Black and Latinx caregiversFootnote 1 are commonly exposed to both parenting stress (i.e., Nam et al., Reference Nam, Wikoff and Sherraden2015) and racism-related stress (e.g., Berry, Reference Berry2021; Condon et al., Reference Condon, Barcelona, Ibrahim, Crusto and Taylor2022; Heard-Garris et al., Reference Heard-Garris, Cale, Camaj, Hamati and Dominguez2018). Parenting stress and racism-related stress may convey secondary risks for their child’s psychosocial outcomes (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015; Heard-Garris et al., Reference Heard-Garris, Cale, Camaj, Hamati and Dominguez2018). Racism-related stress in caregivers may also heighten distress in other domains, including parenting stress and mental health symptoms. Thus, more research is needed to clarify the associations between racism-related stress, parenting stress, and psychological well-being in caregivers and their youth offspring. Additionally, given this context, it is critical to understand whether caregiver-focused interventions, which often target parenting stress and parent-child relationships more broadly, may have supportive secondary impacts of reducing racism-related stress among ethnoracially minoritized caregivers. Mentalizing-focused parenting groups, which aim to strengthen caregiver-child relationships via increased attachment security and reduced parenting stress, may be uniquely positioned to attenuate the impacts of racism-related stress on both the caregivers and their children because of their focus on promoting caregivers’ sense of social support, belongingness, and reflective capacity (Zayde et al., Reference Zayde, Prout, Kilbride and Kufferath-Lin2021). Thus, the current study examined the associations between racism-related stress (e.g., frequency of and distress related to experiences of racial discrimination), parenting stress, and psychological distress, and the potential crossover effect of a mentalizing-focused parenting intervention on racism-related stress among a sample of ethnoracially minoritized caregivers seeking parenting support.

Theoretical framework

The current study is guided primarily by the integrated model of studying stress within African American families put forth by Murry et al. (Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018). This model outlines how sociocultural factors such as experiences of racism and marginalization are not only the result of systemic racism, but also lead to families from specific ethnoracial backgrounds being placed in marginalized positions. The marginalized social positions of African American and Latinx families, among others, increase exposure to mundane and extreme environmental stressors (e.g., insufficient healthcare services, neighborhood stressors; Carroll, Reference Carroll1998; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018). Exposure to these types of stressors may then go on to exacerbate families’ vulnerability to internal stressors, which may negatively impact family functioning in the form of increased parenting stress, impaired relationships among family members, and impairments in mental and physical health functioning (Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018). A strength of this model is that it also incorporates strengths-based cultural assets (e.g., racial socialization and identity, family cohesion, cultural values, etc.) to underscore that African American and other ethnoracially minoritized families utilize culturally relevant coping skills to navigate sociocultural and environmental stressors (Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018). Furthermore, the Murry et al. (Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018) model highlights how these strengths-based assets are essential to reducing the negative impact of risk factors and promoting adaptive family environments and capacities (e.g., family relationships, psychological functioning, biological responses to stress, etc.). In this way, culturally specific assets contribute to the positive development, adjustment, and adaptation of ethnoracially minoritized families over their life span (Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018). In line with this model, the current study explores how experiences of racial discrimination not only contributes to increased parenting stress that may compromise family relationships and functioning, but also negatively impacts the psychological functioning of both ethnoracially minoritized caregivers and their children. Furthermore, just as the model highlights how positive family relationships lead to the positive development of ethnoracially minoritized families, the current study sought to explore if a mentalizing-focused intervention aimed at both reducing the stress of various risk factors (e.g., racism-related stress, environmental stress), and strengthening the parent-child relationship can further facilitate the positive development of ethnoracially minoritized families and support the existing strengths-based cultural assets that exist within these families.

Parenting stress among ethnoracially minoritized caregivers

Parenting stress, or the experience of burdens associated with the parenting role and its responsibilities (Abidin, Reference Abidin1992; Belsky, Reference Belsky1984), may negatively impact the psychological health of both caregivers and their children, including those from ethnoracially minoritized backgrounds (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Brown, Brody, Cutrona and Simons2001). Generally, multiple aspects of the caregiving experience may contribute to parenting stress, but most commonly considered are a parent’s perception of their child’s emotional or behavioral difficulties, a parent’s dissatisfaction with the parent-child relationship, and negative psychological experiences of the parental role (e.g., as isolating; Abidin, Reference Abidin1992; Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard1998). Across racial-ethnic populations, parenting stress has been associated with negative perceptions of one’s child and more distress while parenting (e.g., hostile attributions, emotional upset, worry about child’s future), harsher discipline responses, and lower self-efficacy and self-perceived parenting competence (e.g., Jackson & Huang, Reference Jackson and Huang2000; Pinderhughes et al., Reference Pinderhughes, Dodge, Bates, Pettit and Zelli2000; Williford et al., Reference Williford, Calkins and Keane2007). Meanwhile, Black and Latinx caregivers who themselves have experienced more frequent adverse childhood experiences (i.e., potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood; ACEs), higher levels of depressive symptoms, and/or lower levels of social support may be more vulnerable to the harmful effects of parenting stress (Jackson & Huang, Reference Jackson and Huang2000; Nam et al., Reference Nam, Wikoff and Sherraden2015; Steele et al., Reference Steele, Bate, Steele, Danskin, Knafo, Nikitiades, Bonuck, Meissner and Murphy2016). Parental mental health has been implicated in contributing to role-related distress, whereas difficulties with mentalizing may be more closely tied to parent-child relational stress (Steele et al., Reference Steele, Townsend and Grenyer2020).

For Black and Latinx mothers in particular, studies suggest that they may experience higher levels of parenting stress compared to White mothers (Nam et al., Reference Nam, Wikoff and Sherraden2015). This increased parenting stress among ethnoracially minoritized mothers may stem from a combination of factors such as structural disadvantages (i.e., lower economic and educational opportunities) and their child’s temperament and health (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Padilla and Sampson2010; Nam et al., Reference Nam, Wikoff and Sherraden2015). Contemporary parenting frameworks contextualize the attachment relationships between caregivers and their children within systems and cultural environments that shape parenting practices such as preparation for bias (a form of ethnic-racial socialization; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson and Spicer2006), or strategies that caregivers employ to help their child identify and confront experiences of racial discrimination (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Lozada, Ahn and Leerkes2022; Kotchick & Forehand, Reference Kotchick and Forehand2002). Given that racial discrimination may exacerbate the factors associated with parenting stress (i.e., racism-related stress as a result of discrimination may negatively influence psychological distress and perceptions of social support; structural racism contributes to structural disadvantages), it is important to understand how parents of color may be at an increased risk of parenting stress as a result of racial discrimination.

Racial discrimination and parenting stress

Heightened parenting stress among ethnoracially minoritized caregivers may be explained in part by racism-related stress stemming from experiences of racial discrimination, or unjust treatment based on an individual’s racial group affiliation (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015; Brody et al., Reference Brody, Chen, Kogan, Murry, Logan and Luo2008; Heard-Garris et al., Reference Heard-Garris, Cale, Camaj, Hamati and Dominguez2018; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018). The impact of racial discrimination may be influenced by both the frequency of experiences and the subjective distress appraisal, as both have unique effects on psychological outcomes (Sellers & Shelton, Reference Sellers and Shelton2003). Racial discrimination may lead to physiological and psychological stress responses (e.g., anger, helplessness, paranoia, resentment, fear) that influence both physical and mental health outcomes (Cave et al., Reference Cave, Cooper, Zubrick and Shepherd2020; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Anderson, Clark and Williams1999; Paradies, Reference Paradies2006; Priest et al., Reference Priest, Paradies, Trenerry, Truong, Karlsen and Kelly2013). Given that racial discrimination may compromise a caregiver’s psychosocial well-being, physical health, and their social conditions via access to societal resources, it is important to understand how racial discrimination may shape parenting stress among Black and Latinx caregivers (Nomaguchi & House, Reference Nomaguchi and House2013). Such research may improve the cultural responsiveness of caregiver-focused interventions to potentially alleviate the effect that these stressors have on both caregivers’ and their children’s psychosocial well-being.

In line with this, theoretical and empirical literature have begun to highlight the myriad ways racial discrimination impacts parenting processes among ethnoracially minoritized caregivers (e.g., Brody et al., Reference Brody, Chen, Kogan, Murry, Logan and Luo2008; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Gonzalez, Hanebutt, Bulgin, Coates, Inniss-Thompson, Debreaux, Wilson, Abel and Cortez2022). For example, longitudinal studies have found negative cascading effects of racial discrimination experiences on parenting processes and parent-child relationship quality among African American mothers through pathways of stress-related illness and maternal mental health symptoms (Brody et al., Reference Brody, Chen, Kogan, Murry, Logan and Luo2008; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Gonzalez, Hanebutt, Bulgin, Coates, Inniss-Thompson, Debreaux, Wilson, Abel and Cortez2022). Research also shows that racism-related experiences may undermine caregivers’ ability to engage in involved parenting (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015; McLoyd, Reference McLoyd1990). However, the impacts of the caregiver’s racial discrimination experiences on parenting is complex and may be influenced by their expectations of their child’s own experiences of racial discrimination. Black caregivers’ personal experiences of racial discrimination may shape involved-vigilant parenting practices (e.g., monitoring, inductive reasoning, mutual problem-solving, and consistent discipline), wherein caregivers may exert greater involvement to protect their children who are themselves experiencing racial bias (Rowley et al., Reference Rowley, Helaire and Banerjee2010; Varner et al., Reference Varner, Hou, Ross, Hurd and Mattis2020). Thus, caregivers’ personal experiences of racial discrimination may be carried forward as fear for one’s children and awareness of the need to protect and prepare Black youth for discriminatory encounters.

These burdens held by caregivers further highlight the potentially deleterious impact of racial discrimination on parenting stress, yet this direct link remains understudied. More specifically, previous studies have predominantly explored the negative impact of racial discrimination on parenting practices or processes (e.g., parenting styles; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Gonzalez, Hanebutt, Bulgin, Coates, Inniss-Thompson, Debreaux, Wilson, Abel and Cortez2022), but less so the burdens that racial discrimination experiences may add to caregivers’ stress specific to the parenting role. In one existing study, maternal experiences of racial discrimination were associated with increased parenting stress, but unassociated with parenting styles (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Barcelona, Ibrahim, Crusto and Taylor2022). Taken together, more work is needed to further clarify the associations between racial discrimination and parenting stress specifically, and to explore potential interventions for alleviating these negative effects. Given that caregiver experiences of racial discrimination are conceptualized to impact the psychological functioning and adjustment of both caregivers and their children (Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018), it is also important to explore how the effects of these experiences may be transmitted intergenerationally.

Intergenerational effects of racial discrimination on psychological well-being

Considering the well-documented caregiver-to-child stress transmission, and the links between racial discrimination and parenting stress, racism-related experiences may impact both caregivers’ and their children’s psychological well-being. For example, parenting stress directly influences caregiver-child relationships (e.g., Östberg et al., Reference Östberg, Hagekull and Hagelin2007), and these relationships have profound implications for the socioemotional outcomes of children (e.g., Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Russo, Arreola, Cervantes, Hecht, Leal, Montiel, Paredes and Guerra2021). Moreover, higher levels of parenting stress have been associated with higher counts of ACEs among children (Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Radcliff, Brown and Hung2019). In fact, racial discrimination may be akin to a racism-related ACE, underscoring the intergenerational link between racism-related stress and caregivers’ and their children’s psychosocial outcomes (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Calhoun, Banks, Halliday, Hughes-Halbert and Danielson2020). The chronic stress associated with interpersonal and institutional racism may add undue burdens that require unique support as parenting demands are context specific. Longitudinal studies show that direct and vicarious experiences of racial discrimination may increase psychological distress (e.g., symptoms of depression and anxiety) among mothers, and that these experiences negatively impact their children’s socioemotional development and adjustment (e.g., conduct problems, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, peer problems, and prosocial behaviors; Bécares et al., Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Kelly2015, Murry et al., Reference Murry, Gonzalez, Hanebutt, Bulgin, Coates, Inniss-Thompson, Debreaux, Wilson, Abel and Cortez2022). Importantly, experiences of racial discrimination among caregivers have been indirectly linked to children’s emotional problems through parental depressive symptoms and parenting practices (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015).

Taken together, these findings highlight how caregivers’ experiences of racial discrimination may influence their children’s psychosocial functioning through several pathways. A limitation in the literature to date is that less is known about the direct, unique impact of racial discrimination on parenting stress, as many studies have focused on the mediating role of parenting practices and parental psychological distress (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015; Heard-Garris et al., Reference Heard-Garris, Cale, Camaj, Hamati and Dominguez2018), or have looked at the impact of racial discrimination on parenting practices but not parenting stress (i.e., Murry et al., Reference Murry, Gonzalez, Hanebutt, Bulgin, Coates, Inniss-Thompson, Debreaux, Wilson, Abel and Cortez2022). Furthermore, to alleviate the negative impact of such stressors on the psychosocial functioning of ethnoracially minoritized families, there is an urgent need for interventions to address both parenting and racism-related stress as a result of racial discrimination among these groups.

Potential intervention for helping underserved communities cope with parenting stress and racial discrimination: the Connecting and Reflecting Experience (CARE)

Attachment security is theorized to contribute to internal resources for coping with adverse life experiences and to promote positive mental health outcomes through emotion regulation capacities, sense of self-worth, and interpersonal connectedness (e.g., Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Russo, Arreola, Cervantes, Hecht, Leal, Montiel, Paredes and Guerra2021; Lockhart et al., Reference Lockhart, Phillips, Bolland, Delgado, Tietjen and Bolland2017). To best support Black and Latinx caregivers experiencing parenting stress in the context of racial discrimination, it may be critical to consider both their own internalization of and access to secure relationships, as well as their capacity to foster secure attachment with their own children (Mikulincer & Shaver, Reference Mikulincer and Shaver2022). Interventions that target parenting stress by fostering a safe collective space for caregivers to reflect upon emotional interpersonal experiences and strengthen attachment security may have as yet untested secondary benefits on stress associated with racial discrimination.

One such potential program is the Connecting and Reflecting Experience (CARE), a group-based adaptation of “Mothering from the Inside Out,” developed by Suchman (Reference Suchman2016). CARE is a short-term, transdiagnostic, bigenerational, mentalizing-focused group parenting intervention specifically developed within a community facing racial-ethnic disparities in healthcare outcomes and access to quality care (see Zayde et al., Reference Zayde, Prout, Kilbride and Kufferath-Lin2021). CARE targets caregivers’ capacity for mentalizing, or recognizing and reflecting upon one’s own and their child’s internal experiences and related behaviors (Steele et al., Reference Steele, Murphy and Steele2015). Parental mentalizing may strengthen emotion regulation during high-stress parenting moments and mitigate the intergenerational transmission of interpersonal trauma by promoting sensitive parenting (Zayde et al., Reference Zayde, Prout, Kilbride and Kufferath-Lin2021). Further, caregivers’ capacity to mentalize is thought to create a safe and attuned environment that promotes secure attachment, healthy psychosocial development, and psychological resilience in the child (Luyten et al., Reference Luyten, Campbell, Allison and Fonagy2020). Group-based mentalizing interventions have yielded improvements in maternal supportive presence, as well as reductions in maternal emotion dysregulation and parenting stress (e.g., Lavender et al., Reference Lavender, Waters and Hobson2023; Steele et al., Reference Steele, Murphy, Bonuck, Meissner and Steele2019). Initial studies suggest emotional and relational benefits for both caregivers and youth with the CARE program specifically (Zayde et al., Reference Zayde, Kilbride, Kucer, Willis, Nikitiades, Alpert and Gabbay2022, 2023).

To our knowledge, only one study to date has tested the buffering effects of mentalizing-focused interventions on racism-related outcomes. For an individual home-visiting intervention delivered in infancy, findings were inconclusive regarding treatment effects on children’s longitudinal outcomes related to mothers’ racial discrimination experiences (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Londono Tobon, Jackson, Holland, Slade, Mayes and Sadler2021). Similar to this intervention, racism-related experiences were not the predetermined focus of CARE. However, the content discussed in group sessions were caregiver-driven; CARE’s mentalizing approach is flexible and responsive to experiences identified as salient to the parenting role, including racism-related incidents like racial discrimination. Further, in the group-based CARE model, facilitators scaffold a collaborative process by which caregivers reflect together on their own, their children’s, and other group members’ mental states, behaviors, relational histories, and current stressors (Lowell et al., Reference Lowell, Peacock-Chambers, Zayde, DeCoste, McMahon and Suchman2021; Zayde et al., Reference Zayde, Prout, Kilbride and Kufferath-Lin2021). The CARE group framework may thus allow for collective processing of both parenting stress and experiences of racial discrimination (Zayde et al., Reference Zayde, Prout, Kilbride and Kufferath-Lin2021), which may yield stronger outcomes related to racism-related stress for caregivers and their children relative to those seen in individual treatment models with more traditional clinician-patient hierarchies (e.g., Condon et al., Reference Condon, Londono Tobon, Jackson, Holland, Slade, Mayes and Sadler2021). Given that previous studies have found that individual coping strategies may not buffer the negative impact of caregivers’ racial discrimination on their parenting stress (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Barcelona, Ibrahim, Crusto and Taylor2022), the CARE program may be uniquely situated to further support and enhance ethnoracially minoritized caregivers’ existing coping strategies for navigating racism-related and other social and environmental stressors.

CARE may further support Black and Latinx caregivers by reducing social isolation and promoting a sense of belonging, safety, and connectedness with other adults through the resonance of shared experiences, the exchange of mutual care, validation, and resources, and the affirmation of each other’s strengths. This is important given the previously mentioned benefits of secure relationships for coping with adversity (e.g., Mikulincer & Shaver, Reference Mikulincer and Shaver2022). Additionally, greater social support and sense of belonging are associated with lower parenting stress for Black and Mexican American mothers (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Padilla and Sampson2010), and social support has been identified as a buffering mechanism against the psychological harms of racism-related stress (e.g., Williams et al., Reference Williams, Erving, Gao, Mitchell, Muwele, Martin, Blasingame and Jennings2023).

Finally, in situ adaptations (i.e., adaptations made during clinical practice to meet the perceived needs of participants; Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Berkel and Castro2017) have been implemented to enhance the cultural responsiveness of CARE. For instance, CARE clinicians are encouraged to acknowledge local or national events that may impact caregivers’ mental states and parenting experiences, including highly publicized incidents of violence against ethnoracially minoritized communities. CARE clinicians are also encouraged to be transparent about their own positionality and values and commitment to social justice. Although CARE aims to facilitate mentalizing in culturally responsive ways and initial findings suggest high engagement of Black and Latinx caregivers in previous telehealth groups (Zayde et al., Reference Zayde, Kilbride, Kucer, Willis, Nikitiades, Alpert and Gabbay2022), the impact of CARE on caregivers’ racism-related stress has yet to be specifically tested and warrants further investigation.

Current study

The current study aimed to clarify the association between experiences of racial discrimination (i.e., frequency, distress), parenting stress, and psychological distress in caregivers and their children. In line with theoretical frameworks and existing literature that highlight the harmful impacts of racism-related stress on psychological outcomes of ethnoracially minoritized caregivers and their families (i.e., Clark et al., Reference Clark, Anderson, Clark and Williams1999; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018; Brody et al., Reference Brody, Chen, Kogan, Murry, Logan and Luo2008; Murry et al., Reference Murry, Gonzalez, Hanebutt, Bulgin, Coates, Inniss-Thompson, Debreaux, Wilson, Abel and Cortez2022), we hypothesized that more frequent experiences of racial discrimination and higher levels of racial discrimination distress among caregivers would be significantly associated with higher levels of parenting stress and psychological distress pre-treatment. Given that there are both individual and dyadic components of parenting stress (Abidin, Reference Abidin1992; Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard1998), an exploratory aim of this study was to also assess whether racial discrimination was differentially associated with certain components of parenting stress relative to others (e.g., perceptions of one’s child). We also hypothesized that higher levels of racial discrimination among caregivers would be associated with higher levels of psychological distress among their children.

Lastly, the current study explored whether participation in a 12-session protocol of CARE shaped changes in racial discrimination distress. As described, CARE offers caregivers a flexible, collaborative space in which to mentalize challenging parenting experiences, including experiences of racial discrimination, and to both give and receive social support to adult peers. In situ adaptations may have further promoted group discussion of and responsiveness to racism-related stress during the study period. In this way, in addition to the strengths-based cultural assets ethnoracially minoritized families utilize to navigate stressors (Murry et al., Reference Murry, Butler-Barnes, Mayo-Gamble and Inniss-Thompson2018), CARE may further support positive development in these families by both reducing the impact of racism-related stress and improving the parent-child relationship. Thus, we hypothesized that distress from racial discrimination experiences would be significantly lower from pre- to post-treatment for the CARE intervention group, but not for the treatment-as-usual (TAU) group.

Method

Procedure

A longitudinal quasi-experimental clinical trial was conducted with caregivers of children enrolled in outpatient mental health services at a community clinic within a large metropolitan academic medical center in an under-resourced neighborhood in the Northeast US. Caregiver-child dyads (i.e., child aged 5-17 years) were recruited by research staff or referred by treating clinicians for participation based on reports or observations of caregiver-child relational stress. To be included in the study, participants had to be proficient in either English or Spanish, have access to a phone (all participants had video telehealth-capable devices, though this was not required), and could not be in acute risk or in need of a higher level of care at the beginning of the study. Following eligibility screening, caregivers were assigned to the CARE intervention or TAU conditions based on availability to participate in group sessions. All participants gave informed consent to procedures, which were approved by the institutional review board of the academic medical center; the study was also registered at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Treatment

In the current study, assignment to the CARE intervention condition consisted of 12 weekly, hour-long group sessions including five to six caregivers, as well as three monthly caregiver-child dyadic sessions, all conducted via the Zoom telehealth platform. Facilitators were advanced mental health clinicians (i.e., licensed social workers and psychologists and postdoctoral fellows) trained onsite and receiving weekly reflective group supervision in the CARE program. Dyads allocated to TAU continued to engage in outpatient mental health treatment as indicated by their primary clinician, typically involving individual child psychotherapy and/or medication management with a psychiatrist.

Data were collected from October 2020 to January 2022. Caregivers and children completed surveys at baseline (T1) and approximately three months later (T2). To minimize reading burden and provide item clarification when needed, research staff administered participant questionnaires verbally via a telehealth video platform or by phone. Caregivers completed measures across two 1-hour sessions, while the single child visit lasted 30 minutes. Caregiver and child assessments were conducted separately to promote privacy of responses. Measures were administered in English (n = 64 caregivers, 39 youth) or Spanish (n = 6 caregivers, 2 youth) depending on caregiver and child preference.

Participants

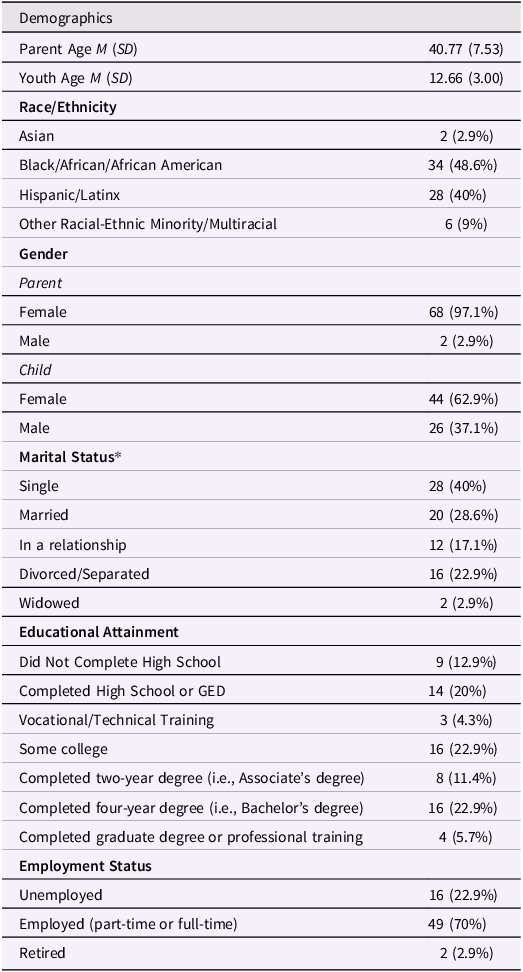

Given the current study’s focus on experiences of racial discrimination, adult participants who self-identified as non-Latinx White were excluded from the study, leaving an analytic sample of 70 caregivers at baseline. Among these caregiver-child dyads, 41 youth were between the ages of 12 to 17 years and completed T1 self-report measures. Demographic information regarding age, race, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education attainment, employment status, and household income are provided in Table 1. The sample was predominantly Black/African American or Latinx, female, single, with some college, employed, and living near or below the New York City poverty threshold.

Table 1. Sample characteristics of N = 70 caregiver-child dyads

The vast majority of caregivers were the biological parents of the youth enrolled in the study (n = 65, 92.9%). Number of children living in the home ranged from one to seven (M = 2.46, SD = 1.26), inclusive of non-biological, multi-generational, and step-children.

Almost half of the caregivers (n = 32, 45.7%) reported ever having received psychiatric treatment, with 22.9% currently in treatment (n = 16).

Regarding intervention assignment among participants included in the current study, 43 caregiver-youth dyads were allocated to the CARE condition and 27 were maintained in TAU. Within the CARE condition, the average group session dose was 7.40 of 12 sessions (0 to 3 sessions: 23.3%; 4 to 8 sessions: 27.9%; 9 to 12 sessions: 48.8%; SD = 3.9). Of the total sample, 74.3% (n = 52) was retained for T2 follow-up on at least some measures. Retention was comparable across groups (CARE: 72.1%, n = 31 of 43; TAU: 77.8%, 21 of 27). Across groups, missing all data at follow-up was associated with younger caregiver age, r s (68) = −.30, p = .011, having fewer children in the household, r s (68) = −.25, p = .034, and higher baseline levels of caregiver-reported youth symptoms, r pb (68) = .40, p < .001. Of the CARE condition caregivers with no follow-up data (n = 12 of 43), 75% had attended three or fewer sessions.

Measures

Caregiver experiences of racial discrimination

The Daily Life Experiences subscale of the Racism and Life Experiences Scale (Harrell, Reference Harrell1997) was used to index participants’ exposure to 20 discriminatory behaviors or microaggressions related to their race or ethnicity (e.g., “Others reacting to you as if they were afraid or intimidated,” “Others expecting your work to be inferior”). Participants endorsed how often each experience had occurred over the past year, with a range of options from 0 (never) to 5 (once a week or more), contributing to a mean discrimination frequency score that has demonstrated unidimensional scaling with good reliability and construct validity among Black adults (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Gaskin-Wasson, Jones, Harrell, Banks, Kohn-Wood, Sellers and Neblett2021) and adolescents (Seaton et al., Reference Seaton, Yip and Sellers2009). Participants also rated how much each experience bothers them on a rating scale ranging from 0 (has never happened to me) to 5 (bothers me extremely), generating a mean score of racial discrimination distress, which has also been found to have strong internal consistency and is predicted by higher levels of discrimination frequency (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Gaskin-Wasson, Jones, Harrell, Banks, Kohn-Wood, Sellers and Neblett2021). Comparable to prior studies, internal reliability in the current sample was excellent (Frequency: T1 and T2 α = .93; Stress: T1 and T2 α = .94).

Parenting stress

The Parenting Stress Index – Short Form, 4 th edition (PSI-4-SF; Abidin, Reference Abidin2012) is a 36-item self-report measure designed to capture three domains of parenting stress, with most items measured on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Parental Distress (PD) subscale assesses the caregiver’s level of internal distress in their role as a parent, including perceptions of limited competence and social support, and stressors and restrictions associated with the parenting role (12 items; e.g., “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent”). On the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction subscale, high scores suggest that a caregiver is not experiencing interactions with the child as reinforcing or enjoyable, and that the child and the caregiver-child bond may not meet the caregiver’s expectations (12 items; e.g., “My child rarely does things for me that make me feel good”). The Difficult Child (DC) subscale captures behavioral and temperamental characteristics of the child that may be challenging for caregivers to manage (12 items; e.g., “I feel that my child is very moody and easily upset”).

The PSI is one of the most widely used measures of parenting stress, particularly in studies of caregivers of children with emotional or behavioral health challenges (Barroso et al., Reference Barroso, Mendez, Graziano and Bagner2018). The measure demonstrated strong reliability and validity in the standardization sample (Abidin, Reference Abidin2012) and among caregivers of color (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Gopalan and Harrington2016). In the current study, total score and subscale internal consistencies were good across timepoints (Total: T1 α = .92, T2 = .93; PD: T1 α = .86, T2 = .89; Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction: T1 α = .80, T2 = .82; DC: T1 α = .84, T2 = .88).

Caregivers’ psychological distress

Participants completed the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, Reference Derogatis2001) as a short-form measure of psychological distress. Likert ratings of the 18 items indicate how bothersome each symptom has been in the past week, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The BSI-18 offers subscale scores for anxiety, depression, and somatization; however, in the current study, the global severity index was used to capture overall symptom severity. The BSI-18 has demonstrated strong internal consistency in samples of adults in outpatient treatment (Meijer et al., Reference Meijer, de Vries and van Bruggen2011) and of Latina and Black mothers (Prelow et al., Reference Prelow, Weaver, Swenson and Bowman2005; Wiesner et al., Reference Wiesner, Chen, Windle, Elliott, Grunbaum, Kanouse and Schuster2010), as well as sensitivity to change following parenting treatment (Raouna et al., Reference Raouna, Malcom, Ibrahim and MacBeth2021). Higher BSI-18 scores have previously been linked to greater psychosocial stressors (Prelow et al., Reference Prelow, Weaver, Swenson and Bowman2005), Latina acculturative stress (Da Silva et al., Reference Da Silva, Dillon, Verdejo, Sanchez and De La Rosa2017), and perceived discrimination among Black (Odom & Vernon-Feagans, Reference Odom and Vernon-Feagans2010) and Latinx adults (Moradi & Risco, Reference Moradi and Risco2006). Consistent with similar samples (Asner-Self et al., Reference Asner-Self, Schreiber and Marotta2006; Meijer et al., Reference Meijer, de Vries and van Bruggen2011; Prelow et al., Reference Prelow, Weaver, Swenson and Bowman2005), scale scores in the present sample demonstrated strong internal reliability (T1 α = .93, T2 = .92).

Child psychological distress

Caregivers of all children and adolescents completed the parent report, 30-item version of the Youth Outcome Questionnaire (Y-OQ-30.2; Burlingame et al., Reference Burlingame, Dunn, Hill, Cox, Wells, Lambert and Brown2004) to measure children’s psychological distress. Caregivers rated the frequency in the past week of their child’s behavioral problems, emotional distress symptoms, and interpersonal relationship difficulties, with item scores ranging from 0 (Never or almost never) to 4 (Always or almost always). Children ages 12 years and older (i.e., N = 41 of 70 total participating families) completed the parallel self-report version of the scale (Y-OQ-SR). The measure exhibits high sensitivity to detect change across treatment (McClendon et al., Reference McClendon, Warren, Green, Burlingame, Eggett and McClendon2011), and both the caregiver (Burlingame et al., Reference Burlingame, Cox, Wells, Latkowski, Justice, Carter and Lambert2005) and self-report versions (Ridge et al., Reference Ridge, Warren, Burlingame, Wells and Tumblin2009) demonstrate strong internal consistency and convergent validity. Total scale scores were used in the current study as a measure of overall symptom severity and demonstrated strong internal reliability (Caregiver-report: T1 α = .88, T2 = .92; Self-report: T1 α = .87, T2 = .94).

Analytic plan

Bivariate correlations were first examined for caregivers’ experiences of racial discrimination, parenting stress, caregivers’ psychological functioning, and child psychological functioning at T1 and T2 for participants in both the CARE and TAU groups. Multiple linear regressions were used to explore the concurrent relation between racial discrimination, parenting stress (and its three subscales), caregivers’ psychological distress, and child psychological distress. Caregivers’ age, household income, and number of children were used as covariates in each model. For each multiple regression model, linearity was assessed by partial regression plots and a plot of studentized residuals against the predicted values.

There was independence of residuals, as assessed by Durbin-Watson statistics between 1.93 and 2.17 in all models. There was homoscedasticity, as assessed by visual inspection of a plot of studentized residuals versus unstandardized predicted values in each model. There was no evidence of multicollinearity in each model, as assessed by tolerance values greater than 0.1. There were no studentized deleted residuals greater than±3 standard deviations, no leverage values greater than 0.2, and values for Cook’s distance above 1 in all models. The assumption of normality was met for each model, as assessed by a Q-Q Plot. Finally, paired samples t-tests were used to explore if distress related to racial discrimination decreased after participation in a 12-week mentalizing-focused group parenting intervention among both the CARE and TAU groups.

Results

Preliminary analyses

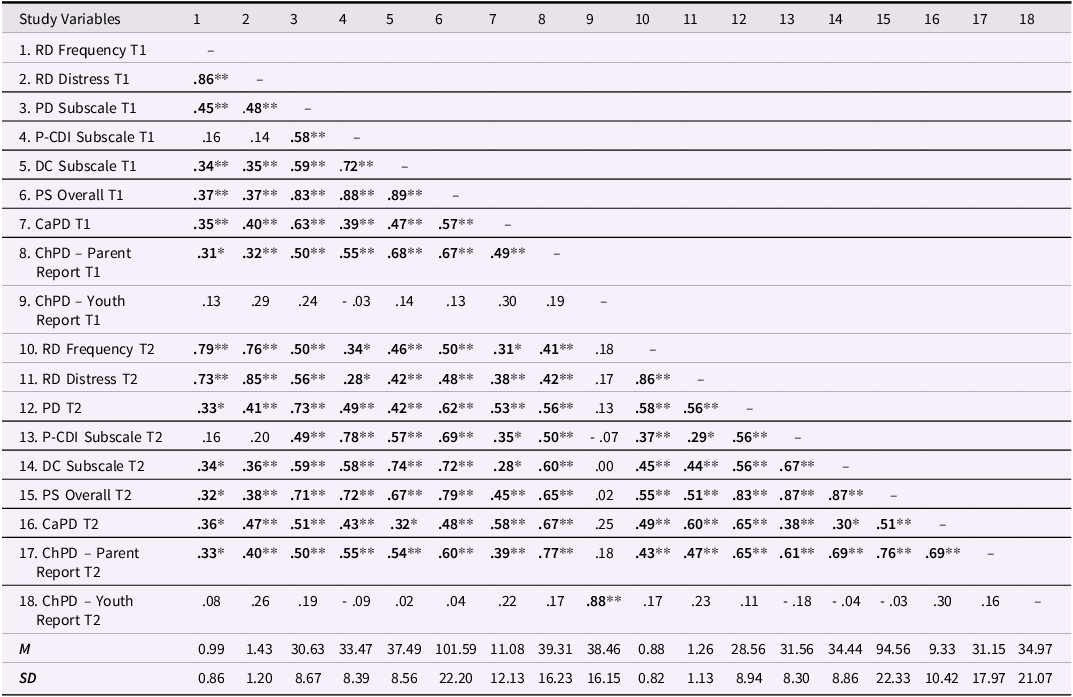

Descriptive statistics (i.e., correlations, means, and standard deviations) for key study variables are summarized in Table 2. Findings from the bivariate analyses show that at baseline, more frequent experiences of racial discrimination were related to higher levels of parenting stress, caregiver psychological distress, and caregiver-report of their child’s psychological distress. Similarly, higher levels of the caregiver’s racial discrimination distress were related to higher levels of parenting stress, caregiver psychological distress, and child’s psychological distress as reported by the caregiver. In observing relationships between T1 and T2 variables, both frequency of and distress from racial discrimination at T1 remained related to parenting stress, caregivers’ psychological distress, and caregiver-report of their child’s psychological distress at T2.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variable

Note. T1 = Baseline Assessment; T2 = Follow-up Assessment, RD = Racial Discrimination; PD = Parental Distress; P-CDI = DC = Difficult Child; PS = Parental Stress; Parent-Child Difficult Interaction; CaPD = Caregiver Psychological Distress; ChPD = Child Psychological Distress. *p < .05 level (2-tailed); ** p < 01 level (2-tailed).

Racial discrimination frequency, parenting stress, caregiver and child psychological distress

Results of the significant multiple regression models predicting parenting stress outcomes (for T1 only) from racial discrimination frequency and covariates (caregiver’s age, household income, and number of children) are displayed on Table 3. First, the model of racial discrimination frequency predicting overall concurrent levels of parenting stress was significant, F(4, 55) = 3.99, p = .006, adj. R 2 = .17. Specifically, more frequent experiences of racial discrimination were associated with higher overall levels of parenting stress, B = 10.28, p = .003. With respect to our exploratory aim, when explored by subscale, more frequent racial discrimination experiences were associated with higher levels of parental role-related distress, B = 4.28, p < .001; F(4, 55) = 4.89, p = .002, adj. R 2 = .21. These experiences were also associated with increased perceptions of their child being difficult, B = 4.20, p = .002; F(4, 55) = 3.09, p = .023, adj. R 2 = .12. In contrast, the frequency of racial discrimination experiences were not associated with ratings of parent-child difficult interactions, B = 1.80, p = .18; F(4, 55) = 2.09, p = .10, adj. R 2 = .07.

Table 3. Multiple regression models of racial discrimination frequency and covariates predicting parenting stress overall, parenting distress subscale, and child psychological distress parent report

Note. RD = Racial Discrimination; B = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error; ** p < .01; *p = < .05.

Next, the model exploring the relationship between the frequency of racial discrimination experiences and caregivers’ concurrent psychological distress was trending, B = 4.22, p = .03; F(4, 55) = 2.23, p = .08, adj. R 2 = .08. On the other hand, more frequent experiences of racial discrimination experienced by caregivers were significantly associated with caregivers’ reports of their child’s psychological distress, F(4, 55) = 2.95, p = .03, adj. R 2 = .12. Specifically, more frequent experiences of racial discrimination experienced by caregivers were associated with higher ratings of their child’s psychological distress, B = 6.84, p = .009, though not with self-reports of youth’s own psychological distress within the smaller sample of adolescent participants, B = 1.72, p = .58; F(4, 33) = 0.39, p = .39, adj. R 2 = .01.

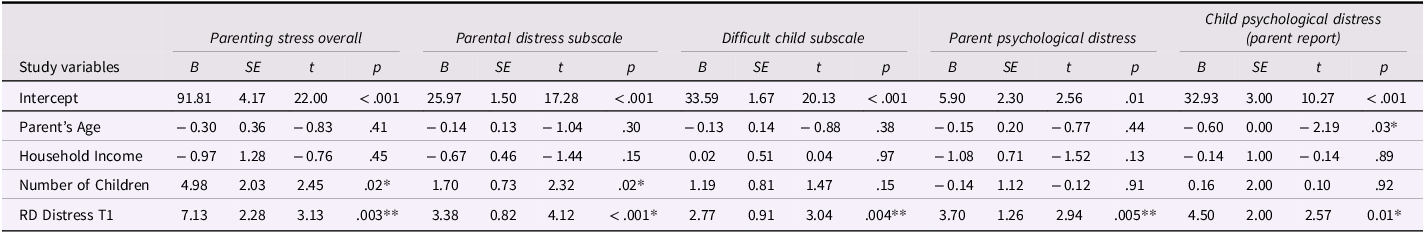

Racial discrimination distress, parenting stress, caregiver and child psychological distress

Results of the significant multiple regression models predicting parenting stress outcomes (for T1 only) from racial discrimination distress and covariates (caregiver’s age, household income, and number of children) can be found on Table 4. Similarly to above, racial discrimination distress was significantly associated with overall levels of parenting stress, F(4, 55) = 4.01, p = .006, adj. R 2 = .17, such that more distressing experiences of racial discrimination were associated with higher overall levels of parenting stress, B = 7.13, p = .003. When examined by subscales, more distressing experiences of racial discrimination were associated with higher levels of parental distress, B = 3.38, p < .001; F(4, 55) = 6.22, p < .001, adj. R 2 = .26, and increased perceptions of their child being difficult, B = 2.77, p = .004; F(4, 55) = 2.79, p = .04, adj. R 2 = .11. Despite this, distress from racial discrimination was not associated with ratings of parent-child difficult interactions, B = 0.98, p = .30; F(4, 55) = 1.89, p = .13, adj. R 2 = .06.

Table 4. Multiple regression models of racial discrimination distress and covariates predicting overall parenting stress, parental distress subscale, parent psychological distress, and child psychological distress parent report

Note. RD = Racial Discrimination; B = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error; ** p < .01; *p = < .05.

Next, racial discrimination distress was associated with caregivers’ psychological distress, F(4, 55) = 3.17, p = .02, adj. R 2 = .13. More specifically, higher levels of distress from racial discrimination experiences were associated with higher levels of psychological distress among caregivers, B = 3.70, p = .005. Lastly, higher levels of distress from racial discrimination experienced by caregivers were associated with caregivers’ reports of their children’s psychological distress, F(4, 55) = 2.73, p = .04, adj. R 2 = .11. Specifically, higher reports of distress from experiences of racial discrimination experienced by caregivers were associated with higher levels of children’s psychological distress as reported by their caregiver, B = 4.50, p = .01, though not with youths’ reports of their own psychological distress among the adolescent participants, B = 3.21, p = .12; F(4, 33) = 1.71, p = .17, adj. R 2 = .07.

Changes in racial discrimination distress, parental distress, and caregivers’ psychological distress after treatment

Findings from the paired sample t-tests for the intervention group showed no significant mean difference in distress from racial discrimination between T1 (M = 1.75, SD = 1.21) and T2 [M = 1.57, SD = 1.19; t(29) = 1.48, p = .15]. Regarding the TAU group, paired sample t-tests revealed that there were no significant mean differences between T1 (M = 0.92, SD = 1.02) and T2 (M = 0.78, SD = 0.84) for racial discrimination distress, t(19) = 1.48, p = .37.

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore the relationships between the frequency of, and distress from, experiences of racial discrimination, parenting stress, and psychological distress among ethnoracially minoritized caregivers and children. First, in line with our hypothesis, the findings showed that more frequent experiences of racial discrimination, and higher reports of distress from these experiences, were associated with higher levels of overall parenting stress and parental distress specifically. These findings are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Condon et al., Reference Condon, Barcelona, Ibrahim, Crusto and Taylor2022; Varner et al., Reference Varner, Hou, Ross, Hurd and Mattis2020) that have found that distress related to parenting is exacerbated by experiences of racial discrimination among ethnoracially minoritized caregivers. Both the occurrence of and subjective distress from these experiences likely increase the stress associated with parenting among this population, as caregivers have to not only manage the deleterious impact of these experiences on their own mental health, but these experiences also increase household stress (Berry, Reference Berry2021). Furthermore, racial discrimination may also exacerbate parenting stress given that more frequent experiences of discrimination may increase the caregivers’ expectation that their children may also experience discrimination themselves, which may lead to an increased demand of learning and engaging in parenting practices to help prepare ethnoracially minoritized youth for navigating a racialized society (i.e., Varner et al., Reference Varner, Hou, Ross, Hurd and Mattis2020). This is also likely compounded by other structural disadvantages rooted in racism that disproportionately impact ethnoracially minoritized caregivers and youth (e.g., barriers to economic and education opportunities; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Padilla and Sampson2010; Nam et al., Reference Nam, Wikoff and Sherraden2015).

Although exploratory, our findings also indicated that increases in the frequency of, and distress from, racial discrimination were associated with increases in caregiver perceptions that their child is temperamentally or behaviorally difficult. Though speculative, there are many reasons this association may exist. First, it could be that ethnoracially minoritized caregivers’ resources are more limited due to contending with the emotional impacts of racial discrimination, making it more likely that they perceive their child as demanding or taxing. Second, it could be that these caregivers, because of their own racism-related experiences, have increased worry about their children experiencing racial discrimination (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Jones, Saleem, Metzger, Anyiwo, Nisbeth, Bess, Resnicow and Stevenson2021), and therefore, have adapted their parenting styles (e.g., establishing more expectations or rules for their children, as compared to their child’s White peers), as a method to help prepare their children to navigate racism in society (i.e., Varner et al., Reference Varner, Hou, Ross, Hurd and Mattis2020). Though this strategy is meant to be protective, it could also lead to more opportunities for conflicts to occur, which could potentially influence ethnoracially minoritized caregivers’ perceptions that their child is difficult. Finally, this relationship between racial discrimination and caregivers’ perceptions of their child could be reflective of caregivers’ increased vigilance about their child’s behavior or mood given the realistic risk for their child to encounter racial discrimination (e.g., fear of hostile social responses to their children’s challenging behaviors or emotions, or fear of greater risks to their child from others in society if their child is experiencing emotional dysregulation publicly, which are all warranted due to the historical and current socio-political climate in the United States).

Contrary to our hypothesis, only racial discrimination distress was related to higher levels of caregivers’ psychological distress, though the relationship with racial discrimination frequency was trending. Previous studies support the link between racial discrimination and psychological distress among caregivers (e.g., Condon et al., Reference Condon, Barcelona, Ibrahim, Crusto and Taylor2022). Our findings suggest that it may be the subjective appraisal of these experiences specifically, though not the frequency of these experiences, that contribute to caregivers’ psychological distress. In contrast to our findings, previous studies reported associations between the frequency, and not distress, of racial discrimination and later mental health outcomes among African American adults (Sellers & Shelton, Reference Sellers and Shelton2003; Willis & Neblett, Reference Willis and Neblett2018). These findings, however, were not unique to caregivers. Additionally, it could be that distress from racial discrimination had a stronger relationship with caregivers’ psychological distress as other contextual factors (e.g., stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic, exposure to the murder of George Floyd and other racism-related events) may have exacerbated racial discrimination distress either directly or indirectly. For example, caregivers may not have had access to their social support networks to process racial discrimination distress due to quarantine, or they may have been more vulnerable to the distress associated with racial discrimination due to the compounded stress effects of the events highlighted above (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Doom, Lechuga-Peña, Watamura and Koppels2020). Another possible explanation is that the presence of parenting stress may render caregivers more vulnerable to emotional impacts of racial discrimination experiences, whereby they may perceive such experiences as more distressing than caregivers without the added burden of parenting stress.

Our second hypothesis was partially supported, such that higher levels of both racial discrimination frequency and racial discrimination distress were associated with higher levels of child’s psychological distress that were caregiver-reported, though not youth-reported. Although other studies reported associations between caregivers’ racial discrimination experiences and child’s psychological distress, these associations were mediated by other factors (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hussain, Wilson, Shaw, Dishion and Williams2015). Our study provides additional empirical evidence (i.e., Murry et al., Reference Murry, Gonzalez, Hanebutt, Bulgin, Coates, Inniss-Thompson, Debreaux, Wilson, Abel and Cortez2022) of a direct concurrent link between these two constructs that supports the intergenerational impact of caregivers’ racial discrimination experiences on their child’s psychosocial functioning. It is important to note that this association was only present for caregivers’ reports, and not the youths’ reports, of children’s psychological distress, with several potential explanations. It could be that caregivers’ perceptions of their children’s mental health is more accurate due to developmental differences (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Doherty, Cannon, Hickey, Rosenthal, Marino and Skinner2019). For example, given general discrepancies between parents’ and children’s reports of their externalizing symptoms, overall impairment, and distress (Bein et al., Reference Bein, Petrik, Saunders and Wojcik2015), it could be that children’s psychological distress levels were largely influenced by externalizing symptoms in this sample. In support of this, large-scale studies suggest that externalizing problems are more accurately reported by caregivers compared to youth (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Doherty, Cannon, Hickey, Rosenthal, Marino and Skinner2019). Alternatively, differences in associations with psychological functioning may be related to subsample characteristics, as youth self-report data was only provided by those over the age of 12 years old, whereas caregiver-report data included all children (ages 5 to 17 years). It is also important to note that since these are concurrent reports, causation or directionality of these associations cannot be determined. For instance, it could be that higher levels of distress related to racial discrimination and/or parenting may influence caregivers’ perceptions of their children’s psychological functioning, rather than these stressful experiences directly impacting children’s mental health.

Lastly, we hypothesized that the CARE intervention may help ethnoracially minoritized caregivers by reducing social isolation and promoting a sense of belonging, which is particularly important for ethnoracially minoritized mothers (i.e., Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Padilla and Sampson2010), as well as by facilitating the process of mentalizing about their own and their children’s experiences. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no significant differences in distress from racial discrimination experiences between baseline and post-treatment within either the CARE or TAU groups. While CARE was not designed to explicitly target or address caregivers’ experiences of racial discrimination, in situ adaptations were made to promote cultural responsiveness during the study period (e.g., inviting discussions about televised police violence against ethnoracially minoritized communities). Session transcripts also highlighted that caregivers often discussed experiences of racial discrimination during the group intervention (e.g., a child being called a racial slur). However, there are several possible explanations for the lack of treatment effect on racial discrimination distress.

First, it could be that mentalizing-focused group parenting interventions like CARE may need to more explicitly and regularly invite in or address experiences of racial discrimination and other racism-related stressors to be more culturally responsive to the mental health needs of ethnoracially minoritized caregivers, as also suggested by Condon et al., Reference Condon, Londono Tobon, Jackson, Holland, Slade, Mayes and Sadler2021, given their inconclusive findings. Second, as prior research has found differential treatment effects depending on clinician-client racial matching (Cabral & Smith, Reference Cabral and Smith2011), dissimilar ethnoracial identities between some clinicians, the majority of whom were non-Latinx White, and participants may have also impacted the sense of safety caregivers felt in openly discussing experiences of racial discrimination or racism-related stressors. This may also potentially highlight a need for increased training in culturally responsive practices among therapists as well as increasing the ethnoracial diversity of clinicians. While the mentalizing framework and CARE structure is flexible to caregivers’ needs and topics they identify as salient, facilitators may need to be more proactive in terms of inviting in conversations about racism and allowing caregivers to process the impacts of racism on themselves and their families. Third, while caregivers did not report incidents of racial discrimination to be less distressing following intervention, it may be that participation in CARE buffers the harmful downstream effects of racial discrimination distress on parenting stress or mental health symptoms, which could be assessed with future longitudinal follow-ups.

Limitations and future directions

The current study has many strengths and offers valuable contributions for understanding the associations between racial discrimination, parenting stress, and psychological distress among ethnoracially minoritized caregivers and their children. Nevertheless, there are important limitations that should be noted. This study was conducted within an urban, low-income area in the Northeast US with predominantly Black and Latinx caregivers, so generalizability to other geographic locations or to families from other ethnoracially minoritized backgrounds (e.g., Asian American or Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Native/Indigenous) may be limited. Despite this, the study sample did include caregivers and families that identified as Asian American, Native, among others. As a direction for future research, though, it is important to note that this study was conducted via video telehealth, so replication to other geographic locations has a high degree of feasibility utilizing the same telehealth approach.

Additionally, the majority of the caregivers in the study were women (97%). There is an urgent need for future studies to explore how the racial discrimination and parenting stress experienced by caregivers who do not identify as women may impact a child’s psychological distress. Similarly, researchers have noted that there are differences in how racial discrimination influences parenting practices, parenting stress, and child’s psychological distress based on the gender identity of the child and the caregiver (i.e., Varner et al., Reference Varner, Hou, Ross, Hurd and Mattis2020). Further research is warranted on how caregivers’ racial discrimination experiences influence their child’s psychological distress within a gendered context.

The present study was also underpowered to examine potential mediators/indirect effects, specific mechanisms of change, and potential moderating effects. Future research should identify culturally specific protective factors and moderators that may attenuate the influence of racial discrimination on both parenting stress and psychological distress in a larger sample of caregiver-child dyads. For instance, in Black families, culturally relevant processes that help their children prepare for and subsequently cope with racial discrimination are a normative experience (i.e., racial socialization, Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson and Spicer2006). Taken together, racial discrimination may both exacerbate parenting stress and prompt culturally specific protective parenting practices in minoritized caregivers. Future studies should both explore the effectiveness of these parenting practices, as well as how caregiver-focused interventions like CARE may relieve distress associated with racial discrimination or increase competency related to racial socialization practices. Racial socialization practices impact racism-related stress and outcomes (Anderson & Stevenson, Reference Anderson and Stevenson2019), thus they may have the potential to reduce both parenting and racism-related distress. Scholars have argued that interventions based on attachment theory and mentalization have not sufficiently attended to racism and discriminatory experiences that disproportionately impact ethnoracially minoritized communities (Stern et al., Reference Stern, Barbarin and Cassidy2021). Therefore, as we highlighted earlier, it is important that future mentalizing-focused group parenting interventions become more culturally responsive by directly inviting in conversation about, and subsequently addressing, racism-related stressors. Given the limited sample size, the results from the multiple regression analyses should be interpreted with caution. Despite this, our study is in line with similar intervention studies exploring the relationships between racial discrimination and parenting stress (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Londono Tobon, Jackson, Holland, Slade, Mayes and Sadler2021), and our findings are consistent with other studies that have shown the deleterious impact that racial discrimination has on parenting stress (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Barcelona, Ibrahim, Crusto and Taylor2022).

Conclusion

This study contributes to the burgeoning literature that seeks to better understand the association between racial discrimination, parenting stress, and psychological distress among ethnoracially minoritized families. Our findings suggest that racial discrimination experienced by ethnoracially minoritized caregivers may exacerbate their parenting stress and psychological distress. Further, our findings highlight the potential intergenerational impact of racism-related stress, such that racial discrimination experienced by ethnoracially minoritized caregivers was associated with higher levels of psychological distress among their children. Thus, it is imperative that mentalizing-focused parenting interventions, such as CARE, directly address racism-related stress and consider incorporating racial socialization practices to promote well-being within the context of racial and cultural stressors. Given that ethnoracially minoritized caregivers are at a high risk of experiencing both parenting stress and racial discrimination, and the harmful effects of racism-related stress on their children may even begin in utero (Heard-Garris et al., Reference Heard-Garris, Cale, Camaj, Hamati and Dominguez2018; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Anderson, Gaskin-Wasson, Sawyer, Applewhite and Metzger2020), it is critical that parenting-focused interventions address the unique mental health needs experienced by ethnoracially minoritized families in the United States.

Competing interests

None.