage’.

Critics also complain that this permissive attitude towards new mask forms allowed the artist to carve portrait mask headpieces only for profit, imparting a mercenary flavour to a practice ideally rooted in communal good. Blaise Sanou said that André Sanou ‘does not work within the tradition’ and compared commissioning a portrait mask from him to hiring a carpenter. He makes work to the client's specifications in exchange for money.Footnote 57 Abbé Joanny Sanon, priest, musician, cultural critic and active patron of Bobo arts, has been at the more critical end of the spectrum. In a conversation in which he unreservedly condemned André Sanou's portrait masks, Abbé Joanny Sanon also noted that some nearby villages, such as Bama, do not purchase or commission masks from ‘outside’ their communities. He claimed that audiences would easily identify the foreign visual aesthetic of a mask headpiece purchased from elsewhere, and suggested that leaders want their masks to maintain a ‘Bama’ visual identity.Footnote 58 However, given its long history and wide distribution, mask making for hire is not the crucial problem, as it is public knowledge that the artist worked on commission and individuals make their own choices about whether or not to purchase the work. No one condemned the fact that André Sanou created and sold other kinds of headpieces, such as kimis, and charged for his work, as always.Footnote 59 The artist's much admired mask headpieces have been bought and sold for decades according to the tastes of each patron or community without much contention about the artist's status or right to profit.

Many interlocutors who were outspoken in their opposition to portrait masks also praised André Sanou for his carving talents and delighted in being present when his artworks danced.Footnote 60 Blaise Sanou (who actively supported Tounouma's ban) recounted the pleasure, joy and awe expressed by viewers (himself included) who witnessed the first portrait mask in Tounouma. And gesturing to a photograph of the female portrait mask of Koromanteré Germaine Sanou, which emerged in Tounouma in 2000, Blaise Sanou declared: ‘This succeeds in the true sense of the word.’Footnote 61 Grégoire Sanou, who commented that portrait masks expose the secret of masking, also asserted more than once that the headpieces coming out of André Sanou's atelier were and are far superior to those made by any other artist in the region and so justify their relatively high price.Footnote 62 When viewing photographs of portrait masks in Nasso village, Nouho Sanou, one of the supervisors on the dance floor in Kuinima district (which does not support portrait masks), said: ‘This does not even resemble a mask. It is not right. It is not right … It is no longer a mask. Now it's, it's theatre now. That's it, it's theatre … All you have to do is see [the portrait mask] and – it's him [the deceased]! You see? It isn't right.’ His comments emphasize that the controversy is not over the fear that the portrait mask genre will destroy the ‘secret’ of masquerade (since most people already know that men dance masks), but that exposing or highlighting this secret is not the proper way to do masquerade. Not five minutes later, while still discussing portrait masks in Nasso, Nouho Sanou exclaimed: ‘He is a good sculptor, K. André. He is a good sculptor. Wooh! Really, he is a good sculptor.’Footnote 63 These interlocutors (and others) clearly compartmentalize the joy they get from seeing portrait masks of deceased loved ones and the apparent impropriety of their presentation.

Another complaint about the genre centres on status. When portrait masks first gained popularity, they honoured only titled leaders (the head of griots, blacksmiths or the hunters’ association, the dougoutigi or diamanatigi, and so on). Eventually, in Sya at least, it became ‘exaggerated’ and everyone with money ‘made one for their father’.Footnote 64 People commissioned them to encourage the children and other relatives of the deceased to fill his (or her) shoes and participate in communal ceremonies and work actively for the good of the community.Footnote 65 This resembles LaGamma's (Reference LaGamma2011: 9) description of how early Romans were meant to consider funerary portrait busts: ‘contemplation of commemorative images was intended to inspire viewers to emulate esteemed ancestors’. Cultivating the best qualities of one's ancestors is surely desirable, but having the means to do so must not be the only condition to commission and dance a mask. Grégoire Sanou suggested that, among other issues, organizers feared the popularity of portrait masks was too great; eventually, they would overshadow the older, more historically and ritually important masks.Footnote 66 However, the artist alone was not responsible for determining whom portrait masks honour or if they may dance. André Sanou made portrait masks on commission based on patrons’ requests. Organizers of the sangaba decide which masks may dance. Griots, blacksmiths, dancers and other initiates work to execute the event. Certainly, the organizing committees in Sya and Tounouma could limit portrait masks so that they honoured only deceased individuals who held titled positions. Instead, they banned the genre.

Portrait masks are a clever way to honour the tradition of masquerade as the means to evoke forces, including deceased ancestors, whose origins are not seen but whose effects are, while sidestepping any involvement with the esoteric aspects of the practice. The portrait mask genre is a secular, contemporary innovation.Footnote 67 However, for some, it is ideologically and visually inconsistent with the professed principles of masquerade in the region. With portrait masks, what we see before our eyes simply does not conform to interpretations of masks as evocations of a divinity (Do) or other unseen forces. Dancing any mask honours deceased ancestors since they made and danced masks first, before handing the practice down to the current generations. Dancing masks today honours the continuation of their legacy. Portrait masks contribute to this process, as they identify and honour the most recent and distinguished additions to the realm of deceased ancestors.

André Sanou as a deceased ancestor

Kuyméné André Sanou died of liver cancer on 24 January 2015, after several months of treatment in Burkina Faso and France. As the foremost artist of regional masquerade headpieces, president of the Fédération des Chasseurs Traditionnels Dozos de l'Ouest du Burkina, and a ‘son of the village’, many people expected the artist's family to honour their recently deceased patriarch by bringing out at least one new mask at Tounouma's sangaba the following spring. To that end, Blaise Sanou told David Sanou to make whatever he wanted for the occasion.Footnote 68 David Sanou created two mask headpieces honouring his father, which danced in Tounouma's large public funeral celebration on 3 May 2015. Both were ostensibly kimi headpieces.

The first to dance was a conventional kimi (Figure 7a), with its small, round eyes, barely there mouth, protruding curved beak, and geometric forms in alternating red, yellow, black and white covering the entire face and head. To this, David Sanou added representations of cowry shells on the head and cheeks – where they seemed to fall like tears from the eyes highlighted in white. Its head bore very small, ringed horns and vertical, slightly pointed ears, like those of an antelope or ram. As is common with kimi headpieces, David Sanou also made dozens of small incisions on the top of the head to represent the coat of a wild animal (Figure 7b). The superstructure had two registers. The lower one held the representation of an antelope. The upper one had an image of the family ‘fetish’, as David Sanou called it: a consecrated altar located in the family courtyard in Tounouma that acts as the focus of prayers, libations and sacrifices intended to benefit the family. Overall, the first kimi speaks to the loss of a great man (tears), his role as a hunter (antelope), and his transition into a deceased ancestor (altar). Its anatomy and iconography plainly conform to the kimi mask genre.

Figure 7a First kimi carved by David Sanou in honour of André Sanou (three-quarter view). Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Tounouma district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2015.

Figure 7b First kimi (unfinished) carved by David Sanou in honour of André Sanou (profile view). Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Tounouma district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2015.

The second headpiece followed the basic form of a kimi (Figures 8a and 8b) with its round eyes, curved beak, and superstructure emphasizing the object's vertical axis. Geometric forms alternating in black and yellow with white accents graced the sides of its head and extended upwards onto the superstructure, which was divided into three registers, each framing a hunting-related image: a hippo at the bottom, an elephant in the middle, and a rifle at the top.Footnote 69 However, this second kimi was also exceptional in several ways. It lacked the horns present on the first kimi. Other than the angular patterns on the sides, the head was painted in a flat shade of caramel – a far cry from the bold colours and all-over pattern associated with kimi masks, and quite close to a skin tone. Above the patterning on the sides, David Sanou positioned C-shaped forms that read as ears. The artist added a series of small yellow, black and white squares that framed the front of the visage and bordered the patterning on its sides. On either side of the beak and above the eyes, he incised short, vertical lines and painted them to appear as eyebrows. While small and round (adhering to ‘classic’ kimi style), the eyes were outlined in white and released a stream of cowry-shaped tears reaching down to the figure's mouth. The infranasal depression and mouth were larger, more three-dimensional, protruding much farther into space than on the previous kimi and with a larger gap between the lips – as if the figure were ready to speak. The face was crowned by a dark brown skullcap emblazoned with colourful images of leather pouches, animal claws, and horns set into leather housings – powerful objects that protect its wearer and announce the wearer's status as a formidable hunter. In iconographic terms, with its many allusions to powerful animals and the means of felling them (the rifle), the headpiece celebrates the skilled hunter André Sanou.

Figure 8a Second kimi carved by David Sanou in honour of André Sanou (frontal view). Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Tounouma district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2015.

Figure 8b Second kimi carved by David Sanou in honour of André Sanou (profile view). Mask headpiece from the atelier of André Sanou. Tounouma district, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2015.

As an animated visual object, David Sanou's second headpiece for his father displays elements of the portrait mask genre and the kimi genre. Even the fibres comprising its body were dark reddish-brown and recall the tunics often worn by hunters in south-western Burkina Faso. While the facial features are abstracted and less modelled than with portrait masks, when viewed frontally (that is, when the figure looks back at the viewer) and in movement, one sees the penetrating eyes framed by eyebrows, open mouth and ear-like forms, as well as the clothing (hat) and skin tone of a human being, albeit a very strange-looking one. Yet the object can technically be called a kimi because it bears the kimi’s curved beak, simplified facial features, correctly oriented superstructure, and bulky fibre body.Footnote 70

Being well aware that portrait masks are prohibited in Tounouma, David Sanou was faced with the problem of how to honour his father's legacy – as both a respected hunter and an innovative artist. He chose to compromise by moving away from ‘representational portraiture’ based on his father's physical likeness and towards ‘emblematic portraiture’ in which he emphasized his father's status and achievements.Footnote 71 He obeyed the letter of the law (the ban), if not its spirit. David Sanou's creation is not so naturalistic and so modelled as to confound humanity with masquerade. It strongly resembles a kimi. But given the funerary context mere months after André Sanou's death, in his natal district of Tounouma, with the mask's various hunters’ emblems, and in conjunction with even abstracted human features on the headpiece (as the artist is credited with inventing), one could ‘decipher’ the mask as André Sanou.Footnote 72

As he was putting the final touches to the two headpieces, David Sanou expressed hope and trepidation about whether the second kimi would be permitted to dance.Footnote 73 Ultimately, both of David's Sanou masks honouring his father performed at Tounouma's sangaba. While I have not confirmed this with the organizers, I suspect that they approved the second kimi because, even though it had some human features, it lacked the modelled naturalism of the portrait mask genre. It remains to be seen whether or not David Sanou's compromise will catch on as a means to partially circumvent the portrait mask ban or if organizers made an exception here, owing to André Sanou's many accomplishments and contributions to the community.Footnote 74

What remains clear is that portrait masks from André Sanou's atelier are about more than portraiture. Close attention to the hotly debated issue of naturalism surrounding the new genre offers a dramatic example of ‘how individuals shape the creation, execution, [and] reception of masquerades’ (Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2014). It highlights André Sanou's agency as the originator and driving force behind this new visual strategy. It emphasizes audience subjectivities, both in favour of and in opposition to the new genre, and particularly civilians’ active engagement with portrait masks. Even the deceased who are imaged in the headpieces get the respect they deserve, since dynamic portrait masks prompt recollections of their accomplishments as living men and women.

As a genre, portrait masks underscore the complex nature of masquerade and how it is understood, both in Bobo-Dioulasso and elsewhere. The portrait mask controversy illustrates well the messy business of reconciling creative differences with societal values among individual artists, patrons, organizers, performers and audience members who can serve as the gatekeepers of cultural institutions – the characteristics of which are at least somewhat negotiable. While André Sanou is credited with inventing and popularizing the portrait mask genre, it should now be clear that no single person bears responsibility for its reputation or status in any given community. Many involved constituencies make deliberate, informed decisions about creating, interacting with and judging portrait masks. Individuals make these decisions in light of the masks’ naturalism, particularly in comparison to other contemporary daytime masks. And their actions shape the mask genre and each masquerade event. Humanity and individual agency are essential to, and celebrated components of, portrait masquerade.

Acknowledgements

This article draws on interviews and informal conversations with colleagues in and around Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso from 2006 to 2016, where I documented fifty-three daytime mask dances, ten of which included portrait masks. I am grateful for field research support from the UNCC College of Arts + Architecture and Department of Art and Art History (April–June 2016 and April–May 2015), the Penn Humanities Forum (May–June 2014), and the UCLA Department of Art History (March–June 2009, November 2007–June 2008, and July 2006). I extend my gratitude to colleagues in Burkina Faso, France, and the United States, too numerous to list here, who generously provided their time, expertise and archival materials during the development of this article. Errors of fact or interpretation are entirely my own. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author's.