Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), suicide is defined as the act of deliberately ending one’s life [1]. Epidemiologically, suicide is a leading cause of premature death that would be preventable [2]. Every year, 800,000 people die by suicide worldwide, corresponding to one death every 40 s [1]. For every suicidal death, an estimated 20 suicide attempts take place [1]. All regions of the world, developed and developing countries alike, are affected by this phenomenon [1]. Moreover, suicide significantly impacts both the individual’s close circle of friends and family and society as a whole [1]. This epidemiological data makes suicide a critical public health problem on a global scale. One of the objectives stated in WHO’s Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 was to reduce suicide rates by 10% by 2020 [2].

Suicide is associated with clearly established clinical risk factors, a history of suicide attempts being the most consistent among them [1]. A meta-analysis has shown that among suicide-risk factor associations, the strongest is the one between suicide and previous suicide attempts (odds ratio [OR] = 16.33; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 7.51–35.52) [Reference Yoshimasu, Kiyohara and Miyashita3]. Another significant association reported in said study [Reference Yoshimasu, Kiyohara and Miyashita3] is between suicide and mood disorders, including depressive disorders (OR = 13.42; 95% CI = 8.05–22.37).

In addition to clinical risk factors, the social environment, including interpersonal relationships, correlates to suicide and can be effectively targeted from a prevention perspective [1]. This literature review focuses specifically on social isolation as a potential suicide risk factor.

E. Durkheim was the first to emphasize the importance of social variables in the etiology of suicide in his 1897 sociological study [Reference Durkheim4]. In 2005, T. Joiner [Reference Joiner5] put forward a new theoretical model of suicide, the interpersonal theory of suicide. Their studies concur in highlighting the significant role that social isolation plays in the suicidal process.

In light of the international scope of the literature on the link between suicide and social isolation, this study examines this relationship by drawing on published research regardless of the nature of the sources. The objective is to identify specific characteristics mentioned in the international literature regarding the relationship between suicide and social isolation. Theoretical bases on the subject will be addressed, and perspectives on intervention, especially prevention, and future research will be discussed.

Method

We conducted a literature review concerning the association between a social variable, that is, social isolation, and suicide. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman6] to ensure methodology appropriateness and accurate results reporting.

We conducted searches in two databases: Medline via PubMed and PsycINFO. During an informal preparatory exploration of the literature, the keyword “isolation” emerged as the term that was typically used to refer to the concept under study, leading us to adopt the search formula: “suicid*” AND “isolation.” Articles published through April 2020 were considered in the final search conducted in May 2020. We did not limit the database search by publication date.

The eligibility criteria used to select the articles included were the following:

(a) Articles that, according to their abstract, dealt mainly with the relationship between the social variable, that is, social isolation or other related social concepts, and any of the stages of the suicidal process (suicide ideation, suicide attempt, completed suicide) or more generally with suicide risk; (b) Articles published in English, for international visibility; and (c) Articles whose abstracts were available in either database.

We exported article publication data (authors, title, journal, year of publication) from the searches into a word processing program (Word 2016). We removed duplicates during data processing after reading the title and abstract of each article.

Whenever there was doubt about whether an article should be included, a discussion was held between two independent experts until they reached a consensus.

Results

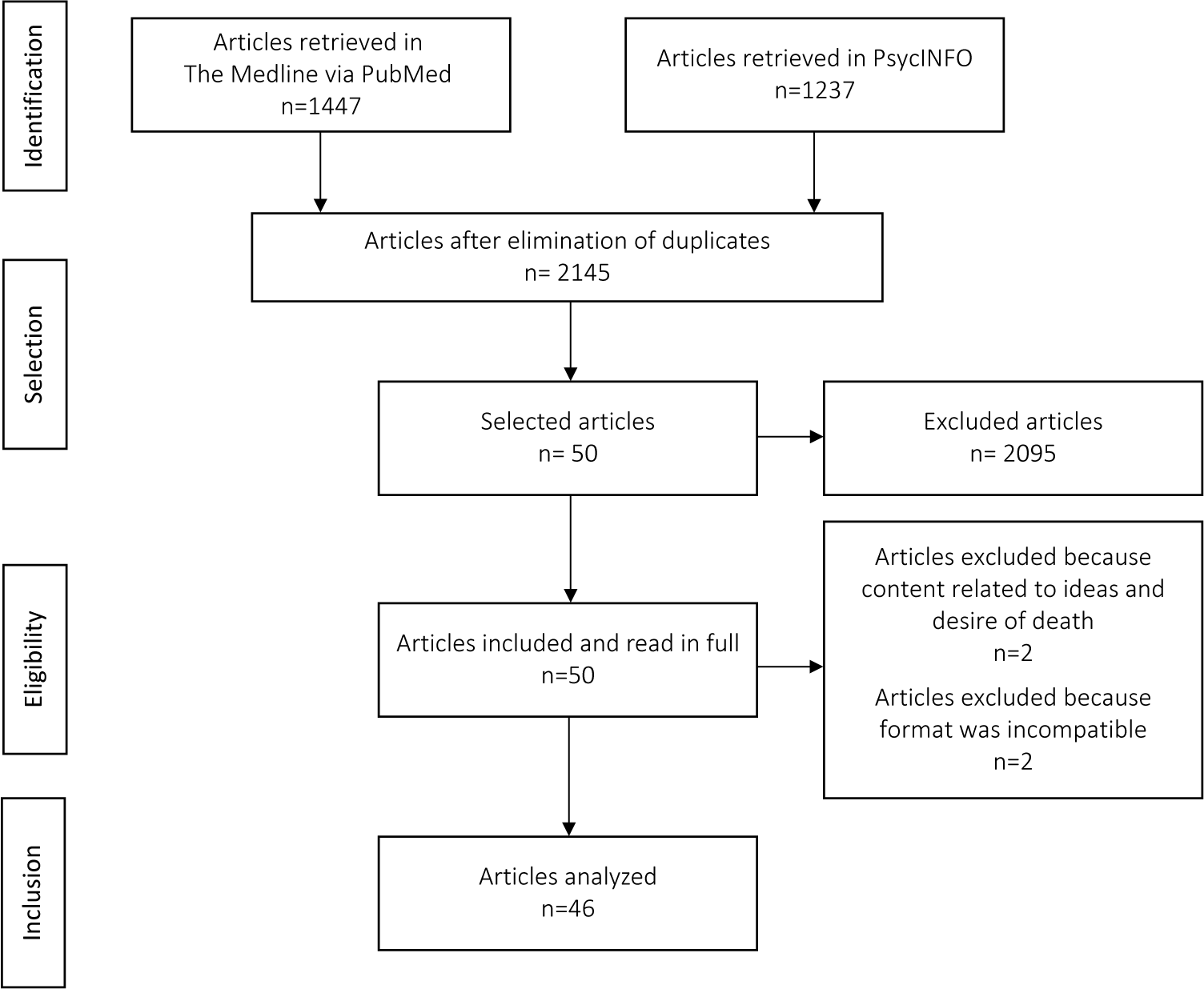

A flow chart of the research process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart.

Out of the 2,684 articles whose abstracts were retrieved, 50 were read in full, and 46 were included for analysis. We excluded two articles because the topics were the desire for and ideas about death rather than ideation relating to actively ending one’s own life. In fact, those studies had excluded participants with suicidal ideation. We excluded two other articles based on their publication format: a letter and an editorial.

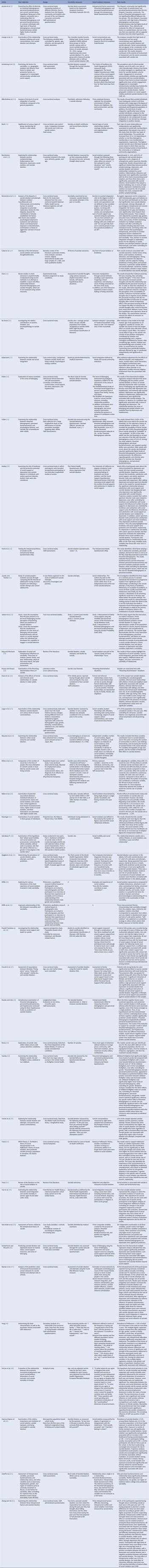

Methodological data for the analyzed articles are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Methodological data of the articles analyzed.

Note: X: information not available.

Theoretical basis

Among the different visions concerning suicidology research, the one stemming from sociology and from E. Durkheim’s investigation on the influence of social causes on suicide is major [Reference Krauss and Krauss25]. By establishing that suicide rates are inversely correlated with social integration, E. Durkheim was the first to highlight the social dimension as a causal factor in suicide [Reference Durkheim4]. Durkheim described the type of suicide linked to a lack of social integration as egotistic [Reference Durkheim4]. Consequently, social isolation and social support seem to appear respectively as risk and protective factors for suicide. Durkheim’s hypothesis of social integration as a cause of suicide, based on a model of social disorganization, was re-examined by M. Halbwachs in his comprehensive statistical study of the causes of suicide [Reference Halbwachs53]. Halbwachs proposed a psychosocial theory of suicide, arguing that a suicidal act should be considered from two different angles, one relating to individual causes and the other to social causes [Reference Trout43]. According to T. Joiner’s interpersonal theory of suicide, social connection is also a key element in the suicidal process. He posits that simultaneous thwarted belongingness, that is, a feeling of no longer being an integral part of a group, and perceived burdensomeness, that is, a feeling of being a burden to others, are at the root of the emergence of suicidal ideation. The concomitant presence of the cognitive factors of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness leads to the emergence of suicidal desire, which, with the acquisition of suicidal capability, often developed through repeated suicide attempts, may evolve into suicidal acting out. These theoretical models have been explored and largely validated by a number of studies. Therefore, they provide robust explanatory frameworks to explain the relationship between social isolation and suicide risk. Research on the relationship between either social isolation or social support and suicidality is abundant and spans several decades. From P. Sainsbury’s 1955 work [Reference Sainsbury32] to a review of the literature dating from 1980 [Reference Trout43] to an experimental study conducted in 2020 [Reference Chen, Poon, DeWall and Jiang15], many researches draw the same conclusion and consider social isolation as a major suicide risk factor.

There is no consensus on the definition of social isolation, but it can be described as a state in which interpersonal contacts and relationships are disrupted or non-existent [Reference Trout43]. In the articles reviewed, social isolation and related concepts were assessed in various ways, ranging from qualitative descriptive variables such as social networks, single relationship status, and living alone, to quantitative assessment scales, the most widely used of which was the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) [Reference Acosta, Hagan and Joiner7, Reference Hunt, Weiler, McGuire, Mendenhall, Kobak and Diamond21, Reference Roeder and Cole38, Reference Stanley, Hom, Gai and Joiner40, Reference Zaroff, Wong, Ku and Van Schalkwyk51]. The INQ, a self-administered questionnaire derived from the Interpersonal Suicide Theory [Reference Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte and Joiner54], includes 15 self-reported items measured on a 7-point Likert scale anchored with 1 (Not at all true for me) to 7 (Very true for me). The first six items of the INQ correspond to perceived burdensomeness and the remaining nine to thwarted belongingness.

Several factors that further characterize the relationship between suicide and social isolation emerged from the articles reviewed. These include age and gender, as well as psychopathology and specific circumstances.

Role of age and gender

Suicidality affects individuals of any age and gender. However, depending on these demographic factors, there are differences in the relationship between suicidality and social isolation [1, Reference Bille-Brahe and Wang10]. For example, one study showed that age and gender impact social isolation [Reference Bille-Brahe and Wang10], with evidence that levels of social integration varied according to these factors. Therefore, age and gender have a confounding potential that justifies their routine control in research on the relationship between suicide and social isolation [Reference Hunt, Weiler, McGuire, Mendenhall, Kobak and Diamond21, Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte, Selby, Ribeiro and Lewis23].

Two age groups require special attention: individuals aged 70 and older, who have the highest suicide rates, and younger individuals, aged 15–29, in whom suicide is the second leading cause of death. In addition to the high suicide rates in the elderly [1], suicide attempts in this population are more often fatal, with a ratio of suicide attempts to the suicide of 4:1 [Reference Fullen, Shannonhouse, Mize and Miskis19]. This reinforces the importance of the suicidality problem in the elderly. Social isolation seems to play a central role in suicidality for both seniors and adolescents, but the social contexts inherent to age are different. On the one hand, aging is inevitably accompanied by the loss of interpersonal relationships, the most impactful being the loss of a spouse. On the other hand, adolescence is a period of life marked by disruptions in social bonds, which can become weaker. Our review suggests that, in these two age categories, the family circle is a powerful vector of social support [Reference Bock11, Reference King and Merchant24, Reference Kwon, Jeong and Choi26, Reference Logan, Crosby and Hamburger27, Reference Purcell, Heisel, Speice, Franus, Conwell and Duberstein37]. Informal relationships, especially with children, are even more protective of suicidal thoughts in older adults living alone than formal relationships created officially by society like paid caregivers [Reference Kwon, Jeong and Choi26]. Schooling has also been found to be a protective social factor for adolescents [Reference Armstrong and Manion9, Reference Logan, Crosby and Hamburger27, Reference Tomek, Burton, Hooper, Bolland and Bolland41, Reference Wyman, Pickering, Pisani, Rulison, Schmeelk-Cone and Hartley47]. Involvement in meaningful extracurricular activities [Reference Armstrong and Manion9] as well as school determinants of adolescent social networks, particularly with adults [Reference Wyman, Pickering, Pisani, Rulison, Schmeelk-Cone and Hartley47], should be leveraged in the development of interventions to prevent suicidality in young individuals. Therefore, seniors and youth are both age groups for which the fight against social isolation looks like a major lead for suicide prevention.

Social isolation affects both male and female suicidality, but the extent of its influence differs by gender [Reference Poudel-Tandukar, Nanri, Mizoue, Matsushita, Takahashi and Noda36, Reference Yur’yev, Värnik, Sisask, Leppik, Lumiste and Värnik49]. Our review reveals that social isolation and suicidality appear to be more strongly associated with men than women. This result should be accounted for when considering that men have higher rates of suicide mortality [1]. In high-income countries, three times more men die by suicide than women, and in middle- and low-income countries, the suicide rate for men is 1.6 times that of women. In male suicidality, social isolation seems to be a leitmotif of various life areas ranging from family to society [Reference Oliffe, Broom, Popa, Jenkins, Rice and Ferlatte34, Reference Oliffe, Creighton, Robertson, Broom, Jenkins and Ogrodniczuk35]. Therefore, men represent a population at higher risk of suicide partly because of social isolation, to which they are probably more exposed or vulnerable. These findings warrant promoting social bonding in suicide policy interventions with this subgroup.

Psychopathology and specific circumstances

Psychopathology

Other factors, psychopathological in particular, may also be at play in the relationship between social isolation and suicidality. The scientific literature presents evidence of a bidirectional relationship between social isolation and mental health [Reference Näher, Rummel-Kluge and Hegerl30]. Indeed, social isolation can affect mental health and, conversely, it can be dependent on it. First, it is appropriate to address E. Ringel’s “pre-suicide syndrome,” which situates social isolation within the chronology of a suicidal crisis. Currently, social isolation is considered an integral part of suicide crisis assessment and a red flag indicating potential suicide with a risk of imminent action [Reference Ringel55]. Among psychiatric disorders, the literature reviewed suggests that depressive disorders are closely linked to social isolation and suicide, with evidence of a bidirectional relationship between clinical depression and social isolation. Moreover, in several articles analyzed, the results reported were adjusted for depression to account for its confounding potential [Reference Chen, Poon, DeWall and Jiang15, Reference Fisher, Overholser, Ridley, Braden and Rosoff18, Reference Hunt, Weiler, McGuire, Mendenhall, Kobak and Diamond21, Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte, Selby, Ribeiro and Lewis23, Reference Kwon, Jeong and Choi26, Reference Tsai, Lucas and Kawachi44, Reference Van Orden, Smith, Chen and Conwell45, Reference Wyman, Pickering, Pisani, Rulison, Schmeelk-Cone and Hartley47]. Results diverge regarding whether social isolation should be considered as a suicidal risk factor independently from depression [Reference Chen, Poon, DeWall and Jiang15, Reference Fisher, Overholser, Ridley, Braden and Rosoff18, Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte, Selby, Ribeiro and Lewis23, Reference Kwon, Jeong and Choi26, Reference Ojagbemi, Oladeji, Abiona and Gureje33, Reference Tsai, Lucas and Kawachi44, Reference Zaroff, Wong, Ku and Van Schalkwyk51], leading to the assumption that social and mental health issues should be regarded as synergetic factors to improve the reliability of suicidality assessments. This view is supported by the mediation effects of both social isolation and depressive disorders on suicidality reported in some articles [Reference Purcell, Heisel, Speice, Franus, Conwell and Duberstein37, Reference Roma, Pompili, Lester, Girardi and Ferracuti39–Reference Tomek, Burton, Hooper, Bolland and Bolland41].

In addition, social isolation is integral to the symptomatology of some mental disorders. This is the case for autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia, for example. In both conditions, social functioning is generally impaired and interpersonal relationships are often poor [56], requiring appropriate consideration regarding their risk of suicide. One final clinical picture that should be considered is the hikikomori, initially described in Japan. Hikikomori refers to people who avoid social participation and relationships with people outside their family circle by confining themselves to their home or a room in their home for at least 6 months [Reference Yong and Nomura48]. Hikikomori is a mental health condition involving both relational difficulties and a significant risk of suicide, potentially representing a theoretical model of social isolation in which suicide causality can be explored.

Psychopathology is a key element to account for when studying the link between social isolation and suicidality, hence the importance of considering the bidirectional relationship between social isolation and mental health issues.

Specific circumstances

Recent research has identified specific circumstances as a moderating factor in the relationship between social isolation and suicide. These circumstances should therefore draw specific attention to suicide prevention. In sexual minorities such as the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) community, and ethnic minorities such as the Alaskan Native community, social isolation seems to have a different and greater impact on suicidality than it does in the general population [Reference Bränström, van der Star and Pachankis13, Reference Travis42, Reference Zamora-Kapoor, Nelson, Barbosa-Leiker, Comtois, Walker and Buchwald50]. Moreover, as a determinant of interpersonal relationships, culture should be considered when exploring the link between social isolation and suicide. Social isolation has probably a more substantial influence on suicidality in individualistic cultures than in collectivistic cultures such as the Chinese and Hispanic communities [Reference Acosta, Hagan and Joiner7, Reference Zhang and Jin52]. Regarding the occupational sphere, some occupations and professional environments can facilitate social isolation, thus could lead to higher risks of suicidality [Reference Oliffe, Broom, Popa, Jenkins, Rice and Ferlatte34, Reference Stanley, Hom, Gai and Joiner40]. Unemployment, a known suicidal risk factor, can also reduce or even eliminate important social ties [Reference Calati, Ferrari, Brittner, Oasi, Olié and Carvalho14]. Finally, other forms of isolation must be taken into consideration. The physical isolation of detained individuals and the geographical isolation of people living in rural areas are two situations known to be associated with suicide [Reference Armstrong and Manion9, Reference Calati, Ferrari, Brittner, Oasi, Olié and Carvalho14, Reference Ojagbemi, Oladeji, Abiona and Gureje33, Reference Roma, Pompili, Lester, Girardi and Ferracuti39].

Perspectives

Prevention targets

The possible causal relationship between social isolation and suicide and the opposite potential protective effect of social support have key implications for the fight against suicide. Associations and correlations have been identified in this literature review, including relationships between other variables and suicidality appearing to be mediated by social isolation and related social concepts [Reference Bornheimer, Li, Im, Taylor and Himle12, Reference Bränström, van der Star and Pachankis13, Reference Stanley, Hom, Gai and Joiner40, Reference Zamora-Kapoor, Nelson, Barbosa-Leiker, Comtois, Walker and Buchwald50]. Consequently, social isolation might be a suicide risk factor that multiple actions should target to counteract the influence of individual risk factors. While there is a substantial body of literature suggesting social isolation as a major suicide risk factor, the response in terms of specific interventions is not commensurate with this proposal. This review has identified several variables that help clarify the link between social isolation and suicide, including age, gender, psychopathology, and other specific circumstances. Building on this information, groups at risk for the adverse consequences of social isolation should be routinely identified among the general population to benefit from preventive interventions, including targeted information campaigns in select environments such as schools for young people [Reference Wyman, Pickering, Pisani, Rulison, Schmeelk-Cone and Hartley47]. Such universal prevention initiatives could be complemented by raising awareness among healthcare providers and frontline social workers about the relationship between social isolation and suicide. Isolated persons can be identified by asking simple questions focusing on the individual’s degree of social isolation [Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte, Selby, Ribeiro and Lewis23]. Tools such as the INQ can also be used to assess the level of thwarted belongingness experienced by individuals in the community [Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte, Selby, Ribeiro and Lewis23].

Outreach

In addition to prevention strategies leveraging mental health services, proximity interventions that strengthen or create social ties, ranging from the family to the community environment, could be supported. Regardless of age, the focus should be placed on family interpersonal relationships [Reference Bock11, Reference King and Merchant24, Reference Kwon, Jeong and Choi26, Reference Logan, Crosby and Hamburger27, Reference Purcell, Heisel, Speice, Franus, Conwell and Duberstein37]. Moreover, educational and work environments likely require specific interventions. Since school connectedness appears to be a strong protective factor for adolescents [Reference Armstrong and Manion9, Reference Logan, Crosby and Hamburger27, Reference Tomek, Burton, Hooper, Bolland and Bolland41, Reference Wyman, Pickering, Pisani, Rulison, Schmeelk-Cone and Hartley47], facilitating engagement in extracurricular activities, improving youth-adult networks, and strengthening the positive influence of youth with strong coping mechanisms toward their suicidal peers within school settings could help to reduce youth suicidality [Reference Armstrong and Manion9, Reference Wyman, Pickering, Pisani, Rulison, Schmeelk-Cone and Hartley47]. For adults, fostering a strong sense of belonging in workplace environments and providing intensive support in situations in which the sense of belonging is threatened, especially in certain occupations facilitating isolation or during unemployment, seems to be key actions against the emergence of suicidality [Reference Calati, Ferrari, Brittner, Oasi, Olié and Carvalho14, Reference Oliffe, Broom, Popa, Jenkins, Rice and Ferlatte34, Reference Stanley, Hom, Gai and Joiner40]. Finally, community integration through membership in organizations, among other things, looks crucial in the fight against suicide [Reference Bille-Brahe and Wang10, Reference Bock11]. Formal social relationships providing alternative sources of social support should be developed within society when required, for example, through home-based interventions with isolated older adults [Reference Fullen, Shannonhouse, Mize and Miskis19, Reference Kwon, Jeong and Choi26].

Regarding specialized psychiatric care, insofar as psychiatric drug therapy does not involve social participation [Reference Yong and Nomura48], socially involved and action-oriented psychotherapeutic approaches should be provided. More specifically, assumed influences of social isolation and social support on suicide suggest that family and group-based therapies should be favored over exclusively individual therapies [Reference Trout43]. From the perspective of the interpersonal theory of suicide, cognitive-behavioral therapeutic interventions targeting cognitive distortions of thwarted belongingness as well as participation in social activities can be considered [Reference Joiner, Van Orden, Witte, Selby, Ribeiro and Lewis23]. The relationship with the therapist can also enhance the sense of belonging [Reference Fisher, Overholser, Ridley, Braden and Rosoff18].

Discussion

General

The purpose of this review was to explore the relationship between suicide and a social variable, social isolation, as reported in the international literature. Our findings, drawn from theoretical models and a large number of empirical studies, suggest a basic relationship between suicide and social isolation and portray variations within this relationship related to age, gender, psychopathology, and specific circumstances. Furthermore, this review highlighted the potential protective effect of social support on suicide. Nevertheless, some social ties may be harmful rather than protective and promote suicidality, such as when the other person is suicidal or has ended their life or when someone is a victim of harassment.

The studies included in this review used a diversity of variables and questionnaires covering all kinds of areas of life to assess social isolation. Social isolation thus appears to be a general, overarching condition that arises from multiple social parameters [Reference Oliffe, Broom, Popa, Jenkins, Rice and Ferlatte34]. As a result, in the context of suicidality assessments, social isolation must be viewed as a complex phenomenon with no set definition. This literature review focuses on social isolation as the objective portrayal of a social situation characterized by poor social ties. However, socially isolated individuals may not feel lonely, and vice versa [Reference Calati, Ferrari, Brittner, Oasi, Olié and Carvalho14, Reference Oliffe, Creighton, Robertson, Broom, Jenkins and Ogrodniczuk35]. The concept of loneliness refers to the subjective aspect of the social condition of isolation. Loneliness can be described as a complex set of feelings encompassing reactions to the absence of intimate and social needs [Reference Ernst and Cacioppo57]. Consequently, a combined assessment of social isolation and loneliness may clarify a lived situation of isolation in relation to suicidality.

Review strengths and limitations

The main strength of this literature review lies in the broad scope and varied nature of the articles examined. However, there are limitations pertaining to the methodological heterogeneity of the selected articles, complexifying comparisons and therefore limiting the repeatability of our analysis. First, most of the studies included were cross-sectional in design, although some used data extracted from longitudinal research [Reference Fullen, Shannonhouse, Mize and Miskis19, Reference Hedley, Uljarević, Foley, Richdale and Trollor20, Reference Näher, Rummel-Kluge and Hegerl30, Reference Ojagbemi, Oladeji, Abiona and Gureje33, Reference Tomek, Burton, Hooper, Bolland and Bolland41, Reference Zamora-Kapoor, Nelson, Barbosa-Leiker, Comtois, Walker and Buchwald50]. Few of the studies reviewed were longitudinal [Reference Chen, Poon, DeWall and Jiang15, Reference Poudel-Tandukar, Nanri, Mizoue, Matsushita, Takahashi and Noda36, Reference Roeder and Cole38, Reference Tsai, Lucas and Kawachi44], precluding the establishment of causality in the results and only allowing for correlations to be highlighted. In order to improve our understanding of the relationship between social isolation and suicide and to develop optimal suicide prevention by acting on the social environment, it is necessary to conduct longitudinal studies in the future [Reference Näher, Rummel-Kluge and Hegerl30, Reference Wyman, Pickering, Pisani, Rulison, Schmeelk-Cone and Hartley47], in particular research evaluating the effectiveness of interventions aimed at supporting social connectedness.

Second, analysis procedures also varied from one study to another, particularly regarding whether confounding factors were taken into account. In the studies that controlled for confounding factors, the factors considered (e.g., age, sex, psychiatric disorder, socioeconomic status) were not always the same. The populations studied were also often different: samples or various sizes, more or less representative of the general population, of different age groups, gender, countries, ethnic origins, and cultures.

Third, the studies relied on many different measures of suicidality and social isolation or support, mainly self-reports [Reference Bock11, Reference Bränström, van der Star and Pachankis13–Reference Duberstein, Conwell, Conner, Eberly, Evinger and Caine17, Reference Hedley, Uljarević, Foley, Richdale and Trollor20, Reference Jacobs and Teicher22, Reference Krauss and Krauss25–Reference Masuda, Kurahashi and Onari28, Reference Näher, Rummel-Kluge and Hegerl30, Reference Purcell, Heisel, Speice, Franus, Conwell and Duberstein37, Reference Roma, Pompili, Lester, Girardi and Ferracuti39, Reference Tomek, Burton, Hooper, Bolland and Bolland41, Reference Trout43, Reference Van Orden, Smith, Chen and Conwell45, Reference Vanderhorst and McLaren46, Reference Zamora-Kapoor, Nelson, Barbosa-Leiker, Comtois, Walker and Buchwald50, Reference Zaroff, Wong, Ku and Van Schalkwyk51]. Variables representing social isolation varied and were assessed in several different ways. Several of the studies used the INQ [Reference Acosta, Hagan and Joiner7, Reference Hunt, Weiler, McGuire, Mendenhall, Kobak and Diamond21, Reference Roeder and Cole38, Reference Stanley, Hom, Gai and Joiner40, Reference Zaroff, Wong, Ku and Van Schalkwyk51], providing relative objectivity in measurement and improving the reliability of their results. However, in most studies, social isolation was determined based on variables selected as best approximating this concept, such as social network, single relationship status, or living alone. In addition, one study elicited the feeling of social isolation in an experimental manner (i.e., recalling a past experience, imagining a future experience, and inducing a sense of being ostracized at the time of the study), allowing for greater reproducibility and assessment reliability [Reference Chen, Poon, DeWall and Jiang15]. Suicidality was also measured in multiple ways, focusing on all stages of the suicidal process or, more globally, on the suicide risk. Less than half of the studies selected used the number of deaths by suicide as a variable [Reference Bock11, Reference Calati, Ferrari, Brittner, Oasi, Olié and Carvalho14, Reference De Grove16, Reference Duberstein, Conwell, Conner, Eberly, Evinger and Caine17, Reference King and Merchant24, Reference Krauss and Krauss25, Reference Milner, Page, Morrell, Hobbs, Carter and Dudley29, Reference Näher, Rummel-Kluge and Hegerl30, Reference Sainsbury32, Reference Poudel-Tandukar, Nanri, Mizoue, Matsushita, Takahashi and Noda36, Reference Roma, Pompili, Lester, Girardi and Ferracuti39, Reference Travis42–Reference Van Orden, Smith, Chen and Conwell45, Reference Yur’yev, Värnik, Sisask, Leppik, Lumiste and Värnik49]. The number of suicides is the most factual variable, but the rarity of this event often makes it necessary to assess suicidality through alternative measures. The multiplicity of methods used to assess social isolation and suicidality raises the need for harmonizing measures and even the development of a standardized measure for each of these variables in international research.

Actuality and media consumption

There is a further risk factor of suicide, which is distally associated with social isolation: media consumption. At the beginning of the current health context of the pandemic in Covid-19, physical distancing was adopted as a primary strategy. Thus, there was an increasing reliance on social-platform outlets to connect to others [Reference Sisler, Kent-Marvick, Wawrzynski, Pentecost and Coombs58]. Media content may be associated with increases in suicides. For example, the reporting of celebrity suicides appears to have had a notable impact on the total number of suicides in the general population [Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Braun, Pirkis, Till, Stack and Sinyor59]. Yet, the media can also have positive effects on suicidality. Indeed, media narratives of hope and recovery from suicidal crises appear to have a beneficial effect on suicidal ideation in individuals with some vulnerability [Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Till, Kirchner, Sinyor, Braun and Pirkis60].

Conclusion

This literature review emphasizes a correlation between suicide and social isolation while suggesting that, conversely, social support has likely a protective factor against suicidality. This research also highlighted age, gender, psychopathology, and specific circumstances as essential variables that must be considered when studying the relationship between suicide and social isolation and developing intervention strategies targeting at-risk populations. Social isolation is a complex phenomenon that must be recognized as a major public health issue, a societal problem against which actions can be taken. However, there is a gap between the abundant literature showing the potential suicide risk associated with social isolation and the response in terms of appropriate interventions. Interventions must address social isolation in an interdisciplinary manner, through joint action involving the health and social sectors, on several levels ranging from prevention to therapy, and from local-scale proximity interventions to large-scale international policies.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from two databases Medline via PubMeb and PsycINFO. Possible restrictions apply to the availability of these data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.M.-T., M.W., S.B., C.L.; Investigation: C.M.-T.; Methodology: C.M.-T.; Project administration: C.M.-T., M.W.; Validation: C.M.-T., M.S., J.-D.C, S.B., C.L.; Writing—original draft: C.M.-T.; Writing—review and editing: C.M.-T., M.S., J.-D.C., S.B., C.L.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.