Introduction

Research on hegemony in international relations has argued that a hegemonic power can guarantee the stability of an international economic system. However, what happens to the system if the priorities of the hegemon itself become unstable? While the hegemon may still be in the structural position to determine the fate of the system, its priorities and behavior may be unsettled by domestic turmoil deriving from elections and their aftermath, social unrest, or the rise of new party movements. In addition to domestic factors, a change in the international environment or an external shock can make the hegemon change its priorities. In such phases, smaller states profiting from the existing system may fear that the hegemon is distracted from keeping the system stable. How do they react if they lose trust in the hegemon’s ability or will to maintain the status quo?

In search of an answer to this question, this article focuses on the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the role of northern ‘creditor states’ grouping around Germany. After its federal elections in 2017, Germany has been coping with domestic difficulties such as a shaky government coalition and a Chancellor on her way out of politics. For its fiscally conservative allies in EMU, the so-called ‘creditor states’, changes in Germany’s priorities and behavior have become harder to predict. In addition, the retreat of the USA as a reliable partner, the EU’s multiple crises, Brexit, and ultimately COVID-19 have increased the pressure on Germany to agree with France on further steps toward European integration. With regard to EMU, this implies that German concessions to France in favor of more risk sharing have become more likely. How do the fiscally conservative creditor states in the north of the eurozone react to this challenge?

While in recent years, we have seen a mushrooming literature on German hegemony in the eurozone (e.g. Bulmer and Paterson, Reference Bulmer and Paterson2019; Webber, Reference Webber2019; Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2020; Schild, Reference Schild2020), less has been written on the role of smaller states in EMU. However, the emergence of the ‘New Hanseatic League’ – a group of eight creditor countries putting forward common positions on EMU governance – shows that these states can pursue their preferences independently of Germany. Therefore, this article focuses on the role of small creditor countries in order to explain how smaller system profiteers react if a hegemon changes its priorities. In doing so, the article presents a fine-grained causal mechanism to trace how the smaller states’ reaction may result in the unleashing of centrifugal tendencies, such as the emergence of new coalitions.

Hence, the article addresses a theoretical and an empirical puzzle. Theoretically, it seeks to understand how small states in world regions or international organizations react if a hegemonic power changes its priorities. Empirically, the article aims to explain the emergence of issue-specific small-state coalitions, such as the ‘New Hansa’ or the ‘Frugal Four’, in the shadow of powerful states in the EU and EMU. The article argues that free riding on Germany’s hegemony in EMU has become less rewarding for the ‘frugal’ states. Against the background of Brexit and political developments within Germany, a (perceived) change in the hegemon’s priorities has shaken the confidence of those states that so far have benefited from the status quo in EMU. As leaving the eurozone is not a viable option for them, they need to build publicly visible coalitions in order to voice their interests. This implies that new fronts are opened and position-taking becomes more differentiated. The article illustrates its argument by focusing on the emergence of the New Hanseatic League (New Hansa). To do so, it builds on 26 semi-structured interviews that were conducted with high-ranking officials in EU institutions, Permanent Representations in Brussels, and ministries in 6 eurozone creditor state capitals.

Already in 1969, Robert Keohane pointed to the importance of smaller states as influential allies of the hegemon. Accordingly, in the realm of International Political Economy, the economic adjustment strategies of small states have been studied extensively (e.g. Katzenstein, Reference Katzenstein1985; Bohle and Jacoby, Reference Bohle and Jacoby2017). Unlike this strand of literature, the present article focuses on the diplomatic strategies that smaller states adopt to pursue their preferences in international economic affairs (e.g. Keohane, Reference Keohane1969, Reference Keohane1971; Panke, Reference Panke2012). More precisely, it traces the effect of changes in the hegemonic priorities on the behavior of smaller states. With regard to its empirical contribution, the article analyzes the New Hansa, the function of which in EMU governance has remained unclear so far. In this context, the article also addresses the changing power relations in the EU after Brexit, which has seen the rise of new small-state coalitions (e.g. the ‘Frugal Four’ in COVID-19 management, see also Wivel and Thorhallsson, Reference Wivel, Thorhallsson, Diamond, Nedergaard and Rosamond2018; Schulz and Henökl, Reference Schulz and Henökl2020). Indeed, whereas smaller creditor states like the Netherlands used to gather behind Germany, which represented their common position in EMU matters, they are now pursuing their interests through their own coalitions without Germany.

To begin with, the article briefly revisits the relevant propositions of HST regarding the role of smaller states. Taking into account the criticism raised against classical HST, the article then draws the implications for the eurozone and derives a theoretical expectation on how smaller states react to a change in the hegemon’s priorities. Based on this conjecture, the article proceeds to elaborate on a fine-grained causal mechanism and its observational implications. The empirical analysis applies the causal mechanism to the role of small creditor states in EMU and, in particular, to the emergence of the New Hansa. The conclusions serve to summarize the argument and reflect on the implications for eurozone politics and future EMU reform.

Hegemony and the role of smaller states

HST postulates that ‘the existence of a hegemonic or dominant liberal power is a necessary (albeit not a sufficient) condition for the full development of a world market economy’ (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1987: 86). The original exponents of HST, such as Charles Kindleberger (Reference Kindleberger1973, Reference Kindleberger1981) and Robert Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1982, Reference Gilpin1987), thus argued that a hegemon can provide stability, but it is neither sufficient nor bound to bring about a stable international system. Hence, the label ‘Hegemonic Stability Theory’ can be misleading in the sense that it suggests an automatic relationship between hegemony and stability (Gavris, Reference Gavris2019). By contrast, a hegemonic state may also use its structural power to change an existing system. What is crucial, however, is that the behavior of a hegemon is systemically relevant, since this criterion distinguishes a hegemon from other powerful actors.

While HST was devised to explain the stability or change of the global system, it can also be applied at the regional level. Walter Mattli (Reference Mattli1999) argued that a powerful state is a condition for successful regional integration as it can solve coordination problems among states and ease their distributional tensions. With regard to monetary alliances, Benjamin Cohen (Reference Cohen1998) found that the most important factor preventing free riding or the exit of single states is the presence of a local hegemon. More recently, Simon Bulmer and William Paterson (Reference Bulmer and Paterson2019) examined the role of Germany in the European Union (EU) from an HST perspective, Douglas Webber (Reference Webber2019) applied the theory to Germany’s role in European (dis)integration, and Matthias Matthijs (Reference Matthijs2020) compared USA hegemony in the global financial crisis to German hegemony in the eurozone crisis.

A crucial distinction in HST differentiates between benign and coercive hegemony. Charles Kindleberger (Reference Kindleberger1981) conceptualized a benign hegemon that bears an extra share of costs in order to keep the system stable. Other versions of HST considered the possibility of a coercive hegemon that forces other states into making contributions to maintain the system (Gilpin, 1982, Reference Gilpin1987: 76, 89; Snidal, Reference Snidal1985: 585–590). Importantly, this coercive element does not refer to the participation of other member states in the system, which fulfills a common purpose and is therefore voluntary. Instead, ‘coercion’ refers to the distribution of maintenance costs and is thus a way of overcoming free-rider dynamics (see Olson, Reference Olson1973). Be it benign or coercive, the hegemon determines the distribution of gains among the relative losers and winners from collective action (such as a monetary union). A precondition for the exercise of this hegemonic function is a superior position of power, which can be achieved through control over resources and markets or competitive advantages in production (Keohane, Reference Keohane1984: 32; Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1987: 76).

At the same time, a hegemonic power is no guarantee for system stability. Ultimately, the success of hegemony depends on the distribution of profits among smaller states. If other states begin to consider the hegemon’s actions as contrary to their interests, they become less willing to subordinate their interests to the continuation of the system (Snidal, Reference Snidal1985: 582; Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1987: 73). Even if they reluctantly continue to follow the hegemon because the costs of rebelling are higher than the costs of status quo, centrifugal forces will increasingly come to the fore (Snidal, Reference Snidal1985: 588). However, HST has not specified how and under which conditions these centrifugal tendencies unfold.

In his theory on exit, voice, and loyalty, Albert Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970) proposed two ways in which actors can react if they become dissatisfied with the provision of a private or collective good, such as a common currency. They can either ‘voice’ their preferences or ‘exit’ a common endeavor. Hence, if smaller states decide not to subordinate their preferences to the hegemon any longer, the first option consists in leaving the system (‘exit’). This option is not always available, and if it is it may be very costly. If an exit is not a viable option, smaller states can attempt to influence the actions of the hegemon (‘voice’, Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970: 33–43). The ‘voice’ strategies available to small states are manifold and range from typical bargaining strategies such as open veto threats via rhetorical action (e.g. shaming and framing) through to persuasion-based strategies such as norm entrepreneurship (for a more complete overview, see Panke, 2010: 20–29, Reference Panke2012: 317–322; Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2020c: 8–11). One of the most effective strategies, however, is to team up and build a like-minded coalition that is visible enough to be considered by the hegemon (Keohane, Reference Keohane1971: 175–179; also Panke, Reference Panke2010: 26; Deitelhoff and Wallbott, Reference Deitelhoff and Wallbott2012).

Over time, HST has attracted manifold criticism (e.g. Keohane, Reference Keohane1984; Lake, Reference Lake1993; Gavris, Reference Gavris2019). However, as one of HST’s main critics emphasized early on, rather than rejecting the theory, this should lead to further theoretical refinement based on specific causal propositions and adequate empirical tests (Lake, Reference Lake1993: 485). Hence, this article seeks to develop and empirically assess a causal proposition on how a change in the hegemon’s priorities affects the behavior of those states that have so far benefited from the status quo. In the following section, the article, therefore, draws the implications for the eurozone and formulates a testable conjecture.

Implications for the eurozone: Germany’s hegemony and smaller creditor states

When applying HST to the eurozone, the first and only actor that comes to mind as a potential hegemon is Germany (see Caporaso, forthcoming Reference Caporaso, Kim and Caporaso2022).Footnote 1 Not only can Germany rely on competitive advantages in production and superior economic resources (Crawford, Reference Crawford2007; Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2019: 79–85), but it also enjoys an ‘exorbitant privilege’ in EMU which became visible during the eurozone crisis when Germany benefitted from lower interest rates on sovereign debt, better export conditions, and an influx of skilled labor (Jacoby, Reference Jacoby, Matthijs and Blyth2015: 200–201; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2018: 44–52). Nevertheless, the assessment of whether Germany is really a hegemon in the eurozone depends on the underlying definition of hegemony and thus remains controversial (see Schild, Reference Schild2020; Caporaso, forthcoming Reference Caporaso, Kim and Caporaso2022).

This article considers Germany as a hegemon in the eurozone based on the following criteria. First, as outlined above, Germany is in a structural position of power and is thus systemically relevant for EMU. Indeed, the present EMU without Germany is hardly conceivable. Second, based on this position, Germany has been able to determine the rules of the system (while being able to ignore them itself). Germany has shaped the rules of EMU in a decisive way: the convergence criteria, the no-bailout rule, the prohibition of monetary financing, the primacy of price stability, the independence of the European Central Bank (ECB), the Stability and Growth Pact, and the Fiscal Compact all trace back to German demands (Schild, Reference Schild2020; Schoeller and Karlsson, Reference Schoeller and Karlsson2021). Third, by striving for a stable monetary union, Germany shares a social purpose (Caporaso, forthcoming Reference Caporaso, Kim and Caporaso2022), although the actual type of monetary union is controversial. Fourth, as will be outlined in greater detail below, Germany benefits asymmetrically from the system it has shaped (Jacoby, Reference Jacoby, Matthijs and Blyth2015; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2018) and is therefore willing to maintain it by either shouldering an overproportionate share of the costs or ‘coercing’ other states into adhering to its rules (e.g. Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015). As I will argue below, by acting as a coercive rather than a Kindlebergerian hegemon, Germany has indeed been able to maintain an asymmetric system in which competitive export-oriented states benefit from the domestic adjustment efforts of less competitive countries in the eurozone (see Frieden and Walter, Reference Frieden and Walter2017; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2018; Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2020).

From a collective action perspective (Olson, Reference Olson1973), the European monetary union constitutes a free-rider problem: ‘even those who do not contribute to stability cannot be excluded from the diffuse benefits of a hard currency – low interest rates, low inflation, high liquidity’ (Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2017: 39). This implies that excessive public deficits, over-high or -low collective wage agreements, or unsustainable credit expansion in single-member states can wreck the collective good. Hence, if there were no institutions, possibly kept up by a hegemon, to prevent such unsustainable developments, the less competitive eurozone countries in the south (‘debtor states’) would be predestined to become free riders. However, due to Germany’s ‘“coercive” form of rules-based leadership’ (Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2020: 2), the opposite happened. The architects of the euro, and notably Germany, anticipated that less competitive states are exposed to free-rider incentives as they may cover financing gaps through external funding rather than internal adjustment. Therefore, they established ‘anti-free-rider institutions’ such as strict fiscal rules, a prohibition of monetary financing, and a no-bailout clause. As these institutions turned out to be insufficient with the outbreak of the eurozone crisis, Germany, supported by the northern creditor states, successfully pushed for them to be reinforced (e.g. Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2019; Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2020).

However, with the institutionalization of fiscal discipline, the more competitive ‘creditor states’ moved into a free-rider position. The system granting them a persistent current account surplus, a de facto undervalued currency, low interest rates and inflation, and still decent growth due to external demand relies on the austerity efforts of the debtor states: either the debtor states maintain the common good by compensating for their lack of competitiveness through internal devaluation, or the more competitive system profiteers in the north need to share their surplus by shifting parts of their benefits to the south (the so-called ‘transfer union’ or ‘debt union’). While the debtor states have implemented painful austerity measures indeed, the creditor states have incurred only limited loans and guarantees to support the debtor states and thus prevented extensive supranational risk sharing or even a ‘transfer union’. The fact that the institutional response to the euro crisis has been designed in this asymmetric way is to a large extent a result of Germany being a creditor state itself (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015: 184–191). Acting as ‘enforcer-in-chief’ (Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2016b: 144) – or ‘coercive hegemon’ – Germany used its economic weight and de facto veto power in EMU negotiations to make sure that the bulk of maintenance costs of the euro system were allocated to the debtor states in the form of austerity measures and structural reforms (Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2020a). The smaller creditor states thus benefited from Germany’s efforts to maintain a system that asymmetrically favored the more competitive states in the north of the eurozone.

However, if smaller states ‘begin to regard the actions of the hegemon as … contrary to their own political and economic interests’ (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1987: 73), they may set out to challenge the hegemon. With regard to Germany, the weakening of Chancellor Merkel after the federal election in 2017, her resignation from the party’s chairmanship, uncertainty about her successor, the protracted government formation in 2017/18 and so the inability to make meaningful decisions in Brussels, the quarrelsome government coalition, and not least the change in the Finance Ministry, where the experienced ordoliberal Schäuble was substituted by the social democrat Scholz, have therefore invoked centrifugal tendencies in the eurozone. More precisely, small creditor states started to fear that Germany would no longer be able or willing to represent their interests when it comes to avoiding ‘a gradual move toward a eurozone transfer regime’ (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2018: 79).

The feared change in German positions regards primarily concessions to France, which advocates more risk sharing in the eurozone. In particular, the German Social Democrats made a more accommodating approach toward France one of their core policy goals in the coalition agreement. In addition, the retreat of the USA under then-President Trump as a reliable partner for the EU increased the need for a common external position, which makes Germany more dependent on collaboration with France (Interview BRU7). Above all, however, Brexit led to a power shift: Britain’s exit increased the relative weight of Germany and France and thus the chance that EU politics will be affected even more than before by Franco–German compromises.

Therefore, smaller creditor states may see their benefits as being at risk. So far, these benefits have resulted from a hegemonic Germany being a creditor state itself. However, as Germany has experienced domestic and international changes and compromises with France have become more likely, other creditor states can no longer rely on the hegemon, but need to act themselves. As outlined above, they have two options to do so: exit or voice. In practice, however, exit is not a real option. EMU not only lacks a legal exit option and a corresponding procedure, the costs of leaving the eurozone are also prohibitively high. The eurozone creditor states would lose a stable currency and a liquid financial market, and they would have to face a steep appreciation of their own currency, a concurrent decline in exports and most probably a sustained recession. Moreover, they would suffer the negative externalities of their own exit, as the euro would lose value as an anchor of financial and commercial stability in Europe. The political and diplomatic consequences of an exit from the eurozone would come on top. In short, as free riding becomes less rewarding but exit is not a real option, small creditor states have to ‘voice’ their preferences. One way of doing this is by building like-minded coalitions and ‘playing the public’ (Keohane, Reference Keohane1971: 175–179).

Hence, the propositions of HST and their implications for the eurozone allow us to formulate a conjecture on how smaller allies will react if the hegemon changes its priorities or behavior: if political changes in the hegemonic states or developments in its international environment lead to a perceived or actual change in the hegemon’s priorities, smaller states profiting from the status quo will build like-minded coalitions and make their dissenting voices public. In order to probe the plausibility of this proposition in the case of current eurozone politics, the underlying causal mechanism and its observational implications are made explicit in the following section.

Methodology and causal mechanism

In order to probe the plausibility of its argument, this article relies on ‘in-depth theory-testing process-tracing’ (Beach and Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2019: 245–267). As opposed to a probabilistic logic of co-variation, process-tracing relies on a deterministic logic, which is based on differences in kind – a causal step linking a given cause to an outcome is either present or not – rather than cross-case variations in variables.Footnote 2 This implies that the presence of a certain causal mechanism does not necessarily exclude the existence of alternative mechanisms linking a cause with the outcome. Hence, instead of falsifying hypotheses by comparing different cases, theory-testing process-tracing seeks to assess the presence of pre-defined evidence that is necessary and/or sufficient to claim causal inference. In practical terms, this requires ‘unpacking a causal mechanism into parts composed of entities engaging in activities, operationalizing empirical fingerprints for each part, and then tracing empirically whether actual evidence indicates that the mechanism worked as hypothesized’ (Beach and Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2019: 253). Finally, the strength and type of empirical tests provided by each fingerprint need to be determined.

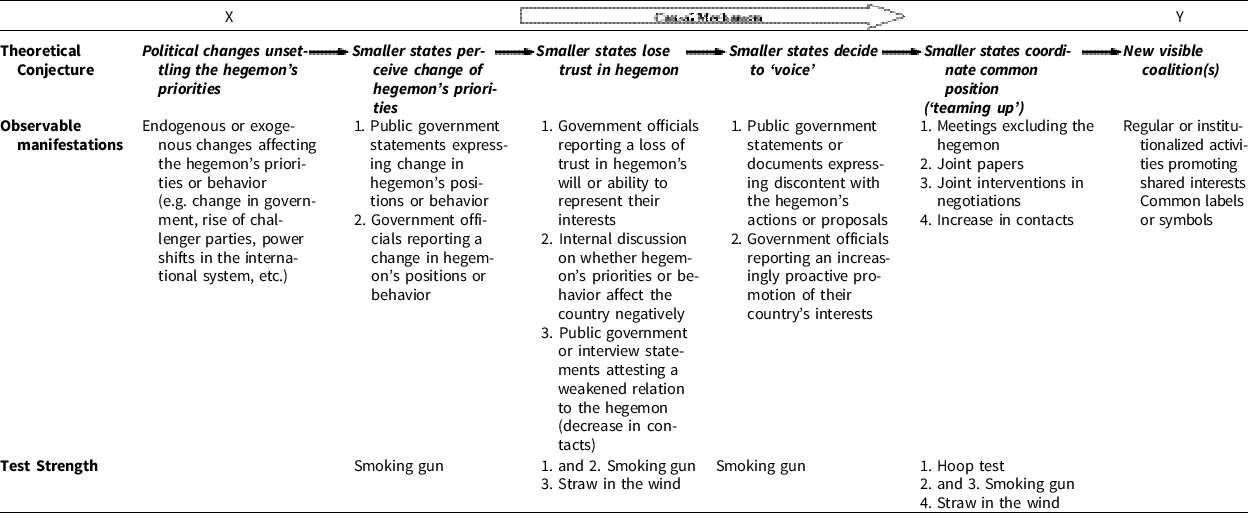

The causal mechanism proposed by this article (Table 1) starts with internal or external changes that unsettle the hegemon’s way of evaluating or acting on the international system. As the first step of the causal mechanism, smaller states profiting from the system perceive this change in the hegemon’s priorities. One may observe their perceptions through public documents or speech acts, such as position papers or press releases. However, given the diplomatic implications that public comments on the hegemon’s priorities would have, evidence is more likely to be found by conducting elite interviews with government officials involved. Hence, if we find statements by the governments or officials of smaller creditor states expressing a perceived change in Germany’s priorities or behavior, we can be sure that the first step in the causal mechanism has actually taken place (‘smoking gun’; Van Evera, Reference Van Evera1997: 31–32).

Table 1. Causal mechanism

If smaller system profiteers notice a change in the hegemon’s priorities, they will fear that the hegemon will no longer act in their interest. Hence, in the second causal step, smaller states see their benefits from the existing system as being at risk. While it is unlikely that small-state governments will go public with such information, government officials may admit a lack of trust in the hegemon in confidential interview settings (‘smoking gun’). In addition, a loss of trust in the hegemon may manifest itself in internal discussions about whether the hegemon’s plans or actions affect their countries negatively. Finally, we may find statements attesting a weakened relation with the hegemon. Such evidence will increase our confidence in the plausibility of the causal mechanism, but it can neither confirm nor disconfirm that there has been an actual loss of trust in the hegemon (‘straw in the wind’; Van Evera, Reference Van Evera1997: 32).

Once smaller states conclude that they can no longer rely on the hegemon, at least the more powerful among them will start to openly express their preferences.Footnote 3 This decision to ‘voice’ constitutes the third part of the causal mechanism. It may be observable through public statements – such as position papers or press interviews – expressing discontent or rejecting the hegemon’s actions or policy proposals. Such statements may also take the more diplomatic form of (counter-)proposals or a proactive promotion of interests (‘smoking gun’).

The fourth step of the causal mechanism consists of smaller states ‘teaming up’ and coordinating common positions with like-minded partners. This can be observed through increasing contacts between these states (‘straw in the wind’). Moreover, one cannot plausibly affirm that states build coalitions without finding evidence confirming that they have actually met. Group meetings thus constitute a so-called ‘hoop test’ (Van Evera, Reference Van Evera1997: 31). In addition, smaller states may draft common papers or jointly intervene in negotiations (‘smoking gun’). In the following case study, we, therefore, expect smaller creditor states to team up by organizing meetings without Germany. An increase in contacts between small creditor states and joint activities, such as papers or interventions in Eurogroup negotiations, would further increase our confidence that the suggested causal mechanism is actually at work.

The outcome of this process is the emergence of a publicly visible small-state coalition. Visibility plays an important role in the effectiveness of such a coalition. As small states lack bargaining power, they can increase their influence by ‘playing the public’ (Keohane, Reference Keohane1971: 175–179) and thereby creating public pressure on the hegemon to react to their demands. By contrast, a coalition of small states acting only behind closed doors could be easily ignored by the hegemon. This implies that the coalitions resulting from the above causal mechanism not only coordinate common positions, but also publicly promote their interests (e.g. via media channels) or even use visible labels or symbols.

As it becomes clear from the above, much of the data required to (dis)confirm the propositions can only be gathered through elite interviews. Interviews are often the only way to infer preferences independently of observable behavior (Rathbun, Reference Rathbun, Box-Steffensmeier, Brady and Collier2008: 690–691). Therefore, this article relies on 26 semi-structured elite interviews conducted with mostly high-ranking officials working in the relevant units of ministries in Germany and smaller creditor states, EU institutions, and Permanent Representations in Brussels. In order to obtain relevant information, the respondents were guaranteed strict confidentiality. With a view to increasing the reliability of the material, several officials from each country were interviewed independently of each other and questions suggesting causal relationships or social desirability were omitted. If the respondents agreed, the interviews were recorded. Otherwise, handwritten notes were made. Finally, the interview material was analyzed according to the empirical ‘fingerprints’ outlined above. Wherever possible, the information obtained was triangulated across different interviews and other types of sources.

Centrifugal tendencies: the emergence of the New Hanseatic League

By the end of 2017, the ‘New Hanseatic League’ (New Hansa) emerged in the eurozone as a group of eight northern EU countries: the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Ireland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. While the New Hansa is reported to be an initiative led by the Netherlands, it also extends existing cooperation among Nordic and Baltic states (‘NB6 format’) (Interviews NL1, NL2, EE2; Schulz and Henökl, Reference Schulz and Henökl2020). On 5 March 2018, the finance ministers of the eight countries published a position paper in which they outlined their shared views on the EMU architecture.Footnote 4 They advocated a more inclusive format for discussion, which should also be open to non-euro area members, and they demanded ‘decisive action at the national level’ as regards the compliance with fiscal rules. Moreover, they supported a stronger role for the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in the development and monitoring of financial assistance programs and the exploration of orderly sovereign debt restructuring. Finally, they proposed to support the implementation of national structural reforms through the EU budget.

Taken together, the substantive proposals promote risk reduction at the national level (instead of risk sharing at the European level) and would thus shift the distribution of gains within the currency union further in the direction of creditor states. With regard to the institutional issues, a more inclusive format for discussion would strengthen the position of creditor states as it would also include their ‘frugal’ Scandinavian allies, notably Denmark and Sweden. Further activities of the New Hansa included successful opposition to Franco–German plans for a eurozone budget (Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2020b), a position paper supporting Capital Markets Union (CMU), and a paper demanding a reinforced role for the ESM regarding the negotiation and monitoring of conditionality agreements. Occasionally, the New Hansa was joined by other small states such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In terms of process, the finance ministers of the New Hansa states met for dinner every 2 months around ECOFIN or Eurogroup meetings, and there were monthly meetings at the Financial Counselor level in Brussels (Interviews BRU6, NL2, NL4).

According to a closely involved Dutch official, the aims of the New Hansa are first, to promote a ‘counter-narrative’ of the causes of the crisis; second, to set the agenda on issues in the interest of creditor states; and third, to block certain risk-sharing proposals such as a eurozone budget. In fulfilling these functions, the New Hansa saves transaction costs for small states: by collecting and aggregating their preferences, the Netherlands can strengthen its own position while representing the common interests of small creditor states more forcefully (Interview NL1). Although not all government officials were so decided about the specific task description of the New Hansa (Interview EE2), they all agreed that it served to coordinate their positions and increase the influence of smaller creditor states (Interviews EE1, EE3, FI2, FI4; background talk 5). In the words of another Dutch official, ‘if we want to gain some influence … we have to show that we operate as a block or that we, as the Netherlands, can speak for a larger group’ (Interview NL3).

As a German official underlined, a coalition like the New Hansa had been unprecedented in eurozone politics (Interview DE2). On the one hand, this regarded the public visibility of the New Hansa, which proactively publicized its joint papers and meetings instead of working behind the closed doors of Committees and Eurogroup meetings (Interview NL7). On the other hand, the group’s novelty was its potential to disrupt conventional practices in the EMU decision-making process. As an EU official put it, ‘these Hanseatic countries … opened another front… Until then … we said “ok, once France and Germany agree on some sort of compromise, well, everybody else will more or less find him- or herself behind these two countries.” But with these Hansa countries you have a new front, and that’s why the French are so annoyed about it’ (Interview BRU3). Given that the New Hansa states pursue their aims without Germany, the coalition is a manifestation of centrifugal tendencies in eurozone politics. In order to find out whether it is also a consequence of changes in Germany, the remainder of this section will trace the above-described causal mechanism.

According to the first step in the proposed causal mechanism, we expect smaller creditor states to perceive a change in the hegemon’s priorities or behavior. Indeed, the elite interviews conducted for this article revealed overwhelming evidence corroborating this expectation. Interviewees stated that in recent years, Germany’s positions have become more inconsistent. In particular ‘the very first communications when the new German government was formed were very inconsistent: Merkel said one thing; Scholz said another’ (Interview NL2; also BRU11, FI4; background talk 5). Moreover, the respondents noticed a change in German positions regarding stabilization mechanisms, such as the eurozone budget promoted by France or the European unemployment reinsurance scheme advocated by German Finance Minister Scholz (Interviews FI4, NL4). As a Dutch official stated with regard to such stabilization functions, ‘We used to be totally on the same page, I think, whereas nowadays … we have totally different ideas’ (Interview NL1). With regard to the eurozone budget proposal, a change of position was even admitted by German officials, albeit to different degrees (Interviews DE1, DE2). The interviewees attributed these changes to the role of the new German Finance Minister (‘Scholz is less outspoken, has less … status’) and Chancellor Merkel’s gradual retreat from politics (Interviews EE3, FI2, NL2).

In addition, some interviewees interpreted the perceived change in German positions as concessions to France. As a Dutch official stated: ‘we noticed that she [Chancellor Merkel] was actually much more willing to give the French something on EMU than she maybe had been before … such as the eurozone budget: That was not something the Germans originally wanted and we thought ‘ok good, if the Germans don’t want it, then it’s probably not going to happen’. But now they have moved towards the French position’ (Interview NL4). This impression was independently confirmed by an Estonian official: ‘We have the feeling that Germany can actually give up its own positions and then move forward towards France … And it seems to me that also the coalition in Germany is … playing a role because … when Schäuble was Minister of Finance and Merkel was, in my opinion, more powerful, then maybe Germany didn’t allow … France to rule’ (Interview EE3; also FI2).

Moreover, the respondents perceived a more intense cooperation between Germany and France (Interviews EE1, FI2, FI4), which was independently confirmed by a German official (Interview DE1). One interviewee explained that for the first time under the new German government, the Franco–German tandem was monopolizing the debate, and referred to meetings at which, next to the EU institutions, only representatives of Germany and France were present, thereby excluding all the other member states. As a consequence, smaller creditor states perceived less leadership from Germany, which signaled concessions to France rather than promoting the fiscally conservative views of northern eurozone members (Interviews BRU2, EE1, EE3, FI2, background talk 5). In summary, the interview material strongly indicates that the first step in the causal mechanism took place (‘smoking gun’).

The second causal step consists of smaller system profiteers losing trust in the hegemon. Once again, the interview material provides abundant evidence that smaller creditor states lost trust in Germany’s will or ability to represent their interests. While some respondents found that uncertainty about German positions had increased (Interviews BRU11, FI1, background talk 5), most of the relevant statements mentioned the perceived shift in German positions toward France as a cause for concern. As a Dutch official stated, with the new German government, a Franco–German compromise is no longer an acceptable option as Germany has become too lenient in fiscal matters.

The Dutch assessment (Interviews NL1, NL2, NL4) was echoed by Finnish officials (Interviews FI1, FI2, FI4): after the new German government had taken office, there was a time when the ‘Council was serving two member states only’ (namely Germany and France). This resulted in reform proposals with huge German, French, and Commission ownership (Interview FI4) and ‘some sort of alienation’ on the part of smaller creditor states (Interview FI2, also BRU2). Accordingly, a high-ranking EU official noted ‘a concern by the Dutch or by the Fins that Germany is drifting apart or Germany is being dragged by Macron into something they don’t want’ (Interview BRU11). The loss of trust in the hegemon manifested itself also in internal discussions about whether Germany’s recent priorities affected their own country negatively (Interviews EE2, FI4, NL2, NL3, NL4). By contrast, a relatively weak (‘straw in the wind’) observable manifestation, namely the decrease in bilateral contacts, could not be found as bilateral relationships remained stable (Interviews EE2, FI1, NL1, NL2, NL4).

In the third causal step, we expect smaller creditor states to voice their preferences. As regards relevant expressions of discontent, in particular, the Franco–German ‘Meseberg declaration’ led to a strong reaction by smaller creditor states (Interviews BRU7, DE1, DE2). On behalf of 12 smaller states, the Dutch Finance Minister wrote a letter to the President of the Eurogroup expressing their rejection of the proposal (Interview BRU7; Brunsden and Khan, Reference Brunsden and Khan2018). On other occasions too, smaller creditor state governments voiced their rejection of further stabilization mechanisms in the eurozone. The Dutch government has been most outspoken in that regard. When the eurozone negotiated a budgetary instrument to support national reforms a year after the Franco–German proposal, for instance, Dutch Prime Minister Rutte stated most unambiguously, ‘I would never support more stabilization mechanisms at eurozone level’ (quoted in Valero, Ketelsen and Ball, Reference Valero, Ketelsen and Ball2019). In interviews with German officials, they unanimously confirmed that smaller creditor states have become more active in voicing their preferences. Often led by the Netherlands and in the form of the New Hanseatic League, they proactively informed the German Finance Ministry of their interests.

Hence, the active promotion of interests increased among the New Hansa countries. As a strongly involved EU official noted, ‘the other countries are willing to make their dissenting votes known and to insist’ (Interview BRU11). At the same time, single creditor countries have maintained rather constant levels of activity (Interviews EE1, FI2, FI4, SI1). The one big exception in this regard seems to be the Netherlands, which stepped up its efforts to become more vocal and thereby acted as the unofficial leader of the New Hansa (Interviews BRU10, DE1, EX1, NL2, NL3, NL5, NL7, SI1). One high-ranking Dutch official explained that the Netherlands changed their strategy from bridging the German and French positions to forming a hawkish coalition (Interview NL7). This was confirmed by officials working for the EU institutions and other governments, who found that the Netherlands had become ‘the most radical member state’ (Interview BRU10, also EX1, SI1) when it comes to preventing risk sharing in the eurozone. In summary, there is strong evidence indicating that smaller creditor states decided to ‘raise their voices’ in EMU politics and engaged in a more active promotion of their interests (‘smoking gun’). While most countries did so by joining the New Hansa rather than increasing their individual efforts, the Netherlands became both more vocal and more radical in EMU politics.

This finding fits in with a more general pattern that emerges from this research. While smaller or medium-sized states like Finland and the Netherlands have well-defined preferences but need allies to be heard, the smallest states such as Estonia or Slovenia lack the capacity to voice their preferences. As an Estonian official stated, in ‘not more than half of the questions [do] we actually define the national interest; we rather follow the general thinking’. By joining the New Hansa, the smallest states thus obtain a visible representation, even if they do not share all of the group’s views.Footnote 5 Vice versa, more vocal states like the Netherlands can strengthen their positions by gathering less active states behind them (Interviews BRU6, EE1, EE2, EE3, FI3, NL1, NL4, SI1, SI2).

The fourth causal step expects smaller system profiteers to coordinate a common position. If this step works as expected, we must find meetings of smaller creditor states without Germany (‘hoop test’). Further strong evidence would consist of joint papers and interventions in negotiations (‘smoking gun’). At the end of 2017, the finance ministers of the New Hansa states started to meet every 2 months for dinner (Interview NL2) and there were monthly meetings of Financial Counselors in Brussels (Interview BRU6). Usually, these meetings took place without German representatives, who may have been invited as guests on an occasional basis and only for short parts (‘coffee and cake’, Interviews BRU6, DE1). The first meeting was initiated by the Irish against the background that a German government had yet to be formed, which some member states – particularly France – interpreted as a ‘window of opportunity’ to deepen EMU (Interview FI4). Wopke Hoekstra, the Dutch Finance Minister, took the opportunity to coordinate the first New Hansa paper (Interviews FI4, NL1). After that, the Netherlands, Finland, and Ireland took the lead on drafting further papers. While this shows that leadership within the group changed according to the issue at stake, due to their openness and media presence, the Netherlands were perceived as the unofficial leader of the group (Verdun Reference Verdunforthcoming). Germany did not see the joint papers before they were published (Interview BRU11). Some of these statements have left visible marks. Parts of the New Hansa’s ESM paper, for instance, have entered the revised ESM treaty draft (Interview NL2) and the Franco–German proposal of a eurozone budget was converted into a reform delivery tool before it was eventually dropped (Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2020b).

As regards common interventions in negotiations, we find less evidence. One interviewee reported a Eurogroup meeting, where the Dutch and Fins organized a common position of small northern countries and insisted on taking it into account when preparing a letter to the then European Council President Tusk (Interview BRU11). In another such instance, the New Hansa countries jointly supported Denmark and Sweden when negotiating their exemptions from the eurozone budgetary instrument (BICC) (Smith-Meyer and Brenton, Reference Smith-Meyer and Brenton2019). However, while the New Hansa countries explicitly refer to their joint papers and internal agreements, each country speaks for itself in the negotiations (Interviews AT1, DE2, NL4, SI1). Regarding increased contacts among smaller creditor states, finally, the evidence is somewhat mixed. While some officials reported more coordination with smaller states (Interviews EE2, FI2, NL1, NL2), others said they had only been contacted more frequently (Interview EE1) or did not perceive any increase in contacts (Interview FI4).

Taken together, the interviewees largely agreed on the purpose of the New Hansa: against the background of Brexit, fiscally conservative and liberal EU countries were concerned that Germany would make costly concessions to France in favor of enhanced risk sharing and further integration. In order to give more visibility to their interests, they expressed their preferences publicly as the ‘New Hanseatic League’. In the words of a Dutch official, ‘as a small country … we would always be careful whether the Franco-German tandem will not crush us in their spirit of compromise … so that’s why you have Hansa League’ (Interview NL4). Hence, the New Hansa served as a tool to counterbalance the Franco–German tandem (Interviews FI1, FI2, FI4, NL2, NL5, NL6). In the words of a Finnish official, the coalition was a means ‘to show the French and Germans that if you take decisions … please don’t decide on our behalf’ (Interview FI3).

Although the New Hansa has focused its activities on EMU matters, some interviewees stressed that Brexit was an important background condition for the emergence of the New Hansa. With the exit of the UK, liberal EU member states lost an important ally and thus felt the need to make their voices heard (Interviews DE2, EE3, FI2, NL2, background talk 4). Hence, Brexit increased the concern about a Franco–German dominance in EU politics and thus functioned as a catalyst in the formation of the New Hansa.

The added value of hegemonic theory and alternative approaches

In investigating how smaller creditor states in EMU react to a change in German priorities, the refined propositions of HST provide a parsimonious explanation for the emergence of publicly visible small-state coalitions such as the New Hanseatic League and allow us to generalize on the empirical results. While there are other prominent approaches in the relevant literature, too, they may explain the rise of the New Hansa only to a limited extent.

First, EMU politics has been fruitfully analyzed from an intergovernmental bargaining perspective (e.g. Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015; Frieden and Walter, Reference Frieden and Walter2017). Rational intergovernmentalists assume that international politics is made of utility-maximizing governments pursuing their preferences under given institutional constraints. Under conditions of unanimity, bargaining power is determined by the distance between a government’s preferences and the status quo: the closer a government’s preferences are to the status quo, the better its alternative to a negotiated agreement, and the more powerful its bargaining position. Coalitions and side-payments may therefore serve as means to prompt a status quo power to make concessions (Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1993: 502–507), but they are not needed as a strategy to maintain the status quo. While an intergovernmental bargaining perspective shares many assumptions with HST, it struggles to explain the rise of the New Hansa. In particular, it can hardly explain why Germany, as the most powerful state in EMU, is willing to compromise, whereas less powerful actors build a coalition to insist on the status quo. Intergovernmentalist approaches would rather expect Germany to determine the ‘lowest common denominator’ on which all other states have to settle in order to find an agreement. Taking preferences seriously, we would furthermore expect a coherent camp of creditor states, led by Germany and opposed by the debtor states (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015; Lehner and Wasserfallen, Reference Lehner and Wasserfallen2019), rather than the rise of a separate coalition without Germany.

Another insightful approach to the politics of monetary union is based on the theory of collective action (Olson, Reference Olson1973; Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2017). Focusing on the provision of collective goods such as a common currency, collective action theory can well explain free-rider dynamics and, in particular, how the great tend to be ‘exploited’ by the small (Olson, Reference Olson1973: 35). While collective action theory can thus explain why small creditor states free ride on the negotiation efforts of Germany, it cannot explain why these states formed a coalition without Germany. In a world without a hegemon, such a coalition would not be necessary as each member state would decide for itself how much to contribute to the maintenance of the collective good. However, a hegemon can make small states pay a larger share than they would otherwise have contributed. Hence, by adding the hegemon as a crucial explanatory factor, HST can explain the rise of the New Hansa as an attempt of small states to prevent the hegemon from making them pay higher contributions than under the existing arrangement – something that remains puzzling from a pure collective action perspective.

The third prominent approach relies on the role of ideas and policy beliefs in explaining EMU politics (e.g. McNamara, Reference McNamara1998; Matthijs and Blyth, Reference Matthijs and Blyth2018). In line with this approach, one could argue that Germany has learned the lesson that its strict adherence to ordoliberal ideas is unsustainable for the long-term coherence of EMU and thus against its own goals (see Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2016a). However, it would be difficult to explain why only Germany has learned this lesson, whereas other EMU creditor states have not. Moreover, while ordoliberalism is an influential school of thought in Germany, there is no such powerful idea that would unite the smaller creditor states in the New Hansa. To be sure, one might argue that they all share a strong belief in frugality rooted in Protestant social thought (Hien, Reference Hien2019). However, these common cultural roots would include Germany in a coalition rather than leading to the rise of a separate small-state coalition.

Conclusion

How do smaller states which profit from a hegemonic system react to a change in the hegemon’s priorities? This article argues that even a temporary change in hegemonic priorities unleashes centrifugal forces as those states privileged by the system no longer see their interests guaranteed. However, as ‘exit’ is usually not an attractive option for system profiteers they need to ‘voice’ their preferences (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970). Especially when there are no alternative institutional frameworks, small states need to put more effort into making their interests heard within the existing system (Weiss, Reference Weiss2020). An effective strategy for doing this is to build a publicly visible coalition to ‘tie up’ the hegemon (Keohane, Reference Keohane1969). Translating this theoretical proposition into an empirically traceable causal mechanism, the article tests its argument against current eurozone dynamics.

The article analyzes how free riding on Germany’s hegemony has become less rewarding for its smaller allies in the north of the eurozone (‘creditor states’). These fiscally conservative countries have long relied on Germany in EMU governance and reform. However, in recent years, Germany has been coping with domestic developments such as a shaky government coalition, a Chancellor on her way out of politics, and a crucial personnel change in the Finance Ministry. At the same time, French President Macron has demanded more concessions on risk sharing in EMU and Brexit has led to a power shift toward the Franco–German tandem. When smaller creditor states started to perceive increasingly intense Franco–German collaboration and a possible shift in German positions toward French demands, they formed the ‘New Hanseatic League’ as a visible coalition to voice their own preferences.

By drawing on a theoretically informed proposition, the article not only explains the emergence of the New Hansa, but also provides a conjecture on its future: whenever Germany appears to deviate from its hegemonic role of preserving the ‘present euro regime with its asymmetric insistence on the structural adjustment of southern economies’ (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2018: 62), thereby making concessions to France, the activity of ‘frugal’ EMU members will increase. By contrast, if Germany credibly resists demands for more burden-sharing in the eurozone, its smaller allies can free ride in the shadow of German hegemony.

This implies that the preference constellation in eurozone politics is not as clear-cut as it is usually portrayed. While fiscal positions or current account balances predict one homogeneous camp of eurozone creditor states led by Germany, we actually find issue-specific coalitions of smaller ‘frugal’ states excluding Germany. In times of eurozone crisis management, smaller creditor states saw their interests guaranteed by a reluctant or even coercive German hegemony. Now, they are ready to open a new front whenever their positions diverge from those of Germany. In other words, small creditor states in EMU have moved from mere ‘sheltering’ in the hegemonic shadow of Germany to active ‘hedging’ by building visible coalitions with like-minded states to ‘voice’ their preferences (see Wivel and Thorhallsson, Reference Wivel, Thorhallsson, Diamond, Nedergaard and Rosamond2018).

The article’s argument is not restricted to the New Hansa. The same pattern can be observed in the EU’s reaction to COVID-19. When Germany and France proposed a 500bn recovery fund based on grants instead of loans, thereby committing to the issuance of common debt in the EU, a counter-coalition of fiscally conservative member states emerged. The so-called ‘Frugal Four’ (the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Austria), later joined by Finland, used to be close allies of Germany in EMU and EU budget matters. However, as the external shock of COVID-19 led to another change in Germany’s priorities, these states set out to form a vocal counter-coalition. To be sure, the evidence provided by this article can only illustrate the plausibility of its argument. Testing the argument’s external validity in other EU policies or world regions, therefore, constitutes a fruitful avenue for future research.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to James Caporaso, Martin Höpner, Katharina Meissner, and the participants of the ‘Virtual EU Seminar’ organized by Michael Blauberger for valuable comments on an earlier version of this article. Moreover, I would like to thank André Sapir, Ivo Maes, and Piret Kuusik for helpful background talks. I am also hugely indebted to more than 30 interviewees in national ministries and EU institutions. Finally, I acknowledge financial support from the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Vienna.

Funding Details

The author is a recipient of an APART-GSK Fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (Grant Number: 11878) at the Department of Political Science of the University of Vienna.

Disclosure Statement

The author has no potential conflict of interest to disclose.