Following a relatively steady 16-year period of economic growth, the UK experienced a major economic downturn in 2008 leading to the worst recession seen in 60 years.Reference Norström and Grönqvist1 This led to negative changes in income, education, health, and the housing and labour market.2,Reference Reeves, Basu, McKee, Marmot and Stuckler3 Several studies have investigated the link between economic conditions and suicide. A number of factors might act at an individual and societal level such as increasing debt, home repossession, job insecurity and unemployment. There is international evidence of a significant association between rapid short-term economic downturn and suicide deaths, with men particularly affected and the effects in women being smaller or none.Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee4–Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Scott-Samuel, McKee and Stuckler8 As one of the most vulnerable groups in society, some have suggested that the effect of economic recession might be even more marked in those who are mentally ill or those already at high risk of suicide.Reference Karanikolos, Mladovsky, Cylus, Thomson, Basu and Stuckler9,Reference Coope, Gunnell, Hollingworth, Hawton, Kapur and Fearn10 Previous research has shown increasing trends in mental health problems and widening inequalities in unemployment and wages after the onset of recession.Reference Barr, Kinderman and Whitehead11 Furthermore, the increase in suicide risk post-recession has been found to be greater among those with low levels of education, who are likely to be more vulnerable to job loss, with increasing debt and challenges in finding employment in a competitive labour market.Reference Haw, Hawton, Gunnell and Platt12 Currently, the UK appears to be recovering from this global crisis although the outlook remains uncertain.Reference McDaid13

Suicide trends in mental health patients in relation to the recession have not previously been explored. They may or may not be the same as the recession-related trends in the general population. Suicide in mental health patients may involve different aetiological factors and processes from those operating in the general population. On the one hand some people receiving mental healthcare may be protected by being out of the labour market. On the other hand, they may be more vulnerable, particularly if care received is compromised by mental health services that are under increased resource pressure during a recession. A recent study suggested that economic hardship may intensify the social exclusion experienced by people with mental health problems.Reference Evans-Lacko, Knapp, McCrone, Thornicroft and Mojtabai14 In addition, individual-level sociodemographic and clinical information on those who have died by suicide before, during the recession and in the recent periods of economic recovery are limited, especially on a national level.Reference Coope, Donovan, Wilson, Barnes, Metcalfe and Hollingworth15 In this study we investigated recession-related trends in suicide in patients with a recent history of mental health service contact using a comprehensive national sample. Our specific objectives were to examine trends in suicide before and after the onset of the recession as well as the recent economic recovery period, and to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of those who were most affected at this time. We examined the effects for men and women separately given the established gender differences in suicidal behaviour.Reference Hawton16

Method

Data collection

Suicide data were collected as part of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH). NCISH collects in-depth, individual-level clinical information about those who died by suicide who have been in recent (<12 months) contact with mental health services. In summary, data collection occurred in three stages. First, information on all deaths in England that received a conlclusion of suicide or an undetermined (open) conclusion at coroner's inquest was obtained from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Undetermined conclusions were included as most are thought to be cases of suicide and are conventionally used in suicide rate estimation in the UK. Second, information on whether the deceased had been in contact with mental health services in the 12 months before death was obtained from the hospitals and community services providing mental healthcare in the deceased's district of residence and from the adjacent districts. Third, demographic and clinical data on those who had been in contact with services (referred to as ‘patients’) were obtained by sending a questionnaire to the responsible consultant psychiatrist. The questionnaire included sections covering sociodemographics, psychosocial history, method of suicide and aspects of care received prior to death. Some of the demographic and factual information (for example method of death) is also received from the ONS. Further detailed information on the data-collection process is available elsewhere.17

Quarterly suicide data were analysed between 2000 and 2016 and we investigated suicide rates in the adult age population (16 years or over). Suicide rates were determined using general population estimates in England as denominator data.18 Because of the time taken for patient data to be collected and processed, we had a questionnaire completeness rate of 80% in 2016. To avoid underestimation of suicide deaths, we used the suicide rate in the 80% of completed questionnaires to estimate the additional number of suicides expected had 100% of questionnaires been completed and returned. We began our analysis with time trend models investigating linear trends using joinpoint regression analysis, which can be used to describe changes in trend data.Reference Kim, Fay, Feuer and Midthune19 We estimated and identified points (i.e. ‘joinpoints’) where there were significant changes in temporal trends in suicide in both the patient and general population between 2000 and 2016. Although we were interested in the effects of the recession, rather than using fixed time points, joinpoint analysis enabled us to identify precisely where changes in trends occurred. This also allowed us to detect any lead or lag effects of the recession that may have been operating in relation to suicide rates. Previous work has suggested that the timing of recession-related changes in suicide may vary according to gender and age group.Reference Coope, Gunnell, Hollingworth, Hawton, Kapur and Fearn10 Next, we compared the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients who died by suicide during three time periods: 2004–2008, 2009–2011 and 2012–2016. These years were based on the joinpoint analysis and in line with changes in gross domestic product (GDP) and the UK labour market indicating when the recession occurred; we have referred to these as ‘pre-recession’ (2004–2008), ‘recession’ (2009–2011), and ‘recovery’ (2012–2016) periods.20 We examined gender-specific patient suicide deaths by age, employment status, marital status, primary psychiatric diagnosis, method of suicide and whether the person was an in-patient or a community patient at the time of death.

Statistical analysis

For the joinpoint analysis, we fitted regression models with suicide rates (calculated using general population estimates as denominators) as the dependent variable and the time period as the main independent variable. We used the grid-search method with uncorrelated errors and the permutation test to determine the best joinpoint models and we estimated the quarterly percent change (QPC) in suicide rates (with 95% CI) from the line segments between the ‘points’ identified. For patient suicide deaths, the analysis was also performed separately for age groups of 16–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64 and ≥65 for men and women. For the analysis on the three time periods pre- and post-recession, we fitted gender-specific multinomial logistic regression models. We compared the characteristics of individuals who died in each time period by calculating the odds of patients having particular clinical and demographic characteristics. We were interested in sequential changes and so compared each time period to the one preceding it. Thus, we compared patient characteristics in the recession period (2009–2011) to the pre-recession period (2004–2008), and patient characteristics in the post-recession period (2012–2016) to the recession period. Trend analysis was carried out using the Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 4.4.0.0 January 2017) from Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute.Reference Kim, Fay, Feuer and Midthune19 All other analyses were undertaken using Stata 13.1 software.21

Ethical approval

NCISH received approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee North West (Greater Manchester South, UK). Informed consent was not obtained as the participants were deceased. Exemption under Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006, enabling access to confidential and identifiable information without informed consent in the interest of improving care, was therefore also obtained from the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group.

Results

During 2000 to 2016, there were 77 184 suicide deaths in people aged 16 or over in England in the general population, a rate of 10.8 per 100 000 population. Male suicides rates were higher at 16.8 per 100 000 population and female suicide rates lower at 5.2 per 100 000 population. Of all the general population deaths, 21 224 (27%) were by people in contact with mental health services in the last 12 months. Two-thirds of patient suicides were among male patients (14 026, 66%).

Time trends: joinpoint analysis by gender and age group

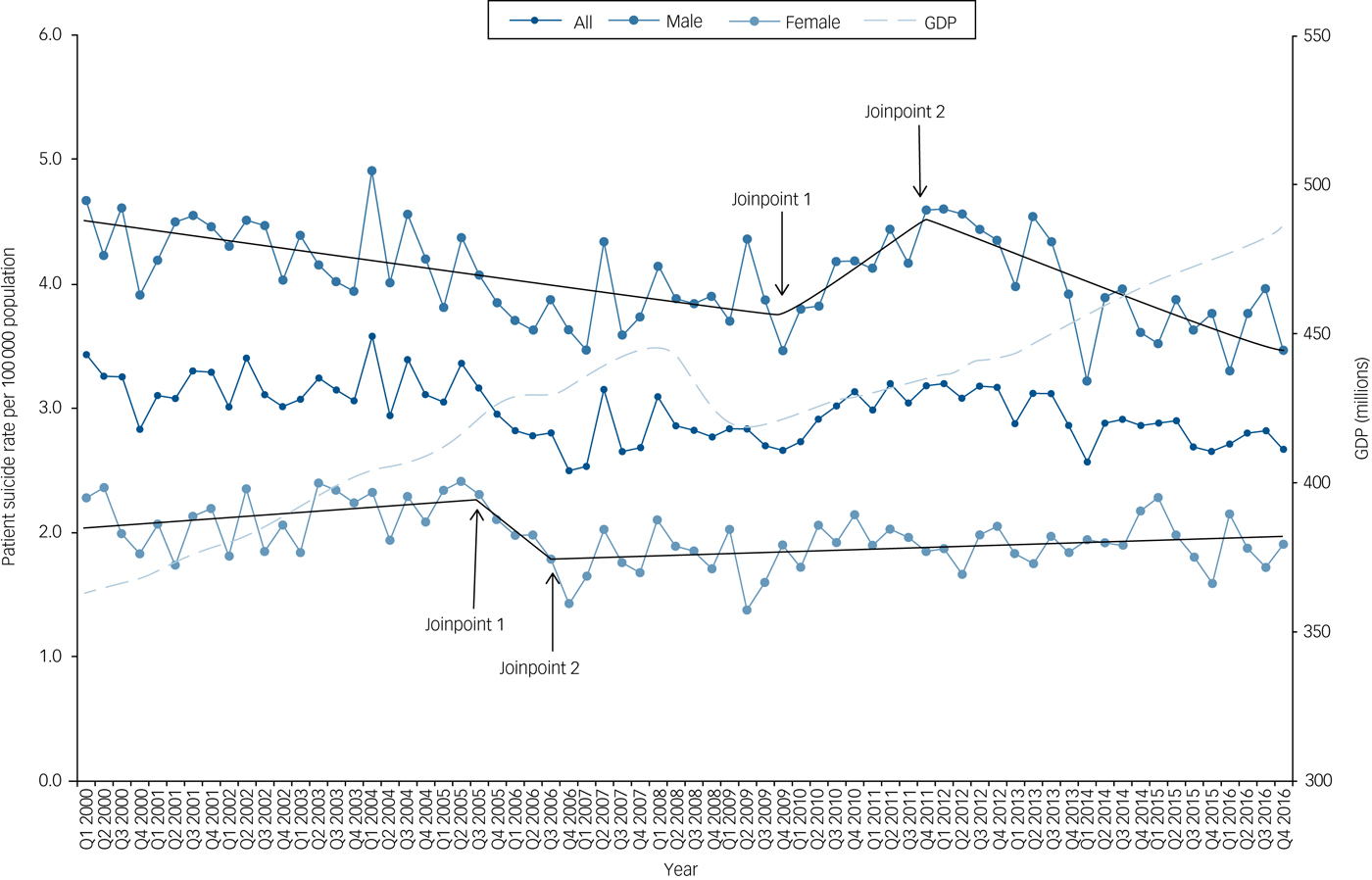

Figure 1 shows total and gender-specific patient suicide rates between 2000 and 2016 by quarter. For information we have also included trends in GDP, a measure of economic performance. The line segments measuring the QPC from the best joinpoint models for all suicide deaths and for men and women are also shown in Fig. 1. We identified two joinpoints for male patients and for female patients as the best models in the joinpoint analysis.

Fig. 1 Patient suicide rates and UK gross domestic product (GDP – low level aggregates) per quarter between 2000 and 2016.

We found there was a steady decline in male patient suicide rates of 0.5% per quarter from the beginning of 2000 to the last quarter of 2009 (QPC = –0.46, 95% CI –0.66 to –0.27, P<0.001) (Table 1). This was followed by a rise of 2.4% from the last quarter of 2009 till the end of 2011, (QPC = 2.37%, 95% CI –0.22 to 5.04, P = 0.07). Recent years from the last quarter of 2011 to the last quarter of 2016 showed a fall of 1.3% per quarter (95% CI –1.83 to –0.80, P<0.001). These trends were similar to those found in the general population. In female patients we found a non-significant fall between the third quarter of 2005 and the third quarter of 2006 (QPC = –5.69%, 95% CI –17.9 to 8.28, P = 0.4) but no significant trends over the study period (Table 1).

Table 1 Joinpoint regression models on trends in general population and patient suicide deaths between 2000 and 2016 in England by gendera

QPC, quarterly percent change between the changes in trends (joinpoints); Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, quarters 1, 2, 3, 4, respectively.

a. Results in bold indicate statistically significant findings.

Patient suicide deaths in men aged 16–24 showed a fall between quarter 1 of 2000 to quarter 3 of 2007 (QPC = –1.73, 95% CI –2.79 to –0.66, P = 0.002), after which they increased until the end of 2016, although the rise failed to meet the threshold of statistical significance at the 5% level (QPC = 0.68, 95% CI –0.12 to 1.48, P = 0.09) (Table 2). In men aged 45–54, suicide rates were stable between the beginning of 2000 to the last quarter of 2007 but this was then followed by an increase that lasted until the second quarter of 2012 (QPC = 1.84, 95% CI 0.42–3.29, P = 0.01), after which rates fell until the end of 2016. Trends in the older age groups showed a steady rise in the 55- to 64-year-olds and no changes in those aged ≥65.

Table 2 Joinpoint regression models on trends in male patient suicide deaths between 2000 and 2016 in England by age groupsa

QPC, quarterly percent change between the changes in trends (joinpoints); Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, quarters 1, 2, 3, 4, respectively.

a. Figures in bold indicate statistically significant results.

Patient suicide deaths in women showed no noticeable age-specific trends with the exception of falls in the 25- to 34-year-olds over the study period (QPC = –0.59, 95% CI –0.91 to –0.26, P = 0.001) and falls from the first quarter of 2005 to the end of the study period in women aged 55–64 (QPC = –0.54, 95% CI –1.03 to –0.05, P = 0.03).

Patient characteristics before, during and after the onset of the recession: comparing three time periods

There were significant differences in the three time periods with respect to characteristics of the patients who had died by suicide (see Tables 3 and 4 and also supplementary Tables 1 and 2 that include more detailed information for each time period, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.119). Men who died in the recession period (2009–2011) were more likely to be aged 45–54 compared with those who died in the pre-recession period (2004–2008). Women who died during the recession were more likely to be single compared with those who died pre-recession. In both genders, those who died during the recession were more likely to be unemployed and have had a diagnosis of drug dependence/misuse than those who died pre-recession. Conversely, those who died during the recession were less likely to be on long-term sickness benefit and be an in-patient than those who died during the pre-recession period.

Table 3 Comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of patients who died by suicide in England in pre-recession (2004–2008), recession (2009–2011) and economic ‘recovery’ (2012–2016) periods (a more detailed table including all data for the three periods is available as supplementary Table 1)a

a. Figures in bold indicate statistically significant results.

b. Multinomial logistic regression models: pre-recession as baseline group.

c. Multinomial logistic regression models: recession onset as baseline group.

Table 4 Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients who died by suicide in England in pre-recession (2004–2008), recession (2009–2011) and economic ‘recovery’ (2012–2016) periods (a more detailed table including all data for the three periods is available as supplementary Table 2)a

a. Figures in bold indicate statistically significant results.

b. Multinomial logistic regression models: pre-recession as baseline group.

c. Multinomial logistic regression models: recession onset as baseline group.

d. Method of suicide – excluding other methods.

In comparison with the recession period (2009–2011), the post-recession period (2012–2016) showed men who died were more likely to be aged 16–24, aged ≥65, retired and have died by hanging. They were less likely to be aged 35–44, on long-term sickness benefit, be an in-patient or to have died by self-poisoning. Women who died in the post-recession period were more likely to be single at the time of death, have a primary diagnosis of personality disorder and die by hanging compared with those who died in the recession period. They were less likely to have had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence or to have died by drowning.

Discussion

Our joinpoint analysis showed that there was a rise in the number of patient suicide deaths in men during the period of economic recession, with an upward trend from 2009–2011 similar in magnitude to the male general population during the same time period. This upward trend was particularly evident in men in midlife (aged 45–54 years). In younger men (aged 16–24 years) the historical fall in rates ended and there was a slight upward trend post-2007 that did not reach the level of statistical significance. We did not observe any recession-related trends in suicide rates among women during the study period.

In relation to changes in patient characteristics, those who died by suicide in the recession were more likely to be unemployed than those who died before the recession but less likely to be on long-term sickness. Changes in the diagnostic profile of patients who had died were evident for both men and women, with a rise in those with drug dependence/misuse during the recession.

Suicide deaths among male patients fell in the post-recession period (2012–2016) with the fall most evident among those aged 45–54 years. The recent period showed an increase in patient suicide deaths by hanging with corresponding falls in patient suicide deaths by self-poisoning in men and drowning in women compared with previous years.

Findings in the context of previous research

Consistent with previous studies, we found an adverse effect of the economic recession in male suicide deaths in the general population,Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee4–Reference Chang, Stuckler, Yip and Gunnell5,Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Scott-Samuel, McKee and Stuckler8 but an increase in patient suicide was also evident in our study. In women, studies have shown the incidence of suicide has been largely unchanged post-recession although reports have indicated a rise in self-harm rates.Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness and Cooper22 Similar to other studies, we found no recession-related trends in suicide rates in women, both in mental health patients and in the general population.Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee4,Reference Chang, Stuckler, Yip and Gunnell5,Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Scott-Samuel, McKee and Stuckler8

A previous study found a halt in downward trends in suicide rates in England and Wales in 2006 among the 16- to 24-year-olds and a rise among the 35- to 44-year-olds.Reference Coope, Gunnell, Hollingworth, Hawton, Kapur and Fearn10 In our study we found a similar halt in patient suicide rates among those aged 16–24 from the third quarter of 2007 to the end of the study period, but there were no changes in suicide trends in those aged 35–44. A rise in suicide deaths in middle-aged men after the onset of the recession has been reported in other studies.Reference Eliason and Storrie23 In line with previous literature, we found no recession-related trends in suicide rates among women.

We found the recession-related rise in patient suicide deaths in middle-aged men has been followed by a fall in the most recent years (2012–2016). Our study also found a fall in in-patient deaths post-2008 but this is unlikely to be related to wider economic factors as a continuous fall in in-patient suicide deaths between 2003 and 2011 has previously been shown.Reference Hunt, Rahman, While, Windfuhr, Shaw and Appleby24

Previous English studies have linked a rise in suicide with increases in unemployment,Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Scott-Samuel, McKee and Stuckler8 while others have found mixed evidence of an association between suicide and unemployment.Reference Saurina, Bragulat, Saez and López-Casasnovas25 We found an increase in the number of patient suicide deaths after the onset of the recession in those who were unemployed in both men and women. However, this rise coincided with a fall in suicide numbers in those who were long-term sick at the time of death. The upward trend in suicides after the beginning of the recession in young adult males may be explained by the difficulties faced in financing education or finding work for the first time.Reference Coope, Gunnell, Hollingworth, Hawton, Kapur and Fearn10 In contrast, middle-aged men may be more exposed to the risks associated with financial difficulties through job loss and benefit cuts. Of note, this rise in suicide in unemployed patients alongside a fall in those who were sick long-term could be linked to the introduction of employment and support allowance (ESA) in 2008 – a welfare benefit that replaced incapacity (sickness) benefit, income support and severe disability allowance paid because of a disability or illness.26 A welfare reform report found that re-assessments of those on incapacity benefit resulted in around a quarter of previous claimants not being deemed eligible for ESA.26 This reduction in the number of people receiving sickness-related benefit may account for the fall in the number of suicide deaths in this group. In addition, our finding of a rise in patient suicide deaths post-recession in men with drug dependence/misuse may be related to the effects of the recession increasing psychological stress resulting in increased drug use.Reference Nagelhout, Hummet, de Goeij, de Vries, Kaner and Lemmens27

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine recession-related trends and characteristics of suicides in a patient population. We were also able to investigate trends in the most recent years to examine the association between suicides and potential economic recovery. Nevertheless, certain limitations need to be highlighted.

First, we examined patient suicides rates using general population estimates as denominators rather than calculating more informed suicide rates from the target population, i.e. people with a mental illness in service contact. We considered using the number of people in contact with secondary mental health services as denominator data from the Mental Health Services Dataset – a routinely collected data-set of service contact.28 However, time periods were not comparable because of changes to the methodology of how these routine service data have been collected – first around 2011 and then again in 2014 and 2016 with the inclusion of other patient groups such as those with intellectual disabilities, and collection of data from independent organisations as well as a general improvement in data quality. These data have changed significantly over time with half a million men in service contact in 2005 rising to over 1.1 m in 2016. When we explored this further in post hoc analysis (details available on request from the authors) we found that the trends in patient suicide we observed in this study are unlikely to simply be as a result of changing levels of contact with mental health services.

Second, the three different time periods on which we examined patient characteristics were based on our joinpoint findings and on generally accepted pre-recession, recession and post-recession periods determined a priori. To account for any possible variation in recession onset or duration, we performed a sensitivity analysis comparing changes in patient characteristics between 2004–2007 to 2008–2012 and 2013–2016 and found no major differences in our results shown in Tables 3 and 4 and supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Third, with our study being ecological and observational, we need to be wary of the ecological fallacy. The aggregate-level findings may not be applicable to individuals. However, our comparison of patient characteristics was an individually based one. Fourth, although this was a national study the findings may not be applicable to other countries with different health systems.

Finally, we relied on clinicians to provide retrospective data on the patients who had died, which may introduce recall bias. However, most of the questionnaire items concerned objective information (such as gender, age, date of death, method of suicide, living circumstances, in-patient or community patient, treatment received, information on last contact) and the majority were completed by frontline clinicians who had seen or treated the patients prior to suicide (around three-quarters of respondents had direct contact with the patient). Some information such as the date of death and method of suicide was also obtained from ONS. NCISH response rates and data completeness are high.17

Implications

We found that the rise in male suicide deaths around the time of the recession reported in previous studies was also reflected in a clinical population. More recently, we found a fall in male patient suicide since 2012, and this was most marked in the group who experienced the largest recession-related rises in suicide (those aged 45–54). An improved economic outlook as well as better clinical services could have also played a role in this reduction.17

How might services and clinicians respond to these findings? Mental health service providers should be aware of the potential impact of wider economic factors on their patients who may be among the most vulnerable groups in society. This is particularly pertinent at a time when the UK faces further economic uncertainty as a result of its planned withdrawal from the European Union. Men in midlife and younger men may be most at risk. There has been an increase in the number of people accessing mental health services and it is important that patient safety more generally and suicide prevention in particular remain priorities.28 One of our findings was the fall in suicide among patients in 2012–2016 and this was against an increase in the number of people seen by services. This may be an indication of an increased focus on patient safety in services as a result of the National Suicide Prevention Strategy (2012).29 In addition, measures to tackle drug and alcohol misuse and greater emphasis on support and interventions for people experiencing economic strain, may help reduce the risk of mental illness and suicide at times of an economic recession.Reference Moore, Kapur, Hawton, Richards, Metcalfe and Gunnell30 Specific interventions such as job clubs or group cognitive–behavioural treatment might also be of benefit.Reference Robinson, Hetrick and Martin31

Funding

The study was funded by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study was part of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH) and we thank the other members of the research team: Pauline Turnbull, Cathryn Rodway, Alison Baird, Su-Gwan Tham, Myrsini Gianatsi, Jane Graney, Lana Bojanic, Nicola Richards, Rebecca Lowe, James Burns, Philip Stones, Julie Hall and Huma Daud. We thank the administrative staff in NHS Trusts who helped with the NCISH processes and the clinicians and nurses who completed the questionnaires.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.119.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.